Abstract

Innovation is a critical concept that warrants a comprehensive examination. This article aims to elucidate the role of innovation within the social and solidarity economy sector in Morocco. To achieve this, a survey was conducted to identify areas where innovation could be implemented, utilizing a sample of 285 companies. Subsequently, a proposal for an innovative tool was developed to address the identified challenges, specifically within the ceramic industry. The findings indicate that the predominant issue is the chipping of raw materials with a rate of 50%. Furthermore, the proposed tool facilitates the conservation of raw materials for future utilization and enhances the organization of the sector. This is exemplified by a case study involving the decoration of a 10 m2 area, which demonstrates a potential recovery of 10 red shapes, 80 black shapes, and 50 white shapes of raw material. Consequently, the implementation of this solution may lead to certain implications, particularly concerning behavioral and coordination challenges that the company must adeptly manage.

1. Introduction

Innovation is widely recognized as a critical driver of technological advancement and enhanced productivity. Empirical research conducted in various contexts, including Mexico [1], Turkey [2], and Eastern and Central Europe [3], has demonstrated that firms’ innovation activities, particularly expenditures on research and development (R&D), significantly contribute to productivity improvements [4].

In the context of the industrial age, the economic viability of the social and solidarity economy sector is constrained by limitations in production capacity and the quality of craftsmanship. Nonetheless, the social and solidarity economy sector continues to play a significant role in contemporary society. Modern consumers are drawn to traditional products not only for their practicality but also for the cultural memories they evoke from traditional civilizations. Many traditional products, which are commonly displayed and accessible in public spaces, often blur the distinctions between art and design [5].

It is evident that innovation continues to serve as both a strategy and a conceptual framework within the social and solidarity economy sector. Notably, there is a scarcity of research focused on enhancing small-scale enterprises, particularly within the context of the Moroccan social and solidarity economy. Consequently, this article aims to introduce innovation by proposing a novel solution that is currently absent in the sector. The implementation of innovation is anticipated to yield multiple advantages [6], as it has the potential to enhance productivity and overall performance within the sector [3,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Numerous studies corroborate the assertion that innovation and research and development (R&D) contribute to increased productivity, a phenomenon observed across various countries at both the firm and national levels [14,15,16,17,18].

In fact, businesses today find themselves in a fluctuating market. In terms of the introduction of tools and innovative ideas, we note that SMEs are distinguished by stability and stagnation [19]. Similarly, they differ from each other in terms of resources and constraints in terms of access to external [20,21,22,23].

It is important to acknowledge that small enterprises have a greater capacity to generate and eliminate job opportunities compared to larger corporations, particularly in the context of Morocco. The social and solidarity economy sector in Morocco, which primarily consists of small structures, serves as the second most significant sector in terms of job creation following agriculture. The occupations within this sector reflect the diverse cultural heritage of the country, encompassing traditions, customs, and cultural influences derived from various exchanges. Therefore, there is a pressing need to support and enhance this sector by implementing a range of innovative strategies that can enhance production efficiency, reduce costs and expenses, and elevate the quality of manufactured goods.

In this research endeavor, we will introduce a novel tool that is currently lacking in the realm of the social and solidarity economy. The tool is designed to address various challenges prevalent in this sector and facilitate the introduction of innovative practices by the use of technological techniques that are absent within the sector. Furthermore, we will assess the efficacy of this innovative tool by implementing it in two pilot companies and evaluating its impact on their operations.

This article introduces an applied research study based on a comprehensive review of the existing literature and raises and discusses the following research questions: (1) What is innovation? (2) What are its forms? (3) What are the main works that have enriched the literature on innovation? (4) How can we introduce innovation within the Moroccan social and solidarity economy sector? (5) What are the main problems that can be resolved within this sector through the use of innovation? (6) What solutions can be proposed to resolve these identified problems? (7) What recommendations can be made in terms of innovation to promote the sector?

The structure of this article is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a brief overview of the concept of innovation, as well as the main existing works within the literature relating to the concept. Section 3 describes the research methodology and the steps taken to introduce innovation within the Moroccan social and solidarity economy sector. In Section 4, we detect the major problems within the Moroccan social and solidarity economy sector and propose an innovative solution to resolve these problems. In Section 5, we conclude this work.

2. Literature Review

2.1. A Brief Overview of Innovation

Innovating in business refers to the introduction of new products (goods or services) into the market, the implementation of a new or improved process, the deployment of a new method for marketing or organization, etc. Any innovation is the application of a new idea that breaks with existing and competitive ideas in the face of competition [24]. A sustainable competitive advantage is generated by providing an original and effective response or solution to the needs and motivations of a group of customers identified in a market [25].

Likewise, innovation can be considered an organizational skill based on the introduction of a set of ideas that can be used to improve a product, a procedure, or a process to enhance organizational performance [26,27]. According to Oslo (2005) [28], innovation is considered the implementation of a product, the process of a marketing strategy, or a new upgraded organizational process [28].

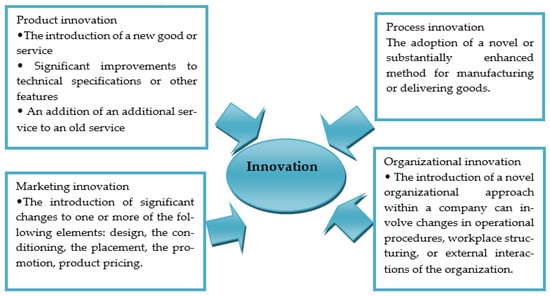

Note the existence of four types of innovation (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Forms of innovation.

Product innovation Involves the introduction of a new product or service to the market and presenting a multitude of [29,30]. Note that an innovation process relates to the definition, manufacturing, or delivery of a product, while also including a set of radical changes [31,32].

Additionally, there is organizational innovation, which highlights the changes that can be introduced in the methods and techniques used, namely, the organization of work and tasks assigned to staff within the company, as well as internal and external relationships between all stakeholders [33].

Adding to this, we consider the existence of a third type of innovation, marketing innovation, which corresponds to all the changes that can occur in the methods and tools used to market the final product. It should be noted that innovation is part of strategy and the economic model [34,35].

The last type of innovation is process innovation, which corresponds either to the implementation of a new manufacturing or production strategy, or to the improvement of an existing method to compensate for imperfections found during production.

According to the OECD, innovation can be found in different forms, as shown in the following figure.

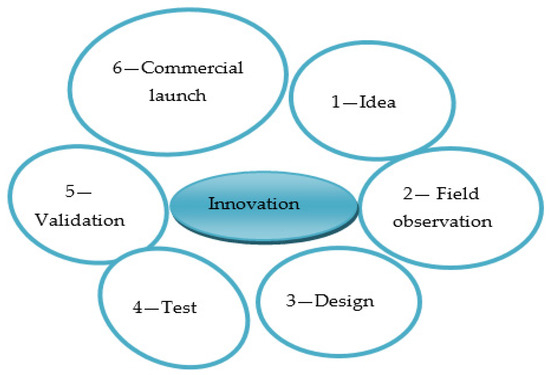

Likewise, throughout the life cycle of an innovative product, the innovation process goes through several stages, namely, the search for the idea, the construction and development of the concept, and ending with the commercial launch, as presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The innovation process.

It should be noted that innovation can have a lot advantages in terms of environmental trends. Hence, it can improve resource efficiency and encourage companies to choose strategies to minimize environmental risks, ensuring the birth of new innovation processes within the company [36,37].

Additionally, increasing and improving resource efficiency could lead to the search for new opportunities and innovative practices [38,39]. These practices can also be sought following the need to reduce a company’s participation in pollution [36,37,40]. It should be noted that recycling remains an important phase that challenges the notion of innovation through the use of creative means [41,42,43] to achieve the objectives of economy and energy [44,45]. It should be noted that the literature review assimilated the notion of innovation within companies to the promotion of environmental performance [46,47]. As a result, this type of innovation cannot be framed in the products resulting from innovation during design and production taking into consideration environmental constraints [37,42,48,49]. However, this approach comes from the introduction of new technologies of excess or vulnerable inputs [46].

In fact, adopting green methods could play a very profound role in achieving organizational success in terms of innovation [42]. Thus, directing a company’s strategy toward environmental innovation will make it possible to introduce measures aimed at minimizing the environmental impact of the company’s activity and promoting sustainability [50]. As a result, this type of innovation has advantages in terms of finding responses to market requirements at the social and legislative levels concerning the adoption of a set of practices and strategies giving priority to the environment while characterizing this constraint as a value within the company [51].

Stimulating innovative efficiency within companies and moving toward a green strategy are based on several factors, namely, the exchange of experiences and knowledge between staff of the same company [46,49], taking charge of environmental constraints as a value within the company [52], and obtaining support from senior management.

2.2. Innovation within Small Structures

2.2.1. Innovation within Small and Medium Enterprises

Managers and owners of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are advised to prioritize innovation as a fundamental component of their strategic approach, as it can offer a competitive edge to their businesses [53]. Innovation not only enhances individuals’ lives but also provides novel avenues for improvement and success in addressing emerging challenges within the business environment.

