Abstract

The sustainable preservation of cultural heritage, as articulated in Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11.4, requires strategies that not only safeguard tangible and intangible assets but also enhance their long-term cultural, social, and economic value. Artificial intelligence (AI) and digital technologies are increasingly applied in heritage conservation. However, most research emphasizes technical applications, such as improving data accuracy and increasing efficiency, while neglecting their integration into a broader framework of cultural sustainability and heritage tourism. This study addresses this gap by developing a set of practical guidelines for the sustainable use of AI in cultural heritage preservation. The guidelines highlight six dimensions: inclusive data governance, data authenticity protection, leveraging AI as a complementary tool, balancing innovation with cultural values, ensuring copyright and ethical compliance, long-term technical maintenance, and collaborative governance. To illustrate the feasibility of these guidelines, the paper analyses three representative case studies: AI-driven 3D reconstruction of the Old Summer Palace, educational dissemination via Google Arts & Culture, and intelligent restoration at E-Dunhuang. By situating AI-driven practices within the framework of cultural sustainability, this study makes both theoretical and practical contributions to heritage governance, to enhance cultural sustainability commitments and align digital innovation with the enduring preservation of humanity’s shared heritage, providing actionable insights for policymakers, institutions, and the tourism industry in designing resilient and culturally respectful heritage strategies.

1. Introduction

The safeguarding of cultural heritage has increasingly been recognized as a cornerstone of sustainability, as cultural resources form an integral part of social identity, collective memory, and community resilience []. The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11.4 explicitly calls for strengthened global efforts to “protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage,” underscoring the vital importance of heritage as both a cultural and sustainable resource. Within this framework, the concept of cultural sustainability has gained growing attention. Artificial Intelligence (AI) technologies are an emerging technology for the sustainable preservation of cultural heritage, which is increasingly employed in various aspects of cultural heritage sustainable development, such as preservation, reconstruction, restoration, and dissemination, to ensure sustainable preservation, intergenerational transmission, and promote heritage tourism. Digital cultural heritage is a novel solution for the sustainability of cultural heritage [].

However, current research on digital cultural heritage focuses on a critical analysis of AI usage in cultural heritage preservation. Chowdhury and Sadek [] believe that AI provides the advantages of permanence, reliability, and cost-effectiveness, allowing for quicker and less expensive problem-solving [] (pp. 4–5), while also having challenges, including the digital divide, concerns about authenticity, and ethical skepticism [,,]. Current scholarship often treats cultural sustainability as an incidental by-product of technological progress rather than as a guiding principle. As a result, there remains a lack of clear, practical guidelines on how AI can be used to advance cultural sustainability in ways that are authentic, inclusive, and future-oriented.

As a result, this paper addresses this gap by developing a set of practical guidelines for the sustainable application of AI in cultural heritage. These guidelines are grounded in three key representations of cultural sustainability—culture in sustainability, culture as sustainability, and culture for sustainability—and are illustrated through analysis of three representative case studies: the Dunhuang murals, the Old Summer Palace (Yuanmingyuan), and Google Arts & Culture. By aligning AI-driven practices with the principles of cultural sustainability, this study contributes to both academic debates and actionable strategies for heritage professionals, policymakers, and the tourism sector. Ultimately, the paper demonstrates how AI can be harnessed not merely as a technical tool but as part of a holistic cultural governance approach, positioning AI within broader sustainability agendas, linking digital innovation to global heritage stewardship and the responsibilities articulated in SDG 11.4.

2. Literature Review

Sustainable cultural heritage preservation, as articulated in Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11.4, necessitates strategies that ensure the long-term safeguarding of both tangible and intangible heritage while mitigating the risks of degradation. Within this framework, the concept of cultural sustainability has gained prominence, referring to a society’s capacity to preserve, transmit, and revitalize its cultural heritage across generations while fostering inclusivity, authenticity, and resilience []. Cultural sustainability thus extends beyond technical protection, emphasizing intergenerational continuity, equitable accessibility, and the safeguarding of cultural values. Situating heritage preservation within this framework makes it clear that sustainability is not limited to technical protection but also involves ensuring equitable accessibility, supporting intergenerational transmission, and enabling communities to sustain their cultural identities in the face of globalization and technological change.

2.1. From Traditional Methods to Digital Approaches

Sustainable cultural heritage preservation has evolved from traditional to digital methods. Traditional methods of cultural heritage preservation are mainly hand measurement, photography, and repeated experimentation [,]. Computer-based applications have gradually replaced manual methods in archaeology and conservation, enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of analysis [] (pp. 1–2). For example, hand measurement methods, which were highly dependent on accuracy, have been superseded by 3D measurement technology to enhance the accuracy of structural modelling and condition assessment of artefacts, allowing for the early identification of potential deterioration issues [,]. Static photography has evolved into a virtual reality application that offers a static simulation display and interactive experiences between cultural heritage and humans []. Time-consuming repeated experimentation is changed to digital twin mapping [] (p. 1), which creates a twin heritage model to predict preservation needs by analyzing the deterioration pattern [,].

In addition, digital technology has also given rise to new approaches of cultural sustainability, including digital collection and documentation, digital research and information management, and digital presentation and interpretation [] (p. 335). Specific applications include digital archiving [] (p. 1), where people utilize machine learning techniques to analyze and classify texts, photos, and other data, thereby expanding both research capacity and public access to achieve sustainable heritage [] (p 185). Three-dimensional modelling technologies are also central to sustainability, enabling digital reconstruction of lost or damaged elements while maintaining authenticity and transparency [,]. Furthermore, virtual reality technology can reproduce ancient ruins without altering the original site [] (p. 1079), providing a multisensory experience through visual, tactile, and auditory means [] (p. 535). These practices enhance both the safeguarding of heritage and its sustainable transmission to broader and more diverse audiences, promoting the heritage tourism approach and ensuring that culture remains accessible across generations.

