Abstract

The accurate real-time forecasting and impact factor identification of air pollutant levels are critical for effective pollution control and management. In this study, we implemented three machine learning algorithms, namely, Random Forest (RF), eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and Fully Connected Neural Network (FCNN), to predict PM2.5 and O3 concentrations in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region from 2019 to 2023. XGBoost outperformed the other algorithms and was further utilized to predict PM2.5 and O3 concentrations and identify their controlling factors. The models could efficiently capture the spatial and temporal variations in the pollutants in the study area, and it was found that both anthropogenic sources and weather conditions can have significant impacts on air pollutant levels. PM10 and CO were significantly correlated to PM2.5 levels, which could be attributed to their similar emission sources and dispersion characteristics in air. O3 concentrations were greatly influenced by temperature and NO2 due to their significant impacts on O3 generation. This study demonstrates that XGBoost-based models are cost-effective tools for predicting PM2.5 and O3 levels and identifying their controlling factors. These findings provide valuable insights for formulating effective air pollution prevention policies.

1. Introduction

With China’s rapid industrialization and urbanization, air pollution has escalated, posing significant threats to human health and the ecological environment. PM2.5 and O3 are globally recognized as critical outdoor air pollutants due to their detrimental health impacts [1]. In recent years, severe PM2.5 pollution events and their corresponding health risks sparked widespread public concern in China [2]. During the 13th Five-Year Plan (2016–2020), China implemented robust measures to reduce atmospheric PM2.5 levels, achieving a significant decline in average annual concentrations from 50 to 30 μg/m3 across 338 cities [3]. Despite these effective control efforts, regions such as central and northern China remain priorities for ongoing air quality improvement initiatives [4]. O3, formed through photochemical reactions of nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in the atmosphere, has garnered increasing attention from both the public and researchers. Exposure to high O3 levels can seriously affect the respiratory and heart health of individuals and lead to negative outcomes for the natural environment [5].

In recent years, China’s rapid industrialization and urbanization have driven remarkable economic growth but have also intensified severe air pollution challenges. Among the various air pollutants, PM2.5 and O3 have emerged as key concerns, attracting significant attention from both the scientific community and the public [6].

PM2.5 originates from a complex and diverse range of sources. Industrial activities, including thermal power generation, iron and steel smelting, and cement manufacturing, are major contributors, emitting significant amounts of particulate matter containing heavy metals, sulfates, and nitrates [7]. In the transportation domain, fine particles from motor vehicle exhaust and road dust play crucial roles [8]. Additionally, coal combustion in residential settings, cooking fumes, and agricultural straw burning further exacerbate PM2.5 pollution levels [9].

Unlike directly emitted pollutants, O3 formation is intricately tied to precursor compounds such as nitrogen oxides (NOx) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) [10]. These precursors, found in industrial emissions and vehicle exhausts, undergo complex photochemical reactions under sunlight and high-temperature conditions to produce O3 [11]. Notably, during summer months with elevated temperatures, intensified photochemical activity often results in significantly higher O3 concentrations [12].

Due to its minute particle size, PM2.5 can easily penetrate the respiratory tract, reaching the lungs and even entering the bloodstream via gas exchange [13]. This exposure can trigger numerous health issues, including respiratory inflammation and cardiovascular diseases, with prolonged exposure significantly increasing the risk of serious conditions such as lung cancer [14]. According to the World Health Organization, millions of people worldwide suffer premature deaths annually due to elevated PM2.5 concentrations. Similarly, O3 poses substantial health risks. High O3 levels irritate the respiratory mucosa, leading to symptoms such as coughing, wheezing, and breathing difficulties [15]. O3 exposure can also damage lung cells and weaken the immune system, posing a particularly severe threat to vulnerable populations, including children and the elderly [16].

Despite China’s significant efforts in air pollution prevention and control, which have led to notable reductions in PM2.5 concentrations in key regions, challenges persist. In industrially concentrated and densely populated areas, PM2.5 levels frequently exceed standards, and heavy pollution days continue to occur intermittently [17]. Concurrently, O3 pollution has worsened, with an increasing number of days exceeding safe levels. O3 has emerged as the primary pollutant impacting summer air quality, posing new challenges for air pollution prevention and control [18].

A thorough investigation of PM2.5 and O3 pollution is crucial for developing targeted prevention and control strategies and protecting public health. Comprehensive understanding of their sources, health impacts, and current trends is vital for designing effective mitigation measures.

To devise effective pollutant management and control strategies, the accurate forecasting of the spatial and temporal distribution of pollutants under varying natural and anthropogenic conditions is essential. Chemistry transport models (CTMs) simulate the physical and chemical processes driving the formation and dispersion of atmospheric contaminants [19]. However, the accuracy of CTM outputs heavily relies on the quality of input data, such as emission inventories, and model parameters. Additionally, their application is often constrained by the high computational costs associated with large-scale numerical simulations. In contrast to CTMs, statistical techniques adopt a data-driven approach, predicting pollutant concentrations by uncovering patterns, trends, and relationships within observational data [20]. Traditional multivariate methods, such as correlation matrices and Principal Component Analysis (PCA), are widely employed to assess the degree of correlation among variables and identify potential sources of air pollutants [21,22]. Land-use regression models and Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) have been employed to evaluate spatial variations and identify the causes of outdoor air pollution [23,24]. However, these methods struggle to capture nonlinear behaviors and complex interactions between air pollutants and covariates, particularly in large-scale spatiotemporal studies. Additionally, they face challenges in accurately predicting pollutant concentrations using historical data.

Accurate prediction of PM2.5 concentrations is critical for effective air quality monitoring and mitigating associated health risks. Machine learning approaches have gained prominence in modeling the complex spatial and temporal variability of PM2.5, owing to their ability to capture nonlinear relationships and integrate diverse data sources. Fully Connected Neural Networks (FCNNs), often combined with deep learning architectures like Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, have demonstrated strong potential for fine-grained urban air quality forecasting. For example, Han et al. (2021) developed the Deep-AIR framework, which integrates Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and LSTM to effectively model spatial interactions and temporal dependencies, achieving high accuracy in predicting PM2.5 concentrations in metropolitan areas [25].

Random Forest (RF) models are widely favored for their robustness and interpretability. Hu et al. (2017) employed a Random Forest algorithm, integrating aerosol optical depth (AOD), meteorological data, and land-use variables, to estimate daily PM2.5 concentrations across the conterminous United States [26]. Their model achieved strong predictive performance, with an R2 of 0.80 in cross-validation, demonstrating reliable spatial estimation of PM2.5 levels. Gradient-boosting methods, such as eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), have gained significant attention for their efficiency and high accuracy in handling complex, multi-source datasets, particularly in environmental prediction tasks. Zhang and Batterman (2013) [27] utilized XGBoost, incorporating a diverse set of spatiotemporal features, including meteorological variables (e.g., wind speed, temperature, and precipitation) and satellite-derived data (e.g., aerosol optical depth). Their results demonstrated that XGBoost significantly outperformed traditional regression models in predicting PM2.5 concentrations, achieving lower root mean square error (RMSE) and a higher coefficient of determination (R2). Furthermore, their study underscored the importance of feature selection in enhancing model performance: by identifying and prioritizing the most influential spatiotemporal features, the model’s interpretability and generalization capabilities were markedly improved, offering valuable insights for advancing air quality prediction frameworks [28].

