Abstract

The Amazon Rainforest suffers from unsustainable exploitation and encroachment on native peoples’ territories, leading to poverty and environmental destruction. This inquiry aims to understand the impact of deforestation on the economic development of communities and peoples and the relationships between persistent poverty and social pathologies. The research project employed empirical and conceptual methods, collecting data through interviews and constructing a systemic model concerning pathological dynamics within the Amazon region. The study found traps involving innovation, biodiversity, capacity building, access to economic assets, social development, cultural identity, access to knowledge, savannization, and forest appropriation. A systemic approach that reconnects with nature is essential to establish a sustainable economy in the Amazon rainforest. Proposed solutions include an ecological economy, stopping deforestation, encouraging entrepreneurship, valuing tradition, safe environment, building skills and competencies, increasing information and communication effectiveness, and fostering cooperation. This research seeks fundamentally new solutions that reach beyond the existing regime and contributes to establishing a new paradigm for the Amazon Forest.

1. Introduction

The unsustainable exploitation of the Amazon Rainforest and the increasing encroachment on the territories of native peoples have caused trails of poverty and destruction [1]. The Brazilian Legal Amazon is home to the world’s largest concentration of isolated indigenous peoples. Nevertheless, they face serious risks from the interests of exploitative groups who wish to extract natural resources from preserved areas [2]. According to studies, the threats faced by indigenous peoples in the Amazon increase their vulnerability, making it essential to quickly contain illegal actions within and around these territories to ensure the protection of the rights of these populations [3].

Invasions on indigenous lands are not a recent phenomenon. Since the arrival of European colonizers, indigenous people have been expelled from their lands and subjected to all kinds of violence [4]. However, the situation has recently worsened with increased pressure to exploit the region.

In the Amazon, the challenges begin with the need for public policies, which contribute to an unplanned expansion of cattle ranching and agriculture [5], and a need for more consensus on promoting sustainable use of the forest and supporting infrastructure. In addition, extractive peoples and communities are particularly affected by the seasonality of crops and low or no value-added inputs, providing income instability for access to essential items. For example, about 51.42% of the population of the State of Amazonas lives in poverty, the second highest poverty rate in Brazil [6], generating an ambiguous scenario where the value of forest maintenance is not perceived, compared to persistent poverty.

Meher [7] sought to analyze whether poverty was a crucial factor in environmental degradation in India and found that the relationship between deforestation and poverty is complex, far from trivial, and requires an in-depth analysis. Considering specific local causes is essential for planning and reversing forest degradation since the mechanisms and links are unclear. A lack of understanding of the relationship between forests and poverty makes formulating policy strategies and efficiently allocating resources difficult [8]. Efforts to understand this complexity have also been carried out in research in Malaysia and Indonesia [9] and the Himalayan ranges [10], noting the need for in-depth understanding to formulate more effective strategies.

Environmental problems often have significant links with economic issues and are tolerated because of the negative impact their solution could supposedly have on the economy. This highlights the logic that only prioritizes the short term, neglecting the long-term consequences for the environment, society, and the economy [11]. As long as these activities are profitable in the immediate term, they will continue to reinforce the increase in deforestation [12].

Therefore, this study aims to comprehend (1) what the impact of deforestation on the economic development of communities and peoples is and (2) what the relationships between persistent poverty and social pathologies are.

In the literature, the poverty trap is described as mechanisms present within a system that interact and feed back on themselves, causing poverty to persist structurally [13]. In specific geographic circumstances, such as those of communities and traditional peoples, long-term structural poverty manifests itself due to a lack of opportunities, work capacity, and access to economic assets [14]. In areas where livelihoods depend on the natural capital of forests, poverty is interrelated with biodiversity loss [15].

A typical pattern is the lack of investment in human, physical, and technological capital that provides an environment for innovation [16]. In addition, lack of employable skills training and no effort towards enhancing the cognitive skills of the population [17].

In order to change the current economic model, it is necessary to develop a new paradigm of sustainable development in the region. According to Kuhn [18], a paradigm is a set of concepts or thought patterns, guidelines, and standards. This set of rules and concepts guides research and development, defining how a particular area of knowledge is understood and investigated by a scientific community. Through a process of accumulation of knowledge, it can change over time when discoveries arise that challenge established beliefs.

One paradigmatic alternative is to explore sustainably the economic potentials of bio-based, called bioeconomy [19]. In the Amazon Rainforest, the application of bioeconomy aims to support the economic development of traditional peoples and communities, thus combating deforestation, adding value to biodiversity products, and combining traditional knowledge and high technology.

However, to advance this strategy and transition from the current economic model to a sustainable one, it is necessary to identify the standard behavior of the systems in focus. As Capra [20] states, sustainability is not the property of a single element but rather an emergent property of the web of relationships of the ecosystem’s components. Bringing the need for us to learn from nature in terms of relationships, interconnections, patterns, and context allows for a better understanding of how to achieve sustainability.

Systems thinking contrasts our view of the world as an unlimited environment and each problem as isolated. On the contrary, feedback, time delays, accumulations, and nonlinearities are part of the properties of complex systems [21]. Moreover, in complex systems, these properties occur together and interact, causing nonlinear behavior patterns.

To understand whether the current structure manifests a pathological system trapped in reinforcing the unsustainable use of the Amazon Forest, we adopt a systems view, capturing the system’s structure with its environmental, social, economic, and cultural interactions.

Systems approaches enable in-depth analysis and understanding of the relationships between deforestation and poverty through participatory modeling, making it possible to organize collective knowledge [22,23]. Using a system dynamics approach with causal analysis makes it possible to explore the system’s structure and understand its dynamics and interrelationships. This approach increases rigor and effectiveness in creating interventions to establish new paths [10,22,23]. For sustainability is a growing field with ever-increasing challenges and complexities [24].

Therefore, the aim of this research is to map the dynamics of the current structure and identify the interconnections between environmental degradation, economic development of indigenous peoples and traditional communities, and the mechanisms that contribute to the perpetuation of poverty and social pathologies.

Here, we offer three contributions. First, an approach that effectively engages forest-dependent stakeholders by understanding their needs and values. Significant system elements, such as cultural values and assumptions, which are typically excluded in strategy-making, are considered [11,25]. Second, we recognize the significance of maintaining ecological balance at a systemic level, the research adopts a holistic perspective that acknowledges the need to achieve this balance at every level of the system, from the individual to the community, region, and ultimately the global level [26]. This encompasses a comprehensive consideration of the ecological impact and interdependencies across different scales, contributing to a nuanced understanding of the complex dynamics of the system. Third, we suggest contributions for future planning of systemically feasible and effective interventions.

2. Materials and Methods

The research employs methodological approaches that facilitate adopting a systemic perspective. Utilizing both empirical and conceptual methods, the investigation employs experimental data collection and subsequent analysis of the gathered information. Initially, data was acquired through interviews and subsequently examined, constructing a systemic model concerning pathological dynamics within the Amazon region.

2.1. Methodology Development Process

To structure the research problem, this work implemented a multi-methodological approach using strategic options development and analysis (SODA), a problem structuring method (PSM) [27] and qualitative system dynamics model. The methodology employed by SODA incorporates cognitive maps (CogMap), which enables the cognitive modeling necessary to explore problematic situations.

The current study involved an intervention with individuals and groups that could potentially impact, or be impacted by, the successful achievement of objectives. Such individuals and groups were identified as stakeholders, with requirements for power, legitimacy, and urgency [28]. To gather data, the researchers interviewed individuals representing all Stakeholder groups. Based on these interviews, the researchers organized the information in CogMaps, converting the main ideas shown by the interviewees into constructs and giving them a hierarchical distribution. As stated by Ackermann and Eden [29], feedback loops are not easy for people to identify in their mental models [30]. Using a CogMap to structure the ideas of interviewees helped in identifying conceptual feedback structure. The employment of “automatization” software (Decision Explorer) supported the information of conceptual networks visualizing the dynamics of the system under study.

