Abstract

As social media platforms become integral to information dissemination, they play a crucial role in shaping tourist decision-making and travel behavior. However, while previous studies have examined the general influence of social media on tourism, limited research has explored the interplay between source attributes, content quality, destination image, and trust in fostering impulsive travel intentions, a key yet underexplored aspect of tourist behavior. To address this gap, this study integrates the Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) theory and the Information Adoption Model (IAM) to analyze how source credibility, source homophily, and content quality on social media influence impulsive travel intentions through destination image and trust. Using structural equation modeling (SEM) on survey data from 419 Chinese respondents, the results reveal that source credibility and homophily significantly enhance content quality, while both credibility and content quality positively shape destination image. Moreover, destination image and trust serve as crucial mediators, strengthening the relationship between social media attributes and impulsive travel behavior. This study advances the discourse on sustainable tourism development by shedding light on the role of digital engagement in shaping tourists’ spontaneous travel decisions, a dimension often overlooked in discussions on long-term economic sustainability. Furthermore, by examining the nuanced mechanisms of social media influence, this research provides practical implications for tourism marketers and policymakers aiming to leverage digital platforms for sustainable destination marketing.

1. Introduction

The advancement of Web 2.0 technologies has greatly reshaped information dissemination, with social media platforms offering users a virtual space for creativity and sharing. These platforms have become key channels for news, entertainment, e-payment, shopping, and social interaction [1,2]. By 2024, more than 5 billion people worldwide are active on social media [3], including platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, Tik Tok, and Xiaohongshu. Visual content on these platforms, comprising images and short videos, has revolutionized how individuals curate their self-presentation within social networks and has provided businesses with new channels to understand consumer preferences and promote their products and services [4]. Social media have emerged as primary conduits for travelers seeking destination information and sharing their experiences, significantly shaping the decision-making processes of potential tourists [5,6]. Previously, tourists mainly relied on traditional advertising and word of mouth to obtain travel information, with the limitations of these sources making it difficult to fully establish trust and a comprehensive image of destinations. Today, the online sharing and interactions on social media have increased the visibility of destinations’ tourism offerings, providing prospective travelers with authentic and credible insights [7]. As consumer demand evolves, traffic intensifies, and market competition increases, the role of social media in generating feedback and engaging customers has drawn substantial attention, establishing these platforms as essential tools for tourism marketers implementing targeted strategies [8].

Impulsive travel intention is typically triggered by external stimuli, signifying a spontaneous and unplanned desire to travel [9]. Unlike rational decision-making processes, impulsive actions are predominantly influenced by emotional factors. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced among Millennials and Generation Z, with social media initiating travel plans for 50% of individuals in these age groups [3]. Their travel plans are often inspired by the vivid and appealing content found on social media platforms [10,11]. Not only that, in China, the scale of monthly active users of mainstream social media platforms in 2024 is significant, of which WeChat (1.385 billion), TikTok (985 million) and RedNote (339 million) have become indispensable platforms for users to obtain information and share tips in their daily work, life and tourism scenarios. It is worth noting that RedNote and TikTok took lifestyle content (especially tourism) as their core positioning in their initial development stage, effectively stimulating users’ impulse consumption or travel will through attractive visual content such as images of food or short videos of scenic trips. While impulsive consumer behavior has been extensively studied in other sectors, research on impulsive travel remains sparse. To date, only a few studies have investigated the impact of shared tourism experiences [12], content types [13], and social media types [14] on tourists’ impulsive travel intentions.

In the field of tourism, source credibility, source homophily, and content quality are intimately linked to the construction of a destination’s image and trust. Users typically trust travel content from credible sources, which bolsters their positive impressions of the destination [15]. Moreover, individuals are more likely to trust content produced by others who share similar backgrounds, interests, or lifestyles. Such homogeneity enhances the perceived reliability of the information and strengthens the audience’s sense of connection, thus increasing trust and affinity toward the destination [16]. High-quality travel content serves the dual purpose of arousing potential tourists’ interest in a destination while also enhancing trust and image through its compelling appeal [11]. However, a comprehensive analysis of the complex relationships between source attributes, content quality, destination image, destination trust, and their influence on impulsive travel intention remains an underexplored area in research.

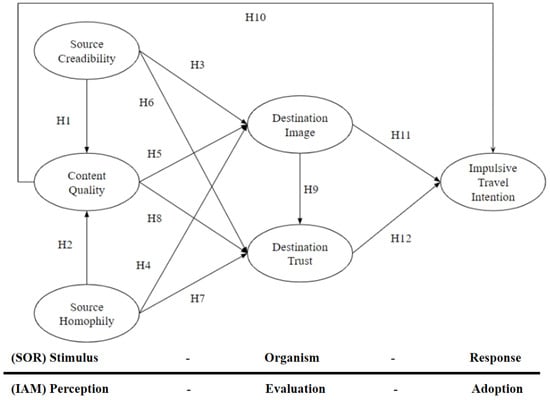

The Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) theory and the Information Adoption Model (IAM) are pivotal theoretical frameworks in the fields of environmental psychology and information science. The SOR theory is extensively applied to examine how external information, such as the physical environment and multisensory tourism experiences, impacts tourists’ emotional responses and behaviors [17]. The IAM primarily explains how the source, quality, and credibility of information, along with its alignment with consumer needs, influence consumer decision-making [18]. Consequently, this study integrates the SOR theory and IAM to develop a comprehensive model, wherein source credibility, source homophily, and content quality act as stimuli; destination image and destination trust function as the organism; and impulsive travel intention is the response. From the perspective of source attributes, this study seeks to identify the factors that trigger impulsive travel intentions among potential tourists. Compared to existing research, the innovation of this study lies in several aspects. First, this is the inaugural study to merge the SOR theory and IAM within the context of social media, providing a theoretical framework for future research. Second, this study examines how source attributes influence impulsive travel intentions through a multilayered pathway of content quality, destination image, and trust, addressing the gaps in previous research that has treated these factors in isolation. The research objectives of this study are dual: (1) we theoretically advance the integration of the Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) framework and Information Adoption Model (IAM) within the contexts of social media; (2) the findings provide tourism marketers with practical guidance, assisting them in refining social media content strategies and source selection to develop more compelling travel content that resonates with target tourists.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) Theory and Information Adoption Model (IAM)

The Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) theory, originally proposed by Mehrabian and Russell [19], posits that environmental stimuli influence and modify an individual’s internal or organismic state, which subsequently provokes approach or avoidance behaviors. In the tourism literature, the SOR framework has been extensively employed to interpret tourists’ emotional responses to environmental stimuli and their resultant behavioral intentions. Bitner [20] argued that the physical layout, landscape design, and quality of service facilities at a tourist destination significantly influence tourists’ emotions and overall experiences. Within social media, informational stimuli in virtual environments have also become important factors influencing tourists’ decision-making [21]. Tourists develop emotional bonds with destinations through stimuli such as social media images, videos, and reviews, which are crucial in shaping their travel decisions. Pahrudin et al. [22] indicated that social media posts and online reviews act as significant stimuli affecting tourists’ cognition, emotions, and behavioral intentions. The credibility, popularity, and relevance of online content are critical elements that influence tourists’ perceptions and subsequent travel decisions. When tourists actively or passively search and engage with content on social media, the quality of the content, source credibility, and information consistency serve as broad environmental stimuli (stimulus). This engagement may lead tourists to develop perceptions of a destination’s image or build trust in it, altering their organismic state (organism). These internal changes ultimately trigger impulsive travel behaviors or intentions (response).

The Information Adoption Model is a key theory in consumer behavior studies, primarily focusing on the transfer of knowledge. It encompasses three core processes—perception, evaluation, and adoption—assessing the usefulness and adoption of information through the lens of source and content quality [23,24]. This theory provides an important framework for understanding how consumers evaluate and adopt tourism-related information. In today’s environment on social media, travelers are inundated with vast amounts of information and evaluate its usefulness based on factors such as quality, source credibility, and source homophily [18]. The impact of user-generated content on tourism decision-making has increased significantly, with tourists often relying on online reviews and the shared experiences of others to assess the reliability and authenticity of information prior to making decisions. This user-generated content not only shapes the brand image of destinations but also helps tourists make better decisions that align with their needs and values [25].

2.2. Source Credibility

Source credibility, as initially proposed by Hovland et al. [26] in communication studies, underscores the significance of source characteristics in information dissemination. It refers to the consumer’s perception of the source’s reliability, impartiality, and honesty, serving as a crucial metric for assessing the information’s usefulness, particularly in terms of the provider’s perceived trustworthiness and expertise [27]. In tourism, Baker and Crompton [28] conducted research on travel agencies, finding that travel brochures endorsed by reputable institutions are more likely to influence tourists’ destination choices. In the context of social media, tourists now tend to trust user-generated content and influencer recommendations more than traditional travel brochures. Social media-based travel influencers, through their authentic and personalized travel experiences, have emerged as a powerful influence on tourists’ decisions [29]. The expertise, authenticity, and transparency demonstrated by these content creators not only enhance the perceived credibility of the information but also play a critical role in shaping destination branding and influencing tourist behavior [11,16].

2.3. Source Homophily

Source homophily refers to the connection between individuals who share similar interests, backgrounds, or values and plays a key role in the dissemination and acceptance of tourism information. Social comparison theory suggests that people assume that individuals similar to themselves share the same needs and abilities [30], making them more inclined to form connections and emotional bonds [31]. For online users, homophily can be inferred through information, profiles, and content shared by the information provider or commenters, even without face-to-face interaction. When consumers perceive that information providers have similar consumption habits, lifestyles, or cultural backgrounds, they are more likely to trust the information and rely on it for purchasing decisions [32]. Furthermore, within decentralized social media platforms, homophily allows users to efficiently filter information, increasing its perceived credibility and effectiveness, thus making it a vital tool in tourism marketing [11].

2.4. Content Quality

Content quality plays a key role in influencing consumer decisions. Numerous studies have underscored the importance of content quality, noting its significant impact on perceived trust in social media platforms [33], continuance intention [34], and destination image [35]. In tourism, high-quality user-generated content vividly showcases the destination’s landscape through text, images, and videos, directly influencing potential tourists’ impulsive travel decisions [12]. The perceived credibility and quality of information are further enhanced when such content is produced by creators who share similar interests and backgrounds with consumers [36]. Furthermore, a vlogger’s influence is shaped by both the quality of their content and the degree of homophily they share with their audience. Vloggers who share similarities in lifestyle and values with their audience exert a much stronger influence on purchase intentions [33]. Hence, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1.

Source credibility has a positive effect on content quality.

H2.

Source homophily has a positive effect on content quality.

2.5. Destination Image

Destination image is a subjective concept composed of cognitive, affective, and conative dimensions [37], typically defined as tourists’ beliefs, ideas, and impressions of a place [38]. Cognitive image refers to the mental representation tourists create by evaluating a destination’s features and offerings based on their own knowledge [39,40]. Affective dimensions involve emotional responses and feelings evoked by a destination, such as excitement or relaxation [41]. Lastly, conative image pertains to action elements and preferences towards visiting or recommending a destination [42] and is shaped by cognitive and affective evaluations [43]. Notably, many tourism studies have found inconsistent results when examining the relationships among these three components. For instance, Rollero and De Piccoli [44] argued that affection for a destination can enhance its cognitive evaluation, while Li et al. [45] found that tourists develop a special feeling towards a destination following cognitive evaluation. Meanwhile, when investigating the influence of cognitive and affective images on behavioral intentions, the conative image dimension was considered redundant [46]. To underscore the complexity and formation of destination image, this study utilizes overall destination image as a construct to explore its relationship with other variables.

