Abstract

As the world recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic, the tourism industry is experiencing a surge in demand. While this growth is essential for economic recovery, it also presents significant challenges in terms of sustainability. The tourism industry is under increasing pressure to adopt business practices that align with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Corporate social responsibility (CSR) has emerged as a critical framework for addressing these challenges. This study seeks to understand how CSR can contribute to the achievement of the SDGs within the tourism industry, with a focus on identifying the best practices of management. A systematic literature review was conducted to address this research question. A comprehensive search of the literature was performed using Boolean operators in databases including Web of Science, ABI/Inform Collection, Business Source Complete, and Emerald Insight. After applying pre-determined inclusion criteria, the selected studies were analysed using the population/problem, intervention, comparison, and outcome (PICO) framework. The quality of the evidence was assessed using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines to ensure the rigor and reliability of the findings.

1. Introduction

Various forms of environmental issues pose a serious threat to the natural environment, a problem that can be mitigated by environmentally sustainable consumption, which has a positive impact on society [1]. In this regard, there is a growing number of societal actors who are pointing at the tourism industry and its development as the root cause of a lot of serious environmental damage [2]. Therefore, the development of sustainable products is becoming increasingly important in the industry, and environmental sustainability is turning into one of the most important issues to be addressed [1].

As society’s expectations regarding the environment continue to evolve, businesses are coming up with strategies to manage sustainable practices [3], such that many companies now recognise the importance of developing sustainable behaviour that is based on the premise of consuming existing resources at a rate that does not compromise the wellbeing of future generations [4].

1.1. Contribution to the Literature

Social issues, including fair trade and the reduction in poverty, have been at the forefront of the debate on sustainable tourism [5] since the United Nations’ approval of the eight Millennium Development Goals [6], which stem from the current seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (hereinafter, SDGs). Even though the significant impact of tourism on the environment has been recognised, the literature that studies the relationship between tourism activities and the SDGs is imprecise and mainly limited to mere mentions of sustainable tourism or, even more occasionally, to indicating the importance of promoting and achieving the SDGs, e.g., [7].

Even though academics and professionals agree on the important role of businesses in attaining the SDGs, there is still scant research that would enable them to understand the strategies that might help the private sector with this concern [8]. Furthermore, the successful implementation of the SDGs involves practical challenges that have yet to be studied, e.g., [9].

Sustainability, as a complex process that has social, economic, and environmental dimensions [1], is an objective that must be pursued by all forms of tourism, no matter the scale of operations [5].

1.2. Research Aim

Based on the above and following the quality indications contained in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement (hereinafter, PRISMA 2020) [10], the aim of this research is to discover to what extent the application of CSR practices in the tourism industry currently contributes to achieving the SDGs and, if possible, to present the best practices. Tourism, particularly, is being called upon to play an important role in the search for sustainable solutions for people and the planet because it has the potential to contribute, directly and indirectly, to all SDGs, but especially SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth), SDG 12 (responsible consumption and production), and SDG 14 (life below water) [11].

The intent is to achieve this via a systematic literature review (hereinafter, SLR) that will respond to the following research question made under principles of a population/problem, intervention, comparison, and outcome (PICO) framework:

- RQ: How does the implementation of CSR initiatives in the tourism industry contribute to the achievement of its SDGs?

The paper’s structure is as follows: presented after this is the theoretical framework around tourism, sustainability, CSR, and the SDGs, followed by an explanation of the design of the research and the methodology (an SLR) that it used. Then, the results derived from the synthesis of the information from the studies selected in the SLR are identified for subsequent discussion, thereby allowing the proposal of some practical and academic conclusions.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Stimulus–Organism–Response Theory

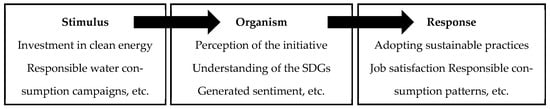

Given that this study aims to ascertain whether the implementation of CSR policies in the tourism industry promotes the achievement of the SDGs—which could be verified through the behaviours of individuals and organisations within the industry itself—it is considered appropriate to frame its theoretical foundation around the stimulus–organism–response (SOR) model [12], a key principle of environmental psychology theory [13].

The SOR model, proposed in 1929 [14] as an extension of the classical theory based on the stimulus–response model suggested two years earlier [15], posits that external environmental factors (stimuli, S) influence the responses of individuals and organisations (responses, R) through the mediation of their internal states (organisms, O) [12]. As illustrated in Figure 1, its three constructs determine the outcome of an event in terms of behaviour [16]. These specific behavioural responses can be both affective and cognitive, as environmental factors act as stimuli, eliciting psychological reactions in individuals that, in turn, shape their subsequent actions [17].

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework of the study. Source: produced by the authors.

It is pointed out [18] that the SOR model stands as a robust and adaptable theoretical framework, highly effective for exploring the intricate connections between stimuli, internal states, and observable human behaviours. Its extensive application across diverse disciplines underscores its foundational importance in various research contexts, having been commonly adopted in hospitality management research, particularly within hotel and restaurant settings.

2.2. Stimulus: Implementing CSR Policies in the Tourism Industry

CSR is a company’s response to the challenges of sustainable behaviours, in such a way that a business can call itself sustainable by minimising its negative impact, both internally and externally [19]. To adopt CSR, organisations should implement strategies that involve modifying daily management routines, improving communication practices, and reducing their environmental impact [20]. Additionally, this serves to emphasise the importance and influence of education on sustainable thinking [21].

Hospitality firms have increasingly invested in CSR initiatives in recent years, including enhancing employee well-being and engaging with local communities. These efforts aim to mitigate negative impacts and improve quality of life for local communities [22]. However, the value of CSR in tourism is a controversial subject [23], because competitiveness and profitability, as the determining factors of sustainability in the industry, along with other ones such as a short-term mindset, the pressure to maximise profits, scant financial resources, and a lack of awareness of the economic benefits of CSR actions, limit the adoption of the appropriate strategies [24].

2.3. Organism: Lights and Shadows in Tourism Industry

The tourism and accommodation industry is one of the biggest in the world and an important pillar of economic development [25], seeing as it makes a significant contribution to the creation of employment, especially among women, young people, and immigrants [26]. In 2019, the industry generated 10.4% of the global gross domestic product (GDP) and in 2022, travel and tourism contributed to 7.6% of the global GDP, which supposed a 22% increase compared to the previous year and only 23% less than 2019 levels [27]. The year 2024 saw international tourism recover from the worst crisis in its history, triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic, with 1.4 billion international tourist arrivals recorded worldwide [28]. During the first quarter of 2025, and compared to 2024, this industry grew by 5%, which put it 3% above the levels recorded in 2019, the year before the pandemic [29].

But it has been demonstrated that tourism generates immediate local impacts on air quality, water resources, soil, and biological systems, alongside indirect consequences stemming from the manufacturing and transportation of goods. These effects are primarily driven by atmospheric emissions, solid and liquid waste generation, and the consumption of water, energy, and raw materials [30].

In this regard, and despite the social and economic benefits arising from this industry, it is unsurprising that hotels and resorts face criticism due to their numerous impacts on the natural, social, and economic environments, which include contributions to climate change, air and noise pollution, biodiversity loss, waste generation, and other social and economic issues [31].

In fact, it is predicted that by 2050 there will be a 251% increase in the amount of solid waste from the tourism industry [32]. Furthermore, tourism-related transport accounts for 22% of the world’s total CO2 emissions. By 2030, these emissions are expected to rise by 25% over 2016 levels, representing 5.3% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions [33]. In this regard, the aviation sector is overwhelmingly responsible for tourism’s carbon footprint, generating approximately 95% of its CO2 emissions [34]. Therefore, the tourism industry could be considered one of the biggest consumers of natural resources in the world [35].