Based on logical and conceptual feedback, researchers designed and identified causal loop diagrams (CLDs). They then developed qualitative system dynamics models to identify the structure of the system under study, including its components and feedback loops, in order to analyze emergent systemic behavior.

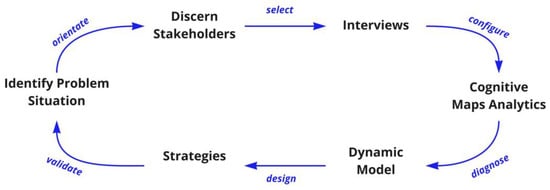

The relationships within system structures can potentially generate problematic behavior [31]. In order to identify the structures that exist within the context of this study, the procedures utilized were consistent with the methodological pathway illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Methodological route.

To investigate a challenging scenario that required unrestricted access to the geospatial region of interest, we used the Mapbiomas platform to demarcate the area of interest, with a particular emphasis on the Amazon biome, using the soil cover analysis tool incorporated within the platform (the MapBiomas platform employs remote sensing and satellite technology to map changes in land and vegetation in Brazil, generating detailed maps of deforestation, degradation, agricultural expansion, and urbanization).

In order to provide a broad set of perspectives on the same problems, interviews were conducted with stakeholders who had experienced the situation from different contexts. We had the pleasure of interviewing the following personalities:

- A “Quilombola” (Quilombolas are peoples with African ancestry. They were enslaved and escaped cruelty by taking refuge in the woods. They organize in spaces of resistance and freedom, living integrated with nature) community leader who is part of the national council for the extractive (Extractivism consists of economic activity through forest resources such as collecting seeds, oils, leaves, fruits, among others) population, linked directly and indirectly to 5100 communities.

- An indigenous leadership with territory in the Brazilian Amazon, bordering Colombia and Venezuela. Awarded for promoting social entrepreneurship in his village, establishing commercial relationships in Brazil, and creating an indigenous brand, which fostered the economy and income generation, i.e., action integrated with intercultural education.

- A director of an institute whose mission is to facilitate and support the development of communities and traditional peoples, by diagnosing the potentials and weaknesses of the territory and advice to social enterprises.

- A specialist in the sustainability of production chains in the Amazon, the Amazonian Genome, and the Internet of the Future.

These interviews were conducted remotely, using an online meeting platform, and were carried out individually to ensure that each interviewee could express their experience without influencing others. The interviews were semi-structured, with base questions defined beforehand and the problem explored during the interviews. After conducting the interviews, the transcription process was completed to start the structuring process.

In order to capture and structure the various perspectives gleaned from the interviews, part of the SODA methodology was employed, which was underpinned by the principles of the theory of personal constructs. The SODA maps were structured and developed through the MIRO platform and the “Decision Explorer” software. In addition, CogMaps was used to structure complex situations by creating a map of perceptions, which allowed the interviewees to expand their understanding in a structured way and generate new insights and connections to the problem.

Abuabara [32] stated that individuals have their personal views of beliefs supported by their experiences and acquired knowledge. This study utilized a structure designed for problem-solving interventions that enabled verbal communication to understand the issues at hand comprehensively. By employing the methodologies and tools mentioned, this study was able to capture and structure multiple perspectives on a problematic scenario, providing a basis for further analyses and insights [33].

In the search for capturing and structuring the multiple perspectives, for the elaboration of aggregate maps and analyses, part of the SODA methodology was used, and its emphasis was supported by the principles of the theory of personal constructs [32,33,34]. The process of structuring and creating the SODA maps was carried out using the MIRO platform and the “Decision Explorer” software.

The individual maps of the interviews were structured to establish a hierarchy of concepts to connect ideas and cause-and-effect relationships. Each construct was elaborated with the inclusion of poles of similarity or differences to provide deeper understanding, making the statement more concise [33,35]. Afterward, the SODA maps were validated through individual online meetings.

After validation, the authors elaborated on the corresponding CLDs models. This process was first carried out using the “Decision Explorer” software analysis tool. This tool can automatically detect the presence of feedback in cognitive maps, even in a large and complex collection. It is expected that once a complex collection of constructs has been analyzed using this tool, a massive number of causal loops is identified, which requires the elaboration of a filter for synthesis. According to Schwaninger [36], filtering essential information from the overabundance of data is crucial for the quality of a decision. Ultimately, the decision cannot be better than the underlying model.

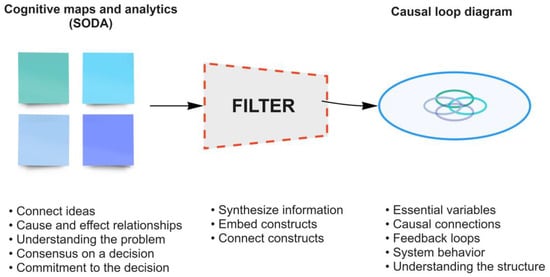

Figure 2 shows a scheme with the CLD construction process. The authors synthesized the information from each interviewee into constructs at a higher level of abstraction, reviewing the final result for cohesion and rigor. By completing the CLD of the first interview, it was possible to obtain a prior understanding of the structure and feedback loops, and interrelationships.

Figure 2.

CLD construction process.

In the same way as this first CLDs structure, similar constructs from the second interview were sought to be incorporated and linked from its original CogMap, and relevant constructs not previously addressed were added, establishing the connections between each interviewee’s ideas. The same procedure was meticulously repeated for the other interviews, with the aim of providing more quality information to the model to identify the behavior of this system. Using as a basis the similar constructs from each interviewee CLD, the authors created an aggregated map, including all feedbacks, hierarchies, and relations observed in individual maps and CLDs.

Aspects such as the solutions addressed by the interviewees, which have provided or will provide improvements, have been included, creating a set of strategic solutions to establish a new behavior of the system.

Complex systems have a multidimensional and interconnected nature, causing the interactions of the parts to affect one another. A small change in the initial state of a complex system can cause results disproportionate to the inputs due to the complex feedback structure. This makes the behavior of a complex system hard or impossible to predict [37], [38] (pp. 78–79).

To gain a comprehensive understanding and effectively plan strategies for constructing the CLDs, we identified the variables, relationships, and emergent properties to obtain a multidimensional view of the system’s problems and challenges. Furthermore, we recognized the recursive nature of the issues at hand, including the local concerns of an indigenous tribe, which are intertwined with the broader problem of the Amazon and the development of the biome. This analysis is in line with the following proposal: “Sustainability can only be achieved, by an ecological balance at each of the various levels, from the individual to the family, to the municipality, to the region, to the province, to the department or to the state, to the nation-state, for the continent, and for the world” (Schwaninger [26]).

After that, the authors analyzed the systemic relationships across three recursive levels in order to promote viability and sustainability, specifically at the community, region/country, and global levels. These levels are defined as follows:

Community: According to the National Policy for the Sustainable Development of Traditional Peoples and Communities (PNPCT), traditional peoples and communities (PCTs) are defined as “culturally differentiated groups that recognize themselves as such, that have their own forms of social organization, that occupy and use territories and natural resources as a condition for their cultural, social, religious, ancestral and economic reproduction, using knowledge, innovations, and practices generated and transmitted by tradition” [39].

Region/country: An area that transcends the territorial boundaries of traditional populations. Impacting and affecting larger limits such a city, state, or country.

