Abstract

This study examines the adoption and institutionalization of Green Human Resource Management (Green HRM) in Malaysian SMEs, focusing on the influence of Perceived Organizational Green Readiness (POG) and Perceived External Green Readiness (PEG) on the institutionalization of Green HRM (ING). Utilizing structural equation modeling from a sample of 425 respondents for Malaysian SMEs, the research reveals that POG and PEG significantly predict the Initial adoption of Green HRM (IAG), which mediates their impact on ING. This study also identifies a moderating role of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in the relationship between IAG and ING. Theoretical contributions extend stakeholder theory, the E-Commerce Adoption Model, the Organizational Readiness to Change (ORC) framework, and CSR theory to the Green HRM context. The findings provide practical insights for SMEs on aligning Green HRM with organizational strategies and external factors for effective institutionalization. This research contributes to the understanding of Green HRM processes, emphasizing the importance of initial adoption and the intricate role of CSR in sustainable business practices.

1. Introduction

In response to escalating environmental concerns, organizations globally are integrating sustainable practices into their operational frameworks [1,2]. Green Human Resource Management (Green HRM) represents a strategic fusion of environmental stewardship and human resource (HR) management, demonstrating a commitment to environmental sustainability through HR policies and practices [3]. This research investigates the factors influencing the adoption and institutionalization of Green HRM practices, emphasizing perceived organizational and external readiness, and the moderating impact of corporate social responsibility (CSR).

Green HRM, transcending traditional HR paradigms, incorporates environmental considerations into key HR functions, including recruitment, training, and performance appraisal [4]. This strategic shift aligns environmental considerations with HR practices, fostering a sustainable organizational culture [5,6].

HR professionals are critical in driving environmental initiatives, with HR emerging as a catalyst for sustainable business practices [7]. Research by Shoaib [8] highlights how perceived Green HRM positively affects workplace outcomes, enhancing organizational commitment and developing green human capital. This underscores the strategic need to integrate environmental considerations into HR. The alignment of organizational processes with sustainability goals, influenced by various factors, is vital. Yong [9] suggests that Strategic Alignment is essential in adopting Green HRM practices, with congruence between business strategies and environmental objectives facilitating Green HRM’s institutionalization.

Pinzone [10] demonstrates how Green HRM enhances collective employee engagement in environmental protection. Jerónimo [11] emphasizes the significance of green HR practices, such as green hiring and training, in shaping organizational sustainability. Ahuja [12] and Vij [13] also highlight the role of Green HRM in promoting sustainable practices and enhancing employee commitment to sustainability. The relationship between Green HRM and corporate sustainability has been well-documented, with studies by Jamal [14] and Tanveer [15] indicating the positive impacts of green HRM practices. However, adopting Green HRM is challenging. Muisyo [16] asserts that a green innovation culture is crucial for enhancing competitive advantage. Arulrajah [17] and Nawangsari [18] provide comprehensive reviews of Green HRM practices, while Nejati [19] explores the challenges and benefits, including impacts on employee performance.

While existing research has shed light on the role of industry-specific practices, institutional pressures, and government initiatives in fostering the adoption of Green Human Resource Management (Green HRM), there remains a gap in understanding the full spectrum of influences on its adoption and institutionalization. Particularly, the growing academic focus on the role of corporate social responsibility (CSR) as a moderating factor in this process highlights a critical area for further exploration [20]. Ahmed’s work [21] underscores the significance of institutional pressures as catalysts for green initiatives, suggesting that these external factors play a crucial role in driving Green HRM adoption. However, the transition to Green HRM is not straightforward and is marked by complexities.

This indicates a research gap in fully comprehending how both internal and external factors collectively shape an organization’s trajectory toward Green HRM. Understanding these dynamics is essential for a more comprehensive grasp of the challenges and enablers in the successful adoption and deep-rooted institutionalization of Green HRM practices [22,23]. Addressing this gap could provide invaluable insights for organizations striving to integrate sustainable practices effectively within their operational frameworks, and this study addresses two key research questions:

- How do Perceived Organizational and External Green Readiness influence the institutionalization of Green HRM Practices?

- What role does CSR play in moderating the relationship between the adoption and institutionalization of Green HRM Practices?

Employing a quantitative research design in Malaysia, this study focuses on SMEs across various industries. Data will be collected through structured surveys targeting HR professionals and organizational leaders. An analysis using Smart PLS4 [24] will offer sophisticated insights into the relationships between multiple variables.

This study breaks new ground in the field of Green Human Resource Management (Green HRM) by uniquely combining the perspectives of Perceived Organizational and External Green Readiness with the moderating role of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in the Malaysian context. While prior research has addressed these elements in isolation [25], this study integrates them within a single analytical framework, drawing on the theoretical underpinnings of institutional theory and stakeholder theory [22,26]. The focus on Malaysia, a rapidly developing economy with an increasing emphasis on sustainable practices [6,14,15], adds to the study’s originality by exploring Green HRM in a unique cultural and institutional context. Moreover, the use of Smart PLS4 for analysis [27] introduces a sophisticated methodological approach, addressing calls for more robust statistical methods in HRM research [28]. This approach provides enhanced accuracy and reliability, contributing new insights into the dynamic field of Green HRM.

The implications of this study are manifold and are poised to contribute significantly to both academic discourse and practical application in sustainable business practices. This study aims to expand the Green HRM knowledge base by examining the interplay between organizational readiness, external environmental factors, and the institutionalization of green practices within HR frameworks [3,29]. The findings will enlighten HR professionals and policymakers on the drivers and barriers of implementing Green HRM, fostering a culture committed to sustainability. Insights into CSR’s effectiveness as a moderating factor could guide organizations in leveraging CSR initiatives to enhance Green HRM practices. Furthermore, this research should inform governmental and industry stakeholders in creating supportive policies that encourage organizations to pursue sustainability through their HR strategies [14,15]. Ultimately, this study aims to delineate a clear and novel pathway for organizations to align their HR practices with environmental sustainability goals, contributing to the overarching goal of corporate social responsibility and sustainable development.

2. Green HRM

Green Human Resource Management (Green HRM) integrates environmental management with human resource (HR) policies and practices, focusing on sustainability within the workforce. Renwick, Redman, and Maguire [3] define Green HRM as a collection of practices that contribute to the sustainable use of business resources and the minimization of environmental impact. This literature review explores Green HRM through its key components: selection and recruitment, training and development, and compensation and reward.

The selection and recruitment process in Green HRM plays a pivotal role in promoting a sustainability-oriented culture within an organization. Jabbour and Santos [30] emphasize the importance of integrating environmental criteria into the recruitment process. They suggest attracting candidates who not only possess the required skills but also demonstrate a commitment to environmental sustainability. This approach aligns with the findings of Jerónimo [11], who notes that green hiring practices are integral to developing an organizational rationale for sustainability. Furthermore, Ahuja [12] and Vij [13] highlight that recruiting individuals with a pro-environmental attitude fosters a workforce that is more inclined toward sustainable practices.

Green HRM significantly encompasses training and development aimed at enhancing environmental awareness and skills among employees [31]. Jackson, Renwick, Jabbour, and Muller-Camen [5] argue that training programs focused on environmental management equip employees with the knowledge and skills needed to contribute to an organization’s green objectives. These programs can range from basic environmental awareness to advanced training in specific green technologies or practices. Pinzone [10] supports this view, demonstrating how training initiatives can facilitate collective employee engagement in environmental protection and promote voluntary pro-environmental behaviors.

Compensation and reward systems in Green HRM are designed to incentivize sustainable practices among employees. According to Shoaib [8], aligning reward systems with environmental performance metrics can significantly enhance organizational commitment toward green initiatives. This alignment encourages employees to participate actively in the organization’s sustainability efforts. The effectiveness of such systems is further supported by studies, such as Muisyo [16] and Arulrajah [17], who note that incorporating environmental criteria into performance appraisals and reward structures can drive the successful implementation of Green HRM practices.

