Abstract

Central Asia borders China and was the first stop of China’s opening to the west. Studying the evolving status of agricultural products in the global value chain since China and Kyrgyzstan established diplomatic relations in 1992 can facilitate China’s “Belt and Road” initiative and strengthen agricultural cooperation. Based on FAOSTAT and UN Comtrade data, this paper classifies agricultural products into three categories: primary agricultural products, rough-processed agricultural products, and deep-processed industrial products. An indicator system was constructed for measuring the status of agricultural products in the global value chain. Using the results of the NET trade index, this paper analyzed the evolving status of Chinese and Kyrgyzstani agricultural products in the global value from 1995 to 2020. The results showed that the status of Chinese and Kyrgyzstani primary agricultural products has continued to decline, with Kyrgyzstan slightly better than China. The status of Chinese rough-processed agricultural products was slowly declining, while Kyrgyzstan’s status dropped sharply by 2020. China has a solid foundation in deep-processed agricultural products, while Kyrgyzstan’s status was relatively low. Suggestions for future cooperation between China and Kyrgyzstan are discussed, such as strengthening agricultural technology exchanges and cooperation, expanding trade in high-quality agricultural products, etc.

1. Introduction

In September and October 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping first proposed the “Belt and Road” during his visit to Kazakhstan and Indonesia—that is, the “New Silk Road Economic Belt” and the “21st Century Maritime Silk Road”. Guided by the principle of “Consultation, Contribution, and Shared Benefits”, China hopes to take the initiative to carry out more economic cooperation with countries and regions along the sea and land from China to Europe and build a community with a shared future for humankind [1]. Central Asia is an important node in the countries and regions along the “Belt and Road” proposed by China and is the first stop of China’s opening to the west. China attaches great importance to diplomatic relations with Central Asia and maintains friendly exchanges in various fields such as economy, politics, and culture, and it has achieved remarkable results in agricultural product trade, agricultural investment, and agricultural technology exchanges and cooperation [2]. It has been 30 years since China established diplomatic relations with major Central Asian countries in 1992 [3]. According to Chinese customs data, the scale of agricultural trade between China and the five Central Asian countries (Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, and Tajikistan) increased from USD 175 million in 1992 to USD 1073 million in 2021. Among them, the scale of imported agricultural products increased from USD 3.41 million in 1992 to USD 466 million in 2021, which is about 137 times the original; the scale of exported agricultural products increased from USD 171 million in 1992 to USD 571 million in 2021 [4].

Located in the heart of Eurasia, Kyrgyzstan is a landlocked country in northeastern Central Asia. It has deep geopolitical and economic ties with China and shares a border with China’s Xinjiang Province [5]. Kyrgyzstan joined the WTO in 1998, being the first Central Asian country to accede to the WTO. It has one of the most open economies and the most transparent and loose trade policies and tariff barriers in Central Asia. It also serves as an important transit point for Chinese goods to enter the Caspian Sea region, Russia, and Europe [6]. Based on the NET trade index model, this paper systematically analyzed the evolving status of Chinese and Kyrgyzstani agricultural products in the global value chain, as well as their competitive advantages from 1992 to 2020, with the hope of finding new space for mutual agricultural cooperation. This is of great significance for China and Kyrgyzstan and other Central Asian countries as they jointly build the “Belt and Road” with high quality.

2. Literature Review

Gereffi (1999) proposed the concept of the global value chain based on the global commodity chain, which mainly includes a series of links such as design, production, assembly, marketing, after-sales service, etc. The profit level of each link in the value chain is different [7]. Research on the status of the global value chain helps judge the position of a certain industry in a country in the international division of labor and can also help promote the status of the country’s value chain as well as the implementation of strength-based international cooperation. At present, the extant scholarship on global value chains mostly focuses on industrial products, the equipment manufacturing industry, high-speed rail, and other fields [8,9]. For example, Schoot (2008) studied the level difference of export products between developed and developing countries based on the export product price measurement method [10]. Similarly, Johnson and Noguera (2012) applied the value-added trade input–output method and calculated the proportion of export trade volume in total exports for 42 countries in the world from 1970 to 2004. They also discussed the issue of global production segmentation [11]. The existing research on global value chains of agricultural products can be organized into three major themes [12,13,14,15,16]. First, agricultural trade issues are analyzed from a macro view based on the perspective of global value chains. For example, Zhang et al. (2016) noted that there were some structural changes in the global agricultural product trade. Notably, with the development of processing technology, there was a gradual expansion from primary agricultural products to refined and deep-processed agricultural products [17]. Zhang (2017) contended that the bilateral agricultural product trade between China and ASEAN countries mainly corresponds to the middle segment of the global value chain, that is, the production link mainly based on the planting and processing of primary agricultural products. This is the weakest value-added link in the global value chain [18]. The second line of research employs a mesoscopic view to examine the status of agricultural products of a certain industry in a country in the global value chain. Huang and Tan (2008) discussed the upgrading of Xinjiang’s tomato processing industry from the perspective of global value chain governance and proposed a “three-stage” upgrade strategy (i.e., introducing foreign capital to achieve the aggregation of enterprises in the planting and processing of the tomato industry chain, cultivating the marketing capabilities of tomato enterprises, and challenging the status of large retailers as the driver of the value chain) [19]. The third stream of research is to study the status and upgrading of the global value chain of agricultural enterprises from a micro-perspective. Liu and Zhou (2011) analyzed the deployment and development trend of the global agricultural product value chain of “agriculture-related enterprises” among the Fortune 500 enterprises in 2008 [20]. They also made suggestions on how to enhance the international competitiveness of local agricultural products, how to improve the governance of the value chain, among others.

