Abstract

The acceleration of industrialization and urbanization have led to the increasingly serious problem of waste gas pollution. Pollutants such as sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen oxides (NOx), volatile organic compounds (VOCs), ammonia (NH3), formaldehyde (HCHO), and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) emitted from industrial production, transportation, and agricultural activities have posed a major threat to the ecological environment and public health. Although traditional physical and chemical treatment methods can partially reduce the concentration of pollutants, they face three core bottlenecks of high cost, high energy consumption, and secondary pollution, and it is urgent to develop sustainable alternative technologies. In this context, probiotic waste gas treatment technology has become an emerging research hotspot due to its environmental friendliness, low energy consumption characteristics, and resource conversion potential. Based on the databases of PubMed, Web of Science Core Collection, Scopus, Embase, and Cochrane Library, this paper systematically searched the literature published from 2014 to 2024 according to the predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria (such as research topic relevance, experimental data integrity, language in English, etc.). A total of 71 high-quality studies were selected from more than 600 studies for review. By integrating three perspectives (basic theory perspective, environmental application perspective, and waste gas treatment facility perspective), the metabolic mechanism, functional strain characteristics, engineering application status, and cost-effectiveness of probiotics in waste gas bioconversion were systematically analyzed. The main conclusions include the following: probiotics achieve efficient degradation and recycling of waste gas pollutants through specific enzyme catalysis, and compound flora and intelligent regulation can significantly improve the stability and adaptability of the system. This technology has shown good environmental and economic benefits in multi-industry waste gas treatment, but it still faces challenges such as complex waste gas adaptability and long-term operational stability. This review aims to provide useful theoretical support for the optimization and large-scale application of probiotic waste gas treatment technology, promote the transformation of waste gas treatment from ‘end treatment’ to ‘green transformation’, and ultimately serve the realization of sustainable development goals.

1. Introduction

With the acceleration of industrialization and urbanization, waste gas pollution has become a core issue that threatens the ecological environment and public health [1]. Industrial production, transportation, agricultural activities, and other processes emit a large amount of waste gas, including sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen oxides (NOx), volatile organic compounds (VOCs), ammonia (NH3), formaldehyde (HCHO), hydrogen sulfide (H2S), methane (CH4) and other pollutants [2]. According to statistics, in 2024, the global fossil fuel industry’s methane emissions exceeded 120 million tons, which is the absolute ‘main source’ of methane emissions. Abandoned oil and gas wells and coal mines also emit about 8 million tons of methane, and the amount of methane leakage from oil and gas facilities detected by satellites in 2024 hit a record high. Industrial coating, textile dyeing and finishing, furniture manufacturing, packaging and printing, chemical fiber, and other industries are important sources of VOCs. Heavy industrial processes such as iron and steel, metallurgy, and cement produce a large amount of NO, SO2, and carbon monoxide (CO). These pollutants will not only lead to the deterioration of air quality, cause environmental disasters such as haze and acid rain, but also cause serious damage to the human respiratory system and cardiovascular system; increase the incidence of respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and other diseases; and threaten human life and health [3]. Long-term exposure to high concentrations of particulate matter such as PM {2.5} will significantly increase the risk of lung cancer and other diseases [4]; SO2 and NOx are the main precursors of acid rain. Acid rain can destroy soil and water ecosystems, affecting crop growth and aquatic organisms’ survival [5]. Toxic and harmful gases in the air are mainly divided into two categories. According to their different properties, they can be divided into irritating gases and asphyxiating gases [6]. Irritating gases are gases that irritate the eyes, respiratory mucosa, and skin, most commonly ammonia and formaldehyde [7]; asphyxiating gases refer to toxic gases that may cause hypoxia in the body, including hydrogen sulfide and phosphine, most of which are corrosive. Inhalation of certain high concentrations of harmful toxic gases can lead to poisoning, often accompanied by multi-functional disorders, which greatly threaten human health.

Traditional waste gas treatment methods can usually be divided into three categories: 1. Separation technology: Physical separation of pollutants from the airflow (such as adsorption, absorption). However, the adsorbent in the adsorption method needs to be replaced and regenerated regularly, and the cost is high; the combustion method consumes a lot of energy and may produce new pollutants [8]. 2. Destruction technology: Convert pollutants into harmless substances (such as incineration and photolysis) by chemical or biological methods. Although it can reduce the concentration of pollutants in the exhaust gas to a certain extent, there are problems such as high cost, high energy consumption, and easy to produce secondary pollution [9]. 3. Recycling technology: Capture and convert pollutants into recyclable resources. The specific treatment methods are as follows in Table 1.

Table 1.

Introduction of traditional processing technology.

In this context, the biological method of using compound probiotics to treat waste gas has gradually become a research hotspot because of its advantages of environmental friendliness, low cost, low energy consumption, and strong sustainability. Probiotics are a class of active microorganisms that are beneficial to the host. In waste gas treatment, they can transform pollutants in the exhaust gas into harmless or low-hazardous substances through their own metabolic activities [10]. Probiotics for waste gas treatment mainly include three categories of microorganisms. See (Table 2).

Table 2.

Waste gas treatment probiotics.

This biological treatment method can not only effectively reduce the emission of exhaust pollutants and achieve non-toxic conversion [13], but also avoid the secondary pollution caused by traditional methods, which is of great significance for improving air quality and protecting the ecological environment.

The performance of a biological waste gas treatment system is affected by the interaction of multiple physical, chemical, and biological variables when a large-scale waste gas treatment is carried out in a factory. Optimization design in production is the process of balancing these parameters (as shown in Table 3). From the perspective of sustainable development, probiotic treatment of waste gas conforms to the concept of green development, helps to promote coordinated development of the economy and environment, and provides a new technical way to achieve sustainable development goals.

Table 3.

Optimize the design in production.

