Abstract

Disasters caused by natural hazards, including the August 2023 floods in Slovenia and the 2020 earthquakes in Croatia, resulted in a combined damage and loss of about EUR 26 billion. Indemnity insurance covered only a small share, shifting recovery to public budgets. This review examines whether parametric insurance can provide transparent, pre-arranged, and auditable post-event liquidity to smooth public finances and support timely recovery. A structured qualitative review of peer-reviewed studies, supervisory materials, and EU and national law assesses data readiness, enforceability, and consumer protection duties. EU rules address parts of prudential and conduct risk. However, gaps persist in trigger verification, automated execution, and in the treatment of third-party trigger data sources and calculation methodologies documented for supervisory reviews and audits (no published parametric-specific accreditation standards). The core gap reflects the low take-up of catastrophe insurance rather than a low overall insurance penetration. Parametric cover is treated strictly as a complement to indemnity insurance. We outline narrowly scoped pilots using verifiable, publicly sourced triggers, version-controlled calculations, pre-tested basis risk disclosures, and reversible, auditable settlements with human oversight. Parametric designs add value only when verifiable triggers, transparent disclosures, and supervisory audits are embedded ex ante.

Keywords:

parametric insurance; sustainable finance; disaster-risk governance; Slovenia; Croatia; floods; earthquakes; EU regulation; consumer protection; sustainability JEL Classification:

G22; G28; K23; Q54; Q01

1. Introduction

In recent years, the economic costs of natural hazards have reached historically high levels. In both 2023 and 2024, global losses from disasters caused by natural hazards were very high (approximately USD 268–280 billion in 2023; approximately USD 320–368 billion in 2024), with uninsured shares typically exceeding 50%. Major reinsurer reports indicate that approximately 60% of 2023 catastrophe losses were uninsured. This gap reflects the growing mismatch between mounting natural hazard exposures and the capacity of conventional indemnity-based insurance systems to absorb increasingly frequent and severe losses [1,2,3,4]. In this review, the protection gap is framed as a sustainability challenge in public finance, because delayed and opaque recovery outlays undermine transparent, equitable, and rules-based disaster governance. Parametric insurance is therefore examined strictly as a complement to conventional indemnity cover, with sustainability relevance grounded in transparent, pre-arranged, and auditable post-event liquidity.

This global protection gap manifests in various regional contexts, including within the European Union, where it assumes distinct structural and fiscal dimensions. This framing links disaster risk financing to sustainability governance by emphasising measurable, transparent, and rules-based fiscal resilience in post-disaster recovery.

This study focuses on Slovenia and Croatia because both are small EU member states with a low take-up of catastrophe insurance, shallow risk pools, and constrained fiscal space, which together heighten the relevance of objective, index-based risk transfer [5,6,7,8,9]. This selection enables a like-for-like comparison across two broadly similar institutional settings while covering different natural hazard profiles. The contribution is to translate global parametric practice into a feasibility pathway for small EU markets with low catastrophe coverage. It links verifiable triggers and consumer protection duties to transparent, rules-based post-event finance, with outcomes tied to fiscal smoothing, payout timeliness, and trust. Recent digital claims workflows (for example, satellite/Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR)/drone) can partly reduce the historical speed advantage of parametric payouts. However, the primary value of parametric designs lies in ex ante transparency and auditability. Consequently, the value proposition of parametric insurance is shifting toward ex ante transparency and auditability rather than just rapid payment [4,6]. Against this backdrop, parametric insurance, where payouts are triggered by predefined, measurable parameters rather than assessed damage, is considered a complementary disaster risk financing tool. Feasibility is tied to safeguards for accuracy and fairness, including verifiable triggers, standardised basis risk disclosures, and accessible dispute resolution pathways.

The article is structured as follows: Section 2 details the review design; Section 3 consolidates recent disaster impacts in Slovenia and Croatia; Section 4 provides the global context; Section 5 synthesises opportunities and constraints; Section 6 analyses the legal frameworks; Section 7 discusses automation safeguards; and Section 8 distils policy implications, pilots, and conclusions.

The contribution is specific to small EU economies and complements existing analyses focused on sovereign schemes in developing countries or capital market instruments. It assesses institutional feasibility in two hazard-exposed markets characterised by a low take-up of catastrophe insurance.

However, research has consistently pointed to structural and technical barriers. Surminski and Oramas-Dorta [10] assessed 27 flood insurance schemes in low- and middle-income countries and identified the lack of integrated risk-reduction incentives as a critical limitation. They noted that the vast majority of schemes failed to formally link insurance with prevention. Leblois, Quirion, and Sultan [11] documented a high basis risk in weather-index insurance models in Cameroon. Steinmann et al. [12] identify spatial, temporal, and design-related basis risks as persistent limitations.

Kim et al. [13] proposed deep neural networks to capture nonlinear relations between hazard indicators and economic loss. Accordingly, supervisory readiness, consumer disclosures, dispute resolution, and the operational verification of triggers and trigger data sources are treated as preconditions for trustworthy deployment in Slovenia and Croatia, with a specific attention to data quality, continuity, and standardisation.

As Schwarcz [14] argues, in the U.S. context (foreign law), delegating public regulatory functions to private entities without adequate oversight introduces significant risks of opacity and reduced accountability. Although Schwarcz focuses on the U.S. regulatory environment, the underlying issue of oversight over automated or data-driven execution is also relevant to Slovenia and Croatia. In these countries, no dedicated parametric-specific statutory regime exists; parametric products fall under general insurance and contract law and are supervised by the competent authorities (AZN; HANFA).

Despite the growing interest in parametric solutions, few systematic studies address their institutional feasibility in EU member states with a low take-up of catastrophe coverage. Most existing studies focus on sovereign schemes in developing countries or capital market-based solutions. The existing legal scholarship highlights conceptual and regulatory gaps in aligning automated payouts with consumer protection and contractual enforcement [15,16,17]. Early blockchain governance failures (for example, the DAO) are referenced only to motivate auditability, reversibility, and oversight in any optional automation layer [18,19,20,21]. Accordingly, the feasibility assessment considers enforceability, third-party trigger data sources, and documented calculation methodologies for supervisory reviews and audits. It sets out implementation pathways that balance speed with the rigour required for accuracy and fairness. Community acceptance, social equity, and a willingness to purchase are recognised as essential demand-side determinants.

To guide the analysis, the following research questions are formulated, with a specific focus on Slovenia and Croatia and with attention to data quality and the rigour–speed trade-off:

- What are the impacts of recent floods and earthquakes in Slovenia and Croatia, and what do these events reveal about the vulnerabilities in existing risk management and recovery systems?

- How does parametric insurance address the limitations of traditional insurance models in the context of floods and earthquakes, and what are its specific advantages and constraints given data quality, continuity, and standardisation requirements?

- To what extent do legal, regulatory, and institutional frameworks in Slovenia and Croatia support or hinder implementation, particularly regarding enforcement, supervision, mandatory consumer disclosures, and the protection of policyholders’ rights in automated payout systems; and how do verification standards for triggers affect auditability and perceived fairness? Where relevant, how do rigour requirements interact with the speed and simplicity that motivate parametric insurance?

This review applies an interdisciplinary framework to evaluate the feasibility of parametric insurance for sudden-onset disasters caused by natural hazards in Slovenia and Croatia and to clarify policy and implementation pathways. Feasibility is analysed across three interrelated dimensions: legal and regulatory compatibility, technical and operational viability, and institutional coordination capacity. These dimensions structure the literature review and indicate the minimum preconditions for implementation. The framework links verifiable triggers and auditable execution to transparent recovery finance and connects operational design choices to measurable outcomes such as recovery timelines and public finance burdens. Parametric insurance is treated as a socio-legal mechanism whose effectiveness depends on its alignment with governance structures, supervisory mandates, and data infrastructures; transparent consumer disclosures and fair dispute resolution are required to sustain trust.

This lens supports a structured comparison of Slovenia and Croatia and situates both within EU-level disaster finance efforts and legal harmonisation initiatives. It also identifies gaps that require regulatory, institutional, or operational reforms before parametric instruments can function as a viable complement to traditional coverage. Taken together, the framework motivates the emphasis on verifiable triggers, transparent disclosures, and auditable execution as prerequisites for sustainability-aligned, rules-based post-event finance.

From an insurance economics perspective, demand declines when contracts depart from indemnity or introduce basis risk [22]. Basis risk and ambiguity about trigger performance reduce the willingness to pay, particularly where trust in data and institutions is weak [23,24].

2. Materials and Methods

This review is situated within the interdisciplinary field of disaster risk governance at the interface of finance, technology, and supervision, and adopts a structured qualitative review design. Its objective is to assess the feasibility of parametric insurance for floods and earthquakes in Slovenia and Croatia by analysing compatibility with applicable legal frameworks, regulatory structures, and institutional capacities. The analysis is both interpretive and analytical, relying entirely on secondary sources. No primary data collection, interviews, or fieldwork was conducted, and no software models or smart contract code were implemented. Database searches imposed no start-year restriction (foundational works from 1996 onwards were eligible) and were last updated on 5 February 2025. Sources were limited to English, Slovene, Croatian, and Portuguese (Portuguese only for Brazilian regulatory materials). In line with the study’s legal focus, the review evaluates whether third-party trigger data sources and calculation methodologies would require and could satisfy supervisory approval and validation, alongside the operational verification of triggers. No preregistration was undertaken; no human or animal subjects were involved.