Integrating these components into a cohesive Green HRM strategy poses challenges. Nejati [19] and Devi [32] highlight potential obstacles, including resistance to change and the need for alignment with overall business strategies identified by Yong [9]. However, the benefits, as evidenced by improved environmental performance and enhanced employee engagement in sustainability initiatives [14,15], justify the efforts to overcome these challenges.

In conclusion, the literature on Green HRM underscores the importance of integrating environmental sustainability into various HR practices. Effective selection and recruitment processes can build a workforce committed to environmental goals, while training and development initiatives enhance the necessary skills and awareness. Furthermore, aligning compensation and reward systems with environmental performance incentivizes employees toward sustainable practices. As organizations increasingly recognize the importance of sustainability, Green HRM emerges as a crucial strategy for achieving environmental objectives while enhancing organizational performance.

3. Theoretical Understanding

The theoretical underpinnings of this study on Green Human Resource Management (Green HRM) in Malaysia are informed by a blend of theories, each contributing distinct perspectives on the adoption and institutionalization of Green HRM practices.

Stakeholder theory, as conceptualized by Barney [26] and Freeman [22], is instrumental in understanding how organizations align Green HRM practices with the expectations of various stakeholders, including employees, customers, suppliers, and the broader community. This theory underscores the importance of considering stakeholder demands in the adoption of Green HRM practices as a response to environmental, social, and ethical responsibilities [33]. Despite its limitations in addressing non-human interests [34], stakeholder theory remains a valuable framework for managing stakeholder relationships in various international business contexts [35].

The E-Commerce Adoption Model by Molla and Licker [36] provides insights into organizational innovation adoption, emphasizing the significance of both organizational and external readiness in the adoption process. This model has been applied in studies exploring e-commerce adoption in developing countries [37,38] and green innovation adoption, highlighting its applicability to various organizational innovation processes.

The Organizational Readiness for Change (ORC) framework, developed by Weiner [39] and expanded by Cardinal et al. [40], examines Change Commitment and Change Efficacy, which are crucial in assessing an organization’s readiness for Green HRM. Studies by Lehman [41], Piotrowska-Bożek [42] have applied this framework to assess organizational readiness for change, validating its effectiveness in various contexts.

Environmental determinism posits that external factors, such as market dynamics and regulatory requirements, significantly shape an organization’s structure and practices [23]. This theory is echoed in research by Livingstone [43], emphasizing the influence of external factors on Green HRM adoption.

CSR theory argues that organizations should extend their responsibilities to encompass ethical and environmental considerations [22]. Studies by Atiku [20] and Babiak [44] support this theory, highlighting the role of CSR in promoting green behavior and environmental responsibility within organizations.

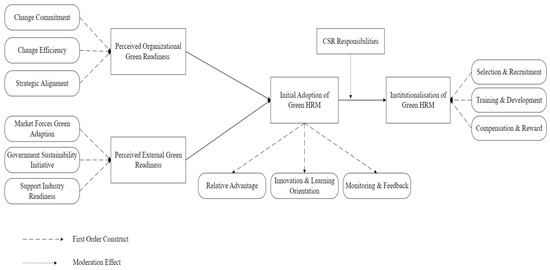

In summary, these theories collectively provide a comprehensive framework for this study [22,26,36,38,39]. They offer novel multi-dimensional insights into the factors influencing the adoption and institutionalization of Green HRM in Malaysia (Figure 1), highlighting the interplay of internal readiness, external environmental forces, and CSR’s overarching influence.

Figure 1.

Research framework.

4. Hypothesis Development

4.1. Institutionalization of Green HRM, Perceived Organizational Green Readiness, and External Green Readiness

This study’s exploration into the institutionalization of Green Human Resource Management (Green HRM), alongside the facets of Perceived Organizational Green Readiness and External Green Readiness, unveils critical insights into the dynamics of sustainable practices within organizations. Perceived Organizational Green Readiness, encompassing Change Commitment, Change Efficiency, and Strategic Alignment, emerges as a pivotal factor [45]. Research by AlZgool [46] illuminates a positive correlation between perceived Green HRM and employee workplace outcomes, with AlZgool further noting the moderating role of green management. AnuSingh [47] and Hameed [48] underscore the beneficial impacts of Green HRM on both environmental performance and employee behaviors. In similar a vein, Aboramadan [49] and Zaki [50] highlight the enhancement of job performance and employee motivation under the aegis of Green HRM, with the former emphasizing the mediating influence of perceived green organizational support. Roscoe [51] and Islam [52] extend this discourse to the enablers of green organizational culture and the mediating functions of Green HRM in fostering green behaviors. These studies collectively validate the significant relationship posited:

There is a significant relationship between Perceived Organizational Green Readiness and the institutionalization of Green HRM.

Furthermore, Perceived External Green Readiness, formed through Market Forces Green Adoption, Government Sustainability Initiatives, and Support Industry Readiness, is also crucial [53,54]. AlZgool [46] draws connections between perceived Green HRM and various workplace outcomes, including those not directly tied to green initiatives, with AlZgool accentuating green management’s moderating role. Ojo [55] and Jamal [14] emphasize the criticality of Green HRM practices in spurring pro-environmental behavior and bolstering corporate sustainability. Yusoff [56] and Aboramadan [49] broaden these findings to specific sectors, like the hospitality industry and higher education. AnuSingh [47] and Aboramadan [49] demonstrate the impacts of Green HRM on environmental performance in distinct settings, such as manufacturing and hospitality. Together, these studies support H1:

H1.

There is a significant relationship between Perceived External Green Readiness and the institutionalization of Green HRM.

The initial adoption of Green HRM, encompassing Relative Advantage, Innovation and Learning Orientation, and Monitoring and Feedback, is also identified as a key mediator [57]. AlZgool [46] and Yusoff [58] observe a positive association between Green HRM and individual green values, with Yusoff pinpointing factors like perceived ease of use and trust in electronic HRM. Yusoff [56] underscores the link between specific Green HRM practices and environmental performance. Aboramadan [49] brings to light the mediating role of green work engagement, while O’Donohue [59] identifies Green HRM as a moderator in the relationship between proactive environmental management and financial performance. Roscoe [51] delves into the impacts of Green HRM on non-green employee outcomes and the enablers of green organizational culture. Collectively, these findings corroborate H2:

H2.

There is a significant relationship between the initial adoption of Green HRM and the institutionalization of Green HRM.

4.2. Initial Adoption of Green HRM, Perceived Organizational Green Readiness, and External Green Readiness

This study’s exploration into the initial adoption of Green Human Resource Management (Green HRM), juxtaposed with Perceived Organizational Green Readiness and External Green Readiness, provides pivotal insights into the dynamics of sustainable practices in organizations. Research conducted by Shen [60] and Chen [61] reveals that perceived Green HRM positively affects workplace outcomes not directly related to green initiatives, facilitated by organizational identification. This is further complemented by the findings of Aboramadan [49], who delineates the positive impact of perceived Green HRM on green behaviors and outcomes in the workplace. Yusoff [58] and AlZgool [46] reinforce these observations, noting the significant relationship between Green HRM and individual green values, with AlZgool additionally pointing out the moderating influence of green management. Despite these comprehensive studies, the direct linkage between Perceived Organizational Green Readiness and the initial adoption of Green HRM remains less explicitly explored; thus:

There is a significant relationship between Perceived Organizational Green Readiness and the initial adoption of Green HRM.

Extending this discourse, Chen [61] has identified that perceived Green HRM also positively influences employee green performance and behaviors in the workplace. These findings are supported by Aboramadan [49], who noted that Green HRM predicts green behaviors among employees. Similarly, AlZgool [46] found a positive relationship between Green HRM and individual green values. Studies by Rayner [62] and Raza [63] have shown that employees’ environmental knowledge and individual green values act as moderators in the relationship between Green HRM and green behaviors. Moreover, AnuSingh [47] and Hameed [48] have documented that specific Green HRM practices, including top management commitment and the empowerment of a green workforce, significantly impact environmental performance and organizational citizenship behaviors oriented toward the environment. These studies collectively support H3:

H3.

