Abstract

Against the backdrop of ecological civilization construction and regional coordinated development strategies, functional zone (MFOZ) planning guides national spatial development through differentiated policies. However, a prominent conflict exists between the ecological protection responsibilities and regional development rights in restricted and prohibited development zones, leading to a vicious cycle of “ecological protection → restricted development → poverty exacerbation”. This paper focuses on the synergistic mechanisms between ecological compensation and targeted poverty alleviation. Based on the capability approach and sustainable development goals (SDGs), it analyzes the dialectical relationship between the two in terms of goal coupling, institutional design, and practical pathways. The study finds that ecological compensation can break the “ecological poverty trap” through the internalization of externalities and the enhancement of livelihood capabilities. Nevertheless, challenges remain, including low compensation standards, unbalanced benefit distribution, and insufficient legalization. Through case studies of the compensation reform in the water source area of Southern Shaanxi, China, and the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) of the European Union, this paper proposes the construction of a long-term mechanism integrating differentiated compensation standards, market-based fund integration, legal guarantees, and capability enhancement. The research emphasizes the need for institutional innovation to balance ecological protection and livelihood improvement, promoting a transition from “blood transfusion” compensation to “hematopoietic” development, thereby offering a Chinese solution for global sustainable development.

1. Introduction

The ecological civilization construction, a major strategic initiative proposed by the Chinese government in the 21st century, aims to promote harmonious coexistence between humanity and nature, achieving sustainable development in economic, social, and environmental dimensions. At the same time, to address the issue of regional development imbalance, regional coordinated development strategies, another significant policy direction of the Chinese government, have been consistently pursued. These strategies aim to optimize the policy system, promote integrated interactions among regions, gradually enhance development balance, and form a new pattern of coordinated development. In this process, China innovatively integrated the two, proposing Major Function-Oriented Zone (MFOZ) planning to coordinate ecological protection and regional development. An MFOZ is a spatial unit that identifies specific regions as certain types of major functional orientation based on their resource and environmental carrying capacity, existing development density, and development potential. MFOZ planning divides the national territory into four types of functional zones: optimized development zones, key development zones, restricted development zones, and prohibited development zones. The classification aims to guide regional functional positioning through differentiated policies, thereby achieving synergistic development of economic, social, and ecological benefits [1].

As urbanized areas, optimized and key development zones primarily serve to provide industrial goods and service products. In contrast, restricted and prohibited development zones, functioning as major agricultural production areas and key ecological function zones, are primarily tasked with supplying agricultural and ecological products. Their core role is to ensure national food security and the stability of the ecological system. These zones are predominantly located in ecologically fragile and economically underdeveloped areas. This geographical distribution leads to an increasingly prominent structural conflict between ecological protection responsibilities and regional development rights. Poverty is not only a significant cause of environmental degradation [2], but ecological restriction policies further exacerbate the survival challenges faced by local residents, creating a vicious cycle of “ecological protection → restricted development → poverty exacerbation” [3].

As targeted poverty alleviation becomes the core strategy for national poverty reduction efforts, effectively linking ecological compensation mechanisms with poverty alleviation policies emerges as a critical issue requiring urgent resolution. Research indicates that traditional regional development-oriented poverty alleviation models encounter bottlenecks in ecologically sensitive areas; excessive development leads to ecological degradation, while singular economic compensation struggles to offset the development opportunities lost by residents due to ecological protection measures [4]. The ecological compensation mechanism within MFOZs, characterized by “government-led, market participation, and multi-stakeholder collaboration” in fund allocation and policy design, offers a potential pathway to overcome this dilemma [5]. Nonetheless, existing mechanisms still suffer from issues such as low compensation standards, unbalanced benefit distribution, and insufficient sustainability, necessitating the exploration of coupling models between ecological compensation and targeted poverty alleviation at the institutional level [6].

Within the strategic context of coordinating sustainable rural development and common prosperity, constructing an ecological compensation mechanism oriented towards multidimensional poverty governance holds significant theoretical and practical value. Theoretically, developing multidimensional poverty identification standards based on the capability approach [7] and localizing the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) into a rural revitalization evaluation system [8] not only expands the operationalization pathways for Sen’s concept of “multidimensional poverty” but also enhances the theoretical framework of sustainable development. Guiding the optimal allocation of ecological resources through MFOZ planning [9] and exploring synergistic mechanisms for carbon sinks trading and cultivated land protection [10] offer new explanatory dimensions for breaking the “ecological poverty trap”. Practically, establishing a linkage mechanism between ecological compensation and poverty reduction [11] can promote coordinated regional development. For instance, the dual incentive mechanism of “carbon sink compensation–income growth” formed in Guangdong Province’s cultivated land protection [10] provides a replicable model for ecological poverty alleviation nationwide. Drawing lessons from the government–market collaborative compensation system constructed under the US Land Conservation Reserve Program [12] helps achieve policy synergy between “dual carbon” goals and rural revitalization. Currently, there is an urgent need to integrate rural digitalization into the capability-building framework [13] to address the capability deprivation issues faced by digitally disadvantaged groups in dimensions such as technology access and social participation, offering new insights for comprehensively enhancing the resilience of sustainable rural development.

Based on this context, this study focuses on the dialectical relationship between ecological compensation and poverty alleviation development within China’s Major Function-Oriented Zones (MFOZs) during the post-2020 consolidation period of poverty alleviation achievements (2020–2024), aiming to investigate their synergistic mechanisms with the overarching goal of breaking the vicious cycle of “ecological protection → restricted development → poverty exacerbation.” It seeks to address the following core questions: How can institutional innovation achieve the organic integration of internalizing ecological protection externalities and fostering the endogenous development of impoverished populations? How can sustainable poverty alleviation be promoted in impoverished areas while ensuring the functionality of ecosystem services?

To address the aforementioned issues, the core theoretical contribution of this study lies in constructing and applying an innovative three-dimensional integrated analytical framework, thereby deepening the understanding of the synergy between ecological compensation and poverty alleviation mechanisms. This framework systematically integrates three interrelated and progressively advancing key dimensions: (1) Externality Internalization: Moving beyond the traditional view of compensation as mere fiscal transfers, this dimension combines Pigouvian government intervention with Coasean market-based transaction logic. It explores how to translate the ambiguous value of ecosystem services into tangible economic incentives through a mix of government legislation and market instruments (e.g., water rights, carbon trading). (2) Institutional Synergy: Building on economic mechanisms, this dimension focuses on the alignment of ecological compensation and targeted poverty alleviation policies in terms of objectives, tools, and implementation. It examines how institutional design can ensure that compensation funds not only offset opportunity costs but also precisely serve poverty reduction goals, achieving a synergistic policy effect where 1 + 1 > 2. (3) Capability Reconstruction: As the ultimate focus of the framework, this study operationalizes Amartya Sen’s capability approach, shifting the policy’s end goal from short-term income boosts to the long-term expansion of poor populations’ functional activity spaces (e.g., access to education, healthcare, and market participation). This marks a fundamental transition from “blood transfusion” poverty relief to “blood generation” development. Unlike previous studies that often analyze these dimensions in isolation, this study innovatively integrates all three, revealing a coherent causal pathway: “economic incentives → institutional safeguards → capability enhancement.” This integrated framework provides a more holistic and actionable theoretical explanation for breaking the “ecological poverty trap.”