Innovation plays a crucial role in enhancing the competitive advantage of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) [54,55]. It facilitates the exploration of novel concepts and opportunities [56] by encompassing the implementation of fresh methodologies, products, and/or systems, along with innovative strategies to enhance market competitiveness [57]. According to Martínez-Román and Romero (2017) [58], innovation can be viewed through two distinct dimensions: the personal attributes of the entrepreneur and the organizational characteristics. The former pertains to the beliefs and inclinations of entrepreneurs, while the latter focuses on the company’s culture. Martínez-Román and Romero (2017) [58] suggest that the organizational culture exerts a more significant impact on the innovation process compared to the personal traits of entrepreneurs.

A business innovation is characterized as a novel or enhanced product or business procedure or a combination of both that significantly deviates from the firm’s previous offerings and has been introduced to the market or implemented by the firm [59]. A significant portion of data within the field of innovation research aligns with the guidelines set forth in the Oslo Manual [28], which provides a framework for evaluating, collecting, and analyzing data related to innovation activities. However, current metrics used to measure innovation primarily focus on binary indicators for product and process innovation [60]. Despite the limitations associated with these metrics, they can provide valuable information regarding the specific effects of different types of innovation on the operational effectiveness of firms.

When examining the impact of innovation on the productivity of firms, the choice of the productivity measurement method holds significance. Existing research commonly employs labor productivity (i.e., output per unit of labor input) or total factor productivity (TFP) represented by an index. Each of these measures presents distinct advantages and drawbacks. TFP is theoretically more comprehensive, as it captures the influence of innovation on both labor and capital productivity. However, a key limitation is its indirect nature, necessitating an estimation through aggregation techniques like the Malmquist index. Conversely, labor productivity can be directly calculated by dividing total output by labor input units, though it does not explicitly consider innovation’s impact on capital productivity. Nevertheless, this influence can be accounted for effectively in regression analyses. This may explain the prevalence of studies utilizing labor productivity compared to those employing TFP. For instance, Coad et al. (2015) [61], Crowley and McCann (2018) [3], Griffith et al. (2006) [9], Hall et al. (2009) [11], Hashi and Stojčić (2013) [62], and Raffo et al. (2008) [63] predominantly focus on labor productivity [3,9,11,62,63], while Huergo and Moreno (2011) [64] and Parisi et al. (2006) [12] are among the few exploring TFP. This study specifically investigates the impact on labor productivity, measured as the real value added per employee [12,64].

While the relationship between firm size and innovation decisions is subject to debate, evidence suggests that larger firms tend to allocate more resources to R&D and exhibit a greater propensity for innovation [8,11,13,62,65]. However, the influence of firm size on innovation outcomes may vary depending on industry-specific circumstances. For instance, larger firms may excel in capital-intensive industries, whereas smaller firms may have advantages in sectors requiring skilled labor [66]. The role of firm age in innovation is inconclusive, with some studies indicating that older firms are more innovative, while others find no significant or negative relationships [8,65,67].

Firms located in urban centers and clustered regions benefit from easier access to skilled labor, advanced infrastructure, and technological knowledge spillovers, which enhance their innovation capabilities [68,69] and overall performance [4,70,71,72]. Conversely, firms in developing countries face challenges in establishing and maintaining innovative networks necessary for engaging in R&D and innovation activities [63].

Numerous research studies have consistently demonstrated a positive correlation between innovation and firm performance [3,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. However, divergent perspectives exist in the literature. For instance, Crowley and McCann (2018) [3] observed a negative association between innovation and firm value added per employee in transition economies [3]. Similarly, Griffith et al. (2006) [9] and Raffo et al. (2008) [63] reported adverse effects of innovation on firm labor productivity in Germany and Argentina, respectively [9,63]. This negative impact on firm productivity due to innovation was also noted in Ireland [73]. Roper et al. (2008) [73] propose that these detrimental outcomes stem from the disruptive nature of innovation and its influence on the product life cycle [73]. The introduction of a new product may disrupt production processes, leading to reduced firm productivity. In the context of the product life cycle, there may be a period required for the efficient production of the new product before it positively impacts firm productivity. Additionally, Coad and Rao (2008) [7] suggest that significant time lags may exist in translating innovation into economic performance. The transformation of a product concept into efficient manufacturing practices is both resource-intensive and time-consuming [7].

It is important to highlight that the majority of research endeavors focus on investigating the impact of innovation on organizational performance across various contexts, such as large corporations, small businesses, and manufacturing firms. However, there is a noticeable scarcity or even a complete absence of studies that delve into the examination of innovation within professions situated within the social and solidarity economy sector. This sector is notably characterized by a prevalence of informal practices, necessitating a restructuring through innovative approaches. Furthermore, there is a notable dearth of research efforts aimed at evaluating the influence of innovation on the social and solidarity economy sector.

Consequently, there is a limited number of studies that seek to incorporate innovative strategies within the social and solidarity economy sector, underscoring the imperative need to analyze this aspect. Furthermore, the existing literature predominantly emphasizes the role of innovation in addressing environmental challenges within organizations. Nevertheless, there is a scarcity of studies that specifically examine the integration of innovative strategies to mitigate waste generation in the tasks performed by artisans within the social and solidarity economy sector, which can have adverse environmental implications. Consequently, there is a pressing need to underscore the importance of incorporating innovative solutions within this sector.

2.2.2. Innovation within the Social and Solidarity Economy Sector

It is obvious that tradition is an important pillar in the social and solidarity economy sector. Additionally, previous research indicates that tradition is instrumental in cultivating a market consensus for innovations within the creative and cultural sectors. In order to adapt traditional elements to contemporary requirements [74], these elements must be reconfigured into new products that resonate with current sociocultural trends, thereby satisfying modern standards of performance and utility [75]. The recombinant process, which characterizes the creation of new products in creative and cultural industries, represents a significant area of inquiry that diverges from the practices observed in social and solidarity economy industries [76]. Consequently, it is essential to identify the pivotal moments in this process and assess their efficacy, as prior scholars have derived valuable insights from the examination of innovative products from the past [77]. Such historical analyses also enable the potential identification of values, practices, and competencies associated with specific traditions that may contribute to the ongoing development of distinctive products and services [78]. It is increasingly acknowledged that knowledge of the past serves as a potent and unique source of innovative advantage [74]. By incorporating historical knowledge into new products, the concept of “innovation through tradition” is employed to develop novel offerings that can evoke positive consumer emotions and highlight innovative design features [79]. Connections to the past can be established through the exploration of traditions, which encompass “collections of cultural elements that may include symbols, material objects, myths, custodians, rituals, temporal qualities, as well as collective identities and memories” [80]. The integration of resources rooted in tradition and history may afford firms unique opportunities for innovation, value realization, and the attainment of a sustained competitive advantage [81]. Given that tradition plays a fundamental role in fostering innovation, particularly through the recombination of established knowledge and elements, this approach to recombination offers a novel strategy for organizations to adapt to contemporary contexts [82].

De Massis (2016) [81] articulates the concept of “innovation through tradition” as a novel product innovation strategy encompassing four primary elements: (1) the sources of historical knowledge pertinent to the organization or its regional and cultural heritage; (2) the forms of historical knowledge, which may be either codified (such as raw materials, product labeling, and manufacturing techniques) or tacit (including assumptions, values, and beliefs); (3) product innovation that leverages historical knowledge to enhance product functionalities or meanings; and (4) organizational capability, which involves the internalization and reinterpretation of past knowledge to facilitate its assimilation and dissemination throughout the organization, thereby integrating this knowledge with contemporary technologies to foster product innovation. Furthermore, Wernerfelt (1984) [83], in alignment with the “resource-based view” (RBV) [84], posits that the competitive advantage of enterprises is derived from the diverse resources they possess. To effectively implement technological innovations, organizations must identify market opportunities, enhance their internal technological capabilities, and address internal deficiencies through external support. Distinctive attributes such as a streamlined organizational structure, effective internal communication, and nimble decision-making processes are recognized as intrinsic advantages that facilitate technological innovation [85]. Rung-Tai Lin (2007) [86] introduced a cultural product design model comprising three principal phases: the conceptual model, the research methodology, and the design process [86,87,88].

In fact, innovation remains an important concept and must be studied thoroughly for this purpose; it is essential to explore this concept to be able to solve some problems found within the industry, especially in the social and solidarity economy industry.

The next step is to answer the following question: How can innovation be introduced into the Moroccan social and solidarity economy sector?

3. The Methodology Followed

3.1. Research Methodology and Sample

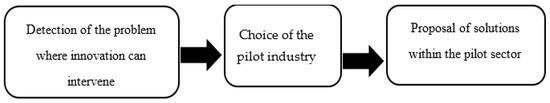

We have developed a new, innovative tool to introduce the notion of innovation considered as an essential concept for improving business processes and ensuring the development of sectors. Our objective is to implement this approach in the unique context of the social and solidarity economy sector in Morocco. To achieve this goal, we define the methodology as shown in the following Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The methodology used.

This research focused on small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) operating within the social and solidarity economy sector in Morocco to investigate the potential for addressing challenges through innovative approaches. The selection of companies was based on a stratified approach, categorizing them into various units such as those in the leather, pottery, and tapestry sectors. This stratified method was employed to ensure a comprehensive representation of the diverse companies within these sectors. The study aimed to provide a comprehensive analysis of how the nature of challenges influences the effectiveness of introducing and utilizing innovative tools within the Moroccan social and solidarity economy sector.

