Abstract

The application of sustainability practices has become one of the key drivers to gaining a favorable stand in the market. However, petroleum companies are hesitant with its implementation due to the perceived negative financial impact. This study was conducted to determine the purchase intentions of consumers from petroleum stations implementing sustainability practices by utilizing the pro-environmental planned behavior (PEPB) framework. The research utilized an online questionnaire with 400 respondents who have been a petrol station customer. The data were examined with a higher-order construct using partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM). The findings showed a positive relationship between variables and revealed that economic concern, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, economic factors, and sustainable knowledge significantly influenced customers’ intention to purchase goods and services from a petrol station adopting sustainability practices, while attitude was found to have no direct significant impact on customers’ intention. The results of this study adds value to the potential increase in PEPB understanding and consumer behavior and may be beneficial for petroleum companies as the basis for managerial decisions regarding the implementation of sustainability practices or initiatives towards adopting the concept of “green stations” and consumer preferences to attract purchase intentions.

1. Introduction

The increasing competitiveness among businesses made experts and scholars look for new levers to increase business success. To dominate and survive a competitive scenario, companies seek alternative actions to find the balance to achieve a favorable stand in the market to ensure continued success. One of the common practices adopted by companies to attract market share is through sustainability, which provides multi-social benefits [1]. However, it is default to know that the main goal of sustainability is to defend the environment. The grasp on the benefits coming from the trail of sustainability has expanded in various sectors where people are actively demanding sustainable practices and behaviors [2]. However, some companies, such as petroleum stations, are hesitant to implement sustainability practices due to the perception of negative financial impacts and industry heads’ lack of understanding of how environmentally inclined sustainable practices can affect profitability [3].

A petroleum station, commonly known as a service station, fuel station, gas or gasoline station, is a roadside facility where vehicles are refueled, serviced, and receive other forms of repairs [4]. Petroleum stations have also become a frame of retail that has grown throughout the years. They are no longer accompanied by the retail of oil products and basic services for vehicles, but now have coffee offers and rest areas alongside the store, offering a wide choice of food and beverages. Although these developments and trends improved business activities, the increase in adapting to different circumstances and diversification of consumers’ needs makes a challenge to compete strongly in the market with consumers’ growing demands, especially on sustainability practices. This may be due to people having realized that society cannot continue its current course of being unethically involved in environmental problems amidst globalization [5]. Hence, sustainability has become one of the most sought-after preferences of consumers in purchasing goods, services, or even going to places [5] such as petroleum stations. This poses a question for petroleum companies in terms of if they should adhere to adopting sustainability practices to stay in a positive market position and more so gain more shares.

In the Philippines, the growth of petroleum companies has resulted in a steady market. In a 2021 Statista survey, the market was dominated by local players, commonly known as white stations, accounting for 52.69% share in the market, while big brands like Petron, Shell, and Chevron had a market share of 19.17%, 14.96%, and 5.31%, respectively. These companies are likely to compete with one another to gain a favorable stand in the market. This makes companies pressured into adopting innovative solutions, such as sustainability practices, to gain this stand in the market. Although several can manage using alternative policy options, carbon taxes, energy efficiency, and development of renewables [6], only a few are holistically implementing these because of the perceived negative financial impacts. These solutions can also be easily implemented by big companies with higher capital and market share. However, accounting for the fact that a large portion of these companies are from local brands, the implementation is somewhat questionable. Hence, assessing the link between sustainability implementation and profitability is deemed important for these companies.

Despite the abundant research on sustainability and profitability through purchase intentions in many different sectors, such as hotel management [7], transportation [8], agricultural products [9] and other fields, the literature that discusses petroleum stations is scarce. Most research about petroleum stations focuses on understanding profits in petroleum extraction and its effect on the environment [10], sustainability dimensions emphasized in the oil and gas industry [11], and the environmental effects of petrol stations [12].

Some research has discussed the profitability of petroleum stations, such as the studies of Manneh [13], which focus on the determinants of consumer preference for petrol consumption, and Hong et al. [14], who discusses how consumers’ patronage influences behavior towards petrol stations. Furthermore, a study that incorporated sustainability through the concept of renewable energy design was conducted by Raed et al. [15]. These studies do not reflect a holistic approach and a perception of the relationship between sustainability and profitability. Hence, its importance to petroleum companies becomes an open question. This uncertainty fosters a business problem for petroleum companies, questioning its implementation. Furthermore, no existing literature during the conduct of this research was known to discuss petroleum stations’ sustainability practices related to profitability. Thus, the consolidation and application of different theories is necessary to fill this gap to provide a sufficient distinction on whether sustainability practices for petroleum stations are profitable.

This study was conducted to determine the purchase intentions of consumers from petroleum stations implementing sustainability practices by utilizing the pro-environmental planned behavior (PEPB) framework. The study examined the influences of perceived environmental concern (EC), attitude towards sustainability (ATT), subjective norms (SN), perceived behavior control (PBC), and behavior intention (BI) under the PEPB theory developed by Persada (2016). The study extended the model with relevant variables: (i) sustainable knowledge (SK) that includes four (4) dimensions: solar PV system, rainwater harvesting, green products, and green roof; and (ii) economic factors (EF) composed of four (4) dimensions: payment incentives, urbanization, employment, and willingness to pay. This study is motivated by two (2) main guide questions: (i) what are the factors influencing consumers’ preference for a petrol station and (ii) does consumers’ perception of petrol stations’ pro-environmental activities affect their behavior?

The research framework adds value to the potential to increase the understanding of the PEPB literature, therefore identifying key factors influencing PEPB in the research context by incorporating specific sustainability practices and consumer economic factors. This contributes to consumer behavior modelling by sustainability practices recognition in the selection and purchase of products from a petroleum station. The research findings may be advantageous to gas station owners by providing insights into how to maintain customer base and attract new customers, particularly for small and medium-sized companies with limited capital for sustainability implementation. In addition, the results of this study may be beneficial for petroleum companies as a basis for managerial decisions regarding the implementation of sustainability practices or initiatives towards adopting the concept of “green stations” and consumer preferences to attract purchase intentions. The establishment of sustainable development for petroleum stations affords management the opportunity to educate the public about PEPB and sustainability as well. Lastly, local or national authorities may find the study useful for future green station implementation throughout the country by establishing policies that delegate environmental protection and market education not limited to petroleum stations but to different business sectors.

2. Review of the Related Literature

2.1. Pro-Environmental Planned Behavior

Persada [16] developed an extended model of Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior known as pro-environmental planned behavior (PEPB), which comprises six different factors, such as perceived environmental concern (PEC), perceived authority support (PAS), perceived behavior control (PBC), subjective norm (SN), attitude (ATT), and behavior intention (BI). This study utilized five of the six factors mentioned.

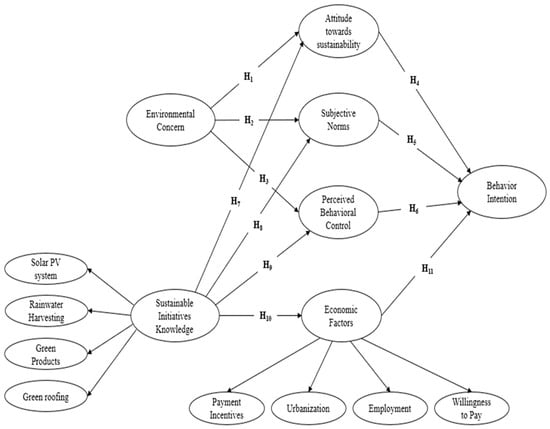

The framework presented in Figure 1 is based on the theoretical models mentioned in this research, illustrated showing varying variables’ interrelationship. This includes variables of PEPB such as EC, ATT, SN, PBC, and the dependent variable behavior intention. It also includes two (2) extended independent variables, namely (i) sustainable initiative knowledge with four variables, i.e., solar PV system, rainwater harvesting, green products, and green roof; and (ii) economic factor with four variables, i.e., payment incentives, urbanization, employment, and willingness to pay. The framework’s purpose is to investigate the variables’ relationship.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework based on the PEPB extended model theory.

