Abstract

Building sustainable cities and communities is an important part of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. The construction and development of Urban Governance Communities is a Chinese program to respond to this goal. Drawing upon the extant national cases of innovative social governance spearheaded by People’s Daily and analogous organizations, this study elucidates the developmental process and continuous operational mechanism of urban governance community through the grounded theory (GT) approach. The explanatory framework under consideration comprises three aspects. First, it contains the precise identification and typology of traditional governance dilemmas. Secondly, it refines the core element system of “Coupling Dilemma-Cracking Path-Dependent Tools” of urban governance communities. The third objective is to provide a synopsis of the operational and developmental model of the Urban Governance Communities, which is predicated on co-construction, co-governance, and co-sharing. This model of urban governance can be selectively applied in the light of the differentiated resource endowments of the location, thus providing an operational and realistic sample for building sustainable cities and communities.

1. Introduction

Building sustainable cities and communities has emerged as a cornerstone of the global agenda for sustainable development, prominently articulated in Goal 11 of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). As cities worldwide confront mounting pressures from rapid urbanization, social fragmentation, and environmental uncertainty, the pursuit of collaborative urban governance has garnered renewed scholarly and policy attention [1]. The concept of urban governance has evolved beyond the confines of traditional bureaucratic structures, encompassing a diverse array of actors, institutions, and networks across the public, private, and civic domains [2]. This transition has given rise to the notion of cooperative urban governance, which emphasizes co-construction and other concepts of cooperativeness as core logics for sustainable urban transformation [3]. Despite the prevalence of literature in the field of international studies that has placed significant emphasis on the role of institutional diversity and networked coordination in the context of urban governance, there remains a dearth of systematic studies that have thoroughly investigated the dynamic processes involved in the establishment and longevity of governance communities within non-Western contexts.

China, as a significant actor in the developing world, has amassed a wealth of experience in the realm of cooperative urban governance. In recent decades, China has provided a distinctive empirical context for the study of urban governance transformations. Chinese cities have been motivated by their robust state capacity and the mounting emphasis on innovation in social governance to experiment with a variety of collaborative governance models that exceed conventional administrative boundaries. In response to the intricacies of contemporary social challenges, community-based governance platforms, party-led grid systems, and digital participation mechanisms have seen a marked proliferation across urban centers. However, as some academics emphasize, successful governance innovations require more than functional design [4]; they depend on adaptive mechanisms that couple governance dilemmas with localized solutions and supporting tools [5]. The Chinese context, characterized by its hybrid state-society relations and robust policy diffusion mechanisms, offers a conducive environment for the development of grounded theories that explore the initiation, stabilization, and scaling of urban governance communities [6]. We would like to document the experience and wisdom accumulated by developing countries, represented by China, in social governance in a globalized enterprise. This will fill the research gap of “the specific governance process of highly organized countries”.

A useful framework to examine governance may be found by considering the ongoing dialogue between Eastern and Western civilizations. The evolving scholarship on urban governance highlights three key frontiers of inquiry that are particularly relevant to sustainable urban development [7]. Firstly, an increasing number of studies have underscored the importance of multi-level and polycentric governance arrangements that span local, regional, and global scales [8]. Such arrangements are considered essential for managing transboundary issues like climate adaptation and risk governance, where cities act as both policy implementers and innovation hubs [9]. Secondly, there is an increasing focus on the role of experimentation and social innovation in urban governance, acknowledging that collaborative approaches frequently emerge from iterative processes of policy trial, error, and refinement [10]. Thirdly, recent research on smart cities highlights the transformative potential of digital tools in enhancing transparency, accountability, and public participation, although concerns persist regarding the risks of technocratic governance and social exclusion [11].

Despite the numerous advancements in the field, considerable gaps in knowledge persist. A significant proportion of extant literature focuses on Western democracies, where governance reforms are often shaped by liberal institutional frameworks and well-established civil society structures [12]. The mechanisms through which collaborative governance logic can become established and maintained in contexts characterized by state direction and active encouragement of localized experimentation remain to be fully elucidated. China offers a compelling case study for examining these dynamics, as it integrates top-down policy directives with grassroots initiatives in areas such as grid governance, environmental co-management, and digital civic engagement [6]. The present study aims to address this lacuna in research by theorizing the construction and persistence of urban governance communities in this context. In doing so, it seeks to contribute to the comparative understanding of sustainable city-building.

2. Literature Review

The study of urban governance has historically been a focal point of inquiry in the fields of political science and urban studies. Early research in this area was primarily concerned with the institutional arrangements and political regimes that shape decision-making authority. Foundational works by Pierre [13] and DiGaetano and Strom [14] provided comparative frameworks for understanding how governance models vary across contexts, emphasizing the influence of institutional structures and political dynamics. Subsequent studies, including those by Bernt [15] and Davies [16], built upon these foundations by analyzing redevelopment partnerships and regeneration initiatives. These studies underscored the pivotal role of coalition-building among government agencies, market actors, and civil society organizations. In more recent scholarship, scholars such as Patterson [17] and Frantzeskaki [18] have reconceptualized urban governance as a dynamic and adaptive process. Their work emphasizes institutional innovation, experimental governance, and iterative learning as mechanisms for addressing the increasing complexity and uncertainty of urban challenges.

Concurrently, a body of research has emerged that underscores the significance of participation and co-production in achieving sustainable and inclusive governance. Moulaert et al. [7] and Rosol [19] investigated participatory greening initiatives and social innovation, illustrating the potential of citizen engagement to produce more equitable outcomes. Sánchez-Hernández [20] as well as Vara-Sanchez et al. [21] documented how participatory structures can empower local communities. In contrast, Wu [22] and Benson and Walker [23] highlighted grassroots and refugee-led organizations as important actors in urban decision-making. The collective findings of these studies indicate a transition from hierarchical, state-centric governance models to distributed frameworks, wherein a diverse array of stakeholders assume responsibility for policy design and implementation. Arguments of a similar nature have been posited by Keivani et al. [24], who described co-creation processes as being essential to enhancing the legitimacy and effectiveness of urban governance.

Another major strand of research pertains to environmental and resource governance. Li et al. [25] explored the role of environmental non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in collective action, while Nastar [26] and Sajor and Ongsakul [27] examined equity and power relations in urban water regimes [28]. Alba et al. [29] and Egusquiza et al. [30] developed innovative models for collaborative water management, whereas Sutherland et al. [31] and Eakin et al. [32] emphasized the importance of inclusive, multi-actor approaches to green space planning. Park and Youn [33] presented findings from participatory forest policy-making in Korea, emphasizing the advantages of community participation in environmental governance.