The study population consisted of all companies within the Moroccan social and solidarity economy sector, totaling 147,310 businesses, according to data from the Ministry of Crafts and the Social and Solidarity Economy in Morocco. The sample size for this study included 285 companies, comprising 170 cooperatives, 95 associations, and 20 mutual societies. Despite mutual societies representing a smaller proportion of businesses, they present unique challenges and operational structures distinct from cooperatives and associations. By focusing primarily on cooperatives and associations, the research aimed to delve into these specific challenges and their impacts on business operations.

The Moroccan social and solidarity economy sector plays a vital role in facilitating employment opportunities across various domains. Therefore, gaining insights into the internal dynamics and challenges faced by this sector is crucial for devising informed policies and initiatives to enhance its financial performance and promote the commercialization of Moroccan artisanal products on both national and international scales. Given the diverse range of activities within the sector, examining companies from multiple industries and geographical locations allows for a comprehensive exploration of perspectives and experiences that would not be adequately captured through a superficial analysis.

The sample size for the study was determined using the G Power software application version 3.1.9.7, which recommended an ideal sample size of 302. Out of the 302 questionnaires distributed, 285 were returned, resulting in a response rate of 94%. The effect size (f2) was calculated to be 0.19, indicating a medium effect size in the study. Additionally, companies were selected using a stratification approach, categorizing them into various units such as leather, ceramics, sewing, brassware, and pottery. The application of this stratified method ensures a comprehensive and representative sample of the diverse Moroccan enterprises across different regions. Most operational surveys utilizing area-based sampling employ stratification to enhance statistical accuracy and tailor the sampling design to local conditions. Homogenization is achieved based on prior knowledge of specific attributes while considering the geographical distribution.

The use of the chosen method aims to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the challenges associated with the integration of innovation within the Moroccan social and solidarity economy sector. By employing a mixed-methods approach that combines both qualitative and quantitative methodologies, we can achieve a more holistic and nuanced perspective on the subject matter. Qualitative data can yield deeper insights and diverse viewpoints, whereas quantitative data can facilitate statistical generalizations.

Furthermore, the use of multiple methodologies enhances the validity and reliability of the research findings. Investigating the same research question through various methods allows for the corroboration or contradiction of conclusions, thereby improving the overall validity of the study. This triangulation of data sources and analytical techniques fortifies the robustness of the research.

Additionally, mixed methods provide the opportunity to explore different levels of analysis. This approach enables researchers to investigate the issue at both macro and micro levels. Quantitative methods can identify broader patterns and trends, while qualitative methods can explore the lived experiences and contextual factors influencing the phenomenon under investigation.

The study selected 302 companies within the Moroccan social and solidarity economy, with a specific focus on cooperatives and associations in Morocco. The research aims to gain insights into the unique characteristics of the Moroccan artisanal sector by examining the prevalent challenges faced by the sector and proposing innovative solutions as a first step toward introducing innovation to address these issues. The study acknowledges the significant roles played by associations, cooperatives, and mutual societies in supporting and facilitating the production of artisanal goods while overcoming various challenges. Emphasis is placed on improving operations within artisanal workshops by promoting creation, innovation, strategic planning, and organizational performance within small-scale structures.

To achieve the research objectives outlined in the methodology, it is essential to analyze the current state of the industrial sector within the social and solidarity economy in Morocco. This analysis involved following a series of steps to gather relevant data and insights.

- In order to conduct our research, we arranged a visit to the Ministry of Crafts and Social and Solidarity Economy sector in Morocco, where we engaged with several managers and executives within the industry. Additionally, we endeavored to reach out to numerous artisans to discuss their professions, the merits, drawbacks, as well as the challenges and risks they encounter. The initial observation by the group of participants revealed that the social and solidarity economy sector is confronted with various technical and organizational issues.

It is important to note that the study’s objectives were delineated as follows:

- -

- To identify the challenges and requirements encountered by the artisanal industry in Morocco;

- -

- To compile a report based on the research findings;

- -

- To pinpoint areas where innovation could play a role in addressing issues;

- -

- To select a pilot sector for further investigation;

- -

- To propose potential solutions.

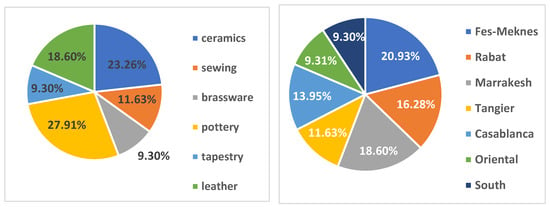

To tell the truth, during our visit to the Ministry of Craft Industry and the Social and Solidarity Economy in Morocco, as well as a set of artisanal workshops in several regions in Morocco, we realize a survey. During our survey (see Appendix A), we tried to contact as many companies as possible. Unfortunately, we received responses just from 285 companies, which are shown in Figure 4. The questions asked to companies concern the problems that these workshops find during the execution of their work and they think are able to be solved by an innovative solution, as well the levers pushing them to integrate an innovative solution within their workshops.

Figure 4.

Distribution of workshops by sector and by region.

A survey was undertaken to investigate the obstacles encountered within the social and solidarity economy sector. Despite extensive outreach efforts to a multitude of enterprises, feedback was obtained from a limited sample of 285 workshops spanning diverse sectors and geographical locations, as illustrated in the diagram (see Appendix B).

In fact, we tried to contact several companies from several sectors to be able to discuss the most common problems encountered when fulfilling customer orders (Figure 4). Thus, the companies come from several sectors, namely, 23.26% come from the ceramics sector, 11.63% from the sewing sector, 9.3% from the brassware sector, 27.91% from the pottery sector, 9.3% from the tapestry sector, and 18.6% from the leather sector.

Similarly, we tried to better diversify the sample surveyed while integrating a set of companies from several regions so that the sample could be more representative (Figure 4). It should be noted that 20.93% of the selected companies come from the Fès-Meknes region, 16.28% are from the Rabat area, 18.6% are from the Marrakesh region, 11.63% are from the Tangier region, 13.95% are from Casablanca, and 9.3% are from the east and the south, respectively.

- 2.

- The results of the survey, which will be examined using Excel methodologies, will be employed to pinpoint significant issues warranting innovative intervention and to underscore the obstacles faced within the industry. It is noteworthy that small and medium enterprises in Morocco demonstrate restricted adoption of innovative practices. As a result, the Moroccan social and solidarity economy sector, with a specific focus on the ceramics industry, has been chosen as a focal point for further investigation. Within this context, we have created a framework allowing us to describe the solution proposed by the use of CATIA V5.

3.2. Data Collection

This study utilized a mixed-methods approach to gather data, incorporating both face-to-face interactions and online platforms for survey distribution. The survey was created using the Google Forms platform to increase accessibility and reach a wider range of organizations, thereby enabling a more comprehensive and diverse dataset. The inclusion of in-person surveys alongside online distribution was intended to minimize potential biases that may arise from solely utilizing online surveys for data collection. Before data collection commenced, a pilot test was conducted to assess the validity and reliability of the questionnaire, a critical measure taken to ensure the accuracy and strength of the findings derived from the participants.

3.3. Data Analysis

The survey data were analyzed using Excel software (Microsoft Excel 2013 15.0.4420.1017) to investigate the primary challenges faced by the social and solidarity economy sector, obstacles encountered, factors facilitating the adoption of innovative tools in the surveyed organizations, and barriers hindering innovation implementation. Furthermore, SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics version 20) was employed to analyze the survey results, enabling the generation of graphs for statistical interpretation.

A specific sector, ceramics, was selected as a pilot study for proposing a cabinet solution tailored for the industry related to the social and solidarity economy sector, particularly the ceramics sector, to enhance workforce organization. The proposed solution framework was developed using CATIA V5 software, a globally recognized engineering and design solution known for its advanced 3D CAD capabilities.

CATIA V5 is widely acknowledged as a leading software suite for engineering and design, catering to various industrial entities ranging from original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) and their suppliers to smaller manufacturers and designers. Renowned for its innovation and design capabilities, CATIA V5 goes beyond conventional CAD tools by incorporating eco-design principles and optimizing designs to create intelligent, energy-efficient products.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Analysis of the Survey Results

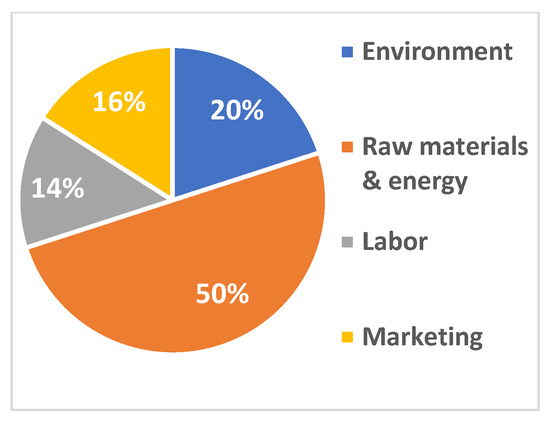

As a result, after questioning the chosen workshops, we detected the existence of the problems shown in Figure 5 and Table 1.

Figure 5.

The problems encountered during the lifecycle of the product.

Table 1.

The problems encountered by the surveyed companies.

The Moroccan social and solidarity economy sector has difficulty managing all of its products. During the first stage of identifying needs, several topics emerged throughout the life cycle of the artisanal product.

- Environment: 20% of the companies surveyed declare having this kind of problem. Therefore, artisanal production generates a range of waste that has a harmful impact on the environment, whether at the tannery or in bone working, metal or brassware. Therefore, pollution is the main result of waste occurring in the form of carbon dioxide (atmospheric), liquid discharges, or heavy metals or toxic salts.