Screening followed predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, and grey literature was cross-referenced against peer-reviewed sources and was retained only when it was citable and attributable to competent public authorities or standard-setting bodies.

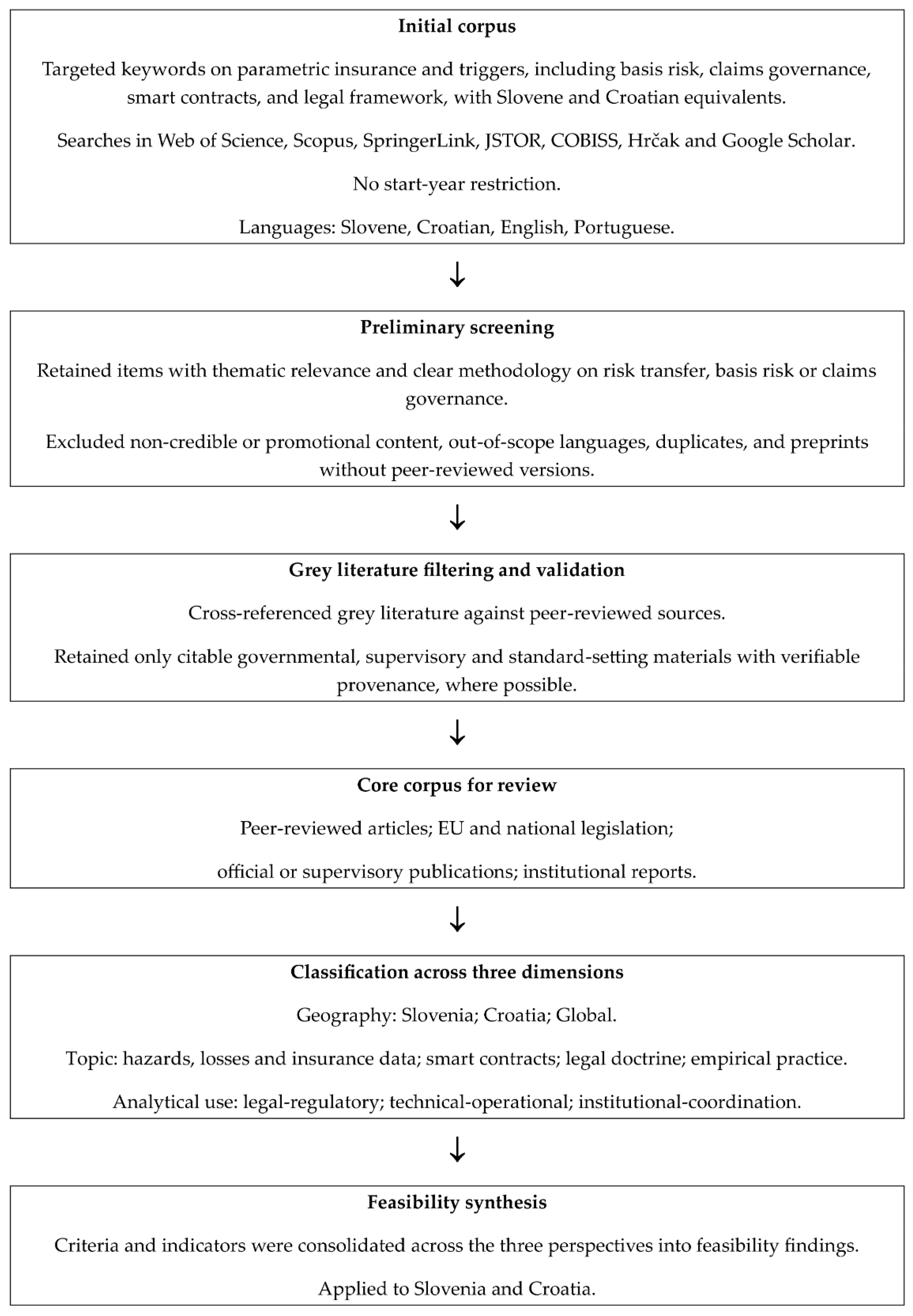

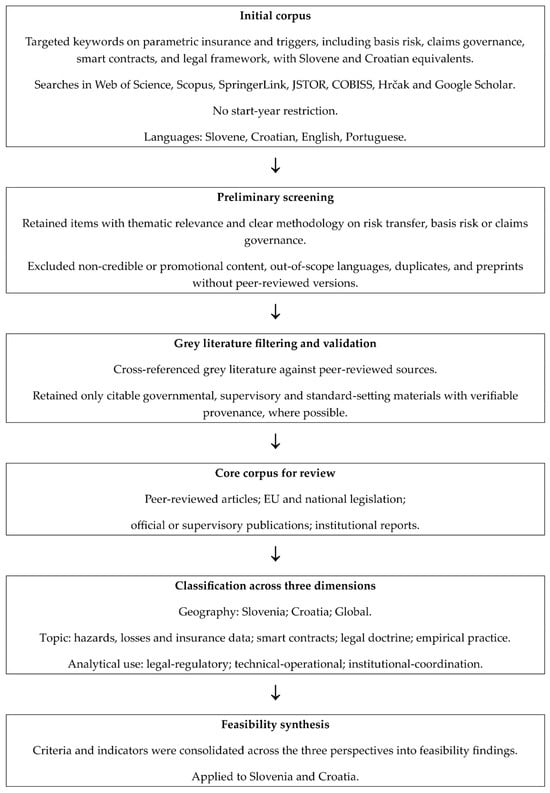

Figure 1 presents the selection flow and the analytical framework used in the review, from the initial corpus through preliminary screening, grey literature validation, formation of the core corpus, classification across three dimensions, and feasibility synthesis applied to Slovenia and Croatia.

Figure 1.

Selection flow and analytical framework of the review.

2.1. Review Dimensions and Analytical Frame

The review proceeds in three coordinated dimensions used consistently throughout the manuscript:

- (i)

- Legal and regulatory compatibility,

- (ii)

- Technical and operational viability,

- (iii)

- Institutional coordination capacity.

These dimensions are analysed within a single framework and then applied comparatively to Slovenia and Croatia.

- (a)

- Legal and regulatory: The doctrinal legal method was applied. EU legislation relevant to insurance distribution and prudential supervision, data, and AI governance was reviewed for relevance to parametric arrangements, including the following:

- Directive 2009/138/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 November 2009 on the taking up and pursuit of the business of insurance and reinsurance (Solvency II) [25];

- Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (GDPR) [26];

- Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence and amending certain Union acts (AI Act) [27];

- Regulation (EU) 2023/2854 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 December 2023 on harmonised rules on fair access to and use of data and amending Regulation (EU) 2017/2394 and Directive (EU) 2020/1828 (Data Act) [28].

The Data Act was published on 22 December 2023 and entered into force on 11 January 2024; most provisions apply from 12 September 2025. The AI Act was published on 12 July 2024 and entered into force on 1 August 2024, with most provisions applying from 2026.

National insurance and contract law provisions in Slovenia and Croatia were examined for compatibility with automated triggers, data-driven payouts, and the use of external data sources. Peer-reviewed legal scholarship and official supervisory materials on product oversight, governance, and pre-contractual disclosures were used to align feasibility criteria with supervisory practice. Within this dimension, the analysis remains doctrinal and interpretive, not developing econometric or forecasting models. The core question is whether third-party trigger data sources and calculation methodologies can obtain supervisory approval and validation in practice.

- (b)

- Technical and operational: A thematic synthesis was undertaken across the academic literature, institutional reports, and legal–technical commentary, with a focus on trigger specification, operational verification of triggers and trigger data sources, data provenance and continuity, latency, basis risk decomposition (spatial, temporal, design), auditability, and dispute resolution pathways.

- (c)

- Institutional coordination: The assessment considered the coherence of mandates across disaster risk management, finance and insurance, public-sector procurement constraints, supervisory oversight, and complaint handling and redress. It also examined how, in practice, responsibilities for supervisory approval and validation of third-party trigger data sources and calculation methodologies would be allocated.

2.2. Search Strategy and Eligibility Criteria

Targeted keyword strings included “parametric insurance”, “index-based insurance”, “parametric triggers”, “trigger data sources”, “basis risk”, “claims governance”, “smart contracts”, and “legal framework parametric insurance”, as well as Slovene and Croatian equivalents (for example, “parametrično zavarovanje/parametarsko osiguranje; okidači/sprožilci; izvori podataka/podatkovni viri”). Searches were conducted across Web of Science, Scopus, SpringerLink, JSTOR, COBISS, Hrčak, and Google Scholar.