As metropolitan areas grapple with an expanding array of intricate issues, scholars have directed an increasing amount of attention toward multi-level and networked governance systems. Lee and Koski [34] and Heinrichs et al. [35] analyzed how cities are emerging as proactive actors in polycentric climate governance systems. Hofstad et al. [36] and van Bortel [37] examined collaborative planning practices in European cities. Patterson and Huitema further highlighted experimentation and institutional learning as key processes enabling urban governance systems to adapt to dynamic and uncertain conditions [17].

The theme of adaptation and resilience is particularly prominent in studies concerned with climate risks and socio-economic volatility. Bos and Brown [9], Rijke et al. [12], and Wu et al. [38] conducted a series of investigations into governance reforms designed to enhance adaptability in the context of water management and informal urban environments. Asadzadeh et al. [39] and Garschagen [40] examined institutional conditions for effective disaster risk governance, while Keith et al. [41] analyzed urban heat adaptation measures at the local planning level. As Schramm et al. [42] and Ehnert [43] have demonstrated, experimental and iterative approaches are instrumental in fostering systemic resilience. These researchers further emphasize the value of learning-oriented governance mechanisms.

If we focus on more cutting-edge research, it is not difficult to find several new features of current research: (1) From “participation” to co-production and collaborative governance. In recent years, research on governance has placed more emphasis on the shift from “simple participation” to “polycentricity”. Ariane Goetz explores the possibilities of self-organization of farmer communities from the perspective of agroecological practices, offering the wisdom of “polycentric” solutions to governance processes [44]. At the same time, while “polycentricity” as a solution is good for grasping governance sectors at the macro level, the differences in the size of the role played by individual centers can easily be overlooked. Therefore, collaborative governance urgently needs to pay attention to the differences in multiple subjects in urban research [45]. (2) Digital participation, platforms, and data-rich urbanism. Post-pandemic urban governance accelerated e-participation and platformized engagement. Evidence from Cities shows adoption barriers and drivers for municipal tools, urging municipalities to move from “consultation portals” to designs that clarify how inputs affect decisions [46]. At the same time, rapid advances in machine learning and artificial intelligence tools will provide a very important real-world contribution to the expansion and updating of community resources [47]. There is no doubt that this contributes to the resilience and sustainability of urban communities [48]. (3) Urban commons, community resilience, and CBOs. Work on the urban commons revisits and extends Ostrom-inspired design principles to urban settings, proposing updated guidance for sustainable commoning under contemporary inequalities and smart-city conditions [49]. Studies of community-based organizations (CBOs) in informal settlements frame them as adaptive governance nodes that build resilience through relational capacities and bridging ties, yet caution about over-burdening communities without resource devolution [50]. Additionally, Public-health and disaster-risk reviews reiterate the importance of locally tailored participation and multi-scalar coordination to convert engagement into resilience outcomes [51].

A synthesis of these disparate strands of research reveals several salient trends. Firstly, a discernible transition is evident from static, government-centered models to dynamic frameworks that accentuate experimentation, institutional innovation, and adaptive learning. Secondly, participatory and inclusive approaches are increasingly recognized as essential for legitimate and effective governance, with greater involvement of grassroots actors, marginalized groups, and community organizations. Thirdly, digital technologies and data-driven decision-making are transforming governance practices, creating both opportunities for efficiency and transparency as well as concerns regarding equity and power imbalances [52].

Notwithstanding these advances, significant gaps persist. A significant number of studies have been conducted on the subject; however, these studies have provided limited insights into the long-term sustainability and institutionalization of participatory innovations. Furthermore, the scalability of experimental governance models remains insufficiently explored. Furthermore, non-Western contexts characterized by robust state involvement, such as China, have received comparatively less attention, thereby leaving open significant questions regarding the interaction between top-down initiatives and grassroots participation. Addressing these gaps is imperative for developing a more comprehensive understanding of how urban governance communities can be constructed and sustained in diverse institutional and cultural settings.

3. Methodology

The prevailing design of extant research on urban governance communities is predominantly characterized by the following features: (1) Single-case interpretation. These studies underscore the pivotal role that a specific unit within the urban governance community plays. While this line of research has successfully delved into the Chinese context from a micro perspective, deciphering the governance experience, the distinctiveness, replicability, and generalizability of the cases remain subjects of ongoing discourse. (2) Discursive examination. These studies underscore the necessity of multi-subject cooperation in urban governance within a specific theoretical framework or conceptual model. They further explore the “contingency” of urban governance in scenarios where the “reality” deviates from the anticipated construction. Therefore, there is an urgent need to explore multiple case studies that focus on the universality of urban governance and community building. In order to proceed with this research, it is necessary to find a path that harmonizes discursive subjectivity with theoretical objectivity.

3.1. Research Method

The concept of grounded theory was initially put forward by Glaser and Strauss in 1967. This qualitative research methodology involves the systematic analysis of information and data to develop theories, particularly in the context of process-based problems [53]. The utilization of this method is particularly well-suited for the interpretation of process-related issues. It identifies dynamic processes and patterns of change by means of a systematic summary of complex and detailed social phenomena. In practice, the grounded theory research method involves the following steps: first, the collected information is broken up; second, it jumps out of the established theoretical framework; third, new concepts are given to the original information; and fourth, the information is recombined in other ways [54]. Ultimately, the method draws the final conclusions from the layers of generalization and distillation. Concurrently, memos are meticulously prepared to encapsulate analytical insights that subsequently inform the development of the core category, a pivotal concept for integrating emerging theory [55].

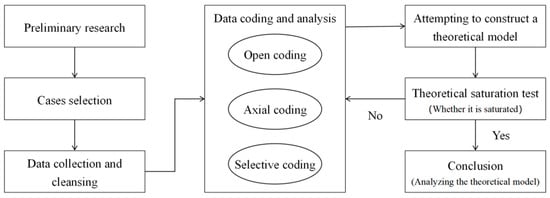

Figure 1 illustrates the procedure for applying the grounded theory approach in this study. A sequential approach is employed, whereby the following coding methods are applied: open coding, axial coding, and selective coding. Pre-research and case selection are undertaken with a focus on balancing factors, including geographic location. The factors of geographic location and degree of urban development were balanced by pre-research and case selection. Data collection and cleansing entailed the integration of primary and secondary sources, with a focus on source corroboration. Open coding, axial coding, and selective coding were employed to emphasize information, respectively. Open coding, axial coding, and selective coding focus on the breadth of information, the refinement and classification of concepts, and the exploration of the intrinsic relationship between concepts, respectively. Theoretical saturation testing examines whether the constructed theories are saturated or not.

Figure 1.

