Abstract

Inspired by the discontinuation of the blockchain platform TradeLens, co-developed by IBM and Maersk, due to the lack of the involved supply chain stakeholders’ adoption, a critical literature review on the models of supply chain stakeholders’ adoption of blockchain applications was conducted. This review is significant as it provides insights into the exploration of a more universal approach to investigate which factors really influence blockchain adoption, which is a pre-requisite for the technical sustainability of blockchain technology in supply chains. As observed in the review, the technology acceptance model (TAM), the technology–organization–environment (TOE) framework, and the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) are frequently used in the literature, but little attention has been paid to whether blockchain technology fits the users’ tasks in understanding blockchain adoption in the supply chain. Among the technology adoption theories, task–technology fit (TTF) considers whether a technology fits the tasks, but only two previous studies involved the use of TTF. This study discusses the suitability of these existing models of technology adoption for blockchain applications in supply chains and comes up with a new unified model, namely TOE-TTF-UTAUT. This review also has implications for a more appropriate conceptual research design using mixed methods.

1. Introduction

Supply chain management covers cumbersome processes as it involves tremendous transactions, information and document flows, currency exchange, logistics, and supply chain activities that require collaboration among supply chain stakeholders (e.g., suppliers, insurance companies, banks, forwarders, and customers) [1]. In these regards, secure transmissions, tracking of goods and services, information sharing, and trust among the supply chain stakeholders are important in supply chain management. Blockchain technology, which was initially created for the cryptocurrency Bitcoin in 2008 [2], has been applied to supply chain management to ensure secure transactions, product tracking, information sharing, and trust building among supply chain stakeholders [3].

The initial blockchain for Bitcoin is categorized as permissionless (or public) blockchain which is open to all, decentralized, transparent, and anonymous. With the decentralization feature, replicas of transactional records are distributed and shared among the parties involved in the transactions without control and administration by a central authority in the blockchain network. With the transparency feature, immutable transactional records stored in the blockchain are accessible by the public and validated through the consensus mechanism by the parties maintaining the blockchain. The anonymity feature prevents disclosure of the blockchain users’ identities through cryptographically derived addresses.

Since the launch of the Hyperledger Project in December 2015, an infrastructure for permissioned (or private) blockchain referred to as Hyperledger Fabric has been developed. In contrast with permissionless blockchain, a permissioned blockchain is closed with accessibility control. Only the designated parties approved by the blockchain consortium can join the permissioned blockchain network, execute transactions, and access the transactional records stored in the blockchain. The permissioned blockchain is partially decentralized as it allows replicas of transactional records to be maintained by the members of the blockchain consortium. The blockchain consortium can decide whether the blockchain users can remain anonymous and decide whether the public can access the transactional records stored in the blockchain. These features of the permissioned blockchain facilitate supply chain management. In this connection, with the advent of Hyperledger Fabric, permissioned blockchain applications in supply chains have been growing.

As noted by Charles et al. [4], many scholars have been investigating how blockchain features such as security, decentralization, immutability, and transparency bring benefits to supply chain management. For example, Park and Li [5] reported how adopting Hyperledger Fabric for collaboration between Walmart and its suppliers to ensure confidentiality, authenticity, and nonrepudiation to all transactions led to food traceability and safety as well as information sharing and trust among the supply chain stakeholders in food distribution. Also, the analytical models by Ullah et al. [6] showed that the benefits of blockchain adoption in the after-sales service supply chain include gaining consumers’ trust, which leads to increased sales and profits for manufacturers and retailers. Moreover, Pontis et al. [7] found through a questionnaire, literature review, and interviews that blockchain technology improves supply chain capabilities including the ability to react to uncertainty in supply chains. Some other scholars have used theories to explore the benefits of blockchain deployment in supply chain management. For example, Madhani [8] used Wernerfelf’s [9] resource-based view (RBV) to demonstrate the capabilities and benefits of blockchain deployment in the supply chain. Also, Patil et al. [10] used network theory (NT) to reveal that the supply chain collaboration and learning of an organization positively influence its blockchain assimilation, and perceived network prominence of an organization moderates the influence of supply chain learning on its blockchain assimilation. Moreover, Meier et al. [11] used Teece et al.’s [12] dynamic capabilities to demonstrate that supply chain traceability and related sensing capabilities are benefits of blockchain-driven circular supply chain management while Treiblmaier [13] presented a framework built on principal agent theory (PAT), transaction cost analysis, RBV, and NT which provides the foundation for further systematic and theory-based research for the exploration of blockchain applications in supply chains.

However, the recent discontinuation of the blockchain platform TradeLens, co-developed by IBM and Maersk to process and track shipment records and enable the involved supply chain stakeholders (e.g., suppliers, forwarders, insurers, government agencies, cargo owners, ports operators, and customers) to interact efficiently and share information for supply chain management, was due to the lack of acceptance and adoption of the involved supply chain stakeholders [14]. For the case of the discontinuation of TradeLens, two issues were noticed. First, for efficient information sharing and interaction, the users of TradeLens might not have needed the blockchain technology. Other existing Internet technologies, such as three-tier or multi-tier server-client systems and cloud computing, can provide efficient information sharing and interaction. For example, those users can obtain the required information from a web database through a web server in a three-tier architecture, multi-tier architecture, or cloud storage from the involved supply chain stakeholders (e.g., suppliers, forwarders, insurers, and customers) instead of the blockchain-based TradeLens. Also, some suppliers may not want to share information with their competitors through the blockchain-based TradeLens. Therefore, these TradeLens users did not regard the blockchain features as useful. Second, the factors influencing the TradeLens users’ acceptance of blockchain technology, especially whether the blockchain features (e.g., decentralization, shareability, and transparency) fit the users’ performance needs, must be understood.

1.1. Significance of This Study

Inspired by this discontinuation of the blockchain application in supply chain management, the researchers had concerns about the applicability of the existing blockchain adoption models and proposed this study to explore a more appropriate model. The blockchain adoption models in the literature lack consideration of whether the blockchain technology fits the users’ performance needs. In this study, a new blockchain technology adoption model that considers whether the technology fits the uses’ needs is explored to investigate which factors really affect the acceptance and actual adoption of blockchain applications for supply chain management. Nowadays, technological development and advancement are important for a community to sustain itself. Therefore, technical sustainability, which refers to the practices required to maintain the smooth running of the technology, leading the technology to advance, and keep the technology resilient [15], must be explored. For a form of technology to keep on operating and advancing, that technology must first be accepted and adopted by the technology users. The study of supply chain stakeholders’ adoption of blockchain applications is significant as that adoption is a pre-requisite for the technical sustainability of blockchain applications for supply chain management. Also, this study is significant in the sense that it has implications for a blockchain adoption model that considers whether blockchain technology fits supply chain stakeholders’ tasks. This model can be used to understand which factors really affect blockchain adoption in supply chains and determine which supply chain applications need blockchain.

1.2. Research Aims and Questions

For the exploration of blockchain technology adoption for supply chain management, previous studies in this area should be reviewed. This study aims to critically review the existing studies related to blockchain technology adoption for supply chain management with the intention to obtain insights from the literature and propose a more universal approach with a more appropriate theoretical model for future research on factors influencing blockchain adoption in supply chain management. The review mainly focuses on the previous studies about users’ adoption of permissioned blockchain in supply chains as many blockchain-based supply chain applications are built on permissioned blockchains. To cover the related literature, the review also considered previous studies about the adoption of permissionless blockchain in supply chains and the previous studies in this area that did not explicitly state which blockchain type was used.

The concerns about the literature are how the previous studies were conducted to explore the factors affecting blockchain adoption for supply chain management and what factors were found in the literature. To this end, the following research questions are addressed to explore the factors affecting blockchain adoption in supply chains:

- What are the research methods used in the literature?

- What are the theories or models adopted in the literature?

- What are the findings in the literature?

- What are the insights or implications in terms of research design and blockchain adoption theories or models obtained from research questions 1 to 3?

