Abstract

Understanding cyanobacterial dominance in tropical reservoirs is crucial for water management. This study examined the dynamics of water quality in the João Leite Reservoir, situated in the Brazilian Cerrado, utilising 30 months of monitoring data from five sites. Physical, chemical, and biological parameters, including fluorometric chlorophyll-a, using multivariate statistics (Cluster Analysis, Principal Component Analysis, PCA; Canonical Correlation Analysis, CCA), were analysed alongside the Trophic State Index (TSI). Results showed temporal variations exceeded spatial differences. Cyanobacteria were dominant despite generally low nutrient levels and an oligotrophic TSI classification. Principal Component Analysis revealed that temperature is strongly associated with cyanobacterial density. However, Canonical Correspondence Analysis and correlations revealed limited direct statistical influence of measured physicochemical parameters, including nutrients, on cyanobacterial abundance. Findings suggest that in this warm, tropical system, high temperatures combined with stable hydrodynamics, resulting from long hydraulic retention times (>180 days), likely facilitate cyanobacterial success, overriding direct nutrient limitation.

1. Introduction

Reservoirs are essential structures for managing water supplies, generating energy, and supporting agriculture. Still, anthropogenic pressures are progressively compromising their water quality worldwide, resulting in problems such as eutrophication and detrimental cyanobacterial blooms [1,2]. Cyanobacteria, particularly common in tropical, subtropical, and temperate environments, can produce toxins that are harmful to human and ecological health, deplete oxygen, and increase water treatment costs [3,4,5]. Effective reservoir management relies on understanding the factors that lead to cyanobacterial dominance.

Tropical reservoirs, such as those in Brazil’s Cerrado biome, face challenges due to distinct wet and dry seasons, high temperatures, and long water retention times [6,7]. Although nutrient enrichment (phosphorus and nitrogen) from agricultural and urban runoff is a known driver of blooms [8,9], cyanobacteria can sometimes dominate even in systems classified as oligo- or mesotrophic, suggesting other roles [10]. For the João Leite reservoir, a primary source of drinking water, the prior identification of eight potentially toxic cyanobacteria species makes it crucial to understand bloom-triggering mechanisms for effective water management [11]. Further research is needed on the interaction among nutrient availability, high temperatures, thermal stratification, extended water residence times, and special biome features, such as the Cerrado [3,12,13]. Although Cerrado aquatic systems are ecologically important and vulnerable, thorough investigations on the long-term dynamics of phytoplankton communities and their environmental drivers are few [13]. Moreover, conventional monitoring techniques often lack the temporal resolution necessary to capture the rapid dynamics characteristic of these ecosystems [14,15]. By capturing short-term environmental fluctuations and responses, high-frequency monitoring using in situ probes presents an opportunity for enhanced knowledge [12,16,17].

Thus, the primary objective of this study was to examine the temporal dynamics of water quality and the phytoplankton community, comprising cyanobacteria and algae, over 30 months in the João Leite Reservoir, a water supply system in the Brazilian Cerrado. Particularly in the context of generally low ambient nutrient concentrations, we aimed to specifically (1) identify the main environmental factors (physicochemical and hydrological), (2) evaluate the interactions between environmental variables, specifically phytoplankton (cyanobacteria and algae) abundance, and (3) assess the spatiotemporal patterns of these dynamics using multivariate statistical analysis combined with in situ sensor data.

This study clarifies the ecological dynamics of tropical reservoirs in the understudied Cerrado biome, providing insights into the resilience of cyanobacteria and the variables that control their spread. The results are pertinent for designing more efficient water quality monitoring and control plans for similar systems that face seasonal fluctuations and anthropogenic pressures.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Area

The João Leite Dam is situated in Goiás, Brazil, serving as the primary water supply source for Goiânia (Figure 1). Its drainage area is approximately 765 km2. The reservoir has morphometric conditions that favour the complete vertical circulation of the water masses, in addition to presenting irregular margin characteristics, assuming a dendritic configuration and a slightly concave shape. The reservoir has an area of 10.4 square kilometres and a length of 15 kilometres. The average depth is approximately 12.4 m, and the maximum depth is 36 m, which can be affected by natural or operational variations. It has a regularised flow of 6.23 m3/s. The total volume of the reservoir is 129 hm3, with a working volume of 117 hm3 and a dead volume of 12 hm3 [7].

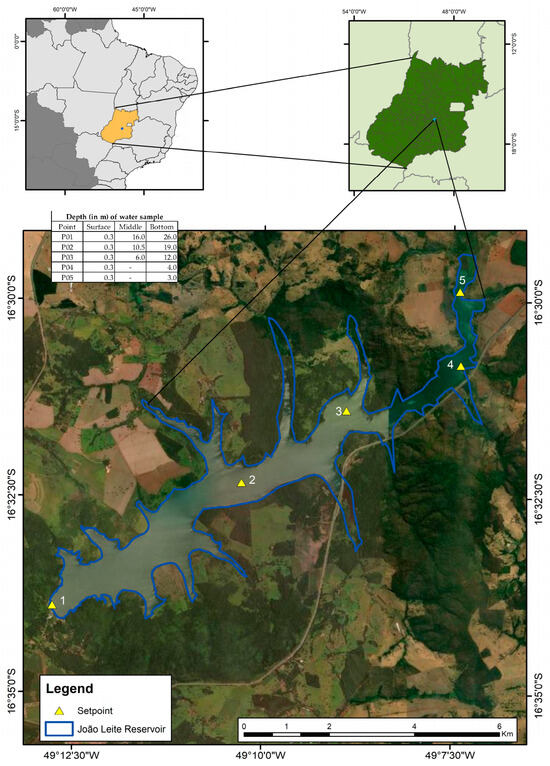

Figure 1.

Sampling points were placed along the longitudinal axis of the João Leite Dam.

2.2. Monitoring Sites and Frequency of Sampling

Five sample points, P01, P02, P03, P04, and P05, were selected and distributed throughout the reservoir. The depths at these sampling points varied along the reservoir’s longitudinal axis, ranging from shallower riverine sections to deeper areas near the dam, with maximum depths reaching up to 26 m at P05 (Figure 1). Monthly samplings, covering 30 months, were conducted from January 2015 to June 2017. Figure 1 illustrates the arrangement of the collecting locations along the João Leite reservoir [7], indicating the depth at which the water was collected at each point.

2.3. Meteorological Variables

Data on air temperature, relative humidity, precipitation, evaporation, solar irradiance, and wind velocity were collected from a meteorological station 15 km from the reservoir. According to the Köppen categorisation, as Aw, the research region exhibits a humid tropical climate with two well-defined seasons: a winter drought and a summer rainfall period [18]. The mean annual temperature is approximately 23.87 °C, influenced by the impact of altitude. The minimum temperature records are typically observed during May and August. September, which typically commences in the spring, has the highest temperatures. The mean annual precipitation is 1487.2 mm, with a minimum of 7 mm in July and a maximum of 268 mm in January [19]. The data was collected from one meteorological station representative of the study region, covering both dry and rainy seasons.

2.4. Physico-Chemical and Biological Variables of Water Quality

Water samples were collected for both laboratory analysis and in situ measurements. For laboratory analysis, sub-surface water samples (approximately 30 cm depth) were collected in borosilicate glass bottles for nutrients (total phosphorus, ammoniacal nitrogen, nitrite, nitrate), total organic carbon (TOC), total iron, manganese, and sulfate.

The protocol for gathering, preserving, conveying, and examining these water samples adhered to the guidelines outlined in [20] and the accompanying manual [21]. Phytoplankton samples were collected to obtain data for cyanobacteria and algae counts from the subsurface (approximately 30 cm depth) using a 1000 mL amber glass vial and from the middle and bottom of the reservoir (Figure 1) using a Van Dorn bottle. These samples were preserved in Lugol’s acid solution, and the quantitative analysis of phytoplankton (cyanobacteria and algae) was performed using the Utermöhl sedimentation method [20]. The identification of cyanobacteria and algae was performed using an optical microscope (Zeiss Axiostar Plus, Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with epifluorescence. The phytoplankton density, estimated according to Utermöhl (1958) [22] and expressed in units of cells per individual per volume (ind/cell·mL−1), was settled in Utermöhl counting chambers and analysed at 400× magnification. The taxonomic identification for algae was used by Bicudo and Menezes (2017) [23] and Tucci et al. (2012) [24] for the cyanobacteria and by Komárek and Anagnostidis (1999, 2005) [25,26] and Tucci et al. (2012) [24] for algae.

In situ measurements were conducted at multiple depths to assess the vertical structure of the water column using two YSI 6600 V2-2 (YSI Inc., Yellow Springs, OH, USA) multiparametric sensors. These sensors measured water temperature, pH, turbidity, electrical conductivity (EC), dissolved oxygen (DO), and, via specific ion electrodes, estimates of ammoniacal nitrogen and nitrate. The sensors also included fluorometric probes for chlorophyll-a. The time interval between collections was modified every 5 s for 5 min at each sampling location. The vertical structure of the water column was assessed as follows: measurements were taken at intervals of 2 m when the depth exceeded 10 m. When the depth was less than 10 m, measurements were taken at 1 m intervals to complete the profile.

2.5. Statistical Analyses

The statistical analysis of the data was conducted using R statistical software, version 4.5. Key R packages employed for the various analytical stages included readxl for data importation; dplyr for data manipulation; for normality testing, GGally and ggplot2 for correlation analysis and visualisation; FactoMineR and factoextra for Principal Component Analysis (PCA); ComplexHeatmap and circle for the generation of clustered heatmaps; VIM for k-Nearest Neighbours (k-NN) data imputation; and CCA for Canonical Correlation Analysis.