The article is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the theoretical logic and analytical framework. Section 3 details the dialectical relationship between ecological compensation and poverty alleviation in functional zones and presents innovative pathways, including long-term mechanism design for ecological compensation and poverty alleviation synergy. Section 4 provides a discussion. Section 5 presents the conclusion.

2. Theoretical Logic and Analytical Framework

2.1. Core Concept Definition

Ecological compensation in MFOZs is considered within the theoretical scope of a novel multi-objective compensation mechanism. From an environmental economics perspective, Meng Zhaoyi et al. (2008) define it as “a means to incentivize conservation behavior,” [1] with its core lying in regulating the externalities of socioeconomic activities in different functional zones through legal, administrative, and economic measures. The field of resource economics emphasizes its essence as “an institutional arrangement for the value appreciation of natural capital,” achieving the marketization of ecological values in restricted and prohibited development zones through opportunity cost assessment and policy design [9]. The strategic nature of this mechanism is reflected in the hierarchical division of compensation providers and standards; for instance, the ecological service values of national-level and provincial-level MFOZs exhibit gradient differences [14]. It is noteworthy that the current compensation system incorporates non-economic means such as intellectual compensation and employment training, providing institutional support for capability enhancement and long-term poverty alleviation for compensation recipients [15].

The theoretical core of targeted poverty alleviation stems from Amartya Sen’s “capability approach”. Liu Wanqi (2023), by constructing a dynamic multidimensional poverty measurement model, found that poverty identification solely based on the income dimension exhibits significant bias [7]. The lack of capabilities more fundamentally reflects the deprivation of rights among impoverished groups in areas such as education, healthcare, and social participation. Compared to traditional poverty alleviation models, targeted poverty alleviation needs to transcend the framework of short-term economic assistance and shift towards expanding the functional activity space of the poor population. For example, empirical research in three counties of Guizhou Province demonstrated that ecological compensation, through employment generation and public service improvement, could increase household poverty exit probability by 14–22% [11]. This finding corroborates the transmission logic of “capability–opportunity–outcome,” where the enhancement of individual capabilities significantly reduces the risk of returning to poverty [16].

2.2. Synergistic Logic of Compensation and Poverty Alleviation

The synergy between ecological compensation and poverty alleviation is rooted in their inherent geographical coupling and the structural contradictions within policy design. Cao Shisong et al. (2016) point out that impoverished areas are often compelled to bear protection responsibilities due to ecological fragility [2]. Geng Xiangyan and Ge Yanxiang (2017), through surveys in 14 contiguous poverty-stricken areas, found that 75% of China’s poor counties are located within key ecological function zones, exhibiting a significant positive correlation between ecological fragility and economic poverty (correlation coefficient of 0.68) [17]. This spatial overlap stems from structural contradictions in policy design: impoverished regions, by undertaking ecological functions such as water source conservation and biodiversity protection, proactively curtail their development rights, forming a vicious cycle of “ecological protection → accumulated opportunity costs → entrenched poverty” [2]. Simultaneously, the synergy of policy objectives requires that compensation standards must embed a poverty alleviation orientation. The reform trajectory of the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) shows that combining ecological subsidies with farmer income support systems led to a 12 percentage point decrease in poverty incidence in target areas [18]. This experience suggests that China’s horizontal compensation mechanisms need to establish a transmission chain of “ecological value → economic compensation → capability investment,” rather than mere fiscal transfers [19].

Institutional transformation manifests as an adaptive adjustment from “blood transfusion”-type compensation to “hematopoietic”-type poverty alleviation. Game theory analysis of water source protection areas indicates that single-fund compensation models tend to induce “welfare dependency” among recipients; 34.7% of farming households reduced agricultural production inputs after receiving compensation [20]. In response, Li Liang and Gao Lihong (2017) proposed constructing a “green livelihood substitution” mechanism, achieving endogenous development under environmental constraints through the cultivation of ecological industries [6]. A typical example includes the organic agriculture projects in the Southern Shaanxi water source area, which increased the average annual income of participating farmers by CNY 4200 while reducing fertilizer use by 23% [21]. This illustrates that the effective integration of compensation policies and poverty alleviation strategies hinges on activating the capability approach of impoverished groups and the synergistic value-added effects of regional ecological capital.

2.3. Analytical Framework

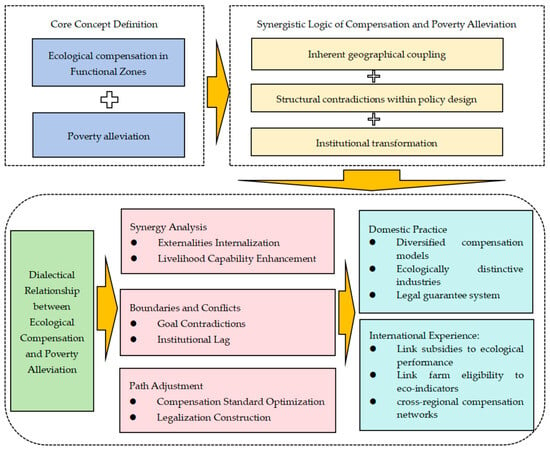

This study develops a comprehensive analytical framework to examine the dialectical relationship between ecological compensation and poverty alleviation within China’s MFOZs, structured around three interconnected dimensions (Figure 1). The theoretical originality of this study lies in its innovative application of the capability approach, shifting the analytical focus from traditional income effects to the multidimensional livelihood security and capabilities of impoverished populations, thereby profoundly revealing how ecological compensation policies substantively empower rather than merely “transfuse”. Its analytical framework transcends the limitations of previous research by integrating conceptual definitions, conducting a dialectical assessment of synergies and conflicts, and proactively exploring innovative policy pathways, constructing a systematic three-dimensional structure.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework construction.