1.3. Related Research Work

Eight relevant previous literature review articles were identified, i.e., Refs. [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. All eight articles are systematic literature reviews. The studies by AlShamsi et al. [16] and Taherdoost [17] are similar—they both reviewed the blockchain adoption models and the domains or business sectors that these adoption models were applied to. In addition to reviewing the blockchain adoption models, Xie et al. [18] reviewed research methods while AlShamsi et al. [16] reviewed the research methods, primary purpose, and target participants in previous studies. Moreover, in addition to reviewing the factors affecting blockchain adoption, Happy et al. [19] and Xie et al. [18] considered the outcomes of blockchain adoption. Similarly, many previous literature reviews (e.g., Refs. [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]) have looked into the benefits brought about by blockchain adoption in the supply chain. Kafeel et al. [23], Shin et al. [21], and Vu et al. [22] also investigated the barriers or challenges that influence the adoption of blockchain technology. Mohammed et al. [20] explored all three areas (i.e., factors, benefits, and challenges) pertaining to blockchain adoption. Unlike the studies by AlShamsi et al. [16] and Taherdoost [17], which focused on different business sectors (e.g., education, finance, healthcare, and supply chain), Happy et al. [19], Kafeel et al. [23], Mohammed et al. [20], Shin et al. [21], Vu et al. [22], and Xie et al. [18] focused solely on the supply chain sector.

Significantly, while previous studies conducted systematic literature reviews, this study took a critical approach to conduct a literature review on the research methods, main technology adoption theories or models, and factors affecting the use of blockchain with the intention to provide information for what the future research design on blockchain adoption for supply chain management should be. Based on this critical literature review, a conceptual framework was formulated.

1.4. Commonly Used Theoretical Models

Based on the relevant literature review studies, there is a large variety of blockchain technology adoption models for supply chain management identified in the literature. These models include Tornatzky et al.’s [29] technology–organization–environment (TOE) framework, Davis’ [30] technology acceptance model (TAM), Venkatesh et al.’s unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) [31] and extended UTAUT (UTAUT2) [32], Parasuraman’s [33] technology readiness index (TRI), Goodhue and Thompson’s [34] task–technology fit (TTF), DeLone and McLean’s [35] information systems success (ISS) model, institutional theory (IT) [36,37], Westaby’s [38] behavioral reasoning theory (BRT), Koppenjan and Groenewegen’s [39] institutional framework (IF), Pfeffer and Salancik’s [40] resource dependency theory (RDT), hesitant fuzzy set (HFS) [41,42], social network theory (SNT) [43], and Ram and Sheth’s [44] innovation resistance theory (IRT). As identified in the relevant literature review studies, TOE, TAM, and UTAUT were commonly used. Many previous studies used their extended or integrated versions.

1.4.1. Technology–Organization–Environment Framework

The TOE framework consists of constructs in the technological (T), organizational (O), and environmental (E) contexts that explore how an organization adopts technology and implements technological innovations. The T context refers to the technological issues relevant to an organization such as technology features and infrastructure. The O context contains the constructs of an organization such as organizational structure, financial status, and size. The E context refers to the constructs surrounding an organization such as dealings with suppliers, partners, competitors, and the government. The TOE framework examines the T, O, and E constructs from an organizational perspective [45,46]. This framework does not strictly fix any constructs in each of the three contexts (i.e., T, O, and E contexts). Instead, as different organizations may have different constructs in the T, O, and E contexts, this framework provides flexibility for setting constructs in the T, O, and E contexts for different organizations. For example, the E constructs include perceived industry pressure and perceived government pressure for small businesses in Hong Kong [47] while Internet competitive pressure, website competitive pressure, and e-commerce competitive pressure were set in the E context for small firms in Portugal [48].

1.4.2. Technology Acceptance Model

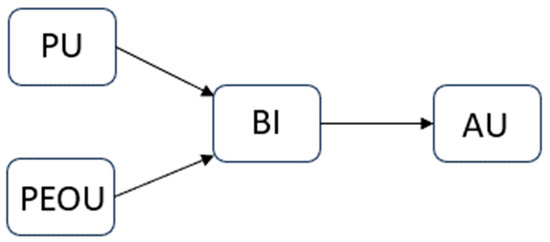

In the TAM, a user’s actual usage (AU) of technology is influenced by that user’s behavioral intention (BI) to use that technology. A user’s BI is in turn influenced by that user’s perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU). PU is “the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would enhance job performance” [30]. PEOU is “the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would be free from effort” [30]. As indicated in the TAM, if the blockchain-based system is easy to use and makes a user perform well, that user is more likely to use the blockchain-based system and, eventually, will actually use the system. Figure 1 visualizes the TAM. The arrow indicates an influence in the figure.

Figure 1.

Davis’ [30] TAM.

1.4.3. Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology

UTAUT was formulated through a review and synthesis of eight theories/models. These eight theories/models are Fishbein and Ajzen’s [49] theory of reasoned action (TRA), TAM, the motivational model (MM) [50,51], the theory of planned behavior (TPB) [52,53], Taylor and Todd’s [54] combined TAM and TPB, Thompson et al.’s [55] model of personal computer utilization (MPCU), Rogers’ [56] innovation diffusion theory (IDT)/diffusion of innovation (DOI), and social cognitive theory (SCT) [57,58]. UTAUT contains moderating (or indirect) effects (i.e., gender, age, experience, and voluntariness of use), but they are not usually examined in the literature as the previous studies intended to obtain findings that could be applicable to any gender and any age, and as expected, there was not much difference in the experience of using such a new form of blockchain technology and the voluntariness of use as the users were supposed to use the technology which had been adopted in their organizations.

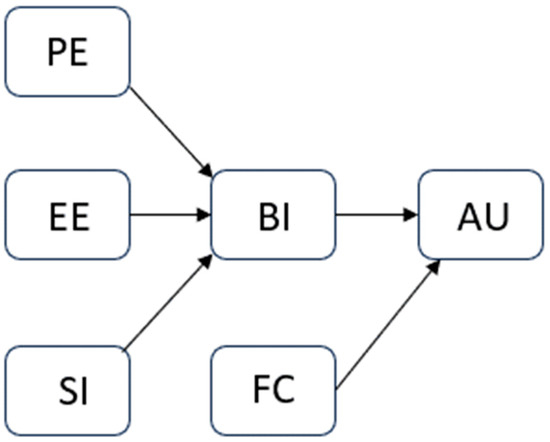

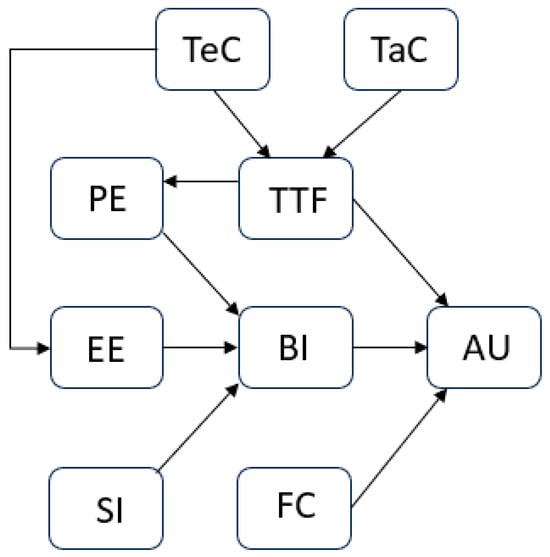

As theorized by UTAUT, supply chain stakeholders’ adoption of blockchain technology is indicated by their AU behavior of that technology which is determined by their BI to use that technology and facilitating conditions (FC) such as Internet access, required software and hardware, technical support, and training. The users’ BI is in turn determined by their own three perceptions—(1) performance expectancy (PE), which is similar to PU in the TAM, is the degree of the users’ belief that using blockchain technology can enhance their task performance (e.g., auditable transactions and efficient product tracking), (2) effort expectancy (EE), which is similar to PEOU in the TAM, is the degree of the users’ perception of their digital literacy, self-efficacy, and ease of use of blockchain technology, and (3) social influence (SI), which is the extent to which the users perceive that the people around them such as suppliers, supervisors, colleagues, partners, and customers expect that they should perform the blockchain technology usage behavior. Figure 2 shows UTAUT without moderating effects. Again, the arrow indicates an influence in the figure.

Figure 2.

Venkatesh et al.’s [31] UTAUT without moderating effects.