Inclusion criteria comprised thematic relevance, methodological clarity, and substantive treatment of risk-transfer mechanisms, basis risk, or claims governance.

Exclusion criteria comprised non-credible non-peer-reviewed sources (except official publications by governments or supervisors), purely promotional content, duplicates, items outside the language scope, and preprints without a subsequently peer-reviewed version. Grey literature was cross-referenced against peer-reviewed sources and retained only where citable and attributable to competent public authorities or standard-setting bodies. Publicly accessible stakeholder reports and supervisory publications were included if issued by competent authorities or standard-setting bodies and citable. Unpublished or non-citable materials were excluded.

Table 1 summarises the corpus of 91 sources used in the structured qualitative review, disaggregated by source type to ensure transparency of data provenance.

Table 1.

Composition of the reviewed corpus by source type.

2.3. Data Handling and Synthesis

A predefined extraction template captured jurisdiction and peril, trigger concept, operational verification of triggers and trigger data sources, data provenance, basis risk treatment (spatial, temporal, design), claims governance and dispute resolution arrangements, consumer disclosures, requirements for supervisory approval and validation of third-party trigger data sources and calculation methodologies, and supervisory oversight. The extracted items were tabulated to facilitate a like-for-like comparison across Slovenia and Croatia within the three-perspective framework described above. Table 1 and Table 2 summarise the composition and temporal trend of the reviewed sources, forming the empirical basis for the three-perspective comparative framework.

Table 2.

Temporal distribution of peer-reviewed sources.

Table 2 illustrates the growth of peer-reviewed publications on parametric insurance and related regulatory topics, with a marked acceleration after 2020, reflecting heightened academic and policy attention to disaster risk financing.

2.4. Transparency Notes

All screening decisions were recorded against the predefined criteria. Where currency conversions were necessary in 2023–2024 sources, Banka Slovenije annual averages were used. For HRK–EUR conversions, the official fixed euro changeover rate (1 EUR = 7.53450 HRK) was applied. Conversions are stated immediately after each quantitative figure in the text.

All quantitative figures reported in Section 3 were cross-checked against the cited primary sources, with currency conversions applied as specified in this section to ensure traceability and consistency.

3. Disaster Impact in Slovenia and Croatia

This section consolidates verified figures for recent flood and earthquake events and expresses insurance coverage in simple ratios to support the later feasibility analysis. A single comparative table and one figure are used to avoid repetition and to present the key magnitudes succinctly. Coverage ratios are reported against clearly stated denominators (direct damages, total losses, or needs) to ensure comparability. The relevance for sustainability is that a low insurance take-up amplifies fiscal volatility and delays transparent, rules-based recovery finance, which affects the equity and predictability of post-disaster support. The consolidated figures are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3.

Consolidated impacts of recent disasters in Slovenia and Croatia (coverage ratios by stated denominator) *.

Although these events are extreme, both countries have a documented history of flood and seismic exposure, so the 2020–2023 sequence should be interpreted within a longer regional hazard pattern rather than as an isolated outlier [7,8,29].

3.1. Slovenia: August 2023 Floods

In August 2023, Slovenia experienced the most severe flooding in its recorded history. Official meteorological reports documented an exceptionally high rainfall during 3–6 August 2023. In the 24 h period ending 08:00 on 4 August, multiple ARSO gauges recorded more than 200 mm of rain in northern and western Slovenia; over the 72 h to 08:00 on 6 August, most of the country accumulated between 100 and 300 mm. For orientation, 200 mm equals 200 L per m2 (0.2 m3 per m2) [30]. Units follow the meteorological convention: 1 mm of rainfall equals 1 L per m2 (0.001 m3 per m2).

According to the official government assessment, the total direct damage was estimated at approximately EUR 3.0 billion [31]. However, a peer-reviewed post-disaster needs assessment (PDNA) by Bežak et al. [7] placed the combined economic impact, including direct and indirect damages as well as recovery needs, at approximately EUR 9.9 billion, equivalent to 17.36% of Slovenia’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2022, which was officially recorded at EUR 57.038 billion [32]. By 24 July 2024, the Slovenian government had allocated EUR 805 million for recovery efforts [31]. In 2023, insurance companies paid out EUR 335 million in claims for disasters triggered by natural hazards, of which EUR 150 million was explicitly attributed to the August floods [9].

Following the final damage assessments, the Government adopted a five-year reconstruction programme of approximately EUR 2.33 billion covering water and municipal infrastructure, landslides, the reconstruction of residential and business buildings, replacement construction, and the restoration of cultural monuments and protected areas (of which EUR 1.36 billion was for watercourses). In addition to this programme, separate allocations were provided for state roads and railways (EUR 824 million), for economic recovery (EUR 230 million), and for primary agricultural production, fisheries, and aquaculture (EUR 5 million) [31].

Relative to direct damages (≈EUR 3.0 bn), paid claims (≈EUR 150 m) imply ≈5% coverage; relative to the PDNA total (≈EUR 9.9 bn), the implied coverage is ≈1.5%, revealing a significant protection gap. The remaining recovery burden fell on public mechanisms, underlining the absence of scalable, pre-disaster financial risk-sharing instruments in Slovenia. This pattern is consistent with cross-country evidence that a large share of the disaster-related losses remains uninsured [5]. These magnitudes are material for sustainability because a low insurance take-up increases fiscal volatility and delays transparent, rules-based recovery finance, both of which are concerns of sustainability governance [5,6]. For illustration only, a flood trigger in Slovenia could reference official ARSO observations, for example, a 24 h rainfall of ≥200 mm recorded at an official ARSO gauge within the insured municipality, or a river-stage exceedance of the red-alert threshold at the designated ARSO station. The trigger uses time-stamped, public observations and avoids probabilistic inference [30,33].

3.2. Croatia: 2020 Earthquakes (Zagreb and Petrinja)

In Croatia, the earthquakes that struck Zagreb (22 March 2020) and Petrinja (29 December 2020) rank among the country’s most severe disasters caused by natural hazards. The Zagreb earthquake had a local magnitude (ML) of 5.5 (moment magnitude, Mw 5.4–5.5), with its epicentre approximately 7 km north of the city centre and a focal depth of 10 km [8,29]. The maximum reported intensity in the city reached approximately VII on the EMS (European Macroseismic Scale), as reported by the Croatian Seismological Service at the University of Zagreb [34]. It affected more than 25,000 buildings, particularly in the historic city centre [8,29]. By September 2020, insurers had settled over 6000 claims, disbursing approximately HRK 200 million (≈EUR 26.6 million at the official fixed exchange rate of HRK 7.53450 per EUR 1 (ECB)) [35].

According to Uroš et al. [8], the total damage from both events was estimated to be over EUR 16.1 billion, whereas the reconstruction needs exceeded EUR 25.9 billion. For Zagreb alone, the damage was assessed at EUR 11.3 billion, with projected reconstruction costs surpassing EUR 17.5 billion. Insurance companies disbursed between HRK 400 million and HRK 500 million (≈EUR 53–66 million at the fixed conversion rate HRK 7.53450/EUR 1) for the Zagreb event, resulting in an insurance coverage rate of <0.6% against direct damages [8,36]. These damage figures primarily reflect direct physical losses to residential, public, and cultural buildings, affecting up to 25,000 structures and displacing 30,000 people. These findings are broadly consistent with the engineering-based assessment of Atalić et al. [29], who reported that over 1700 experts conducted more than 50,000 field inspections following the earthquake. Based on this effort and using the World Bank’s post-disaster needs assessment methodology, Atalić et al. noted that the costs required to achieve the full reconstruction of damaged buildings and infrastructure were estimated to exceed EUR 10 billion. In contrast, direct renovation needs were estimated at EUR 1.2 billion. These micro-level engineering estimates complement the macro-level (economy-wide) quantifications rather than contradicting them.

The Petrinja earthquake resulted in an estimated economic loss of EUR 4.8 billion, whereas the recovery and reconstruction needs totalled approximately EUR 8.4 billion [8,37]. Because insurance payout data for the Petrinja earthquake are not systematically reported, the financial response is known mainly from public aid: the Croatian government provided HRK 120 million (EUR 15.9 million) in direct assistance, plus HRK 101.5 million (EUR 13.5 million) for housing reconstruction (both amounts converted at the official fixed exchange rate (ECB)) [35,38,39]. Recent comparative evidence indicates that a low catastrophe insurance take-up and sizeable protection gaps are persistent features in small economies, which contextualises Croatia’s reliance on public transfers [5,6]. In parallel, digital advances in conventional claims handling, including satellite-, SAR-, and drone-assisted workflows, have accelerated indemnity assessment and narrowed any pure speed advantage of parametric designs [4], reinforcing the need to prioritise verifiability, predictability, and auditability in any proposed parametric scheme.

