Abstract

The rise of digital platforms has transformed heritage interpretation from a single official narrative to multi-stakeholder participation. This study investigates how such platforms mediate the formation of a sense of place at the Kulangsu World Heritage Site (WHS). Data were collected from official narrative texts and user-generated content (UGC) on Dianping and Ctrip, and analyzed using high-frequency word statistics and semantic network analysis. The results reveal a clear divergence between official narratives, which emphasize Outstanding Universal Value (OUV), and tourist perceptions, which focus on visual landmarks and “check-in” practices shaped by the “digital gaze.” Moreover, the sense of place is shown to be a dynamic process, co-constructed through pre-visit expectations, on-site experiences, and post-visit reflections. The findings also highlight a transformation in tourists’ roles, shifting from passive cultural consumers to active participants in the co-construction of heritage values, with digital platforms serving as critical mediators. Theoretically, the study advances digital heritage scholarship by clarifying the mechanism of the digital gaze and the dynamic nature of sense of place. Practically, it underscores the importance of integrating official narratives with UGC to strengthen OUV communication, foster broader public engagement, and support the sustainable development of WHSs.

1. Introduction

According to the World Heritage Convention, World Heritage Sites (WHSs) are exceptional, transboundary, and irreplaceable assets of “Outstanding Universal Value” (OUV), embodied in their cultural heritage and natural landscapes [1]. Existing research has demonstrated that the OUV attributed to WHSs has received broad international recognition [2,3], and that enjoying these sites entails an ethical responsibility to respect, understand, appreciate, and protect their intrinsic values [2]. OUV plays a dual institutional role: it is both the fundamental criterion for inscription on the World Heritage List and the foundational basis for heritage protection, management, and communication frameworks [3]. The identification and interpretation of heritage value not only underpin the cognitive discourse of heritage but also constitute a key issue for the sustainable conservation and appropriate utilization of cultural resources [4].

With the growing global attention to cultural heritage, tourism has emerged as a critical driver of integrated heritage conservation and socio-economic development [2,4]. In this context, WHS tourism is widely regarded as a vital mechanism for achieving the goals of heritage conservation and sustainable development [2,4,5]. Due to their unique cultural and historical significance, WHSs have increasingly become prime destinations for global tourists [5,6,7]. During the visitation experience, the OUV, reflecting the cultural significance and identity of WHSs, plays a central role in shaping tourists’ cognition, emotional attachment, and behavioral intentions [8,9]. Whether driven by historical exploration, cultural immersion, or leisure pursuits, tourists subjectively interpret OUV through their “gaze,” continually reconstructing the significance of WHSs based on personal experiences [10,11,12]. Empirical research has shown that tourists’ perception of OUV substantially shapes their experiential depth and satisfaction [13], while also exerting a pivotal influence on the development of Sense of Place (SOP) [14]. Conversely, ineffective communication of or failure to perceive OUV may diminish the cultural appeal and public recognition of WHSs, thereby threatening their tourism sustainability and long-term conservation objectives [15,16].

Sustainable tourism planning and management have become central themes in the implementation of the World Heritage Convention and are key areas within UNESCO’s World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme [1]. The International Cultural Heritage Tourism Charter [2] explicitly calls for WHSs to establish systematic, visitor-oriented interpretation and presentation mechanisms that effectively convey their cultural values, thereby enhancing cognitive engagement and experiential quality. Tourism promotion should simultaneously maintain the authenticity and integrity of heritage sites while emphasizing the expression of their cultural attributes, striking a dynamic balance between conservation and use to ensure the intergenerational transmission of heritage values. The Charter applies to all aspects of cultural heritage management, including conservation, interpretation, presentation, and communication [2]. In accordance with this framework, heritage management authorities commonly leverage guided tours, interpretive materials, and strategic outreach initiatives to systematically articulate OUV, enhance value recognition among visitors, and bolster the sustainable development of WHSs [17,18].

Amid ongoing digital transformation and technological advancement, interactions between tourists and WHSs are shifting from conventional on-site experiences to multidimensional forms of engagement, characterized by “online anticipation–on-site perception–digital feedback.” Through images, texts, and hashtags, User-Generated Content (UGC) on social media platforms allows tourists to actively construct and disseminate subjective interpretations of WHSs, giving rise to a new paradigm of tourism practice marked by a “digital gaze” [19,20]. UGC is generally perceived as more trustworthy than official promotional materials, owing to its experiential and contextual authenticity, and has become an important source of information for potential tourists forming initial impressions of heritage destinations [21,22,23].

Against this backdrop, this study examines Kulangsu, a WHS in Xiamen, China, to investigate the structural misalignment between official OUV narratives and tourists’ “digital gaze.” It further explores how the sense of place is shaped, transformed, and reconstructed within the context of multi-stakeholder interaction. The study therefore proposes two hypotheses:

- (1)

- Official narratives and digital gaze-mediated OUV interpretations exhibit significant perceptual differences;

- (2)

- The digital gaze influences the evolution of sense of place, with distinct patterns driven by identifiable factors.

In summary, the interpretation of heritage values is shifting from a unidirectional, official narrative to a dynamic model characterized by multi-stakeholder participation. In this context, tourists act as active meaning-makers who frequently develop subjective value perceptions during their experiences. These perceptions may differ from the authenticity and integrity concepts emphasized in official OUV narratives [2,3,22,24].

The structure of this paper is as follows. Section 2 provides a critical review of four key strands of literature: spatial perception and digital mediation, the conceptualization of the digital gaze, discourses surrounding OUV, and the construction of a SOP within WHSs. Section 3 outlines the case study context and details the research design and methodological approach. Section 4 presents the research findings. Section 5 discusses the results in relation to the proposed hypotheses and highlights the theoretical and practical contributions of the study. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the key conclusions and reflects on the study’s limitations.

2. Rethinking SOP Under the Digital Gaze

2.1. Spatial Perception and Digital Mediation

Spatial perception is not a mere reproduction of the physical environment but rather the integrative outcome of sensory input, memory, affect, and socio-cultural context, all operating in dynamic interaction [25,26]. In this process, individuals selectively attend to external environmental stimuli through what may be termed a “perceptual filter” [27,28]. This filtering mechanism determines which environmental features are amplified and which are disregarded, thereby exerting a profound influence on how tourists cognitively apprehend and evaluate destinations [27,28,29]. Within tourism studies, spatial perception has thus been widely regarded as the theoretical foundation for destination image formation and the generation of tourist experiences [30,31]. In the specific context of heritage tourism, the construction of destination imagery relies not only on the material presentation of space but also on tourists’ subjective interpretations, imaginative projections, and narrative reconstructions. Such dynamics underscore the socially constructed and inherently subjective nature of spatial perception [11,28].

With the proliferation of digital media and the pervasive influence of social networking platforms, the mechanisms underlying spatial perception are increasingly characterized by “digital mediation”. Online interactions subtly reshape cognitive orientations and behavioral patterns, substantially influencing how individuals perceive, interpret, and engage with their surrounding environments [32]. For tourists, destination cognition and experience are no longer confined to direct sensory encounters on-site; rather, they are progressively shaped by networked structures of dissemination and the interactive circulation of digital information [33,34,35]. Existing research demonstrates that the perceived credibility and expertise of online reviewers, alongside textual features such as descriptive richness and emotional expression, significantly enhance audiences’ assessments of review usefulness [36,37]. Such perceptions not only shape tourist decision-making but also intervene more profoundly in the construction of destination imagery [38,39]. Consequently, digital mediation does not merely alter the communicative pathways of spatial perception but fundamentally reconfigures the cognitive logic through which tourists engage with and make sense of space.

2.2. From Tourist Gaze to Digital Gaze

The act of gazing provides tourists with a cognitive framework for interpreting destinations [10]. However, the human experience of place is fundamentally multisensory, involving touch, taste, smell, and material engagement with objects and environments, rather than being limited to the symbolic interpretation of spatial cues [10]. Consequently, the tourist gaze constitutes not merely an isolated visual act but a selective and situated process of perceiving landscapes, cultures, and knowledge systems [40]. Such visual engagement not only activates immediate sensory perception but also generates affective responses and constructs meaning, thereby serving as one of the most authentic cognitive anchors within the tourism experience [11].

