Abstract

Education for sustainable development (ESD) has been UNESCO’s response to the climate crisis, promoting a reframing of what, where, and how students learn so they can act on environmental challenges. In Chile, while several initiatives have aimed to promote environmental education, their impact has been limited, lacking depth in terms of curricular content and teaching practices. When analysing the Chilean national curriculum, there remains a significant gap in how sustainability-related content is delivered to students. This study explores why this gap exists and examines teachers’ and students’ perceptions regarding the integration of ESD in the curriculum. To achieve this, interviews and a focus group with teachers were conducted, alongside questionnaires for both teachers and students. Findings indicate a lack of teacher preparation in ESD: many teachers report having taught related topics without feeling adequately equipped to do so. Although the current Chilean curriculum includes references to sustainability, and upcoming updates are expected to strengthen this focus, teachers require targeted professional development to effectively implement ESD in practice. Additionally, most students surveyed expressed interest in learning more about sustainability and the climate crisis and believe these topics should be more present in the curriculum. However, results suggest that curriculum adjustments and teacher training alone are insufficient. For ESD to be fully integrated, support must also be extended to school leadership teams, and structural school conditions must be addressed. Further research is needed to explore the views of other key educational actors regarding the integration of sustainability into Chilean education policy and practice.

1. Introduction

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports that human activities are responsible for temperature rises due to high greenhouse gas emissions, with the climate crisis intensifying extreme weather, disproportionately affecting the poorest and most vulnerable populations [1]. Education for sustainable development (ESD) is therefore essential for students to acquire the knowledge and competencies needed to address these challenges [2]. In response to the climate crisis, UNESCO has developed an ESD framework to “increase the contribution of education to building a more just and sustainable world” [3] (p. 3). This approach places respect for others, including present and future generations, diversity, and the environment at the centre of educational work [4], and redefines the role of students, recognising their responsibility in driving change and advocating for social and climate justice [5].

However, despite the growing emphasis on ESD, significant challenges remain, as sustainability is only marginally included in curricula in many countries [6,7]. For example, 47% of national curriculum frameworks in 100 countries make no reference to climate change [8]. Furthermore, a global survey of 58,000 teachers conducted by UNESCO found that while many are motivated to teach ESD topics, 25% do not feel prepared to do so [9]. In most countries, ESD remains optional and marginalised in teaching and learning processes [10].

A pedagogy based on sustainability must encourage critical thinking and climate crisis activism, as youth and future generations will face the real challenge of responding to the climate crisis [11]. Confident and capable teachers are needed to integrate sustainability approaches within education [12]. Teacher training is therefore essential for developing an understanding of environmental and climate change issues and for incorporating pedagogical tools into classrooms [13]. A survey in England found a strong positive correlation between teachers who had participated in professional development and those who frequently incorporated sustainability content in their teaching [14].

This article focuses on the case of Chile, analysing the measures taken regarding ESD and its integration into the educational curriculum. In Chile, the Ministry of Environment runs many environmental education initiatives that seek to generate habits and behaviours of care and conservation of the environment in citizens [15]. These initiatives include the National School Environmental Certification System (SNCAE) [16], the Environmental Education Portal, and the Adriana Hoffmann Academy, which were designed to provide tools for teachers and school principals [15,17]. Furthermore, ESD-related concepts are integrated into the subjects of “Science for Citizenship” and “Religion” in the secondary curriculum.

However, when reflecting on the presence of an ESD approach in the Chilean curriculum, some ideas and concepts have been found to be superficially integrated, without really changing what and how students learn [18,19]. There are also questions surrounding the adequacy of teacher training on sustainability issues [19,20]. Therefore, this study aims to gain an in-depth understanding of the Chilean curriculum and its link to an education for sustainable development approach, with the objective of understanding its influence on teaching practice and its applicability in the classroom and student experience.

The main question that this research seeks to answer is as follows: how do Chilean teachers and students view the place of education for sustainable development in the curriculum? The study aims to understand teachers’ and students’ perceptions of ESD and its link to the Chilean curriculum, reflect on their understanding of ESD, consider the challenges of integrating this approach, and identify teacher training needs. The objective is to acknowledge the obstacles teachers face and the value they place on ESD, as well as to understand students’ interests and their connection to sustainability and climate crisis issues. To address these questions, a survey, focus group, and semi-structured interviews were carried out with teachers and students in three schools in Santiago.

This research is conceptualised from a climate justice perspective [21,22], centred in local knowledge and the perspectives of teachers and students, and recognising that the most affected communities are often those least responsible for the crisis [23,24]. ESD is understood as a holistic framework addressing environmental, economic, and social issues [13,25], but needs to be set in the context of historic and ongoing injustices of a material and epistemic nature. Integrating a decolonisation perspective into education points to social justice as a fundamental value in addressing the climate crisis [25]. This research aims to bridge the gap between decolonial thought and sustainable development by emphasising local knowledge and the perspectives of teachers and students.

Education plays a crucial role in shaping future generations’ ability to confront environmental challenges and must provide students with the knowledge and skills to be prepared for present and future challenges [26]. Incorporating sustainability at the core of the curriculum is both a necessity and an ethical responsibility [4]. The urgency of the climate crisis compels us to rethink education from its foundations [27].

The next section will provide an overview of relevant research literature on ESD in Latin America and in Chile. Following that, there will be an outline of the research design of the study, the analysis of the findings, and a discussion of implications for policy and practice.

2. Literature Review

This literature review explores the conceptual foundations of education for sustainable development (ESD), its global and regional challenges, the integration of ESD in Latin American curricula, and the specific case of the Chilean educational system.

2.1. Education for Sustainable Development: Concepts and Global Challenges

Education for sustainable development (ESD) is widely recognised as a transformative educational approach that equips learners with the knowledge, skills, values, and agency to address complex global challenges, including climate change, biodiversity loss, and social inequality [26]. ESD is not limited to environmental education; it encompasses economic and social dimensions, aiming to foster critical thinking, problem-solving, and participatory action [28,29].

UNESCO asserts that the current educational paradigm is insufficient to address the scale of the planetary crisis, stating:

What we know, what we believe in and what we do needs to change. What we have learned so far does not prepare us for the challenge. This cannot go on. And the window of opportunity is closing fast. We must urgently learn to live differently.[26] (p. 6)

This call for transformation is echoed by Sterling [30], who argues that a “change of fundamental epistemology in our culture and hence also in our educational thinking and practice” (p. 1) is required.

Despite international consensus on the importance of ESD, its implementation remains inconsistent. Aikens et al. [6] found that sustainability education policies are often poorly understood and marginally included in national curricula. Bagoly-Simó [7], in a comparative study of Romania, Mexico, and Bavaria, observed that ESD is frequently treated as an “add-on” rather than a core curricular element, resulting in superficial integration. Jucker [31] further contends that education systems tend to reproduce unsustainability, highlighting the need for a paradigm shift in both content and pedagogy.

A significant barrier to effective ESD implementation is the lack of teacher training. Chinedu et al. [32] emphasises that teacher preparation is crucial for developing the competencies required to integrate ESD into classroom practice. UNESCO [3,33] also identifies insufficient teacher training as a persistent obstacle, noting that “educators in all educational settings can help learners understand the complex choices that sustainable development requires and motivate them to transform themselves and society” [3] (p. 30).

