Revisiting China’s Urban Transition from the Perspective of Urbanisation: A Critical Review and Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Results

3.1. Emerging Research Topics in the Global Perspective

3.1.1. Socio-Economic Transition and Urban Development

3.1.2. Rural–Urban Population Migration

3.1.3. Cultural Heterogeneity and Urban Planning

3.1.4. Institutional Implementation in Urban Transition

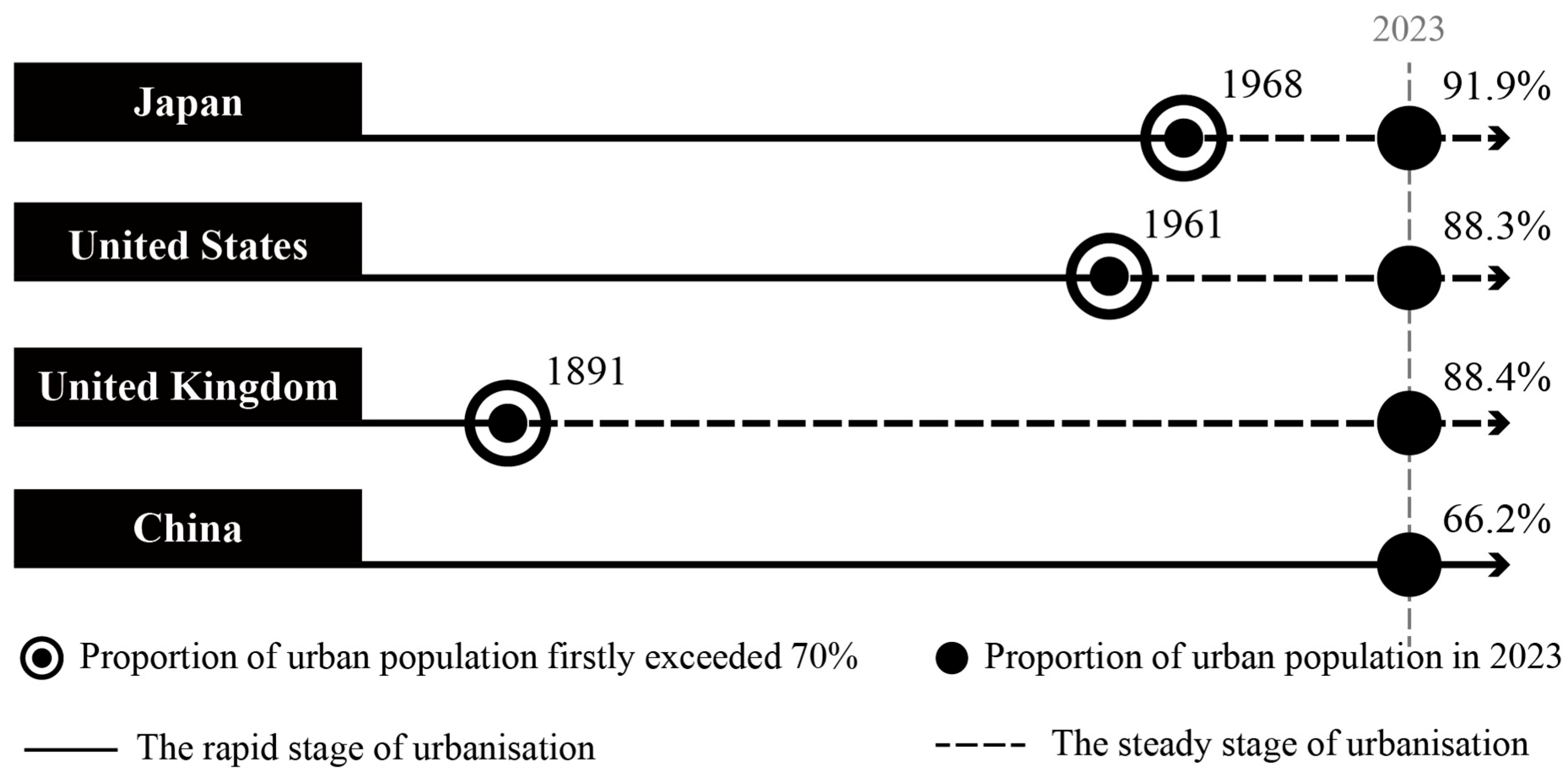

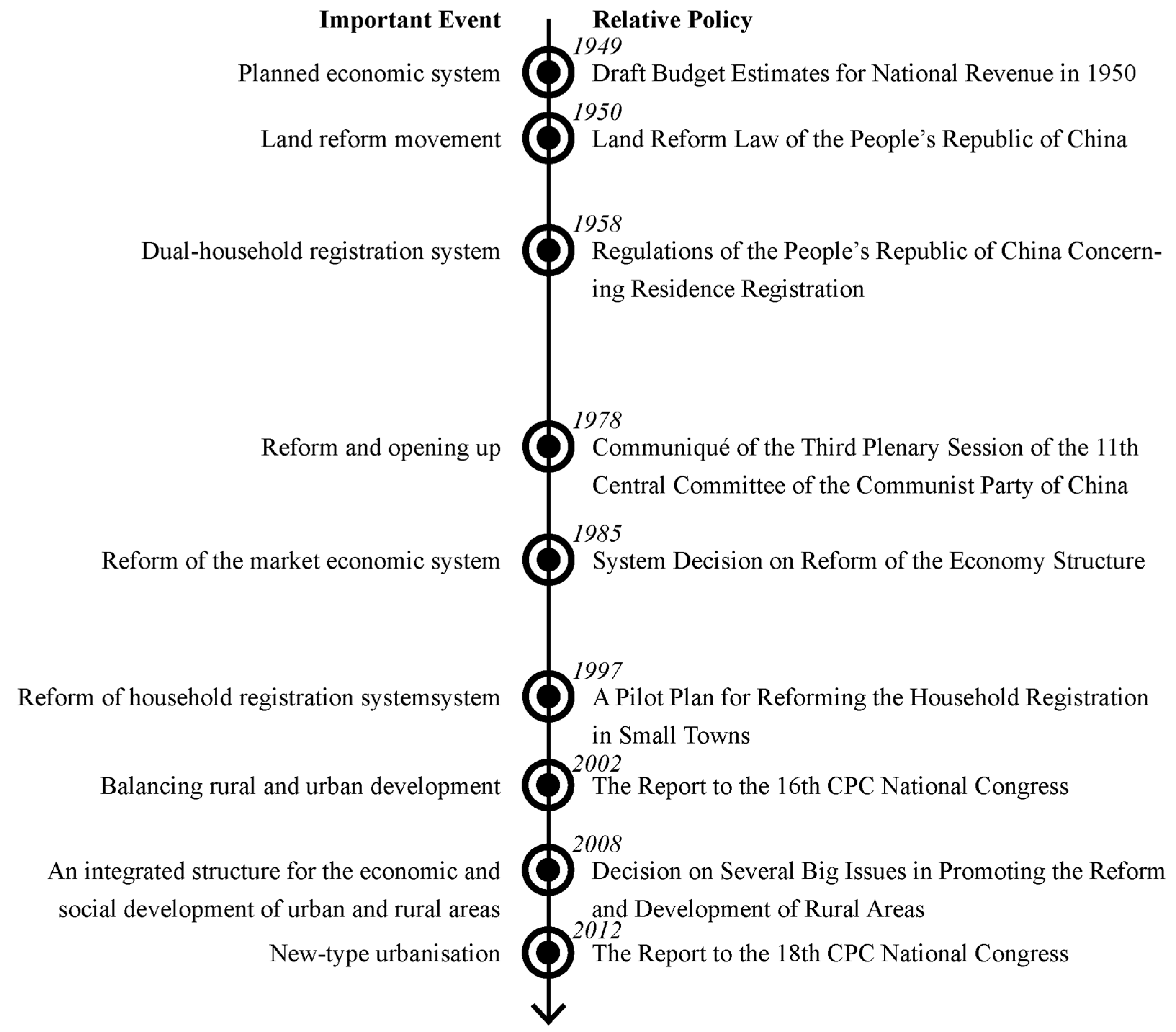

3.2. China’s Urbanisation Process

3.3. Addressing Challenges: China’s Transition to New-Type Urbanisation

3.3.1. Interconnected Dynamics: Population, Land, and Industry in China’s Urbanisation

3.3.2. Policy Reforms in Population Urbanisation

3.3.3. From Land Expansion to Sustainable Urban Growth

3.3.4. Catalysing Industrial Transformation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Geels, F. The role of cities in technological transitions: Analytical clarifications and historical examples. In Cities and Low Carbon Transitions; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Gleick, P.H. Global freshwater resources: Soft-path solutions for the 21st century. Science 2003, 302, 1524–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Energy Agency. World Energy Outlook. 2011. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/energy/world-energy-outlook-2011_weo-2011-en (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Gil, N.; Beckman, S. Introduction: Infrastructure meets business: Building new bridges, mending old ones. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2009, 51, 6–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Towards a Green Economy: Pathways to Sustainable Development and Poverty Eradication. Available online:www.unep.org (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- International Labour Organisation. COVID-19 and the World of Work: Country Policy Responses; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Q.; Qijiao, S.; Xiaofan, Z.; Shiyong, Q.; Lindsay, T. China’s