2.1.1. Perceived Environmental Concern

It is said to be an essential factor that helps change the behavior of a person to be environmentally friendly [17] Accordingly, it is one of the most influential determinants of environmentally responsible consumer norms when there is more concern a person has, the more favorable consumers are towards sustainable products.

Accordingly, Aman et al. [18] found that highly environmentally concerned consumers have a more favorable attitude towards sustainable products. In this regard, consumers frequently choose green products over conventional ones. Lai et al. [19] also recommended that attitude, norms, and beliefs influence direct or indirect factors of behavior intention. This research considers that environmental concern has a positive effect on ATT, SN, and PBC to adopt sustainability. The following hypotheses were proposed establishing from the above statement:

H1:

Environmental concern has a positive relation with attitude towards adopting sustainable solutions.

H2:

Environmental concern has a positive relation with subjective norms towards supporting sustainable solutions.

H3:

Environmental concern has a positive relation with perceived behavioral control towards implementing sustainable solutions.

2.1.2. Attitude towards Sustainable Solutions

Ajzen [20] defined attitude as the scale to which a person evaluates behavior favorably or not. Thus, it is scrutinized as an analysis of a person’s reaction toward performing an act that manifests a propensity to react to a behavior [21]. Some studies suggest that attitude is one of the most consistent predictors of consumers’ willingness to pay for environmentally friendly products [22] and hence indicates that cost is not always the primary factor for consumers in considering buying a product, regardless of if they are environmentally conscious or not. Therefore, this study outlined attitude as a subjective disposition to favor or oppose sustainable solutions. Thus, the following was hypothesized:

H4:

Attitude is positively related to the use of sustainable solutions leading to behavior intention.

2.1.3. Subjective Norm

Karaiskos et al. [23] identified subjective norm (SN) as a significant factor of intent. This concept was apparent in a research variety dealing with the technology acceptance and utilization and purchasing intent of consumers. Jung et al. [24] demonstrated wearable augmented reality intended use, which indicated that SN significantly affected the prediction of the technology usage intention. Conversely, Nguyen et al. [25] examined users of functional yogurt where it showed that SN is an important predictor of intention. Another study conducted by Choi and Park [26] regarding the behavioral intentions of online duty-free shoppers in which the findings also showed that SN has a significant influence on consumers’ behavioral intentions. Therefore, this study defined subjective norms as a significant factor to pro-environmental behavior and purchase intentions. Thus, the following was hypothesized:

H5:

Subjective norm is positively related to the use of sustainable solutions, leading to behavior intention.

2.1.4. Perceived Behavior Control

One of the plausible aspects of intention [20] was transparent in Zhang et al. [27]’s energy research, in which they discovered that behavioral control has a substantial impact on the type of behaviors and intentions within a Chinese nuclear facility. Hua and Wang [28] assessed public support for a waste-to-energy project, and the findings revealed that PBC influenced the project’s behavior intention. In the same year, Karaiskos et al. examined the consumers’ intent to purchase energy-efficient appliances, and it was shown that it was an aspect that had a direct and significant effect on the consumers’ purchase intentions. Therefore, this study defined perceived behavior control as an important contributing factor to pro-environmental behavior and purchase intentions. Hence, the following was hypothesized:

H6:

Perceived behavioral control is positively related to the use of sustainable solutions leading to behavior intention.

2.1.5. Behavior Intention

Mamman et al. [29] described intention as a person’s tendency towards the willingness to demonstrate a certain behavior. Various research has demonstrated that this concept influences the acceptance of a particular subject. In 2014, a study by Park and Ohm [30] discovered that perceived trust, risk, attitude, and intention used to explain the public’s acceptance of renewable energy have multidimensional matrices. According to Xiao et al. [31], a study about the acceptance of nuclear technology revealed that participants accept the concept due to trust in goodwill and proficiency. Similarly, Lim et al. [32] discovered that individuals less susceptible to risks in power plants are more likely to accept it.

Recent research has also demonstrated that the TPB model is one of the models that can accurately predict the purchase or usage intention and customer satisfaction with various products and services. In 2021, Carfora et al. [33] analyzed consumers’ intention to purchase organic milk, and they discovered that both PBC and SN were key determinants of the intention. Moreover, findings from the research of Qi and Ploeger [34] support this conclusion as their research indicated that TPB factors strongly influenced and had positive effects on consumer purchase intentions.

2.2. Independent Variables: Sustainable Initiatives

2.2.1. Solar PV System

Solar is considered an essential means to decrease emissions and balance environmental, social, and economic aspects of its adoption that enhance energy reserves [35]. Hence, this study considered it as a crucial contributing part of sustainable initiatives.

Solar photovoltaic is a clean energy form, converting sunlight to energy, that causes a reduction in imported oil costs and carbon emissions. It is one of the cheapest renewable energy sources that helps maintain stable electricity rates [36]. However, not all are able to positively attract interest from consumers. Public acceptance of solar infrastructures has been established in civilized countries [37]. However, in some countries, its application is impeded due to low acceptance, hence obstructing the development of essential environmental goals [36].

To increase demand of solar PV in different marketing scenarios, local obstacles must be overcome, including the knowledge of people towards solar PV, their attitudes towards it, and the norms accustomed to the use of solar energy.

2.2.2. Rainwater Harvesting

In a report mentioned by Stocker et al. [38], the IPCC of 2007 mentioned that rainwater harvesting is one of the specific adaptive plans to manage climate change. Hence, this research considered it as a crucial contributing part of sustainable initiatives.

Rainwater harvesting (RWH) is likely the world’s oldest technique for addressing water supply requirements. It is a technique used to gather rainwater from specified catchments, such as rooftops and land surfaces, utilizing simple to complex equipment and procedures [39]. Although, in recent years, because of technological advancements, several countries have supported the modernization of this practice in response to the rise in pressure of water demands caused by various changes [40]. Its purpose is to minimize the use of freshwater from centralized sources. Therefore, rainwater systems boost self-sufficiency and put off the need to build new sources [41]. Nonetheless, in recent years, research has focused on its environmental advantages, including carbon emissions’ reduction and lowering resource consumption (e.g., Angrill et al. [42]). Thus, RWH offers a renewable source of potable water suitable for many applications.

The literature unequivocally demonstrates that the spectrum of RWH application in urban settings is vast. Nevertheless, the outcome and perception of its numerous potential advantages are diverse and debatable.

2.2.3. Green Products

Sustainability cannot be realized when products cause significant damage to the environment [43]; hence, it is apparent to know the value of green products as they have similar functions to conventional ones, although their impact on the environment is reduced. Hence, this research considered it to be a crucial contributing part of sustainable initiatives.

Green products are commonly referred to as recycled resources that include benefits for the environment during their life cycle [44]. An increase in green product development has been seen where sustainable development becomes more relevant. As a result, research regarding green products has increased substantially over the decades [45]. Similarly, potential growth in the market was visible, which can contribute to more economic growth [46] given the increase in consumption of green products in many industries.

Studies like that by Ottman [47] observed that when a consumer’s primary need for performance, quality, convenience, and costs are indicated in an environmentally friendly product, consumers often accept its use. Studies conducted by Johri and Sahasakmontiri [48] concluded that in Thailand, large corporations were successful in boosting environmental awareness among Thai consumers, resulting in improved consumer attitude towards green products. Hence, customers can alter their preferences towards environmentally friendly goods and more decisions are now made towards the use of green products.

2.2.4. Green Roofing

It is one of the highest potential keys to address environmental problems within existing communities [49], and thus has gained increasing attention due to its environmental and social benefits. Hence, this research considered it a crucial contributing part of sustainable initiatives.

These are plant systems grown into roofs using system-layered engineering mediums, which are considered one of the contributors of environmental preservation [50]. Shafique et al. [51] stated that green roofs provide an aesthetic appearance to urban areas, bringing also several social and economic benefits. It was also concluded in some research that there was an increase in marketability for designated green land and buildings [52].

Based on the above discussion, generalizing the four mentioned sustainable practices into one, the following hypothesis are proposed:

H7:

Sustainable practice knowledge has a positive relation with attitude towards adopting sustainable solutions.