2.2. ESD in Latin American Curricula

Latin America has made notable progress in incorporating sustainability concepts into educational policy and curricula. At the university level, Leal et al. [34] report a range of sustainability initiatives, including waste and water management policies, biodiversity actions, and energy efficiency improvements. Fuchs et al. [35] argue that Latin American universities should further align their academic activities with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), suggesting that this can be achieved by monitoring community socio-environmental problems and mobilising students for social intervention. Furthermore, Acevedo-Duque et al. [36] suggest that higher education institutions should provide permanent training for their teaching staff, in addition to constantly updating and redesigning curricula so they can respond to the challenges related to sustainable development.

Yet, despite these advances, Álvarez-Vanegas et al. [37] highlight that while teachers in Colombia and Ecuador demonstrate a good understanding of sustainability, there is still a need to strengthen their ESD-related knowledge and competencies. UNESCO’s [38] analysis of ESD-related concepts in the curricula of Latin American countries noted that concepts such as environment, sustainability, and biodiversity are highly present, whereas concepts like climate change, contamination and economy are not [38]. As a result, UNESCO [39] suggests the need to improve knowledge regarding ESD in the region, because even if some concepts were present, they “are usually found only at a declarative level but are not incorporated into content and didactic programming” (p. 14).

Furthermore, as Pedraja-Rejas et al. [40] note, most research on ESD in Latin America has concentrated on higher education, leaving a gap in understanding its integration at the primary and secondary levels. The literature thus points to a need for deeper integration of ESD across all educational levels and for more research on its implementation in schools.

2.3. The Chilean Educational Curriculum and ESD

The Chilean educational curriculum provides a valuable case study for examining the integration of ESD at the national level. The curriculum, defined by the Ministry of Education, sets out minimum learning outcomes and offers flexibility in their achievement [41]. However, the extent to which ESD is embedded within this framework, and the roles of the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Environment, raise important questions about coherence and effectiveness.

Chile’s National Policy on ESD, established in 2009, aims to develop reflective, ethically responsible individuals capable of acting for the common good and the future [42]. This policy is led by the Ministry of Environment and includes several environmental education initiatives like “Forjadores Ambientales”, a programme that supports the creation of environmental clubs to foster civic responsibility; “Redes Ambientales”, a national network of environmental education centres; and the “Adriana Hoffmann Environmental Training Academy”, which offers training focused on raising awareness and understanding of environmental issues. A dedicated repository of environmental education resources, including activities and audio–visual material, is also available. Furthermore, the Chilean Ministry of Education [17] offers material for holding reflection days on the topic of climate action, an optional teacher training course on COP25, explanatory videos on sustainability issues, and a programme called “Interescolar ambiental”, carried out jointly with the Ministry of Environment and Kyklos, a Chilean NGO working on ESD issues.

One of the most popular initiatives from this National Policy is the “National System of Environmental Certification of Educational Establishments” (SNCAE) [16]. The SNCAE offers public recognition and access to resources for schools that achieve the environmental certification. However, Salinas-Cabrera [43] notes that the effectiveness of this programme is limited by the optional nature of certification and the heavy workload of teachers. There is also a risk that certification becomes a box-ticking exercise rather than a catalyst for genuine cultural transformation.

Additionally, the Ministry of Education has recently launched a website on Education for Sustainability and Climate Change, aiming to support the implementation of a comprehensive framework for sustainability education [17]. However, this platform is still under development, and the resources provided are optional rather than integrated into the core curriculum.

The Chilean primary school curriculum addresses ESD primarily through a technical–scientific and economic growth lens [44]. It emphasises understanding natural processes, technological developments, and historical–economic transformations, focusing on measurement, modelling, and factual knowledge. While this approach builds conceptual understanding, it gives less attention to transformative ESD, which involves fostering critical thinking, questioning social and economic structures, promoting community participation, and envisioning alternative futures. As a result, the social dimension of sustainability is less prominent, with a stronger focus on understanding the world as it is rather than empowering learners to transform it.

UNESCO’s [18] curriculum analysis of Chilean primary education found that while there is some alignment with ESD and the 2030 Agenda, and development of skills such as critical thinking, communication, and collaboration, sustainability is mainly addressed through the natural sciences. In contrast, sustainability is largely absent from the language and mathematics curricula. The natural sciences curriculum promotes environmentally responsible behaviour and healthy lifestyles but often frames sustainability in terms of personal health rather than a comprehensive understanding of the climate crisis.

In secondary education, the Ministry of Education has incorporated ESD-related concepts into subjects such as “Science for Citizenship” and “Religion”. However, the former was recently introduced, and the second one is optional, and there is no mandatory teacher training for their delivery [45]. Salinas et al. [46] analysed the Chilean science curriculum from primary to secondary education and noted that climate action is mainly promoted through the subject Science for Citizenship, taught during the last two years of schooling. While this represents an opportunity to address ESD in schools, the authors also identified an increasing prescriptive nature of the science curriculum in relation to grade levels. This trend positions teachers primarily as executors of the curriculum, minimising their involvement in design and reducing their sense of ownership, which may lead to diverse responses to its implementation. Such findings underscore the importance of teacher education and professional development to foster an understanding of the rationale behind the curriculum and the expectations placed on teachers as social actors [46]. Furthermore, Berríos, Orellana, and Bastías [21] found that even when sustainability concepts are present in the curriculum, they are often linked to pro-environmental attitudes rather than the development of critical thinking skills, which are essential for effective ESD [3]. Moreover, considering the science curriculum in secondary education, Guerrero and Torres-Olave [47] argue that although recent curricular reforms represent a paradigm shift towards a more critical and socio-political vision of scientific literacy, emphasising citizenship, democracy, and social justice, this potential is undermined by the limited recognition of teachers’ agency.

Berríos and González [19] argue that one of the main challenges for ESD in Chile is the integration of this pedagogical vision into initial teacher training. Without adequate preparation, teachers may adopt a transmissive rather than transformative approach, limiting the potential for meaningful change. The Ministry of Environment [15] similarly emphasises the need for teacher training to support the development of students who are aware of and committed to sustainability.

2.4. Barriers and Opportunities for ESD in Chile

The literature identifies several barriers to the effective integration of ESD in Chile. These include the superficial inclusion of sustainability content, the lack of cross-curricular integration, and insufficient teacher training [19,20]. The voluntary nature of many ESD initiatives and the absence of a coordinated approach between the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Environment further complicate implementation.

At the same time, there are opportunities for progress. The ongoing process of curriculum reform in Chile, including the development of a Comprehensive Framework for Education for Sustainability and Climate Change, offers a chance to embed ESD more deeply across all subjects and educational levels [48]. The strong interest expressed by both teachers and students in learning about sustainability, as reported in recent studies, suggests a receptive environment for change [9]. A climate justice perspective is increasingly recognised as essential for ESD, particularly in contexts like Chile, where the most vulnerable communities are disproportionately affected by environmental degradation [23,49].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

This study adopted a mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative and qualitative methodologies to explore teachers’ and students’ perspectives on the integration of ESD in the Chilean curriculum. The rationale for this design was to obtain both a broad overview of attitudes and a deeper understanding of individual experiences, as recommended by Robson and McCartan [50]. The research was underpinned by a critical paradigm, which means it aimed not only to understand the perceptions of both students and teachers regarding ESD, but also to question and challenge the underlying power structures and inequalities that influence these perceptions. This approach recognises the importance of environmental justice as a key driver for change, viewing ESD not just as a pedagogical goal but as a transformative process that can promote greater equity and social change within educational settings.

