Abstract

The sustainable preservation of archeological heritage located in rural and coastal regions requires more than technical interventions; it necessitates the awareness and active participation of local communities. However, community involvement in heritage management in such areas remains limited. This study aims to analyze the levels of cultural heritage awareness, conservation tendencies, and tourism-related expectations among local residents and visitors in the Magarsus Archeological Area, located in the Karataş district on the eastern Mediterranean coast of Turkey. The study was conducted in three phases: a literature review, field observations, and a structured survey conducted between June and August 2022 with 510 participants (280 local residents and 230 domestic visitors from surrounding provinces). The data were analyzed using SPSS 25.0 through descriptive statistical methods, complemented by cross-tabulation and chi-square analysis to identify patterns across demographic variables. The survey results not only reflect general perceptions about heritage and tourism but also offer critical insights into how the rural and coastal character of the site shapes conservation attitudes and tourism behavior. The findings reveal nuanced perceptions, including strong symbolic appreciation for heritage and general openness to tourism, alongside concerns about cultural and environmental risks. While the local community prioritizes the potential for economic benefit, many participants also emphasized the importance of safeguarding local traditions, crafts, and culinary heritage. Nevertheless, concerns were expressed regarding the risks posed by uncontrolled tourism, including environmental degradation, erosion of cultural identity, and the commodification of heritage values. Based on these insights, the study introduces a governance approach built upon three interlinked pillars: community-based participation, environmental sustainability, and tourism practices aligned with cultural values. The proposed approach aims to support the inclusive and sustainable management of Magarsus and other rural and coastal archeological landscapes with similar characteristics.

1. Introduction

Beyond individual ownership, cultural heritage constitutes a cornerstone of collective identity by embodying the continuity of the past in the present. Its preservation extends beyond safeguarding tangible structures; it also encompasses the protection of cultural diversity, the reinforcement of local belonging, and the enhancement of societal well-being. However, speculative interventions driven by short-term economic incentives pose significant threats to the sustainability of heritage sites. Against this backdrop, the preservation of cultural heritage has emerged as a strategic imperative. As underscored in UNESCO’s heritage governance frameworks, community engagement is not only a right but a vital necessity in ensuring effective heritage management. In support of this, Gražulevičiūtė (2006) emphasizes the contribution of heritage to environmental, cultural, and economic sustainability, while Rypkema (2005) argues that heritage plays a pivotal role in shaping the multidimensional fabric of the future—not merely preserving the past [1,2].

In this study, archeological heritage is addressed as a subcomponent of broader cultural heritage frameworks. Archeological heritage sites situated in rural and coastal regions are increasingly vulnerable to a combination of natural and anthropogenic threats. Accelerating sea-level rise, coastal erosion, and extreme meteorological events—intensified by climate change—present substantial risks to the physical integrity of archeological heritage sites, particularly those in low-lying coastal zones [1,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Concurrently, human-induced pressures such as the expansion of agricultural frontiers, rural depopulation, unregulated tourism, and uncoordinated development further hinder cohesive conservation planning [9,10]. A case study conducted along the Safranbolu–Amasra corridor on Turkey’s western Black Sea coast demonstrated that conservation practices in rural and coastal heritage settings often lack coherence and fail to ensure local community participation, ultimately weakening spatial identity. The study further emphasized that rural abandonment undermines long-term sustainability, underscoring the necessity for community-driven, context-sensitive planning [11,12,13]. Similarly, Dawson’s (2013) work along the Scottish coastline highlighted the importance of integrating local perceptions and experiential knowledge into early detection systems, thereby contributing critical insights for prioritizing conservation responses [5]. Within this framework, the knowledge and observations of local communities play a vital role not only in responding to human-induced pressures but also in monitoring and responding to environmental threats.

Traditional, top-down approaches to cultural heritage conservation are increasingly giving way to more participatory and community-centered strategies. In this evolving paradigm, the experiential knowledge, observational insights, and spatial sense of belonging possessed by local communities play a vital role in shaping the effectiveness of preservation efforts [14,15]. Participatory heritage management not only seeks to protect the physical fabric of cultural assets but also aims to sustain the relational memory—defined as the embedded social meanings and shared narratives associated with heritage sites—and ensure cultural continuity [16,17,18,19,20]. The 1990 ICOMOS Charter for the Protection and Management of the Archeological Heritage underscores that public participation constitutes a foundational element of holistic conservation strategies, functioning alongside scientific and technical methodologies [21]. Smith’s (2006) concept of the Authorized Heritage Discourse critiques institutional narratives for marginalizing local perspectives, thereby calling for more inclusive and democratically shaped heritage practices [22]. In parallel, Chitty (2017) emphasizes that involving local actors in knowledge production is not only a matter of representational justice but also essential for enhancing the social legitimacy and long-term resilience of heritage policies [23]. Within this context, heritage conservation must be reinterpreted not merely as a technical act but as a socially negotiated process, where community engagement becomes indispensable for the renewal and preservation of spatial identity.

Archeological heritage sites are not only cultural assets requiring preservation but also hold the potential to function as sustainable tourism destinations [24]. However, this dual potential may lead to both physical degradation and the erosion of cultural meaning if not governed through carefully structured, participatory strategies. Therefore, the intersection of heritage conservation and tourism demands balanced, community-oriented frameworks grounded in sustainability principles. The ICOMOS International Cultural Tourism Charter (1999) stresses that heritage sustainability through tourism is achievable only when local community needs, the authenticity of cultural values, and preservation priorities are duly respected [25]. Similarly, UNESCO’s (2013) Agenda for Culture in Sustainable Development advocates for cultural heritage to be recognized as a pillar of development rather than merely a catalyst for economic growth [26]. Echoing this, Zerbe (2022) argues that cultural heritage should be understood as a dynamic component of contemporary life, and tourism policies should reinforce rather than undermine cultural continuity [9].

In Turkey, tourism initiatives targeting rural and coastal archeological heritages still predominantly pursue short-term economic gains, often sidelining preservation imperatives and inclusive stakeholder engagement. Yet, sustainable heritage governance calls for tourism models that harmonize conservation goals with local development, fortify cultural identity, and foster social inclusivity. In this light, analyzing how tourism influences local awareness and conservation motivation is essential for designing effective, enduring strategies.

Magarsus, located in the Karataş district of Adana Province on Turkey’s eastern Mediterranean coastline, stands as a notable case within this context. Historically known as “Magarsa” or “Magarsos”, the ancient city was a prominent harbor settlement in the region of Cilicia, coming under the control of various civilizations—from the Achaemenid Persians to the Ottoman [27]. During the Hellenistic and Roman periods, the city was referred to as “Antiochia ad Pyramum” and “Coloniae”, respectively. Owing to its proximity to the Ceyhan River, Magarsus emerged as a critical center for regional trade and religious activity [28]. The Temple of Athena Magarsia, dating back to the second century BCE, epitomizes the city’s cultural and religious significance [29,30]. In the Byzantine era, it functioned as a bishopric and retained importance under Arab and Armenian governance. During the medieval period, the city was referred to as “Karataş” or “Dört Direkli” [31,32].