Initially, an exploratory data analysis was conducted using box plots to visually identify the contribution of various parameters to geographical and temporal fluctuations in water quality. In the boxplot, the graphics also plotted the points of all values of the variable. The normality of variables was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. To investigate the interrelationships among these variables, the GGally package was utilised. This package generates a matrix of plots, comprising histograms or density plots on the main diagonal, to visualise individual variable distributions, and scatter plots. The choice between Pearson (parametric) and Spearman (non-parametric) correlation coefficients was calculated, and both Pearson (r) and Spearman (ρ) coefficients were displayed for each variable pair. The statistical significance of these correlations was indicated by asterisks (* for p < 0.05, ** for p < 0.01, *** for p < 0.001) adjacent to the coefficients. Absolute correlation values > 0.50 were considered indicative of moderate to strong relationships, while values > 0.70 were deemed strong [27].

To gain a broader understanding of the inter-relationships among all numeric variables in the study, multivariate analyses were applied. This dataset was first standardised, and a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was then performed using the PCA function from the FactoMineR package (version 2.12). This dimensionality reduction technique was employed to identify principal patterns of variation within the data and to highlight the most influential variables—the contribution of each variable to the principal components and the variance explained by each component. Following PCA, a clustered heatmap was generated by using the ComplexHeatmap package (version 2.25.1). This visualisation facilitated the identification of clusters among both samples (rows) and variables (columns) based on profile similarity, graphically confirming the dynamics of water quality parameters across time and space [28,29]. The heatmap utilised the already standardised Z-score data and included dendrograms from hierarchical clustering. The heatmap legend, representing Z-scores, was customised for horizontal orientation with adjusted text size and dimensions for improved clarity. The Z-score, also known as a standard score, is a statistical measure that describes a data point’s distance from the mean of a dataset, using standard deviations as the unit of measurement. It indicates how many standard deviations a value is above (positive Z-score) or below (negative Z-score) the average, with scores near zero meaning close to the mean. This metric is key for standardising data to compare different distributions and for identifying outliers. Ultimately, it helps in understanding whether an observation is typical or exceptional within its set.

A Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) was conducted to assess the degree of association between two predefined sets of variables and to identify specific features responsible for observed correlations. The CCA was then performed using the ‘ee’ function from the CCA package. It is important to distinguish between the two main outputs of the CCA presented in the results: (1) Raw Canonical Coefficients, which are unstandardised weights used to construct the canonical variates and are not bounded by −1 and +1, and (2) Canonical Loadings (or structure correlations), which are the Pearson correlations between the original variables and the canonical variates. The loadings, which are always bounded by −1 and +1, are used for the ecological interpretation of the axes.

2.6. The Trophic State Index (TSI)

The trophic status index (TSI) evaluates the trophic conditions of different aquatic ecosystems. It was initially suggested by [30] and later modified by [31]. The TSI utilises five evaluations of trophic status. These evaluations are determined by the values obtained for three variables: transparency (measured with a Secchi disc), chlorophyll-a, and total phosphorus.

The trophic state of the study environment was assessed using only two variables: chlorophyll-a and total phosphorus. The analysis excluded transparency values because they may not accurately reflect trophic states. This exclusion is justified by the significant influence of high turbidity caused by the concentration of planktonic organisms and suspended mineral matter. Suppose there is no data for total phosphorus or chlorophyll-a. In that case, the index will be calculated using the available variable and considered equivalent to the Trophic State Index (TSI) as suggested by [31]. The results obtained from the investigation were also compared with the values provided in reference [32].

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

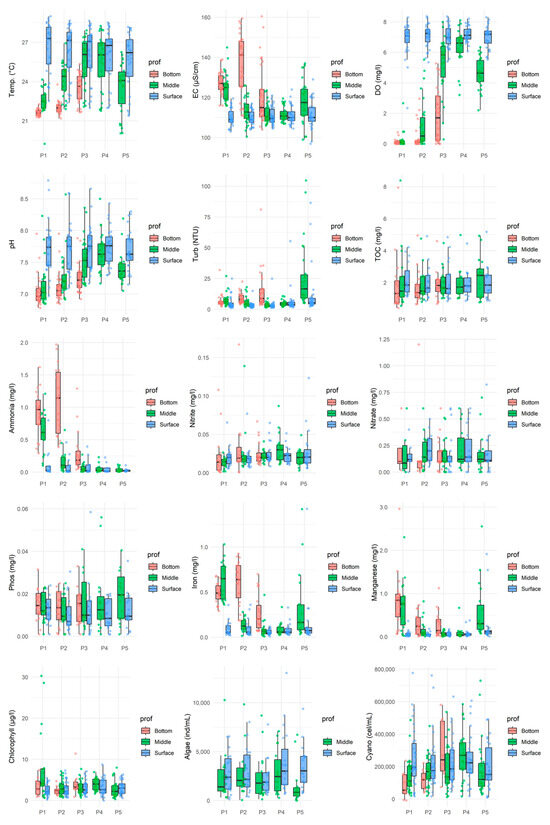

Data analysis (Figure 2 and Figure 3) revealed greater temporal than spatial variability in the surface water quality of the João Leite Reservoir during the monitored period. While the parameters assessed at the surface remained consistent across sampling locations and typically complied with regulatory limits [33], temporal fluctuations indicated apparent seasonality in water quality. Surface dissolved oxygen (DO) levels generally complied with regulations, remaining above 5 mg/L O2 and typically ranging between 5 and 8 mg/L O2, although an exception (2.34 mg/L O2) was recorded in July 2016 at point P01. DO decreased with depth, with many points indicating anoxia near the bottom, and showed temporal variations, particularly during the dry months of June and July 2016 (Times 18 and 19). The pH values consistently fell within the 7 to 8.5 range, meeting the legal limit (6 to 9 [34]), and predominantly showed neutral characteristics with a trend towards alkalinity; slightly lower values were observed in the middle and bottom layers (as defined in Figure 1) [35]. Electrical conductivity (EC) varied between 100 and 130 µS/cm, with maximum concentrations occurring predominantly in the lower section and during dry periods, decreasing during rainy seasons. Notably, values exceeding 100 µS/cm were recorded in both dry and rainy periods [36].

Figure 2.

Boxplots show the distribution of water quality parameters across all monitored months at three depths (Bottom, Middle, Surface). Individual green points represent the raw measured values at each sampling occasion.

Figure 3.

Boxplot of the parameters in all the evaluated months, considering the times monitored on the surface of the water column. Individual green points represent the raw measured values at each sampling occasion.

Concentrations of nitrogenous forms met regulatory limits for surface applications. Nitrate levels were below 0.1 mg/L (with peaks at P02 and P04 between April and June 2016/2017), while nitrite and ammonia showed the lowest concentrations at the surface. Total Phosphorus (TP) concentrations generally ranged from 0.001 to 0.025 mg/L, mainly below the legal limit for lentic environments (0.03 mg/L [28]). Still, exceptions with higher values occurred in July and August 2015 (0.031–0.102 mg/L) and in May 2015 at P03 (0.059 mg/L). Boxplot analysis revealed no significant difference in TP between sampling points, with peaks observed in August and September 2015.

Concerning metals, total iron concentrations at the surface frequently exceeded the legal limit (0.3 mg/L), with higher values found in the middle and bottom layers. Manganese levels generally met the guideline (0.1 mg/L), although occasional readings exceeded this limit.

Biological indicators showed surface chlorophyll-a concentrations ranging from 2 to 8 µg/L, within the regulatory limit (30 µg/L), with the lowest levels at P01/P02 and the highest at P04; higher concentrations were found in the central water column (P01), and levels were lower during the dry season, increasing with rainfall, contrasting with observations in [36]. High densities of cyanobacteria (10,203 to 776,835 cells/mL) were observed throughout the samples, with peak concentrations in the middle and bottom sections, especially during periods of precipitation.

3.2. Correlation and Multivariate Analysis

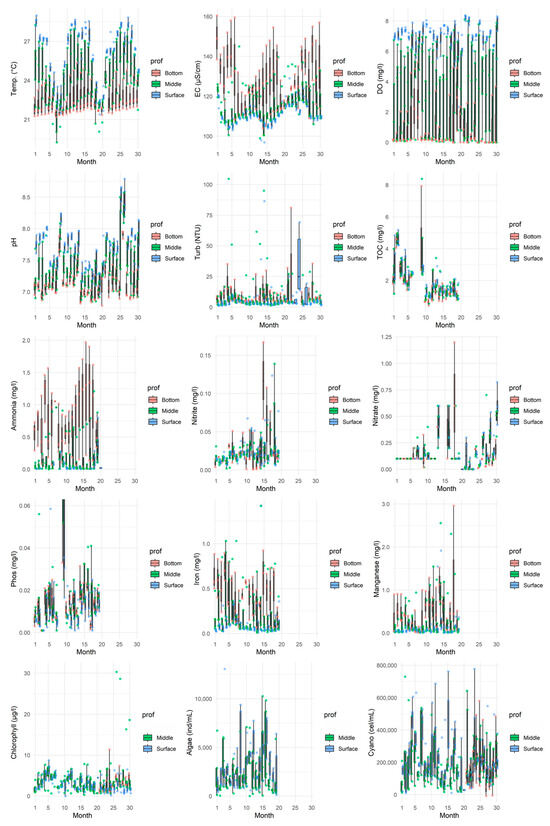

Figure 4 presents a correlation matrix that examines the inter-relationships between 16 water quality parameters. The matrix comprises three analytical components: the distributions of each variable along the diagonal, the scatter plots in the lower triangle, and the coefficients for both Pearson’s (r), which measures linear relationships, and Spearman’s (ρ), which measures monotonic relationships, in the upper triangle.