In addition, Ersin and Bildirici (2017) took Kyrgyzstan and other five transitional economies as examples to study the impact of inflation, openness to trade, and value added in production during the period 1989–2011. They found that openness to trade had a positive effect on economic growth [21]. In terms of agricultural trade between China and Central Asia and Kyrgyzstan, from 2010 to 2018, China mainly imported low-tech value-added primary agricultural products such as grains, leather, and animal and plant raw materials from Central Asian countries (Xu, 2021) [22]. China’s agricultural exports to Kyrgyzstan mainly included nuts, vegetables, fruits, aquatic products, beverages, etc. From 1992 to 2018, China’s exports of land-intensive agricultural products (e.g., grains, oilseeds, etc.) to Kyrgyzstan gradually declined, while the export scale of labor-intensive agricultural products (e.g., nuts, flowers, vegetables, etc.) first increased and then declined (Yan et al., 2021) [23].

The existing studies are informative in that they provide different research perspectives for an in-depth understanding of the international division of labor for different products and illuminate their status in the global value chain. However, they are also limited because few scholars have studied international agricultural cooperation from the perspective of global value chains. Considering such a limitation, this paper used the NET trade index to evaluate the evolving status of agricultural products in China and Kyrgyzstan in the global value chain since the establishment of diplomatic relations between the two countries 30 years ago. On this basis, some suggestions were put forward for the high-quality development of agricultural cooperation between the two countries in the future.

Some possible contributions of this paper are as follows: (a) Agricultural products were divided into three categories according to the degree of processing, namely, primary agricultural products, rough-processed agricultural products, and deep-processed agricultural products. Combining the agricultural characteristics of China and Kyrgyzstan, 15 kinds of agricultural products were selected to build a global value chain status measurement index system. (b) Drawing on the measurement of industrial products in the global value chain, the NET trade index method was used to evaluate the evolving status of agricultural products in China and Kyrgyzstan in the global value chain during the past 30 years.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Methods

The measurement of a country’s status in the global value chain is primarily concentrated in fields such as manufacturing [24,25,26]. The methods used for measurement mainly include the traditional method of recording export trade, the vertical specialization index, the Trade in Value Added statistical method, and the NET trade index [27,28,29]. For example, Zhou and Luo (2017) selected the NET trade index method, which considered both export and import factors, to determine the status of industrial products at different stages of the industrial chain in the global value chain [30]. Considering the characteristics of agricultural products and data availability, this paper also drew on such a practice by using the NET trade index to measure the status of a country’s agricultural products at different production stages in the global value chain. Moreover, as a measurement method for agricultural trade, the net trade index, compared with Balassa’s Revealed Comparative Advantage Index (RCA, Revealed Comparative Advantage) and Revealed Symmetrical Comparative Advantage Index (Revealed Symmetric Comparative Advantage, RSCA), considers a country’s trade import and export factors and overcomes the disadvantages of only considering export unilateral factors. This disadvantage often refers to the asymmetric range of values or the inability to fully demonstrate the true international competitiveness of a product [31].

The NET trade index method, also known as the Trade Specialization Coefficient (TSC), measures the net export ratio of a product to reflect the degree of competitive advantage of a certain type of commodity in the world market relative to other countries [32]. The calculation formula is as follows:

where represents the export scale of agricultural product i in country j in year t, and represents the import scale of agricultural product i in country j in year t. The values of NET range from −1 to 1, with smaller values indicating weaker international competitiveness of the product and a lower position in the global value chain (see Table 1).

Table 1.

The meaning of NET.

3.2. Technical Classification of Agricultural Products

In the existing literature, scholars tend to classify agricultural products differently according to different research directions and goals. For example, when examining the trade structure and comparative advantage of agricultural products [33,34,35,36], scholars often divide agricultural products into bulk, animal, food, and other categories [37,38], or into bulk agricultural products, animal products as food, non-food animal products, fish products, horticultural products such as vegetables and fruits, beverages and tobacco, and others [39,40]. Adopting the classification scheme of Regmi et al. (2005) [41], Liu and Zhou (2011) classified agricultural products into primary bulk commodities, semi-processed products, produce/horticulture, and processed products, which they used to analyze the situation and competitiveness of China’s agricultural trade in the global value chain. Drawing on such a practice, this paper roughly divided agricultural products into primary agricultural products, rough-processed agricultural products, and deep-processed agricultural products according to the processing degree of agricultural products (Table 2). Such a classification scheme can provide an in-depth analysis of the status and competitive advantages of each country’s agricultural products in the global value chain. In general, the deeper the processing of agricultural products, the higher the added value of the product, and the higher its status in the global value chain.

Table 2.

Technical classification and HS code of agricultural products in this paper.