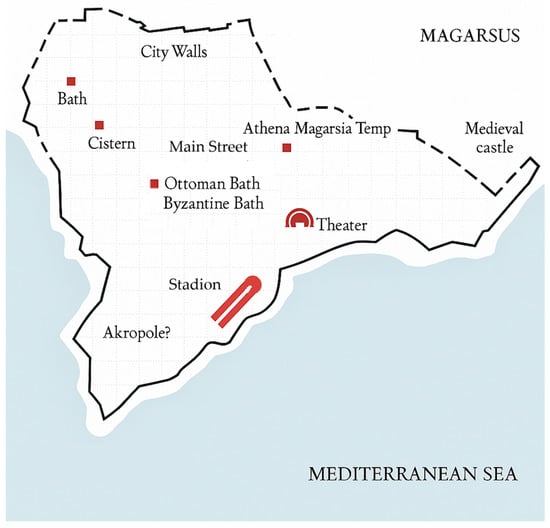

Originally constructed with a fortified grid plan, the site housed major architectural features such as a temple, theater, stadium, cisterns, Byzantine and Ottoman baths, and a medieval fortress [31] (Figure 1). However, many of these elements have been severely compromised due to environmental degradation and neglectful urban development [33]. While large-scale excavations remain limited, surface surveys have been ongoing since the 1890s. Notably, the Adana Archeological Museum conducted targeted excavations in the theater zone between 2013 and 2015 [34].

Figure 1.

Map depicting the boundaries and cultural assets of Magarsus, readapted from Ref. [34].

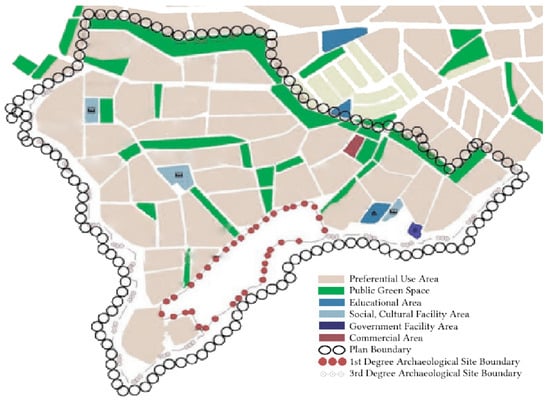

Currently, Magarsus is registered as a first- and third-degree archeological heritage site under Law No. 2863 on the Conservation of Cultural and Natural Assets [35]. Following its designation in 1988, land-use plans were revised in 2000 and 2013, introducing zoning restrictions and redefining the site’s official boundaries (Figure 2). Despite these regulations, the site continues to face significant challenges, including persistent construction pressure, coastal erosion, and tourism-driven development threats. As such, Magarsus not only serves as a historically significant urban settlement but also offers a critical example of the complex preservation challenges facing rural and coastal archeological heritages in contemporary heritage governance.

Figure 2.

Magarsus Archeological Site map. Spatial distribution and conservation zones of the Magarsus Heritage Site. Base map adapted from [34], modified by the author.

Despite the growing body of archeological research in Turkey, heritage policy and management frameworks remain predominantly focused on urban, monumental, and museum-based sites. Consequently, the intersecting vulnerabilities of rural/coastal archeological landscapes—where environmental, infrastructural, and social challenges converge—are largely overlooked in both academic and governance discourses. These landscapes often suffer from a lack of institutional support, seasonal population shifts, and exposure to both natural and anthropogenic risks. This underrepresentation frames the rationale for focusing on Magarsus, a site that exemplifies the tensions between potential and neglect in Turkey’s rural/coastal heritage fabric.

Framed by these intersecting challenges in rural/coastal heritage governance and community participation, the study addresses the following research questions:

What factors influence public awareness and perceptions of value regarding archeological heritage, and how do these shape participation in heritage conservation and tourism planning?

How do local communities perceive the impact of rural and coastal conditions on heritage values, governance participation, and sustainability potential?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Emerging Approaches to the Conservation of Rural and Coastal Archeological Heritages

In recent years, the conservation of rural and coastal archeological heritages has shifted away from conventional, intervention-focused approaches toward more integrated, multi-stakeholder strategies. These approaches increasingly emphasize disaster risk reduction, climate adaptation, community involvement, and the incorporation of local knowledge systems into heritage governance.

Dawson and colleagues, drawing on diverse geographical examples, argue that the resilience of coastal heritage sites under climate-related pressures depends on the integration of interdisciplinary strategies with the experiential insights of local communities. Their “middle ground” model proposes a framework that combines scientific methodologies with community-based observations to support both emergency responses andlong-term monitoring and adaptation [36,37,38].

Similarly, a study conducted by Mattei et al. (2020) on Naples’ Posillipo Hill emphasizes the importance of aligning archeological site management with coastal planning policies [39]. This integrated approach is seen as crucial not only for the sustainability of cultural heritage but also for the long-term resilience of coastal environments [39].

In the Canadian context, Sutter et al. (2023) reveal that rural communities are not merely passive observers in conservation processes but are also engaged as decision-makers and implementers. Such participatory models not only enhance cultural sustainability but also foster a deeper sense of local ownership and collective memory [16].

Consequently, conservation efforts in rural and coastal archeological heritages must extend beyond the protection of physical structures. They should also account for the embedded cultural value systems, social memory, and everyday local practices that define the identity and continuity of these heritage environments.

2.2. Heritage Awareness and Perceptions of Cultural Value

Heritage awareness refers to the level of consciousness through which individuals and communities recognize, assign meaning to, and seek to preserve cultural assets from the past. This awareness encompasses not only cognitive recognition but also emotional, historical, and identity-based attachments [40]. Smith (2006) asserts that cultural heritage is not limited to tangible objects; it also encompasses the symbolic and identity-based relationships that societies establish with their past [22]. Similarly, Graham et al. (2000) argue that heritage is “not the past itself, but a present-day representation of selected elements of the past”, emphasizing that the value of heritage is not objective but rather socially constructed [41]. This construction process is shaped by individual and collective memory, spatial experiences, and social interactions. Byrne (2008) contends that heritage should not be viewed solely as static objects for preservation but as active sites of social practice, encounter, and engagement [42]. This perspective reinforces the notion that cultural heritage not only reflects the past but also actively shapes present-day societal dynamics and informs future trajectories.

UNESCO’s 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage adopts a broad and inclusive definition of heritage—one that extends beyond physical monuments to include practices, representations, narratives, and knowledge systems. This framework views heritage awareness not merely as technical knowledge but as a form of cultural and social participation. Perceived value, within this framework, is shaped by socially embedded judgments about what constitutes heritage and why it matters [43].

Community-based models such as Japan’s “Living Heritage” approach exemplify how heritage awareness can be enhanced in rural areas through holistic strategies, including school-based education programs, intergenerational knowledge transfer, and volunteer participation [44]. These initiatives highlight that heritage awareness can evolve from mere recognition to active stewardship, intergenerational transmission, and collaborative protection.

In the Turkish context, particularly in rural and coastal areas, research suggests that cultural heritage awareness is often shaped by traditional values and practices. However, these local interpretations may not always align with institutional conservation policies [11,45,46]. This divergence underscores the influence of local knowledge systems, spatial memory, and everyday lived experiences on the meanings attributed to heritage.

In conclusion, the sustainable conservation of archeological heritage sites with rural and coastal character requires a nuanced understanding of the values and perceptions attributed to these sites. Such an approach calls for the cultivation of emotional, social, and participatory connections to heritage—going beyond physical interventions to foster deeper cultural engagement. These meaning-making processes also form the foundational basis for the participatory heritage governance models discussed in the following section.

2.3. Participatory Approaches in Community-Based Heritage Management

Ensuring the sustainable conservation of cultural heritage requires that community involvement be positioned not as a supplementary element, but as an integral and continuous component of decision-making, implementation, and monitoring processes. This is particularly critical in rural and coastal archeological sites, where traditionally centralized preservation policies have often yielded limited success. When the embedded knowledge, spatial memory, and everyday cultural practices of local communities are excluded from heritage management, spatial belonging and local ownership tend to erode [18].