3.3. Measurement Infrastructure and Suitability for Parametric Triggers

Both flood and earthquake perils are amenable to parametric models that rely on objectively measurable physical triggers. In Slovenia, real-time hydrological and seismic data from the Slovenian Environment Agency (ARSO) [33] underpinned the hydrological assessment by Bežak et al. [7], which supports the operational feasibility of parametric mechanisms based on official public sources (for example, ARSO/DHMZ/Croatian Seismological Survey) and independently verifiable calculations. In Croatia, the Croatian Meteorological and Hydrological Service (DHMZ) [40] provides granular rainfall and river-gauge data. At the same time, the Croatian Seismological Survey (Faculty of Science, University of Zagreb) [41] maintains the national seismic monitoring network.

Atalić et al. [29,37] explicitly relied on these seismic data to derive earthquake parameters, demonstrating the institutional availability of calibrated trigger variables for potential parametric instruments. For Croatia, seismic triggers can be operationalised using data from the Croatian Seismological Survey at the Faculty of Science, University of Zagreb. This survey operates the national seismograph and accelerograph networks and determines the event’s origin time, location, and magnitude, subject to the operational verification of triggers and trigger data sources.

For illustration only, an earthquake trigger for Zagreb could be defined as an officially reported shaking intensity of EMS VII or higher within administrative boundaries, as reported by the Croatian Seismological Service. This uses a public, accredited source and avoids probabilistic inference [34].

Triggers may be specified based on parameters such as moment magnitude (Mw) and peak ground acceleration (PGA). For both perils, feasibility depends on data continuity, calibration, and standardisation policies (including version-controlled backfilling), which directly affect trigger reliability and perceived fairness. In summary, the scale of uncovered losses and the presence of official, high-frequency observations indicate a clear protection gap. They also provide the measurement infrastructure needed for verifiable, auditable parametric triggers, including official public sources (for example, ARSO/DHMZ/Croatian Seismological Survey) and independently verifiable calculation methodologies, which are addressed later in the legal framework section. These impact metrics are observable over time and are reused later to quantify the residual protection gap and motivate the parametric trigger design.

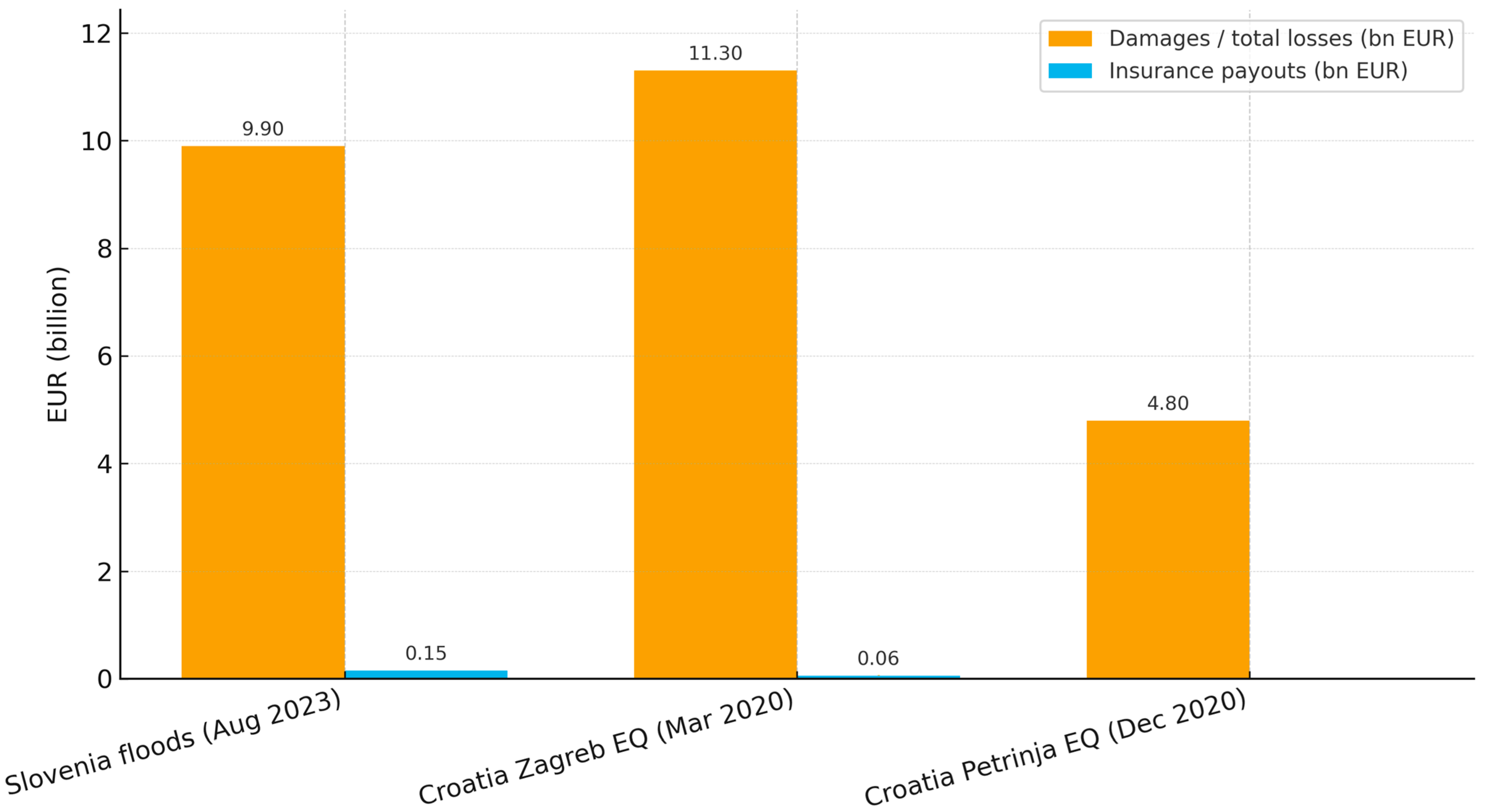

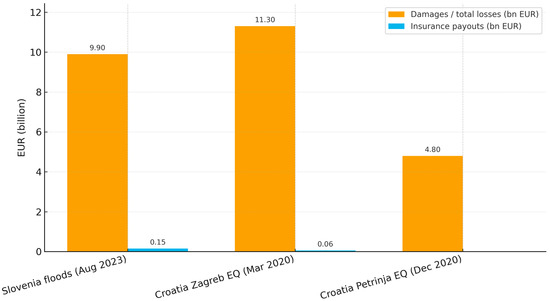

The scale of damages and the corresponding insurance payouts for these events are illustrated in Figure 2, which compares total losses and insurance payments for the 2023 Slovenia floods and the 2020 Zagreb and Petrinja earthquakes.

Figure 2.

Losses and insurance payouts for recent catastrophic events in Slovenia and Croatia. Note: Slovenia shows PDNA total losses (EUR 9.9 bn) [7]; direct damages were EUR 3.00 bn [31]. Zagreb 2020 payout is shown at the midpoint (≈EUR 0.06 bn) with an error bar covering ≈ EUR 0.053–0.066 bn [35]. No consolidated payout was identified for Petrinja 2020 in peer-reviewed sources [8]. HRK→EUR conversions use the official fixed changeover rate 1 EUR = 7.53450 HRK [42]. “EQ” in the figure denotes earthquake.

4. Global Disaster-Related Economic Losses

The increasing frequency and severity of disasters caused by natural hazards, along with the limited uptake of catastrophe insurance, have created a widening protection gap. This structural disconnect between risk exposure and financial protection is not exclusive to developing nations but also affects fiscally constrained EU member states, including those in southern and eastern Europe.

In 2023, non-life insurance claims increased across several regions. OECD [5] attributes the rise to a range of events, including floods in central Greece, storms and floods in Slovenia, a hurricane in Mexico, a landslide and storm in Norway, an earthquake in Türkiye, and a drought in Uruguay. These examples are drawn from supervisory data and illustrate a cross-country heterogeneity in reporting and attribution.

A comparison of disaster-related economic losses between 2023 and 2024 highlights both continuity and divergence in global risk exposure and insurance coverage. The summary below draws on publicly available data from Swiss Re, Munich Re, and Aon [1,2,4]. For 2023, figures are taken from Swiss Re and Munich Re; for 2024, figures are taken from Munich Re and Aon. These series indicate orders of magnitude and insured–uninsured splits.

In 2023, the estimated total economic losses from natural hazards reached USD 280 billion (≈EUR 258.95 billion at the 2023 average rate 1 USD = 0.9248 EUR [43]). According to the Swiss Re Institute’s sigma report [2], approximately USD 108 billion of the total was insured, resulting in an uninsured share of about 62%. Munich Re [4] reported a slightly lower estimate of USD 268 billion (≈EUR 247.85 billion at the same 2023 annual rate), of which USD 106 billion (≈EUR 98.03 billion) was insured, implying a roughly 60% protection gap. These differences reflect variations in the data scope and method, but consistently indicate a substantial uninsured share.

In 2024, Munich Re [4] estimated the total economic losses at USD 320 billion (≈EUR 295.55 billion at the 2024 average rate 1 USD = 0.9236 EUR [44]). Of this amount, approximately 56% was uninsured. The year ranked the third highest for insured losses and the fifth highest for total economic losses globally since 1980. Aon [1] reported an even higher estimate of USD 368 billion (≈EUR 339.88 billion at the same 2024 annual rate), attributing the primary share of losses to major Atlantic hurricanes, widespread flooding across Central and Western Europe, and severe convective storms in the United States. Methodological discrepancies between series mean that the results are complementary rather than directly reconcilable.

