Abstract

Organic agriculture represents an alternative system of agricultural production that is included in the so-called sustainable agricultural practices. Development strategies in almost all countries today highlight the problem of environmental degradation, which is partly caused by the application of agrotechnical measures used in conventional agriculture. Consequently, organic production is gaining more and more importance, affecting the trend of its development. Considering the status of the Republic of Serbia as a candidate country for the European Union, it is of particular importance to understand the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) of the EU and the position that organic producers and production have. The aim of this research was to analyze the attitudes of organic producers towards the CAP and the agrarian policy of the Republic of Serbia and their expectations following the Republic of Serbia’s entry into the EU. Statistical data processing involved descriptive statistical analysis followed by binary logistic regression. The results of the research showed that organic producers are not sufficiently familiar with the CAP, they believe that the agricultural policy of the Republic of Serbia is not favorable for organic producers and that their situation will not change significantly with entry into the EU, but that the position of organic production in the EU is better in comparison to that of the Republic of Serbia. In conclusion, the authors state that such attitudes and thoughts of organic producers are a limiting factor in the further development of organic agriculture and that it is necessary to work on them through continuous measures developed by competent ministries, local self-governments and advisory services.

1. Introduction

Organic agriculture represents an alternative system of agricultural production whose focus is on sustainability. When viewed as a concept, sustainability or sustainable development represents a production system that takes into account all socio-economic and ecological characteristics of a certain type of production and organizes all production resources based on them. Moderation is imperative in this type of production. One of the most frequently used definitions of sustainable development is the one formulated by the so-called Brundtland Commission [1], which states that sustainable development is “...a set of activities that allow meeting the needs of today’s generation without compromising the possibilities of future generations to meet their own needs”. One of the first definitions of sustainable development was given by Repetto [2], who stated that at the core of sustainability is the idea that decisions made today should not jeopardize the preservation or improvement of living standards in the future. Jovanović-Gavrilović [3] emphasizes that if we observe development as an enhancement of well-being, then sustainable development presupposes no reduction in welfare over time. Harris [4] also states that “the road of sustainable development can be understood as the development where total funds of fixed assets remain the same or increase over time”.

Observed from the mentioned aspects of sustainability, the problems of modern agricultural production, which are reflected in the excessive consumption of resources and environmental degradation, are often highlighted in the scientific literature [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. The solutions to these problems of modern (conventional) agriculture are most often sought in the so-called alternative systems of agricultural production, including organic agriculture. In addition to organic production, the following systems of sustainable (alternative) agricultural production are represented: biodynamic production, integral agriculture, permaculture, LISA (low-input sustainable agriculture) production system (agricultural production with minimal inputs), no-tillage system (production system without soil cultivation), etc. They differ from each other in terms of the way they perceive the problem and the approach to solving it, but they have a common characteristic, which is that they respect the principle of sustainability.

During its decades-long development, organic agriculture was defined differently depending on what the goal of the analysis was and what was being investigated. Among the most widely accepted definitions, the one given by Lampkin and Padel [14] stands out. They define organic agriculture as both a philosophy and a production system that aims to create integrated, humane, economically sustainable agriculture oriented towards environmental protection and maximum use of renewable resources produced on the farm itself. Beauchesne and Bryanti [15] define organic agriculture as a social and technological alternative to conventional production, while Cifrić [16] believes that ecological (organic) agriculture is a social innovation and should be understood as giving up the dominance of the paradigm of industrial agriculture and the possibility of additional employment of labor on the family farm, settlement and society for the convenience of producing quality products on small areas, encouraging the development of “closed” production systems with greater use of natural energy and organic processes. Regardless of the differences in definition, most authors agree that organic agriculture can be defined as a system that is in harmony with the environment [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26] and is profitable for the economy [14,26,27,28,29,30,31] but respects the specific production characteristics of each economy [32,33].

In 2005, IFOAM (International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements) adopted four basic principles of organic production, which summarize all of the above. These are: (1) health; (2) ecology; (3) fair behavior and (4) care. These principles represent the basis for the legal regulation of this production system [34].

One of the basic and highly emphasized advantages of organic production is the fact that this system is legally regulated through a certification process that ensures and guarantees that the basic principles of organic agriculture have been applied and respected during the production process. Padel and Lampkin [35] state that although organic production has existed as a concept for almost seventy years, it received significant attention from European policymakers only in the mid-1980s. The mentioned authors attribute the notable growth in this sector since the 1980s to the significant interests of economic policymakers in this production.

Agrarian policy provides a regulatory framework for all economic and political measures designed to affect the modern agricultural sector [36]. It plays a pivotal role in shaping the trajectory of farming practices and influencing the decisions of producers worldwide. In this regard, today in all EU member countries as well as in the USA, South America, Japan and Australia, organic production is supported by appropriate legal, systemic and institutional measures. In the scientific literature, there are different views on agrarian policy and organic agriculture, but most of the authors agree that agriculture, especially organic agriculture, needs state support [14,36,37,38,39,40,41].