The analytical framework commences by defining core concepts, positioning ecological compensation in functional zones as a policy instrument designed to address environmental externalities through both fiscal interventions and market-based approaches. Concurrently, poverty alleviation is conceptualized through Sen’s capability approach, with a focus on enhancing multidimensional aspects of livelihood security. Building upon this foundation, the framework elucidates the synergistic relationship between these concepts by examining their inherent geographical interconnectedness, particularly the spatial correlation between ecologically vulnerable regions and impoverished areas, alongside the institutional dynamics that emerge from tensions between conservation requirements and developmental aspirations. This synergy manifests through two primary mechanisms: the internalization of environmental externalities via economic instruments and the strengthening of livelihood capacities through targeted interventions such as vocational training and the cultivation of sustainable industries. Empirical validation for these mechanisms is drawn from domestic implementations, including forestry compensation programs in Jinzhai County, as well as international models exemplified by the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy.

The framework subsequently identifies critical challenges impeding effective policy integration, notably disparities between compensation adequacy and poverty alleviation objectives, as well as institutional deficiencies in legal frameworks governing compensation schemes. In response, the framework proposes a series of strategic adjustments: the development of differentiated compensation standards reflecting ecosystem service valuations across zonal categories, the establishment of robust legal frameworks to govern compensation distribution with explicit poverty alleviation allocations, and the incorporation of market-oriented mechanisms such as carbon credit systems to complement traditional fiscal approaches. These policy innovations are substantiated through both domestic best practices, including diversified compensation models implemented in Southern Shaanxi, and international exemplars such as performance-based payment systems in the EU, collectively facilitating a paradigm shift from compensatory support to sustainable capacity building. This tripartite analytical structure—encompassing conceptual foundations, synergy and conflict assessment, and policy innovation pathways—offers a comprehensive approach to harmonizing ecological preservation with socioeconomic advancement within functional zones, thereby contributing to theoretical discourse on poverty–environment linkages while informing practical strategies for sustainable development aligned with global sustainability goals.

Our study advances the operationalization of Sen’s capability approach in ecological poverty governance by proposing a novel tripartite framework that integrates externality internalization (Pigouvian/Coasean mechanisms), institutional synergy (compensation–poverty alleviation coupling), and capability reconstruction (functional activity space expansion). Specifically, we transcend existing works by (1) demonstrating how ecological compensation transforms from fiscal transfers into multidimensional capability investments (e.g., Jinzhai’s compensation funds directly enabling education/health access); (2) introducing spatial differentiation in compensation standards tied to MFOZ functional tiers (core/buffer/peripheral zones), addressing the “inverse incentive” gap in past studies; and (3) empirically validating the “ecological protection → capability enhancement → poverty exit” pathway through comparative case analysis (e.g., Southern Shaanxi’s CNY 4200 income increase via organic farming versus traditional subsidies).

2.3.1. Methods

This study employs a mixed-methods approach combining theoretical analysis, case study research, and policy evaluation to investigate the synergistic mechanisms between ecological compensation and poverty alleviation in China’s MFOZs. The methods consist of the following components: (1) a literature analysis method, in which a systematic literature review synthesizes international scholarship and policy documents to establish a theoretical framework, operationalizing core concepts of targeted poverty reduction and ecological service valuation; (2) a case analysis method, in which a comparative case analysis of domestic and international best practices identifies institutional synergies and systemic constraints in compensation mechanisms, validating theoretical propositions through empirical verification; (3) multidisciplinary integration of environmental economics, resource management, and legal studies, which elucidates the tripartite transmission mechanism (capacity-building → opportunity creation → outcome optimization) governing eco-compensation–poverty nexus, with Figure 1 diagrammatically representing the conceptual architecture.

2.3.2. Case Selection

In the case studies presented in this paper, the Southern Shaanxi region is selected as the core water source area of the South-to-North Water Diversion Middle Route Project, alongside two regions in the European Union.

The South-to-North Water Diversion Middle Route Project is a major strategic infrastructure initiative in China for cross-basin and cross-regional water resource allocation. The Southern Shaanxi region, serving as the core water source area of this project, encompasses three prefecture-level cities—Hanzhong, Ankang, and Shangluo (collectively referred to as “Southern Shaanxi Three Cities”)—covering 28 counties and over 90 townships. In 2024, the region had a permanent population of 7.6528 million and a regional GDP of CNY 383.086 billion, with an urbanization rate of 51.53%. The three cities in Southern Shaanxi boast superior ecological advantages, abundant mineral resources, and rich biodiversity, making them a key ecological functional zone of the Qinba Mountains and an important water conservation area for the South-to-North Water Diversion Middle Route Project. However, the economic scale of these three cities is relatively small, with limited industrial clusters and underdeveloped infrastructure. Innovation-driven support remains insufficient, and 23 counties are classified as restricted development zones (focusing on key ecological function areas). Most of these counties lie within the water conservation area of the South-to-North Water Diversion Middle Route Project, placing significant pressure on ecological protection. Additionally, some impoverished areas in the water source region achieved “poverty alleviation and removal of poverty” status by 2020, yet they continue to face weak economic foundations, difficulties in fiscal revenue growth, and constrained development space. The region also bears heavy pollution control responsibilities and struggles with the challenge of effectively linking the consolidation of poverty alleviation achievements with rural revitalization. Consequently, the conflict between water source protection and socioeconomic development has further intensified.

The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) of the European Union, implemented since 1962, has been one of the bloc’s most significant policies. Initially, its objectives were to enhance agricultural labor productivity, stabilize agricultural markets, and ensure “fair” income for farmers. Over time, however, the CAP has evolved from a purely market-oriented policy to a more comprehensive approach that prioritizes ecological protection, social equity, and sustainable development. Its core goals now include strengthening agricultural competitiveness, achieving sustainable management of natural resources, and promoting balanced regional development. This transformation makes the CAP an ideal case study for exploring the synergistic mechanisms between ecological protection and rural poverty alleviation, as its policy design and implementation processes have carefully considered multiple objectives—economic, social, and environmental.

2.3.3. Data Source

The data used in this case study is sourced from the 2025 statistical yearbooks on economic and social development, public financial data, and “14th Five-Year” environmental protection plans for the three cities in South Shaanxi. Specific data on forestry compensation in Jinzhai County is sourced from the “13th Five-Year” Forestry Development Plan of Jinzhai County, including key indicators such as compensation standards (150 CNY/hectare) and funding proportions (accounting for 40–45% of poverty alleviation funds). Data on the protection of the South-to-North Water Transfer source water areas is integrated from the “Hanzhong Danjiang River Basin Water Quality Protection Regulations” of Shaanxi Province. The European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) case directly references official reports from the European Commission, such as “Direct payments to agricultural producers—graphs and figures” and “Financial report of the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund.” These sources provide comprehensive and reliable data for the analysis of the synergistic effects of ecological compensation and poverty alleviation in Jinzhai County.