2. Research Methodology

This study applied a critical review approach. According to Jesson and Lacey [59], a critical review should demonstrate awareness of the current state of knowledge, as well as strengths and limitations of the current literature, while a systematic review uses a systematic method to identify relevant studies in order to minimize biases and error. Both critical and systematic reviews should have with implications that lead to a new state of knowledge. The critical literature review processes are described in the following subsections:

2.1. Literature Search

First, the following inclusion criteria were set for the literature search:

- Studies published in books, journals, and conference proceedings from 2013 (the year in which the publications about blockchain adoption in the supply chain began [28]) to 2023 (the year when this literature search was conducted) in English

- Studies about blockchain adoption, acceptance, or use for supply chain management

- Studies related to theories, models, or frameworks for blockchain adoption, acceptance, or use

The search terms derived from the inclusion criteria included “blockchain”, “adoption”, “acceptance”, “use”, “supply chain”, “theories”, “models”, “frameworks”, “English”, and “from 2013 to 2023”. These search terms were concatenated with some logical operators for the literature search through the Scopus search tool. Scopus was mainly used as it covers different areas (e.g., business, science, and supply chain) more comprehensively [60] and provides a friendly user interface that facilitates searching [14]. In the literature search using Scopus, the search string TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Blockchain” AND (“adoption” OR “acceptance” OR “use”) AND (“theories” OR “models” OR “frameworks”) AND “supply chain”) AND (LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2023) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2022) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2021) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2020) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2019) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2018) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2017) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2016) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2015) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2014) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2013)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”)) was used to search through the article title, abstract, and keywords. Then, 1177 articles were found.

2.2. Search Results

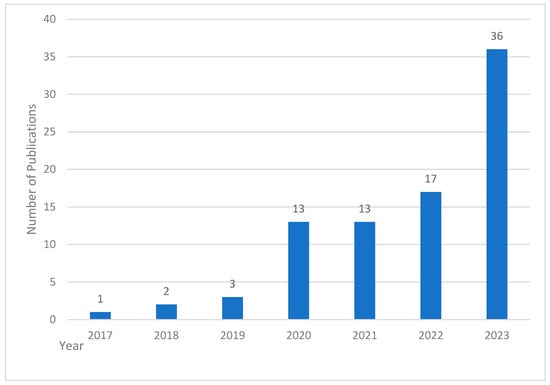

Among the search results, only the results related to blockchain technology were reviewed. After reviewing these search results and recursively searching the articles from the reference lists from literature review articles (e.g., Refs. [16,17,19]), a total of 85 relevant previous studies published from 2017 to 2023 were found. Figure 3 shows the number of relevant articles published in each year from 2017 to 2023. There is a trend of an increasing number of publications, reflecting growing attention to studies about blockchain adoption in supply chains. For research questions 1 to 3, each article from the search results is divided into five fields. The five fields are the source, reference model/theory, data collection method, analysis type, and major findings. These articles published from 2017 to 2023 are listed in Table 1 (a) to (g).

Figure 3.

Publications from 2017 to 2023.

Table 1.

(a) Previous studies on blockchain adoption published in 2017; (b) previous studies on blockchain adoption published in 2018; (c) previous studies on blockchain adoption published in 2019; (d) previous studies on blockchain adoption published in 2020; (e) previous studies on blockchain adoption published in 2021; (f) previous studies on blockchain adoption published in 2022; (g) previous studies on blockchain adoption published in 2023.

The search results were analyzed with reference to the technology adoption theories or models involved in the studies. Those theories or models were either solely adopted, extended, or combined with other theories or models to form integrated frameworks. Among the technology adoption theories, models, or methods used to form models, as shown in Table 2, the TOE was the most frequently used with 33 studies, followed by the TAM with 16 studies, and then followed by the UTAUT with 14 studies.

Table 2.

The number of blockchain adoption theories/models/methods in the literature.

Table 3 shows that survey was the most common method used to collect data by the researchers on blockchain adoption in supply chain, as indicated by it representing 57.7% (60/104) of all data collection methods. Also, survey methods were frequently used in each period from 2017 to 2023.

Table 3.

The number of data collection methods in the literature from 2017 to 2023.

In Table 4, the quantitative analysis type was the main analysis type, as indicated by 72.9% (62/85) of all analysis types commonly used in each period from 2017 to 2023.

Table 4.

The number of analysis types in the literature from 2017 to 2023.

Unlike the TAM and UTAUT in which the constructs are predefined, the constructs for TOE were determined by the researchers. Table 5 shows the identified constructs in each TOE context that have a significant effect on blockchain adoption in supply chains.

Table 5.

TOE constructs identified in the literature.

In Table 5, for the T context, compatibility is defined as the “degree to which innovation fits with the potential adopters’ existing values, previous practices, and current needs” [157]; complexity refers to the “degree to which an innovation is perceived to be relatively difficult to understand and use” [157]; the relative advantage is the “degree to which an innovation is perceived as being better than the idea it supersedes” [158], including the benefits brought about by blockchain technology such as traceability and cost saving [74].

For the O context, management support is the extent to which the management of an organization supports adopting a technology. Organizational readiness is the availability of an organization’s resources used to adopt a technology [103]. This includes technology readiness which is related to technology resources (e.g., technology infrastructure, the software required, and employees’ technology knowledge and skills) of an organization, including know-how and culture [159]. It is unclear in the literature about the categorization of the construct of technology readiness. Some scholars (e.g., Tasnim et al. [149]) categorize technology readiness into the T context while some other scholars (e.g., Deng et al. [107]) put technology readiness into the O context. As technology readiness involves the use of an organization’s resources (e.g., premises for building technology infrastructure and organization structure’s technology expertise), technology readiness should be classified into the O context. Absorptive capability is an organization’s “ability to recognize the value of new information, assimilate it, and apply it to commercial ends” [160]. Financial resources are the costs used by an organization to implement a technology. Prior studies found that large firms are more willing to adopt new technology [161] as they have a stronger ability to bear risk [109]. In this regard, firm size can affect blockchain adoption. The study by Mendling et al. [162] confirmed that firm size is an essential determinant of blockchain adoption.

For the E context, competitive pressure is an organization’s perceived pressure from its competitors, especially the competitors’ fast advancing with the advent of new technologies. As found by Queiroz and Wamba [69], blockchain adoption depends on trading partners’ willingness and cooperation, resulting in blockchain implementation in an organization due to its trading partners’ pressure. As found by Zhu et al. [163], government policy and support can regulate and monitor new technology usage by an organization, which can be a driver or barrier to blockchain adoption [109]. Blockchain technology is a network that requires collaboration among supply chain stakeholders. Therefore, Stakeholders’ cooperation influences the use of that technology. Vendor support includes security controls, data availability, user training, and technical support [96], which can positively influence users’ intention to adopt a technology [46].

2.3. Critical Review

For research question 4, the literature was critically reviewed to highlight two critical points about blockchain adoption theories or models. First, the individual-level blockchain adoption theories should be combined with the organization-level blockchain adoption theories. In the literature, the TAM and UTAUT were frequently used to explore the factors affecting a supply chain individual’s blockchain adoption while TOE was usually used to explore those factors at an organizational level. Although categorizing the TAM and UTAUT at the individual level and TOE at the organization level is a general practice in the literature, these two-level theories were applied at an individual level, as the surveys and interviews were conducted to obtain perceptions from an individual perspective. Also, the integration of the organization-level theory and the individual-level theory facilitates the gathering of better views on blockchain adoption as an individual may also be concerned about organizational elements (e.g., management support, organizational readiness, knowledge absorption capability, and financial resources) while an organization may also have a view of individual components (e.g., performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and social influence). Moreover, combining theories can achieve a better understanding of the technology adoption phenomenon [164]. Therefore, unifying the individual-level theory and the organization-level theory is feasible.