With social media emerging as a dominant platform for information dissemination, the traditional tourist gaze is undergoing significant transformation. Given the increasing amount of time spent daily on social media, digital spaces have evolved into critical arenas for personal expression, information consumption, and symbolic interaction [41]. Tourists now rely not only on physical presence to construct the meaning of a destination but also increasingly engage in practices of sharing sensory impressions, behavioral traces, and emotional experiences through social media platforms. This shift—from physical observation to digital interaction—has given rise to what is termed the digital gaze, a novel mode of perceiving place [42,43,44]. In the context of this study, the digital gaze refers to a set of practices occurring throughout the travel process, including image capturing, content sharing, and subjective evaluation on social media platforms. These practices not only reflect tourists’ cognitive constructions of destinations but also reveal the pathways through which meaning is produced (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Transition from Tourist Gaze to Digital Gaze (Source: Drawn by the authors).

In this context, UGC—comprising reviews, images, and short videos—has emerged as a fundamental element of contemporary tourism practices [45]. These digital traces not only document and reconstruct travel experiences but also function as structured narratives that convey aesthetic judgments and perceived destination authenticity [46,47]. UGC serves a dual role: it acts as both a conduit for personal expression and an instrument for collective memory formation, simultaneously shaping destination perceptions and guiding prospective tourists’ cognitive and behavioral choices [5,48,49,50,51,52]. Significantly, systematic examination of online reviews and shared content can offer critical insights into experiential depth while elucidating the core processes linking cognitive, affective, and behavioral dimensions [49].

2.3. Official Narratives and Tourist Perceptions of OUV

Since the adoption of the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage by UNESCO in 1972, the concept of OUV has been established as the core criterion for the inscription of WHS [53]. According to the Convention and its Operational Guidelines, a site must not only demonstrate OUV, but also fulfill requirements for authenticity and integrity, and be supported by adequate legal protections, management frameworks, and resource commitments to be inscribed on the World Heritage List and gain international recognition as a WHSs [3]. As a foundational concept in heritage practice, OUV provides both a value-oriented rationale and an institutional framework throughout the processes of nomination, conservation planning, management system development, and monitoring and evaluation [3,54,55].

Nevertheless, the institutional establishment of OUV does not necessarily imply that it can be directly perceived by visitors. Research has shown that, as the core source of attraction for WHSs [56], OUV exerts an influence that extends far beyond the boundaries of official texts. With the deepening of heritage tourism, it profoundly shapes visitors’ cognitive understanding, perceptual experiences, and emotional responses to WHSs [57]. The degree to which visitors recognize OUV directly affects their experiential value, satisfaction, and loyalty, and ultimately informs their conservation attitudes and behavioral choices [58,59]. Yet in practice, inadequate enforcement of protective mechanisms, failures or distortions in interpretation systems, cross-cultural communication barriers, and tensions between global standards and local contexts frequently weaken visitors’ perception of OUV, thereby undermining the sustainability of WHSs [57].

In the digital tourism era, the communication logic of OUV is undergoing a fundamental transformation. Destination branding has progressively shifted from traditional approaches relying on brochures and slogans to digital dissemination patterns shaped by search engine rankings and platform algorithmic recommendations [60]. The visibility of information is increasingly conditioned by platform mechanisms, which determine the narratives about heritage sites that visitors first encounter and thus shape their initial impressions and interests [61,62]. In this process, the OUV narratives that reach visitors are often reproductions co-constructed through algorithmic filtering and UGC, which may diverge from the “universal values” articulated in official texts [63,64]. In other words, OUV is not merely a normative concept within an institutional framework, but also a dynamic process continuously reconstructed through both the tourist gaze and the digital gaze.

2.4. Theoretical Applications of SOP in WHSs

As a key theoretical framework for understanding the dynamic relationship between people and place [11,65,66,67], SOP emphasizes the subjective meanings and emotional attachments that individuals or groups develop through sustained interaction with specific geographical spaces. SOP generally comprises two interrelated dimensions: cognitive and affective [65,68,69]. Cognitively, individuals construct place perceptions through spatial experiences, recognizing both the material attributes and cultural symbols of a location [57,65]; affectively, SOP reflects individuals’ dependence on, identification with, and sense of belonging to a place, ultimately informing behavioral preferences and value judgments [11,70,71,72].

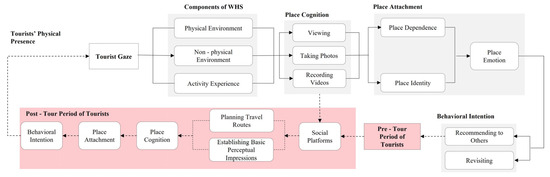

In recent years, researchers have developed structural models of SOP (see Figure 2) to illustrate the causal chain linking place cognition, place attachment, and behavioral intention within WHSs [22,72,73,74,75,76]. Specifically, tourists’ place cognition is shaped by both the tangible attributes of WHSs—such as historic architecture, street morphology, and natural landscapes—and intangible dimensions, including cultural memory, everyday atmosphere, and commercial vibrancy [11]. Meanwhile, participatory experiences such as sightseeing, photography, location check-ins, and culinary exploration represent tourists’ modes of engagement [22,77]. Together, these cognitive and experiential elements collectively foster the formation of place attachment.

Figure 2.

Structural Model of SOP in WHS (Source: Drawn by the authors based on Reference [11]).

As the central construct within SOP research, place attachment encompasses both place identity and place affect [77,78]. It not only influences tourists’ levels of satisfaction and loyalty but also exerts a significant impact on their behavioral intentions, such as willingness to revisit and likelihood of recommending the destination to others. Ultimately, these processes contribute to the construction of destination image and support the sustainable development of heritage tourism [11].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Case of Kulangsu

Kulangsu is a 1.88 km2 island located off the coast of Xiamen in Fujian Province, southeastern China [79]. Following Xiamen’s designation as a treaty port in 1843—and particularly after the establishment of the Kulangsu International Settlement in 1903—the island developed into a significant hub for China’s international engagement and a unique crossroads of diverse cultures during the modern era [80]. A Chinese-Western community characterized by diverse architectural and urban environments gradually emerged from this historical trajectory. Kulangsu’s architectural landscape integrates Southeast Asian and European influences, including southern Fujian vernacular, Western classical revival, and corridor-style colonial designs. A notable manifestation of this stylistic fusion is the Amoy Deco style [80].

Designated as a National Scenic Area by China’s State Council in 1988, Kulangsu was inscribed on the World Heritage List in 2017 under the title “Kulangsu, a Historic International Settlement” [79]. According to the Nomination Dossier, the site comprises 51 representative historic buildings, four major historic road networks, seven distinct natural landscapes, and two cultural heritage sites—all of which contribute to its OUV (see Figure 3) [80].

Figure 3.

Location of Kulangsu and Distribution of WHSs (Source: Drawn by the authors based on Reference [80]).

The outbreak of COVID-19 had a profound impact on Kulangsu, marking the beginning of three distinct phases in its development: the Initial Exploration Phase following its inscription (2017–2019), the Stagnation Phase during the pandemic (2020–2022), and the Comprehensive Deepening Phase from 2023 onwards. The spatial boundaries and overall extent of the site remain consistent with those documented in its official nomination materials [80].

3.2. Methodology

3.2.1. Research Design

This study adopts content analysis as the core methodological approach, integrating two analytical dimensions—“official narratives” and “UGC”—to conduct a systematic and quantitative investigation. The objective is to reveal the official logic underlying the definition of the OUV of Kulangsu, while simultaneously comparing tourists’ “place cognition,” “place attachment,” and “behavioral intention” in the context of digital media. In doing so, the study explores the multidimensional mechanisms of heritage value construction (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Research Framework (Source: Drawn by the authors).