In recent years, various machine learning algorithms, including CNNs [29], RF [30], XGBoost [31], FCNNs [32], and Extremely Randomized Trees (ERTs) [33], have been applied to forecast ground-level air pollutant concentrations. These methods have demonstrated superior performance compared with traditional statistical modeling techniques. Machine learning approaches offer robust nonlinear mapping capabilities for large, complex datasets, leveraging flexible model structures and efficient algorithms to capture intricate interactions effectively [34]. Notably, RF and XGBoost models have proven highly effective in forecasting SO2, PM2.5, and O3 concentrations, as demonstrated by numerous studies reporting promising results [35]. For instance, Vu et al. utilized an RF technique to quantify trends in PM2.5 air quality driven by anthropogenic emissions in Beijing from 2013 to 2017, achieving results consistent with those from Chemistry Transport Models (CTMs) [36]. Similarly, FCNNs have been successfully applied to predict PM2.5 concentrations [37]. The performance differences among FCNNs, XGBoost, and RF arise from their distinct architectural characteristics and adaptability to data, influencing several key aspects. FCNNs, with their deep hierarchical structures, are prone to overfitting, particularly when training data is limited or noisy, as they tend to memorize complex patterns, including noise. In contrast, XGBoost and RF, as ensemble methods, reduce this risk through built-in regularization (e.g., tree depth constraints in XGBoost) and bagging/boosting techniques that average predictions across multiple learners, improving generalization to unseen data. Regarding data compatibility, XGBoost and RF are well-suited for tabular data, effectively handling mixed feature types (e.g., continuous meteorological variables and categorical emission source data) with minimal preprocessing. Conversely, FCNNs often require extensive feature engineering, such as normalization or dimensionality reduction, and struggle to intuitively capture spatial or categorical relationships, as they process inputs as flattened numerical vectors. Regarding sensitivity to design and tuning, FCNNs are highly sensitive to network architecture (e.g., number of layers and neurons) and hyperparameters (e.g., learning rate and regularization strength), necessitating careful tuning to avoid underfitting or instability. XGBoost and RF, however, are more robust to parameter variations, delivering consistent performance across a wide range of settings, making them more practical for implementation. Computationally, FCNNs demand significant training time and resources (e.g., GPU acceleration) due to iterative backpropagation and large parameter spaces. In contrast, XGBoost and RF operate efficiently on standard hardware, with faster convergence and lower memory requirements, making them ideal for the large-scale environmental datasets typical in air quality research. These three models were chosen for this study to balance predictive accuracy and computational feasibility. While FCNNs excel at capturing nonlinear spatiotemporal patterns, XGBoost and RF offer reliable performance with shorter training times, a crucial factor for real-world air quality forecasting and policy support applications [38,39].

This study developed and validated a suite of machine learning models—RF, XGBoost, and FCNNs—to predict PM2.5 and O3 concentrations in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region. Model performance was thoroughly assessed using multiple error metrics (RMSE, MAE, and R2) to determine the most effective algorithm, which was subsequently applied to forecast pollutant levels and identify key influencing factors for individual cities in the region. This study pursues two primary objectives: first, to improve the accuracy and reliability of air pollutant predictions by leveraging advanced algorithms, including deep learning and ensemble methods, which adeptly capture complex nonlinear relationships in environmental data; second, to identify the primary drivers of PM2.5 and O3 variations, such as meteorological conditions, emission sources, and topographical features. By achieving these aims, this research provides valuable insights into the practical application of data-driven models in air quality research. The findings are poised to inform evidence-based air pollution control policies, support targeted strategies for mitigating PM2.5 and O3 pollution, and establish a scientific foundation for protecting public health and advancing sustainable environmental management in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Dataset

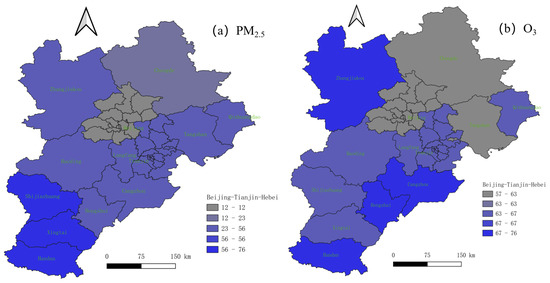

The Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region (Figure 1) is located between 36°5′∼42°40′ N latitude and 113°27′~119°50′ E longitude, including Beijing, Tianjin, and 11 cities in Hebei Province (Baoding, Tangshan, Langfang, Cangzhou, Qinhuangdao, Shijiazhuang, Zhangjiakou, Chengde, Handan, Xingtai, and Hengshui). As seen in Figure 1, Handan has a notably high PM2.5 concentration, with the green bar for this city standing out significantly compared with others. Other cities like Xingtai, Shijiazhuang, and Hengshui also exhibit relatively high PM2.5 concentrations. In contrast, Chengde has a comparatively low PM2.5 concentration, with the green bar for this city being shorter in height than most others. Zhangjiakou also shows a relatively low PM2.5 concentration. Chengde stands out for its relatively high O3 concentration, with the light-blue bar representing this value being quite prominent. Additionally, cities like Qinhuangdao and Tangshan also show relatively high O3 concentrations. On the other hand, Handan has a low O3 concentration, with its light-blue bar being notably short. Xingtai and Shijiazhuang also fall within the lower range of O3 concentrations. In 2023, the total Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region reached CNY 10.44 trillion, nearly doubling from CNY 5.53 trillion in 2013, accounting for 8.3% of the national GDP. The Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region and its surrounding areas were once the regions with the highest emission amounts and intensity (emissions per unit area) of air pollutants in China. Although cities in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region and surrounding areas account for less than 3% of the country’s land area, they emitted more than 15% of the country’s primary PM2.5, 10% of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides, and 8% of VOCs (volatile organic compounds) [40]. The emission intensity was 2 to 5 times the national average.

Figure 1.

Spatial distribution of average hourly concentrations of PM2.5 (a) and O3 (b) in Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region, China (2019–2023).

Meteorological variables such as temperature (T), surface pressure (P), relative humidity (RH), dew/frost point temperature (TDEW), wind speed (WS), wind direction (WD), precipitation (PREP), and all-sky surface shortwave downward irradiance (IRRA) are key factors in predicting PM2.5 and O3 concentrations because they directly and indirectly affect pollutant formation, dispersion, and removal.

Temperature influences atmospheric chemical reaction rates, accelerating photochemical reactions that increase O3 production, and affects the emission of precursors for PM2.5 formation [41]. Surface pressure impacts vertical mixing and atmospheric stability, thereby affecting pollutant dispersion [42]. Relative humidity and dew/frost point affect aerosol growth and secondary aerosol formation, influencing PM2.5 levels [43]. Wind speed and direction control pollutant transport, affecting local concentrations [44]. Precipitation removes pollutants via wet deposition, reducing PM2.5 [45]. Solar irradiance drives photochemical reactions essential for O3 formation. Incorporating these meteorological factors improves the accuracy of PM2.5 and O3 prediction models.