Figure 4.

Results of the Pearson correlation test for the physical and chemical parameters in the João Leite Reservoir. * for p < 0.05, ** for p < 0.01, *** for p < 0.001.

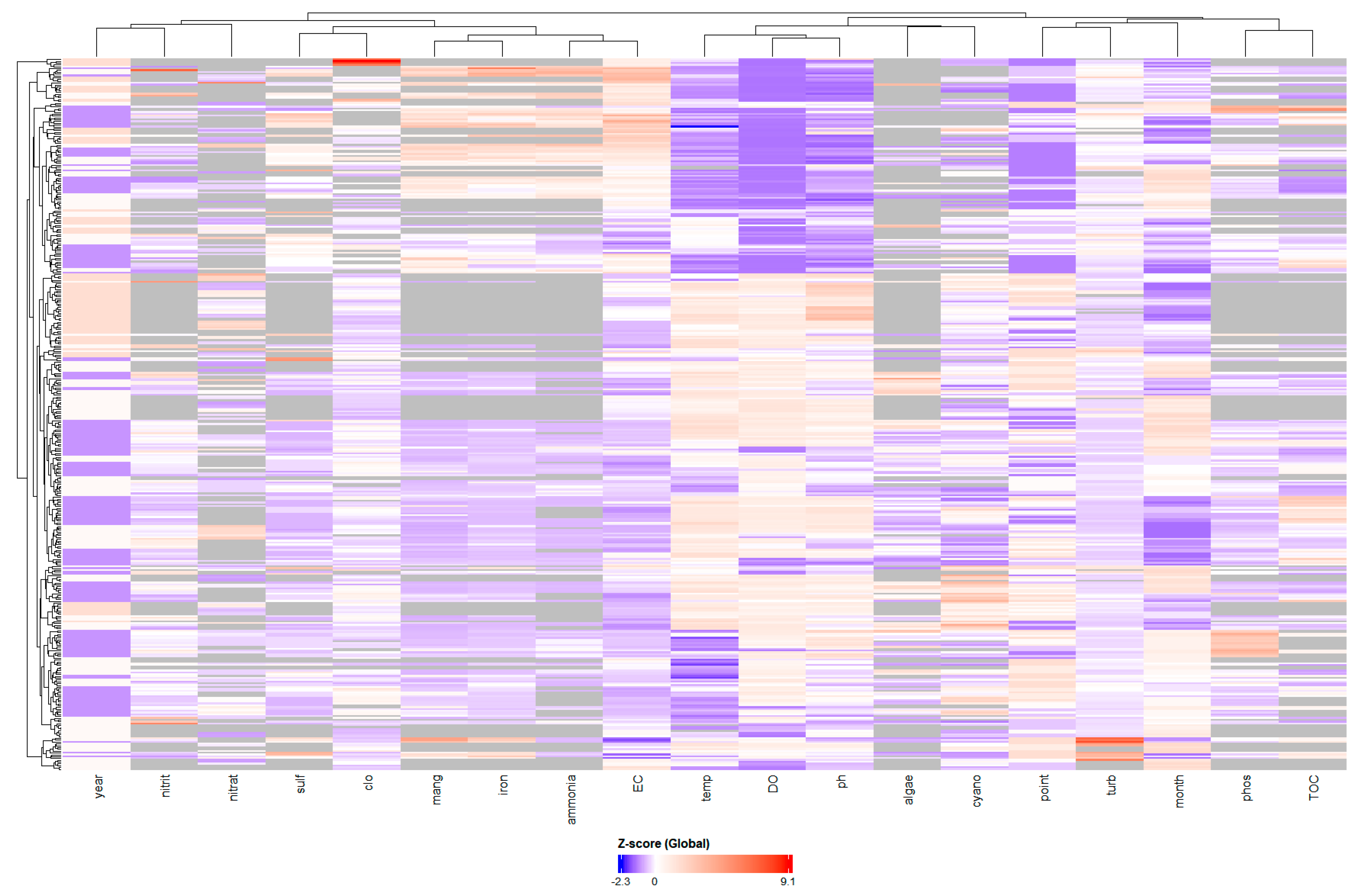

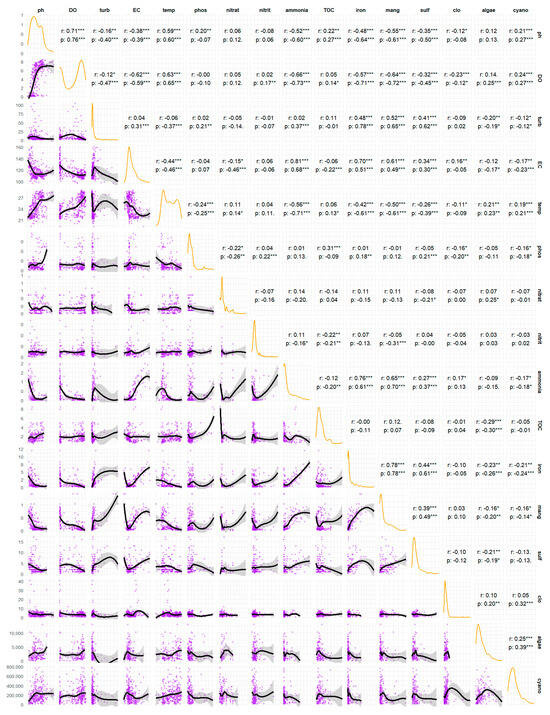

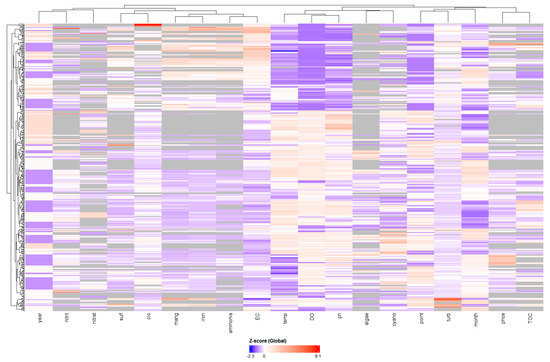

The hierarchical dendrogram in the cluster analysis (Figure 5) categorises variables exhibiting analogous variation patterns, thereby illustrating coherent clusters.

Figure 5.

Hierarchical cluster analysis heatmap of standardized water quality variables. Color intensity represents Z-scores: blue (below mean), white (near mean), and red (above mean). Dendrograms show clustering of samples (rows) and variables (columns) based on similarity patterns.

The heatmap (Figure 5) shows when and with what intensity these patterns occur, where warm colours (red) indicate high values and cool colours (blue) indicate low values.

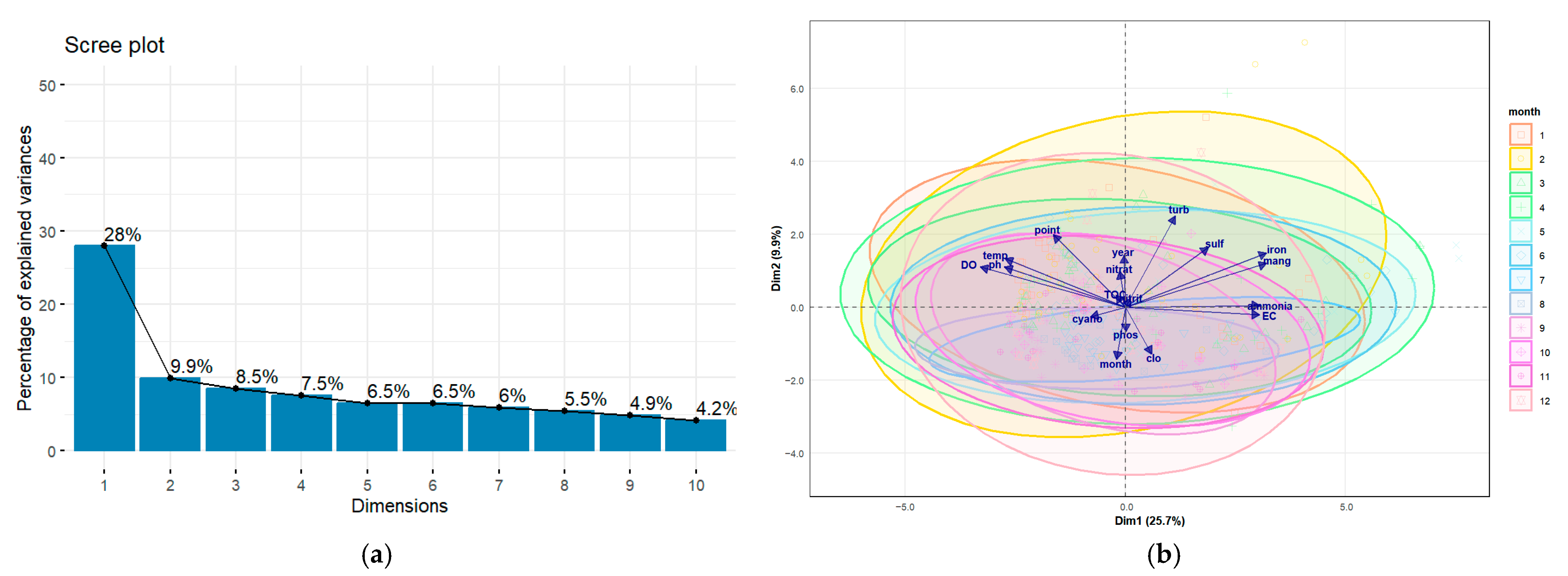

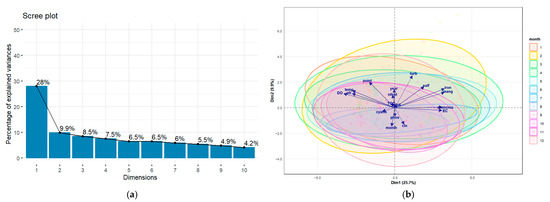

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was applied to identify the primary factors influencing water quality variation in a reservoir situated in the Cerrado region of Goiás, Brazil. The first two axes explained 37.9% of the total variability in the data (Figure 6 and Table 1).

