Abstract

Past research on English-medium instruction (EMI) has primarily focused on language-related challenges with scant attention paid to how language is entangled with epistemic access and epistemic injustice. Informed by the perspective of “epistemic (in)justice”, this study focused on how a cohort of students from diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds negotiate a more epistemologically effective and equal access to knowledge negotiation in an EMI international relations master’s program in a Chinese university. Data were drawn from classroom observation, semi-structured interviews, and students’ reflexive journals. Qualitative thematic analysis of the data revealed unequal power relations in students’ epistemic participation and their resulting epistemic silence in classroom discussions. By illustrating how students cope with the epistemic challenges by drawing on individual-cognitive and social-cognitive resources, the findings suggest potential strategies for transnational students to counter the hegemony of English in EMI learning contexts. Implications for decoloniality in EMI education are discussed.

1. Introduction

In higher education, English is promoted as the academic lingua franca [1,2], and English-medium instruction (EMI) programs have proliferated across the globe. In Europe, many universities situated in non-English speaking countries have incorporated EMI courses as a means to appeal to international students and to enrich the global outlook of their own students. The Netherlands, for instance, has emerged as a front-runner in the establishment of EMI courses, with a plethora of universities offering an extensive range of courses that are instructed in English. Comparable initiatives have been undertaken by other nations such as Germany, Sweden, and Norway to varying extents. In Africa, EMI programs have been introduced in several tertiary institutions, particularly in fields such as business and science, where English is regarded as a vital language for cross-border communication. In Asia, EMI is viewed as a method to increase universities’ standing in global university rankings as well as to attract international students and their attendant monetary benefits [3,4]. In 2001, the Chinese Ministry of Education (MoE) called for EMI programs to be introduced among top universities (5–10% of all universities) [5]. The implementation of EMI also constituted a key factor in MoE evaluations of those universities about their achievements in internationalizing higher education [6,7]. Consequently, the past two decades have seen a boom in EMI programs in Chinese higher education institutions [8].

Despite its prevalence in higher education, research has demonstrated that the implementation of EMI presents multiple difficulties that can impede academic performance, particularly for those who are not fluent in English as their first language [9,10,11]. The exclusive use of English can make it difficult for students to develop both scientific knowledge and scientific language proficiency [12,13]. In addition to language-related learning difficulties, students also face racialized positioning, stemming from the entwinement of knowledge education with language imperialism and English dominance that dates back to the colonial era. During that time, European powers imposed their languages and education systems on colonized peoples with the explicit aim of assimilation. Since then, English has become the global lingua franca, dominant in education, science, and technology, leading to the widespread use of EMI in higher education. However, EMI may perpetuate language imperialism and reinforce existing power structures, leading to racialized positioning where non-native English speakers may be perceived as less intelligent than their native English-speaking peers, in part due to difficulties they may experience in comprehending lectures or expressing themselves in English. As peripheral multilinguals, they may be positioned as inferior in knowledge negotiation and production [3,14,15,16,17]. In other words, their epistemic capability—the ability to contribute unique perspectives and knowledge from diverse cultural and intellectual traditions to the shared pool of understanding [18]—is often undervalued [19,20,21,22]. Therefore, it is imperative to understand and address the epistemic challenges faced by transnational students who originate from diverse national and linguistic backgrounds within EMI classrooms. However, despite the substantive EMI research, students’ epistemic conduct appears relatively unexplored. Questions about how students navigate epistemic inequities and the strategies they might use to promote equity in epistemic participation remain unanswered.

Drawing on the concept of “epistemic injustice” [23], this paper aims to address this issue by exploring how transnational students engage in epistemic participation in an EMI degree program. Our aims are twofold: first, we intend to unravel the challenges to epistemic participation students face. Second, we intend to make a practical contribution by shedding light on alternative epistemic capacities in English-dominant contexts.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Western Epistemic Dominance in EMI

Language is where knowledge is produced and reproduced. The choice of a language as a medium of education restrains epistemic frameworks and shapes a hierarchical form of social relations [24]. In academia, English is exclusively used as the medium language of knowledge communication [25,26,27,28]; this English dominance has been criticized as implicitly monopolizing the dissemination and evaluation of knowledge [17].