2.2. Cultural Sustainability as an Analytical Lens

Sustainable cultural heritage preservation, as articulated in Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11.4, necessitates strategies that ensure the long-term safeguarding of both tangible and intangible heritage while mitigating risks of degradation. Within this context, the concept of cultural sustainability has gained prominence as an analytical framework. As Soini and Birkeland [] argue, cultural sustainability can be understood through three key representations: culture in sustainability, culture for sustainability, and culture as sustainability.

Culture in Sustainability positions culture as one of the four fundamental pillars of sustainable development, alongside the economic, social, and environmental dimensions. From this perspective, cultural heritage contributes to sustainability by preserving authenticity, safeguarding traditions, and maintaining cultural diversity for future generations.

Culture for Sustainability highlights culture’s role in promoting broader sustainability goals, such as fostering social inclusion, encouraging community participation, and generating sustainable economic benefits through activities like heritage tourism. In this view, cultural heritage becomes a tool to drive sustainable education, economic growth, and social cohesion.

Culture as Sustainability frames culture itself as the very essence of sustainability, where the continuation, revitalization, and adaptive transformation of cultural practices are understood as sustainable development in action. Here, resilience—the ability of cultural heritage to adapt to change while retaining its core values—is central.

Taken together, these three representations emphasize that cultural sustainability is not limited to technical conservation but extends to questions of authenticity, inclusivity, and resilience. This conceptualization provides a strong foundation for evaluating how Artificial Intelligence (AI) and digital technologies can support the sustainable safeguarding and transmission of cultural heritage.

Nevertheless, embedding sustainability into cultural heritage preservation also requires critical reflection on the limitations and risks of technological approaches. As Acke et al. [] (p. 282) caution, “AI should always be a well-considered and certainly not an automatic choice”. The first challenge is the digital divide. The use of AI heavily depends on the available equipment and individual skills [] (p. 282). If all cultural heritage is stored and displayed digitally, AI in cultural heritage preservation will disproportionately serve the interests of the elite, further marginalizing subaltern communities [] (p. 133). Another concern is authenticity. While AI enables heritage to exist in digital form, digitization cannot fully replace the meaning and materiality of the original. Moreover, the increasing dominance of screen-based culture risks shaping collective memory through technological filters rather than humanistic reflection [] (p. 4). Questions of technological sustainability also arise, as digital archives depend on software and infrastructure that may deteriorate, become obsolete, or prove unstable [,]. Even materials introduced through AI-based restoration, such as biopolymers, may lack durability under environmental stress [] (p. 282). Lastly, concerns have been raised about copyrights and the replacement of traditional craftsmanship [] (p. 282). These challenges underscore that achieving cultural sustainability requires not only technological innovation but also effective governance, inclusive policies, and a balanced integration of human expertise and digital tools.

2.3. Existing Guidelines on Cultural Sustainability and AI

Currently, international organizations and the professional communities of cultural heritage protection have generated and implemented some well-developed and effective guidelines regarding the application of AI technology for the sustainable protection of cultural heritage, aiming to embed sustainability into cultural heritage protection under conditions of rapid technological change.

At the European level, the Council of Europe [] approved the document Guidelines, which, given the latest technological developments, such as AI, complement the Council of Europe’s standards in the fields of culture, creativity, and cultural heritage. This text focuses on four areas: (1) ensuring equal and safe access to AI-supported cultural services; (2) building trust and cooperation between cultural institutions and digital technology providers; (3) strengthening ethical and rights-based governance, particularly around copyright, privacy, and cultural bias; and (4) supporting long-term resilience by aligning digital innovation with democratic values and cultural diversity. These recommendations emphasize that technological tools should not replace but rather complement human expertise, and that cultural diversity must be protected against the homogenizing tendencies of global platforms.

UNESCO’s Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence [] provides a broader ethical umbrella. It identifies principles highly relevant for cultural heritage, such as transparency in algorithmic decision-making, fairness in access, accountability of institutions using AI (3.0), and respect for cultural and linguistic diversity. Although not heritage-specific, it sets out global standards that any AI-driven heritage initiative should adhere to, particularly in terms of authenticity and inclusivity.

In parallel, ICOMOS adopted the International Charter for Cultural Heritage Tourism [], which directly links heritage tourism with sustainability. It stresses the importance of community participation, protection of cultural values against over-commercialization, and the development of responsible tourism models that generate long-term social and economic benefits without compromising authenticity. This is especially pertinent as many AI and digital heritage projects now intersect with tourism, using immersive technologies to attract new audiences while raising concerns about commodification.

Finally, UNESCO [] and regional organizations have highlighted Indigenous data sovereignty in AI-driven heritage contexts, particularly in Latin America and the Caribbean. These guidelines emphasize community control over cultural data, knowledge ownership, and the right to consent and participation in projects involving digitization or algorithmic processing of Indigenous heritage. Such recommendations reveal that sustainability in cultural heritage is inseparable from equity and inclusivity in governance models.

Based on the current guidance and AI usage in real cases. This paper explicitly applies the cultural sustainability framework to AI-driven heritage practices, providing practical guidelines for translating the principles of culture in, for, and as sustainability into concrete heritage management strategies. By developing guidelines that correspond to authenticity (culture in sustainability), inclusivity (culture for sustainability), and resilience (culture as sustainability), and by examining three representative case studies—the Dunhuang murals, the Old Summer Palace (Yuanmingyuan), and Google Arts & Culture—this study offers a practical guideline for academic debates and actionable strategies for heritage professionals, policy-makers, and the tourism sector.