Participatory heritage management frameworks advocate for the meaningful inclusion of communities not only in the implementation of conservation actions but also in the processes of decision-making, value articulation, and interpretation. Recent studies have illustrated how this approach is gaining traction in rural settings. For instance, Gocer et al. (2024) analyze how cultural tourism can enhance community resilience in rural Turkey, emphasizing that public participation is vital for both economic viability and cultural continuity [47]. In the absence of such involvement, not only are the tangible heritage assets jeopardized, but so too are local identity and social cohesion.

Timothy (2015, 2024) argues that cultural heritage tourism should not be regarded solely as an economic activity, but rather as a holistic conservation model in which local communities are actively involved in knowledge production [48,49] and the interpretation of heritage. This inclusive approach has also been supported by various scholars who emphasize the integrative role of communities in shaping the meaning and management of heritage resources [50,51,52,53,54,55,56].

Giliberto and Labadi (2021), examining cases across the MENA region, argue that including communities in all phases of heritage projects—from design and goal setting to implementation and evaluation—enhances not only the durability of interventions but also their social legitimacy and public accountability [57].

In archeological heritage sites such as Magarsus, where heritage is shaped by both rural and coastal dynamics, the recognition and integration of community narratives, practices, and perceptions are fundamental to strengthening the legitimacy and effectiveness of conservation policies. Participatory heritage governance should thus move beyond tokenistic consultation toward genuinely collaborative models. To achieve this, inclusive planning frameworks that incorporate local knowledge systems and culturally situated value perceptions must be established, ensuring that community representatives play substantive and empowered roles throughout all stages of heritage management.

2.4. Dynamics of Sustainable Tourism and Participatory Governance in Cultural Heritage Sites

The sustainable management of cultural heritage sites requires a holistic approach that extends beyond the preservation of physical structures to encompass social, economic, and governance dimensions. This is especially relevant for archeological sites located in rural and coastal regions, where the expansion of tourism intensifies interactions among diverse stakeholders. As such, governance models must be restructured to ensure broader inclusivity and adaptability. Sustainable tourism is not limited to driving economic growth; it simultaneously seeks to enhance local well-being, safeguard cultural continuity, and promote environmental responsibility. The ICOMOS International Cultural Tourism Charter (1999) emphasizes that tourism planning in heritage sites must align with the interests of local communities and support the preservation of cultural identity. Similarly, UNESCO’s Agenda for Culture in Sustainable Development (2013) advocates for cultural heritage to be recognized not only as a means of development but as a vital component of development itself [25,26].

Within this framework, participatory governance models have emerged as alternatives to state-centric conservation frameworks, promoting multi-actor and multi-scalar approaches to heritage management. Giliberto and Labadi (2021) argue that the active involvement of local communities in the design, decision-making, and evaluation phases—rather than limiting their role to the implementation stage—significantly enhances the effectiveness and legitimacy of conservation strategies [57]. This model also integrates the participation of experts, civil society actors, and private stakeholders, emphasizing the relevance of local knowledge systems, cultural priorities, and collective memory as guiding principles [45].

Therefore, sustainable heritage governance must be grounded not solely in technical interventions, but in inclusive, context-sensitive models that reflect the diverse perspectives and capacities of all stakeholders. The holistic framework proposed in the literature offers a strategic foundation for balancing preservation and development in heritage sites shaped by rural and coastal dynamics.

2.5. Gaps in the Literature and the Positioning of This Study

In the context of cultural heritage preservation, a notable gap exists in the development of multidimensional approaches that specifically address the unique needs of archeological heritage sites located in rural and coastal regions. In Turkey, most existing studies primarily focus on large-scale or urban heritage sites, while empirical and participation-based analyses concerning heritage areas embedded within local communities in rural and coastal settings remain limited [45].

Moreover, in the current literature, heritage awareness, levels of community engagement, and expectations from tourism are often treated as disconnected dimensions. However, in rural and coastal contexts, these three axes are intertwined and mutually influential. As Hatton and MacManamon (2000) emphasize, contemporary heritage management cannot rely solely on technical conservation; the integration of social values, representation, and local knowledge systems is a prerequisite for sustainability [58]. The lack of this holistic perspective often results in management models with limited practical impact.

The international literature similarly highlights these deficiencies. Mekonnen et al. (2022), based on their fieldwork in historical and religious sites in Ethiopia, identify the exclusion of local communities, lack of institutional coordination, and disregard for traditional knowledge systems as major challenges in the conservation process [59]. These findings closely parallel the structural difficulties encountered in archeological heritage sites like Magarsus, which possess both coastal and rural characteristics. Therefore, shaping sustainable preservation policies necessitates not only spatial or economic considerations but also a focused engagement with governance and social dimensions.

Against this backdrop, the present study of Magarsus offers a comprehensive approach aimed at addressing these multidimensional gaps in the literature. By simultaneously examining the interrelations between conservation, community participation, and tourism, this research contributes empirical insights into rural/coastal archeological sites—an underrepresented area in the Turkish heritage discourse. Supported by survey data, the fieldwork not only assesses the awareness and attitudes of local residents and visitors regarding cultural heritage but also proposes actionable implications for sustainable governance models and cultural tourism policies.

In this regard, the study offers four original contributions:

Theoretical contribution: the research conceptualizes the interrelated dimensions of heritage awareness, value perception, community participation, governance, and sustainable tourism within a cohesive analytical framework.

Methodological contribution: structured survey data provide a rare empirical basis for examining the management of archeological landscapes in rural and coastal contexts.

Empirical field contribution: a site-specific focus on Magarsus addresses the underrepresentation of rural/coastal archeological heritage cases in Turkey, delivering concrete evidence to inform more effective management practices.

Applied contribution: practical recommendations are formulated to promote community-based governance models, offering actionable guidance for local stakeholders and policymakers.

In conclusion, this research not only contributes to the sustainable preservation of Magarsus but also offers a transferable, data-driven, and holistic model that can inform the management of similar heritage contexts. Accordingly, it addresses key conceptual, methodological, and practical gaps in the literature.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

The empirical context of this study is the Magarsus Archeological Heritage Site, located in the Karataş district of Adana Province, along the southern Mediterranean coast of Turkey. The site provides a unique setting due to its multilayered historical background, natural coastal ecosystem, and contemporary conservation challenges. According to the official designation in 2001, 12 hectares of the area are classified as a first-degree archeological heritage site and 128 hectares as a third-degree site [60,61]. The defined site boundaries are as follows: to the north, 356th Street of İskele Neighborhood; to the east and west, agricultural lands; and to the south, Harbiş Beach. The site’s combined rural and coastal character offers a meaningful case for examining both physical conservation and community involvement (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Regional context of the Magarsus Site: Turkey, Adana Province, the Karataş district, and the surrounding coastal area.

Figure 4.

Aerial view of the excavated theater area within the Magarsus Archeological Heritage Site [62].