There is a significant relationship between Perceived External Green Readiness and the initial adoption of Green HRM.

4.3. The Moderating Effect of CSR

In the realm of Green Human Resource Management (Green HRM), the moderating effect of corporate social responsibility (CSR) plays a pivotal role in the relationship between the initial adoption and institutionalization of Green HRM. This relationship, underscored by Atiku [20], is further enriched by the positive impact of Green HRM on the financial outcomes of proactive environmental management, as demonstrated by O’Donohue [59]. Shen [60] highlights the mediating influence of perceived organizational support on the impact of Green HRM on employee workplace outcomes, indicating a deeper integration of Green HRM within the organizational fabric.

The commitment of top management to CSR and Green HRM, as observed by Yusliza [64], underscores the interdependence of these two areas, with CSR influencing the adoption and effectiveness of Green HRM practices. This interplay is further nuanced by the critical role of strategic HR competencies, especially as strategic positioners and change champions, which Yong [9] identifies as significantly related to Green HRM practices. These competencies are vital in navigating the complexities associated with implementing sustainable practices within organizations.

AlZgool [46] provides insight into the moderation exerted by green management on the relationship between Green HRM and individual green values, suggesting that management practices specifically tailored to sustainability can enhance the effectiveness of Green HRM initiatives. Cheema [65] adds to this discourse by pointing out the mediating role of a sustainable environment in the relationship between CSR and Green HRM, suggesting a synergistic effect where CSR initiatives bolster the development of a sustainability-focused organizational culture.

Moreover, the role of electronic HRM and the HR business partner in implementing Green HRM practices, as described by Yusliza [66], indicates the evolving nature of HR roles in fostering an environment conducive to Green HRM. These roles are pivotal in integrating technology and strategic HR expertise to advance Green HRM initiatives; thus we develop the hypothesis 4:

H4.

CSR moderates the relationship between the initial adoption of Green HRM and the institutionalization of Green HRM.

4.4. Mediation of the Initial Adoption of Green HRM

In the context of Green Human Resource Management (Green HRM), the mediating role of the initial adoption of these practices is pivotal in bridging Perceived Organizational Green Readiness with their institutionalization. This mediating role is well-supported by Zaki [50], Pinzone [10], Guerci [33], Yong [9], Islam [52], Roscoe [51], and O’Donohue [59], who collectively underscore the importance of initial Green HRM adoption in shaping sustainable workplace outcomes and fostering a green organizational culture.

These studies emphasize that the initiation of Green HRM practices plays a crucial role in transforming stakeholder pressures and organizational readiness into tangible environmental performance and engagement. Shen [60] highlights that perceived Green HRM can influence outcomes beyond green-specific tasks, mediated significantly by organizational identification. Similarly, Guerci [10] and Zaki [50] note the mediating effects of Green HRM in converting stakeholder pressures into enhanced environmental performance and motivating employees toward environmental tasks.

Moreover, the role of Green HRM in collective environmental protection efforts and its capacity to moderate the relationship between proactive environmental management and financial performance are highlighted by Pinzone [10] and O’Donohue [59]. This dual role underscores the multifunctionality of Green HRM, not only as a driver for environmental stewardship but also as a catalyst for economic benefits.

Strategic HR competencies and ethical leadership, as discussed by Yong [9] and Islam [52], significantly influence the adoption of Green HRM practices. These competencies are essential for building a green organizational culture, subsequently affecting environmental performance. Furthermore, Muisyo [16] explores the implications of Green HRM for a firm’s green competitive advantage, identifying the enablers of a green culture as mediators in this relationship. These studies collectively validate the significant relationships posited:

H5.

The initial adoption of Green HRM mediates the relationship between Perceived Organizational Green Readiness and the institutionalization of Green HRM.

H6.

The initial adoption of Green HRM mediates the relationship between Perceived External Green Readiness and the institutionalization of Green HRM.

5. Research Methodology

5.1. Research Design and Sampling

This study utilized a cross-sectional design to explore the interrelationships between Green Human Resource Management (GHRM), Perceived Organizational Green Readiness, Perceived External Green Readiness, the initial adoption of Green HRM, and the moderating role of CSR in diverse organizational settings. The cross-sectional approach, known for its efficacy in capturing data at a single point in time, was particularly suitable for the exploratory and explanatory nature of this research in the field of organizational studies [67,68].

This study was conducted in the Klang Valley, Malaysia, a region known for its diverse range of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) [69] that is listed in the MyBiz-DATA database of the Companies Commission of Malaysia (SSM). Klang Valley, encompassing Malaysia’s economic hub, was chosen for this study due to its diverse industries, high urbanization, and significant economic activity. The region’s focus on sustainability, influenced by government initiatives, provides fertile ground for examining Green HRM practices in a dynamic, representative, and accessible urban context.

Employing a convenience sampling method, as suggested by Golloway [70], facilitated efficient access to a broad spectrum of SMEs in this area. The questionnaire, developed in English and translated into Malay, ensured comprehensive understanding among participants from different linguistic backgrounds.

Aiming for a sample size of 425, this study distributed 650 questionnaires via email to a variety of SMEs listed under the MyBiz-DATA database across Klang Valley. Using email to distribute questionnaires for the Green HRM study was chosen for its efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and convenience, allowing rapid reach across diverse SMEs in Klang Valley [71]. However, it posed challenges such as potential low response rates, a risk of emails being overlooked, and a lack of personal engagement with respondents.

Out of the responses received, 478 were suitable for initial consideration, and following a rigorous data-cleaning process, 425 responses were deemed appropriate for final analysis. This process led to a response rate of approximately 65.4%. The data cleaning procedure involved removing responses from participants who did not meet the study’s specific criteria or displayed signs of inattentive responding, including incomplete survey responses, repetitive answer patterns, ambiguous responses, or unclear answers to open-ended questions.

To address potential non-response bias, the study applied the approach recommended by Armstrong and Overton [72]. A comparison of demographic factors, such as age and gender, was conducted between the initial 55 respondents and the last 55 respondents using independent samples and chi-square T-tests. This comparison aimed to detect any significant differences between early and late respondents. The analysis revealed no significant variations between these groups (p > 0.05), indicating that non-response bias was not a concern in this study.

5.2. Measurement Development

To develop a comprehensive measurement scale for the study of Green Human Resource Management (Green HRM) within Malaysian SMEs, this research employs relevant sources from the existing literature, ensuring the validity and reliability of each construct. This study explores various constructs, each underpinned by a rich body of scholarly work, to inform their measurement and enhance understanding of Green HRM dynamics (refer to Table 1).

Table 1.

Measurement model.

Perceived Organizational Green Readiness, a critical construct, is explored through three interconnected dimensions. Change Commitment, drawing from Armenakis et al. [73] and Kotter [74], examines the organization’s commitment to implementing environmental changes. Change Efficiency, based on Weiner [39] and Holt et al. [75], assesses the efficiency in managing resources and processes for Green HRM. Strategic Alignment, as described by Epstein and Buhovac [76] and Hart [77], focuses on aligning Green HRM practices with the overall business strategy.

In addition, Perceived External Green Readiness is scrutinized through constructs assessing the impact of external environmental factors on Green HRM. Market Forces Green Adoption, informed by Bansal and Roth [78] and Porter and van der Linde [79], evaluates the influence of market dynamics on Green HRM practices. The Government Sustainability Initiative, drawing insights from Brammer et al. [80] and Lozano [81], measures the effect of government policies on Green HRM adoption. Support Industry Readiness, based on Delmas and Toffel [82] and Waddock [83], assesses industry support for Green HRM practices.