3. Practical Guidelines for Cultural Sustainability

Currently, most guidelines focus on five aspects: (1) safe and transparent data inquiry; (2) cooperate with professional communities; (3) long-term maintenance and update; (4) respect copyright; (5) against over-commercialization. These existing guidelines provide important starting points, emphasizing authenticity, inclusivity, governance, ethical safeguards, and community participation. However, they remain general and often fragmented across different domains (ethics, tourism, Indigenous rights, digital governance). Building upon existing guidelines and incorporating current real-world examples of artificial intelligence applied to the sustainable preservation of cultural heritage, this study builds on these foundations by synthesizing them into six practical guidelines tailored to AI applications in cultural heritage. These guidelines are then tested and refined through representative case studies.

3.1. Guideline 1: Ensuring Cultural Authenticity Through Inclusive Data Governance

This guideline puts culture in sustainability, treating culture as an independent dimension of sustainability that requires direct protection and inheritance. Sustainable digital heritage preservation begins with rigorous and inclusive data governance. AI systems rely on datasets for tasks such as restoration, reconstruction, and presentation. If datasets are incomplete or biased, restoration risks becoming inaccurate or privileging dominant narratives while silencing minority perspectives. Such distortions can undermine the authenticity of cultural heritage and erode long-term trust. Inclusive governance requires the establishment of provenance records for each dataset, the use of internationally recognized metadata standards (such as CIDOC-CRM or IIIF), and the inclusion of multiple languages and community voices in annotation processes. Moreover, algorithm auditing and the responsibility of relevant personnel should be institutionalized to ensure that AI-generated outputs align with historical accuracy and cultural values. From a heritage tourism perspective, authentic data governance ensures that the cultural experiences presented to tourists are historically credible, thereby reinforcing the educational and cultural value of tourism rather than reducing it to mere spectacle.

3.2. Guideline 2: Positioning AI as a Complementary Tool Rather than a Replacement for Human Expertise

This guideline is based on Culture in Sustainability and Culture for Sustainability. Using AI technology to protect the heritage culture itself, viewing cultural heritage as the fourth pillar in sustainability. AI has proven highly effective at automating repetitive heritage tasks, such as cataloguing, predictive monitoring, and structural analysis. However, heritage embodies meanings, emotions, and symbolic values that exceed computational interpretation. To ensure cultural sustainability, AI should be positioned as a decision-support tool, with ultimate authority resting with heritage professionals. For instance, while AI can identify patterns of deterioration in wall paintings, final conservation strategies should remain under expert judgment. Human-in-the-loop frameworks not only safeguard authenticity but also support the integration of traditional craftsmanship into digital practices. From the perspective of heritage tourism, this balance enriches visitors’ experiences by ensuring that reconstructed or digitally enhanced heritage retains its cultural depth and emotional resonance, rather than appearing as artificially generated artifacts detached from human history.

3.3. Guideline 3: Balancing Innovation with the Preservation of Cultural Values

Culture for sustainability means culture is the resource that promotes economic and social sustainability, including heritage tourism. The innovation in cultural heritage dissemination is mainly used as a tool to enhance the benefits of education, tourism, and economy. Digital technologies such as VR and interactive reconstructions offer immersive ways to experience cultural heritage. While these innovations expand accessibility and generate new opportunities for tourism, they also risk prioritising visual appeal or commercialisation at the expense of historical accuracy. To achieve cultural sustainability, institutions must adopt a principle of “authenticity before aesthetics,” making clear distinctions between verified reconstructions, interpretive simulations, and speculative designs. Transparency in labelling and user interface design is essential, ensuring that audiences—including heritage tourists—understand what is original and what is reconstructed. By doing so, heritage tourism can move beyond spectacle-driven consumption and provide tourists with historically informed, educational, and ethically grounded experiences. This enhances both visitor satisfaction and the sustainable cultural value of tourism industries.

3.4. Guideline 4: Establishing Robust Copyright and Rights Management

Guideline 4 is based on Culture in Sustainability and Culture for Sustainability. Copyright is a measure to protect the integrity of cultural works themselves and respect originality. Realize the return of cultural industry revenue through copyright management and use it for protection and tourism development. Sustainability in digital heritage also depends on legal and ethical integrity. Many heritage institutions hesitate to share digital content due to concerns about piracy and unauthorised commercial use, particularly when high-resolution images are involved. To address these risks, institutions must implement copyright audits, access controls, and technological protections such as watermarking and metadata embedding. At the same time, equitable licensing models can ensure that the digitisation of heritage contributes financially to preservation efforts. In the context of heritage tourism, robust copyright management can facilitate the fair commercialization of cultural products—such as licensed replicas, souvenirs, and digital exhibitions—while ensuring that revenue is reinvested in conservation and community development. This approach supports a sustainable cultural economy in which both creators and heritage custodians benefit.

3.5. Guideline 5: Developing Long-Term Maintenance and Lifecycle Plans for AI Systems

The maintenance and update of AI itself is not at the core of “culture”, but rather a means to ensure the long-term accessibility and intergenerational inheritance of culture. This is a match with the culture of sustainability. The sustainability of digital heritage depends not only on its creation but also on its long-term viability. Digital archives and AI systems are vulnerable to software obsolescence, hardware degradation, and shifting infrastructure. Without proactive lifecycle planning, valuable cultural data risks becoming inaccessible within decades. To prevent this, institutions should implement lifecycle frameworks that cover data migration, system updates, retraining of AI models, and partnerships for technical support. Cloud-based repositories, containerisation, and adherence to open standards can ensure resilience across generations. Importantly, heritage tourism also benefits from long-term system stability, as tourists, educators, and researchers can reliably access cultural heritage resources, enabling tourism industries to continuously develop sustainable products, such as VR exhibitions and educational tours. A well-maintained digital heritage infrastructure thus contributes directly to the resilience and growth of cultural tourism.

