Abstract

Balancing food production and biodiversity conservation is a big challenge around the world. Eco-friendly agriculture has the potential to overcome these challenges and achieve sustainability. Although some studies show the high valuation of flagship species (e.g., attractive birds and fish) in paddy land where eco-friendly rice is cultivated, limited research has been performed concerning non-specific species such as generalists inhabiting rice paddies that also contribute to agro-biodiversity and ecosystem services. Therefore, this study assesses the valuation of non-flagship vertebrates and invertebrates by applying a choice experiment to vertebrate- and invertebrate-friendly rice. To understand the spatial/regional heterogeneity of the valuation, a questionnaire survey was distributed to both urban and rural citizens in Japan. Our results demonstrated that almost all respondents expressed a desire to protect both vertebrates and invertebrates, with more appreciation for vertebrates than for invertebrates. The analysis also found regional heterogeneity between urban and rural areas in terms of vertebrate and invertebrate evaluations and purchasing intentions. Our findings indicate marketing potential in Japan to promote eco-friendly rice production in relation to vertebrate and invertebrate conservation.

1. Introduction

As individuals become more aware of the impact of their consumption behavior on the environment [1], there is growing interest in purchasing eco-friendly agricultural products. Consuming eco-friendly food and products not only benefits their health, but also supports ecological and environmental sustainability [2]. Consequently, in response to concerns over food security and environmental contamination, farmers in Japan have begun producing eco-friendly rice, as rice is the dominant food crop in the country [3]. Eco-friendly rice cultivation reduces the use of chemical pesticides, herbicides, and fertilizers, significantly contributing to ecological balance and biodiversity maintenance [4]. Eco-friendly rice is typically sold with an eco-label indicating it meets prescribed ecological sustainability standards [5]. Globally, eco-labeling schemes are widely used in numerous products to deliver pro-environmental information to consumers [6]. Eco-labeling has shown remarkable effects in supporting biodiversity [7] and promoting green consumption. Price premiums obtained from consumers for these eco-labeled products provide a primary impetus for farmers to adopt sustainable agricultural practices [8,9].

Several previous studies have primarily focused on the value of eco-labeled rice in protecting flagship species, such as “bittern-friendly” rice in Australia [10] and rice that protects crested ibis in Japan [11]. These flagship species-friendly rice have shown great value in preventing the extinction of endangered species and food safety. However, evidence of these flagship species is not always apparent in all paddy fields. Instead, vertebrates (e.g., frogs and fishes) and invertebrates, such as insects [12], are known to inhabit rice paddies and play a crucial but largely overlooked role in biodiversity conservation. Nevertheless, limited research was found in the existing databases to assess the value of these non-flagship species.

To fill this gap, this study mainly attempted to understand consumers’ evaluation of vertebrates and invertebrates by estimating consumers’ willingness to pay for vertebrate- and invertebrate-friendly rice. We conducted a questionnaire survey, applying a discrete choice experiment with a hypothetical scenario concerning vertebrate and invertebrate protection. Additionally, we selected Sendai and Furukawa, representing the urban and rural areas in Japan, respectively, to understand whether regional heterogeneity exists, as well as to determine whether frequent interactions with nature impact individuals’ evaluation of vertebrates and invertebrates.

To gain a better insight into an individual’s consumption behaviors, this study combined nudge theory with hypothetical vertebrate and invertebrate protection scenarios in our choice experiment. Nudge theory illustrates that individual behavioral changes can be induced by slight pushes from other individuals [13]. Nudges influence people’s choices or actions without restricting freedom of choice or enforcing rules and regulations [14]. The nudge approach has shown the potential to increase healthy choices in adults [15,16] and promote pro-environmental behavioral changes via several methods (e.g., shape or image change, energy-saving labeling, and placing environmental cues) [17]. Likewise, a green nudging natural experiment emphasizing environmentally responsible features of products significantly shifted consumers toward green purchases [18]. Hence, this study also aimed to explore whether nudges can influence an individual’s pro-environmental consumption behaviors. Li et al. [19] uncovered the peer effect nudges individual’s behavior and improves their performance. In our survey, we introduced an attribute of “purchase willingness of individuals within their social circle” as indicators of the peer effect to assess the effect of the nudge approach.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The following two sections outline the survey design, sampling data, and methodology. Next, this study presents the results and discussion. Finally, we present our conclusions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Design

We applied a choice experiment, a frequently used method for determining individual preferences among items. With the choice experiment, respondents’ willingness to pay can be indirectly identified by analyzing trade-offs across attributes in a series of hypothetical scenarios [11].

