Abstract

With the increasing refugee crisis worldwide, a great promise lies in the 2030 agenda to help ‘leave no one behind.’ This article aims to take stock of implementing the 2030 Agenda in the refugee camps of the Arab Middle East based on empirical data from Syrian refugees and Iraqi IDPs collected using a questionnaire distributed in Iraq, Jordan, and Lebanon. SDGs’ indices were calculated using arithmetic mean and principal component analysis methods. Our study finds that the progress toward achieving the SDGs is diverse in three locations, mainly due to the policy applied in the host country. The respondents in Iraq ranked the best at social and economic sustainability, Jordan ranked the best at environmental sustainability, and Lebanon was the furthest left behind in the three dimensions. SDG7 has a high performance, but accelerating the progress toward achieving the remaining SDGs is essential. Without the substantial efforts of all stakeholders, the 2030 agenda will not be accomplished.

1. Introduction

The Syrian refugee (SR) crisis is considered the worst humanitarian disaster ever since the Rwandan genocide almost three decades ago []. From 2011 to 2020, 6.7 million people have been internally displaced and 6.6 million have fled over the world []. The majority of the last have fled into the immediate neighbors of Syria. In total, 5,570,118 refugees were registered, of which 865,531 SRs were in Lebanon, 661,997 SRs were in Jordan, 242,163 SRs were in Iraq, and 3,638,193 SRs were in Turkey. A total of 5% of SRs reside in camps [].

Refugees have had international protection under the United Nations (UN) Convention since 28 July 1951 [], and the Protocol of 31 January 1967 [], which constitute one of the main pillars of their international protection. The latter legal instruments are the cornerstone in international refugee law; thus, their provisions bound states []. However, states that did not join them are not bound by their provisions, unless they are bound by similar obligations under other regional treaties. Moreover, almost 7 decades after the adoption of the convention, not all states are parties to it or its 1967 Protocol, as is the case of Syria’s neighbors, namely, Lebanon, Jordan, and Iraq [].

The 2030 agenda, agreed upon in 2015, has 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) associated with a commitment to ‘leaving no one behind’ with a concentration on vulnerable people, such as refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs). Less than one decade remains before the agenda’s deadline, yet only 35% of low- and middle-income countries are on track to meet the SDG targets related to basic needs. In total, 18% of fragile countries are on track; however, the remaining 82% are either off-track or have a shortage of data to assess their progress []. Moreover, forced displaced people were de facto ignored and left behind because of the limited availability of data on refugees’ progress toward achieving the 2030 agenda []. To improve economic, environmental, and social sustainability and achieve the 2030 Agenda, information on SDGs in refugee settlements is crucial. Yet, refugees are mostly excluded, and the majority of refugee-hosting countries ignore refugees on their national SDG plan or progress report, and sub-national data on refugees, including health care, education, water and sanitation, energy, housing, transportation, are seldom provided [,].

In March 2020, refugees were explicitly mentioned with the commitment of ‘leaving no one behind’ under target 10.7, which stresses the enabling of ‘orderly, safe, regular and responsible migration and mobility of people, including through the implementation of planned and well-managed migration policies’. It is represented by the indicator 10.7.4, which corresponds to the number of refugees by country of origin as a proportion of the national population of that country of origin []. Later, UNHCR linked the SDGs with the Global Compact on Refugees (GCR) [,], which was launched in 2018 following the New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants [] and the Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework (CRRF). Yet, the linkage is not clear enough to generate data regarding SDGs. Furthermore, in December 2020, UNHCR and Joint IDP Profiling Service (JIPS) provided a review to published disaggregated SDG indicators according to the 12 priority SDG indicators recommended to be disaggregated by forced displacement, divided into three priority policy areas identified by the Expert Group on Refugee and IDP Statistics (EGRIS) in 2019 [].

The objective of this study is to explore the status of the refugee camps (RCs) in Syria’s bordering countries and highlight how much effort is needed to achieve the 2030 agenda and its commitment of leaving no one behind. Such research is important to promote public deliberation and inform policymaking.

Although many types of RCs exist, this article explores the consequences of the policy applied for displaced Syrians in the three countries, including planned camps set by national governments or international agencies, such as the case of Jordan, or self-settled camps developed by affected populations, such as in Lebanon. This study is the first to measure the RCs’ progress toward SDGs in the selected three hosting countries. It presents the strengths and weaknesses of the strategy applied in alignment with SDGs to better understand the situation in RCs. The article consists of seven sections. After this brief introduction, Section 2 presents the literature review. Section 3 describes the methodology adopted. Section 4 presents the situation and policy imposed in the three selected countries. Section 5 displays the results obtained and a comparative analysis of the situation in the three countries through twelve SDGs. Section 6 debates the results and policy implications. Finally, Section 7 draws the concluding remarks.

2. Literature Review

The circumstances of people living in RCs vary between countries and camps in the same country. Twelve out of the fifteen highest refugee-hosting countries are fragile, which doubled the refugees’ marginalization, combined with an inadequate accountability capacity to meet refugees’ needs []. Refugees usually experience a lack of access to basic needs, such as shelter, food, water, healthcare, and education. Meanwhile, hosting countries struggle to afford the unforeseen flow of refugees, rendering a massive strain on them and limiting their potential for sustainable development [,]. RCs are considered temporary; however, they turn to long-term and even to permanent settlements, where refugees end up spending decades in what are supposed to be temporary settlements []. As a result, it is important to think of RC as a long-term settlement and consider its sustainability when no other alternative is available.

There have been few studies discussing the status of different SDGs in RCs [,,,,,,], while more studies discussed one goal in refugee settlements, i.e., SDG3 [,]; SDG4 [,]; SDG6 []; SDG10 []; SDG11 []; and SDG7 was the most studied in RCs [,,,,,].