3.6. Guideline 6: Establishing Ethical Guidelines and Collaborative Governance

Ultimately, sustainable heritage preservation necessitates governance that combines technological expertise with cultural and ethical considerations. This is culture as sustainability. Understanding culture as an overarching framework for social sustainability necessitates a shift in values and governance structures. AI applications may risk cultural homogenisation, misrepresentation, or community exclusion if developed without inclusive participation. To address this, institutions should adopt collaborative governance models that include heritage professionals, technologists, ethicists, policymakers, and community representatives. Multidisciplinary governance committees can ensure that decisions around restoration, data use, and public dissemination are made transparently and equitably. Ethical guidelines should include accountability mechanisms such as public reporting and periodic audits. From the standpoint of heritage tourism, collaborative governance ensures that tourism narratives remain inclusive and culturally respectful, preventing the dominance of Western-centric or commercial interpretations. This inclusivity strengthens community engagement while enriching the authenticity of tourism experiences.

4. Case Studies

To translate the proposed guidelines into practice, this section examines three representative case studies of AI applications in cultural heritage. Rather than treating these cases as independent narratives, they are analyzed as supporting evidence that demonstrates how the guidelines can be applied to real-world contexts. Each case highlights a different dimension of cultural sustainability. The E-Dunhuang case underscores the importance of data governance and authenticity, illustrating how AI-assisted restoration can enhance accuracy and efficiency while complementing, rather than replacing, human expertise. The Old Summer Palace (Yuanmingyuan) exemplifies the risks of excessive reliance on virtual reconstruction, highlighting the need to strike a balance between technological innovation and the preservation of cultural values and emotional depth. Ultimately, Google Arts & Culture showcases the potential of digital platforms to enhance accessibility and foster global cultural engagement, while also highlighting critical concerns regarding copyright, technological sustainability, and cultural bias.

4.1. E-Dunhuang

The sustainable development of the Digital Dunhuang Project centres on electronic databases and intelligent restoration. This demonstrates the successful application of Guideline 2: adopting AI as a complementary tool, not a replacement for human expertise, and Guideline 5: developing long-term maintenance plans for AI systems in practice.

The Dunhuang Caves, inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1987 [] (p. 987), represent one of the most significant repositories of historical and cultural heritage in the world. It was built between the 4th and 14th centuries A.D. and continuously maintained for nearly two millennia. The site reflects the development and evolution of Chinese history over ten dynasties [,,]. With over 45,000 square meters of mural paintings [] (p. 987). Their significance lies not only in their artistic and historical value but also in their role as a model for sustainable conservation management.

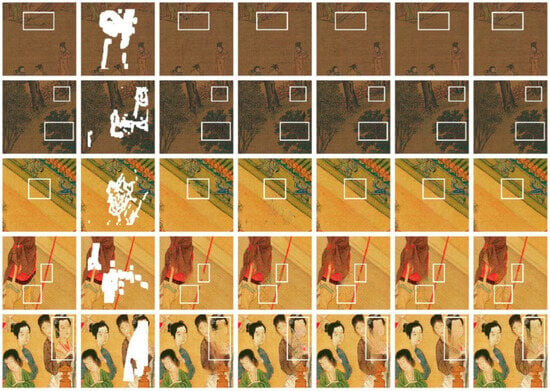

In practice, E-Dunhuang demonstrates how AI can support but not replace human expertise. One of the most significant outcomes of the E-Dunhuang project is that it uses AI-driven intelligent restoration to restore Dunhuang’s murals. As shown in Figure 1, the white frames illustrate how AI automatically performs the restoration step by step. Technologies such as multi-spectral photography, close-range photogrammetry, and image-based processing enable high-resolution documentation of murals, guiding restorers and facilitating virtual simulations before physical interventions [,]. This approach reduces restoration risks, optimizes resource use, and ensures the long-term preservation of fragile artefacts, aligning with sustainable conservation practices.

Figure 1.

AI usage in Dunhuang restoration.

However, just relying on AI technology cannot make E-Dunhuang the most representative digital heritage project around the world. One principle of the Dunhuang Research Institution is that all the restoration outcomes must be checked by professional repairers, archaeologists, historians, and painters. This is because cultural heritage embodies philosophical reflection and emotional expression unique to the human experience, whereas most of the knowledge currently learned by AI is structured, measurable, and generalizable to processing data. Therefore, AI that provides intelligent restoration cannot fully capture or reproduce the nuanced, humanistic expressions embedded within cultural artifacts, which leaves the risk that restored heritage may lack the authenticity and emotional resonance of the original [] (p. 36). As a result, heritage professionals must remain central in decisions requiring contextual judgment. AI should be recognized as a decision-support tool rather than a substitute for professional judgment [] (p. 13). AI models can identify patterns of deterioration in artefacts, but the final decisions regarding conservation strategies must remain in the hands of heritage professionals. This collaborative approach safeguards both cultural sustainability by preserving meaning and social sustainability by ensuring human responsibility and accountability. This collaborative approach also contributes to intergenerational equity, as heritage is transmitted faithfully without losing its historical depth and richness.

The project also illustrates the importance of sustainable digital infrastructure and knowledge management. Through 3D modelling and image-based rendering, detailed databases of murals and sculptures are created, securing heritage against physical degradation while providing long-term, sustainable access for research and education [] (p. 3). These technologies enhance the efficiency of data management and broaden public engagement, offering immersive experiences that stimulate sustainable cultural tourism and economic development [] (pp. 4–6). For instance, interactive online platforms allow audiences to engage with murals virtually, stimulating heritage tourism, personalized cultural products, and multi-industry cooperation that supports economic growth and cultural transmission [] (pp. 4–7, 11–12). These practices align with Guideline 5, which emphasizes the importance of continuous updates, maintenance, and long-term accessibility of AI systems to ensure sustained cultural engagement.

