Abstract

China has become more aware of the negative environmental impact caused by its economic expansion and fast-paced development. Therefore, the country mainly focuses on sustainable development and green finance. To evaluate the environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors and policy options for green finance investment decisions in China, the fuzzy analytical hierarchy process (AHP) and fuzzy decision-making trial and evaluation laboratory (DEMATEL) techniques are employed. The fuzzy AHP method identifies and analyzes the most significant ESG factors and sub-sub-factors to comprehensively understand sustainable investment in China. Furthermore, this study uses the fuzzy DEMATEL method to prioritize the main policy options for advancing sustainable development and green finance investment decisions in China. The fuzzy AHP method shows that the environmental factor (ESG1) is the most significant factor for green finance investment decisions in China, followed by the governance (ESG3) and social factors (ESG2). The fuzzy DEMATEL method results revealed that supporting green finance innovation and development (P1) is the highest priority, followed by encouraging social responsibility and community engagement (P4) and developing and enforcing environmental regulations (P2). The study’s findings will significantly benefit investors and decision-makers who wish to promote sustainable development and make decisions regarding green financing. The study recommends that investors and policy makers concentrate their resources and efforts on the most crucial ESG factors and policies to build sustainability and resilience in the country.

1. Introduction

Sustainable development was developed in the Brundtland Report by the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) in 1987 [1]. The definition of sustainable development, as stated in the report, is that it is development that addresses current needs while ensuring that future generations can meet their own needs. As the global community has realized the significance of preserving the environment and ensuring that economic progress is socially and environmentally sustainable, sustainable development has gained considerable prominence [2]. In addition, the sustainable development concept was first mentioned in Schumacher’s 1973 book “Small is Beautiful” [3].

Green finance supports sustainable development by directing investments toward environmentally friendly initiatives and enterprises. Green finance encompasses various financial products and services, such as green bonds, financing, and insurance, that promote sustainable investments [4]. Green finance aims to mobilize private capital for investments that generate financial returns while benefiting the environment and society [5,6]. Green finance is significant in terms of climate change, since it may assist in financing the transition to a low-carbon economy. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicts that the clean energy sector alone will require roughly USD 2.4 trillion annually through 2035 to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels [7,8]. This estimate is based on limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, and the energy sector must remain stable. Green financing, necessary in making investments possible, can significantly help ease the transition to low-carbon technologies and other low-carbon practices, such as energy efficiency and renewable energy [9].

China is widely regarded as a giant economic hub and has promoted environmentally responsible financing and sustainable economic development [10]. To stimulate renewable energy consumption sources, the federal government has implemented legislation and begun programs to reduce carbon emissions, promote sustainable agricultural and forestry practices, and encourage the reduction in carbon emissions [11]. By issuing green bonds, establishing green finance institutions, and adopting legislation, they have made it easier for people to invest in environmentally friendly businesses. China committed in 2020 to reach peak CO2 by 2030 and to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060 [12,13]. There are still roadblocks, such as the lack of public and investor awareness of sustainable development and the absence of clearly defined guidelines and rules for evaluating investments’ environmental and social impacts. Evaluating investments’ impact on the economy lacks clear guidelines and rules [14]. Traditional finance continues to impact the Chinese financial system significantly, so there is a need for increased innovation and investment in green financial products and services [15,16]. China has the potential to advance green finance and sustainable development despite these obstacles due to its expanding economy, substantial investments in technology and infrastructure, and a favorable environment for green financing [17]. Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) regulations and factors must be evaluated to promote sustainable development and green finance in China. ESG variables and regulations are significant indicators of investment sustainability and can aid investors and governments in making more informed decisions to advance sustainable development.

In the case of sustainable development and green finance in China, the fuzzy analytical hierarchy process (AHP) and the fuzzy decision-making trial and evaluation laboratory (DEMATEL) are two ways to evaluate ESG factors and policy options [18]. Fuzzy DEMATEL shows how the factors that go into making a choice are related [19]. In contrast, fuzzy AHP utilizes the AHP and the fuzzy DEMATEL to identify and assess the most critical elements that influence green finance investment decisions in China. Both facilities are at the fuzzy DEMATEL. With this information, one can make more informed judgments about sustainable growth. The current investigation into the ESG elements and regulations controlling green finance company decisions in China uses fuzzy AHP and fuzzy DEMATEL methodologies.

The paper’s first section explores sustainable development and emphasizes the critical function that green finance plays in achieving this goal. After that, it offers a comprehensive review of environmentally responsible financing. The following paragraphs will discuss China’s challenges and opportunities for green financing and sustainable growth. The fundamental purpose of this investigation is to summarize how fuzzy AHP and DEMATEL methodologies may analyze ESG elements and regulations for investment decision making in green finance in China. This study contributes to what is already known about environmentally responsible funding and sustainable economic development in China. This study aims to help China make sustainable business decisions by examining how fuzzy AHP and DEMATEL methods can evaluate ESG factors and laws. Lastly, this paper will discuss the most important results and offer ways for China to support green finance and sustainable growth. This study aims to help China create a sustainable financial system that is good for the environment and helps the country move towards a low-carbon economy while balancing social welfare, environmental protection, and economic development. China prioritizes promoting sustainable development and green financing to balance economic growth, environmental protection, and social welfare. Assessing ESG factors and policies is vital to assisting decision-makers in evaluating their investment decisions on social and environmental issues. This paper aims to establish a more environmentally benign and sustainable financial system in China that supports the transition to a low-carbon economy and the coexistence of social welfare, environmental protection, and economic development.

2. Literature Review

An overview of the literature on sustainable development, green finance, and ESG elements and policies in China is given in this review. An outline of sustainable development and its connection to green finance will be given at the outset of the assessment. The assessment will examine the opportunities and challenges of fostering sustainable development and green financing in China. The review will conclude by summarizing the literature on applying fuzzy multi-criteria decision making (MCDM) to evaluate ESG aspects and regulations for green finance investment decisions in China [20,21,22].

2.1. Sustainable Development and Green Finance

The term “sustainable development” can be understood in various ways, but in essence, it means development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the potential of future generations’ needs [23]. According to [24], to ensure that the requirements of both the present and future generations are met, sustainable development involves striking a balance between economic growth, environmental conservation, and social welfare. A study by [25] argues that by investing in environmentally friendly projects and businesses, green finance is a key tool that may support sustainable development. Another study by [26] focuses on green finance and describes various financial services and products that promote sustainable investment, such as green bonds, loans, and insurance. Its objective is to encourage environmentally sustainable investments. Green finance aims to mobilize private resources for investments that produce financial returns while positively impacting the environment and society [27]. Green finance plays a crucial role in the fight against climate change, as it can provide funding for the transition towards a low-carbon economy. Sustainable development and green finance work together in a strategic relationship, with green finance playing a key role in allocating funds to initiatives that prioritize social responsibility and the environment. The idea of sustainable development is supported by this cooperative effort, which harnesses economic progress to successfully integrate environmental preservation and societal well-being [28]. By striking a balance that takes into account both the requirements of the present and the needs of the future, such collaboration emphasizes how important it is for economic activity to remain viable across generations. Furthermore, the overlap between green finance and sustainable development extends to inclusive growth methods, creating job opportunities, fostering community involvement, and promoting ethical company practices. This partnership simultaneously addresses many hazards related to societal inequality and environmental degradation, enhancing resilience in both the social and economic spheres. This alliance advances global economic success, environmental sustainability, and social equality in accordance with governmental laws and international frameworks [29].

2.2. Challenges and Opportunities for Green Finance in China

China has made remarkable progress in supporting sustainable development and green finance in recent years, but significant challenges persist [30,31]. Insufficient knowledge and comprehension of sustainable development among investors and the general public is a concern. Many investors prioritize immediate financial gains over long-term sustainability considerations [32,33,34]. This strategy could result in investments in projects that negatively affect the surrounding environment. Due to the lack of well-defined criteria and procedures for determining an investment’s economic, social, and environmental impact, it may be difficult for investors to evaluate the viability of investment prospects. Conventional finance is pervasive in China’s economy, which presents yet another obstacle for the country’s financial system to overcome. Despite the recent growth that it has experienced, green finance still only represents a very insignificant proportion of the overall value of all financial assets [35,36]. This can be primarily ascribed to the absence of investment and innovation in environmentally friendly financial services and products and the absence of legal frameworks and incentives that support environmentally friendly financing. Despite these obstacles, China holds a significant amount of potential for the advancement of environmentally friendly finance as well as environmentally friendly growth [37]. China provides a favorable setting for environmentally friendly financing and sustainable development due to the size and growth of the economy and the country’s significant investments in technology and infrastructure. China’s dedication to sustainable development has set the stage for the country to emerge as a leader in this field on a global level. The country’s efforts to promote green financing, such as by issuing green bonds, establishing green finance funds, and implementing regulatory laws to encourage sustainable investment, indicate its commitment to the cause.