Similarly, English in EMI is often thought of as “a structure of knowledge”, “a framework used to categorize people and societies, and a series of images that form a system of representation that connects with other concepts” [29] (p. 277). Put in alternative terms, EMI is a site where knowledge production and dissemination are deeply entangled with colonialism and imperialism [30,31,32,33,34]; in the words of Li [35] (p. 8), “Knowledge production is one of the major sites in which the historical processes of imperialization, colonization, and the Cold War have become mutually entangled and exercise their power”. In line with Li’s description, EMI has been found to accentuate and perpetuate educational inequalities as “a service to the privileged, the rich, and the elite” [7] (p. 564). Similarly, Song [36] used empirical findings to demonstrate that students’ uneven linguistic and cultural capital further led to an implicit hegemonic hierarchy of Americanized academic norms and discipline-specific knowledge. As such, English assumed as a neutral and natural tool of knowledge transfer brings more problems than benefits [37]; it continues to reinforce knowledge exclusion without paying decent attention to transnational students’ struggles and capabilities in gaining and creating knowledge.

2.2. Epistemic (in)Justice

Knowledge participation can be understood as a process of epistemic participation regarding the kinds of knowledge that can be created, how knowledge is gathered, how knowledge is presented, and whom knowledge benefits [38,39]. Throughout these processes, “epistemic injustice” may occur [23,40,41]. The term “epistemic injustice” was first coined by Flicker [23], referring to “a wrong done to someone specifically in their capacity as a knower” [23] (p. 1). Fricker proposed two forms of epistemic injustice: testimonial injustice, which can be understood as a form of “identity prejudice” that occurs when individuals are “misjudged and perceived as epistemically lesser (a direct discrimination)” [23] (p. 53), and hermeneutical injustice, which refers to how a lacuna in collective interpretive resources positions people at an epistemic disadvantage when making sense of their social experiences.

In the context of EMI, epistemic injustice occurs when diverse types and forms of knowledge are excluded as equally valuable and relevant through curriculum design and communicative practices. Specifically, testimonial injustice is associated with a type of identity-prejudicial credibility deficit [20,23]. In the EMI context, transnational students, as peripheral multilingual scholars, may be given a deflated level of credibility. As a result, they might restrain from participating in knowledge sharing and keep silent during meaning-making and exchange. In this sense, they may fall victim to “epistemic violence” [42]; their “epistemic contribution capability” [23] is fundamentally constrained. This uneven participation would eventually lead to inequitable knowledge production and dissemination [19,20,21,22,36,37].

If testimonial injustice is a wrong done to individuals as knowledge givers, hermeneutical injustice is a wrong done to someone as a knower [23]. Hermeneutical injustice occurs at an earlier stage when individuals come across a gap in their collective interpretive resources and fail to make sense of their social experiences. A typical case of hermeneutical injustice involves transnational students who have difficulty understanding or communicating their own experiences because of a lack of equivalent or critical concepts in their native language or culture. Therefore, hermeneutical injustice is more associated with structural prejudices. In the context of EMI, hermeneutical injustice leads to transnational students being ill-understood and marginalized in knowledge communication.

Fricker’s epistemic injustice foregrounds the power and identity of individuals and groups in knowledge participation, thus providing a tool to investigate epistemic oppression and empowerment in EMI settings. Using epistemic injustice as the theoretical lens, this study seeks to answer the following research questions:

(1) What are transnational students’ perceived challenges that hinder their epistemic participation in an EMI program?

(2) What strategies do transnational students use to negotiate a more equal epistemic participation?

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Site and Participants

The current study was part of a larger ethnographic project in the School of International Relations and Public Affairs at a comprehensive university in a metropolitan city on China’s east coast. The university is famous for its internationalization and its campus hosts the largest number of foreign students in China. The School of International Relations and Public Affairs is a leading school in politics and has run EMI programs for eight years. The EMI program typically requires at least two years of coursework and a thesis and features a curriculum centered around concepts such as international relations theory, international political economy, international security, and global governance.

This study sampled an EMI master’s degree program composed of 10 Chinese students and 10 international students. Most faculty members are Chinese, many of whom received PhD degrees from world-renowned universities. An online–offline blended teaching mode was adopted to teach all courses due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Most international students who could not come to campus participated in courses via VooV or Zoom. Because of the program’s interdisciplinary value, students selected for this program hail from diverse academic backgrounds. Students whose native language is not English have passed the required threshold level of English proficiency (90 for the Internet-based TOEFL test or 7 for the IELTS test). Fifteen students ranging from 20–30 years old were willing to participate in this study; eight of whom were Chinese and the others were international students. The participants came from a wide range of countries and have heterogeneous educational backgrounds, as described in Table 1. Pseudonyms were used for all participants to protect their anonymity.