New Urbanisation Opportunity: A Vision for the 14th Five-Year Plan; Coalition for Urban Transitions: London, UK; Washington, DC, USA,, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, W.; Cheshmehzangi, A. Eco-Development in China: Cities, Communities and Buildings; Springer: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, P.; Zhang, M. The impact of urbanisation on energy consumption: A 30-year review in China. Urban Clim. 2018, 24, 940–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.T.; Chen, T.; Cai, J.M.; Liu, S.G. Regional concentration and region-based urban transition: China’s mega-urban region formation in the 1990S. Urban Geogr. 2009, 30, 312–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevens, F.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Gorissen, L.; Loorbach, D. Urban Transition Labs: Co-creating transformative action for sustainable cities. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 50, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xia, Y. The Development Road of Low-carbon Economy under the New Urbanization Background. J. Soc. Sci. Hunan Norm. Univ. 2012, 3, 84–87. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Wang, T. Historical Stages of China’s Urbanization Since 1949. Urban Plan. Forum 2012, 204, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- McGranahan, G.; Satterthwaite, D. Urbanisation Concepts and Trends; IIED Working Paper: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1-78431-063-9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, L. An Overview of China s Urbanization Policies over the Years and Forecast of Future Urbanization Levels. J. Yunnan Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2021, 15, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China National Statistical Bureau. Bulletin of the Seventh National Census. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/guoqing/2021-05/13/content_5606149.htm (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- World Bank. Urban Population (% of Total Population)-China. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL.IN.ZS?locations=CN (accessed on 24 November 2021).