- Raw materials and energy: 50% of the companies surveyed declare having this kind of problem. Therefore, raw materials constitute a redundant problem in the cottage industry because of multiple causes, namely, an insufficiency of technical means of production and cost prices, which are considered exorbitant.

- Labor: 14% of the companies surveyed declare having this kind of problem. Note that craftsmen work in dismal conditions that could have repercussions on the production of workers because workstations do not allow workers to be comfortable carrying out their tasks due to clutter and poor space layouts.

- Marketing: 16% of the companies surveyed declare having this kind of problem. Note that the social and solidarity economy sector must ensure the wider spread of its products throughout the world since the sector’s participation in fairs and exhibitions remains limited. It should be noted that most artisans in the sector remain confined to family structures, which harms the propagation of artisanal art.

In fact, the problem that has a harmful impact on the environment is related to the waste of raw materials. The latter has several causes, including the lack of organization and management of artisanal workshops.

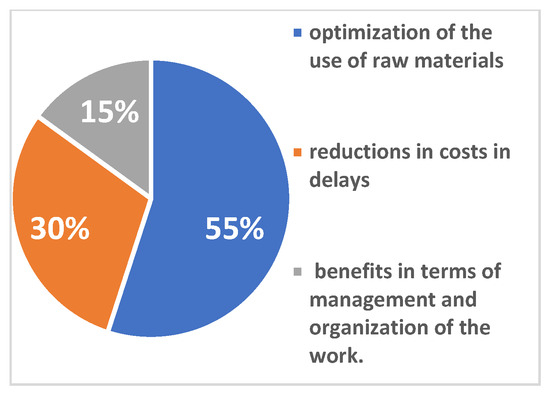

Concerning the levers favoring the introduction of an innovative solution the results are presented in Figure 6 and Table 2.

Figure 6.

The levers favoring the introduction of an innovative approach.

Table 2.

The levers promoting the implementation of innovation.

According to the diagram presented below, we find that 55% of the workshops surveyed declare the optimization of the use of raw materials, 30% select the reductions in costs and delays, and 15% opt for benefits in terms of management and organization of the work.

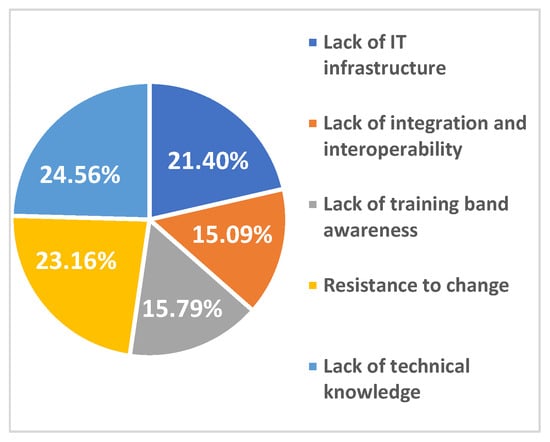

Concerning the factors impeding the integration of an innovative solution, the results are presented in Figure 7 and Table 3.

Figure 7.

The hindrances impeding the integration of an innovative approach.

Table 3.

The barriers preventing the implementation of innovation.

Taking into account the factors preventing the integration of innovation, we find that 21.40% of the companies questioned have a preference for a lack of IT infrastructure, 15.09% were satisfied on the factor relating to lack of integration and interoperability, 15.79% have opted for the factor relating to the lack of training, 23.16% prefer the resistance to change, and 24.56% think about the lack of technical knowledge.

This means that there is an urgent need to propose an innovative solution for solving the problem related to the waste of raw materials within the sector. Additionally, the workshops surveyed are ready to accept and to integrate an innovative solution and even if to invest in searching and finding some solutions in the hope of solving their daily problems, which encouraged us to furnish an effort for finding a suitable solution for the problems declared previously.

Therefore, Morocco remains a country with cultural diversity and a heritage characterized by a mixture of several civilizations on the economic side, Morocco has sectors and activities remaining as important pillars in terms of production, service provision, and job creation. Among these sectors, we can cite the leather sector, the brassware sector, the wood sector, the pottery sector, and the ceramic sector, which we will choose as a target sector.

In fact, the ceramic sector faces an enormous waste of raw materials (with losses of time, effort, and money). Therefore, in the next paragraph, we will further detail the problem, as well as propose an innovative solution to ensure the efficient management of production, which will contribute to reducing the waste of raw materials.

4.2. The Problem of Waste of Raw Materials and Management within the Chosen Sector

According to Eurostats (2021) [89] the waste generated in the construction sector, including the marble and ceramic sectors, represents more than 35% of the total waste. The latter corresponds to all materials rejected and not used during construction, excavation, or demolition activities. According to the European Commission and the Directorate General for the Environment (2017) [90], 700 kg of construction waste is generated per inhabitant per year. As a result, the accumulation of this waste constitutes a current and future environmental, social, and economic threat [91].

Moreover, the notion of recycling remains one of the objectives set out by sustainable development and allows the promotion of the circular economy through the management of waste in the value chain [92]. As a result, several studies support the need for the reuse and recycling of construction waste following the constantly growing demand for raw materials. Thus, a multitude of authors have carried out work to improve the use of recycled resources [93]. Moreover, the physicochemical characteristics of the residues were studied since they impact the ceramic process. However, the use of construction materials as raw materials in the production of ceramics remains difficult due to the heterogeneity and variability of the characteristics of the residues [94,95,96,97].

In fact, the concept of recycling has ecological advantages. Hence, sorting is needed since operators classify waste manually and only metals are separated automatically [98]. As a result, several studies and works are interested in the search for automated techniques.

It should be noted that the problem of waste remains a very common problem within the ceramics sector for several reasons, among which we can cite the lack of organization and the disorder found within the workshops. For this purpose, we propose below a solution that will reinforce the notion of recycling within artisanal workshops, since this culture is absent within the latter, and will allow an organization of the production of ceramic forms, since during the production of ceramic shapes to fulfil a specific order, there are certain shapes that will not be used and that will represent a production surplus. As a result, we are going to present a solution that will allow us to store surplus production and recycle it in the execution of future orders.

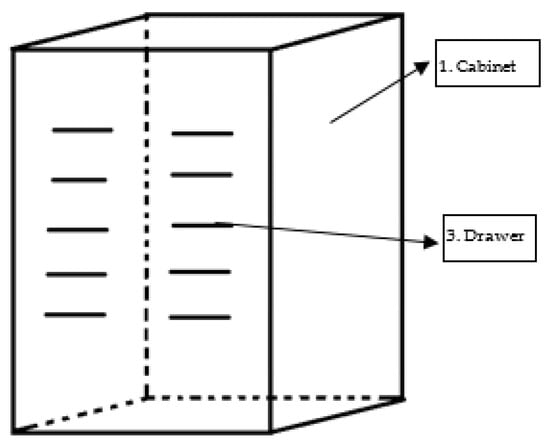

4.3. Implementation of the Functionalities Proposed within the Ceramics Sector

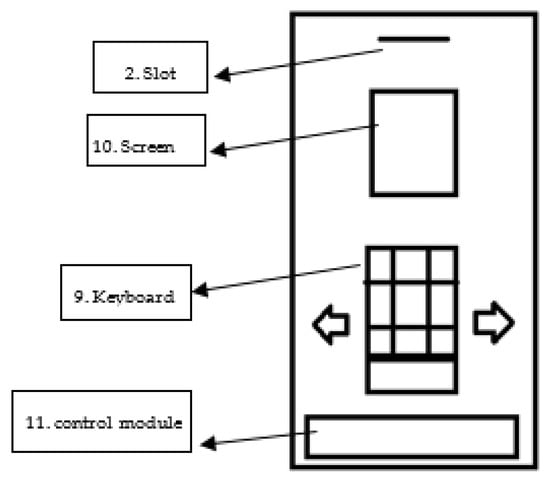

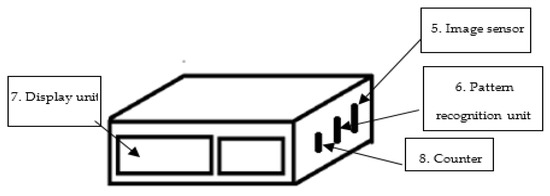

Figure 8.

Front view of the cabinet.

Figure 9.

Profile view of the cabinet.

Figure 10.

Presentation of the mold (4) for the triangular shape.

Figure 11.

Front view of the drawer.

Our invention is a cabinet (1) that facilitates the reduction of waste by enabling the recycling of shapes that have been stored but not utilized in a particular order, as they are intended for use in a subsequent arrangement. It comprises a slot (2) used to insert the opening card, which is a card similar to a bank card used to open the cabinet and that is provided with a microchip capable of permanently storing the history and cabinet input–output parameters made by the user.

In addition, to remove primitive shapes from the cabinet, the user must present his or her card and dial the secret security number to open the cabinet or to distribute the desired shapes.