The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) is a cornerstone of the European Union’s (EU) agricultural framework, designed to ensure food security, environmental sustainability and economic viability for farmers. In recent years, the CAP has taken on a more dynamic role in shaping the landscape of organic farming within the EU. This shift is particularly significant as the demand for organic produce continues to grow, driven by consumer preferences for sustainable and environmentally friendly agricultural practices. On 30 May 2018, the European Commission adopted the new EU Regulation 2018/848 on organic production and labeling of organic products. According to the EU Farm to Fork and Biodiversity Strategies, which are part of the European Green Deal, member states should target 25% of organic land area by 2030. Bottazzi et al. [42] agree, stating that developing organic farming is among the most popular policy options for protecting soil, water, and biodiversity while improving incomes for agricultural producers around the World. Berckmans et al. [43] suggested that in order to achieve this goal, the EU has to:

- Triple its organic land area between 2019 and 2030;

- Increase its overall CAP expenditure 3–5-fold by 2030;

- Dedicate 9–15% of the CAP budget to organic farming (instead of the 3% dedicated in 2018).

Guth et al. [44] state that the need to guarantee the efficiency of the agricultural sector and to shape production in order to limit its negative impact on the natural environment is one of the most important priorities of the EU’s common agricultural policy (CAP). In particular, the relationship between efficiency and environmental balance under the policy support for small-scale family farms is not widely established. Answering this question is important because small-scale farms are the basis for the functioning of agricultural sectors in many regions of the world. Also, in Switzerland, Green Public Procurements (GPPs) are growing stronger. GPP can be understood as a purchasing process where the public authority strives to procure goods and services that have less environmental impact, based on life cycle costs, compared to the non-green alternative that would otherwise be procured [45]. Furthermore, Bhatt and John [46] in their study assessed the policies implemented to enable the transition of the agricultural sector to fully organic in Sikkim state in India, inferring that, when integrated well, circular economy and organic agriculture can reinforce each other’s goals, supported by appropriate policy measures.

In Serbia, agriculture, as one of the most important production sectors, accounts for about 10% of the national GDP (Gross Domestic Product) and contributes to 20% of exports, employing over 20% of the working-age population. Organic production in the Republic of Serbia is growing and is becoming more evident, including the potential socioeconomic and environmental benefits that it can generate. In this context, the intersection of organic farming and the common agricultural policy (CAP) becomes a focal point for exploration, especially considering the fact that Serbia is a candidate country for EU membership. This research intends to tackle the perspectives of organic producers in Serbia while combining their ways of thinking with their basic characteristics.

Until now, no research has been conducted in the Republic of Serbia to analyze how and in what way organic producers in Serbia perceive the EU’s common agricultural policy, whether they are at all familiar with it and what their expectations are. Also, analysis of their knowledge and satisfaction with the agrarian policy of the Republic of Serbia has not been conducted. Accordingly, the purpose of this research was to fill these research gaps and to gain initial insights into the attitudes of organic producers towards agrarian policies. One important goal of the research was to determine the relationship between the way of thinking of organic producers and their basic characteristics. The goal, among others, was to determine whether the level of education, gender, knowledge of languages and other soft skills contribute to the broader thinking of producers in terms of their knowledge about agricultural policies beyond the narrowest knowledge of the amount of subsidies for organic production.

In the subsequent sections of the paper, a description of the study area is first presented. After that, the materials and methods used are explained, followed by the results and discussion, which first focus on the agrarian policy in the Republic of Serbia and the measures aimed at organic production, and then on the results of a semi-structured interview. Finally, the conclusion section gives a final statement on the issue.

2. Description of the Study Area

The Republic of Serbia is a landlocked country situated in the Balkans region of Southeast Europe. It shares borders with several countries, including Hungary to the north, Romania to the northeast, Bulgaria to the southeast, North Macedonia to the south, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina to the west and Montenegro to the southwest. It covers an area of approximately 88,499 square kilometers. According to Greenwich, Serbia is located between 41°53′ and 46°11′ north latitude and 18°49′ and 23°00′ east longitude. Serbia’s geographical location places it at a crossroads of continental climates, resulting in diverse weather patterns across the country. Generally, Serbia experiences a continental climate with four distinct seasons. Winters tend to be cold and snowy, particularly in the mountainous regions, while summers range from warm to hot, with occasional heatwaves. Spring and autumn are transitional seasons marked by mild temperatures and variable weather conditions.

The country’s agricultural sector benefits from its favorable climate and varied terrain, supporting a diverse range of crops and livestock. According to the initial published results of the last agricultural census conducted in 2023 (https://stat.gov.rs//media/377377/ppt-prvi-rezultati-pp-2023.pdf, accessed on 15 May 2024), Serbia has 4,073,703 hectares of available agricultural land, of which 3,257,100 ha is utilized agricultural land. There are 508,365 registered agricultural farms, of which 99.6% are family farms. The average age of farm owners is 60 years, and every 11th owner is under 40 years old. The average size of farms is 6.4 hectares. The largest number of agricultural farms is located in the Šumadija and Western Serbia region.

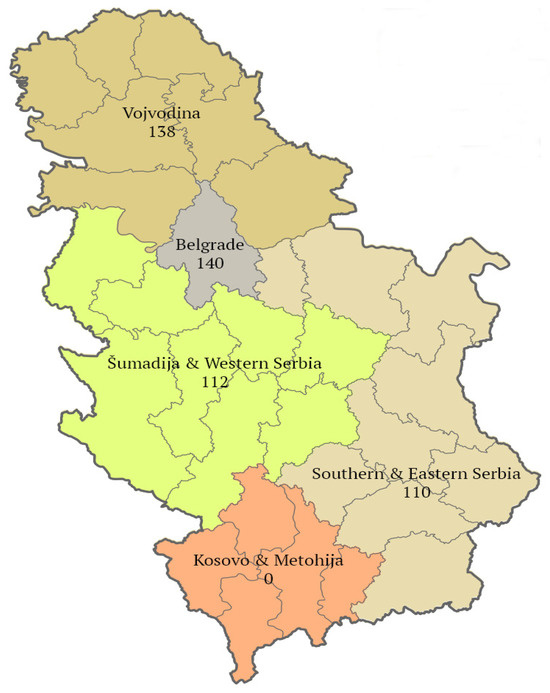

The NUTS classification of territorial units serves as a structure for organizing consistent statistical data across geographical regions within the European Union (EU). Its primary aim is to establish a standardized format for gathering and disseminating statistical data, facilitating analysis and supporting European policy initiatives. Serbia has categorized its regions based on the NUTS 2 classification, as it aligns well with the country’s institutional support needs. According to this classification, the regions in Serbia are:

- Vojvodina

- Belgrade

- Šumadija and Western Serbia

- Southern and Eastern Serbia

- Kosovo and Metohija

This research was conducted in 2018 within the territory of the Republic of Serbia where 500 individual organic producers were registered. Their distribution, as well as their division by region, is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Regions in Serbia showing the number of registered organic producers in 2018.

Organic Agriculture in the Republic of Serbia

Data from the Ministry of Agriculture’s group on organic production as well as data by Simić [47] shows an increase in the area under the organic production system, an increase in the number of animals and an increase in the number of producers in the Republic of Serbia in 2022. Production took place on 25,035 hectares (including areas that are in the conversion period). Compared to 2021, the area increased by more than 10%, while over a period of ten years, the area increased by more than 260%. The share of organic production in the total arable land in 2022 was 0.77%, which is still a low level, considering the level of development of this system of agricultural production (Table 1).

Table 1.

Areas under organic production in the Republic of Serbia in 2010–2022 in ha and % [47,48].

In terms of structure, fruit dominated the total arable area, with 5702 hectares (including areas in the conversion period) in 2022. Cereals covered 3838 hectares and meadows and pastures covered 8322 hectares (Table 2). The table below provides an overview of the structure of arable land under organic production in the Republic of Serbia from 2012 to 2022.

Table 2.

Area (in ha) under organic plant production in the Republic of Serbia in 2012–2022 [47,48].

For livestock production in 2022, there was an increase in the number of all types of animals, except pigs and horses, compared to 2021 (Table 3). The number of animals in the organic production system is presented in the following table.

Table 3.

Organic livestock production in the Republic of Serbia in 2012–2022 [47,48].

Organic producers in Serbia are represented in two basic groups: independent or individual organic producers who have certified production on their farms and deal with the production and marketing of organic products. This group of producers was included in this research. The second group of producers consists of the so-called subcontractors, whose production is subject to group certification in accordance with the Law on Organic Production, and the producers themselves are in a contractual relationship with a company that buys their entire production, which is intended for the export market. The company provides the producers with raw materials and education and covers the costs of certification (the holder of the certificate is the company and not the producer) and other types of support needed for this production. This type of organic production has proven to be successful judging by the number of producers, which far exceeds the number of individual producers (Table 4).

Table 4.

Organic producers in the Republic of Serbia from 2010 to 2022 [47,48].

Bearing in mind the trends in the world and in the Republic of Serbia, it can be said that organic agriculture has recorded a growth trend when it comes to the area under production, the number of animals in livestock production and the number of producers involved in this production system. Of course, we should never lose sight of the fact that organic production still represents a relatively small share of the entire agricultural production (0.77% in the Republic of Serbia), which leads to the conclusion that organic agriculture is still an alternative form of production and a lot of work still needs to be done to expand it.

3. Materials and Methods

Research results were obtained by means of a semi-structured interview. The survey respondents were individual agricultural farmers who hold certificates for organic production in the territory of the Republic of Serbia. The main feature of the respondents was farming that was already certified, not farming that was still in the process of conversion to organic agriculture. There were 66 respondents, and the research was conducted from March to November 2018.

The data collected through the survey questionnaire were systematized and processed using the statistical software R 4.3.2. The first part of the results from the questionnaire presents answers to questions about the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents and the characteristics of the farms themselves; descriptive statistical analysis was used for statistical processing of these data. The second part of the questionnaire referred to the views of respondents on the domestic and EU markets for organic products. To examine the differences between the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents and their views on the state of the domestic and EU markets for organic products, the Chi-square test of independence was applied. The Chi-square test starts from the null hypothesis that there is no relationship between the observed variables, against the alternative hypothesis that there is a statistically significant relationship between the variables [49]. Binary logistic regression was applied in the next part of the research to determine the impact of various socio-demographic characteristics and the characteristics of the farms themselves on the attitudes of respondents on whether they think that the situation in organic agriculture will improve with Serbia’s entry into the European Union. Unlike linear regression, which is based on continuous variables, logistic regression is used to classify and predict discrete categorical variables [50].

The following logistic function was used for estimation in a concrete model:

The variable z denotes the factors’ exposure, and y(z) signifies the likelihood of a specific outcome given those factors. In essence, the variable z serves as a metric encapsulating the overall impact of all model-utilized factors.

The variable z is defined as follows:

where α represents the initial value of the variable z, i.e., the value of z if all independent variables are equal to 0, i.e., if there are no risk factors. Coefficients β show the contribution of the factor to which they refer. A positive value of the parameter β means that the factor increases the probability of the outcome, and a negative value means that it decreases the probability of the outcome.