World: Refers to the global sphere, not being delimited by borders. The representation of the relationships between the levels makes palpable the nature of the system: what happens at the community level affects the regional/country level and ultimately the world level. What happens at the regional/country level affects the community and world levels. Likewise, the world level affects the community and regional/country levels.

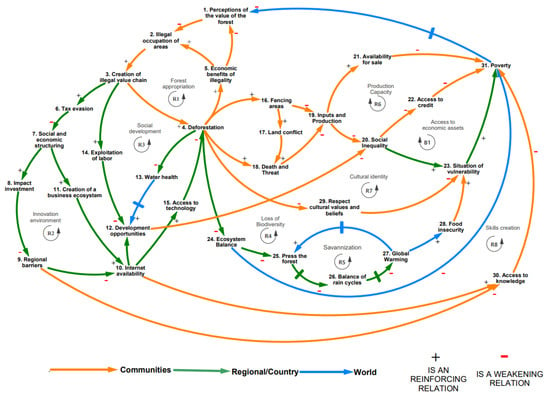

The interactions in the system can entail positive (reinforcement) and negative (balancing) feedback loops. Using the software Decision Explorer (https://banxia.com/dexplore/, accessed on 5 May 2022) 197 causal loops (CL) were found in our CLD. For this research, grouping sequences that explored the concepts more comprehensively were chosen, as shown in Figure 4, created with the software Vensim (https://vensim.com/, accessed on 5 May 2022).

The interactions in the system can entail positive (reinforcement) and negative (balancing) feedback loops. Using the software Decision Explorer, the filtering process produced a parsimonious and more significant CLD model. The authors could extract the basis for the final analyzed model created with the software Vensim.

2.2. Definitions of the Variables Present in the Pathological System

The variable definitions were developed based on the constructs emanating from the CogMaps. The most frequent constructs among the interviews formed the variables and provided a starting point for the ensuing modeling process.

To determine the essential variables of the model, causal relationships between variable pairs were analyzed, and the final CLD was created, where the polarities of the loops were determined.

This process was led by the first author, who presented the proposal to each of the two students—one master and one doctoral—whenever a decision had to be made. The proposals were mutually combined with those of their peers. The goal of this modeling was to present a portrait of the Amazon Forest with the interactions of ecological, social, and economic dimensions, focusing on the level of local and regional communities, as well as identifying systemic pathologies.

In the following, we define the variables that constitute the CLDs in Figure 3 and Figure 4. Some excerpts from the interviews that confirm the description and choice of each chosen variable can be found in Appendix A.

1. Perceptions of the value of the forest: Through perception, the interpretation of the individual originates. Perceptions of the value of the forest impact the interpretations of this environment. Value is much more than material worth. In this context, value is much more on the side of the good, the beautiful, and the life-sustaining. The forest is a treasure in both ideal terms and absolute terms. The shallow perception of the importance of the forest and its economic potential is manifested in certain groups, e.g., land grabbers, illegal miners, animal traffickers, and illegal timber exploiters, leading to guide their actions through practices of exploration and use of unsustainable lands.

2. Illegal occupation of areas: In the Amazon region, the illegal invasion of lands demarcated as complete protection conservation units, sustainable use conservation units, and indigenous lands [40] results in appropriating a collective good. People from other regions occupy these illegal areas, later claiming ownership.

3. Creation of illegal value chain: It is due to the operation and commercialization of illegal activities. When certain groups of people settle illegally in conservation areas, the illegal value chain begins, carrying out activities such as illegal logging, mining, and promoting illicit trade.

4. Deforestation: Human activities of permanent extraction of the forest. It is about the unsustainable exploitation of forest resources, transforming trees into wood for illegal trade. Deforestation entails degradation of local biodiversity degradation, as the ecosystem is disturbed.

5. Economic benefits of illegality: Self-benefits through illegal activities. Gain or advantage obtained economically through illegality. The economic benefits of illegal activities originate through demand, promoting economic interest in these activities.

6. Tax evasion: Carry out illegal actions to avoid paying fees, taxes, and contributions. Illegal activities leave no value at any link in the value chain. When they use illicit maneuvers to legalize illegally extracted wood, they promote processing only at the final link, leaving the other links unstructured.

7. Social and economic structuring: Establishes the relationship between society and the individual. It provides an environment with greater social equality. The Amazon region has a very weak social and economic infrastructure that promotes precarious public institutions with extreme dependence on federal government funds.

8. Impact investment: Investments to generate social or environmental improvements. Encourage improvements that change the current limited development scenario, promoting conditions for a sustainable economy with greater productivity and added value.

9. Regional barriers: Difficulties and obstacles to regional development. Due to geographic characteristics, there are demands for innovative solutions that overcome the barriers of logistics, communication, connectivity, and the adoption of technologies.

10. Internet availability: Wide and comprehensive network connection access enables instant data sharing. The absence, in the Amazon, of the internet broadly and comprehensively leads to disconnection and isolation of traditional communities and peoples.

11. Creation of a business ecosystem: Promoting entrepreneurship by creating or renewing business. When access to entrepreneurship is restricted, the population is deprived of an important economic engine. Not providing this access means that the emergence of innovation, from the sustainable use of regional biodiversity is blocked.

12. Development opportunities: Timely circumstances for personal development. Opportunity for improving the current socio-economic state of the community and its members. Currently, the extremely low level of opportunities at the Amazon limits people’s development.

13. Water health: Water quality. Free from contamination that could affect health and cause illness. Water pollution in the Amazon is due to the use of chemical products, improper disposal, and ore dumps. The contaminants reach the seas and pollute the oceans.

14. Exploitation of labor: Related to a disproportion between work and remuneration. In The Amazon, it is mostly manifested by a grossly inequitable economic return and working conditions similar to slavery and child labor.

15. Access to technology: Restrict access to defined areas. Implement local barriers with electrified fencing to prevent access to illegally invaded preservation areas.

16. Fencing areas: Restrict access to defined areas. Implementation of local barriers with electrified fencing to prevent access to illegally invaded preservation areas.

17. Land conflict: Situation generated by the land tenure dispute. This conflict is generated when there are invasions of lands already demarcated as indigenous and quilombola territories and reinforced in this case when communities do not have land titles.

18. Death and Threat: Intimidation by words, gestures, or means, often resulting in loss of life. The Amazon is the center of the highest number of murders in rural conflicts. When land invasions occur, traditional communities and peoples are constantly under threat.

19. Inputs and Production: Inputs are elements, such as seeds, oils, and labor, used to produce goods. The quantity and availability of products for the communities are linked to the size of the areas available for extractives.

20. Social Inequality: Unequal access to benefits for different members or groups in a society. In the Amazon, the quality of life is impaired, given the injustice and lack of access to essential items.

21. Availability for sale: Supply guarantee and product items for sale. In the case of communities and traditional peoples, availability for sale is related to seeds, oils, fruits, and other inputs. It is necessary to ensure adequate supply in terms of quantity and quality, as savings depend exclusively on the sale of these products.

22. Access to credit: Possibility to access loans and monetary investment. For people in traditional communities, it is very difficult to obtain credits to finance their ideas and projects.

23. Situation of vulnerability: Vulnerability can have physical and psychological aspects. It can be related to the individual’s condition or property.

24. Ecosystem balance: State of interaction that emerges from the balance of the components of the ecosystem. That balance is existential and essential to warrant “ecosystem services.” Intact ecosystems are indispensable for maintaining life on Earth.

25. Press the forest: Disrupting existing ecosystems, compromising their functioning. The pressure on the Amazon Forest is due to the fragmentation of its biome, harming biodiversity.

26. Balance of rain cycles: The water cycles enable the survival of living beings on Earth. In the Amazon rainforest, this balance transcends regional importance, reaching global importance.