Studying the factors influencing destination image is crucial for destination management organizations aiming to attract and retain tourists [47], as a positive destination image can boost competitiveness, foster sustainable tourism development, and encourage repeat visits [48]. Generally, destination image is affected by external stimuli (e.g., advertisements) and personal drivers (e.g., motivation) [49]. During social media interactions, the attributes of social media significantly impact tourists’ destination image. Tourists regard information from credible sources as safer, thereby reducing their information collection and processing costs. Veasna et al. [50] verified the positive correlation between source credibility and destination image. Additionally, source homophily refers to the perceived similarity between the information source and the receiver. When information comes from sources perceived by tourists as similar to themselves in demographics, interests, or values, they are more likely to accept this information, thereby positively impacting the destination image. Furthermore, the intangible nature and high involvement of tourism services make the industry highly dependent on information. High-quality information content, including characteristics such as relevance, timeliness, completeness, added value, and interest regarding the destination and its tourist facilities, can significantly enhance tourists’ perceptions of the destination [35]. Therefore, based on the literature cited, we hypothesize the following:

H3.

Source credibility has a positive effect on destination image.

H4.

Source homophily has a positive effect on destination image.

H5.

Content quality has a positive effect on destination image.

2.6. Destination Trust

Trust originates from discussions of interpersonal relationships in psychology studies, referring to individuals’ behavior in choosing to believe despite expecting possible negative outcomes [51]. It is the core of communication and significantly influences interpersonal behavior [52]. In the tourism context, destinations, like people and products, can also be trusted entities [53], referring to tourists’ overall trust in the destination and its services, institutions, and residents [54]. From a destination marketing perspective, trust is crucial in building and maintaining close connections between the destination and travelers [55]. Travelers’ trust can reduce their uncertainty and perceived risk associated with the destination, leading them to believe that a trustworthy destination provides transparent, reliable, low-risk, and hassle-free services and experiences, thus increasing the likelihood of their visit [56].

Due to the asymmetry of tourism information, consumers are unable to experience the quality of tourism products before arriving at the destination [57]. Within the context of social media influence (SMI), content shared by social media users provides important decision-making references for consumers searching for tourism information [29]. To obtain a more accurate perception of a destination, consumers prefer to acquire information through reliable channels. Some scholars have noted that the credibility of electronic word-of-mouth sources can reduce the perceived risk of using the platform [24], thereby enhancing tourists’ trust inclination [58]. Additionally, when tourists perceive the information source as similar to themselves in demographics, values, or experiences, they are more likely to trust the provided information [59]. Moreover, high-quality content is essential for building destination trust, as accurate and comprehensive information helps tourists reduce uncertainty and make informed decisions [60]. Finally, similarly to how brand image can positively affect satisfaction and trust, a positive destination image, characterized by appealing features, rich culture, and good experiences, will enhance tourists’ trust in selecting it [61]. Thus, based on the above discussion, we hypothesize the following:

H6.

Source credibility can positively impact destination trust.

H7.

Source homophily can positively impact destination trust.

H8.

Content quality can positively impact destination trust.

H9.

Destination image can positively impact destination trust.

2.7. Impulsive Travel Intention

Rooted in impulsive consumer behavior within a marketing context, Laesser and Dolnicar [9] argued that impulsive purchasing can also occur in destination selection and developed the concept of impulsive travel intention. Impulsive travel intention refers to the sudden desire and inclination to travel immediately, experienced by tourists after being stimulated by situational factors [62]. According to Strack and Deutsch [63]’s dual-systems model, an individual’s behavior results from the interaction between reflective (deliberative) and impulsive (automatic) systems. Impulsive travel behavior occurs when the impulsive system, driven by affective responses and immediate gratification, overrides the reflective system. Identifying impulsive travel intentions is crucial for tourism marketing. Several studies have identified key factors that trigger impulsive travel intentions, such as flow experience and trust in tourism live streaming [64] and arousal in social media contexts [12]. Leung et al. [65] conducted a systematic review of the application of social media in the tourism field, suggesting that social media have become additional information sources considered by travelers during the information search process. They can help tourists obtain information about a place, thereby increasing the likelihood of choosing that destination. High-quality content can attract and inform travelers, a positive destination image can emotionally appeal to them, and destination trust can reduce perceived risks, ultimately promoting impulsive travel decisions (Figure 1). Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Figure 1.

SOR theory and IAM.

H10.

Content quality can positively influence impulsive travel intention.

H11.

Destination image can positively influence impulsive travel intention.

H12.

Destination trust can positively influence impulsive travel intention.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

Data collection was conducted via an electronic questionnaire on the Wenjuanxing platform (www.wjx.cn) from 20 February 2024 to 12 March 2024. Wenjuanxing is a reputable online survey company in China, having published over 263 million surveys and collected 20.577 billion responses as of 16 April 2024. This study employed convenience sampling by randomly distributing questionnaire links to users commenting on popular travel posts within WeChat, RedNote, and TikTok China. Considering that individuals aged 18 and above are typically deemed mature enough to make informed decisions and handle various responsibilities (Quoquab and Mohammad [66]), our target population consisted of Chinese tourists aged 18 and above who expressed an intention to travel in the near future. Prior to participation, all individuals were provided with detailed informed consent documentation outlining the voluntary nature of this study, the confidentiality of collected data, and their right to withdraw at any time without penalty. Following the full comprehension of these protocols, participants who elected to proceed received a standardized cash honorarium upon the verified completion of the survey instrument. After filtering out questionnaires with missing values, outliers, and fast answers, a total of 419 valid responses out of 641 were used for formal analysis (validity rate = 65.4%). This exceeded the minimum sample size required to conduct SEM analysis, which is either 200 or five times the number of questionnaire items [67].