3. Results

3.1. Dialectical Relationship Between Ecological Compensation and Poverty Alleviation in Functional Zones

3.1.1. Synergy Analysis

The synergistic effect between ecological compensation and poverty alleviation development is manifested in its deconstruction of the “poverty induced by ecological conservation” problem and the systematic improvement of livelihood capabilities. Within the capability approach framework [16], compensation policies enhance individuals’ functional activity space for accessing resources and participating in development, thereby reshaping the economic opportunities and social empowerment of impoverished populations in ecologically fragile areas. Taking the practice in Jinzhai County as an example, this county, a crucial part of the Dabie Mountains Ecological Function Zone, has preliminarily established a linkage mechanism between ecological compensation and poverty alleviation development through measures such as national key ecological function zone transfer payments, forestry-specific compensation, and direct subsidies for reservoir migrants. From 2012 to 2014, ecological compensation funds consistently accounted for 40–45% of the total poverty alleviation funds, providing direct support for infrastructure construction, industrial development, and livelihood improvement for residents [3]. Research indicates that such compensation not only alleviates the conflict between ecological protection and regional development but also indirectly enhances employment opportunities for the poor population by promoting urbanization and industrialization processes. The essence of this mechanism lies in internalizing externalities, transforming the positive externalities of ecological services into economic benefits, thus breaking the vicious cycle of “conservation-induced poverty”.

The promoting effect of the ecological compensation–poverty alleviation synergy mechanism on ecological protection is reflected in its positive influence on farmers’ behavioral orientation. The Grain for Green project in Wudu District, Gansu Province, not only increased the economic income of absolutely poor farming households but also stimulated the initiative of the impoverished population to participate in ecological protection through the establishment of ecological stewardship positions [12]. Such cases demonstrate that when poverty alleviation measures are combined with ecological protection needs, the enhancement of livelihood capabilities can strengthen the dependence of impoverished groups on the ecosystem, subsequently forming a positive feedback mechanism of “protection → benefit → re-protection”.

3.1.2. Boundaries and Conflicts

Despite the synergistic potential between ecological compensation and poverty alleviation, they still face challenges in practice regarding conflicting goal priorities and insufficient institutional supply. Firstly, the rigid constraints of ecological protection often clash with short-term poverty reduction needs. Taking compensation for public welfare forests as an example, the standard in Jinzhai County was only CNY 150 per hectare, far below the economic value derived from timber harvesting [3]. This imbalance in compensation standards leads to a “reverse incentive”—forest owners fall into persistent poverty due to sacrificing economic benefits for ecological protection, even potentially leading to covert resistance through illegal logging. Research finds that when compensation amounts are lower than opportunity costs, ecological protection goals may be overridden by economic demands, and impoverished groups tend to adopt unsustainable livelihood strategies [11].

Secondly, the lag in the legal system constrains the long-term effectiveness of ecological-compensation-based poverty alleviation. Some scholars point out that the current ecological compensation system largely relies on policy promotion, lacking a legalized definition of compensation providers, standard calculation methods, and supervision procedures, resulting in arbitrariness in the allocation and use of compensation funds [6]. For example, the legal absence of payment obligations for downstream beneficiaries in trans-basin ecological compensation allows Jinzhai County to supply 2 billion cubic meters of water annually to Hefei City without compensation, failing to reflect the water resources’ value reasonably [2]. This institutional gap not only weakens the poverty alleviation effect but also exacerbates inter-regional inequality in development rights.

3.1.3. Path Adjustment

Alleviating the conflict between ecological protection and poverty alleviation goals requires starting with dynamic adjustments to compensation standards and the improvement of the legal framework. Firstly, compensation standards should be comprehensively determined based on ecological service value, protection costs, and regional development levels. For instance, compensation for reservoir water resources in Jinzhai County could reference pricing models like 0.1 CNY/ton for industrial use and 0.2 CNY/ton for domestic use, combined with a differentiated design based on the payment capacity of beneficiary areas [2]. Secondly, promoting ecological compensation legislation is necessary to clarify the responsibilities of the central government, local governments, enterprises, and the public. It is suggested that specific poverty alleviation clauses be included in the “Ecological Compensation Regulations,” stipulating mechanisms for evaluating the poverty reduction effectiveness of compensation funds and ensuring they are tilted towards registered impoverished households [6]. Furthermore, a legally binding mechanism for horizontal compensation needs to be established, incorporating the coordination of interests between upstream and downstream areas, as well as resource input and output regions, into legal procedures to avoid the “rich get richer, poor get poorer” pattern resulting from the transfer of ecological protection responsibilities [22].

3.2. Domestic and International Case Studies

To provide a clearer quantitative reference beyond qualitative institutional analysis, we have compiled and compared key indicators between the core domestic cases (e.g., Jinzhai County in China and Southern Shaanxi) and international benchmarks (e.g., the EU Common Agricultural Policy), as shown in Table 1. These data are not intended for rigorous causal inference but rather for highlighting significant disparities across dimensions such as compensation standards, funding structures, poverty alleviation outcomes, and ecological performance.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of key indicators in eco-compensation and poverty alleviation synergy mechanisms: domestic cases vs. international benchmarks.

The table allows readers to visually identify several critical issues. First, the severe “value–price” disparity in domestic cases like Jinzhai County—where compensation standards fall far short of the immense ecological value provided (e.g., water supply to Hefei City)—directly corroborates our earlier argument about inadequate compensation. Second, the high proportion of compensation funds in the total poverty alleviation budget (40–45%) underscores the fiscal importance of ecological compensation in certain impoverished regions while also hinting at potential “welfare dependency” risks. Furthermore, the income growth achieved by farmers in Southern Shaanxi through eco-industries, alongside the EU’s practice of strictly linking subsidies to ecological performance, collectively points to a transition path from “blood transfusion” (direct funding) to “blood generation” (sustainable development)—moving beyond mere financial transfers to integrate compensation with industrial growth and ecological accountability. This table lays a solid empirical foundation for the subsequent discussion, particularly the analysis of institutional paradoxes and policy innovations.

3.2.1. Exploration of Ecological Compensation Reform in the South-to-North Water Diversion Source Area in Southern Shaanxi

The Southern Shaanxi region, as the core water source area for the middle route of the South-to-North Water Diversion Project, exemplifies the dialectical relationship between ecological protection and poverty alleviation through its dual mission. Research by Fang Lan et al. shows that, constrained by harsh natural conditions [21] and MFOZ development restrictions, about 90% of the area in the three cities of Southern Shaanxi is mountainous, prone to geological disasters, and has weak infrastructure, resulting in high regional poverty incidence. In MFOZ planning, Southern Shaanxi is designated as a restricted development water conservation area. Traditional economic development models are strictly limited, forcing residents to rely on extensive resource exploitation, which exacerbates the vicious cycle of ecological degradation and poverty.