This article includes but is not limited to the following databases: PubMed, Web of Science Core Collection, Scopus, Embase, and Cochrane Library. The basic period is more than 600 articles retrieved in the past ten years. All studies published within this time frame were included in the consideration, and non-English literature, meeting abstracts, research lacking full-text, and topic-independent research were clearly excluded. In total, 71 studies that met the criteria were included in this article from the remaining literature. The data extraction process is independently extracted by several authors and synthesized through discussion. This paper systematically reviews the application of probiotics in waste gas treatment and conversion from the perspectives of basic theoretical principles, environmental applications, and waste gas treatment facilities, aiming to provide theoretical support for technical optimization and large-scale applications and achieve green conversion.

2. Mechanism of Waste Gas Conversion Driven by Microbial Metabolism

As a ‘natural engineer’ of the earth’s material cycle, microorganisms can convert toxic and harmful gases into harmless substances through a series of enzyme-catalyzed reactions [14]. The waste gas treatment function of probiotics (generally refers to the functional microbial community with efficient degradation ability to environmental pollutants) is essentially a biological purification process achieved through energy metabolism and material transformation [15]. The core lies in the synergy of the flora and the precise regulation of the metabolic pathway. The conversion of waste gas by probiotics is based on the biotransformation process of pollutants driven by microbial metabolism, that is, microorganisms absorb pollutants in waste gas as a carbon source or energy or electron donor and convert them into harmless or low-toxic products through redox reactions under the catalysis of the intracellular enzyme system [16]. This process depends on the functional division of the compound probiotics: different strains form metabolic complementation for specific pollutants. For example, sulfur-oxidizing bacteria are specifically responsible for the oxidation of sulfur-containing compounds, while Pseudomonas and Bacillus dominate the degradation of VOCs [17]. Fungi can assist in the decomposition of complex organic compounds in a hypoxic environment. This ‘specific metabolism + synergistic metabolism’ model has greatly improved the treatment efficiency of mixed waste gas.

2.1. Biotransformation of Typical Waste Gases

The conversion of different types of waste gases by probiotics follows a specific metabolic pathway, and its core is to achieve ‘non-toxicity’ and ‘mineralization’ of pollutants through enzyme catalysis and energy transfer [18]. The catalytic effect and background of key enzymes in the biological treatment of waste gas are as follows. See Table 4.

Table 4.

The catalytic effect and background of key enzymes in biological treatment of waste gas.

A variety of waste gases can react with organic acids to form onium salts [26]. The onium ion was first formed by the lone pair electrons of the nuclear atoms of the mononuclear hydrides of nitrogen, oxygen, and halogen as the cation formed by the protonation of the Bronsted base, which was called the XXium salt [27]. In the microecological environment of probiotics and organic acids, these toxic and harmful gases can obtain a proton and ionize and then form onium salts with organic acids. These onium salts are precipitated in different states (such as flocculent) in the sludge and are decomposed by subsequent redox [28]. The chemical equation is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Reaction equation of organic acid and toxic and harmful gas.

2.2. Key Influencing Factors of Metabolic Regulation

The metabolic activity and waste gas conversion efficiency of probiotics are highly dependent on environmental conditions and the nutrient supply. The core regulatory factors include physical and chemical environmental parameters and nutrient substrate synergy. See Table 6.

Table 6.

The catalytic effect and background of key enzymes in the biological treatment of waste gas.

2.3. Types of Probiotics Converting Harmful Gases

In the process of industrialization and urbanization, harmful gases such as sulfur dioxide (SO2), ammonia (NH2), and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) continue to be emitted, causing environmental disasters, such as haze and acid rain, and seriously threatening public health. The traditional physical and chemical treatment technology is limited by high energy consumption, secondary pollution, and cost bottlenecks, and it is urgent to develop sustainable solutions. As a natural ‘biocatalyst’, probiotics are becoming an emerging force for waste gas purification due to their efficient metabolic diversity and environmental compatibility. The following table summarizes the types of probiotics that convert harmful gases; see (Table 7).

Table 7.

Types of probiotics converting harmful gases.

3. Genetic Characteristics of Probiotics Converting Harmful Gases

The genetic characteristics of microorganisms determine their core metabolic capacity, environmental adaptability, and engineering potential, which is the theoretical basis for evaluating and optimizing their ability to treat harmful gases. By analyzing the composition, structure, and regulatory sequence of the gene cluster, its metabolic pathway can be completely restored, and the rate-limiting steps of the degradation process, intermediate products, and induction conditions of gene expression (such as which pollutants trigger gene expression) can be understood. This provides a theoretical basis for optimizing operating conditions. The following are the genetic characteristics associated with the waste gas treatment capacity of seven microorganisms in Section 2.3. See Table 8.

Table 8.

Genetic characteristics associated with waste gas treatment capabilities of 7 microorganisms.

4. Environmental Application Scenarios—Multi-Domain Waste Gas Treatment Solutions

Probiotic technology has realized the engineering application of waste gas treatment in many scenarios such as industry, agriculture, and urban management by virtue of its characteristics of ‘targeted degradation + environmental friendliness’, and has formed customized solutions for different pollution sources. It includes the stable emission of VOCs and sulfur-containing waste gas in industrial waste gas treatment, the control of odorous gases such as NH3 and H2S in animal husbandry and waste treatment in agricultural activities, and the efficient treatment of urban waste gas.

4.1. Industrial Waste Gas Pollution Control

VOCs and sulfur-containing waste gas emitted from industrial production (such as chemical, printing, pharmaceutical) have complex components and large concentration fluctuations. Probiotic technology has achieved stable and standard emissions through bioreactors [45]. For example, the application of a biofilter, biotrickling filter, and biological washing tower in chemical industry parks, food processing and fermentation, and livestock and poultry breeding have formed a mature technology system [46]. Specific industries and microbial treatment technologies are shown in the table below. See Table 9.

Table 9.

Specific industries and microbial treatment technologies.