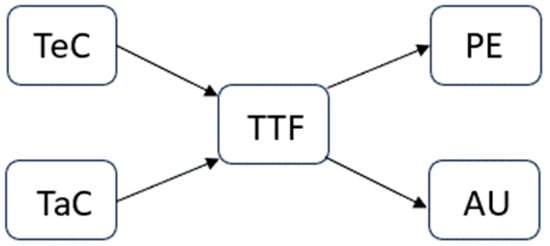

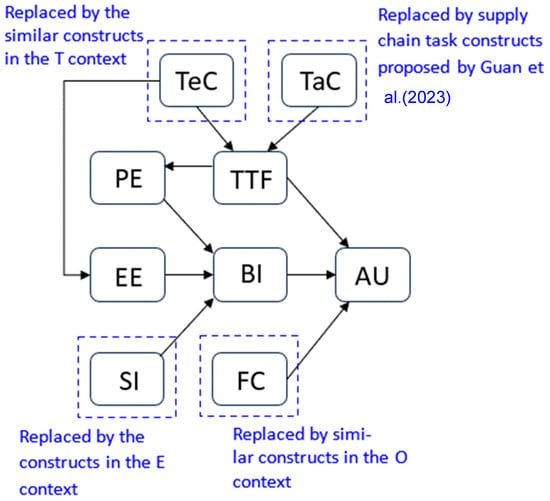

Second, the TAM, UTAUT, and TOE are frequently used in the literature, but little attention has been paid to whether blockchain technology fits the users’ tasks in understanding blockchain adoption in the supply chain. Among the technology adoption theories, TTF considers whether a technology fits the tasks to be performed [34]. It was found in the literature that only two studies (i.e., Refs. [89,145]) involved the use of TTF. TTF should be applied as the mere acceptance and utilization of blockchain technology as TAM and UTAUT cannot guarantee better performance in supply chain management. For example, users cannot perform computations well with the use of a word processing app as the capabilities and features of the word processor do not fit the computation tasks. TTF theorizes that task characteristics (TaC) and technology characteristics (TeC) determine the task–technology fit (TTF) construct, which reflects the extent to which the technology fits the task. The TTF construct in turn leads to the user’s actual usage (AU) of that technology and affects the user’s task performance expectancy (PE). Figure 4 shows the constructs and the influences, as indicated by the arrows, among these constructs in TTF.

Figure 4.

Goodhue and Thompson’s [34] TTF.

Furthermore, this review sheds light on a critical issue regarding research design in the literature. Most of the previous studies performed quantitative research such as surveys and quantitative analyses while some previous studies adopted a qualitative approach such as interviews and qualitative analyses. Few studies used a research design that employed mixed methods, which combines and integrates a quantitative approach and a qualitative approach into a single research design.

Mixed methods are recommended for three reasons. First, the mixing of a quantitative method and a quantitative method exhibits the benefits of both methods—the weakness of generalizing the findings from the data of a smaller sample size in a qualitative method can be compensated by the findings from the data of a larger sample size in a quantitative method while the problem of obtaining detailed explanations from a larger sample size in the quantitative method can be solved by the analytical findings of the in-depth interview transcripts from a smaller sample size in the qualitative method. Most of the previous studies on blockchain adoption in the supply chain used a quantitative method in which there is difficulty in explaining the quantitative results. For example, as the empirical research by Queiroz and Wamba [69] found different effects of factors on blockchain adoption in different countries (i.e., India and the USA), a qualitative method could be integrated into this study to explore explanations of the cultural differences as well as environmental and political factors pertaining to blockchain adoption in the supply chain in different countries.

Second, qualitative approaches can provide more insights into the cause–effect relationships found by quantitative approaches [16] and confirm the factors for blockchain adoption in the supply chain found using quantitative approaches. It was found from the literature that many studies have explored the drivers of blockchain adoption in the supply chain while some other studies (i.e., the studies by Kumar Bhardwaj et al. [96], Agrawal et al. [104], Oguntegbe et al. [117], and Yadav et al. [154]) have explored the barriers to blockchain adoption in the supply chain. The constructs in the commonly used the TAM and UTAUT were usually operationalized and measured with the Likert scale using a quantitative method in the literature. For example, a construct in UTAUT was measured with a 5-point Likert scale (5 means strongly agree, 4 means agree, 3 means neutral, 2 means disagree, and 1 means strongly disagree); then, the options 1 and 2 for a construct in UTAUT can mean that the construct is a driver with less effect, no effect, or a barrier to technology adoption. Therefore, a qualitative interview could be conducted to confirm the cause–effect relationship and determine whether the construct represents a factor, no effect, or a barrier. Malik et al. [75] used interviews to confirm the positive (i.e., driver), unsure, and negative (i.e., barrier) impact of the TOE constructs.

Third, a qualitative approach can be used to explore the potential factors for determining TOE constructs for a quantitative approach to measurement. As the TOE framework allows for flexibility in setting a construct in the T, O, or E context and operationalizing the construct as a driver or barrier, content analyses of the in-depth interviews or supply chain documents can help to identify the potential factors for setting TOE constructs in the TOE-TTF-UTAUT model.

Moreover, as the previous studies related to blockchain adoption models investigated the factors on or barriers to blockchain adoption from the respondents’ perspectives, the findings of these studies depend highly on the respondents’ understanding of blockchain features. As noted from the literature review, many of these previous studies did not specify any attempt to understand how the respondents understood the blockchain features.

3. Discussions and Implications

To explore the antecedents of blockchain adoption in supply chains, UTAUT was considered since it was developed as a modified version through review and consolidation of some other models including the TAM. Having known that the blockchain adoption model should examine whether blockchain technology fits the users’ tasks, TTF was integrated into the blockchain adoption model. With reference to the models related to TTF integration presented by Marikyan and Papagiannidis [165], the TTF-UTAUT model was formulated, as shown in Figure 5 in which PE and AU are common constructs in both TTF and UTAUT, TeC, TaC, and TTF are constructs only in TTF, and EE, BI, SI, and EE are constructs only in UTAUT. Also, there is an influence of TeC on EE as technology characteristics such as user interface can affect a user’s perceived use of the technology. Therefore, the influence of TeC on EE was added to Figure 5.

Figure 5.

TTF-UTAUT model.

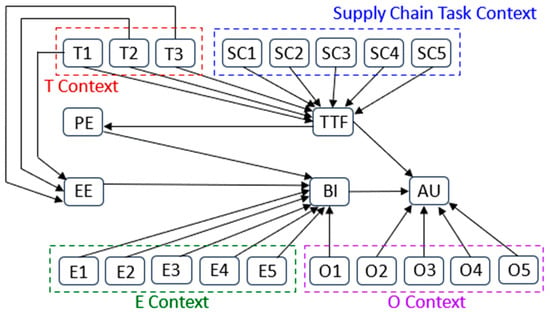

When considering the integration of TOE and TTF-UTUAT, some similar constructs between TOE and TTF-UTAUT were noted. As shown in Figure 6, the constructs in the T context are similar to TeC, the constructs in the O context can be regarded as FC, and SI is a part (or subset) of the E context. Guan et al.’s [133] proposed supply chain factors are equivalent to TaC. In these regards, a new TOE-TTF-UTAUT model, as shown in Figure 6, was formed for the exploration of the antecedents of blockchain adoption in supply chains. The dashed boxes labeled with supply chain task context, T context, O context, and E context indicate that the constructs inside these boxes are not fixed. Those constructs can be determined and changed under different cases (e.g., different users, different organizations, or different situations at different stages).

Figure 6.

Integrating TOE into TTF-UTAUT [133].

In line with the findings from AlShamsi et al. [16], most of the previous studies depended on the views of management, experts, and consultants at an organizational level. The constructs set in the TOE-TTF-UTUAT model in Figure 7 were based on an organizational perspective. As the TOE-TTF-UTAUT model can be applied at different levels, the individual users’ perspectives should also be considered by using a qualitative approach using interviews with the supply chain stakeholders, analyses of the interview transcripts and the supply chain documents, and a literature review on TOE constructs. The supply chain task constructs can also be identified using this qualitative approach.

Figure 7.

TOE-TTF-UTAUT model.