Table 1.

Student participants’ demographics.

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

The present study utilized classroom ethnography, including multiple data sources such as classroom observations, students’ reflexive journals, and semi-structured interviews, to generate a rich and multifaceted understanding of the research topic. Specifically, classroom observations offered an objective lens through which to examine the events and interactions that occurred within the classroom setting. Conversely, students’ reflexive journals provided a subjective account of their experiences and perspectives, allowing for a deeper understanding of the nuances and complexities of their individual experiences. Additionally, semi-structured interviews allowed us to explore the research topic in greater depth and to clarify any uncertainties that may have arisen from the other methods.

The first author conducted 16 weeks of classroom observation and took detailed field notes, with a particular focus on classroom interactions. Consistent with the definition of EMI, the primary language of instruction in our research classroom was English, accounting for approximately 95% of the class time. In addition, students’ weekly reflexive journals were collected and primarily focused on the challenges they faced in learning the course material and the strategies they used to overcome these challenges. Students were invited to write about their learning experiences in class and after class, focusing on their knowledge negotiation process. There was no word limit. Students were allowed to write in the language(s) that the researchers know (English, Chinese, and Japanese). Semi-structured interviews were conducted with all the students. Each lasted approximately 60 to 90 min. English was used for interviews with international students and Chinese was used with Chinese students. Interview questions focused on the challenges students encountered in epistemic participation and the strategies they used to cope with those challenges. In order to contextualize, triangulate, and confirm the information reported by participants, supplementary data was collected including participants’ reading materials, course syllabi, assignment guidelines, and writing samples. Member-checking was performed to verify and validate the interpretation of the data.

We adopted a three-step qualitative thematic analysis to analyze the data [43,44]. We mainly focused on students’ experiences in knowledge communication and their reflexivity during the learning process. We used participants’ own words for open coding. Codes that emerged during this stage include “linguistic challenges”, “self-abasement”, “lack of confidence”, and “social relations”. In the next stage, we aimed to generate patterns or recurrent themes related to our research questions such as “epistemic silencing”, “loss of epistemic confidence”, “necessity of epistemic diversity”, “background knowledge”, “social relationships with peers”, “weak ties to gain knowledge”, and “reflexivity”, with reference to the theoretical constructs. After several rounds of iterative cross-checking between interviews, reflexive journals, and classroom videos, major themes regarding the transnational students’ epistemic negotiation emerged to answer the research questions: “perceived challenges of epistemic participation” and “strategies to negotiate epistemic participation”.

4. Findings

4.1. Perceived Challenges of Epistemic Participation

One of the major challenges our participants perceived in the knowledge negotiation process was a lack of English language proficiency. In an English-only environment, non-native English-speaking learners are usually considered less efficient at acquiring subject knowledge [7,11,45,46]. Our participants confirmed this perceived inefficiency in their content learning. In her interview, LXR told us:

“I feel like I am doing English listening practices in class. I am listening to a story. Sometimes I only understand a general picture and I feel unable to express my own views. So, I don’t have a solid mastery of the professional knowledge. The classes only seem to broaden my horizons.”

According to LXR, knowledge flowed one way in the EMI classroom where she positioned herself as an outsider and a story-listener. Her lack of language proficiency restrained her ability to fully understand the subject content knowledge; she was even less able to contribute to the knowledge pool. Similarly, in her journal, LS reflected on her experience choosing not to participate in discussions due to her self-perceived low English proficiency. As LS confided in her interview:

“Because English is not our mother tongue, Chinese students generally don’t speak much, and we don’t say anything when we have ideas, because we stand no chance to win against those students who are good at English in the debate. They usually have more ideas because their English is good, and they can convey more information. Limited by language, our opinions seem superficial. Those students [students who are good at English] may despise us in their hearts.”

From the above excerpts, we can see that transnational students usually remain silent in classroom discussions, a phenomenon caused by their self-positioning as insufficient English users. As they equated their English proficiency with epistemic capability, they considered their opinions “superficial” and felt “despised” by more competent others (although only English-wise) in knowledge communication. This self-abasement illustrates a form of testimonial injustice as an identity-prejudicial credibility deficit [20,23]. As a result of their low confidence in their English proficiency, transnational students tend to believe that their views will be given a deflated level of credibility. As a result, they choose not to speak and therefore are not heard in the classroom, thus becoming subject to “epistemic violence” [40,42]. In this sense, English serving as the only collective hermeneutical resource in EMI classrooms negatively positions non-native English-speaking students as knowledge contributors.

