Abstract

The city center of Erzurum in the east of Turkey, Erzurum province, has structures with origins from the Anatolian Seljuk and Ilkhanid Periods to the present day, including the “Erzurum Castle”, “Ulu Mosque”, “Double Minaret Madrasa”, “Yakutiye Madrasa”, and “Three Kumbets.” It is home to one of the most important cultural heritages of Eastern Anatolia in history and faith tourism. Erzurum can be considered as the cradle of many cultures and civilizations with its deep historical past. Restoration (renovation) works around these monuments, which also contribute to the city’s identity, are important in terms of preserving historical monuments for the future. In this study, the importance of landscape projects and housing restorations in the city and its surroundings, in terms of harmony with the historical environment and monuments and urban identity, was investigated. In the questionnaire prepared for this purpose, we attempted to determine the perceptions of the protection, appreciation, and contribution aspects of the urban renewal works conducted in the tangible architectural heritage areas centered on Erzurum castle. The questionnaires, which included 5-point Likert-type questions, were distributed to 400 people. We sought the opinions of experts in decision-making mechanisms and academicians, as well as local people. As a result of the study, it has been determined that the city is generally not sensitive enough about the protection of historical neighbourhoods and monuments, and urban transformation projects do not contribute to conservation efforts in terms of conservation, sustainability, and visual perception. In addition, in terms of visual perception, it has been revealed that the newly developing regions of the city do not offer housing projects compatible with the historical environment, and that the relevant studies conducted are insufficient. The study also revealed that Erzurum Castle plays a central role in the perception of the historical environment. In terms of sustainability perception, it was determined that architectural restoration and landscape works have positive effects on cultural tourism, urban attractiveness, sense of belonging, quality of life, and prevention of migration. The prepared questions were divided into three groups: conservation sensitivity and perception, visual perception, and sustainability perception.

1. Introduction

The development of the understanding of conservation for the protection of urban spaces and cultural assets people and society instinctively want to protect emerged in Europe. This understanding has spread all over the world in the process. The examination of cultural assets, as well as transferring them to future generations and ensuring their continuity, has gained great importance. In the 1800s, conservation efforts began to be implemented through legal regulations developed within the scope of the understanding of conservation that emerged intellectually in Europe. Among these legal regulations, the most important tools that directly constitute conservation actions have been conservation laws [1,2]. However, until the 1800s, almost no state had a legal regulation on the concept of protection in the sense we use it today due to the influence of political formations in the world [3].

During the Middle Ages, structures representing the symbols of feudal authority were subjected to conservation efforts even without legal regulations. These structures included original architectural examples of the Middle Ages, such as castles, palaces, and religious buildings. However, with the end of the Middle Ages, these monumental structures were destroyed in many places but were later recognized as an important part of European culture. In the 19th century, the concept of conservation developed in Europe. National conservation laws were established, followed by international principles. The formation and development of this understanding of conservation were shaped by factors such as urban destruction and wars. The process of nationalization that began during the Renaissance after the Middle Ages encouraged the development of the concept of conservation and national conservation laws. In addition, international organizations contributed to conservation efforts after World Wars I and II [4].

The global spread of the concept of conservation has necessitated the creation of national and international legislation for the protection of cultural heritage buildings and sites. The main purpose of these legislations is to set principles for the protection of cultural heritage to define repair and intervention methods to preserve the authenticity of the buildings and sites and to ensure their transfer to future generations [5,6,7]. However, different conservation principles and approaches have been developed at different times for reasons such as period technology, definition of cultural heritage, determination of cultural heritage to be protected, approach, and political views. A detailed evaluation of national and international conservation legislation and the determination of conservation principles are of great importance for the transfer of the concept of conservation and the cultural heritage to be protected for future generations [8].

Cultural heritage comprises the tangible and intangible assets from the past to the present. It is a reflection of people’s knowledge, values, traditions, and beliefs. Architectural heritage, which is an important part of this heritage, is defined as buildings and building groups at different scales that should be subjected to a holistic conservation approach with all their values. Different approaches have been developed by societies throughout history, specialization areas have been established, relevant criteria have been determined, and legal regulations have been implemented [9,10,11]. In this process, the first term used to represent cultural heritage was “monument.” The content of this term evolved over time, and while it was a concept associated with archaeology until the late 17th century, it gained a meaning associated with memory, social memory, and aesthetics in the following periods [12]. Today’s conservation concepts and practices started to develop in the 19th century [13].

As a result of the studies conducted by international organizations for the protection of cultural heritage, many regulations have been established. Some of these regulations are in the form of recommendations that guide conservation practices, while others are binding and have been legally adopted by countries such as Turkey. However, these documents are insufficient to set standards for conservation practices because implementation varies according to the legal and administrative structures of countries and the characteristics of cultural assets [14,15]. Moreover, the level of development of conservation culture is a factor affecting the effectiveness of conservation. The necessity to protect cultural heritage stems from scientific, aesthetic, and natural values, as well as socio-cultural, symbolic, economic, and spiritual values [5,16].

The protection of cultural heritage is limited by the number of historical buildings and places. Factors such as insufficient financial resources, natural disasters, wars, neglect, indifference, and the wear and tear of materials lead to the loss of historical buildings. In order to restore the vitality of historic city centers, interventions such as transformation, street sanitization, pedestrianization, restoration, and facade sanitization are conducted in these areas [17].

In the context of cultural heritage and its components, which are the objects of preservation, societies developed different approaches throughout history to protect the values they have produced until they reach the current level of awareness. In this regard, expertise has emerged, and relevant criteria, legal regulations, and new organizations have been established [18]. In this historical process, the first concept used to represent cultural heritage was the term “monument.” The content of the monument concept evolved over time. While it was associated with archaeology until the end of the 17th century, in subsequent periods, it became related to memory, collective memory, and aesthetics [19]. In this historical evolutionary process, the concept and practices of preservation, as understood today, began to develop in the 19th century [20].