Samman et al. [] showed that meeting the 2030 agenda requires a redoubling of efforts targeted at fragile states and the people living in crisis within their boundaries. Failing to ensure that no one is left behind will signify that the gap between those people and the rest of the world will expand and that the SDGs remain unachieved. Samman et al. [] suggested that further research is needed to identify where progress toward SDGs has been achieved for the left-behind groups including, but not limited to, refugees mainly in the least-developed countries. A systematic review [] showed that although the research on SDGs in RCs is growing since 2015, there is a need for more research on SDGs in RCs. Hence, this research comes to decrease the gap in the literature and to provide evidence of the progress of SDGs in RCs in three developing countries.

3. Methodology

3.1. Approach

This paper reflects on the progress toward meeting the 2030 agenda in RCs in the selected countries, where data were collected to develop an RC-related SDGs index. In view of this, the paper builds on and adapts the existing framework to establish a link between the SDGs and RCs. Targets and indicators related to RCs selected for this study were taken from the SDG indicator framework developed by the Inter-agency and Expert Group (IAEG-SDGs) [].

Data used were obtained from a questionnaire concentrating on quantitative and qualitative data of refugees across dispersed informal settlements in Lebanon, Zaatari RC in Jordan, and different IDPs and RCs in Iraq. The questions were based on, but not limited to, priority issues and targets related to SDGs and displaced people living in camps. Questions were first tested and further adjusted to be clear to the respondents. The questions were designed to include a variety of approaches to try and capture a better understanding of the current situation in RCs. The question formats included the following:

- Basic ‘yes’ or ‘no’ questions;

- Predetermined multiple choice questions;

- Value statements with choices from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’;

- Optional text, allowing further responses instead of predetermined answers.

The questionnaire was conducted using Google form in Lebanon and Iraq while Kobo was used in Jordan. Both Arabic and English languages were available. In both Iraq and Jordan, the questionnaire was sent through social media (both WhatsApp and Facebook), initial contacts were attained through personal contacts. Then, snowball sampling was followed, where we asked each participant to indicate one other potential participant at least. Participants who did not have direct access to internet were kindly invited to answer the questionnaire at the shelter of the person who indicated them. In Lebanon, two associations working with SRs helped run the questionnaire in person.

Given the difficulty of collecting responses in RCs during the current pandemic and travel constraints, we used the recommended sample size at 97, for 95% confident level and 10% of error. Of 105 submitted answers and 4 duplicated, a final 101 individual questionnaires were achieved.

The countries of origin of the respondents were Syria (78%) and Iraq (22%). The questionnaire was produced between October 2020 and March 2021. The distribution of the respondents was 46% in Iraq, 32% in Jordan, and 23% in Lebanon.

The questions were based on targets and indicators related to SDGs, which displaced people living in camps could answer. Questions were first tested and further adjusted to be clear to the respondents.

3.2. Data Analysis

The analysis of the data was carried out using the ‘IBM SPSS Statistics 25’ software. The reliability of the data was acceptable. Then, a Crosstabs analysis was used to disaggregate the answers on the country of residence. A normality test was carried out using Shapiro–Wilk test to determine whether the answers were significantly or insignificantly different. The result of the normality test was significant, indicating that the samples do not follow the normal distribution. Thus, nonparametric tests were employed to determine whether the answers amongst the groups were significant or not.

3.3. Ethical Standards and Data Management

Information about the nature of the study and the voluntary basis of participation were introduced and informed written consent was obtained prior to starting the questionnaire. It was made clear that no assistance would be associated with the participation. There were no respondents under 18 years old. All questions were securely required to be answered, participants had the option to skip any question at any part of the questionnaire. All data were treated in an anonymous way. No names of participants or any personal details (emails, IP address, etc.) were collected.

3.4. Aggregation of SDGs Index

The composite index is a mathematical aggregation of a set of the selected indicators to present a country’s position and measure the performance of RCs toward the 2030 Agenda between the worst and the best (0–100). The selection of indicators used in the current study was based on their applicability in RCs and on the ability of the population to answer relevant questions correctly. The final list required to construct the index included only the RC-related indicators that people could answer in our questionnaire (Table A1). Yet, the identified indicators provide an important starting point to build insight into RCs progress towards the achievement of SDGs, which can be used as a baseline and be improved with future studies.

The aggregation was carried out in two ways, the arithmetic mean method of aggregation and the principle component analysis (PCA), because it is important to test the sensitivity of the country ranking to guarantee that policy messages are not based on highly sensitive calculations []. However, the results will be first presented according to the arithmetic mean method (Table A2) while a comparison will be highlighted when a different ranking appears according to the PCA methods using Kruskal–Wallis test (Table A3).

The arithmetic mean aggregation method has been widely used in the aggregation of indices including SDG indicator and dashboards for countries due its easy application and communication []. Data were normalized using min–max normalization method for each indicator by converting it, linearly, to a scale of 0–100 to ensure its comparability []. The data were ordered from worst (0) to best (100). The arithmetic mean of related indicators was computed to score each target and then each SDG. The same indicators were used for the three countries. Equal weighting was used at indicator and goal level because there was no agreement across different epistemic societies on appointing higher weights to some SDGs over others []. The indices for the selected SDGs and the three dimensions of sustainability, social (SDGs 4, 5, 10, 11, 16, and 17), environmental (SDGs 6 and 7), and economic (SDGs 1, 2, 3, and 8), were computed. The resultant scores of the 12 selected SDGs were incorporated into an overall SDGs index.

Second, we applied PCA to compare the changes in ranking and performance of countries for each SDG using different methods than those mentioned earlier. PCA is a multivariate data analysis method that can aggregate a large set of indicators to construct the indices without losing related information. Each SDG was modeled with PCA independently using the set of related indicators. Indicators under each target were modeled first, and then combined with indicators under other targets to form each SDG index. The resultant scores were incorporated into three indices representing the three dimensions of sustainability as in the previous method. Variables were normalized into binary variables that take 1 if a certain condition was satisfied, and 0 otherwise. Based on that, PCA was run for each of the 12 selected SDGs. Then, we aggregated and used the resulting components to obtain the mean rank for each country using Kruskal–Wallis test, moreover, to see if there is any statistical evidence on differences between the three countries. Kruskal–Wallis test was chosen because the comparison requires a nonparametric test, since our variables were not normally distributed. The results indicated each SDG ranking of the three countries. After, we ran another PCA to aggregate the SDGs into the three dimensions of sustainability, as previously.