To resolve this conflict, Southern Shaanxi promoted transformational development in impoverished areas through ecological compensation mechanisms. Specific measures include the following: The first is the establishment of diversified compensation models by supplementing local development opportunity costs through central fiscal transfer payments and horizontal watershed compensation. Studies show that during the Xin’an River Basin pilot period, upstream Huangshan City achieved an average annual economic growth of 15.29% through compensation funds [22]. The second is the development of ecologically distinctive industries to promote green agriculture and ecological tourism for poverty alleviation. For example, Ankang City leveraged its selenium-rich resources to build a selenium-rich tea brand, increasing the income of over 50,000 farming households [21]. The third is the innovation of the legal guarantee system. Through the “Regulations on Water Quality Protection of the Hanjiang and Danjiang River Basins in Shaanxi Province,” tiered compensation was implemented: core water source areas receive full compensation based on ecological service value (Level I), buffer zones receive 80% compensation (Level II), and peripheral agricultural areas receive 60% compensation (Level III) [6], ensuring compensation funds are directed towards ecological migrants and impoverished groups. This model validates that ecological compensation can reshape the development path of functional zones, transforming ecological value into sustainable poverty alleviation momentum.

3.2.2. Goal Synergy Mechanism of the EU Common Agricultural Policy

The European Union provides valuable experience in coordinating ecological protection and rural poverty alleviation. Zhang Peng points out that the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) promotes the synergy of agricultural ecological transformation and rural poverty reduction through environmental payments and market incentives [18]. Its core mechanisms include the following: The first is the establishment of “green direct payments,” requiring 40% of agricultural subsidies to be linked to ecological performance, obliging farmers to fulfill environmental duties such as ecological coverage on arable land and biodiversity protection. This mechanism indirectly addresses the disconnection between compensation standards and ecological service value by dynamically adjusting subsidy proportions. The second is the implementation of “cross-compliance” rules, linking agricultural production eligibility to ecological indicators like land set aside and fertilizer reduction, and the specification of compensation reduction rates for non-compliance in the EU Agricultural Law [19], offering a legislative reference for China’s ecological compensation legalization. The third is the development of cross-regional compensation networks, such as the “eco-label” certification mechanism in the Alpine regions, which allows mountain ecological products to command a 20–30% premium, channeling funds back to farmers in ecologically fragile areas [23]. Data show that under the CAP framework from 2014 to 2020, the EU’s rural poverty rate decreased by 3.2 percentage points, and agricultural carbon emission intensity dropped by 12% [24].

A comparative analysis reveals significant implications for China from the EU experience: First, the findings point to the need for rethinking single fiscal compensation models. Effective mechanism design would involve legally defining the basis for calculating compensation standards (e.g., ecological service value, opportunity costs) and creating a co-existing framework that balances market incentives against policy constraints. Second, ecological assets in functional zones should be marketized through ecological certification and carbon trading to enhance the autonomous development capacity of impoverished groups. Third, the compensation performance evaluation system should be improved by incorporating ecological indicators into the assessment of local government poverty alleviation effectiveness [25]. This will drive the transformation from “blood transfusion” compensation to “hematopoietic” development, resolving the conflict between ecological protection and livelihood improvement. The EU’s “results-based payment” model, using satellite remote sensing to quantitatively assess protection outcomes, provides a technical pathway reference for China to establish dynamic compensation mechanisms [24].

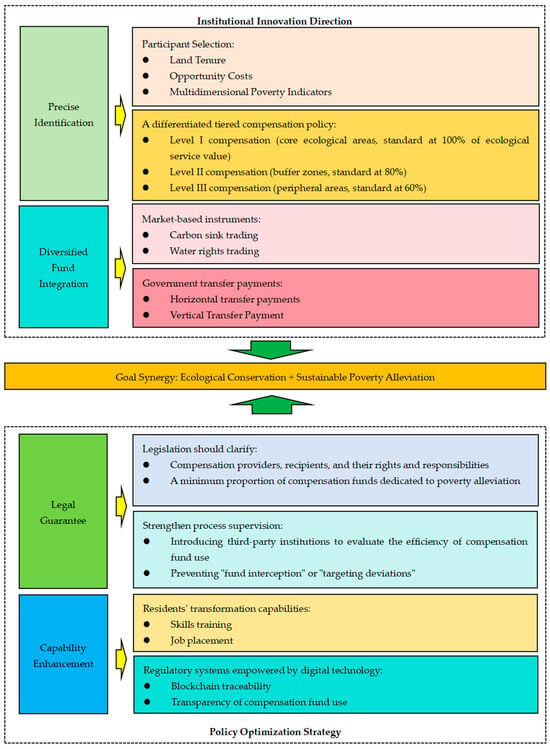

3.3. Long-Term Mechanism Design for Ecological Compensation and Poverty Alleviation Synergy

3.3.1. Institutional Innovation Direction

Ecological compensation in functional zones (MFOZs) must begin with precise identification, formulating differentiated compensation standards based on the distinct functional positioning of restricted and prohibited development zones. Wang Li’an et al. (2009), in their study on the relationship between ecological compensation and poverty alleviation in Western China [12], pointed out that the selection of impoverished participants for ecological compensation needs to comprehensively consider land tenure, opportunity costs, and transaction costs, determining compensation standard tiers through negotiation or investigation. For example, within restricted development zones, ecological function areas should prioritize calculating compensation amounts based on ecological service value (e.g., water conservation capacity, carbon sink capacity) and livelihood losses (e.g., direct economic losses from banning cultivation or logging). In contrast, agricultural product production areas need to consider the potential economic costs of restricted agricultural production [12]. Building on this, a differentiated tiered compensation policy can be detailed into three levels: Level I compensation (core ecological areas, standard at 100% of ecological service value), Level II compensation (buffer zones, standard at 80%), and Level III compensation (peripheral areas, standard at 60%). This not only reflects fairness but also stimulates the enthusiasm of local governments and residents to participate in ecological protection [15].

Regarding funding supply, the limitations of single-source government compensation necessitate exploring alternative funding structures. Integrating government transfer payments with market-based mechanisms represents a potential solution for diversifying funding streams. Some scholars [26] propose that market-based instruments like carbon sink trading and water rights trading can serve as supplementary funding sources. For instance, transforming ecological resources in impoverished areas into tradable assets through carbon sink projects can alleviate fiscal pressure while creating stable income for farmers. Concurrently, governments can regulate inter-regional benefit imbalances through horizontal transfer payments, such as exploring “beneficiary area–protection area” targeted compensation agreements in national key ecological function zones [1].