2.4. Response: Sustainable Practices in Tourism Industry Aligned with SDGs

To the contrary above, it could be argued that hotel chains are proactively implementing measures to reduce waste and plastic consumption [36], mitigate climate change impacts, and promote initiatives aimed at water conservation. These measures include using energy-efficient light bulbs, programmed lighting, solar-powered hot water systems, reducing toilet tank volume, and installing water-saving technologies in bathrooms [31]. To further promote guest engagement in environmental initiatives, accommodation providers could incentivise their customers with discounts or charitable donations. Such strategies aim to encourage guest participation in sustainable behaviours, fostering environmental awareness and a sense of responsibility [37].

Consequently, it is no surprise that sustainability has gained relevance in the tourism industry, where companies must play their part in good governance initiatives [38] and encourage the sustainable growth of tourism destinations [39]. The latter is a concept that can be defined as a process that allows the satisfaction of present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to satisfy their own needs, and it is conditioned by economic growth, environmental protection, and social development [19].

But the tourism and sustainability relationship existed previously, even before the term ‘sustainable development’ was coined [40]. The growth of tourism has increasingly been guided by sustainability principles, particularly since the 1980s, due to the negative effects of mass tourism [40] and the impacts of overtourism [41], which significantly impacts popular destinations by overwhelming local infrastructure, disrupting communities, and degrading the environment [42].

As a holistic concept, sustainable tourism encompasses not only environmental concerns but also social, economic, cultural, ethical, and political dimensions [43]. It should use its environmental resources conscientiously, guarantee viable and long-term economic options, respect the socio-cultural authenticity of host communities, conserve the latter’s cultural heritage and traditional values, and, lastly, contribute to inter-cultural understanding and tolerance [44].

3. Methodology

3.1. Previous SLRs

Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 statement, the reasoning behind this SLR was to start with a description of the prior knowledge on the topic to date and the existing uncertainties [10], as detailed in Table 1.

The PRISMA methodology is frequently favoured over other established techniques across various disciplines, particularly within tourism publications, largely due to its extensive scope and the enhanced consistency it brings to reviews [45,46].

Table 1.

Previous SLRs in CSR–SDGs–tourism.

Table 1.

Previous SLRs in CSR–SDGs–tourism.

| Citation | Findings/Results | Application | Limitation/Potential Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| [47] | Hotel employees’ perceived CSR influences their loyalty towards their workplace. | Enhancing human resource management (HRM) activities could contribute to achieving the SDGs. | No mention of specific SDGs that could be attained through improved HRM policies. No demonstrated link between improving staff perceptions of CSR policies and achieving SDGs. |

| [48] | The authors argue that tourism perpetuates job precarity within capitalist economies. | Lack of contribution from the tourism industry towards achieving SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth). | Limited focus on CSR and absence of best practices to eradicate job precarity in tourism. |

| [4] | Identification of factors stimulating sustainable practices in wine tourism, from both demand (consumer awareness) and supply (competitiveness, innovation, territorial development) perspectives. | Maintenance of sustainable consumption and production patterns (SDG 12). | Lacks identification of specific sustainable practices associated with the stimulating factors. Standardised procedures are limited to the wine tourism sector. |

| [1] | Psychosocial theories identify factors leading to environmentally sustainable consumption behaviours in tourism and accommodation industries. | It is defined that environmentally responsible consumption can promote sustainable habits. | SDGs are mentioned only in the conclusions, without specifying which goals tourism can address or how. |

| [49] | Descriptive literature review demonstrating intersections between CSR, circular economy, and work–life balance, which impact quality of life. | Improved understanding of these intersections could contribute to long-term sustainability objectives. | Proposed CSR practices in tourism are linked to SDG 3, which is not specifically prioritised for the tourism industry. |

| [3] | Research on CSR in tourism is a rapidly growing field, identifying CSR as a key driver for industry success and growth. | Successful CSR implementation requires stakeholder identification and integration of customers and employees into CSR strategies. | Research gaps include (1) the direct effects of CSR on employees, customers, and business performance, and (2) mediating/moderating relationships between CSR and various factors. |

| [8] | Identification of three categories enabling SDG implementation in companies: external, internal, and combined factors. | Academically, educators play a crucial role in instilling sustainability values. Governments must enhance SDG awareness for nationwide commitment and business adoption. | Does not specifically address the tourism industry; while certain SDGs are mentioned, none are explicitly tied to tourism. |

| [50] | Previous studies on tourism sustainability exhibit the following common shortcomings: lack of in-depth analysis, narrow methodological scope, insufficient empirical application, and limited real-world translation. | Emerging fields with potential include sustainable infrastructure and services, livelihoods, and destination management. | The identified research opportunities lack a connection with both general and tourism-specific SDGs. |

Source: produced by the authors.

As can be inferred from the content of Table 1, and to the best of these authors’ knowledge, no country or company fully addresses all SDGs, let alone those directly related to the tourism industry. Although the significant environment tourism impact has been recognised, research on tourism activities and the SDGs relationship remains imprecise and most studies merely mention sustainable tourism or indicate the importance of promoting and achieving the SDGs, e.g., [7]. This is a significant gap because poorly managed tourism can negatively impact people, the planet, prosperity, and peace [24].

Previous research in the literature merely highlights how job insecurity persists in tourism, contributing to social and economic disparities, particularly regarding SDG 8 [48], and identifies CSR practices in hotels and their impact on employee quality of life [49]. Finally, in relation to the wine tourism industry, factors such as supply-side competitiveness, innovation, and territorial development, alongside demand-side consumer consciousness and responsible consumption, are enumerated as potentially impacting SDG 12 [4].

Accordingly, and given the recognised importance of the trend of research on tourism and CSR in sustainability [51], there is a need for an SLR that summarises how CSR initiatives affect the implementation of the specific SDGs for the tourism industry.

3.2. Search Strategy

Identifying pertinent studies for a review can involve several search methodologies, such as database queries, forward citation tracking, and the direct, manual examination of individual journals. Each of these approaches offers distinct advantages and serves varied research applications [52]. According to Bramer et al. [53], this SLR utilised various electronic databases not only to attempt cover the largest possible number of studies but also to avoid the risk of results bias [54], the risk of selection bias [55], and to eliminate the possibility of creating an incorrect association between the intervention and the result [56].

The risks of bias arising from searching exclusively in electronic databases were mitigated using the snowballing technique, e.g., [57], which increased, as well, the scope of the search to identify the greatest possible amount of evidence [58]. Therefore, the search strategy used in this SLR was hybrid [57] to attempt to make the most of the invested effort [59] and so that its application was conceptually correct [60]. Lastly, to avoid any risk of bias derived from the published language studies, no restriction was placed, e.g., [58].

Given that it has been suggested that the selection of databases could have a significant effect on the conclusions of reviews [52], the recommendation to use multiple databases [52,53] has been followed to achieve the highest probability of finding all of the potential literature relevant to the research question [61]. This is why searches were run in both electronic databases specific to the study’s discipline and in multidisciplinary databases [61]. Specifically, searches were conducted in the Web of Science (hereinafter, WoS), ABI/INFORM Collection, Business Source Complete (EBSCOhost), and Emerald Insight databases, the rationale for which is shown in Table 2. There is no conclusive answer regarding the optimal number of databases for study searches, but it appears advisable to use at least two [62], considering that this search process is laborious, time-consuming, and search syntax is often specific to each database [53]. The number of databases selected here aimed to strike the right balance between sensitivity and specificity of results [63].

Table 2.

Rationale behind the chosen electronic databases.