The logical schematic of grounded theory research.

3.2. Data Sources and Sample Selection

In grounded theory, the theoretical sampling link necessitates that the research object be both representative and authoritative. In recent years, the implementation of social governance practices has yielded a substantial body of theoretical material for research in the domain of urban governance. In this study, we comprehensively consider the richness of research materials, the empirical nature of research subjects, and the generalizability of research conclusions. After a thorough examination of the available cases, a total of 12 cases were selected for further analysis. These cases hailed from China’s Innovative Social Governance Cases, a prominent Chinese multilingual news website, and were led by People’s Daily Online in collaboration with other organizations. The selection process involved a meticulous evaluation of the cases, resulting in the identification of 8 exceptional cases and 4 noteworthy cases. The following principles guided the selection of the sample:

(1) Authoritativeness. China’s Innovative Social Governance Cases Selection is a joint initiative sponsored by People’s Daily Online and the Department of Social and Ecological Civilization of China’s National School of Administration, among other entities. The selection process involved a series of rigorous evaluations, including self-declaration, network voting, and comprehensive examination by experts in the field. The selection index system comprises six evaluation level 1 indexes and 15 evaluation level 2 indexes, encompassing governance subject, governance method, innovation features, governance effect, governance impact, public participation, and related domains. The aforementioned principles of openness, fairness, and impartiality serve as the foundation for this approach. Consequently, it possesses considerable authority. (2) Representativeness. China’s conventional models of social governance are derived from cases that have been declared by localities. These cases encompass a diverse array of provinces and cities, spanning the eastern, central, and western regions of the country. The cases encompass a wide range of urban governance domains, including the governance of social organizations, participatory community governance, and Internet governance. Previously, 10 exceptional cases and 20 noteworthy cases were selected for China’s innovative social governance cases. In this study, 8 exceptional cases and 4 noteworthy cases were selected for further analysis. These cases were selected based on the principles of balanced case characteristics and geographical balance. (3) Timeliness. The use of cases selected in recent years reflects both the efforts made by developing countries in realizing the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Concurrently, it offers a visual representation of the novel circumstances, requisites, and challenges pertinent to contemporary urban governance.

3.3. Data Collection Process and Case Presentations

To enrich the research material, the triangulation method was employed to obtain textual information from multiple sources. This method was used to construct a library of information that can be used to develop a theory. With regard to the data collection process, this study draws from two primary sources. One such source is internet sources, which are considered secondary sources. The aforementioned documents primarily consist of government portals in the region where the case is situated, third-party media reports, and institutional provisions of local policies and regulations, amounting to approximately 477,000 words in total. The second method is the analysis of interview data (primary sources), which is obtained through a combination of online and offline interviews with relevant residents of the location. Concurrently, the data obtained through the administration of satisfaction questionnaires to the affected residents (comprising approximately 612,000 words) was also collected. Furthermore, to ensure that the core categories refined by the rooted approach achieve optimal theoretical saturation, the study randomly selected four cases among the unselected exceptional and noteworthy cases for theoretical saturation testing, totaling approximately 98,000 words.

Table 1 offers a concise overview of the 12 selected cases. The case code consists of capital English letters and Arabic numerals, the meaning of which is the order of the provinces (municipalities directly under the central government) and the code of the case group, corresponding to Chongqing—CQ, Sichuan—SC, Gansu—GS, Zhejiang—ZJ, Guangdong—GD, Jiangsu—JS, Shandong—SD, Hunan—HN, and Fujian—FJ. The provinces selected for the cases include both Guangdong Province, which is the foremost province in China with the highest level of economic development, and Jiangsu Province. Concurrently, Gansu Province exhibits a comparatively underdeveloped economic profile. Furthermore, the geographical distribution of the cases encompasses diverse locations in both eastern and western China. The designation “Case number” refers to the categorization of cases, including exceptional cases and noteworthy cases, as published on the official website of the People’s Daily. The sequence of cases is structured as follows: a total of ten exceptional cases are digitized as 01 to 10, and a total of 20 noteworthy cases are digitized as 01–20.

Table 1.

Brief description of selected cases.

4. Result Analysis

In accordance with the previously delineated logical process of grounded theory in this study, we undertook open coding, axial coding, and selective coding of pertinent news reports, questionnaires, and interview materials in a sequential, step-by-step manner. Following the initial acquisition of a system of core elements of urban governance communities, a theoretical saturation test was conducted. Subsequently, an effort was made to deepen our understanding and provide a more comprehensive explanation of the theoretical model of urban governance communities.

4.1. Open Coding

Open coding is a process of re-editing and combining information obtained through multiple sources, such as data collection and interview transcripts. In this process, repetitive, intersectional, and ambiguous discourses are eliminated. We summarize and organize the original utterances to a certain extent, and finally form initial concepts and categories. By further examining the 12 typical cases in the entire governance process, and ultimately comparing and organizing the raw utterances, 90 initial concepts are formed. Each initial concept corresponds to multiple original statements (i.e., the generalized concepts are corroborated by multiple materials to be viable rather than one-sided). Due to limitations in the available space, the 36 initial concepts and 12 categorized concepts developed during the open coding process are presented. These concepts are exemplified by dilemmas and problems encountered in the governance process. An illustration of open coding is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Example of an open coding process.

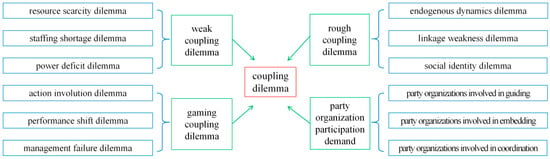

Taking the dilemmas and problems faced in the process of urban governance as an example, after the collation of open coding, it can be seen that the original statements were gradually integrated into 36 Initial concepts and then merged and summarized into 12 the concept of categorization. They are resource scarcity dilemma, staffing shortage dilemma, power deficit dilemma, endogenous dynamics dilemma, linkage weakness dilemma, social identity dilemma, action involution dilemma, performance shift dilemma, management failure dilemma, party organizations involved in guiding, party organizations involved in embedding, and party organizations involved in coordination.

4.2. Axial Coding

Axial coding aims to uncover the features of the concept of categorization and their interrelationships, and then compile them into clusters with differential characteristics. Taking the problem end as an example, the 12 concepts of categorization are classified into 4 major categories, which are weak coupling dilemma, rough coupling dilemma, gaming coupling dilemma and party organization participation demand. Figure 2 shows the main categories formed by axial coding.

Figure 2.

Main categories formed by axial coding.