Although historical and cultural heritage is local, it is also national and universal since it represents the common values of humanity. [21,22,23]. One of the most crucial conditions for the identity-based development of cities is the preservation of historical texture and structures. Therefore, ensuring this preservation is among the primary and inevitable obligations of the authorities responsible for urban planning and development [24,25,26].

According to the World Heritage Convention adopted by the UNESCO General Conference in 1972, cultural heritage includes areas, groups of structures, and site areas that possess historical, aesthetic, archaeological, scientific, ethnological, and anthropological value. Cultural heritage, in its essence, does not merely refer to a historic building. It also includes the values of individuals, cultural accumulations, traditions, customs, ways of life, and the works created from these accumulations. The Amsterdam Declaration was issued to promote cooperation and exchange in the cultural field, as foreseen by the Helsinki Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe in July 1975. Some of the fundamental ideas of the conference included Europe’s architectural heritage, a priceless cultural value that instills awareness of common history and future in its peoples. Therefore, its preservation is crucial. Architectural heritage includes not only individually superior structures but also all urban and rural areas with historical and cultural significance [27,28,29,30].

The need to preserve cultural assets arises from different forms and is derived from the values classified as intrinsic, socio-cultural, symbolic, economic, and external values in the 21st century [31,32]. Protecting and preserving cultural assets that require protection due to their values is a common responsibility of humanity [23]. The fulfillment of this responsibility by society necessitates the existence of a culture of preservation, which is a fundamental concept that concerns all cultural values. In societies where a culture of preservation has formed and spread, individuals from various segments of society participate in preservation processes by assuming responsibility, approaching them consciously, and prioritizing public interest over personal gain. Therefore, in addition to international and national regulations, it is necessary to create and develop a widespread culture of preservation throughout society for the preservation of our cultural heritage. Recognizing, adopting, integrating into life, and knowing that we are obliged to transmit these values to future generations requires having a culture of preservation [33,34].

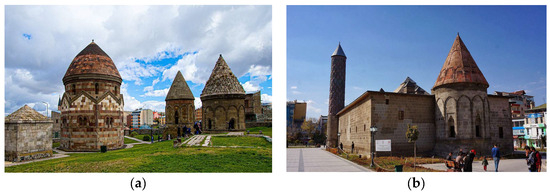

Erzurum is a historical and cultural city located in the Eastern Anatolia Region of Turkey. Erzurum’s history dates back thousands of years and has been home to various civilizations. The city attracts attention with both its historical richness and cultural heritage. Erzurum has been an important center of trade and cultural interaction since ancient times due to its location on the historical Silk Road. Many different civilizations such as the Urartians, Persians, Romans, Byzantines, Seljuks, Mongols, and Ottomans ruled in Erzurum. In addition, the city has many historical mosques, madrasas, and külliye under the influence of Islamic civilization [35]. Seljuk monuments in Erzurum are among the structures that enrich the cultural heritage of the region and offer important examples of Turkish–Islamic art. These works are of great historical and artistic importance. The complexes and tombs of the Seljuk period in Erzurum bear important traces of religious, cultural, and social life. These complexes include many buildings such as mosques, madrasahs, mausoleums, tombs, and fountains, and they reflect the culture of the Seljuk period, creating an identity unique to the region.

Double Minaret Madrasa and Ulu Mosque, built in the 12th century, are important Islamic architectural works [36]. Double Minaret Madrasa, one of the symbols of Erzurum, is especially one of the most important examples of Seljuk architecture. This madrasah, which attracts attention with its two minarets, is an artistic masterpiece not only in terms of architecture but also with the decorations and details it contains.

Erzurum became a great center of culture and art during the Seljuk period. The historical buildings built during this period reflect the beauties of Seljuk architecture. Seljuk artefacts in Erzurum represent a great richness not only in terms of architecture but also in historical, cultural, and artistic terms. These works contribute to the history and culture of the region by carrying the traces of the past to the present. At the same time, these artefacts are an important attraction point for tourists and researchers. Since the Seljuk period presented prominent examples of Turkish–Islamic art, structures such as Taşlıçay Bridge and Lala Mustafa Pasha Mosque bear the traces of this period [37,38,39,40].

As an Ottoman city, Erzurum’s traditional architecture is also very rich. There are examples of Turkish house architecture in many parts of the city. Woodwork, window details, and the general urban texture reflect the cultural heritage of the region. Erzurum has been open to the interaction of different cultures throughout history and a rich cultural heritage has emerged from these interactions. With its historical buildings, traditional lifestyle, and natural beauties, Erzurum continues to be an important cultural and historical destination for visitors. The Seljuk artefacts in Erzurum represent a great richness not only in terms of architecture but also in historical, cultural, and artistic terms. These artefacts contribute to the history and culture of the region by carrying the traces of the past to the present. At the same time, these artefacts are an important point of attraction for tourists and researchers, as they offer outstanding examples of Seljuk-era Turkish–Islamic art.

This study was conducted with the aim of evaluating conservation and urban renewal projects carried out in the province of Erzurum using a participatory planning approach. Indeed, the study area hosts significant architectural landmarks dating back to the Anatolian Seljuk and Ilkhanid periods up to the present day. In this context, this research is important for preserving and passing on the urban architectural heritage to future generations, contributing to the city’s identity, understanding the history and origins of the community, and highlighting the artistic, cultural, and aesthetic values that enrich the environment. Simultaneously, planning and implementing conservation and urban renewal efforts in a participatory manner are also important from economic, social, and cultural perspectives.

This study aims to assess the suitability of restoration and landscape renewal efforts in collaboration with local participants and experts, with the goal of providing alternatives and recommendations for urban renewal practices in the region based on the research findings. Additionally, another objective of the study is to enhance the community’s awareness of architectural heritage in Erzurum, with a focus on sustaining historical buildings and their surroundings with an original design and preserving them for future generations in a sustainable manner.