This study also investigates the initial adoption of Green HRM. Relative Advantage, underpinned by Rogers [84] and Tornatzky and Klein [85], explores the perceived benefits and competitive advantages of implementing Green HRM practices. Innovation and Learning Orientation, based on Calantone et al. [86] and Hurley and Hult [87], assesses the commitment to innovation and continuous learning within Green HRM. Monitoring and Feedback, informed by Bos-Nehles et al. [88] and DeNisi and Pritchard [89], evaluates how organizations monitor and obtain feedback on Green HRM initiatives.

Corporate social responsibility (CSR), drawing from Aguinis and Glavas [90] and Carroll [91], focuses on the inclusion and impact of CSR initiatives on Green HRM practices.

Finally, this study delves into the institutionalization of Green HRM. Compensation and Reward, as conceptualized by Renwick, Redman, and Maguire [3] and Jackson et al. [5], examines the alignment of employee compensation and rewards with green practices. Selection and Recruitment, based on Daily, Bishop, and Govindarajulu [92] and Guerci et al. [33], evaluates how environmental sustainability criteria are integrated into recruitment processes. Training and development, informed by Jackson et al. [5], Teixeira, Jabbour, and de Sousa Jabbour [93], and Ahmed et al. [69], measure the role of training in promoting Green HRM practices.

In summary, this robust measurement development, anchored in a breadth of scholarly literature, establishes a comprehensive analytical framework to examine the multifaceted aspects of Green HRM. It provides a nuanced understanding of the internal and external factors, as well as organizational practices, shaping the adoption and institutionalization of Green HRM in the context of Malaysian SMEs. Measurement items were evaluated using a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from “1” (strongly disagree) to “5” (strongly agree), with “3” indicating a neutral position.

5.3. Data Analysis Technic

This study employed SmartPLS 4 for data analysis, focusing on the relationship between Green Human Resource Management (GHRM) practices and sustainable performance in an organizational context. SmartPLS4 was selected for its proficiency in handling complex models, which is ideal for the Green HRM study’s intricate structures. Its suitability for Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), robustness with non-normal data, user-friendly interface, flexibility in model specification, and efficient algorithm made it an optimal choice for this research [27].

GHRM, conceptualized as a second-order construct, comprised three dimensions: training and development, hiring and recruitment, and compensation and rewards. These dimensions demonstrated strong internal consistency, with Composite Reliability scores exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.7, indicating good reliability [94]. Convergent validity was also confirmed, as each dimension’s Average Variance Extracted (AVE) surpassed the 0.5 benchmark [95].

6. Data Analysis

The demographics of the respondents in this study of Green Human Resource Management (Green HRM) in Malaysia present a diverse and representative sample across various categories. The sample consists of 425 respondents, with a slightly higher percentage of males (55.3%) compared to females (44.7%), indicating a relatively balanced gender distribution. In terms of age distribution, the majority fall within the 26–35 years age group (35.3%), followed by those aged 36–45 years (30.6%). The age group above 55 years is the least represented at 7.0%, suggesting that most participants are in their early to mid-career stages (refer to Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographics of the respondents.

Educationally, the respondents predominantly hold higher degrees, with 52.9% possessing a Bachelor’s degree and possessing 29.4% a Master’s degree. A smaller fraction, 4.7%, have a Doctorate or higher, indicating that the sample is generally well-educated. Professionally, the largest group of respondents is in middle management (47.1%), followed by upper management (29.4%) and lower management (23.5%), showcasing a good mix of perspectives from various hierarchical levels within organizations (refer to Table 2).

Experience-wise, the most significant proportion of respondents has been with their current organization for 2–5 years (35.3%), with those having 6–10 years of experience making up 28.2% of the sample. This experience distribution suggests that most respondents possess substantial organizational experience, potentially having enriching insights into Green HRM practices.

Regarding the organization size, the respondents are from a range of enterprises, predominantly organizations with 51–200 employees (42.4%). Smaller organizations with less than 50 employees constitute 22.4% of the sample, and those from organizations with 201–500 employees make up 23.5%, while the least represented are larger organizations with more than 500 employees (11.7%) (refer to Table 2). This variety ensures that this study captures experiences from different organizational sizes, ranging from smaller firms to larger corporations.

Overall, this demographic profile of the respondents provides a comprehensive and varied backdrop, which is crucial for understanding the nuances of Green HRM practices across different sectors, organizational sizes, and professional backgrounds in Malaysia.

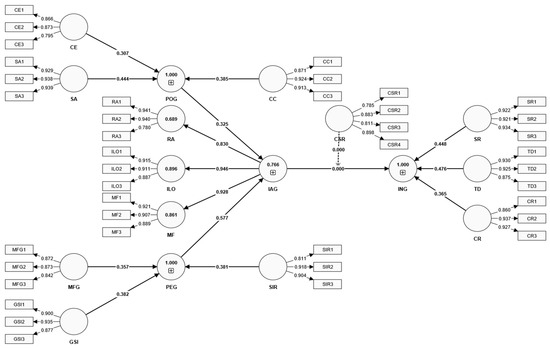

6.1. Measurement Model Evaluation

In this study, focusing on Green Human Resource Management (Green HRM) within Malaysian SMEs, the reliability and validity of the measurement model are critical for ensuring robust findings. The model, as delineated in the provided tables, encompasses a variety of constructs central to understanding Green HRM, each rigorously tested for reliability and validity (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Illustration of the measurement model (lower-order model).

The measurement model reliability is underscored by high Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) and Composite Reliability (CR, rho_c) values across all constructs. These indices surpass the recommended threshold of 0.7 [96], signifying strong internal consistency within each construct. Such high reliability indicates that the items within each construct cohesively measure a single concept, which is essential for the integrity and accuracy of the research.

Moreover, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values for each construct exceed the recommended threshold of 0.5. This finding is significant, as it suggests that a majority of the variance observed in the responses is attributable to the construct they are intended to measure (refer to Table 1). High AVE values are indicative of good construct validity, ensuring that each construct captures a substantial portion of the variance in its observed variables.

Specific constructs such as Change Commitment (CC), Compensation and Reward (CR), and Strategic Alignment (SA) display particularly high reliability and validity. This is indicative of the effectiveness of these constructs in capturing the essence of organizational commitment to environmental changes, the alignment of compensation and rewards with green practices, and the strategic integration of Green HRM with business objectives.

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) and the Government Sustainability Initiative (GSI) also exhibit strong reliability and validity, indicating their effectiveness in capturing external influences on Green HRM (refer to Table 1). These constructs are pivotal in understanding how external CSR initiatives and governmental policies shape Green HRM practices in SMEs.

Similarly, constructs pertaining to the initial adoption of Green HRM, including Innovation and Learning Orientation (ILO) and Monitoring and Feedback (MF), demonstrate strong psychometric properties (refer to Table 1). These constructs are crucial for comprehending how organizations initially adopt and subsequently monitor and refine Green HRM practices.

Lastly, Market Forces Green Adoption (MFG) and Relative Advantage (RA) are also reliable and valid, highlighting the importance of external market forces and perceived benefits in the adoption of Green HRM practices.

This study’s discriminant validity, a measure of how distinct each construct is from others within the model, is affirmed by two methods (refer to Table 3). The Heterotrait–Monotrait ratio (HTMT) matrix values fall below the threshold of 0.85 for most construct pairs, implying that the constructs are unique and measure different phenomena [97]. This is crucial in multi-construct studies, like this one, where the clarity in the distinction between constructs ensures the accuracy of the interpretation of each construct’s role in Green HRM.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity (Heterotrait–Monotrait ratio (HTMT) matrix).

Furthermore, the Fornell–Larcker criterion is satisfied, as demonstrated in Table 4. This criterion compares the square root of AVE for each construct against its correlations with other constructs. The fact that the square root of AVE (represented diagonally in the table) for each construct is higher than its correlation with other constructs reaffirms that each construct is indeed capturing a unique aspect of Green HRM, further bolstering the model’s discriminant validity.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity (Fornell–Larcker criterion).