Notably, students themselves might easily internalize the ideology of inferiority as peripheral English users and knowledge contributors. They exercise sensitivity to any possible intelligibility incurred owing to a gap in their English capability. This self-marginalization hampers students’ epistemic confidence, as described by our participant, Tina:

“Today’s subject is difficult for me, both emotionally and physically... They [English native speakers] are more confident and they speak more calmly... By the way, last semester was just a shock for me. I am so depressed because I could not communicate my ideas in English, and generally felt disappointed in my level of language. In addition, my pronunciation suffers from excitement.”(Reflexive journal, Tina, a Russian student)

As we can see from the above expert, the superiority of English in EMI gnawed away at a non-native English speaker’s intellectual confidence. Disappointment in their language ability damages students’ epistemic function as well. In this sense, students suffer a prolonged erosion of epistemic confidence [23] and may be “ongoingly disadvantaged, repeatedly failing to gain items of knowledge they would otherwise have been able to gain” [23] (p. 49).

In addition to testimonial injustice, our participants also fell victim to hermeneutical injustice as they came across a gap in their collective interpretive resources in making sense of their academic experiences, as evidenced by Barbara in her reflexive journal:

“This fact is frustrating...I am not familiar with those concepts. We don’t have those ideas [in Mongolia]. So when they [English-native speakers] discuss those concepts, I can only guess what they mean even I can speak English.”(Reflexive journal, Barbara, a Mongolian student)

As Barbara revealed, students’ epistemic silence may stem from a lack of critical concepts produced in Anglophone contexts. In EMI, transnational students’ lack of learning experiences in an Anglophone environment can be seen as a form of hermeneutical injustice occurring at a prior stage, when a gap in collective interpretive resources puts students at an unfair disadvantage in making sense of their academic experiences. This indicates that the quandary in epistemic participation stems not only from language skills but that knowledge points and the methods required to unpack those knowledge points are genuinely challenging.

4.2. Strategies to Negotiate Epistemic Participation

In this section, we share our participants’ experiences of making their voices heard in knowledge participation and summarize strategies for transnational students to negotiate a more equal learning environment in EMI contexts. We categorize their strategies into two groups: individual-cognitive and social-cognitive.

4.2.1. Individual-Cognitive: Prior Knowledge

In EMI, language is often regarded as the most challenging part of mastering knowledge. However, our participant ZH’s experience indicates that prior knowledge may compensate for linguistic disadvantage and could be a key for transnational students to actively participate in knowledge negotiation. ZH completed her bachelor’s degree in sociology. In the course Qualitative Research Methodology, ZH’s prior knowledge of sociology enabled her to talk in a more coherent way in group discussions, as she recalled in her reflexive journal:

“I was surprised to find that I could be relatively coherent and relatively fluent, which was really much better than my speeches in other courses. … If you asked me to say something in Chinese, I might not be able to say something as well. If you asked me to translate it into English, I feel that I am even less able to say anything.”(Reflexive journal, ZH, a Chinese student)

Compared with other courses, ZH participated more actively in the course where she was equipped with prior knowledge, showing that prior knowledge is pivotal although usually insufficient for students to negotiate knowledge participation in EMI classes [47,48]. Without prior knowledge, students cannot properly comprehend their learning experience, let alone exchange their views with others.

4.2.2. Individual-Cognitive: Reflexivity

Confronting epistemic challenges, our participants emphasized the necessity of reflective thinking in enhancing their epistemic capacity. In her journal, ZH expressed the critical importance of reflexivity:

“I use a metaphor to describe my understanding of the nature/process of meaning-making and exchange in my English-medium learning. Maybe the knowledge learned in English-medium learning is a complex process of “milking cows to make cheese.” A job that requires multiple processes to complete? But I am not a robot, I also have reflexivity in it (I really like this word haha), that is, I will also digest and connect everything based on my previous knowledge system. It is a process of constantly refuting and defending, like a debate. You can’t always say what it is, you just write it down, but there is something in your mind that is producing a reflexive flexibility so that some knowledge can be obtained.”(Reflexive journal, ZH, a Chinese student)