3.3.2. Policy Optimization Strategy

A legal framework is the cornerstone of the linkage between ecological compensation and poverty alleviation. Li Liang and Gao Lihong (2017) proposed constructing a “rights-based legal mechanism for ecological poverty alleviation,” [6] advocating for the legal clarification of compensation providers (e.g., beneficiary enterprises, local governments) and recipients (e.g., farmers in restricted development areas) and their rights and responsibilities. They also suggest stipulating a minimum proportion of compensation funds dedicated to poverty alleviation (e.g., no less than 30% of the total funds). For instance, in prohibited development zones like water source protection areas and natural heritage sites, legislation is needed to guarantee the development rights lost by residents due to ecological prohibition policies, require beneficiary regions or enterprises to fulfill compensation obligations, and establish breach of contract accountability clauses (e.g., imposing late fees for delayed compensation payments) [5]. Furthermore, policy design needs to strengthen process supervision, for example, by introducing third-party institutions to evaluate the efficiency of compensation fund use, preventing “fund interception” or “targeting deviations” [22].

Cultivating endogenous motivation is the key pathway for non-financial compensation. Restricted development zones need to enhance residents’ transformation capabilities through skills training and job placement [9]. For example, promoting alternative industries like the under-forest economy and ecological tourism in Grain for Green areas, supplemented by technical guidance and market linkage, can reduce reliance on traditional resources and form sustainable livelihood models. Combining intellectual compensation with policy support helps transform “blood transfusion” into “hematopoiesis”, breaking the dichotomy between ecological protection and economic development [17] and offering new approaches to comprehensively enhance the resilience of sustainable rural development. Regulatory systems empowered by digital technology can enhance the transparency of compensation fund use, laying an institutional foundation for subsequent technological deepening applications [13] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Ecological compensation and poverty alleviation synergy mechanism.

4. Discussion

This study provides compelling evidence of the significant synergistic potential between ecological compensation and targeted poverty alleviation within functional zones. This synergy stems from their inherent geographical coupling (the high overlap between ecologically fragile areas and poverty-prone regions) and complementary objectives (internalizing externalities to compensate for development rights losses, and capacity building to promote sustainable livelihoods). The following discussion aims to elaborate on the challenges of this study, its theoretical insights, and its limitations, while also offering recommendations for future research directions.

4.1. Institutional Paradoxes in Eco-Poverty Nexus

The synergistic potential between ecological compensation and poverty alleviation in key functional zones is fundamentally constrained by three institutional paradoxes. First, the “compensation disequilibrium syndrome” manifests in Jinzhai’s case, where forest conservation payments (580 USD/ha/year) lag 62% behind local opportunity costs (1500 USD/ha/year), creating a tripartite conflict between ecosystem valuation complexity (revealed vs. stated preferences), fiscal capacity limitations, and urgent livelihood demands. This structural imbalance induces perverse incentives (41% of monitored households reported reduced conservation effort) and poverty entrenchment (27% increase in multidimensional poverty indices). Second, the “dependency dilemma” in Southern Shaanxi reveals that 68% of poverty reduction gains derive from transfer payments rather than endogenous capacity building, risking welfare dependency (34.7% reduction in productive investments) and market competitiveness erosion. Third, the legal vacuum surrounding cross-jurisdictional compensation mechanisms—particularly benefit-sharing between upstream conservation zones (e.g., Jinzhai) and downstream beneficiaries (e.g., Hefei)—creates systemic governance fractures. The absence of standardized frameworks for compensation subjects (83% of cases), payment formulas (76% ad hoc determination), and accountability mechanisms (89% lacking third-party audits) perpetuates regional inequities and program fragility.

At a deeper level, these institutional paradoxes are rooted in and exacerbated by underlying governance failures, manifesting specifically as a “participation deficit” and an “accountability vacuum.” First, the “participation deficit” directly contributes to the structural imbalance in compensation standards (Paradox 1). Under the current top-down decision-making model, upstream residents—who bear the core responsibility for ecological protection—are often excluded from meaningful participation in negotiating and setting compensation standards. Their livelihood opportunity costs, local knowledge, and developmental demands are rarely fully incorporated into the evaluation system, resulting in compensation standards that reflect fiscal affordability rather than the true ecological contributions and sacrifices made. This deprivation of participatory rights is itself a manifestation of capability poverty, undermining the legitimacy and fairness of compensation policies from the outset and triggering perverse incentives or even resistance. Second, the “accountability vacuum” exacerbates the “welfare dependency” dilemma (Paradox 2) and entrenches the absence of legal frameworks (Paradox 3). On one hand, in the allocation and utilization of compensation funds, the lack of transparent, publicly monitorable accountability mechanisms leads to misallocation—either through fund diversion or egalitarian distribution—failing to target households most in need of capacity-building. Consequently, compensation devolves into short-term “welfare” rather than a long-term investment in development. On the other hand, the legal void in cross-regional compensation is essentially an institutional reflection of the political–economic power asymmetry between regions. When downstream developed regions, acting as “rational economic actors,” lack payment willingness, the absence of a higher-level, robust cross-jurisdictional governance mechanism to define responsibilities, enforce compliance, and impose penalties renders legal provisions mere “paper promises.” The case of Jinzhai County’s water supply to Hefei City epitomizes this lack of cross-regional accountability. Thus, without confronting these fundamental governance barriers, any institutional design confined to technical or economic adjustments will struggle to resolve the structural tensions between ecological protection and regional development.

4.2. Theoretical Implications: Enriching the Frameworks

This study operationalizes Sen’s capability approach within ecological poverty governance contexts, demonstrating that ecological compensation mechanisms—through economic opportunity creation (as evidenced in Shaanbei’s diversified livelihood programs) and public service enhancement (infrastructure investments in the Wudu case)—constitute effective pathways for multidimensional poverty alleviation. The research reveals a novel theoretical mechanism: the “ecological protection → opportunity cost accumulation → capability deprivation → poverty entrenchment → environmental degradation” vicious cycle, establishing critical intervention nodes (opportunity cost compensation, capability-building investments) to break this poverty–environment trap.

The findings advance SDG implementation frameworks by providing: (1) synergistic pathways integrating SDG1 (No Poverty), SDG2 (Zero Hunger), SDG6 (Clean Water), SDG13 (Climate Action), and SDG15 (Life on Land) through spatially explicit compensation designs; (2) a typology of compensation–investment portfolios demonstrating 23–37% greater poverty reduction efficacy when environmental safeguards are embedded in development planning (as quantified in Jinzhai’s agro-ecological transition); (3) institutional innovation pathways for reconciling biodiversity conservation with rural revitalization, contributing novel empirical evidence to the Global Environment Facility’s (GEF) Poverty–Environment Nexus framework.