3.2. Measures

To ensure the reliability and validity of the constructs in this study, all measurement constructs were assessed using reflexive items. This study proposed six constructs: content quality, source credibility, source homophily, destination image, destination trust, and impulsive travel intention. Specifically, impulsive travel intention was measured using three items from the study by Yao, Jia, and Hou [13], including constructs such as “I feel a spontaneous urge to go traveling” “I intended to visit the destination shared by the publisher,” and “I’ll find out more about the destination”. Four items for destination trust were derived from the research of Su et al. [68], while three items measuring destination image were obtained from the work of Kuhzady et al. [69]. The constructs of content quality, source credibility, and source homophily were adapted and adopted from Onofrei et al. [70] and Filieri et al. [71], with each construct containing three items. Two experts with proficiency in English and Chinese were invited to translate the original English scales into Chinese and then back-translate from Chinese to English to ensure that the Chinese versions of the scales retained the same meanings. Additionally, demographic indicators including gender, age, education background, monthly income, daily social media usage, and the average number of trips per year were included to better understand the characteristics of the survey participants. After finalizing the questionnaire, a pilot study with 30 students majoring in tourism management was conducted to further improve the applicability and accuracy of the measurements. All measurement items were assessed on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree).

3.3. Common Method Bias Assessment

The data collection primarily relied on self-reporting surveys, which might introduce common method bias (CMB) due to respondents’ subjective factors rather than variables being studied. This bias potentially confounds study outcomes [72]. Therefore, this study applied multicollinearity detection criteria based on the variance inflation factor (VIF) to estimate the presence of CMB. The results showed that the VIF for all variables was less than 3.3 (range 1.6 to 2.957), indicating that neither multicollinearity nor common method bias was present in this study [73]. Additionally, Harman’s single-factor test results revealed that there were four factors with initial eigenvalues greater than 1, and the first factor’s cumulative variance explained was 44.5%, which was below the critical value of 50% [72]. Therefore, the sample data in this study did not exhibit a serious common method bias issue.

3.4. Data Analysis

To test the relationship among content quality, source credibility, source homophily, destination image, destination trust, and impulsive travel intention, this study employed a structural equation modeling (SEM) approach, given its validity and suitability for testing complex models [74]. Covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) offers advantages over partial least-squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in terms of theory testing and confirmation, with the measurement philosophy following a factor-based model and providing model fit indices [75]. Since this research aimed to test and validate an existing theory regarding Chinese tourists’ onsite travel intention from the perspective of information adoption theory, CB-SEM was applied to evaluate the proposed model.

This study employed a standard three-step procedure comprising exploratory factor analysis (EFA), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and hypothesis testing to analyze collected data. Initially, participants’ demographic characteristics and the reliability of all constructs were assessed using SPSS (Statistical Product and Service Solutions) 25.0. Subsequently, AMOS (Analysis of Moment Structures) 24.0 was utilized to evaluate the component reliability (CR) and convergent validity (AVE) of the above constructs. Finally, the proposed hypotheses were confirmed, with significance tested by evaluating each path and the model fit [76].

4. Results

4.1. Sample Demographics

Table 1 presents the demographic profiles of the respondents. Females constituted 54.2% of the sample, higher than males at 45.8%. The age distribution was predominantly within the 18–24 years old category (51.8%) and the 25–34 years old category (29.6%). Regarding monthly income, 37.5% reported earning CNY 6001–9000, 27% reported CNY 9001–12,000, and 21.2% reported CNY 3001–6000. In terms of educational background, approximately 68.5% of participants held a college or university degree. Daily social media usage among the respondents was distributed as follows: less than 1 h (6.4%), 1–3 h (32.9%), 3–6 h (40.8%), and more than 6 h (19.8%). Among the survey respondents, the most frequent number of trips per year was 4–6 (69.7%), followed by less than 3 (20.8%), 7–9 (7.2%), and more than 10 (2.4%).

Table 1.

An overview of the respondents (n = 419).

4.2. Measurement Model

Before conducting SEM, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was employed to explore the dimensions of each construct variable and identity indicators which caused significant cross-loading and multicollinearity. As all items’ factor loadings were larger than 0.5 and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value was 0.932, no item was moved.

The current study conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess the measurement model containing six latent variables. The results presented in Table 2 indicate a satisfactory model fit, with χ2 = 376.617 (p < 0.05); df = 155; χ2/df = 2.43; GFI = 0.923; CFI = 0.953; NFI = 0.923; NNFI = 0.942; and RMSEA = 0.058. To verify the reliability of the measurement model in this study, Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR) were used. The constructs and the scale demonstrated adequate reliability, as both Cronbach’s alpha values (ranging from 0.757 to 0.903) and CR values (ranging from 0.759 to 0.904) in the model exceeded the recommended levels of 0.7. As shown in Table 2, all factor loadings (ranging from 0.791 to 0.9) surpassed the 0.7 threshold, and the average variance extracted for all constructs exceeded the threshold of 0.5, confirming acceptable convergent and discriminant validity. Furthermore, Table 3 shows that the square root of all AVE values was consistently greater than the correlation coefficients between different constructs [77].

Table 2.

The assessment of the measurement model.

Table 3.

The results of the discriminant validity test.

4.3. Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

This study employed structural equation modeling (SEM) to test all hypothesized relationships using AMOS 24. Table 4 demonstrates that the proposed model is tenable, featuring χ2 = 338.329 (p < 0.05); df = 139; χ2/df = 2.434; GFI = 0.925; CFI = 0.954; NFI = 0.925; NNFI = 0.943; and RMSEA = 0.059 [78,79]. Subsequently, we examined the standardized regression weights of each path in the research model by using the path coefficient (β) and its significance (p-value). Specifically, source credibility (β = 0.399; p < 0.001) and source homophily (β = 0.467; p < 0.001) have significant effects on content quality, lending support to H1 and H2. Source credibility (β = 0.605; p < 0.001) and content quality (β = 0.292; p < 0.001) significantly positively impact destination image, while source homophily does not have a significant effect on destination image (β = 0.042; p > 0.05). Thus, H3 and H5 are supported, whereas H4 is not supported. Source credibility (β = 0.305; p < 0.01) and source homophily (β = 0.133; p < 0.05) are found to be positively related to destination trust, thereby supporting H6 and H7. However, content quality (β = 0.046; p > 0.05) fails to demonstrate a significant direct effect on destination trust, rejecting H8. Destination image (β = 0.453; p < 0.001) exerts a significant effect on destination trust. Thus, H9 is supported. Moreover, impulsive travel intention is positively affected by content quality (β = 0.177; p < 0.01), destination image (β = 0.174; p < 0.05), and destination trust (β = 0.529; p < 0.001); therefore, H10, H11, and H12 are supported.