The data used in this study are entirely sourced from the nationwide national air monitoring stations shared by the China National Environmental Monitoring Center. All data have been reviewed, approved, and released by authoritative national agencies, ensuring their authenticity and reliability. The dataset spans the period from 2019 to 2023 and includes six air pollutants and eight meteorological factors at an hourly resolution for the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region. The concentrations of atmospheric pollutants, including PM2.5, PM10, CO, NO2, SO2, and O3, were obtained from the National Environmental Monitoring Center of China (https://air.cnemc.cn:18007, accessed on 1 February 2024), while the meteorological information was obtained from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA, https://power.larc.nasa.gov/data-access-viewer, accessed on 1 February 2024) and includes temperature (T), surface pressure (P), relative humidity (RH), dew/frost point (TDEW), wind speed (WS), wind direction (WD), precipitation (PREP), and all-sky surface shortwave downward irradiance (IRRA). Table 1 provides the annotations, brief descriptions, and basic statistical information of the weather parameters. During the data preprocessing phase, missing values in the original dataset were filled using data from the previous time slot (i.e., using the forward-filling or last-observation-carried-forward method). Higher temperatures (T2M) accelerate O3 formation by increasing the rates of NO2 photolysis and VOC oxidation. Inversion layers (cold air trapped beneath warm air) at low T2MDEW can suppress vertical mixing, leading to PM2.5 accumulation [1]. Solar radiation (ALLSKY_SFC_SW_DWN) is critical for O3 formation, as it drives NO2 photolysis and initiates VOC oxidation cycles. For example, O3 peaks in summer due to intense sunlight and high temperatures. Relative humidity (RH2M) affects aerosol hygroscopic growth: high humidity promotes water uptake by particles (e.g., sulfate or nitrate), increasing PM2.5 mass concentrations. Dew point (T2MDEW) indicates the likelihood of fog or dew, which can enhance aqueous-phase reactions (e.g., SO2 oxidation) and reduce visibility. Regarding surface pressure (PS), high-pressure systems often bring clear skies and light winds, favoring O3 formation but hindering PM2.5 dispersion. Wind (WS10M, WD10M) determines pollutant transport: strong winds (e.g., ≥5 m/s) enhance dispersion, while calm winds (≤2 m/s) trap pollutants near sources. Precipitation (PRECTOTCORR) is a primary removal mechanism for PM2.5. Moderate-to-heavy rain (≥10 mm/day) efficiently scavenges particles, while light rain may have limited effect. SO2 is a key precursor for sulfate aerosols. Its oxidation pathways include gas-phase reactions with hydroxyl radicals (OH) and aqueous-phase reactions in cloud droplets. Under sunlight, NO2 photolyzes to NO and atomic oxygen (O), which reacts with O2 to form O3. CO is a byproduct of incomplete combustion. While it does not directly form PM2.5 or O3, it consumes OH radicals (CO + OH→CO2 + H), indirectly affecting O3 production rates [46].

Table 1.

Basic statistical information about meteorological factors.

2.2. Models Based on Machine Learning Algorithms

Modeling Framework and Variable Selection Principles: Theoretical and Empirical Insights for Lagged Variables in Time-Series Forecasting.

2.2.1. Fundamental Principles of the Modeling Framework and Variable Selection

Model I: Instantaneous Prediction Based on Contemporaneous Pollutant Concentrations

The core logic of Model I is grounded in the synergistic generation and mutual influences between pollutants within the same temporal framework. As a key atmospheric component, PM2.5 exhibits intricate relationships with co-occurring pollutants. For instance, PM10 and PM2.5 are inherently linked through shared emission sources (e.g., dust storms and coal combustion), with PM10 serving as a primary component and precursor to PM2.5, thereby demonstrating a robust positive correlation [47]. O3 acts as both a reactant and indicator in secondary aerosol formation. Photochemical reactions involving O3 drive the conversion of SO2 and NO2 into sulfates and nitrates, establishing a nonlinear association where elevated O3 concentrations often precede PM2.5 surges, particularly under high humidity and low-wind conditions. SO2 and NO2 act as critical precursors for secondary PM2.5 formation [48], with their conversion efficiency to particulate matter heavily dependent on meteorological parameters—aqueous-phase reactions under humid conditions, for example, accelerate sulfate formation [49]. CO, as a tracer for combustion sources, correlates with PM2.5 emissions from traffic and industrial activities, providing complementary information on primary emission intensity [50]. This framework is tailored for short-term forecasting (0–12 h), harnessing real-time data to capture immediate pollution dynamics, such as abrupt emission peaks or rapid photochemical transformations.

Model II: Time-Series Prediction Incorporating Lagged Variables

Model II addresses the temporal lag in pollutant processes, where the previous day’s environmental conditions and contaminant levels influence current-day concentrations. Chemical transformation lag is a defining characteristic, as the conversion of SO2 and NO2 to secondary aerosols requires hours to days. For instance, nitrate formation via nighttime N2O5 hydrolysis may not manifest in PM2.5 until the following day [51]. Meteorological cumulative effects play a pivotal role. Stagnant conditions (e.g., low wind speed or temperature inversion) on day(t−1) can trap pollutants, leading to elevated PM2.5 on day t [52]. Emission inertia from industrial and transportation sectors ensures continuity in pollution sources, making day(t−1) emissions a critical baseline for day t predictions.

Key variables in Model II include lagged PM2.5 (t−1), which represents pollutant accumulation under stable atmospheric conditions, serving as an initial condition for current-day modeling, and lagged precursors (PM10, SO2, NO2, O3, and CO on day(t−1), which capture the potential for secondary aerosol formation and regional transport. For example, elevated NO2 on day(t−1) signals increased nitrate aerosol production on day t [53].

2.2.2. Necessity and Advantages of Lagged Variables in Model II

- (1)

- Capturing long-range transport and cumulative effects: Lagged variables are indispensable for modeling cross-regional pollution transport. For instance, dust plumes or industrial emissions from upwind regions may take 6–18 h to reach the monitoring site, with day (t−1) PM10 levels serving as a proxy for day t PM2.5 impacts [54].

- (2)

- Enhancing the prediction stability: By incorporating historical data, Model II mitigates the impact of real-time data anomalies (e.g., sensor malfunctions) and captures seasonal emission patterns (e.g., winter coal heating cycles), thereby improving forecast robustness.

2.2.3. Introduction to Model Design

Two machine learning models, Models I and II, were developed to predict PM2.5 and O3 concentrations in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region. Model I: This model employs three algorithms—RF, XGBoost, and FCNN—using contemporaneous pollutant datasets (e.g., SO2,t at time t) and meteorological conditions (e.g., temperature T_t) as input variables. The target outputs are pollutant concentrations at the same time (e.g., O3,t). Model I is designed to identify potential sources and key factors influencing PM2.5 and O3 concentrations. Model II: Utilizing only XGBoost, this model incorporates historical pollutant data (e.g., O3,t) and meteorological conditions at the predictive time (t + 1, i.e., one day after time t), such as temperature T_{t + 1}, as inputs. The target outputs are pollutant concentrations at the predictive time (e.g., O3{t + 1}). Model II enables forecasting of PM2.5 and O3 levels for the following day based on current pollution levels and forecasted weather conditions.

RF, XGBoost, and FCNNs are widely used machine learning algorithms. As a supervised learning algorithm for classification and regression tasks, RF constructs multiple decision trees using randomly selected subsets of data and features. The model enhances performance by aggregating the results of all trees. Based on gradient-boosted decision trees, XGBoost builds trees sequentially, with each tree trained on the residuals of its predecessor to improve predictive accuracy. As a fundamental neural network architecture, FCNN consists of multiple hidden layers with interconnected neurons. Each neuron in a layer is fully connected to all neurons in the preceding and following layers. Further details on these algorithms are provided in the Supporting Information. In this study, the GridSearchCV technique, as introduced by Wang et al. (2020) [55], was employed to optimize model configurations. This method involves two steps: grid search and k-fold cross-validation. Grid search identifies the optimal model parameters within a specified range based on the performance metrics from k-fold cross-validation. The dataset was split into training and testing sets in a 9:1 ratio using random sampling, and 10-fold cross-validation was conducted to build and assess model performance. The parameter set yielding the highest accuracy on the testing data was selected as the optimal configuration. Table S1 details the parameter settings for the models across the different machine learning algorithms.

2.3. Model Performance Evaluation

For evaluation of the model performance, multiple indicators were calculated using Equations (1)–(3) [56], namely, root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), and R2.

where n is the number of samples in the test set, y is the predicted value, y is the true value, and y the mean value.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Temporal and Spatial Distribution of PM2.5 and O3

Table 1 summarizes the basic statistical information of meteorological factors in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region, revealing distinct seasonal variations. The annual average temperature is 12.29 °C, with hot summers (25.71 °C) and cold winters (−2.59 °C), while spring (13.20 °C) and autumn (12.64 °C) remain relatively mild. Relative humidity averages 60.11% annually, peaking in summer (65.07%) and reaching its lowest in spring (49.96%), likely due to reduced precipitation in spring (0.041 mm/h) compared with a significant increase in summer (0.22 mm/h). Wind speed is highest in spring (4.23 m/s) and lowest in summer (3.07 m/s), with wind direction varying significantly across seasons but predominantly from the south. Additionally, all-sky surface shortwave downward irradiance peaks in summer (221.13 Wh/m2) and drops to its lowest in winter (110.46 Wh/m2), reflecting clear seasonal variations in daylight hours.