- Douglass, M. Resilient Urbanism in the Anthropocene–The Rise of Progressive City Regions in Asia’s Urban Transition. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Resilience in Asian Urbanism University of Washington Center for Asian Urbanisms Colledge of Built Environment, Jackson School of International Studies, Seattle, WA, USA, 28–30 March 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hamnett, C. Is Chinese urbanisation unique? Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Liang, S.; Carlton, E.J.; Jiang, Q.; Wu, J.; Wang, L.; Remais, J.V. Urbanisation and health in China. Lancet 2012, 379, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F. Emerging Chinese Cities: Implications for Global Urban Studies. Prof. Geogr. 2015, 68, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Ye, C.; Liu, Y. From the arrival cities to affordable cities in China: Seeing through the practices of rural migrants’ participation in Guangzhou’s urban village regeneration. Habitat Int. 2023, 138, 102872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, R.; Ren, J. The City in China: New Perspectives on Contemporary Urbanism; Policy Press: Bristol, England, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Watson, M. Guidance on Conducting a Systematic Literature Review. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2019, 39, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petticrew, M.; Roberts, H. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jilcha Sileyew, K. Research Design and Methodology. In Cyberspace; Abu-Taieh, E., El Mouatasim, A., Al Hadid, I.H., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J.; Watson, R.T. Analyzing the past to prepare for the future: Writing a literature review. MIS Q. 2002, xiii–xxiii. [Google Scholar]