3.2.2. Data Collection

The data sources of this study comprise two dimensions: official narratives and the digital gaze.

Within the dimension of official narratives, the analysis centers on the definition and justification of OUV during the nomination of Kulangsu for UNESCO WHS inscription. Guided by the research objectives, two authoritative and representative sources were selected: (1) the Kulangsu WHS Nomination Dossier; and (2) the statements of OUV, assessments of criteria compliance, and explanations of authenticity and integrity published on the official website of the UNESCO World Heritage Centre. These sources systematically reflect the official positioning and interpretation of Kulangsu’s heritage value. By contrast, promotional materials produced by local governments or tourism agencies (e.g., brochures, marketing booklets, and official tourism websites), while valuable for communication, primarily serve marketing or commercial purposes and were therefore excluded from this analysis.

The dimension of the digital gaze was operationalized by extracting UGC from two major Chinese online platforms: Dianping.com and Ctrip.com. Dianping, one of China’s earliest lifestyle service review platforms, has exerted strong influence in the tourism sector owing to its extensive user base, frequent data updates, and integration of geolocation and rating systems [81,82]. Its consumer reviews and travel-related evaluations provide reliable insights into visitors’ perceptions and experiences. Complementarily, Ctrip, China’s largest online travel booking and review platform, offers abundant records of authentic tourist experiences, thereby enhancing both the representativeness and diversity of the dataset [83]. The combination of these platforms thus provides a comprehensive and complementary perspective for analyzing tourists’ perceptions and experiences of Kulangsu in the digital space.

The dataset was collected from publicly accessible review content on Dianping (www.dianping.com) and Ctrip (www.ctrip.com). The collection period spans 1 January 2017, to 5 June 2025, a timeframe deliberately chosen because 2017 marked Kulangsu’s inscription as a UNESCO WHS—a milestone that profoundly influenced public attention and tourist experiences. Retrieval was limited to review texts containing the keywords “Kulangsu” or “Kulangsu WHS”. The extracted dataset included core fields such as username, review date, and review content. A total of 31,768 raw records were collected—28,769 from Dianping and 2999 from Ctrip. After rigorous data cleaning, including the removal of empty, duplicate, or irrelevant entries, 31,194 valid reviews were retained for subsequent analysis.

3.2.3. Data Cleaning

To ensure data standardization and the reliability of analytical outcomes, this study employed a systematic data-cleaning process using Python 3.11. The procedure comprised the following steps: (1) removing duplicate records, advertisements, and comments that were excessively brief or substantively empty; (2) standardizing common spelling variations (e.g., unifying “古浪屿” into the standardized form “鼓浪屿” for Kulangsu); (3) consolidating synonymous terms (e.g., unifying “street,” “alley,” and “pathway” under the standardized category “road”); and (4) converting the cleaned texts into *.txt format to facilitate subsequent computational analysis.

To validate the accuracy of the cleaning process, the research team conducted manual checks on a randomly selected subset of comments. The results demonstrated a high degree of consistency between manual verification and automated cleaning, confirming the validity of the procedure. Nevertheless, due to the substantial human resources required, a line-by-line manual verification of all comments was not feasible. This limitation will be further discussed in the Section 6.

3.2.4. Data Analysis

Following data cleaning, the textual dataset was imported into the content mining software ROST CM6 for high-frequency word analysis and semantic network analysis.

First, during the word frequency analysis stage, a self-constructed lexicon was applied to standardize the corpus by removing stop words, redundant expressions, and ensuring lexical consistency. To enhance robustness, the minimum word length was set to two Chinese characters, and words with fewer than ten occurrences were excluded. Based on this process, a frequency table was generated, and the top 30 keywords were extracted. These high-frequency words represent the core focal points and cognitive patterns of tourists, which were further classified into three overarching categories: place cognition, place attachment, and behavioral intention.

Second, during the semantic network analysis stage, ROST CM6 was used to extract co-occurrence relationships among high-frequency words, thereby generating a word–word co-occurrence matrix. This matrix was imported into Gephi 0.10.1 for network modeling and visualization. The semantic network was constructed as an undirected weighted graph and visualized using the ForceAtlas2 layout algorithm. To reveal structural characteristics, network indicators—including degree centrality, betweenness centrality, and modularity—were calculated, allowing the identification of core nodes and semantic clusters. In the visualization, node size was proportional to degree centrality (keyword importance), node color corresponded to modularity class (semantic clusters), and edge thickness indicated co-occurrence frequency (connection strength).

3.2.5. Research Ethics

This study strictly adhered to established research ethics standards. Only data fields directly relevant to the research objectives—such as review text, posting date, and rating—were collected. No personally identifiable information was retrieved or stored at any stage. All data were used exclusively for academic purposes. Results are presented in aggregated statistical forms or through semantic network visualizations, without disclosing complete original comments. This approach ensures the legality, compliance, and ethical integrity of data use.

4. Results

4.1. Exploring the Official OUV Narrative

4.1.1. High-Frequency Word Analysis of Official Discourse

Analysis of the top 30 high-frequency terms in official narrative texts reveals that the theme of OUV is articulated predominantly through two conceptual dimensions: place cognition and place identity. These dimensions are further delineated into five thematic aspects: architectural characteristics, regional context, public facilities, social identities, and historical-cultural elements (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Top 30 High-Frequency Words in the Official Narrative.

Place cognition comprises three principal components: architectural features, spatial configurations, and public institutions.

First, at the architectural level, high-frequency terms highlight the diversity of Kulangsu’s architectural heritage and its distinctive fusion of Chinese and Western traditions. As a regional cultural form, overseas Chinese culture embodies the intersection of Western influences and local traditions [84], characterized by the juxtaposition of transcultural features and regional particularities [85]. The architectural lexicon not only reflects stylistic and functional heterogeneity (e.g., “Western classical,” “Art Deco,” “veranda style”), but also conveys regionalized and cross-cultural characteristics (e.g., “Amoy Deco style,” “overseas Chinese mansions”). These terms underscore the central role of architectural imagery in constructing place identity [86]. At the same time, words such as “former site” and “remains” emphasize the cultural value of architecture as a carrier of historical memory. References to institutions such as the “Municipal Council” and “Consulate” represent both the material legacies of colonial governance and the spatial projection of modern international power relations. In addition, “overseas Chinese mansions” illustrate the hybrid architectural styles formed through the return of overseas Chinese from Southeast Asia, underscoring Kulangsu’s unique role in Sino-foreign interactions. Taken together, these high-frequency terms depict Kulangsu’s abundant and stylistically diverse architectural landscape, which justifies its designation as a “Museum of World Architecture” [87].

Second, spatial nomenclature delineates Kulangsu’s multi-scalar geographical characteristics. At the micro-level, terms including “community” and “Yanzaijiao” denote everyday spatial organizations, whereas “Sunlight Rock” constitutes a paradigmatic natural landmark with substantial symbolic import. References to intermediate-scale terms such as “Southern Fujian” and “seaside” position the island within broader cultural-geographical frameworks, demonstrating its unique regional characteristics. At the macro-scale, the reference to “Southeast Asia” reveals the island’s role as both a settlement for overseas Chinese and a node within transnational networks, underscoring its centrality in diasporic cultural and social linkages [84].

Regarding public infrastructure, historically significant buildings such as the “Municipal Council” and “Consulate” demonstrate Kulangsu’s administrative and diplomatic functions during the colonial era. Common terms including “road,” “hospital,” “school,” and “education” indicate the progression of basic urban services. Together, these elements represent the core infrastructure that supported Kulangsu’s development as a modern residential area.