27. Global warming: Change in temperature and climate pattern, increasing above average. Deforestation causes the release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, which promotes global warming.

28. Food insecurity: The influence on the availability and access to food. Food insecurity within the forest happens when there is a critical reduction in the amount of food available. Across recursion levels, food insecurity may escalate globally.

29. Respect cultural values and beliefs: Respect the diversity of cultures. Cherishing the relationship of the community with the forest, treasuring customs, and ancient traditions.

30. Access to knowledge: Obtaining cognitive competencies through various means, such as attending schools, workshops, seminars, and other educational programs, is crucial for the overall development of an individual.

31. Poverty: According to Amartya Sen [41], “Poverty is not just a lack of money; it is not being able to realize the full potential of a human being. Poverty leads to an intolerable waste of talents.”

3. Results and Discussion

“People come from other regions, look at the Amazon Forest, our state, our municipality, our quilombos and think that it has no value; they are poor in conscience.”—Quilombola leader

It is necessary to replace the current reductionist view with an organic, interconnected, and dynamic one to draw reasonable conclusions about the workings of organizations and the outcomes of interventions in this system. Overlooking or ignoring a system’s multidimensionality and multi-level arrangement does not alter its intrinsic traits. Instead, it renders any attempts to make meaningful and long-lasting contributions to the system systematically impractical.

It is impossible to predict the behavior of an entire system, a natural or social one, based only on its parts and the emergent properties exhibited. However, this unpredictability is governed by a certain degree of order, which conveys the movement of the real system [37].

The CLD in Figure 3 presents an overview of the dynamic structure of the system under study. This modeling is aimed to present the main interactions in the ecological, social, economic, and cultural dimensions, as well as the three recursive levels and the systemic pathologies that should be identified. In the diagram, the arrows represent the cause-and-effect relationships. Relationship at the community level are in yellow, regional/national in green, and worldwide in blue. The relationships on the higher levels (green and blue) normally also apply to the lower level (yellow, green). The direction of causality is marked by symbols (+) and (−).

Figure 3.

Overview of the pathological system in the Amazon.

3.1. Causal Loop Diagram: Cause and Effect Relationships

In the following, the CLD in Figure 4 will be explained with the necessary detail. We start with the following cause variable: “(1) Perceptions of the value of the forest,” which causes an effect variable; “(2) illegal occupation of areas.” The relationship between the two has a “−“ polarity, i.e., the opposite: When (1) increases, (2) decreases; when (1) decreases, (2) increases.

Problems due to a misguided perception of the value of the rainforest have been present since the colonization period in Brazil. The colonialists considered the Brazilian territory to be of little value and freely available for unlimited exploration. This mindset prevails in part of the country and among specific segments of the population until today.

Despite well-defined territorial classifications in the Amazon, there are many gaps in the current legislation, leaving room for the seizure of land titles, with legal uncertainty prevailing.

A pejorative attitude towards the value of the forest, by the individual or society, promotes the use of land based on an economic logic favoring the unsustainable exploitation of the forest, an economic model that has prevailed since the period of colonization. It leads to an increase in demand and the illegal occupation of land, feeding a complex system of pathologies.

Nine causal loops were selected (Figure 4) to explore in some depth the structure of this system with its causal relationships.

Figure 4.

The dynamics of the pathological system in the Amazon.

The reinforcing causal loop is characterized by an even number of polarized arrows (+), while the balancing loop is characterized by an odd number of polarized arrows (−). In this diagram, 8 (eight) reinforcing loops (+) and 1 (one) balancing loop (−) were explored.

3.1.1. Causal Loop: Appropriation of the Forest (R1)

“One of the biggest problems in the Amazon is land grabbing. They surround a piece of land, deforest and place cattle, to carry out actions and obtain title to that land.”—Institute Director

Forest appropriation is the first reinforcing loop. It consists of the following components: (R1) = 2(+) 3(+) 4(+) 5(+).

When the illegal occupation of areas in the Amazon Forest region occurs, an illegal or informal value chain forms. This formed illegal chain operates through the unsustainable exploitation of the Amazon Forest through deforestation. The process of deforestation takes place in a series of stages. Initially, smaller trees are cut down to prevent detection via satellite imagery. Later, the focus shifts to placing cattle and eliminating larger trees. These illegal practices result in economic gains, further driving the demand for the unlawful occupation of the affected regions.

3.1.2. Causal Loop: Innovation Environment (R2)

“Any chain operated illegally or informally brings a set of social and economic ill structure to the territory.Why value chain? Because it necessarily needs to leave the value in all its links.Every time you operate illegally, for example, in the form of deforestation, you don’t leave any kind of tax value. These municipalities all have weakened political institutions.”—Institute Director

Innovation environment is the second reinforcing loop. It integrates the following concepts: (R2) = 1(−) 2(+) 3(+) 6(−) 7(+) 8(−) 9(−) 10(+) 15(−) 4(−) 24(−) 31(−).

The analysis begins with the variable that gives rise to the entire structure of this system, perceptions of the value of the forest. A pejorative perception of the rainforest is directly related to practices of illegal occupation of territories. Developing more sustainable (mostly in social and economic aspects) perceptions of value would decrease the areas’ illegal occupation. When these areas are illegally occupied, an informal or illegal value chain begins to form.

Through the relationship of these elements, the weakening of local public institutions emerges in the regional dimension since there is no tax collection. The financial support needed to maintain local institutions comes from the national level. The lack of tax collection has a devastating social and economic effect. It jeopardizes the economic viability of municipalities. It prevents investments that can promote improvements, stimulate the creation of effective solutions for systemic pathologies and overcome regional barriers where traditional peoples and communities live.

The lack of internet access brings complications in promoting development in the region. The availability of internet access is essential to create an environment with access to innovation, which will make it possible to reduce extensive deforestation practices regionally.

When operated to contribute with deforestation, the benefits of ecosystem services are lost, and the entire environment becomes vulnerable, transcending regional levels and reaching global importance. In the end, the ecosystem balance is the maintenance of persistent poverty, which will impact the perception of the benefits of the forest.

3.1.3. Causal Loop: Social Development (R3)

“What I can start to say is that there is a fundamental issue in the Amazon; the land issue, that is, if there are no regulations for areas, this causes territorial insecurity, legal insecurity, lack of access to public policies, which are very serious for residents.Another big issue is that people migrate from other regions and fence off a piece of land and take the necessary actions to get title to that land.”—Institute Director

Social development is the third reinforcing loop: R3 = 1(−) 2(+) 3(+) 14 (−) 12(−) 20(+) 23(+) 31(−).

Perceptions of the value of the forest is directly linked to the illegal occupation of areas. An informal or illegal value chain begins to form when these areas are occupied.

When operated illegally or informally, there is the exploitation of workers with conditions analogous to slavery and the exploitation of child labor. Leading to shallow development opportunities, creating a regional environment of many informal jobs. Promoting social inequality will create a situation of vulnerability at the regional level, reinforcing persistent poverty and shaping the perception of the value of the global forest.

3.1.4. Causal Loop: Biodiversity (R4)

“In the year 2000, weighty rainfall flooded the entire community. From that moment on, we began to see an imbalance in the millennial ecological calendar. There started to be many rain showers before the time and in quantities out of the normal, which our people have millenary accompanied.So, sometimes it delays or brings it forward, and this causes problems, like the reproduction of the fish in the rivers.”—Indigenous leader

Biodiversity is the fourth reinforcement loop: R4 = 1(−) 2(+) 3(+) 4(−) 24(−) 31(−).

Problems with perceptions of the value of the forest promotes the growth of occupation in the illegal economic exploitation of areas through deforestation. These elements are present in the system’s structure at the local level, and an impact at the regional level on the ecosystem emerges.