The sustainable practices of Digital Dunhuang have yielded remarkable results. At the 34th Session of the World Heritage Committee in Brazil in 2010, the sustainable conservation management practices implemented at the Dunhuang and Mogao Caves were presented as exemplary models for other World Heritage sites [] (p. 7). It not only possesses sustainable conservation measures with clearly defined technical and cultural boundaries, but also promotes global dissemination and positive cultural and social sustainable development. With the digital heritage library overcoming the geographical obstacle, it has opened new avenues for cultural dissemination both within China and abroad [] (p. 11), meeting the public’s growing interest in cultural consumption. Therefore, the use of AI in cultural heritage also stimulates the development of education, tourism, and cultural industries, such as offering customized cultural products, allowing personalized interactions with digital heritage products, and fostering sustainable social engagement with culture [] (p. 7). This multi-industry cooperation promotes sustainable economic growth and increases funding for preservation efforts through donations and cultural consumption, thereby fostering the preservation and inheritance of sustainable cultural heritage [] (p. 12).

However, though with great success, this does not mean that the E-Dunhuang project does not have any limitations. While digital technologies have increased the storage and distribution of cultural heritage, they have also introduced the issue of copyright infringement. The ease with which digital content can be replicated, shared, and modified raises the potential for unauthorized use and piracy [] (p. 13). Currently, E-Dunhuang does not have any solution related to Guideline 4: Establishing Robust Copyright and Rights Management, making this an urgent and pressing challenge for the project’s sustainable development. The Dunhuang Research Institution should adopt several specific measures. First, the platform could establish a tiered access system: while low-resolution mural images remain freely accessible for public education, high-resolution versions should only be available through registration and formal research agreements. This would preserve open access for cultural dissemination while protecting sensitive materials from misuse. Second, all downloadable content could be embedded with digital watermarks and blockchain-based traceability codes, ensuring that any unauthorised reproduction of Dunhuang murals can be tracked and legally pursued. Third, the project could establish a commercial licensing mechanism for the cultural and creative industries. For instance, when companies use mural motifs for souvenirs, games, or films, they must obtain an official license from the Dunhuang Academy, with the revenue shared to fund future conservation efforts. Fourth, to manage international dissemination, the project could develop cross-border copyright agreements with major global cultural platforms, ensuring that E-Dunhuang data cannot be redistributed without explicit consent. Finally, a community-supervised review board, involving heritage custodians, legal experts, and local cultural representatives, could be established to evaluate requests for data use, striking a balance between accessibility and cultural and legal safeguards.

Overall, the E-Dunhuang project illustrates how multiple guidelines can be effectively applied in practice to advance cultural sustainability. Guideline 2: AI as a complementary tool ensures that intelligent restoration enhances accuracy and efficiency without displacing human expertise, protecting the authenticity and integrity of the murals. Guideline 5: long-term maintenance and data management secures durable digital archives, enabling continuous monitoring and intergenerational knowledge transfer. The project also highlights the urgent need to implement Guideline 4: robust copyright and rights management to safeguard intellectual property and ensure that cultural content is used ethically. Together, these strategies not only strengthen the resilience of Dunhuang’s heritage but also create new opportunities for heritage tourism. By combining authenticity, accessibility, and sustainable governance, the project supports the development of immersive cultural experiences, licensed cultural products, and educational tourism. In this way, E-Dunhuang demonstrates how digital heritage initiatives can simultaneously protect fragile cultural resources and stimulate sustainable cultural tourism, linking preservation with broader social and economic benefits.

4.2. The Old Summer Palace (Yuanmingyuan)

The sustainable development of the Yuanmingyuan (Old Summer Palace) Project centers on virtual reconstruction and digital interpretation, directly reflecting the challenges and opportunities of Guideline 1: ensuring cultural authenticity through inclusive data practices and Guideline 3: balancing innovation with the preservation of cultural values.

The Old Summer Palace, also known as Yuanmingyuan in Chinese, was constructed in the 17th century during the Qing dynasty. Spanning 3.2 square kilometers, it encompassed 650 buildings and 130 distinct landscape scenes, integrating various styles of Chinese and Western architecture that represented the full range of construction techniques, materials, and cultural treasures available at the time, with a seamless fusion of architecture and garden landscapes [,]. Although largely destroyed in 1860, digital technologies enable the sustainable virtual reconstruction of the site, allowing for heritage tourism, long-term access, and educational use [,].

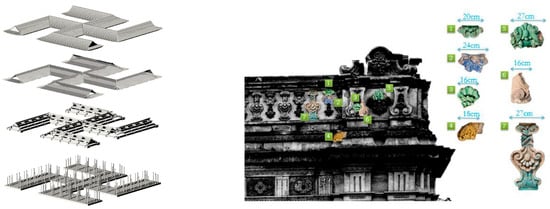

The main task of Yuanmingyuan is reconstruction, as the entire palace was destroyed. The reconstruction process demonstrates the application of Guideline 1, which involves ensuring cultural authenticity through inclusive data practices. To ensure the authenticity and accuracy of the Yuanmingyuan virtual reconstruction, the process combines on-site recording data, historical documents, and three-dimensional models. The initial data collection phase employs both traditional and digital methods, including four technologies: aerial photography, laser scanning, total station, and manual recording [] (pp. 76–77). Once these digital tools gather precise data from the ruins, the information is cross-referenced with historical documents, such as architectural plans, textual descriptions, and paintings, to determine the exact placement and structure of the original buildings [] (p. 1184). After data compilation, 3D modelling software and machine learning algorithms are used to automate the reconstruction process (see Figure 2). The system will automatically restore the buildings of Yuanmingyuan based on the imported data [] (p. 5). Through data from multiple sources and literature, the virtual reconstruction of the Old Summer Palace has maximally ensured its authenticity [,]. By employing multifaceted investigation and cross-comparison as primary methods, this project ensures that the restored Yuanmingyuan can replicate its original appearance as closely as possible. These digital tools offer powerful opportunities for sustainability: they prevent further degradation of the remaining ruins, provide visual access to a site that no longer exists in physical form, and allow researchers to experiment with hypotheses in non-invasive ways.