Similarly, the Government Sustainability Initiative (GSI), Market Forces Green Adoption (MFG), and Support Industry Readiness (SIR) show a significant effect on Perceived External Green Readiness (PEG), highlighting the roles of government policies, market dynamics, and industry support in shaping external perceptions of green readiness. In the realm of the institutionalization of Green HRM (ING), Compensation and Reward (CR) exhibits a notable, albeit smaller, influence compared to Selection and Recruitment (SR) and training and development (TD), which demonstrate strong impacts (refer to Table 5). This underscores the importance of integrating green criteria in HR practices to institutionalize Green HRM within organizations. Overall, these findings provide a comprehensive view of how various factors contribute to the perception and institutionalization of Green HRM in the context of Malaysian SMEs.

Table 5.

Outer loading for the high-order formative construct.

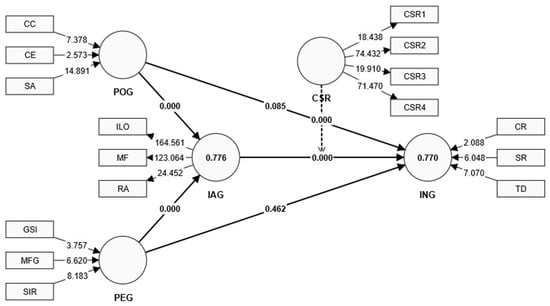

6.2. Hypothesis Testing and Discussion

The structural model depicted in Figure 3 illustrates the higher-order relationships within the context of Green Human Resource Management (Green HRM) in Malaysian SMEs. It integrates various constructs such as Change Commitment (CC), Change Efficiency (CE), Strategic Alignment (SA), and others into a coherent framework.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the structural model (higher-order model).

The structural model (Table 6) presents the results of the moderation and direct effects within the model, focusing on the relationships between corporate social responsibility (CSR), the initial adoption of Green HRM (IAG), the institutionalization of Green HRM (ING), Perceived External Green Readiness (PEG), and Perceived Organizational Green Readiness (POG).

Table 6.

Structural model (moderation and direct effect).

This study on Green Human Resource Management (Green HRM) within Malaysian SMEs provides significant insights into the relationships between Perceived Organizational Green Readiness (POG), Perceived External Green Readiness (PEG), and the institutionalization of Green HRM (ING). Hypothesis 1 (H1) finds strong support with a path from POG to the initial adoption of Green HRM (IAG), indicated by an original sample value of 0.348. This finding, aligning with AlZgool [46], suggests a direct correlation between an organization’s preparedness for Green HRM and its likelihood of adopting such practices. The effect size of 0.121 and an R2 value of 0.776, coupled with a predictive relevance (Q2) of 0.769, further emphasize the robustness of this relationship. Studies by AnuSingh [47] and Hameed [48] also corroborate the positive impact of Green HRM on environmental and employee performance, including job performance and motivation, as highlighted by Aboramadan [49] and Zaki [50].

Hypothesis 2 (H2) also receives affirmation, displaying a positive trajectory from PEG to IAG, with an original sample value of 0.559. This underscores the influential role of external factors, such as market dynamics and government initiatives, in the initial adoption of Green HRM, resonating with findings from Ojo [55] and Jamal [14]. An effect size of 0.311 signifies the substantial impact of PEG on IAG, consistent with sector-specific observations by Yusoff [56] and Aboramadan [98], indicating that PEG crucially drives the institutionalization of Green HRM.

Support for Hypothesis 3 (H3) is evidenced by an original sample value of 0.418, indicating that IAG significantly influences the institutionalization of Green HRM. This result suggests that initial adoption plays a key role in integrating Green HRM into an organization’s operations, a sentiment echoed by AlZgool [46] and Yusoff [58] in their findings on the positive relationship between Green HRM and individual green values. The mediating role of green work engagement and the moderating effects identified by Aboramadan [98] and O’Donohue [59] further substantiate the importance of this initial phase in the broader institutionalization process.

Conversely, Hypotheses 4 and 5, focusing on the direct effects of POG and PEG on ING, did not find support in the data. The results for POG -> ING (beta = 0.182, T = 1.723, p = 0.085) and PEG -> ING (beta = 0.062, T = 0.736, p = 0.462) suggest that while these factors are integral in the initial phases of Green HRM adoption, they do not directly lead to its deeper institutionalization, indicating the need for further exploration of mediating factors or a more complex network of influences.

Hypothesis 6 presents a novel perspective, proposing a moderating effect of CSR on the progression from IAG to ING. This study finds empirical support for this hypothesis, with a negative coefficient (beta = −0.084, T = 3.747, p = 0.000), suggesting a nuanced role of CSR in this process. Despite CSR initiatives typically being perceived as supportive of institutionalization, they may also complicate or weaken the relationship, potentially due to conflicting organizational priorities or challenges in integrating CSR with Green HRM practices.

This body of findings contributes to the scholarly dialogue on the multifaceted effects of Green HRM. Chen [61] underscores the positive influence of perceived Green HRM on diverse workplace outcomes, mediated by organizational identification. The significant beta values in this study reinforce the predictive relationship between Green HRM and individual values, as highlighted by AlZgool [46]. Moreover, the literature supports the notion that specific Green HRM practices championed by leadership significantly affect environmental performance and organizational citizenship behavior, as shown by AnuSingh [47] and Hameed [48]. These practices are foundational to the institutionalization of Green HRM, fostering a sustainable organizational culture.

This research on Green Human Resource Management (Green HRM) within Malaysian SMEs offers insightful evidence, particularly on the mediating role of the initial adoption of Green HRM (IAG). This study robustly supports Hypothesis 7 (H7) and Hypothesis 8 (H8), highlighting the integral role of initial adoption in mediating the relationship between Perceived Organizational Green Readiness (POG) and Perceived External Green Readiness (PEG) with the institutionalization of Green HRM (ING). The path coefficient of 0.146 for POG (T statistics = 3.823, p-value = 0.000) and 0.234 for PEG (T statistics = 4.056, p-value = 0.000) reinforces the pivotal position of initial adoption in bridging the gap between readiness and institutionalization.

The findings resonate with existing literature in the field of Green HRM. Zaki [50] emphasizes the positive influence of perceived Green HRM on workplace outcomes, highlighting the role of organizational identification in mediating these impacts. This perspective is supplemented by Pinzone [10] and Guerci [33], who demonstrate how Green HRM facilitates collective engagement in environmental protection and translates stakeholder pressures into enhanced environmental performance. Furthermore, the significance of strategic HR competencies and ethical leadership in adopting Green HRM practices, as highlighted by Yong [9] and Islam [52], underscores the necessity for fostering a green organizational culture conducive to environmental performance.

The model’s predictive relevance is affirmed by high Q2 predict values for ING (0.769 and 0.686 for the effect of IAG), indicating its strong predictive capabilities. This study elucidates that both perceived organizational and external readiness significantly influence the initial adoption of Green HRM, which is instrumental in its institutionalization. The moderation analysis reveals a nuanced interaction where CSR activities may slightly dampen the strength of the relationship between initial adoption and institutionalization, underlining the intricate role of CSR within the Green HRM process.

This research presents a detailed pathway through which Green HRM is adopted and becomes entrenched within the structures of Malaysian SMEs. It offers essential insights for practitioners and policymakers focused on nurturing sustainable practices within organizations, highlighting the critical stages of initial adoption and the influential role of CSR in the institutionalization process.

7. Implication of This Study

7.1. Theoretical Implications

The theoretical implications of this study on Green Human Resource Management (Green HRM) within Malaysian SMEs are multifaceted and grounded in established theoretical frameworks, including stakeholder theory, the E-Commerce Adoption Model, the Organizational Readiness for Change (ORC) framework, environmental determinism, and CSR theory.