3.3. Data Sources

The data used in this paper were from the United Nations Commodity Trade Statistics Database (UN Comtrade) [42] and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) database [43]. To maintain the consistency of HS codes, when measuring the global value chain status of agricultural products of the two countries, the corresponding data in the UN Comtrade database were selected. Since agricultural trade data for Kyrgyzstan were first documented in the UN Comtrade database in 1995, the agricultural trade data starting from 1995 were selected for empirical analysis. When analyzing the trade structure of agricultural products between China and Kyrgyzstan, the corresponding data in the FAO database were selected to focus on the main varieties of agricultural products imported and exported between the two countries. The database contains agricultural product trade data of sub-categories since the establishment of diplomatic relations between the two countries in 1992 (although there is no unified HS code). To avoid the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, a decision was made to mainly select the data in 2019 for analysis, supplemented by the data in 2020. The goal of this paper was to focus on the evolving status of agricultural products in the global value chain since the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Kyrgyzstan. Therefore, the breakpoint data (trade scale was denominated in US dollars, regardless of inflation and exchange rate changes) were selected. Moreover, for the sake of comparability, the import and export trade data of China’s agricultural products in the same year were also used.

4. Results

4.1. The Overall Situation of China’s Trade in Agricultural Products with Kyrgyzstan

According to statistics from the FAO (Table 3), the total agricultural trade between China and Kyrgyzstan increased from USD 12.2 million in 1992 to USD 2690 million in 2019 (approximately USD 119.8 million in 2020), more than 20 times the original. Among them, China’s export of agricultural products to Kyrgyzstan increased from USD 11.22 million in 1992 to USD 259 million in 2019 (approximately USD 117.3 million in 2020), and China’s import of agricultural products from Kyrgyzstan increased from USD 0.98 million to USD 9.97 million in 2019 US dollars (USD 2.55 million in 2020). In 2019, China exported 81 kinds of agricultural products to Kyrgyzstan, mainly nuts, fruits, and vegetables; China imported 34 kinds of main agricultural products from Kyrgyzstan, mainly livestock products and honey.

Table 3.

The scale of agricultural trade between China and Kyrgyzstan from 1992 to 2020 (unit: thousand USD).

4.2. The Evolving Status of Agricultural Products in the Global Value Chain in China and Kyrgyzstan

4.2.1. Primary Agricultural Products

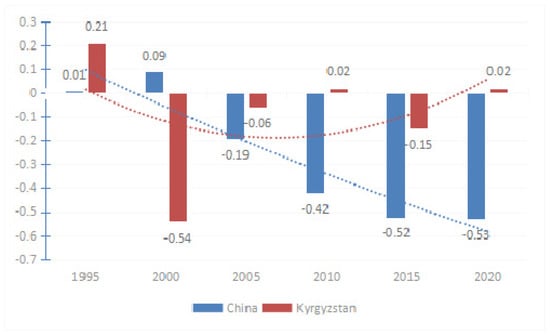

From 1995 to 2020, the NET value of primary rural goods in China and Kyrgyzstan showed a fluctuating downward trend (Figure 1). Among them, the NET trade value of China’s primary agricultural products dropped from 0.01 in 1995 to −0.53 in 2020, and its status in the global value chain was relatively low. Kyrgyzstan’s NET trade value of primary agricultural products showed a “W”-shaped fluctuating downward trend. The NET trade value dropped rapidly from 0.21 in 1995 to −0.54 in 2000, and it gradually rose to 0.02 in 2010. It dropped again to −0.15 in 2015 and recovered to 0.02 in early 2020, with a certain global value status. As can be seen from Figure 1, Kyrgyzstan’s position in the global value chain of primary agricultural products in 2020 was significantly higher than that of China.

Figure 1.

The evolving trend of the NET of primary agricultural products between China and Kyrgyzstan from 1995 to 2020.

The NET values of live animals (HS Code: 01), oilseed kernels and fruits (HS Code: 12), and edible fruits (HS Code: 08) in China’s primary agricultural products dropped significantly (as shown in Table 4) from 0.86, 0.72, and 0.70 in 1995 to −0.03, −0.88, and −0.26 in 2020, respectively. Among Kyrgyzstan’s primary agricultural products, live animals such as cattle and sheep, vegetables (HS Code: 07), and honey (HS Code: 0409) had a high status in the global value chain, with the NET values standing at 0.60, 0.78, and 0.95 in the last 25 years (as shown in Table 4). However, the status of Kyrgyzstan’s grains in the global value chain was very low, with an average NET value of −0.97 from 1995 to 2020, with its major source being importation.

Table 4.

NET values and average values of related products in primary agricultural products in China and Kyrgyzstan from 1995 to 2020.

Compared with China, Kyrgyzstan had a slightly better position in the global value chain of primary agricultural products (as shown in Figure 1). Kyrgyzstan had obvious comparative advantages in primary agricultural products such as live animals, oil-containing kernels and fruits, and honey. The mean values of the NET were higher than those of China (Table 4).