When the dependent variable Y is dichotomous, then 0 ≤ E(Y|x) ≤ 1 applies and the dependent variable takes either the value 1 or 0 depending on the outcome of the experiment. Logistic regression models the likelihood π as:

π = P(Y = 1|X1 = x1…, Xk = xk)

The special form of the regression model used is:

In the above equation, π(x) represents the expected value of Y for a particular value of x, while parameters α and correspond to parameters α and k from the basic form of linear regression model and represent the baseline average of dependent variables and the coefficients indicating the average alteration in logit per unit change in the independent variable. The logistic regression function is inherently nonlinear but it can be linearized through the process of logit transformation.

If the logistic regression function is linearized, the following form is obtained:

If represents the probability that something will not happen, then is the chance ratio, i.e.,:

If both sides of the equation are logarithmized with the natural logarithm, the following equation is obtained:

The obtained equation is called a logit and is linear.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Agricultural Policy and Organic Production in the Republic of Serbia

In the Republic of Serbia, support for agriculture and rural development is regulated by the Law on Agriculture and Rural Development [51] and by the Law on Subsidies in Agriculture and Rural Development [52], which regulate the objectives of the agricultural and rural development policy as well as the manner of their realization, the register of agricultural holdings, recording and reporting in agriculture and the supervision of the implementation of this law. This law also regulates the rules of the special procedures for the implementation and control of the IPARD program. Agricultural holdings registered in the Register of Agricultural Holdings (RPG) are entitled to support. The amount of support is determined on an annual basis by the regulation on the distribution of incentives in agriculture and rural development. All support measures are administered based on appropriate by-laws, which more closely define the conditions for realizing the rights to incentives as well as the ways of realizing those rights.

The types of agricultural incentives in the Republic of Serbia are:

- Direct incentives

- Measures of rural development

- Special incentives and

- Credit support.

Each of the mentioned forms of incentives has its respective role and applicable rules. Direct payments have the most allocated budget funds. They include premiums, incentives for production and rebates. The measures for rural development include support for programs related to (1) increasing competitiveness, (2) preserving and improving the environment and natural resources, (3) diversification of income and improvement of the quality of life in rural areas, (4) preparation and implementation of local strategies for rural development, and (5) improvement of the creation and transfer of knowledge. Special incentives refer to various activities such as (1) incentives for marketing information systems in agriculture, (2) incentives for the establishment, development and functioning of accounting data systems for agricultural holdings, (3) incentives for the implementation of breeding programs in order to achieve breeding goals in animal husbandry, (4) incentives for promotional activities in agriculture and rural development, and (5) incentives for the production of planting material, certification and clonal selection. Credit support refers to the approval of commercial loans, with low interest rates, under special conditions prescribed by the Ministry of Agriculture.

Incentives for organic production were introduced in 2004; however, over the years, the type of support as well as the amounts, beneficiaries and conditions that producers have to fulfil in order to obtain these incentives have changed. Financial support for the organic production sector in Serbia began in 2005/2006. Then, for the first time, incentive funds for organic production were introduced by the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry in the form of compensation for certification costs. Based on the Law on Subsidies in Agriculture and Rural Development [52], incentives for organic plant production include incentives for plant production and rebates for fuel and/or fertilizers and/or seeds, which are given to areas under organic plant production in amounts that are, at a minimum, 40% higher than the amounts given for conventional plant production, recourses for fuel and/or fertilizers and/ or seeds. Once incentives for organic plant production have been obtained, direct payments for the same area and the same measure cannot be obtained. Incentives for organic livestock production include payments for milk premiums and livestock incentives at amounts higher than at least 40% of the incentives given for conventional production. From 2014 to 2020, the incentives for organic plant production were increased by different percentages that amounted to 40, 70, 120, and 400% more than the basic incentives for plant production, i.e., conventional production, while the incentives for organic livestock production were increased by 40% during this period (Table 5).

Table 5.

Subsidies (in euros) for organic crop production in 2014–2020 *.

To gain insights into the differences between the CAP and the agrarian policy of the Republic of Serbia, Table 6 shows some CAP subsidies offered to member countries in 2023–2027 (Table 6).

Table 6.

Subsidies for organic production in some EU member states [53].

The mentioned amounts show that the agrarian policy of the Republic of Serbia is not lagging compared to the EU CAP, i.e., in the last two years, subsidies for this production system have been even higher than the amounts offered by some member countries.

Based on these conclusions, this research was conducted because it is important to gain insights into how organic producers perceive the European Union and the support for organic agriculture in the EU and whether they believe that they are institutionally supported in the Republic of Serbia.

4.2. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents

In order to comprehensively analyze the obtained data, the starting point was the analysis of the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents, the results of which are shown in Table 7. Based on the results of the descriptive statistical analyses, in the survey of 66 respondents, the representation of male respondents was 71.2% and the representation of female respondents was 28.8%. When it comes to the age structure of respondents, the largest percentage of respondents was in the age group of 51–60 years old (31.8%), followed by participants in the group of 41–50 years old (28.8%); respondents aged up to 30 years old constituted the lowest percentage of participants (7.6%).

Table 7.

Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents.