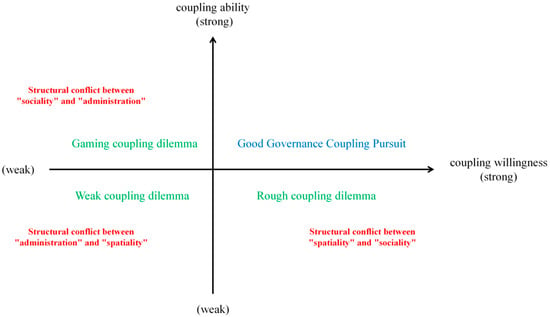

This study diverges from the conventional characterization of the challenges confronting urban governance by introducing the concept of “coupling” into the analytical process. This innovation entails the integration of the theory of embedded governance, offering a novel approach to understanding urban governance issues. The concept of “coupling” was originally developed within the domain of natural sciences, finding extensive application in disciplines such as communication engineering and software engineering. Subsequently, the term has been progressively expanded to encompass management, sociology, and other disciplines, thereby facilitating the description and explanation of the interrelationships between various subjects within the domain of management. Embedded governance is characterized by an emphasis on the internal relationship between the embedded subject and object, as well as the mechanisms of embedding. This focus, to a certain extent, overlooks the fact that the characteristics of “spatiality,” “administration,” “sociality,” and others present a unique opportunity to comprehend the intricacies of urban governance. These characteristics offer varied perspectives that facilitate a more nuanced understanding of the urban governance dilemma. In this study, we examine the issues that emerge from the interactions between the aforementioned characteristics. We develop a spatial coordinate system based on the concept of the “coupling effect,” with coupling willingness serving as the horizontal coordinate and coupling ability as the vertical coordinate, as illustrated in Figure 3. The major categories obtained by axial coding are subsequently analyzed.

Figure 3.

Spatial coordinate map of coupling dilemma classification.

Weak coupling dilemma (structural conflict between “administration” vs. “spatiality”) is generally externally characterized by weak governance resources. Urban communities confronted with such challenges are frequently situated in regions characterized by a comparatively limited natural or social resource base. On one hand, these communities may be characterized by a scarcity of subsistence resources, such as land, rivers, climate, and crops. On the other hand, they may be characterized by a scarcity of social resources, such as labor, markets, capital, management, and technology. Inadequate natural and social resources can readily result in the incapacity of formal governance entities to execute their duties. The challenges of “inability to act” and “inability to act competently” are salient, manifesting as a paucity of governance resources that serves as the foundation for community, party, and grassroots self-governance organizations. That is to say, community party organizations and grassroots self-governance organizations face challenges in implementing governance actions due to a lack of governance resources. This phenomenon is also evident in the underutilization of resources, which hinders the fulfillment of developmental objectives. Furthermore, the attainment of security goals is hindered by the limited capacity of resources to contribute to these objectives.

Rough coupling dilemma (structural conflict between “spatiality” and “sociality”) is generally manifested externally in the form of weak, fragmented, or simple cooperation among governance actors. The conflict between “spatiality” and “sociality” of the community is interpreted as a conflict between “spatiality” and “sociality” of the community. In the context of this coupling dilemma, there may be relative strengths and weaknesses in governance resources; however, these resources do not represent the primary factor constraining governance and development. According to the “administration” maneuvering, each participating governance subject initially exhibits a willingness to collaborate in governance. However, due to the absence of top-level institutional design and the cultivation of grassroots governance capacity, the “administration” governance subject, as the “administration,” is not the primary factor constraining its governance and development. However, due to the absence of a comprehensive institutional framework and the promotion of grassroots governance capacity, community party organizations and community self-governance organizations, as the predominant “administration” forces, are susceptible to the phenomenon of “bowling alone,” as proposed by Robert Patternan. This suggests a potential erosion of civil society’s resilience. The following factors contribute to the challenges associated with the implementation of “sociality” forces: firstly, the identity rooted in “spatiality” is inadequate; secondly, the endogenous motivation rooted in “sociality” is inadequate; thirdly, the “administrative” power rooted in “sociality” is inadequate; and fourthly, the “administration” power rooted in “sociality” is inadequate. The inadequate linkage capacity, attributed to the “administrative nature” of the system, results in the convergence of multiple factors that impede the development of refined synergy, thereby hindering the pursuit of effective governance within the context of rough coupling.

Gaming coupling dilemma (structural conflict between “sociality” and “administration”) is generally manifested externally in the alienation and exclusion of the concept of governance and leads to the failure of governance behavior, and internally interpreted as the conflict between “sociality” and “administration” aspects of the community. The crux of the dilemma posed by this type of coupling is no longer the question of “how big is the cake,” but rather, “how should the cake be shared?” In such circumstances, the “sociality” game dilemma is exemplified by non-community party organizations and non-grassroots self-governing organizations of the governance subject of the governance resources of the exclusionary mentality, neighbor avoidance mentality, and related behaviors. The “administration” game dilemma manifests itself in the exclusionary behaviors of community party organizations and grassroots autonomous organizations. Examples of such behaviors include conservative sharing (only sharing basic resources), alienated guidance (guidance of governance behaviors for private purposes), and replicative guidance (guidance of governance behaviors for private purposes) for the sake of power exercise and personal promotion. The phenomenon of resource sharing among individuals or groups without the intention of collective benefit is a salient example of the aforementioned issues. Similarly, the practice of alienating guidance, defined as the utilization of governance behaviors for personal gain, is a concern that merits attention. The act of copying and relocating governance practices from one region to another without considering the unique characteristics of the local context is another area of concern. The “sociality” and “administration” exclusionary behaviors are susceptible to management failures, and gaming behaviors can exacerbate resource endowment and governance capacity weaknesses. The effectiveness of governance tends to diminish at the margin.

4.3. Selective Coding

Selective coding is the process of distilling core categories that encompass all the main categories developed by exploring their intrinsic relationships. By referring to the open coding and axial coding steps of “Coupling Dilemma” to code the original statements (as shown in Table 3), we can identify three categories: participant subjects (“regime organizations”, “social organizations” and “civil organizations”); interaction relations (“street and community”, “community and community”, and “community and residents”); and means of application (controlling, negotiating and guiding). These three categories are based on the major category, “Cracking Path”. Additionally, we can derive a core category based on the three scoping concepts of policy-based tools (“supply-driven”, “demand-pulled” and “environment-influenced”), society-based tools (“value-guided”, “society-regulated” and “honor-motivated”), and market-based tools (“market-barred”, “market-accessed” and “market-expanded”)—“Dependent Tools”.

Table 3.

System of core elements through selective coding.