Stakeholder theory posits that organizations must consider the interests and influences of a wide range of stakeholders in their decision-making processes. The findings of this study, particularly the supported hypotheses indicating the importance of Perceived Organizational Green Readiness (POG) and Perceived External Green Readiness (PEG) in the adoption of Green HRM, resonate with Stakeholder theory. The significant mediated relationships through the initial adoption of Green HRM (IAG) to the institutionalization of Green HRM (ING) underscore the need for organizations to align their Green HRM practices not only with internal stakeholder expectations but also external pressures and incentives.

The E-Commerce Adoption Model emphasizes the dual significance of organizational and external readiness in the adoption of innovations. This study’s findings enhance this model by demonstrating the parallel within the context of Green HRM, where both POG and PEG are shown to be predictive of IAG. The model is further supported by the non-significant direct paths from POG and PEG to ING, suggesting that readiness does not automatically translate into institutionalization without the mediating step of initial adoption.

The ORC framework focuses on Change Commitment and Change Efficacy. This study’s results highlight the relevance of this framework to Green HRM by showing how organizational commitment to green practices (as part of POG) is essential for the initial adoption of Green HRM. However, the framework could be extended to consider the intricacies revealed by the moderating effects of CSR on the relationship between IAG and ING.

Environmental determinism suggests that external factors, such as market forces and regulatory pressures, significantly influence organizational practices. This theory is exemplified in this study’s findings where PEG (comprising market forces and sustainability initiatives) influences the initial adoption of Green HRM. However, the direct impact of these external factors on the institutionalization process was not supported, hinting at a more complex interaction than traditional environmental determinism might suggest.

CSR theory advocates for the extension of organizational responsibilities to include ethical and environmental considerations. In line with CSR theory, this study found that CSR initiatives have a moderating effect on the institutionalization of Green HRM, reflecting the nuanced role that CSR plays in this process. Although CSR typically supports the institutionalization of Green HRM, its complex interaction with the adoption process highlights the multifaceted challenges organizations face in integrating CSR with operational practices.

In summary, this study contributes to the theoretical understanding of Green HRM by applying and extending several foundational theories. It reinforces the importance of stakeholder alignment, readiness for change, the influence of external factors, and the role of CSR in the adoption and institutionalization of Green HRM practices. These theoretical insights provide a scaffold for future research to explore the complexities of implementing sustainable practices within organizational structures, particularly in the evolving context of Malaysian SMEs and beyond.

7.2. Practical Implications

The findings from this study on Green Human Resource Management (Green HRM) in Malaysian SMEs present valuable practical insights for managers and organizational leaders aiming to improve their sustainability practices. These implications form a cohesive approach to implementing and institutionalizing Green HRM.

Organizations should incorporate Green HRM into their strategic planning, aligning sustainability initiatives with broader organizational goals. This alignment is crucial, as this study found a significant impact of Perceived Organizational Green Readiness (POG) on the initial adoption of Green HRM (IAG). This strategic integration ensures that green practices are not isolated efforts but part of the company’s core objectives.

Engaging stakeholders effectively is also key, aligning with stakeholder theory’s emphasis on aligning Green HRM practices with stakeholder expectations. Managers need to actively engage with employees, customers, suppliers, and the broader community to understand their environmental expectations, garnering support for green initiatives.

Assessing the organization’s readiness for change is another vital step. Evaluating both the commitment to and efficacy of change processes is essential in identifying potential barriers to adopting and institutionalizing Green HRM practices. This assessment helps in planning effective implementation strategies.

Capitalizing on external market dynamics and government sustainability initiatives is crucial, as Perceived External Green Readiness (PEG) significantly predicts IAG. Managers should stay informed about environmental regulations and market trends to leverage these to enhance Green HRM practices.

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) plays a moderating role in the relationship between the initial adoption and institutionalization of Green HRM. Managers should align CSR initiatives with Green HRM practices, considering the complexities that CSR might introduce into the adoption process.

Involving employees in the early stages of adopting green practices is essential, as is implementing training and development programs to enhance their green competencies. This involvement fosters a culture of sustainability and ensures that employees are equipped to participate in and support green initiatives.

Monitoring the performance of Green HRM practices and providing feedback for continuous improvement are also critical. Establishing metrics and monitoring systems allows for the measurement of Green HRM performance and guides ongoing refinement.

This study also underscores the need for the long-term integration of Green HRM practices. The direct relationship between POG and PEG with ING might not be significant, suggesting that adoption alone does not guarantee institutionalization. A focus on long-term integration into all organizational processes ensures that these practices become embedded in the organizational culture.

Lastly, the influence of strategic HR competencies and ethical leadership in adopting Green HRM practices cannot be understated. Managers and leaders should demonstrate ethical behavior and champion green initiatives, setting a precedent within the organization.

In summary, the practical implications drawn from this study provide a comprehensive framework for managers and organizational leaders to effectively implement and sustain Green HRM practices. By strategically aligning these practices with organizational objectives, engaging with stakeholders, leveraging external forces, and ensuring their long-term integration into the organizational culture, companies can enhance their sustainability efforts and achieve broader environmental and social goals.

8. Limitations of This Study

This study on Green Human Resource Management (Green HRM) in Malaysian SMEs offers valuable insights but also presents certain limitations that highlight areas for further research. One of the key limitations is its geographical scope, which is confined to Malaysian SMEs. This focus limits the generalizability of the findings to other regions and countries, where cultural, economic, and regulatory contexts might differ significantly. Therefore, expanding future research to include diverse geographical areas could provide a more comprehensive understanding of Green HRM practices globally. Another limitation stems from this study’s cross-sectional design, which captures data at a single point in time. This approach restricts the ability to establish causality and observe the evolution of Green HRM practices and their impacts over time. Longitudinal studies could offer more profound insights into the dynamic nature of Green HRM adoption and its long-term effects.

The reliance on self-reported data is another constraint, potentially leading to biases, like social desirability or response bias. Incorporating more objective measures or evaluations from third parties could enhance the validity and reliability of future research findings. This study’s focus on specific variables, such as organizational readiness and CSR, while informative, leaves out other potential influencers of Green HRM. Including additional variables like technological capabilities, market competitiveness, or different leadership styles in future research could provide a more holistic view of the factors influencing Green HRM implementation.

Moreover, this study’s quantitative approach, though effective in measuring general trends and relationships, may not capture the nuanced, qualitative aspects of implementing Green HRM. Qualitative research methods could reveal richer and more detailed insights into the experiences and attitudes of organizations toward Green HRM. The concentration on SMEs, while offering targeted insights, may not fully represent the experiences and challenges faced by larger organizations or multinational corporations in implementing Green HRM. Exploring Green HRM in a variety of organizational sizes and structures could yield a more diversified understanding of its application and effectiveness. Additionally, the research did not delve deeply into industry-specific challenges and opportunities related to Green HRM. Tailoring future studies to focus on specific sectors could uncover unique dynamics in Green HRM implementation and allow for the development of sector-specific strategies.

Lastly, while this study examined CSR’s role as a moderating variable in Green HRM, the complexities of this relationship might warrant a more detailed exploration. Future research could dissect different aspects of CSR and examine how they interact with other organizational variables in the context of Green HRM. While this study contributes significantly to the understanding of Green HRM in Malaysian SMEs, addressing these limitations in future research could further enrich the field, offering broader and deeper insights into the effective implementation and impact of Green HRM across different organizational contexts and regions.

9. Conclusions and Future Directions

This study on Green Human Resource Management (Green HRM) in Malaysian SMEs offers significant insights, contributing to the understanding of how internal and external factors influence the adoption and institutionalization of sustainable practices within organizations. The research underscores the critical role of Perceived Organizational Green Readiness (POG) and Perceived External Green Readiness (PEG) in fostering the initial adoption of Green HRM while highlighting the complexities introduced by corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives in the transition from adoption to institutionalization. These findings offer a nuanced understanding of the multifaceted nature of Green HRM and its integration within the fabric of an organization.