Place identity is expressed through two interconnected aspects: social identity and cultural-historical continuity. From the perspective of social identity, repeated mentions of terms such as “Chinese diaspora,” “Overseas Chinese,” and “foreigners” emphasize the multicultural nature of Kulangsu’s society, demonstrating its historical role as an international community. Regarding cultural and historical characteristics, expressions including “craftsmanship,” “tradition,” “exchange,” and “dissemination” together illustrate Kulangsu’s dual role as both a center for preserving cultural heritage and a hub for cross-cultural engagement during the modern period. Diaspora culture, while originating from the lived experiences of overseas Chinese abroad, was re-integrated with local traditions upon their return, producing a hybrid cultural form that is simultaneously local and transnational. This transcultural synthesis has become a vital component of Kulangsu’s pluralistic cultural identity [87,88,89].

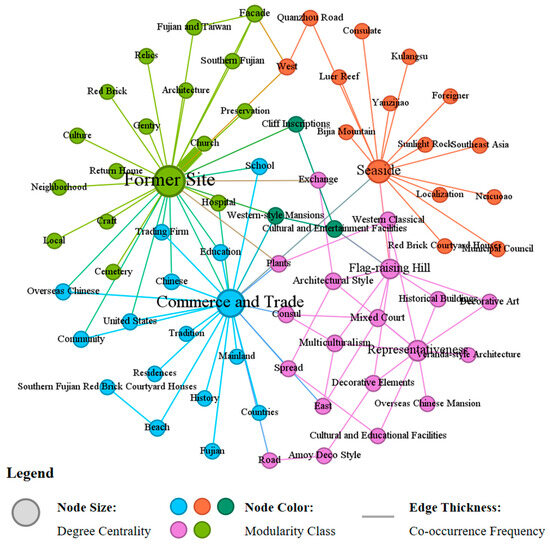

4.1.2. Semantic Network Mapping of Institutional Heritage Values

The semantic network analysis of official discourse demonstrates a polycentric and stratified framework in the characterization of Kulangsu’s heritage values (see Figure 5). Core nodes comprise “former site” and “commerce and trade,” whereas secondary clusters, including “seaside” and “representativeness,” exhibit differentiated thematic trajectories.

Figure 5.

Semantic Network Diagram in the Official Narrative (Source: Drawn by the authors).

The terms “former site” and “commerce and trade” demonstrate substantial semantic convergence. Specifically, the node “former site” displays strong associations with terms including “Southern Fujian,” “local,” and “overseas Chinese,” highlighting its critical function in analyzing ethnic integration and the conservation of indigenous cultural heritage within multicultural exchange contexts. Meanwhile, “commerce and trade” is associated with “Fujian,” “overseas Chinese,” “history,” and “community,” highlighting Kulangsu’s historical importance within the Fujianese diaspora’s transnational commercial networks. Furthermore, the coexistence of these two nodes suggests that Kulangsu operated not only as a critical nexus of intercultural contact but also as a model of globally influenced urban planning—qualities critical to its identification as a site of OUV. It is therefore evident that the heritage of overseas Chinese communities embodies both unique material-spatial values and profound cultural meanings, endowing Kulangsu with deeper symbolic significance [89].

In contrast, the secondary nodes “seaside” and “representativeness” show limited semantic interconnection yet distinct thematic implications. Connected to “Southeast Asia,” “Sunlight Rock,” and “red-brick courtyard houses,” the term “seaside” emphasizes the island’s maritime significance throughout its history. Because of its proximity to “Southeast Asia,” the island is strategically important to the Nanyang Chinese migratory pathways. “Sunlight Rock” and traditional “Southern Fujian Red Brick Courtyard Houses” exemplify a cultural landscape characterized by profound interdependencies between natural and constructed settings, hence sustaining the island’s legacy of plurality.

Conversely, the node “representativeness” displays strong associations with “Flag-raising Hill,” “Art Deco,” “architectural style,” and “overseas Chinese mansion,” highlighting stylistic transformation and architectural hybridity within the island’s modern urban fabric. “Art Deco” and “overseas Chinese mansion” embody the synthesis of Eastern and Western architectural paradigms, from which the Amoy Deco style emerged as a distinctive manifestation of Kulangsu’s architectural evolution. This integrative trajectory reflects not only the island’s outstanding value in terms of architecture and landscape but also the modern architectural practices of Minnan overseas Chinese who, under Western influence, built structures combining foreign stylistic features with local traditions [90]. Collectively, these elements reveal an important dimension of the development of modern Chinese architecture and the localization of foreign architectural traditions [91].

4.2. Tracing the Evolution of SOP in Kulangsu Under the Digital Gaze

4.2.1. Lexical Analysis of Place Cognition, Place Attachment, and Behavioral Intentions

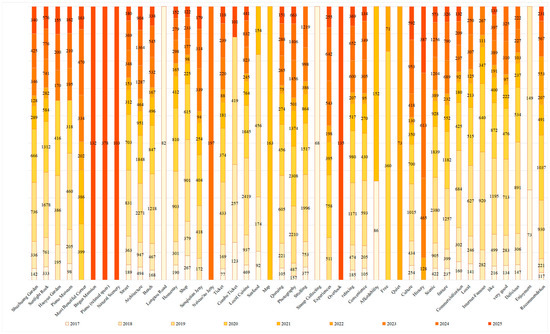

This study classifies the top 30 high-frequency words (excluding “Kulangsu”) into three thematic dimensions—place cognition, place attachment, and behavioral intentions—to investigate the dynamic characteristics of core elements constituting the SOP across temporal scales. The analysis reveals that 19 high-frequency terms remained consistent throughout the nine-year study duration, whereas nine additional terms appeared for at least six consecutive years. These 28 terms demonstrate a comparatively stable and mature SOP framework. Concurrently, the introduction of new high-frequency expressions during distinct phases implies progressive shifts in tourist perceptions. Consequently, Kulangsu’s SOP exhibits both structural permanence and adaptive progression. The annual distribution of high-frequency terms is illustrated in Figure 6, whereas Table 2 provides a detailed breakdown of their occurrence patterns, including initial appearances, sustained presence across multiple years, and terms that did not appear during the study period.

Figure 6.

Frequency of High-Frequency Terms in the Digital Gaze (Source: Drawn by the authors).

Table 2.

Occurrence Patterns of High-Frequency Terms in the Digital Gaze (2017–2025).

- (1)

- A Structurally Stable Sense of Place

The analysis of high-frequency terms associated with place perception reveals a structurally coherent framework that shapes visitors’ cognitive engagement with the heritage site. References to landmarks such as “Sunlight Rock,” “Shuzhuang Garden,” “Piano Museum,” and “ticket” indicate that core heritage elements dominate tourist recognition. The repeated appearance of “most beautiful corner”—a streetscape popularized via online platforms—further underscores the role of social media in framing spatial perception. “Sanqiutian Jetty” emerges as a critical access point, highlighting its function as a principal entryway for visitors. In parallel, terms like “street,” “architecture,” and “seaside” are closely linked to spatial morphology, built environment, and natural features, reflecting an integrated environmental perception. Additionally, commercial-related terms such as “homestay,” “shop,” and “seafood” underscore the importance of consumption-oriented spaces in shaping the tourist experience.

Regarding activity-based experience, terms like “stroll” and “experience” represent common sightseeing practices, whereas “queuing” signals high visitor density at popular locations. The prevalence of “photography” highlights the prominence of visual-centric behaviors, indirectly revealing the shaping influence of social media on tourist conduct.

In the domain of place attachment, the term “convenient” signifies tourists’ acknowledgment of accessibility and functionality, whereas “commercialization” denotes perceptions of Kulangsu’s well-developed tourism infrastructure. Expressions including “scenic,” “feature,” “culture,” and “local” pertain to the island’s historical heritage and aesthetic landscape, implying a favorable value-oriented identification with the destination. At the affective level, descriptors such as “relaxing,” “delicious,” “like,” and “very good” demonstrate positive emotional responses, indicating robust emotional connections with the locale.

Within the realm of behavioral intentions, the frequent utilization of the term “recommend” signifies how digital perspectives enhance place identification and emotional ties between visitors and the Kulangsu WHS. This also suggests tourists’ readiness to discuss and advocate for the site’s heritage assets, reflecting a proactive approach to cultural transmission.