H8:

Sustainable practice knowledge has a positive relation with subjective norm towards supporting sustainable solutions.

H9:

Sustainable practice knowledge has a positive relation with perceived behavioral control towards implementing sustainable solutions.

H10:

Sustainable practice knowledge has a positive relation with economic factors affecting behavior intention.

2.3. Independent Variables: Economic Factors

2.3.1. Payment Incentives

Incentives give a steady economic signal to influence behavior [53]. Some studies indicated that some strategies, such as Pay-as-You-Throw (PAYT), provide significant factors that predict positive behavior in recycling manners [54]. Even though it has ephemeral impacts, it continues to play an essential part in determining behavior. A study by Timlett and Williams [55] revealed that the incentive model was the most influential factor in determining the recycling rate in England. Now, it is considered a useful tool in altering behavior in recycling trash [56]. Hence, this study anticipated that incentives could assist with the adoption and utilization of sustainable practices that lead to a pro-environmental behavior intention.

2.3.2. Urbanization

Urbanization is a potential way to develop and identify high-quality economic growth. Although urbanization fosters economic development, it also results in substantial resource depletion, energy use, and degradation of the environment [57]. Most of the proposed solutions to environmental issues, along with the implementation of sustainability, are dependent on the authorities and the participation of commercial and public sectors. Hence, it is important to examine its effect on pro-environmental behavior and how it enhances PEB during urbanization process.

Few studies have examined the benefits of urbanization in the environment, particularly its effect on PEB, and most look over its stress on assets and the environment. Although its association with PEB was not discussed in any PEB research, it has primarily emphasized distinct features such as awareness and attitude [58].

The unavoidable process of urbanization has produced environmental degradation, but it may also improve PEB. For instance, the affluence hypothesis asserts that from a macro-perspective, the success of a country is conclusively connected with its pro-environmental consciousness and PEB [59].

It may therefore increase PEB while adding value to financial growth. Studies suggested that common literacy and social security can considerably enhance PEB [60]. At some point, urbanization adds to education; adequate literacy can promote PEB [58] through accessing pro-environmental knowledge and higher levels of pro-environmental awareness. Its facets have varying effects on PEB, such as the moderating effects of urbanization between individual variables, although PEB has not been thoroughly examined in prior studies. Therefore, urbanization can theoretically have diverse effects on pro-environmental behavior.

2.3.3. Employment

As economic operations change to include capital and technological means to meet society’s environmental sustainability needs, labor expectations also progress. Understanding job performance characteristics is necessary for integrating environmentally responsible practices into jobs.

According to Ones et al. [61], green jobs are currently developing jobs that exist to fill in environmental sustainability work gaps. These are also those that require skill upgrades to satisfy sustainability-related requirements (e.g., architects to design energy efficient buildings). Therefore, the intensity and range of skill requirements are enhanced.

Greening economy jobs are traditional jobs where demand is growing to satisfy the needs of the green industry as economies undertake environmental sustainability transitions (e.g., clerical workers in recycling companies). For these tasks, it is not envisaged that any aspects of task performance will emphasize environmentally friendly task performance. However, there may be a greater desire for employees to engage given the emphasis and concerns of green organizations.

2.3.4. Willingness to Pay

This has been studied in various settings for green initiatives, such as the packing of products [62] and air travel materials [63]. Most research is patterned on Ajzen’s [20] TPB that posits that a person’s intentions are decided by their attitude towards the behavior, norms, and behavioral control.

One example study is by Millar and Mayer [64], which investigated the relationship between WTP and environmental views and beliefs. Numerous studies have examined individuals’ purchase intentions of renewable resources (e.g., Aravena et al. [65]) using preferential questionnaires to determine people’s WTP for a future change in non-market goods or services. Paying extra taxes or costs for environmentally friendly products is another example where the primary goal is to include the external costs to produce environmental products to consumers. Similarly, environmentally friendly materials prices are higher than conventional products to support its production process. Despite the cost, many individuals prefer to purchase these items because their health and environmental benefits are anticipated to outweigh its costs. The desire to pay higher prices has been a gauge of public support for policies related to the environment since its acceptance is related to financing it willingly [66].

Cost is always a factor for consumers’ willingness to buy a product; thus, the intention to purchase might be contingent on this factor. Prior to implementing green initiatives to entice individuals to engage in environmentally friendly acts, it is crucial to understand their willingness to pay for these initiatives. This research aims to investigate the relationship between willingness to pay leading to pro-environmental behavior intention. Based on the above discussion, generalizing the four mentioned economic factors into one, the proposed hypothesis is as follows:

H11:

Economic factors are positively related to adopting the behavior intention.

3. Methodology

This study was approved by Mapua University Research Ethics Committees (FM-RC-23-34), and informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the data collection.

3.1. Sampling Design

3.1.1. Target Population

The key purpose of this research is to examine the pro-environmental behavior of petroleum station Filipino consumers that affect their purchase intention. Therefore, the relevant target population were Filipinos residing in the Philippines.

3.1.2. Sampling Technique and Size

Purposive sampling was used in the research to represent most of the population who are informed of a certain topic [67]. The criteria to qualify as a respondent are as specified:

- Must be a Filipino citizen living in the Philippines.

- Must be 18 years old and above.

- Familiar with the specified sustainability practices and is a frequent petroleum station customer as a driver, passenger, or walk in.

The sampling was conducted through the distribution of questionnaire in a span of 3 months, from 15 February to 15 May 2023. The research utilized the use of Google Forms to distribute the questionnaire through various social platforms, such as Facebook. The sample was obtained using the Taro Yamane method found in Equation (1).

where

- n = sample size

- N = population under study

- e = margin of error

Based on the 2015 POPCEN [68], citizens aged 18 years old and above have a total population of 68.8 million, and the total sample size with a 95% accuracy is 400.

3.2. Research Instruments

3.2.1. Questionnaire

The questionnaire includes two (2) sections: the demographics and PEPB model. The first part of the questionnaire included a pre-assessment question to determine the level of knowledge of the participant relative to the survey. The demographics also included the gender, age, civil status, residence, education level, employment, monthly income, and if they were a vehicle owner. Section two (2) was divided into seven sub-areas, representing the variables of PEPB. EC, ATT, and PBC have four (4) constructs, while SN has three (3) constructs. Sustainable practices have four (4) dimensions: SP, RH, MS, and GR with four (4) constructs each. Economic factors with have (4) dimensions: PI, U, E, WTP has three (3) constructs each and BI has five (5) constructs. The questionnaire utilized a 5-point Likert Scale (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) for construct evaluation. The constructs were adopted and adjusted accordingly to the purpose of the research based on the presented literature in Table 1. Moreover, structural equation modelling (SEM) was utilized.

Table 1.

Construct and Measurement Items.

3.2.2. Structural Equation Modelling

The collected data were evaluated via structural equation modeling (SEM). A partial least squares (PLS-SEM) model was used in this work to investigate correlations between abstract notions [84], which is known to provide better reliability and validity in composite-based models. Given the exploratory nature of the research and based as an extension of an existing theory [85], PLS-SEM was fit to be used in the analysis. The sample size was also considered, whereas PLS-SEM was the best to produce a high level of statistical power [86]. In addition, the data set was not normally distributed, hence PLS-SEM seemed fit since it does not assume normally distributed data. Similar studies, such as [80,87], that focus on extended PEPB models also employed PLS-SEM to analyze data. Both studies showed satisfactory results and hence were considered as a factor in this study to use a similar approach.

Several studies have been conducted using SEM in the domain of sustainability. Lin and Syrgabayeva [88], for example, focused on consumers’ willingness to pay extra for green energy. The study shows that there is a positive influence on attitude with consumers concern about renewable energy and improved their beliefs in environment and willingness to pay more. In 2015, Wan and Shen [89] examined the relationship between green building attributes and its uses using mediating effects, such as perceived usefulness, attitude, and perceived behavioral control. The findings exhibited that the variables have a mediating effect on behavior. The study also found that green buildings have no indirect effect on behavior via attitude characteristics and perceived behavioral control.