4.4. Theoretical Saturation Test

The theory saturation test is a test for saturation of concepts and theoretical prototypes that have been developed when the researcher believes that no new categorized concepts can be developed on the basis of the available information. In the context of practical research, the attainment of complete and uncontested theory saturation is regarded as a desirable state. However, as long as the structural relationships between categories are clarified and no new categories and concepts will appear in the sample data, the study can be considered to have considerable theoretical saturation. In order to ensure the reliability of the study, two exceptional cases (the case of Dunhua City, Yanbian Prefecture, Jilin Province and the case of Qingyang District, Chengdu City, Sichuan Province) were set aside and two noteworthy cases (the case of Kunming City, Yunnan Province and the case of Zibo Hi-Tech District, Shandong Province) were taken as triangulated materials. The theoretical saturation test of the aforementioned materials through Nvivo 14 software demonstrates two key findings. First, the coding process identified no novel concepts that were not already present in the various categories previously delineated. Second, the concepts that emerged during the coding process were able to adequately explain the reserved cases. The findings indicate that the preliminary concepts, primary categories, and secondary categories derived from the study are both comprehensive and lucid. Therefore, it can be determined that the system of core elements developed in this study through the grounded theory (GT) is theoretically saturated.

5. Discussion

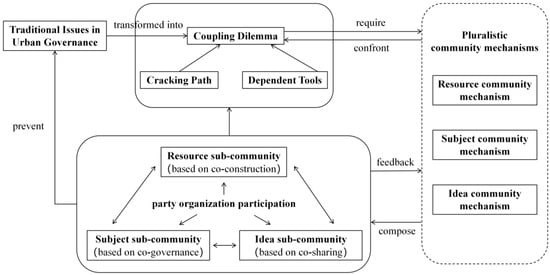

5.1. Pluralistic Community Mechanisms

This study further analyzes the aforementioned system of core elements obtained through the grounded theory approach (GT). The analysis reveals the emergence of diverse “community mechanisms” during the course of practice, namely, resource community mechanism, subject community mechanism, and idea community mechanism.

“Resource community mechanism” is a strategy employed in the context of urban governance to address issues of resource scarcity or inefficiency in the utilization of human, material, financial, and other resources. This mechanism aims to promote the proliferation of resources through the integration and enhancement of existing resources, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of urban governance. Externally, the mechanism of resource community will be non-unit administrative divisions, which will provide conceptual and practical meaning to the pursuit of common interests (the goal of good governance). Differentiated resource endowments can then compensate for each other, and gradually build up a mutually beneficial and win-win cooperation network. This network will form a community of community governance sub-model of “honor and disgrace.” This is an internal matter. The resource community mechanism is designed to fully mobilize the internal governance resources of the city, thereby realizing the Pareto improvement of internal resources.

“Subject community mechanism” refers to the mechanism of re-engineering the interaction of multiple subjects within the framework of urban governance by constructing compatible interests through the transformation and linkage of common interests among multiple subjects such as regime organizations, social organizations, market organizations, civil organizations and residents in the process of urban governance. Subject community mechanism is a “vertical and horizontal” mechanism for responding to interests. With respect to vertical relations, the district government is positioned at the top of the mechanism, followed by government agencies (street offices), community residents’ committees (and community political party organizations), and finally, residents. In another configuration, the district government is once again at the top of the mechanism, followed by government agencies (street offices), community residents’ committees (and community political party organizations), and residents. On one hand, there is the top-down control and guidance of “district government-government agencies (street offices)-community residents’ committees (and community political party organizations)-residents.” Conversely, it employs a bottom-up approach to feedback and negotiation, wherein “residents articulate their demands, the executive level receives them, the management level transforms them, and the decision-making level responds to them.” The relationship is characterized by a horizontal “block” configuration. On one hand, the official forces adhere to the “supply-oriented” approach, thereby ensuring the active collaboration of the departments responsible for justice, public security, letters and visits, environmental protection, and other aspects of urban governance. This collaborative effort is intended to prevent the phenomenon of “bystanders in governance.” This approach effectively prevents the phenomenon of “bystanders in governance.” Conversely, social forces adhere to a “demand orientation,” prompting social organizations, market-based entities, civil society organizations, the masses, and other subjects to address the needs of urban governance and community services. These actors have been observed to extend their spontaneous actions to the end of the demand and fill the blank areas of the official forces in governance, and the introduction of market-oriented and assessment mechanisms promotes the long-term maintenance of governance effectiveness.

“Idea Community Mechanism” is a mechanism for digging deeper and selectively discarding ideas about urban governance, community belonging, and community integration. The mechanisms encompass not only the attitudes and views of various units and subjects within the city on the actions and practices of urban governance, but also the logical concepts of external forces that may have an impact on the theories, actions, and effectiveness of community governance. This mechanism reflects the predominant viewpoints of developing countries, as represented by China, on the “community” of developed countries and Western academics. It combines with the actual situation of the country itself, thereby overcoming the limitation of treating the community as merely an administrative division. The mechanism of community of ideas has shown positive effects in the areas of conflict and dispute resolution, improvement of community services, formation of a common order, and enhancement of moral literacy. The conceptual community mechanism has demonstrated its positive role in the resolution of conflicts and disputes, the improvement of community services, the formation of a common order, and the enhancement of moral quality.

5.2. Theoretical Model of Urban Governance Communities

While the pluralistic community mechanisms described above can be referenced as relatively independent mechanisms, they lack an appropriate theoretical model to integrate them. This phenomenon also underscores the challenge of replicating and generalizing a single mechanism in practical applications. Consequently, there is a necessity to integrate the aforementioned mechanisms into a well-established theoretical model. As illustrated in Figure 4, the constructed “urban governance communities” is predicated on a comprehensive framework.

Figure 4.

Overall framework for “Urban Governance Communities”.

5.2.1. Party Organization Participation as an Opportunity to Build Institutional Standards for “Compliance by People”

First is party organizations involved in guiding. In practice, problems affecting the stability of urban communities are often manifested in such issues as law and order, disputes, environmental protection, neighborhood incidents and small-scale group incidents. Community political party organizations should fulfill their role by paying close attention to specific demographic groups within the community, such as those experiencing low income, and providing comprehensive guidance to facilitate their integration into the community workforce. This approach would ensure adherence to all community rules and regulations. Secondly, party organizations involved in embedding. Community political party organizations should be closely embedded in community service initiatives. This initiative is not driven by partisan interests; rather, it serves as a conduit for party organizations to demonstrate their commitment to the residents and the significance of the party’s role in various services. Concurrently, upon the augmentation of this embeddedness, it is anticipated that other political party organizations will be motivated to exert a favorable influence on the community. This process entails the translation of political party interests into tangible actions that ultimately benefit the local community. Thirdly, party organizations involved in coordination. This coordination is exemplified by the strategic management of inter-group conflict by political party organizations, which utilize proactive risk mitigation strategies to avert potential tensions. Concurrently, the healthy competition between party organizations in terms of service provision to residents has been observed to engender a process of self-reflection amongst community party organizations with regard to their own shortcomings, whilst concurrently promoting consultation amongst them.