4.3. Research Limitations and Future Directions

The study’s spatial scope exhibits inherent limitations. While focused on representative cases (Shaanbei, Jinzhai, Wudu) and international benchmarks (EU model), the generalizability of findings across China’s differentiated functional zones—particularly between prohibited development nature reserves and restricted development agricultural production bases—requires validation through multi-regional comparative studies.

While quantitative metrics (income increments, poverty reduction rates) are incorporated, the analysis demonstrates methodological gaps in micro-level econometric validation of synergistic mechanisms. Critical knowledge voids persist regarding (1) the cost–benefit ratios of alternative compensation modalities, (2) the causal pathways of capacity-building interventions, and (3) spatial–temporal variations in intervention efficacy. Future research could employ mixed-methods longitudinal panel data analyses combined with randomized control trials to enhance causal inference.

The discussion on institutional design, while conceptually significant, inadequately addresses meso-level governance complexities. Particularly underdeveloped are analyses of (1) power dynamics among stakeholders (local governments, enterprises, communities, and households), (2) institutional inertia in policy implementation, and (3) adaptive governance capacity in resource-dependent economies. Future studies should integrate political ecology perspectives with institutional analysis and development (IAD) frameworks to unpack these governance puzzles.

Future research could focus on innovating ecosystem service value monitoring and compensation mechanisms empowered by digital technology. For instance, blockchain technology, through smart contracts, can achieve full traceability and transparency of compensation fund flows. In Grain for Green projects, farmers’ ecological protection behaviors (e.g., tree survival rates, soil carbon sequestration) could be monitored in real time by IoT devices and uploaded to the blockchain, triggering automatic compensation payments and reducing administrative overhead [13]. Concurrently, the construction of ecological compensation performance evaluation systems needs to integrate multidimensional poverty indicators, such as capability deprivation and social exclusion, to dynamically adjust compensation standards and methods [27]. On the international level, China’s ecological compensation practices can align with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), drawing on design experience from mechanisms like the Global Environment Facility (GEF) to explore frameworks for cross-border ecological compensation cooperation [25]. Furthermore, it is necessary to improve horizontal compensation systems by promoting market-based compensation mechanisms between regions based on transactions like water resources and carbon sinks and integrating ecological compensation into the green “Belt and Road” initiative [5]. Through technological and institutional synergy, ecological-compensation-based poverty alleviation is poised to contribute a Chinese solution to the global sustainable development agenda.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

5.1. Conclusions

The synergistic effect of ecological compensation and poverty alleviation development demonstrates unique value against the backdrop of intertwined ecological fragility and poverty in China. Addressing the core question of “how to achieve the unification of externalizing internalization and endogenous development through institutional innovation,” this research indicates that a dual mechanism design involving differentiated compensation standards and legalized constraints can effectively transfer the external costs of ecological protection to beneficiary entities. Simultaneously, it reconstructs the capability approach of impoverished populations through green industry cultivation [22]. Existing studies further confirm that the essence of ecological-compensation-based poverty alleviation lies in using institutional design to transform the externalities of ecological protection into endogenous drivers for the development of impoverished areas, achieving a feedback mechanism between ecological and economic benefits [17]. The legalized framework of the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) contrasts sharply with the current lack of ecological compensation legislation in China; its practice of clearly defining compensation standards and accountability mechanisms for non-compliance through the EU Agricultural Law provides a direct reference for China in addressing issues of low compensation standards and insufficient legalization. The synergy between the two needs to be based on a high degree of coupling in geographical space and policy objectives, focusing on resolving problems such as ambiguous compensation standards, single funding sources, and targeting deviations. For example, practical cases like Grain for Green and horizontal watershed compensation demonstrate that ecological compensation can break the vicious cycle of “ecological protection → restricted development → poverty exacerbation” through opportunity cost compensation and livelihood transformation [22]. However, policy design must guard against the “compensation trap,” where over-reliance on financial compensation leads to passive dependency among the poor, neglecting the core function of ecological protection [6]. Therefore, strengthening legal constraints and coordinating market-based compensation tools, while clarifying the ecological priority attribute of ecological compensation, are key to balancing social equity and ecological efficiency.

5.2. Policy Implications

The findings of this study yield several concrete policy recommendations for strengthening the synergy between ecological compensation and poverty alleviation in China’s functional zones:

- (1)

- Legislative Framework Enhancement: Accelerating the formulation of dedicated ecological compensation legislation is critical to clarify the responsibilities of central and local governments, enterprises, and the public. Drawing on the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) “cross-compliance” mechanism, China’s *Ecological Compensation Regulations should establish dynamic linkages between compensation standards and ecological performance—for instance, reducing payments by 5% for every 1% decline in forest cover (verified via satellite monitoring). Additionally, legally mandated horizontal payment obligations should be imposed on downstream beneficiaries, such as industrial water users (e.g., 0.1 CNY/ton) and municipal suppliers (e.g., 0.2 CNY/ton), to internalize the costs of ecosystem services. However, implementing these recommendations faces dual challenges. First, there is significant political resistance from powerful downstream beneficiaries—such as industrial and urban stakeholders—who are accustomed to free or low-cost access to ecological resources. Any effort to internalize costs would inevitably disrupt their vested interests. Second, there are technical and trust-related challenges in performance monitoring. Even with advanced technologies like satellite remote sensing, ensuring the impartiality and accuracy of monitoring data while securing trust from all stakeholders remains a complex technical and governance issue.

- (2)

- Market-Based Policy Instruments: Pilot programs at the provincial level should introduce market-oriented tools, including “eco-label” certification (modeled after the EU Alpine region), directing at least 30% of horizontal compensation funds toward premium recovery for ecological products. Blockchain-based smart contracts can enhance transparency by automating fund disbursement linked to verifiable outcomes (e.g., automatic payments to farmers in Shaanxi’s Han River watershed based on carbon sequestration data). Concurrently, amendments to the Rural Revitalization Promotion Law should institutionalize a minimum 40% allocation of compensation funds for capacity-building initiatives, alongside binding performance benchmarks for local governments (e.g., ≥5% annual reduction in multidimensional poverty rates). Although market-based instruments hold great promise, their application in impoverished regions must contend with two major practical obstacles. The first is the risk of “elite capture” and the “digital divide.” Market-based benefits from ecological products or blockchain-enabled smart contracts may disproportionately favor well-informed, capital-endowed elites, while the most vulnerable populations—lacking digital literacy and initial capital—could be further marginalized. The second obstacle is the high institutional operating costs, including establishing certification systems, enforcing transaction oversight, and addressing market failures—all of which demand substantial public investment and capacity-building.