3.2.3. Higher-Order Construct Analysis

Researchers gradually moved from simple models into advanced models since PLS-SEM became widespread, such as higher-order constructs [90]. The higher-order constructs given in this study were of the reflective–reflective type, which has been widely employed in a variety of domains [91] and employs higher and lower-order constructs with reduced path model linkages. The first latent variables considered to be reflective higher-order constructs are sustainable initiative knowledge with solar PV panels, rainwater harvesting, green products, and green roof as reflective constructs. The second higher-order constructs are economic factors with urbanization, payment incentives, employment, and willingness to pay as its reflective constructs.

The higher-order constructs in this study were specified and determined using a two-stage approach as it shows a better path parameter recovery with each path model [92]. Hence, the study recommended the use of a two-stage approach.

3.3. Pilot Data Analysis

The pilot test considered 10% [93] (40 participants) of the study’s sample to verify the reliability and validity of the questionnaire.

Reliability and Validity Test

The use of Cronbach’s Alpha determined the consistency of the questionnaire. Shown in Table 2 is the summary of the pilot questionnaire.

Table 2.

Reliability of Pilot Test Questionnaire.

The reliability test was conducted on an overall basis to ensure that each construct passes. The values for each construct were 0.871, 0.819, 0.756, 0.796, 0.935, 0.927, 0.901, 0.764, 0.845, 0.790, 0.833, 0.879, and 0.929, respectively, while the total had a value of 0.957. Based on these values, all constructs had good to excellent reliability, while the total had an excellent level of reliability.

4. Results

4.1. Respondents’ Demographic Profile

This study utilized the PEPB model and extended it with sustainability practice and economic factor variables to determine the purchase intentions of Filipino consumers from petroleum stations implementing sustainability. A total of 400 people freely completed the Google Forms-based survey questionnaire. Table 3 illustrates the demographic characteristics of the responders. From which, 59.50% were female, 38.50% were male, and 2% preferred not to state their gender. In terms of age, most of the participants were from the Generation Z and millennial bracket with 43.75% and 41.50%, respectively, while the Generation X bracket had 8.75%, and the Baby Boomer bracket had 6%. Regarding civil status, most of the respondents were single (71.25%), followed by married (27%); very few were separated (1%) or widowed (0.75%). Concerning the area of residence, most resided in the NCR (48.50%), followed by Region 4A (33.50%), Region 3 (9.75%), and a few collectively from other regions of the country accounting for 8.25% of the respondents. Regarding education level, 64.50% finished an undergraduate degree, 23% either completed high school or went to high school, 11.75% were postgraduates or studying at postgraduate level, and only 0.75% attended grade school. In terms of employment, 52.75% were employed in either private or public institutions, while 13.50% were self-employed or engaged in their own business, and 33.75% were either a student or currently unemployed. Concerning monthly income, most of the respondents earned or had a monthly allowance below PHP 10,957 (29.75%), followed by PHP 21,914 to PHP 43,828 (28.75%), PHP 10,957 to PHP 21,914 (16.50%), while some earned PHP 43,828 to 76,669 (14%), PHP 76,669 to PHP 131,484 (7%), PHP 131,484 to PHP 219,140 (2%), and above (2%). Lastly, respondents who owned a vehicle (48.50%) were somewhat equal to the number of respondents who did not own a vehicle (51.50%).

Table 3.

Respondent’s demographic profile (n = 400).

4.2. Data and Model Fit Test

The data fit test employed three (3) factors to both order constructs: Cronbach’s, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE). Cronbach’s α is used to determine the questionnaire’s internal consistency, which also addresses whether the latent variable indicators show convergent validity and reliability [92]. By convention, the cutoff ranges are ≥0.80 (good), ≥0.70 (acceptable), and ≥0.60 (exploratory purposes). Composite reliability is a test of convergent among researchers in PLS-based research [92] with acceptable ranges from ≥0.60 for exploratory purposes [94], ≥0.70 for adequate model’s confirmatory purposes [95], and ≥0.80 for confirmatory research [96]. This research used 0.70 as the basis as various studies that have utilized SEM indicate this as the acceptable range for Cronbach’s α and CR. Convergent and divergent validity can be tested using the AVE [92] since it represents the mean communality of each hidden factor. In a suitable model, AVE should be 0.50 [97], with variables explaining the variance of their respective indicators. Hair et al. [84] proposed that the outside loading values be 0.70 to calculate indication reliability. Table 4 and Table 5 display the data fit results of the lower-order and higher-order constructs.

Table 4.

Measurement model, item loadings, construct reliability, and convergent validity of lower-order constructs.

Table 5.

Measurement model, construct reliability, and convergent validity of higher-order constructs.

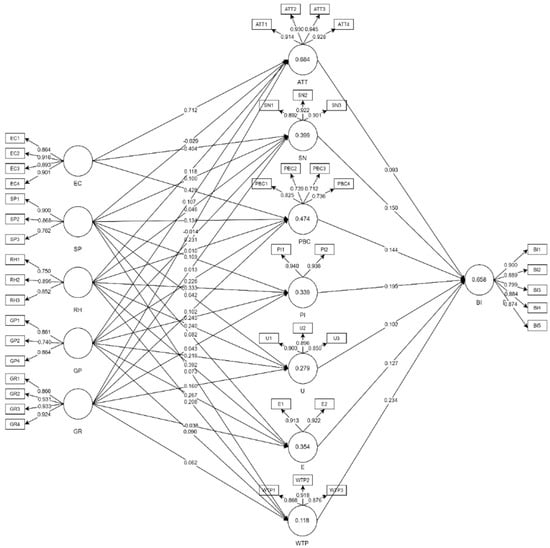

Cronbach’s, CR, and AVE values for lower-order constructs range from 0.754 to 0.947, 0.806 to 0.948, and 0.569 to 0.880, respectively, whereas for higher-order constructs, the values were 0.754 and 0.860, 0.783 and 0.863, and 0.575 and 0.781, respectively. All measures are trustworthy and legitimate based on these values. Because of the unsatisfactory outer loadings exhibited in Figure 2, three (3) of the lower-order structures, namely SP4, RH4, and GP3, were eliminated. The remaining components, with values ranging from 0.712 to 0.945, were deemed adequate [95].

Figure 2.

First stage of disjoint two-stage approach measurement model.

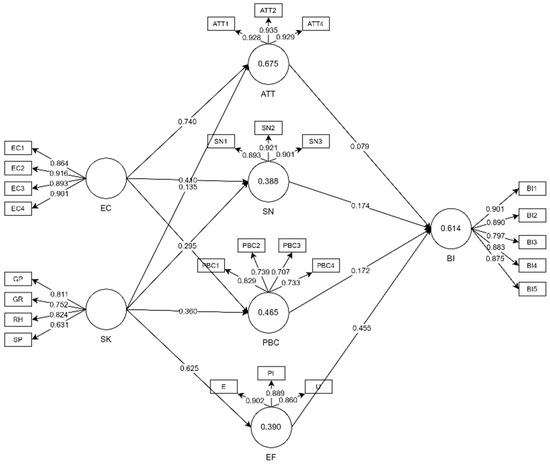

The discriminant validity was evaluated utilizing the Fornell–Larcker Criterion (FLC) and the Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) [98]. It is a conservative strategy for testing the correlation between each construct’s latent variables. The diagonal results presented in Table 6 for lower-order constructs show higher values compared to their respective horizontal values. Garson [92] indicated that there is discriminant validity if figures within columns are higher than numbers below it. Moreover, HTMT was included to further test discriminant validity. Following the suggestion of Henseler et al. [95] that if the HTMT value is below 0.90, there is an established discriminant validity between constructs, the findings of HTMT for lower-order constructs with values less than 0.900 are shown in Table 7, indicating that the constructions are approved. The HTMT and FLC values of higher-order constructs were also evaluated in the second stage of the measurement model shown in Figure 3 and found within the acceptable ranges presented in Table 8 and Table 9, whereas WTP was removed due to high EF higher-order construct HTMT values. Other factors in the tables were not considered as these were already evaluated in the first stage lower-order construct model.