Figure 2.

Three-dimensional modelling and machine-learning reconstruction of Yuanmingyuan.

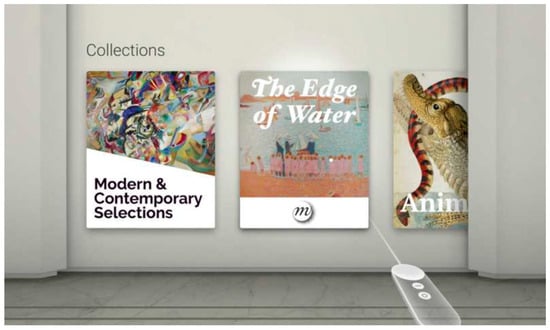

After the virtual reconstruction is complete, the rebuilding is presented to the public through virtual exhibitions. These exhibitions employ signage and digital technologies to convey the cultural significance of the site. Sign-based displays use designed vegetation, pathways, and structures to outline the layout and contours of the original palace, while digital exhibitions leverage computer-generated visualizations to reconstruct the site’s history. Through mobile devices, visitors can access real-time rendered images of the restored Yuanmingyuan, allowing them to experience the palace virtually, which is shown in Figure 3 [] (p. 354). This significantly enhances the entertainment and enriches the experience of heritage tourism. “Digital Yuanmingyuan” is the world’s first mega IP (Intellectual Property) based on cultural heritage research, which builds a marketing chain of research, creation, tourism, and industry. It enabled sustainable development in both culture, tourism industry, and the economy [] (pp. 337–338).

Figure 3.

Virtual Heritage Tourism Experience.

However, the Digital Yuanmingyuan project does not align with Guideline 3: balancing innovation with the preservation of cultural values. Digital restoration risks fostering self-absorbed ostentatiousness. Authentic heritage sites carry historical depth and cultural continuity through their physical presence, but virtual reconstructions, isolated from tangible remains, may fail to convey the emotional and educational significance of the original site. For non-expert audiences, virtual recreations of cultural heritage lack a full display of human warmth and contextual richness. They cannot accurately convey the educational and appreciation value that cultural heritage brings to people [] (p. 337). In addition, as one of China’s most significant heritage tourism attractions, the excessive commercialization of the Old Summer Palace risks prioritizing visitor numbers and revenue generation over the authenticity of cultural meaning. This is particularly problematic for a heritage site that is now entirely dependent on digital reconstruction: if virtualization is reduced to a tool of entertainment or spectacle, it may distort collective memory and weaken public respect for the site’s tragic historical context. To mitigate these risks, the Digital Yuanmingyuan project must embed cultural values at the center of its innovation strategy. By aligning digital innovation with cultural meaning, Yuanmingyuan could transform heritage tourism into a reflective and educational journey rather than a purely commercial attraction. In this way, the project would not only preserve the site’s symbolic integrity but also demonstrate how sustainably managed digital tourism can enhance cultural appreciation, intergenerational learning, and global dialogue on the importance of safeguarding heritage.

4.3. Google Arts & Culture

The sustainable development of Google Arts & Culture highlights Guideline 5: long-term technical maintenance. Since its launch in 2011, Google has continually collaborated with museums to enrich its cultural database, ensuring data updates and long-term maintenance, thereby providing users with the most up-to-date and comprehensive digital cultural heritage experience. Google Arts & Culture has offered a globally accessible and sustainable platform for cultural engagement. Hosting over six million digitized objects from more than 1200 museums and demonstrating high-resolution artwork images, and personalized collections [,]. It democratizes access to cultural heritage and stimulates the development of virtual heritage tourism, bridging geographical and socioeconomic gaps [,].

Google Arts & Culture offers easy and sustainable access to artworks from around the world, thereby eliminating geographical boundaries to cultural appreciation and facilitating heritage tourism through long-term engagement [] (p. 182). Whereas traditional museum visits are often limited to wealthier and highly educated groups due to financial and time constraints, the platform democratizes cultural participation, reducing inequalities and promoting social sustainability and digital heritage tourism by allowing anyone with a digital device to explore art collections [] (p. 114). Second, by introducing virtual reality experiences (see Figure 4), the platform offers an innovative and interactive mode of engagement, attracting younger, technology-oriented audiences and ensuring the sustainable transmission of cultural knowledge to future generations. Third, it complements traditional museum visits: online access often increases public interest in offline experiences, while high-definition images enhance understanding even during physical visits by compensating for viewing limitations [] (p. 182). Ultimately, Google Arts & Culture plays a direct role in promoting the sustainability of art and culture by overcoming geographic obstacles in heritage tourism, fostering education, and raising awareness. Its high educational value enriches teaching methods, raises public consciousness about cultural heritage protection, and strengthens intergenerational knowledge transfer [] (p. 15). Through these functions, the platform not only enriches the heritage tourism approach and expands cultural accessibility but also reinforces the long-term sustainability of cultural heritage preservation and engagement.

Figure 4.

Functions of Google Arts & Culture.