2.3. Assessing ESG Factors and Policies Using Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM)

Evaluating ESG factors and regulations is the first step in promoting sustainable development and green finance in China. ESG factors and regulations are gradually recognized as significant indicators of investment sustainability and tools for evaluating investment options’ social and environmental impacts [38]. It is widely thought that ESG problems can negatively influence an investment’s growth and sustainability. Biodiversity loss, natural resource depletion, and pollution are all considered environmental concerns [39]. Social aspects include labor laws, human rights, interpersonal relationships, diversity, and inclusion. Transparency, accountability, and ethical behavior are only some of the characteristics of governance.

In the context of sustainable development and green finance, fuzzy AHP and fuzzy DEMATEL applications are widely studied in China [40,41,42]. In a particular study, ref. [43] utilized fuzzy AHP to evaluate the ESG components of Chinese banks’ green bonds. The report highlights that social effects, governance, and the environmental impact were the most crucial ESG elements. Although the overall ESG performance of Chinese green bonds was deemed acceptable, the study uncovered an opportunity for improvement in specific areas such as reporting and disclosure. Fuzzy AHP and fuzzy DEMATEL techniques were utilized in a separate study by [44] to assess the influence of ESG elements on the performance of Chinese green funds. The survey revealed that environmental impact, governance, and risk management were the most essential ESG criteria.

In addition, the research discovered constructive relationships between ESG standards and the financial returns of green funds. In a related but separate analysis, ref. [45] utilized fuzzy AHP and fuzzy DEMATEL to assess the impact of ESG factors on the performance of Chinese green bonds. The report indicated that social impact was the ESG factor with the most significant significance, followed by governance and environmental impact. The study revealed the existence of a positive correlation between the financial success of green bonds and their ESG performance. The study by [42] employed fuzzy AHP and fuzzy DEMATEL techniques to assess the long-term sustainability of Chinese publicly traded firms. The study reveals that social effect, governance, and environmental impact are the ESG aspects that hold the most weight regarding their positive significance, ranked in descending order. In addition to that, a robust correlation exists between the public sustainability of publicly traded companies and finance performance.

A study by [46] examined the effect of ESG variables on active renewable energy enterprises in China. In this study, fuzzy AHP and fuzzy DEMATEL were utilized to evaluate the effect of these aspects. Another study shows that the ESG aspects with the most significant positive impact were social, governance, and environmental impacts. The study disclosed a positively significant link between the financial performance of companies that deal with renewable energy and that of those dealing with ESG. Specifically, the study found a positive correlation between these two factors. The findings of these studies emphasize that fuzzy AHP and fuzzy DEMATEL have become valuable tools for assessing the ESG aspects and policies of green financing investments in China. These studies point to a positive connection between the ESG performance of green finance investments and the financial performance of such investments [47]. Therefore, China needs to prioritize promoting sustainable development and green financing. This is considered to be evident, because the country hosts over 50 percent of the world’s most polluted cities. The pollution has led to severe health problems for citizens and impacted the environment. China must focus on sustainable development and green financing to avoid further damage.

There is a research gap in the thorough evaluation of ESG factors and policy options for guiding green finance investment decisions in the context of China’s dynamic economic landscape, despite the increased awareness and attention on sustainable development and green finance. Although prior research has emphasized the importance of ESG issues, there has not been a thorough investigation using cutting-edge methodology like the fuzzy AHP and fuzzy DEMATEL procedures. By delivering a structured and comprehensive examination of ESG determinants and policy options, this study attempts to close this gap and provide useful information for sustainable investment choices in China’s financial sector. It will be crucial to address this research gap to advance green finance mechanisms and sustainable development in China and provide a more complete and valuable understanding of the variables influencing green finance investment choices in the country.

3. ESG Factors and Policy Options for Green Finance Investment Decisions

3.1. Identified ESG Factors and Subfactors

In this study, several key ESG factors have been identified that can affect an investment’s performance and sustainability. These factors are further subdivided into subfactors to give a more thorough understanding of the particular problems that impact sustainable investing. Table 1 provides the ESG factors and subfactors of this study.

Table 1.

The identified factors and subfactors for this study.

ESG factors and their subfactors offer a comprehensive framework for assessing investment options’ sustainability. By considering these variables, investors can make more educated investment decisions that support sustainable development and green finance.

3.2. Identified Policy Options

The different key policy options have been identified based on the ESG factors and subfactors. These policy options can help implement sustainable and green finance investment decisions in the context of China. Table 2 provides the main policy options used in this study.

Table 2.

The identified policy options of this study.