3.2. Research Design

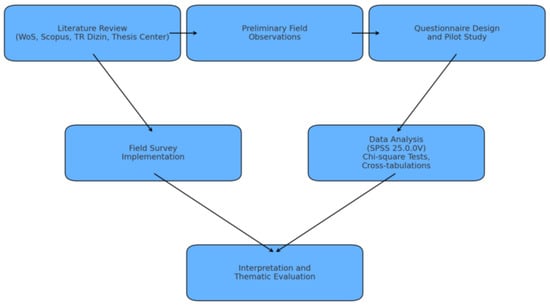

The study employed a quantitative research design within a descriptive analytical framework to explore relationships among community participation, cultural heritage awareness, and tourism within archeological heritage sites exhibiting both coastal and rural characteristics. Designed through a descriptive analytical framework, the research aims to comparatively assess the perceptions of both local residents and visitors. The study was carried out in three sequential phases:

- Step 1: An extensive literature review to establish the theoretical foundation and identify conceptual and empirical gaps in existing studies;

- Step 2: Direct field observations and on-site documentation to contextualize the physical and social characteristics of the Magarsus Archeological Site and to refine the survey content accordingly;

- Step 3: A structured in-person survey conducted with local residents and visitors to collect empirical data.

This phased approach was designed to identify general patterns and context-specific relational dynamics among the selected variables. It aimed to offer insights into the dynamics of a rural and coastal context that, despite growing visibility in academic discourse, remains underrepresented in the implementation of heritage management models (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Visual representation of the methodological design, illustrating the sequential and thematic structure of the research process.

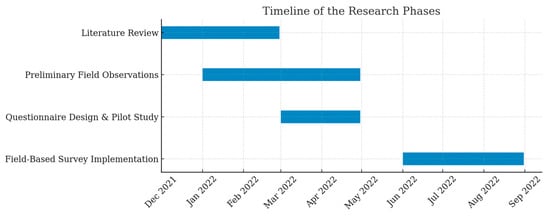

3.3. Data Collection Procedures and Chronological Framework

The data collection process began with a comprehensive literature review, preliminary site observations, and the development of a structured questionnaire conducted between December 2021 and April 2022. This phase was followed by field-based survey implementation at the Magarsus Archeological Site between June and August 2022 (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Timeline of the research phases conducted between December 2021 and August 2022, including a literature review, field observations, pilot study, and full-scale survey.

In the first phase, an extensive literature review was carried out to establish the theoretical framework of the study, focusing on conceptual domains such as cultural heritage management, community engagement, and sustainable tourism. Furthermore, historical documentation regarding the development, conservation status, and previous studies of Magarsus was analyzed to build contextual grounding.

In the second phase, direct field observations and photographic documentation were used to record the current condition of the site, the physical characteristics of cultural assets, existing conservation challenges, and the state of visitor-oriented infrastructure (Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10).

Figure 7.

The site’s entrence (on the left) and connection to the main road (on the right).

Figure 8.

View of the guard house, restroom units, and storage structures located within the entrance of site.

Figure 9.

Visitors engaging with informational signage at the site.

Figure 10.

General view of the theater and ongoing excavation area at the site.

The third phase comprised the main data-gathering activity: face-to-face survey interviews conducted with both local residents and visitors to the area. Participation was based on informed consent, and data were collected using a structured questionnaire format.

3.4. Questionnaire Design and Thematic Structure of Questions

The survey questionnaire used in this study was structured to address multidimensional themes such as heritage awareness, community participation, perceptions of tourism, and investment tendencies, with specific regard to the coastal and rural identity of the Magarsus Archeological Heritage Site. Comprising 22 questions, the instrument was designed in alignment with the study’s theoretical framework and field observations and was categorized under five main thematic sections. Participant responses enabled a comparative analysis of attitudes, perceptions, and expectations of both local residents and visitors regarding the site.

The questionnaire employed a layered inquiry structure, beginning with demographic information and progressing through definitions of cultural heritage, levels of civic engagement, tourism-related attitudes, and the perceived impacts of rural and coastal location. This design contributed to the contextual grounding of the study and supported the development of site-specific strategic recommendations.

Contact information was collected on a voluntary basis, and for validation purposes, background verification was conducted with a random subset of participants. The collected data were analyzed using SPSS 25.0.0V and interpreted through frequency and percentage distribution methods. Each thematic category is linked to corresponding sub-sections in the findings section, while a detailed classification of the survey is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Thematic structure of the questionnaire and analytical subsections.

3.5. Sampling and Data Analysis

The sample comprised adult residents of the Karataş district in Adana Province and domestic visitors to the Magarsus Archeological Heritage Site. A combination of simple random sampling and clustered sampling techniques was employed. In total, 510 individuals participated in the survey: 280 represented the local community of Karataş, while 230 were visitors from neighboring provinces, most of whom were day-trippers.

In line with the exploratory goals of the research, the data collection and analysis methods were chosen to reflect the contextual complexity of a rural and coastal heritage site. A structured questionnaire was used to gather perceptions across a demographically diverse sample (N = 510), and descriptive statistical techniques were applied to identify broad patterns without relying on assumption-based inferential models. This approach ensured clarity in interpreting responses related to heritage awareness, civic engagement, and tourism perceptions, while offering a methodologically grounded basis for policy development.

Despite efforts to ensure demographic diversity, the final sample was skewed toward male and middle-aged participants—a common limitation in rural field research. This demographic imbalance may have introduced a degree of sampling bias, particularly in terms of gender and age representation. Nevertheless, the dataset provided a sufficiently varied set of perspectives to enable a comparative analysis in line with the study’s objectives.

Data were analyzed using SPSS 25.0.0V. The analysis focused on thematic connections among heritage awareness, conservation attitudes, and tourism-related expectations. Descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages) were complemented by inferential methods such as cross-tabulations and chi-square tests to examine statistically significant relationships between selected socio-demographic variables and perception-based responses.

This analytical process allowed for the identification of coherent patterns linking individual characteristics to participation tendencies, thereby reinforcing the empirical validity of the study’s conceptual framework and informing its proposed governance approach.

4. Results

This section presents the results of the field survey conducted at the Magarsus Archeological Heritage Site. The results focus on participants’ demographic characteristics, levels of cultural heritage awareness, perspectives on conservation and tourism, and perceptions related to the site’s rural and coastal character. The results are structured in accordance with the study’s objectives and interpreted in relation to the relevant academic literature.

4.1. Demographic Profile

Awareness of cultural heritage is critically significant in revealing individuals’ levels of knowledge, attitudes, and sense of ownership regarding heritage values. Perceptions and experiences related to archeological heritage sites tend to vary depending on individuals’ demographic characteristics such as age, gender, education, occupation, and economic status [63]. In this study, the levels of awareness were analyzed among both local residents and visitors of the Magarsus Archeological Heritage Site, located in the Karataş district of Adana, Turkey.

Among the 510 respondents who participated in the survey, 65.1% identified as male and 34.9% as female. This distribution reflects a typical gender representation pattern observed in rural settings and may indicate a more prominent influence of male participants on heritage-related perceptions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic profile of respondents.

In terms of age distribution, the largest proportion of respondents (34.1%) falls within the 35–44 age group, followed by the 25–34 age group with 23.7%. The 18–24 age group represents only 8% of the sample. These results suggest that the research population is largely composed of middle-aged individuals with high potential for active community engagement (Table 2).

Regarding educational attainment, the majority of respondents are high school (36.9%) and middle school (29%) graduates. The proportion of university graduates remains relatively low, with 6.1% holding a four-year degree and 10.2% an associate degree (Table 2). This finding implies that awareness of cultural heritage in the region may be shaped more by everyday life experiences and traditional knowledge systems rather than formal education.