Deforestation increases the pressure on the forest system by disturbing the natural balance achieved through evolution over billions of years. These intrusions impact the equilibrium of the rain cycles, which are fundamental for maintaining life on Earth.

Indigenous communities follow an age-old ecological calendar, but the current environmental instability has disrupted the natural cycles of fish reproduction, flowering, and fruit production in the forest. This, in turn, has affected crop planning and led to unusual behavior among animals who have started to attack the plantations of these communities in search of food. It may also unleash food insecurity, which extends to the global level when the forest stops forming the flying rivers (flying rivers are large, invisible air currents of vapor, fed by moisture from the forest and transported, i.e., flowing over long distances) of the rain cycles (continuous exchange of water presents in the atmosphere, soil, plants, surface water, and groundwater, through processes such as condensation, precipitation, infiltration, transpiration, and evaporation. Water evaporates into vapor, condenses forming clouds, and returns to earth in the form of rain and snow). Finally, generating a situation of vulnerability that reinforced persistent poverty in terms of the lack of perception of the benefits of the forest.

3.1.5. Causal Loop: Savannization (R5)

“One consequence that we have never seen before is the white-lipped peccary (an animal) starting to devour gardens. Our interpretation is that there is a problem with fruit production in the forest. Previously, the peccary had enough food in the forest and did not need to venture into our gardens. Unfortunately, this phenomenon continues to occur in our region without any signs of improvement.”—Indigenous leader

Savannization is the fifth reinforcing loop: R5 = 25(−) 26(−) 27(+).

The savannization process occurs when the forest loses its ability to regenerate due to the impact on climatic, ecological, and environmental dynamics.

The advance of agricultural areas has been intensifying over the forest, causing forest fragmentation. This negatively alters ecological processes such as pollination, nutrient cycling, and carbon storage, influencing tree mortality and decreasing species abundance [42].

These process results in ecosystem deterioration, which increases the pressure on the forest system, followed by impacts in the rain cycle balance that will contribute to the effects of climate change. This will increase the pressure on the forest system, eventually causing its collapse.

3.1.6. Causal Loop: Production Capacity (R6)

“Nobody wants to leave, and when the community does not want to leave, the quilombos do not want to, the extractivists do not want to, the indigenous people do not want to, it results in that, they kill. That is it, we die, but we don’t stop defending because this is our life.So, when that happens, like this lady, many women were afraid to break the coconut, which reduces production, and this reduces our lives.We who are already organized, we don’t stop, but those people who are starting now, they weaken and become unbalanced.”—Quilombola leader

Production capacity is the sixth reinforcing loop: R6 = 1(−) 2(+) 3(+) 4(+) 16(+) 17(+) 18(−) 19(+) 21(−) 31(−).

Misguided perceptions of the value of the forest promote the growth of occupation to exploit areas illegally through deforestation. This implies fencing occupied areas to carry out land grabbing.

By fencing the areas and electrifying the fences, the struggle for the right to land begins. This happens when traditional communities and peoples need land ownership where they live or when the law fails to protect the demarcated territories. Land conflicts result in threats, persecution, and murders of community members. As these crimes escalate, they induce fear among the community members, negatively affecting productivity.

Traditional communities and peoples live of extractivism—the management of natural landscapes from which products are taken without disturbing the natural order. Their economies are largely based on inputs with little or no added value. That economy is already affected throughout the year by the seasonality of the forest due to its cyclical nature. They are even more impacted when there is a land conflict, with the reduction of areas to conduct extractivism.

This reinforces the entry of the persistent poverty element, which contributes to the lack of perception of the benefits of standing forests.

3.1.7. Causal Loop: Access to Economic Assets (B1)

“If we have a better investment, for us to produce better, of course, it improves! For example, here, we pound the coconut in the mortar by hand to remove 01 L of oil, it takes the whole day, but if you had the ‘parrageiro’ you would take 50 L, if you have a crusher, then you would take 1000 L. These are the things we are discussing so that it is a modern thing that does not harm the environment and does not harm our community.What you are talking about, if there were, it would be very rich, because here we work with oil, mesocado, we work with soap, we work with a series of things, with bee honey, andiroba oil, a series of things, with fishing, with babassu, with charcoal. However, I would need support to produce better if I had it...”—Quilombola Leader

In the causal loop access to economic assets is the first balancing loop: B1= 1(−) 2(+) 3(+) 4(+) 13(−) 12(+) 20(−) 22(−) 31(−).

Misguided perceptions of the value of the forest promote occupation growth to economically exploit areas illegally through deforestation, provoking negative regional impacts by affecting insalubrity with risk of water contamination. When the contamination of the rivers will reach the seas with a delay of time, it will promote the risk of contamination of the waters at a global level.

The reduction of opportunities will be felt at the level of individuals in communities. The risk of water contamination can cause disease and even hinder the development of entrepreneurship because there are possibilities to affect the products from the communities. This reinforces social inequality, which makes access to credit difficult and prevents entrepreneurship from growing in the region. Reinforcing persistent poverty and the perception of the benefits of the forest.

3.1.8. Causal Loop: Cultural Identity (R7)

“So, when you ask me what the impact is, the impact is very strong. If you tell this to the elderly, who keep this knowledge, they cry as if they had lost a relative.The impact on the memory of the reading he does, that’s why he was crying, is the prophecies of the indigenous people. The indigenous also have their prophecies regardless of religion.So, the impact is very strong, I am talking about this deeper part of our relationship with forests.”—Indigenous leader

Cultural identity is the seventh reinforcing loop: R7 = 1(−) 2(+) 3(+) 4(−) 29(−) 23(+) 31(−).

Like the other loops, this one starts with perceptions of the value of the forest, increased illegal occupation and increased deforestation. They influence a deep relationship that traditional peoples and communities have with the forest, where they have strong ties of identity and cultural values.

Traditional peoples and communities see the forest as an extension of their own identity, and their prophecies are related to the balance of the forest.

Having their cultural identity, customs and beliefs disrespected, due to the impact of deforestation, the expulsion from their lands, and the loss of leadership, reinforces the regional vulnerability of the community. This strengthens the persistent poverty element, reinforcing persistent poverty and the perception of forest benefits.

3.1.9. Causal Loop Diagram: Competency Creation (R8)

“In the past, we only knew how to break the coconut with an axe. Not today, today we already know how to extract the oil to sell, we already know how to extract the oil, we already know how to make soap…, We know how to do a lot of things that we didn’t know, so it changed a lot with the training, with the workshops, the seminars, the congresses that we participate with women, men and youth, we enrich with knowledge, in education.”“We work here with a network (internet) from a project directly in the United States, but it is only in 01 community, in this community that has this network, precisely the community where I live that has internet, but we have more than 70 communities that depend here.”—Quilombola Leader

Creation of competencies is the eigth reinforcing loop: R8 = 1(−) 2(+) 3(+) 6(−) 7(+) 11(+) 10(+) 30(−) 31(−).

The variables involving the perceived value of the forest, the increase in illegal occupation, and the creation of the illegal value chain result in tax evasion. This directly impacts the regional social and economic degradation, creating an inappropriate environment for the creation of a business ecosystem. The business ecosystem is an important economic engine, through which innovation is enabled to emerge and connectivity between people via the internet is increasingly widespread.

Due to their geography and the fact that they live in the forest interior, traditional communities, and peoples have very limited or mostly non-existent access to the internet. By restricting access to the internet comprehensively, access to knowledge is blocked. By restricting knowledge opportunities, the dynamics of persistent poverty are strengthened.