Table 6.

Fornell–Larcker criterion of lower-order constructs.

Table 7.

Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) of lower-order constructs.

Figure 3.

Second stage of disjoint two-stage approach measurement model.

Table 8.

Fornell–Larcker criterion of higher-order constructs.

Table 9.

Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) of higher-order constructs.

The multicollinearity test with variance inflation factor was also analyzed since it can inflate standard errors, make essential tests of independent variables unreliable, and prevent assessing the relative importance of one independent variable to another [92]. The appropriate VIF, according to Ringle et al. [94], should be 0.50. Presented in Table 10 are the results of VIF showing values less than 0.50, whereas ATT3 was removed due to high VIF value, while other factors signify that no further multicollinearity exists among the indicators.

Table 10.

Collinearity statistics (VIF).

Table 11 depicts the outcome of the model fit. It is acknowledged by Hair et al. [84] that the requirement for each indicator must entail that SRMR is less than 0.08 and NFI should be higher than or equal to 0.90. However, the current research’s fitness is rather acceptable but not optimal with SRMR values of 0.074 with the saturated model and 0.143 with the estimated model where both are close to the acceptable values of 0.08 [99] to 0.10 [98]. The NFI values were 0.839 and 0.800, respectively, for the saturated and estimated models, which are slightly lower than 0.90. However, the result is still within an acceptable range, which is greater than 0.50 and closer to 1.0, a number deemed an acceptable fit as demonstrated by the investigations of Zainab et al. [100] and Arham et al. [101].

Table 11.

Model Fit Test.

4.3. Structural Model Assessment

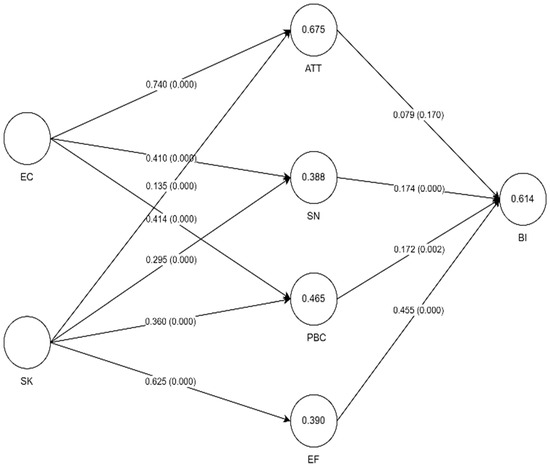

The first analysis validated R-squared values of all endogenous variables shown in Figure 4, while Table 12 shows the model’s structural path analysis.

Figure 4.

Model assessment and R2 values.

Table 12.

Structural path analysis: direct, indirect, and total effects.

The R2 reflects the variation explained by endogenous constructs and thus the explanatory strength of a model [102]. The R2 number spans from 0 to 1, with larger values indicating better explanatory power. Values between 0.51 and 0.75, 0.50 and 0.26, and 0.25 and 0.02 are considered substantial, moderate, and weak explanatory powers, respectively [85]. Using this guideline, the model’s endogenous variables were found to be moderate to substantial with the given values of 0.675 (ATT), 0.388 (SN), 0.465 (PBC), 0.390 (EF), and 0.614 (BI).

Ten (10) of eleven (11) hypotheses were validated for acceptance because their p-values were less than the acceptance standard of 0.05 [95]. The PEPB construct of environmental concern has significant positive relationships with ATT (β = 0.740, t = 17.335, p = 0.000), SN (β = 0.410, t = 7.878, p = 0.000), and PBC (β = 0.414, t = 8.266, p = 0.000). Thus, hypotheses H1 to H3 were accepted. Attitude was found to have an insignificant positive relationship with behavior intention (β = 0.079, t = 1.372, p = 0.170); hence, H4 was rejected. Moreover, SN (β = 0.174, t = 3.638, p = 0.000) and PBC (β = 0.172, t = 3.102, p = 0.002) demonstrated significant relationships with behavior intention; thus, H5 and H6 were accepted. The results also indicated that sustainable knowledge has a significant positive relationship with ATT (β = 0.135, t = 3.662, p = 0.000), SN (β = 0.295, t = 6.377, p = 0.000), PBC (β = 0.360, t = 7.492, p = 0.100), and economic factors (β = 0.625, t = 14.999, p = 0.100). Thus, hypotheses H7, H8, H9, and H10 were accepted. Lastly, it was found that economic factors have a significant positive relationship with behavior intention (β = 0.174, t = 3.638, p = 0.100). Thus, hypothesis H11 was accepted. The validation of the hypotheses is summarized in Table 13.

Table 13.

Hypothesis validation.

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion of Findings

The result of this research model assesses customer’s behavior intention in choosing a petroleum station to purchase goods and services and finds strong positive connections in the PEPB latent variables, extended sustainable knowledge, and economic factor variable.

The study’s first intriguing finding is a highly positive association between environmental concern and TPB variables. EC has a high and significant positive relationship with ATT (β = 0.0740, t = 17.335, p = 0.000), SN (β = 0.410, t = 7.878, p = 0.000), and PBC (β = 0.414, t = 8.266, p = 0.000). It also has a significant and positive indirect effect on BI (β = 0.201, t = 4.153, p = 0.000). Filipino customers place high value on the environment’s current condition and towards the future and feel that petrol station owners should participate in conserving the environment. Furthermore, given the rising emissions across the world, Filipinos are becoming more consistent with their interpretation of pro-environmental concerns and their importance. This finding is supported by studies that show that customers act pro-environmentally when exposed to widespread environmental concerns [103] that significantly influence behavior intention.

The study’s second intriguing finding is that attitude does not always and directly affect behavior intention. This was seen in correlation values of ATT to BI (β = 0.079, t = 1.372, p = 0.170). We found a contrast to previous research, such as that conducted by Suki [104], which found that strong customers’ attitudes toward green products are associated with higher purchase intentions and that there is a positive relationship between attitude and buy intention [105]. Moreover, just because customers have knowledge of what sustainable solutions can do to the environment, this does not necessarily translate into intention. However, in this regard, we can support this finding since attitude is only the extent to which a person will evaluate a behavior favorably or not [20].

The study’s third finding is a strong positive association between PBC and BI. PBC was found to have a beneficial effect on behavior intention (β = 0.172, t = 3.102, p = 0.002). Customers express acceptance of petrol stations adopting sustainable solutions to address environmental concerns. They feel that society can improve when petrol stations adapt to sustainability measures. This finding is confirmed by the findings of Zhang et al. [27], who discovered that PBC influences the intention to adopt renewables.

The fourth discovery is a substantial positive connection between SN and BI (β = 0.174, t = 3.638, p = 0.000). Household members strongly influence customers’ decision to purchase goods and services from a petrol station adopting sustainable practices since they live together and mostly travel together. Colleagues and peers also express influence on customers especially those who are carpooling and looking for picturesque places to spend time. The idea of going to this type of petrol station with a lot of greenery brings curiosity to customers regarding how it looks and what it feels like. SN is a major predictor of behavior intention, according to several studies [25,26].

The fifth study finding indicates that EF has a strong positive connection with BI (β = 0.455, t = 6.040, p = 0.000). Customers perceived that petrol stations adopting sustainable practices contribute to economic development through incentive programs and job generation. They also believe that these factors can improve environmental education promoting pro-environmental behavior. These were evident in the studies of Park [56], Skumatz [53], Fan et al. [60], and Ones et al. [61].

The study’s main finding is a high positive link between sustainable knowledge and TPB variables, i.e., ATT (β = 0.135, t = 3.622, p = 0.000), SN (β = 0.295, t = 6.377, p = 0.000), PBC (β = 0.360, t = 7.492, p = 0.000), as well as EF (β = 0.625, t = 14.999, p = 0.000), and an indirect strong positive correlation to BI (β = 0.408, t = 10.246, p = 0.000). This shows that when customers have the right knowledge of what sustainability practices are and what these can contribute to ease environmental concerns, they lean towards positive perception and acceptance of petrol stations adopting said measures. When these are considered, customers are convinced to purchase goods and services in these petrol stations and recommend and continue purchasing and using their services to meet their demands whether for personal or environmental reasons. This is supported by different studies [40,48].