Reflexivity incorporating personal epistemology can be described as “epistemic reflexivity” [49] where personal beliefs and cognitions related to knowledge and knowing promote sustainable learning in classrooms [50]. As ZH described in her reflexive journal, reflexivity helps her interact and react by drawing on different cultural and epistemic traditions. In an EMI environment, to make better sense of their learning experience, students need to be well aware of their own subjectivity so they can use diverse linguistic and cultural resources to better understand their learning experience. In the following excerpt, ZH described her experience exercising critical reflexivity towards linguistic and epistemic diversity and explained the process of appropriating knowledge produced in languages other than English:

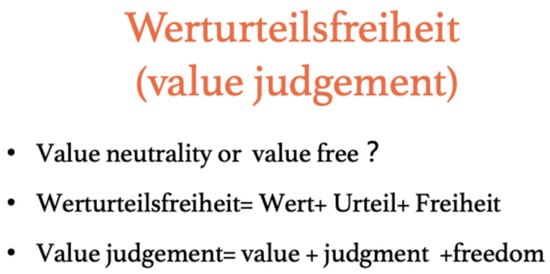

“I put this kind of bilingual and trilingual comparison in my PPT (see the following PPT slide for details), such as Max Weber’s “Understanding Sociology.” Weber proposed a concept of value judgment. The concept was proposed in German. We should respect history. Moreover, the original version can help people better understand the concepts and avoid translation distortions. For example, the “value judgment” I put here, you may find it strange to analyze in either English or Chinese. Why are these two specific words combined together? But if you look at its German composition, you will suddenly realize that it is a complete word in German. It was not invented by randomly putting together three unrelated things, but just taking one word apart.”

By presenting the example in the reflexive journal (Figure 1), ZH demonstrated a strong awareness of epistemic issues construed through other languages, underscoring the need to understand the concept of “value judgment” in its original language—German. This translingual conduct constructs transepistemic practices in the classroom featuring Europe-centrism, authorizing knowledge created in other languages, thus enhancing both hermeneutical and testimonial justice in the EMI context.

Figure 1.

ZH’s bilingual PPT slide.

4.2.3. Social-Cognitive: Peer Support

Epistemic (in)justice is irrepressibly connected with social power and social connections [23]. In our data analysis, we also recognize that epistemic capability is socially constructed in EMI contexts. Coping with epistemic challenges requires not only individual efforts but also social networks. For example, YCR shared her successful experience in a group project during her interview:

“After I entered the group, I observed the members (I like the group, yayyy), so I directly told everyone my thoughts, and then we basically determined the direction for our research. Everyone said their own ideas and everyone helped each other out. Joy took notes and organized the language. Soon the project came into shape.”

One of EMI’s most prominent merits is bringing multilingual students together to forge novel perspectives. In a relaxed and friendly social space, students can draw on their entire linguistic repertoires to develop academic literacies in multiple languages. From an epistemic perspective, students’ active engagement with peers facilitates their epistemic contributions. In this sense, epistemic capacity is socially constructed. Earning social advantages, then, serves as a crucial strategy to earn epistemic advantages.

4.2.4. Social-Cognitive: Collaborative Learning

Our data showed that our participants actively used diverse social and material resources to facilitate their epistemic participation. In her interview, YCR told us:

“Getting help across disciplines, the Internet, and not only academic websites, Douban group [a Chinese online database and social networking service], Sina Weibo [Chinese Twitter], are all channels for me to obtain resources. The help we can get in the real world is relatively limited, and we can get some information through weak relationships... Sociology, History, Science and Engineering, although I don’t understand all of these subjects, transdisciplinary habits will always bring some inspiration.”

YCR demonstrated the usefulness of diverse social and material resources in an EMI setting to help students gain alternative perspectives on their academic studies. From her interview, we can see that epistemic challenges are not merely linguistic, but lie in the capability to tactically orchestrate all the social, cultural, and material resources embedded in the learning environment. YCR treated diverse social websites and material conditions as equal epistemic resources for shaping meaning [15,51,52]. This material orientation gives credibility to diverse sociocultural knowledge as a shared epistemic resource for students from different backgrounds in knowledge negotiation. Knowledge gained from diverse resources might provide alternative views contrasting the English-dominated global academia, thus serving as an effective way to cope with the epistemic dominance of Anglophone cultures.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

In this study, transnational students’ epistemic perceptions and practices elucidate potential strategies to enhance epistemic justice and diversity in EMI contexts. This paper echoes a de-colonial and epistemic turn in EMI studies, further shedding light on the epistemic realities of students’ EMI learning [20,21,22,36]. By showing how students coped with epistemic challenges by using individual-cognitive and social-cognitive strategies, we also provide potential strategies for transnational students to enhance epistemic justice and diversity in EMI learning contexts.