Table 2 presents the results of the correlation analysis between pollutants and meteorological factors, highlighting the significant influence of weather conditions on pollutant concentrations in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region. For example, temperature exhibits a negative correlation with PM2.5 levels, as colder weather often increases PM2.5 emissions from heating activities. Conversely, temperature is positively correlated with O3 concentrations, as higher temperatures enhance O3 production through photochemical reactions. Additionally, PM2.5 shows strong correlations with PM10, CO, and NO2, indicating that these pollutants likely originate from common sources, such as fuel combustion and industrial processes.

Table 2.

Pearson’s correlation matrix of atmospheric pollutants and meteorological factors in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region.

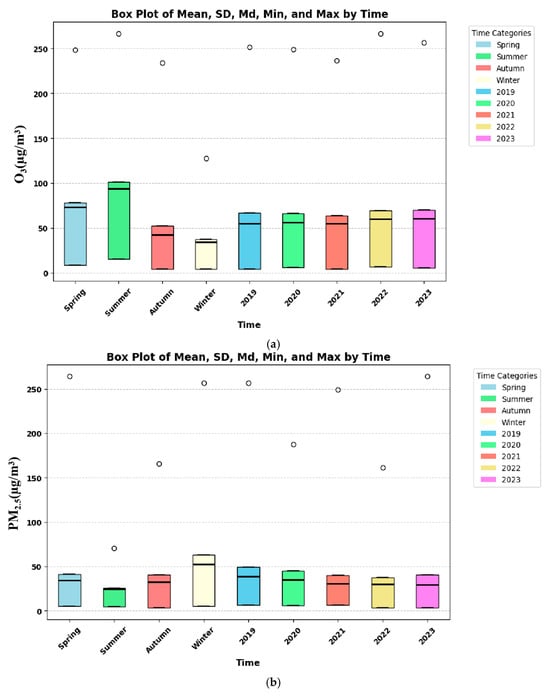

Figure 2 illustrates the descriptive statistics of hourly average PM2.5 and O3 concentrations in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region from 2019 to 2023. PM2.5 concentrations exhibited a slight downward trend over the study period, accompanied by pronounced seasonal variations. Situated in the northern part of the North China Plain, the region experiences a typical warm temperate semi-humid and semi-arid continental monsoon climate, characterized by cold, dry winters and hot, rainy summers. As shown in Figure 2a, the annual mean PM2.5 concentration was highest in 2019 (49.39 μg/m3), gradually declining to 44.71 μg/m3 in 2020, 40.02 μg/m3 in 2021, and 37.4 μg/m3 in 2022, before a slight increase to 40.5 μg/m3 in 2023. Winters consistently recorded the highest mean PM2.5 concentrations across all years, particularly in 2019 (79.75 μg/m3), 2020 (79.79 μg/m3), and 2021 (52.42 μg/m3), driven by stable meteorological conditions, increased anthropogenic emissions, higher residential burning, lower temperatures, and reduced surface solar radiation [56]. In contrast, summer exhibited the lowest PM2.5 concentrations, with the minimum recorded in summer 2023 (20.69 μg/m3). Spring and autumn generally displayed moderate concentration levels.

Figure 2.

Boxplots of PM2.5 (a) and O3 (b) concentrations in Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region, China (2019–2023).

Figure 2b shows that annual mean O3 concentrations in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region remained relatively stable from 2019 to 2023, with values of 66.86 μg/m3 in 2019, 65.9 μg/m3 in 2020, 63.45 μg/m3 in 2021, 69.19 μg/m3 in 2022, and 69.84 μg/m3 in 2023. Summer consistently exhibited the highest O3 concentrations across all years, while winter recorded the lowest. Meteorological factors, such as ambient temperature and surface solar radiation, play a critical role in O3 formation. Elevated O3 levels in summer are driven by enhanced photochemical reactions due to high temperatures and strong solar radiation [57], whereas cold temperatures and weak solar radiation in winter suppress O3 formation [58]. Spring and autumn generally showed moderate O3 concentrations, with spring levels typically exceeding those in autumn in most years.

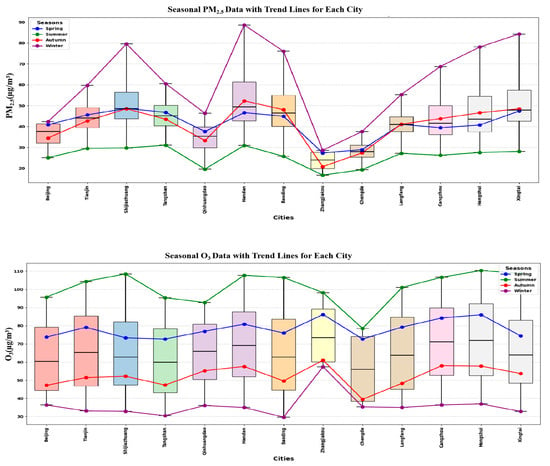

Figure 3 illustrates the PM2.5 and O3 concentration levels across various cities in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region. Notable spatial variations were observed in PM2.5 concentrations, while O3 levels showed relatively minor differences across cities. Among the cities, Handan, Xingtai, and Shijiazhuang exhibited higher PM2.5 concentrations, whereas Chengde and Zhangjiakou recorded the lowest. For O3, Shijiazhuang, Hengshui, and Xingtai displayed relatively elevated levels.

Figure 3.

PM2.5 and O3 concentrations for different cities in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region from 2019 to 2023.

3.2. PM2.5 and O3 Predictions Using Machine Learning Algorithms

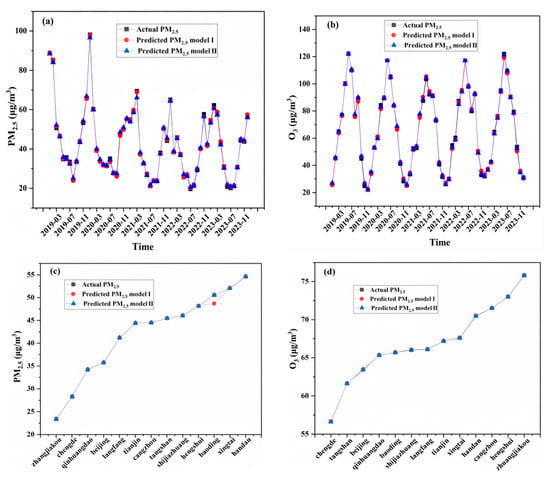

In this study, two models employing three machine learning algorithms—XGBoost, FCNN, and RF—were developed to predict PM2.5 and O3 concentrations. Figures S1 and S2 present scatter plots of predicted versus observed values for the training and testing datasets, including fit lines and error estimations. The results indicate that the models performed well for most observations, with all three algorithms yielding comparable and highly effective predictions for PM2.5 and O3. This underscores the potential of machine learning algorithms for applications such as identifying emission sources, detecting key influencing factors, and forecasting air pollution emergencies. Model performance was further assessed using statistical error metrics, summarized in Table 3 for both training and testing datasets. The models explained significant portions of the variance, with R2 values ranging from 0.830 to 0.996, demonstrating their robust ability to capture underlying patterns in the data. However, FCNN exhibited notably higher prediction errors, as indicated by root mean square error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE), compared with XGBoost and RF. Among the algorithms, XGBoost outperformed RF regarding R2, MAE, and RMSE, suggesting its superior predictive capability for PM2.5 and O3 concentrations in this study. Time-series plots of XGBoost-based model predictions alongside observed values are shown in Figure 4a,b, while mean concentrations for individual cities over the study period are depicted in Figure 4c,d. These results demonstrate that the models effectively captured both the temporal and spatial variations in pollutant concentrations.