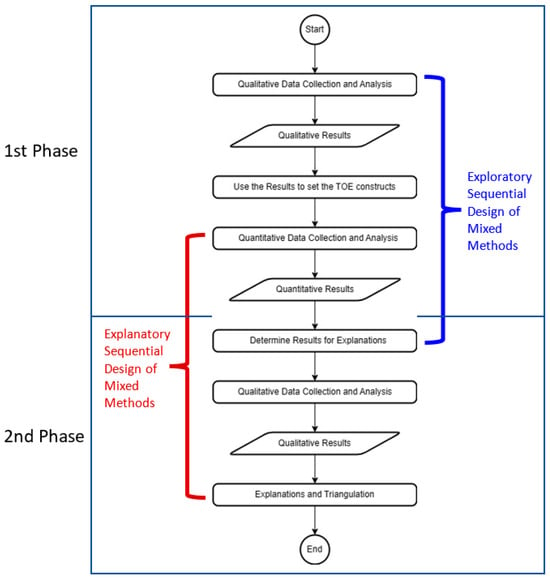

When adopting the TOE-TTF-UTAUT model in a study, first, seminars on blockchain applications and their features for participants can be organized to ensure that the participants understand the blockchain features. Right after the seminars, two phases of research using mixed methods can be carried out. In the first phase, Creswell and Gutterman’s [166] exploratory sequential design of mixed methods can be performed. In this design, a qualitative approach is followed by a quantitative approach. For the study on blockchain adoption in supply chains, once the TOE constructs and the supply chain task constructs, which are like the constructs in the dashed boxes in Figure 7, are determined using a qualitative approach and integrated into the TOE-TTF-UTAUT model, a quantitative approach using a survey and quantitative analyses can be conducted to investigate the factors affecting blockchain adoption in supply chains.

In Figure 7, the T context contains compatibility (T1), complexity (T2), and relative advantage (T3). In addition, the relevant characteristics of blockchain technology such as shareability, immutability, traceability, and transparency should be incorporated into T3 as a relative advantage. With the use of these measurement items for the blockchain features, whether a blockchain operation such as sharing a replica of a transaction among the involved supply chain stakeholders in the blockchain network fits the stakeholders’ task requirements is evaluated. The O context contains management support (O1), absorptive capability (O2), organizational readiness (O3), financial resources (O4), and firm size (O5). The E context contains competitive pressure (E1), trading partners’ pressure (E2), government policy and support (E3), stakeholders’ cooperation (E4), and vendor support (E5).

In the second phase, Creswell and Gutterman’s [166] explanatory sequential design of mixed methods, in which a quantitative approach is followed by a qualitative approach, is used. In this design, the findings from the quantitative approach in the first phase are used and reviewed for follow-up via qualitative interviews to obtain explanations. After that, both the quantitative and qualitative findings in this second phase can be used for triangulation. This proposed research of mixed methods using exploratory sequential design followed by explanatory sequential design is presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

The proposed research of mixed methods.

4. Concluding Remarks and Future Work

As observed from the critical literature review on antecedents of blockchain adoption in supply chains, TAM, TOE, and UTAUT are commonly used, but these models did not consider the important issue of whether blockchain technology fits the supply chain tasks. Also, the literature has paid little attention to this technology fit issue, as only two previous studies involved the use of TTF which considers whether a technology fits the tasks. Moreover, most of the previous studies distinguish organization-level TOE from individual-level UTAUT. In these regards, insights into exploration of a more universal approach to investigate factors that influence supply chain stakeholders’ blockchain adoption were obtained. The insights include the suitability of incorporating TTF into a blockchain adoption model, the possibility of combining the organization-level technology adoption theory with the individual-level technology adoption theory, and the applicability of a more appropriate conceptual research design using a mixed method.

Significantly, for future research directions on blockchain adoption in the supply chain, this review study provides a recommendation that includes the new unified technology adoption model, namely, TOE-TTF-UTAUT, and the research design using mixed methods for the exploration of the antecedents of blockchain adoption in supply chains. As the TOE-TTF-UTAUT model contains theories targeted at different levels (i.e., organization level and individual level), the TOE-TTF-UTAUT model is applicable to any level in an organization to have a broader view for understanding blockchain adoption in the supply chain. The TOE-TTF-UTAUT model also contains a task–technology fit component which is more appropriate for the study of technology adoption. For the application of the TOE-TTF-UTAUT model, the proposed research involving mixed methods using exploratory sequential design followed by explanatory sequential design is suitable for setting TOE and task constructs and exploring factors affecting technology adoption.

This study can be extended in three ways. First, the Scopus search tool was mainly used in this study. This review study can be extended to search for any relevant studies that may be found by other search engines (e.g., Emerald, IEEE, MAPI, Springer, and Web of Science). Second, this study reviewed previous studies written in English only. For better coverage of the relevant literature, studies in other languages should also be explored. Third, the TOE-TTF-UTAUT model proposed in this study is a conceptual model, further studies are required to validate the constructs in the TOE-TTF-UTAUT model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.W.; methodology, S.W., J.K.W.Y. and Y.-Y.L.; validation, J.K.W.Y.; investigation, S.W., J.K.W.Y. and R.K.; resources, Y.-Y.L.; data curation, Y.-Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.W.; writing—review and editing, J.K.W.Y., Y.-Y.L., T.K. and R.K.; visualization, S.W. and J.K.W.Y.; supervision, S.W. and T.K.; project administration, Y.-Y.L. and T.K. All authors did not use generative artificial intelligence (AI) and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process of this paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The publication of this research was partially funded by the College of Professional and Continuing Education of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this review are available from the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

Abbreviations used in this article are shown as follows:

| AHP | Analytical Hierarchy Process |

| AU | Actual Usage |

| BI | Behavioral Intention |

| BRT | Behavioral Reasoning Theory |

| CPT | Cumulative Prospect Theory |

| DEMATEL | Decision-Making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory |

| DOI | Diffusion of Innovation |

| EE | Effort Expectancy |

| FC | Facilitating Conditions |

| HFS | Hesitant Fuzzy Set |

| IDT | Innovation Diffusion Theory |

| IF | Institutional Framework |

| IT | Institutional Theory |

| IRT | Innovation Resistance Theory |

| ISM | Interpretive Structural Modeling |

| ISS | Information Systems Success |

| MICMAC | Cross-Impact Matrix Multiplication Applied to Classification |

| MM | Motivational Model |

| MPCU | Model of Personal Computer Utilization |

| NT | Network Theory |

| PAT | Principal Agent Theory |

| PE | Performance Expectancy |

| PEEST | Political, Economic, Environmental, Social, and Technological |

| PEOU | Perceived Ease of Use |

| PFS | Pythagorean Fuzzy Sets |

| PLS-SEM | Partial Least Squares-Structural Equation Modeling |

| PU | Perceived Usefulness |

| RBV | Resource-Based View |

| RDT | Resource Dependency Theory |

| SCT | Social Cognitive Theory |

| SI | Social Influence |

| SNT | Social Network Theory |

| TaC | Task Characteristics |

| TAM | Technology Acceptance Model |

| TeC | Technology Characteristics |

| TOE | Technology–Organization–Environment |

| TPB | Theory of Planned Behavior |

| TRA | Theory of Reasoned Action |

| TRI | Technology Readiness Index |

| TTF | Task–Technology Fit |

| VIKOR | VlseKriterijumska Optimizcija I Kaompromisno Resenje |

| UTAUT | Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology |

| UTAUT2 | Extended UTAUT |

| WASPA | Weighted Aggregated Sum Product Assessment |

References

- Mou, W.M.; Wong, W.K.; McAleer, M. Financial credit risk evaluation based on core enterprise supply chains. Sustainability 2018, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, S. Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System. Bitcoin.org. 2008. Available online: https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2016).