4. Research Methods

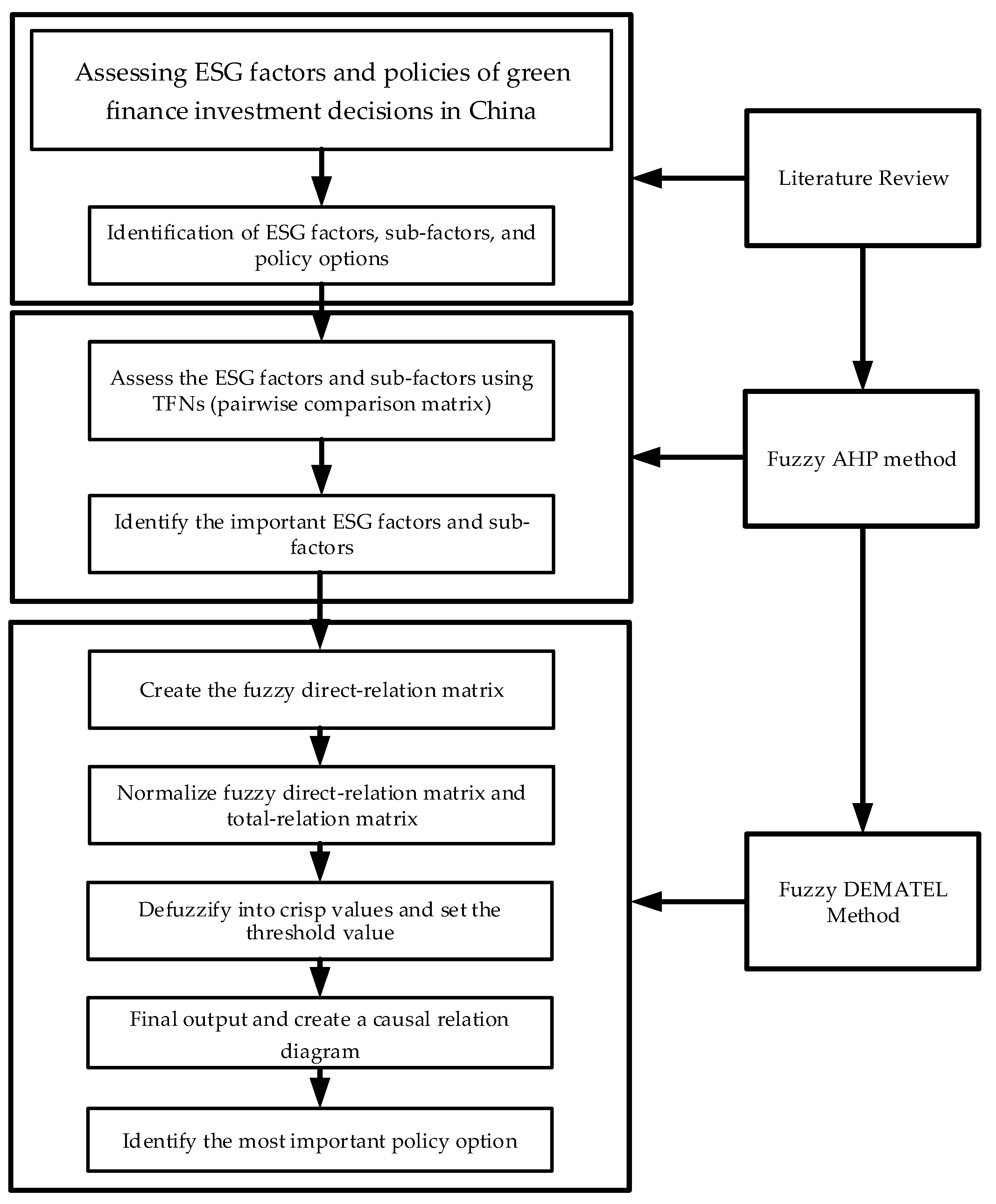

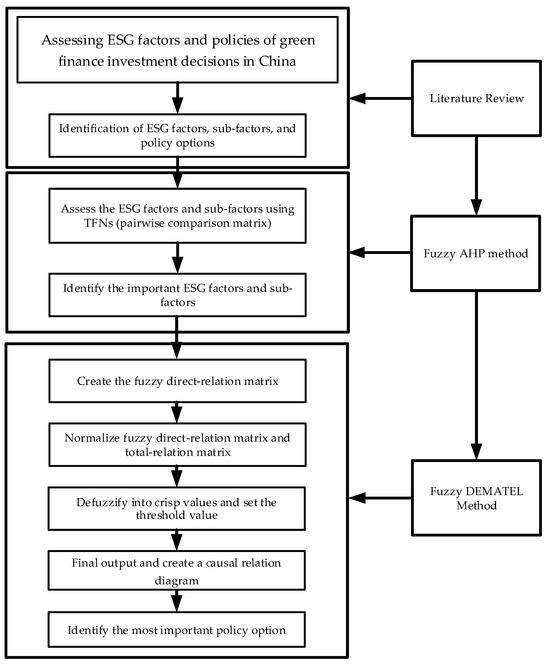

In this study, the fuzzy AHP and fuzzy DEMATEL methods has been used for evaluating ESG factors and policies for green finance investment decisions in China. First, a thorough literature review was conducted to identify the key factors and policy options. Secondly, the fuzzy AHP method determines the relative importance of the selected ESG factors and subfactors. This entails constructing a hierarchical structure of the factors and subfactors, allocating relative weights to every issue and sub-aspect, and using fuzzy logic to account for uncertainty and imprecision within the facts. In the final stage, the fuzzy DEMATEL approach was used to rank the vital policy options for making investment decisions regarding green finance in China. Figure 1 shows the research framework of this study.

Figure 1.

The research flowchart of this study.

4.1. The Fuzzy AHP Method

The Fuzzy AHP technique uses fuzzy numbers to assign values to criteria and sub-criteria, allowing decision-makers to consider uncertain and obscure information [62,63]. This leads to better decision making in complex and uncertain scenarios. The triangular fuzzy numbers (TFNs) scale is explained in detail in Table 3.

Table 3.

TFNs Scale.

The Fuzzy AHP process involves several steps [64]:

Step 1. Triangular fuzzy matrix (TFM):

Then, the first TFM is created with the middle TFM:

Next, the second TFM is developed for the upper and lower bounds of the TFN by employing a geometrical approach:

Step 2. Create and compute the weight vector and lambda max using the Saaty method.

Step 3. Create a consistency index (CI):

Step 4: Create the consistency ratio (CR):

The Fuzzy AHP approach gives a grounded and systematic technique for assessing the factors and subfactors. The method can control the vagueness and imprecision of choice-making approaches, allowing stakeholders to make well-informed choices.

4.2. The Fuzzy DEMATEL Method

In this study, the fuzzy DEMATEL method is employed to assess the interrelationships among the policy options [65]. The process requires the development of a direct-relation matrix and an indirect-relation matrix, an evaluation of the impact levels of the policy options, and the identification of the driving and dependent factors of the system [66]. The procedure of the fuzzy DEMATEL method comprises the following steps:

Step 1: Generate the fuzzy direct-relation matrix.

To determine the model of the relationships between criteria, an matrix is created. Each element in a row affects the element in each matrix column. This effect can be expressed as a fuzzy number. When multiple experts are involved, each expert needs to complete the matrix. To generate the direct relation matrix z, we calculate the arithmetic mean of all the experts’ opinions.

Table 4 represents the direct relation matrix, equivalent to the pairwise comparison matrix provided by the experts.

Table 4.

The direct relation matrix.

Table 5 shows the fuzzy scale used in the model.

Table 5.

The fuzzy scale used in this study.

Step 2: Normalize the fuzzy direct-relation matrix.

The formula for obtaining the normalized fuzzy direct-relation matrix is as follows:

where

Table 6 shows the fuzzy normalized direct-relation matrix.

Table 6.

The fuzzy normalized direct-relation matrix.

Step 3: Calculate the fuzzy total-relation matrix.

The third step involves the calculation of the fuzzy total-relation matrix using the formula provided below:

Each element of the fuzzy total-relation matrix can be expressed as , and it can be calculated as follows:

To normalize a matrix, we first calculate its inverse. Then, we subtract the inverse from matrix I. The resulting matrix is multiplied by the normalized matrix as the final step. The matrix representing the fuzzy direct relation is reported in Table 7.

Table 7.

The fuzzy total-relation matrix.

Step 4: Defuzzify into crisp values.

Opricovic and Tzeng proposed the CFCS method for obtaining a crisp value of the total-relation matrix. The method follows these steps:

So that

The process of calculating the upper and lower bounds of normalized values is taking place here, and

The crisp values are what the CFCS algorithm produces as the output.

The process involves calculating the total normalized crisp values to get a result. Table 8 shows the crisp total-relation matrix.

Table 8.

The crisp total-relation matrix.

Step 5: Set the threshold value.

The first step towards determining the threshold value is to calculate the internal relations matrix. This is followed by the presentation of the network relationship map, also known as the NRM, which displays only those connections whose matrix T values exceed the specified minimum. To determine the threshold intensity, we compute the average of the values in matrix T, ignoring any values that are less than the threshold value. This approach does not consider the prior causal link. According to this study, the critical value is 0.5210. All T matrix values below this threshold have been set to zero, and the causal relation has not been considered. Table 9 displays the model of significant relations.

Table 9.

Crisp matrix of total direct relations with threshold.

Step 6. Determine the final output and create a causal relation diagram.

In the next step, we need to determine the sum of each row and column in , which was obtained in step 4. To calculate the sum of rows, we will denote it as , and to calculate the sum of columns, we will denote it as . The calculations for and are as follows:

After that, the values for and can be determined using and . indicates the significance level of factor in the whole system, while represents the net impact that factor has on the system.

Step 7: Interpret the results.

Overall, the methodology for evaluating ESG factors and policies for green finance investment decisions in China using the fuzzy AHP and fuzzy DEMATEL is a rigorous and all-encompassing method that can assist in identifying the most significant ESG factors and subfactors, assessing their interrelationships, and making recommendations for improving ESG performance in the context of sustainable development and green finance.

4.3. Experts Involved in This Study

In general, it is common for research studies to involve a team of experts with different backgrounds and areas of expertise. These experts may come from various fields, such as academia, industry, non-governmental organizations, or government agencies, depending on the focus of the study. For this particular study on the prioritization of ESG factors for green finance investment decisions in China using fuzzy AHP and fuzzy DEMATEL, the authors likely have expertise in sustainability research, finance, and/or economics. The study might have been conducted as part of their academic or professional work, and they could have consulted with other experts or stakeholders to inform their research. Experts from diverse backgrounds must get involved to comprehensively analyze related issues, because their findings and rigorous analysis would be valuable for policy making.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Results of Fuzzy AHP (Main Factors)

This research article used the fuzzy AHP method to analyze the ESSG factor and subfactors for green finance investment in China. The ranking of ESG factors is displayed in Table 10. The fuzzy AHP analysis has revealed that the environmental factors (ESG1) hold the top rank, followed by the governance factors (ESG3) with the second-highest rank, while the social factors (ESG2) have been ranked the lowest. Considering the ranking mechanism, environmental factors (ESG1) should be prioritized when making decisions regarding investments in green finance in China. These factors may include climate change, resource depletion, increased pollution, and other environmental concerns. This reflects China’s expanding awareness and emphasis on environmental sustainability and the imperative need to combat climate change. The second-highest classification of governance factors, or ESG3, indicates that investors should also consider the corporate governance structure and practices of the companies they invest in. This category of factors may include concerns regarding transparency, accountability, and aligning the company’s management practices with sustainable development objectives. Finally, the social aspect (ESG2) received the third-highest ranking, suggesting that despite these factors’ importance, they may not be as important as environmental and governance concerns when deciding how to engage in green finance in China. Issues about labor practices, human rights, and community relations are possible social factors.

Table 10.

The ranking of ESG factors.