By mapping the relationships, it became possible to identify elements that reinforce persistent poverty, as searched by authors: Innovation environment [16], biodiversity [15], competence creations [17], work capacity, and access to economic assets [14]. However, it was also possible to identify, in the pathology of this system, other mechanisms that reinforce persistent poverty, such as the appropriation of the forest, deficiency of public policies for social development, respect for cultural identity and “savannization.”

Our general diagnostic emanates from looking at the qualitative model as a whole. It contains eight reinforcing loops and only one balancing loop. This shows at once that the system under study is out of balance. Therefore, we will develop suggestions for strategies that could reestablish an equilibrium of viability and sustainability.

3.2. Insights for Pathbreaking Strategies

“So, we started working on the issue of school, generation of income, strengthening of culture, identity.We are talking about social entrepreneurship, we are also talking about education, generation of income, cultural heritage and bringing higher income to communities. In the year 2000 we launched the first indigenous brand, we started to have a business relationship in Brazil.”—Indigenous leader

“Adding value through industry 4.0. As an example, chocolate through the processing of cocoa, will generate an even greater added value in economic comparison, pasture.”—Specialist

“So, there is a lack of support in terms of logistics, technical assistance, management so that it is sustainable, the community lacks credit to implement the project, there is a lack of project management, there is a lack of a series of structures that make it easier to cut down the forest, sell the forest, but easy and short-term.”—Institute Director

In this section, we will build on the diagnostic formulated until now. This is a tentative approach to developing suggestions for the strategies that reinforce the positive dynamics and escape pathologies in the ecological, social, economic, cultural systems of the Amazon. We are proposing a set of strategies, which—in their totality—might be called “pathbreaking,” in the sense that a new paradigm can be brought about, and a new avenue is opened (other authors have used the attribute “disruptive” to denote the same transformative process [43]; to avoid wrong connotations, we refrain from using that term, as our article is dealing with systemic restoration). The solutions proposed in this research are grounded in the thorough diagnosis and data collected from the interviews. These solutions are approached from two distinct perspectives. Firstly, they reflect the practical experiences shared by the interviewees, such as the transformative impact of internet access and knowledge on specific communities. These practical examples highlight the potential of these factors as catalysts for positive change. Secondly, the research suggests potential strategic solutions to address the identified issues and contribute to sustainable outcomes. By combining real-world experiences with conceptual strategic approaches, this research aims to provide comprehensive and practically valuable recommendations for addressing the challenges.

Qualitative system dynamics analysis with CLD modeling is a useful means to describe the feedback dynamics of a social system. To study the behavioral responses of such a system and understand the numerical impact of each effect change, quantitate modeling and simulation is necessary [44]. In this work, we made an effort to gather evidence of the structures inherent in Amazon native populations and their environments. Future research should go beyond, using quantitative modeling and simulation. In the interviews, all respondents clearly address the fundamental need for internet access. When connectivity broadly and comprehensively is enabled, it will be possible to implement groundbreaking solutions. We present a set of seven strategies. This is tentative and without any claim for completeness. We start with the most urgent issue:

- Ecological economy: Also called bioeconomy, it is built on the principles of sustainability. The United Nations’ World Commission on Environment and Development defined sustainability as a path of human activity that meets “the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” [45]. In terms of the Amazon the issues are (a) gratefulness for the forest and nature in general; this implies respect and appreciation of the forest as a gift, (b) protection of the forest, (c) stopping illegal and disruptive intrusions, such as deforestation, (d) building a way of economic and business activities that work in favor of ecological balance and make intelligent use of resources: bio-factories, organic products, circular processes, avoidance of non-degradable waste, etc. To bring about these innovations, motivation is key, intrinsic motivation being more effective than extrinsic motivation. Entrepreneurship should be fostered vigorously.

We will highlight these issues further in the following items.

- 2.

- Smart industry: Developing industries in the forests requires careful planning and rigorous implementation. Advanced industrial systems and practices including intelligent production, waste management, and process optimization are feasible. A circular economy in the sense of a bioeconomy is needed and can be realized. Developing and implementing adaptive technologies will be crucial. These technologies are adapted to local circumstances, are usually small-scale, robust, work with local materials, and do no harm (no side effects). Encouraging entrepreneurship and innovation is essential.

- 3.

- Stop deforestation: Using technology, monitoring the use of land cover through sensors in the forests, and using drones. Combining technology with the “Internet of Things.” Correlating information and tracing history and trends. Through genetic sequencing of plants, trees, and others, it is possible to map the genomic characteristics of the species, to determine the origin and make comparisons, helping to monitor illegal logging. Even more important, new strategies of implementing these controls need to be developed. As an example, the Amazon Biobank (This database utilizes blockchain for transparent recording of genomic data transactions, smart contracts for establishing an internal monetary system, and peer-to-peer solutions for collaboration among users in DNA file storage and distribution) that seeks to integrate emerging technologies to promote the equitable sharing of economic benefits among participants and guarantee the traceability and auditability of genomic data [46]. Finally, new ways of motivating agents for an ecological development of the forest, instead of its destruction, need to be found.

- 4.

- Valuing traditions: Valuing the forest as the classic partner of humanity and the cradle of prosperity. Cultivating traditions (knowledge, customs, practices) and maintain ancient knowledge. This strategy needs to involve educational and socio-ecological institutions.

- 5.

- Safe environment: Enabling communication and sharing of information to prevent and counter violations of rights and social peace. Allowing information privacy and the creation of collaboration channels. Preserving the genetic and cultural heritage by synthesizing a genetic database of species. As an example, Kimura et al. [46] propose a community-based genetic database called the Amazon Biobank, already mentioned above.

- 6.

- Building skills and competencies: Promoting knowledge, from basic to more advanced education and continuous professional training, financial education, research, etc. On a higher level, competencies involve the joint use of hard (technical) and soft (human-oriented) skills.

- 7.

- Increase information and communication effectiveness: Ensure connectivity, giving everybody access to the internet and phones. Facilitate all administrative processes via the platform, for example enabling certification processes. Generally, reduce bureaucracy through innovative communication and information design.

- 8.

- Foster cooperation: Forming cooperative networks will be an essential strategy to bring the ecological economy and the smart industry to flourish. It also enhances synergy. Fostering cooperation is more than making technical devices available. Participant agents need a view of the advantages of cooperation. And they should get some help for taking off, for example the provision of organizational and legal knowledge for the creation of venues and vehicles for cooperation.

The sustainable development of the Amazon can change the dynamics of development. Such development is much more than stopping deforestation. It implies both a different attitude towards the forest and measures of protection. It requires a new way of doing business, in an ecological economy, but reverting to the blessings of enabling technologies. It calls for cooperation among the stakeholders. This is based on a respect and valuation of traditions. Such a development opens a new perspective: The persistent poverty can be relieved and hopefully abolished. An improvement of the quality of life, for people, and the full prosperity of the rainforest dan be achieved, in the long run.

In principle, the healing process outlined can propagate itself along different recursive levels from community to region to continent to world. This can become reality if the manifest complexity is confronted at all of these levels with pertinent systemic strategies.

4. Conclusions

We have elicited the feedback relationships between unsustainable practices that promote the degradation of land cover and the economic vulnerability of traditional peoples and communities and their consequences. A mapping of the current structure manifests the behavior of a system with pathological dynamics that generates pitfalls, reinforcing the unsustainable trend of the Amazon Forest.

The traps involving innovation environment, biodiversity, capacity building, work capacity, access to economic assets, social development, cultural identity, access to knowledge, savannization, and forest appropriation were detected during the research. All of them are linked to a main origin of causal chains in the structure of this system, the “Perception of the value of the forest.” When we think systemically and understand how the environment we live in is globally interconnected, we see that all problems are different facets of a crisis of origin, which is the crisis of perception [20].