Our survey questionnaire comprised five steps. The first step assessed individuals’ daily eating habits and food purchase intentions. The second step examined factors affecting rice purchasing decisions such as access, price, and key considerations. Step 3 focused on participants’ attitudes toward and perceptions of biodiversity. Step 4 presented a choice experiment set. Step 5 gathered participants’ sociodemographic characteristics, such as age, occupation, and income.

Regarding the question design in Step 4, we applied a novel method that has not been previously utilized in similar studies. Specifically, to capture a comprehensive picture of the biodiversity in rice paddies, we conducted a field survey of observing the species present in paddy fields in Osaki, Miyagi, in July 2019. Following the guidelines outlined in the Manual of Investigation and Evaluation of Biodiversity Indicators Useful for Agriculture, issued by the National Institute for Agro-Environmental Sciences, we identified and counted the number of species from the upper part of rice plants and the water under both conventional and eco-friendly cultivation practices. The results are presented in Supplementary Materials Section Figure S1.

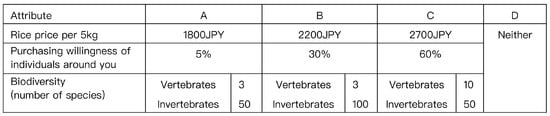

We applied a discrete choice experiment using an orthogonal array in Step 4 of our survey questionnaire. Our design was implemented by using AlgDesign package in R. The choice set comprised three alternatives, each characterized by three attributes: rice price (four levels—JPY 1800, JPY 2200, JPY 2700, and JPY 3200 per 5 kg, based on retail prices from rice stores in Japan), individuals’ purchasing willingness within their social circles (four levels—5%, 30%, 60%, and 90%), and the degree of biodiversity in the eco-friendly rice paddies, as depicted in Figure 1. We introduced the number of vertebrates and invertebrates that certain eco-rice host as key biodiversity indicators, the choice set of which is based on the findings presented in Figure S1. We classified amphibians we identified in rice paddies as vertebrates, and mollusks and arthropods as invertebrates. To assess their effects, two levels were assigned to the number of vertebrate species (3 and 10) and invertebrate species (50 and 100). Finally, we included a “no-purchase” option in each choice set to accommodate respondents who may choose not to make a purchase. To illustrate, in option A, the price of a certain eco-rice per 5 kg is JPY 1800, with 5% of people within the respondent’s social circle willing to purchase it, and this rice hosts 3 vertebrate species and 50 invertebrate species during its planting. If the respondent chooses none of options A, B, and C, he/she can choose option D. Each participant was asked to respond to nine choice sets.

Figure 1.

An example of a choice set.

2.2. Data Collection

Between January and March 2020, we conducted a questionnaire survey in Furukawa and Sendai, located in northeastern Japan. Furukawa was selected as a representative rural area, and Sendai was chosen as an urban area for comparative analysis. We randomly recruited residents from four areas of Furukawa and three areas from Sendai, with 3500 residents from each region, as our participants. We distributed our questionnaires by physical mail. Respondents returned their completed questionnaires in the envelope provided by us for free. We obtained 500 and 497 responses from Furukawa and Sendai, respectively (response rates were approximately 14.3% and 14.2%, respectively). Among those, we eliminated incomplete responses and responses for “I never cook, so I do not purchase rice” to avoid bias in our research. Finally, 323 valid samples from Furukawa and 350 from Sendai were included in our estimations.