Based on the level of education, the highest representation consisted of respondents with higher education (50%), followed by respondents with completed high school education (45.5%); respondents with completed primary school education constituted only 4.5% of the participants. Almost two-thirds of respondents (74.2%) had no education in agriculture, 10.6% had incomplete or complete elementary school, 9.1% had incomplete or complete agricultural faculty education, 4.5% had incomplete or complete higher agricultural school education and only 1.5% were pupils or students. When asked if they owned a computer on the farm, the majority of respondents declared that they owned a computer (97%), and the highest percentage (59.1%) rated their knowledge of working with computers as advanced while 37.9% declared that they had basic computer skills. When asked if they spoke English, slightly more than half of the respondents answered yes (56.1%), while 43.9% of the respondents answered that they did not speak English. When asked whether they kept internal records of expenses and income on the farm, almost all respondents answered yes (92.4%), and only 7.5% of respondents answered that they did not keep these types of records. A little more than half (54.5%) of the respondents’ farms belonged to the mixed agricultural farms group, whose income comes from agricultural production as well as from other sources, while 45.5% of the farms belonged to the purely agricultural farms group, which generate their income exclusively from engaging in agricultural production on the farm itself.

In the following part, the results of the analysis of respondents’ views on the state of the domestic and EU markets for organic products are presented (Table 8).

Table 8.

Respondents’ views on the domestic and EU markets for organic products.

Based on the results presented in the table above, it can be seen that the majority of respondents (89.4%) believed that the domestic market for organic products is not sufficiently developed, while only 10.6% of respondents believed that the domestic market for organic products is sufficiently developed. Also, more than two-thirds of respondents (77.3%) believed that the economic and agricultural policy of the Republic of Serbia is not at all favorable for organic producers. Slightly more than half of the respondents (59.1%) answered that they were familiar with the common agricultural policy of the European Union, while 40.9% were not familiar with it at all. When asked whether they expected the situation in organic agriculture to improve with the accession of the Republic of Serbia to the EU, slightly more than half of the respondents answered no (47.6%), while 42.4% of respondents believed that entry into the EU would improve the situation of organic agriculture production in the Republic of Serbia. Most respondents (98.5%) believed that producers in the organic system of production receive better “treatment” compared to those in the conventional system in the EU; additionally, 98.5% of respondents believed that in the Republic of Serbia, producers of organic products did not receive better “treatment” in comparison to conventional ones. When asked why they thought that organic producers received (or did not receive) better treatment in the Republic of Serbia compared to conventional producers, 34.9% of respondents stated that they believed that the cause was insufficient financial support, 31.8% believed that the cause was more about the administration associated with organic production, and 33.3% of respondents believed that the cause was something else. It should be added that the interview did not contain formal questions that would have assessed the level of knowledge of the common agricultural policy of the EU, but the researchers, based on their experience and knowledge (as well as informal conversations with respondents), concluded that producers were familiar with the CAP and that their answers could be considered relevant.

The following table (Table 9) shows the results of the Chi-square test, which was used to analyze whether there are statistically significant differences between respondents in terms of their socio-demographic characteristics and their views on the state of the domestic and EU markets for organic products.

Table 9.

Chi-Square test results.

Based on the results of the Chi-square test in the above table, statistically significant differences in the respondents’ attitudes based on gender existed only in their opinions about why organic producers receive (or do not receive) better treatment in Serbia compared to conventional producers (p < 0.05). Male respondents believed that insufficient financial support was the biggest reason, while female respondents stated more administration associated with organic production as the most common answer. Based on the obtained results, it can be observed that the views of the respondents on all issues related to the state of the domestic market and the EU market for organic products did not differ based on age (p > 0.05). In the case of the level of education, it can be observed that a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) existed only in the opinion of the respondents on whether they thought that producers in the organic production system received better “treatment” compared to those in the conventional system in the Republic of Serbia; that is, only the respondents who completed elementary school gave an affirmative answer, while all those with secondary school and higher education answered no. Based on the obtained results, it can be observed that the views of the respondents on all issues related to the state of the domestic market and the EU market for organic products do not differ based on their level of education in agriculture or based on whether they speak English (p > 0.05).

4.3. Logistic Regression

In the next part of the analysis, the impact of the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents and the characteristics of the farms themselves on the attitude of the respondents on whether they expect the situation in organic agriculture to improve with Serbia’s entry into the European Union was examined (1-yes, 0-no). To conduct this analysis, binary logistic regression was applied; the first categories were included as the reference groups for each categorical variable. The results of the Omnibus test determined that the binary logistic regression model was well adapted to the input data (χ2(15) = 10.309, p = 0.038). This result was also confirmed by the results of the Hosmer–Lemeshow test (χ2(8) = 5.791, p = 0.671). The results of the binary logistic regression are shown in Table 10.

Table 10.

Logistic regression analysis results.

Based on the results of the binary logistic regression shown in Table 8, it can be seen that among statistically significant variables influencing the respondents’ attitude on whether the situation in organic agriculture will improve with Serbia’s entry into the European Union, at the significance threshold of 5% (p < 0.05), only the knowledge of the English language and computer skills were singled out, while the other variables did not have a statistically significant influence.

Investigation of the attitudes or opinions of agricultural producers found justification for several facts. Quandt [54] states that understanding how producers perceive certain things and how they react to them is crucial to maintaining the entire agricultural system. She focused her research on the impact of agricultural policy on the formation of resilience among producers. Fusco et al. [55] focused on the environmental impact of agriculture, assessing eco-efficiency in agriculture as a way of developing benchmarking policies between different Italian regions. They concluded that national and local governments should consider encouraging the entire agricultural sector to adopt a more efficient and sustainable way of agricultural production. On the other hand, Timpanaro et al. [56] discussed whether recent world events should shift policymakers’ focus from sustainable to intensive and competitive agriculture. The state of the concept of national “self-sufficiency” is being revisited, especially due to the pandemic and conflicts in Europe. In their research on 106 farms, they assessed, among others, the level of producer satisfaction and adherence to CAP. They concluded that producers have a positive attitude towards CAP and believe that this policy is good for them and their production. Similarly, Brown et al. [57] studied whether the design of environmental payments in the CAP reflects current knowledge about farmers’ decision-making through literature review and interviews. Based on their research, especially interviews with producers, they concluded that an urgent redesign of agricultural subsidies is needed to better align them with the economic, social and environmental factors affecting decision-making by farmers. This aligns with our presumption that it is necessary to understand how farmers see and think about certain policies in order to make policies more suitable for agricultural development.