Although the reported uninsured share appears lower in 2024 than in 2023, this difference results from methodological divergence rather than from a demonstrable shift in structural conditions. The underlying factors that drive the protection gap, limited market penetration, insufficient risk pricing, and uneven public–private coordination remain substantively unchanged. As established at the beginning of this section, global patterns consistently reveal a growing misalignment between accelerating disaster risk and the availability of financial protection.

Despite regional variations and discrepancies in estimation methods, the reviewed data indicate a persistent systemic underinsurance, whereby formal risk-transfer mechanisms do not adequately cover a large portion of economic losses.

This trend reinforces the analytical premise of the article: Slovenia and Croatia, given their exposure profiles and comparatively low insurance uptake, face conditions that warrant a critical examination of alternative instruments. Parametric insurance, while not a panacea, emerges in this context as a potentially relevant complement to existing frameworks, provided that its design reflects both the technical viability and the institutional context. These global patterns provide the comparative backdrop against which this article assesses whether innovations, such as parametric insurance with automated triggers and supervisory approval and the validation of third-party trigger data sources and calculation methodologies, could reduce the protection gap in small EU markets.

The consolidated comparison of global disaster-related economic losses for 2023 and 2024 is summarised in Table 4.

Table 4.

Global disaster-related economic losses (concise) *.

5. Parametric Insurance: Opportunities and Constraints

5.1. Advantages of Parametric Insurance and Its Technical Preconditions

Parametric insurance is increasingly presented as a flexible alternative to indemnity-based coverage, particularly in contexts where a high disaster exposure intersects with a limited catastrophe insurance take-up. Several studies emphasise its potential benefits, including improved liquidity, simplified replication in similar risk contexts, and faster claim settlement [45,46]. However, these advantages are contingent on robust data infrastructure and institutional capacity, including approved trigger data sources, validated calculation methodologies, and the operational verification of triggers, which are not uniform. Other scholars highlight persistent constraints, such as high upfront costs for data acquisition, geographic specificity that limits scalability, and technical limitations in model calibration due to non-homogeneous or low-resolution input data [47]. This fragmentation of input data introduces not only calibration issues but also fundamental questions of epistemic reliability, namely, whether parametric models genuinely reflect underlying risk distributions or instead reproduce statistical artefacts of risk. In insurance economics terms, relevant determinants include the basis risk, adverse selection, moral hazard in prevention incentives, and ambiguity aversion on the demand side. Empirical evidence shows that a higher ambiguity aversion reduces the uptake of parametric/index-based insurance [46,47,48,49,50,51].

Cousaert et al. [52] argue that the insurance sector must respond to emerging technological risks, reconfigure traditional hazard paradigms, and meet shifting user expectations. They propose increased transparency, traceability, and programmability, objectives sometimes associated with blockchain-based tokenised insurance models. In this paper, automation is treated strictly as an optional execution layer, usable only where legal enforceability and consumer protection are demonstrable under applicable contract and insurance law, with clear supervisory expectations on governance and auditability [15,53,54,55]. In the contexts of earthquakes and floods, feasibility depends on objective and accredited triggers and stable observation networks, rather than on peer-to-peer architectures. Accordingly, basis risk mitigation is addressed through trigger design approaches documented in the literature [12,56,57].

Parametric insurance has nonetheless seen a selective application in high-risk sectors that require rapid, objective, and scalable risk-transfer instruments. In agriculture and renewable energy, it mitigates production volatility by linking payouts to predefined weather indices. For earthquakes and floods, basis risk mitigation relies on trigger specification (for example, cat-in-a-box and cat-in-a-grid spatial trigger layouts used to reduce spatial basis risk), multi-parameter or event-definition choices, and portfolio aggregation, supported by stable observation networks [12,56,57]. Basis risk refers to the discrepancy between index triggers and actual losses sustained, a misalignment that may result in partial or excessive compensation even when event thresholds are met. The demand for parametric cover is further shaped by trust, the perceived fairness of triggers, and the willingness to purchase, which are central for uptake in small EU markets [48,58].

In addition to climate-related hazards, parametric structures are being tentatively explored in cybersecurity to address aggregate IT risks. Index-linked instruments, such as catastrophe bonds and loss warranties, have been proposed as tools to transfer systemic exposure to capital markets, contingent upon clearly defined performance metrics [59].

The protection gap, defined as the difference between total economic losses and insured losses, remains a core rationale for parametric insurance [60]. Lin and Kwon [46] argue that parametric models may help narrow this gap by reducing transaction costs and expanding coverage to previously uninsurable risks. However, these benefits are highly contingent upon the availability of granular, real-time data and robust monitoring infrastructure. The initial deployment costs, including investments in sensor networks and actuarial calibration, pose significant scalability barriers, particularly in jurisdictions with fragmented institutional authority or inadequate data systems. For Slovenia and Croatia, technical preconditions therefore include verifiable and time-stamped trigger datasets from accredited sources, version control and data-freeze policies for audits, documented sensor quality assurance, and transparent consumer disclosures on basis risk and dispute options [15,33,40,41,55].

Where AI components are used in pricing, risk selection, or claims workflows, GDPR [26] and, if in scope, the AI Act [27] impose governance, transparency, and oversight requirements. A consolidated summary of advantages and constraints is provided in Table 5.

Table 5.

Advantages and constraints of parametric insurance.

Because uptake hinges on perceived fairness and trust in triggers, Section 5.2 examines the structural and ethical limits that shape demand. Theoretically, the demand for index-based/parametric products typically decreases when basis risk is present or when there is uncertainty about trigger performance (ambiguity) [22,23,24], which justifies the emphasis on verifiability, disclosures, and fairness tests for triggers.

5.2. Structural Challenges and Ethical Limits of Parametric Insurance

Broberg stresses that parametric models offer liquidity but are not substitutes for indemnity insurance. The effectiveness of these methods is constrained by the erosion of predefined trigger validity over time, particularly in volatile environments. A frequently cited example is the 2016 Malawi drought, where mis-calibrated triggers—rooted in inaccurate cropping assumptions—reportedly delayed payouts and eroded confidence. Broberg critiques such models not only on technical grounds but also for their limited contextual adaptability and their failure to address distributive equity [45]. This implies that the rigour–speed trade-off must be explicitly managed in trigger design, disclosure, and ex post review. Additionally, demand frictions related to trust, perceived trigger fairness, and ambiguity aversion require attention, as evidenced by empirical studies [49,50,51].

Similar concerns are raised by Kousky, Wiley, and Shabman [48], who note that, despite the promise of parametric microinsurance to improve affordability, unresolved issues of trust, demand, and regulatory capacity continue to constrain uptake.

Field-based evaluations yield mixed results—Biffis et al. [47] report that index-based coverage improved access to credit for smallholders. However, trust deficits persist, fuelled by the opacity in trigger mechanisms and ambiguity aversion. Hobday et al. [58] go further, cautioning that poorly structured parametric tools may foster institutional dependency rather than resilience, a critique that invites scrutiny of the normative assumptions underpinning the sector. These findings suggest that community acceptance and social equity are not merely ancillary but integral design constraints that influence take-up and welfare outcomes, including in small EU markets.

Model innovations aim to mitigate these limitations. Steinmann et al. [12] propose a tripartite refinement strategy that addresses spatial misalignment (via cat-in-a-box mechanisms), temporal mismatch (via improvements to event definitions), and design uncertainty (via the integration of multiple hazard drivers). The authors also demonstrate on p. 564 that portfolio aggregation can reduce payout discrepancies, although correlated local extremes remain a structural constraint. Franco et al. [57] analyse the effectiveness of various first-generation parametric triggers for hurricane risk transfer. They find that a cat-in-a-grid trigger can reduce basis risk compared to the traditional cat-in-a-box system in the Miami case study, allowing for a greater risk coverage at the exact cost. However, they noted that such improvements depend on the availability of robust observational infrastructure and sufficient technical capacity. The implication is that rigorous trigger design can reduce basis risk but cannot, by itself, resolve legitimacy and trust constraints.

Expanding this logic to capital markets, Tavanaie Marvi and Linders [61] propose that disaster risk consists of a systematic component and an idiosyncratic component, with the systematic component being transferable via parametric catastrophe bonds. Their approach promises faster, transparent payouts and cross-regional pooling, but raises questions about market accessibility and capacity constraints. For EU issuances or placements, modelling, disclosure, and potential conflicts of interest must be governed under applicable securities and insurance rules; where insurers sponsor instruments, Solvency II model governance and risk management expectations also apply [55].