2. Materials and Methods

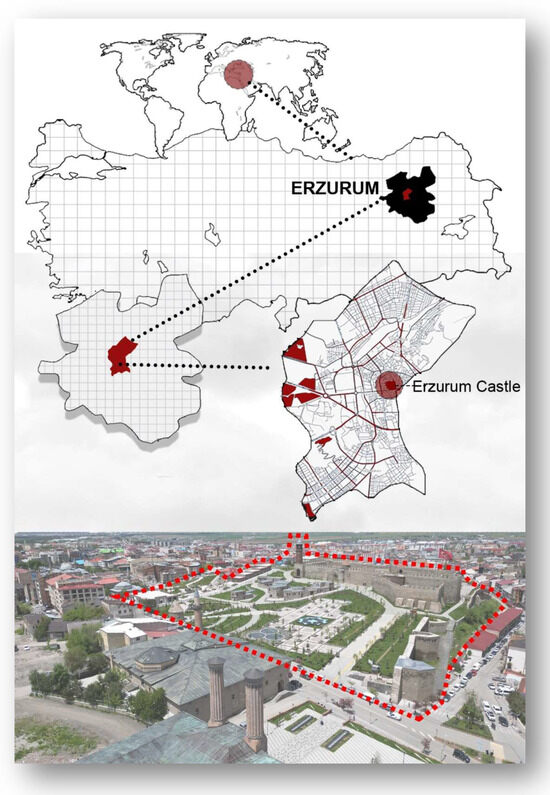

The main material of the study consists of the tangible historical and cultural architectural heritage artifacts located in Erzurum Castle and its immediate surroundings (Figure 1 and Figure 2). The location map of the study area was made using Photoshop 22.2 and Microsoft PowerPoint programs. In addition, all kinds of research and literature studies conducted for urban conservation, transformation, design, and protection purposes, as well as questionnaire forms applied to users via Google Forms, were used as auxiliary materials of the research.

Figure 1.

Location of the study area. (It was created by using archive photographs of Erzurum Metropolitan Municipality, Photoshop, and Mapbox programmes).

Figure 2.

Views of the architectural structures in the study area and its immediate surroundings. (a) Three Kumbets; (b) Yakutiye Madrasah; (c) Double Minaret (Hatuniye) Madrasah; (d,e) Erzurum Castle and its surroundings (Erzurum Metropolitan Municipality archive photographs were used).

The research was conducted with a methodology in which qualitative and quantitative research methods were used together. Within the scope of this research, which was carried out within the scope of a scientific research project, a questionnaire study was conducted for a group of experts who have knowledge on urban renewal and conservation issues in the historical environment and a group of local people. The expert group that the survey was conducted consists of people from various boards and commissions affiliated to the local administration and local administration in local governments, development agencies, higher education institutions, and the private sector, which includes members of professional disciplines such as landscape architecture, architecture, interior architecture, urban and regional planning, history, and art history. In the formation of the expert group, it was considered that they have knowledge about the field and have the competencies to make evaluations. The local community group was sampled according to the population of Erzurum city center, where the study will be conducted, and it includes a group of people who currently reside in the city and have been to the area before (sightseeing, visiting and/or residing).

Hypotheses of the study

Conservation and urban renewal works conducted in the historic environment;

- (a)

- Protection/Sensitivity perception

- (b)

- Visual perception

- (c)

- Sustainability perception

Hypothesis 0 (H0).

There is no significant difference between the opinions of the local people and the expert group in terms of conservation sensitivity, visuality, and sustainability perception.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

There is a significant difference between the opinions of the local people and the expert group in terms of conservation sensitivity, visuality, and sustainability perception.

The number of surveys conducted will be determined according to the simple random sampling method, and according to TUIK 2020 data, the population of Erzurum province is 758 279. The city, which is the fourth largest province of Turkey, has 20 different districts and has a surface area of 25,005 km2. The number of people living in the city center is 348,156, according to 2022 data [41,42,43]. In order to increase the reliability of the survey results in determining the population size in the study, the number of interviewers was determined as 758 279 people based on the city population instead of the city center population information. The following formula used by [42,43,44] was used to determine the sample size.

- n: Sample size

- N: Number of units in the population (758.279)

- p: Incidence rate of the examined event (0.5)

- q: Non-occurrence rate of the examined event (0.5)

- t: Value found from t table (t value 1.96 for 0.05 at 95% confidence interval)

- d: Sampling error (0.05)

n = 758,279 × 0.5 × 0.5 × (1.96)2: (758,279 − 1) × (0.05)2 + (1.96)2 × 0.5 × 0.5 = 384

According to the above formula, the sample size for the study was determined as 384, but the number was completed to 400 by considering the margin of error. In order to collect data within the scope of the study, a survey consisting of 23 questions under the categories of Conservation, Liking, and Contribution (socio-cultural-economic) was conducted with both participant groups. The questionnaire was created according to a modified Likert scale [44,45]. Participants were asked to provide scores ranging from 1 to 5 to the options presented in order to obtain an average score for each question. In scoring, “very low, Option 1; low, Option 2; medium, Option 3; high, Option 4; and very high, Option 5” represented the scoring system.

The questionnaires were analyzed with IBM SPSS Statistics 22 program, and the mean score and standard deviation were calculated for each scale. It was also evaluated whether the questionnaires differed significantly according to other demographic information. Two different statistical analyses were used: One-Way ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) for Income, Education, and Field of Activity, and Independent-Samples t test (Independent-Samples t test) for gender and participant group.