When it comes to policy adjustment to the needs of the producers, Vilpoux et al. [58] conducted research to assess the policies that were best suited to the success of the agrarian system. They concluded that there is a need for the development of policies that are adapted to producers.

The research focused on policies and incentives needed because it can explain whether subsidy systems are well designed and set up, whether they (subsidies) are used in appropriate ways and how they can be improved. For example, Spiegel et al. [59] found that support for organic hazelnut production can be distortive and that payments under the CAP initiate investments that otherwise would have been unprofitable. They recommended that the current policy should be substantially changed by imposing additional restrictions.

5. Conclusions

As stated in the introduction, organic agriculture represents an alternative system of agricultural production that has been experiencing expansion worldwide in recent decades. One of the basic characteristics of this system that significantly distinguishes it from others is its legal regulation and the special attention taken in the strategic development of documents. As a system that is subject to legal regulation, its development is greatly influenced by institutional support.

By analyzing the regulatory landscape and examining the evolution of incentives for organic farming, the research highlights the concerted efforts of Serbian authorities to promote sustainable agriculture and rural development. The delineation of various forms of support, including direct payments, rural development measures, special incentives and credit support, underscores the multifaceted approach adopted to bolster agricultural activities and enhance the quality of life in rural areas.

Moreover, the comparison of subsidies for organic production between Serbia and select EU member states offers interesting findings. Despite Serbia’s status as a non-EU country, the study reveals that subsidies for organic agriculture in Serbia are comparable to, if not higher than, those provided in certain EU nations. This suggests a strong commitment to organic farming within the Serbian agricultural policy framework and underscores the country’s aspirations to align with European standards and best practices.

The Republic of Serbia is a candidate country for EU membership, and the common agricultural policy is something that agricultural producers will encounter during accession. Their attitude towards this policy and the beliefs they have are significant because these beliefs will guide their behavior and actions in the future. This especially applies to organic agriculture, which occupies an important place in EU agricultural policy. The awareness of organic producers about CAP, the possibilities within this policy and the benefits it brings to organic production as well as their general attitude towards the agricultural policy is a significant indicator of the current situation among producers and is a basis on which future trends in this production system can be based.

The results showed that organic producers in the Republic of Serbia, first, are not sufficiently familiar with the CAP to be able to have a relevant opinion on the importance of this policy. They believe that entry into the European Union will not significantly change the situation for organic producers, although, at the same time, they state that they believe that organic producers are in a better position in the EU compared to Serbia. Also, the majority believe that the agrarian policy of the Republic of Serbia is generally not favorable for organic producers. The research showed that funds allocated to organic production in the Republic of Serbia have increased significantly in the last two years, and the task of future research is to determine whether this will impact the increase in the area under this production.

Based on all of the above, it can be concluded that organic producers in Serbia do not have a positive attitude towards institutional support and that they consider it insufficient. Also, producers are not sufficiently familiar with the CAP concept and the opportunities that this policy offers for organic production. Accordingly, their attitude towards the agricultural policy and the CAP can be interpreted as a limiting factor in the further development of organic production and it is necessary to work on it, with continuous measures from competent ministries, local self-governments, and advisory services. The findings underscore the importance of understanding farmers’ perspectives in shaping agricultural policies. Insights from the study can inform policy adjustments aimed at better aligning incentives with the needs and priorities of organic producers while fostering the development of sustainable agricultural practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T.S. and D.M.; methodology, D.N. and T.N.; software, D.N.; validation, M.T.S., D.M. and V.Z.; formal analysis, D.N.; investigation, M.T.S. and T.N.; resources, M.T.S. and D.N.; data curation, M.T.S. and D.N.; writing—original draft preparation, M.T.S.; writing—review and editing, D.N. and D.M.; supervision, V.Z.; project administration, M.T.S. and T.N.; funding acquisition, D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Provincial Secretariat for Higher Education and Scientific Research of Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, grant number 142-451-3057/2023-01/01.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations (UN). Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Reppeto, R. The Global Possible-Resources, Development and New Century. In World Resources Institute Book; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Jovanović-Gavrilović, B. Sustainable Development—Conceptual and Methodological Issues (Održivi razvoj—Konceptualna i metodološka pitanja). Ecologica 2003, 10, 39–40. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Harris, J. Economics of Environment and Natural Resources—Contemporary Approach (Ekonomija Životne Sredine i Prirodnih Resursa-Savremeni Pristup); Datastatus: Belgrade, Serbia, 2009. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, E.; Sultan, R.; Hilliker, A. Negative Effects of Agriculture on Our Environment. Traprock 2004, 3, 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lazić, B.; Babović, J.; Sekulić, P.; Malešević, M.; Lazić, S.; Đurovka, M.; Lazarević, R. Organic Agriculture (Organska Poljoprivreda); Institute of Field and Vegetable Crops: Novi Sad, Serbia, 2008; pp. 7–38. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Kovačević, D.; Lazić, B.; Milić, V. The impact of agriculture on the environment, International Scientific Meeting of Agronomists (Uticaj poljoprivrede na životnu sredinu, Međunarodi naučni skup agronoma). Proc. Plenary Lect. Jahorina 2011, 34–47. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Praneetvatakul, S.; Schreinemachers, P.; Pananurak, P.; Tipraqsa, P. Pesticides, external costs and policy options for Thai agriculture. Environ. Sci. Policy 2013, 27, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyraud, J.L.; Taboada, M.; Delaby, L. Integrated crop and livestock systems in Western Europe and South America: A review. Europ. J. Agron. 2014, 57, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajewski, P. Agricultural Biodiversity for Sustainable Development. Probl. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 12, 135–141. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, J.; Crowther, S. Biotechnology: The ultimate cleaner production technology for agriculture? J. Clean. Prod. 1998, 6, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewalter, J.; Leng, G. Consideration of individual susceptibility in adverse pesticide effects. Toxicol. Lett. 1999, 107, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, A.; Aronson, K.J.; Patil, S.; Hugar, L.B.; Vanloon, G.W. Emerging health risks associated with modern agricultural practices: A comprehensive study in India. Environ. Res. 2012, 115, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lampkin, N.; Padel, S. The Economics of Organic Farming, an International Perspective; CAB International: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchesne, A.; Bryant, C. Agriculture and innovation in the urban fringe: The case of organic farming in Quebec, Canada. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. En Soc. Geogr. 1999, 90, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifrić, I. Značaj iskustva seljačke poljoprivrede za ekološku poljoprivredu (Significance of peasant farming experience for ecological agriculture). In Sociologija i Prostor (Sociology and Space); Institut za društvena istraživanja: Zagreb, Croatia, 2003; pp. 5–27. [Google Scholar]