3.2. Setting and Participants

The research was conducted in three secondary schools in Santiago, Chile, each representing a different type of educational institution: a state school, a state-funded independent school, and a fully private school. Two of the schools are located within the same council, while the third is situated in a neighbouring municipality with similar socio-economic characteristics. This selection was intended to capture a range of perspectives across different school types and funding models.

The study targeted two main groups: teaching staff and students in their third and fourth years of secondary education (ages 16–18). These students were chosen because their curriculum includes the subject “Science for Citizenship”, which explicitly addresses ESD topics. For the qualitative component, 11 teachers participated (7 in individual interviews and 4 in a focus group), covering a wide range of taught subjects, including history and social sciences, chemistry, science for citizenship, religion, physics, mathematics, and subjects from the technical vocational specialisations such as nursery, administration, metal construction, and electricity. The ages of the teachers ranged from 30 to 60 years, with a balanced gender distribution (5 of them were women and 6 were men).

3.3. Data Collection

3.3.1. Quantitative Data

Two online questionnaires were developed ad hoc for the purposes of this study: one for teachers and one for students (Appendix A and Appendix B). The teacher questionnaire was distributed to 138 staff members across the three schools, with 21 responses received. The low response rate from teachers may be attributed to the fact that the dissemination of the questionnaire took place at the end of the school term, when many teachers were occupied with end-of-term responsibilities and other activities. While this presented the risk of a skew, the sample includes teachers from different subjects, genders, and levels of seniority, providing diversity similar to that of the general teacher population at the schools.

The student questionnaire was sent to 735 students, with 443 responses collected. Both questionnaires included primarily closed questions to facilitate quantitative analysis and encourage a higher response rate. The teacher questionnaire focused on perceptions of ESD, prior training, and interest in further professional development. The student questionnaire explored their understanding of sustainability, experiences with related content in the curriculum, and interest in learning more about climate and sustainability issues.

3.3.2. Qualitative Data

To complement the survey data, qualitative methods were employed. The semi-structured interview and focus group question guides (Appendix C) were specifically developed for this study, based on the research objectives and a review of relevant literature on ESD. The questions were informed by existing frameworks and qualitative research on similar topics to ensure conceptual robustness and relevance to the target population. The development process included internal validation through expert review and pilot testing with a small group of participants to ensure clarity and alignment with the study’s aims.

Seven semi-structured interviews were conducted with teachers from two schools, and a focus group was held with four teachers from the third school. Participants for the interviews and the focus group were selected based on availability and recommendations from school management teams, ensuring a range of subject specialisations. The interviews and focus group aimed to explore in greater depth teachers’ definitions of sustainability, their experiences with ESD in the classroom, perceived barriers, and training needs.

All interviews and the focus group were conducted in person by the first author, audio-recorded with consent, and transcribed verbatim in Spanish. The qualitative data collection was designed to allow flexibility, enabling participants to elaborate on issues beyond the scope of the questionnaires.

3.4. Data Analysis

3.4.1. Quantitative Analysis

Survey data were analysed descriptively, focusing on frequencies and percentages to summarise the main trends in teachers’ and students’ responses. This approach provided an overview of general attitudes and experiences regarding ESD in the participating schools.

3.4.2. Qualitative Analysis

Thematic analysis was used to examine the interview and focus group transcripts. Coding was conducted manually, with key themes identified based on the most frequently mentioned ideas and concerns. The analysis focused on six main topics: (1) definitions of sustainability; (2) ESD in the Chilean curriculum; (3) students’ perspectives and teachers’ views on student engagement; (4) teacher training in ESD; (5) top-down strategies and stakeholder engagement; and (6) the future of ESD in Chilean education. This process enabled the identification of both commonalities and divergences in participants’ experiences and perceptions.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the British Educational Research Association’s ethical guidelines [51]. Participation was voluntary, and all participants were informed of the study’s aims and procedures. Written informed consent was obtained from all teachers involved in interviews and the focus group. For the questionnaires, consent was implied by completion. Anonymity and confidentiality were assured, with all data stored securely and reported in aggregate form. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw at any time without penalty. Given the potentially sensitive nature of discussing climate change and sustainability, information about local support networks was provided to all participants.

3.6. Strengths and Limitations

A key strength of this study is its focus on both teachers’ and students’ perspectives, providing a holistic view of ESD integration in the Chilean curriculum. The inclusion of different school types enhances the transferability of findings. However, the study is limited by its small sample size and focus on a single urban area, which may restrict the generalisability of results. Additionally, the research did not include other stakeholders such as school leaders, parents, or policymakers, whose perspectives would be valuable for a more comprehensive understanding of ESD implementation.

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative Results

4.1.1. Understanding of Sustainability: Teachers and Students

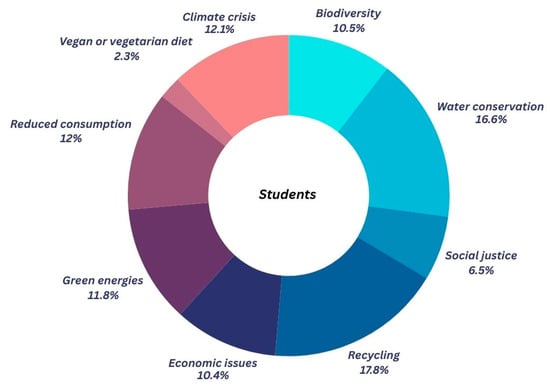

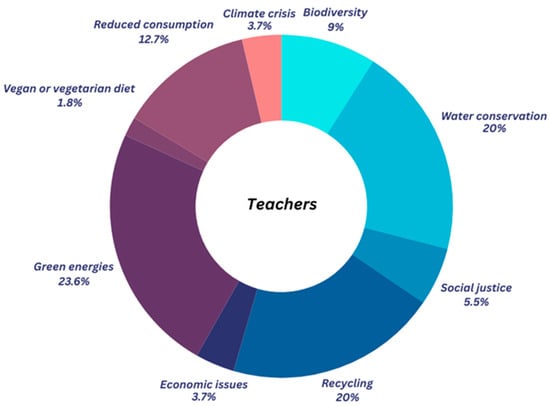

The survey results indicate that both students and teachers predominantly associate sustainability with environmental concepts. Among students (Figure 1), the most frequently selected concepts were recycling (249 responses), water conservation (233), and the climate crisis (170). Additional concepts such as economic issues and social justice were mentioned by a minority, suggesting some awareness of the broader social dimensions of sustainability.

Figure 1.

Concepts related to sustainability according to students.

On the other hand, teachers (Figure 2) most frequently selected green energies (15), water conservation (14), and recycling (13). Some also mentioned circular economy and sustainable food systems.

Figure 2.

Concepts related to sustainability according to teachers.

Additionally, teachers were asked in the survey if they had previously heard of the concept of ESD. Of the total responses, a slight majority (12) said they had heard of it before, while quite a few teachers claim not to have (6), and others do not know or do not remember having heard of it (3). This is particularly concerning, especially given that certain subjects, such as “Science for Citizenship”, explicitly incorporate it. This raises important questions about what is happening in schools that prevents teachers from recognising these topics.