Among them, a large coal chemical enterprise uses ceramsite-activated carbon composite filler biofilter to treat waste gas containing benzene, toluene, and xylene (inlet concentration of 200–800 mg/m3). By inoculating Pseudomonas and Bacillus complex bacteria, the removal rate of VOCs is stable at more than 90% under the condition of an empty bed residence time of 30–60 s [47], and the outlet concentration meets the limit requirements of petrochemical industry pollutant emission standards. The low-concentration VOCs (100–300 mg/m3) in the printing industry can be treated by a biotrickling filter [48], using ethanol as a co-metabolism carbon source, so that the degradation rate of ethyl acetate, butanone, and other solvents can reach 95%, and the operating cost is only 1/3 of the activated carbon adsorption method [49].

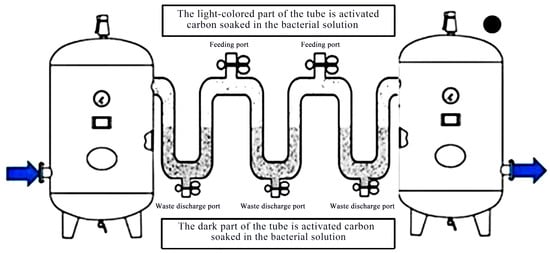

For the H2S-containing waste gas (concentration of 500–5000 mg/m3) in the chemical and refining industries, the probiotic activated-carbon washing tower achieves efficient desulfurization through gas countercurrent contact [50]. The experimental equipment is shown in Figure 1. Thiobacillus thiooxidans and Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans (concentration of ≥108 CFU/mL) were inoculated into the spray liquid in the tower, and activated carbon was added. Using the adsorption of activated carbon, the probiotics and organic acids contained in the microecological liquid entered the micropores of activated carbon and adhered to the inner surface of activated carbon. The valve was opened, and hydrogen sulfide was introduced into a multiple U-tube containing activated-carbon and probiotic liquid for adsorption. After H2S was absorbed in the liquid phase, it was oxidized by the flora to elemental sulfur (recovery rate > 85%). After treatment, the concentration of H2S in the exhaust gas can be reduced to <10 mg/m3.

Figure 1.

High concentration hydrogen sulfide waste gas adsorption experimental equipment diagram.

4.2. Agricultural Source Pollution Control

Animal husbandry and waste treatment in agricultural activities are the main sources of odorous gases such as NH3 and H2S (Table 10). Probiotic technology can achieve pollution control through ‘source control + process treatment’.

Table 10.

Waste gas treatment in agricultural activities.

The regulation of intestinal flora by adding probiotics to feed can reduce NH3 emissions from the source [51]. Studies have shown that adding 0.1–0.5% of Lactobacillus plantarum (concentration 109 CFU/g) to pig feed can inhibit urease activity by adjusting intestinal pH value (reducing 0.5–1.0 units) and reduce NH3 produced by protein decomposition [52]. The experimental data show that the NH3 concentration in the piglet house can be reduced by 30–40%, and the H2S emission in the feces can be reduced by more than 25%. In addition, the farm manure treatment process uses a composite microbial agent (Bacillus + yeast) spray, which can immediately decompose the escaped odorous substances, and the treatment efficiency is more than 80% [53].

In the composting process of straw and livestock manure, anaerobic bacteria are prone to produce odorous gases such as H2S and methyl mercaptan, which can be significantly inhibited by inoculation of compound microbial agents (such as Desulfovibrio + actinomycetes) [54]. When ‘straw–chicken manure’ compost was used in a vegetable planting base, the release of H2S in the compost was reduced by 60–70% compared with the control group when 1.0% compound microbial agent (concentration of 108 CFU/g) was added, and the composting time was shortened by 5–7 days [55]. The effective nitrogen content in organic fertilizer increased by 15–20%, which achieved the dual benefits of ‘deodorization–upgrading’.

4.3. Urban Waste Treatment and Formaldehyde Adsorption in New Houses

The composition of waste gas in municipal waste transfer stations and landfills is complex (including H2S, methyl mercaptan, CH4, VOCs, etc.) [56]. Probiotic technology can achieve efficient treatment through flexible application (Table 11). The main toxic and harmful gas in the new room is formaldehyde [57].

Table 11.

Waste gas treatment in urban garbage.

For the short-term concentrated emission of high concentration odor gas (H2S concentration can reach 100–500 mg/m3) from the transfer station [58], the environmental control probiotic spray system was used for treatment. The system combines a compound microbial agent (sulfur-oxidizing bacteria + yeast) with a surfactant, and fully contacts with the exhaust gas through high-pressure atomization (droplet diameter 5–20 μm). The decomposition rate of H2S, methyl mercaptan, and other substances under the action of the flora is >95% within 10–30 min [59].

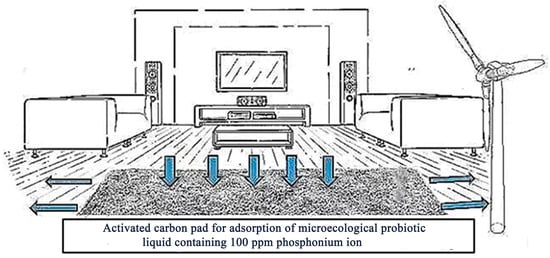

The formaldehyde adsorption facility in the new room is to place an activated carbon pad in the new room that adsorbs a microecological probiotic liquid with 100 ppm phosphonium ions (Figure 2) [60]. A large fan is placed on the side of the mat to allow the indoor air containing formaldehyde to be filtered through the mat, and the indoor walls and floors are sprayed with a microecological probiotic liquid diluted 10 times with 100 ppm phosphonium ions. It has a good adsorption effect.

Figure 2.

New room formaldehyde adsorption experimental equipment diagram.

5. Engineering Design and Optimization

The large-scale application of probiotic waste gas treatment technology needs to realize the dynamic balance of ‘efficiency–cost–stability’ through three core paths: bioreactor design innovation, flora immobilization technology upgrading, and precise regulation of process parameters. At the level of bioreactor design, it is necessary to develop a multi-stage coupling structure (such as a ‘biotrickling filter–activated-carbon adsorption’ combined system), and use the microporous structure of ceramsite or modified plastic filler to enhance the gas–liquid mass transfer efficiency, so that the unit reactor volume treatment capacity is greatly improved. The immobilization technology of bacteria is the key guarantee. The loss rate of bacteria is reduced, and the service life is greatly prolonged by sodium alginate–PVA double carrier embedding method or magnetic nanoparticles loading functional bacteria (such as Thiobacillus thiooxidans). Process parameter optimization focuses on operation threshold control. At present, the design and performance of microbial waste gas treatment engineering are summarized into the following five parts through the types of pollutants (Table 12).