To gain a high sensitivity, a broad range of search terms (keywords) were used [58] and linked together using the OR/AND Boolean operators, e.g., [69] as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Keywords used in electronic database searches.

Following Mahood et al. [70], studies featured in the so-called grey literature were also accepted, not only to adhere to the recommendation of other authors [71] but also because peer review itself can sometimes be unreliable [72] and cannot be considered a definitive guarantee of quality research [73].

3.3. Studies Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were based on the stated RQ [74]. To categorise the reasons for excluding studies (see Table 4) from this research [75], these criteria were formulated using the PICO acronym [76] and aligned with the framework proposed by Richardson et al. [77].

Each of the studies was independently scrutinised by two reviewers, and in cases where there was disagreement regarding the inclusion of a particular study, a consensus was reached through discussion among all reviewers [10,78,79].

Table 4.

PICO categorisation of causes for the exclusion of the studies.

Table 4.

PICO categorisation of causes for the exclusion of the studies.

| REJECTED—Exclusion Criteria | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| PICO Category | Explanation | Exclusion Code | Description |

| Population (P) | The studies returned from the databases were not related to tourism in any way. | EC1 | The content of the summary, the title heading, or either of these was not related to tourism. |

| Intervention (I) | The returned studies were in no way related to the implementation of actions that could be included in the field of CSR. | EC2 | The content of the summary, the title heading, or either of these was not related to CSR. |

| Comparison (C) | Lack of access to the document or access limited to only parts of it. | EC3 | Access to the document summary only. The document is not accessible [80]. |

| Outcomes (O) | The studies did not help to fulfil the objective of this SLR, or their results were not related to the SDGs. | EC4 | The content of the summary, the title heading, or either of these was not related to the SDGs. |

| EC5 | Does not satisfy the aim of the SLR. | ||

Source: produced by the authors, based on Edinger and Cohen [75].

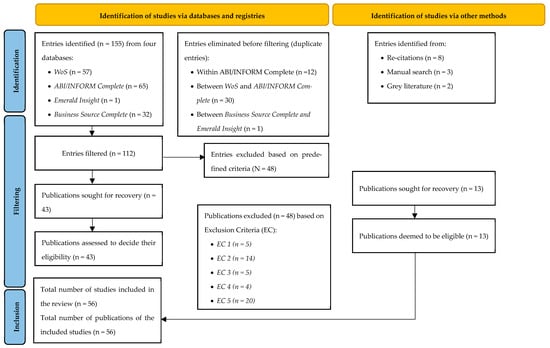

Each of the studies was independently scrutinised by two reviewers, and in cases where there was disagreement regarding the inclusion of a particular study, a consensus was reached through discussion among all reviewers [10,78,79]. To summarise, the process followed in this SLR can be seen in Figure 2 below.

3.4. Information Synthesis

Studies that passed through the proposed exclusion filters contained in this SLR process flow (see Figure 2) were processed with the problem, intervention, comparison, outcomes, and context (PICOC) methodology to synthesise their information.

Specifically, for each, the patient, population, or problem addressed (P) was identified, followed by the intervention (I) performed (the study’s independent variable). Next, the comparison framework (C), if present, was indicated. The derived outcomes (O), i.e., the study’s dependent variable, were then identified. Finally, notes on the context (C) that might be useful for understanding the selected study were extracted.

PICO framework is widely accepted among scholars as a universal approach for formulating a RQ or planning a search strategy, but it does not apply to most types of evidence, so researchers and experts in many fields have introduced different approaches and frameworks for certain types of evidences/studies [81]. Consequently, in the fields of social SR [82] and economic/cost-effectiveness, researchers and experts have introduced the PICOC approach for the evidence/studies derived from it [81].

Figure 2.

Diagram of the SLR process flow. Source: adapted from Page et al. [83].

4. Results

Following the synthesis of information from the included studies, the findings were then grouped (see Table 5 and Table 6) using thematic categories that emerged during the review process [84] and that were based on the following facilitators for the companies’ achievement of the SDGs [8]:

External enablers: industry, tools, and education.

- Industry. As regards the greater or lesser ease of realising sustainable activities, tourism is the direct actor in three SDGs: SDG 8, which involves the inclusivity and sustainability of economic growth and employment; SDG 12, which is about sustainable production and consumption, and; SDG 14, which addresses the conservation of submarine life via the sustainable use of the oceans and marine resources [85,86]. This is also congruent with the fact that European institutions are highlighting the sustainable tourism potential of geographic areas with a high level of ecological integrity [87]. In short, tourism has a clear responsibility as an industry that is capable of contributing and making a difference as regards sustainable development [88]. It, therefore, seems logical to consider the tourism industry as an external facilitator to achieve the SDGs. It is, therefore, present in the 56 studies analysed in this SLR.

- Tools. This concept is related to a commitment to achieving the SDGs and using qualitative methods (i.e., logistic regressions) or quantitative methods (e.g., the analysis of cases or content) to assess and monitor the usage of these tools.

- Education. From primary education, through secondary education, to university or business school, this can reduce the distance between the theory and practice of sustainability. This does not, therefore, refer to the training received by employees at their jobs.

Internal enablers: business characteristics, governance, innovation.

- Business characteristics. A company’s employees’, interest groups’, and departments’ commitment to the SDGs.

- Governance (CSR). Leadership styles, a greater or lesser presence of women in managerial positions, etc.

- Adoption of innovation and technology. There is a proven connection between this and the achievement of SDGs (innovative business models, digitalisation, innovative practices, etc.), for example via practices related to circular economy, industry 4.0 technologies, collaborative economy, thinking systems, bioeconomy, or marketing related to a cause.

Combined facilitators:

- Public–private alliances. Between governments and businesses, as a tool that guarantees the achievement of the SDGs.

Table 5.

Results according to enablers of SDGs.

Table 5.

Results according to enablers of SDGs.

| External Enablers of SDGs (External Environment) | Internal Enablers of SDGs (Internal Environment) | Enablers Combination | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tools | Company Characteristics | Innovation | |

| [19,20,21,22,23,25,26,35,47,49,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131] | [89,132] | [22,102,103,108,133,134] | [93] |

| 53 studies | 2 studies | 6 studies | 1 study |

Source: produced by the authors.

The studies selected in this SLR reflect the importance given to complying with the following SDGs: SDG 3 (good health and well-being) via CSR practices that affect the well-being of employees in the tourism industry [96,102,105,132]; SDG 4 (quality education) by teaching younger travellers about values related to sustainability [124]; SDG 5 (gender equality) via equality in the application of CSR practices [117]; SDG 6 (clean water and sanitation) via the installation of seawater treatment plants in cruise ships [100]; SDG 7 (affordable and clean energy) with the fostering of sustainable mobility, renewable energy, and collaborative economy in theme parks [122]; SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth) via the comparison, in three hotel chains, of the benefits that the application of CSR initiatives has on employees [127], or the use of indicators to measure the growth of inclusivity in the tourism industry [117]; SDG 12 (responsible production and consumption) via cruise companies’ investment into investigating materials that degrade more rapidly [100], the reduction in fuel consumption [117], and the progressive elimination of plastics, as well as environmental awareness and training, and circular economy in theme parks [122]; SDG 13 (climate action) via the incorporation of technological solutions that reduce toxic gas emissions in the cruise ship sector [100], or more regulation of CO2 emissions in airline companies [117]; SDG 14 (life under water) via the installation of waste water purifiers on cruise ships [100] or reducing the fuel consumption of airplanes [117]; SDG 15 (life on land) via the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by airline companies [117]; and, lastly, SDG 17 (partnerships for the goals) by proposing partnerships between tourism companies and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to attain the goals [101].