Kim et al. [13] propose a framework that couples deep learning with cost–benefit analysis to improve the prediction of losses from disasters caused by natural hazards and to guide investment targeting. Their two-part framework, SIP-1 and SIP-2, combines machine learning to predict storm and flood insurance losses with the economic evaluation of mitigation projects. While promising as a tool for long-term resilience planning, its effectiveness depends on the availability of high-quality data, computational resources, and technical expertise. Where AI is used in pricing or claims governance, EU compliance obligations and supervisory expectations on explainability and oversight apply (GDPR; AI Act, where applicable; Data Act) [6,55].

As noted by the International Association of Insurance Supervisors [6], digitalisation and AI systems offer benefits but also introduce operational, legal, and macroprudential risks that require robust governance, testing, and oversight.

5.3. Implications for Slovenia and Croatia: Actionable Preconditions

For the jurisdictions examined, opportunities depend on meeting the following verifiable preconditions, which align technical feasibility with enforceability and consumer protection [6,15,53,54,55]:

- (i)

- Documented and independently verifiable trigger sources, with version-controlled calculations and fully reproducible procedures.

- (ii)

- Insurance Distribution Directive (IDD)-aligned product governance and disclosures: These provide an Insurance Product Information Document (IPID) that includes a clear, balanced explanation of basis risk (that payouts may not match actual loss) and implement Product Oversight and Governance (POG) controls that define the target market and product testing, while also ensuring accessible complaint handling/ADR and the possibility of human review of any automated outcome (Directive (EU) 2016/97; Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/1469; Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2017/2358; Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/1257).

- (iii)

- Verification standards for trigger changes: These include formal procedures for sensor maintenance, recalibration, and backfilling, with public change logs and time-stamped version histories for supervisory audit.

- (iv)

- Pricing and model risk management: This includes documented validation, back-testing, and sensitivity analysis, with transparent uncertainty ranges for thresholds and payouts; where applicable, these align with Solvency II model governance expectations.

- (v)

- Stakeholder acceptance and willingness to purchase: These provide evidence on demand, distribution strategies, and affordability, particularly in peripheral or exposed regions, as well as pre-test basis risk disclosures and information treatments that reduce ambiguity about trigger performance before pilots are launched [49,50,51].

- (vi)

- Optional automation only where legally robust: This keeps human-in-the-loop oversight and reversibility/kill switch and comprehensive logging; allocates liability among insurer/oracle/service providers; and, where smart contract execution is used for data-sharing workflows, aligns with Data Act Article 36 essential requirements. Where a decision would otherwise be solely automated and significantly affect a natural person, this would ensure GDPR Article 22 safeguards (right to obtain human intervention and to contest the decision).

The cases of Slovenia and Croatia illustrate both structural potential and contextual fragility. Despite having an adequate data infrastructure, the low take-up of catastrophe coverage and fragmented institutional mandates pose significant constraints. International lessons suggest that successful deployment will require more than pilot schemes: a critical realignment of regulatory, infrastructural, and public trust frameworks is essential.

Moreover, any future implementation should address not only technical feasibility but also distributive equity, particularly in peripheral or exposed regions. A failure to do so risks reproducing the very protection gaps that parametric tools aim to eliminate. These preconditions map onto the article’s three-part feasibility framework—legal and regulatory compatibility (ii, vi), technical and operational viability (i, iii, iv), and institutional coordination capacity (v)—and are used in later sections to structure implementation pathways. In the next section, we translate these preconditions into jurisdiction-specific pathways for Slovenia and Croatia, indicating near-term actions, sequencing, and supervisory touchpoints.

5.4. Stakeholder Perspectives from Official Publications

Recent supervisory materials emphasise product governance, transparency, and auditability over technology labels. EIOPA [55] highlights the need for clear accountability in blockchain-oriented insurance operations; IAIS [6] underlines model risk, operational resilience, and explainability in digital claims and pricing. Domestic supervisors (AZN [62]; HANFA [63]) have not issued parametric-specific guidance, implying that IDD/IPID/POG and general contract law principles currently govern disclosures and redress. These positions align with our feasibility criteria on verified triggers, version-controlled calculations, and accessible dispute resolution.

Retrospective pilot testing using historical hydrometeorological or seismic data (for example, from ARSO or DHMZ) could offer a low-cost and legally unintrusive way to evaluate whether the proposed triggers would have aligned with past catastrophic events. This form of historical back-testing would enable a preliminary assessment of basis risk and payout adequacy, supporting future cost–benefit modelling and stakeholder dialogue without requiring an immediate deployment of live capital.

6. Parametric Insurance Legal Frameworks in the EU and Beyond

Unlike traditional indemnity insurance, parametric contracts trigger payouts based on predefined parameters rather than verified losses. This structural divergence may introduce legal ambiguity regarding contract classification, disclosure obligations, and enforceability, particularly where third-party indices or probabilistic triggers are not explicitly recognised as proxies for insurable damage. These questions concern private contractual relations, supervisory oversight, data governance, and consumer protection in automated financial services. For policy analysis, the clearer legal anchoring of triggers, disclosures, and auditability improves the measurability and transparency of post-event financing. Where personal data or machine learning components are used for pricing, distribution, or trigger governance, GDPR applies, and the EU Data Act and (where in scope) the AI Act (entered into force on 1 August 2024; phased application 2025 to 2026) impose transparency, access/usage, and oversight obligations that must be addressed in product design and supervision. Deterministic, fixed-threshold parametric triggers that merely reference official measurements (and use no machine learning) are not “AI systems” under the AI Act. However, if AI/machine learning is used in pricing, risk selection, or claims triage in ways that significantly affect natural persons, the system should be assessed for potential high-risk classification and, if in scope, comply with Articles 9–15 (risk management, data governance, logging, transparency). Compliance map (EU): (i) IDD/IPID/POG govern pre-contractual information, target markets, and product governance; (ii) Solvency II governs the system of governance (including risk management, internal control, outsourcing, and, where relevant, internal model governance) and operational resilience; (iii) the GDPR/AI Act/Data Act govern personal data processing, high-risk AI (if any), and smart contract safeguards for data sharing (safe termination, access control).

Processing in parametric workflows will typically involve non-personal environmental data. Where personal data are processed for policy issuance, distribution, or complaints handling, define a lawful basis under Article 6 and assess whether any special category data in Article 9 are implicated. If any payout or claims decision is solely automated and produces legal or similarly significant effects for a natural person, ensure the safeguards under Article 22, including the right to obtain human intervention and to contest the decision. The policy documentation should set out these safeguards in plain language [26].

If AI components are used for pricing, risk selection, or claims triage, assess whether they qualify as high-risk and implement a risk management system and data governance controls per Articles 9 and 10, with technical documentation, logging, and transparency duties as applicable [27]. Where smart contracts are used for data-sharing arrangements within the scope of the Data Act, implement Article 36 safeguards (robustness, access control, safe termination). For the automation of payouts not qualifying as Data Act data sharing, treat Article 36 as good-practice guidance rather than a legal obligation [28].

At the EU level, there is no parametric-specific legislative instrument; parametric policies are assessed under the general framework of Solvency II [25] and the insurance distribution regime. In particular, Directive (EU) 2016/97 (Insurance Distribution Directive, IDD) [64] sets horizontal conduct and disclosure duties; for non-life products, pre-contractual information must be provided in a standardised Insurance Product Information Document (IPID), and product design/distribution must comply with Product Oversight and Governance (POG) requirements (Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/1469 [65]; Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2017/2358 [66]). The POG framework was subsequently amended to integrate sustainability factors, risks, and preferences into product design and distribution governance (Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/1257 [67]).

Accordingly, cross-border products must satisfy the existing prudential and conduct requirements without harmonised standards on index accreditation or automated execution [25,55]. IDD obligations apply via national transposition; this article cites the EU instruments as the common denominator and does not analyse member state transposition acts.

According to the 2023 Global Parametric Insurance Law Guide, parametric insurance is not governed by dedicated legislation in most European countries. It instead falls under general insurance and contract law frameworks in Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Spain, and the United Kingdom [68]. This landscape raises interpretive challenges regarding the enforcement of automated trigger mechanisms and the recognition of automated payout mechanisms. It also highlights the absence of harmonised EU standards despite the cross-border relevance of parametric models.

6.1. Slovenia and Croatia

In Slovenia, parametric contracts fall under the Obligacijski zakonik (OZ; Obligations Code) [69] and the Zakon o zavarovalništvu (ZZavar-1; Insurance Act) [70]. Slovenia’s Zakon o varstvu osebnih podatkov (ZVOP-2; Personal Data Protection Act) implements and supplements GDPR at the national level, including enforcement and sanctioning rules. Referencing ZVOP-2 clarifies the competent authorities and procedural aspects during supervision [71]. The competent supervisor is the Agencija za zavarovalni nadzor (AZN; Insurance Supervision Agency) [62].

In Croatia, the relevant statutes are the Zakon o obveznim odnosima (ZOO; Obligations Act) [72] and the Zakon o osiguranju (ZO; Insurance Act) [68,73,74]. In Croatia, the competent supervisor for the insurance market is the Croatian Financial Services Supervisory Agency (HANFA), which exercises risk-based prudential and conduct requirements (HANFA, “Supervisory review process”) [63].