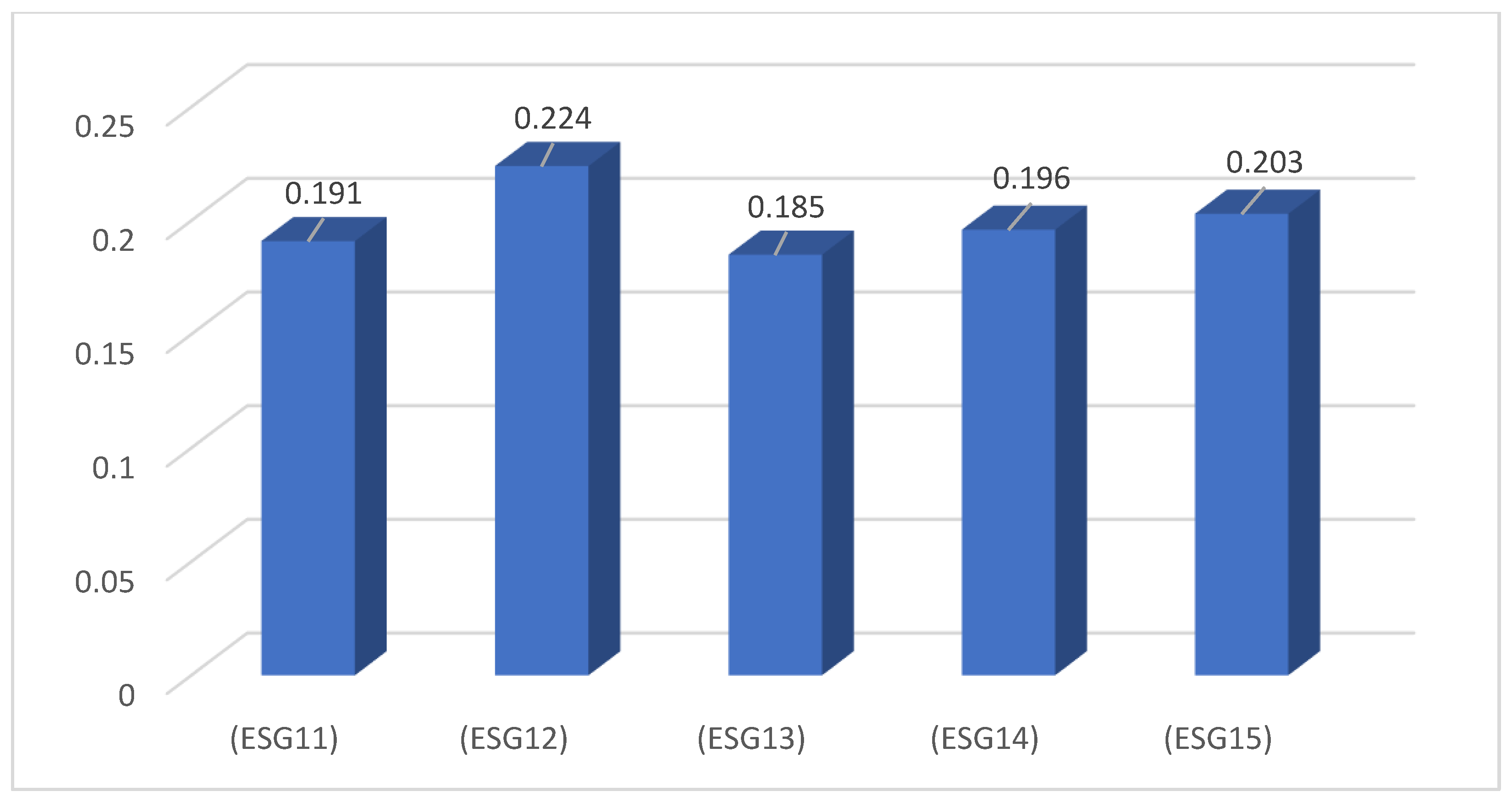

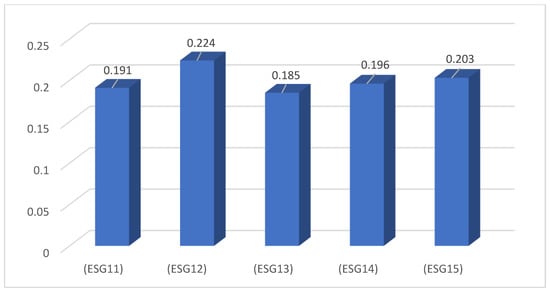

5.2. Results of the Environmental Subfactors

Figure 2 shows the final ranking of the environmental subfactors. According to the findings of the AHP analysis, climate change and carbon emissions (ESG12) were ranked as the most essential subfactor, followed by energy efficiency and renewable energy (ESG15) and biodiversity conservation and natural resource management (ESG14). According to this ranking, climate change and carbon emissions should be assigned the highest priority among environmental concerns when deciding on green financing investments in China. This should not be surprising because of the importance of addressing climate change globally and China’s position as the world’s largest carbon emitter. Investors should consider a business’s carbon footprint, renewable energy consumption sources, and endeavors to minimize CO2 emissions. The fact that renewable energy and energy efficiency sources attained the second-highest ranking demonstrates that investors should use them in their businesses. China has established lofty objectives for developing renewable energy sources, and investors should seek out companies progressing in this direction. The fact that biodiversity conservation and natural resource management were given the third-highest ranking indicates that although these factors may not be as crucial as climate change and energy efficiency, they are still highly essential to consider. Investors should seek out companies that prioritize conserving natural resources and adopting sustainable management practices. Included among natural resources are forests, water, and animals. The fact that water management and conservation (ESG11), and pollution prevention and control (ESG13) placed fourth and fifth in the ranking suggests that these factors are less significant than the others. However, investors should consider a company’s efforts to manage its water resources and prevent pollution.

Figure 2.

The ranking of environmental subfactors.