However, Google Arts & Culture falls short of fully implementing Guideline 4: robust copyright and rights management and Guideline 6: ethical governance and inclusivity in global dissemination. The platform’s limited representation of modern and contemporary artworks reflects issues of copyright and piracy, as many artists remain reluctant to share high-resolution images online due to risks of unauthorized commercial use. Similarly, some cultural relics cannot be exhibited due to unclear ownership, which restricts the sustainable expansion of the platform’s cultural inclusivity. In addition, the collections on Google Arts & Culture reflect the historical dominance of Western cultural institutions, as they often approach art through Western aesthetic frameworks. Notably, 82% of the digitized objects on the platform originate from the United States, highlighting the unequal representation of the global cultural heritage [] (pp. 1–2). Such an imbalance undermines cultural diversity and inclusivity, both of which are essential to the sustainable development of global cultural heritage platforms. Addressing these limitations is therefore crucial for ensuring that digital heritage initiatives contribute to long-term cultural equity, accessibility, and preservation. Addressing these limitations requires integrating inclusive governance frameworks and transparent rights management systems. By negotiating fair-use licenses with contemporary artists, diversifying partnerships with underrepresented institutions, and adopting global ethical standards for cultural dissemination, Google Arts & Culture could evolve into a more equitable and sustainable model. Such improvements would not only expand the cultural scope of the platform but also enhance its role in supporting heritage tourism, enabling users worldwide to engage with diverse cultural resources online and inspiring reflective and responsible physical visits.

Overall, Google Arts & Culture showcases both the opportunities and the risks of leveraging AI and digital technologies in cultural heritage. When supported by robust copyright protections, transparent governance, and commitments to inclusive representation, the platform has the potential to become a sustainable model for global cultural dissemination. For heritage tourism, Google Arts & Culture expands opportunities by offering immersive previews of museums and heritage sites, sparking interest in physical visits while also providing accessible alternatives for those unable to travel. In this way, the platform exemplifies how digital initiatives can complement on-site heritage tourism, creating a hybrid ecosystem where cultural accessibility, economic growth, and global sustainability goals are mutually reinforcing.

5. Conclusions

This study situates the application of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in cultural heritage preservation within the framework of cultural sustainability and develops six practical guidelines to ensure its effective and responsible use. These guidelines emphasise (1) robust data governance and inclusivity to maintain authenticity and integrity; (2) the use of AI as a complementary tool rather than a replacement for human expertise; (3) balancing technological innovation with the preservation of cultural values; (4) establishing strong copyright and rights management systems; (5) securing long-term technical maintenance and resilience of digital platforms; and (6) promoting ethical governance and inclusivity in global dissemination. Collectively, these principles provide a systematic roadmap for integrating AI into sustainable heritage conservation and preservation.

To demonstrate the practical relevance of these guidelines, the paper examined three representative case studies. The Digital Dunhuang Project demonstrates how AI can enhance restoration and digital archiving, aligning with Guidelines 2 and 5, while also presenting challenges related to copyright management. The Digital Yuanmingyuan Project exemplifies Guideline 3, highlighting the risks of over-reliance on virtual reconstructions and the need to preserve cultural values in highly commercialized heritage tourism contexts. Google Arts & Culture demonstrates the potential of Guidelines 4, 5, and 6, showing how global accessibility and heritage tourism can be enhanced, while also highlighting the pressing issues of copyright, cultural bias, and inclusivity.

By combining a normative framework with case-based evidence, this study contributes to both scholarship and practice. Conceptually, it advances the integration of AI into cultural sustainability by positioning technology as a tool for resilience, authenticity, and inclusivity, rather than an end in itself. Practically, it offers policymakers, heritage institutions, and the tourism industry a set of actionable guidelines for designing AI-enabled heritage initiatives that are ethically grounded, technically sustainable, and globally inclusive.

At the same time, this study acknowledges its limitations. The analysis is based primarily on three illustrative case studies, which, while diverse in scale and scope, cannot fully capture the disciplinary and international variety of AI applications in cultural heritage. Future research could build on these findings by incorporating larger and more diverse empirical evidence. In particular, interviews and surveys with multidisciplinary professionals (e.g., architects, restorers, historians) and with members of international organizations such as UNESCO and ICOMOS would provide richer perspectives and greater representativeness. Such efforts would enhance the generalizability of the proposed guidelines and ensure that AI-enabled cultural heritage initiatives are validated across different cultural and institutional contexts.

In doing so, the paper strengthens the connection between digital innovation and the long-term safeguarding of cultural heritage, fulfilling the goals articulated in SDG 11.4 and ensuring that cultural heritage continues to thrive as a shared resource for future generations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.W. and F.L.; methodology, H.W., Y.G. and Y.Z.; software, H.W., Y.G. and Y.Z.; validation, H.W., Y.G. and Y.Z.; formal analysis, H.W., Y.G. and Y.Z.; investigation, H.W., Y.G. and Y.Z.; resources, H.W., Y.Z. and F.L.; data curation, H.W. and Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, H.W., Y.G., Y.Z. and F.L.; writing—review and editing, H.W., Y.G., Y.Z. and F.L.; visualization, H.W. and Y.G.; supervision, H.W. and F.L.; project administration, H.W. and F.L.; funding acquisition, H.W. and Y.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Georgia Tech Foundation Grant on Graduate Research, grant number 2024120701X.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data used in the study are publicly available from the sources cited in the text.