- Rodić, V.; Bošnjak, D.; Vukelić, N. Održivost upravljanja poljoprivrednim zemljištem u AP Vojvodini (Sustainability of agricultural land management in AP Vojvodina). Agroekonomika 2008, 37–38, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Baćanović, D. Indicators of Sustainable Development and Assessment of the Level of Sustainability of AP Vojvodina Development (Indikatori Održivog Razvoja i Procena Nivoa Održivosti Razvoja AP Vojvodine). Ph.D. Thesis, ACIMSI Environmental Engineering, Novi Sad, Serbia, 2004. (In Serbian). [Google Scholar]

- Rigby, D.; Caceres, D. Organic farming and the sustainability of agricultural systems. Agric. Syst. 2001, 68, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolze, M.; Piorr, A.; Haring, A.; Dabbert, S. Environmental impacts of Organic Farming in Europe; Organic Farming in Europe: Economics and Policy; Department of Farm Economics, University of Hohenheim: Stuttgart, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kaspercyzk, N.; Knickel, K. Environmental impacts of organic farming. In Organic Agriculture a Global Perspective; Kristiansen, P., Taji, A., Reganold, J., Eds.; CABI: Bakeham Lane, UK, 2006; pp. 259–295. [Google Scholar]

- Pacini, C.; Wossink, A.; Giesen, G.; Vazzana, C.; Huirne, R. Evaluation of sustainability of organic, integrated and conventional farming systems: A farm and field scale analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2003, 95, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaš Simin, M.; Rodić, V.; Glavaš-Trbić, D. Organic agriculture as an indicator of sustainable agricultural development: Serbia in focus. Ekon. Poljopr. 2019, 66, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajković, M.; Malidža, G.; Tomaš Simin, M.; Milić, D.; Glavaš-Trbić, D.; Meseldžija, M.; Vrbničanin, S. Sustainable Organic Corn Production with the Use of Flame Weeding as the Most Sustainable Economical Solution. Sustainability 2021, 13, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radojević, V.; Tomaš Simin, M.; Glavaš-Trbić, D.; Milić, D. A Profile of Organic Food Consumers—Serbia Case-Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, D. Organic farming and society: An economic perspective. In The Economics of Organic Farming, an International Perspective; Lampkin, N., Padel, S., Eds.; CABI Publishing: London, UK, 1994; pp. 45–71. [Google Scholar]

- Lockie, S.; Halpin, D. The ‘Conventionalisation’ Thesis Reconsidered: Structural and Ideological Transformation of Australian Organic Agriculture. Sociol. Rural. 2005, 45, 284–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampkin, N. Organic farming. In The Countryside Notebook; Soffe, R.J., Ed.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 181–198. [Google Scholar]

- Šeremešić, S.; Dolijanović, Ž.; Tomaš Simin, M.; Vojnov, B.; Glavaš Trbić, D. The Future We Want: Sustainable Development Goals Accomplishment with Organic Agriculture. Probl. Ekorozwoju—Probl. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 16, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaš Simin, M.; Glavaš-Trbić, D.; Petrović, M. Organska proizvodnja u Republici Srbiji—Ekonomski aspekti (Organic production in the Republic of Serbia—Economic aspects). Ekon.—Teor. Praksa 2019, 12, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milić, D.; Tomaš Simin, M. Nove Perspektive u Poljoprivredi—Ekonomski Aspekti (New Perspectives in Agriculture—Economic Aspects); Poljoprivredni Fakultet (Faculty of Agriculture): Novi Sad, Serbia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wynen, E. Economics of Organic Farming in Australia. In The Economics of Organic Farming—An International Perspective; Lapmkin, N., Padel, S., Eds.; CABI: Bakeham Lane, UK, 1994; pp. 185–199. [Google Scholar]