Figure 6.

(a) variance explained in the axes resulting from PCA, (b) graphical representation of the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for the physical and chemical parameters.

Table 1.

The percentage of total variance explained by the principal components (Axis 1 and Axis 2), as well as the correlation of the parameters, is also considered.

The first axis (Figure 6a and Table 1) (Axis 1), accounting for 28% of the variance, demonstrated an opposition between, on one side, variables indicative of an oxygenated environment (dissolved oxygen and pH) and, on the other, variables associated with reduction processes (ammonia, iron, manganese) and high ionic concentration (Electrical Conductivity). The second principal axis (Axis 2), which explained 9.9% of the variance, represented an organic matter gradient, opposing living phytoplankton biomass (algae and chlorophyll-a) with detrital or dissolved organic matter (Total Organic Carbon—TOC) and suspended material (turbidity).

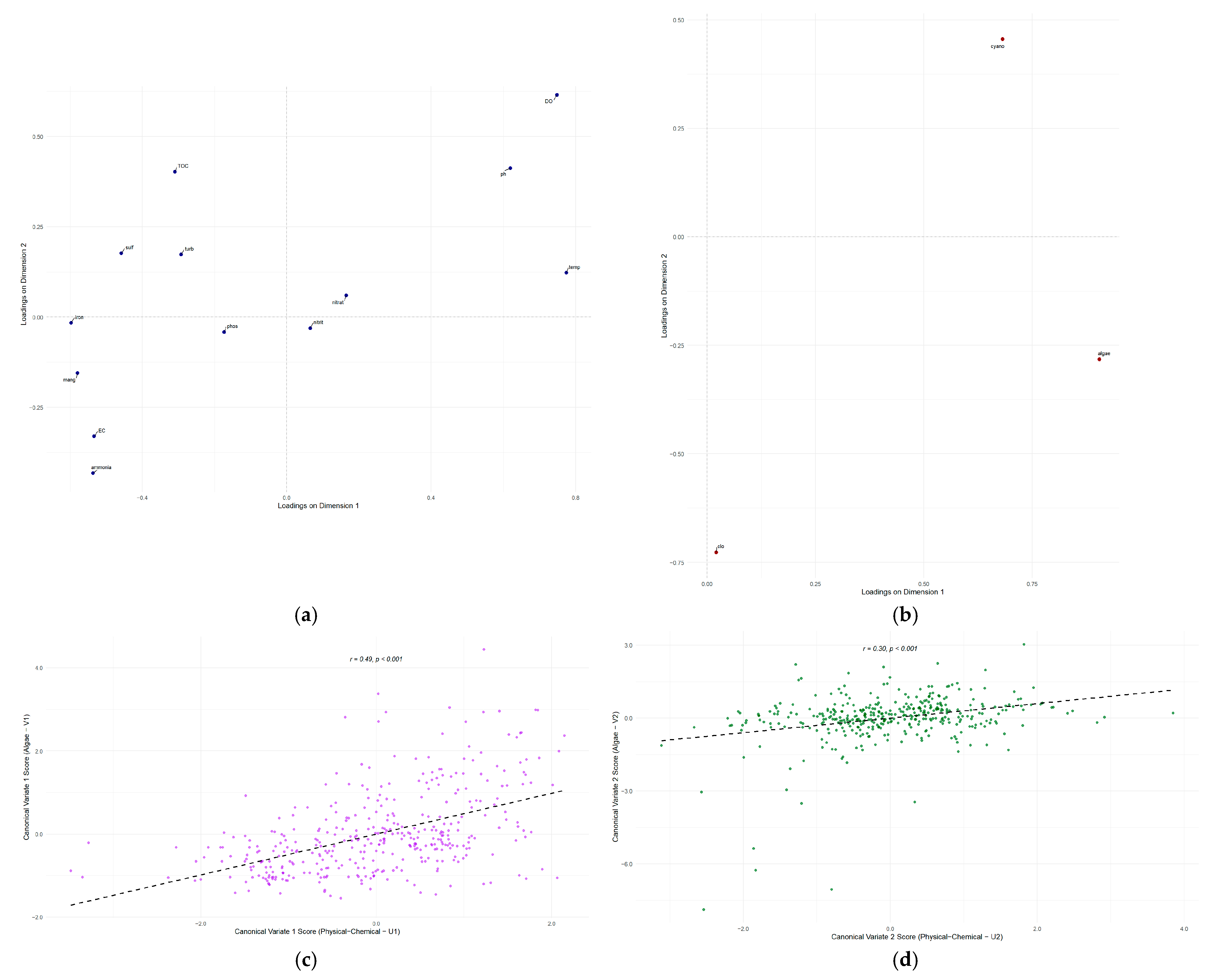

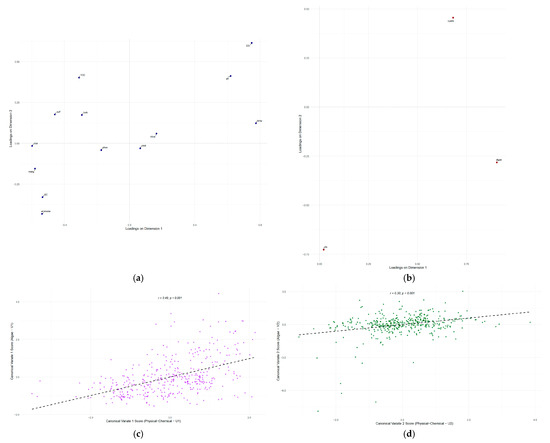

Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) was applied to investigate the relationship between physicochemical conditions and the biological community of the reservoir, which consisted of algae, cyanobacteria, and chlorophyll-a. The results showed a statistically significant correlation, with the first three canonical dimensions being statistically significant (p < 0.05), as determined by the Wilks’ Lambda test. The canonical correlations for these dimensions are r = 0.492, r = 0.299, and r = 0.258 (Table 2), respectively, with the first two providing the most relevant ecological interpretations.

Table 2.

Significance Test (Wilks’ Lambda) by Canonical Axis.

In Table 3, the first canonical dimension (V1), with a robust correlation (r = 0.492), represented the primary water quality gradient. High positive loadings were observed for temperature (0.775), dissolved oxygen (DO) (0.749), and pH (0.620), in contrast to strong negative loadings for ammonia (−0.537), electrical conductivity (EC) (−0.534), iron (−0.597), and manganese (−0.580). This dimension indicates a contrast between warm, oxygenated, high-pH waters and those with elevated concentrations of metals, ammonia, and ions. Ecologically, V1 correlated with the numerical abundance of algae (0.905) and cyanobacteria (0.682), yet remained independent of total photosynthetic biomass (chlorophyll-a loading: 0.021). This suggests that the dominant environmental factor primarily controls cell count, rather than total biomass. The second canonical dimension (V2) (r = 0.299) outlined a secondary water quality gradient. Physicochemical loadings showed a contrast between DO (0.615), Total Organic Carbon (TOC) (0.402), and pH (0.412) versus ammonia (−0.432) and EC (−0.330). Biologically, V2 highlighted a shift in phytoplankton community composition, opposing the abundance of cyanobacteria (0.455) with that of chlorophyll-a (−0.727) and other algal groups (−0.283). The third canonical dimension (V3) (r = 0.258) revealed a less prominent, albeit significant, relationship. Notable loadings included chlorophyll-a (0.686) and cyanobacteria (0.573), which were positively correlated, and phosphate (−0.519) and nitrate (−0.536), which were negatively correlated, suggesting complex nutrient-biomass interactions.

Table 3.

Raw Canonical Coefficients for the Physical-Chemical and Algae Variable Sets and Canonical Loadings (Structure Correlations) of the Variables on the Canonical Axes.

The loading plots of the physicochemical and biological variables function as a map, establishing the meaning of each canonical axis. Once the nature of these axes is established, the canonical score plots serve as the visual proof of the correlation between them (Figure 7c,d).

Figure 7.

Canonical loadings illustrate the correlation between the original variables and the first two canonical variates: (a) Phisico-Chemical. (b) Biological. Scatter plot of canonical scores for the first and most significant dimension, (c) V1 and (d) V2. The dashed line shows the linear regression fit, indicating the canonical correlation between the two variable sets.