4. Three Bordering Host Countries: Different Refugee Camps

This section describes mainly the policy imposed in the three countries and the background of RCs, including the location, respondent’s distribution, population, and growth history.

4.1. Iraq

Iraq receives refugees under the 1971 Political Refugee, Act no.51, which gives political and military refugees benefits, such as the right to work and equal access to health and education services as Iraqis, and Law No. 21 of 2009 from the Ministry of Migration and Displacement. Yet, the protection delivered under this legislation lacks consistency related to rights and entitlements. In 2016, UNHCR signed the Memorandum of Understanding with Iraq to improve the protection of refugees []. Iraqis have experienced displacement before, and Syria was one of the countries that welcomed them. Moreover, the common Kurdish ethnicity, as most SRs in Iraq were Kurdish, and transborder relations played an important role in the way the government and locals, mainly in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI), are receptive towards the SRs, especially at the beginning of 2012 and 2013 when the KRI did not have an economic crisis. The KRI followed the ‘open-door policy’ for both Iraqi IDP and SRs and facilitated the registration process for them, guaranteeing the freedom of movement, residency, and access to basic services and economic opportunities [,].

Most respondents (n = 44) live in Duhok governorate (45.7% live in Domiz 1, followed by 21.7% in Chammishko Camp, 10.9% in Domiz 2, 6.5% in Khanki, 4.3% Kabartu, and 2.2% are respondents from Akre settlement) and 1 respondent in Erbil in Qushtapa camp, and 1 did not mention it. The majority of SRs are in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, where 40% of them are based in camps []. Only in Iraq does the survey include both SRs and Iraqi IDPs. In 2020, around 57,0000 refugees and IDPs lived in Duhok governorate. A total of 31% of IDPs (152,000) lived in 16 camps, including Jameshko, Khanki, and Kabartu; 60% of refugees in Duhok (50,000) live in 5 camps, including Domiz 1 and 2 and Akre. The largest population lives in Domiz 1 (28,126), followed by Chammishko (24,340), and Khaki (14,894) [].

4.2. Jordan

Before the Syria crisis, Jordan permitted Syrians to travel freely across the border, with constraints on the right to work. Syrians were welcomed and encouraged to stay in camps instead of urban areas to receive more international visibility, learning from Jordan’s previous experience with Iraqi refugees. Gradually the government started to become worried about the country’s security. Therefore, in 2013, more restrictions were applied on the movement to and from the camps, and on border crossings informally. Later, in 2016, the Jordan Compact was signed as an agreement to decrease the barriers to refugees’ access to work. At the sub-national level, specifically in Mafraq, a historically rooted relation and longstanding kinship ties exist between Syrians and locals. The municipality takes advantage of the camp to seek more economic support from the central government [].

All respondents (n = 32) lived in Al Zaatari RC, which is considered one of the world’s largest camps []. It was established in 2012 in the Mafraq governorate in North Jordan and has 12 districts []. It hosts currently 80,000 SR [].

4.3. Lebanon

Lebanon received Syrians according to its 1991 and 1993 bilateral agreements permitting mutual freedom of movement, residence, and property ownership. Although there is a historical longstanding relationship between the two countries, old tension exists due to the Syrian military existence in Lebanon and the exploitation and corruption of military and political officials. Lebanon has many political parties, based on religious sects, and had no government between 2013 and 2016; therefore, it took the ‘disassociation policy’ regarding the conflict and looked at SRs from humanitarian instead of security terms. Due to the previous experience with Palestinian refugees who never went back home, Lebanon refused to establish official camps and refused to call Syrians ‘refugees’, instead calling them displaced. When the Syria crisis seemed to be protracted, there was a strong fear that the presence of SRs would be permanent. In 2013, the disassociation ended, and Lebanon became involved in the Syrian conflict, which led to a deterioration in security. In 2014, the ‘October policy’ was acknowledged, where new restrictions on Syrian movement and residency were imposed to decline refugee numbers crossing the border and encourage return, to execute security procedures at the municipal level, and to prevent Syrians from working without a permit to ease the burden and pursue international support. This led to the Lebanon Crisis Response in 2014, followed by the Lebanon Compact in 2016, with an emphasis on promoting job and educational opportunities for refugees and nationals. However, the Lebanese Armed Forces boosted their incursions on the informal SR Settlements. At the municipal level, the practices have varied. The policy of ‘no policy’ that the government adopted gave more freedom for each municipality to impose its own policy. The variation of policies was based on identity politics, particularly the role of confessionalism. They followed the political economy, where some municipalities sought international support to improve the services that SRs in both urban areas and refugee settlements utilize [].

Most SRs live in urban areas, while the remaining portion remains in spontaneously set-up tented settlements, distributed throughout the country. Those self-settlements are located near the border with Syria, mainly Beqaa and northern Lebanon []. At the end of 2016, more than 2650 informal settlements existed in Beqaa with 29,000 tents []. In August 2020, Bekaa had the largest number of registered refugees in Lebanon with 339,473 individuals (38.6%) [].

Respondents (n = 25) were mainly from Middle Beqaa (Bar Elias 43.5% and Taalabaya 8.7%), West Beqaa (Aljarahieh 8.7%), and Arsal 4.3%. Other respondents have not determined their location.

5. Results

The questionnaire allows us to understand how the RCs in the three selected hosting countries perform regarding the refugee-related SDGs. For this reason, we have considered related targets and indicators (Table A1), taking into account the validity of the collected data. All data related to respondent and SDGs are presented in the appendix (Table A4).

5.1. Goal 1: ‘End Poverty in All Its Forms Everywhere’ []

By 2030, the majority of people who are extremely poor will live in vulnerable and conflict-affected countries, including refugees [], who generally flee to neighboring countries which are mostly low- and middle-income and already host the majority of refugees worldwide [], like the three countries in this study.