3. Methodology

3.1. Factor Analysis

This study employed factor analysis as a statistical tool to analyze data collected from respondents regarding their eating habits and food purchasing behaviors. Factor analysis is commonly used to model the relationships among multiple observed variables in terms of one or more underlying latent constructs. It aims to reduce the number of observed variables to a smaller set of factors that can account for most of the variance in data. This technique is useful for identifying or understanding the latent constructs that may drive the patterns observed in data [20].

3.2. Conjoint Analysis

Conjoint analysis is used as a multivariate technique to understand how individuals evaluate the overall value of a product or service by combining separate amounts of utility for each attribute level [21]. To determine the importance of different attributes to respondents, the relationship between the different attribute utilities and rated responses must be specified. The conditional logit model is widely adopted for this purpose. We assume that respondent behavior can be represented by random utility models [22]. Following Yang et al. [23], the utility function of the conditional logit model is as follows:

where Vni represents the observable utility of respondent n’s choice of i, uni denotes the unobservable error term, xni is a vector comprising attributes for product i, and the coefficient ß of xni is used to describe individual differences in utility equal to Vni.

Under Equation (1), the consumer chooses option i over other choices in set j when uni maximizes the utility probability that respondent n selects i. C represents the set of all alternatives. The probability distribution function for consumer n to choose option i in a fixed scenario during an observation is as follows:

4. Results

4.1. Respondents’ Sociodemographic Characteristics

Table 1 presents the sociodemographic results of our valid samples from Furukawa and Sendai. In both regions, the number of women exceeds that of men. This gender distribution can be considered satisfactory because the target population of this study is rice consumers, with women exhibiting more frequent rice purchasing behaviors than men.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the sample.

Observing the sample distribution by age, most respondents from both regions are middle-aged, ranging between 30 and 60 years of age (50.46% in Furukawa and 61.15% in Sendai). Young respondents, aged 10 to 30 years of age, account for 9.6% in Furukawa and 9.71% in Sendai, and older persons over 60 years of age constitute 39.94% in Furukawa and 29.14% in Sendai. The ratio of age groups closely aligns with government statistics (Table 2).

Table 2.

Government statistics of the two regions in 2020.

Regarding annual family income demographics, respondents with an annual family income below JPY 5 million constituted around half of the total samples in both regions. These demographic details align with the data presented in Table 2, suggesting that our samples are representative. Additionally, we examined the average and median incomes across both regions and observed that incomes in Sendai are higher than those in Furukawa, indicating that the annual income of urban residents is higher than that of rural residents.

4.2. Consumers’ Preferences and Behaviors

The results regarding access to rice show that respondents in Sendai primarily purchase rice from supermarkets, while those in Furukawa obtain rice from relatives and friends, followed by supermarkets. This trend in Furukawa is owing to local practice where rice farmers in rural areas gift newly harvested rice to friends and relatives (hereafter referred to as “relationship rice”). Additionally, rice variety and place of origin are significant factors affecting consumers’ rice purchasing decisions. When examining preferred rice prices, respondents in Furukawa tend to favor prices below JPY 1600 per 5 kg, whereas respondents in Sendai prefer prices below JPY 2000 per 5 kg (Table 3).

Table 3.

Distribution of respondents’ preferences and behaviors when purchasing rice.

4.3. Factor Analysis Results

We used R software (Version 4.3.0) to perform factor analysis, and the scree plots are shown in Supplementary Material Section Figure S2. Based on Brown’s [24] guidelines, we identified four main factors. To improve the interpretation of the results, we applied promax rotations. Table 4 presents the factor loading results for Furukawa, as the results of Sendai are similar to those of Furukawa.

Table 4.

Rotated factor loadings and communalities (Furukawa).

Based on Mizuki’s [25] analysis, we designated Factor 1 as life-enjoying, Factor 2 as public well-being-driven, Factor 3 as price-driven, and Factor 4 as health and safety-driven. To better understand consumer preferences for eco-friendly rice, we conducted an interaction effects examination using a conjoint choice experiment. In this experiment, four factors were utilized as personal attributes and interacted with the biodiversity attribute (i.e., number of vertebrate species × price-driven factor).