- Vourvachis, P.; Woodward, T. Content analysis in social and environmental reporting research: Trends and challenges. J. Appl. Account. Res. 2015, 16, 166–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Cheshmehzangi, A.; Mangi, E.; Heath, T. Implementations of China’s New-Type Urbanisation: A Comparative Analysis between Targets and Practices of Key Elements’ Policies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leducq, D.; Scarwell, H.J. The new Hanoi: Opportunities and challenges for future urban development. Cities 2018, 72, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.L. The State and Marginality: Reflections on Urban Outcasts from China’s Urban Transition. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2009, 33, 841–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.M.; Zhu, M.W.; Xiao, Y. Urbanization for rural development: Spatial paradigm shifts toward inclusive urban-rural integrated development in China. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 71, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Huang, P. Local governments’ incentives and governing practices in low-carbon transition: A comparative study of solar water heater governance in four Chinese cities. Cities 2020, 96, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Dunford, M. City shrinkage in China: Scalar processes of urban and hukou population losses. Reg. Stud. 2018, 52, 1111–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.W.; Tang, B.S.; Liu, J.L. Village Redevelopment and Desegregation as a Strategy for Metropolitan Development: Some Lessons from Guangzhou City. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2018, 42, 1064–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.P.; Zhang, M.; Qing, Y.X.; Li, Y. Village resettlement and social relations in transition: The case of Suzhou, China. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2019, 41, 269–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.A.; Nielsen, C.P.; Wu, J.R.; Chen, X.H. Examining socio-spatial differentiation under housing reform and its implications for mobility in urban China. Habitat Int. 2022, 119, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.Y.; Zhu, Y. Types and determinants of migrants’ settlement intention in China’s new phase of urbanization: A multi-dimensional perspective. Cities 2022, 124, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.S.; Hao, P.; Feng, J.X. Consumer behavior of rural migrant workers in urban China. Cities 2020, 106, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wu, W.P.; Zhong, W.J.; Zeng, G.; Wang, S. The reshaping of social relations: Resettled rural residents in Zhenjiang, China. Cities 2017, 60, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, L.H.T.; Li, V.J. The role of higher education in China’s inclusive urbanization. Cities 2017, 60, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.N.; Gao, X.L.; Wang, Z.Y.; Gilroy, R.; Wu, H.K. An investigation of non-local-governed urban villages in China from the perspective of the administrative system. Habitat Int. 2018, 74, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, B.J.L.; Okulicz-Kozaryn, A. Dissatisfaction with city life: A new look at some old questions. Cities 2009, 26, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, K.; Nijkamp, P. The evolution of national urban systems in China, Nigeria and India. J. Urban Manag. 2019, 8, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.L.; Zhu, H.; Yuan, Z.J. Contested memory amidst rapid urban transition: The cultural politics of urban regeneration in Guangzhou, China. Cities 2020, 102, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessard, G. The scaling up of the tiny house niche in Quebec-transformations and continuities in the housing regime. J. Environ. Pol. Plan. 2022, 24, 625–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.K.; Wang, Y.P.; Kintrea, K. The (Re)Making of Polycentricity in China’s Planning Discourse: The Case of Tianjin. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2020, 44, 857–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiGregorio, M. Into the land rush: Facing the urban transition in Hanoi’s western suburbs. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2011, 33, 293–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.; Salama, A.; Wiedmann, F.; Aboukalloub, B.; Awwaad, R. Investigating land use dynamics in emerging cities: The case of downtown neighbourhood in Doha. J. Urban Des. 2020, 25, 387–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hin, L.L.; Xin, L. Redevelopment of urban villages in Shenzhen, China—An analysis of power relations and urban coalitions. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yung, E.H.K.; Chan, E.H.W. Comparison of perceived sustainability among different neighbourhoods in transitional China: The case of Chengdu. Habitat Int. 2020, 103, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieminen, J.; Salomaa, A.; Juhola, S. Governing urban sustainability transitions: Urban planning regime and modes of governance. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2021, 64, 559–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Gong, H.; Hu, X. Geography of Sustainability Transitions: A Sympathetic Critique and Research Agenda. Prog. Geogr. 2021, 40, 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Qi, W.; Liu, Z.; Liu, S. The Progress and Prospect of Studies on Urban Transformation. World Reg. Stud. 2016, 26, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, J. Four Theses in the Study of China’s Urbanization. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2006, 30, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Fei, L. Urban Transition and Construction of National Central City: Experience and Direction. Henan Soc. Sci. 2017, 25, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, N. China’s Urbanization. Manag. World 2003, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Zhou, Y. Foreign Urbanization Development Pattern and China’s Urbanization Road; Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China: Beijing, China, 29 September 2005.