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Singh, R.P.; Khan, S.; Suman, R. Blockchain technology applications for Industry 4.0: A literature-based review. Blockchain Res. Appl. 2021, 2, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, V.; Emrouznejad, A.; Gherman, T. A critical analysis of the integration of blockchain and artificial intelligence for supply chain. Ann. Oper. Res. 2023, 327, 7–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, A.; Li, H. The effect of blockchain technology on supply chain sustainability performances. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Ayat, M.; He, Y.; Lev, B. An analysis of strategies for adopting blockchain technology in the after-sales service supply chain. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 179, 109194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potnis, T.; Lau, Y.-Y.; Yip, T.L. Roles of Blockchain Technology in Supply Chain Capability and Flexibility. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhani, P.M. Enhancing supply chain capabilities with blockchain deployment: An RBV perspective. IUP J. Bus. Strategy 2021, 18, 7–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wernerfelt, B. A resource-based view of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, K.; Ojha, D.; Struckell, E.M.; Patel, P.C. Behavioral drivers of blockchain assimilation in supply chains—A social network theory perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 192, 122578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, O.; Gruchmann, T.; Ivanov, D. Circular supply chain management with blockchain technology: A dynamic capabilities view. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2023, 176, 103177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisani, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treiblmaier, H. The impact of the blockchain on the supply chain: A theory-based research framework and a call for action. Supply Chain Manag. 2018, 23, 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.; Yeung, J.K.W.; Lau, Y.-Y.; Kawasaki, T. A case study of how Maersk adopts cloud-based blockchain integrated with machine learning for sustainable practices. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.; Yeung, J.K.W.; Lau, Y.-Y.; So, J. Technical sustainability of cloud-based blockchain integrated with machine learning for supply chain management. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlShamsi, M.; Al-Emran, M.; Shaalan, K. A systematic review on blockchain adoption. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H. A critical review of blockchain acceptance models—Blockchain technology adoption frameworks and applications. Computers 2022, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Parry, G.; Altrichter, B. Factors influencing the implementation success of blockchain technology: A systematic literature review. In Proceedings of the International Conference on AI and the Digital Economy, Venice, Italy, 26–28 June 2023; pp. 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Happy, A.; Chowdhury, M.M.H.; Scerri, M.; Hossain, M.A.; Barua, Z. Antecedents and consequences of blockchain adoption in supply chains: A systematic literature review. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2023, 36, 629–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; Potdar, V.; Quaddus, M.; Hui, W. Blockchain adoption in food supply chains: A systematic literature review on enablers, benefits, and barriers. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 14236–14255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Wang, Y.; Pettit, S.; Abouarghoub, W. Blockchain application in maritime supply chain: A systematic literature review and conceptual framework. Marit. Policy Manag. 2023, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, N.; Ghadge, A.; Bourlakis, M. Blockchain adoption in food supply chains: A review and implementation framework. Prod. Plan. Control 2023, 34, 506–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafeel, H.; Kumar, V.; Duong, L. Blockchain in supply chain management: A synthesis of barriers and enablers for managers. Int. J. Math. Eng. Manag. Sci. 2023, 8, 15–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agi, M.A.; Jha, A.K. Blockchain technology in the supply chain: An integrated theoretical perspective of organizational adoption. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 247, 108458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dujak, D.; Sajter, D. Blockchain Applications in Supply Chain; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Paliwal, A.; Chandra, S.; Sharma, S. Blockchain technology for sustainable supply chain management: A systematic literature review and a classification framework. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamba, S.F.; Kamdjoug, J.R.K.; Bawack, R.E.; Keogh, J.G. Bitcoin, blockchain, and FinTech: A systematic review and case studies in the supply chain. Prod. Plan. Control 2018, 31, 115–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Han, J.H.; Beynon-Davies, P. Understanding blockchain technology for future supply chains: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Supply Chain Manag. 2018, 24, 62–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornatzky, L.G.; Fleischer, M.; Chakrabarti, A.K. The Processes of Technological Innovation; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.; Xu, X. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A. Technology readiness index (TRI): A multiple-item scale to measure readiness to embrace new technologies. J. Serv. Res. 2000, 2, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodhue, D.L.; Thompson, R.L. Task-technology fit and individual performance. MIS Q. 1995, 19, 213–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: A ten-year update. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 19, 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Soc. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, W.W.; DiMaggio, P.J. New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Westaby, J.D. Behavioral reasoning theory: Identifying new linkages underlying intentions and behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2005, 98, 97–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppenjan, J.; Groenewegen, J. Institutional design for complex technological systems. Int. J. Technol. Policy Manag. 2005, 5, 240–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G.R. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective, 2nd ed.; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Torra, V.; Narukawa, Y. On hesitant fuzzy sets and decision. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems, Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 20–24 August 2009; pp. 1378–1382. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, B.; Xu, Z.; Xia, M. Dual hesitant fuzzy sets. J. Appl. Math. 2012, 2012, 879629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgatti, S.P.; Li, X.U.N. On social network analysis in a supply chain context. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2009, 45, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, S.; Sheth, J.N. Consumer resistance to innovation: The marketing problem and its solution. J. Consum. Mark. 1989, 6, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awa, H.; Ojiabo, O. A model of adoption determinants of ERP within T-O-E framework. Inf. Technol. People 2016, 29, 901–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, H.; Date, H.; Ramaswamy, R. Understanding determinants of cloud computing adoption using an integrated TAM-TOE model. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2015, 28, 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuan, K.K.Y.; Chau, P.Y.K. A perception-based model for EDI adoption in small businesses using a technology-organization-environment framework. Inf. Manag. 2001, 38, 507–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.; Oliveira, T. Determinants of e-commerce adoption by small firms in Portugal. In Proceedings of the 3rd European Conference on Information Management and Evaluation, Gothenburg, Sweden, 17–18 September 2009; pp. 328–338. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation to use computers in the workplace. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 22, 1111–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R.J. Toward a hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Zanna, M., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; Volume 29, pp. 271–360. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action Control: From Cognition to Behavior; Kuhl, I.J., Beckmann, J., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P.A. Assessing IT usage: The role of prior experience. MIS Q. 1995, 19, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.L.; Higgins, C.A.; Howell, J.M. Personal computing: Toward a conceptual model of utilization. MIS Q. 1991, 15, 124–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 4th ed.; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Compeau, D.R.; Higgins, C.A. Computer self-efficacy: Development of a measure and initial test. MIS Q. 1995, 19, 189–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesson, J.; Lacey, F. How to do (or not to do) a critical literature review. Pharm. Educ. 2006, 6, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Martín, A.; Orduna-Malea, E.; Thelwall, M.; Delgado López-Cózar, E. Google scholar, web of science, and Scopus: A systematic comparison of citations in 252 subject categories. J. Informetr. 2018, 12, 1160–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supranee, S.; Rotchanakitumnuai, S. The acceptance of the application of blockchain technology in the supply chain process of the Thai automotive industry. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electronic Business, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 252–257. [Google Scholar]

- Bala, H.; Venkatesh, V. Assimilation of interorganizational business process standards. Inf. Syst. Res. 2007, 18, 340–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, S.; Choi, T.Y.; Hur, D. Buyer power and supplier relationship commitment: A cognitive evaluation theory perspective. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2017, 53, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, W.; Liu, H.; Wei, K.K.; Gu, J.; Chen, H. How do mediated and non-mediated power affect electronic supply chain management system adoption? The mediating effects of trust and institutional pressures. Decis. Support Syst. 2009, 46, 839–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Ke, W.; Wei, K.K.; Hua, Z. Influence of power and trust on the intention to adopt electronic supply chain management in China. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 53, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Teng, J.T. Enhancing supply chain outcomes through information technology and trust. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 54, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, K.; Swanson, D. The supply chain has no clothes: Technology adoption of blockchain for supply chain transparency. Logistics 2018, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, S.; Gunasekaran, A.; Arha, H. Understanding the blockchain technology adoption in supply chains—Indian context. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 57, 2009–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, M.M.; Wamba, S.F. Blockchain adoption challenges in supply chain: An empirical investigation of the main drivers in India and the USA. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 46, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamba, S.F.; Queiroz, M.M. The role of social influence in blockchain adoption: The Brazilian supply chain case. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2019, 52, 1715–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C. Maritime shipping digitalization: Blockchain-based technology applications, future improvements, and intention to use. Transport. Res. Part E Logist. Transport. Rev. 2019, 131, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooque, M.; Jain, V.; Zhang, A.; Li, Z. Fuzzy DEMATEL analysis of barriers to blockchain-based life cycle assessment in China. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2000, 147, 106684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontela, E.; Gabus, A. DEMATEL, Innovative Methods, Report No. 2, Structural Analysis of the World Problematique; Battelle Geneva Research Institute: Geneva, Switzerland, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Karamchandani, A.; Srivastava, S.K.; Srivastava, R.K. Perception-based model for analyzing the impact of enterprise blockchain adoption on SCM in the Indian service industry. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 52, 102019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.; Chadhar, M.; Chetty, M.; Vatanasakdakul, S. An exploratory study of the adoption of blockchain technology among Australian organizations: A theoretical model. In Information Systems, EMCIS 2020; Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing; Themistocleous, M., Papadaki, M., Kamal, M.M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 402, pp. 205–220. [Google Scholar]