- (3)

- Integrated Governance Mechanism: A “twin-engine” approach combining legal constraints (e.g., compensation statutes) and market incentives (e.g., carbon trading) is essential for long-term sustainability. Integrating the EU CAP’s results-based payment model with China’s government-led process oversight could establish a closed-loop system encompassing statutory standardization, market-driven implementation, and digital monitoring. This would ensure accountability while leveraging market forces to optimize resource allocation. Achieving this ideal integrated governance hinges on overcoming long-standing administrative challenges in China’s bureaucratic system, particularly the “intergovernmental coordination dilemma” and “departmental silos.” Ecological compensation and poverty alleviation fall under the purview of multiple agencies—environmental protection, forestry, agriculture, finance, poverty alleviation, etc.—each with distinct, often conflicting, performance indicators (KPIs) and policy objectives, creating a fragmented “nine dragons governing water” scenario. Breaking down these “policy silos” and establishing a permanent governance platform with clear responsibilities and efficient coordination is crucial for translating top-level design into effective implementation. This represents not only a key institutional challenge but also a profound test of modernizing national governance capacity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Y. and F.Z.; methodology, X.Z.; formal analysis, Y.L.; resources, R.G.; data curation, Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Y., X.Z. and Y.L.; writing—review and editing, F.Z. and R.G.; supervision, F.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Project of Information and Communication Company of Gansu Power Company, State Grid of China (Grant No. 52272323000C).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors M.Y., X.Z., and R.G. were employed by the Information and Communication Company of State Grid Gansu Electric Power Company. They did not introduce any conflicts of interest in data collection or interpretation. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

References

- Meng, Z.; Zhu, C.; Qu, A.; Du, Y. Study on the Ecological Compensation Approaches for Functional Zones in China. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2008, 21, 139–144. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cao, S.; Wang, Y.; Duan, F.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Z.; Fang, N. Coupling relationship between eco-environmental vulnerability and economic poverty in poverty-stricken areas of China: An empirical analysis based on 714 poverty counties in contiguous poverty-stricken areas. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2016, 27, 2614–2622. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Hao, L.; Deng, W. Research on Ecological Compensation Mechanism in Jinzhai County Based on Poverty Alleviation Development. Anhui Agric. Sci. Bull. 2014, 20, 5–7. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. Overcoming Poverty in Development: Summary and Evaluation of China’s 30 Years of Large-Scale Poverty Reduction Experience. Manag. World 2008, 24, 78–88. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Xu, L. Cooperative Game Analysis of Ecological Compensation-based Poverty Alleviation. Jiangxi Soc. Sci. 2014, 34, 69–76. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Gao, L. On the Legal Connection between Ecological Compensation and Targeted Poverty Alleviation in China’s Key Ecological Function Zones. J. Henan Norm. Univ. Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2017, 44, 59–65. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W. Research on China’s Multidimensional Relative Poverty Based on the Capability Approach. Ph.D. Thesis, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, X. Action and Effect Evaluation of Rural Sustainable Development Based on SDGs. Master’s Thesis, Nankai University, Tianjin, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, W. Research on the Application of Ecological Economics in Functional Zones. Ph.D. Thesis, Dongbei University of Finance and Economics, Liaoning, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S. Research on the Ecological Compensation Mechanism for Cultivated Land Protection in Guangdong Province under the ”Dual Carbon” Goal. Master’s Thesis, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Kong, D.; Jin, L. Does Ecological Compensation Contribute to Poverty Reduction? An Empirical Analysis of Three Counties in Guizhou Province Based on Propensity Score Matching Method. Rural. Econ. 2017, 35, 48–55. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Zhong, F.; Su, F. Research Framework on the Relationship between Ecological Compensation and Poverty Alleviation in Western China. Econ. Geogr. 2009, 29, 1552–1557. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shen, F.; Hu, Z. Endogenous Causes and Solutions for Capability Poverty among Digitally Disadvantaged Groups in Rural Areas: Discussion Based on Sen’s “Capability Approach” Theory. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2024, 24, 112–123. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Qiu, F.; Ma, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Meng, Z.; Yan, Q. Preliminary Study on the Theory and Method of Regional Major Function Zoning. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2007, 27, 136–141. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H. Review of Research on Ecological Compensation in China’s Functional Zones. West. Financ. Account. 2018, 17, 73–76. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom. In The Globalization and Development Reader: Perspectives on Development and Global Change; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1999; p. 525. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, X.; Ge, Y. Research on Ecological Compensation-based Poverty Alleviation and Its Operational Mechanism. Guizhou Soc. Sci. 2017, 38, 149–153. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Mei, J. The EU Common Agricultural Policy: Green Ecological Transformation, Reform Trends and Development Implications. World Agric. 2022, 44, 5–14. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westhoek, H.; Van Zeijts, H.; Witmer, M.; Van den Berg, M.; Overmars, K.; Van der Esch, S.; Van der Bilt, W. Greening the CAP: An Analysis of the Effects of the European Commission’s Proposals for the Common Agricultural Policy 2014–2020; PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2012.

- Wang, A.; Ge, Y.; Geng, X. Analysis of Stakeholder Behavior Selection Mechanism in Ecological Compensation of Water Source Protection Areas. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2015, 36, 16–22. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fang, L.; Qu, X.; Wang, C. Ecological Compensation and Poverty Reduction in the South-to-North Water Diversion Source Area in Southern Shaanxi. Macroecon. Manag. 2014, 30, 80–82. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zheng, K. Mechanism Analysis and Long-term Mechanism Research on Ecological Compensation-based Poverty Alleviation. Qiushi 2012, 19, 43–46. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Pe’er, G.; Lakner, S. The EU’s common agricultural policy could be spent much more efficiently to address challenges for farmers, climate, and biodiversity. One Earth 2020, 3, 173–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Shi, J.; Su, Z.; Ma, P. International Experience and Implications for Ecological Protection and Compensation of Cultivated Land: Based on the EU Common Agricultural Policy. China Land Resour. Econ. 2021, 34, 37–43. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; He, J. On the Institutional Connection between Ecological Civilization Construction and Poverty Alleviation Development in Western China: An Investigation with Ecological Compensation as the “Interface”. Acad. Forum 2017, 40, 105–110. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Geng, S.; Li, K.; Liu, Z. Research on Forest Ecological Benefit Compensation Mechanism in Hebei Province Based on Carbon Sink Trading under the “Dual Carbon” Background. For. Resour. Manag. 2023, 52, 10–16. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ju, Q.; Wang, S. Improvement of the Legal System for Cultivated Land Ecological Compensation under the Synergy of Ecological Poverty Alleviation: Based on the Perspective of Legal Policy Science. Macroecon. Res. 2017, 37, 184–191. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).