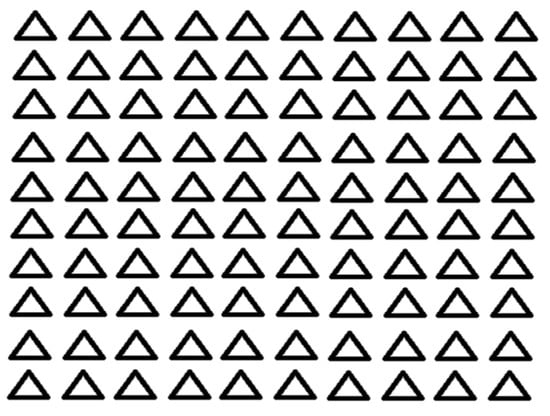

Within each drawer (3) of the cabinet, there is a device used to identify the shapes that we want to store in the drawer comprising molds (4), which makes it possible to house the stored shapes. It is assumed that each mold can accommodate 100 shapes.

Then, the drawer is equipped with a digital image sensor (5) used to record the shape images. Once this is performed, there is a pattern recognition unit (6) that applies a shape recognition algorithm to the images captured, and the recognized shapes are displayed on a display unit (the drawer face) (7).

Likewise, the drawers are equipped with a counter (8) allowing you to count the number of shapes that have filled the mold. The data found are saved on the user card.

Although they can be located in different places, the cabinet (1) is equipped with a keyboard (9) and a screen (10) to choose either the “inputs” or “outputs” menu.

In addition, the cabinet includes a control module (11) with an internet connection. With this arrangement in which all electronic devices are interconnected with each other, the operation of the cabinet is simple, as described below.

Notably, our invention presents a significant advancement over prior methodologies by effectively addressing the challenges associated with the organization and arrangement of ceramic production workshops. It facilitates a comprehensive understanding of the original shapes stored, quantified in numerical terms.

4.4. Operation

4.4.1. The Inputs

Fill the cabinet according to the primitive shapes that we want to store first; each drawer will contain a type of shape and each shape will be placed in a mold. To perform this, it is essential to insert the card through the slot by entering the security code corresponding to the holder. Once this is performed, you can choose the “inputs” menu on the screen.

Once the cabinet is open, you can insert each shape into the drawer that suits it.

Once the shape is introduced into the mold, the image sensor records the shape of the image, the shape recognition unit applies a shape recognition algorithm to the image data to recognize the introduced shape, and the display unit shows the recognized shape. Additionally, it allows you to display the number of existing shapes in the drawer based on the presence of a counter, allowing you to control the entries in each drawer since each shape passed in front of the counter is counted so that the final number is displayed on the display unit and represents the total number of shapes in the drawer.

4.4.2. Outputs

To remove a certain number of primitive shapes from the cabinet, the user must present his or her user card and dial the secret code with which the authorization to open the cabinet will be generated. Once this is performed, you can choose the “outputs” menu on the screen using the keyboard. After that, we can type the number of shapes on the keyboard and choose the type of shapes of interest. After that, the user can open the drawer having the chosen shapes. Once these shapes pass the counter, the number passed is deducted from the total.

Hence, the invention provides a comprehensive understanding of the contents of each drawer within the cabinet and will facilitate the management of the inherent disorganization present in the ceramic production workshops. Additionally, this knowledge will contribute to the reduction in waste and the efficient utilization of raw materials through the recycling of stored forms.

The solution presented here has several advantages since it includes molds having a very specific shape, allowing each mold to house a single type of shape of ceramic parts. Likewise, its content is recorded in the chip of the electronic card each time it is inserted into the slot (2), which can lead to the organization of the shapes stored for a future use.

It should also be noted that this cabinet allows for the minimization of waste following the recycling of shapes stored and not used in a specific order since they will be used in a future order.

4.5. Implications of the Integration of the Proposed Solution within the Sector

Once we had finished realizing the proposed tool, we deemed it necessary to implement it within two companies operating in the ceramics field.

Both companies are small businesses; they include a limited number of staff and they manufacture the ceramics pieces from the clay working phase to the installation phase. To tell the truth, we have generally observed that it is the prospect of profits to be made that constitutes the major incentive for companies to integrate a new constraint. The problem then lies in the ability to identify these opportunities.

The choice of companies was based on a visit to the Regional Directorate of Crafts and Social Economy in the Fez-Meknes region, where we tried to contact a significant number of companies with a view to implementing the tool. Finally, we agreed on the choice of two companies (Saada for traditional ceramics and Tayssir ceramics) for several reasons, as follows:

- Managers from both companies agreed to implement and test the tool within their companies;

- Both companies have shown that the problem of wasting raw materials in their workshops remains the most redundant;

- Company managers have a minimum educational level, allowing them to work with the tool.

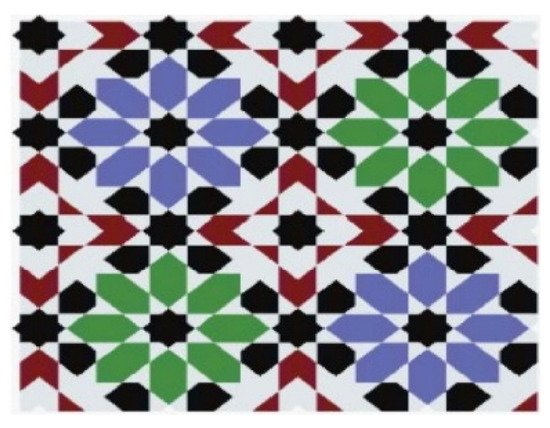

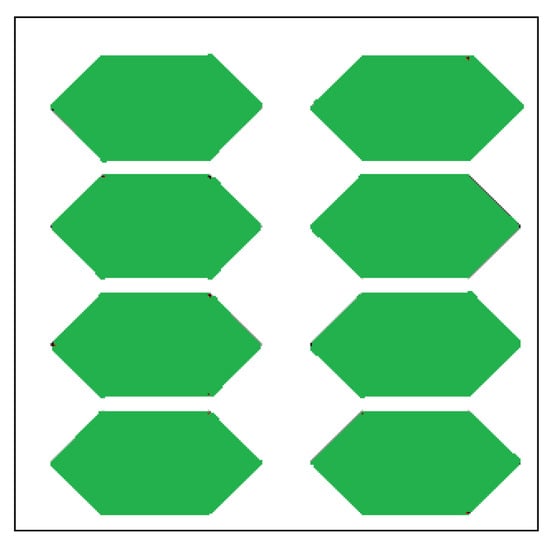

Then, we received a decoration order with a surface area of 10 m2 using the décor shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

The decoration chosen by the customer.

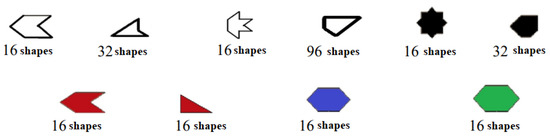

It should be noted that this decoration contains the forms shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

The shapes that the decoration contains.

Number of shapes needed to decorate the chosen surface = (number of existing shapes in decorative panel/surface of decorative panel) × surface we like to decorate.

Therefore, in our order we have the following:

Surface of decorative panel = 1/5 m2;

Surface we like to decorate = 10 m2.

For example, the number of shapes in each base tile to cut are determined in the traditional workshops by leaving gaps between the shapes to be able to cut (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

The base tile to cut within workshops.

Number of tiles to be produced (see Table 4) = Number of shapes needed to decorate the chosen surface/Number of shapes in each base tile to cut.

Table 4.

Calculation of the number of tiles to be produced.

As a result, there will be shapes that will be stored for future use (Table 5).

Table 5.

Calculation of shapes stored within the intelligent cabinet.

Shapes of tiles by color = Number of tiles to be produced × Number of shapes in each base tile to cut.

Shapes stored = Shapes of tiles by color − Number of shapes needed to decorate the chosen surface.

Therefore, we conclude that there will be shapes that will be kept and stored for future use in the cabinet, which gives us an idea of the number of shapes already existing in stock during a future use. As a result, we are going to produce just the difference between the shapes we need to execute a very specific order and the number of shapes already existing in stock. Therefore, this strategy has impacts on the waste of raw materials, which will decrease, as well as on the organization and management of work. Likewise, production times and costs will decrease since we are going to produce less than the exact quantity we need for executing the order and will take into consideration the stock, which will have impacts on production costs and on delays.

Moreover, the proposed solution will allow us to resolve the problems detected during the survey carried out within the artisanal workshops, since it will make it possible to reduce the waste of raw materials, to organize the work by giving a clear idea and specifies the number of shapes already existing in stock, and to reduce production costs and delays.

The implementation of a specialized cabinet in two pilot companies is expected to reduce raw material waste by storing excess primitive forms for recycling in future orders. Observations following the introduction of this tool in the pilot companies revealed several key points. Firstly, the tool promotes a collective work environment where craftsmen store surplus primitive forms for redistribution among all workers, fostering group cohesion and energy within the company. This tool also enhances relationships among stakeholders by facilitating exchanges and creating a cohesive work environment that encourages collaborative efforts. Additionally, the tool aids in resolving organizational and management issues by providing visibility into stored shapes through a chip card system. Thus, when we insert a chip card into the slot, we will have an idea of the set of stored shapes. As a result, we can know how many shapes we will produce for the execution of a specific order. Consequently, the utilization of this cabinet enhances the efficiency of planning and coordinating production operations. Overall, the introduction of this cabinet is anticipated to streamline production processes, reduce disorder, and enhance overall efficiency within the companies.