Table 4.

Hypothesis testing results.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

To investigate the influence of interactions on social media on potential tourists’ intentions toward destinations, this research developed and tested a model by integrating the informational predictors of information adoption theory [18], destination image, destination trust, and impulsive travel intention in the tourism field. This approach yielded several theoretical and practical contributions.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

From a theoretical standpoint, this study proposes a dual-theoretical framework integrating the Information Adoption Model (IAM) and Stimulus–Organism–Response (S-O-R) paradigm to elucidate the formation mechanism of impulsive travel intention among social media users: initial exposure to an information stimulus (S) and the perception of informational usefulness (IP) through social media activates psychological processing within the organism (O), leading to the development of intrinsic evaluation (IE) regarding destination image and trust, which subsequently drive the adoption (IA) and response (R) of impulsive travel intention. Our study advances the literature on the applicability of information adoption theory in the tourism domain by empirically demonstrating that source credibility, source homophily, and content quality have significant impacts on forming a positive destination image and destination trust, which can ultimately stimulate impulsive travel intention. Although these constructs are widely accepted strategies in destination marketing, and impulsive travel intention has become an important segment of the tourism industry, only a few studies have examined impulsive travel intention in the fields of travel live streaming [64] and sharing social media content [13]. Consumers’ interactions on social media can be viewed as a value co-creation behavior, making it important to investigate the unique processes that generate impulsive travel intention in social media interactions.

First, this study reveals that source credibility and source homophily have a significantly positive effect on content quality. This conclusion aligns with previous studies [2,33,36], where source credibility and source homophily have been pivotal in influencing audiences’ acceptance and evaluation of information. For instance, Filieri, Acikgoz, and Du [33] suggested that information provided by an expert can be perceived as believable and diagnostic, which is useful for consumers to evaluate the expected quality and performance of products and services and to further make purchase decisions. In the context of tourism, credible sources—such as well-regarded travel bloggers, established tourism websites, and official tourism boards—are seen as more reliable, which in turn reduces perceived risk [80] but enhances the perceived value and quality of the information they provide [81]. Additionally, according to the attraction paradigm [82], individuals are easily attracted by others who are similar to themselves, and messages delivered through homophilous ties are more influential. Filieri, McLeay, Tsui, and Lin [36] found that consumers’ perceived quality and usefulness of content are significantly affected by homophilous ties. In practical terms, this means that travelers are more receptive to advice from peers or from those they perceive as having similar tastes and experiences [11].

Second, both source credibility and content quality have been found to significantly enhance destination image, corroborating prior studies that emphasize the importance of trustworthy and high-quality information in shaping tourists’ perceptions of destinations [35,83,84]. The positive influence of source credibility on destination image aligns with the principles of source credibility theory, which posits that information from expert and reliable communication sources is more persuasive [26]. Credible sources in the tourism sector, such as respected travel agencies, renowned travel bloggers, or official tourism websites, are likely perceived as more reliable, thus positively influencing destination image. Similarly, well-crafted, accurate, and detailed content on social media can aid users’ image formation of tourism destinations. This finding is consistent with the research by Kim, Lee, Shin, and Yang [35], who confirmed that the quality of tourism information provided on Sina Weibo has a positive effect on the formation of cognitive, emotional, and conative images. Once tourists regard the quality of destination information as effective, positive cognition and emotion toward destinations will be enhanced [84]. Moreover, although source homophily can trigger users’ positive attitudes [85] and induce the desire to imitate someone [86], our findings do not reveal a significant relationship between source homophily and destination image, which is intriguing in the field of tourism marketing. We offer a possible explanation that travel behavior, involving financial and emotional investment, may lead travelers to prioritize accurate and detailed information over similarity to the content provider. Certain types of content, particularly objective information like safety, accessibility, and amenities, may rely less on personal similarity for their effectiveness compared to subjective content like reviews or experiential narratives.

Third, this study demonstrates that source credibility, source homophily, and destination image significantly predict destination trust, whereas content quality has no such effect. Previous studies have argued that trust is a positive attitude comprising two sources: ability and integrity [87]. On the one hand, according to trust transfer theory, consumer trust can be transferred from a reliable media source to the destination in the tourism context [88,89]. Credible sources likely convey reliability and expertise, which are critical in reducing perceived risks associated with travel decisions, thereby enhancing trust in the destination. On the other hand, the significant role of source homophily in predicting destination trust underscores the similarity–attraction theory [82], which suggests that individuals are more likely to trust information from sources they perceive as similar to themselves. When potential tourists see themselves reflected in the source (e.g., similar backgrounds, preferences, or experiences), their trust in the information and, by extension, the destination increases. Moreover, this finding supports the conclusions of Chen and Phou [90], who reported that a favorable destination image can serve as a heuristic that simplifies the destination trust-building process. However, contrary to the results of Wang and Yan [60], this study shows that no significant relationship exists between content quality and destination trust. Wang and Yan [60] argued that tourists’ decision-making is the result of the joint action of rationality and sensibility, and trust mediates the relationship between information quality and impulsive travel intention. It is possible that while content quality is generally important, its influence on destination trust may be overshadowed by more dominant factors such as source credibility and source homophily. Another explanation concerns the mismatch between content and consumers’ expectations. For example, content that is highly detailed and accurate but fails to address safety concerns that are primarily in mind for a particular audience might not enhance trust.