The questionnaire was prepared under three different (a/b/c) scales consisting of 25 questions. These are “Conservation Sensitivity and Perception”, “Visual Perception”, and “Sustainability Perception.” The questionnaires were analyzed with IBM SPSS Statistics 22 program, and the mean score and standard deviation were calculated for each scale. It was also evaluated whether the questionnaires differed significantly according to other demographic information. Two different statistical analyses were used: One-Way ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) for Income, Education, and Field of Activity, and Independent-Samples t test (Independent-Samples t test) for gender and participant group.

In order to determine between which two groups the significant differences (p < 0.05) in the One-Way ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) test were realized, the homogeneity test (Test of Homogeneity of Variance) and the Games–Howell test were first applied, one of the Post Hoc test types was applied for the questions whose variance between groups was not equally distributed (p < 0.05), and the Tukey test was applied for those whose variance between groups was equally distributed. In the analyses, 0.05 (p = 0.05 at 95% confidence interval) was used as the significance value (sig. = p). Before starting the tests for the Independent-Samples t-Test, the normality test of the answers provided to the questions was performed, and it was determined that the skewness and kurtosis values in the range of (−1.5)–(+1.5) showed normal distribution [44]. The demographic characteristics of the respondents are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the respondents.

3. Research Findings

Evaluation of Analysis Results for Determining the Perception towards the Protection of Tangible Architectural Heritage Monuments Centering on Erzurum Castle

Below are 5-point Likert-type questions and abbreviations of these questions to determine the perception towards the protection of tangible architectural heritage monuments centered on Erzurum Castle (Table 2).

Table 2.

5-point Likert-type questions and their abbreviations.

Below (Table 3), the results of the t test for the different categories of “Conservation Sensitivity and Perception”, “Perception of Visuality”, and “Perception of Sustainability” of the different groups of participants consisting of local people and experts are presented. Accordingly, there are significant differences between the variables in terms of conservation sensitivity and perception, especially C5 (pedestrianization of the existing settlement network connected to the historical environment and monuments is beneficial) and C6 (in approaches and practices related to the historical environment and monuments, a science or consultancy from the disciplines of art, engineering, urban design, architecture, landscape architecture, interior architecture, art history, transportation, etc.) is required. In approaches and practices related to the historical environment and monuments, the difference between the variables and the average conservation sensitivity and perception was found to be statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Table 3.

t test results for the perception of different participant groups on the protection of tangible architectural heritage in Erzurum Castle and its surroundings.

If the results are evaluated in terms of visual perception, it is seen that there are significant differences between the variables, especially V1 (newly developed areas of the city are in integrity with the historical environment and monuments), V2 (mass housing projects such as Oba houses built on the border of Mecidiye bastions are compatible with the historical environment), V3 (mass housing projects such as “Green Yakutiye” and “Kayı” developed in the south of the historical urban fabric are compatible with the historical environment and monuments), V4 (from the region where the historical urban fabric is located, as well as the difference between variables), V7 (landscape projects and housing restorations in and around the city are compatible with the historical environment and monuments), V8 (existing transportation structure, including Republic Street, the Tebriz gate intersection, and side connection roads is compatible with the historical environment and monuments), and Vmean (Average Perception of Visuality) was found to be statistically very significant (p < 0.05).

Finally, if the opinions of the participants regarding the perception of sustainability are evaluated, it is seen that there are significant differences between the variables, especially S1 (architectural restoration and landscape works related to the historical environment and monuments contribute to the sustainability of cultural tourism) and S2 (architectural restoration and landscape works related to the historical environment and monuments support the process of Erzurum becoming a center of attraction), while the difference between S7 (organizing a national urban design competition process at the beginning of the process of architectural restoration and landscaping works related to historical environment and monuments would contribute to the process of obtaining a more participatory and owned historical urban fabric) and Smean (mean Perception of Sustainability) variables was found to be statistically very significant (p < 0. 05).

4. Discussion

Each city has a special architecture reflecting its own history and elements reflecting its own identity. In the city of Erzurum, which is located at an altitude of approximately 2000 m in Turkey with a settlement history of approximately 5000 years, tangible architectural heritage monuments are an important source of richness, in addition to the monuments belonging to different periods, centered on an important Erzurum Castle specific to the city.

From this point of view, the research aims to reveal the awareness of architectural heritage, which is a component of cultural heritage, in the case of Erzurum [45,46], where important architectural heritage monuments have been produced throughout the settlement history dating back to 4000 BC. The study aims to reveal which of these cultural assets are perceived as architectural heritage by urban dwellers, who may or may not know the values that any object or area should have in order to gain the status of cultural heritage but who continue their existence together with examples of architectural heritage in their daily lives in the urban space and by expert groups consisting of different professional groups. As a result of the analysis made in line with the purpose and scope of the research, it has been observed that studies on the perception and awareness of cultural assets and conservation culture have become widespread in the 2010s. In this context, one of the pioneers of the studies in the international literature [47]) tried to reveal an awareness of cultural heritage in the case of Arizona (USA). Subsequent studies [48] emphasized the critical importance of cultural heritage awareness in heritage conservation and management, focusing on the work of actors to raise awareness to protect heritage in the case of Mysore city. Ref. [49] presents awareness of cultural heritage in the case of Turkey by emphasizing the importance of community archaeology and local museums in the cases of Çatalhöyük/Corum, Ani Ruins/Kars, and Hattuşaş/Corum.