- Orji, I.J.; Kusi-Sarpong, S.; Huang, S.; Vazquez-Brust, D. Evaluating the factors that influence blockchain adoption in the freight logistics industry. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2020, 141, 102025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.O. A study on sustainable usage intention of blockchain in the big data era: Logistics and supply chain management companies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahebi, I.G.; Masoomi, B.; Ghorbani, S. Expert oriented approach for analyzing the blockchain adoption barriers in humanitarian supply chain. Technol. Soc. 2020, 63, 101427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, A.; Amagasa, M.; Shiga, T.; Tomizawa, G.; Tatsuta, R.; Mieno, H. The max-min Delphi method and fuzzy Delphi method via fuzzy integration. Fuzzy Set. Syst. 1993, 55, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saurabh, S.; Dey, K. Blockchain technology adoption, architecture, and sustainable agri-food supply chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 284, 124731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, N. Integrating TAM/TRI/TPB frameworks and expanding their characteristic constructs for DLT adoption by service and manufacturing industries—Pakistan context. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Technology and Entrepreneurship, Bologna, Italy, 21–23 September 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wahab, S.N.; Loo, Y.M.; Say, C.S. Antecedents of blockchain technology application among Malaysian warehouse industry. Int. J. Logist. Syst. Manag. 2020, 27, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamba, S.F.; Queiroz, M.M.; Trinchera, L. Dynamics between blockchain adoption determinants and supply chain performance: An empirical investigation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 229, 107791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.W.; Leong, L.Y.; Hew, J.J.; Tan, G.W.H.; Ooi, K.B. Time to seize the digital evolution: Adoption of blockchain in operations and supply chain management among Malaysian SMEs. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 52, 101997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.-W.; Tan, G.W.-H.; Lee, V.-H.; Ooi, K.-B.; Sohal, A. Unearthing the determinants of blockchain adoption in supply chain management. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 2100–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.S.; Singh, A.R.; Raut, R.D.; Govindarajan, U.H. Blockchain technology adoption barriers in the Indian agricultural supply chain: An integrated approach. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 161, 104877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warfield, J.N. Structuring Complex Systems: Battelle Monograph, Number 4; Battelle Memorial Institute: Columbus, OH, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Godet, M. Scenarios and Strategic Management; Butterworths Scientific Ltd.: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Alazab, M.; Alhyari, S.; Awajan, A.; Abdallah, A.B. Blockchain technology in supply chain management: An empirical study of the factors affecting user adoption/acceptance. Clust. Comput. 2001, 24, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, J.; Saleem, A.; Khan, N.T.; Kim, Y.B. Factors influencing blockchain adoption in supply chain management practices: A study based on the oil industry. J. Innov. Knowl. 2021, 6, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balci, G.; Surucu-Balci, E. Blockchain adoption in the maritime supply chain: Examining barriers and salient stakeholders in containerized international trade. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2021, 156, 102539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardim, L.; Pranto, S.; Ruivo, P.; Oliveira, T. What are the main drivers of blockchain adoption within supply chain?—An exploratory research. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 181, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregor, S.; Jones, D. The anatomy of a design theory. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2007, 8, 312–335. [Google Scholar]

- Kamble, S.S.; Gunasekaran, A.; Kumar, V.; Belhadi, A.; Foropon, C. A machine learning based approach for predicting blockchain adoption in supply chain. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 163, 120465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouhizadeh, M.; Saberi, S.; Sarkis, J. Blockchain technology and the sustainable supply chain: Theoretically exploring adoption barriers. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 231, 107831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Bhardwaj, A.; Garg, A.; Gajpal, Y. Determinants of blockchain technology adoption in supply chains by small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in India. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 5537395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzini, F.; Ubacht, J.; De Greeff, J. Blockchain adoption factors for SMEs in supply chain management. J. Supply Chain Manag. Sci. 2021, 2, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maden, A.; Alptekin, E. Understanding the blockchain technology adoption from procurement professionals’ perspective—An analysis of the technology acceptance model using intuitionistic fuzzy cognitive maps. In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Kahraman, C., Onar, S.C., Oztaysi, B., Sari, I.U., Cebi, S., Tolga, A.C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 1197, pp. 347–354. [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz, M.M.; Wamba, S.F.; De Bourmont, M.; Telles, R. Blockchain adoption in operations and supply chain management: Empirical evidence from an emerging economy. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 59, 6087–6103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunmola, F.T.; Burgess, P.; Tan, A. Building blocks for blockchain adoption in digital transformation of sustainable supply chains. Procedia Manuf. 2021, 55, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwanposri, C.; Bhatiasevi, V.; Thanakijsombat, T. Drivers of blockchain adoption in financial and supply chain enterprises. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2021, 09721509211046170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.K.A.; Sundarakani, B. Assessing blockchain technology application for freight booking business: A case study from technology acceptance model perspective. J. Glob. Oper. Strateg. Sourc. 2021, 14, 202–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacovou, C.L.; Benbasat, I.; Dexter, A.S. Electronic data interchange and small organizations: Adoption and impact of technology. MIS Q. 1995, 19, 465–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Sharma, A.; Srivastava, P.K. Blockchain adoption in Indian manufacturing supply chain using T-O-E framework. In Proceedings of the 2022 9th International Conference on Computing for Sustainable Global Development, New Delhi, India, 23–25 March 2022; pp. 737–742. [Google Scholar]

- Chittipaka, V.; Kumar, S.; Sivarajah, U.; Bowden, J.L.-H.; Baral, M.M. Blockchain technology for supply chains operating in emerging markets: An empirical examination of technology-organization-environment (TOE) framework. Ann. Oper. Res. 2022, 327, 465–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Rodriguez-Espindola, O.; Dey, P.; Budhwar, P. Blockchain technology adoption for managing risks in operations and supply chain management: Evidence from the UK. Ann. Oper. Res. 2022, 327, 539–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, N.; Shi, Y.; Wang, J.; Gaur, J. Testing the adoption of blockchain technology in supply chain management among MSMEs in China. Ann. Oper. Res. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, K.K. Understanding the challenges of the adoption of blockchain technology in the logistics sector: The TOE framework. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2022, 36, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökalp, E.; Gökalp, M.O.; Çoban, S. Blockchain-based supply chain management: Understanding the determinants of adoption in the context of organizations. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2022, 39, 100–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, J.L.; Saway, W.; Dobrzykowski, D. Exploring blockchain adoption intentions in the supply chain: Perspectives from innovation diffusion and institutional theory. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2022, 52, 190–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, G.; Kamble, S.S.; Ndubisi, N.O.; Shrivastava, A.; Belhadi, A.; Venkatesh, M. Antecedents of blockchain-enabled e-commerce platforms (BEEP) adoption by customers—A study of second-hand small and medium apparel retailers. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 149, 576–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapnissis, G.; Vaggelas, G.K.; Leligou, H.C.; Panos, A.; Doumi, M. Blockchain adoption from the Shipping industry: An empirical study. Marit. Transp. Res. 2022, 3, 100058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Upreti, K.; Mohan, D. Blockchain adoption for provenance and traceability in the retail food supply chain: A consumer perspective. Int. J. E-Bus. Res. 2022, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yuen, K.F. Blockchain implementation in the maritime industry: Critical success factors and strategy formulation. Marit. Policy Manag. 2022, 51, 304–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mthimkhulu, A.; Jokonya, O. Exploring the factors affecting the adoption of blockchain technology in the supply chain and logistic industry. J. Transp. Supply Chain Manag. 2022, 16, a750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, S.D.; Khayer, A.; Majumder, J.; Barua, S. Factors affecting blockchain adoption in apparel supply chains: Does sustainability-oriented supplier development play a moderating role? Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2022, 122, 1183–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguntegbe, K.F.; Di Paola, N.; Vona, R. Behavioural antecedents to blockchain implementation in agrifood supply chain management: A thematic analysis. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saputra, U.W.E.; Darma, G.S. The intention to use blockchain in Indonesia using extended approach technology acceptance model (TAM). CommIT J. 2022, 16, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadlapalli, A.; Rahman, S.; Gopal, P. Blockchain technology implementation challenges in supply chains—Evidence from the case studies of multi-stakeholders. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2022, 33, 278–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adel, H.M.; Younis, R.A.A. Interplay among blockchain technology adoption strategy, e-supply chain management diffusion, entrepreneurial orientation and human resources information system in banking. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2023, 18, 3588–3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Islam, N.; Qureshi, H.N. Understanding the Acceptability of Block-Chain Technology in the Supply Chain: Case of a Developing Country; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.H.; Chung, L.; Tan, K.H.; Makhbul, Z.M.; Zhan, Y.; Tseng, M.-L. Investigating blockchain technology adoption intention model in halal food small and medium enterprises: Moderating role of supply chain integration. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2023, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baral, M.M.; Chittipaka, V.; Pal, S.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Shyam, H.S. Investigating the factors of blockchain technology influencing food retail supply chain management: A study using TOE framework. Stat. Transit. 2023, 24, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, I.H.; Amin, I.U. Chapter 15—Adoption and acceptability of blockchain technology in supply chain management: A study on horticulture industry of Jammu and Kashmir. In Green Blockchain Technology for Sustainable Smart Cities; Krishnan, S., Kumar, R., Balas, V.E., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 325–342. [Google Scholar]