- (2)

- Signs of Dynamic SOP Transformation Over Time

At the cognitive level of place perception, the emergence of the high-frequency term “combo ticket” in 2017 demonstrates that the “Five-Site Joint Admission Ticket” exerted a substantial influence in shaping tourists’ initial comprehension of Kulangsu’s cultural landscape. This ticket encompassed access to Sunlight Rock Scenic Area (incorporating Sunlight Rock and Qin Garden), Shuzhuang Garden (housing the Piano Museum), Haoyue Garden, Bagua Mansion (Organ Museum), and the International Engraving Art Museum—collectively establishing a preliminary cognitive framework for heritage engagement. The recurrent emergence of “Longtou Road” substantiates its pivotal function as a commercial thoroughfare in tourists’ spatial cognition, whereas the prevalent reference to “seafood” demonstrates a pronounced inclination toward regional gastronomic customs.

By 2018, “Sanqiutian Jetty” had evolved into a distinct cognitive focal point. The proximate historic edifices and cultural artifacts substantially enhanced visitors’ cultural cognizance. The persistent prevalence of “Haoyue Garden” corroborated its emblematic standing as a principal landmark attraction. In 2024, the advent of “Neicuo’ao Jetty” denoted a perceptual transition toward the island’s northwestern quadrant, effectively incorporating zones including Meihua Seaside and contiguous residential districts into the tourist purview. By 2025, the amplified prevalence of references to “piano” and “Bagua Mansion” demonstrated expanding sophistication in tourists’ cultural heritage discernment.

Regarding activity-based experiences, tourist spatial behaviors transitioned from passive involvement to more self-directed exploration. The introduction of the term “stamp collecting” in 2017 mirrored government-initiated tourism initiatives, whereas the 2025 appearance of “overlook” implied a growing predilection for autonomous, immersive environmental encounters—signifying a paradigm shift from structured, organized engagements to individualized, intrinsically motivated participation forms.

Within the domain of place attachment, the emergence of terms such as “affordable” (2017) and “free” (2020) demonstrates the significance of tourism-related financial factors in establishing preliminary emotional connections. The expression “internet-famous” (2018) exemplifies the impact of digital media platforms on tourist decision-making mechanisms. By 2022, the co-occurrence of “quiet” and “history” indicates a pronounced preference for tranquil environments and culturally enriching experiences. The emergence of “natural landscape” in 2025 reflects a growing tourist emphasis on natural environment factors. In terms of emotional expression, the term “enjoyable” (2017) constituted the sole significant affective indicator, implying predominantly positive experiential evaluations during that temporal period.

It is noteworthy that within the dimension of behavioral intentions, no newly emerging high-frequency terms were identified. This suggests that, although tourists’ cognitive frameworks continued to expand, activity patterns became increasingly diverse and autonomous, and place attachment was progressively reinforced through digital engagement, explicit expressions of revisit intention remained absent from high-frequency lexical patterns.

4.2.2. Temporal Analysis of the Interrelations Among SOP Dimensions

- (1)

- Initial Exploration Phase Following World Heritage Inscription (2017–2019)

2017–2019 represents a critical developmental stage in the formation of place attachment among tourists subsequent to Kulangsu’s inscription as a UNESCO WHS (see Figure 7). The 2017 semantic network analysis unveils a sophisticated interconnected structure, with particularly noteworthy nodes comprising “Sanqiutian Jetty,” “Longtou Road,” “Piano Museum,” and “interesting.” These findings indicate that tourists’ spatial awareness during the nascent post-inscription phase was principally anchored in transit nodes, commercial corridors, and cultural landmarks while simultaneously demonstrating a predominantly favorable affective connection, as reflected in the descriptor “interesting”.

Figure 7.

(a) Semantic Network Diagram in the 2017 Digital Gaze; (b) Semantic Network Diagram in the 2018 Digital Gaze; (c) Semantic Network Diagram in the 2019 Digital Gaze.

Notably, the co-occurrence of “Sanqiutian Jetty” with lexical items such as “combo ticket,” “very good,” and “recommend” implies that efficient admission systems not only triggered favorable emotional reactions and consolidated place attachment but also significantly enhanced visitors’ propensity for destination endorsement. In contrast, the semantic proximity between “Longtou Road” and attributes such as “commercialization” and “bustling” emphasizes its crucial role as an intensively commercialized, high-activity sector within tourists’ cognitive constructs.

By 2018, the semantic network configuration exhibited increasing centralization around the core node “Kulangsu.” Its direct associations with both “architecture” and “seaside” signify that visitors commenced simultaneous engagement with the island’s natural and cultural assets. Connections with “distinctive,” “history,” and “quiet” further disclose an incipient psychological acknowledgment of the site’s historical and cultural significance, coupled with a developing affective predilection for tranquil settings. Crucially, clusters surrounding iconic landmarks—particularly “Shuzhuang Garden,” “Haoyue Garden,” and the “Organ Museum”—in conjunction with “combo ticket” and “recommend” denote that tourists progressively formulated spatial cognition through integrated tourism experiences, which subsequently shaped their behavioral dispositions.

By 2019, the semantic network not only perpetuated but also consolidated these configurations. “Kulangsu” persisted as the central node, while intensified associations between attraction clusters and “combo ticket” denoted a crystallization in the cognitive framework of tourist spatial perception. Simultaneously, direct connections between “Kulangsu” and high-frequency affective markers—including “distinctive,” “history,” “very good,” “like,” and “recommend”—indicate that as tourists’ comprehension of the site’s heritage attributes intensified, their emotional bonds strengthened, consequently markedly elevating their recommendation intentions.

- (2)

- Stagnation Phase During the COVID-19 Pandemic (2020–2022)

During the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2022), tourism activity on Kulangsu exhibited a significant contraction (see Figure 8). In 2020, notwithstanding mobility restrictions imposed on visitors, “Kulangsu” persisted as the principal node within the semantic network. Intensified associations among terms including “experience,” “photograph,” “queue,” “internet-famous,” and “very good” imply a transition in tourist behavior toward a predominantly visual- and media-centric paradigm, principally manifested through photographic activities and social media engagements. Tourists participated in place-making via digital dissemination and visual representation, thereby establishing novel cognitive schemata and reinforcing place identity, while concurrently obtaining positive affective experiences.

Figure 8.

(a) Semantic Network Diagram in the 2020 Digital Gaze; (b) Semantic Network Diagram in the 2021 Digital Gaze; (c) Semantic Network Diagram in the 2022 Digital Gaze.

In 2021, under sustained travel constraints, the semantic clustering between “Kulangsu” and emblematic heritage sites such as “Sunlight Rock,” “Shuzhuang Garden,” “Piano Museum,” and “Haoyue Garden” became increasingly conspicuous. This phenomenon reflects a progressive refinement in tourists’ spatial cognition of the World Heritage Site, correlated with heightened identification with its cultural landmarks. Furthermore, the strengthened direct associations between “Kulangsu” and high-frequency terms including “architecture,” “distinctive,” “internet-famous,” and “like” substantiate the escalating impact of digital media content on tourist perception. The prominence of affectively charged descriptors, particularly “like” and “distinctive,” additionally indicates a more profound emotional engagement with the island’s distinctive cultural ambiance.

By 2022, the semantic network displayed an evolving pattern of multi-polar development. While “Kulangsu” retained its dominant position as the primary network node, distinct secondary clusters emerged surrounding “feature”. Systematic examination of term frequency distributions and co-occurrence patterns demonstrates that “feature” exhibited strong semantic connections with “experience,” “very good,” and “convenient”. These empirical observations imply that under stabilized pandemic control measures, decreased visitor numbers promoted a more peaceful and undisturbed spatial setting, ultimately cultivating a form of place attachment primarily characterized by positive emotional responses.