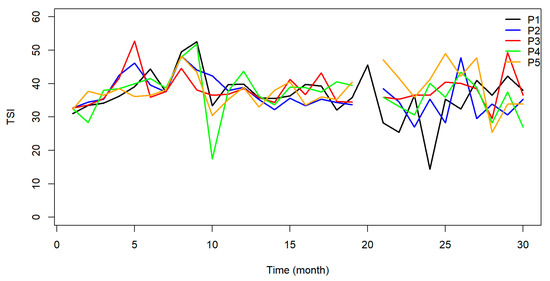

3.3. Trophic State Index (TSI)

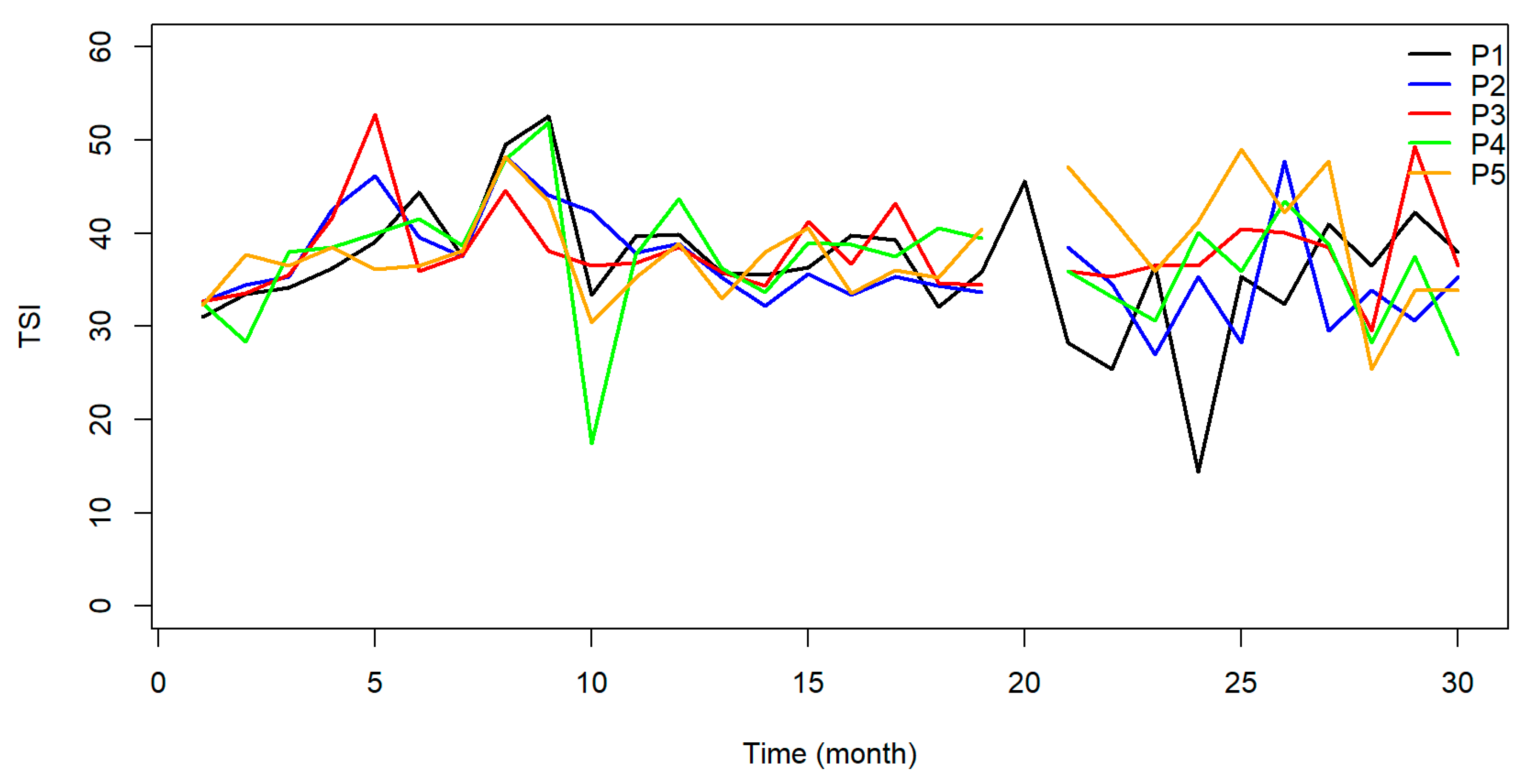

The Total Trophic State Index (TSI) indicated that 93% of the samples were classified as ultraoligotrophic, 6% oligotrophic, and 1% mesotrophic. The reservoir was classified as oligotrophic at points P01 and P02 in 2015 and as mesotrophic at P01 in September of the same year. All data points acquired over the monitoring period in the following months were classified as ultraoligotrophic Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Graphical representation of the TSI for the five sample points along the João Leite Reservoir.

When comparing the values of chlorophyll-a and total phosphorus with the values suggested in [32], which also categorise the water bodies, it is evident that 49% of the samples were classified as mesotrophic, 35% as oligotrophic, and 15% as ultra-oligotrophic for chlorophyll-a. Regarding phosphorus, 38% of the samples were categorised as mesotrophic, 35% as oligotrophic, 18% as ultraoligotrophic, and 9% as eutrophic.

4. Discussion

4.1. Reservoir Hydrodynamics and Water Quality Characterisation

The João Leite Reservoir operates as a dynamic system, with its primary characteristics influenced by seasonal variations rather than spatial differences at the surface. Water quality generally conforms to established standards [33,34]. The existence of stratification and high levels of specific parameters, such as cyanobacteria and nutrients, requires management intervention to ensure the sustainability of the water body.

Thermal stratification, a common feature of tropical reservoirs, is characterised by warmer surface waters and cooler bottom waters.

This condition is accentuated by distinct dry and rainy seasons [16]. Low dissolved oxygen (DO) concentrations near the bottom indicate that water column stability limits vertical mixing, inducing oxygen depletion (anoxia) in the hypolimnion. Anoxia, in turn, promotes anaerobic respiration and the oxidation of reducing substances in the sediments, potentially intensifying nutrient cycling (e.g., phosphorus) and metal dissolution [37]. This contributes to the chemical stratification evident in the profiles of DO, pH, electrical conductivity (EC), iron (Fe), and manganese (Mn).

Thermal stratification is characterised by higher temperatures in the upper layers (22–25 °C during dry periods; 26–29 °C during rainy periods), which decrease with depth, with minimum values recorded near the bottom [16]. Regarding turbidity, surface values were predominantly below the 5 NTU guideline for water supply [34], although the Class II limit of 100 NTU [33] was occasionally surpassed. Lower turbidity occurred during dry months, with higher values during rainy periods, culminating in a peak in December 2016 (month 24), likely due to surface runoff. Turbidity exhibited an increasing trend with depth. Stratification establishes conditions favourable for cyanobacteria dominance [17,37,38]. Elevated temperatures (>25 °C) in the epilimnion during the rainy season promote the proliferation of thermotolerant cyanobacteria species over other algal groups, specifically Chlorophyceae, Chrysophyceae, and Cryptophyceae [9,16,17]. Water column stability permits cyanobacteria with physiological adaptations, such as gas vacuoles, to optimise their position for light and nutrient acquisition [17,37].

Elevated ammonia levels were observed in the middle and bottom water column at points P01 and P02, with concentrations increasing proximally to the dam. At the bottom, bacterial decomposition of accumulated organic matter rapidly consumes dissolved oxygen, creating an anoxic environment. In the absence of oxygen, nitrification is inhibited [39]. Consequently, ammonia produced by decomposition at the bottom accumulates in high concentrations in the deep-layer water where oxygen levels are low [40].

An analysis of the main diagonal (Figure 4) indicates that most variables, including turbidity, phosphate, iron, manganese, algae, and cyanobacteria, exhibit a skewed distribution. This suggests that their concentrations are generally low but with sporadic occurrences of high-concentration peaks, a typical pattern in environmental data. The pH and the dissolved oxygen (DO) exhibit more complex distributions, suggesting the potential for distinct regimes or operating conditions within the water body.

The analysis of coefficients and scatter plots shows processes governing water quality. The most evident relationship is the strong correlation between temperature and dissolved oxygen (DO) (r = 0.63 ***, ρ = 0.65 ***). The observed positive and statistically significant correlation between water temperature and DO concentration in a lentic ecosystem contradicts the physical principle of gas solubility. This can be explained by the formation of two distinct environments within the reservoir, resulting from a combined analysis of data from two different populations: epilimnion samples (characterised by high temperature and high DO) and hypolimnion samples (characterised by low temperature and low DO). This influences the distribution of DO, concentrating it in two ranges: near zero at the bottom and near saturation at the surface [41]. The slightly stronger Spearman coefficient indicates a perfectly consistent (monotonic) relationship, though not perfectly linear, which is characteristic of natural systems [42].

An association is observed between the metals iron and manganese (r = 0.78 ***, ρ = 0.78 ***), indicating a probable shared geological origin and similar chemical behaviour. A strong positive correlation exists between ammonia and iron (r = 0.76 ***, ρ = 0.61 ***) and manganese (r = 0.65 ***, ρ = 0.70 ***). This does not imply that ammonia causes the presence of metals, but instead that all three are co-indicators of specific environmental conditions, specifically environments with low or no oxygen [43]. Under anoxic conditions (e.g., at the bottom of a lake or in sediments), organic matter decomposition occurs via anaerobic pathways, releasing ammonia (NH4). In these reducing conditions, the solid, insoluble forms of iron (Fe3+) and manganese (Mn4+) in the sediment are chemically reduced to their soluble forms (Fe2+ and Mn2+), which are then released into the water. The correlation between ammonia, iron, and manganese serves as a “fingerprint” of anoxic events, simultaneously driving the release of all three compounds [44]. Electrical conductivity (EC) acts as a general indicator of the ionic load. Its strong linear correlations with ammonia (r = 0.81 ***), iron (r = 0.70 ***), and manganese (r = 0.61 ***) confirm that events releasing these three compounds are primarily responsible for increasing the number of dissolved ions in the water. EC, to a large extent, quantifies the impact of these reducing and anoxic events.