In line with previous studies, we find that transnational students are negatively positioned in the learning process due to the hegemonic position of English in the higher education context [9,13,37,53]. From an epistemic perspective, we argue that this disposition can be seen as a form of epistemic violence that results in students’ silence in meaning-making and exchange. The English-only implementation of EMI encroaches not only on the linguistic rights but also on the epistemic opportunities of students from non-Anglophone countries [21,22,36]. The phenomenon of transnational students’ linguistic inferiority and subsequent self-marginalization constitutes a form of epistemic distortion. Over time, this prolonged erosion of epistemic confidence [23] can disenfranchise transnational students, preventing them from contributing unique knowledge from diverse linguistic and cultural traditions. Language use can be indicative of cultural roots, ways of thinking, and being. Consequently, this process of depreciating or othering students’ language skills may also extend to other aspects of their identity, such as their cultural background or ways of thinking, ultimately jeopardizing the ethos of EMI as a transnational education strategy for developing global talent [54,55].

Additionally, this study reveals how students can enhance epistemic diversity by sorting out influential factors in their knowledge participation. On one hand, we argue that epistemic capability resides in individual-cognitive abilities such as prior knowledge and reflexivity. As shown in ZH’s case, epistemic virtue needs transnational students to exercise a reflexive critical sensitivity to any reduced intelligibility as well as to notice the possibility of promoting epistemic diversity to create a more balanced cognitive, social, and epistemic environment. Additionally, we argue that “epistemic contribution capability” [23] is socially and materially distributed; eradicating epistemic injustices will ultimately take more than individual efforts and will require collective social efforts and material conditions.

Our study suggests that EMI needs to be re-constructed as a space where transnational students can provide alternative views and solutions to pertinent or subject contents. The sustainability of EMI resides in the flexibility of students to “communicate and appropriate knowledge, and give voice to new sociopolitical realities by interrogating linguistic inequality” [56] (p. 261). To enhance epistemic inclusion, students may actively equip themselves with necessary prior knowledge in English or their native languages. Critical reflexivity can also serve as an impetus to promote epistemic diversity in everyday teaching and learning. Students can adopt a repertoire approach to maximize their epistemic potential by promoting flexibility, creativity, and subjectivity in their use of linguistic, cultural, and social resources.

This research contributes to sustainability in several ways. Firstly, it sheds light on the often-overlooked issue of epistemic injustice in educational settings, which can have long-lasting implications for students’ learning and their ability to contribute to sustainable development efforts. By identifying the unequal power relations and resulting epistemic silence that transnational students face in an EMI international relations master’s program at a Chinese university, this research highlights the need for more equitable and inclusive educational practices. Moreover, the study provides potential strategies for transnational students to counter the hegemony of English in EMI learning contexts, which can help promote more sustainable and socially just educational practices. By drawing on individual-cognitive and social-cognitive resources, students can better negotiate their access to knowledge and participate more effectively in classroom discussions, which can lead to better learning outcomes and a more equitable distribution of epistemic resources. Finally, the research has implications for decoloniality in EMI education, which is an important aspect of promoting sustainability. By recognizing and challenging the dominance of English and Western epistemologies in EMI education, we can create more inclusive and diverse learning environments that better reflect the needs and perspectives of students from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds. This can help promote a more sustainable and equitable global society by empowering individuals from diverse backgrounds to contribute to sustainable development efforts.