5.2.2. Building Resource Sub-Community of “Everyone Realizing Their Duties” Based on Co-Construction

The concept of “tools of governance” has evolved from “tools of government” and has been reintroduced to mean “shared rights to social governance”. The concept of co-construction underscores two distinct yet interconnected facets. Firstly, it acknowledges the heterogeneity of tools, emphasizing the existence of a multitude of tools and, concomitantly, the plurality of “hands” that utilize these tools. In essence, policy-based tools are utilized to reinvigorate existing resources, which are predominantly employed by governmental entities and other formal bodies. These instruments characteristically exhibit qualities of immediacy and coercion [Lasswell]. Conversely, supply-driven tools proactively seek to absorb or further utilize resources that have not yet been engaged in the governance process, or whose efficacy has not yet attained the anticipated level. Demand-pulled tools are characterized by their adherence to demand orientation, which is often mediated by the pursuit of specific objectives by residents, social workers, social organizations, enterprises in the jurisdiction, and other subjects. These tools are then passively filled with corresponding resources. In contrast, environment-influenced tools are employed through performance evaluation, strategic planning, and other means to influence the effectiveness of governance. These tools form the basis for the development of governance, working in tandem with demand-pulled tools. The potential repercussions of this phenomenon on the efficacy of governance mechanisms and the cultivation of an enabling environment for citizen participation in governance processes have been identified.

In contrast, society-based tools concentrate on prospective, gradual enhancements in resources. These tools are non-compulsory and discreet, underscoring the significance of guidance and indoctrination for participants in governance. Value-guided tools have a tendency to cultivate favorable concepts and encourage the development of effective community governance by establishing role models and disseminating information through multiple channels. Society-regulated tools establish a treaty system to restrain undesirable behaviors and individuals who may exert a detrimental influence on community governance. It is evident that value-guided tools have a tendency to establish positive concepts in the minds of residents through the establishment of governance role models and multi-channel publicity. Furthermore, these tools promote the benign development of community governance. Conversely, society-regulated tools set up a corresponding treaty system to regulate undesirable behaviors and individuals who may have a negative impact on urban community governance. In addition, honor-motivated tools induce residents to adopt or give up certain behaviors by means of positive rewards and awards. It is evident that these tools promote community governance by means of material or spiritual gifts. Honor-motivated tools have been shown to influence residents’ adoption or renunciation of specific behaviors through the utilization of positive rewards and commendations, with the ultimate aim of enhancing governance effectiveness through the distribution of material or spiritual gifts.

In addition, market-based tools unleash the dividends of community governance. Market-based tools, compared to other tools, introduce a competitive logic so that social governance, which emphasizes publicness, does not get stuck in a state where it is difficult to make progress. In accordance with prevailing market behavior, the classification of market-based tools is as follows: market-barred, market-accessed and market-expanded. The logic of punishment in society-based tools is continued by market-barred tools. The market-barred tools continue the logic of punishment in the society-based tools. Social organizations and enterprises exhibiting competitive behaviors that are deemed to fall within the purview of community governance, and which have been identified as contributing to mass incidents, are subject to sanctions through the utilization of market-barred tools. The utilization of market-accessed tools is accompanied by the establishment of access standards, thereby ensuring the quality of community governance and community services is safeguarded. The integration of market-expanded tools has been demonstrated to effect a transformation in the logic of market participation in community governance, thereby achieving harmonization between the market and public aspects of community governance.

5.2.3. Building Subject Sub-Community of “Everyone Performing Their Dutie” Based on Co-Governance

Co-governance is the means and ways to realize urban governance community. In the context of the community, the concept of collaborative governance between subjects can be understood as co-governance in the narrow sense. However, the broader sense of co-governance encompasses not only the collaboration of multiple subjects, but also the interaction of multiple relationships and the application of diverse means.

Firstly, the organizational structure of synergistic integration is realized through the synergy of multiple subjects. In the context of polycentric governance theory, new organizations are continually emerging within the domain of urban governance. Furthermore, a growing number of social organizations and enterprises characterized by their autonomy are entering the governance field. This development represents a deviation from the conventional unidirectional narrative structure that characterizes traditional governmental institutions. There should be a synergistic integration of regime organizations, social organizations and civil organizations so that the process of co-governance can be better promoted

The second is to take the interaction of multiple relationships as a way to realize a mutually beneficial and win-win relationship structure. Whether it is recognized or not, some developing countries represented by China (especially in Asia) are influenced by historical and cultural traditions and hierarchical systems, and their urban community governance is still characterized by the top-down management thinking of “street-community-residents”. Urban governance community needs to deal with several pairs of relationships. On one hand, there is street and community, which as a traditional governance relationship promotes the stability of the community. In the Chinese governance context, the appointment and dismissal of community leaders and the allocation of financial resources to the community are largely determined by the street. Therefore, we should try to introduce the feedback mechanism of “community evaluation of the street” to realize positive interaction. On the other hand, there is the community and community, through which different communities cooperate and link up, and jointly send out initiatives to other organizations, seek resources, and jointly organize activities to realize the spillover effect of resources. In addition, the relationship between community and residents is also important. The community as a living space is composed of individual residents, and it should understand and respond to the real needs of the residents. The feedback from social organizations or enterprises on the needs of the people out of self-interest often deviates from the reality, which increases the cost of community services for the residents.

Thirdly, the use of multiple means is a way to dissolve involution and realize value reconstruction. On one hand, controlling means are used, such as regulations issued by governmental organizations, administrative penalties and market access rules. On the other hand, negotiating means are used as an auxiliary means. Traditional controlling means should be applied within a strictly defined framework to avoid affecting the legitimate rights and interests of citizens. While negotiating means can enable the participating subjects to discuss and interact with each other on their own interests. At the same time, guiding means should be used as a “secret weapon”; controlling and negotiating means tend to respond to the existing problems, but neglect the prevention of possible problems in the future. Meanwhile, negotiating means can promote people to go beyond inward thinking and realize value reconstruction.

5.2.4. Building Idea Sub-Community of “Everyone Sharing Their Benefits” Based on Co-Sharing

First, the concept of efficacy will be used to promote the elimination of blind synergy. As a different framework for understanding urban governance, the evaluation criteria of the Urban Governance Community will give full consideration to result orientation. That is to say, it will take multiple effectiveness-oriented indicators such as the public’s sense of access, public satisfaction and public recognition as the basis and standard for comprehensive evaluation.