Seraphin and Vo Thanh [124] highlighted the role of tourism in achieving SDG 4 (quality education) by educating children about sustainability practices during family vacations. This aligns with Palau-Pinyana et al.’s [8] identification of education as an external enabler for SDG achievement in the tourism industry.

Table 6.

Grouped SLR results.

Table 6.

Grouped SLR results.

| Study No. | Citation | SDGs External Enablers | SDGs Internal Enablers | External/Internal Enablers Combination | Description | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industry | Tools | Education | Company Characteristics | Governance | Innovation and Technology | ||||

| 1. | [89] | X | X | X | Green human resource management practices (recruitment, selection, training, behaviour). | ||||

| 2. | [90] | X | X | A comprehensive pre-travel advisory detailing the potential risks and expected outcomes of medical treatments that may be sought at the tourist destination. | |||||

| 3. | [91] | X | X | Case studies (qualitative approach). | |||||

| 4. | [92] | X | X | Analysis of tourists’ behaviour related to green tourism sustainability. | |||||

| 5. | [93] | X | X | X | Government policies and initiatives promoting CSR among SMEs. | ||||

| 6. | [94] | X | X | Proposal of four strategies for achieving sustainable tourist cities, based on an environmental ethics model, with a particular focus on the role of local communities. | |||||

| 7. | [95] | X | X | Empowering marginalized groups through social tourism enterprise development (cooperatives, worker-owned companies, social enterprises, etc.) | |||||

| 8. | [96] | X | X | In-depth interviews. | |||||

| 9. | [97] | X | X | Implementation of green practices (energy conservation, waste management, green purchasing) in five-star hotels. Training of hotel employees in the implementation of these practices. | |||||

| 10. | [98] | X | X | Embedding of socially and ethically responsible practices in the workplace, empowering employees to innovate and contribute to more sustainable work practices. | |||||

| 11. | [19] | X | X | Outbound CSR activities in the hospitality industry, with a focus on environmental sustainability, social responsibility, and community engagement. Inbound CSR initiatives, centred on workplace relations, human rights, and employee development. | |||||

| 12. | [99] | X | X | Incorporating environmental initiatives into hotel marketing strategies. | |||||

| 13. | [133] | X | X | Deployment of green technology in tourist destinations. | |||||

| 14. | [22] | X | X | X | Case studies, using content analysis, on (CSR) within the circular economy. | ||||

| 15. | [100] | X | X | Comprehensive analysis of sustainability reporting by the top four global cruise companies. | |||||

| 16. | [101] | X | X | Content analysis of partnerships formed by cruise companies to achieve the SDGs. | |||||

| 17. | [49] | X | X | Case study collection to assess the effects of CSR practices on work–life balance. | |||||

| 18. | [102] | X | X | X | Case studies to examine the integration of CSR practices into the circular economy, with a focus on improving quality of life. | ||||

| 19. | [134] | X | X | Ethical and ecological management to foster innovative behaviours and knowledge sharing among hotel employees. | |||||

| 20. | [132] | X | X | Workplace-focused CSR initiatives aimed at enhancing quality of life. | |||||

| 21. | [103] | X | X | X | Recording neural activity of visitors in different environments of a green hotel to determine their level of engagement and emotional response. | ||||

| 22. | [20] | X | X | Regression analysis to predict the number of hotels that will adopt and report on Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) standards in the future. | |||||

| 23. | [104] | X | X | Developing indicators and measures of social justice in Spanish hotel workplaces. | |||||

| 24. | [26] | X | X | Exploring CSR practices in Spanish hotels through a case study analysis of their reports. | |||||

| 25. | [105] | X | X | Exploring CSR initiatives in the hospitality, aviation, and fast-food industries through case studies. | |||||

| 26. | [25] | X | X | Assessment of compliance with Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) sustainability reporting standards. | |||||

| 27. | [106] | X | X | Electronic survey of hotel and tourism agency executives to assess the effects of CSR initiatives on Saudi Arabia’s tourism sector. | |||||

| 28. | [23] | X | X | Single-case study to determine the impact of CSR programs on sustainable development. | |||||

| 29. | [107] | X | X | In-depth interviews with employees from hotels, airlines, and tour operators. | |||||

| 30. | [108] | X | X | X | Development of a model to assess the sustainability impacts of green marketing strategies (cause-related marketing). | ||||

| 31. | [109] | X | X | In-depth interviews with experts to develop a conceptual framework for ethical and CSR dimensions in Taiwan’s tourism industry. | |||||

| 32. | [110] | X | X | Structural equation modelling (SEM) to determine the relationships between perceived green value, green attitude, and environmental CSR. | |||||

| 33. | [111] | X | X | Using SEM to explore the determinants of green consumption in Pakistan’s tourism sector. | |||||

| 34. | [112] | X | X | Exploring employees’ perceptions of CSR in the accommodation sector using SEM. | |||||

| 35. | [113] | X | X | Case studies in Namibia to determine the effects of CSR practices on poverty alleviation in the tourism sector. | |||||

| 36. | [47] | X | X | SEM analysis to assess the impact of perceived CSR on the commitment and loyalty of highly educated hotel employees. | |||||

| 37. | [114] | X | X | Employing quantile autoregressive distributed lag econometric methods to examine long-term relationships between green technological innovations, sustainable tourism, economic growth, financial development, and ecological sustainability. | |||||

| 38. | [115] | X | X | Case studies of the implementation of sustainable tourism initiatives. | |||||

| 39. | [116] | X | X | Analysis of social responsibility indicators among Bulgarian hotels. | |||||

| 40. | [117] | X | X | Utilisation of disaggregated indices to ascertain the relationship between corporate social responsibility and corporate financial performance. | |||||

| 41. | [118] | X | X | Comparative analysis of CRS practices and actions reported by the world’s largest cruise companies. | |||||

| 42. | [119] | X | X | Applied content analysis of sustainability-related information reported by Spanish hotels. | |||||

| 43. | [120] | X | X | Comparative case study of hotel chain and airline company, to determine how they implement CSR in their operations and impact the SDGs. | |||||

| 44. | [121] | X | X | Single case study on the green management of the supply chain in hotels. | |||||

| 45. | [122] | X | X | Case studies from various parts of the world concerning CSR actions undertaken by the theme park industry. | |||||

| 46. | [123] | X | X | Investigation into the involvement of staff in corporate social responsibility in 24 accommodation units in Romania. | |||||

| 47. | [124] | X | X | Design of animation programs for children visiting resort mini clubs aimed at fostering sustainability awareness. | |||||

| 48. | [125] | X | X | Creating public awareness of their role in environmental conservation by contributing to pollution prevention. | |||||

| 49. | [126] | X | X | Using structural equation modelling (SEM) to examine the relationship between green innovation performance and leadership in Saudi Arabian hotels. | |||||

| 50. | [127] | X | X | Qualitative comparison of CSR initiatives in three hotel brands. | |||||

| 51. | [128] | X | X | Using SEM to determine the emotions experienced by hotel guests in China. | |||||

| 52. | [129] | X | X | Using SEM to examine the influence of perceived corporate social responsibility on employees’ relationships with the company, their well-being within the company, and their commitment to green behaviour. | |||||

| 53. | [21] | X | X | Comparative study of three cases of CSR practices in hotels. | |||||

| 54. | [35] | X | X | Conceptual literature review on green human resource management and environmental CSR practices. | |||||

| 55. | [130] | X | X | Using SEM to determine the relationships between performance and environmental impacts in Spanish hotels. | |||||

| 56. | [131] | X | X | Application of SEM to examine the influences of four dimensions of the concept of corporate citizenship on the performance of accommodation businesses. | |||||

Source: produced by the authors.