Finally, the R2 value of behavior intention was discovered to be 0.614, implying that ATT, SN, PBC, and economic factors explain 61.4% of the variance in behavior intention. This value is within the range of similar studies that investigate behavior intention focusing on purchase intentions, such as the studies of Yuniaristanto et al. [106] with an R2 value of 0.477 and Zia et al. [9] with an R2 value of 0.653. Thus, the model’s value can be considered satisfactory since it is the first to use economic factors to explain purchase intention combined with the TPB factors. The independent variables explaining the intention outcomes in the mentioned research are limited with perceived value, social influence, quality, perceived risk, price, and incentives only. However, the R2 value should still be judged relative to studies that investigate the same dependent variable.

Overall, the study found that various factors impact customers in the Philippines, leading to their intention to buy goods and services from a fuel station that practices sustainability. These factors include environmental concern, attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, sustainable knowledge, and economic factors. Customers also consider that the key factor is the potential of the petrol stations to provide economic advantages, not limited to customers, but to the general population, which provides benefits in a societal context. Customers are influenced to use products or services that generate impact economically. In turn, petrol station owners who engage in these practices are recognized with increased market share, customer base, and maintained customer loyalty.

5.2. Implication of the Study

5.2.1. Theoretical Implication

The research utilized and extended the existing Pro-Environmental Theory of Planned Behavior (PEPB) developed by Persada [16] with two independent variables: sustainability knowledge and economic factors, displaying a new exploratory model for investigation. As an illustration of an extended standard notion, the extended model depicts the link between higher and lower-order components. This method defines sustainable knowledge as being measured by different known sustainable practices, such as solar PV, rainwater harvesting, green roofing, and green products, applicable to not just the Philippines, but also to other countries with economic factors measured by urbanization, incentives, employment, and willingness to pay. Further, the study differentiates from other similar extended models that utilized PEPB, including [70,80,87,107,108], which concluded that, aside from the environmental effects, customers are also concerned about the economic benefits of pro-environmental behavior, which also leads them to either practice intent behavior, choose a service, or buy goods. It also promotes customers’ behavior intention to determine not only their intention to purchase goods and services from a petrol station adopting sustainability practices but also their perception towards these type of petrol stations. The study highlights economic factors that are key areas to customers’ behavior intention. Utilizing this extended model gives us a potential area for thorough research on how sustainability affects behavior intention in this type of business sector. Finally, the conclusions of this study are significant environmental concerns and a petrol station.

5.2.2. Practical Implication

The result of this research model discerns several factors influencing customers’ intention to purchase goods and services from a petrol station adopting sustainability practices. A few recommendations are hereby presented, such as the government may impose policies to business owners to implement a green station concept prior to building a petrol station to address environmental concerns in return for possible incentives, such as tax, fees, permits, and licenses discount and cater to them a possible positive high return on economic share and customer base. The findings of the study will bring knowledge to business owners that a pro-environmental attitude impacts customers’ behavior. The influence of economic factors on the intent to purchase indicates that business owners should focus on continuously generating economic and societal advantages, such as providing incentives to customers and generating green jobs through adopting sustainability practices. Hence, business owners should focus on how they can also help the public become aware of sustainable practices and how they can help address environmental concerns. Moreover, behavior intention states that customers will continue to purchase goods and services with businesses engaged in sustainability practices even without environmental problems. Ensuring that the business implements these practices provides a window for investors and customers since the growth and income potential can be promising.

5.3. Limitations of the Study

Despite its encouraging findings, the current study has its limitations. First, the research is exploratory in nature; hence, the data-collection process was challenging and there is no in-depth pre-existing knowledge to make as a baseline. Second, the location of the respondents was the NCR and Region 4A. More widely distributed respondents from other regions might have affected the factor weights, coming up with a different result. Future studies may investigate Filipino customers’ intentions to purchase goods and services from a petrol station in area-specific settings and compare it to other areas, such as provincial areas compared to the metro. Third, the number of respondents was limited to 400 only. A larger sample size may result in more accurate results. Fourth, the survey was conducted online, limiting the respondents favorably to those who are usually online. Thus, similar future research should consider physical survey distribution within the vicinity of petrol stations or to people who frequently attend petrol stations. Finally, the current study only evaluated the most well-known sustainability practices and economic factors, which are also empirically decided. Further studies can integrate factors not limited to other sustainability practices or economic factors, but other theories not cited, such as CSR, brand recognition, loyalty, and technology acceptance, may be conducted. Although the present research considered avoiding bias of cross-culture using a specific country, the opportunity to compare with the countries characterized by multigroup can be recommended. This can further improve analysis and produce a variety of practical decisions, if used by a global company.

6. Conclusions

The current study explores the intention of Filipino customers to purchase goods and services from a petrol station adopting sustainability practices using an extended PEPB model. Significant positive relationships were found in the PEPB components, extended variables sustainable initiative knowledge, and economic factors. The findings revealed that economic concern, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, economic factors, and sustainable knowledge significantly influence the customers’ intention to purchase goods and services from a petrol station adopting sustainability practices, while attitude was found to have no direct significant impact on customers’ intention. The customers’ perception of environmental concerns and their knowledge of sustainability also affected their intention to purchase goods and services since both indirectly affect the customers’ intention to purchase. Business owners are encouraged to publicly participate in addressing environmental concerns and the implementation of sustainability practices to gain more customers and maintain loyalty. The government should also impose stronger policies for businesses such as petrol stations to address environmental problems and must continuously monitor its implementation. They should continue to practice high regard for the environment through continuous development of sustainability practices in petrol stations, even when environmental problems are no longer present.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A.A.R. and Y.T.P.; methodology, R.A.A.R. and Y.T.P.; software, R.A.A.R. and Y.T.P.; validation, M.M.L.C., R.N., M.J.J.G. and I.D.A.; formal analysis, R.A.A.R. and Y.T.P.; investigation, R.A.A.R. and Y.T.P.; writing—original draft preparation, R.A.A.R. and Y.T.P.; writing—review and editing, M.M.L.C., R.N., M.J.J.G. and I.D.A.; supervision, Y.T.P.; funding acquisition, M.M.L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Mapúa University Directed Research for Innovation and Value Enhancement (DRIVE).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by Mapua University Research Ethics Committees (FM-RC-23-34).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study (FM-RC-23-34).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The researchers would like to extend their deepest gratitude to the respondents of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Saviano, M.; Barile, S.; Spohrer, J.C.; Caputo, F. A service research contribution to the global challenge of sustainability. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2017, 27, 951–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, W.; Cocklin, C. Conceptualizing a “Sustainability business model”. Organ. Environ. 2008, 21, 103–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Pan, S.L.; Zuo, M. How to balance sustainability and profitability in technology organizations: An ambidextrous perspective, Engineering Management. IEEE Trans. 2013, 60, 366–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M.U.; Musa, I.J.; Jeb, D.N. GIS-Based Analysis of the Location of Filling Stations in Metropolitan Kano against the Physical Planning Standards. Am. J. Eng. Res. (AJER) 2014, 3, 147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S.N.B.; Juhdi, N.; Awadz, A.S. Examination of environmental knowledge and perceived pro-environmental behavior among students of University Tun Abdul Razak, Malaysia. Int. J. Multidiscip. Thought 2010, 1, 328–342. [Google Scholar]