- Wu, L. China’s Urbanization from 1978 to 2000. Res. Chin. Econ. Hist. 2002, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, W. On process and development mode of urbanization in China. Manag. Geol. Sci. Technol. 2003, 20, 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, D. Viewpoints concerned with the urbanization of China’s countryside towns. Urban Plan. Forum 2004, 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F. Review and prospect of China’s urbanization and urban development since 1978. Planners 2009, 25, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, Y. Evolution, Characteristics, and Direction of China’s Urbanization since the Reform and Opening up: From the Perspectives of Population, Economy, and Institution. City Plan. Rev. 2020, 44, 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y. Century review and prospect of China’s urbanisation. Seeker 2001, 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, J.; Xu, J.; Yi, H. The fourth wave of urbanization in China. City Plan. Rev. 2006, 30, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, C. Policy evolution and research review of urbanization development in China. Rev. Econ. Res. 2013, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P. The Course, Achievement and Enlightenment of 70 Years of Urbanisation in New China. Shandong Soc. Sci. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S. Urbanization as a global historical process: Theory and evidence from sub-Saharan Africa. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2012, 38, 285–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Council. The Report of the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China. Available online: http://cpc.people.com.cn/n/2012/1118/c64094-19612151.html (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Lang, W.; Chen, T.; Li, X. A new style of urbanization in China: Transformation of urban rural communities. Habitat Int. 2016, 55, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Liu, W.; Lu, D. Challenges and the way forward in China’s new-type urbanization. Land Use Policy 2016, 55, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turok, I.; McGranahan, G. Urbanization and economic growth: The arguments and evidence for Africa and Asia. Environ. Urban. 2013, 25, 465–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Song, M.; Shi, K.; Jin, S.; Wang, M.; Zhang, W. The Spatial Differentiation of Urban Transition in China with the Model of Gradual Institutional Changes. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2016, 36, 1466–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Chen, W.; Liu, Y.; He, Q. Institutionalisation of public participation in China’s urban regeneration from the perspective of historical institutionalism: Three-stage cases in Guangzhou. Political Geogr. 2024, 108, 103036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, X. Transition of Chinese urban–rural planning at the new-type urbanization stage. Front. Archit. Res. 2015, 4, 341–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Ma, Y.; Li, X.; Zhuo, H. China’s New-type Urbanization from the Perspective of Modernization. Urban Dev. Stud. 2021, 28, 8–13+26. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Gaubatz, P. The Chinese City; ImprintRoutledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Urban China: Toward Efficient, Inclusive, and Sustainable Urbanization; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Coalition for Urban Transitions. Accelerating China’s Urban Transition; Tsinghua University: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, D.; Chen, M. Several viewpoints on the background of compiling the “National New Urbanization Planning (2014–2020)”. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2015, 70, 175–185. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Song, M.; Cui, L. Driving force for China’s economic development under Industry 4.0 and circular economy: Technological innovation or structural change? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 271, 122680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Structure and Change in Economic History; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, H. Strategy of Urban Transformation in China. J. Urban Reg. Plan. 2011, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kolodko, G.W. Ten Years of Post-Socialist Transition Lessons for Policy Reform; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 1999; Volume 2095. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, Y.; Yamamoto, K. Population concentration, urbanization, and demographic transition. J. Urban Econ. 2005, 58, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Liu, Y.; Long, H. The Study on Non-Agricultural Transformation Co-Evolution Characteristics of “Population-Land-Industry”: Case Study of the Bohai Rim in China. Geogr. Res. 2015, 34, 475–486. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Yang, P.; Zhang, B.; Hu, W. Spatio-Temporal Coupling Characteristics and the Driving Mechanism of Population-Land-Industry Urbanization in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Land 2021, 10, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, G.; Liu, D.; Yu, H.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, J. The Interaction of Population, Industry and Land in Process of Urbanization in China: A Case Study in Jilin Province. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, C.; Daisheng, T. The Evolution Logic, Basic Experience and Reform Path of Urbanization in the Past 70 Years. Economist 2020, 1, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Liao, H.; Yang, W.; Zhuang, W.; Shi, J. Urbanization Quality over Time and Space as Well as Coupling Coordination of Land, Population and Industrialization in Chongqing. Econ. Geogr. 2015, 35, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.C.S.; Ho, S.P.S. The State, Land System, and Land Development Processes in Contemporary China. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2005, 95, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, W.; Chi, W.; Lu, D.; Dou, Y. A comparative analysis of megacity expansions in China and the U.S.: Patterns, rates and driving forces. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 132, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.C.S. Reproducing Spaces of Chinese Urbanisation: New City-based and Land-centred Urban Transformation. Urban Stud. 2007, 44, 1827–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Huang, J.; Rozelle, S.; Uchida, E. Growth, population and industrialization, and urban land expansion of China. J. Urban Econ. 2008, 63, 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A. China Entering Post-industrial Era. J. Beijing Jiaotong Univ. 2017, 16, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China National Statistical Bureau. Statistical Bulletin of the People’s Republic of China on National Economic and Social Development 2020. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/202102/t20210227_1814154.html (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- Xu, M. The Experience of Migrant Workers and the Success Rate of Returning Migrant Workers’ Entrepreneurship: A Counterfactual Estimation Based on Propensity Score Matching. J. Cap. Univ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 22, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Chen, J.; Liu, D.; Zhao, X. Spatial differentiation and hierarchical collaborative zoning of rural homestead withdrawal potential:A case study of Yicheng City, Hubei Province. Resour. Sci. 2021, 43, 1322–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, C. Housing bubbles: A survey. Annu. Rev. Econ. 2011, 3, 559–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Lu, M. Can Policies Sustain an Even Distribution of Human Capital: Let History Tell Future. Acad. Mon. 2018, 50, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W. Response of Urban Regeneration to The Evolution of Urban Governance: A Pioneering Experiment of Shenzhen. Cities Plan. Rev. 2021, 45, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, S. Hotspot review of research and practice of urban regeneration in 2019. Sci. Technol. Rev. 2020, 38, 148–156. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, G.; Gong, Y.; Luo, G. Social Cognition and Evolution of Land Value-Added Benefits in Urban Village Reconstruction in Shenzhen. Urban Probl. 2019, 293, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, G.A. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qual. Res. J. 2009, 9, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuetherick, B. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Can. J. Univ. Contin. Educ. 2010, 36, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, A.G.; Yang, F.F.; Wang, J. Economic transition and urban transformation of China: The interplay of the state and the market. Urban Stud. 2015, 52, 2822–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, C. Transformation of danwei system: An angle of view on city changes in China. World Reg. Stud. 2007, 16, 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; Tian, X. The economic growth of cities at different scales in China under the impact of institutional change. Areal Res. Dev. 2010, 29, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Cui, Z.; Sun, C.; Han, Z.; Guo, J. Temporal and spatial pattern evolution of marine economic transformation effect in China. Geogr. Res. 2015, 12, 2295–2308. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Han, Z. Effective measure and influence factors analysis in the urban economy transition of 15 deputy provincial cities of China. Sci. Geogr. Sin 2015, 35, 1388–1396. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Y.; Tang, J. Study on Industrial Development Transformation of Shenzhen. J. Urban Reg. Plan. 2011, 4, 20–39. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, F.; Ma, R. Institutional transition and reconstruction of China’s urban space: Establishing an institutional analysis structure for spatial evolution. City Plan. Rev. 2008, 32, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Zhang, X. Socio-spatial structure of Hefei and its evolution during the transitional period: 1982–2000. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2015, 35, 1542–1550. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Z.; Bao, J. The impacts of cultural transformation on place becoming: A case study of Shenzhen overseas Chinese town. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2015, 35, 544–550. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y. Chinese cities in transition: Mixed spatial structures produced by a hybrid institutional model. Geogr. Res. 2015, 34, 2021–2034. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Yang, Y.; Leng, B. Characteristics, models and mechanisms of manufacturing enterprises migrations of large cities in Western China since 1949: Taking Lanzhou as an example. Geogr. Res. 2012, 31, 1872–1886. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. New City Space of Industry in China (NCSIC): Development Mechanism and Spatial Organization; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zong, H.; Wang, P.; Dai, J. The spatial layout of logistics parks in Chongqing urban area and its impacts on the urban structure. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2015, 35, 831–837. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, F.; Chen, C.; Liu, J. The relationship between service space and other function space of Changchun City in transition period. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2015, 35, 299–305. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Yang, G.; He, S. Housing differentiation in low-income neighbourhoods in large Chinese cities under market transition. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2014, 34, 897–906. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Lu, X. Evolution of accessibility spatial pattern of urban land use: A case of Huai’an City in Jiangsu Province. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2014, 34, 154–162. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, D. Formation and dynamics of the “Pole-Axis” spatial system. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2002, 22, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, H. Adjustment and prospect of China’s regional policy. Southwest Univ. Natl. 2008, 29, 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, C. Progress and the future direction of research into urban agglomeration in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2014, 69, 1130–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, W. Urban System, Urban Renewal and Unit Society -- Market Economy and the Change of Urban system in Contemporary China. Archit. J. 1996, 12, 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, D. Studies on China urban green transition based on PSR analysis. Tongji Univ. J. Soc. Sci. Sect. 2011, 4, 37. [Google Scholar]