4.1.2. ESD in the Chilean Curriculum

Regarding the integration of ESD in the curriculum, teachers were asked in the survey whether they believed that the curriculum should integrate these issues in its curricular bases. The vast majority stated yes, whereas only one person said no, and another was not sure.

To complement these ideas, the survey asked students if they had received or experienced any activity or class related to sustainability. Of the total responses, 144 students said yes, and 299 said no or did not remember. This result may be due to a lack of knowledge of the concept of sustainability, to the fact that they did not remember having received classes with this content, or because they have not learned about these issues in their classes.

As a complement to this, teachers were asked if they had taught sustainability topics in the classroom, and 16 responded that they had, while five responded that they had not or did not remember doing so.

4.1.3. Students’ Perspectives and Engagement

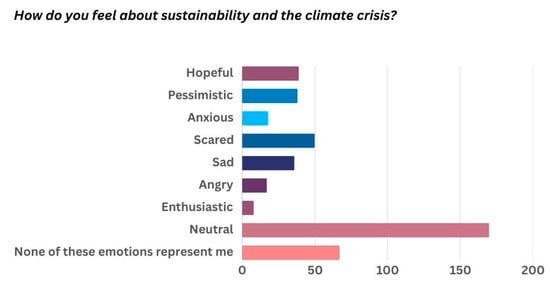

When asked about their feelings regarding sustainability and the climate crisis (Figure 3), from a total of 443 responses, most students reported feeling neutral, with smaller numbers expressing hope, anxiety or pessimism.

Figure 3.

Students’ feelings about sustainability and the climate crisis.

Despite this, 309 students considered it important to be taught about sustainability, and 222 expressed a desire to learn more about sustainability and the climate crisis. Students highlighted the need for more information and practical strategies to address these issues.

Following these questions, students had the opportunity to share what specific aspects of sustainability they would like to explore. Many emphasised the importance of acquiring more information, as they currently feel underinformed, and expressed a desire to develop a deeper understanding of these critical issues. Moreover, they frequently mentioned a strong interest in learning practical strategies and solutions to address the climate crisis, with the goal of taking meaningful action to improve the planet.

4.1.4. Teacher Training in ESD

Only 3 out of 21 teachers reported having received any training in sustainability or ESD, and all of them expressed interest in further training. This aspect is important to highlight, since the interest and motivation of teachers is present; however, for this interest to have a place, it is necessary to create the conditions for teachers to be able to attend training courses on sustainability. Teachers emphasised the need for practical, context-specific training that would enable them to integrate sustainability into their teaching practice.

4.2. Qualitative Results

4.2.1. Understanding of Sustainability: Teachers’ Views

One of the first questions asked in the interviews and focus group was about what teachers understand by sustainability and ESD. Teachers associated sustainability mainly with the responsible use of resources, environmental protection, social and environmental awareness, and the creation of self-sustaining systems. However, few initially connected sustainability with the role of education in fostering related knowledge and skills. This may be because, as mentioned by UNESCO [35], the inclusion of ESD concepts in the curricula is present in a declarative way, but not as part of the content and pedagogy of the school.

Despite this, when teachers were asked directly about the link between education and sustainability, some teachers did reflect on this point, such as a participant from the focus group who shared his own definition on ESD: “(For me) it is to provide tools to students so that they can develop skills to support social development through education” (Focus group, teacher 1). Moreover, an educator stated that ESD is “not only something that has to do with science, but also with morals and values” (Interviewee 7). In a complementary way, other teachers mentioned that through this type of education, students can be given an insight into what is really happening in our society, and thus they can help, contribute and reverse situations that are risky for everyone (Focus group, teachers 2 and 3).

Additionally, one teacher said that “with this type of education, as in no other, the student is the main actor in the classroom” (Focus group, teacher 4) referring to the implementation of the Science for Citizenship subject.

In relation to education, one of the teachers commented that:

The education system should play an important role in improving teaching to create real awareness in students that these issues are relevant, beyond what can be announced in the curriculum or in a law (…) this will lead us to first make a cultural and mental transformation, which begins in the classroom (Interviewee 5).

As the teacher mentions and Sterling [30] states, to visualise the link between education and sustainable development, a profound cultural change is required to rethink our educational thinking and practice.

Another aspect that appeared in the interviews, and was mentioned by three teachers, is the idea that sustainability is related to the cleanliness of personal and community spaces, appealing to the fact that students should be clean and tidy in the classroom, avoiding throwing paper on the floor and maintaining a respectful behaviour towards their environment. This may be because, as discussed in the definitions of the Chilean natural science curriculum, sustainability is incorporated alongside other concepts such as body and health care, and hygiene measures during puberty [18]. The prevalence of these discourses shows that there is still a lack of understanding of ESD issues among teachers and educational communities.

Teachers’ perceptions of ESD vary. Many align with its core principles, fostering critical thinking, action, and values for social and environmental change, yet as discussed above, sustainability is often linked to classroom cleanliness. This raises questions about why these views coexist, possibly reflecting a strong association between sustainability, waste reduction, and order in the school context.

After sharing their views on sustainability, teachers were presented with UNESCO’s [26] definition of ESD. They found it comprehensive, addressing not only content but also attitudes and values, and relevant to Chilean schools. Several emphasised the urgency of integrating it into the curriculum, noting that it reflects essential knowledge and calls for immediate action on environmental challenges (Interviewees 5, 6).

These comments suggest that some teachers do recognise the urgency for the education system to address sustainability issues [3], as students need to strengthen their knowledge and skills in this area. Although there is awareness of the environmental dimension of sustainability, the broader educational objectives of ESD are not yet fully acknowledged. The feedback on UNESCO’s definition highlights the importance of integrating sustainability concepts more deeply and comprehensively into the curriculum to effectively respond to global challenges.

4.2.2. Teachers’ Perspectives on ESD in the Chilean Curriculum

According to both educational programmes and interviews, sustainability is not explicitly included in most subjects’ curricula. However, the educators who teach the subjects of science for citizenship and religion noted that sustainability topics are partially referenced, due to recent curriculum updates in 2020.

In this context, the role of religion in the curriculum is noteworthy. The elective religion subject underwent modifications in 2020 to integrate sustainability as a central theme. Concepts like “care for the environment as God’s creation” are introduced progressively, culminating in the study of Pope Francis’s Encyclical Laudato Si’, which addresses environmental stewardship and climate change policies. This integration reflects a blend of faith and science, offering a unique perspective on sustainability. This subject incorporates an interdisciplinary approach, not only addressing social, economic, and environmental issues but also incorporating values and moral considerations, as outlined in the National ESD Policy [42].

One teacher emphasised the role of religion in fostering environmental care, highlighting initiatives such as ecological and environmental projects proposed by students (Interviewee 7). In this sense, the religion curriculum contributes significantly to promoting student agency as a key element of sustainability. This perspective resonates with Jickling and Wals’s [52] transformative vision of education, in which students actively participate in shaping a more sustainable society. Moreover, the teacher also pointed out that this approach is not limited to Catholic beliefs but is applicable to any religion, underscoring the shared responsibility of believers in the care of creation: “We, as believers, are jointly responsible for the care of creation; otherwise, everything will be destroyed. It is about raising awareness…” (Interviewee 7). Although this subject is based on an ESD approach, the subject is elective, and therefore not all students are exposed to these contents and methodologies that strengthen the understanding and care for the environment.