5. Discussion

This study serves as an assessment of the social and solidarity economy sector in Morocco, focusing on identifying the barriers hindering companies in this sector from adopting innovative practices, as well as the drivers and advantages of such integration, along with the challenges impeding this process. The research encompassed a diverse range of industries within the social and solidarity economy sector, involving a total of 285 companies. Consequently, we recommend that the government undertake a more extensive and comprehensive study by expanding the sample size to include a greater number of companies and by devising a strategy to ensure a more representative sample from various regions of Morocco in collaboration with Moroccan universities and the Ministry of Crafts and the Social and Solidarity Economy in Morocco.

Furthermore, the issue of waste generation from raw materials in certain sectors of the social and solidarity economy, particularly in the ceramic industry, where the cutting phase is a critical stage in the product manufacturing lifecycle leading to waste generation, persists as a significant challenge. To address this, we have proposed a tool to minimize raw material wastage and enhance organization and efficiency during the production of ceramic pieces in artisanal workshops, thereby streamlining work processes and reducing disorder.

This cabinet is designed for the storage of basic shapes resulting from the cutting of ceramic pieces. It is equipped with various components, including a slot for inserting a user card, drawers, molds within each drawer for storing the shapes, a keyboard for entering a security code and selecting input or output options on the screen, a screen, and a control module with internet connectivity. The drawers feature a digital image sensor to capture photos of incoming or outgoing shapes, a shape recognition unit, a display unit showing the types and quantities of shapes in each drawer, and an input–output counter for tracking incoming and outgoing forms. The molds in the cabinet are specifically shaped to accommodate individual types of ceramic shapes. Data on the cabinet’s contents are recorded on the electronic card’s chip each time it is inserted, facilitating inventory management and reducing disorder in artisanal workshops. The cabinet promotes waste minimization by enabling the recycling of stored shapes in a systematic manner for future use. Implemented in two Moroccan companies in the social and solidarity economy sector within the ceramics industry, this innovation has shown promise in addressing material waste issues and introducing recycling practices in the industry associated with the social and solidarity economy sector. It facilitates the realization of all the objectives outlined by an innovative process related to organizing work processes and reducing disorder in the sector, enhancing production efficiency and promoting a more structured approach to manufacturing [3,7,8,9,10,11,12,13].

Furthermore, the incorporation of innovation through the proposed tool necessitates the engagement of all stakeholders associated with the company, whether directly or indirectly, in various aspects of the product life cycle. Additionally, it requires the organization to broaden and adapt its external relational networks, which may significantly alter established practices within the company.

The implementation of the proposed tool within the industry indicates that the organization has recognized innovation as a core value, thereby legitimizing its commitment to all personnel [99]. This commitment is driven by the intention to alter operational practices while maintaining the foundational guiding values of the organization. Consequently, the company must realign its strategic approach by embedding innovation as a fundamental principle within its overarching policy framework. This shift entails acknowledging a new constraint, specifically the innovative constraint, which will necessitate a reevaluation and reordering of the company’s traditional value hierarchy, including aspects such as performance, quality, and cost [75].

6. Limitations

The utilization of the proposed tool may be constrained by various limitations. These limitations encompass coordination issues, such as communication challenges stemming from concerns about knowledge loss or feelings of exclusion. These factors significantly impact the effective coordination of collaborative endeavors. Coordination and communication difficulties are common and can impede group work progress. Additionally, some artisans may be apprehensive about relinquishing their expertise and may feel excluded when confronted with the tool’s implementation, potentially leading to resistance to change. Furthermore, certain craftsmen may refuse to adopt the system due to reasons like incompetence, resistance to altering established practices, limited technical knowledge in artisanal settings, and constrained responsiveness skills.

It is important to acknowledge that the deployment of the proposed tool within the pilot companies encounters several challenges that may jeopardize the success of the organizational changes being implemented. Consequently, to facilitate effective change, it is crucial to adopt a structured approach that aligns with change management principles, thereby enhancing the likelihood of achieving the intended outcomes. Specifically, organizational change necessitates the application of a systematic methodology, which includes conducting a diagnostic assessment based on an initial analysis of the sector’s organizational structure where the tool will be applied. This process should involve the identification of a range of solutions aimed at mitigating potential risks of failure, as well as an evaluation of these solutions. Furthermore, a significant aspect of this endeavor is the organization’s ability to adapt to the various constraints introduced by the proposed tool. Therefore, the insights gained from this practical experience will serve to either validate or refute the software’s adaptability to the unique constraints characteristic of this type of enterprise. This validation process will ultimately determine whether the implementation of the proposed tool enables social and solidarity economy industries to maintain their distinctiveness while simultaneously fostering a more structured, organized, and profitable operational framework.

Note that the Moroccan social and solidarity economy sector contains considerable energy and skills that can be integrated into the field of innovation. Morocco also has very influential potentialities, namely, the transparency of sectoral plans, technological infrastructures, and industrial property; however, it turns out that this field faces obstacles that could attenuate the speed of these achievements, namely, a lack of global vision of innovation. For this purpose, it is essential to revalue and reevaluate innovation while attempting to incorporate it into production and management processes. Faced with these challenges, the sector must obey two imperatives: innovate and open up to new ideas, concepts, and technologies to conquer new markets.

7. Conclusions

Integrating an innovative approach ensures the collection and management of data on the products; it also ensures the exchange of documents and data while offering a space for sharing all of the information, which allows a reduction in time because it guarantees the filtration and localization of information. It should be noted that innovation is supported by the allocation of a set of heterogeneous rewards for companies integrated into dynamic knowledge networks [100,101] and having experience in research and development [102,103]. Note that the links between SMEs and innovation partners are complicated and go beyond geographical links.

Based on direct interviews and a survey within workshops from multiple regions of Morocco, we find some results showing that approximately 50% of the enterprises surveyed find problems of waste of raw materials and energy. The major incentive pushing the workshops to integrate an innovative approach is the optimization of the use of raw materials, with a rate of 55%. That is why we propose an intelligent cabinet that participates in the minimization of the waste of raw materials, as well as the management and the organization of the work within workshops.

It is to be concluded that the introduction of innovation within the artisanal sector will have a positive effect on the latter since the sector will be more structured, which will reduce the anarchy found, especially during the execution of all the tasks by craftsmen. Even more, this proposed model could be generalized in such a way as to introduce other design tools within the sector; it must also be accompanied by a strategy allowing the marketing of the product to transit the ceramic sector from routine activity toward innovative design activity.

The integration of innovation within the Moroccan social and solidarity economy sector presents significant challenges, particularly in relation to change management. For the successful implementation of innovation, the sector studied must undertake substantial efforts to reassess the associated risks. Furthermore, it is imperative for company leaders to collaborate with academic institutions to facilitate additional training aimed at enhancing employee awareness regarding the necessity of adopting innovative methodologies and effectively managing organizational change, along with the risks they entail. Once a comprehensive policy centered on organizational change is established, it becomes feasible to propose tailored innovative approaches and tools that align with the specific structural components of the organization, thereby facilitating the incorporation of innovation into their operational processes.

Author Contributions

A.M.S. conducted the survey and wrote the main article, and F.Y. prepared the figures and validated the results. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

We declare that the authors have obtained an informed consent from the participants in this research.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. A Survey

A survey for companies in the social economy sector.

As part of my research in the field of innovation, I am carrying out a study concerning the artisanal sector in Morocco to analyze the current situation of companies in order to draw conclusions.

Please answer this survey and send it back to me by e-mail.

| Company name |

| The social reason |

| Activity area |

| Where is your company located? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| What is the major problem you may encounter in your business? |

|

|

|

|

| The levers favoring the introduction of an innovative approach |

|

|

|

| The hindrances that impede the integration of an innovative approach |

|

|

|

|

|

| Thank you for your collaboration. |

Appendix B. The Companies Interviewed with Their Sector of Activity

Table A1.

The companies surveyed with their location and sector of activity.

Table A1.

The companies surveyed with their location and sector of activity.

| Number | Company | Location | Activity Sector |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Saada Jild | Fes, Morocco | leather |

| 2 | Coopérative Diamant Bleu | Fes, Morocco | tapestry |

| 3 | Andalous | Rabat, Morocco | brassware |

| 4 | Cadeaux et Artisanat du Maroc | Fes, Morocco | brassware |

| 5 | Majdoul Jdadi | Tangier, Morocco | sewing |

| 6 | Kenzi Kaftan | Oujda, Morocco | sewing |

| 7 | Mediterraneen Services | Marrakesh, Morocco | tapestry |

| 8 | Almasnouat Aljidiya | Casablanca, Morocco | leather |

| 9 | Terrazat | Fes, Morocco | sewing |

| 10 | Mealemine Alfakhara | Marrakesh, Morocco | pottery |

| 11 | Bouananiya Ceramic | Fes, Morocco | ceramic |

| 12 | Dar Al Orssane | Casabalanca, Morocco | brassware |

| 13 | Alkhazaf Al Fassi | Fes, Morocco | pottery |

| 14 | Zarabi Dar Assanaa | Casablanca, Morocco | tapestry |

| 15 | Micheaal Ceramic Alfassi | Fes, Morocco | ceramic |

| 16 | Diamond Bleu | Oujda, Morocco | tapestry |

| 17 | Nour Masnouat Jildiya | Marrakesh, Morocco | leather |

| 18 | Tayssir Ceramic | Fes, Morocco | ceramic |

| 19 | Nissae Dhar Mahraz | Fes, Morocco | sewing |

| 20 | Al Fan Badiie | Rabat, Morocco | brassware |

| 21 | L’émotion Cuir Maroquinnerie | Casablanca, Morocco | leather |

| 22 | Alassala Taklidiya Alaalamiya Almaghribia | Casablanca, Morocco | leather |