Finally, we find that content quality, destination image, and destination trust are significant positive predictors in influencing users’ impulsive travel intentions, in line with previous studies [47,48,68,91,92,93]. Consumers always process information to reduce its ambiguity and uncertainty before making a decision [91]. High-quality content, which includes accuracy, relevance, and the engaging nature of the information, likely helps potential tourists to form a clearer and more attractive picture of the destination, facilitating a more confident travel decision. Furthermore, aligning with the results reported by Maghrifani, Liu, and Sneddon [48], Pham and Khanh [92], and Wu and Liang [47], our findings confirm that a positive destination image significantly enhances impulsive travel intention. This positive image functions as a mental summary of the destination attributes, resulting in strong relations with potential tourists’ intentions to visit. Additionally, destination trust is proven to contribute to impulsive travel intentions in this study. Liang, Huo, and Luo [64] claimed that trust in a destination reduces perceived uncertainty and risk associated with travel, thereby encouraging booking behaviors.

5.2. Practical Implications

Social media, as platforms for information dissemination, have become one of the main channels for tourism destination marketing. Understanding the triggers of users’ impulsive travel behavior intentions and their information adoption pathways can help destinations conduct targeted advertising, optimize marketing strategies, and enhance operational efficiency. Important managerial implications can be derived from our study’s findings for full-time vloggers and destination practitioners. First, given that credibility and homophily of the source significantly influence content quality, platform administrators should provide visible information that clearly represents publishers’ professional knowledge level and personal characteristics (backgrounds, tastes, or experiences). Source credibility can be measured through metrics such as likes, views, collections, and shares on a website or through ‘travel expert certification’ programs and transparency in communications issued by the destination. Meanwhile, tourism marketers should focus on establishing and maintaining high credibility for their information sources, which can be achieved by collaborating with well-regarded travel bloggers, reputable tourism websites, and official tourism boards. Additionally, destination marketers should identify and target niche markets, fostering a sense of community homophily. To develop tailored marketing campaigns based on community-driven content, it is useful to train or collaborate with knowledgeable influencers who share traits with the target audience within the community.

Furthermore, source credibility and content quality are critical antecedents of destination image. When tourism organizations post comprehensive and detailed information about their destinations, particularly emphasizing safety, accessibility, and amenities, potential tourists are more likely to form a positive destination image. For example, a city tourism board could develop a series of detailed guides and profiles about the city’s attractions, accommodations, transportation options, and safety protocols. These guides could be hosted on their official website and promoted through social media platforms. By focusing on the quality and reliability of the information, rather than solely on similarity and personal affinity (homophily), a destination can effectively enhance its image as a safe, accessible, and well-equipped place for tourists. This approach is particularly effective for attracting those who make travel decisions based on thorough research and objective evaluations, thereby broadening the destination’s appeal to a more diverse audience. In addition, tourism operators should consider providing training for content creators on best practices in digital storytelling and factual reporting to improve the overall quality of content available to potential tourists. Moreover, Eman and Refaie [91] suggest that governments should put more effort into managing and supervising the information posted on social media networks, thereby ensuring source credibility and information quality.

Third, considering that destination trust has a greater positive impact on impulsive travel intention than content quality and destination image, trust has become a top priority for destination managers when aiming to establish strong relationships with potential tourists. Tourism organizations should consider developing marketing strategies that are highly personalized and customized to reflect the backgrounds, preferences, and experiences of their target audience. Additionally, to enhance the credibility of information, destinations should ensure that all promotional materials are vetted for accuracy and include endorsements from reputable local businesses or previous visitors. This could include testimonials, safety certifications, and detailed descriptions of local healthcare facilities, which are critical factors in building trust, particularly among families. By seeing their own values and preferences reflected in the marketing materials and recognizing the source’s credibility, potential tourists are more likely to develop a trusting relationship with the destination. This approach not only enhances trust but also leverages emotional connections, making the destination more appealing and increasing the likelihood of travel decisions favoring the destination.

5.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

This study identifies several limitations that suggest directions for future research. The first significant limitation is that the sample was restricted to social media users in China, making the findings not generalizable to other countries due to cross-cultural differences. Future research could investigate and compare potential tourists on other international social media platforms, such as Instagram and Facebook. Moreover, this study employed a convenience sampling approach by randomly selecting social media users engaged with travel-related content, rather than specifically targeting potential visitors of particular destinations. This methodological approach may have introduced certain limitations in the practical implementation of the derived recommendations. Another limitation is that the influence of content creators may vary based on their types, such as bloggers sponsored by tourism institutions versus users who share their travel experiences independently. It would be interesting to explore whether source types entail significant differences in future studies. Additionally, the current study did not address other variables related to source and content, such as website/platform design, content self-congruity, or normative influences. Future research could consider exploring the effects of these variables, thereby forming a more comprehensive understanding of potential tourists’ travel intentions triggered by information on social media.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W. and K.-S.P.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.W. and H.L.; writing—review and editing, K.-S.P.; methodology, H.L. and W.Z.; supervision, K.-S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Pai Chai University research grant in 2025.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Department of Leisure Service and Sports (PCU-LS-2024-01-001 and 3 February 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request. The data are not publicly available because they are also part of an ongoing study and cannot be publicly shared for the time being.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Blackshaw, P. The Consumer-Generated Surveillance Culture. 2006. Available online: http://www.clickz.com/showPage.html?page=3576076 (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Ismagilova, E.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Slade, E.; Williams, M.D. Electronic Word-of-Mouth (eWOM) in the Marketing Context; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. Number of Social Media Users Worldwide from 2017 to 2028. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/278414/number-of-worldwide-social-network-users/ (accessed on 14 September 2024).