In technical vocational fields like metal construction and electricity, sustainability is not explicitly in the curriculum, but some teachers integrate it through personal initiative and curricular flexibility. For instance, a metal construction teacher (Interviewee 5) includes sustainability topics using transversal objectives, and an electricity teacher (Interviewee 3) introduces renewable energy due to personal interest. These examples show how teacher motivation and creativity can embed sustainability despite limited curricular content. However, UNESCO [9] notes that insufficient training often limits teachers’ ability to effectively teach ESD topics.

These examples show that in subjects where sustainability is not formally included, the personal interest and initiative of teachers become crucial for bringing these issues into the classroom.

4.2.3. Teachers’ Views on Student Engagement with ESD

Overall, all teachers acknowledged that while some students are interested in sustainability, others show little to no interest. Three teachers agreed that although many students express an interest in these topics, this does not translate into concrete actions. One teacher remarked: “I would say that students who are interested in issues related to recycling and sustainability see them as important, but not enough to take action” (Interviewee 6). Another teacher pointed out that there is still much work to be done, and that this is also related to issues of justice and inequality: “(students say) why should I save water if others are wasting it? Why should I make the change if others are going to do absolutely nothing?” (Interviewee 4). This highlights the need to reinforce the link between ESD content and practical action while also raising awareness of the social and climate justice aspects of this approach [23].

Another educator (Interviewee 1) pointed out that students’ connection to sustainability often takes the form of imposed behaviours aimed at maintaining school cleanliness, enforced by teachers or staff, rather than translating into meaningful interventions that strengthen sustainability within the school culture. This educator also noted that, although the school has solar panels, only electricity students are aware of their purpose and benefits, while the rest of the pupils remain uninformed. This lack of awareness may stem from insufficient teacher training, which limits the delivery of relevant sustainability-related knowledge, as highlighted by Greer et al. [12].

In the focus group, teachers expressed differing perspectives. Some argued that, particularly in the subject Science for Citizenship, students often lack the maturity to engage with the course seriously. They explained that students are used to working mainly for grades, while this subject emphasises group work and project development, activities that are not valued as highly as more traditional subjects with a greater impact on final grades. For this reason, teachers highlighted the need for a cultural shift that encourages students to focus on the learning process rather than solely on assessment outcomes. Conversely, another teacher reported that when they asked their students how they felt about the subject and whether they wished to continue with its methodology and content, 90% expressed their desire to do so, demonstrating strong motivation and interest.

Furthermore, another interviewee highlights the change that occurs in their students when accompanying them in their final years of schooling:

There is a significant change in them, and one of these changes is to generate this awareness in themselves, who suddenly say ‘so much paper, teacher’, or they themselves told me ‘Teacher, look at all this printed material! And then, what do you do with this paper?’ (Interviewee 2).

Students show strong interest in green energy and renewable projects, particularly when these are interdisciplinary. Teachers note their awareness of climate change, even in low-income contexts, and their motivation to act. This engagement reflects their desire for concrete ways to address the climate crisis. As Abeygunawardena et al. [23] highlight, teaching sustainability must include climate and social justice, since these generations, though not the main contributors, will face its greatest impacts. Providing them with the knowledge and tools to respond is an ethical responsibility of the education system [1].

4.2.4. Teacher’ Views on Professional Development in ESD

Interview data revealed that most teachers had not received formal training in sustainability education, relying instead on personal research or optional workshops to deepen their knowledge. Teachers emphasised the importance of making ESD training mandatory and accessible, ideally during working hours and free of charge. They also suggested that such training should involve the entire educational community, including students and school leaders.

None of the educators reported having received formal sustainability training. Two teachers had participated in workshops related to sustainability, motivated by personal interest rather than school-led initiatives; one of them (Interviewee 3) even organised online training with certification in renewable energy for their students. Additionally, three educators from the same school mentioned having received information about recycling through a school programme, but they did not consider this as formal ESD training.

It is important to highlight the case of four educators who teach the subject Science for Citizenship, one of the main subjects in the curriculum addressing sustainability-related issues, including climate change, sustainable consumption, and environmental protection [45]. Although it is the only subject that addresses these topics and has only recently been incorporated into the curriculum (in 2020), the teachers reported having received no formal training. Consequently, their expertise has largely been based on personal research and interests. At least three teachers noted that they initially approached the course with considerable apprehension and doubt, as it represented a significant departure from the traditional curriculum, with new methodologies that were challenging to implement without adequate support.

The same happened with the educator who teaches religion, who was also faced with changes in the curricular bases of her subject, saying that:

The ministry chooses them (the curricular bases), makes them and publishes them, and it is like ‘read them’, but it does not make a mandatory call, because this is also super optional for teachers (Interviewee 7).

Moreover, she points out that the appropriation of the curricular bases is often relegated to the teachers’ own motivation:

Then the teacher discovers the content he has to deliver when he arrives at the school and when he prepares his classes. And they learn the content for five years, but it’s not mandatory. So, I think in this case, teachers of any subject are not obliged to know their curricular bases either at ministerial level or at school level (Interviewee 7).

Even though teachers have not received workshops on ESD, they all mention the importance of receiving such training. Many of them point out that there are several trainings or procedures they have to do within the school that are unnecessary and that they should instead be investing that time in learning about ESD, as these are more relevant issues for the current context. Moreover, one teacher emphasised that sustainability training should be mandatory for educators, noting that teachers must first be agents of change to empower their students to do the same (Interviewee 7).

Furthermore, teachers were asked what characteristics training on ESD should have for them to incorporate it into their teaching practice. Most interviewees emphasised that such training should focus on concrete strategies, providing them with knowledge and tools to connect sustainability issues with the subjects they teach. They also highlighted the importance of using examples from everyday life and the local context to make learning more meaningful for students. In addition, another educator stated that they would like to have access to diploma courses to deepen ESD, ideally free of charge (given that the teaching salary is not high) and during working hours, since otherwise they believe that the participation of teachers would not be very high (Interviewee 7).

Finally, another teacher mentioned that this type of training should not only be focused on educators, but also on students and the entire educational community:

The teaching resource can never be focused on a couple of people; it must be focused on many educational actors. And who better than the students themselves, who will be the ones who in the future will have to fight for these problems that affect us as a society (…) a talk, a plenary, a discussion, perhaps something lighter, more informal, but that involves everyone, not only me in my role as a teacher, but also the students (Interviewee 5).

This reflects a transformative view of education, requiring a cultural shift [30] to embed ESD in Chile’s education system. It also highlights the need to move beyond isolated courses, creating diverse learning spaces for teachers. One educator stressed the importance of formalising this training within the curriculum, suggesting that including it as a core objective would enable assessment and give it greater significance (Interviewee 5).

This underlines the need for a curriculum that supports ESD training, ensuring that these practices become part of everyday teaching. Structural changes in the education system are therefore essential to embed ESD meaningfully and sustainably.

4.2.5. Structural and Institutional Factors

Teachers identified several structural barriers to the effective integration of ESD, including the lack of mandatory curriculum content, insufficient training, and limited support from school leadership. They emphasised the need for top-down strategies, including policy changes and leadership training, to create the conditions necessary for ESD to be embedded in school culture.