A total of 55% and 62% of respondents in Jordan and Lebanon, respectively, live under the international poverty line (1.1.1) with less than USD 1.9 per capita per day (PCPD) compared to 38% of Iraq respondents. Almost half of Iraq respondents live below the national poverty line (1.2.1) with less than USD 3.20 PCPD compared to a quarter of the population []. A total of 65% of Jordan respondents live below USD 3.20 PCPD compared to 3.3% of their Jordanian peers []. Three quarters of Lebanon respondents live below USD 3.84 PCPD, the national poverty line for Lebanon compared to half of their Lebanese peers at the same time of the survey []. After the explosion of the port and COVID-19, almost the entire SRs and three quarters of the Lebanese population were pushed into extreme poverty [].

The proportion of the population living in households with access to all basic services (1.4.1), including drinking water, appropriate sanitation, hygiene, waste management, and transportation [], was 35% in Iraq and 22% in Lebanon, compared to 15% in Jordan. Jordan has the lowest since it has less access to transportation, which affected the final percentage.

5.2. Goal 2: ‘End Hunger, Achieve Food Security and Improved Nutrition and Promote Sustainable Agriculture’ []

Of the respondents, 18% in Iraq and 16% in Jordan reported having undernourishment (2.1.1) compared to 61% in Lebanon, and 27% in Iraq, 13% in Jordan, and 36% in Lebanon reported having household members with malnutrition (2.2.2). However, since it is critical to estimate the indicators by people, we refer to previous studies collected from the study of Pernitez-Agan et al. [] (Table A5) (These numbers were only included in the first methods calculation, our data were used in the PCA). Iraq and Jordan respondents highlighted neutral about the access to safe, nutritious food they have all around the year, compared to respondents in Lebanon who reported somewhat bad access. A total of 27.2% in Iraq, 37.5% in Jordan and 17.3% in Lebanon have between somewhat good to very good accesses to food all around the year. Lebanon has significantly less access (Target 2.1). Our results are aligned with other studies [,,].

5.3. Goal 3: ‘Ensure Healthy Lives and Promote Well-Being for All at All Ages’ []

In Lebanon and Iraq, SRs access health care services through hospitals and primary health care centers. In Jordan, SRs have access to primary and some secondary health care inside their camp or in nearby hospitals. Most respondents, 58%, 77.4%, and 78.3% in Iraq, Jordan, and Lebanon, respectively, reported facing funding problems related to health issues during existence in the camp. A total of 60%, 38.7%, and 36.4%, respectively, reported not having constant access to needed medicine due to funding issues. Half of the respondents in Lebanon reported not being able to obtain medicine when needed, compared to 8.9% in Iraq and 16.1% in Jordan. A total of 35.5% in Jordan and 15.6% in Iraq reported that the needed medicine is not always available in the pharmacies in the camps. Further, 56.1% in Iraq and 66.7% in Jordan reported facing discrimination and inhumane attitudes among health care providers compared to 30% in Lebanon.

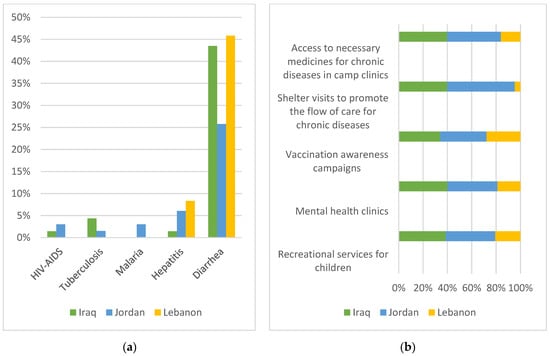

In total, 68%, 90%, and 65% of Iraq, Jordan, and Lebanon respondents, respectively, reported having documents that allow them access to public healthcare inside and outside the camp. One third of Iraq and Lebanon respondents did not have those documents. Figure 1a shows the prevalence of infections among refugees in the three countries.

Figure 1.

(a) The prevalence of infection; (b) access to essential health services in refugee camps, by country, based on the questionnaire results (Source: Authors).

Figure 1b presents access to essential health services (3.8.1). Only 4% in Iraq reported having access to the full list of essential health services compared to 10% in Jordan and 0% in Lebanon.

5.4. Goal 4: ‘Ensure Inclusive and Equitable Quality Education and Promote Lifelong Learning Opportunities for All’ []

Aligned with the provisions of SDG4, refugees must have access to primary and secondary education. Education is fundamental for further job opportunities [].

In total, 68% in Iraq and 90% in Jordan reported they and their children had completed primary and secondary education (Target 4.1). In contrast, only 15% in Lebanon answered affirmatively. Moreover, 80% in Iraq and 77% in Jordan who have children in the early childhood development (ECD) age said their children have access to ECD and pre-primary education services, compared to 17% in Lebanon.

In total, 50% in Iraq and 38% in Jordan reported having access to affordable and quality technical, vocational, or tertiary education (4.3.1) compared to 20% in Lebanon. Furthermore, 84% in Iraq, 78% in Jordan, and 57% in Lebanon stated they and their family members could read and make basic mathematical calculations (4.6.1).

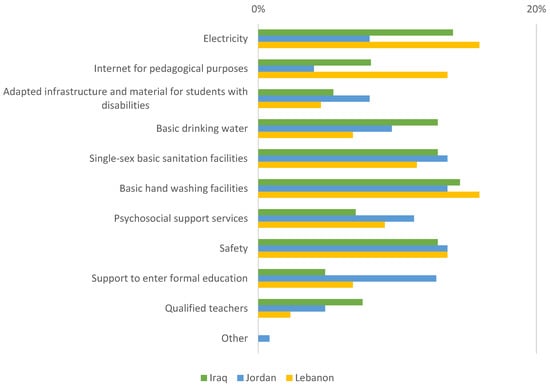

Figure 2 shows the basic services offered in schools (4.a.1). A total of 15% in Iraq reported their children do not have access to basic services in schools, compared to 10% in Jordan, and 30% in Lebanon. In opposition, 9% in Iraq reported their children to have access to all basic services, compared to 7% in Jordan, and 0% in Lebanon.

Figure 2.

Access to basic services in schools by country based on the questionnaire results (Source: Authors).