Based on the data concerning the occupation of the individual contributing most significantly to the household income, the distribution of professions among participants reveals a notable concentration in the private sector (37.3%) and among those engaged in trade, commerce, and craftsmanship (22.2%). Public sector employees (9.6%) and retirees (11.0%) also represent important segments contributing to household economies (Table 3). Additionally, participants include a diverse range of professional backgrounds such as doctors, lawyers, engineers, and other civil servants, further highlighting the socioeconomic variety within the sample.

Table 3.

Occupation of professions.

Household income levels further illuminate the socio-economic profile of the region. While 25.3% of participants reported a monthly income between TL 5001 and TL 6000, 26.3% indicated an income range of TL 6001 to TL 7000. These figures reveal that the study sample largely consists of individuals within the middle-income bracket, highlighting the possible influence of economic perceptions on attitudes toward cultural heritage (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Distribution of respondents by monthly income level.

4.2. Cultural Heritage Awareness and Perception of Value

Responses to the question “What do you think cultural heritage includes?” indicate that participants perceive heritage as a broad and multidimensional concept. While 32.5% of respondents identified monumental structures as part of cultural heritage, 26.9% mentioned local cuisine, 22.3% pointed to traditional houses, 13.5% referred to customs and traditions, and 4.8% emphasized handicrafts (Table 5). This distribution reveals that intangible cultural elements hold a strong place in collective memory alongside physical heritage assets.

Table 5.

Awareness and opinions on the preservation of cultural heritage in Magarsus.

When asked about responsibility for heritage conservation, 38.6% of participants identified the Ministry of Culture and Tourism as the primary authority, followed by 32.9% who named local municipalities, and 17.7% who pointed to local communities (Table 5). These findings suggest that centralized institutions continue to be perceived as dominant actors in conservation processes, although societal awareness and expectations for local engagement are evidently increasing.

In response to the question “Is public participation necessary?”, 47.5% answered yes, while 52.5% responded negatively (Table 5). This nearly equal distribution reflects the limited integration of the public into heritage governance and indicates that participatory conservation approaches have yet to be fully embraced or internalized by communities.

To further contextualize the descriptive findings, a cross-tabulation analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between participants’ educational attainment and their perceptions regarding institutional responsibility for cultural heritage preservation. The results revealed a statistically significant association (x2 = 11.078; p = 0.048), indicating that respondents with higher levels of formal education were more likely to identify local municipalities and community members as key actors in heritage conservation, as opposed to national-level authorities.

4.3. Participation Tendencies and Attitudes Toward Tourism

This section provides a detailed assessment of both local residents’ and visitors’ willingness to support heritage conservation processes and their attitudes toward tourism.

Respondents expressed predominantly positive views regarding the integration of conservation and tourism activities in the context of Magarsus. An overwhelming 92.5% supported the simultaneous implementation of preservation and tourism initiatives (Table 6). This high level of agreement indicates a strong awareness among the local population regarding cultural heritage and their acceptance of tourism as an integral component of the preservation process.

Table 6.

Perceptions of cultural heritage preservation and tourism development in Magarsus.

When asked about the potential impacts of tourism, economic expectations emerged as the primary concern. Specifically, 36.1% of respondents anticipated an economic revival in the region, while 28.4% hoped for an increased awareness of cultural heritage. Additionally, 19.4% expected a revitalization of local traditions, 11.2% foresaw improvements in infrastructure, and 4.1% expressed hopes for enhanced environmental conditions (Table 6). This distribution reveals that societal expectations related to heritage are shaped not only by economic considerations but also by cultural and environmental concerns.

Regarding the perceived positive impacts of tourism on cultural heritage, 24.2% of participants believed that tourism could help revive traditional crafts. This was followed by 22.5% who anticipated enhanced protective measures for the archeological site, 15.2% who expected environmental and urban improvements, and 6.4% who emphasized the preservation of local culinary heritage (Table 6). These responses suggest that tourism is viewed not merely as an economic driver, but also as a vehicle for reconstructing collective memory and reinforcing local identity.

Despite these favorable perceptions, only 38.6% of respondents indicated a willingness to actively support tourism in Magarsus. The remaining 61.4% expressed various reservations (Table 7). This discrepancy highlights a potential gap between theoretical support and practical engagement in community-based tourism initiatives.

Table 7.

Community attitudes and participation tendencies toward tourism in Karataş/Magarsus.

When asked about the specific forms of support they could offer, 27.6% of participants indicated a willingness to produce and sell handicrafts, while 26.7% were open to working in tourism facilities. Other proposed contributions included the marketing of agricultural products, providing homestay accommodation, and offering traditional meals (Table 7). This variety of responses reflects the multidimensional nature of potential local engagement. However, unlocking this potential requires the development of support mechanisms that enhance local capacities.

Only 8.2% of respondents reported having professional experience in the tourism sector, and 11.2% indicated that a family member had worked in the field. These figures suggest that while interest in tourism is high, practical knowledge and experience remain limited. Furthermore, 22.9% of participants expressed an intention to invest in tourism-related ventures, primarily in restaurant operations (43.7%) and accommodation services (24.9%) (Table 7). These preferences reveal that the local community perceives tourism potential predominantly within the realms of gastronomy and lodging.

4.4. Tourism Perception and Risks of Adverse Impacts

Although the promotion of tourism activities in cultural heritage sites presents economic, cultural, and social opportunities, it may also trigger reservations and perceived risks among local communities. In the case of the Magarsus Archeological Heritage Site, fieldwork revealed notable concerns and apprehensions regarding the potential negative consequences of tourism development.

Although the expansion of tourism activities in cultural heritage sites offers economic, cultural, and social opportunities, it can also raise concerns and risk perceptions among local communities. The fieldwork conducted at the Magarsus Archeological Heritage Site revealed a significant level of such concerns and negative perceptions.

Participants were asked to identify potential negative impacts of tourism in the region, and their responses were analyzed through a multiple-choice format. Among the respondents, 25.5% indicated that tourism could lead to environmental pollution. This was followed by concerns about the disruption of the urban fabric (17.5%), noise pollution (13.2%), erosion of natural areas (11.3%), increased traffic congestion (11.1%), inadequate infrastructure (10.9%), and other risks (10.4%) (Table 8).

Table 8.

Community perceptions of the adverse effects of tourism in Karataş/Magarsus.

The findings highlight a strong public awareness of environmental sensitivities and emphasize the perception that unsustainable tourism development may result in serious ecological and quality-of-life issues. In particular, participants drew attention to uncontrolled pollution, deteriorating infrastructure, and increasing density as key threats to local living conditions.

4.5. Rural and Coastal Context: Perceptions of Heritage and Tourism Tendencies

The Magarsus Archeological Heritage Site occupies a distinctive position due to its dual rural and coastal characteristics, setting it apart from many other cultural heritage sites across Turkey. This unique geographical and socio-cultural setting significantly shapes local perceptions regarding conservation, community involvement, and tourism potential. Accordingly, the final section of the survey included three specific questions aimed at capturing respondents’ evaluations related to this rural/coastal context.

In response to the question “Does the rural/coastal character of Magarsus contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage?”, 43.5% of participants stated that it facilitates preservation by offering a more natural setting. However, a notable 26.3% responded negatively (Table 9). This finding indicates that rural and coastal features do not always constitute a straightforward advantage for conservation; limitations in infrastructure, weak management systems, and inadequate interventions may negatively influence public perception.

Table 9.

Community perceptions on the role of rural/coastal characteristics in cultural heritage and tourism.

The role of local communities in the conservation of heritage sites was viewed more favorably, with a broader consensus. While 40% of respondents advocated for the active participation of local residents in decision-making processes, 34.1% considered voluntary support and information sharing to be sufficient (Table 9). These findings highlight a growing awareness of the importance of local capacity in community-based heritage governance and underline the value placed on involving the public in preservation efforts.