Table 12.

Design and performance of microbial waste gas treatment engineering.

5.1. Mainstream Bioreactor Technology and Characteristics

A bioreactor is the core place for probiotics to come in contact with waste gas and complete metabolic transformation. Its structural design directly affects mass transfer efficiency and microbial activity [61]. The current mainstream technologies include a biofilter, biotrickling filter, and membrane bioreactor. The biofilter is composed of a filler layer, an air distribution system, and a spray system. The filler (such as ceramsite, activated-carbon, bark, etc.) provides an attachment carrier for the flora [62]. The porous structure of ceramsite/activated-carbon (porosity 50–70%) can enhance the gas residence time and bacterial colonization area. The biofilter of a printing workshop uses ‘ceramsite + activated-carbon’ composite filler (volume ratio 1:1), which is 15–20% higher than the VOCs removal rate of a single filler. During the operation, the waste gas enters from the bottom, comes into contact with the biofilm on the surface of the filler, and is degraded. It is suitable for the treatment of low and medium concentration waste gas (VOCs < 1000 mg/m3), and the empty bed residence time is usually 30–120 s [63]. The core difference between the biotrickling filter and the biofilter is the addition of a liquid circulation system. The nutrient solution (including carbon source, nitrogen source, and trace element) flows from top to bottom through the spray device to form a liquid film on the surface of the filler. When the exhaust gas is the countercurrent contact, the pollutant is first dissolved in the liquid film and then degraded by the flora [64]. The design optimizes mass transfer efficiency, especially for the waste gas with high water solubility (such as H2S and NH3). When the biotrickling filter of a chemical enterprise treats the waste gas containing H2S, the mass transfer coefficient is increased by 30% by adjusting the liquid circulation (2–5 L/m2·h), and the treatment load reaches 50–100 g/(m3·h), which is significantly higher than that of the biofilter [65]. Membrane bioreactor (MBR) combines ultrafiltration membrane module with biological reaction tank [66]. The interception of membrane can maintain the concentration of bacteria in the reactor at 109–1010 CFU/mL (5–10 times that of traditional reactor), which greatly improves the degradation efficiency [67]. An electronic factory uses MBR to treat formaldehyde-containing waste gas (inlet concentration of 50–200 mg/m3). Under the condition of hydraulic retention time (HRT) of 1–2 h, the formaldehyde removal rate is stable at more than 95%, and the membrane module can intercept more than 99% of the functional bacteria, avoiding the loss of flora, and the operation cycle is extended to 3–6 months [68].

5.2. Immobilization Technology of Bacteria

Free bacteria are easy to lose with the fluid in the reactor and are sensitive to environmental fluctuations. Bacteria immobilization technology significantly improves the stability of microorganisms by limiting them in a specific space. Encapsulation immobilization uses natural polymer materials (such as sodium alginate) or synthetic materials (such as polyvinyl alcohol, PVA) to embed the flora in gel microspheres to form a ‘microecosystem’ [69]. For example, the desulfurization bacteria were embedded in 4% sodium alginate +2% CaCl2, the diameter of the microspheres was 2–3 mm, and the porosity was >60%. It can not only allow the diffusion of pollutants and nutrients but also protect bacteria from external shocks. In the treatment of H2S-containing waste gas, the half-life of the embedded bacteria (the time when the activity decreased to the initial 50%) was 2–3 times longer than that of the free bacteria. PVA gel is more suitable for high flow rate reactors due to its high mechanical strength (compressive strength > 0.5 MPa) [70]. The new carrier enhances the treatment efficiency through the synergistic effect of ‘adsorption–degradation’. The surface of modified biochar (such as corncob biochar oxidized by nitric acid) is rich in functional groups such as carboxyl and hydroxyl groups, and the adsorption capacity of VOCs can reach 0.1–0.5 g/g. At the same time, its porous structure provides attachment sites for the flora [71], forming a virtuous cycle of ‘adsorption enrichment–biodegradation’. A study showed that the removal rate of benzene series of modified biochar carrier was 40–50% higher than that of ordinary carrier [72]. Nanofiber carriers (such as polylactic acid nanofibers prepared by electrospinning) can load more bacteria due to their large specific surface area (>100 m2/g), and the fiber gap is conducive to gas mass transfer, which is excellent in low-concentration waste gas treatment [73].

5.3. Multivariable Discussion of Process Design and Scale

The design and amplification of microbial waste gas treatment systems is far from simple proportional amplification but requires systematic optimization and balance of multiple interrelated variables. For example, the core engine of technology: microbial strains. Screening and domestication of specific functional bacteria for target pollutants is the basis for efficient treatment. In practice, it is more inclined to use complex bacteria to degrade complex mixtures and enhance system stability by using the synergistic effect between microorganisms. The engineered strains need to tolerate pressure such as concentration shock, pH change, toxic substances (such as intermediate metabolites), and drying. When the microbial strains are prepared, immobilization is also an important step. Immobilizing microorganisms to form biofilms on the surface of the filler is the key to maintaining high biomass, preventing the loss of bacteria, and ensuring the treatment effect.

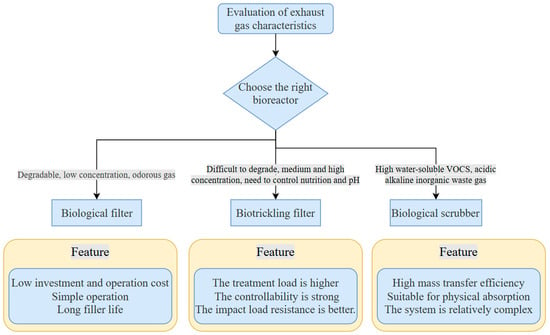

Secondly, the reactor design and well-designed operating parameters are used to create the best microenvironment. It usually includes two parts: the selection of reactor type and the coupling of process parameters. Common reactor types and their characteristics are shown in the following figures. The most suitable type should be selected according to the characteristics of exhaust gas: (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Selection of bioreactors.