The strong positive correlation between pH and dissolved oxygen (DO) (r = 0.71 ***, ρ = 0.76 ***) is a classic signature of photosynthesis. During the diurnal period, algae and cyanobacteria consume CO2 (increasing pH) and release oxygen (increasing DO). Turbidity, a measure of water cloudiness, correlates with manganese (r = 0.52 ***, ρ = 0.65 ***), iron (r = 0.48 ***, ρ = 0.78 ***), and sulphate (r = 0.41 ***, ρ = 0.62 ***). This indicates that a portion of these metals is likely present in particulate form or adsorbed onto suspended particles. The higher Spearman coefficient, particularly for iron, indicates a consistent relationship, albeit not perfectly linear, making it more robust against fluctuations in turbidity.

4.2. Analytical Insights into Reservoir Ecology

Cyanobacteria counts were obtained from surface samples (30 cm deep). The co-occurrence of high cyanobacteria cell counts in surface samples and comparatively low surface chlorophyll-a at times may result from vertical distribution of different groups, pigment packaging effects, or varying chlorophyll content per cell based on physiological state. However, the absence of depth-resolved phytoplankton counts and chlorophyll data from all depths limits definitive conclusions, indicating an area for further investigation. Algal density generally remained lower than that of cyanobacteria in the reservoir.

High cyanobacteria densities (exceeding 700,000 cells/mL) serve as a water quality indicator, surpassing thresholds that necessitate enhanced monitoring (>10,000 cells/mL [cf. guidelines]) due to the potential for cyanotoxin production (e.g., microcystins, saxitoxin) [17,45]. Higher temperatures can cause the production of toxins and extend bloom periods [17,45], thereby transforming seasonal events into prolonged ones. This impacts water security and public health. The predominance of cyanobacteria (typically accounting for more than 80–90% of the total phytoplankton in similar systems [46,47]) ensures the reservoir’s sensitivity to blooms.

Agricultural activities in the catchment are probable sources of nitrogen and phosphorus [13], contributing to the reservoir’s fertilisation, as suggested by other studies [13,48]. The influence of these factors was visualised through Cluster Analysis (Figure 4). The analysis revealed three functional groups whose opposition defines the ecosystem’s dynamics. The “anoxia group” (Mn, Fe, ammonia, EC, turbidity) reflects the influence of hydrogeological characteristics (Fe/Mn-rich soils) and the transport of ions and nutrients (such as ammonia from fertilisers) via surface runoff, particularly during rainy periods, which increases EC. In direct opposition is the “photosynthetic activity group” (pH, DO, temperature), which highlights the interconnection between biological activity and water chemistry. Photosynthesis increases pH and DO, whilst decomposition consumes DO and can lower pH [45,49], with both processes accelerated by temperature [13,17]. The “biological group” (algae, cyanobacteria, chlorophyll-a) represents the community responsive to these two opposing states of the reservoir. The cluster analysis demonstrated that the system’s primary dynamic is the alternation between states dominated by primary production and those dominated by decomposition and anoxia.

The result is the formation of a cohesive “anoxia group” comprising EC, ammonia, iron, manganese, turbidity, and sulphate; a distinct “biological group” uniting algae, chlorophyll-a, and cyanobacteria; and a “photosynthetic activity group” (pH, temperature, and dissolved oxygen). This clustering provides a third line of evidence for the strong inter-relationship between these variables, forming the basis of the axes of variation in the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Canonical Correspondence Analysis (CCA). Conversely, phosphorus and nitrite appear at the opposite end of the biological group, suggesting their independence from phytoplankton processes in this reservoir.

The vertical colour patterns of the heatmap (Figure 4) visually confirm the correlations, with columns within each cluster exhibiting aligned colour bands. The horizontal bands in the heatmap represent distinct “events” or periods in the reservoir. Samples (rows) corresponding to intense anoxia events are identified by the entire block of related variables (ammonia, iron, manganese) appearing in dark red. Conversely, other rows display this same block in dark blue, indicating periods of improved water quality. The heatmap also illustrates the negative correlation between the groups, as when the anoxia block is red, the dissolved oxygen and pH columns tend to be blue.

In the PCA (Figure 6a and Table 1), the positioning of months at the end of the dry season and the beginning of the wet season (September and October) at the positive end of this axis indicates peak primary production during this period. This aligns with the ecology of tropical reservoirs, where the combination of high solar radiation and nutrient influx from initial rains frequently triggers phytoplankton blooms [43]. This analysis observes a characteristic pattern in tropical reservoirs undergoing seasonal thermal stratification [50], a fundamental process described for Brazilian aquatic ecosystems by [51]. The biplot analysis (Figure 6b), interpreted in light of the Cerrado’s rainfall cycle, shows that months at the end of the wet season and the beginning of the dry season (March to June) are positioned at this anoxic pole. This suggests that, during this period, water column stabilisation and decomposition of accumulated organic matter lead to oxygen consumption in the hypolimnion, resulting in the release of reduced compounds from the sediments.

Table 2 analysis indicates that this environmental gradient correlates with a biological variate representing the numerical abundance of algae and cyanobacteria, largely independent of total photosynthetic biomass, as measured by chlorophyll-a, whose loading on this axis was negligible (0.021). This suggests that the primary environmental factor in the reservoir controls the quantity of phytoplankton cells, irrespective of the total biomass they represent. This biological axis establishes a strong contrast between the abundance of cyanobacteria (positive pole) and total biomass, represented by chlorophyll-a, and the abundance of other algal groups (negative pole).

The first loadings plot (Figure 7a) visually demonstrates the structure of the main environmental gradient (Axis 1), where opposing variables of oxygenated, warm water (DO, pH, temperature) are grouped with indicators of reducing conditions and higher ionic concentration (ammonia, iron, manganese, EC). The second plot (Figure 7b), displaying biological loadings, reveals the community’s response to these gradients: the first biological axis is defined by the numerical abundance of algae and cyanobacteria, whilst the second axis represents a compositional shift, opposing cyanobacteria dominance to that of other algal groups and total biomass (chlorophyll-a). The scatter plot (Figure 7c) for the first dimension illustrates the strongest relationship found (r = 0.492), showing a positive trend between the water quality gradient and phytoplankton abundance. The corresponding plot for the second dimension also exhibits a positive trend (Figure 7d), though visually more dispersed, consistent with the weaker yet significant correlation (r = 0.299) between the secondary environmental gradient and the community structure shift. These plots validate the CCA conclusions, demonstrating how a primary environmental gradient controls phytoplankton abundance while a secondary and independent gradient controls their composition.

Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) revealed a statistically significant relationship between physicochemical conditions and the phytoplankton community. The analysis indicated a dual control mechanism, where different environmental gradients regulate community abundance and composition. Although phosphorus is frequently the primary limiting nutrient in tropical systems [9,16,52], the low direct correlation observed between nutrients (N, P) and total phytoplankton biomass (chlorophyll-a) in simpler analyses (Pearson Correlation, PCA) can be explained by the CCA. The CCA demonstrated that the strongest environmental gradient correlated with the numerical abundance of cells (algae and cyanobacteria) but not directly with chlorophyll-a. This suggests that, during the study period, other factors such as temperature [17] and the reservoir’s long hydraulic residence time (approximately 180 days) may have served as primary growth controllers, producing consistently favourable conditions [8,53] that influence cell number more directly than total biomass. Nevertheless, observed total phosphorus (TP) peaks, particularly following dry spells, may relate to nutrient input via surface runoff or to internal release under anoxic conditions, and they remain significant for accelerating cyanobacteria development at high temperatures [9,11].

4.3. Dynamics of Phytoplankton Populations

Phytoplankton are autotrophic organisms in rivers, lakes, reservoirs, and oceans. Plants utilise sunlight, carbon dioxide, and nutrients from water to produce energy and oxygen through the process of photosynthesis. Aquatic primary producers play a crucial role in global oxygen production. Photosynthesis requires chlorophyll-a and other pigments in algae, such as those found in the Chlorophyta and Bacillariophyta. Their ideal conditions consist of a reasonable diet and enough light [54].

Algae concentrations changed without any evident pattern. Environmental factors and a thorough study of all kinds of algae may reveal hidden group dynamics. Algae were affected by dissolved oxygen levels in the water column and light availability, showing lower densities than cyanobacteria [55].

Often referred to as blue algae, cyanobacteria are another phytoplankton group characterised by unique physiological traits. Pigments called phycocyanin help certain cyanobacteria fix nitrogen. Their ideal habitat is a warm, nutrient-dense one. They can also store phosphorus (a strategy known as “luxury consumption”), control buoyancy through gas vacuoles, and survive in low-light conditions. As a result, cyanobacteria outcompete other phytoplankton [31].

These differences influence phytoplankton community dynamics. Under balanced nutrient levels, algae prevail, whereas cyanobacteria flourish in eutrophic settings or during temperature stratification, leading to hazardous algal blooms. Temperature, nutrient availability, and hydrodynamics influence this interaction [54]. Cyanobacteria concentrations demonstrated greater stability and predictability, rising during warmer months marked by elevated sunlight and temperature stratification. Natural adaptations, including nitrogen fixation and buoyancy regulation, enabled the evolution of these species in these environments. Improved water circulation and reduced thermal stratification resulted in a 50% decrease in cyanobacteria levels during the cooler months. Algae and cyanobacteria exhibited greater abundance during thermal stratification, indicating their inherent association with changes in dissolved oxygen (DO). Cyanobacteria surpassed algae due to their ability to thrive in nutrient-rich and low-oxygen environments. This behaviour underscores the necessity of monitoring cyanobacteria as an indicator of water quality and a threat to public health.

4.4. Regional and Morphological Influences

Tropical reservoirs, such as those in Brazil, are characterised by consistently high temperatures and abundant light, which promote prolonged thermal stratification. These conditions favour the dominance of cyanobacteria as extended hydraulic retention times further stabilise the water column, reducing vertical mixing and facilitating the release of nutrients from the hypolimnion to the euphotic zone. As a result, these reservoirs often endure ongoing and repeated cyanobacterial blooms, presenting significant challenges for water quality management [16,17,45].