| 23 | Alkhiraza Al Assila | Fes, Morocco | leather |

| 24 | Alimae | Laayoune, Morocco | leather |

| 25 | Alibar Adahabia | Laayoune, Morocco | leather |

| 26 | Zerine | Oujda, Morocco | leather |

| 27 | Alkhazaf Al Fani w Ceramic Al Fassi | Fes, Morocco | pottery |

| 28 | Karama Lintaj Wa Moualajat Atteene | Marrakesh, Morocco | pottery |

| 29 | Saada Li Zellige Takelidi | Fes, Morocco | ceramic |

| 30 | Almaater Lizellige Taklidi | Fes, Morocco | ceramic |

| 31 | Nass Fes | Fes, Morocco | ceramic |

| 32 | Almajd | Rabat, Morocco | ceramic |

| 33 | Mealemeeen Deraza | Fes, Morocco | tapestry |

| 34 | Alikhelass Linassij | Oujda, Morocco | tapestry |

| 35 | Tissage Artistique | Rabat, Morocco | tapestry |

| 36 | Alazamiya Lidiraza | Marrakesh, Morocco | Tapestry |

| 37 | Moubadarat Al Atlas Linassij Takelidi | Marrakesh, Morocco | tapestry |

| 38 | Chabab Lidiraza Wa Khiyata | Oujda, Morocco | tapestry |

| 39 | Nahar Jadid | Tangier, Morocco | tapestry |

| 40 | Adwal Linassij Taklidi | Casablanca, Morocco | tapestry |

| 41 | Cooperative Tinefela Linassij | Marrakesh, Morocco | tapestry |

| 42 | Cooperative Zarbiat Azaar | Casablanca, Morocco | tapestry |

| 43 | Cooperative Teereguilt | Laayoune, Morocco | tapestry |

| 44 | Alahbab Mekik | Rabat, Morocco | brassware |

| 45 | Nour Lilhidada Wa Talhim Sefrou | Fes, Morocco | brassware |

| 46 | Ettaj | Rabat, Morocco | brassware |

| 47 | Andalous Lientaj Fidiyat Wa Nouhasssiyat | Tangier, Morocco | brassware |

| 48 | Zohor Lilfidiyat | Tangier, Morocco | brassware |

| 49 | Alamane Lilkhiyata Taklidiya | Tangier, Morocco | sewing |

| 50 | Nour Albarak Lilkhiyata Taklidiya Wa Assriya | Rabat, Morocco | sewing |

| 51 | Nassr Lilkhiyata Taklidiya w Assriya | Casablanca, Morocco | sewing |

| 52 | Bichara Lilkhiyata Tarz wa Randa | Rabat, Morocco | sewing |

| 53 | Adrar Houlafae | Oujda, Morocco | sewing |

| 54 | Rahma Tapis | Marrakesh, Morocco | tapestry |

| 55 | Noor Lilzarabi | Oujda, Morocco | tapestry |

| 56 | Alroaa Alwardiya Lilkhiyat Attaklidiya | Dakhla, Morocco | sewing |

| 57 | Gold Loubana | Casablanca, Morocco | sewing |

| 58 | Association Meallemeen Debagha Chouara | Fes, Morocco | leather |

| 59 | Almeaalemine Lebbata | Fes, Morocco | leather |

| 60 | Arbab Maamel Debagha | Fes, Morocco | leather |

| 61 | Sonnae Alahdiya Arrondissement Al Meriniyeene | Fes, Morocco | leather |

| 62 | Mountejee Al Ahdiya | Marrakesh, Morocco | leather |

| 63 | Alassala Limealemee Alkhiraza Fes | Fes, Morocco | leather |

| 64 | Almahara Lilahdiya Taklidiya Fes | Fes, Morocco | leather |

| 65 | Alamal Limealemee Alahdiya Fes Medina | Fes, Morocco | leather |

| 66 | Salam Dar Debegh Ain Zleiten | Fes, Morocco | leather |

| 67 | Tadamoun Lidebagha Taklidiya Guerniz Fes | Fes, Morocco | leather |

| 68 | Almeaalemeen Alkharaza | Marrakesh, Morocco | leather |

| 69 | Ahl Fes Lilmeaalemeen Alkharaza | Fes, Morocco | leather |

| 70 | Association Nour Lilmasenouat Jildiya | Marrakesh, Morocco | leather |

| 71 | Sidi Mimoun Lil Fekhara | Rabat, Morocco | pottery |

| 72 | Salam Lisonae Al Fikhara | Rabat, Morocco | pottery |

| 73 | Nahda Fassia Lilfakhar W Tanmiya Wa Beea | Fes, Morocco | pottery |

| 74 | Sounae Al Fikhara Wa Ceramic De Barnamaj Tahadi Alalfiya | Fes, Morocco | pottery |

| 75 | Hiba lizelllige Taklidi Alfassi | Fes, Morocco | ceramic |

| 76 | Roa litanmiyat Ceramic Taklidi | Casablanca, Morocco | ceramic |

| 77 | Fassiya Liceramic Wfakhar | Fes, Morocco | pottery |

| 78 | Tourath Liceramic Wfakhar | Oujda, Morocco | ceramic |

| 79 | Alkhair Lilmealemeen Zelayjiya | Marrakesh, Morocco | ceramic |

| 80 | Tadamoun Liseghar Herafiyi Ceramic Wfakhar | Marrakesh, Morocco | pottery |

| 81 | Al Jayl Saed Lisinaat Ceramic w Fakhar | Tangier, Morocco | ceramic |

| 82 | Mealemine Deraza | Fes, Morocco | tapestry |

| 83 | Salam Lidiraza | Rabat, Morocco | tapestry |

| 84 | Mousaderee Wa Mountejee Zarabi | Casablanca, Morocco | tapestry |

| 85 | Hassania Likitae Diraza Fes | Fes, Morocco | tapestry |

| 86 | Nassij Limealeme Diraza | Marrakesh, Morocco | tapestry |

| 87 | Alahd Aljadid Lidiraza | Casablanca, Morocco | tapestry |

| 88 | Alfassiya Lidiraza | Fes, Morocco | tapestry |

| 89 | Alssahwa Lidiraza | Rabat, Morocco | tapestry |

| 90 | Association Raha Chams Lidiraza | Tangier, Morocco | tapestry |

| 91 | Assiciation Assala Lidiraza Wa Nassej Sefrou | Fes, Morocco | tapestry |

| 92 | Association Asdekae Sonae Taklidiyene Linouhas | Fes, Morocco | brassware |

| 93 | Al Aamal Alejtimaie Lil Mecanique Wa Talheem | Fes, Morocco | brassware |

| 94 | Assiciation Saiss Lilhidada Wmecanique Alaam | Fes, Morocco | brassware |

| 95 | Idriss Alakbar Lisonae Taklidiyeene Lil Mecanique Wa Talheem | Fes, Morocco | brassware |

| 96 | Association Meriniyene Li Talheem Wa Mecanique | Fes, Morocco | brassware |

| 97 | Association Salam Litalheem | Agadir, Morocco | brassware |

| 98 | Alkhiyata Taklidiya | Agadir, Morocco | sewing |

| 99 | Alkhiyata Wa Alkhayateen | Tangier, Morocco | sewing |

| 100 | Alkhiyata Taklidiya Zouagha Moulay Yaacoub | Fes, Morocco | sewing |

| 101 | Fonoun Yadawiya Lil Kheyata Taklidiya | Tangier, Morocco | sewing |

| 102 | Mereniyene Li Tarz Wa Khiyata Taklidiya | Fes, Morocco | sewing |

| 103 | Al Ibar Dahabiya Arrondissement Zouagha Bensouda | Fes, Morocco | sewing |

| 104 | al Ikhlass Lil Khiyata Taklidiya Fes | Fes, Morocco | sewing |

| 105 | Ibdaat Li Fonoun Al Khiyata Taklidiya | Rabat, Morocco | sewing |

| 106 | Al Khiyata Taklidiya Wa Tanmiya | Rabat, Morocco | sewing |

| 107 | Association Senaa Taklidiya Lil Asaala Al Fassiya | Fes, Morocco | sewing |

| 108 | Al Wafae Li Riayat Wa Tanmiyat Sanie Taklidi | Casablanca, Morocco | sewing |