Responses to a multiple-choice question regarding the impact of Magarsus’s rural and coastal location on tourism also revealed considerable diversity. A total of 28.6% of participants viewed the site’s natural, authentic, and tranquil environment as an advantage. This was followed by 23.3% who emphasized the site’s openness to seasonal and day-trip tourism, and 18.4% who pointed to infrastructure deficiencies as a disadvantage. Additionally, 15.8% of respondents indicated that the rural identity of the site enriched the cultural experience (Table 9). These results demonstrate that the rural and coastal character of the site presents both attractive and fragile dimensions, suggesting the need for tourism planning strategies that address and balance this duality.

To further explore the internal consistency of community perspectives on participation, a cross-tabulation analysis was conducted between respondents’ belief in the necessity of public involvement and their preferred forms of civic engagement. While responses to the necessity of participation were nearly evenly split (47.5% yes, 52.5% no) (Table 5), the distribution of preferred participation modes revealed a consistent trend. Those who considered participation essential were significantly more likely to support active involvement in decision-making processes, while those who regarded it as unnecessary tended to prefer more passive engagement forms, such as being informed or offering limited support. This misalignment between abstract support for participation and concrete behavioral intent reflects a broader challenge in heritage governance: translating general public approval into sustained and meaningful engagement.

Building on these observations, and in order to examine how socio-demographic factors shape civic engagement, a cross-tabulation analysis was conducted between respondents’ gender and their preferred modes of involvement in cultural heritage governance. The analysis yielded a statistically significant association (χ2 = 9.314; p = 0.025), suggesting that gender differences influence how community members envision their role in heritage conservation. While female respondents more frequently favored direct involvement in decision-making processes, male respondents were more inclined to view participation as being informed or offering occasional voluntary support.

5. Discussion

This study examined the cultural heritage awareness, conservation tendencies, tourism perceptions, and views on the rural and coastal character of the Magarsus Archeological Heritage Site among both local residents and visitors. The findings were evaluated comparatively against national and international literature. While participants attributed generally positive meanings to cultural heritage, notable limitations were observed in the practical implementation of participation and perceptions of conservation responsibility.

Many participants associated cultural heritage not only with monumental structures but also with handicrafts, culinary traditions, and local customs. This reflects the development of locally constructed meanings that challenge the “Authorized Heritage Discourse” (Smith, 2006) [22]. Similarly, the work of Karataş et al. (2025) emphasizes the emotional and functional bonds rural communities maintain with their heritage [11,22], in alignment with the UNESCO (2003) Convention [43].

Although the theoretical importance of community participation is widely acknowledged, nearly half of the participants did not find public engagement essential. This highlights the gap between symbolic and actual participation, a trend consistent with studies in Africa and the MENA region [18,57].

Findings related to tourism perception show that while participants prioritize economic benefits, they also value cultural outcomes such as heritage promotion, revitalization of traditional crafts, and improvements to infrastructure. In this respect, the results align with studies by Gocer et al. (2024) and Timothy et al. (2024), supporting the view that heritage tourism contributes not only to local economies but also to building community resilience [47,49]. Despite a general openness to supporting tourism, participants’ lack of experience and hesitations about investment point to a deficit in systematic support and strategic guidance. Similar patterns have been identified in studies by Mekonnen et al. (2022) on Ethiopian heritage sites, Chinyele and Lwoga (2019) in the case of Kilwa Kisiwani in Tanzania, and Sutter et al. (2023) regarding community participation in rural areas of Europe [16,59,64]. These studies highlight that even when communities express positive attitudes toward heritage, they are often excluded from fully participating in decision-making and implementation processes.

Perceptions of Magarsus’s rural and coastal character also merit attention in this context. Nearly half of the respondents (45.1%) believe that these features help protect cultural heritage in a more natural setting. However, 22.4% pointed out that inadequate infrastructure and limited conservation capacity adversely affect this process. This indicates that while the natural environment of rural and coastal heritage sites may offer advantages, it can also increase vulnerability if not managed appropriately. Sutter et al. (2023), in their research on rural regions in Europe, similarly emphasize that sustainability in such contexts requires the strengthening of governance capacity to harness this dual potential effectively [16].

The study also explored how socio-demographic variables shape engagement preferences. Those who believed participation to be necessary were more likely to favor active roles in decision-making, while those who did not see it as essential preferred passive modes such as being informed or offering voluntary support. Gender was also found to be a significant factor in shaping engagement preferences (χ2 = 9.314; p = 0.025); women tended to adopt more active roles, while men favored more indirect forms. This finding resonates with existing literature emphasizing women’s heightened advocacy for participatory heritage governance [65,66].

Data on the extent of community contributions also underscore the importance of participatory approaches. While 39.8% of respondents indicated that local residents should actively engage in decision-making processes, 34.9% viewed voluntary support and the sharing of local knowledge as sufficient. These findings affirm Giliberto and Labadi’s (2021) assertion that communities must be involved not only as implementers but also as decision-makers [58]. This perception of participation reveals the need to move beyond symbolic inclusion and establish meaningful involvement practices in the Turkish context.

Perceptions regarding the impact of the site’s rural and coastal characteristics on tourism are equally noteworthy. While 25.7% of respondents viewed the site’s “tranquil, natural, and authentic environment” as advantageous for tourism, 15.5% perceived its underdeveloped infrastructure as a disadvantage. Participants also frequently cited other influencing factors, including seasonal patterns, the suitability for day-trip tourism, integration with local life, and the risk of natural disasters. This multidimensional understanding reflects the necessity for integrated strategies in heritage management—strategies that encompass not only conservation but also spatial planning, disaster risk management, and infrastructure development. These findings are consistent with the sustainable development principles outlined by Timothy and Nyaupane (2009) and UNESCO (2013) [26,67].

Recent academic work, particularly in rural heritage contexts, has highlighted the growing relevance of community-based approaches. Gocer et al. (2024) [47] emphasized the need for integrated tourism planning rooted in cultural continuity, while Timothy (2015, 2024) [48,49] evaluated heritage tourism as a co-creative process in which local communities contribute to heritage interpretation and policy. Giliberto and Labadi (2021), in their regional studies, demonstrated that participatory governance frameworks enhance social legitimacy and accountability [47,48,49,57]. These perspectives align with international frameworks such as UNESCO’s 2011 Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) and IUCN’s Nature–Culture Journey initiative. Both documents advocate for contextual, holistic, and community-driven approaches in heritage management. This cumulative body of work provides the conceptual grounding for the proposed three-pillar governance model, which is further elaborated in the conclusion [68,69].

In the case of Magarsus, the site’s rural and coastal character necessitates localized and adaptive governance strategies. The seasonal nature of tourism, infrastructural limitations, and site-specific environmental risks highlight the need for ecosystem-based conservation and participatory mechanisms that reflect Turkey’s rural and coastal heritage dynamics.

Building on the recent literature that emphasizes cultural continuity, participatory governance, and ecosystem-based heritage strategies—alongside the contextual findings of this study—the following section outlines a governance approach tailored to the specific socio-spatial dynamics of rural and coastal heritage areas such as Magarsus.

6. Conclusions

This research has examined the awareness levels, conservation tendencies, tourism perceptions, and participation attitudes of local communities regarding the cultural heritage of the Magarsus Archeological Heritage Site within the context of its rural and coastal character. The findings demonstrate that participants establish strong ties to cultural heritage not only through tangible structures but also through intangible elements such as handicrafts, traditional cuisine, and customs. This perspective reveals that heritage is perceived by the community not merely as an object of preservation, but as a lived and perpetuated cultural value.