This contrasts with temperate regions, where seasonal variability is more pronounced, and increased summer temperatures promote thermal stratification, leading to the temporary dominance of cyanobacteria. Wind-induced vertical mixing and the shorter duration of warm periods often restore community diversity, with algae (Chlorophyceae, Chrysophyceae, and Cryptophyceae) reemerging during transitional seasons. Additionally, seasonal overturns in autumn and spring enhance nutrient circulation, limiting the persistence of blooms compared to tropical systems [12,37,38].

Reservoirs in arid and semi-arid regions, such as northeastern Brazil, face unique challenges due to water scarcity and hydrological variability. Prolonged droughts increase nutrient concentrations due to reduced water renewal, intensifying eutrophication processes. This phenomenon sometimes occurs in the Brazilian Cerrado, where there is no rain for several months every year. Conversely, extreme rainfall contributes to nutrient loading from surrounding watersheds, often triggering short-lived but intense algal blooms [45,53].

Morphometry also plays a crucial role in the dynamics of phytoplankton. Deep reservoirs in mountainous regions, such as those in China, exhibit stronger thermal stratification and greater hypolimnetic anoxia, creating favourable conditions for cyanobacterial blooms. Like many in Brazil, shallow reservoirs exhibit more pronounced interactions between the water column and sediments, resulting in faster nutrient cycling and less predictable dynamics of phytoplankton [9,52]. These findings underline the importance of tailoring management strategies for regional and site-specific conditions.

4.5. Trophic State of the Water Body

It was noted that 93% of the samples from the TSI were classified as ultraoligotrophic, indicating low productivity and nutrient concentrations that do not significantly impact water quality. Based on the variables suggested in [32], most samples were classified as mesotrophic and oligotrophic in terms of total phosphorus and chlorophyll levels. Mesotrophic water bodies exhibit moderate productivity and may experience fluctuations in water quality. However, they remain within the permitted limitations set by legislation. Oligotrophic bodies exhibit poor productivity and do not significantly alter water quality due to their limited nutrient availability. The points were classified as eutrophic only in August and September 2015, as stated in reference [32]. The P03 point was certified as eutrophic in May 2015. No elevated phosphorus levels, indicative of eutrophic conditions, were recorded in the subsequent months. Therefore, based on these indicators, it can be inferred that the reservoir has acceptable productivity and nutrient concentrations. Most of the samples and indicators suggest that the risk of eutrophication is low, indicating a minimal chance that water use will be negatively affected by the harmful effects of organic enrichment.

Variations in chlorophyll-a concentrations and cyanobacteria densities over hydrological cycles revealed the seasonal dynamics of phytoplankton. Higher chlorophyll-a levels and TSI values, indicating a shift to mesotrophic conditions, suggest that the lower water flow and longer hydraulic retention times during the dry season created favourable conditions for cyanobacterial growth [38]. On the other hand, the rainy season saw higher turbidity and nutrient input from runoff, which temporarily enhanced the growth of other phytoplankton groups, including algae (Chlorophyceae, Chrysophyceae, and Cryptophyceae), before cyanobacteria took centre stage [53].

The interaction between phytoplankton growth properties and the Trophic State Index (TSI) revealed the adaptive strategies of cyanobacteria that enable them to persist across diverse trophic states. Due to their nitrogen fixation and nutrient storage capabilities, cyanobacteria have demonstrated remarkable resilience and adaptability, maintaining dominance even under extremely oligotrophic conditions. This reaction system emphasises the need to consider the ecological features of phytoplankton while interpreting TSI values [3,5].

5. Conclusions

Employing water quality analysis in the João Leite Reservoir within the Brazilian Cerrado, this study provides insight into the elements regulating phytoplankton, particularly cyanobacteria, in tropical water environments. This work reveals the interactions among physical, chemical, and biological components, yielding multiple conclusions for reservoir management.

The study found that variations in water quality and phytoplankton, linked to seasonal changes, had a greater effect than variations in reservoir location over time. Long-term observation is required to understand the trends of these systems.

The reservoir’s trophic state assessment showed a conflicting picture. The Trophic State Index (TSI) categorised the reservoir as ultraoligotrophic or low productivity. Still, examining chlorophyll-a and total phosphorus separately suggested oligotrophic to mesotrophic conditions at times, with some phosphorus readings indicating eutrophic conditions. This suggests a system with low overall output but promises of enrichment.

The cyanobacteria were consistently present and dominant throughout the study, even when nutrient levels (phosphorus and nitrogen) were low. This contrasts with expectations that low nutrients might limit cyanobacteria growth.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) revealed a correlation between water temperature and cyanobacteria density. This aligns with the knowledge that many cyanobacteria types thrive in warmer water. However, Pearson correlation and Canonical Correspondence Analysis (CCA) showed a weak or non-significant statistical connection between most measured chemicals, including nutrients, and cyanobacteria numbers.

Thus, the study suggests that cyanobacteria dominance, rather than nutrient levels, can be explained by the combination of high-water temperatures and slow water replacement (hydraulic retention time exceeding 180 days). For cyanobacteria that can regulate their position in the water, stable, warm, slow-moving water helps them succeed even in low nutrient levels.

The research supports the use of tools like probes with fluorometers to monitor chlorophyll-a and phycocyanin and track changes in phytoplankton over time. These methods help understand responses to environmental shifts.

This research highlights the influence of temperature and water dynamics on phytoplankton in this tropical reservoir. It demonstrates that cyanobacteria can establish dominance even in environments with low nutrient concentrations, possibly contingent upon specific physical conditions. These findings have implications for water management in the Cerrado and similar regions, suggesting that plans must address both physical factors and nutrient inputs, particularly as climate change may alter temperature and water patterns.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.S., R.E.B. and K.T.M.F.; Methodology, K.A.d.S.; Software, K.A.d.S.; Formal analysis, A.A.S., R.E.B. and K.T.M.F.; Investigation, A.A.S.; Writing—original draft, A.A.S.; Writing—review & editing, K.A.d.S., G.d.C.d.R., R.E.B. and K.T.M.F.; Supervision, R.E.B. and K.T.M.F.; Funding acquisition, R.E.B. and K.T.M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by FINEP (Financiadora de Estudos e Projetos) through research funding. Aline Arvelos Salgado; Kamila Almeida e Guilherme Reisreceived a doctoral scholarship from CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior). Klebber Formiga received a research fellowship from CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rolim, S.B.A.; Lobo, F.L.; Rasera, M.F.F.L.; Rodrigues, T.W.P.; Russell, M.J.; Su, L.; Novo, E.M.L.M. Remote sensing for mapping algal blooms in freshwater lakes: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 19602–19616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X.; Yang, S. A risk assessment method for remote sensing of cyanobacterial blooms in inland waters. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 740, 140012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paerl, H.W.; Otten, T.G. Harmful Cyanobacterial Blooms: Causes, Consequences, and Control. Microb. Ecol. 2013, 65, 995–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, C.C.; Ibelings, B.W.; Hoffmann, E.P.; Hamilton, D.P.; Brookes, J.D. Eco-physiological adaptations that favour freshwater cyanobacteria in a changing climate. Water Res. 2012, 46, 1394–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lins, R.P.M.; Barbosa, L.G.; Minillo, A.; de Ceballos, B.S.O. Cyanobacteria in a eutrophicated reservoir in a semi-arid region in Brazil: Dominance and microcystin events of blooms. Braz. J. Bot. 2016, 39, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittencourt-Oliveira, M.C.; Dias, S.N.; Moura, A.N.; Cordeiro-Araújo, M.K.; Dantas, E.W. Seasonal dynamics of cyanobacteria in a eutrophic reservoir (Arcoverde) in a semi-arid region of Brazil. Braz. J. Biol. 2012, 72, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- SANEAGO. Projeto Básico Ambiental da Barragem e do Reservatório de Regularização e Acumulação do Ribeirão João Leite em Goiânia, Goiás—Brasil; Relatório Técnico; Saneamento de Goiás S.A.: Goiânia, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, R.D.; Barbosa, C.C.F.; Novo, E.M.L.M. Assessment of in vivo fluorescence method for chlorophyll-a estimation in optically complex waters (Curuai floodplain, Pará—Brazil). Acta Limnol. Bras. 2012, 24, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, Y.; Park, S.S.; Kim, K.; Byeon, M.; Stow, C.A. Probabilistic prediction of cyanobacteria abundance in a Korean reservoir using a Bayesian Poisson Model. Water Resour. Res. 2014, 50, 7837–7853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowe, M.A.D.; Mitrovic, S.M.; Lim, R.P.; Furey, A.; Yeo, D.C.J. Tropical cyanobacterial blooms: A review of prevalence, problem taxa, toxins and influencing environmental factors. J. Limnol. 2015, 74, 205–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, E.J.S. Cianobactérias Planctônicas do Reservatório do Ribeirão João Leite (Goiás) Durante a Fase de Enchimento: Florística e Floração. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Goiânia, Brazil, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil, J.M.; Davis, T.W.; Burford, M.A.; Gobler, C.J. The rise of harmful cyanobacteria blooms: The potential roles of eutrophication and climate change. Harmful Algae 2012, 14, 313–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burford, M.A.; Johnson, S.A.; Cook, A.J.; Packer, T.V.; Townsley, E.R. Correlations between watershed and reservoir characteristics, and algal blooms in subtropical reservoirs. Water Res. 2007, 41, 4105–4114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, C.; Lin, Q.; Xiao, W.; Huang, B.; Lu, W.; Chen, J. Modeling of algal blooms: Advances, applications, and prospects. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 255, 107250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, R.; Sabahi, M.S.; Karbassi, A.R.; Baghvand, A.; Zadeh, H.T. Multivariate statistical analysis of surface water quality based on correlations and variations in the data set. Desalination 2010, 270, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, F.H.P.C.; Capela e Ara, A.L.S.; Moreira, C.H.P.; Lira, O.O.; Padilha, M.R.F.; Shinohara, N.K.S. Seasonal changes of water quality in a tropical shallow and eutrophic reservoir in the metropolitan region of Recife (Pernambuco-Brazil). An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2014, 86, 1863–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, T.W.; Berry, D.L.; Boyer, G.L.; Gobler, C.J. The effects of temperature and nutrients on the growth and dynamics of toxic and non-toxic strains of Microcystis during cyanobacteria blooms. Harmful Algae 2009, 8, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, L.V.; Formiga, K.T.M.; Costa, V.A.F. Comparison of methods for filling daily and monthly rainfall missing data: Statistical models or imputation of satellite retrievals? Water 2022, 14, 3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, L.V.; Formiga, K.T.M.; Costa, V.A.F. Analysis of the IMERG-GPM precipitation product analysis in Brazilian midwestern basins considering different time and spatial scales. Water 2022, 14, 2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, E.W.; Bridgewater, L.; American Public Health Association (Eds.) Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- CETESB. Guia Nacional de Coleta e Preservação de Amostra. Agua, Sedimento, Comunidade Aquáticas e Efluentes Liquidos; Companhia Estadual de Tecnologia de Saneamento Ambiental do Estado de São Paulo: São Paulo, Brazil, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Utermöhl, H. Zur vervollkommnung der quantitativen phytoplankton-methodik: Mit 1 Tabelle und 15 abbildungen im Text und auf 1 Tafel. Int. Ver. Theor. Angew. Limnol. Mitteilungen 1958, 9, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicudo, C.E.M.; Menezes, M. Gêneros de Algas de Águas Continentais do Brasil: Chave para Identificação e Descrições; RiMa Editora: São Carlos, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tucci, A.; Sant’Anna, C.L.; Azevedo, M.T.P.; Melcher, S.S.; Werner, V.R.; Malone, C.F.S.; Rosini, E.F.; Gama, W.A.; Hentschke, G.S.; Osti, J.A.S.; et al. Atlas de Cianobactérias e Microalgas de Águas Continentais Brasileiras; Instituto de Botânica: São Paulo, Brazil, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Komárek, J.; Anagnostidis, K. Cyanoprokaryota, 1: Chroococcales. In Süßwasserflora von Mitteleuropa; Ettl, H., Gärtner, G., Heynig, H., Mollenhauer, D., Eds.; Gustav Fischer: Stuttgart, Germany, 1999; Volume 19, pp. 1–548. [Google Scholar]