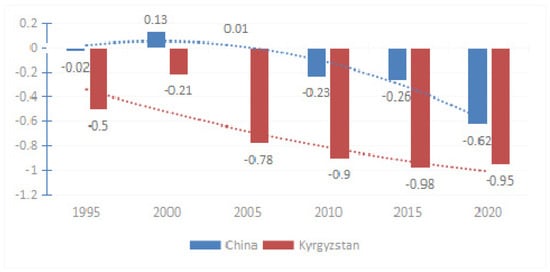

4.2.2. Rough-Processed Agricultural Products

From 1995 to 2020, except for 2000, the value of the NET trade index of rough-processed agricultural products between China and Kyrgyzstan showed a downward trend (Figure 2). China’s NET trade index of rough-processed agricultural products first rose from −0.02 in 1995 to 0.13 in 2000 and then gradually dropped to −0.62 in 2020, indicating a low position in the global value chain. Kyrgyzstan’s NET trade index of rough-processed agricultural products stayed consistently below 0, most notably −0.9, −0.98, and −0.95 in 2010, 2015, and 2020, respectively, and its status in the global value chain was extremely low. In 2020, the status of China in the global value chain of rough-processed agricultural products was slightly higher than that of Kyrgyzstan.

Figure 2.

The evolving trend of the NET trade index values of rough-processed agricultural products between China and Kyrgyzstan from 1995 to 2020.

Among China’s rough-processed agricultural products, the NET trade index values of meat and edible offal (HS Code: 02) and animal and vegetable oils (HS Code: 15) dropped significantly (see Table 5). Among them, meat and edible offal dropped from 0.83 in 1995 to −0.95 in 2020; the average value of the NET trade index of animal and vegetable oils from 1995 to 2020 was −0.81, with the lowest value documented at −0.92 in 2010. This shows that after 2000, China’s roughly processed agricultural products were mainly imported, especially meat and edible offal and animal fat products. Among Kyrgyzstan’s rough-processed agricultural products, the NET trade index values of flour milling industrial products (HS Code: 11), meat and edible offal, and animal and vegetable oils dropped from −0.84, 0.67, and−0.75 in 1995 to −0.98, −0.97, and −0.99 in 2020, respectively (as shown in Table 5). This shows that the three types of agricultural products had extremely weak competitiveness in the global agricultural product market, and their value chain status was extremely low.

Table 5.

NET value and average value of related products in rough-processed agricultural products in China and Kyrgyzstan from 1995 to 2020.

Compared with Kyrgyzstan (as shown in Table 5), China had some obvious comparative advantages in rough-processed agricultural products such as canned vegetables and fruits (HS Code: 20), whereas Kyrgyzstan had obvious comparative advantages in royal jelly (HS Code: 0410).

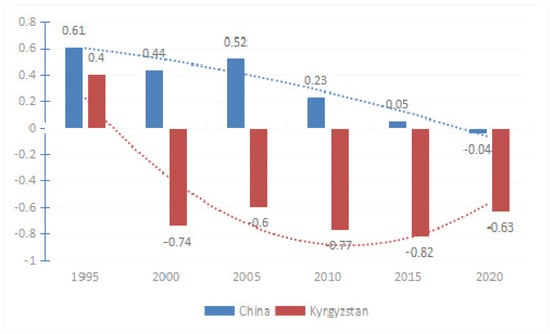

4.2.3. Deep-Processed Agricultural Products

From 1995 to 2020, the value of the NET trade index of deep-processed agricultural products between China and Kyrgyzstan showed a downward trend. The values of China’s NET trade index of deep-processed agricultural products dropped from 0.61 in 1995 to −0.04 in 2020 (Figure 3). However, it was always greater than 0 before 2020. In 1995 and 2005, the NET trade index was 0.61 and 0.52, respectively, indicating a high status in the global value chain; in 2000, 2010, and 2015, the NET trade index was 0.44, 0.23, and 0.05, respectively, suggesting that it had a certain status in the global value chain. The values of Kyrgyzstan’s net trade index of deep-processed agricultural products dropped from 0.4 in 1995 to the lowest value of −0.82 in 2015, and rose slightly to −0.63 in 2020, indicating a low status in the global value chain. In 2020, China’s position in the global value chain of deep-processed agricultural products was significantly higher than that of Kyrgyzstan.

Figure 3.

The evolving trend of the NET trade index values of deep-processed agricultural products between China and Kyrgyzstan from 1995 to 2020.

According to Table 6, it can be seen that the NET mean values of sausage and other meat products (HS Code: 02) in China’s deep-processed agricultural products was 0.96 from 1995 to 2020, which indicates a very high status in the global value chain. The average NET trade indices of grain products such as bread and biscuits (HS Code: 16) and beverages and wine vinegar (HS Code: 22) were 0.06 and 0.11, respectively, showing low competitiveness in the global agricultural product market. The average NET value of the food industry residues and animal feed was −0.29, indicating a low status in the global value chain. Among Kyrgyzstan’s deep-processed agricultural products, the NET trade values of three agricultural products, such as sausages and other meat products, food industry residues and animal feed, beverages, and fruit vinegar, dropped sharply. The NET trade value of meat products such as sausages dropped from 0.86 in 1995 to −0.51 in 2020. The NET trade value of food industry residues and animal feed dropped from 0.41 in 1995 to −0.97 in 2020, and the NET trade value of beverages and fruit vinegar decreased from 0.93 in 1995 to −0.80 in 2020 (as shown in Table 6). The status of food products in the global value chain was relatively low, with the average NET value from 1995 to 2020 standing at −0.43.

Table 6.

NET values and average values of related products in deep-processed agricultural products in China and Kyrgyzstan from 1995 to 2020.