A considerable portion of participants expressed a willingness to actively contribute to the protection of cultural heritage, emphasizing participation in decision-making, volunteerism, and the sharing of local knowledge. However, despite this willingness, actual participation remains limited in practice, with heritage policies largely governed by centralized mechanisms and insufficient levels of localization. This situation contradicts the goals of sustainable conservation and undermines the social representation of heritage.

It has also been observed that the rural and coastal setting of Magarsus presents both opportunities and vulnerabilities in terms of heritage management. While the site’s natural environment and cultural richness offer considerable tourism potential, infrastructural deficiencies, seasonality, and the risk of natural hazards constrain the sustainable use of this potential. Consequently, physical conservation strategies must be developed in conjunction with community participation mechanisms, supported by governance approaches that actively integrate local stakeholders into decision-making processes.

In this regard, the study proposes a framework structured around three interrelated pillars:

At the policy and planning level, governance approaches that are context-sensitive and specifically tailored to rural and coastal heritage landscapes should be developed. Local communities must be involved not only through informational mechanisms but also as active participants in decision-making processes. Tourism planning should prioritize low-intensity, high-quality approaches that respect local culture and address infrastructural needs.

At the educational and awareness level, cultural heritage awareness should be promoted through both school-based and lifelong learning programs, and traditional knowledge and practices of the local population should be made visible. Intangible cultural elements such as handicrafts and local cuisine should be documented and integrated with tourism in a sustainable manner.

At the institutional and managerial level, a multi-stakeholder, multi-layered, and inclusive governance structure should be adopted to foster horizontal communication and collaborative production among local authorities, civil society organizations, experts, and residents.

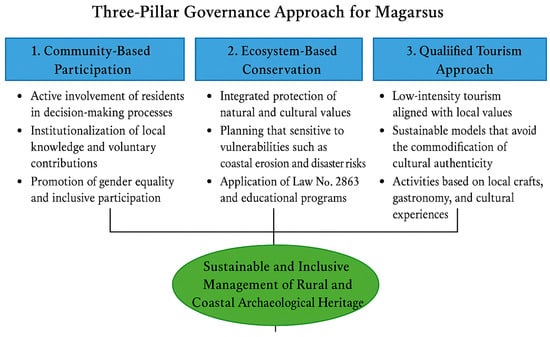

Grounded in both empirical findings and comparative insights from the literature, the proposed approach is structured around the following three pillars: Community-Based Participation, Ecosystem-Based Conservation, Qualified Tourism Approach (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Three-pillar governance approach for Magarsus.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that the management of archeological heritage sites with rural and coastal characteristics—exemplified by Magarsus—must be reimagined through participatory approaches grounded in social and ecosystem-based frameworks, rather than physical interventions alone. The proposed three-pillar governance approach, developed within this underexplored contextual framework, holds potential as a replicable and adaptable strategy for other regions with similar geographic and socio-cultural characteristics.

To support the practical realization of this approach in the Turkish context, several enabling mechanisms must be considered. Local authorities and heritage boards should be empowered through regulatory updates—particularly to Law No. 2863—to play a more proactive role in coordinating participatory initiatives. Additionally, multi-level collaboration between municipalities, civil society organizations, museums, and educational institutions will be vital for advancing public awareness, integrated planning, and ecosystem-based conservation. Finally, tailored capacity-building efforts in under-resourced rural and coastal regions will help translate the approach’s conceptual elements into actionable governance practices. The finding that female participants favored more active roles in heritage-related decision-making further highlights the importance of designing gender-sensitive participation strategies.

Taken together, these considerations affirm both the viability and adaptability of the proposed governance framework for sustainable heritage stewardship at the local scale. Moreover, the study contributes to the broader literature by offering a grounded understanding of how community perceptions and spatial contexts influence the design of participatory heritage governance approaches in rural and coastal settings.

Funding

This research was funded by Adana Alparslan Turkes Science and Technology University Individual Research Projects Unit (Project No: 21121001).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Adana Alparslan Turkes Science and Technology University (protocol code 17/1 and date of approval: 24 November 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ICOMOS | International Council on Monuments and Sites |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| IUCN | International Union for the Conservation of Nature |

References

- Gražulevičiūtė, I. Cultural heritage in the context of sustainable development. Environ. Res. Eng. Manag. 2006, 3, 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Rypkema, D. Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Economic and Social Development. Europa Nostra, 7 December 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P.; Thackray, D.; Wilson, E. Coastal heritage and climate change in England: Assessing threats and priorities. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2009, 11, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rick, T.C.; Fitzpatrick, S.M. Archaeology and coastal conservation. J. Coast. Conserv. 2012, 16, 135–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, T. Erosion and Coastal Archaeology: Evaluating the Threat and Prioritising Action. Ph.D. Thesis, University of St Andrews, St Andrews, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Castelle, B.; Dodet, G.; Masselink, G.; Scott, T. Increased winter-mean wave height, variability, and periodicity in the northeast Atlantic over 1949–2017. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2018, 45, 3586–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, N. Destructive events and the impact of climate change on Stone Age coastal archaeology in North West Europe: Past, present and future. J. Coast. Conserv. 2012, 16, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.G. Sea-level rise and archaeological site destruction: An example from the southeastern United States using DINAA. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zerbe, S. Global land-use development trends: Traditional cultural landscapes under threat. In Restoration of Multifunctional Cultural Landscapes: Merging Tradition and Innovation for a Sustainable Future; Zerbe, S., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 129–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawley, M.E. Desertification: Measuring population decline in rural Ireland. J. Rural Stud. 1994, 10, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karataş, E.; Özköse, A.; Heyik, M.A. Sustainable heritage planning for urban mass tourism and rural abandonment: An integrated approach to the Safranbolu–Amasra eco-cultural route. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güler, K.; Kâhya, Y. Developing an Approach for Conservation of Abandoned Rural Settlements in Turkey. A/Z ITU J. Fac. Archit. 2019, 16, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekici, S.C.; Özçakır, Ö.; Bilgin Altinöz, A.G. Sustainability of Historic Rural Settlements Based on Participatory Conservation Approach: Kemer Village in Turkey. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 14, 497–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Aziz, N.A.; Mohd Ariffin, N.F.; Ismail, N.A.; Alias, A. Community Participation in the Importance of Living Heritage Conservation and Its Relationships with the Community-Based Education Model towards Creating a Sustainable Community in Melaka UNESCO World Heritage Site. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.N.; Ariffin, N.F.M.; Ismail, N.A.; Alias, A. A Participatory Approach Towards Sustainable Heritage Management. J. Herit. Manag. 2024, 9, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutter, G.C.; O’Malley, L.; Sperlich, T. Rural Community Engagement for Heritage Conservation and Adaptive Renewal. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X. Participatory Management for Cultural Heritage: Social Media and Chinese Urban Landscape; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342867998 (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Chirikure, S.; Pwiti, G. Community Involvement in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage Management: An Assessment from Case Studies in Southern Africa and Elsewhere. Curr. Anthropol. 2008, 49, 467–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadizadeh, N.A.; Doğan, E. Community engagement and sustainable heritage tourism: Mediating role of archaeological heritage interpretation. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2024, 26, 175–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, E.; Kan, M.H. Bringing heritage sites to life for visitors: Towards a conceptual framework for immersive experience. Adv. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 8, 76–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. Charter for the Protection and Management of the Archaeological Heritage. International Council on Monuments and Sites; ICOMOS: Charenton-le-Pont, France, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L. Uses of Heritage; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitty, G. Heritage, Conservation and Communities: Engagement, Participation and Capacity Building; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çardak, F.S.; Salmeri, G. Misis antik kenti için kültürpark tasarım modeli önerisi. Türk Arkeol. Ve Etnogr. Dergisi 2023, 86, 151–169. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. International Cultural Tourism Charter; ICOMOS: Charenton-le-Pont, France, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Cultural Heritage for Sustainable Development Agenda. UNESCO, 2013. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/activities/727 (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Altay, M.H. Adım Adım Çukurova; Çukurova Turizm Derneği Yay: Adana, Turkey, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Bossert, T.H. Brief report on archaeological research in Karataş. Belleten 1950, 4, 661–666. [Google Scholar]