- Komárek, J.; Anagnostidis, K. Cyanoprokaryota, 2: Oscillatoriales. In Süßwasserflora von Mitteleuropa; Büdel, B., Krienitz, L., Gärtner, G., Schagerl, M., Eds.; Elsevier Spektrum Akademischer Verlag: München, Germany, 2005; Volume 19, pp. 1–759. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, F.A.D.; Pereira, T.S.R.; Soares, A.K.; Formiga, K.T.M. Using hydrodynamic model for flow calculation from level measurements. Rev. Bras. Recur. Hídricos 2016, 21, 707–718. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, F.; Liu, Y.; Guo, H. Application of multivariate statistical methods to water quality assessment of the watercourses in northwestern New Territories, Hong Kong. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2007, 132, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, E.P.; Filho, N.R.A.; Pereira, J.; Formiga, K.T.M. Temporal variation and risk assessment of heavy metals and nutrients from water and sediment in a stormwater pond, Brazil. Water Supply 2023, 23, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, R.E. A trophic state index for lakes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1977, 22, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamparelli, M.C. Graus de Trofia em Corpos D’água do Estado de São Paulo: Avaliação dos Métodos de Monitoramento. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. The OECD Cooperative Programme on Eutrophication; Canadian Contribution; Janus, L.L., Vollenweider, R.A., Eds.; Environment Canada, National Water Research Institute, Inland Waters Directorate: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil. Conselho Nacional do Meio Ambiente (CONAMA). Resolução CONAMA N° 357, de 17 de Março de 2005. Dispõe Sobre a Classificação dos Corpos de Água e Diretrizes Ambientais para o seu Enquadramento, bem como Estabelece as Condições e Padrões de Lançamento de Efluentes. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF, 18 March 2005. Available online: https://conama.mma.gov.br/?option=com_sisconama&task=arquivo.download&id=450 (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Portaria GM/MS Nº 888, de 4 de Maio de 2021. Altera o Anexo XX da Portaria de Consolidação GM/MS nº 5, de 28 de Setembro de 2017, para Dispor Sobre os Procedimentos de Controle e de Vigilância da Qualidade da Água para Consumo Humano e seu Padrão de Potabilidade. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF, 7 May 2021. Available online: https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/portaria-gm/ms-n-888-de-4-de-maio-de-2021-318461562 (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Fernandes, V.O.; Cavati, B.; Oliveira, L.B.; Souza, B.D. Ecologia de cianobactérias: Fatores promotores e consequências das florações. Oecol. Bras. 2009, 13, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzeli, G.M.; Cunha-Santino, M.B. Análise e diagnóstico da qualidade da água e estado trófico do reservatório de Barra Bonita, SP. Ambi-Água 2013, 8, 186–205. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.; Wang, L.; Yang, Y.; Huang, T. A case study of thermal and chemical stratification in a drinking water reservoir. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 848, 157697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwell, J.D.; Doubek, J.P.; Adrian, R.; Anneville, O.; Carey, C.C.; Carvalho, L.; Wilson, H.L. Storm impacts on phytoplankton community dynamics in lakes. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 2756–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Han, R.; Chen, D.; Ma, H.; Han, X.; Shi, C. Algal Decomposition Accelerates Denitrification as Evidenced by the High-Resolution Distribution of Nitrogen Fractions in the Sediment-Water Interface of Eutrophic Lakes. Water 2024, 16, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellucci, M.; Ofiţeru, I.D.; Graham, D.W.; Head, I.M.; Curtis, T.P. Low-dissolved-oxygen nitrifying systems exploit ammonia-oxidizing bacteria with unusually high yields. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 7787–7796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Yang, B.; Huang, T.; Si, F.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, L. Hypolimnetic anoxia and sediment oxygen demand during stratification in a drinking water reservoir. J. Soils Sediments 2021, 21, 3380–3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gao, X.; Sun, B.; Liu, X. Oxygen evolution and its drivers in a stratified reservoir: A supply-side perspective for informing hypoxia alleviation strategies. Water Res. 2024, 257, 121694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Gan, R.; Li, Y.; Chen, W.; Ma, D.; Chen, J.; Luo, H. Effects of anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM) driven by iron and manganese oxides on methane emissions in constructed wetlands and underlying mechanisms. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 495, 153539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, L.J.; Fakhraee, M.; Smith, A.J.B.; Swanner, E.D.; Peacock, C.L.; Lyons, T.W. Manganese oxides, Earth surface oxygenation, and the rise of oxygenic photosynthesis. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2023, 239, 104368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adloff, C.T.; Bem, C.C.; Reichert, G.; Azevedo, J.C.R. Análise da comunidade fitoplanctônica com ênfase em cianobactérias em quatro reservatórios em sistema de cascata do rio Iguaçu, Paraná, Brasil. Rev. Bras. Recur. Hídricos 2018, 23, e6. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, D.G.F.; Calijuri, M.C. Variação sazonal dos grupos funcionais fitoplanctônicos em braços de um reservatório tropical de usos múltiplos no estado de São Paulo (Brasil). Acta Bot. Bras. 2011, 25, 822–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellém, F.; Nunes, S.; Morais, M. Toxicidade a Cianobactérias: Impacte Potencial na Saúde Pública em populações de Portugal e Brasil. In Proceedings of the XIV Encontro da Rede Luso-Brasileira de Estudos Ambientais, Recife, Brazil, 12–16 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Malheiros, C.H.; Hardoim, E.L.; Lima, Z.M.; Amorim, R.S.S. Qualidade da água de uma represa localizada em área agrícola (Campo Verde, MT, Brasil). Ambi-Água 2012, 7, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paerl, H.W.; Huisman, J. Blooms like it hot. Science 2008, 320, 57–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tundisi, J.G.; Tundisi, T.M. Limnologia; Oficina de Textos: São Paulo, Brazil, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.L.; Wang, L.; Chang, A.; Fei, S.D.; Fang, J.F.; Liang, D.; Yan, C.J. Interannual monitoring of water environment and spatiotemporal dynamics of phytoplankton community and blooming risk in a tropical water source reservoir, China. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2024, 22, 6017–6043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueredo, C.C.; Pinto-Coelho, R.M.; Lopes, A.M.M.B.; Lima, P.H.O.; Gücker, B.; Giani, A. From Intermittent to Persistent Cyanobacterial Blooms, Identifying the Main Drivers in an Urban Tropical Reservoir. J. Limnol. 2016, 75, 540–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardim, B.F.M. Variação dos Parâmetros Físicos e Químicos das Águas Superficiais da Bacia do Rio das Velhas-MG e sua Associação com as Florações de Cianobactérias. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, L.E.; Graham, J.M.; Wilcox, L.W.; Cook, M.E. Algae, 3rd ed.; LJLM Press: Dubuque, IA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Shi, K. Research trends in the remote sensing of phytoplankton blooms: Results from bibliometrics. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).