Compared with Kyrgyzstan, China had obvious comparative advantages in deep-processed agricultural products such as meat products, grain products, beverages, and fruit vinegar, and the average value of the NET trade index was relatively high (see Table 6), indicating that China had strong deep-processing capabilities.

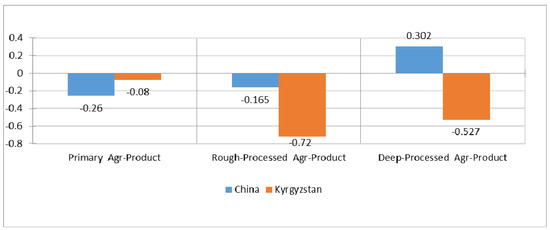

4.2.4. Overall Comparison of the Global Value Chain Status of Agricultural Products

From 1995 to 2020, the NET mean values of primary agricultural products, rough-processed agricultural products, and deep-processed agricultural products in China were −0.26, −0.165, and 0.302, respectively (Figure 4). A comparison across the three categories indicates that deep-processed agricultural products had the highest status in the global value chain, followed by rough-processed agricultural products and primary agricultural products. For Kyrgyzstan, the NET mean values for primary agricultural products, rough-processed agricultural products, and deep-processed agricultural products in 1995–2020 were −0.08, −0.72, and −0.527, respectively (Figure 4). Primary agricultural products had a slightly higher status than deep-processed agricultural products, which was followed by rough-processed agricultural products. In comparing the two countries, China had a far superior status to Kyrgyzstan in the global value chain of deep-processed agricultural products. In the category of rough-processed agricultural products, China’s status was slightly better than that of Kyrgyzstan. However, Kyrgyzstan outperformed China in primary agricultural products.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the NET mean values of agricultural products between China and Kyrgyzstan from 1995 to 2020.

5. Discussion

5.1. Primary Agricultural Products

From 1995 to 2020, China’s status in the global value chain of primary agricultural products continued to decline, and among them, grains and vegetable oilseeds declined sharply. Wang et al. (2022) found that from 1992 to 2020, vegetables and fruits were mainly exported, while the trade of corn, sorghum, and other grains and vegetable oilseeds such as rapeseed shifted from exportation to importation [44]. This finding is basically consistent with our research conclusions. As the most populous country in the world, China has made full use of domestic and foreign land resources to continuously import more primary agricultural products from the international market based on the premise of ensuring “basic self-sufficiency in grain and absolute security of rations (Wheat, Rice, etc.)” [45]. Since 1998, the Chinese government gradually canceled soybean import quotas [46]. In addition, as the income of Chinese residents continued to increase, the demand for high-end fruits in the global market continued to rise, and the number of imported fruit products continued to increase [47].

Although Kyrgyzstan’s status in the global value chain of primary agricultural products declined from 1995 to 2020, it still maintained a comparative advantage compared with China. Kyrgyzstan’s traditional advantageous industries are mainly animal husbandries such as grazing cattle, horses, and sheep [48]. Kyrgyzstan is one of the very few countries in the world where the environment is not polluted. Wild medicinal nectar plants grow everywhere in the grasslands deep in the mountains. The country produces “the best quality honey in the world” and served as a beekeeping base in the former Soviet Union before its independence [49]. For these reasons, although Kyrgyzstan’s position in the global value chain of primary agricultural products was also declining, it is slightly superior to China. In particular, Kyrgyzstan has obvious comparative advantages in primary agricultural products such as live animals, oilseed kernels and fruits, and honey.

5.2. Rough-Processed Agricultural Products

From 1995 to 2020, China’s status in the global value chain of rough-processed agricultural products declined slowly, especially meat, edible offal, and animal and vegetable oils. According to Wang et al. (2022), the imports of grain flour, pork, beef, and other edible meats and fats such as peanut oil and sunflower oil gradually and significantly increased from 1992 to 2020, while the export of vegetables and fruits products remained stable. This is consistent with the conclusion of this study. China’s economy has been developing rapidly, with per capita income levels increasing from RMB 4366 Yuan in 2000 to RMB 32,189 Yuan in 2020 [50]. People’s quality of life has greatly improved, and the demand for meat and oil products has continued to grow.

From 1995 to 2020, Kyrgyzstan had a very low status in the global value chain of rough-processed agricultural products such as meat and edible offal, as well as animal and vegetable oils. As early as July 2013, Kyrgyzstan’s then Minister of Agriculture, Uzakbaev, stated that the country’s agricultural product processing only accounted for 12% of the total output, and that the flour processing industry was extremely weak. Furthermore, the dairy product processing capacity only accounted for approximately 15% of the total milk output, while the vegetable processing capacity only accounted for 1% of the total output [51].

5.3. Deep-Processed Agricultural Products

Although China’s status in the global value chain of deep-processed agricultural products declined from 1995 to 2020, meat products and beverage fruit vinegar always maintained a strong competitive advantage in the global agricultural product market. The research of Wang et al. (2022) also shows that the export of meat, fish and other aquatic animal products, grain, and flour products remained stable over time. In recent years, China’s agricultural product processing technology and equipment have been continuously improved, and the application of key technologies and equipment such as automation, intelligence, and digitization has promoted the rapid development of the entire domestic agricultural product processing industry (Liu, X.Y. et al., 2022) [52].