According to one teacher (Interviewee 1), ESD training should be mandatory and should be implemented from the top down, involving those who make decisions about the educational system, and may even require curricular adaptation. As they point out, teacher training is not enough if it remains a workshop or an isolated educational experience. For teacher training to be truly effective, it requires the commitment of all the actors in the education system to facilitate the real incorporation of these contents and pedagogical practices in teachers’ work. Another educator stated the importance of involving all stakeholders—civil society, education, academia, and politics—in creating spaces for dialogue on ESD. They noted that change requires opportunities for collaboration, not blame, to build shared understanding and coordinated action (Interviewee 5). The teacher’s observation of a lack of dialogue among the various stakeholders in the education system suggests that ESD may not be receiving the attention it deserves within Chilean education. This absence of discussion could result in ESD being undervalued. Therefore, it is crucial to establish not only training opportunities but also forums for dialogue to engage all relevant parties with ESD issues effectively.

In addition, another teacher mentioned that sustainability is just being incorporated into the discourse and that urgent changes are required:

That (sustainability) is a recent topic, I believe that it is being talked about, and the field is opening to be able to carry it out. And yes, changes are already being made, but now those changes must be more visible. And to begin to get this information down to the grassroots where we should be, so that we all become aware and part of this, of taking care of the house (the planet) (Interviewee 4).

Again, the lack of dialogue and communication on sustainability issues in the education system shows the need to strengthen access to these issues, so that they are given greater relevance in teaching and learning processes.

Furthermore, the role of school principals in promoting and facilitating ESD is fundamental, as mentioned by some educators:

I think it is something that should start from the school leaders, not from the students, not from the teachers, but from the school leaders and request it at the level of the school community, projects (…) but I consider that it is useless if from above they do not say that we have to reflect on this topic and on what you received in your training (Interviewee 1).

Another teacher (Interviewee 7) emphasised that school principals must also be informed and trained, since they play a key role in turning schools into sustainable institutions. Without their leadership in integrating a sustainability-based approach into teaching and learning, it becomes difficult to implement the necessary changes for adopting an ESD framework. As Jucker [33] points out, redesigning teaching and learning processes is essential for ESD and requires the involvement of both policymakers and school leaders. In this sense, engaging all relevant school stakeholders is crucial to effectively integrate sustainability into classrooms and ensure that institutions can adopt an ESD approach. Otherwise, as one interviewee put it, teachers risk feeling like Don Quixote fighting alone for sustainability:

Many times, one feels like a Quixote, right? You feel like a Quixote, because you try to instil that in a 15-year-old kid, but he goes out into the street and finds another reality, another world (Interviewee 3).

The analogy of Don Quixote stands out as it demonstrates the emotion that often emerges when promoting behaviours and values of caring for the planet, when it is not shared by an educational community, or there is no curriculum to support these ideas. Quixote is a character who is labelled ‘mad’ for wanting to change the world and follow his ideals. In the educational context, teachers seeking to integrate sustainability issues in the classroom may believe that they are struggling alone to educate their students on ESD and feeling misunderstood in this struggle. If educational institutions and principals do not provide the support for this to occur, then the implementation of an ESD approach becomes very difficult.

4.2.6. The Future of ESD in Chile

Teachers agreed that ESD should be integrated from the earliest stages of education and across all subjects, supported by curriculum reform and comprehensive training for teachers and school leaders. Most interviewees saw its future in the education of kindergarten and primary students. As one teacher noted, introducing ESD early allows it to be implemented gradually, adapting to students’ growing autonomy and capacity for action (Interviewee 6).

Moreover, another teacher said that “it does not mean that if you do it (a training or workshop) to a 15-year-old teenager he or she will not change, but the impact may not be as powerful as if I do it in primary education” (Interviewee 4).

In addition, a different educator (Interviewee 7) mentioned that schools should promote a cultural shift towards sustainability, together with strengthening the development of agency in students. They believe that schools should be open to do more activities related to the environment, so that these skills and knowledge do not reduce the action of caring for the environment only to the classroom. Moreover, they think that at the educational level, we are still far behind in terms of informing and educating about how students can be agents of change for sustainable development in personal, family and school aspects.

Teachers highlighted that the future of ESD depends on curriculum reform, requiring legislative support to prioritise this type of education. Interviewee 7 noted that the inclusion of environmental care in the new curricular bases (to be published in 2026) could facilitate ESD integration, if teachers acquire the necessary knowledge and apply it in their subjects. The educator emphasised the need for a cultural shift among teaching staff, making climate change a central focus in teaching and learning, and ensuring that raising awareness is genuinely valued.

5. Discussion

5.1. Environmental Focus and Gaps in ESD Understanding

It is noteworthy, from the questionnaire results, that nearly half of the teachers reported being unfamiliar with ESD. The results also reveal a strong environmental focus in both teachers’ and students’ understanding of sustainability, with limited attention to its social and economic dimensions. The findings, consistent with previous research [29,39], show that ESD is often interpreted primarily through an environmental lens, thus risking underrepresenting the interconnected social and economic aspects of sustainability. Regardless of terminology, educational approaches must address both environmental and social dimensions to realise the full transformative potential of ESD.

The limited awareness of ESD among teachers, despite its inclusion in subjects like “Science for Citizenship”, points to a gap in both initial and ongoing teacher training. The lack of teacher training in ESD [3,19,33] becomes even more relevant, as teachers mention that they have been confronted with teaching these topics. It would therefore be pertinent to explore how these issues have been presented in the classroom, as the lack of teacher training may be contributing to the fact that, even though many teachers claim to have taught these subjects, many students (68%) do not recall learning about sustainability. As Aikens et al. [6] and Bagoly-Simó [7] have argued, superficial integration of sustainability in the curriculum is common, and without adequate teacher preparation, ESD remains marginal.

5.2. Curriculum Integration and Teacher Agency

The findings indicate that the integration of ESD in the Chilean curriculum is uneven and often dependent on individual teacher initiative. While some teachers incorporate sustainability topics based on personal interest, the lack of explicit curriculum content and mandatory training limits broader implementation. This is consistent with UNESCO [9], which found that teacher motivation is high, but structural barriers persist.

The main subjects addressing sustainability in Chile’s updated 2020 curriculum [53,54] are “Religion”, which is optional, and “Science for Citizenship”, a subject newly introduced that same year. However, the optional nature of one of these subjects, combined with a lack of teacher training in curricular adjustments, suggests that not all students are exposed to ESD content, which is consistent with the results presented in the survey, where 68% of students stated that they do not recall having received classes with ESD content.

This fragmentation is further compounded by the fact that, even within these subjects, the approach to ESD is often predominantly attitudinal or behavioural rather than theoretical. As Berríos, et al. [19] highlight, the curriculum tends to emphasise the development of pro-environmental attitudes and behaviours, such as recycling, cleanliness, and resource conservation, over the cultivation of critical thinking skills and a deeper understanding of the complex social, economic, and political dimensions of sustainability. While fostering positive attitudes is undoubtedly important, an exclusive focus on shaping attitudes and behaviours risks narrowing the scope of ESD. Rather than empowering students to question, analyse, and address the root causes of environmental and social challenges, this approach may limit their engagement to individual actions, without fostering critical thinking or systemic understanding.