Once standard answers will not solve structural pathologies, it is crucial to change the problem-generating structures and seek to establish a new system. All nine loops we have analyzed, with their different ramifications, show a pattern of an extant relationship between persistent poverty and the perception of the value of the forest.

Changing the perception of the value of the forest will only be possible if the pertinent patterns are understood in the first place. The bioeconomy of the forest, emphasizing the importance of maintaining the forest for the prosperity of humanity, the cultural appreciation, and the enormous economic potential of biodiversity, show the way to possible sustainable solutions.

Pathbreaking strategies should open new avenues for the Amazon. We have proposed solutions such as ecological economy, stopping deforestation, valuing tradition, safe environment, building skills and competencies, increasing information and communication effectiveness, and fostering cooperation.

As formulated at the outset, we sought to understand the impact of deforestation on economic and social development including the existing mechanisms in the current structure that reinforce persistent poverty and ecological degradation. We have shown that traditional economic development models produce and feed traps. If we transpose these insights to a global perspective, we find that the current mode of “development” is incapable of ensuring global prosperity and guaranteeing the viability of humanity in the future. To effectively develop a sustainable economy in the Amazon rainforest, it will be necessary to establish a new dynamic for the system.

To overcome the research problem and advance towards sustainable development, the authors recommend the adoption of a systemic approach that promotes reconnection with nature, acknowledging the interdependence between natural and human systems, as well as the significant impact of human actions on the environment. It is imperative to comprehend the intricate relationships of the ecological dimension, which includes ecosystems, biodiversity, and biogeochemical cycles, all of them crucial for the sustainability of the planet, with the economic, social, and cultural dimension.

5. Limitations and Future Research

The study offers valuable insights but has some significant limitations. The first is the restricted geographical focus on the Amazon forest region and traditional peoples and communities, which may compromise the generalization of results to other areas and contexts. It is essential to consider the diversity of realities in different regions of the world. In addition, the proposed solutions must be empirically validated through practical implementation tests to understand their feasibility and tangible impact in practice. Small-scale experiments are a good start for such tests.

In complementing and continuing this research, a promising approach to consider is modeling and simulation. The qualitative models could be used as conceptual tools in building quantitative simulation models. Then, strategies for the attainment of the solutions proposed in this contribution could be tested and developed further, by means of dynamic simulation. Furthermore, it is suggested to analyze the trap loops separately, since in the generalization in our qualitative modeling, some important aspects might have been disregarded. Finally, the importance of developing sustainable educational measures, and strengthening their role in the implementation of the proposed solutions, cannot be sufficiently emphasized. These issues are top priority and therefore must exceed what we have been able to do in this article.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M.; Methodology, R.M., M.S., A.L. and M.C.N.B.; Validation, R.M., Y.L., T.C.M.B.C. and R.C.S.; Formal analysis, R.M.; Investigation, R.M., A.L., Y.L. and T.C.M.B.C.; Writing—original draft, R.M., A.L. and Y.L.; Writing—review & editing, M.S., M.C.N.B., T.C.M.B.C. and R.C.S.; Supervision, M.S.; Project administration, R.M. and M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by FAPESP Research Project 2018/23097-3 and this study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)–Finance Code 001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Amazonia 4.0 Institute, specially Ismael Nobre and Carlos Nobre, Terroá Institute, OCAA organizations (Observatório de Comércio e Ambiente na Amazônia), to the Baniwa peoples and quilombola extractivists for supporting our work. For initial support to the research, we would like to thank Rafael Françozo of the IFMS (Instituto Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Excerpts from the interviews.

Table A1.

Excerpts from the interviews.

| Variable | Excerpts from Examples |

|---|---|

| 1. Perceptions of the value of the forest | “People come from other regions, look at the Amazon Forest, our state, our municipality, our quilombos and think that it has no value; they are poor in conscience” (Quilombola leader). A:“Several people come from other states to use that land. However, they only knew the value of livestock and soybeans and were unaware of the immense value of nature in that region” (Institute Director). |

| 2. Illegal occupation of areas | “One of the biggest problems in the Amazon is land grabbing. They surround a piece of land, deforest and place cattle, to carry out actions and obtain title to that land” (Institute Director). |

| 3. Creation of illegal value chain | “Any chain operated illegally or informally brings a set of social and economic ill structure to the territory” (Institute Director). |

| 4. Deforestation | A:“A set of socio-environmental wealth, including socio-biodiversity, is extracted from that location. This doesn’t generate labor, fiscal, or ecosystem service benefits, as the extraction affects carbon, fauna, and biodiversity services from the area. This creates a cycle of precariousness and social informality in these territories” (Institute Director). |

| 5. Economic benefits of illegality | A:“The reckless economic exploitation of Amazon territory, driven by the pressure to utilize the land, has resulted in haphazard and unsustainable practices that prioritize rapid profits through deforestation and forest product sales” (Institute Director). |

| 6. Tax evasion | A: “Another thing, every time someone operates illegally, for example, through deforestation, they leave no type of tax value, no fiscal value, thus creating a loop” (Institute Director). |

| 7. Social and economic structuring | “Every time you operate illegally, for example, in the form of deforestation, you don’t leave any kind of tax value. These municipalities all have weakened political institutions” (Institute Director). |

| 8. Impact investment | A:“The illegal activities do not generate taxes that could be used to implement public policies that would benefit the entire structure and help communities organize and set up community enterprises in the bioeconomy chain. Promoting these structures allows the chain to be organized more fairly, with all links well-structured and supporting policies” (Institute Director). |

| 9. Regional barriers | A:“Furthermore, the community faces challenges in accessing credit for implementing projects, establishing effective management, and developing essential structures for fostering sustainable business, including addressing infrastructure and logistical difficulties” (Institute Director). |

| 10. Internet availability | “We work here with a network (internet) from a project directly in the United States, but it is only in 01 community, in this community that has this network, precisely the community where I live that has internet, but we have more than 70 communities that depend here” (Quilombola leader). |

| 11. Creation of a business ecosystem | A:“However, the return on sustainable management takes time and requires an entire business ecosystem, including customers and access to communication channels, whether they are public or private. Therefore, the producer cannot just be a producer; they must set up a more complex business structure” (Institute Director). |

| 12. Development opportunities | A:“I’m going to talk about my municipality. We still have 150 communities without piped water and 160 with dirt roads impassable by motorcycles or cars during the rainy season. Additionally, we have 70 communities with schools built with thatched roofs and mud walls, without any direct investment” (Quilombola leader). |

| 13. Water health | A:“For example, in a territory with unsustainable land use, there is a natural increase in climate risks, water security risks, quality and contamination risks, which can alter food security issues” (Institute Director). |

| 14. Exploitation of labor | A:“From the moment the value chain is operated illegally, labor is exploited. These workers have no registration and are economically exploited in work conditions analogous to slavery, often with the exploitation of child labor” (Institute Director). |

| 15. Access to technology | “We work here with one internet network, and there are 70 communities that depend on and need to come here to access it” (Quilombola leader). A:“If we had more access, we could communicate with the entire world. It would be crucial for us, as we have many problems with land invasions and threats” (Quilombola leader). |

| 16. Fencing areas | A:“When there’s an invasion, they surround the areas and install electric fences. When the coconut breakers need to collect the babassu, they risk themselves by passing through these electric fences” (Quilombola leader). |

| 17. Land conflict | A:“I think the conflict issue is the major impact for us here. It means farmers from other states and regions come to settle here amid quilombola regions and environmental preservation areas, in fields and forests” (Quilombola leader). |