Table 3.

Error analysis of PM2.5 and O3 predictions using three machine learning algorithms in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region.

Figure 4.

Concentrations of pollutants in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region: (a) monthly PM2.5 concentrations; (b) monthly O3 concentrations; (c) PM2.5 concentrations by city; (d) O3 concentrations by city.

XGBoost was employed to predict PM2.5 and O3 concentrations in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region using Model I and Model II. As presented in Table 4, both models generally produced reliable results across the investigated cities. For instance, Model I achieved R2 values for PM2.5 predictions on the testing dataset ranging from 0.914 (Langfang) to 0.976 (Shijiazhuang), and for O3 predictions from 0.886 (Zhangjiakou) to 0.947 (Beijing). In contrast, Model II exhibited lower R2 values overall, with PM2.5 predictions on the testing dataset ranging from 0.648 (Zhangjiakou) to 0.922 (Baoding) and O3 predictions from 0.834 (Qinhuangdao) to 0.901 (Tianjin). Figures S3 and S4 display scatter plots and regression results of predicted versus observed values for the cities with the highest and lowest forecasting accuracies for PM2.5 and O3 using Models I and II, respectively. Although prediction accuracies varied across cities, both models proved effective in forecasting pollutant concentrations, providing accurate estimations for most observations. The seasonal performance of Models I and II for PM2.5 and O3 predictions is illustrated in Figures S5–S8. The models demonstrated relatively stable performance for O3 predictions across seasons, while PM2.5 predictions showed some variability. Notably, the models tended to underestimate PM2.5 concentrations during severely polluted events in spring, possibly due to unique emission sources such as agricultural burning (e.g., crop straw and biomass), which are challenging to quantify due to their fragmented and unregulated nature. Incomplete or outdated emission inventories may contribute to these underestimations. To assess model robustness, the independent variables in the original dataset were doubled and increased by 10%. The results showed no significant changes in R2, RMSE, or MAE, indicating strong model robustness and generalizability.

Table 4.

Error analysis of PM2.5 and O3 predictions using XGBoost across cities in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region.

Table 5 compares the model fitting and validation results of this study with other relevant studies conducted in China, offering valuable insights into the performance of the models used. For PM2.5 estimation, our XGBoost-based models outperformed STLG [59], Space-Time Extra Trees [60], LME [61], and RF [62] reported in prior studies. For O3 estimation, our models surpassed RF [63] and achieved accuracy comparable to WRFC-XGB [64].

Table 5.

Comparison of model performance and validation outcomes with recent studies conducted in various regions.

3.3. Major Impact Factors of PM2.5 and O3 Predictions

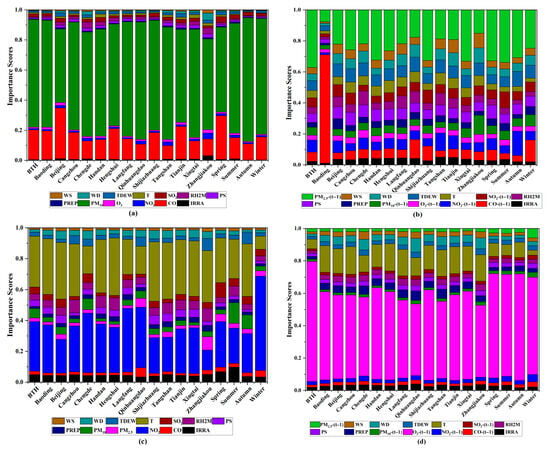

Figure 5a illustrates the variable importance scores for PM2.5 concentrations derived from Model I. Across all investigated cities, PM10 and CO exhibited the most significant impacts on PM2.5, with importance scores exceeding 10%. This is likely due to their shared emission sources and similar dispersion characteristics in the atmosphere. Meteorological parameters showed lower importance scores, possibly because their influence is overshadowed by PM10 and CO. Figure 5b presents the results from Model II, which differ markedly from those of Model I. The lagged PM2.5 concentration (t − 1) consistently had the highest importance score across all cities. Meteorological factors, such as temperature and wind speed, also demonstrated significant impacts, with relatively stable importance scores across different cities and seasons. Notably, the Baoding region stands out, with CO exhibiting a particularly high importance score.

Figure 5.

The importance scores of variables on pollutant prediction for different cities and seasons: (a) Model I for PM2.5 concentration; (b) Model II for PM2.5 concentration; (c) Model I for O3 concentration; (d) Model II for O3 concentration.

Figure 5c presents the variable importance scores for O3 concentration predictions using Model I. The results consistently indicate that temperature and NO2 concentration had the highest importance scores among all parameters, underscoring their critical roles in O3 formation. Under sunlight, nitrogen oxides (NOx) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) undergo photochemical reactions to produce secondary pollutants, including O3. Higher temperatures enhance O3 formation by accelerating these reactions. Notably, the relative importance of temperature and NO2 varied by season: temperature was the dominant factor in spring, summer, and autumn, while the NO2 concentration became the most significant parameter in winter. Additionally, PM10 concentration showed high importance scores in summer and autumn, likely because increased PM10 levels reduce visibility, suppressing O3 generation. Figure 5d illustrates the variable importance scores for O3 concentration forecasts using Model II. Apart from the lagged O3 concentration (t − 1), temperature consistently exhibited the highest scores across most cities and seasons, highlighting its pivotal role in O3 formation. Temperature and surface radiation are key drivers of O3 production due to their influence on atmospheric photochemical reactions. Higher temperatures accelerate the reaction rates of O3 precursors, such as VOCs and NOx, while also promoting VOC evaporation, thereby increasing their atmospheric concentrations. Surface radiation, particularly ultraviolet (UV) radiation from sunlight, provides the energy required for NO2 photolysis, producing reactive oxygen radicals that combine with molecular oxygen to form O3. The intensity of this radiation directly affects the rate of O3 production. These mechanisms are well-documented in the atmospheric chemistry and physics literature [59].

Other meteorological factors, including precipitation, wind, and solar radiation, along with pollutant concentrations such as PM2.5 and NO2, significantly influenced O3 concentrations. The ranking of variable importance scores varied across cities and seasons. Notably, in winter, PM2.5 and NO2 concentrations exhibited higher importance scores than temperature.

Generally, Models I and II showed notable differences in predicting PM2.5 and O3. Model I identified strong associations between PM2.5 and PM10, as well as CO, which can be attributed to the impacts of anthropogenic emissions. In contrast, Model II suggested that both meteorological and anthropogenic emission factors influenced PM2.5 concentrations, with the main contributing factors varying across different cities. The primary reason for these differences may lie in the pollutant lag incorporated in Model II. Meteorological factors tend to affect the diffusion and transformation of pollutants in similar ways, and as a result, their influence on PM2.5 could be overshadowed by the spatial and temporal distribution patterns of other pollutants, such as PM10 and CO. For this reason, Model I did not capture seasonal changes in the main influencing factors for PM2.5 prediction, while Model II did. Similarly, the two models differed in predicting O3 concentrations. Model I identified NO2 and temperature as the primary influencing factors, while Model II found that the main factors varied by city and season. When predicting PM2.5 and O3 using lagged anthropogenic emission factors, it is crucial to consider both anthropogenic and meteorological influences across different cities and seasons.

From the SHAP values of different influencing factors in Figure S9, Model I demonstrates that PM10 has the greatest impact on PM2.5 prediction and NO2 has the greatest impact on O3 prediction. For Model II, SO2 has the greatest impact on PM2.5 prediction and T has the greatest impact on O3 prediction.