In terms of the various tools that could be used to generate commitment to the SDGs and to assess their implementation, i.e., the last of the external facilitators of achieving the SDGs [8], the studies found in this SLR opted for the following:

- The use of qualitative methods based on the analysis of cases [22,23,26,91,102,105,108,115,121,122]; content analysis [100,119]; in-depth interviews [107,109,132]; and the comparison of cases [21,118,120].

- Quantitative tools were used in fewer of the studies and basically with the support of models using structural equations [110,112,126,128,130,131,133].

- The monitoring of the standards in the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) to report on sustainability [20,25].

The internal facilitators of compliance with the SDGs [8] in tourism organisations that were featured in the analysed studies were related to the following:

- The characteristics of the tourism organisations via the ecological performance of hotel employees [89]; and the job-based CSR initiatives aimed at decreasing staff churn at hotels [132].

- The incorporation of innovations and the use of technology in the introduction of eco-innovative CSR in museums [133]; the generation of circular economy around CSR initiatives [22]; the integration of CSR into the thinking of circular economy [102]; the generation of innovation in hotels via their ethical management [134]; the study of neuronal activity to detect the emotions of travellers [103]; and the application of green marketing strategies as a way of improving the sustainability of hotels via the application of ‘marketing with a cause’ strategies, with sustainability being the cause [108].

Lastly, a single study [93] proposed the generation of partnerships to achieve the SDGs. However, this was not focused on alliances between the public and private sectors as indicated in the SLR of Palau-Pinyana et al. [8], but rather on those between private tourism companies and NGOs.

5. Discussion

5.1. Criticism Paradox

The fashion industry is another significant contributor to global greenhouse gas emissions, accounting for approximately 10% of the total. Its extensive supply chains and energy-intensive production processes underlie this substantial environmental impact. Notably, the sector’s energy consumption surpasses that of both aviation and maritime industries combined [135]. Moreover, livestock-based food systems contributed 21.35% and 20.74% to global CO2 emissions in 2020 and 2021, respectively [136], encompassing on-farm activities, land-use change, and other key processes [137].

Previous research in the literature consistently indicates that energy intensity is the most influential factor in reducing emissions, while industrial scale is positively correlated with carbon emissions [138]. Consequently, industrial structure is a critical determinant of energy consumption and CO2 emissions, and adjustments to this structure represent a significant lever for decarbonization [139]. In the tourism industry case, empirical results [140] have demonstrated that while tourist arrivals lead to an increase in CO2 emissions, the revenue generated from these arrivals contributes to their reduction.

Education is considered as a facilitator that is external to business and that can help to achieve the SDGs [8]. The results of this SLR have been able to prove that, amongst the studies selected herein [124], there is a difference in the way that education is understood, seeing as it is not restricted to only formal teaching in educational institutions. Rather, it can be expanded to include that which is taught in the working environments of tourism companies to both the employees and customers. Notwithstanding the above, culture in itself is a facilitator of sustainable development [141] and, therefore, a way to achieve the SDGs. Hence, in the relevant identified study [124], the proposal is to generate a culture of sustainability and responsible tourism in younger travellers.

In terms of the use tools as external facilitators of the SDGs, as also proposed by Palau-Pinyana et al. [8], there is a noted coherence in this SLR’s studies between the previous findings and the majority usage of qualitative methods focused on the analysis of cases or content, on in-depth interviews, and on case comparisons. The same coincidence occurs when monitoring standards for the sustainability report: the studies choose to use compliance with the content of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) as another external facilitator for achieving the SDGs, as also proposed by Palau-Pinyana et al. [8].

Notwithstanding the above, there does seem to be some distancing between the findings of the studies selected in this SLR and those generated by the one carried out by Palau-Pinyana et al. [8], especially when considering the application of quantitative statistical methods as tools for evaluating the implementation of the SDGs. The majority of this SLR’s studies make use of modelling via structural equations, while those in the study of Palau-Pinyana et al. [8] use logistical regression to predict behaviour.

The internal facilitators that are related to tourism companies’ commitment to achieving the SDGs and that were detected in this SLR’s studies in the form of CSR initiatives aimed at reducing employee churn by improving their jobs [132] or aimed at making the company greener [89], seem to be aligned with previous findings [8].

5.2. Implementing CSR: Barriers in Tourism Industry

While the effective integration of corporate social responsibility (CSR) policies into the tourism industry is increasingly recognised as a strategic and ethical imperative [142], it faces several intrinsic barriers that challenge full implementation. Understanding these obstacles, for which no universally accepted hierarchical list exists [143], is crucial for formulating strategies that enable tourism businesses to move from rhetoric to meaningful action in sustainability.

Factors that exclusively act as barriers include lack of time, guest behaviour, and inconveniences stemming from external collaboration. These also encompass financial challenges, the availability of resources, and the perspectives and imperatives of company owners and shareholders [144].

Guest behaviour (such as towel reuse, water conservation, and recycling promotion, among others) presents a notable impediment to sustainability implementation [145]. For instance, hotel guests may show a strong preference for environmentally friendly hotels, e.g., [146], but this attitude can change when inconveniences and discomfort arise during their stay due to sustainability practices. This could, in fact, ultimately undermine dedicated efforts and often prove challenging to modify, largely due to its inherent hedonic nature [145].

Similarly, collaborating with suppliers who are not committed to initiatives like reducing paper use can, for instance, complicate transactions. This often necessitates adopting practices that run counter to sustainability objectives, thereby hindering overall achievement efforts [145]. Forging partnerships with suppliers whose structures, strategies, and cultures align with a company’s own objectives and values presents a considerable challenge, thus necessitating an evolution from traditional transactional supplier management to one that incorporates long-term relationships grounded in sustainable principles [147].

However, as previously stated, another reported impediment is the scarcity of financial resources, given that intense competitive pressure often compels businesses to minimise expenses, particularly when competitors are not implementing CSR measures [148].

Initial investments in CSR practices, such as adopting renewable energy, improving infrastructure for water efficiency, or obtaining sustainable certifications, can often demand substantial capital outlay. Although Porter and Kramer [149] argue that strategic CSR can generate shared value and long-term benefits, many tourism businesses, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), operate on tighter margins and may lack the immediate financial capacity to bear these costs. This is evident, for example, in numerous small and independent hotels where managing environmental sustainability presents a particularly necessary challenge to maintain competitiveness against their larger counterparts [144].

Related to the aforementioned, the barrier of insufficient knowledge and technical expertise emerges. Many managers still do not implement the concept of CSR due to a lack of adequate information or an unclear understanding of how to put CSR policies into practice within their specific business context [150]. For instance, some hotel managers continue to lack sufficient awareness regarding the positive effects of CSR policies on their businesses. Enhancing their performance in this area could, therefore, improve relationships with employees, customers, local communities, and other stakeholders [151]. Indeed, it has been confirmed that employee know-how is contingent on their environmental knowledge and engagement in CSR policies [152].

Since implementing CSR policies extends beyond mere goodwill, necessitating a thorough understanding of sustainability principles, impact measurement methodologies, and the application of innovative technologies and practices, a lack of such knowledge could manifest as an inability to identify high-impact areas, consistently measure progress, or even credibly communicate efforts.

Well-structured procedures and the provision of suitable tools are critical for enhancing performance effectiveness. Conversely, their absence often leads to misunderstandings, errors, wasted time, and inconsistencies, thereby impeding both efficient task execution and the advancement of sustainability initiatives [144]. Moreover, disparate departmental priorities in sustainability practices, driven by specific functional roles, resulted in varied perceptions of relevance and alignment with broader CSR objectives. This underscores the need not only for clear procedures and adequate tools, but also for their bespoke adaptation to the diverse functions across different areas of the company [145].