4.4. Conjoint Choice Experiment Results

An alternative-specific constant was applied to our model; it was set to 1 if respondents chose to purchase eco-friendly rice and 0 if they did not. To better compare Sendai and Furukawa, we combined all samples and set Sendai = 1 as a variable in the conditional logit model. The results are shown in Table 5. Negative estimate of “price × Sendai” indicates respondents in Sendai tend to be price conscious compared with Furukawa. Additionally, the interaction coefficients of “vertebrates × Sendai” and “invertebrates × Sendai” are both positive, revealing urban residents have more protectiveness toward vertebrates and invertebrates than rural residents.

Table 5.

Interaction effect results of the conditional logit model (set “Sendai = 1”).

Table 6 presents the main effect results of the two regions. The coefficients of the two regions generally had the same sign. Consumers in both regions demonstrated a significant negative correlation between price and purchase willingness, indicating that higher prices lead to lower purchase willingness. The positive coefficient of vertebrates and invertebrates in the two regions shows both urban and rural respondents are willing to protect both vertebrates and invertebrates; however, their preference for protecting vertebrates is stronger.

Table 6.

Main effect results of the conditional logit model: Sendai and Furukawa.

Table 7 and Table 8 show the interaction effect results of Furukawa and Sendai, respectively. Several common findings can be reported. There is a negative correlation between the purchasing willingness of individuals around you and age, invertebrates and age in Furukawa, and vertebrates and age in Sendai. Additionally, there is a statistically positive correlation between vertebrates and paddy. However, discernible differences are observed between the two regions. The data for Furukawa reveal a negative estimation between rice prices and income, while, for Sendai, this correlation is positive.

Table 7.

Interaction effect results of the conditional logit model: Furukawa.

Table 8.

Interaction effect results of the conditional logit model: Sendai.

5. Discussion

This study explored individuals’ evaluations of vertebrates and invertebrates, a topic rarely addressed in previous studies. Our results indicate that most consumers place a high value on eco-rice, supporting vertebrate and invertebrate conservation in both urban and rural areas of Japan. We hope this research provides evidence for the potential applicability of vertebrate and invertebrate protection labels in eco-rice.

5.1. Consumers’ Evaluations of Vertebrates and Invertebrates

Our results show that most consumers are willing to pay a price premium for eco-rice that supports vertebrate and invertebrate protection, which aligns with the conclusions of Khai and Yabe [26] on crane-friendly rice. Eco-rice has received considerable attention for its role in conserving flagship species (e.g., ibis, oriental storks, and waterbirds) in Japan. However, not all rice paddies are home to these species; instead, they host a diverse array of vertebrates and invertebrates. Research on biodiversity protection is scarce but crucial. This study addresses this gap by highlighting the protection of vertebrates and invertebrates in eco-rice cultivation. Our results carry positive implications for policymakers, as promoting eco-rice, which supports vertebrate and invertebrate preservation, is commercially viable.

The results of the main effects (Table 6) show that the marginal willingness to pay (MWTP) for vertebrates in both regions is consistently higher than that for invertebrates, suggesting that consumers favor vertebrates. This is possibly because individuals may believe that vertebrates possess more aesthetic charm than invertebrates. Our findings are consistent with those of previous studies [27,28]. Colléony et al. [27] stated that snakes, bats, and spiders are viewed as ugly and fearful, receiving less support for protection. Knight [28] found that an animal’s level of charisma positively impacts individuals’ choices. Nevertheless, almost all respondents affirmed their willingness to protect both vertebrates and invertebrates.

5.2. Regional Differences between Sendai and Furukawa

Table 5 presents a negative correlation between price and Sendai, suggesting that urban consumers are more sensitive to high-priced products than rural consumers. This is unsurprising, as high living expenses in cities likely drive the pursuit of reasonably priced products. Moreover, the positive correlation of “price × income” in Sendai contrasts with the result for Furukawa (Table 7 and Table 8). This difference can be explained by income variations between the two regions. Our samples showed that the annual income of urban residents is higher than that of rural residents, and individuals with high salaries usually favor expensive products.