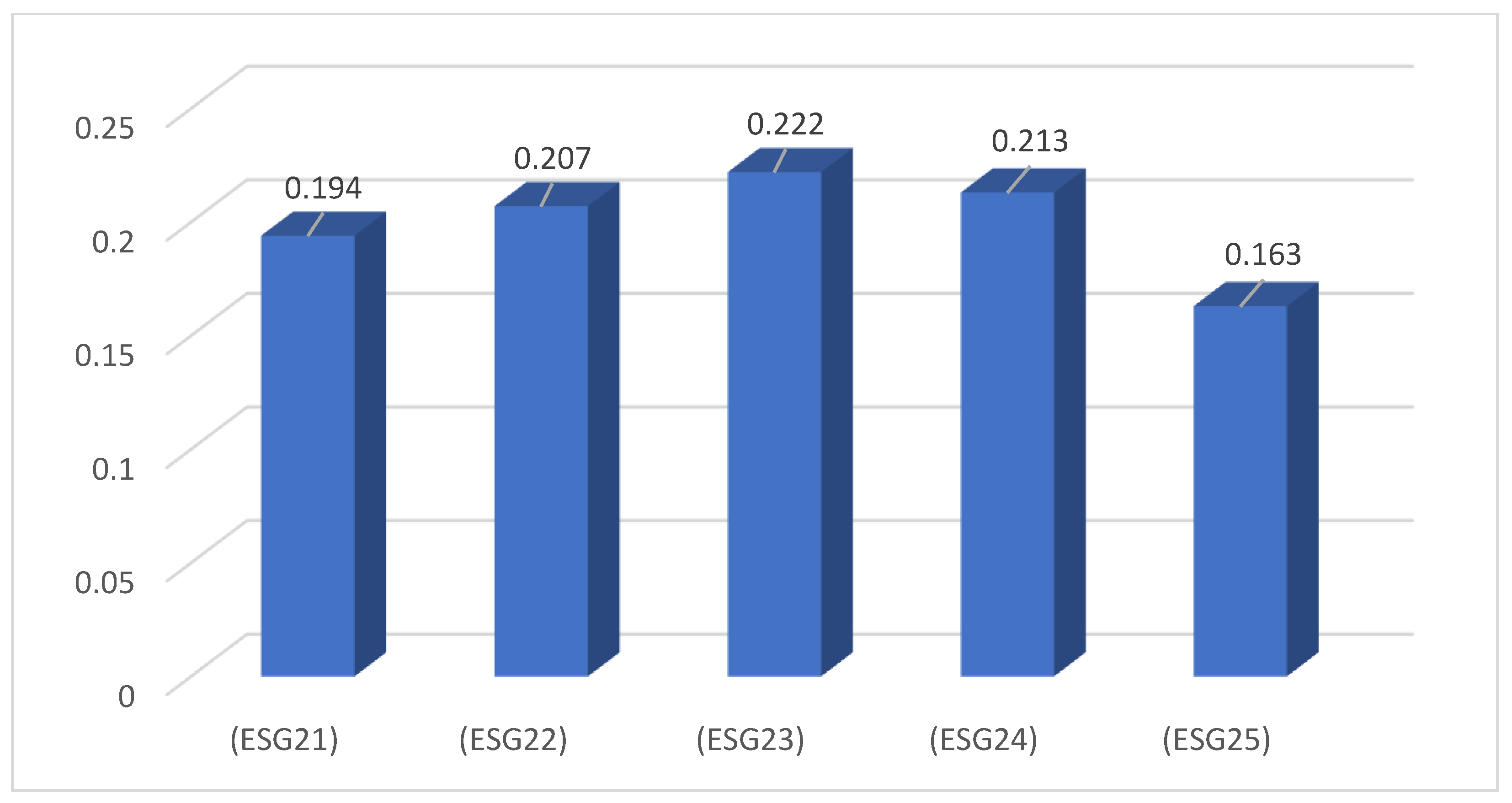

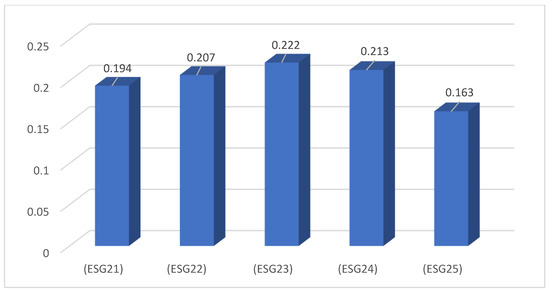

5.3. Results of the Social Subfactors

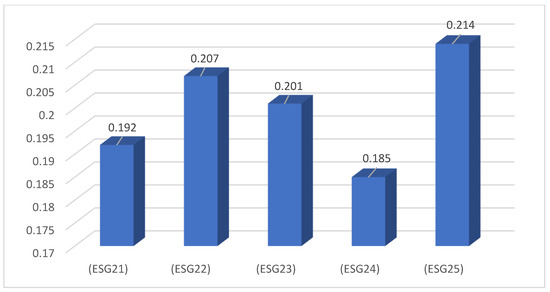

Figure 3 displays the ranking of the social subfactors. According to this ranking, diversity and inclusion (ESG23) has been prioritized as the highest out of the social factors when investing in environmentally friendly finance in China. When comparing a business enterprise’s overall social performance, buyers ought to consider various diversity-related factors comprising gender, race, ethnicity, and other components of diversity. This displays the growing awareness and emphasis on promoting diversity and inclusion in China’s commercial enterprise area, and it is something that has been receiving extra attention lately. The second-highest ranking for investors and stakeholders is community engagement and relations (ESG24). This emphasizes the significance of constructing a solid bond with local communities. Investors must do not forget a company’s efforts to engage with and establish significant relationships with local communities, comprising their impact on the local financial system, relationships with stakeholders, and contributions to network improvement. The health and safety (ESG22) factor achieved the third-highest importance, as investors must also remember businesses’ health and safety efforts in the workplace, such as worker safety and occupational health practices. Despite this, investors should continue to consider human rights, labor standards, and fair labor practices. The fact that access to basic services is ranked fifth, the lowest possible position, suggests that these factors are the least important of the social subfactors. Nevertheless, investors should consider a company’s efforts to provide access to basic services such as education, healthcare, and housing in their business analysis.

Figure 3.

The ranking of social subfactors.

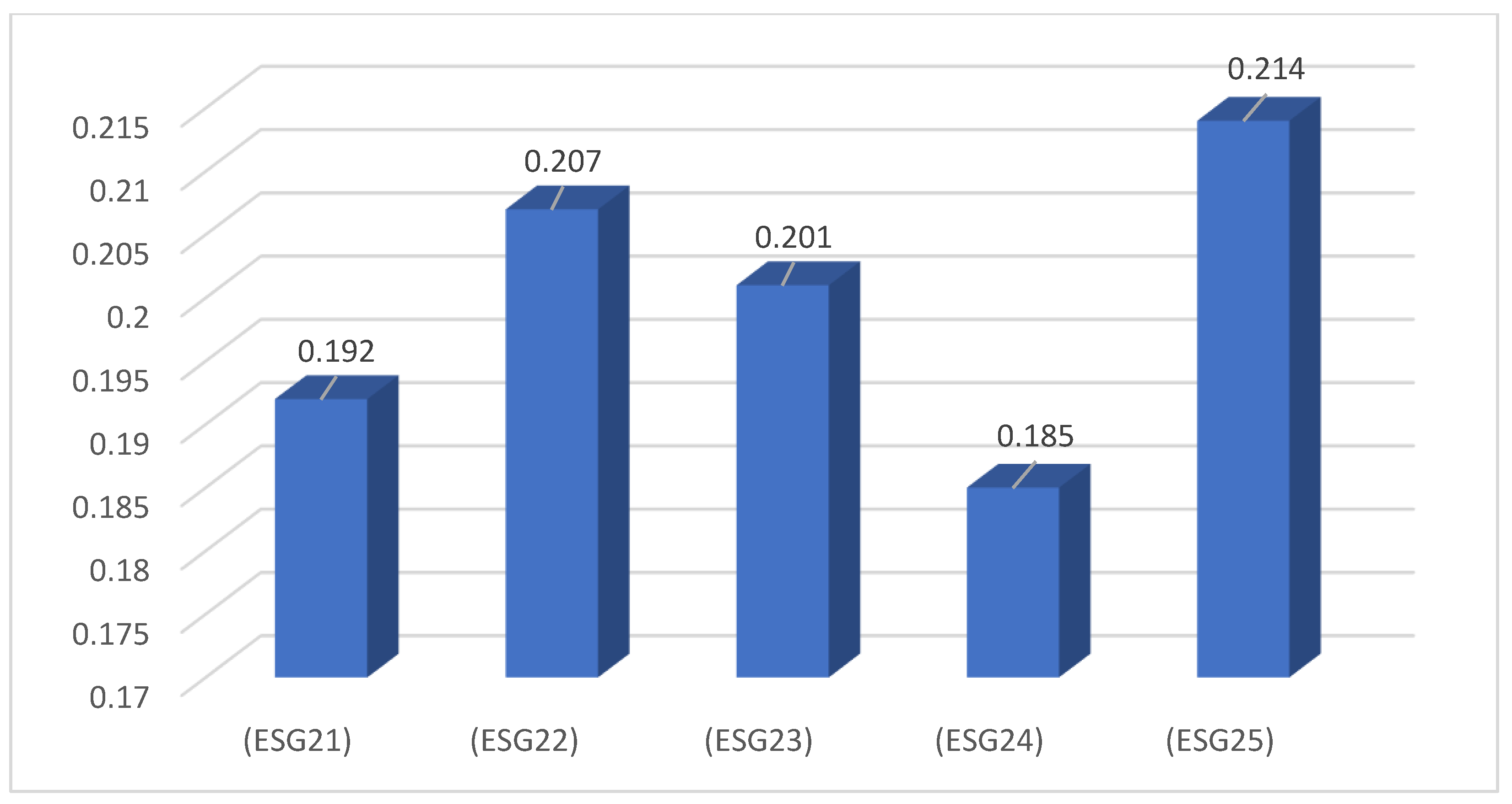

5.4. Results of the Governance Subfactors

According to the fuzzy AHP analysis findings, transparency and disclosure (ESG35) is the highest priority among the governance subfactors and should be the top priority for making investment decisions involving environmentally friendly finance in China. Investors should assess a company’s openness and disclosure, including financial reporting, corporate governance, and other KPIs. Transparency promotes investor trust and ecologically friendly company practices. According to the second-highest ranking of board structure and composition (ESG32), investors should also consider board independence, diversity, and expertise. Governance requires a well-structured, diversified board. Risk management and ethical behavior (ESG33) should be considered by investors. This ranking says investors should consider risk management and ethics. Executive compensation and accountability (ESG31) ranks fourth in China’s governance and investment decisions, but transparency and disclosure, board structure and composition, risk management, and ethical conduct are more important. Investors should consider executive compensation and accountability factors to ensure that a company’s management practices align with the sustainable development goals. The fact that anti-corruption policies and measures (ESG34) are ranked fifth, the lowest rank, suggests that these factors are the least important regarding governance subfactors. Nevertheless, investors should consider a company’s efforts to prevent and combat corruption by implementing policies and other measures. Figure 4 displays the results of sub-factors from governance perspective.

Figure 4.

The ranking of governance subfactors.

5.5. Results for Policies Using Fuzzy DEMATEL

As with the results of the factors and subfactors, this section provides the findings for the policies using the fuzzy DEMATEL method. Table 11 provides the final output values based on D and R values.

Table 11.

The final output values.