In essence, implementing CSR policies in tourism is a multifaceted challenge that extends beyond mere corporate goodwill. Addressing these economic, knowledge-related, structural, regulatory, and market barriers is imperative for the tourism industry to truly fulfil its potential as a driver of sustainable development.

5.3. Profit–CSR Link: A Perennial Debate

Researchers have consistently investigated corporate social responsibility (CSR) for approximately four decades [153], with particular attention in financial economics and strategic management literature given to the relationship between CSR and corporate financial performance [154,155]. Despite extensive exploration, findings regarding this link remain inconclusive. Several factors may contribute to these mixed results, including idiosyncratic industrial characteristics [156], variations in how CSR and CFP are operationalised, methodological differences [157,158], the omission of relevant mediators or moderators [155,159], and differing theoretical perspectives.

The relationship between corporate profitability and CSR remains a subject of enduring debate in both academic and managerial discourse [157,159,160]. Historically, a common view suggested that investments in social or environmental initiatives inherently reduce a firm’s financial performance, framing CSR as a discretionary cost or an altruistic endeavour undertaken at the expense of maximizing shareholder wealth, thus diverting resources from core profit-generating activities and leading to diminished returns [161,162,163].

However, contemporary thought increasingly challenges this zero-sum assumption. A growing body of research and practical evidence suggests that robust CSR engagement can, in fact, align with and even enhance long-term financial viability, creating a shared value proposition [149,155]. Proponents of this view argue that strategic CSR initiatives can foster competitive advantages through various mechanisms. These include enhanced brand reputation and consumer loyalty, which may command premium pricing or expand market share [164,165]. Furthermore, a strong commitment to social and environmental stewardship can improve operational efficiencies (e.g., through waste reduction or energy conservation) [166,167], mitigate regulatory and reputational risks [168,169], and attract and retain high-calibre talent [170,171]. Moreover, it can stimulate innovation, leading to the development of new, sustainable products or services that open untapped markets [172,173].

Businesses, despite a somewhat limited perception of their social responsibilities, believe profitability and stakeholder respect are compatible. This is evidenced by firms strategically leveraging CSR for commercial gain and competitive advantage. Furthermore, CSR appears deeply integrated across business operations, viewed as a necessity rather than a luxury, which would suggest the existence of synergies with financial performance [174].

Studies show that tour operators deeply committed to CSR saw significantly greater short-term growth in both profits and sales. The findings also reveal that a positive and notable impact on these operators’ performance stems from applying CSR principles, promoting CSR values, and strengthening local economic connections [175]. Moreover, tour operators typically strive to balance the interests of local communities, employees, and their businesses when making investment decisions, also factoring in the impact on the local economy and environment. However, empirical evidence suggests that three specific variables—local government pressure, the scale of the investment, and the tour operator’s profile—moderate these investment preferences [176].

Although the idea of a strict trade-off is increasingly questioned, the exact nature and extent of the relationship between profit and CSR remain complex and multifaceted [177], influenced by sector-specific characteristics, the maturity and strategic integration of CSR within a firm’s operations, and the time horizon under consideration [178,179]; while short-term CSR investments might incur initial costs, their long-term strategic benefits—including enhanced brand equity, reduced operational risks, and improved stakeholder relations—often contribute positively to sustainable financial performance, making it crucial for firms to understand this intricate interplay to balance economic imperatives with broader societal obligations [180].

6. Conclusions

More research is needed to develop inclusive, competitive, and environmentally friendly business models [181]. This means, to the best understanding of the authors of this SLR, that previous research utilising this scientific methodology [3,8] and addressing the same topic has not clarified whether the implementation of CSR policies in the tourism industry contributes to achieving the SDGs within that industry, encompassing both those directly attainable as determined by the UN, and those achievable indirectly [11].

Madanaguli et al.’s [3] research highlights the promising study area involving CSR in tourism, yet it makes no reference to either the SDGs or their achievement through CSR practices. In the study conducted by Palau-Pinyana et al. [8], which examines the implementation of SDGs in the private sector, the word “tourism” is not even mentioned, unlike the term “SDG”, which appears 219 times. The last study that might have most closely resembled the one proposed in this article, authored by Hatipoglu et al. [23], is not an SLR and, furthermore, does not discuss SDGs for tourism in particular.

Consequently, and to the best understanding of these authors, it seems appropriate to conclude that this SLR is the first to systematically review tourism sustainability research focused on SDG-aligned CSR practices and initiatives.

This SLR is contributing to the academic literature and practical application by synthesizing current knowledge and identifying future research directions. This SLR found that over 94% of analysed studies used evaluation and monitoring methods for SDG-aligned CSR initiatives in tourism. Most evaluations were qualitative, focusing on case analysis and content analysis. Quantitative evaluations often used structural equation modelling to explain relationships between CSR practices and SDGs. This research highlights the need for further exploration of company-external facilitators for SDG achievement in the tourism industry [8]. While interest in sustainable tourism is growing, full adoption by the industry and visitors remains limited [50]. Despite recognizing the importance of CSR, some businesses hesitate to implement it due to concerns about increased costs and potential negative impacts on profits and competitiveness [47]. However, CSR is a long-term investment that benefits sustainable development. CSR practices can enhance hotel performance by improving service quality, employee motivation, and stakeholder relations [165]. Reducing paper consumption is identified as the primary CSR practice, closely followed by initiatives focused on employee well-being and minimising plastic usage [145].

However, the impact of CSR on SDG compliance in other tourism sectors, such as restaurants and travel agencies, remains largely unexplored. Lastly, and despite the evidence in this SLR showing the effects of CSR initiatives on the various SDGs, the existence of a risk of bias due to the impossibility of generalising the results obtained after analysing the included studies, given that they are focused on countries, geographic areas, or very specific sectors on the tourism industry, leads to the thinking that it would be advisable to carry out future research that covers a greater number of countries within the same sector of the industry.

6.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

At a theoretical level, conducting an SLR that examines the tourism industry’s sustainability with an explicit focus on CSR practices and initiatives aiming for SDG achievement fills a significant gap in the academic literature. This is because previous research on the relationship between tourism and SDGs, once synthesised as part of this SLR, has proven to be imprecise, merely offering general mentions without specifically detailing CSR’s contribution to their accomplishment.

Furthermore, adopting the SOR model as the main theoretical framework to understand how implementing socially responsible practices in tourism businesses can lead to the industry’s SDG achievement aligns with studying the complex interconnections among external factors, internal perceptions, and sustainable behaviours within the tourism industry.

One must also consider the persistent cost–investment duality when implementing CSR policies in the tourism industry, which is highly influenced by the short-term satisfaction of company shareholders. Finally, no company or state, based on the information extracted from the studies analysed in this SLR, has successfully implemented all of the SDGs proposed by the UN.

Here are some practical implications that can be proposed for the tourism industry, stemming from the research conducted:

- Utilisation of standard and global performance metrics and indicators, such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), or Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). These would enable tourism businesses to effectively measure and report their progress towards achieving the SDGs.

- Deployment of tools for energy consumption monitoring, like Energy Star Portfolio Manager or Schneider Electric Resource Advisor. These can be combined with other available tools for measuring corporate carbon footprints, such as Carbon Trust (https://www.carbontrust.com/en-eu, accessed on 20 June 2025) or Sphera Carbon Emissions Tracker (https://sphera.com/car, accessed on 20 June 2025).

- The imperative to enhance communication with customers, for example, to ensure that when they encounter measures promoting sustainability at their tourist destinations, they do not perceive them as impediments to their holiday enjoyment. In essence, this involves communicating the tourism industry’s efforts towards sustainability more credibly and transparently, thereby strengthening its reputation and attracting environmentally conscious customers.