3.4. Policy Implications

Suggestions for Different Seasons

- Strengthening Winter Pollution Prevention and Control

Winter is the season with the highest PM2.5 concentrations, which remained elevated from 2019 to 2021. It is recommended to strictly control the combustion of loose coal, promote clean heating alternatives, and increase subsidies for “coal-to-electricity” and “coal-to-gas” transitions in rural areas. Additionally, emission reductions from industrial sources should be intensified, particularly for key industries such as steel and building materials. Stricter production restrictions and emission reduction measures should be implemented during winter, supported by real-time supervision through online monitoring systems. Traffic control should also be optimized by encouraging the use of public transportation and new energy vehicles during peak hours, and imposing regional traffic restrictions on high-emission vehicles to reduce the contribution of vehicle exhausts.

- 2.

- Consolidating Summer Pollution Prevention and Control

Although summer typically has lower PM2.5 concentrations, the concentration in summer 2023 reached 20.69 μg/m3, highlighting the need to consolidate pollution control efforts. Coordinated control of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and nitrogen oxides should be strengthened, as high summer temperatures promote O3 formation, and VOCs are also key precursors for PM2.5. Efforts should focus on controlling VOC emissions from industries like coatings and printing, while simultaneously addressing nitrogen oxide emissions from industrial furnaces and power plants. Meteorological conditions, such as rain and favorable diffusion, should be leveraged to optimize control measures. Emergency emission reduction plans should be developed in advance to respond quickly at the early stages of pollution events, keeping concentrations at lower levels.

- 3.

- Responding to Interannual Fluctuations

The PM2.5 concentration in 2023 showed a rebound compared with 2022 (from 37.4 to 40.5 μg/m3). It is crucial to dynamically adjust emission reduction strategies and establish a “pollution rebound early warning–source tracing–response” mechanism. In the event of a sustained increase in concentration, rapid investigations should be conducted to identify changes in pollution sources, such as the resumption of industrial production or the re-emission of loose coal. Specific controls should be tightened accordingly. Regional joint prevention and control efforts must be intensified, with the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region and surrounding areas acting in unison. Unifying standards for winter production restrictions and emergency emission reduction measures will help avoid concentration rebounds caused by cross-regional pollution transmission.

3.5. Suggestions Based on PM2.5 and O3 Concentration Differences Among Cities

- For PM2.5-Focused Cities (Handan, Xingtai, and Shijiazhuang)

Heavy-industry regulation: These cities should strengthen the transformation of high-pollution industries, such as steel and cement production. Stricter emission standards should be set, advanced pollution-reduction technologies promoted, and phased production cuts scheduled during high-pollution risk periods.

Coal-related emissions reduction: Given the significant contribution of coal combustion to PM2.5, accelerate the shift to clean energy in both industrial and domestic sectors. Strengthen oversight of small-scale coal-fired facilities to ensure the elimination of substandard emissions.

Green barrier construction: Increase the construction of urban green belts, particularly in industrial zones and around transportation hubs. Use vegetation to capture particulate matter and enhance air quality.

Dust management: Strengthen road cleaning and dust suppression measures. Impose stricter dust-control requirements on construction sites, mandating the use of dust-suppression techniques such as enclosures and sprinklers.

- 2.

- For Low-PM2.5 Cities (Chengde and Zhangjiakou)

Ecological conservation: Maintain and further enhance existing ecological advantages. Expand forest coverage and wetland areas to bolster the natural air purification capacity.

Model promotion: Share successful experiences in ecological protection and low-pollution development with other cities. Participate in regional environmental cooperation projects to serve as demonstration areas for air-quality management.

- 3.

- For High-O3 Cities (Cangzhou, Hengshui, and Xingtai)

Industry-specific governance: Focus on industries with high VOC emissions, such as coating and printing. Promote the use of low-VOC raw materials and advanced treatment technologies. Strengthen control over NOx emissions from industrial boilers and vehicles.

Monitoring and early warning: Establish a sophisticated O3 monitoring and early-warning system. Predict high-O3 risk periods based on meteorological conditions and implement temporary emission-reduction measures in advance, such as adjusting industrial production schedules and imposing vehicle travel restrictions.

Data-sharing platform: Create a regional air-quality data-sharing platform to ensure the timely exchange of monitoring data between cities. Facilitate joint analysis of pollution sources and transmission paths.

Coordinated action plan: Develop a unified regional air-pollution control action plan. During extreme pollution events, cities should collaborate on implementing emergency measures, such as unified vehicle restrictions and industrial production adjustments, to prevent cross-city pollution transmission.

Future research should focus on improving model interpretability to gain a better understanding of the complex interactions between variables and pollutant formation mechanisms. Incorporating additional data sources, such as real-time traffic flow, industrial activity, and satellite remote sensing, could enhance both model accuracy and spatial resolution. Furthermore, integrating chemical transport models with machine learning approaches may offer deeper insights into pollutant dynamics and atmospheric chemistry. Long-term monitoring and validation across diverse geographic regions will be crucial for generalizing the applicability of the models. Addressing these challenges will strengthen air pollution prediction capabilities and support more effective environmental policies and management strategies.

4. Conclusions

This study investigates the spatiotemporal distribution of PM2.5 and O3 in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei (BTH) region and applies machine learning algorithms for concentration prediction, leading to the following key findings.

- Spatiotemporal Patterns of Pollutants

Seasonal variations: PM2.5 shows a decreasing trend from 2019 to 2023 (49.39 to 37.4 μg/m3), with a rebound in 2023 (40.5 μg/m3). It peaks in winter (up to 79.79 μg/m3) due to heating emissions and stable meteorological conditions and reaches its lowest levels in summer (20.69 μg/m3). O3 exhibits stable annual mean concentrations (63.45–69.84 μg/m3), with the highest levels in summer (due to photochemical reactions) and the lowest in winter (due to cold-induced inhibition). Spatial differences: PM2.5 concentrations are highest in Handan, Xingtai, and Shijiazhuang, while Chengde and Zhangjiakou show lower levels. Spatial variations in O3 are less pronounced, but higher concentrations are observed in Shijiazhuang, Hengshui, and Xingtai.

- 2.

- Machine Learning Models for Pollution Prediction

Model performance: XGBoost outperforms both FCNN and RF in predicting PM2.5 and O3, with testing R2 values of 0.979 (for PM2.5) and 0.938 (for O3), demonstrating its strong capability in capturing spatiotemporal pollution patterns. Model I (without lagged variables) is highly effective in associating pollutants with emission sources (e.g., PM10 and CO for PM2.5), while Model II (with lagged variables) emphasizes meteorological impacts (temperature and wind speed) on pollutant diffusion. Applicability: Both models effectively forecast pollutant concentrations across cities, though Model II shows lower accuracy due to the complex interactions between emissions and meteorological factors.

- 3.

- Key Influencing Factors

PM2.5: PM10 and CO are the dominant drivers (with importance >10%) due to shared emission sources (e.g., fuel combustion and industrial processes). Meteorological factors such as temperature and wind speed play a significant role in Model II, with variations across cities (e.g., CO in Baoding). O3: Temperature and NO2 are key contributors, with temperature being more influential during warm seasons and NO2 during winter. PM10 also suppresses O3 formation during summer and autumn by reducing visibility.

- 4.

- Policy Implications and Future Directions

Seasonal and urban-specific recommendations are as follows. Winter: Strengthen clean heating solutions, enforce industrial emission reductions, and improve traffic control measures. Summer: Co-manage VOCs and NOx emissions to mitigate O3 formation. High-PM2.5 cities: Focus on regulating heavy industries and reducing coal combustion. Low-PM2.5 cities: Promote ecological conservation and natural air purification. Future research: Focus on improving model interpretability, integrating real-time data (e.g., traffic and industrial activity), and combining machine learning techniques with chemical transport models to enhance prediction accuracy and support policymaking.