From 1995 to 2020, Kyrgyzstan’s status in the global value chain of deep-processed agricultural products remained at a relatively low level. After Kyrgyzstan’s accession to the WTO in 1998, as the degree of openness continued to increase, three agricultural products such as sausages, food industry residues and animal feed, and beverages and fruit vinegar were greatly affected. As early as 2008, Kyrgyzstan had hoped to promote the development of its agricultural product processing industry by exempting the profit tax of the food industry and the agricultural product processing industry as well as the value-added tax of agricultural machinery suppliers [53]. However, the Kyrgyz government failed to achieve its goal of continuously improving its domestic agricultural product processing capacity. Consequently, its status in the global value chain of deep-processed agricultural products has been far lower than that of China.

5.4. Overall Comparison between the Two Countries

China is a country with a large population and limited land resources. As a result, China attaches great importance to the issue of food security and has been committed to improving agricultural production efficiency by improving agricultural production technology, promoting water-saving irrigation, and increasing the breeding of improved varieties to meet its people’s demands for primary agricultural products [54]. In the long run, China needs to properly import green and organic primary agricultural products to supplement domestic supply. Due to Kyrgyzstan’s good natural environment and long-standing tradition of animal husbandry, live animals such as cattle and sheep and primary agricultural products such as honey and rapeseed may be good candidates due to their high quality.

As the second largest economy in the world, China has obvious capital advantages in R&D investment in agricultural product processing technology, processing equipment, and agricultural machinery. The processing capacity of China’s agricultural products has increased significantly in the past 20 years. By 2020, the conversion rate of agricultural product processing had reached 68%. The ratio of the agricultural product processing industry to the total agricultural output value had reached 2.4:1. It is expected that the conversion rate of agricultural product processing will further increase to 75% by 2025 (Liu, X.Y. et al., 2022). These advantages that China has as a large and powerful country are why it has some obvious comparative advantages over Kyrgyzstan in deep-processed and rough-processed agricultural products.

6. Conclusions and Policy Suggestions

This paper divided agricultural products into primary agricultural products, rough-processed agricultural products, and deep-processed agricultural products according to the degree of processing. Moreover, the NET trade index was used to measure the evolving status of agricultural products in the global value chain since the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Kyrgyzstan from 1995 to 2020. The research results showed that (a) the status of primary agricultural products in both countries in the global value chain showed a continuous decline, with Kyrgyzstan performing slightly better than China. In comparing the two countries, Kyrgyzstan had obvious competitive advantages in primary agricultural products such as live animals, oilseed kernels and fruits, and honey; (b) the status in the global value chain of rough-processed agricultural products in both countries was slowly declining, while Kyrgyzstan dropped to a very low level. Comparatively speaking, China had obvious competitive advantages in canned and other vegetable and fruit products, while Kyrgyzstan had obvious competitive advantages in royal jelly; (c) China had a good foundation in the global value chain of deep-processed agricultural products, while Kyrgyzstan had a low status. In comparison, China had obvious competitive advantages in deep-processed agricultural products such as meat products, grain products, beverages, and fruit vinegar; and (d) China’s agricultural product processing capacity was relatively high, significantly better than that of Kyrgyzstan.

Based on these findings, this paper puts forward the following suggestions for the sustainable development of agricultural cooperation between China and Kyrgyzstan: First, China and Kyrgyzstan should strengthen agricultural technology exchanges and cooperation, especially in the fields of grain planting and animal husbandry, to promote the move towards the high end of the value chain. The second is to combine their respective comparative advantages to continuously expand the trade scale and types of high-quality agricultural products between China and Kyrgyzstan. The third is to encourage Chinese agricultural processing enterprises to invest in Kyrgyzstan or export agricultural processing equipment to Kyrgyzstan, continuously improve the processing capacity of Kyrgyzstan’s agricultural products, and achieve mutual benefit and win–win results.

A few insights can be gleaned from the findings of this study. If a country opens up to the outside world, various commodities including agricultural products will inevitably face competition in the global market. To achieve sustainable development, a country must be firmly rooted in its own resource endowment and comparative advantages and strengthen international cooperation in areas such as resources, capital, and technology. Only by doing so can it achieve mutual benefit and win–win results and continuously improve the international competitiveness of its commodities.

This article serves as a valuable supplement to the current body of research on agricultural international cooperation. However, due to certain limitations in data and other aspects, the indicator system employed to measure the global value chain status of agricultural products may not be fully comprehensive. Additionally, the appropriate econometric methods may not have been exhaustively utilized, and the analysis and discussion may not have delved deeply enough into the topic. Nonetheless, it is hoped that future research will lead to continuous improvement, particularly in the application of econometric methods.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Z. and Z.N.; methodology, X.Z. and W.Z.; formal analysis, X.Z.; resources, X.Z.; data curation, X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Z.; writing—review and editing, X.Z. and W.Z.; supervision, Z.N.; project administration, X.Z. and Z.N.; funding acquisition, X.Z. and Z.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Social Science Fund Program of Shaanxi Province, China (Grant Number: 2021D011), the Soft Science Research Program of Shaanxi Province, China (Grant Number: 2022KRM132), the Scientific Research Support Program Project Fund at the Xi’an University of Finance and Economics (Grant Number: 21FCZD01), and the Fund Program of The Youth Innovation Team of Shaanxi Universities (The Youth Innovation Team of Digital Village Development in Western China).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available at: https://comtrade.un.org/data (United Nations Commodity Trade Statistics Database, accessed on 1 September 2022) and https://www.fao.org/faostat/zh/#data/TM (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) database, accessed on 1 September 2022).