- (3)

- Comprehensive Deepening Development Phase (2023–2025)

As of 2023, with the gradual recovery of the tourism market, Kulangsu has maintained its central position in the tourism semantic network while developing multiple secondary semantic clusters around keywords such as “seaside” and “convenient.” Notably, the semantic connections between “Kulangsu” and concepts like “music” and “history” have significantly strengthened, indicating growing tourist recognition of culturally symbolic landmarks such as the Piano Museum. Furthermore, the direct association between “seaside” and leisure activities like “stroll” and “relaxing” reveals tourists’ preference for low-intensity, experiential tourism in natural settings. Additionally, the strong coupling between “convenient” and terms such as “very good” and “homestay” further demonstrates that tourists increasingly choose homestays as accommodation to facilitate in-depth exploration of Kulangsu and deeper engagement with local culture (see Figure 9).

Figure 9.

(a) Semantic Network Diagram in the 2023 Digital Gaze; (b) Semantic Network Diagram in the 2024 Digital Gaze; (c) Semantic Network Diagram in the 2025 Digital Gaze.

In 2024, Kulangsu preserved its pivotal role in the semantic network, while Shuzhuang Garden surfaced as a novel secondary cluster. Intensified connections between “Kulangsu” and concepts such as “culture,” “architecture,” and “music,” complemented by the incorporation of historical personalities like “Zheng Chenggong,” indicate enhanced tourist immersion in the island’s historical and humanistic aspects. This phenomenon concurrently suggests the rising significance of cultural memory within tourism encounters. Concurrently, the robust association between “Kulangsu” and “most beautiful corner” demonstrates the directional impact of digital visual culture on spatial perception. The appearance of “overlook” as a prevalent term additionally implies that elevated viewpoints during spatial navigation have evolved into a mechanism through which visitors develop aesthetic evaluation and spatial belongingness toward the island.

As of 5 June 2025, Kulangsu persists in occupying the nucleus of the semantic network, with Shuzhuang Garden retaining its secondary cluster status, accompanied by the formation of a new thematic constellation centered on “history.” Lexical association analysis discloses a dual configuration: firstly, enduring correlations between “Kulangsu” and fundamental descriptors including “architecture,” “Southern Fujian,” “international architecture expo,” and “music” remain; secondly, a recently established cluster connects “history” with “culture” and “integration.” These two relational frameworks collectively verify escalating tourist consciousness of Kulangsu’s distinctive worth, particularly its intercultural architectural synthesis, which is becoming progressively integrated within the cognitive of place.

5. Discussion

This study is grounded in two central hypotheses: first, that there exists a cognitive dissonance between the official narratives of WHS and the perceived realities constructed by tourists on digital platforms; second, that digital media are deeply embedded in the entire tourist experience, reshaping the sense of place and continuously evolving mechanisms of heritage perception. Through high frequency word analysis and semantic network analysis, we not only empirically validated these hypotheses but also revealed how, under the influence of the “digital gaze,” tourists shift from passive receivers of official values to active co-constructors of cultural meaning.

5.1. Misalignment Between Official Narrative and Digital Gaze

The relationship between culture and tourism demonstrates considerable potential [92]. Specifically, cultural tourism has been widely acknowledged as both a driver and facilitator for achieving sustainable development goals. As reported by ICOMOS (2022), the preservation and sustainable utilization of cultural heritage represents fundamental elements in maintaining the competitive advantage of WHSs [2]. With the continuous expansion of tourism, its impact on the interpretation, preservation, and presentation of cultural assets has become increasingly significant. This phenomenon creates opportunities for local economic development and cultural promotion; however, it simultaneously leads to concerns about authenticity erosion and heritage commodification [93]. In this context, a fundamental challenge involves assessing whether the OUV presented in official narratives can be successfully communicated and precisely understood through visitors’ digital engagement. This evaluation constitutes a crucial element in preserving the authenticity and integrity of heritage transmission.

Kulangsu, designated as a UNESCO WHS, is officially represented through the narrative of a “historic international community.” Its OUV is primarily defined by Sino-Western architectural hybridity, Amoy Deco Style decorative aesthetics, and cross-cultural urban landscapes. However, in the digital context, tourists’ perceptions of place reveal a marked divergence from this authorized narrative. Rather than engaging with the abstract heritage values, visitors tend to focus on popular attractions included in the joint ticket system—such as the Piano Museum and Sunlight Rock—or attribute new cultural meanings to unofficial spaces through UGC, such as the so-called “most beautiful corner.” This phenomenon indicates that digital platforms are actively generating alternative place perceptions and identifications, which may complement or even deviate from the official value framework.

It is noteworthy that the misalignment between official narratives and digital gazes is not entirely negative. On the one hand, it reveals the potential limitations of official value frameworks in digital dissemination; on the other hand, it creates opportunities to bridge cognitive gaps through technological means. Existing studies suggest that digital media can serve as a bridge between official narratives and visitor experiences. Interactive storytelling, immersive engagement, and community-driven digital practices provide new pathways for embedding OUV into communication. For instance, virtual reality–based museum exhibitions can enhance presence and immersion, thereby deepening visitors’ emotional involvement [94]; mixed reality–enabled cultural tours, through affective storytelling and virtual character design, transform abstract heritage values into tangible sensory experiences and visual symbols [95]; while applications of extended reality (XR) and the metaverse demonstrate significant potential in advancing heritage education by integrating authenticity with interactivity [96].

Thus, the divergence between official narratives and visitors’ digital gazes does not necessarily imply conflict but may instead lead to complementarity. Officially driven digital translations reinforce the systematicity and academic legitimacy of OUV, whereas visitor-generated digital gazes expand the perceptual dimensions and participatory forms of heritage. The complementarity achieved through digital mediation not only enhances the visibility and intelligibility of heritage values in digital spaces but also helps establish a dynamic balance between authenticity and public participation [97], thereby alleviating—and potentially reconciling—the disjunction between official narratives and digital gazes.

5.2. Evolving Sense of Place and the Role of Digital Gaze

Our findings indicate that digital media not only reshape visitors’ cognitive frameworks and spatial behaviors but also reconstruct place attachment and influence behavioral intentions.

Regarding the relatively stable features of the SOP, tourists’ spatial cognition is primarily anchored in Kulangsu’s core heritage nodes, spatial textures, and consumption-oriented scenes. High-frequency keywords such as “stroll” and “experience” reflect embodied and interactive perceptual processes driven by physical movement and active engagement. Consequently, tourists consistently develop positive affective bonds. Importantly, the term “recommend” represents more than basic information sharing; it indicates spontaneous approval and perceived value transmission.

The temporal evolution of Kulangsu’s SOP develops through three distinct phases. In the post-inscription period, implementation of a bundled ticketing system effectively integrated multiple cultural nodes, thereby improving visitors’ holistic understanding of the heritage site. During the pandemic-induced stagnation phase, mobility restrictions substantially decreased tourist activity, whereas lexical patterns including “distinctive” and “relaxing” demonstrated a transition in place identity from cultural recognition to everyday experiential. In the comprehensive development phase, frequent usage of terms such as “architecture,” “garden,” and “maritime garden” reveals enhanced visitor recognition of the island’s diverse cultural expressions.

Importantly, beyond the officially defined OUV, digital platforms have facilitated the emergence of “new cognitive places,” such as the widely recognized “most beautiful turn.” These informal landmarks have become focal points within tourists’ spatial cognition. Not only do they guide visual and performative behaviors—such as photography and social media check-ins—but they also amplify dissemination across digital networks. As tangible expressions of heritage value, these spaces are undergoing active reinterpretation and renaming by visitors. While such user-generated identifiers may diverge from institutional narratives, they contribute to an expanded and pluralistic understanding of heritage value. Through these new forms of place attachment, they effectively enhance tourists’ willingness to recommend the site and increase their intention to revisit.

5.3. The Digital Turn in Heritage Perception

This study develops a multi-actor analytical framework to evaluate sustainable strategies for preserving and transmitting the OUV of WHS, with specific focus on authenticity. Previous research has mainly examined the authoritative function of public institutions in establishing and maintaining officially recognized heritage values. However, the influence of digital perspectives on heritage value formation remains understudied. To fill this research void, we systematically investigate the contrasts and connections between “authorized narratives” and “digital gaze,” revealing how digital media reconstruct and redefine heritage significance.