In both jurisdictions, parametric policies are treated under the general rules of insurance and contract law; they must meet the statutory elements of a valid insurance contract as defined in OZ/ZZavar-1 [69,70] and ZOO/ZO [72,73] (subject/risk, consideration/premium, and agreed coverage terms), rather than any separate parametric-specific regime.

At the distribution level, IDD-based duties apply to parametric offers as well: (i) the distributor’s “demands-and-needs” test and suitability/appropriateness where relevant; (ii) the provision of a non-life IPID with a clear, balanced disclosure of basis risk features; and (iii) POG controls to define the target market, product testing, and distribution monitoring (Directive (EU) 2016/97 [64]; Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/1469 [65]; Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2017/2358) [66]. Where coverage is placed exclusively on a bespoke corporate/reinsurance basis (no retail distribution), certain IDD pre-contractual artefacts (for example, IPID) may not apply; the general contract law and supervisory principles still do. Plain-language disclosures should state that payouts are index-based and may not match the actual loss, identify the official source of trigger data, and explain how to submit complaints or use ADR [64,65,66,67].

There are, however, no parametric-specific provisions in the cited statutes. Based on the publicly available supervisory materials as of 5 February 2025, no parametric-specific guidance on index accreditation, trigger verification, or automated execution is published on AZN’s (Slovenia) [75] or HANFA’s (Croatia) [63] official pages as of the stated dates. For consumer protection and auditability, this implies that any automated execution layer must be contractually reversible and reviewable, with transparent data provenance for triggers. At the same time, disclosures explicitly address basis risk under IDD/IPID/POG [15,55,64,65].

The jurisdictional summary of legal bases, supervisory authorities, and the absence of parametric-specific provisions in Slovenia and Croatia is presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Parametric insurance legal frameworks—Slovenia and Croatia.

6.2. Selected Foreign Comparators

United States (state level): In 2024, New York enacted a dedicated parametric insurance framework through A10344/S9420, amending Insurance Law § 1113 (a) (34) [76] to authorise parametric insurance and adding § 3416 to set consumer disclosure requirements (effective 12 January 2025). Section § 1113 (a) (34) recognises parametric insurance as coverage, where payouts are determined by predefined parameters measured and reported by a government agency or other approved reporting entity. Section § 3416 [77] requires prominent disclosures at the time of application, policy issuance, and renewal, including that the policy is not a substitute for property or flood insurance and that a mortgagee or loss payee may not accept a parametric policy; where placement is through an excess line broker, the broker must provide these disclosures on the insurer’s behalf. Parametric policies therefore must not be presented as substitutes for standard property insurance.

Canada (provincial level): There is no federal statute specifically on parametric insurance; provincial insurance acts permit issuance, particularly in agriculture and climate-exposed sectors [68].

Latin America (overview): DLA Piper (2023) [68] and BIS FSI Insights [78] document a heterogeneous approach: Argentina requires prior approval from the Superintendencia de Seguros de la Nación [68]. Colombia’s supervisor has expressly authorised the commercialisation of parametric insurance [79], with broader financial reporting changes in Decreto 1271/2024 [80]. Brazil’s new Insurance Contract Law was approved by Congress in November 2024, with the objectives of transparency and consumer protection (SUSEP: Superintendência de Seguros Privados (Brazil), 2024) [81]. Chile’s Ley No. 21.521/2023 promotes FinTech/innovation but does not explicitly regulate parametric insurance, so products are assessed under general insurance law [68,82]. Where bespoke parametric statutes are absent, products are issued under general insurance law with supervisory vetting [68,78]. Beyond Latin America, Puerto Rico, Uganda (Insurance (Index Contracts) Regulations 2020), and Uruguay have bespoke index/parametric instruments, providing clearer statutory anchoring for trigger definition and disclosures [78].

While Slovenia and Croatia currently treat parametric contracts as standard insurance variants, material gaps persist in trigger validation, data-source accreditation, and the enforceability of algorithmic payouts. Targeted, minimal measures are therefore advisable as next steps, such as supervisory guidance, light-touch statutory amendments on index verification protocols, standardised consumer disclosures, and governance/oversight of trigger changes and automated execution. These steps increase legal certainty and consumer protection without system-wide reform and align with cross-jurisdictional supervisory expectations on transparency and auditability [15,54,55,68]. For EU market alignment, implementing IDD/IPID/POG explicitly for parametric products (with basis risk-specific disclosures and target market definition) would operationalise these measures in Slovenia and Croatia pending any future parametric-specific statute (Directive (EU) 2016/97 [64]; Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/1469 [65]; Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2017/2358 [66]).

7. Smart Contracts in Parametric Insurance

7.1. Automating Parametric Payouts with Smart Contracts

Smart contracts, articulated initially by Szabo in 1996 [83] as self-executing agreements, can automate parametric payouts when predefined trigger conditions are met. In a parametric insurance context, once an objective index (for example, flood level or earthquake magnitude) crosses a threshold, the code can execute a payout without a traditional loss adjustment step [16,84]. Smart contracts are an optional execution layer: the legally binding policy remains the natural-language insurance contract, and any code merely automates performance.

In Slovenia and Croatia, where recent floods and earthquakes have underscored the need for rapid relief, such automation could, in principle, leverage existing monitoring infrastructures (ARSO hydrology/seismology; DHMZ meteorology; Croatian Seismological Survey). Internet of Things (IoT) sensors and trusted data oracles (i.e., secure data feeds bridging off-chain sources to on-chain code) can supply time-stamped environmental observations (rainfall, discharge, peak ground acceleration) into the smart contract logic to trigger payment when thresholds are breached [84,85]. Correctly specified, this can reduce administrative overhead and speed up liquidity, valuable for post-event recovery, while retaining supervisory visibility. In our framing, automation supplements parametric execution; it does not eliminate the need for human oversight, complaint handling, or supervisory review [54,55,86].

7.2. Governance Challenges and Safeguards in Smart Contract Execution

A smart contract’s determinism (code executes exactly as written) is double-edged: it helps prevent arbitrary tampering, but it can also lock in unfair or erroneous outcomes with absent safeguards. The smart contract code is only a performance mechanism; the enforceable obligations are those expressed in the policy wording. Disputes revert to ordinary legal and supervisory processes [54,55]. Accordingly, policy terms must specify triggers, data sources, error handling, and an appeal path (including human intervention) if a result is contested, with clear disclosures of basis risk (meaning an explicit explanation of cases where the payout might not match the actual loss) via the IDD/IPID/POG regime Directive (EU) 2016/97 [64]; Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/1469 [65]; Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2017/2358 [66]; and Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/1257 [67]. The kill switch may be activated by the insurer under documented criteria; all actions are time-stamped, logged, and reviewable by the supervisor.

The minimum pilot controls are as follows (see also Section 5.3):

- (i)

- Documented and independently verifiable trigger sources with version-controlled calculations;

- (ii)

- A reversible settlement/override (“kill switch”) with time-stamped logs, aligned with safe termination principles where applicable under the EU Data Act [28];

- (iii)

- An explicit allocation of liability among insurer/oracle/provider;

- (iv)

- Complaints and alternative dispute resolution (ADR) routes disclosed up front.

Contract terms should allocate primary liability to the insurer for payout decisions, define the oracle provider’s warranties and limits, and set cure periods for data feed failure.

Researchers also advise using only objectively defined terms in code (avoid vague standards like “reasonable time”) and documenting sensor maintenance, recalibration, and backfilling policies to protect trigger integrity [15,87,88,89]. Operational note: Initial setup costs (programming, legal review, oracle integration) can be substantial, but operational efficiency improves over time—particularly for high-volume or multipartite arrangements [90].

The DAO episode remains a canonical cautionary tale: a re-entrancy exploit in 2016 diverted ≈ETH 3.6 million until a community restored funds through a hard fork [18,19,20,21]. For insurance, the implication is straightforward: deterministic code must operate within a reversible, reviewable legal framework that includes explicit liability, preserved audit trails, and supervisory visibility.

7.3. Legal and Regulatory Considerations Across Jurisdictions

In the EU, there are no insurance-specific statutes on blockchain or smart contracts; innovators must comply with the existing framework (Solvency II, IDD, GDPR, sectoral guidance). Under Solvency II [25], if an insurer relies on distributed-ledger infrastructure in operations, it must evidence prudent governance and operational resilience (e.g., Arts 41, 44, and 49 on the system of governance, risk management, and outsourcing), alongside applicable supervisory guidance. At distribution, IDD conduct standards (transparency, target market, fair treatment) apply equally to parametric offers; non-life products require standardised pre-contractual information (IPID) and POG controls (Directive (EU) 2016/97 [64]; Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/1469 [65]; Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2017/2358 [66]).

Where personal data or machine learning components are involved in pricing, distribution, or trigger governance, GDPR [26] applies. The Data Act [28] sets the essential requirements for smart contracts used in data sharing (robustness, access control, auditability, and safe termination); the AI Act [27] applies where systems fall in scope (for example, specific underwriting uses). Architectural choices (for example, off-chain storage of personal data with on-chain hashing) are commonly used to reconcile GDPR rights with ledger immutability [55,84,91].