- Wang, T.; Mai, X.T.; Thai, T.D.-H. Approach or avoid? The dualistic effects of envy on social media users’ behavioral intention. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 60, 102374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Gretzel, U. Impact of humour on firm-initiated social media conversations. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2018, 18, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.-T. Flow and social capital theory in online impulse buying. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2277–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilipiri, E.; Papaioannou, E.; Kotzaivazoglou, I. Social media and influencer marketing for promoting sustainable tourism destinations: The Instagram case. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Cheng, M. Communicating mega events on Twitter: Implications for destination marketing. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 739–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laesser, C.; Dolnicar, S. Impulse purchasing in tourism–learnings from a study in a matured market. Anatolia 2012, 23, 268–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Gretzel, U. A taxonomy of value co-creation on Weibo–a communication perspective. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 2075–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado Carvalho, M.A. Influencing the follower behavior: The role of homophily and perceived usefulness, credibility and enjoyability of travel content. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2024, 7, 1091–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Jia, G. The Effect of Social Media Travel Experience Sharing on Potential Tourists’ Impulsive travel intention: Based on Presence Perspective. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2021, 24, 72–82. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; Jia, G.; Hou, Y. Impulsive travel intention induced by sharing conspicuous travel experience on social media: A moderated mediation analysis. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 49, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.-Q.; Ruan, W.-Q.; Zhang, S.-N. Owned media or earned media? The influence of social media types on impulse buying intention in internet celebrity restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 111, 103487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Chen, H. Millennial social media users’ intention to travel: The moderating role of social media influencer following behavior. Int. Hosp. Rev. 2022, 36, 340–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, K.-H.; Choi, J.-A. Trust in e-tourism: Antecedents and consequences of trust in travel-related user-generated content. In Handbook of e-Tourism; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1039–1065. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.J.; Lee, C.-K.; Jung, T. Exploring consumer behavior in virtual reality tourism using an extended stimulus-organism-response model. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, S.W.; Siegal, W.S. Informational influence in organizations: An integrated approach to knowledge adoption. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Bitner, M.J. Servicescapes: The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, M.T.; Sharmin, F.; Badulescu, A.; Gavrilut, D.; Xue, K. Social media-based content towards image formation: A new approach to the selection of sustainable destinations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahrudin, P.; Hsieh, T.-H.; Liu, L.-W.; Wang, C.-C. The role of information sources on tourist behavior post-earthquake disaster in Indonesia: A Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkan, I.; Evans, C. The influence of eWOM in social media on consumers’ purchase intentions: An extended approach to information adoption. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 61, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Ahmed, W.; Jafar, R.M.S.; Rabnawaz, A.; Jianzhou, Y. eWOM source credibility, perceived risk and food product customer’s information adoption. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 66, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.; Lee, Y.-J. Social media and brand purchase: Quantifying the effects of exposures to earned and owned social media activities in a two-stage decision making model. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2015, 32, 204–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovland, C.I.; Janis, I.L.; Kelley, H.H. Communication and Persuasion; Yale University Press: New Haven, GT, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, A.; Stürzl, W.; Zeil, J.; Cheng, K. The information content of panoramic images II: View-based navigation in nonrectangular experimental arenas. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. Behav. Process. 2008, 34, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, D.A.; Crompton, J.L. Quality, satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 785–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, R.-A.; Săplăcan, Z.; Dabija, D.-C.; Alt, M.-A. The impact of social media influencers on travel decisions: The role of trust in consumer decision journey. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 823–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. A theory of social comparison processes. Hum. Relat. 1954, 7, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladhari, R.; Massa, E.; Skandrani, H. YouTube vloggers’ popularity and influence: The roles of homophily, emotional attachment, and expertise. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 102027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kandampully, J.; Bilgihan, A. The influence of eWOM communications: An application of online social network framework. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 80, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R.; Acikgoz, F.; Du, H. Electronic word-of-mouth from video bloggers: The role of content quality and source homophily across hedonic and utilitarian products. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 160, 113774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, M.; Zeng, J.; Hao, H.; Lin, H.-C.K.; Xiao, M. Use of Latent Dirichlet Allocation and Structural Equation Modeling in Determining the Factors for Continuance Intention of Knowledge Payment Platform. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-E.; Lee, K.Y.; Shin, S.I.; Yang, S.-B. Effects of tourism information quality in social media on destination image formation: The case of Sina Weibo. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 687–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R.; McLeay, F.; Tsui, B.; Lin, Z. Consumer perceptions of information helpfulness and determinants of purchase intention in online consumer reviews of services. Inf. Manag. 2018, 55, 956–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, W.C. Image formation process. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1994, 2, 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S.; Brinberg, D. Affective images of tourism destinations. J. Travel Res. 1997, 35, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, D.; Kaplanidou, K.; Apostolopoulou, A. Destination image components and word-of-mouth intentions in urban tourism: A multigroup approach. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 42, 503–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S. Destination Marketing Organisations; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, W.-K.; Wu, C.-E. An investigation of the relationships among destination familiarity, destination image and future visit intention. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2016, 5, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Seyfi, S.; Rastegar, R.; Hall, C.M. Destination image during the COVID-19 pandemic and future travel behavior: The moderating role of past experience. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 21, 100620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Kim, L.H.; Im, H.H. A model of destination branding: Integrating the concepts of the branding and destination image. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollero, C.; De Piccoli, N. Place attachment, identification and environment perception: An empirical study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Cai, L.A.; Lehto, X.Y.; Huang, J. A missing link in understanding revisit intention—The role of motivation and image. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2010, 27, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, A.D.; Uslu, A.; Stylidis, D.; Woosnam, K.M. Place-oriented or people-oriented concepts for destination loyalty: Destination image and place attachment versus perceived distances and emotional solidarity. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 430–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Liang, L. Examining the effect of potential tourists’ wine product involvement on wine tourism destination image and travel intention. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 2278–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghrifani, D.; Liu, F.; Sneddon, J. Understanding potential and repeat visitors’ travel intentions: The roles of travel motivations, destination image, and visitor image congruity. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 1121–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S.; McCleary, K.W. A model of destination image formation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 868–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veasna, S.; Wu, W.-Y.; Huang, C.-H. The impact of destination source credibility on destination satisfaction: The mediating effects of destination attachment and destination image. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, M. Trust and suspicion. J. Confl. Resolut. 1958, 2, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Hsu, M.K.; Marshall, K.P. Understanding the relationship of service fairness, emotions, trust, and tourist behavioral intentions at a city destination in China. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2014, 31, 1018–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Jia, Y. Tourist Trustworthiness of Destination: Dimension and Its Consequence. Tour. Trib. 2013, 28, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ansi, A.; Han, H. Role of halal-friendly destination performances, value, satisfaction, and trust in generating destination image and loyalty. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 13, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.M.; Ilkan, M. Impact of online WOM on destination trust and intention to travel: A medical tourism perspective. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2016, 5, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. Image congruence and relationship quality in predicting switching intention: Conspicuousness of product use as a moderator variable. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2013, 37, 303–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Mak, B.; Li, Z. Quality deterioration in package tours: The interplay of asymmetric information and reputation. Tour. Manag. 2013, 38, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimura, T.; Lee, T.J. The impact of photographs on the online marketing for tourism: The case of Japanese-style inns. J. Vacat. Mark. 2020, 26, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, M.; Smith-Lovin, L.; Cook, J.M. Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2001, 27, 415–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yan, J. Effects of social media tourism information quality on destination travel intention: Mediation effect of self-congruity and trust. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1049149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.; Cai, L.A. Brand knowledge, trust and loyalty-a conceptual model of destination branding. In Proceedings of the International CHRIE Conference-Refereed Track, San Francisco, CA, USA, 29–31 July 2009; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Park, K.; Roehl, W.S. Exploring Unplanned/Impulsive Travel Decision Making. In Proceedings of the 2010 TTRA International Conference, San Antonio, TX, USA, 20–22 June 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Strack, F.; Deutsch, R. Reflective and impulsive determinants of social behavior. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2004, 8, 220–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Huo, Y.; Luo, P. What drives impulsive travel intention in tourism live streaming? A chain mediation model based on SOR framework. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2024, 41, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, D.; Law, R.; Van Hoof, H.; Buhalis, D. Social media in tourism and hospitality: A literature review. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quoquab, F.; Mohammad, J. The salient role of media richness, host-guest relationship, and guest satisfaction in fostering Airbnb guests’ repurchase intention. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 23, 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Convergence of structural equation modeling and multilevel modeling. In The SAGE Handbook of Innovation in Social Research Methods; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2011; pp. 562–589. [Google Scholar]