Acknowledgments

This study also received support from the China (Xi’an) Institute for Silk Road Research at the Xi’an University of Finance and Economics, Shaanxi.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Li, Q.; Khan, H.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, L.; Huang, K. The Impact of the Belt and Road Initiative on Corporate Excessive Debt Mechanism: Evidence from Difference-in-Difference Equation Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.Z. China and the Five Central Asian Countries: Join Hands with the New Silk Road. China Pictorial. Available online: http://www.rmhb.com.cn/zt/ydyl/201907/t20190710_800173165.html (accessed on 10 July 2019).

- Ma, Z.Q. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of China: The 30th Anniversary of the Establishment of Diplomatic Relations between China and the Five Central Asian Countries, Both Parties Have Become a Model for Building a New Type of International Relations. China Youth Daily. Available online: https://www.360kuai.com/pc/95f245987147b3504?cota=3&kuai_so=1&tj_url=so_vip&sign=360_57c3bbd1&refer_scene=so_1 (accessed on 4 January 2019).

- Gong, Y.K. Agricultural cooperation has yielded fruitful results between China and the five Central Asian countries on the 30th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations. Farmers’s Daily, 21 June 2022.

- Zheng, G.F. New trends, problems and paths in the development of agricultural trade between China and the five Central Asian countries under the ‘Belt and Road’ initiative. J. Inn. Mong. Univ. Financ. Econ. 2021, 1, 102–107. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, Z.K.; Zhang, X.H.; Su, S.S.; Zhang, W.J.; Jing, Q.L.; Amina, T.K. Agriculture of Kyrgyzstan: 1991–2021; China Financia-l & Economic Press: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gereffi, G. International Trade and Industrial Upgrading in the Apparel Commodity Chains. J. Int. Econ. 1999, 48, 37–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, D.; Chanda, R.; Hermida, C.D.; Santos, A.M.; Bittencourt, M.V. Does International Fragmentation of Production and Global Value Chains Participation Affect the Long-run Economic Growth? Foreign Trade Rev. 2022, 57, 367–389. [Google Scholar]

- Ningaye, P.; Tchounga, A.; Kenfack, G.F. The Effects of Global Value Chain Participation on Current Account Balances in African Economies: Does it Matter Being a Landlocked Country? An Empirical Review. J. Econ. Manag. Trade 2021, 68, 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Shoot, P.K. The Relative Sophistication and Revealed Comparative Exports. Econ. Policy 2008, 53, 5–49. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.C.; Noguera, G. Accounting for Intermadiates: Production and Trade in Value Added. J. Int. Econ. 2012, 86, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasz, B.; Anna, B. The Importance of Global Value Chains in Developing Countries’ Agricultural Trade Development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1389. [Google Scholar]

- Fadiji, A.E.; Mthiyane, D.M.; Onwudiwe, D.C.; Babalola, O.O. Harnessing the Known and Unknown Impact of Nanotechnology on Enhancing Food Security and Reducing Postharvest Losses: Constraints and Future Prospects. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.H.; Gao, Y.; Wei, T.Y. The Impact of Trade Barrier Reductions on Global Value Chains for Agricultural Products in China and Countries along the ‘Belt and Road’. World Trade Rev. 2022, 21, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, D.T.; Pham, X.H. Regional Economic Integration and Risks for Agricultural Products: A Banana Value Chain Analysis in Huong Hoa District, Quang Tri Province. Int. J. Appl. Logist. 2020, 10, 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.; Kwon, O.S. An Analysis of Global Value Chain of Agricultural and Food Products. Korean Agric. Econ. Assoc. 2018, 59, 61–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zeng, F.L.; Wu, P. Production and Trade of Agricultural Products in GVC: Features, Shackles and Countermeasures. Int. Bus. Stud. 2016, 5, 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X. Study on the agricultural industry chain integration of China and ASEAN. World Geogr. Stud. 2017, 12, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Tan, L.W. Research on the upgrading of China’s agricultural product processing industry based on global value chain governance: Take China’s Xinjiang tomato industry as an example. World Agric. 2008, 8, 20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.Q.; Zhou, L. Comparative Advantage, FDI and International Competitiveness of China’s Agricultural Products Industry. Int. Trade Issues 2011, 12, 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ersin, Ö.Ö.; Bildirici, M. The Effects of Inflation, Openness to Trade and Value Added in Production on Economic Growth in Transition Economies. Int. Conf. Eurasian Econ. 2017, 10, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.J. Comparison of actual and theoretical values of agricultural trade between China and Central Asia. J. Agric. Econ. 2021, 8, 122–124. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L.; Cao, C.; Zhao, X.H. Research on the scale, structure and quality of China′ s agricultural exports to five countries in Central Asia—Based on the Belt and Road initiative. J. Price 2021, 8, 48–59. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M.; Xu, C.Y.; Wang, F.T.; Xiong, L.; Zhou, K. Research on the Measurement and Influencing Factors of Implicit Water Resources in Import and Export Trade from the Perspective of Global Value Chains. Water 2021, 13, 1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halit, H.; Abdullah, A. The Impact of Global Value Chain Participation on Sectoral Growth and Productivity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4848. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Y.F.; Fang, R.N.; Wang, D. Measurement and Characteristics of the Integration of China’s Trade in Services into Digital Global Value Chain. China Financ. Econ. Rev. 2021, 10, 44–65. [Google Scholar]