| 109 | Alkarama Litanmiyat Almaraa | Marrakesh, Morocco | sewing |

| 110 | Seyaghat Houliye Wmoujawharat | Casablanca, Morocco | sewing |

| 111 | Moustakbal Seyaghat Houliye | Rabat, Morocco | sewing |

| 112 | Oum Zakariae | Rabat, Morocco | sewing |

| 113 | Wlad Lkteeb | Marrakesh, Morocco | sewing |

| 114 | Bahja Lilmasnouat Nabatiya Wtazyine | Marrakesh, Morocco | sewing |

| 115 | Hayat | Rabat, Morocco | brassware |

| 116 | Ikhlas | Casablanca, Morocco | brassware |

| 117 | Ayadi Amina | Oujda, Morocco | brassware |

| 118 | Amal | Oujda, Morocco | brassware |

| 119 | Houda | Rabat, Morocco | brassware |

| 120 | Tayssir | Agadir, Morocco | brassware |

| 121 | Amyawed Llmarea | Agadir, Morocco | brassware |

| 122 | Bir Tamtam | Fes, Morocco | brassware |

| 123 | Nisae Bladi | Agadir, Morocco | brassware |

| 124 | Sounae Taklidiyine Atlas | Marrakesh, Morocco | brassware |

| 125 | Fatima Fihriya | Rabat, Morocco | brassware |

| 126 | Oudrar | Marrakesh, Morocco | brassware |

| 127 | Amine | Casablanca, Morocco | ceramic |

| 128 | Al Fawzi | Tangier, Morocco | ceramic |

| 129 | Al khobarae | Rabat, Morocco | ceramic |

| 130 | Azaar | Marrakesh, Morocco | ceramic |

| 131 | Khidma Karawiya | Oujda, Morocco | ceramic |

| 132 | Tibkhikhine | Agadir, Morocco | ceramic |

| 133 | Fan Al Jibss | Marrakesh, Morocco | ceramic |

| 134 | Tboukiss | Marrakesh, Morocco | ceramic |

| 135 | Noujoum Al Khamssa | Rabat, Morocco | ceramic |

| 136 | Ikologia | Casablanca, Morocco | ceramic |

| 137 | Baba Routi | Rabat, Morocco | ceramic |

| 138 | Chouaae Sefrou | Fes, Morocco | ceramic |

| 139 | Kourba Kouti | Casablanca, Morocco | ceramic |

| 140 | Jnan Toufah Lizellige | Marrakesh, Morocco | ceramic |

| 141 | Al Istimrariya | Agadir, Morocco | ceramic |

| 142 | Al Killa | Oujda, Morocco | ceramic |

| 143 | Dar Al Karaz Lizellige | Rabat, Morocco | ceramic |

| 144 | Tourat Zelige Wa Fakhar | Fes, Morocco | ceramic |

| 145 | Farhana | Tangier, Morocco | ceramic |

| 146 | Tadfye | Marrakesh, Morocco | ceramic |

| 147 | Jodour Sefrou | Fes, Morocco | ceramic |

| 148 | Tifaout | Rabat, Morocco | ceramic |

| 149 | New Day | Oujda, Morocco | ceramic |

| 150 | Rida Allah | Agadir, Morocco | ceramic |

| 151 | Nas Aadloun | Oujda, Morocco | ceramic |

| 152 | Sanhaja | Fes, Morocco | ceramic |

| 153 | Jalila | Tangier, Morocco | ceramic |

| 154 | Akay Lisinaa | Marrakesh, Morocco | ceramic |

| 155 | Al Ghad Al Jadid | Tangier, Morocco | ceramic |

| 156 | Fadwati | Rabat, Morocco | ceramic |

| 157 | Al Ourssane | Casablanca, Morocco | ceramic |

| 158 | Loub | Marrakesh, Morocco | ceramic |

| 159 | Rawdat Al Azhar | Rabat, Morocco | ceramic |

| 160 | Serj Al Fassi | Fes, Morocco | ceramic |

| 161 | Kenzi | Oujda, Morocco | ceramic |

| 162 | Gold Loubana | Oujda, Morocco | ceramic |

| 163 | Achbal | Tangier, Morocco | ceramic |

| 164 | Al Imae | Rabat, Morocco | ceramic |

| 165 | Art Beauty Artisans | Marrakesh, Morocco | ceramic |

| 166 | New Style | Casablanca, Morocco | ceramic |

| 167 | Tanjid Li Sinaa | Rabat, Morocco | ceramic |

| 168 | Handicraft Cop | Agadir, Morocco | ceramic |

| 169 | Arroa | Oujda, Morocco | ceramic |

| 170 | Al Bahja | Marrakesh, Morocco | ceramic |

| 171 | Mantouj Rayan | Tangier, Morocco | ceramic |

| 172 | Dar Lfonoun | Casablanca, Morocco | ceramic |

| 173 | Al Wardiya Li Sinaa | Rabat, Morocco | ceramic |

| 174 | Dhar Al Mahraz Li Sinaa | Fes, Morocco | ceramic |

| 175 | Bnat Bab Allah | Agadir, Morocco | ceramic |

| 176 | Al Hadid | Oujda, Morocco | ceramic |

| 177 | Al Awda | Casablanca, Morocco | ceramic |

| 178 | Al Assl Attayib | Tangier, Morocco | ceramic |

| 179 | Al Mouamala | Rabat, Morocco | ceramic |

| 180 | Al Jamal | Marrakesh, Morocco | ceramic |

| 181 | Katre Nada | Oujda, Morocco | leather |

| 182 | Cooperative N’Kob | Marrakesh, Morocco | leather |

| 183 | Tifaouine Angal | Agadir, Morocco | leather |

| 184 | Zahrat Azzaytoune | Tangier, Morocco | leather |

| 185 | Cooperative Al Quaadiouiat | Tangier, Morocco | leather |

| 186 | Maroc Cop | Marrakesh, Morocco | leather |

| 187 | Masrara | Casablanca, Morocco | leather |

| 188 | Aoufouss Ghofouss | Agadir, Morocco | leather |

| 189 | Damaskina | Rabat, Morocco | leather |

| 190 | Coopertive Al Amal Azrou | Fes, Morocco | leather |

| 191 | Bodour al Atae | Casablanca, Morocco | leather |

| 192 | Cooperative Feminine Addoha | Oujda, Morocco | leather |

| 193 | Cooperative Slama | Marrakesh, Morocco | leather |

| 194 | Cooperative Soffi | Casablanca, Morocco | leather |

| 195 | Cooperative Tadfouyt | Marrakesh, Morocco | leather |

| 196 | Cooperative Yacout | Marrakesh, Morocco | leather |

| 197 | Cooperative Yamna | Rabat, Morocco | leather |

| 198 | Cooperative Ait Maten | Marrakesh, Morocco | leather |

| 199 | Cooperative Al Yassemine | Casablanca, Morocco | leather |

| 200 | Cooperative Al Ahl | Rabat, Morocco | leather |

| 201 | Cooperative Tazouknite | Agadir, Morocco | leather |

| 202 | Al Ismailya | Fes, Morocco | leather |

| 203 | Cooperative Arij | Marrakesh, Morocco | leather |

| 204 | Arij Al Ghaba | Marrakesh, Morocco | leather |

| 205 | Assal Chifae | Tangier, Morocco | leather |

| 206 | Bassatine Al Gharb | Rabat, Morocco | leather |

| 207 | Haidach | Marrakesh, Morocco | leather |

| 208 | Manahil Souss | Agadir, Morocco | leather |

| 209 | Cooperative Nour | Tangier, Morocco | leather |

| 210 | Gie Merguita Agdz | Marrakesh, Morocco | leather |

| 211 | Cooperative Ayadi Arrahma | Rabat, Morocco | leather |

| 212 | Cooperative Igran | Marrakesh, Morocco | pottery |

| 213 | Cooperative Ittihad | Rabat, Morocco | pottery |

| 214 | Jnan Rif | Oujda, Morocco | pottery |

| 215 | GIE Dar Azzaafrane | Marrakesh, Morocco | pottery |

| 216 | GIE Difat Ziz | Agadir, Morocco | pottery |

| 217 | GIE Jennane Ouezzane | Tangier, Morocco | pottery |

| 218 | Al Jaouda | Rabat, Morocco | pottery |

| 219 | Al Massira | Casablanca, Morocco | pottery |

| 220 | Cooperative Aloabiden | Casablanca, Morocco | pottery |

| 221 | Cooperative Fogoug | Marrakesh, Morocco | pottery |

| 222 | Cooperative hajja Fatiha | Rabat, Morocco | pottery |

| 223 | Imi Ouguerd | Agadir, Morocco | pottery |

| 224 | Manahil Bni Znassen | Oujda, Morocco | pottery |

| 225 | Ounzine | Tangier, Morocco | pottery |

| 226 | Rayhane Attabiaa | Marrakesh, Morocco | pottery |

| 227 | Sakr Rif | Oujda, Morocco | pottery |

| 228 | Tawanza Cop | Agadir, Morocco | pottery |

| 229 | Tirit | Agadir, Morocco | pottery |

| 230 | Lameta Fes | Fes, Morocco | pottery |

| 231 | Cooperative Abbouch | Tangier, Morocco | pottery |

| 232 | Tamaynout | Agadir, Morocco | pottery |

| 233 | Cooperative Ahl Jaid | Casablanca, Morocco | pottery |

| 234 | Arganium | Marrakesh, Morocco | pottery |

| 235 | Assil Ouargane | Marrakesh, Morocco | pottery |

| 236 | Cooperative Fritissa | Casablanca, Morocco | pottery |

| 237 | Cooperative Lhouafi | Casablanca, Morocco | pottery |

| 238 | Cooperative Nour Et Najah | Rabat, Morocco | pottery |

| 239 | Taitmatine | Marrakesh, Morocco | pottery |

| 240 | Wahat Tighmert | Guelmim, Morocco | pottery |

| 241 | GIE Ain Aicha | Fes, Morocco | pottery |

| 242 | GIE Mahjoub Zraib | Casablanca, Morocco | pottery |

| 243 | GIE Union Nfis | Casablanca, Morocco | pottery |