The results indicate that the digital gaze selectively integrates components from institutional OUV narratives. In some cases, this leads to partial inaccuracies or distortions that could potentially compromise authenticity preservation. However, digital participation simultaneously generates new opportunities for value expression. More precisely, digital engagement enables visitors to collaboratively develop alternative value dimensions, consequently enhancing emotional connections and consolidating place identity. Furthermore, these experiential processes directly influence visitors’ behavioral intentions. These observations are consistent with existing literature that acknowledges digital media’s role in redefining heritage perception.

Furthermore, the study contributes to the theoretical understanding of digitally mediated SOP by proposing a structured, three-phase analytical model—referred to as the “digital gaze SOP pathway” (Figure 10). This model illustrates the iterative and evolving process through which SOP is developed via digital engagement: (1) in the pre-visit phase, users interact with digital content to construct imaginative geographies and preliminary perceptions of place; (2) in the on-site phase, embodied practices such as photography, video recording, and live streaming enhance multisensory experiences and foster individualized spatial engagement; (3) in the post-visit phase, the sharing and circulation of digital content—including images, videos, and interactive feedback—enable emotional reflection and contribute to the co-production of place narratives. Sustained by user-generated content and affective resonance, this cycle offers an expanded conceptual lens for analyzing digital place-making processes in both heritage and urban tourism contexts.

Figure 10.

Generation Logic of WHS SOP Under Digital Gaze (Source: Drawn by the authors).

5.4. Reframing Cognitive Pathways and Optimizing Experiential Mechanisms

From a policy and heritage management perspective, this study provides the following recommendations to strengthen the communicative effectiveness and adaptive capacity of cultural heritage in the digital era.

First, heritage authorities should adopt proactive strategies for monitoring and integrating tourists’ digital perceptions. This includes systematically implementing digital behavior tracking tools—such as semantic keyword analysis and image tag recognition—to detect real-time shifts in tourist sentiment and perception, thereby enabling the dynamic adjustment of official narrative emphases.

Second, stronger coupling between official value narratives and user-generated content should be encouraged. This can be operationalized through the creation of narrative intervention nodes—such as story-based signage systems or AI-guided digital tours—as well as improvements in path accessibility and the provision of interactive social spaces. Such measures can help guide tourists toward a deeper understanding and internalization of authorized heritage values through participatory engagement.

Finally, a structured mechanism for pluralistic participation and co-creation should be implemented, encouraging joint reinterpretation of heritage values by local communities, tourists, and cultural institutions. This approach promotes a shift from unidirectional interpretation to collective narrative production, thereby enhancing both inclusivity and resilience in heritage communication systems.

6. Conclusions

This study employs Kulangsu, a UNESCO WHS, as a case study to examine how tourists develop cognitive representations, establish place attachment, and participate in heritage value dissemination through digital platforms. Based on high-frequency word analysis and semantic network analysis, the research tests two primary hypotheses: (1) a discrepancy between official narratives and tourist perceptions, and (2) the dynamic nature of place attachment. The results demonstrate that digital platforms play a pivotal role in shaping heritage perception mechanisms. The results demonstrate the significant role of digital platforms in shaping heritage perception mechanisms.

This research makes three key contributions. Specifically, it identifies a significant gap between tourist perceptions expressed on digital platforms and official heritage narratives, creating a “digital gaze” that focuses on iconic landmarks and visually optimized check-in locations. Second, it demonstrates that SOP is not static or geographically confined but rather constitutes a dynamic, iterative process shaped by pre-visit expectations, on-site experiences, and post-visit reflections. Third, the results indicate that tourists are transitioning from passive cultural consumers to active participants in heritage meaning creation, where digital media serves as a critical mediator in both perception and dissemination processes. These findings contribute to three key areas: (1) enhancing comprehension of OUV communication, (2) advancing theoretical frameworks of digital place-making influenced by the digital gaze, and (3) introducing novel analytical approaches for examining heritage discourse in digital contexts.

Kulangsu serves as a representative case, and both the methodological framework and findings can be extended to other WHSs. Nevertheless, this study has certain limitations. First, the analysis primarily addresses macro-level patterns of perception and value transformation, without adequately accounting for individual-level differences such as demographic characteristics, educational background, and social media usage, all of which may influence how tourists interpret and construct heritage values. Second, only partial manual verification was applied during text processing, and potential segmentation errors may have reduced the precision of the results. Future research should employ stratified sampling or mixed-methods approaches to better capture individual variations and further strengthen the robustness of text analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.W.; methodology, H.W.; software, H.W.; analysis, H.W.; resources, H.W.; data curation, H.W. and W.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, H.W.; writing—review and editing, H.W., X.S., M.Z. and S.K.; visualization, H.W.; supervision, H.W., X.S., M.Z. and S.K.; project administration, H.W. and S.K.; funding acquisition, H.W., X.S. and M.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the grant from the Fujian Province Social Science Foundation Project–General Project, grant number FJ2025B057; the Huaqiao University Research Project(Special Research Project on “Overseas Dissemination of Chinese Culture by Overseas Chinese”), grant number 2024HQYJ11; the Huaqiao University High-level Talent Research Start-up Fund Project–Science and Technology Category, grant number 20BS111; the Natural Science Research Project of Anhui Educational Committee, grant number 2023AH040038; the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 52408045; the Fujian Provincial Educational Science "14th Five-Year" Plan 2023 Annual Research Project "Exploration and Practice of Context-Aware Mobile Learning (CAML) in Outdoor Field Courses for Landscape Architecture Majors under the Background of Digital Transformation", project number FJJKBK23-138.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The digital gaze data used in this study were collected from publicly accessible review content on Dianping (www.dianping.com) and Ctrip (www.ctrip.com). In accordance with research ethics standards, only data fields directly relevant to the research objectives—such as review text and posting date, were collected. No personally identifiable information was retrieved or stored. The data were used solely for academic research purposes. Detailed descriptions of the data sources and collection procedures are provided in Section 3.2 of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| WHS | World Heritage Site |