5.5. Goal 6: ‘Ensure Availability and Sustainable Management of Water and Sanitation for All’ []

In total, 91% in Iraq and 77% in Jordan and 59% in Lebanon reported having access to safe and affordable drinking water (6.1.1). Their host population has 60%, 80%, and 48% in Iraq, Jordan, and Lebanon, respectively [].

Furthermore, 87% in Jordan compared to 54% in Iraq and 46% in Lebanon reported having access to adequate and appropriate sanitation services (6.1.2a). The host population has 43%, 17%, and 82%, respectively []. All respondents in Lebanon reported having access to handwashing facilities with soap and water, compared to 98% and 87% of Iraq and Jordan respondents, respectively (6.2.1b).

Comparing our data to other studies, 87% of SR households in Lebanon have access to improved drinking water, 91% access to improved sanitation facilities. Yet, this percentage varied between governorates [], and it makes sense to be lower in the non-permanent shelters. Moreover, 100% proportion of the population in the Zaatari camp is using safely managed drinking water services. Safe water and wastewater networks were piped to all the households in the Zaatari camp and linked to a wastewater treatment plant []. However, the respondents who answered ‘no’ considered the water not clean to drink and some linked having diarrhea to the water quality. Moreover, they considered the wastewater network to not be well functioning due to the sewerage faults, such as the sewer being clogged.

5.6. Goal 7: ‘Ensure Access to Affordable, Reliable, Sustainable and Modern Energy for All’ []

Energy is required in all phases. It underpins several needs of displaced people in emergencies, including cooking, heating, protection, communication, etc. However, it is seen as a long-term intervention that does not fit in a humanitarian context [,].

All Lebanon and Jordan respondents reported having access to electricity (7.1.1), compared to 93% of Iraq respondents. Most respondents reported using gas for cooking, and 3.3% in Jordan reported using electricity. Hence, the majority of those RCs are using sustainable energy. Yet, in Iraq, 4.5% use charcoal, 2.3% use fuel wood, and 2.3% use fuel, although some of them are considered clean, they are picked from forests. Therefore, we considered them as not clean since this is associated with unsustainable forestry practices. Thus, 90.9%, 96.3%, and 100% in Iraq, Jordan, and Lebanon, respectively, are using clean fuels (7.1.2).

5.7. Goal 8: ‘Promote Sustained, Inclusive and Sustainable Economic Growth, Full and Productive Employment and Decent Work for All’ []

Although decent work and economic growth are stated in SDG8, refugees are dependent on charity or illegal work because of their host policy [].

Almost half of the respondents in all camps are unemployed (8.5.2). Additionally, 6.8% in Iraq and 20.8% in Lebanon indicate working without a work permit even though their work required one (8.5.2). When asking the respondents about the extent to which is easy to get a work permit on a seven-point Likert scale, all respondents in Lebanon and half in Iraq and Jordan found it rather difficult or extremely difficult. Furthermore, 5% of Iraq and 3.6% of Jordan respondents indicated that their main income comes from their children’s labor (8.7.1). Some disparities between gender exist where males reported having more access to work than females in the three countries, and especially in Iraq.

5.8. Goal 11: ‘Make Cities and Human Settlements Inclusive, Safe, Resilient and Sustainable’ []

Concerning the ‘proportion of urban population living in slums, informal settlements or inadequate housing’ (11.1.1) (This indicator was not included in the PCA, but only in the first methods calculation.), in 2018 this was 45.70%, 23.40%, and 61.10% in Iraq, Jordan, and Lebanon, respectively [].

More than half of Iraq respondents live in tents, followed by almost a third living in cement buildings or rooms with zinc/iron sheet roofs. Three quarters of Lebanon respondents live in tents, while most of Jordan respondents live in caravans. Generally, RCs failed to ensure access for all to adequate, safe, and affordable housing. Neither tents nor caravans were appropriate culturally, economically, or environmentally. Many refugees modified or repaired their shelters, and they do not feel well protected from high/low temperatures and rain.

In total, 76% and 65% of Iraq and Lebanon respondents, respectively, reported having access to public transport systems (11.2.1), compared to 23% of Jordan respondents. There is no public transportation inside the Zaatari camp despite its large area. Before COVID-19, refugees used to share a taxi to go to their destination within the camp. However, after COVID-19, taxis were not allowed to enter the camp. Therefore, refugees turned to using ‘Hantour’ which is a vehicle pulled by horses, which is not socially appropriate for women. This creates more difficulties to reach health centers and to socialize, affecting both SDG3 and SDG5.

5.9. Other Goals: Goal 5, Goal 10, Goal 16, and Goal 17

One in five refugee women is subjected to sexual violence in humanitarian settings []. This is reflected in our study where 20% of Iraq and Jordan women respondents reported facing a kind of physical, sexual, or psychological violence (5.2.2), compared to 30% of Lebanon women. This percentage presents the violence faced during the whole period spent in the camp. It indicates that women are not well protected in camps, especially in Lebanon. Only 32.6% in Iraq, 20.7% in Jordan, and 47.8% in Lebanon reported never facing any discrimination or harassment during their stay in the camp (10.3.1). This percentage presents the violence faced during the whole period spent in the camp. A total of 13.6% of Iraq respondents reported facing a kind of physical, sexual or psychological violence (16.1.3), compared to 31.3% and 22.7% in Jordan and Lebanon, respectively.

In total, 61%, 41%, and 35% of Iraq, Jordan, and Lebanon respondents, respectively, were not married at the time of answering the questionnaire. However, 13% in Iraq were married before 18 years (5.3.1), of which 2% were married before 15 years. Furthermore, 6% in Jordan were married under the age of 18 years, of which 3% were married under the age of 15 years. Among Lebanon respondents, 17% were married before 18 years old. According to [], child marriage before 18 was 24% in Iraq, 8% in Jordan, 6% in Lebanon, and 13% in Syria.

Asking about the extent to which refugees feel safe/secure in the streets of the camp (16.1.4), Iraq respondents reported feeling unsafe, compared to Jordan respondents who reported neutral feelings. Lebanon respondents felt strongly unsafe. Those differences are significant among the three countries. Almost all respondents reported having a mobile phone (5.b.1), and 67%, 50%, and 54% in Iraq, Jordan, and Lebanon, respectively have access to the internet (17.8.1).