The coupling of process parameters is mainly divided into three aspects: Empty bed residence time (EBRT) determines the contact time between exhaust gas and microorganisms, which is the core design parameter. The pH, temperature, and humidity must be maintained within the optimal range of microbial activity. Finally, appropriate nutrients can provide the necessary nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and trace elements for microbial growth.

By optimizing the inoculation ratio, microbial concentration, and intelligent regulation, the metabolic potential of probiotics can be maximized. For example, when the inoculation ratio (the mass ratio of functional flora to carrier) is controlled at 1.0–2.0, the flora can quickly form a biofilm without clogging the carrier pores [74]; the concentration of bacterial agent should be ≥107 CFU/mL. If the concentration is too low, the start-up cycle will be prolonged, and if the concentration is too high, the activity may be decreased due to nutritional competition. The debugging data of a biofilter showed that when the concentration of microbial agent increased from 106 CFU/mL to 108 CFU/mL, the VOCs treatment efficiency increased from 60% to 90%, but when it continued to increase to 109 CFU/mL, the efficiency increase was less than 5%, and the cost and benefit needed to be balanced [75]. Through on-line monitoring of pH, temperature, DO, and other parameters, combined with automatic feedback device to adjust nutrient solution supply, stable operation is achieved [76]. For example, an industrial waste gas treatment station uses a pH sensor (accuracy ± 0.1) to link with an automatic dosing pump. When the pH of the reactor deviates from the optimal range (±0.5), the acid/alkali regulator is automatically added [77]; the temperature sensor cooperates with the heating/cooling device to control the reactor temperature in the optimal range of ±1 °C, so that the fluctuation range of treatment efficiency is controlled within 5%, which greatly reduces the cost of manual operation and maintenance [78].

6. Whole Life Cycle Cost Disassembly

The cost of probiotics to treat waste gas needs to cover ‘initial investment + operating cost + maintenance cost’ and is significantly affected by the treatment scale and pollutant complexity (taking the 10,000 m3/h waste gas treatment system as an example). The initial investment cost control scheme is shown in Table 13. Table 14 shows the operation and maintenance plan. Table 15 shows the factors affecting the cost.

Table 13.

Initial investment cost.

Table 14.

Operation and maintenance costs.

Table 15.

Cost-influencing factors.

7. Conclusions

In this study, the research progress of probiotic technology in the field of waste gas treatment and conversion was systematically reviewed by integrating three perspectives: basic theory, environmental application, and engineering facilities. The core conclusions are as follows:

The purification of waste gas by probiotics is essentially an enzyme-catalyzed process driven by microbial metabolism. Key functional enzymes (such as methane monooxygenase, toluene dioxygenase, ammonia monooxygenase, glutathione-dependent formaldehyde dehydrogenase, etc.) are the core engines of pollutant biotransformation, and their activities are regulated by temperature, pH, oxygen concentration, nutrient balance, and the characteristics of pollutants. Understanding and optimizing these variables is the basis for improving degradation efficiency. Different microbial strains show specific degradation of specific pollutants due to their unique genetic characteristics and metabolic pathways. Bacterium (such as Pseudomonas, Bacillus) is the main degradation of VOCs; fungi have advantages in the treatment of hydrophobic VOCs by virtue of their mycelium structure. Chemoautotrophic bacteria (such as Thiobacillus thiooxidans) are the key to the treatment of inorganic odor gases (H2S, NH3). The construction of a functional complementary composite flora is an effective strategy for the treatment of multi-component mixed waste gas.

Probiotic technology has shown good application potential in many fields such as industry (petrochemical industry, printing and spraying), agriculture (livestock and poultry breeding, composting), and urban management (garbage treatment, new house formaldehyde). It can effectively treat VOCs, H2S, NH3, and other pollutants and has the advantages of environmental friendliness and relatively low operating costs. In the process of engineering, the successful large-scale application of technology depends on the rational design of the bioreactor (biofilter, biotrickling filter, membrane bioreactor), the optimization of microbial immobilization technology (such as embedding method, new carrier), and intelligent process control (pH, temperature, nutrient addition). However, the initial investment cost, adaptability to complex exhaust gas components, and long-term operational stability are still current challenges.

In summary, probiotic waste gas treatment technology represents a promising ‘green conversion’ scheme. Future research should focus on strengthening the performance of the strain by means of synthetic biology, dealing with complex scenarios through multi-technology coupling processes, and guiding its sustainable large-scale application through comprehensive life cycle assessment, so as to provide strong technical support for the realization of the ‘double carbon’ goal and environmental pollution control.

8. Future Prospect

At present, there are two technical bottlenecks. Insufficient environmental adaptability and heavy metal inhibition: Hg2+ and Pb2+ in industrial waste gas bind to the enzyme activity center of the flora (such as sulfhydryl group), resulting in inactivation (when the concentration of Hg2+ reaches 10 mg/m3, the activity of desulfurization bacteria decreases by >70%). 2. The influence of extreme conditions: Low temperature (90%) plugs the pores of the carrier, and the treatment efficiency fluctuates by 30–50%. The cost control problem is that the production cost of microbial inoculants is high (about 2000–5000 yuan per ton of liquid microbial inoculants), accounting for 30–50% of the operation and maintenance cost of large-scale projects.