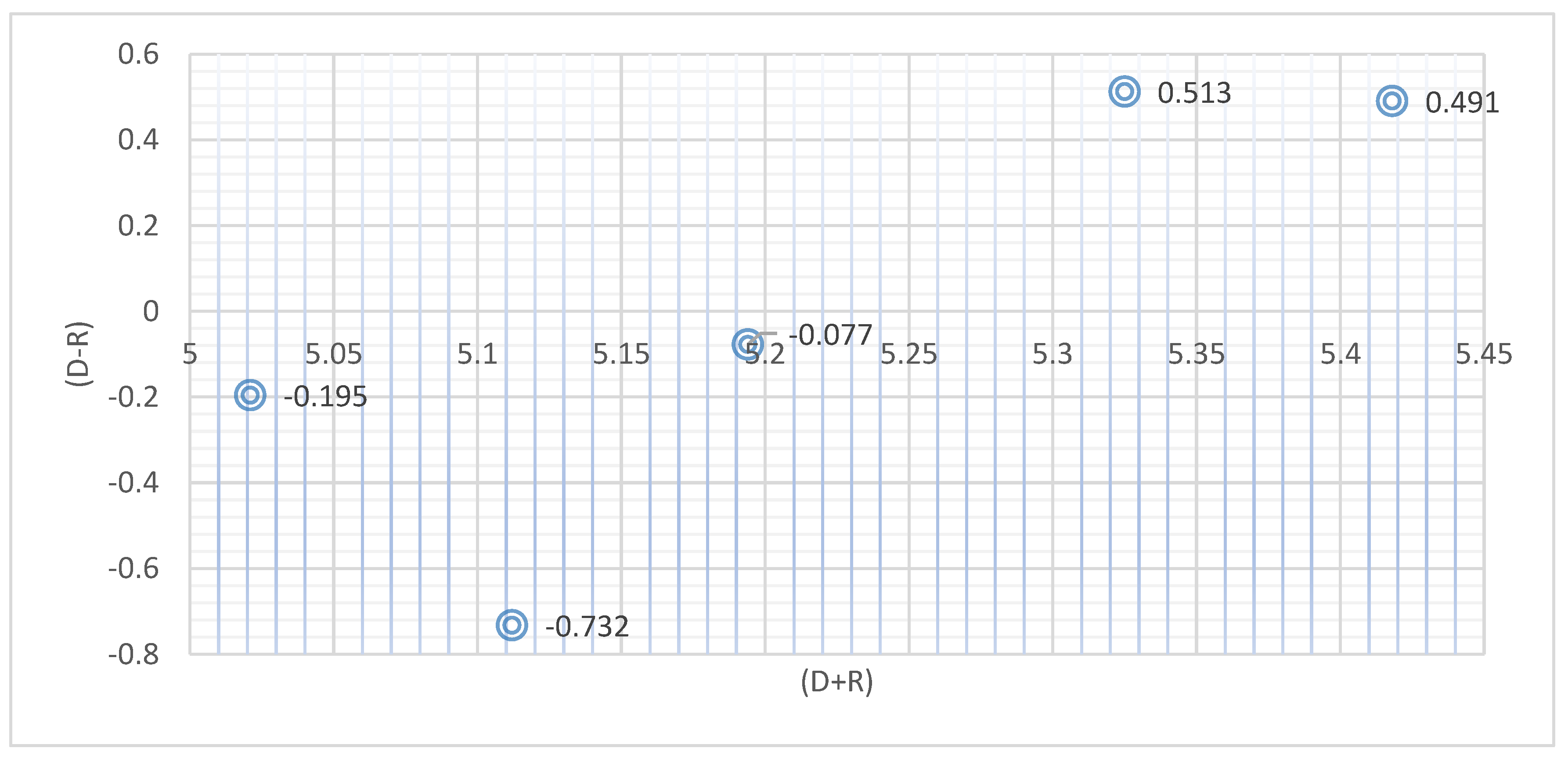

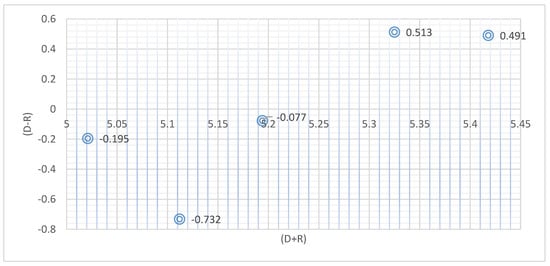

The significant relations model can be represented using a diagram, as shown in Figure 5. One way to draw this diagram is by plotting the values of (D + R) on the horizontal axis and the values of (D − R) on the vertical axis. Alternatively, a table can also be used to depict this model. The coordinate system helps determine the position of each factor and how it interacts with a point in the coordinates (D + R, D − R).

Figure 5.

The cause–effect diagram. Note: the diagram and table provide a framework for evaluating each factor based on specific aspects.

The horizontal vector (D + R) characterizes the significance of each factor within the system. Essentially, (D + R) signifies the combined influence of both factors on the overall system and the effects of other system factors on the specific factor. In terms of the degree of importance, supporting green finance innovation and development (P1) is ranked in first place, as encouraging social responsibility and community engagement (P4), developing and enforcing environmental regulations (P2), enhancing transparency and disclosure (P5), and collaborating with international partners (P3) are ranked in the following places. In this study, P1 and P4 are considered causal variables, while P2, P3, and P5 are regarded as effects. The Vertical vector (D − R) shows how much a factor affects the system. Positive D − R values mean the factor causes an effect, while negative values mean the factor is an effect of something else.

The fuzzy DEMATEL method is an efficient tool for identifying the causal relationships between the many system factors. Based on its effect on the entire system (D + R) and its influence on other factors (D − R), according to the analysis, P1 appears to be the most significant factor in the system.

5.6. Discussion

The fuzzy AHP and the fuzzy DEMATEL techniques provide remarkable insights into prioritizing numerous aspects of China’s sustainable development and the causal linkages between those elements. When considering measures for creating a greener financial system, the environment’s viability over the long term should take primacy, followed by considerations of governance and social factors. It has been determined that diversity and inclusion, transparency and disclosure, and climate change and carbon emissions are the most significant factors to consider. These findings align with China’s increasing awareness of and emphasis on environmental sustainability, corporate governance, and social responsibility. As the country with the highest per capita carbon emissions and the fastest-growing economy globally, China is confronted with tremendous environmental and social concerns. Therefore, investors and policy makers need to take considerations related to sustainability into consideration when deciding on investments and crafting regulations. Several studies have concluded that environmental considerations are crucial for sustainable development in China.

In comparison, social and governance aspects were found to be significantly less critical, coming in second and third place, respectively. For instance, ref. [67] discovered that environmental factors were the most important in influencing sustainable development in China, followed by social and economic factors in descending order of importance. Similarly, environmental factors were found to be the most important for the sustainable development of China’s tourism industry, according to a study carried out by [68]. The importance of some subfactors, revealed by the fuzzy AHP technique, is consistent with the findings of earlier studies. These subfactors include climate change and carbon emissions, energy efficiency, and biodiversity conservation. For instance, a study by [69] discovered that addressing climate change and reducing carbon emissions was vital to achieving sustainable development in China. A study by [70] discovered that achieving sustainable development in China necessitates boosting the energy efficiency and advancing renewable energy sources’ expansion. This finding can be attributed to the findings obtained through their research. Identifying the causal relationships, the fuzzy DEMATEL technique produced consistent outcomes, such as the positive effects of encouraging social responsibility and community engagement and supporting the innovation and development of green finance. For example, ref. [71] found that social responsibility and environmentally responsible finance were crucial to promoting sustainable development in the Chinese financial sector.

A study by [32] used fuzzy AHP analysis to evaluate the impact of ESG elements on adopting green financing in China. They further examined where environmental problems, power consumption, and air pollutants had the maximum effect on the spread of new finance. Governance elements, comprising authorities, regulations, and resources, have been deemed more relevant than social variables, including poverty reduction and task introduction. Our study additionally employs fuzzy AHP to assess ESG factors and rules for inexperienced finance funding decisions in China. We intend to verify the findings of [32] by presenting a better analysis of the country’s essential factors and guidelines for securing sustainable improvement and green finance.

Similarly, ref. [72] used the fuzzy DEMATEL method to observe the risk of green credit in China, considering the ESG elements. They observed that environmental factors, including air and water pollutants, drastically impacted the probability of inexperienced credit scores. However, the effect of social elements, working conditions, and civic engagement became minimal. This research work employed the fuzzy DEMATEL method to investigate the connections between ESG elements and rules for inexperienced finance funding decisions in China, which may additionally compliment the research of [72], which helped to provide a deeper dive into the dynamics at play between the variables forming China’s sustainable finance methods.

Research on the sustainable growth of China’s finance industry serves as an example of how our results regarding the essential relevance of environmental factors resonate across other industries within China. Like our study, other research has stressed how important environmental factors are to maintaining sustainable practices in the tourism industry. It is important to note that the main subfactors we identified, such as energy efficiency, biodiversity preservation, and climate change and carbon emissions, are consistent with findings from other studies. The fuzzy DEMATEL technique produced consistent results in terms of causal links, particularly with regard to the advantages of promoting civic involvement and social responsibility as well as fostering innovation and the growth of green finance. This finding is consistent with a larger body of research on sustainability that stressed the importance of social responsibility and environmentally conscious finance in fostering sustainable development in the Chinese financial industry. In demonstrating the importance of environmental variables in sustainable development and green financing in China, our research is consistent with earlier studies. In order to develop sustainability in the Chinese financial landscape, it further underlines the necessity for comprehensive initiatives that include social responsibility, community participation, and creative green finance practices. These combined results help us gain a deeper understanding of the complex system of variables and regulations required to promote sustainable development and green financing in China. Our research employs the fuzzy DEMATEL method to investigate the relationships between ESG factors and green finance investment policies in China. This approach may explain why our findings differ from previous studies. We can gain a better understanding of the most critical ESG factors and policies for promoting sustainable development and green finance in China as well as how they relate to the larger context of sustainable investment research if we interpret the potential implications of the findings of our study in relation to the findings of other studies.