- Cabalu, H.; Koshy, P.; Corong, E.; Rodriguez, U.P.E.; Endriga, B.A. Modelling the impact of energy policies on the Philippine economy: Carbon tax, energy efficiency, and changes in the energy mix. Econ. Anal. Policy 2015, 48, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommasetti, A.; Singer, P.; Troisi, O.; Maione, G. Extended theory of planned behavior (ETPB): Investigating customers’ perception of restaurants’ sustainability by testing a structural equation model. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalhoro, M.; Au Yong, H.N.; Ramendran Spr, C. Understanding the factors affecting pro-environment behavior for city rail transport usage: Territories’ empirical evidence—Malaysia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, A.; Alzahrani, M.; Alomari, A.; AlGhamdi, F. Investigating the drivers of sustainable consumption and their impact on online purchase intentions for Agricultural Products. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwagbara, U.; Brown, C. Communication and conflict management: Towards the rhetoric of integrative communication for sustainability in Nigeria’s oil and gas industry. Econ. Insights Trends Chall. 2014, 66, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Okeke, A. Towards sustainability in the global oil and gas industry: Identifying where the emphasis lies. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2021, 12, 100145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mshelia, A.M.; Abdullahi, J.; Dawha, E.D. Environmental Effects of Petrol Stations at Close Proximities to Residential Buildings in Maiduguri and Jere, Borno State, Nigeria. IOSR J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2015, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Manneh, M.; Kozhevnikov, M.; Chazova, T. Determinants of consumer preference for petrol consumption: The case of petrol retail in the Gambia. Int. J. Energy Prod. Manag. 2020, 5, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, K.T.; Khoo, K.L.; Naim, M.N. The influence of consumers’ patronage behavior towards petrol stations: A multigroup analysis using PLS-SEM. J. Appl. Struct. Equ. Model. 2022, 6, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raed, A.A.; Ahmed, A.; Abdelhamid, A. Biomimicry approach design of petrol stations with integrating renewable energy in the UAE. In WIT Transactions on the Built Environment; WIT Press: Southampton, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persada, S. Pro Environmental Planned Behavior Model to Explore the Citizens’ Participation Intention in Environmental Impact Assessment: An Evidence Case in Indonesia; National Taiwan University of Science & Technology: Taipei, Taiwan, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Yoon, H.J. Hotel customers’ environmentally responsible behavioral intention: Impact of key constructs on decision in green consumerism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 45, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman, A.H.; Harun, A.; Hussein, Z. The Influence of Environmental Knowledge and Concern on Green Purchase Intention the Role of Attitude ad a Mediating Variable British. J. Arts Soc. Sci. 2012, 7, 145–167. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, I.; Liu, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhang, H.; Xu, W. Factors influencing the behavioural intention towards Full Electric Vehicles: An empirical study in Macau. Sustainability 2015, 7, 12564–12585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Chaiken, S. The Psychology of Attitudes; Wadsworth Cengage Learning: Belmont, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Chyong, H.T.; Phang, G.; Hasan, H.; Buncha, M.R. Going green: A study of consumers’ willingness to pay for green products in Kota Kinabalu. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2006, 7, 40–54. [Google Scholar]

- Karaiskos, D.; Tzavellas, E.; Balta, G.; Paparrigopoulos, T. P02-232—Social Network Addiction: A new clinical disorder? Eur. Psychiatry 2010, 25, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.; Chung, N.; Leue, M.C. The determinants of recommendations to use augmented reality technologies: The case of a Korean theme park. Tour. Manag. 2015, 49, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Nguyen, H.V.; Nguyen, P.T.; Tran, V.T.; Nguyen, H.N.; Nguyen, T.M.; Cao, T.K.; Nguyen, T.H. Some key factors affecting consumers’ intentions to purchase Functional Foods: A Case Study of functional yogurts in Vietnam. Foods 2020, 9, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.J.; Park, J.W. Investigating factors influencing the behavioral intention of online duty-free shop users. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, S.; Qu, X.; Tao, D. Predicting errors, violations, and safety participation behavior at nuclear power plants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 17, 5613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, L.; Wang, S. Antecedents of consumers’ intention to purchase energy-efficient appliances: An empirical study based on the technology acceptance model and theory of planned behavior. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamman, M.; Ogunbado, A.F.; Abu-Bakr, A.S. Factors influencing customer’s behavioral intention to adopt Islamic banking in Northern Nigeria: A proposed framework. J. Econ. Financ. 2016, 7, 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- Park, E.; Ohm, J.Y. Factors influencing the public intention to use renewable energy technologies in South Korea: Effects of the fukushima nuclear accident. Energy Policy 2014, 65, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Liu, H.; Feldman, M.W. How does trust affect acceptance of a nuclear power plant (NPP): A survey among people living with Qinshan NPP in China. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, G.H.; Jung, W.J.; Kim, T.H.; Lee, S.Y.T. The cognitive and economic value of a nuclear power plant in Korea. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2017, 49, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, V.; Cavallo, C.; Catellani, P.; Del Giudice, T.; Cicia, G. Why do consumers intend to purchase natural food? integrating theory of planned behavior, value-belief-norm theory, and Trust. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Ploeger, A. Explaining consumers’ intentions towards purchasing Green Food in Qingdao, China: The Amendment and extension of the theory of planned behavior. Appetite 2019, 133, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabaia, M.K.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Sayed, E.T.; Elsaid, K.; Chae, K.J.; Wilberforce, T.; Olabi, A.G. Environmental impacts of solar energy systems: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 754, 141989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanveer, A.; Zeng, S.; Irfan, M.; Peng, R. Do perceived risk, perception of self-efficacy, and openness to technology matter for solar PV adoption? an application of the extended theory of planned behavior. Energies 2021, 14, 5008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaslip, E.; Costello, G.J.; Lohan, J. Assessing good-practice frameworks for the development of Sustainable Energy Communities in Europe: Lessons from Denmark and Ireland. J. Sustain. Dev. Energy Water Environ. Syst. 2016, 4, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocker, T.F.; Qin, D.; Plattner, G.K.; Tignor, M.M.B.; Allen, S.K.; Boschung, J.; Nauels, A.; Xia, Y.; Bex, V.; Midgley, P.M. IPCC, 2013: Climate Change The Physical Science Basis; Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulla, F.A.; Al-Shareef, A.W. Roof rainwater harvesting systems for household water supply in Jordan. Desalination 2009, 243, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian Amos, C.; Rahman, A.; Mwangi Gathenya, J. Economic analysis and feasibility of rainwater harvesting systems in urban and peri-urban environments: A review of the global situation with a special focus on Australia and Kenya. Water 2016, 8, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, J.; Jensen, M.; Pomeroy, C.A.; Burian, S.J. Water Supply and stormwater management benefits of residential rainwater harvesting in U.S. cities. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2012, 49, 810–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrill, S.; Farreny, R.; Gasol, C.M.; Gabarrell, X.; Viñolas, B.; Josa, A.; Rieradevall, J. Environmental analysis of rainwater harvesting infrastructures in diffuse and compact urban models of Mediterranean climate. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2012, 17, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T.; Rost, Z. Towards true product sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakastos, E.S.; Nan, L.M.; Bacali, L.; Ciobanu, G.; Ciobanu, A.M.; Cioca, L.I. Consumer satisfaction towards green products: Empirical insights from Romania. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, I.; Hyder, Z.; Imran, M.; Shafiq, K. Greenwash and green purchase behavior: An environmentally sustainable perspective. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 13113–13134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witek, L. Barriers to green products purchase–from polish consumer perspective. In Innovation Management, Entrepreneurship and Sustainability (IMES 2017); Vysoká škola ekonomická v Praze: Prague, Czech Republic, 2017; pp. 1119–1128. [Google Scholar]

- Ottman, J. Sometimes Consumers Will Pay More to Go Green. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 1992, 16, 12–120. [Google Scholar]

- Johri, L.M.; Sahasakmontri, K. Green marketing of cosmetics and toiletries in Thailand. J. Consum. Mark. 1998, 15, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.M. The Potential Carbon Offset Represented by a Green Roof. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Köhler, M.; Schmidt, M.; Grimme, F.W.; Laar, M.; Gusmão, F. Urban water retention by greened roofs in temperate and tropical climate. Technol. Resour. Manag. Dev. 2001, 2, 151–162. [Google Scholar]