This issue extends into the realm of social and climate justice, as the responsibility for learning about these critical issues should not be left to the individual teacher’s discretion and availability. Instead, it is the responsibility of public policies and curricular frameworks to ensure the integration of an ESD approach within the education system [5]. Such policies should aim to provide all children and young people with access to quality ESD.

5.3. Student Engagement and Climate Anxiety

It is important to highlight the predominance of neutral feelings among students regarding sustainability and the climate crisis, especially considering the growing awareness of climate anxiety as a significant source of emotional distress for young people [55]. This neutrality could be derived from a lack of knowledge about the climate crisis, or it may serve as a coping mechanism for eco-anxiety [56]. If the latter is true, providing students with information about the climate crisis might inadvertently lead to climate numbing, rather than encouraging proactive engagement. Therefore, the need to train students in sustainable development is key, but it needs to be accompanied by action [5,26]. While students express a desire for more information and practical solutions, the current curriculum and teaching practices may not adequately address these needs.

Teachers’ observations that student interest does not always translate into action highlight the importance of linking ESD content to real-world challenges and opportunities for agency. Teachers observed that while students recognise the importance of sustainability and social issues, many struggle to take action. As Kaur [5] and UNESCO [26] suggest, ESD should empower students to take meaningful action, not just acquire knowledge.

5.4. The Need for Comprehensive Teacher Training

Both the survey and the interviews, as well as the focus group, reveal a strong interest in ESD training among teachers. However, this interest contrasts with the limited formal opportunities currently available, underscoring the need for systemic change. Effective integration of ESD requires more than curriculum reform: it demands accessible, practical, and context-specific professional development [12,13]. This responsibility extends beyond individual teachers to public policies and curricular frameworks, ensuring that all students have access to quality ESD while addressing broader issues of social and climate justice [33]. Teachers’ calls for mandatory training, its inclusion within working hours, and the involvement of the entire school community reflect an understanding of ESD as a collective responsibility, one aligned with the transformative vision of education advocated by Sterling [30] and by Jickling and Wals [52].

5.5. Structural Change and Stakeholder Engagement

The findings underscore the importance of top-down strategies and leadership in embedding ESD in school culture. Teachers noted the need for policy changes, leadership training, and stakeholder dialogue to overcome the sense of isolation—or “Don Quixote” syndrome—experienced by educators promoting sustainability, who may feel misunderstood or struggle alone. Without support from school leadership, implementing ESD becomes difficult.

As one educator argued, teacher training has limited impact if it remains at the individual level. They suggested that, to be effective, training should be embedded within the curriculum and promoted from the top, creating opportunities for collective reflection and motivating wider teacher engagement. As noted, training alone is insufficient; effective ESD integration requires the commitment of all educational actors. School principals and management teams play a critical role, as systemic change depends on the active involvement of the entire education system [31,33].

5.6. Towards a Holistic and Transformative ESD

The consensus among teachers and students that ESD should be integrated from early years education and across all subjects’ points to the need for a holistic approach. This requires not only curriculum reform and teacher training but also a cultural shift within schools and the broader education system.

The findings suggest that Chile is at a crossroads, with opportunities for meaningful change through ongoing curriculum reform and increased attention to ESD. By addressing the barriers identified in this study, Chile can move towards a more comprehensive and transformative approach to sustainability education.

6. Conclusions

Among the main findings of this study, the need for training identified by Chilean teachers in relation to ESD stands out. However, as covered in the interviews and questionnaires, most teachers highlight the need to have a curriculum that supports the integration of these issues in the classroom, and therefore facilitates the work of educators. To this end, it is important to highlight that Chile is currently updating its curricular bases (a five-year process), which includes public consultation with schools and stakeholders. The preliminary proposal suggests strengthening sustainability in areas such as science and technology [53,54]. While this effort is valued, teachers stress that a cross-cutting approach is still needed, integrating sustainability across all subjects and school culture.

It is recommended that curricular reforms, such as the recent updates in religion and citizenship education, be accompanied by comprehensive training for teachers and school management teams. As argued in this research, these changes represent a cultural shift that demands not only new knowledge and practices but also innovative teaching methodologies. Teachers emphasised that this transformation involves adopting a new paradigm in which they act as facilitators of learning while students take on a more active, leading role.

In Chile, the Guiding Standards for Graduates of Teacher Education Programmes [57] outline the key competencies that newly qualified teachers are expected to develop. These include ethical and professional commitment, strong disciplinary and curricular knowledge, and the ability to design inclusive and meaningful learning experiences. The standards emphasise the use of active methodologies, formative assessment, and contextually relevant teaching practices. While ESD is not explicitly addressed, the framework promotes critical, inclusive, and ethically grounded teaching, creating opportunities to integrate sustainability themes across the curriculum. However, the lack of understanding and incorporation of sustainability education in the classroom is hindering teachers’ ability to effectively convey these contents.

As Fullan and Stiegelbauer [58] note, educational innovation entails a period of adjustment that can be uncomfortable, as it requires rethinking established practices. In Chile, teachers acknowledge the challenges and uncertainties of implementing the new subject Science for Citizenship, yet they remain committed and eager to acquire the tools needed to teach it effectively. The Ministry of Education should build on this willingness by providing resources and training that foster meaningful transformations in teaching and learning based on ESD principles.

Beyond curricular reform, strengthening school leadership is essential. Teachers stressed that principals and management teams must also be trained, since their decisions shape the conditions for schools to advance toward sustainability. In addition, reinforcing dialogue among stakeholders—teachers, students, policymakers, civil society, and academia—is vital for creating shared strategies. As one teacher explained, “We are islands… if we generate opportunities to come together and build dialogue, that is the way to generate change” (Interviewee 5).

Returning to the question that initiated this research, the data collected provides answers to the perspectives of teachers and students regarding the integration of an ESD approach in the Chilean curriculum. It can be highlighted that teachers see and value the role of ESD in the Chilean curriculum, while recognising the minimum requirements for this curricular integration to be effective. In turn, students recognise their lack of knowledge on sustainability issues, while at the same time value the incorporation of these topics in the classroom. For ESD to have a place in the Chilean education system, teachers must have access to knowledge, skills, and resources that enable them to put this into practice, ultimately impacting the educational trajectory of students by providing them with the tools they need to face global social and environmental challenges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, A.A.; methodology, A.A.; validation, T.M.; formal analysis, A.A.; investigation, A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.; writing—review and editing, A.A. and T.M.; supervision, T.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of University College of London.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are not publicly available, though the data may be made available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Tristan McCowan for the supervision role in conducting this research and achieving its results.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ESD | Education for Sustainable Development |

| SNCAE | Sistema Nacional de Certificación Ambiental Escolar (National School Environmental Certification System) |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

Appendix A

- Questionnaire for Teachers

- Dear teacher,This questionnaire is being implemented in the context of the project “Teachers and students’ perspectives on integrating education for sustainable development contents in the Chilean curriculum” as part of one of the thesis of UCL’s MA “International Education and Development” programme. Particularly, through this project it is expected to reflect on teachers and students’ experiences and perspectives on incorporating sustainability issues in the education system.Your collaboration by answering this survey will be of utmost importance to understand the relevance of incorporating sustainability topics in the school curriculum. All information collected will be treated confidentially and anonymously. If you have further questions, you can contact the person in charge of this investigation: Alexandra Allel, alexandra.henriquez.23@ucl.ac.uk.Thanks for participating in this research.* If you no longer wish to respond to this survey at any time, you may stop responding.