- Fostering collaboration with supply chain providers to align respective supply chains with the targeted SDGs, which entails selecting local and ethically operating suppliers.

- Implementing education and awareness programmes for tourism industry employees, as understanding and internalising the concept of sustainability can facilitate the fulfilment of obligations arising from the implementation of CSR policies aimed at achieving the SDGs. Furthermore, this understanding would aid in communicating any potential inconveniences these policies might pose to tourists’ leisure and enjoyment at their respective destinations.

6.2. Challenges and Opportunities

Considering the preceding discussion, the pursuit of SDGs in the tourism industry through the implementation of CSR policies presents numerous challenges and opportunities.

Among many other challenges, the following could be cited: (1) the financing and resources required for their achievement [144,148], given that initial investment could be high, particularly for SMEs where profit margins are very tight due to the scale of their operations; (2) the knowledge and training of human resources within the tourism industry [150,151,152], who, by acquiring the necessary technical expertise and a better understanding of how to apply CSR in practice, could improve communication regarding inconveniences that customers might perceive in a company’s pursuit of SDGs; (3) the behaviour of guests [145] in particular, and tourists in general, since sustainable practices may be perceived as an inconvenience in tourist destinations; and (4) collaboration within the supply chain [145,147] in terms of aligning with tourism companies regarding sustainability.

Overcoming these challenges, or barriers depending on one’s perspective, could position tourism industry businesses as leaders in a more sustainable and profitable future, thereby presenting them with several opportunities. These include (i) improved operational efficiency, because of cost reduction derived from energy savings; (ii) enhanced reputation, enabling market differentiation and attracting consumers conscious of sustainable business practices; and (iii) improved relationships with their stakeholders, from strengthening ties with employees to fostering connections with local communities, customers, and others.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

All studies analysed in this SLR were written in English. This was despite no language restrictions being imposed during the searches conducted across the selected databases, and in accordance with items 6 and 25 of the PRISMA protocol [182]. Besides, the existence of automatic translation software renders this practice outdated [52].

Given that the studies retrieved from these searches were exclusively in English, it could constitute a language restriction, leading to language-based bias [183] and potentially overlooking instances where cultural context might be connected to the review question [184]. Nevertheless, retrospective analyses conducted by several authors [183] on studies that had excluded works in languages other than English generally showed a small effect.

Another significant limitation is that the studies analysed primarily focus on specific tourism industry activities, such as accommodation services or cruise travel. Given that this industry comprises a myriad of related activities, further research into the theoretical and practical implications within these other sectors of activity is anticipated.

Another significant limitation of this SLR is that the results are predominantly drawn from qualitative studies. In this regard, the limitations of the PICO conceptual framework for use with qualitative studies are well-known; for instance, concerning the comparison (C), which is not a typical component of a qualitative research question. Similarly, the intervention (I) and outcomes (O) might require prior manipulation to fit the qualitative paradigm [185].

Despite alternative frameworks to PICO, such as sample, phenomenon of interest, design, evaluation, research type (SPIDER), existing for searching and synthesising qualitative studies, Cooke et al. [185] indicate that while these methods generate fewer articles, thereby reducing review time, they also yield a lower proportion of relevant articles compared to using the PICO methodology. Consequently, this could introduce additional bias from study selection, leading to a loss of information.

Finally, while the PICO framework serves as a technique for formulating research questions, it does not guarantee that all questions developed with its aid will necessarily be robust [186].

Consequently, further research is needed to examine the achievement, or lack thereof, of SDGs across a wider variety of activities within the tourism industry’s value chain, beyond just hotels and accommodations. This should also investigate the effectiveness of CSR initiatives in fostering collaboration among multiple supply chain actors, such as between hotels and their food, energy, or laundry suppliers.

Furthermore, despite the voluntary nature of CSR measure implementation in the tourism industry, future research should focus efforts on evaluating its actual impact, rather than solely the intention. Such research, influenced by technological advancements, could explore the leverage effect that new technologies based on Artificial Intelligence, Big Data, or Blockchain have on implementing CSR policies in the tourism industry and measuring their impact on SDG achievement within it.

Finally, given the prevalence of qualitative studies, it would be desirable for future research to be not only quantitative but also mixed methods, which is fundamental for exploring the adaptation of alternative frameworks to PICO, such as SPIDER.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Han, H. Consumer Behavior and Environmental Sustainability in Tourism and Hospitality: A Review of Theories, Concepts, and Latest Research. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1021–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Yang, F. Do Motivations Contribute to Local Residents’ Engagement in pro-Environmental Behaviors? Resident-Destination Relationship and pro-Environmental Climate Perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 834–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madanaguli, A.T.; Srivastava, S.; Ferraris, A.; Dhir, A. Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability in the Tourism Sector: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Outlook. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 30, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nave, A.; do Paco, A.; Duarte, P. A Systematic Literature Review on Sustainability in the Wine Tourism Industry: Insights and Perspectives. Int. J. Wine 2021, 33, 457–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepelus, C.M. Destination Unknown? The Emergence of Corporate Social Responsibility for the Sustainable Development of Tourism. Ph.D. Thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Naciones Unidas Declaración Del Milenio. Resolución A/RES/55/2 la Asamblea General; General Assembly of the United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.Q.T.; Young, T.; Johnson, P.; Wearing, S. Conceptualising Networks in Sustainable Tourism Development. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 32, 100575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palau-Pinyana, E.; Llach, J.; Bagur-Femenías, L. Mapping Enablers for SDG Implementation in the Private Sector: A Systematic Literature Review and Research Agenda. Manag. Rev. Q. 2024, 74, 1559–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel, I.; Cuervo-Cazurra, A.; Park, J.; Antolín-López, R.; Husted, B.W. Implementing the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals in International Business. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2021, 52, 999–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated Guidance and Exemplars for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations World Tourism Organization [UNWTO]. Tourism & Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://tourism4sdgs.org/tourism-for-sdgs/tourism-and-sdgs/ (accessed on 26 May 2023).

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. The Basic Emotional Impact of Environments. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1974, 38, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, V.; Benedetto, C.; Loesch, M. The Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) Paradigm as a Guiding Principle in Environmental Psychology: Comparison of Its Usage in Consumer Behavior and Organizational Culture and Leadership Theory. J. Entrep. Bus. Dev. 2023, 3, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodworth, R.S. Psychology Revised Edition; Henry Holt and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov, I.P. Conditioned Reflexes: An Investigation of the Physiological Activity of the Cerebral Cortex; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Pandita, S.; Mishra, H.G.; Chib, S. Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Crises on Students through the Lens of Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) Model. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 120, 105783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hameed, I.; Zainab, B.; Akram, U.; Ying, W.J.; Chan Xing, C.; Khan, K. Decoding Willingness to Buy in Live-Streaming Retail: The Application of Stimulus Organism Response Model Using PLS-SEM and SEM-ANN. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 84, 104236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asyraff, M.A.; Hanafiah, M.H.; Aminuddin, N.; Mahdzar, M. Adoption of the Stimulus–Organism–Response (S-O-R) Model in Hospitality and Tourism Research: Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Directions. Asia-Pac. J. Innov. Hosp. Tour. 2023, 12, 19–48. [Google Scholar]