Overall, EMI is characterized by its multicultural and multilingual nature as a means of achieving internationalization in higher education [53]. It can serve as a valuable platform for individuals and groups to leverage their linguistic, cultural, and epistemic resources for knowledge innovation by promoting innovative thinking and practices that enhance transnational students’ gains in transnational education [37].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z.; Formal analysis, Y.Q.; Data curation, Y.Q.; Writing—original draft, Y.Q.; Writing—review & editing, Y.Z.; Supervision, Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jenkins, J. English as a Lingua Franca in the International University: The Politics of Academic English Language Policy, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014; pp. 1–256. [Google Scholar]

- Piller, I. Language ideologies. In The International Encyclopedia of Language and Social Interaction, 1st ed.; Tracy, K., Ilie, C., Sandel, T., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: West Sussex, UK, 2015; Volume 1, pp. 917–927. [Google Scholar]

- De Costa, P.; Green-Eneix, C.; Li, W. (Wendy) Problematizing EMI language policy in a transnational world: China’s entry into the global higher education market. Engl. Today 2022, 38, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaro, E. English Medium Instruction: Language and Content in Policy and Practice, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 1–344. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education. Statistical Report on International Students in China for 2018. 2018. Available online: http://en.moe.gov.cn/news/press_releases/201904/t20190418_378586.html (accessed on 26 December 2022).

- Galloway, N.; Numajiri, T.; Rees, N. The “internationalization”, or “Englishization”, of higher education in East Asia. High. Educ. 2020, 80, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Li, L.; Lei, J. English-medium instruction at a Chinese University: Rhetoric and reality. Lang. Policy 2014, 13, 21–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, H.; McKinley, J.; Xu, X.; Zhou, S. Investigating Policy and Implementation of English Medium Instruction in Higher Education Institutions in China; British Council: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/sites/teacheng/files/K155_Investigating_policy_implementation_EMI_China_web.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2022).

- Aizawa, I.; Rose, H. An analysis of Japan’s English as medium of instruction initiatives within higher education: The gap between meso-level policy and micro-level practice. High. Educ. 2019, 77, 1125–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F. Review of English as a medium of instruction in Chinese universities today: Current trends and future directions. Engl. Today. 2018, 34, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, N.; Ruegg, R. The provision of student support on English Medium Instruction programmes in Japan and China. J. Engl. Acad. 2020. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, J.; Rose, H.; Curdt-Christiansen, X.L. EMI in Chinese higher education: The Muddy water of ‘Englishization’. Appl. Linguist. Rev. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pun, J.; Nathan, T.; Neil, B. Questioning the Sustainability of English-Medium Instruction Policy in Science Classrooms: Teachers’ and Students’ Experiences at a Hong Kong Secondary School. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, D. The dark side of EMI?: A telling case for questioning assumptions about EMI in HE. Educ. Linguist. 2022, 1, 82–107. [Google Scholar]

- Canagarajah, S. Materializing ‘competence’: Perspectives from international STEM scholars. Mod. Lang. J. 2018, 102, 268–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. International students in China: Cross-cultural interaction, integration, and identity construction. J. Lang. Identity Educ. 2015, 14, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piller, I.; Zhang, J.; Li, J. Peripheral multilingual scholars confronting epistemic exclusion in global academic knowledge production: A positive case study. Multilingua 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricker, M. Epistemic contribution as a central human capability. In The Equal Society: Essays on Equality in Theory and Practice, 1st ed.; Hull, G., Ed.; Lexington Books: Maryland, MD, USA, 2015; pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kester, K.; Chang, S. Whither epistemic (in)justice? English medium instruction in conflict-affected contexts. Teach. High. Educ. 2022, 27, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, L. Towards a social and epistemic justice approach for exploring the injustices of English as a Medium of Instruction in basic education. Educ. Rev. 2022, 74, 927–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phyak, P.; Sah, P. Epistemic injustice and neoliberal imaginations in English as a medium of instruction (EMI) policy. Appl. Linguist. Rev. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.G.; Stelma, J. Epistemic outcomes of English medium instruction in a South Korean higher education institution. Teach. High. Educ. 2022, 27, 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricker, M. Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing, online ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 1–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tollefson, J.W.; Tsui, A.B. Medium of instruction policy. In The Oxford Handbook of Language Policy and Planning, 1st ed.; Tollefson, J.W., Perez-Milans, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 257–279. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Zheng, Y. Multilingualism and higher education in Greater China. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2019, 40, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zheng, Y. “Heavy mountains” for Chinese humanities and social science academics in the quest for world class universities. Comp. A J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2020, 50, 554–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultgren, A.K. Lexical borrowing from English into Danish in the Sciences: An empirical investigation of “domain loss”. Int. J. Appl. Linguist 2013, 23, 166–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Guo, X. Publishing in and About English: Challenges and Opportunities of Chinese Multilingual Scholars’ Language Practices in Academic Publishing. Lang. Policy 2019, 8, 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S. The West and the Rest: Discourse and Power. In Race and Racialization: Essential Readings, 2nd ed.; Das Gupta, T., James, C.E., Maaka, R.C.A., Galabuzi, G.E., Anderson, C., Eds.; Canadian Scholars Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1992; pp. 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Buckner, E.; Stein, S. What Counts as Internationalization? Deconstructing the Internationalization Imperative. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2019, 24, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, R. Southern Theory and World Universities. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2017, 36, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, R. Confronting Epistemological Racism, Decolonizing Scholarly Knowledge: Race and Gender in Applied Linguistics. Appl. Linguist. 2020, 41, 712–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, A. The Cultural Politics of English as an International Language, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1–390. [Google Scholar]