| Data Source | Web of Science, Google Scholar, and CNKI. |

| Citation Index | SCIE or SSCI or AHCI or CSSCI |

| Year Published | 1990 to 2022 |

| Document Type | “Article” or “review” |

| Language | English or Chinese |

| Subject Category | “Urban studies”, “regional & urban planning”, or “Development Studies” |

| Sample Size | 61 |

| Term | Cluster | Frequency | Term | Cluster | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 3 | 23 | Framework | 2 | 13 |

| Region | 1 | 17 | Governance | 2 | 11 |

| Growth | 1 | 15 | Question | 3 | 11 |

| Case | 2 | 14 | State | 2 | 11 |

| Economy | 1 | 14 | Way | 3 | 11 |

| Practice | 2 | 14 | Term | 1 | 10 |

| Research | 2 | 14 | Example | 2 | 10 |

| Approach | 2 | 13 | Experience | 2 | 10 |

| Data | 1 | 13 | World | 1 | 10 |

| Urbanisation | 1 | 13 | Impact | 3 | 10 |

| New-Type Urbanisation | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| High-Speed Urbanisation | High-Quality Urbanisation | |

| Population | Separation of registered and actual residences | Unity between registered and actual residences |

| Land | Human–land allometry | Human–land balance |

| Industry | Traditional dependent industrialisation | Emerging service innovation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, H.; Chen, W.; Sun, S.; Yu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, C. Revisiting China’s Urban Transition from the Perspective of Urbanisation: A Critical Review and Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4122. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16104122

Liu H, Chen W, Sun S, Yu J, Zhang Y, Ye C. Revisiting China’s Urban Transition from the Perspective of Urbanisation: A Critical Review and Analysis. Sustainability. 2024; 16(10):4122. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16104122

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Hailiang, Weixuan Chen, Siqi Sun, Jiapei Yu, Yanhao Zhang, and Changdong Ye. 2024. "Revisiting China’s Urban Transition from the Perspective of Urbanisation: A Critical Review and Analysis" Sustainability 16, no. 10: 4122. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16104122

APA StyleLiu, H., Chen, W., Sun, S., Yu, J., Zhang, Y., & Ye, C. (2024). Revisiting China’s Urban Transition from the Perspective of Urbanisation: A Critical Review and Analysis. Sustainability, 16(10), 4122. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16104122