At last, the refugee-related indicator (10.7.4) in Syria was 27,654.06 refugees per 100,000 of its population in 2020, compared to 822.12 in Iraq, 24.39 in Jordan, and 80.44 in Lebanon []. This was not included in our calculation because it is irrelevant to the RCs directly.

5.10. The Three Dimentions of Sustainability

Table 1 presents the percentage and ranking of the three dimensions of sustainability in the three countries. The results of the two methods were aligned indicating that Iraq ranked the best position in both social and economic dimensions, followed by Jordan and Lebanon. However, there is no statistical significance between the three countries. Jordan ranked the first position in the environmental dimension, followed by Iraq and Lebanon. In light of the statistical evidence, there is a significant difference between the three countries in terms of the environmental sustainability.

Table 1.

Sustainability dimensions ranking by countries, results of arithmetic mean methods and Kruskal–Wallis tests.

6. Discussion

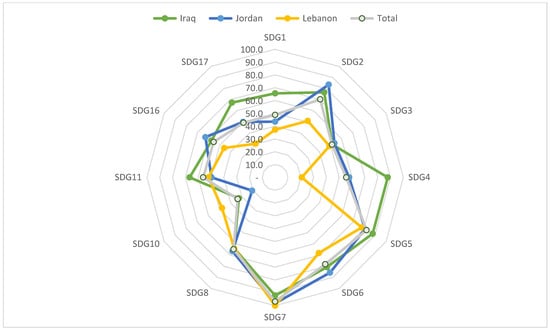

To better understand the level to which RCs are aligned to the SDGs, we display the average of studied indicators under each target of selected SDGs (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Overall index of selected SDGs in the three Middle East countries (Source: Authors).

Iraq is more than halfway through the ‘end poverty’ goal (SDG1). Iraq shows better development regarding this goal, due to its open-door policies that allow people to engage in work. Jordan and Lebanon are less than halfway to reaching ‘no poverty’ in RCs. Yet, considering statistical evidence, there is no significant difference between the three countries. Moreover, in the three countries, the situation of refugees is much worse compared to the nationals, especially in Jordan. This reflects the inequality, which is inconsistent with SDG10.

Inability to achieve SDG1 is directly connected to the lack of income-generating opportunities for refugees in RCs. The three countries are not obliged to give humanitarian refugees the right to work by law; however, even when refugees have the right to work, they have many constraints, including movement restrictions, cost of transportation from RCs location to job opportunities, time and cost of administrative procedure, and discrimination. Therefore, they seek informal work which exposes them to exploitative working conditions, lack of decent and dignified work, marginal wages, unsustainable livelihood, and tension with locals [,,]. SRs in Jordan and Lebanon are allowed to work in certain professions only, while in Iraq they can work without any conditions. Our results show that refugees have fewer opportunities to work and be paid equally, despite the Jordan compacts in 2016 and allowing Syrians in camps to register home-based businesses without the need for a Jordanian partner in 2018 []. Yet, few have registered because a valid passport is requested and the majority do not have one []. The results were not as expected due to the lack of job opportunities, refugees’ fear of losing humanitarian assistance or being relocated to a third country, or the lack of ability to afford the cost of a work permit []. Obtaining a work permit in Lebanon was significantly harder. Moreover, the gender gap was clear. The study of Bank and Fröhlich [] indicates that the majority of refugees that registered for a work permit after the compact were men, even though more than half of registered refugees are women. This also could be because women are obliged to work in agriculture in the nearby farms under the control of the landlord and the Shawish. The latter is the informal leader on the informal settlements. This shows a kind of neo-slavery or neo-feudalism that forces refugees to work for housing. Although the compact in Jordan cannot be considered a success because it lacked concrete implementation mechanisms at the beginning, it was a success compared to the failure of Lebanon. The latter lacked both implementation mechanisms and formal linkages between trade and refugee employment []. However, there was no significant difference related to SDG8 among the three countries according to the statistical evidence.

Poverty leads refugees to apply negative coping mechanisms, including informal work, accumulating debts, and food insecurity that affects achieving SDG2; child labor, early marriage, sexual work exploitation, and reducing expenditure on health and education [,] negatively affect the achieving of SDG3, SDG4 and SDG5. SRs in Lebanon were significantly more food insecure compared to Iraq and Jordan (Table A3). Moreover, food insecurity highlights again the inequality between refugees and hosts (SDG10) where food insecurity was higher between refugees followed by IDPs compared to their hosts. However, Lebanon was behind in the progress toward achieving SDG2 for both refugees and nationals. The more poverty there is, the more coping strategies are reported in the RCs. Additionally, the more fragile the host country, the more fragile the refugees.

SRs in Lebanon reported the highest percentage of early marriage followed by Iraq, and then Jordan. Child marriage reported by SRs in Lebanon was higher than in Lebanon and Syria. This could be connected to having worse living conditions, poverty, and food insecurity compared to Jordan and Iraq. Although child marriage leads to a delay in the achievement of SDG5, it has worse consequences, particularly increasing the risk of sexual and reproductive health, neonatal death and stillbirth, and sexually transmitted diseases [] which negatively affect the achievement of SDG3. Furthermore, it reduces children’s access to education (SDG4), especially girls, limiting their literacy abilities and future earnings [,,].

One in five households in Lebanon and Iraq indicated having child labor compared to one in seven households in Jordan, which negatively affects children’s access to education and achieving SDG4. The index of SDG4 for Iraq, Jordan, and Lebanon were 87.9, 57.8, and 20.8, respectively. The Kruskal–Wallis test suggests a different ranking for Jordan, followed by Iraq. However, Lebanon had a significantly worst situation (Table A3). Although Lebanon applied the policy of integrating refugee children into public schools, which is seen as the best for refugee education [], many obstacles exist, including the cost of transportation to school. The latter was the main issue reported in our questionnaire at the primary school level, aligned with the current pandemic of COVID-19, followed by the school not allowing children to be enrolled. One person reported having problems with the host community. At the secondary level, the most reported obstacle was the financial situation and the necessity to work followed by a lack of documents to enter schools. A recent study states that economic, cultural, and language aspects were significant strains, and the formal education system is not prepared to face these obstacles, creating inefficiencies in the educational system [].