- Greer, G.; Kaye-Blake, W.; Zellman, E.; Parsonson-Ensor, C. Comparison of the financial performance of organic and conventional farms. J. Org. Syst. 2008, 3, 18–28. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, K.; Murdoch, J. Organic vs. conventional agriculture: Knowledge, power and innovation in the food chain. Geoforum 2000, 31, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padel, S.; Lamkin, N. The development of governmental support for organic farming in Europe. In Organic Farming—An International History; Lockeretz, W., Ed.; CABI: Bakeham Lane, UK, 2007; pp. 93–122. [Google Scholar]

- Dabbert, S.; Häring, A.M.; Zanoli, R. Organic Farming—Policies and Prospects; Zed Books: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanov, N.; Sredojević, Z.; Rodić, V. Ekonomski Aspekti Organske Poljoprivrede u Srbiji, Organska Poljoprivredna Proizvodnja (Economic Aspects of Organic Agriculture in Serbia, Organic Agricultural Production); Kovačević, D., Oljača, S., Eds.; Poljoprivredni Fakultet (Faculty of Agriculture): Beograd-Zemun, Serbia, 2005; pp. 261–301. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitri, C.; Oberholtzer, L. Market-Led versus Government-Facilitated Growth: Development of the US and EU Organic Agricultural Sectors; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stolze, M.; Sanders, J.; Kasperczyk, N.; Madsen, G.; Meredith, S. CAP 2014–2020: Organic Farming and the Prospects for Stimulating Public Goods; IFOAM EU: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Niggli, U.; Slabe, A.; Schmid, O.; Halberg, N.; Schlüter, M. Vision for an Organic Food and Farming Research Agenda to 2025—Organic Knowledge for the Future; IFOAM EU Group: Brussels, Belgium; ISOFAR: Westerau, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaš Simin, M.; Milić, D.; Petrović, M.; Glavaš-Trbić, D.; Komaromi, B.; Đurić, K. Institutional development of organic farming in the EU. Probl. Ekorozwoju—Probl. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 18, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottazzi, P.; Seck, S.M.; Niang, M.; Moser, S. Beyond motivations: A framework unraveling the systemic barriers to organic farming adoption in northern Senegal. J. Rural. Stud. 2023, 104, 103158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berckmans, E.; Cuoco, E.; Gall, E. Organic in Europe—Prospects and Developments for Organic in National CAP Strategic Plans; IFOAM: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://www.organicseurope.bio/content/uploads/2021/06/ifoameu_advocacy_CAP_StrategicPlansAnd25Target_202106.pdf?dd (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Guth, M.; Stępień, S.; Smędzik-Ambroży, K.; Matuszczak, A. Is small beautiful? Techinical efficiency and environmental sustainability of small-scale family farms under the conditions of agricultural policy support. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 89, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindström, H.; Lundberg, S.; Marklund, P.O. How Green Public Procurement can drive conversion of farmland: An empirical analysis of an organic food policy. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 172, 106622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, A.; John, J. Including farmers’ welfare in a government-led sector transition: The case of Sikkim’s shift to organic agriculture. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 411, 137207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simić, I. Organska Proizvodnja u Srbiji 2020; Nacionalno udruženje za razvoj organske proizvodnje Serbia Organica: Beograd, Serbia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Water Management, Group for Organic Production. Available online: http://www.minpolj.gov.rs/organska/?script=lat (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Pandis, N. The chi-square test. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2016, 150, 898–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maroof, D.A. Binary logistic regression. In Statistical Methods in Neuropsychology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Law on Agriculture and Rural Development (“Off. Gazette of RS”, No. 41/09, 10/13 and 101/16–Other Law). Available online: https://www.paragraf.rs/propisi/zakon_o_poljoprivredi_i_ruralnom_razvoju.html (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Law on Subsidies in Agriculture and Rural Development (“Off. Gazette of RS”, No. 10/13, 142/14, 103/15 and 101/16). Available online: https://www.paragraf.rs/molovani/zakon-o-podsticajima-u-poljoprivredi-i-ruralnom-razvoju.html (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- IFOAM: Evaluation of Support for Organic Farming in Draft CAP Strategic Plans (2023–2027). Available online: https://www.organicseurope.bio/content/uploads/2022/03/IFOAMEU_CAP_SP_feedback_20220303_final.pdf?dd (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Quandt, A. “You have to be resilient”: Producer perspectives to navigating a changing agricultural system in California, USA. Agric. Syst. 2023, 207, 103630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, G.; Campobasso, F.; Laureti, L.; Frittelli, M.; Valente, D.; Petrosillo, I. The environmental impact of agriculture: An instrument to support public policy. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 147, 109961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timpanaro, G.; Scuderi, A.; Guarnaccia, P.; Foti, V.T. Will recent world events shift policy-makers’ focus from sustainable agriculture to intensive and competitive agriculture? Heliyon 2023, 9, e17991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.; Kovács, E.; Herzon, I.; Villamayor-Tomas, S.; Albizua, A.; Galanaki, A.; Grammatikopoulou, I.; McCracken, D.; Olsson, J.A.; Zinngrebe, Y. Simplistic understandings of farmer motivations could undermine the environmental potential of the common agricultural policy. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilpoux, O.F.; Gonzaga, J.F.; Pereira, M.W.G. Agrarian reform in the Brazilian Midwest: Difficulties of modernization via conventional or organic production systems. Land Use Policy 2021, 103, 105327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, A.; Coletta, A.; Severini, S. The distortive effect of organic payments: An example of policy failure in the case of hazelnut plantation. Land Use Policy 2022, 119, 106202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).