- Su, L.; Lian, Q.; Huang, Y. How do tourists’ attribution of destination social responsibility motives impact trust and intention to visit? The moderating role of destination reputation. Tour. Manag. 2020, 77, 103970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhzady, S.; Çakici, C.; Olya, H.; Mohajer, B.; Han, H. Couchsurfing involvement in non-profit peer-to-peer accommodations and its impact on destination image, familiarity, and behavioral intentions. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onofrei, G.; Filieri, R.; Kennedy, L. Social media interactions, purchase intention, and behavioural engagement: The mediating role of source and content factors. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R.; Alguezaui, S.; McLeay, F. Why do travelers trust TripAdvisor? Antecedents of trust towards consumer-generated media and its influence on recommendation adoption and word of mouth. Tour. Manag. 2015, 51, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. e-Collab. (IJeC) 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, C.; Schermelleh-Engel, K. Structural equation modeling: Advantages, challenges, and problems. In Introduction to Structural Equation Modeling with LISREL; Goethe University: Frankfurt, Germany, 2009; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Dash, G.; Paul, J. CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 173, 121092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate Data Analysis; Cengage Learning, EMEA: Hampshire, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- González-Rodríguez, M.R.; Díaz-Fernández, M.C.; Bilgihan, A.; Okumus, F.; Shi, F. The impact of eWOM source credibility on destination visit intention and online involvement: A case of Chinese tourists. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2022, 13, 855–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Noone, B.M.; Robson, S.K. An exploration of the effects of photograph content, photograph source, and price on consumers’ online travel booking intentions. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 120–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D. An overview (and underview) of research and theory within the attraction paradigm. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 1997, 14, 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Wang, X.; Wu, M.-Y.; Wei, W.; Morrison, A.M.; Kelly, C. The effect of destination source credibility on tourist environmentally responsible behavior: An application of stimulus-organism-response theory. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 1797–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanzadeh, D.; Zakieva, R.R.; Kuznetsova, M.; Ismael, A.M.; Ahmed, A.A.A. Generating destination brand awareness and image through the firm’s social media. Kybernetes 2022, 52, 3292–3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muda, M.; Hamzah, M.I. Should I suggest this YouTube clip? The impact of UGC source credibility on eWOM and purchase intention. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021, 15, 441–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargsyan, M.; Shin, H.-R.; Choi, J.-G. The Effect of Influencer Attributes on Consumer Behavior Intention in the Hotel Industry: The Mediating Role of Mimetic Desire. Korean J. Hosp. Tour. 2023, 32, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penagos-Londoño, G.I.; Rodriguez–Sanchez, C.; Ruiz-Moreno, F.; Torres, E. A machine learning approach to segmentation of tourists based on perceived destination sustainability and trustworthiness. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hyun, S.S.; Lee, T.J. The effects of parasocial interaction, authenticity, and self-congruity on the formation of consumer trust in online travel agencies. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 24, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Hong, I.B. Consumer’s electronic word-of-mouth adoption: The trust transfer perspective. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2019, 23, 595–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F.; Phou, S. A closer look at destination: Image, personality, relationship and loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eman, N.; Refaie, N. The effect of Instagram posts on tourists’ destination perception and visiting intention. J. Vacat. Mark. 2023, 31, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H.S.T.; Khanh, C.N.T. Ecotourism intention: The roles of environmental concern, time perspective and destination image. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 1141–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Yang, Q.; Swanson, S.R.; Chen, N.C. The impact of online reviews on destination trust and travel intention: The moderating role of online review trustworthiness. J. Vacat. Mark. 2022, 28, 406–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).