- Borkowska-Niszczota, M. Społeczna Odpowiedzialność Biznesu Turystycznego Na Rzecz Zrównoważonego Rozwoju Na Przykładzie Obiektów Hotelarskich. Ekon. Zarządzanie 2015, 7, 368–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Revila, R.; Martinez Moure, O. Chapter 8. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and the 2030 Agenda in the Framework of New Trends in Tourism and Hotel Companies’ Performance. In Strategies for Business Sustainability in a Collaborative Economy; Leon, R.-D., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 141–159. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Z.; Zabilski, A. What Is the Relationship between Quality of Working Life, Work–Life Balance and Quality of Life? Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2022, 14, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.J.; Egas, J.L. Do Social Corporate Responsibility Initiatives Help to Promote Circular Economic Activity and Quality of Work Life for Employees? Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2022, 14, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatipoglu, B.; Ertuna, B.; Salman, D. Corporate Social Responsibility in Tourism as a Tool for Sustainable Development. An Evaluation from a Community Perspective. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 2358–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations World Tourism Organization [UNWTO]; United Nations Development Programme [UNDP]. Tourism and the Sustainable Development Goals—Journey to 2030; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hamrouni, A.; Karaman, A.S.; Kuzey, C.; Uyar, A. Ethical Environment, Accountability, and Sustainability Reporting: What Is the Connection in the Hospitality and Tourism Industry? Tour. Econ. 2022, 29, 664–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Arnedo, E.; Valero-Matas, J.A.; Sánchez-Bayón, A. Spanish Tourist Sector Sustainability: Recovery Plan, Green Jobs and Wellbeing Opportunity. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Travel & Tourism Council [WTTC]. Travel & Tourism Economic Impact 2022. Global Trends August 2022; World Travel & Tourism Council [WTTC]: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- World Tourism Organization [UN Tourism]. World Tourism Barometer January 2025 (Excerpt); World Tourism Organization [UN Tourism]: Madrid, Spain, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- World Tourism Organization [UN Tourism]. World Tourism Barometer; World Tourism Organization [UN Tourism]: Madrid, Spain, 2025; Volume 23. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, R. Sustainable Tourism: Research and Reality. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 528–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Grosbois, D. Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting by the Global Hotel Industry: Commitment, Initiatives and Performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 896–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme [UNEP]. UNEP for Tourism. Available online: https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/resource-efficiency/what-we-do/responsible-industry/tourism (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- United Nations World Tourism Organization [UNWTO]. Transport-Related CO2 Emissions of the Tourism Sector. Modelling Results; World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2019; ISBN 978-92-844-1665-3. [Google Scholar]

- Rico, A.; Martínez-Blanco, J.; Montlleó, M.; Rodríguez, G.; Tavares, N.; Arias, A.; Oliver-Solà, J. Carbon Footprint of Tourism in Barcelona. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulsi, P.; Ji, Y. A Conceptual Approach to Green Human Resource Management and Corporate Environmental Responsibility in the Hospitality Industry. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, E.; Konttinen, A. Circular Economy in Tourism and Hospitality—A Nordic Perspective. In Towards Sustainable and Resilient Tourism Futures. Insights from the International Competence Network of Tourism Research and Education (ICNT); Köchling, A., Seeler, S., van der Merwe, P., Postma, A., Eds.; Schriftenreihe des Deutschen Instituts für Tourismusforschung; Erich Schmidt Verlag GmbH & Co.: Berlin, Germany, 2023; Volume 1, pp. 131–148. [Google Scholar]

- Khatter, A. Challenges and Solutions for Environmental Sustainability in the Hospitality Sector. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.; Pérez, A.; Rodríguez del Bosque, I. Measuring Corporate Social Responsibility in Tourism: Development and Validation of an Efficient Measurement Scale in the Hospitality Industry. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 365–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakami, V.; Bindu, V.T. A Study on Factors Influencing the Visitor Experience on Eco Tourism Activities at Parambikulam Tiger Reserve. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Syst. 2020, 43, 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Purwanda, E.; Achmad, W. Environmental Concerns in the Framework of General Sustainable Development and Tourism Sustainability. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2022, XIII, 1911–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korstanje, M.E.; George, B.P. Education as a Strategy to Tackle over Tourism for Overtourism and Inclusive Sustainability in the Twenty-First Century. In Overtourism: Causes, Implications and Solutions; Séraphin, H., Gladkikh, T., Vo Thanh, T., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 341–359. ISBN 9783030424589. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, N.; Kestwal, A.K. Principals, Practices, and Challenges of Social Sustainability in the Tourism and Hospitality Industry. In Managing Tourism and Hospitality Sectors for Sustainable Global Transformation; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyle, B.; Moyle, C.-L.; Ruhanen, L.; Weaver, D.; Hadinejad, A. Are We Really Progressing Sustainable Tourism Research? A Bibliometric Analysis. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 106–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribe, J. The Economics of Recreation, Leisure and Tourism, 5th ed.; Routledge Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Janjua, Z.u.A.; Krishnapillai, G.; Rahman, M. A Systematic Literature Review of Rural Homestays and Sustainability in Tourism. SAGE Open 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahlevan-Sharif, S.; Mura, P.; Wijesinghe, S.N.R. A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews in Tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 39, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.; Bu, N.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, K.; Ro, Y. Sustainability of Hotel, How Does Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility Influence Employees’ Behaviors? Sustainability 2019, 11, 7009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R.N.S.; Martins, A.; Solnet, D.; Baum, T. Sustaining Precarity: Critically Examining Tourism and Employment. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1008–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantis, D.; Puhr, R. Corporate Social Responsibility and Work-Life Balance Provisions for Employee Quality of Life in Hospitality and Tourism Settings. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2022, 14, 207–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wani, G.A.; Nagaraj, V.; Haseeb, M.; Sultan, S.; Hossain, M.E.; Kamal, M.; Shah, S.M.R. Progress in Sustainable Tourism Research: An Analysis of the Comprehensive Literature and Future Research Directions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinayavekhin, S.; Li, F.; Banerjee, A.; Caputo, A. The Academic Landscape of Sustainability in Management Literature: Towards a More Interdisciplinary Research Agenda. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2023, 32, 5748–5784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harari, M.B.; Parola, H.R.; Hartwell, C.J.; Riegelman, A. Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: A Review, Evaluation, and Recommendations. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 118, 103377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramer, W.M.; Rethlefsen, M.L.; Kleijnen, J.; Franco, O.H. Optimal Database Combinations for Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews: A Prospective Exploratory Study. Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabić, M.; Vlačić, B.; Kiessling, T.; Caputo, A.; Pellegrini, M. Serial Entrepreneurs: A Review of Literature and Guidance for Future Research. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2021, 61, 1107–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, N.; Naveed, S.; Zeshan, M.; Tahir, M.A. How to Conduct a Systematic Review: A Narrative Literature Review. Cureus 2016, 8, e864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; McAleenan, A.; Reeves, B.C.; Higgins, J.P. Assessing Risk of Bias in a Non-Randomized Study. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.3 (Updated February 2022); Higgins, J.P.T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., Welch, V.A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wohlin, C.; Kalinowski, M.; Romero Felizardo, K.; Mendes, E. Successful Combination of Database Search and Snowballing for Identification of Primary Studies in Systematic Literature Studies. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2022, 147, 106908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, C.; Glanville, J.; Briscoe, S.; Featherstone, R.; Littlewood, A.; Marshall, C.; Metzendorf, M.-I.; Noel-Storr, A.; Paynter, R.; Rader, T.; et al. Chapter 4: Searching for and Selecting Studies. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.3 (Updated February 2022); Higgins, J., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., Welch, V.A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mourão, E.; Pimentel, J.F.; Murta, L.; Kalinowski, M.; Mendes, E.; Wohlin, C. On the Performance of Hybrid Search Strategies for Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2020, 123, 106294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinde, S.; Spackman, E. Bidirectional Citation Searching to Completion: An Exploration of Literature Searching Methods. Pharmacoeconomics 2015, 33, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]