It is necessary to promote life cycle assessment (LCA) and technical and economic analysis (TEA), which are the key links of technology from laboratory to large-scale engineering application, and also the weaknesses of current research. Future work must include systematic LCA and TEA research: LCA can systematically quantify the environmental impact of ‘cradle to grave’ (including the whole process of microbial agent production, carrier manufacturing, reactor construction, operation energy consumption, waste treatment, etc.), including carbon emissions, water consumption, ecotoxicity, and other indicators, and compare them with traditional physical and chemical technologies to objectively evaluate environmental sustainability advantages. TEA needs to accurately calculate investment and operating costs on a larger scale (such as 100,000 m3/h) to reveal the scale effect. The potential of new low-cost carriers (such as agricultural waste modification), in situ regeneration technology of microbial agents, and energy and resource recovery (such as biomass and sulfur) to reduce unit treatment costs is evaluated to provide a clear economic basis for investors and policy makers.

Probiotic waste gas treatment technology takes efficient microbial mineralization as the core advantage and realizes multi-scenario application through basic theoretical innovation and engineering optimization. In the future, it is necessary to break through the bottleneck of environmental adaptability and cost by relying on synthetic biology (strengthening bacterial tolerance), technology coupling (photocatalysis/electrochemical assistance), and a circular economy model (pollutant → resource conversion). Interdisciplinary collaboration and policy support will promote this technology to become a key support for ‘reducing pollution and carbon’ and help achieve the goal of ‘double carbon’. Although probiotic waste gas treatment technology has made significant progress, it still faces bottlenecks in complex environmental adaptability and cost control. In the future, it is necessary to promote technological breakthroughs through multidisciplinary integration.

Author Contributions

H.X.: supervision, conceptualization, methodology, investigation, and writing—review and editing; Y.S.: methodology, investigation, and writing; R.C.: investigation; X.L.: investigation and writing—review and editing; C.W.: writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