Although respondents in Sendai and Furukawa have shown an inclination to protect biodiversity, the positive estimation of Sendai and vertebrates and invertebrates in Table 5 indicates a stronger appreciation and willingness to protect these species. This inclination could stem from urban residents witnessing rapid urbanization and biomass destruction [29], prompting heightened conservation efforts.

5.3. Factors Influencing Consumers’ Purchase Intention

The MWTP of the purchasing willingness of individuals around you is positive, confirming our hypothesis that the nudge strategy effectively influences consumers’ pro-environmental purchasing behavior. This finding aligns with that of Grebitus et al. [30], who demonstrated that individuals can be nudged toward more desirable choices. As a novel ethical approach, nudging techniques can help shape individuals toward decisions that are healthier and more beneficial for both themselves and the environment [31]. It provides a fresh perspective for promoting the consumption of eco-friendly agricultural products.

Regarding the results of the interaction effect estimates (Table 7 and Table 8), some common statistical points emerge between the two cities. Notably, the negative interaction effect of “purchasing willingness of individuals around you × age” suggests that older persons may be less influenced by their social circles than younger people. This finding validates Steinberg and Cauffman’s [32] conclusion that younger individuals’ decision making is influenced more by emotions or social influences than older individuals.

Additionally, the negative estimation of “purchasing willingness of individuals around you × men” in Furukawa reveals that men may be less influenced by others’ consumption behaviors than women. Lin et al. [33] and Dittmar et al. [34] highlighted persistent gender differences in purchasing decision making. They proposed that men are more convenience-oriented and less motivated by social influences than women.

The negative correlation between the purchasing willingness of individuals around you and income in Sendai indicates that consumers with higher salaries have a comparatively lower propensity to be influenced by others. We surmise that this group of individuals tends to make purchasing judgments based on their outstanding knowledge and life experiences.

Our interaction results for Sendai show that the estimation of the purchasing willingness of individuals around you and factors driven by public well-being and health and safety are both positive. This suggests that individuals who prioritize public welfare and their health tend to be more influenced by others. This observation is also supported by Sorensen [35], who found that peer groups affect individuals’ health plan selection.

5.4. Factors Influencing Individuals’ Awareness of Biodiversity Protection

The positive estimation of “vertebrates × paddy” in both regions suggests that respondents who have lived near paddy fields tend to be more willing to protect vertebrates. Hosaka et al. [36] discovered that regular exposure to nature increases individuals’ willingness to coexist with various animals. Similarly, Dunn et al. [37] stated that individuals are more likely to conserve nature when they have direct experience in the natural world.

As expected, estimations of the relationship between income and vertebrates and invertebrates in Furukawa are positive. This suggests that individuals with higher incomes are more inclined to protect biodiversity, demonstrating a greater love and respect for nature. This is consistent with Shao et al. [38], who found that individual income levels positively affect environmental concerns. Several empirical studies have substantiated this viewpoint. Specifically, Batte et al. [39] and Xie et al. [40] indicated that individuals with higher disposable incomes in households are more willing to purchase green products aimed at environmental protection.

Additionally, we identified that the interaction terms “vertebrates × age” in Sendai and notably “invertebrates × age” in Furukawa are consistently negative, suggesting that older persons in both urban and rural areas exhibit a reduced willingness to support vertebrate and invertebrate protection. This is possibly because older persons express less interest in and affection for animals than younger individuals [41].

Notably, the correlation between the price-driven factor and vertebrates in Sendai is positive, suggesting that individuals who prioritize money still express a strong willingness to conserve vertebrates. This finding contrasts with Gorton et al.’s [42] discovery that price-sensitive consumers exhibit limited willingness to pay extra for animal welfare. Furthermore, our observation of a negative correlation between the price-driven factor and invertebrates in Furukawa further supports their conclusion. We attribute this variance to regional differences in residents’ annual incomes and pro-environmental awareness.