5.7. Practical Implications

This study’s practical significance affects numerous stakeholders in China’s green finance and sustainable development ecosystem. Our rigorous techniques based on the fuzzy AHP and fuzzy DEMATEL methods emphasize ESG factors, providing institutional and individual investors with relevant guidance. Investors can choose green initiatives and ecologically responsible enterprises by acknowledging the relevance of environmental factors. This coincides with the worldwide sustainability trend and might generate financial gains and sustainable development.

5.7.1. Policy Formulation and Implementation

This study can help policy makers and regulators create green finance policies that boost long-term economic growth. The fuzzy DEMATEL causal relationships show the benefits of civic involvement, social responsibility, and innovation in green finance. The findings can help create financial sector policies that encourage social responsibility and innovation.

5.7.2. Financial Institution Strategy

This study can inform financial institutions’ strategies. Institutions can create and promote sustainable financial solutions for environmentally concerned investors as demand rises. Highlighting environmental elements in their products supports the global low-carbon economy. This addresses market needs and promotes financial sector sustainability.

5.7.3. Tailored Industry Solutions

A one-size-fits-all strategy is limited; therefore, stakeholders can use the findings to tailor solutions for specific industries. By understanding how ESG elements and policies vary across sectors like energy, manufacturing, and finance, stakeholders can build industry-specific strategies to improve sustainability activities.

5.7.4. Longitudinal Assessment

Policy makers, investors, and businesses can benefit from tracking ESG issues and policies over time. This approach shows how these aspects adapt to environmental, social, and economic changes. Such analyses enable proactive policy and strategy revisions to keep them relevant and effective.

5.7.5. Cross-Border Learning

Comparing China’s green finance regulations to global best practices can help policy makers identify areas for improvement. Cross-border learning can help implement successful policies and practices from other countries.

5.7.6. Behavioral Insights

Examining investors, businesses, and policy makers’ behavior might reveal motivations, attitudes, and decisions. Understanding these psychological aspects can help explain green finance policy acceptance and success. Behaviorally tailored communication and incentive techniques can boost sustainable finance adoption.

5.7.7. Support for SMEs

China’s economy relies on SMEs. Green finance regulations that assist SME sustainability can have a big impact. SMEs can help China develop sustainably with affordable funding and incentives. These practical implications help expedite green finance and sustainable development in China by incorporating them into stakeholder plans and actions.

6. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

The fuzzy AHP and fuzzy DEMATEL methodologies offer important insights into the ranking of numerous elements and their causal links to sustainable development in China. The findings imply that environmental sustainability should be prioritized after governance and social considerations when making green finance initiatives. Specific elements are identified as crucial within each area, including climate change and carbon emissions, openness and disclosure, and diversity and inclusion. The fuzzy DEMATEL method’s causal links show the interconnection and complexity of China’s sustainability factors. An essential step in advancing sustainable development and green finance in China is evaluating ESG elements and regulations for investment decisions utilizing fuzzy AHP and fuzzy DEMATEL methods. This research study identifies the most significant ESG variables and policies for green finance investment in China to provide a more thorough and detailed understanding of sustainable investment in the nation and examines the interrelationships among these factors and policies. To encourage sustainable development and green finance in China, our study has identified several significant ESG factors. These include governance factors like risk management, transparency, and disclosure, as well as environmental factors like carbon emissions reduction and energy efficiency. The study has also recommended particular regulations that might be put into place to support resilience and sustainability in these fields.

Policy Recommendations

Below are some policy recommendations based on this study:

Ecological Sustainability Priority: China should prioritize environmental sustainability in green financing. This can include targeted incentives, tax rebates, and subsidies for green projects and businesses. Use a carbon tax or cap-and-trade system to encourage industries to cut carbon emissions.

Improving Governance: Strengthen corporate governance and transparency regulations. This includes tougher reporting and noncompliance fines. Promote sustainable executive compensation. Integrate the ESG performance into executive pay.

Promoting Social Responsibility: Promote workplace diversity and inclusion with policies. Encourage companies to set diversity goals and report on them. Encourage firms to invest in community development and engage with local communities. Incentivize firms that care about the community.

Aiding Sustainable Innovation: Create government-backed or venture capital funds to develop and deploy green technology and ideas. Provide tax incentives and subsidies to sustainable solution research and development enterprises.

Promoting Cooperation: Work with worldwide partners, organizations, and financial institutions to share information and attract green finance investments. Encourage public–private cooperation for large sustainable infrastructure projects. Engage the private sector in sustainable development.

Monitoring and Reporting: Introduce standardized ESG reporting for listed firms. This will help investors evaluate companies’ ESG performance. To ensure sustainability, examine companies’ ESG practices regularly.

Support for SMEs: Customize green finance programs to assist SME sustainability. Allow SMEs to access financing, capacity-building, and technical help.

Sustainability Certification: Promote business sustainability certification programs to promote environmental and social responsibility. Evaluate green finance initiatives periodically. Adapt policies to changing situations and sustainability aims.

These policy suggestions can assist China in promoting sustainable development, green financing, and environmental protection, as the country wants to promote responsible ESG practices, innovation, and a sustainable, environmentally sensitive economy through policy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L.; Methodology, Y.L. and Y.A.S.; Validation, Y.Z. and Y.A.S.; Formal Analysis, Y.A.S.; Investigation, Y.L. and Y.Z.; Data Collection, Y.L. and Y.Z.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Y.L. and Y.A.S.; Writing—Review and Editing, Y.Z. and Y.A.S.; Supervision, Y.Z.; Funding Acquisition, Y.Z. All of the authors contributed significantly to the completion of this review, conceiving and designing the review, and writing and improving the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- United Nations. 1987: Brundtland Report; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Making Peace with Nature: A Scientific Blueprint to Tackle the Climate, Biodiversity and Pollution Emergencies; UNEP: Athens, Greece, 2021; ISBN 9789280738377. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, R.E.F. Schumacher, Small is Beautiful: A study of economics as if people mattered. Inst. Dev. Stud. Bull. 1975, 7, 34–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, D.; Yu, J.; Zhong, R. The Limits of Green Finance: A Survey of Literature in the Context of Green Bonds and Green Loans. Sustainability 2021, 13, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D.; Woo, W.T.; Yoshino, N.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. Importance of Green Finance for Achieving Sustainable Development Goals and Energy Security. In Handbook of Green Finance; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Desalegn, G.; Tangl, A. Enhancing Green Finance for Inclusive Green Growth: A Systematic Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Impacts of 1.5 °C Global Warming on Natural and Human Systems; IPCC: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Landberg, R.; Watanabe, C.; Lee, H. Climate Crisis Spurs UN Call for $2.4 Trillion Fossil Fuel Shift. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-10-08/scientists-call-for-2-4-trillion-shift-from-coal-to-renewables (accessed on 31 August 2023).

- World Bank. State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2021; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Khan, Z.A.; Alvarez-Alvarado, M.S.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Imran, M. A critical review of sustainable energy policies for the promotion of renewable energy sources. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Wang, B.; Xu, W.; Cui, Q.; Chen, H. Could China’s long-term low-carbon energy transformation achieve the double dividend effect for the economy and environment? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 20128–20144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Solangi, Y.A.; Wang, R. Evaluating and prioritizing the carbon credit financing risks and strategies for sustainable carbon markets in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 414, 137677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Solangi, Y.A.; Ali, S. Evaluating the Factors of Green Finance to Achieve Carbon Peak and Carbon Neutrality Targets in China: A Delphi and Fuzzy AHP Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh-Hesary, F.; Yoshino, N. The way to induce private participation in green finance and investment. Financ. Res. Lett. 2019, 31, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Nie, L.; Sun, H.; Sun, W.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. Digital finance, green technological innovation and energy-environmental performance: Evidence from China’s regional economies. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 327, 129458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Su, X.; Yao, S. Nexus between green finance, fintech, and high-quality economic development: Empirical evidence from China. Resour. Policy 2021, 74, 102445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Du, F. Nexus between green financial development, green technological innovation and environmental regulation in China. Renew. Energy 2023, 204, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, S.A.; Šaparauskas, J.; Turskis, Z. A multi-criteria decision-making model to choose the best option for sustainable construction management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Huang, W.; Zhang, Y. Identifying critical success factors in emergency management using a fuzzy DEMATEL method. Saf. Sci. 2011, 49, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.J.; Chang, H.Y.; Hung, B. Identifying Key Financial, Environmental, Social, Governance (ESG), Bond, and COVID-19 Factors Affecting Global Shipping Companies—A Hybrid Multiple-Criteria Decision-Making Method. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escrig-Olmedo, E.; Rivera-Lirio, J.M.; Muñoz-Torres, M.J.; Fernández-Izquierdo, M.Á. Integrating multiple ESG investors’ preferences into sustainable investment: A fuzzy multicriteria methodological approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 1334–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundström, E.; Svensson, C. Including ESG Concerns in the Portfolio Selection Process. Bachelor’s Thesis, School of Engineering Sciences, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden, 2014; 83p. [Google Scholar]