When the studies on architectural heritage in the international literature are examined, it is seen that [50,51] examined the public’s perception of the protection of heritage buildings in Malaysia. While [52] determines the awareness of architectural heritage in the case of traditional settlements in Greece, ref. [53] analyzes the perception of the cultural importance of architectural heritage in the case of Aveiro, Portugal based on the fact that architectural heritage is an important motivation for tourists to visit tourism destinations. However, it is seen that research on the subject in the national literature, especially in the field of tourism, has increased in the last decade. Among these studies, ref. [54], which focuses on local people, analyzes the views on cultural heritage, cultural tourism, and tourism in the case of Cumalıkızık village; ref. [55] determines the perceptions and attitudes on cultural heritage, as well as protection of cultural heritage and its use for tourism purposes in the case of Osmaneli. Emphasizing that cultural heritage is an important actor in the protection of cultural heritage, ref. [56] presents and tests a theoretical model that deals with the relationships between cultural heritage and attachment to place and local people, perception towards cultural heritage, and attitude towards protection. In their study, ref. [57] determined the consciousness and awareness levels of the people regarding this cultural heritage and their tendency to participate in the protection processes of these values in the example of rock-carved places in the Karaman–Taşkale village. In addition to these studies focusing on the perception and awareness of local people, studies focusing on university students are common. Among these, ref. [58] revealed the awareness and experience levels of students regarding the natural and cultural heritage of Sivas, while [59] examined students’ awareness of cultural heritage in the same city. In addition, ref. [60] determined the perceptions and awareness of university students studying geography regarding universal cultural heritage values and assets in the case of Turkey.

It is seen that in most of the studies focusing on students in the field of awareness and perception of cultural heritage, students from the field of tourism (tourism guidance, tourism management and hotel management, and tourism and hotel management) are determined as the sample. Among these, ref. [61] reveals students’ perceptions of the concept of cultural heritage, ref. [62] measures students’ perceptions of tangible cultural assets, and [63] determines students’ attitudes towards cultural heritage. However, while there are no studies directly related to awareness and perception of architectural heritage in the national architectural literature, ref. [64] emphasized that the main actor in cultural heritage conservation is the individual and the importance of individual awareness, consciousness, and education. It also examined virtual reality applications as an awareness-raising tool [65]. In short, the literature review shows that at national and international scales, the topic is popular in the field of tourism, which considers cultural heritage as a tourist product that increases the attractiveness of tourism centers rather than in the fields of expertise that design the built environment where architectural heritage is located and/or are involved in the conservation processes of existing architectural heritage. In addition, in none of the studies focusing on the perception and awareness of architectural heritage, the expert group (architects, landscape architects, city and regional planners, local administrators, engineers, etc.), which can be considered to have different levels of knowledge about architecture and architectural heritage, and different sample groups such as city residents, visitors to the city, and students, which constitute the local public group, have not been put forward within the framework of conservation sensitivity, visuality, and sustainability perception. In addition, there are not many studies in the literature to determine the effects of landscape and restoration works centered on Erzurum Castle on the perception and awareness of cultural heritage and architectural heritage. For these reasons, this study, which aims to contribute to filling the gap in the literature, is thought to be very important in terms of explaining issues such as the importance of the public’s perception of cultural assets, which emphasizes human and human values, especially since the 1970s, from the international regulations that guide conservation policies and practices in the following chapters, as well as the necessity of raising public awareness, education, and awareness in order to ensure conservation.

This study attempted to determine the architectural assets that the interviewee groups participating in the survey, who can be considered to have different levels of experience and knowledge about architecture and architectural heritage in Erzurum, are aware of and think that they should be protected. In this way, it aims to reveal the awareness of the citizens of architectural heritage and the restoration and landscaping works conducted in this area and to reveal the importance of historical and cultural areas centered on Erzurum Castle, which is an important architectural heritage of the city of Erzurum, which constitutes the sample of the research, at different scales and through the eyes of the participants.

The results obtained from this study, which was conducted to determine the architectural assets that the interviewee groups are aware of and believe should be protected, reveal the awareness of the citizens towards architectural heritage and which cultural assets they perceive as architectural heritage, are listed below:

In terms of conservation sensitivity and perception,

- Erzurum’s historical neighborhoods and monuments in general should be protected,

- Newly developing areas of the city are integrated with the historical environment and monuments,

- Restoration and landscaping of the double minaret madrasa contributed to the preservation of the historical environment,

- A scientific or advisory board from the disciplines of art, engineering, and urban design (architecture, landscape architecture, interior architecture, art history and transportation, etc.) should take part in the approaches and applications related to the historical environment and monuments, which will contribute to a more qualified historical texture.

In terms of visual perception,

- Newly developing areas of the city are not integrated with the historical environment and monuments,

- Mass housing projects (Oba Houses) built on the border of Mecidiye Bastions are not compatible with the historical environment,

- Mass housing projects such as “Green Yakutiye” and “Kayı”, which developed in the south of the historical urban fabric, are not compatible with the historical environment and monuments,

- Erzurum Castle has a central location that visually perceives the historical and modern spaces/areas/regions of Erzurum,

- The implementation project for the city square around Yakutiye Madrasah and Lalapaşa Mosque is not compatible with the historical environment and monuments,

- The existing transportation structure (Republic Street, Tebriz gate junction, and side connection roads) is not compatible with the historical environment and monuments,

- The historical artifacts included in the study (“Erzurum Castle”, “Ulu Mosque”, “Three Kumbets”, “Double Minarets (Hatuniye) Madrasah”, and “Yakutiye Madrasah”) strengthen the identity of the historical environment as a whole.

In terms of Sustainability Perception,

- Architectural restoration and landscaping works related to the historical environment and monuments support the process of Erzurum becoming a center of attraction,

- Architectural restoration and landscaping works related to historical environment and monuments will have preventive effects on migration from Erzurum,

- The results were obtained for the judgment that organizing a national urban design competition process at the beginning of the architectural restoration and landscaping works related to the historical environment and monuments would contribute to the process of obtaining a more participatory and owned historical urban fabric, and these results were found to be statistically very significant (p < 0.05) at 95% confidence interval in different participant groups (Table 2 and Table 3).

These results obtained in the case of Erzurum show that although the perception of local people about what should be protected is mostly similar to that of experts, it can also differ according to the field of activity, education, and gender distribution. This raises new research questions for this and future studies.

The results and suggestions obtained from the open-ended questions are listed below.