In summary, this study provides empirical evidence on pollution dynamics and introduces robust prediction tools that can support targeted air quality management strategies in the BTH region.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su17209211/s1, Table S1. Parameter setting of the models using different machine learning algorithms. Figure S1: The performance of XGBoost (a), RF (b), and FCNN (c) models in training and predicting PM2.5 and O3 (Model I). Figure S2. The performance of XGBoost (a), RF (b), and FCNN (c) models in training and predicting PM2.5 and O3 (Model II). Figure S3. XGBoost prediction of PM2.5 concentrations in Shijiazhuang and Langfang areas, and O3 concentrations in Beijing and Zhangjiakou areas (Model I, testing dataset). Figure S4. XGBoost prediction of PM2.5 concentrations in Beijing and Zhangjiakoug areas, and O3 concentrations in Beijing and Qinhuangdao areas (Model II, testing dataset). Figure S5. XGBoost’s performance in predicting PM2.5 levels in spring, summer, autumn, and winter (Model I). Figure S6. XGBoost’s performance in predicting O3 levels in spring, summer, autumn, and winter (Model I). Figure S7. XGBoost’s performance in predicting PM2.5 levels in spring, summer, autumn, and winter (Model II). Figure S8. XGBoost’s performance in predicting O3 levels in spring, summer, autumn, and winter (Model II). Figure S9. The SHAP value of variables on pollutant prediction for BTH: (a) Model I for PM2.5 concentration; and (b) Model I for O3 concentration; (c) Model II for PM2.5 concentration; (d) Model II for O3 concentration. References [65,66,67] are cited in Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.H.; Methodology: C.W.; Software: C.W.; Validation: C.Z.; Formal Analysis: C.Z.; Investigation: C.W.; Resources: C.W.; Data Curation: C.W.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation: C.W.; Writing—Review and Editing: Y.H.; Visualization: Y.T.; Supervision: Y.T.; Project Administration: C.Z.; Funding Acquisition: C.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFD1601001).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank NASA for providing the meteorological data through the POWER (Prediction of Worldwide Energy Resource) project (https://power.larc.nasa.gov/data-access-viewer, accessed on 1 February 2024), which was essential for our analysis. We are also grateful to the reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions that greatly improved this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, C.; van Donkelaar, A.; Hammer, M.S.; McDuffie, E.E.; Burnett, R.T.; Spadaro, J.V.; Chatterjee, D.; Cohen, A.J.; Apte, J.S.; Southerland, V.A.; et al. Reversal of trends in global fine particulate matter air pollution. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, J.; Gao, J.; Cheng, S.; Zhao, X.; Xia, X.; Hu, B. Impacts of aerosol direct effects on PM2.5 and O3 respond to the reductions of different primary emissions in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei and surrounding area. Atmos. Environ. 2023, 309, 119948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ren, Y.; Xia, B. PM2.5 and O3 concentration estimation based on interpretable machine learning. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2023, 14, 101866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Li, Y.; Tao, J.; Fan, M.; Chen, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y. Full-coverage estimation of PM2.5 in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region by using a two-stage model. Atmos. Environ. 2023, 309, 119956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Lu, P.; Chen, Z.; Liu, R. Ozone Concentration Estimation and Meteorological Impact Quantification in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region Based on Machine Learning Models. Earth Space Sci. 2024, 11, e2023EA003346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.J.; Lee, S.C.; Ho, K.F.; Fung, K. Characteristics, sources, and health impacts of atmospheric particulate matter in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 659, 400–413. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.H.; Zhang, Y.H.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, B.; He, K.B.; Cofala, J. China’s anthropogenic sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and primary fine particulate matter emissions, 1990–2015: A high-resolution emission inventory. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17, 11925–11952. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, S.; He, K. Vehicle emission control in China: Review and outlook. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 619–620, 1195–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Q.; He, K.B.; Zheng, B.; Streets, D.G. Anthropogenic mercury emissions in China during 1990–2010: A provincial-level inventory. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016, 16, 15609–15622. [Google Scholar]

- Crutzen, P.J. The role of NO and NO2 in the chemistry of the troposphere and stratosphere. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1979, 322, 16–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Streets, D.G.; He, K.B.; Wang, S.X. Ozone trends in China from 1991 to 2012: Analysis of surface observations and model simulations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2014, 14, 5819–5834. [Google Scholar]

- Pope, C.A.; Dockery, D.W. Health effects of fine particulate air pollution: Lines that connect. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2006, 56, 709–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, R.D.; Rajagopalan, S.; Pope, C.A., 3rd; Brook, J.R.; Bhatnagar, A.; Diez-Roux, A.V.; Holguin, F.; Hong, Y.; Luepker, R.V.; Mittleman, M.A.; et al. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: An update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2010, 121, 2331–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krewski, D.; Jerrett, M.; Burnett, R.T.; Ma, R.; Hughes, E.; Shi, Y.; Turner, M.C.; Pope, C.A., 3rd; Thurston, G.; Calle, E.E.; et al. Extended Follow-Up and Spatial Analysis of the American Cancer Society Study Linking Particulate Air Pollution and Mortality; Research Report; Health Effects Institute: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 5–86, discussion 115–136. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, B.; Cofala, J.; He, K.B. Emission trends and future projections of air pollutants in China: Implications for air quality improvement. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2023, 23, 3229–3246. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, R.; Arey, J. Atmospheric degradation of volatile organic compounds. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 4605–4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, M.L.; McDermott, A.; Zeger, S.L.; Samet, J.M.; Dominici, F. Ozone and short-term mortality in 95 US urban communities, 1987–2000. JAMA 2006, 295, 1087–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Zhang, Q.; He, K.B.; Wang, S.; Streets, D.G. Tropospheric ozone in China: Concentrations, trends, and sources. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 13239–13258. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Zhong, Z.; Sha, Q.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Cui, X.; Tang, M.; et al. An updated model-ready emission inventory for Guangdong Province by incorporating big data and mapping onto multiple chemical mechanisms. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 769, 144535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, X.; Mi, Z.; Georgopoulos, P.G. Comparison of Machine Learning and Land Use Regression for fine scale spatiotemporal estimation of ambient air pollution: Modeling ozone concentrations across the contiguous United States. Environ. Int. 2020, 142, 105827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, S.; Ismail, M.; Ahmed, A.N. Identification of air pollution potential sources through principal component analysis (PCA). Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 2018, 9, 1435–1442. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, A.; Lella, R.L. Pearson correlation coefficient based attribute weighted k-nn for air pollution prediction. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 17th India Council International Conference (INDICON), New Delhi, India, 10–13 December 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hoek, G.; Beelen, R.; de Hoogh, K.; Vienneau, D.; Gulliver, J.; Fischer, P.; Briggs, D. A review of land-use regression models to assess spatial variation of outdoor air pollution. Atmos. Environ. 2008, 42, 7561–7578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Wang, C.; Fang, S. Application of geographically weighted regression (GWR) in the analysis of the cause of haze pollution in China. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2019, 10, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, V.O.K.; Lam, J.C.K. Deep-AIR: A Hybrid CNN-LSTM Framework for Air Quality Modeling in Metropolitan Cities. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.14587. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Belle, J.H.; Meng, X.; Wildani, A.; Waller, L.A.; Strickland, M.J.; Liu, Y. Estimating PM2.5 Concentrations in the Conterminous United States Using the Random Forest Approach. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 6936–6944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Batterman, Z.S. Air pollution and health risks due to vehicle traffic. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 450–451, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Batterman, S. Air pollution prediction using XGBoost with multiple spatiotemporal features. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2019, 10, 768–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jogin, M.; Mohana; Madhulika, M.S.; Divya, G.D.; Meghana, R.K.; Apoorva, S. Feature Extraction using Convolution Neural Networks (CNN) and Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 3rd IEEE International Conference on Recent Trends in Electronics, Information & Communication Technology (RTEICT), Bangalore, India, 18–19 May 2018; pp. 2319–2323. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Wang, F.; Guo, Y.; Liu, C.; Ji, D.; Wang, Y.; Xu, X.; Lu, X.; Wang, Y.; Carmichael, G.; et al. Reconstructed daily ground-level O3 in China over 2005–2021 for climatological, ecological, and health research. Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, K.; Che, H.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhai, S.; Wang, Z.; Luo, M.; Zhang, L.; Liao, T.; Zhao, H.; et al. Construction of a virtual PM2.5 observation network in China based on high-density surface meteorological observations using the Extreme Gradient Boosting model. Environ. Int. 2020, 141, 105801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Jiang, J.; Tong, L.; Huang, P. FCNN+: An Improved Fully Connected Neural Network High-accuracy Prediction Model. In Proceedings of the 2023 8th International Conference on Information Systems Engineering (ICISE), Dalian, China, 23–25 June 2023; pp. 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Zhao, Y.; Luo, M.; He, Q.; Han, Y.; Zeng, Z. Estimating PM2.5 from multisource data: A comparison of different machine learning models in the Pearl River Delta of China. Urban Clim. 2021, 35, 100740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.P. Machine Learning: A Probabilistic Perspective; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, P.; Zhan, S.; Mishra, V.; Aekakkararungroj, A.; Markert, A.; Paibong, S.; Chishtie, F. Machine learning algorithm for estimating surface PM2.5 in Thailand. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2021, 21, 210105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.V.; Shi, Z.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, Q.; He, K.; Wang, S.; Harrison, R.M. Assessing the impact of clean air action on air quality trends in Beijing using a machine learning technique. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019, 19, 11303–11314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Deng, F.; Cai, Y.; Chen, J. Long short-term memory-Fully connected (LSTM-FC) neural network for PM2.5 concentration prediction. Chemosphere 2019, 220, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauschmayr, N.; Kumar, V.; Huilgol, R.; Olgiati, A.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Harish, N.; Kenthapadi, K. Amazon sagemaker debugger: A system for real-time insights into machine learning model training. Proc. Mach. Learn. Syst. 2021, 3, 770–782. [Google Scholar]