This study’s conclusion reaffirms the importance of aligning Green HRM with strategic planning and stakeholder expectations. It emphasizes the need for organizations to assess and enhance their readiness for change and to leverage external market forces and government initiatives. The moderating role of CSR and the importance of employee involvement, training, and ethical leadership are also underscored as pivotal in embedding Green HRM practices into the organizational culture.

Looking to the future, several directions for further research emerge. First, exploring the specific mediating variables between organizational and external readiness and the institutionalization of Green HRM could offer deeper insights. Understanding these mediators can help develop more targeted strategies for implementing Green HRM practices effectively.

Second, examining the impact of different industry sectors on the adoption and institutionalization of Green HRM would provide valuable sector-specific insights. Different industries face unique environmental challenges and pressures, and research in this area could lead to more tailored Green HRM strategies that address these specific needs.

Third, investigating the long-term impacts of Green HRM on organizational performance, including financial, environmental, and social outcomes, would be beneficial. This would provide a clearer understanding of the return on investment for Green HRM initiatives, supporting the business case for sustainability.

Additionally, cross-cultural studies could offer a comparative perspective on the adoption and effectiveness of Green HRM practices in different cultural contexts. Such studies could reveal how cultural norms and values influence the implementation and success of Green HRM initiatives.

Lastly, the evolving nature of CSR and its interplay with Green HRM is an area ripe for further exploration. Understanding how CSR strategies evolve in response to changing societal expectations and how they interact with Green HRM practices would provide valuable insights for both academics and practitioners.

In conclusion, this study contributes to the burgeoning field of Green HRM, offering theoretical and practical insights that enhance our understanding of the complexities involved in adopting and institutionalizing sustainable practices in organizations. The proposed future research directions aim to build on these foundations, exploring new avenues to advance the field of Green HRM and support organizations in their journey toward sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Z.; data curation, Z.K.M.M.; formal analysis, W.Z. and S.S.A.; investigation, S.S.A.; methodology, S.S.A.; project administration, Z.K.M.M.; resources, W.Z.; software, Z.K.M.M.; supervision, W.Z. and S.S.A.; validation, W.Z. and S.S.A.; writing—original draft, W.Z. and S.S.A.; writing—review and editing, W.Z., Z.K.M.M., and S.S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

This study was conducted as per the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The research questionnaire was anonymous, and no personal information was gathered. Oral consent was obtained from all individuals involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Graduate School of Business, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia and Prince Sultan University for their support in conducting this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, R.; Yue, Z.; Ijaz, A.; Lutfi, A.; Mao, J. Sustainable Business Performance: Examining the Role of Green HRM Practices, Green Innovation and Responsible Leadership through the Lens of Pro-Environmental Behavior. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GGI Insights Global Sustainability: Lasting Impact Through Scalable Action. Available online: https://www.graygroupintl.com/blog/global-sustainability (accessed on 26 December 2023).

- Renwick, D.W.S.; Redman, T.; Maguire, S. Green Human Resource Management: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y.-K.; Khan, T.I.; Islam, S.U.; Abdullah, F.Z.; Pradana, M.; Kaewsaeng-on, R. Impact of Green HRM Practices on Environmental Performance: The Mediating Role of Green Innovation. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 916723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, S.E.; Renwick, D.W.S.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Muller-Camen, M. State-of-the-Art and Future Directions for Green Human Resource Management: Introduction to the Special Issue. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. Z. Pers. 2011, 25, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papademetriou, C.; Ragazou, K.; Garefalakis, A.; Passas, I. Green Human Resource Management: Mapping the Research Trends for Sustainable and Agile Human Resources in SMEs. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gao, X.; Cao, Y.; Mushtaq, N.; Chen, J.; Wan, L. Catalytic Effect of Green Human Resource Practices on Sustainable Development Goals: Can Individual Values Moderate an Empirical Validation in a Developing Economy? Sustainability 2022, 14, 14502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoaib, M.; Abbas, Z.; Yousaf, M.; Zámečník, R.; Ahmed, J.; Saqib, S. The Role of GHRM Practices towards Organizational Commitment: A Mediation Analysis of Green Human Capital. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1870798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.Y.; Mohd-Yusoff, Y. Studying the Influence of Strategic Human Resource Competencies on the Adoption of Green Human Resource Management Practices. Ind. Commer. Train. 2016, 48, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinzone, M.; Guerci, M.; Lettieri, E.; Redman, T. Progressing in the Change Journey towards Sustainability in Healthcare: The Role of Green HRM. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 122, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerónimo, H.M.; Henriques, P.L.; de Lacerda, T.C.; da Silva, F.P.; Vieira, P.R. Going Green and Sustainable: The Influence of Green HR Practices on the Organizational Rationale for Sustainability. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 112, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, D. Green HRM: Management of People through Commitment towards Environmental Sustainability. Int. J. Res. Financ. Mark. 2015, 5, 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- Vij, P.; Mumbai, N. Green HRM- Delivering High Performance HR Systems. Int. J. Mark. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 4, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Jamal, T.; Zahid, M.; Martins, J.M.; Mata, M.N.; Rahman, H.U.; Mata, P.N. Perceived Green Human Resource Management Practices and Corporate Sustainability: Multigroup Analysis and Major Industries Perspectives. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, M.I.; Yusliza, M.Y.; Fawehinmi, O. Green HRM and Hospitality Industry: Challenges and Barriers in Adopting Environmentally Friendly Practices. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muisyo, P.K.; Qin, S. Enhancing the FIRMS Green Performance through Green HRM: The Moderating Role of Green Innovation Culture. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 289, 125720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulrajah, A.A.; Opatha, H.H.D.N.P.; Nawaratne, N.N.J. Green Human Resource Management Practices: A Review. Sri Lankan J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawangsari, L.C.; Sutawidjaya, A.H. How the Green Human Resources Management (GHRM) Process Can Be Adopted for the Organization Business? In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Economics, Business, Entrepreneurship, and Finance (ICEBEF 2018), Bandung, Indonesia, 19 September 2018; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nejati, M.; Rabiei, S.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J. Envisioning the Invisible: Understanding the Synergy between Green Human Resource Management and Green Supply Chain Management in Manufacturing Firms in Iran in Light of the Moderating Effect of Employees’ Resistance to Change. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiku, S.O. Institutionalizing Social Responsibility Through Workplace Green Behavior. In Contemporary Multicultural Orientations and Practices for Global Leadership; IGI Global: Pennsylvania, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 183–199. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, W.; Najmi, A.; Arif, M.; Younus, M. Exploring Firm Performance by Institutional Pressures Driven Green Supply Chain Management Practices. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2019, 8, 415–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, M.T.; Freeman, J. Structural Inertia and Organizational Change. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1984, 49, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.; Wright, M.; Ketchen, D.J. The Resource-Based View of the Firm: Ten Years after 1991. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. Oststeinbek: SmartPLS GmbH. Available online: http://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 16 December 2023).