- Boakye, E.A.; Zhao, H.; Coffie, K.C.P.; Asare-Kyire, L. Seizing technological advancement: Determinants of blockchain supply chain finance adoption in Ghanaian SMEs. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2023, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Hao, X.; Wang, K.; Dong, X. The impact of perceived benefits on blockchain adoption in supply chain management. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çaldağ, M.T.; Gökalp, E. Organizational adoption of blockchain based medical supply chain management. In Current and Future Trends on Intelligent Technology Adoption, Studies in Computational Intelligence; Al-Sharafi, M.A., Al-Emran, M., Tan, G.W.-H., Ooi, K.-B., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 1128, pp. 321–343. [Google Scholar]

- Çolak, H.; Kağnıcıoğlu, C.H. Predicting the blockchain technology acceptance in supply chains with inter-firm perspective: An integrated DEMATEL and PLS-SEM approach. J. Bus. Bus. Mark. 2023, 30, 125–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.-S.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, Z.-J.; Tsang, Y. Fairness-aware large-scale collective opinion generation paradigm: A case study of evaluating blockchain adoption barriers in medical supply chain. Inf. Sci. 2023, 635, 257–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganeshkumar, C.; Rajalaksmi, M.; David, A. Exploring the challenges and adoption hurdles of blockchain technology in agri-food supply chain. In Handbook of Research on AI-Equipped IoT Applications in High-Tech Agriculture; Khang, A., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 257–270. [Google Scholar]

- Giri, G.; Manohar, H.L. Factors influencing the acceptance of private and public blockchain-based collaboration among supply chain practitioners: A parallel mediation model. Supply Chain Manag. 2023, 28, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.; Ding, W.; Zhang, B.; Verny, J. The role of supply chain alignment in coping with resource dependency in blockchain adoption: Empirical evidence from China. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2023, 36, 605–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.; Ding, W.; Zhang, B.; Verny, J.; Hao, R. Do supply chain related factors enhance the prediction accuracy of blockchain adoption? A machine learning approach. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 192, 122552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranmanesh, M.; Maroufkhani, P.; Asadi, S.; Ghobakhloo, M.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Tseng, M.-L. Effects of supply chain transparency, alignment, adaptability, and agility on blockchain adoption in supply chain among SMEs. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 176, 108931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karuppiah, K.; Sankaranarayanan, B.; Ali, S.M. A decision-aid model for evaluating challenges to blockchain adoption in supply chains. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2023, 26, 257–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju-Long, D. Control problems of grey systems. Syst. Control Lett. 1982, 1, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavadskas, E.K.; Turskis, Z.; Antucheviciene, J.; Zakarevicius, A. Optimization of weighted aggregated sum product assessment. Electron. Electr. Eng. 2012, 122, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuei, S.-C.; Chen, M.-C. Enablers of blockchain adoption on supply chain with dynamic capability perspectives with ISM-MICMAC analysis. Ann. Oper. Res. 2023, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Barua, M.K. Exploring the hyperledger blockchain technology disruption and barriers of blockchain adoption in petroleum supply chain. Resour. Policy 2023, 81, 103366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-F. Blockchain adoption in the maritime industry: Empirical evidence from the technological-organizational-environmental framework. Marit. Policy Manag. 2023, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; Potdar, V.; Quaddus, M. Exploring factors and impact of blockchain technology in the food supply chains: An exploratory study. Foods 2023, 12, 2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, S.; Baral, M.M.; Lavanya, B.L.; Nagariya, R.; Patel, B.S.; Chittipaka, V. Intentions to adopt the blockchain: Investigation of the retail supply chain. Manag. Decis. 2023, 61, 1320–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, T.A.; Sharma, R.; Ganguly, K.K.; Wamba, S.F.; Jain, G. Enablers to the adoption of blockchain technology in logistics supply chains: Evidence from an emerging economy. Ann. Oper. Res. 2023, 327, 251–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, K.; Zhang, Q.; Khan, M.K.; Ashfaq, M.; Hafeez, M. The acceptance and continued use of blockchain technology in supply chain management: A unified model from supply chain professional’s stance. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2023, 18, 6300–6321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, K.; Zhang, Q.; Zafa, A.U.; Ashfaq, M.; Rehman, S.U. The role of blockchain-enabled traceability, task technology fit, and user self-efficacy in mobile food delivery applications. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 73, 103331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Patidar, A.; Anchliya, N.; Prabhu, N.; Asok, A.; Jhajhriya, A. Blockchain adoption in food supply chain for new business opportunities: An integrated approach. Oper. Manag. Res. 2023, 16, 1949–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Sharma, A.; Singh, R.K.; Bhatia, T. Blockchain adoption in agri-food supply chain management: An empirical study of the main drivers using extended UTAUT. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2023, 29, 737–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumarliah, E.; Li, T.; Wang, B.; Khan, S.U.; Khan, S.Z. Blockchain Technology Adoption in Halal Traceability Scheme of the Food Supply Chain: Evidence from Indonesian Firms; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasnim, Z.; Shareef, M.A.; Baabdullah, A.M.; Hamid, A.B.A.; Dwivedi, Y.K. An empirical study on factors impacting the adoption of digital technologies in supply chain management and what blockchain technology could do for the manufacturing sector of Bangladesh. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2023, 40, 371–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B.S.; Rust, S. Blocking blockchain: Examining the social, cultural, and institutional factors causing innovation resistance to digital technology in seafood supply chains. Technol. Soc. 2023, 72, 102235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafadarnikjoo, A.; Badri Ahmadi, H.; Liou, J.J.H.; Botelho, T.; Chalvatzis, K. Analyzing blockchain adoption barriers in manufacturing supply chains by the neutrosophic analytic hierarchy process. Ann. Oper. Res. 2023, 327, 129–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-J.; Chen, Z.-S.; Xiao, L.; Su, Q.; Govindan, K.; Skibniewskic, M.J. Blockchain adoption in sustainable supply chains for Industry 5.0: A multistakeholder perspective. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Yu, H.; Li, J. An ISM-DEMATEL analysis of blockchain adoption decision in the circular supply chain finance context. Manag. Decis. 2023; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.K.; Kumar, D. Blockchain technology and vaccine supply chain: Exploration and analysis of the adoption barriers in the Indian context. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2023, 255, 108716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Khan, S.; Khan, S.U.; Khan, I.U. Understanding blockchain technology adoption in operation and supply chain management of Pakistan: Extending UTAUT model with technology readiness, technology affinity and trust. SAGE Open 2023, 13, 21582440231199320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zkik, K.; Belhadi, A.; Khan, S.A.R.; Kamble, S.S.; Oudani, M.; Touriki, F.E. Exploration of barriers and enablers of blockchain adoption for sustainable performance: Implications for e-enabled agriculture supply chains. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2023, 26, 1498–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton, J.D. Diffusion of innovations. Circuits Assem. 1998, 9, 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kamble, S.S.; Gunasekaran, A.; Sharma, R. Modeling the blockchain-enabled traceability in the agriculture supply chain. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 52, 101967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M. Chapter 1—The resource-based theory of competitive advantage: Implications for Strategy Formulation. In Knowledge and Strategy; Zack, M.H., Ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1999; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, W.M.; Levinthal, D.A. Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senyo, P.K.; Effah, J.; Addae, E. Preliminary insight into cloud computing adoption in a developing country. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2016, 29, 505–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]