- Kates, R.W.; Parris, T.M.; Leiserowitz, A.A. What is sustainable development? Goals, indicators, values, and practice. Environment 2005, 47, 8–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mensah, J. Sustainable development: Meaning, history, principles, pillars, and implications for human action: Literature review. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 1653531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.; Nadeem, F.; Sloan, M.; Restle-Steinert, J.; Deitch, M.J.; Ali Naqvi, S.; Kumar, A.; Sassanelli, C. Fostering Green Finance for Sustainable Development: A Focus on Textile and Leather Small Medium Enterprises in Pakistan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P.K. Green finance research around the world: A review of literature. Int. J. Green Econ. 2022, 16, 56–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiakui, C.; Abbas, J.; Najam, H.; Liu, J.; Abbas, J. Green technological innovation, green finance, and financial development and their role in green total factor productivity: Empirical insights from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 382, 135131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali Swain, R.; Yang-Wallentin, F. Achieving sustainable development goals: Predicaments and strategies. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2020, 27, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampedro, R. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). Carreteras 2021, 4, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.W. Green finance and sustainable development goals: The case of China. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, Y. The Effect of Green Finance on Energy Sustainable Development: A Case Study in China. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2021, 57, 3435–3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Shaikh, G.M. Evaluating Environmental, Social, and Governance Criteria and Green Finance Investment Strategies Using Fuzzy AHP and Fuzzy WASPAS. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haessler, P. Strategic decisions between short-term profit and sustainability. Adm. Sci. 2020, 10, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Du, P. How China “Going green” impacts corporate performance? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Shen, Z.; Song, M.; Vardanyan, M. The role of green financing in facilitating renewable energy transition in China: Perspectives from energy governance, environmental regulation, and market reforms. Energy Econ. 2023, 120, 106595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Y.; Gao, J.; Ye, T. How does green credit affect the financial performance of commercial banks?—Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 344, 131069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Tan, Q.; Solangi, Y.A.; Ali, S. Sustainable and Special Economic Zone Selection under Fuzzy Environment: A Case of Pakistan. Symmetry 2020, 12, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.H.; Lye, C.T.; Chan, K.H.; Lim, Y.Z.; Lim, Y.S. Sustainability in Asia: The Roles of Financial Development in Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Performance. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 150, 17–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Tan, Q.; Shaikh, G.M.; Waqas, H.; Kanasro, N.A.; Ali, S.; Solangi, Y.A. Assessing and Prioritizing the Climate Change Policy Objectives for Sustainable Development in Pakistan. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Ahmed, S.; Shumon, M.R.H.; Falatoonitoosi, E.; Quader, M.A. A comparative decision-making model for sustainable end-of-life vehicle management alternative selection using AHP and extent analysis method on fuzzy AHP. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2016, 23, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocampo, L.A.; Himang, C.M.; Kumar, A.; Brezocnik, M. A novel multiple criteria decision-making approach based on fuzzy DEMATEL, fuzzy ANP and fuzzy AHP for mapping collection and distribution centers in reverse logistics. Adv. Prod. Eng. Manag. 2019, 14, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Mu, B.; Ahmad, N. Fostering land use sustainability through construction land reduction in China: An analysis of key success factors using fuzzy-AHP and DEMATEL. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 18755–18777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, H.-M.; Sun, W.-J.; Shen, S.-L.; Zhou, A.-N. Risk Assessment Using a New Consulting Process in Fuzzy AHP. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04019112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Wu, Z. Social sustainable supply chain performance assessment using hybrid fuzzy-AHP–DEMATEL–VIKOR: A case study in manufacturing enterprises. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 25, 12273–12301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, R.; Li, S.; Qu, L.; Sun, L.; Gong, C. Critical factors to green mining construction in China: A two-step fuzzy DEMATEL analysis of state-owned coal mining enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 273, 122852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lian, G.; Xu, A. How do ESG affect the spillover of green innovation among peer firms? Mechanism discussion and performance study. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 158, 113648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Q.; Wang, H.; Bai, C. Local green finance policies and corporate ESG performance. Int. Rev. Financ. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadaba, D.M.K.; Aithal, P.S.; KRS, S. Impact of Sustainable Finance on MSMEs and other Companies to Promote Green Growth and Sustainable Development. Int. J. Appl. Eng. Manag. Lett. 2022, 6, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Orazio, P. The Politics of Climate Finance and Policy Initiatives to Promote Sustainable Finance and Address ESG Issues. In Sustainable Finance and ESG: Risk, Management, Regulations, and Implications for Financial Institutions; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 145–171. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Hu, L.; He, X.; Liu, Z.; Chen, D.; Wang, W. Green Financial Reform and Corporate ESG Performance in China: Empirical Evidence from the Green Financial Reform and Innovation Pilot Zone. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilan, G.; Cordella, M.; Morone, P. Evaluating and managing the sustainability of investments in green and sustainable chemistry: An overview of sustainable finance approaches and tools. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 36, 100635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Du, Q.; Razzaq, A.; Shang, Y. How volatility in green financing, clean energy, and green economic practices derive sustainable performance through ESG indicators? A sectoral study of G7 countries. Resour. Policy 2022, 75, 102526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrou, R.; Dessertine, P.; Migliorelli, M. An Overview of Green Finance. In The Rise of Green Finance in Europe: Opportunities and Challenges for Issuers, Investors and Marketplaces; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar]

- Poyser, A.; Daugaard, D. Indigenous sustainable finance as a research field: A systematic literature review on indigenising ESG, sustainability and indigenous community practices. Account. Financ. 2023, 63, 47–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhou, C.; Gan, Z. Green Finance Policy and ESG Performance: Evidence from Chinese Manufacturing Firms. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, M. The ethics of ESG Sustainable finance and the emergence of the market as an ethical subject. Focaal 2022, 2022, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driessen, M. Sustainable Finance: An Overview of ESG in the Financial Markets. In Sustainable Finance in Europe: Corporate Governance, Financial Stability and Financial Markets; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 329–350. [Google Scholar]

- Macchiavello, E.; Siri, M. Sustainable Finance and Fintech: Can Technology Contribute to Achieving Environmental Goals? A Preliminary Assessment of “Green Fintech” and “Sustainable Digital Finance”. Eur. Co. Financ. Law Rev. 2022, 19, 128–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, N.; Lei, X.; Long, R. Green finance innovation and regional green development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemfert, C.; Schmalz, S. Sustainable finance: Political challenges of development and implementation of framework conditions. Green Financ. 2019, 1, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, M.G.; Martin, F.; Walter, A. The power of ESG transparency: The effect of the new SFDR sustainability labels on mutual funds and individual investors. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 47, 102708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, L.; Solangi, Y.A. Strategic renewable energy resources selection for Pakistan: Based on SWOT-Fuzzy AHP approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 52, 101861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kul, C.; Zhang, L.; Solangi, Y.A. Assessing the renewable energy investment risk factors for sustainable development in Turkey. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276, 124164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogus, O.; Boucher, T.O. Strong transitivity, rationality and weak monotonicity in fuzzy pairwise comparisons. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1998, 94, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanka, R.; Ravindran, K.; Sankaranarayanan, B.; Ali, S.M. A fuzzy DEMATEL decision modeling framework for identifying key human resources challenges in start-up companies: Implications for sustainable development. Decis. Anal. J. 2023, 6, 100192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addae, B.A.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, P.; Wang, F. Analyzing barriers of Smart Energy City in Accra with two-step fuzzy DEMATEL. Cities 2019, 89, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.H.; Zhao, Y.X.; Jiang, C.F.; Li, Z.Z. Does green finance inspire sustainable development? Evidence from a global perspective. Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 75, 412–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Luo, Y.; Aziz, N.; Jamal, A.; Zhang, Q. Environmental impact of the tourism industry in China: Analyses based on multiple environmental factors using novel Quantile Autoregressive Distributed Lag model. Econ. Res. Istraz. 2022, 35, 3663–3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, J.; Tan, T.; Yuan, W.; Yang, X.; Zhu, Y. Decomposition analysis of tourism CO2 emissions for sustainable development: A case study of China. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Sinha, A.; Hu, K.; Shah, M.I. Impact of technological innovation on energy efficiency in industry 4.0 era: Moderation of shadow economy in sustainable development. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 164, 120521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, R.; Xiang, E. Corporate social responsibility, green financial system guidelines, and cost of debt financing: Evidence from pollution-intensive industries in China. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, Z.; Ghardallou, W.; Xin, Y.; Cao, J. Nexus of institutional quality and technological innovation on renewable energy development: Moderating role of green finance. Renew. Energy 2023, 214, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).