| OUV | Outstanding Universal Value |

| SOP | Sense of Place |

| UGC | User-Generated Content |

References

- Zhang, C.; Wu, H. Sustainable tourism management at World Heritage properties. In China World Heritage Capacity-Building Manual: Volume 5; UNESCO Office in Beijing: Beijing, China, 2021; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379631 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS). International Cultural Heritage Tourism Charter. 2022. Available online: https://admin.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/International-Cultural-Heritage-Tourism-Charter_EN_IT.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Dong, Q. Using natural language processing to evaluate local conservation text: A study of 624 documents from 303 sites of the World Heritage Cities Programme. J. Cult. Herit. 2024, 70, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liang, J.; Huang, J.; Shen, H.; Li, X.; Law, A. Evaluating tourist perceptions of architectural heritage values at a World Heritage Site in South-East China: The case of Kulangsu Island. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 60, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koufodontis, N.I.; Gaki, E. UNESCO urban world heritage sites: Tourists’ awareness in the era of social media. Cities 2022, 127, 103744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nian, S.; Bao, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y. How does the tourist experience affect the conservation of World Heritage Sites via the stimulus–organism–response model? Mount Sanqingshan National Park, China. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xiong, K.; Fei, G.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y. Aesthetic value protection and tourism development of the world natural heritage sites: A literature review and implications for the world heritage karst sites. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nian, S.; Li, D.; Zhang, J.; Lu, S.; Zhang, X. Stimulus–organism–response framework: Is the perceived outstanding universal value attractiveness of tourists beneficial to World Heritage Site conservation? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Zee, E.; Camatti, N.; Bertocchi, D.; Shomali, K.W. UNESCO World Heritage Site label and sustainable tourism in Europe: A UGC analysis. Reg. Stud. 2024, 58, 1858–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urry, J.; Larsen, J. The Tourist Gaze 3.0; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, H.; Zhou, M.; Kang, S.; Zhang, J. Sense of place of heritage conservation districts under the tourist gaze: Case of the Shichahai heritage conservation district. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nian, S.; Zhang, H.; Mao, L.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, H.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y. How outstanding universal value, service quality and place attachment influences tourist intention towards World Heritage conservation: A case study of Mount Sanqingshan National Park, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, N.M.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Prayag, G. Psychological determinants of tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: The influence of perceived overcrowding and overtourism. J. Travel Res. 2023, 62, 644–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oorgaz-Agüera, F.; Puig-Cabrera, M.; Moral-Cuadra, S.; Domínguez-Valerio, C.M. Authenticity of architecture, place attachment, identity and support for sustainable tourism in World Heritage cities. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 31, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, T.; Zheng, X.; Yan, J. Contradictory or aligned? The nexus between authenticity in heritage conservation and heritage tourism, and its impact on satisfaction. Habitat Int. 2021, 107, 102307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, A.M.W.; Yeh, S.S.; Zhou, Y.; Hung, C.W.; Huan, T.C. Exploring the influence of historical storytelling on cultural heritage tourists’ value co-creation using tour guide interaction and authentic place as mediators. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2024, 50, 101198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Carneiro, M.J. The influence of interpretation on learning about architectural heritage and on the perception of cultural significance. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2021, 19, 230–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K.; Moscardo, G. Encouraging sustainability beyond the tourist experience: Ecotourism, interpretation and values. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 1175–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Lovett, J.; Cheung, L.T.; Duan, X.; Pei, Q.; Liang, D. Adapting to social media: The influence of online reviews on tourist behaviour at a World Heritage site in China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 26, 1125–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.C.; Deng, T.; Cheng, H. The role of social media advertising in hospitality, tourism and travel: A literature review and research agenda. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 3419–3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zheng, J.; Tang, L.R.; Wang, X.; Yang, L. Do you “like” my tweets? Exploring verbal and visual cues in traveler’s dual-coding process. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2025, 42, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Peng, X.; Liu, X.; Tang, H.; Li, W. A study on shaping tourists’ conservational intentions towards cultural heritage in the digital era: Exploring the effects of authenticity, cultural experience, and place attachment. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2025, 24, 1965–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvica, S.; Arru, V.; Pinna, N.; Andra-Topârceanu, A.; Carboni, D. Stintino (Sardinia, Italy): A Destination Balancing Tourist Gaze and Local Heritage. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.Y.; Li, Y.Q.; Ruan, W.Q.; Zhang, S.N.; Li, R.; Zhang, K.F. To understand or to touch? Evoking tourists’ cultural preservation commitment through heritage tourism interpretation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2025, 33, 168–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Phenomenology of Perception; Landes, D.A., Translator; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Agapito, D.; Mendes, J.; Valle, P.O. Exploring the conceptualization of the sensory dimension of tourist experiences. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2014, 2, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, P.; White, R. Mental Maps; Penguin Books: London, UK, 1974; p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J.; Yue, J.; Zhang, J.; Qin, P. Research on spatio-temporal characteristics of tourists’ landscape perception and emotional experience by using photo data mining. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walmsley, D.J.; Lewis, G.J. People and Environment: Behavioural Approaches in Human Geography, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Choi, B.K.; Lee, T.J. The role and dimensions of authenticity in heritage tourism. Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandža Bajs, I. Tourist perceived value, relationship to satisfaction, and behavioral intentions: The example of the Croatian tourist destination Dubrovnik. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Dai, J.; Silverman, R.M.; Wu, L.; Taylor, H.L., Jr. Public discourse in the aftermath of the 2022 mass shooting in Buffalo, NY: Insights from social media data and ChatGPT. Cities 2025, 168, 106440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta-Álvarez, R.; Cambra-Fierro, J.J.; Fuentes-Blasco, M. The interplay between social media communication, brand equity and brand engagement in tourist destinations: An analysis in an emerging economy. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 16, 100413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, K.; Alam, M.M.D.; Malik, A.; Tarhini, A.; Al Balushi, M.K. From likes to luggage: The role of social media content in attracting tourists. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorta-Preen, J.M.; Santana-Talavera, A. Shaping Places Together: The Role of Social Media Influencers in the Digital Co-Creation of Destination Image. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigne, E.; Ruiz, C.; Cuenca, A.; Perez, C.; Garcia, A. What drives the helpfulness of online reviews? A deep learning study of sentiment analysis, pictorial content and reviewer expertise for mature destinations. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; He, Z.; Wu, G.; Shi, C. Are all tourism review information on the platforms equally useful? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 57, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, B.; Ye, Q.; Kucukusta, D.; Law, R. Analysis of the perceived value of online tourism reviews: Influence of readability and reviewer characteristics. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunjungsari, H.K.; Willyanto, V.; Hoo, W.C.; Wolor, C.W. How User-Generated Content Affects Tourist Loyalty Behaviour at Cultural Heritage Sites in Indonesia. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2025, 20, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Song, C.; Li, X. The deconstruction and re-cognition of tourist gaze. Tour. Trib. 2024, 39, 16–27. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Deng, X.; Liu, B. Managing urban citizens’ panic levels and preventive behaviours during COVID-19 with pandemic information released by social media. Cities 2022, 120, 103490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munar, A.M.; Jacobsen, J.K.S. Motivations for sharing tourism experiences through social media. Tour. Manag. 2014, 43, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Meng, F.; Zhang, X. Are you happy for me? How sharing positive tourism experiences through social media affects posttrip evaluations. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 477–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M. Sharing tourism experiences in social media: A systematic review. Anatolia 2024, 35, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magasic, M. The ‘selfie gaze’and ‘social media pilgrimage’: Two frames for conceptualising the experience of social media using tourists. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2016, Proceedings of the International Conference, Bilbao, Spain, 2–5 February 2016; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, M.; Richter, T. Transportation and need for affect in narrative persuasion: A mediated moderation model. Media Psychol. 2010, 13, 101–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Ding, L.; Dong, H.; Lin, Z. Influence of User-Generated Content in Social Media on the Intangible Cultural Heritage Preservation of Gen Z Tourists in the Digital Economy Era. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 26, e2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, H.; Sadler, J.; Chapman, L. The value of Twitter data for determining the emotional responses of people to urban green spaces: A case study and critical evaluation. Urban Stud. 2019, 56, 818–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Pickering, S.; Geng, R.; Yen, D.A. Thanks for the memories: Exploring city tourism experiences via social media reviews. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 40, 100851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.L.; Leung, W.K.; Cheah, J.H.; Ting, H. Exploring the effectiveness of emotional and rational UGCs in digital tourism platforms. J. Vacat. Mark. 2022, 28, 152–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Richardson, S.; Goh, E.; Presbury, R. From the tourist gaze to a shared gaze: Exploring motivations for online photo-sharing in present-day tourism experience. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2023, 46, 101099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Cheung, L.T.; Lovett, J.; Duan, X.; Pei, Q.; Liang, D. Understanding the influence of UGC on tourist loyalty behavior in a cultural World Heritage Site. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2023, 48, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, R.W. Authenticity or continuity in the implementation of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention? Scrutinizing statements of outstanding universal value, 1978–2019. Heritage 2020, 3, 243–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, C.; Rössler, M. Introduction of management planning for cultural world heritage sites. In Aspects of Management Planning for Cultural World Heritage Sites: Principles, Approaches and Practices; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyazıcı, M.; Turgut, S. International Cultural Heritage Law: A Systematic Review of Its Effectiveness. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2025, 16, 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leask, A. Visitor attraction management: A critical review of research 2009–2014. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 334–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nian, S.; Chen, M.; Zhang, X.; Li, D.; Ren, J. How outstanding universal value attractiveness and tourism crowding affect visitors’ satisfaction? Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhang, C.; Liu, L. Communicating the outstanding universal value of World Heritage in China? The tour guides’ perspective. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 1042–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]