- Shafique, M.; Kim, R.; Rafiq, M. Green roof benefits, opportunities, and Challenges—A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 90, 757–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberndorfer, E.; Lundholm, J.; Bass, B.; Coffman, R.R.; Doshi, H.; Dunnett, N.; Gaffin, S.; Köhler, M.; Liu, K.K.; Rowe, B. Green roofs as urban ecosystems: Ecological structures, functions, and services. BioScience 2007, 57, 823–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skumatz, L.A. Pay as you throw in the US: Implementation, impacts, and experience. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 2778–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seacat, J.D.; Boileau, N. Demographic and community-level predictors of recycling behavior: A statewide assessment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 56, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timlett, R.E.; Williams, I.D. Public participation and recycling performance in England: A comparison of tools for behaviour change. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2008, 52, 622–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S. Factors influencing the recycling rate under the volume-based waste fee system in South Korea. Waste Manag. 2018, 74, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Xie, R.; Fang, J.; Liu, Y. The effects of urban agglomeration economies on carbon emissions: Evidence from Chinese cities. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1096–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Molina, M.A.; Fernández-Sáinz, A.; Izagirre-Olaizola, J. Environmental knowledge and other variables affecting pro-environmental behaviour: Comparison of university students from emerging and advanced countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 61, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, A.; Franzen, A. TheWealth of Nations and Environmental Concern. Environ. Behav. 1999, 31, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Yang, W.; Han, T. Impact of Basic Public Service Level on Pro- Environmental Behavior in China. Int. Sociol. 2018, 33, 738–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ones, D.S.; Wiernik, B.M.; Dilchert, S.; Klein, R. Pro-environmental behavior. Int. Encycl. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Pandey, N. The determinants of green packaging that influence buyers’ willingness to pay a price premium. Australas. Mark. J. 2018, 26, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinnen, G.; Hille, S.L.; Wittmer, A. Willingness to pay for green products in air travel: Ready for take-off? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, M.; Mayer, K.J. A profile of travelers who are willing to stay in environmentally friendly hotel. Hosp. Rev. 2013, 30, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Aravena, C.; Hutchinson, W.G.; Longo, A. Environmental pricing of externalities from different sources of electricity generation in Chile. Energy Econ. 2012, 34, 1214–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelissen, J. Explaining popular support for environmental protection. Environ. Behav. 2007, 39, 392–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Method Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- PSA. Age and Sex Distribution in the Philippine Population (2020 Census of Population and Housing). Available online: https://www.psa.gov.ph/content/age-and-sex-distribution-philippine-population-2020-census-population-and-housing (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Fuji, S. Environmental Concern, Attitude toward Frugality, and Ease of Behavior as Determinants of Pro-Environmental Behavior Intentions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.C.; Nadlifatin, R.; Amna, A.; Persada, S.; Razif, M. Investigating citizen behavior intention on mandatory and voluntary Pro-Environmental programs through a pro-environmental planned behavior model. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persada, S.F.; Lin, S.C.; Nadlifatin, R.; Razif, M. Investigating the citizens’ intention level in environmental impact assessment participation through an extended theory of planned behavior model. Glob. NEST J. 2015, 17, 847–857. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, S. Understanding consumers’ intentions to purchase green products in the social media marketing context. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2019, 32, 860–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos, K.J.; Moersidik, S.S.; Soesilo, T.E. Extended theory of planned behavior on utilizing domestic rainwater harvesting in Bekasi, West Java, Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 716, 012054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeeshani, M.; Ramachandra, T.; Gunatilake, S.; Zainudeen, N. Carbon footprint of Green Roofing: A case study from Sri Lankan Construction Industry. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mughrabi, N.; Hussein, M.F.; Alhyari, N.H. Rooftop garden in Amman residential buildings–sustainability and utilization. In Proceedings of the 1st International Congress on Engineering Technologies, Irbid, Jordan, 16–18 June 2020; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 196–205. [Google Scholar]

- Lili, D.; Ying, Y.; Qiuhui, H.; Mengxi, L. Residents’ acceptance of using desalinated water in China based on the theory of planned behaviour (TPB). Mar. Policy 2021, 123, 104293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Chao, W.H. Habitual or reasoned? using the theory of planned behavior, technology acceptance model, and habit to examine switching intentions toward public transit. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2011, 14, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, A.K.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Salazar, J.M.; Erfe, J.J.; Abella, A.A.; Young, M.N.; Chuenyindee, T.; Nadlifatin, R.; Ngurah Perwira Redi, A.A. Investigating the acceptance of the reopening Bataan Nuclear Power Plant: Integrating Protection Motivation Theory and extended theory of planned behavior. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2021, 54, 1115–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.T.; Sheu, C. Application of the theory of planned behavior to Green Hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, J.D.; Redi, A.A.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Persada, S.F.; Ong, A.K.; Young, M.N.; Nadlifatin, R. Choosing a package carrier during COVID-19 pandemic: An integration of pro-environmental planned behavior (PEPB) theory and Service Quality (SERVQUAL). J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 346, 131123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicente, P.; Marques, C.; Reis, E. Willingness to pay for environmental quality: The effects of pro-environmental behavior, perceived behavior control, environmental activism, and educational level. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 215824402110252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soorani, F.; Ahmadvand, M. Determinants of consumers’ food management behavior: Applying and extending the theory of planned behavior. Waste Manag. 2019, 98, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, S.Y.; Cho, W.S.; Seok, G.A.; Yoo, S.G. Intention to use Sustainable Green Logistics Platforms. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Astrachan, C.B.; Moisescu, O.I.; Radomir, L.; Sarstedt, M.; Vaithilingam, S.; Ringle, C.M. Executing and interpreting applications of PLS-SEM: Updates for family business researchers. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2021, 12, 100392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate Data Analysis: An overview. In International Encyclopedia of Statistical Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 904–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M. Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: A Comparative Evaluation of Composite-based Structural Equation Modeling Methods. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumasing, M.J.J.; Bayola, A.; Bugayong, S.L.; Cantona, K.R. Determining the Factors Affecting Filipinos’ Acceptance of the Use of Renewable Energies: A Pro-Environmental Planned Behavior Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.Y.; Syrgabayeva, D. Mechanism of environmental concern on intention to pay more for renewable energy: Application to a developing country. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2016, 21, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Shen, G.Q. Encouraging the use of urban green space: The mediating role of attitude, perceived usefulness and perceived behavioural control. Habitat Int. 2015, 50, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Mitchell, R.; Gudergan, S.P. Partial least squares structural equation modeling in HRM research. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 1617–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.M.; Klein, K.; Wetzels, M. Hierarchical latent variable models in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using reflective-formative type models. Long Range Plan. 2012, 45, 359–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garson, G.D. Partial Least Squares Regression & Structural Model; Statistical Associates Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly, L.M. Pilot Studies. Medsurg Nurs. 2008, 17, 411–412. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.M. SmartPLS 3; SmartPLS: Oststeinbek, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Using partial least squares path modeling in advertising research: Basic concepts and recent issues. In Handbook of Research On International Advertising; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Daskalakis, S.; Mantas, J. Evaluating the impact of a service-oriented framework for healthcare interoperability. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2008, 136, 285. [Google Scholar]

- Hock, M.; Ringle, C.M. Local strategic networks in the software industry: An empirical analysis of the value continuum. Int. J. Knowl. Manag. Stud. 2010, 4, 132–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.t.; Bentler, P.M. Fit Indices in Covariance Structure Modeling: Sensitivity to Underparameterized Model Misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainab, A.M.; Kiran, K.; Ramayah, T.; Karim, N.H.A. Modelling drivers of Koha Open Source Library system using partial least squares structural equation modelling. Malays. J. Libr. Inf. Sci. 2019, 24, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arham, A.F.; Amin, L.; Mustapa, M.A.; Mahadi, Z.; Yaacob, M.; Arham, A.F.; Norizan, N.S. “To do, or not to do?”: Determinants of stakeholders’ acceptance on dengue vaccine using PLS-SEM analysis in Malaysia. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G.; Koppius, O.R. Predictive analytics in information systems research. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 553–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesley, S.C.; Lee, M.Y.; Kim, E.Y. The Role of Perceived Consumer Effectiveness and Motivational Attitude on Socially Responsible Purchasing Behavior in South Korea. J. Glob. Mark. 2012, 25, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suki, N.M. Green Awareness Effects on Consumers’ Purchasing Decision: Some Insights From Malaysia. IJAPS 2013, 9, 49–63. [Google Scholar]