While trying to take photographs in historical places, there is visual pollution that reduces the quality. For example, items such as electricity poles, wires, flags and banners, especially flags and visuals hung during election times, and especially subliminal advertisements that do not fit the historical place, present a very ugly image.

- Electricity wires can be placed underground.

- Modern construction elements are incompatible with the historical texture.

- It is not enough just to conduct renovation works in the region. These works should be done in accordance with the historical texture. In this sense, the renovation works in Double Minaret Madrasa are inadequate and incompatible with the historical texture.

- The color of the stone material used in the restoration made later on the front and right facade of the entrance of the Grand Mosque is very incompatible with the color of the existing material.

- Pedestrianization of the entire historical texture by considering the whole historical texture together will provide more advantageous use of space and make the historical texture effective.

- The buildings to the south of the double minaret madrasah and, especially, the four-story modern buildings adjacent to the Narmanlı Mosque should be removed.

- It should be done without disturbing the historical texture and image.

- Sitting, resting, and cafeteria-style structures close to the castle should be removed from the area, and this castle and its surroundings should be watched in its natural state.

- Modern buildings around Erzurum Castle and its surroundings, including Three Kumbets and Double Minaret Madrasa historical and cultural assets, should be removed.

- Due to the increasing need for housing, necessary laws should be enacted to ensure that new houses are built in the city that do not disrupt the historical texture.

- Keeping in mind that historical cities are world heritage, a balance between conservation and utilization should be observed.

- Erzurum is a “Seljuk City” and should be restored without damaging the identity theme.

- A “Tourism Destination Program” should be produced by including architectural heritage centered on Erzurum Castle in urban restoration.

- Erzurum Provincial Directorate of Culture and Tourism, universities, and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) must take part in restorations.

- Financial concerns and rent-seeking should not be considered in historical buildings and their surroundings.

- Plant materials and flooring materials suitable for historical monuments should be used. Motifs from the Seljuk period suitable for Erzurum and its historical past can be utilized in landscaping works.

- The Provincial Directorate of National Education should raise awareness of the whole society with the “Awareness Education Project for Tourism and Historical and Cultural Architectural Heritage.”

- Non-Governmental Organizations, the public, and universities should conduct training and awareness-raising activities for sustainable tourism and the management of cultural and historical assets.

- A corridor can be created between historical textures and pedestrianization works. The works should be conducted in this corridor, and elements that will emphasize the historical texture should be included.

Ref. [24] underlines that in Turkey, the evaluation of modern architectural structures as part of cultural heritage has been discussed in a limited circle in a process that started in the 2000s. It interprets this situation as Turkey is still in the process of awareness and concern about modern heritage, which is still the first stage of conservation. In addition to the international developments in today’s world, the importance of taking some steps on a national and local scale in addition to the international developments in today’s world to develop awareness and conservation culture for cultural assets, especially the architectural heritage, which is the focus of this study, once again emerges. The creation and development of a conservation culture for the protection of architectural heritage officially entered the world agenda with the 1985 European Convention for the Protection of Architectural Heritage. However, the emphasis on conservation culture in this document, which is the starting point for discussions, has not been sufficient to establish practical standards for conservation practice in Turkey, for example. For this reason, the development and dissemination of a culture of conservation, which requires policies and actions for a wide range of actors, including individuals, institutions, and organizations, should be carefully considered as part of cultural policies. In this context, a strategy for the creation and dissemination of a culture of conservation in society can be put into practice through actions to be pursued at different levels, especially at national and local levels.

5. Conclusions

This study focuses on the conservation, perception, and sustainability of historical environment and monuments in Erzurum. According to the findings, which are divided into categories and obtained from the perspectives of the expert group and local people, the city is generally not sensitive enough to the protection of historical neighbourhoods and monuments, and urban transformation projects do not contribute effectively to this protection. In terms of visual perception, housing projects that are compatible with the historical environment have not been presented in the newly developing regions, and the studies conducted in this direction have been insufficient. However, Erzurum Castle plays a central role in the perception of the historical environment. Moreover, in terms of sustainability, architectural restoration and landscape works have positive effects on cultural tourism, urban attractiveness, sense of belonging, quality of life, and prevention of migration. This study provides important findings that support the preservation of Erzurum’s historic environment and building a sustainable future. It also emphasizes the necessity of an interdisciplinary approach to the conservation of historic environments and monuments. The results obtained from the study will form the basis for the studies to be conducted in the development process of the city, which has a very rich potential in terms of historical and cultural assets. In particular, it is thought that this research will provide important contributions to the issues to be considered in terms of visuality, sustainability, and conservation perception in both restoration, construction, and outdoor arrangements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.A.K.; methodology, E.A.K. and M.Ö.; writing, E.A.K. and M.Ö.; verification, E.A.K., I.S., M.Ö., F.K. and A.K.; formal analysis, E.A.K., I.S. and M.Ö.; sources, E.A.K., I.S., F.K. and A.K; research, E.A.K. and I.S.; data curation, E.A.K., I.S., F.K. and A.K. writing-original drafting, and editing, E.A.K., I.S., M.Ö., F.K. and A.K. All authors have read and accepted the published version of the article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Ataturk University Scientific Research Projects Coordination Unit within the scope of Basic Research Project No. FBA-2021-9734.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects participating in the study. At the same time, the study was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. It was conducted with the approval of Atatürk University Science and Engineering Sciences Ethics Committee with the decision numbered 60665420-000-E.2100135449.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their sincere appreciation to the Ataturk University Scientific Research Projects Coordination Unit for support. The authors would also like to thank Landscape Architect Berhan AKSAKAL, who works at Erzurum Metropolitan Municipality and provided the archive photographs of Erzurum.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mammoli, R.; Mariotti, C.; Quattrini, R. Modeling the fourth dimension of architectural heritage: Enabling processes for a sustainable conservation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadresin Milic, R.; McPherson, P.; McConchie, G.; Reutlinger, T.; Singh, S. Architectural history and sustainable architectural heritage education: Digitalisation of heritage in New Zealand. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Julián, J.E.; Lara, L.; Moyano, J. Implementation of a TeamWork-HBIM for the Management and Sustainability of Architectural Heritage. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baysan, N. Change Process of Historical Environmental Protection Legislation: İzmir Mithatpaşa Street Example. Master’s Thesis, Department of City and Regional Planning, Institute of Science and Technology, Dokuz Eylül University,, İzmir, Turkey, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Du, Y.; Yang, M.; Liang, J.; Bai, H.; Li, R.; Law, A. A review of the tools and techniques used in the digital preservation of architectural heritage within disaster cycles. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchi, F.E. Renewable Energies and Architectural Heritage: Advanced Solutions and Future Perspectives. Buildings 2023, 13, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moneta, A. Architecture, heritage, and the metaverse. Tradit. Dwell. Settl. Rev. 2020, 32, 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Sigmund, Z. Sustainability in architectural heritage: Review of policies and practices. Organ. Technol. Manag. Constr. Int. J. 2016, 8, 1411–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- De Medici, S. Italian architectural heritage and photovoltaic systems. Matching Style Sustain. Sustain. 2021, 13, 2108. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Liu, G.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J. Identifying the critical stakeholders for the sustainable development of the architectural heritage of tourism: From the perspective of China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addison, A.C.; Gaiani, M. Virtualized architectural heritage: New tools and techniques. IEEE Multimed. 2000, 7, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G. China’s architectural heritage conservation movement. Front. Archit. Res. 2012, 1, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croci, G. The Conservation and Structural Restoration of Architectural Heritage; WIT Press: Southampton, UK, 1998; p. 249. [Google Scholar]