Secondly, the concept of harmony has been adopted as the purpose of promoting the empowerment of common values. That is to say, because of the need for survival and development, the participating subjects, such as governmental organizations, social organizations and civil society organizations, have examined and gradually overcome the friction that arises in the process of interacting with other subjects, and have broken the delay in action brought about by differences in their own interests, so that the subjects of governance can work together in a sincere manner.

Thirdly, the concept of service as a purpose promotes the return of identity. After all, urban governance community is a mode of governance, and the fundamental purpose of governance is still to make the residents of the object of the right to be guaranteed to obtain a better life experience. Only through the realization of such a way can residents deepen their identity and sense of belonging to the urban community.

The urban governance community model in the broad sense contains several dimensions: (1) identification and transformation of problems, (2) the need for relevant community mechanisms, (3) the process by which the model works, and (4) the prevention of possible future problems. The narrower urban governance community is defined as the process of the model in solving urban problems, i.e., party organization participation and the three sub-communities of Resource sub-community, Subject sub-community, and Idea sub-community.

The urban governance community model has different positive values compared to traditional governance models. In the existing scholarship on urban governance, several influential models have been widely discussed. First, the polycentric governance model emphasizes that multiple relatively autonomous decision centers achieve governance effectiveness through competition, cooperation, and policy learning [56]. However, this model primarily focuses on the distribution of authority and institutional arrangements, paying less attention to how governance communities are socially constructed and sustained through relationships and shared identities. In contrast, the proposed “urban governance communities” (UGC) model highlights how interpersonal ties, collective norms, and identity formation underpin the long-term sustainability of governance networks.

Second, the collaborative governance model underscores the joint decision-making of public authorities, private actors, and citizens in institutionalized deliberative platforms, where trust-building, shared vision, and procedural legitimacy are key factors. Yet, this model tends to emphasize process design and institutional legitimacy, often overlooking community self-organization and long-term mobilization. The UGC model addresses this gap by stressing the mechanisms through which governance communities are maintained over time.

Furthermore, the urban commons governance model focuses on the co-management of urban resources and spaces, highlighting the importance of rule-making and commoning practices in governance. Nonetheless, this approach remains largely resource-centered and pays limited attention to how governance communities emerge across different issues and groups. The UGC model goes beyond this limitation by centering on the social construction and sustainability of governance communities.

Taken together, the UGC model not only engages in dialogue with existing governance frameworks but also offers a critical extension, foregrounding its distinctive contribution to explaining the processes through which governance communities are both constructed and sustained.

6. Conclusions

This study utilizes the grounded theory research method to explore the formation process of urban governance communities and their operation mechanisms. It is based on the national typical cases of innovative social governance selected by China, a representative of developing countries. In the course of the study, traditional urban governance issues are identified and typologically classified. Concurrently, the role played by each community mechanism and its incorporation into a suitable theoretical model are investigated. The findings of the study indicate that “urban governance communities” possess a degree of explanatory power and reference value with regard to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal of constructing sustainable cities and communities at the urban governance level within the contemporary non-Western context.