Remarkably, our findings indicate that the relations that health and safety-driven factors have with vertebrates and invertebrates in Furukawa and that public well-being-driven factors have with vertebrates in Sendai are consistently negative. We assume that individuals conscious of public welfare and their own health may harbor unfavorable attitudes toward increasing populations of vertebrates or invertebrates. This can be attributed to concerns over pollution and the destruction of crops and fields caused by the abundance of animals in rice paddies. Our results corroborate the findings of Yin et al. [43], which suggest that respondents who value human health are more likely to support the lethal management of mammals (which pose significant threats to human safety).

Interestingly, the correlation of the interaction term “invertebrates × men” in Sendai is positive, suggesting that men show an inclination to preserve invertebrates. This finding aligns with that of Hosaka et al. [36], who claimed that men hold more favorable attitudes toward wild animals, particularly unpopular species such as invertebrates.

6. Conclusions and Suggestions

This study developed a novel hypothetical scenario to examine how individuals evaluate vertebrates and invertebrates by assessing their willingness to pay premiums for eco-rice that supports vertebrate and invertebrate conservation. Our results reveal that consumers in both urban and rural areas of Japan affirm their willingness to protect both vertebrates and invertebrates, demonstrating a high valuation of vertebrate- and invertebrate-friendly eco-rice. Our finding carries important implications for encouraging rice farmers to adopt eco-friendly practices and for policymakers in promoting vertebrate- and invertebrate-friendly rice.

Furthermore, we observed regional heterogeneity in terms of vertebrate and invertebrate evaluations and purchasing intentions. Urban consumers expressed a greater willingness to protect vertebrates and invertebrates than rural consumers. We also found that personal attributes such as age, gender, income, and peer effect significantly influence an individual’s evaluations and their consuming decision making. Older persons exhibit less willingness to protect biodiversity than young individuals, while male respondents tend to show more interest in invertebrates than female respondents. This research also confirms that nudge theory influences individuals’ consumption behavior.

Greater emphasis should be placed on enhancing citizens’ awareness of biodiversity protection, particularly concerning invertebrates, which play a key yet often overlooked role in maintaining ecosystem balance. The government should promote environmental campaigns through mass media (radio, television, Internet, etc.), to disseminate biodiversity information to communities. Additionally, more environmental activities should be conducted for children in schools, as education proves effective in promoting pro-environmental behaviors [44].