- De Luca, L.; Busayarat, C.; Stefani, C.; Véron, P.; Florenzano, M. A semantic-based platform for the digital analysis of architectural heritage. Comput. Graph. 2011, 35, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, Y.D. A spatial reading on environmental urban identity: The place of stamps as cultural heritage in urban memory. Mageron 2022, 3, 461–485. [Google Scholar]

- Dolores, L.; Macchiaroli, M.; De Mare, G. Sponsorship for the sustainability of historical-architectural heritage: Application of a model’s original test finalized to maximize the profitability of private investors. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özgönül, N. International Protection Legislation. In Cultural Heritage Legislation; Akpolat, M.S., Ed.; Anadolu University: Tepebaşı, Turkey, 2012; pp. 26–51. [Google Scholar]

- Angin, S.N.; Külekçi, E.A.; Yilmaz, H. Analysing the Relationship between Urban Identity and Cultural Landscape in Authentic Culture in the Case of Erzurum Province. City Acad. 2020, 13, 556–569. [Google Scholar]

- Aşur, F.; Külekçi, E.A. The Relationship between the Adorability of Urban Landscapes and Their Users Demographic Variables: The Case of Edremit, Van/Turkey. J. Int. Environ. Appl. Sci. 2020, 15, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kıvrak, N. Examination of Architectural Design Principles in Istanbul Eminönü Hanlar District in the Context of ‘Revitalization of Old City Spaces’. Master’s Thesis, F.B.E. Department of Architecture, Institute of Science and Technology, Yıldız Technical University, Istanbul, Turkey, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ronsivalle, D. Relevance and Role of Contemporary Architecture Preservation—Assessing and Evaluating Architectural Heritage as a Contemporary Landscape: A Study Case in Southern Italy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncer, M.; Madran, E. Historical Development of the Concept of Conservation. In Cultural Heritage Legislation; Akpolat, M.S., Ed.; Anadolu University: Tepebaşı, Turkey, 2012; pp. 2–21. [Google Scholar]

- Omay Polat, E.E.; Can, C. The Concept of Modern Architectural Heritage: Definition and Scope. MEGARON/Yıldız Tech. Univ. Fac. Archit. E-J. 2008, 3, 177–186. [Google Scholar]

- Aydeniz, N.E. Development of the Concept of Urban Archeology in the World and Its Reflections in Turkey. J. Yasar Univ. 2009, 4, 2501–2524. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, H.; Ge, J.; Liu, R.; He, L. Feature Recognition of Regional Architecture Forms Based on Machine Learning: A Case Study of Architecture Heritage in Hubei Province, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowse, A. Back to the Future: An Integrated Approach to Heritage Conservation and Community Planning. Doctoral Dissertation, The University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlidis, G. Recommender systems, cultural heritage applications, and the way forward. J. Cult. Herit. 2019, 35, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez-Almendros, S.; Obrador, B.; Bach-Faig, A.; Serra-Majem, L. Environmental footprints of Mediterranean versus Western dietary patterns: Beyond the health benefits of the Mediterranean diet. Environ. Health 2013, 12, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchetti, N.; Curci, A.; Gatto, M.C.; Nicolini, S.; Mühl, S.; Zaina, F. A multi-scalar approach for assessing the impact of dams on the cultural heritage in the Middle East and North Africa. J. Cult. Herit. 2019, 37, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. 2023. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/conventiontext/ (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Demas, M. Planning for Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites: A Values-Based Approach. In Management Planning for Archaeological Sites. An International Workshop Organized by the Getty Conservation Institute and Loyola Marymount University; Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 27–54. [Google Scholar]

- Levent, Y.S. Public Interest Principle in Conservation Policies and Practices Regarding Cultural Heritage. Soc. Democr. 2011, 5, 115–132. [Google Scholar]

- Aşur, F.; Akpinar Kulekci, E.; Perihan, M. The role of urban landscapes in the formation of urban identity and urban memory relations: The case of Van/Turkey. Plan. Perspect. 2022, 37, 841–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erzurum. 2023. Available online: https://www.kulturportali.gov.tr/turkiye/erzurum (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Kulözü Uzunboy, N.; Yeşiltepe, A.D. Erzurum’s architectural heritage and awareness of architectural heritage. J. Int. Soc. Res. 2021, 14. [Google Scholar]