Despite the novel theoretical and practical contributions of this study to the field of urban governance, there are certain limitations that must be acknowledged. Firstly, the subjects of the study are districts and units that have accumulated some experience in governance. The explanatory power and applicability of the “urban governance community” may be affected in areas with particularly harsh conditions. The second issue pertains to the integration of disparate data sources. While the integration of primary and secondary sources can expand the scope of available data, it concomitantly increases the likelihood of incorporating less reliable data. Thirdly, the replication of governance experiences in developing countries warrants consideration. While urban governance communities can provide different ideas for development, for developed countries with mature experiences, trying out new models may imply an increase in the cost of governance. For other developing countries, however, the model needs to be integrated with their specific national conditions in order to better promote urban governance. The Chinese sample that is the focus of this study is influenced by its strong state capacity, party leadership structure and top-down diffusion mechanisms. However, whether it can be replicated in an environment where civil society and democracy play a more central role remains open to debate. It is true that such a path is not an optimal solution for a number of developing countries. But UGC offers a differentiated way of thinking about their understanding of the problems facing their cities. We look forward to the replication of this solution, and even more so to its continued contribution to the success of the SDGs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.X., W.Z. and T.W.; Data curation, W.X., W.Z. and T.W.; Formal analysis, W.X., W.Z. and T.W.; Funding acquisition, W.X.; Investigation, W.X.; Methodology, W.X., Y.C. and S.M.; Project administration, W.X.; Resources, W.X.; Validation, W.X.; Writing—original draft, W.X.; Writing—review and editing, W.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by funds from the Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (KYCX25_0540) and Major Program of the National Social Science Fund (24&ZD192) by National Philosophy and Social Science Work Office of the People’s Republic of China.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Politecnico di Milano (22 October 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Meijer, A.; Bolívar, M.P.R. Governing the smart city: A review of the literature on smart urban governance. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2016, 82, 392–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; Rok, A. Co-producing urban sustainability transitions knowledge with community, policy and science. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018, 29, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castán Broto, V. Urban governance and the politics of climate change. World Dev. 2017, 93, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuirk, P.; Baker, T.; Dowling, R.; Maalsen, S.; Sisson, A. Enacting urban governance innovation: Beyond strategic pathways to incremental “muddling through”. Urban Geogr. 2024, 46, 1539–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, S.H. A crisis in governance: Urban solid waste management in Bangladesh. Habitat Int. 2010, 34, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z. Politics over photovoltaics: Unpacking the politically directed deployment of agrivoltaics in China. Sustain. Sci. 2025, 20, 1313–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulaert, F.; Martinelli, F.; González, S.; Swyngedouw, E. Introduction: Social innovation and governance in European cities—Urban development between path dependency and radical innovation. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2007, 14, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finewood, M.H.; Matsler, A.M.; Zivkovich, J. Green infrastructure and the hidden politics of urban stormwater governance in a postindustrial city. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2019, 109, 909–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, J.J.; Brown, R.R. Governance experimentation and factors of success in socio-technical transitions in the urban water sector. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2012, 79, 1340–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelnovo, W.; Misuraca, G.; Savoldelli, A. Smart cities governance: The need for a holistic approach to assessing urban participatory policy making. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2016, 34, 724–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Kang, C.I. A citizen participation model for co-creation of public value in a smart city. J. Urban Aff. 2022, 46, 905–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijke, J.; Farrelly, M.; Brown, R.; Zevenbergen, C. Configuring transformative governance to enhance resilient urban water systems. Environ. Sci. Policy 2013, 25, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, J. The Politics of Urban Governance; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- DiGaetano, A.; Strom, E. Comparative urban governance: An integrated approach. Urban Aff. Rev. 2003, 38, 356–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernt, M. Partnerships for demolition: The governance of urban renewal in East Germany’s shrinking cities. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2009, 33, 754–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.S. The governance of urban regeneration: A critique of the ‘governing without government’ thesis. Public Adm. 2002, 80, 301–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, J.J.; Huitema, D. Institutional innovation in urban governance: The case of climate change adaptation. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2019, 62, 374–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N. Bringing Transition Management to Cities: Building Skills for Transformative Urban Governance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosol, M. Public participation in post-Fordist urban green space governance: The case of community gardens in Berlin. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2010, 34, 548–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ánchez-Hernández, M.I. Strengthening resilience: Social responsibility and citizen participation in local governance. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vara-Sánchez, I.; Gallar-Hernández, D.; García-García, L.; Moran Alonso, N.; Moragues-Faus, A. The co-production of urban food policies: Exploring the emergence of new governance spaces in three Spanish cities. Food Policy 2021, 103, 102120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Gong, Y.; Li, Y. Citizen Satisfaction, Community Attachment, and their Engagement in Coproduction: A Survey Study in China. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2025, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez Benson, O.; Pimentel Walker, A.P. Grassroots refugee community organizations: In search of participatory urban governance. J. Urban Aff. 2021, 43, 890–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keivani, R.; Mattingly, M. The interface of globalization and peripheral land in the cities of the south: Implications for urban governance and local economic development. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2007, 31, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Luo, J.; Liu, S. Performance evaluation of economic relocation effect for environmental non-governmental organizations: Evidence from China. Economics 2024, 18, 20220080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastar, M. What drives the urban water regime? An analysis of water governance arrangements in Hyderabad, India. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajor, E.E.; Ongsakul, R. Mixed land use and equity in water governance in peri-urban Bangkok. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2007, 31, 782–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maya Jariego, I. Using stakeholder network analysis to enhance the impact of participation in water governance. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, R.; Bruns, A.; Bartels, L.E.; Kooy, M. Water Brokers: Exploring Urban Water Governance through the Practices of Tanker Water Supply in Accra. Water 2019, 11, 1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egusquiza, A.; Cortese, M.; Perfido, D. Mapping of innovative governance models to overcome barriers for nature-based urban regeneration. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 323, 012081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, C.; Scott, D.; Hordijk, M. Urban water governance for more inclusive development: A reflection on the ‘waterscapes’ of Durban, South Africa. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2015, 27, 488–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eakin, H.; Keele, S.; Lueck, V. Uncomfortable knowledge: Mechanisms of urban development in adaptation governance. World Dev. 2022, 159, 106056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.S.; Youn, Y.C. Development of urban forest policy-making toward governance in the Republic of Korea. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.; Koski, C. Multilevel governance and urban climate change mitigation. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2015, 33, 1501–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrichs, D.; Krellenberg, K.; Fragkias, M. Urban Responses to Climate Change: Theories and Governance Practice in Cities of the Global S outh. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2013, 37, 1865–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstad, H.; Sørensen, E.; Torfing, J.; Vedeld, T. Designing and leading collaborative urban climate governance: Comparative experiences of co-creation from Copenhagen and Oslo. Environ. Policy Gov. 2022, 32, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bortel, G. Network governance in action: The case of Groningen complex decision-making in urban regeneration. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2009, 24, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Sun, X.; Sun, L.; Choguill, C.L. Optimizing the governance model of urban villages based on integration of inclusiveness and urban service boundary (USB): A Chinese case study. Cities 2020, 96, 102427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadzadeh, A.; Fekete, A.; Khazai, B.; Moghadas, M.; Zebardast, E.; Basirat, M.; Kötter, T. Capacitating urban governance and planning systems to drive transformative resilience. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 96, 104637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garschagen, M. Risky change? Vietnam’s urban flood risk governance between climate dynamics and transformation. Pac. Aff. 2015, 88, 599–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, L.; Gabbe, C.J.; Schmidt, E. Urban heat governance: Examining the role of urban planning. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2023, 25, 642–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schramm, E.; Kerber, H.; Trapp, J.H.; Zimmermann, M.; Winker, M. Novel urban water systems in Germany: Governance structures to encourage transformation. Urban Water J. 2018, 15, 534–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehnert, F. Review of research into urban experimentation in the fields of sustainability transitions and environmental governance. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2023, 31, 76–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, A.; Hussein, H.; Thiel, A. Polycentric Governance and Agroecological Practices in the MENA Region: Insights from Lebanon, Morocco and Tunisia. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2024, 40, 816–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellner, E.; Petrovics, D.; Huitema, D. Polycentric Climate Governance: The State, Local Action, Democratic Preferences, and Power—Emerging Insights and a Research Agenda. Global Environ. Polit. 2024, 24, 24–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopáčková, H.; Komárková, O.; Horák, J. Enhancing the Diffusion of E-Participation Tools in Smart Cities. Cities 2022, 123, 103640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussien, A.; Maksoud, A.; Al-Dahhan, A.; Abdeen, A.; Baker, T. Machine Learning Model for Predicting Long-Term Energy Consumption in Buildings. Discov. Internet Things 2025, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksoud, A.; Al-Beer, H.B.; Mushtaha, E.; Yahia, M.W. Self-Learning Buildings: Integrating Artificial Intelligence to Create a Building That Can Adapt to Future Challenges. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1019, 012047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polko, A. Governing the Urban Commons: Lessons from Ostrom’s Work and Commoning Practice in Cities. Cities 2024, 155, 105476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransen, J.; Hati, B.; Simon, H.K.; van Stapele, N. Adaptive Governance by Community Based Organisations: Community Resilience Initiatives during COVID-19 in Mathare, Nairobi. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 1471–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Qirui, C.; Lv, Y. “One Community at a Time”: Promoting Community Resilience in the Face of Natural Hazards and Public Health Challenges. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Lin, X.; Shan, S. Big data-assisted urban governance: An intelligent real-time monitoring and early warning system for public opinion in government hotline. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2023, 144, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G. Basics of Grounded Theory Analysis: Emergence vs. Forcing; Sociology Press: Mill Valley, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G. Theoretical Sensitivity: Advances in the Methodology of Grounded Theory; Sociology Press: Mill Valley, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, K.; Nabatchi, T. Evaluating the Productivity of Collaborative Governance Regimes: A Performance Matrix. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2015, 38, 717–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).