However, our study is not free of limitations. Firstly, although this study identified consumers’ evaluation of non-flagship species through their price premium for eco-rice, the results should be interpreted with caution owing to potential variations in individuals’ attitudes, preferences, and consumption behaviors. In addition, although this study uncovered regional differences between Sendai and Furukawa, the study sites we chose are from northeastern Japan, which can probably not represent urban and rural areas of the entire Japan. Future studies can expand on this topic by focusing on other metropolitan regions, larger rural areas, and even other countries to investigate varying cultural contexts.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su16198281/s1, Figure S1: species identified in our samples; Figure S2: scree plot.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.K. and T.I.; methodology, Y.K. and T.I.; software, Y.K., Q.L. and T.I.; formal analysis, Q.L., Y.K. and T.I.; investigation, Y.K., Y.N. and M.T.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.L. and Y.K.; writing—review and editing, Q.L., X.Z. and T.I.; supervision, T.I.; project administration, T.I.; funding acquisition, Q.L. and T.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by JST SPRING (Grant Number JPMJSP2114) and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (Grant Number 22K05844).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were not requested for this study as it did not involve any invasive procedure or animal or human clinical trials. In accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and Article 59 of the Act on the Protection of Personal Information of Japan, all participants provided informed consent before participating in the study. The anonymity and confidentiality of the participants were guaranteed, and participation was completely voluntary.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the comments of colleagues and anonymous reviewers who helped in refining this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yamane Nagao was employed by the company KRC Co., Ltd. Miyuki Takahashi was employed by the company PricewaterhouseCoopers Japan LLC. The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Saut, M.; Saing, T. Factors affecting consumer purchase intention towards environmentally friendly products: A case of generation Z studying at universities in Phnom Penh. SN Bus. Econ. 2021, 1, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazanfari, S.; Firoozzare, A.; Covino, D.; Boccia, F.; Palmieri, N. Exploring Factors Influencing Consumers’ Willingness to Pay Healthy-Labeled Foods at a Premium Price. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Nanseki, T.; Chomei, Y.; Kuang, J. A review of smart agriculture and production practices in Japanese large-scale rice farming. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 103, 1609–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmerson, M.; Morales, M.B.; Oñate, J.J.; Batáry, P.; Berendse, F.; Liira, J.; Aavik, T.; Guerrero, I.; Bommarco, R.; Eggers, S.; et al. How agricultural intensification affects biodiversity and ecosystem services. Adv. Ecol. Res. 2016, 55, 43–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Zeng, Y.; Fong, Q.; Lone, T.; Liu, Y. Chinese consumers’ willingness to pay for green- and eco-labeled seafood. Food Control. 2012, 28, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufique, K.M.R.; Polonsky, M.J.; Vocino, A.; Siwar, C. Measuring consumer understanding and perception of eco-labelling: Item selection and scale validation. Int. J. Con. Stud. 2019, 43, 298–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayama, N.; Osada, Y.; Mashiko, M.; Baba, Y.G.; Tanaka, K.; Kusumoto, Y.; Okubo, S.; Ikeda, H.; Natuhara, Y. Organic farming and associated management practices benefit multiple wildlife taxa: A large-scale field study in rice paddy landscapes. J. Appl. Ecol. 2019, 56, 1970–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulart, F.F.; Carvalho-Ribeiro, S.C.; Soares-Filho, B. Farming-biodiversity segregation or integration? Revisiting Land Sparing versus Land sharing debate. J. Environ. Prot. 2016, 7, 1016–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, W.-C.; Yang, Y.-C.; Chen, Y.-J.; Chen, Y.-C. Estimating the Willingness to Pay for Eco-Labeled Products of Formosan Pangolin (Manis pentadactyla pentadactyla) Conservation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herring, M.W.; Garnett, S.T.; Zander, K.K. From boutique to mainstream: Upscaling wildlife-friendly farming through consumer premiums. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2022, 4, e12730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, K.; Akai, K.; Ujiie, K.; Shimmura, T.; Nishino, N. The impact of information on taste ranking and cultivation method on rice types that protect endangered birds in Japan: Non-hypothetical choice experiment with tasting. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 75, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehra, K.K.; MacMillan, D.C. Wildlife-friendly food requires a multi-stakeholder approach to deliver landscape-scale biodiversity conservation in the Satoyama landscape of Japan. J. Environ. Manage. 2021, 297, 113275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, M.; Tsubokura, M. Evaluating risk communication after the Fukushima disaster based on nudge theory. Asia Pac. J. Public Health. 2017, 29, 193S–200S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauslbauer, A.L.; Schade, J.; Drexler, C.E.; Petzoldt, T. Extending the theory of planned behavior to predict and nudge toward the subscription to a public transport ticket. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2022, 14, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arno, A.; Thomas, S. The efficacy of nudge theory strategies in influencing adult dietary behaviour: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, Y.H.; Cheng, T.Y.; Yoon, S.; Ho, L.Y.C.; Huang, C.W.; Chew, E.H.; Thumboo, J.; Østbye, T.; Low, L.L. A systematic review of nudge theories and strategies used to influence adult health behaviour and outcome in diabetes management. Diabetes Metab. 2020, 46, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, S.E.; Choong, W.W.; Low, S.T. Can “nudging” play a role to promote pro-environmental behaviour? Environ. Chall. 2012, 5, 10364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becchetti, L.; Salustri, F.; Scaramozzino, P. Nudging and corporate environmental responsibility: A natural field experiment. Food Policy 2020, 97, 101951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, G.; Wang, H. Peer effects in competitive environments: Field experiments on information provision and interventions. MIS Q. Forthcom. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandalos, D.L.; Finney, S.J. Factor analysis: Exploratory and confirmatory. In The Reviewer’s Guide to Quantitative Methods in the Social Sciences; Hancock, G.R., Stapleton, L.M., Mueller, R.O., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018; pp. 98–122. [Google Scholar]