- İsmailoğlu, S.; Torun, F.K. The Adventure of a Cultural Heritage: Erzurum Feyzullah Efendi Mansion. J. Humanit. Tour. Res. 2022, 12, 573–584. [Google Scholar]

- Özkan, H. Erzurum Fountains with Inscriptions. Turk. World J. Lang. Lit. 2018, 45, 345–370. [Google Scholar]

- Aydın, T. Erzurum Double Minaret Madrasa Stone Decoration Samples. Karamanoğlu Mehmetbey Univ. J. Soc. Econ. Res. 2012, 2012, 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Kategori: Erzurum Ilinin Ilçeleri. Available online: https://tr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kategori:Erzurum_ilinin_il%C3%A7eleri (accessed on 9 October 2023).

- Erzurum Nüfusu. 2023. Available online: https://www.nufusu.com/il/erzurum-nufusu (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Kalıpsız, A. Statistical Methods; Publication No: 2837/294; Faculty of Forestry, Istanbul University: Istanbul, Turkey, 1981; p. 558. [Google Scholar]

- Özdamar, K. Modern Scientific Research Methods; Kaan Bookstore: Eskişehir, Turkey, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, F.; Tornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students; Pearson Publications: Mexico City, Mexico, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Likert, R.; Roslow, S.; Murphy, G. A simple and reliable method of scoring the Thurstone attitude scales. J. Soc. Psychol. 1934, 5, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S.; Ullman, J.B. Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2013; Volume 6, pp. 497–516. [Google Scholar]

- Kulözü, N. A Spatial Modernization Story: Erzurum City and the Formation of Double Texture in its Urban Space. İdealkent 2016, 7, 22–47. [Google Scholar]

- Nyaupane, G.P.; Timothy, D.J. Heritage Awareness and Appreciation Among Community Residents: Perspectives from Arizona, USA. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2010, 16, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, B.; Swamy, C. Creating Awareness for Heritage Conservation in The City of Mysore: Issues and Policies. Int. J. Mod. Eng. Res. (IJMER) 2013, 3, 698–703. [Google Scholar]

- Apaydın, V. Heritage Values and Communities: Examining Heritage Perceptions and Public Engagements. J. East. Mediterr. Archeol. Herit. Stud. 2017, 5, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhari, N.F.N.; Mohamed, E. Public Perception: Heritage Building Conservation in Kuala Lumpur. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 50, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katapidi, I. Examining Awareness of Heritage in Greek Traditional Settlements. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. -Urban Des. Plan. 2015, 168, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Carneiro, M.J. The Influence of Interpretation on Learning About Architectural Heritage and on the Perception of Cultural Significance. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetin, T. Perception of cultural heritage and tourism in Cumalıkızık village. Natl. Folk. J. 2010, 11, 181–190. [Google Scholar]

- Okuyucu, A.; Somuncu, M. Determination of Local People’s Perceptions and Attitudes in the Protection of Cultural Heritage and Use of Cultural Heritage for Tourism Purposes: The Case of Osmaneli District Centre. Ank. Univ. J. Environ. Sci. 2012, 4, 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- İşçi, C.; Güzel, B.; Ataberk, E. Does Loyalty to Place and Local People Affect Attitude towards Cultural Heritage? Balıkesir Univ. J. Inst. Soc. Sci. 2018, 21, 583–606. [Google Scholar]

- Turgut Gültekin, N.; Uysal, M. Cultural Heritage Awareness, Awareness and Participation: The Case of Taşkale Village. OPUS Int. J. Soc. Res. 2018, 8, 2030–2065. [Google Scholar]

- Akkuş, G.; Karaca, Ş.; Polat, G. Heritage Awareness and Experience: An Exploratory Study for University Students. J. Acad. Overv. 2015, 50, 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, S. Investigation of Primary School Students’ Sensitivity to Cultural Heritage: A Mixed Method Research. J. Kirsehir Educ. Fac. 2023, 24, 451–510. [Google Scholar]

- Bahtiyar Karadeniz, C. Assessment for Awareness and Perception of the Cultural Heritage of Geography Students. Rev. Int. Geogr. Educ. Online 2020, 10, 39–64. Available online: http://www.rigeo.org/vol10no1/Number1Spring/RIGEO-V10-N1-2 (accessed on 4 November 2023). [CrossRef]

- Köroğlu, Ö.; Ulusoy Yıldırım, H.; Avcıkurt, C. Investigation of Perceptions Regarding the Concept of Cultural Heritage Through Metaphor Analysis. Tour. Acad. J. 2018, 5, 98–113. [Google Scholar]

- Özgeriş, M.; Karahan, A.; Külekçi, E.A.; Demircan, N.; Sezen, İ.; Karahan, F. Evaluation of Tangible Cultural Heritage Examples with Sustainable Tourism Principles: Haho Monastery (Erzurum). Turk. J. Landsc. Res. 2023, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Keskin, M.; Saçlı, Ç. Perceptions of Tourism Students towards the Tangible Cultural Heritage Value of Hatay Province: The Case of İskenderun Technical University. Anemon Muş Alparslan Univ. J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 8, 335–343. [Google Scholar]

- Güneş, E.; Alagöz, G. A Research on Cultural Heritage Attitudes of Students Receiving Tourism Education. Adıyaman Üniv. Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi 2018, 29, 753–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sürücü, O.; Başar, M.E. Virtual Reality as an Awareness Tool in Protecting Cultural Heritage. Artium 2016, 4, 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Karahan, F.; Akpınar, E.; Karaman, M. How should we protect our architectural heritage? An Example from Northeast Anatolia Region: Öşvank Church. Art J. 2008, 13, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).