- ☐ I consent to the use of the information obtained from this survey.

- Questions

- Select school

- -

- Names of school to be confirmed

- Which gender category do you mainly identify with?

- -

- Female

- -

- Male

- -

- Non-binary

- -

- Transgender

- -

- Prefer not to say

- For how long have you been teaching?

- -

- Select years (1–60 years of experience)

- What do you teach?

- -

- Visual arts

- -

- Natural sciences

- -

- Physical education and health

- -

- English

- -

- Language and communication

- -

- History, geography and social sciences

- -

- Math

- -

- Music

- -

- Orientation

- -

- Religion

- -

- Technology

- -

- Technical vocational specialty

- -

- Philosophy

- -

- Citizenship education

- -

- Science for citizenship

- Which of the following concepts do you think are related to Sustainability? (choose up to 3)

- -

- Biodiversity

- -

- Water conservation

- -

- Social justice

- -

- Recycling

- -

- Economic issues

- -

- Reduce consumption

- -

- Green energies

- -

- Veggie or vegan diet

- Have you heard about education for sustainable development or education for sustainability before?

- -

- Yes

- -

- No

- -

- Not sure/Don’t remember

- Have you received any training in education for sustainable development or sustainability?

- -

- Yes

- -

- No

- -

- Not sure/Don’t remember

- Would you be interested in receiving any training in sustainability contents?

- -

- Yes

- -

- No

- -

- Not sure

- Have you taught any contents or activities related to sustainability in your subject?

- -

- Yes

- -

- No

- -

- Not sure/Don’t remember

- Should the Chilean curriculum incorporate more sustainability related topics?

- -

- Yes

- -

- No

- -

- Not sure

- What do you think is missing in Chilean education to integrate issues such as the climate crisis and sustainability?

- -

- Open question

- Do you have any comments or suggestions?

- -

- Open question

Appendix B

- Questionnaire for students

- Dear student,This questionnaire is being implemented in the context of the project “Teachers and students’ perspectives on integrating education for sustainable development contents in the Chilean curriculum” as part of one of the thesis of UCL’s MA “International Education and Development” programme. Particularly, through this project it is expected to reflect on teachers and students’ experiences and perspectives on incorporating sustainability issues in the education system.Your collaboration by answering this survey will be of utmost importance to understand the challenges and limitations of integrating this type of content into the Chilean curriculum. All information collected will be treated confidentially and anonymously. If you have further questions, you can contact the person in charge of this investigation: Alexandra Allel, alexandra.henriquez.23@ucl.ac.uk.Thanks for participating in this research.* If you no longer wish to respond to this survey at any time, you may stop responding.

- ☐ I consent to the use of the information obtained from this survey.

- Questions

- Select school

- -

- Names of school to be confirmed

- Which gender category do you mainly identify with?

- -

- Female

- -

- Male

- -

- Non-binary

- -

- Transgender

- -

- Prefer not to say

- How old are you?

- -

- 16

- -

- 17

- -

- 18

- -

- 19

- Which of the following concepts do you think are related to Sustainability? (choose up to 3)

- -

- Biodiversity

- -

- Water conservation

- -

- Social justice

- -

- Recycling

- -

- Economic issues

- -

- Reduce consumption

- -

- Green energies

- -

- Veggie or vegan diet

- How do you feel about sustainability and the climate crisis?

- -

- Hopeful

- -

- Pessimistic

- -

- Anxious

- -

- Scared

- -

- Sad

- -

- Angry

- -

- Enthusiastic

- -

- Neutral

- -

- None of these emotions represent me

- Have you experienced any activities or contents related to sustainability in your classes?

- -

- Yes

- -

- No

- -

- Not sure

- Do you think is relevant to integrate sustainability topics in your classes?

- -

- Yes

- -

- No

- -

- Not sure

- Would you like to know more about sustainability and the climate crisis?

- -

- Yes

- -

- No

- -

- Not sure

- If your previous answer was “yes”, what would you like to learn about sustainability and the climate crisis?

- -

- Open question

- Do you have any additional comments or suggestions?

- -

- Open question

Appendix C

- Interview and focus group design.

- The following is the design of the questions proposed for the interviews and the focus group carried out in the context of this research.It is important to note that both the interviews and focus groups followed a semi-structured format, which allowed for new questions to emerge organically during the conversations with participants.

- Interview and focus group questions

- How do you see yourself in relation to your colleagues in terms of your interests in education for sustainable development?

- When talking about education for sustainable development, what are the first things that come up to your mind?

- Considering the following definition of education for sustainable development created by UNESCO:

“Education for sustainable development (ESD) gives learners of all ages the knowledge, skills, values and agency to address interconnected global challenges including climate change, loss of biodiversity, unsustainable use of resources, and inequality. It empowers learners of all ages to make informed decisions and take individual and collective action to change society and care for the planet. ESD is a lifelong learning process and an integral part of quality education. It enhances the cognitive, socio-emotional and behavioural dimensions of learning and encompasses learning content and outcomes, pedagogy and the learning environment itself”

- What do you think about integrating this into the education system?

- 4.

- Do you think that education for sustainability is integrated in the subject you teach? In which extent and how?

- 5.

- If receiving special training for incorporating sustainability topics in your classes, what kind of characteristics should this training have?

- 6.

- How and where do you see the future of the Chilean education system regarding sustainability issues?

References

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Romero, J., Lee, H., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- McCowan, T. Universities and Climate Action; UCL Press: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development: A Roadmap. UNESCO, Paris. 2020. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374802 (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- UNESCO. Framework for the UN DESD International Implementation Scheme. UNESCO, Paris. 2006. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000148650 (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- Kaur, K. Embed sustainability in the curriculum: Transform the world. Lang. Learn. High. Educ. 2022, 12, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikens, K.; McKenzie, M.; Vaughter, P. Environmental and sustainability education policy research: A systematic review of methodological and thematic trends. Environ. Educ. Res. 2016, 22, 333–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagoly-Simó, P. Tracing Sustainability: An International Comparison of ESD Implementation into Lower Secondary Education. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 7, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Getting Every School Climate-Ready: How Countries Are Integrating Climate Change Issues in Education. UNESCO, Paris. 2021. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379591 (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- UNESCO. Teachers Have Their Say: Motivation, Skills and Opportunities to Teach Education for Sustainable Development and Global Citizenship. UNESCO, Paris. 2021. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379914 (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- Bourn, D.; Hunt, F.; Bamber, P. A Review of Education for Sustainable Development and Global Citizenship Education in teacher Education. UNESCO. 2017. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000259566 (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- Dunlop, L.; Atkinson, L.; Stubbs, J.E.; Diepen, M.T. The role of schools and teachers in nurturing and responding to climate crisis activism. Child. Geogr. 2020, 19, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, K.; Walshe, N.; Kitson, A.; Dillon, J. Responding to the environmental crisis through education: The imperative for teacher support across all disciplines. UCL Open Environ. 2023, 6, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.J.; Monroe, M.C.; Oxarart, A.; Ritchie, T. Building teachers’ self-efficacy in teaching about climate change through educative curriculum and professional development. Appl. Environ. Educ. Commun. 2019, 20, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]