- Takoutsing, B.; Heuvelink, G.B.M. Comparing the prediction performance, uncertainty quantification and extrapolation potential of regression kriging and random forest while accounting for soil measurement errors. Geoderma 2022, 428, 116192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaysse, K.; Lagacherie, P. Using quantile regression forest to estimate uncertainty of digital soil mapping products. Geoderma 2017, 291, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Li, H.; Gao, Y. Analysis of the impact of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei coordinated development on environmental pollution and its mechanism. Environ. Monit. Assess 2022, 194, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monks, P.S.; Archibald, A.T.; Colette, A.; Cooper, O.; Coyle, M.; Derwent, R.; Fowler, D.; Granier, C.; Law, K.S.; Mills, G.E.; et al. Tropospheric ozone and its precursors from the urban to the global scale from air quality to short-lived climate forcer. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 8889–8973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, D.J.; Winner, D.A. Effect of climate change on air quality. Atmos. Environ. 2009, 43, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Jimenez, J.L.; Canagaratna, M.R.; Ulbrich, I.M.; Ng, N.L.; Worsnop, D.R.; Sun, Y. Understanding atmospheric organic aerosols via factor analysis of aerosol mass spectrometry: A review. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011, 401, 3045–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, S.P. Air Pollution Meteorology and Dispersion; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Han, L.; Lan, T.; Cheng, S.; Wang, Y.; Qi, C.; Tian, J.; Wang, H.; Han, D.; Wang, S. Evolution Characteristics of PM2.5 and O3 and Their Synergistic Effects on Atmospheric Compound Pollution in Tangshan. Environ. Sci. 2024, 45, 4385–4397. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, C.; Evtyugina, M.; Vicente, E.; Vicente, A.; Rienda, I.C.; de la Campa, A.S.; Duarte, I. PM2. 5 chemical composition and health risks by inhalation near a chemical complex. J. Environ. Sci. 2023, 124, 860–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Zhang, L.; Yao, C.; Xie, T.; Rao, L.; Lu, H.; Lu, S. Relationships between chemical elements of PM2.5 and O3 in Shanghai atmosphere based on the 1-year monitoring observation. J. Environ. Sci. 2020, 95, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seinfeld, J.H.; Pandis, S.N. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics: From Air Pollution to Climate Change; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ervens, B.; Turpin, B.J.; Weber, R.J. Secondary organic aerosol formation in cloud droplets and aqueous particles (aqSOA): A review of laboratory, field and model studies. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011, 11, 11069–11129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Zhang, L.; Cao, J.; Zhong, L.; Chen, D.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, R. Source apportionment of PM2. 5 at urban and suburban areas of the Pearl River Delta region, south China-With emphasis on ship emissions. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 574, 1559–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Long, X.; Li, Y.; Zang, Z.; Wang, F.; Han, Y.; Yang, J. Impacts of meteorology and emission reductions on haze pollution during the lockdown in the North China Plain. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2025, 25, 1569–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Yuan, R.; Wu, B.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, H.; Gong, Z. Meteorological conditions conducive to PM2. 5 pollution in winter 2016/2017 in the Western Yangtze River Delta, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 642, 1221–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, U.A.; Yan, Y.; Zhou, M.; Ali, S.; Hussain, A.; Qingsong, H.; Yuan, L. Time series analysis and forecasting of air pollution particulate matter (PM 2.5): An SARIMA and factor analysis approach. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 41019–41031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Ban, X.; Ji, L.; Guan, X.; Liu, K.; Qian, X. An Adaptive Shrinking Grid Search Chaotic Wolf Optimization Algorithm Using Standard Deviation Updating Amount. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2020, 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, S.; Liu, H.-M.; Tsai, T.-C.; Chen, L.-J. Improving the Accuracy and Efficiency of PM2.5 Forecast Service Using Cluster-Based Hybrid Neural Network Model. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 19193–19204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.B.; Sugimoto, N.; Matsui, I.; Shimizu, A.; Tatarov, B.; Kamei, A.; Westphal, D.L. Long-range transport of Saharan dust to east Asia observed with lidars. Sola 2005, 1, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Li, R.; Cui, L.; Meng, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Fu, H. Satellite-based prediction of daily SO2 exposure across China using a high-quality random forest-spatiotemporal Kriging (RF-STK) model for health risk assessment. Atmos. Environ. 2019, 208, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Xiao, Q.; Meng, X.; Geng, G.; Wang, Y.; Lyapustin, A.; Gu, D.; Liu, Y. Predicting monthly high-resolution PM2.5 concentrations with random forest model in the North China Plain. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 242 Pt A, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Li, Z.; Lyapustin, A.; Sun, L.; Peng, Y.; Xue, W.; Cribb, M. Reconstructing 1-km-resolution high-quality PM2.5 data records from 2000 to 2018 in China: Spatiotemporal variations and policy implications. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 252, 112136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhang, C.; Li, Z.; Pinker, R.T.; Wang, J.; Sun, L.; Xue, W.; Li, R.; Cribb, M. Himawari-8-derived diurnal variations in ground-level PM 2.5 pollution across China using the fast space-time Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 7863–7880. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, C.R.; Hwang, B.F.; Chen, W.T. Incorporating long-term satellite-based aerosol optical depth, localized land use data, and meteorological variables to estimate ground-level PM2.5 concentrations in Taiwan from 2005 to 2015. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 237, 1000–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Ban, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; He, M.Z.; Li, T. Random forest model based fine scale spatiotemporal O3 trends in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region in China, 2010 to 2017. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 276, 116635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhang, J.; Xue, W.; Zhou, L.; Che, Y.; Han, T. Estimation of the near-surface ozone concentration with full spatiotemporal coverage across the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region based on extreme gradient boosting combined with a WRF-chem model. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Rumelhart, D.E.; Hinton, G.E.; Williams, R.J. Learning representations by back-propagating errors. Nature 1986, 323, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).