- Ener, K. Tarih Boyunca Adana Ovasına Bir Bakış; Berksoy Matbaası: Istanbul, Turkey, 1986; pp. 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Durgun Şahin, Y.; Altunkasa, M.F. Magarsos antik kenti oluşum kurgusunun analizinde sistematik bir yaklaşım. Avrupa Bilim. Ve Teknol. Derg. 2020, 18, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alishan, G.M. Sissouan or The Armeno-Cilicia: Geographical and Historical Description; The Auspices: Venice, Italy, 1899. [Google Scholar]

- Çoksolmaz, E. Guidance in ancient stadiums of Anatolia. Amisos 2022, 7, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beşaltı, K. Coastal Research in Magarsus Ancient City. Master’s Thesis, Department of Archaeology, Selçuk University, , Konya, Turkey, 2017; pp. 35–36. [Google Scholar]

- Erhan, F.; Gülşen, F.F. Excavation in Magarsus 2013–2015. 37th AAS 2015, 2, 175–190. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Türkiye. Law on the Conservation of Cultural and Natural Heritage No: 2863. 1983. Available online: https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/mevzuat?MevzuatNo=2863&MevzuatTur=1&MevzuatTertip=5 (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Harvey, D.; Perry, J. (Eds.) The Future of Heritage as Climates Change: Loss, Adaptation and Creativity; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrard, C. Challenged by an archaeologically educated public in Wales. In Public Archaeology and Climate Change; Dawson, T., Nimura, C., López-Romero, E., Daire, M.Y., Eds.; Oxbow: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, T.; Kelley, A.R.; Day, J.C.; Gray, C. Coastal heritage, global climate change, public engagement, and citizen science. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 8280–8286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattei, G.; Rizzo, A.; Anfuso, G.; Aucelli, P. Enhancing the protection of archaeological sites as an integrated coastal management strategy: The case of the Posillipo Hill (Naples, Italy). Rend. Fis. Acc. Lincei 2020, 31, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterton, E.; Watson, S. Framing Theory: Towards a Critical Imagination in Heritage Studies. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2013, 19, 546–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, B.; Ashworth, G.; Tunbridge, J. A Geography of Heritage, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D. Heritage conservation as social action. In The Heritage Reader; Fairclough, G., Harrison, R., Jameson, J.H., Schofield, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 149–173. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. 2003. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- UNESCO. ASPnet Conference. 2017. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/japan-holds-eighth-national-unesco-aspnet-conference (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Soykök Ede, B.; Taş, M.; Taş, N. Sustainable management of rural architectural heritage through rural tourism: İznik (Turkey) case study. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özgeriş, M.; Demircan, N.; Karahan, A.; Gökçe, O.; Karahan, F.; Sezen, I.; Akpınar Külekçi, E. Cultural heritage management in the context of sustainable tourism: The case of Öşkvank Monastery (Uzundere, Erzurum). Sustainability 2024, 16, 9964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gocer, Ö.; Boyacıoğlu, D.; Eröz Karahan, E.; Shrestha, P. Cultural tourism and rural community resilience: A framework and its application. J. Rural Stud. 2024, 107, 103238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J. Cultural heritage, tourism and socio-economic development. In Tourism and Development: Concepts and Issues, 2nd ed.; Sharpley, R., Telfer, D.J., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2015; pp. 237–249. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D.J.; Erdoğan, H.A.; Samuels, J. Archaeological heritage and tourism: The archaeotourism intersection. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2024, 26, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, D.H. Heritage, tourism, and the commodification of religion. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2003, 28, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, R. Dark tourism, thanatourism, and dissonance in heritage tourism management: New directions in contemporary tourism research. J. Herit. Tour. 2014, 9, 166–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, J. After wheat: Revitalizing Sicilian agriculture through heritage tourism. Cult. Agric. Food Environ. 2017, 39, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J. Cultural Heritage and Tourism: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitford, M.; Ruhanen, L. (Eds.) Indigenous Heritage; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Andreu, M. A History of Archaeological Tourism: Pursuing Leisure and Knowledge from the Eighteenth Century to World War II; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Timothy, D.J.; Wang, Y.; Min, Q.; Su, Y. Reflections on Agricultural Heritage Systems and Tourism in China. J. China Tour. Res. 2018, 15, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giliberto, F.; Labadi, S. Harnessing cultural heritage for sustainable development: An analysis of three internationally funded projects in MENA countries. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2021, 28, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatton, A.; MacManamon, F.P. (Eds.) Cultural Resource Management in Contemporary Society: Perspectives on Managing and Presenting the Past; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, H.; Bires, Z.; Berhanu, K. Practices and challenges of cultural heritage conservation in historical and religious heritage sites: Evidence from North Shoa Zone, Amhara, Ethiopia. Herit. Sci. 2022, 10, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikmen, Ç.; Toruk, F. Recommendations for the Preservation of Monumental Structures in Magarsus Ancient City. Soc. Sci. Stud. 2017, 5, 41–64. [Google Scholar]

- Yüksel, E.; Yüksel, A. Adana ili Karataş ilçesi Dört Direkli Mevkii, Magarsus antik kenti-I. ve III. Derece Arkeolojik Sit Alanları Koruma Amaçlı Imar Planı Revizyonu Ve Kentsel Tasarım Projesi Araştırma Raporları; Karataş Municipality Financial Services Directorate: Adana, Turkey, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- ANB Mimarlık. Available online: https://anbmimarlik.com/proje/magarsus-antik-tiyatrosu/#gallery-2 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Moshenska, G. Key Concepts in Public Archaeology; University College London Press: London, UK, 2017; pp. 74–75. [Google Scholar]

- Chinyele, B.J.; Lwoga, N.B. Participation in decision making regarding the conservation of heritage resources and conservation attitudes in Kilwa Kisiwani, Tanzania. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 9, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnani, S.T.; Yolanda, Y. Women and cultural heritage: Traces of guardians and heirs. AIP Conf. Proc. 2024, 3148, 030029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surti, T.; Pratomo, D.S.; Santoso, D.B.; Pangestuty, F.W. Unlocking the Economic Potential of Cultural Heritage: Women’s Empowerment in the Creative Economy of Developing Countries. J. Ecohumanism 2024, 3, 1794–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J.; Nyaupane, G.P. Cultural Heritage and Tourism in the Developing World: A Regional Perspective; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2011; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/activities/638/ (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- IUCN. Culture-Nature Journey: Exploring the Links with World Heritage; International Union for Conservation of Nature and International Council on Monuments and Sites: Gland, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://www.iucn.org/theme/world-heritage/our-work/culture-nature (accessed on 28 May 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).