At the national level, Slovenia governs through the Obligations Code (OZ) [69] and the Insurance Act (ZZavar-1) [70]; Croatia governs through the Obligations Act (ZOO) [72] and the Insurance Act (ZO) [73]. Parametric policies and any automation are treated under general insurance and contract law; the Insurance Distribution Directive (IDD) applies via national transposition. The competent supervisors are the Insurance Supervision Agency (AZN) in Slovenia and the Croatian Financial Services Supervisory Agency (HANFA) in Croatia. As of 5 February 2025, no parametric-specific guidance on index accreditation, trigger verification, or automated execution has been published by AZN [75] or HANFA [63]. From a comparative perspective, some jurisdictions are adding parametric-specific anchors (for example, New York Insurance Law §§1113 (a) (34) [76], 3416 [77] on definitions and disclosures), but most European markets rely on general frameworks [68].

Practical implication: For Slovenia and Croatia, targeted guidance (or light-touch statutory amendments) on trigger verification, standardised basis risk disclosures (IDD/IPID/POG), and the auditability/reversibility of automated execution would raise legal certainty and consumer protection without system-wide reform [6,15,54,55].

Where peer-reviewed or official sources are unavailable, illustrative industry commentary is cited with caution and does not ground any legal conclusions.

8. Discussion, Conclusions, and Future Directions

This review confirms that Slovenia and Croatia face a significant exposure to natural hazards, particularly floods and earthquakes, while maintaining structurally low levels of catastrophe insurance coverage. The 2023 floods in Slovenia and the 2020 earthquakes in Croatia produced combined economic losses of >EUR 26 billion (see Table 3 and Figure 2) [7,8,29,31,32,37]. Insurance payouts were comparatively small relative to total losses—typically ≤5% (for example, ≈5% for the 2023 Slovenian floods and <0.6% for the 2020 Zagreb earthquake)—with incomplete payout data for Petrinja 2020 [9,35,36,38,39]. These magnitudes and payout ratios are summarised in Table 3 and plotted in Figure 2. This pattern reveals a systemic reliance on ex post public funding rather than prearranged financial risk-transfer mechanisms. Taken together, these findings substantiate the article’s core motivation: the persistent protection gap and its fiscal implications in small EU markets. By pre-arranged, transparent, rules-based payouts, parametric solutions can smooth fiscal shocks and support sustainable, accountable post-event finance.

Parametric insurance has been proposed as a possible complement to conventional indemnity-based models, particularly for sudden-onset events with quantifiable physical triggers. Both Slovenia and Croatia maintain national monitoring systems capable of generating high-resolution hydrological and seismic data. This is evidenced by ARSO [33], DHMZ [40], and the Croatian Seismological Survey (Faculty of Science, University of Zagreb) [41], indicating that the technical prerequisites for trigger design and verification are in place. Operational readiness depends on data quality and continuity: standardised sensor maintenance/recalibration, transparent changelogs and backfilling policies, and version-controlled, reproducible trigger calculations. However, institutional fragmentation and the absence of dedicated legal provisions currently limit operational deployment. Accordingly, the present feasibility assessment prioritises trigger verifiability, data governance, and supervisory auditability over purely technical automation claims.

Neither jurisdiction defines parametric insurance as a separate category within insurance law. The existing contract and insurance legislation does not contain provisions on automated payouts, the accreditation of third-party data sources, or the validation of parametric triggers. Supervisory authorities have not established standards for such products, and interagency coordination across the risk, finance, and insurance sectors remains underdeveloped. A practical governance recommendation is to maintain and publish, once per year, an auditable risk register that records (i) trigger data availability and sensor maintenance, (ii) version-controlled calculation changes, (iii) basis risk indicators (spatial and temporal mismatch rates), (iv) complaints and dispute outcomes, and (v) reviews of legal and supervisory changes affecting disclosures and automation. This institutional environment hinders the integration of parametric instruments into national disaster risk financing strategies. These observations describe the current framework and do not imply the infeasibility of future reform. These findings align with Section 6 and Section 7: there is no parametric-specific statute in Slovenia/Croatia; EU-level instruments (Solvency II [25], GDPR [26], AI Act [27], Data Act [28]) offer only partial coverage, requiring supervisor-level guidance for index verification and automated execution.

At the European level, legislative instruments such as Solvency II [25], the GDPR [26], the AI Act [27], and the Data Act [28] provide partial regulatory coverage. EIOPA [55] has explicitly called for regulatory clarification and the coordinated oversight of blockchain-based and algorithmic insurance instruments. However, none of these frameworks include specific rules for parametric insurance with automated execution and predefined data-based triggers. This gap contributes to regulatory ambiguity, which in turn inhibits product development. In practice, this means that insurers and supervisors must currently rely on general principles (for example, the prudent person principle, conduct-of-business duties, and GDPR compliance) when evaluating index-based designs. In pilot settings, this implies a deliberate trade-off: accepting a slightly slower settlement to secure verifiability, fairness, and auditability.

Although the academic and technical literature identifies a range of potential benefits, including speed, transparency, and liquidity, practical implementation has revealed critical constraints. These include basis risk, challenges in model calibration, and reduced public trust when payouts diverge from perceived losses. From a legal perspective, core concerns include the enforceability of automated execution (validity of smart contracts), the integrity and accreditation of data sources (evidentiary standards), and consumer protection (particularly transparency and dispute resolution). Such issues are particularly salient in jurisdictions without consumer protection protocols tailored to automated instruments. In Slovenia and Croatia, the absence of a parametric-specific certification framework for triggers, data integrity verification, and automated execution contributes to legal uncertainty, even though competent supervisory authorities (AZN; HANFA) oversee insurance markets under the general framework.

While the legal architecture remains underdeveloped, the data infrastructure is in place. This creates a viable opportunity for a pilot project, drawing on existing datasets from ARSO and DHMZ to test trigger reliability and regulatory workflows without requiring full-scale commercial deployment. In addition to forward-looking pilot testing, a retrospective approach using historical ARSO and DHMZ data could be pursued as an intermediate step. Such back-testing would allow for a low-cost, legally unobtrusive simulation of how proposed parametric triggers would have responded to past disaster events (for example, 2023 floods or 2020 earthquakes). This would support early-stage assessments of trigger adequacy, basis risk, and payout mismatch before operational deployment, while strengthening supervisory dialogue and technical design. It could also support the development of supervisory protocols and inform the drafting of relevant legal amendments. The pilot evaluation should be strictly evidence-led (for example, ex ante validation and ex post audit of trigger performance) and confine automation to well-specified, objectively measurable events. Any pilot should pre-test plain-language disclosures and the complaints route with supervisory input and publish public minutes of those tests to support transparency. The minimum pilot controls follow Section 5.3 (accredited data sources, version-controlled calculations, reversible execution/kill switch with logs, aligned where applicable with safe-termination principles under the EU Data Act [28], transparent liability allocation, ADR). Pre-tested, plain-language disclosures of basis risk and trigger performance should accompany pilots to mitigate ambiguity aversion and build willingness to purchase.

A pilot scheme could, for example, be developed in Slovenia to address flood risk via data from ARSO’s precipitation monitoring network. Jurisdiction-determined rainfall thresholds within specific hydrological catchments can define trigger conditions. Payouts are automatically activated if predefined intensity levels are reached, regardless of actual damage. Such a scheme could initially cover selected municipalities with known exposure histories in collaboration with a domestic reinsurer, the Ministry of Finance, and the Insurance Supervision Agency (AZN). ARSO provides real-time meteorological inputs, while supervisory bodies can test regulatory workflows related to contract verification, payout governance, and consumer protection. This pilot is illustrative and non-prescriptive. Its sole purpose is to test verification, disclosure, and audit workflows before any scale-up. If undertaken, the pilot would include structured consultations and interviews with stakeholders (AZN, insurers/reinsurers, ARSO, municipalities/beneficiaries) to pre-test basis risk disclosures, complaint pathways, and supervisory audit protocols.

In Croatia, a pilot parametric insurance product could target seismic risk in high-exposure zones such as Zagreb or Petrinja. Operationally, such a pilot can specify triggers using Croatian Seismological Survey data, for example, thresholds based on Mw and PGA. Triggers could be tied to the Croatian Seismological Survey’s earthquake magnitude data (for example, events with a magnitude above Mw 5.5). Coverage could be offered to public institutions or vulnerable households, with the potential involvement of the Ministry of Physical Planning, Construction and State Assets, DHMZ, insurers, and reinsurance partners. In institutional terms, supervision would fall to HANFA. The pilot would enable the stress testing of technical protocols and provide a sandbox environment for regulatory authorities to assess the legal recognition and auditability of smart contract-based payout mechanisms. Where smart contracts are considered, the design should include explicit fallbacks (human-in-the-loop approval, suspension/kill switch, and standardised dispute resolution). These proposals are illustrative and intended for feasibility testing; they are not prescriptive models for immediate deployment. As with Slovenia, this concept is for sandbox evaluation only and does not constitute deployment guidance.