This article is a review article that does not involve research data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yang, J.; Zhao, X.; Wei, S.; Wang, P.; Yang, Y.; Zou, B.; Li, Y.; Song, L. Innovative advanced oxidation processes based on hydrodynamic cavitation for simultaneous desulfurization and denitration. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 505, 159254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedros, P.B.; Askari, O.; Metghalchi, H. Reduction of nitrous oxide emissions from biological nutrient removal processes by thermal decomposition. Water Res. 2016, 106, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Rahman, T.; Roy, P.; Bliss, Z.S.B.; Mohammad, A.; Corriero, A.C.; Patel, N.T.; Gupta, R. The impact of air quality on cardiovascular health: A state of the art review. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2024, 49, 102174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, W.; Vardoulakis, S.; Steinle, S.; Loh, M.; Johnston, H.J.; Precha, N.; Cherrie, J.W. A health impact assessment of long-term exposure to particulate air pollution in Thailand. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 055018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, J.; Agrawal, S.B.; Agrawal, M. Global trends of acidity in rainfall and its impact on plants and soil. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2023, 23, 398–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eceiza, I.; Aguirresarobe, R.; Barrio, A.; Fernández-Berridi, M.J.; Irusta, L. Ammonium polyphosphate-melamine synergies in thermal degradation and smoke toxicity of flexible polyurethane foams. Thermochim. Acta 2023, 726, 179554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Shi, M.; Jian, X.; Dong, L. Case report: Occupational poisoning incident from a leak of chloroacetyl chloride in Jinan, Shandong, China. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1215293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Zhu, Y.; Yuan, J.; Guo, X.; Zhang, Q. Advances in adsorption, absorption, and catalytic materials for VOCs generated in typical industries. Energies 2024, 17, 1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Biswas, B.; Hassan, M.; Naidu, R. Green adsorbents for environmental remediation: Synthesis methods, ecotoxicity, and reusability prospects. Processes 2024, 12, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Moukhtari, F.; Martin-Pozo, L.; Zafra-Gomez, A. Strategies based on the use of microorganisms for the elimination of pollutants with endocrine-disrupting activity in the environment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, A.D.V.; Damianovic, M.H.R.Z.; Torre, R.M. Assessment of aerobic-anoxic biotrickling filtration for the desulfurization of high-strength H2S streams from sugarcane vinasse fermentation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 489, 137696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, A.R.; Rahimpour, M.R.; Farsi, M. Efficient recycling and conversion of CO2 to methanol: Process design and environmental assessment. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2024, 202, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; He, W.; Shen, Y. Recyclable NiMnOx/NaF catalysts: Hydrogen generation via steam reforming of formaldehyde. Fuel 2023, 354, 129311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Iqbal, H.M.; Barceló, D. Persistence of pesticides-based contaminants in the environment and their effective degradation using laccase-assisted biocatalytic systems. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 695, 133896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swerdlow, R.H. Bioenergetics and metabolism: A bench to bedside perspective. J. Neurochem. 2016, 139, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Skinner, J.P.; Raderstorf, A.; Rittmann, B.E.; Delgado, A.G. Biotransforming the “Forever Chemicals”: Trends and Insights from Microbiological Studies on PFAS. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 5417–5430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulaki, E.G.; Tjamos, S.E. Bacillus species: Factories of plant protective volatile organic compounds. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 134, lxad037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saravanan, A.; Kumar, P.S.; Srinivasan, S.; Jeevanantham, S.; Kamalesh, R.; Karishma, S. Sustainable strategy on microbial fuel cell to treat the wastewater for the production of green energy. Chemosphere 2022, 290, 133295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanemaru, E.; Ichinose, F. Essential role of sulfide oxidation in brain health and neurological disorders. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 266, 108787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, C.; Xia, Y.; Liu, D.; Zhao, R.; Gao, R.; Liu, H.; Xun, L. Cupriavidus necator H16 uses flavocytochrome c sulfide dehydrogenase to oxidize self-produced and added sulfide. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e01610-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Directional bio-synthesis and bio-transformation technology using mixed microbial culture. Microb. Biotechnol. 2021, 15, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Sekhon, S.S.; Ban, Y.H.; Ahn, J.Y.; Ko, J.H.; Lee, L.; Kim, Y.H. Proteomic analysis of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) degradation and detoxification in Sphingobium chungbukense DJ77. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 26, 1943–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Márquez, A.; Loera-Corral, O.; Santacruz-Juárez, E.; Tlécuitl-Beristain, S.; García-Dávila, J.; Viniegra-González, G.; Sánchez, C. Biodegradation patterns of the endocrine disrupting pollutant di (2-ethyl hexyl) phthalate by Fusarium culmorum. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 170, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega-Martínez, P.; Nikkanen, L.; Wey, L.T.; Florencio, F.J.; Allahverdiyeva, Y.; Díaz-Troya, S. Glycogen synthesis prevents metabolic imbalance and disruption of photosynthetic electron transport from photosystem II during transition to photomixotrophy in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. New Phytol. 2024, 243, 162–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.J.; Zhang, W.; Lei, Q.; Chen, S.F.; Huang, Y.; Bhatt, K.; Zhou, X. Pseudomonas aeruginosa based concurrent degradation of beta-cypermethrin and metabolite 3-phenoxybenzaldehyde, and its bioremediation efficacy in contaminated soils. Environ. Res. 2023, 236, 116619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclerc, M.C.; Gorelsky, S.I.; Gabidullin, B.M.; Korobkov, I.; Baker, R.T. Selective Activation of Fluoroalkenes with N-Heterocyclic Carbenes: Synthesis of N-Heterocyclic Fluoroalkenes and Polyfluoroalkenyl Imidazolium Salts. Chem.—Eur. J. 2016, 22, 8063–8067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beloglazkina, E.K.; Ustynyuk, Y.A.; Nenajdenko, V.G. Pioneers and Influencers in Organometallic Chemistry: Alexander Nesmeyanov (1899–1980). Carbon and Hydrogen Are Good but What about the Other 100 Elements? Organometallics 2024, 43, 1625–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Wang, X.; Ding, Q.; Wu, J. C–H Bond Sulfonylation from Thianthrenium Salts and DABCO·(SO2) 2: Synthesis of 2-Sulfonylindoles. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 89, 9672–9680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, K.; Fan, Z.; Huang, T.; Gu, W.; Wang, G.; Liu, E.; Xu, G. Influence of increasing acclimation temperature on growth, digestion, antioxidant capacity, liver transcriptome and intestinal microflora of Ussruri whitefish Coregonus ussuriensis Berg. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2024, 151, 109667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gg, E.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, W.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, J. Harnessing L-Cysteine to enhance lyophilization tolerance in Lactiplantibacillus plantarum: Insights into cellular protection mechanisms. LWT 2024, 208, 116690. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Chen, B.; Zhang, M. Degradation kinetics of aromatic VOCs polluted wastewater by functional bacteria at laboratory scale. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Wu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, L.; Tian, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Z. A constant pH molecular dynamics and experimental study on the effect of different pH on the structure of urease from Sporosarcina pasteurii. J. Mol. Model. 2025, 31, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hu, S.; Sun, R.; Wu, Y.; Qiao, Z.; Wang, S.; Cui, C. Dissolved oxygen disturbs nitrate transformation by modifying microbial community, co-occurrence networks, and functional genes during aerobic-anoxic transition. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 790, 148245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuforiji, O.O.; Aboaba, O.O. Application of Candida valida as a protein supplement. J. Food Saf. 2010, 30, 969–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrawal, A.; Calabrese, S.; Herrmann, A.M.; Manzoni, S. Interacting bioenergetic and stoichiometric controls on microbial growth. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 859063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.; Oh, J.I. The RsfSR two-component system regulates SigF function by monitoring the state of the respiratory electron transport chain in Mycobacterium smegmatis. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 105764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posung, M.; Promkhatkaew, D.; Borg, J.; Tongta, A. Development of a modified serum-free medium for Vero cell cultures: Effects of protein hydrolysates, l-glutamine and SITE liquid media supplement on cell growth. Cytotechnology 2021, 73, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Hui, X.; Zhang, D.; Huang, Y.; Ma, W.; An, L.; Peng, S. The disposal of sulfur and oil-contained sludge using Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2022, 39, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, D.; Chen, Z.; Wei, Z. Diethyl phthalate removal in waste gas from plastic formulations by membrane biofilm reactor. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 114355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Raza, W.; Jiang, G.; Yi, Z.; Fields, B.; Greenrod, S.; Wei, Z. Bacterial volatile organic compounds attenuate pathogen virulence via evolutionary trade-offs. ISME J. 2023, 17, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamini; Sharma, R.; Punekar, N.S.; Phale, P.S. Carbaryl as a carbon and nitrogen source: An inducible methylamine metabolic pathway at the biochemical and molecular levels in Pseudomonas sp. strain C5pp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e01866-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, A. Removal of heavy metal ions from water and wastewaters by sulfur-containing precipitation agents. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2020, 231, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Dai, D.; Liao, Y.; Han, H.; Wu, J.; Ren, Z. Synthetic microbial consortia to enhance the biodegradation of compost odor by biotrickling filter. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 387, 129698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, D.; Ge, X.; Lin, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y. Biological conversion of methane to methanol at high H2S concentrations with an H2S-tolerant methanotrophic consortium. Renew. Energy 2023, 204, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, L.R.; Mora, M.; Van der Heyden, C.; Baeza, J.A.; Volcke, E.; Gabriel, D. Model-based analysis of feedback control strategies in aerobic biotrickling filters for biogas desulfurization. Processes 2021, 9, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbusinski, K.; Kalemba, K.; Kasperczyk, D.; Urbaniec, K.; Kozik, V. Biological methods for odor treatment–A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 152, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Zhong, S.; Chen, D.; Zeng, H.; Chen, Z.; Cen, C. Research on VOCs Treatment of Electrophoresis Coating Process. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 514, 052014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Lai, C.T. Biological treatment of mineral oil in a salty environment. Water Sci. Technol. 2000, 42, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luján, A.P.; Bhat, M.F.; Saravanan, T.; Poelarends, G.J. Exploring the Substrate Scope and Catalytic Promiscuity of Nitroreductase-Like Enzymes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2024, 366, 4679–4687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, B.G.; Merayo, N.; Millán, A.; Negro, C. Sustainable recovery of wastewater to be reused in cooling towers: Towards circular economy approach. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 41, 102064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czech, A.; Smolczyk, A.; Ognik, K.; Wlazło, Ł.; Nowakowicz-Dębek, B.; Kiesz, M. Effect of dietary supplementation with Yarrowia lipolytica or Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast and probiotic additives on haematological parameters and the gut microbiota in piglets. Res. Vet. Sci. 2018, 119, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Dong, A.; Xu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Lambo, M.T.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y. Regulatory effects of high concentrate diet synergistically fermented with cellulase and lactic acid bacteria: In vitro ruminal fermentation, methane production, and rumen microbiome. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2025, 319, 116194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzamic, A.M.; Mileski, K.S.; Ciric, A.D.; Ristic, M.S.; Sokovic, M.D.; Marin, P.D. Essential oil composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of essential oil and deodorized extracts of Helichrysum italicum (Roth) G. Don. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2019, 22, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, B.; Li, S.; Michel Jr, F.; Li, G.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, D.; Li, Y. Effects of mix ratio, moisture content and aeration rate on sulfur odor emissions during pig manure composting. Waste Manag. 2016, 56, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, C.; Yan, C.; Xue, Y.; Xu, Z.; Jin, T.; Liu, Q. Effects of exogenous microbial agents on soil nutrient and microbial community composition in greenhouse-derived vegetable straw composts. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H. Emissions of reduced sulfur compounds (RSC) as a landfill gas (LFG): A comparative study of young and old landfill facilities. Atmos. Environ. 2006, 40, 6567–6578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Han, M. Efficiency evaluation of commonly used methods to accelerate formaldehyde release and removal in households: A field measurement in bedroom. Build. Environ. 2025, 268, 112348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, R.; Niu, Y.; Du, X.; Gao, C.; Zhang, T.; Zhu, R.; Wang, Y. New insights into the effect of H2S stress on CH4 oxidation in landfill cover soils from the CH4-derived carbon allocation and its microbial mechanism. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 107363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Shi, X.X.; Li, J.F.; Xie, J.; Liu, X.C.; Liu, L.S.; Wang, Z.Y. Experimental study on removal of hydrogen sulfide gas by spray and bubble blowing: A comparative study. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 185, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, R.; Chen, J.; Zhang, F.; Linhardt, R.J.; Zhong, W. Biotechnology progress for removal of indoor gaseous formaldehyde. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 3715–3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanongnuch, R.; Abubackar, H.N.; Keskin, T.; Gungormusler, M.; Duman, G.; Aggarwal, A.; Rene, E.R. Bioprocesses for resource recovery from waste gases: Current trends and industrial applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 156, 111926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chi, M.; Tian, H.; Chen, X.; Li, T. Use of dewatered sludge and fly ash to prepare new fillers: Application and evaluation in wastewater treatment. Biochem. Eng. J. 2023, 197, 108988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liu, Y.; Xu, X.; Sun, M.; Jiang, M.; Xue, G.; Liu, Z. How does iron facilitate the aerated biofilter for tertiary simultaneous nutrient and refractory organics removal from real dyeing wastewater? Water Res. 2019, 148, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Huang, Q.; Ye, Q.; Chen, Z.; Li, B.; Wang, J. Thermophilic biotrickling filtration of gas–phase trimethylamine. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2015, 6, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Li, J.; Ye, G.; Sun, D.; Sun, G.; Zeng, X.; Xu, J.; Liang, S. Performances of two biotrickling filters in treating H2S-containing waste gases and analysis of corresponding bacterial communities by pyrosequencing. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 95, 1633–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Tio, W.; Sun, D.D. A facile method for the fast and accurate selection of a UF membrane for membrane bioreactors. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2021, 7, 2054–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubackar, H.N.; Veiga, M.C.; Kennes, C. Production of acids and alcohols from syngas in a two-stage continuous fermentation process. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 253, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbajo, J.; Quintanilla, A.; Casas, J.A. Characterization of the gas effluent in the treatment of nitrogen containing pollutants in water by Fenton process. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 221, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Chen, C.; Chen, W.; Jiang, J.; Chen, B.; Zheng, F. Effective immobilization of Bacillus subtilis in chitosan-sodium alginate composite carrier for ammonia removal from anaerobically digested swine wastewater. Chemosphere 2021, 284, 131266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Le, H.T.N.; Poh, L.H.; Quek, S.T.; Zhang, M.H. Effect of high strain rate on compressive behavior of strain-hardening cement composite in comparison to that of ordinary fiber-reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 136, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shao, J.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, S.; Chen, H. Molecular simulation of different VOCs adsorption on nitrogen-doped biochar. Fuel 2024, 372, 132127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Cao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, X.; Ahmed, M.B.; Lowry, G.V. Distributing sulfidized nanoscale zerovalent iron onto phosphorus-functionalized biochar for enhanced removal of antibiotic florfenicol. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 359, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakielski, P.; Rinoldi, C.; Pruchniewski, M.; Pawłowska, S.; Gazińska, M.; Strojny, B.; Pierini, F. Laser-Assisted Fabrication of Injectable Nanofibrous Cell Carriers. Small 2022, 18, 2104971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Miao, Y.; Yu, D.; Qiu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wang, X. Culturing partial denitrification biofilm in side stream incubator with ordinary activated sludge as inoculum: One step closer to mainstream Anammox upgrade. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 347, 126679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sha, H.; Cai, L.; Xie, G. Coupled biotreatment of waste gas containing H2S and VOCs in a compound biofilter. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 301, 012121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Liu, G.H.; Ma, Y.; Xu, X.; Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, H. A pilot-scale study on start-up and stable operation of mainstream partial nitrification-anammox biofilter process based on online pH-DO linkage control. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 350, 1035–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonsdale, W.; Shylendra, S.P.; Wajrak, M.; Alameh, K. Application of all solid-state 3D printed pH sensor to beverage samples using matrix matched standard. Talanta 2019, 196, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaitonde, A.U.; Weibel, J.A.; Marconnet, A.M. Thermal metrology for deeply buried low-thermal-resistance interfaces. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2025, 241, 126591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).