Index of SDG3 and mean ranking show that RCs in the three camps are in parallel progress toward SDG3. There is no statistical difference between the three countries, but Lebanon was further behind (Table A3). The policy of each country was that Jordan and Iraq have free public healthcare services, while Lebanon provides primary healthcare access after registering with the UNHCR and subsidized primary healthcare services for refugees []. Yet, refugees face many obstacles to having quality health services. Hossain et al. [] indicated that global acute malnutrition is relatively low among SRs populations, while the prevalence of anemia suggests a serious public health problem among women and children, especially in the Zaatari camp, due to lack of nutrition. This takes us back to the importance of achieving SDG2, SDG1, SDG8, and SDG17, which could help overcome these health issues.

The prevalence of diarrhea reported was high in the three locations, mainly in Lebanon followed by Iraq. Hossain et al. [] stated the same in three countries mainly amongst younger children 0–23 months. The high prevalence of diarrhea is clearly related to insufficient access to WASH facilities, presented in SDG6. The index of SDG6 shows that Iraq and Jordan are more than three quarters ahead. This seems to be influenced by the existence of a sanitation network in the camp and that most respondents live in improved shelters and have access to better WASH services. Jordan shows a significantly lower percentage of diarrhea compared to Iraq and Lebanon. Half of the Iraq respondents live in improved tents and have access to sanitation facilities that are pits connected to the shelter, endangering the households, and creating concerns connected to health. The WASH sector in Lebanon seemed to be the worst, as only half of the respondents had access to safe and affordable drinking water and to sanitation services. Lebanon respondents informed the highest access to handwashing facilities. Yet, the concerns of WASH and health remain the highest in Lebanon and, in light of statistical evidence, there is a highly significant difference between the three countries (Table A3). RC in Jordan shows a slightly lower access to drinking water and sanitation compared to the country’s population, while in both Iraq and Lebanon RCs show a higher one. Sudan et al. reported that in most studied countries refugees have higher access to water and sanitation compared to nationals []. This reflects the extent to which WASH services provided in RCs are affected by the country’s status quo and its WASH management. However, although it shows the efforts that international community makes to provide WASH services to refugees, it raises an alert surrounding the efforts needed in WASH sectors worldwide, not only in RCs. Host governments should cooperate with international organizations to provide better WASH services for both refugees and their host community.

The index of SDG7 shows that the three locations have gone a long way toward this goal. Yet, we need to note that electricity is not provided 24 h a day. Regardless of the index, the situation in Jordan is more sustainable, since the electricity network is connected through a solar PV system covering the camp [,]. However, indicator 7.2.1 was not included in our assessment because there were no data in other locations. Based on the statistical evidence, there is no significant difference between the three countries (Table A3).

The Index of SDG11 was 66.7 for Iraq, 49.6 for Jordan, and 52.1 for Lebanon, and there was a highly significant difference between the three countries (Table A3). It highlighted a better situation in Iraq because of the policy applied that facilitates improved shelter. Yet, the selected indicators do not reflect the whole picture in those RCs. Public transportation is an essential need inside RCs, especially when it starts to be city-like, as in the case of the Zaatari where public transportation is vital. Moreover, rules post-COVID-19 exacerbated the problem and the gender gap. Additionally, thinking of the size, the location of the settlement, and how it is connected to nearby host communities when establishing the camp is essential. In both Iraq and Lebanon, the size of the settlements was not extremely large, as is the case of Zaatari, and were close enough to nearby countries to have the advantage of sharing the available public transportation.

The Index of SDG10 for Iraq, Jordan, and Lebanon shows 33, 21, and 48, respectively. However, the difference between the three countries was not significant. It seems that refugees are being or feeling discriminated against. Policies and procedures that reduce discrimination and prevent people, especially public officials and health workers, from being racist or discriminating against any refugee are important. The achievement of SDG10 affects and is affected by other SDGs, especially SDG3 and SDG4 in RCs. The index of SDG16 shows that the situations in Iraq and Jordan are better than Lebanon, which is slightly below half; however, there is no significant difference between them. The Index of SDG17 shows a significant difference between the three countries. The situation in Iraq is the best, followed by Jordan, then Lebanon.

In general, the two used methods indicate the exact results, especially when there is a significant difference among the countries, as is the case of SDG1, SDG 6, SDG11 and SDG17. It indicates a slightly different ranking, mainly between Iraq and Jordan when the results are too close to each other, and there is no significant difference among the countries, such as the case of SDG3, SDG5, SDG7, SDG8, SDG10, and SDG16. Although the result of SDG 2 and SDG 4 is significant, it shows a different ranking between Iraq and Jordan compared to the scores resulting from the arithmetic mean methods. However, the scores were very close in both methods and the significant difference related to Lebanon, which was the furthest behind. This reflects more credibility of our results.

Figure 3 shows the indices related to each SDG (see also Table A2). The overall index of the selected SDGs under this survey resulted from the arithmetic mean method as follows: 62.7 for Iraq, 67.2 for Jordan, and 53.7 for Lebanon. The situation in Iraq is the best at the social and economic sustainability levels, Jordan ranks the best in the environmental sustainability. The situation in Lebanon is the worst in all dimensions. The differences between the countries are significant at the environmental levels (Table 1). However, there is no significant difference at the overall index.

At last, some interesting implications can be drawn from this discussion:

The development of RCs is strongly linked to the development of their host countries, aligned with the policy applied. An enhanced approach in hosting neighboring countries is important to reduce the existing gaps in responding to the needs of refugees, the achievement of SDGs, and not leaving the refugees behind. This includes empowering the government institutions to ensure well-oriented policies and implementation. International support is vital for host countries to be able to support refugees. It is significant to check the ability of host countries to implement the agreed programs, and support and follow up with them to adapt their implementation means and policies to fit the directed targets and goals. Without the concrete efforts of the international community to support the refugees, we will not be able to accomplish the 2030 agenda and the ‘refugee gap’ may expand.