- Phipps, A. Decolonising Multilingualism: Struggles to Decreate, 1st ed.; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2019; pp. 1–213. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W. Translanguaging as a political stance: Implications for English language education. ELT J. 2021. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y. “Uneven consequences” of international English-medium-instruction programmes in China: A critical epistemological perspective. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2021, 42, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, J. “So, only relying on English is still troublesome”: A critical examination of Japan’s English medium instruction policy at multiple levels. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, A. Knowledge in a Social World; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1999; pp. 1–424. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y. Multilingual Research in a Post-COVID Era: Reflection and Prospection. Contemp. Foreign Lang. Stud. 2021, 451, 64–74. [Google Scholar]

- Dotson, K. Conceptualizing epistemic oppression. Soc. Epistemol. 2014, 28, 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricker, M. Epistemic injustice and the preservation of ignorance. In The Epistemic Dimensions of Ignorance, 1st ed.; Peels, R., Martijn, B., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016; Volume 1, pp. 144–159. [Google Scholar]

- Spivak, G.C. Can the subaltern speak? In Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, 1st ed.; Carry, N., Grossberg, L., Eds.; University of Illinois Press: Urbana-Champaign, IL, USA, 1988; Volume 1, pp. 271–313. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, H.; Cowley, S. Developing a grounded theory approach: A comparison of Glasser and Strauss. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2004, 41, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative content analysis. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis, 1st ed.; Flick, U., Ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2014; Volume 1, pp. 170–183. [Google Scholar]

- Galloway., N.; Ruegg, R. English Medium Instruction (EMI) lecturer support needs in Japan and China. System 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Zhang, J.; May, S. Implementing English-medium instruction (EMI) in China: Teachers’ practices and perceptions, and students’ learning motivation and needs. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2019, 22, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, J. Teaching for Transfer: Challenging the Two Solitudes Assumption in Bilingual Education. In Encyclopedia of Language and Education, 2nd ed.; Hornberger, N.H., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2008; Volume 2, pp. 1528–1538. [Google Scholar]

- Simonsmeier, B.; Flaig, M.; Deiglmayr, A.; Schalk, L.; Schneider, M. Domain-specific prior knowledge and learning: A meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 57, 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feucht, F.C.; Brownlee, J.L.; Schraw, G. Moving Beyond Reflection: Reflexivity and Epistemic Cognition in Teaching and Teacher Education. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 52, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, M. The Reflexive Imperative in Late Modernity, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 1–330. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, M.M.; Lee, C.K.J.; Jin, T. A translanguaging and trans-semiotizing perspective on subject teachers’ linguistic and pedagogical practices in EMI program. Appl. Linguist. Rev. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.M.; Li, Z.J.; Jiang, L. Navigating the instructional settings of EMI: A spatial perspective on university teachers’ experiences. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2021. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Hu, G. English medium instruction, identity construction and negotiation of Teochew-speaking learners of English. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Costa, P.; Green-Eneix, C.; Li, W. (Wendy) Embracing Diversity, Inclusion, Equity and Access in EMI-TNHE: Towards a Social Justice-Centered Reframing of English Language Teaching. RELC J. 2021, 52, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Zheng, Y. Language Policy and Planning in Japan’s English as Medium of Instruction Degree Program in Higher Education. Chin. J. Lang. Policy Plan. 2021, 6, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- García, O.; Kano, N. Translanguaging as process and pedagogy: Developing the English writing of Japanese students in the US. In The Multilingual Turn in Languages Education: Opportunities and Challenges; Conteh, J., Meier, G., Eds.; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2014; Volume 3, pp. 258–277. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).