| 18. Death and threat | “Nobody wants to leave, and when the community doesn’t want to leave, the quilombos don’t want to, the extractivist don’t want to, the indigenous people don’t want to, it results in that, they kill. That’s it, we die, but we don’t stop defending because this is our life” (Quilombola leader). |

| 19. Inputs and production | “If we have a better investment, for us to produce better, of course, it improves! For example, here, we pound the coconut in the mortar by hand to remove 01 L of oil, it takes the whole day, but if you had the ‘parrageiro,’ you would take 50 L. If you have a crusher, then you would take 1000 L. These are the things we are discussing so that it is a modern thing that does not harm the environment and does not harm our community” (Quilombola leader). |

| 20. Social inequality | A:“This means that he is a killer of nature, so everything he sees in life he wants to destroy. He doesn’t live here, doesn’t reside here, and comes here bringing very strong impacts;” (Quilombola leader). |

| 21. Availability for sale | A:“So, when that happens, like this lady, many women are afraid to break the coconut, which reduces production, and this reduces our lives. We who are already organized don’t stop, but those people who are starting now weaken and become unbalanced” (Quilombola leader). |

| 22. Access to credit | A:“For example, the coconut breakers have to carry the coconuts on their heads, there are no carts to bring them from the forest, everything is still manually carried, and we rarely have access to credit to improve our production” (Quilombola leader). |

| 23. Situation of vulnerability | A:“In my municipality, there are still communities without access to piped water and basic sanitation. Schools are made of thatch and mud, and there are no direct investments here” (Quilombola leader). |

| 24. Ecosystem balance | “In the year 2000, a weighty rainfall flooded the entire community. From that moment on, we began to see an imbalance in the millennial ecological calendar. There started to be many rain showers before the time and in quantities out of the normal, which our people have millenary accompanied. So, sometimes it delays or brings it forward, and this causes problems, like the reproduction of the fish in the rivers” (Indigenous leader). |

| 25. Press the forest | “One consequence that we have never seen before is the white-lipped peccary (an animal) starting to devour gardens. Our interpretation is that there is a problem with fruit production in the forest. Previously, the peccary had enough food in the forest and did not need to venture into our gardens. Unfortunately, this phenomenon continues to occur in our region without any signs of improvement.” (Indigenous leader). |

| 26. Balance of rain cycles | There started to be many showers of rain before the time and in quantities out of the normal, which our people have millenary accompanied” (Indigenous leader). |

| 27. Global Warming | A:“For example, in a territory where there is unsustainable land use, climate risks naturally increase.” (Institute Director). |

| 28. Food insecurity | A:“Losing crops due to floods has frequently been happening, as well as animals starting to attack our crops” (Indigenous leader). |

| 29. Respect cultural values and beliefs | “So, when you ask me what the impact is, the impact is powerful. If you tell this to older people, who keep this knowledge, they cry as if they had lost a relative. The impact on the memory of the reading he does, that’s why he was crying, is the prophecies of the indigenous people. The Indigenous also have their prophecies regardless of religion. So, the impact is powerful; I am talking about this deeper part of our relationship with forests” (Indigenous leader). |

| 30. Access to knowledge | “In the past, we only knew how to break the coconut with an axe. Not today, today we already know how to extract the oil to sell, we already know how to extract the oil, we already know how to make soap, soap, mesocado, we know how to do a lot of things that we didn’t know, so it changed a lot with the training, with the workshops, the seminars, the congresses that we participate with women, men, and youth, we enrich with knowledge, in education” (Quilombola leader). |

| 31. Poverty | A:“Until this happens, for those who live off the land, fight for life, for the forest, for water and the world’s population, deaths, diseases, and problems will not stop” (Quilombola leader). |

References

- Fellows, M.; Alencar, A.; Bandeira, M.; Castro, I.; Guyot, C. Amazônia em Chamas: Desmatamento e Fogo nas Terras Indígenas. 2021. Available online: https://ipam.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Amazo%CC%82nia-em-Chamas-6-TIs-na-Amazo%CC%82nia.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2022).

- Villén-Pérez, S.; Anaya-Valenzuela, L.; Conrado da Cruz, D.; Fearnside, P.M. Mining threatens isolated indigenous peoples in the Brazilian Amazon. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2022, 72, 102398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rorato, A.C.; Picoli, M.C.A.; Verstegen, J.A.; Camara, G.; Gilney, F.; Bezerra, S.; Escada, M.I.S. Environmental Threats over Amazonian Indigenous Lands. Land 2021, 10, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, D. O Povo Brasileiro: A Formação e o Sentido do Brasil; Global Publishers: São Paulo, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Margulis, S. Causas Econômicas do Desmatamento da Amazônia. Banco Mundial. 2003. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1439179105000435 (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Neri, M. Mapa da Nova Pobreza; FGV Social: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2022; Volume 40, Available online: https://cps.fgv.br/MapaNovaPobreza (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Meher, S. Does poverty cause forest degradation? Evidence from a poor state in India. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 1684–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.H.; MacLeod, K.; Ahlroth, S.; Onder, S.; Perge, E.; Shyamsundar, P.; Rana, P.; Garside, R.; Kristjanson, P.; McKinnon, M.C.; et al. A systematic map of evidence on the contribution of forests to poverty alleviation. Environ. Evid. 2019, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, M. Poverty reduction saves forests sustainably: Lessons for deforestation policies. World Dev. 2020, 127, 104746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Schmidt-Vogt, D.; De Alban, J.D.T.; Lim, C.L.; Webb, E.L. Drivers and mechanisms of forest change in the Himalayas. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2021, 68, 102244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, W.W. Global dilemmas and the plausibility of whole-system change. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 1995, 49, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Gaviria, J.; Suarez, C.F.; Marrero-Trujillo, V.; Camilo Ochoa, J.P.; Villegas-Palacio, C.; Arango-Aramburo, S. Drivers and effects of deforestation in Colombia: A systems thinking approach. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2021, 21, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkire, S.; Foster, J. Understandings and misunderstandings of multidimensional poverty measurement. J. Econ. Inequal. 2011, 9, 289–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E.B.; Hochard, J.P. Poverty-Environment Traps. Environmental and Resource Economics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 74, ISBN 0123456789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, C.B.; Travis, A.J.; Dasgupta, P. On biodiversity conservation and poverty traps. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 13907–13912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azariadis, C.; Stachurski, J. Chapter 5 Poverty Traps. Handb. Econ. Growth 2005, 1, 295–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messinis, G.; Ahmed, A.D. Innovation, Technology Diffusion and Poverty Traps: The Role of Valuable Skills; Working Paper; Victoria University: Melbourne, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, T.S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bugge, M.M.; Hansen, T.; Klitkou, A. What is the bioeconomy? A review of the literature. Sustainability 2016, 8, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capra, F. The new facts of life: Connecting the dots on food, health, and the environment. Public Libr. Q. 2009, 28, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, M.P.; Turner, R.E. Sustainability Science: The Emerging Paradigm and the Urban Environment; Springer: New York, NY, USA; Dordrecht, The Netherlands; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; London, UK, 2012; ISBN 9781461431886. [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge, E.; Rancourt, M.; Langley, A.; Dani, H. Expanding Perspectives on the Poverty Trap for Smallholder Farmers in Tanzania: The Role of Rural Input Supply Chains. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Martín, E.; Giordano, R.; Pagano, A.; van der Keur, P.; Máñez Costa, M. Using a system thinking approach to assess the contribution of nature based solutions to sustainable development goals. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 738, 139693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, I.; Gastaldi, M.; Morone, P.; Rosa, P.; Sassanelli, C.; Settembre-blundo, D.; Shen, Y. Bioeconomy of Sustainability: Drivers, Opportunities and Policy Implications. Sustainability 2022, 14, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]