- Hameed, R.; Mahmood, A.; Shoaib, M. The Role of Green Human Resource Practices in Fostering Green Corporate Social Responsibility. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 792343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. Higher-Order Models, SmartPLS 4. Available online: https://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Dijkstra, T.; Henseler, J. Consistent Partial Least Squares Path Modeling. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragazou, K.; Garefalakis, A.; Papademetriou, C.; Passas, I. Well-Being Human Resource Model In The Collaborative Economy: The Keystone of ESG Strategy In The Tourism Sector. Int. Conf. Tour. Res. 2023, 6, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L. Green Human Resource Management and Green Supply Chain Management: Linking Two Emerging Agendas. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1824–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercantan, O.; Eyupoglu, S. How Do Green Human Resource Management Practices Encourage Employees to Engage in Green Behavior? Perceptions of University Students as Prospective Employees. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, P.; Lenka, U.; Sahoo, D.K. Proposing Micro-Macro HRM Strategies to Overcome Challenges of Workforce Diversity and Deviance in ASEAN. J. Manag. Dev. 2018, 37, 6–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerci, M.; Longoni, A.; Luzzini, D. Translating Stakeholder Pressures into Environmental Performance—The Mediating Role of Green HRM Practices. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 27, 262–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortetmäki, T.; Heikkinen, A.; Jokinen, A. Particularizing Nonhuman Nature in Stakeholder Theory: The Recognition Approach. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 185, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.; Freeman, R.E.; Cavalcanti Sá de Abreu, M. Stakeholder Theory As an Ethical Approach to Effective Management: Applying the Theory to Multiple Contexts. Rev. Bus. Manag. 2015, 17, 858–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla, A.; Licker, P.S. ECommerce Adoption in Developing Countries: A Model and Instrument. Inf. Manag. 2005, 42, 877–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ardura, I.; Meseguer-Artola, A. What Leads People to Keep on E-Learning? An Empirical Analysis of Users’ Experiences and Their Effects on Continuance Intention. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2016, 24, 1030–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.S.; Ahmed, S.; Kokash, H.A. Interplay of Perceived Organizational and External E-Readiness in the Adoption and Integration of Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality Technologies in Malaysian Higher Education Institutions. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B.J. A Theory of Organizational Readiness for Change. Implement. Sci. 2009, 4, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardinal, L.B.; Kreutzer, M.; Miller, C.C. An Aspirational View of Organizational Control Research: Re-Invigorating Empirical Work to Better Meet the Challenges of 21st Century Organizations. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 559–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, W.E.K.; Greener, J.M.; Simpson, D.D. Assessing Organizational Readiness for Change. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2002, 22, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piotrowska-Bożek, W. Organizational Readiness for Change: Toward Understanding Its Nature and Dimensions. Zesz. Nauk. Wyższej Szkoły Humanit. Zarządzanie 2019, 20, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, D.N. Changing Climate, Human Evolution, and the Revival of Environmental Determinism. Bull. Hist. Med. 2012, 86, 564–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babiak, K.; Trendafilova, S. CSR and Environmental Responsibility: Motives and Pressures to Adopt Green Management Practices. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2011, 18, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errida, A.; Lotfi, B. The Determinants of Organizational Change Management Success: Literature Review and Case Study. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2021, 13, 184797902110162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlZgool, M.R.H. Nexus between Green HRM and Green Management towards Fostering Green Values. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2019, 9, 2073–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AnuSingh, L.; Shikha, G. Impact of Green Human Resource Factors on Environmental Performance in Manufacturing Companies: An Empirical Evidence. Int. J. Eng. Manag. Sci. 2015, 6, 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hameed, Z.; Khan, I.U.; Islam, T.; Sheikh, Z.; Naeem, R.M. Do Green HRM Practices Influence Employees’ Environmental Performance? Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 41, 1061–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboramadan, M.; Karatepe, O.M. Green Human Resource Management, Perceived Green Organizational Support and Their Effects on Hotel Employees Behavioral Outcomes. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 3199–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, N.A.B.M.; Norazman, I. The Relationship between Employee Motivation towards Green HRM Mediates by Green Employee Empowerment: A Systematic Review and Conceptual Analysis. J. Res. Psychol. 2019, 1, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscoe, S.; Subramanian, N.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Chong, T. Green Human Resource Management and the Enablers of Green Organisational Culture: Enhancing a Firm’s Environmental Performance for Sustainable Development. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Khan, M.M.; Ahmed, I.; Mahmood, K. Promoting In-Role and Extra-Role Green Behavior through Ethical Leadership: Mediating Role of Green HRM and Moderating Role of Individual Green Values. Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 42, 1102–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khor, K.-S.; Thurasamy, R.; Ahmad, N.H.; Halim, H.A.; May-Chiun, L. Bridging the Gap of Green IT/IS and Sustainable Consumption. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2015, 16, 571–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indrawati, H.; Caska, C.; Hermita, N.; Sumarno, S.; Syahza, A. Green Innovation Adoption of SMEs in Indonesia: What Factors Determine It? Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2023, 5, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, A.O.; Tan, C.N.-L.; Alias, M. Linking Green HRM Practices to Environmental Performance through Pro-Environment Behaviour in the Information Technology Sector. Soc. Responsib. J. 2020, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, Y.M.; Nejati, M.; Kee, D.M.H.; Amran, A. Linking Green Human Resource Management Practices to Environmental Performance in Hotel Industry. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2018, 21, 663–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Geertshuis, S.; Grainger, R. Understanding Academics’ Adoption of Learning Technologies: A Systematic Review. Comput. Educ. 2020, 151, 103857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, Y.M.; Ramayah, T.; Othman, N.-Z. Why Examining Adoption Factors, HR Role and Attitude towards Using E-HRM Is the Start-Off in Determining the Successfulness of Green HRM? J. Adv. Manag. Sci. 2015, 3, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donohue, W.; Torugsa, N. The Moderating Effect of Green HRM on the Association between Proactive Environmental Management and Financial Performance in Small Firms. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 27, 239–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Dumont, J.; Deng, X. Employees’ Perceptions of Green HRM and Non-Green Employee Work Outcomes: The Social Identity and Stakeholder Perspectives. Group. Organ. Manag. 2018, 43, 594–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Jiang, W.; Li, X.; Gao, H. Effect of Employees Perceived Green HRM on Their Workplace Green Behaviors in Oil and Mining Industries: Based on Cognitive-Affective System Theory. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, J.; Morgan, D. An Empirical Study of Green Workplace Behaviours: Ability, Motivation and Opportunity. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2017, 56, 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.A.; Khan, K.A. Impact of Green Human Resource Practices on Hotel Environmental Performance: The Moderating Effect of Environmental Knowledge and Individual Green Values. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 2154–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusliza, M.-Y.; Norazmi, N.A.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Fernando, Y.; Fawehinmi, O.; Seles, B.M.R.P. Top Management Commitment, Corporate Social Responsibility and Green Human Resource Management. Benchmarking Int. J. 2019, 26, 2051–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, S.; Javed, F. The Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility toward Green Human Resource Management: The Mediating Role of Sustainable Environment. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2017, 4, 1310012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusliza, M.-Y.; Othman, N.Z.; Jabbour, C.J.C. Deciphering the Implementation of Green Human Resource Management in an Emerging Economy. J. Manag. Dev. 2017, 36, 1230–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azungah, T. Qualitative Research: Deductive and Inductive Approaches to Data Analysis. Qual. Res. J. 2018, 18, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, C. Quantitative, Cross-Sectional Survey Utilising the Corporate Entrepreneurship Assessment Instrument (CEAI) to Describe Middle Managers’ Perceptions of a South African Firm’s Internal Environment in 2018. Ph.D. Thesis, The IIE, Sandton, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.; Chowdhury, B.; Khalil, I.; Haque, R.; bin Senathirajah, A.R. Analyzing Key Factors Affecting Sales Performance Amongst Malaysian Smes: A Structural Path Modeling Approach. Int. J. eBus. Egov. Stud. 2022, 14, 560–577. [Google Scholar]

- Galloway, A. Non-Probability Sampling. In Encyclopedia of Social Measurement; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 859–864. [Google Scholar]

- White, T.B.; Zahay, D.L.; Thorbjørnsen, H.; Shavitt, S. Getting Too Personal: Reactance to Highly Personalized Email Solicitations. Mark. Lett. 2007, 19, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.S.; Overton, T.S. Estimating Nonresponse Bias in Mail Surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenakis, A.A.; Harris, S.G.; Mossholder, K.W. Creating Readiness for Organizational Change. Hum. Relat. 1993, 46, 681–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotter, J.P. Leading Change; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, D.; Armenakis, A.; Harris, S.; Feild, H. Toward a Comprehensive Definition of Readiness for Change: A Review of Research and Instrumentation. Res. Organ. Chang. Dev. 2007, 16, 289–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]