Acknowledgments

We thank participants from the 2024 Chinese Digital Humanities Annual Conference for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhou, L.; Liu, X.; Wei, W. The Emotional Foundations of Value Co-Creation in Sustainable Cultural Heritage Tourism: Insights into the Motivation–Experience–Behavior Framework. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandriester, J.; Harfst, J.; Kern, C.; Zuanni, C. Digital Transformation in the Cultural Heritage Sector and Its Impacts on Sustainable Regional Development in Peripheral Regions. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.; Sadek, A.W. Advantages and limitations of artificial intelligence. In Artificial Intelligence Applications to Critical Transportation Issues; Transportation Research Board: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 6–8. Available online: https://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/circulars/ec168.pdf#page=14 (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Waisi, M. Advantages and Disadvantages of AI-based Trading and Investing Versus Traditional Methods. Tamp. Univ. Appl. Sci. 2020, 4–5. Available online: https://www.theseus.fi/handle/10024/347449 (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Acke, L.; De Vis, K.; Verwulgen, S.; Verlinden, J. Survey and literature study to provide insights on the application of 3D technologies in objects conservation and restoration. J. Cult. Herit. 2020, 49, 272–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z. AI and Cultural Heritage Preservation in India. Int. J. Cult. Stud. Soc. Sci. 2024, 20, 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Leshkevich, T.; Motozhanets, A. Social Perception of Artificial Intelligence and Digitization of Cultural Heritage: Russian Context. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soini, K.; Birkeland, I. Exploring the scientific discourse on cultural sustainability. Geoforum 2014, 51, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adel Haddad, N. From Hand Survey to 3D Laser Scanning: A Discussion for Non-Technical Users of Heritage Documentation. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2013, 15, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoto, G. Detecting Past Attempts to Restore Two Important Works of Art. Acc. Chem. Res. 2002, 35, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanco, F. Digital Imaging for Cultural Heritage Preservation: Analysis, Restoration, and Reconstruction of Ancient Artworks; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Marchello, G.; Giovanelli, R.; Fontana, E.; Cannella, F.; Traviglia, A. Cultural heritage digital preservation through AI-driven robotics. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, 48, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D. Research on digital exhibition Old Summer Palace somatosensory interaction based on Leap Motion. In Proceedings of the 2015 2nd International Conference on Electrical, Computer Engineering and Electronics, Manila, Philippines, 12–14 February 2015; Atlantis Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 1079–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaith, K.; Hutson, J. A qualitative study on the integration of artificial intelligence in cultural heritage conservation. Metaverse 2024, 5, 2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H. The application of virtual reality technology in the digital preservation of cultural heritage. Comput. Sci. Inf. Syst. 2021, 18, 535–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Ma, Y.H.; Zhang, X.R. “Digital Heritage” Theory And Innovative Practice. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2017, XLII-2/W5, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaber, J.A.; Youssef, S.M.; Fathalla, K.M. The Role of Artificial Intelligence And Machine Learning in Preserving Cultural Heritage and Art Works via Virtual Restoration. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, X-1/W1-202, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. Guidelines Given the Latest Technological Developments, Such as AI, Complementing Council of Europe Standards in the Fields of Culture, Creativity and Cultural Heritage; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2024; Available online: https://rm.coe.int/cdcpp-2024-3-en-coe-policy-guidelines-on-ai-in-culture-creativity-heri/1680b45c67 (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2021; Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/artificial-intelligence/recommendation-ethics (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- ICOMOS. International Cultural Heritage Tourism Charter; International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS): Paris, France, 2022; Available online: https://admin.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/International-Cultural-Heritage-Tourism-Charter_EN_IT.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- UNESCO. Indigenous People—Centered AI: Perspectives from Latin America and the Caribbean; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000387814 (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Ke, C.-Q.; Feng, X.-Z.; Du, J.-K.; Tang, G.-D. 3D Information Restoration of The Digital Images of Dunhuang Mural Paintings. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2008, XXXVII, 987–991. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X. Usability Evaluation of E-Dunhuang Cultural Heritage Digital Library. Data Inf. Manag. 2018, 2, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S. New Era for Dunhuang Culture Unleashed by Digital Technology. Int. Core J. Eng. 2023, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Fang, Q.; Chen, W.; Xu, T.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z. A comprehensive dataset for digital restoration of Dunhuang murals. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J. The Application of Artificial Intelligence Technologies in Digital Humanities: Applying to Dunhuang Culture Inheritance, Development, and Innovation. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. Stud. 2022, 4, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; García, F.L.D.B. Análisis constructivo y reconstrucción digital 3D de las ruinas del Antiguo Palacio de Verano de Pekín (Yuanmingyuan): El Pabellón de la Paz Universal (Wanfanganhe). Virtual Archaeol. Rev. 2022, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Piao, W.; Guo, J. Digital restoration research and three-dimensional model construction on Xieqiqu. In Proceedings of the 25th International CIPA Symposium 2015, Taipei, Taiwan, 31 August–4 September 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, A. Discussion on Restoration Design of Landscape Site Based on 3dterrestrial Laser Scanning: A Case Study of Qiwang Hall In Summer Palace, Beijing, China. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, XLII-2/W11, 1181–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X. Discussion of impact of relics activation on protection and utilization approaches-take the old summer palace as an example. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2015, II-5/W3, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Universitas, K.; Satya, W.; Salatiga, I.; Indriyanto, K. Proceeding FLA10 Conference. 2017. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/337869455_Proceeding_FLA10_Conference_2017 (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Wani, S.A.; Ali, A.; Ganaie, S.A. The digitally preserved old-aged art, culture and artists. PSU Res. Rev. 2019, 3, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udell, M.K. The Museum of the Infinite Scroll: Assessing the Effectiveness of Google Arts and Culture as a Virtual Tool for Museum Accessibility. Master’s Thesis, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Verde, A.; Valero, J.M. Virtual museums and Google Arts & Culture: Alternatives to the face-to-face visit to experience art. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2021, 9, 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kilian, D.; Morales, A. Google Arts & Culture and Clil. Master’s Thesis, University of La Laguna, San Cristóbal de La Laguna, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Terras, M. Measuring Bias in Aggregated Digitised Content: A Case Study on Google Arts and Culture. In Proceedings of the Digital Humanities 2019, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 12 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).