- Popović, M.; Kuzmanović, M.; Savić, G. A comparative empirical study of analytic hierarchy process and conjoint analysis: Literature review. Decis. Mak. Appl. Manag. Eng. 2018, 1, 53–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyoi, S.; Fujino, M.; Kuriyama, K. Investigating spatially autocorrelated consumer preference for multiple eco-labels: Evidence from a choice experiment. Clean. Respons. Consum. 2022, 7, 100083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Fuyuki, K.; Minakshi, K. How Does Information Influence Consumers’ Purchase Decisions for Environmentally Friendly Farming Produce? Evidence from China and Japan Based on Choice Experiment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J. What is an eigenvalue? JALT Test. Eval. SIG Newsl. 2001, 5, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mizuki, A. Analysis of consumers’ diversified preferences towards environmentally friendly rice. Jpn J. Agric. Econ. 2016, 47, 1–14. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Khai, H.V.; Yabe, M. Consumer preferences for agricultural products considering the value of biodiversity conservation in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. J. Nat. Conserv. 2015, 25, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colléony, A.; Clayton, S.; Couvet, D.; Saint Jalme, M.; Prévot, A.C. Human preferences for species conservation: Animal charisma trumps endangered status. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 206, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, A.J.; AKnight, A.J. “Bats, snakes and spiders, oh my!” How aesthetic and negativistic attitudes, and other concepts predict support for species protection. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.I.; Kareiva, P.; Forman, R.T.T. The implications of current and future urbanization for global protected areas and biodiversity conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2008, 141, 1695–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grebitus, C.; Roscoe, R.D.; Van Loo, E.J.; Kula, I. Sustainable bottled water: How nudging and Internet search affect consumers’ choices. J. Cleaner Prod. 2020, 267, 121930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carina, J.S.; Robert, N.; Loreta, S. Nudge-Break the Handcuffs from Your Phone; Working Paper; ULBS: Sibiu, Romania, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, L.; Cauffman, E. Maturity of judgment in adolescence: Psychosocial factors in adolescent decision making. Law Hum. Behav. 1996, 20, 249–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Featherman, M.; Brooks, S.L.; Hajli, N. Exploring gender differences in online consumer purchase decision making: An online product presentation perspective. Inf. Syst. Front. 2019, 21, 1187–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmar, H.; Long, K.; Meek, R. Buying on the Internet: Gender differences in online and conventional buying motivations. Sex Roles. 2004, 50, 423–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, A.T. Social learning and health plan choice. RAND J. Econ. 2006, 37, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosaka, T.; Sugimoto, K.; Numata, S. Childhood experience of nature influences the willingness to coexist with biodiversity in cities. Palgrave Commun. 2017, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, R.R.; Gavin, M.C.; Sanchez, M.C.; Solomon, J.N. The pigeon paradox: Dependence of global conservation on urban nature. Conserv. Biol. 2006, 20, 1814–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Tian, Z.; Fan, M. Do the rich have stronger willingness to pay for environmental protection? New evidence from a survey in China. World Dev. 2018, 105, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batte, M.T.; Hooker, N.H.; Haab, T.C.; Beaverson, J. Putting their money where their mouths are: Consumer willingness to pay for multi-ingredient, processed organic food products. Food Policy 2007, 32, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Gao, Z.; Swisher, M.; Zhao, X. Consumers’ preferences for fresh broccolis: Interactive effects between country of origin and organic labels. Agric. Econ. 2016, 47, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosaka, T.; Sugimoto, K.; Numata, S. Effects of childhood experience with nature on tolerance of urban residents toward hornets and wild boars in Japan. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorton, M.; Yeh, C.H.; Chatzopoulou, E.; White, J.; Tocco, B.; Hubbard, C.; Hallam, F. Consumers’ willingness to pay for an animal welfare food label. Ecol. Econ. 2023, 209, 107852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Kamimura, Y.; Imoto, T. Public tolerance of lethal wildlife management in Japan: A best–worst scaling questionnaire analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujii, S. Environmental concern, attitude toward frugality, and ease of behavior as determinants of pro-environmental behavior intentions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).