- Alec, M.; Sardar, M.N. Measuring collaboration effectiveness in globalised supply networks: A data envelopment analysis application. Int. J. Logist. Econ. Glob. 2007, 1, 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Zeng, J.N.; Han, Y.H.; Luo, X.F. Analysis on the Evolution Characteristics of China’s Manufacturing Industry Structure—Based on the Perspective of Global Value Chain. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 563, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, J.X. Positioning of China’s Equipment Manufacturing Industry Based on GVCs. Ind. Econ. Rev. 2018, 1, 118–131. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.D.; Luo, J.L. Global value chain status analysis and regional industrial chain construction based on the ‘Belt and Road’. Ind. Econ. 2017, 9, 45–46. [Google Scholar]

- Iapadre, P.L. Measuring international specialization. Int. Adv. Econ. Res. 2001, 7, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N. Agricultural Cooperation of Shanghai Cooperation Organization and Food Security in China; Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.J.; Xiao, H.F. Influencing Factors in Agricultural Products Trade Fluctuation between China and SCO Member Countries in the Context of “Belt and Road” Initiative. J. Xinjiang Univ. 2021, 1, 48–57. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.R.; Abula, B.W.; Chen, J.K. Trade Potentials of Cotton Products Between China and the Countries Along the Silk Road Economic Belt. J. Xinjiang Univ. 2021, 11, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Xu, Y.Y.; Sun, S.K.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y. Analysis of the Coupling Characteristics of Water Resources and Food Security: The Case of Northwest China. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elena, K.; Lenka, R.; Irena, B.; Lubos, S. Czech Comparative Advantage in Agricultural Trade with Regard to EU-27: Main Developmental Trends and Peculiarities. Agriculture 2022, 12, 217. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.B.; Chen, T. Analysis of the structure and comparative advantage of China’s agricultural exports to Kazakhstan. Agric. Econ. Issues 2009, 3, 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Vukadinovic, P.; Damnjanovic, A.; Dimitrijevic, L. Analysis of the sales and incomes between different categories of agricultural products. Ekon. Poljopr. 2017, 64, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Mei, X.F. Estimation of the distribution of provinces and regions on the impact of China’s WTO accession to agriculture. Econ. Res. 2001, 4, 67–73. [Google Scholar]

- Vukadinovic, P.; Damnjanovic, A.; Krstic, R.J. From Commoditisation to De-commoditisation and Back Again: Discussing the Role of Sustainability Standards for Agricultural Products. Ekon. Poljopr. 2017, 64, 671–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regme, A.M.; Gehlhar, J.; Wainio, P.; Vollrath, T.; Johnston, P.; Kathuria, N. Market Access for High-Value Foods; Economic Research Service USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- UN Comtrade Database. Available online: https://comtrade.un.org/data (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/zh/#data/TM (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Wang, N.; Cheng, C.X.; Ling, G. Evolving Agricultural Trade Structure and Its Impact on Food Security in China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2022, 10, 2599–2615. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B.C. Prospects of Several Major Issues in International Agricultural Cooperation in 14th Five-Year Plan. J. Agric. Econ. Issues 2020, 10, 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, C.; Jing, Y.S.; Zhang, X.F. To Analyse on the Compensation to the Industry of Soybean by Chinese Government Based on the Game Theory. J. Value Eng. 2008, 8, 50–53. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, F.; Sun, Y. Calculation and discrimination of China’s fruit import market power under the background of “One Belt and One Road”. J. Rural Econ. Technol. 2021, 9, 179–183. [Google Scholar]

- Otunchieva, A.; Borbodev, J.; Ploeger, A. The Transformation of Food Culture on the Case of Kyrgyz Nomads—A Historical Overvies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspersen, L. Utilising the Nutritional Potential and Secondary Plant Compounds of Neglected Fruit Trees and Other Plant Species of the Walnut Fruit Forests in Kyrgyzstan. In Proceedings of the Tropentag, Bonn, Germany, 20–22 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Available online: https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=C01 (accessed on 17 February 2023).

- Chinese Commercial Counsellor. Kyrgyzstan Wants to Develop Its Agricultural Processing Industry. Ministry of Commerce of China. Available online: http://kg.mofcom.gov.cn/article/jgjjqk/ny/201307/20130700187191.shtml (accessed on 4 July 2013).

- Liu, X.Y.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Sun, J.; Zhao, D.; Sun, X.; Sun, B.; He, Y. Development Status and Countermeasures of Agricultural Products Processing Industry in China. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2022, 10, 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, W. Kyrgyzstan has stepped up efforts to develop agricultural processing industries. J. Centr. Asian Inf. 2009, 2, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Zang, X.Y.; Li, T.X. China’s Food Security Risks and Prevention Strategy under the New Development Pattern. J. Chin. Rural Econ. 2021, 9, 2–21. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).