Host countries should promote policies that support decent work and equal payment for refugees and encourage the formalization of their work and the growth of entrepreneurship. This will bring advantages to both refugees and hosts. Moreover, it will help achieve refugees’ self-reliance and better integration, which play a vital role in creating stability and reducing tension with the host community. Host countries should take advantage of refugees’ human resources and acknowledge their certifications as proof of education to allow working. This will bring the workforce to the host country and will reduce poverty levels, aid dependency, and the long-term burden of providing nonrefundable sources of basic services, such as food assistance, health care, and access to education, etc. International communities, governments, and private sectors should create more job opportunities for both refugee and their host.

There should be intersectoral collaboration and partnerships between different parties, encompassing governmental and non-governmental institutions, private sector, civil society, and the international community to promote the SDGs’ ambitions of leaving no one behind and promoting quality access to basic needs, including health, education and water and sanitation.

Increasing quality data availability on refugees both in camps and urban areas at all levels, international, regional, national, and local, and starting to include them in the national statistics and statistics related to SDGs are important to help decision makers to understand refugees’ needs. Particularly, it will help to achieve the SDGs, monitor the progress toward the implementation of 2030 agenda, and increase the accountability of governments and service providers.

All the world has been affected by COVID-19; however, the more the population was vulnerable, the more affected they were, because they are more fragile and less resilient. Our research shows that COVID-19 affected the achievement of SDG1, SDG2, SDG3, SDG4, SDG5, SDG8, SDG10, and SDG11 (access to transportation). This highlights the need for more cooperation and partnerships between policymakers and other stakeholders to build and rebuild resilient and sustainable communities after crises and disasters.

Finally, changing the game from humanitarian assistance to development is crucial. Decision makers, donors, host countries, and all involved parties should start applying development programs related to refugees in camps. It is vital to understand that humanitarian work alone is not effective, especially in the long term. Integrating refugees into national plans and programs should be considered, particularly when it comes to the 2030 agenda and leaving no one behind.

7. Conclusions

This study presents the extent to which RCs are aligned with SDGs. For this reason, we have used the data extracted from a questionnaire conducted in RCs in three Middle East countries and previous studies to validate our results and findings. The study relied on a set of SDGs indicators applicable in a RC set. The achieved results showed that there is a gap related to the achievement of SDGs in RCs, due to the difficulty of introducing a huge influx of refugees to local services including health, education, and the job market, in countries that are barely able to manage their population’s needs. Moreover, the lack of implementation policies, where even with support provided from the international community, host countries, such as Lebanon, still failed to integrate the refugees well. The situation in Lebanon was the worst in terms of social, economic, and environmental sustainability. Policies applied in the host country affect at once the quality of life, dignity, and self-reliance of the refugees and accelerate or burden the achievement of the 2030 agenda. Further investigation is needed to improve the current form of humanitarian response, mainly the implementation within host governments. Host countries should start to implement a more inclusive approach that pushes ahead the integration of refugees into the community and workforce instead of being a burden on their hosts and the international community. At last, it is crucial to provide data on SDGs indicators about refugees and in RCs to help decision makers mentor and evaluate their decisions to enable those that are further behind to catch up and to accelerate the process toward achieving the 2030 agenda.

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of refugee perceptions for the targeted themes covered in the study and in the locations in which it was conducted. The study has several limitations:

- Due to the travel limitations at the time of carrying out this study, the authors were not able to travel and conduct face-to-face questionnaires, interviews, or observations of the status quo;

- Sensitivity of results: not all the indicators from the full SDG list were segregated or included, which results in having scores that might be higher/lower than if the full list was included. This affects the final score, especially when the number of studied indicators is relatively low. Additionally, sensitivity analyses are needed to give guidance regarding the most valuable indicators that would accelerate the achievement of the 2030 agenda;

- Even though the arithmetic mean method has credible advantages of unifying the performance of each SDG, it has some limitations including sensitivity to extreme values, and using equal wights may result in a skewness toward a specific SDG []. Moreover, PCA has a limitation related to assuming a linear relation between variables, which make the components less interpretable than the original []. Other methods are encouraged to be explored in further research, including data envelopment analysis (DEA) [] and integrated PCA and DEA []

- Identifying the social, economic, and environmental sustainability indicators and SDGs is still not well defined in the literature, and requires further research and may reflect in different rankings when considering different approach;

- The captured information is based primarily on data from individuals’ responses from specific locations. It does not statistically represent the views of the entire refugee population, nor do they cover all countries. However, most of the issues raised throughout this study are indicative of the general targets linked to SDGs and the challenges and gaps that refugees in Syria’s bordering countries face.

Author Contributions

M.W. conceptualized the idea and methodology of the research presented above. M.W. and R.C.M. designed the questionnaire. M.W. carried out the data collection, investigation, software, analysis, and wrote the first draft of the article. R.C.M. supervised the research, reviewed, validated, and edited the first draft. Both authors contributed to subsequent drafts, which gave the manuscript its final form. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors are grateful for the Foundation for Science and Technology’s support through funding UIDB/04625/2020 from the research unit CERIS.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The first author would like to thank the generous support of her Global Platform for Syrian Students scholarship. Moreover, she would like to thank friends, people, organizations including but not limited to Ola Aljounde, Khaled Khansa and Gharsah Association, Tareq Awwad and Syrian Eyes, Hala Ali Abdulrazaq and Ahmed Alhusri for their generous help to complete the questionnaire presented in this study. After all, our biggest thank you goes to the communities who filled out the questionnaire for their generosity to participate in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Summary of refugee camp related SDGs, targets, and respective indicators.

Table A1.

Summary of refugee camp related SDGs, targets, and respective indicators.

| SDG | Target | Indicator |

|---|---|---|

| SDG1: ‘End poverty in all its forms everywhere’ | 1.1 By 2030, eradicate extreme poverty for all people everywhere, currently measured as people living on less than USD 1.90 a day | 1.1.1 Proportion of the population living below the international poverty line by sex, age, employment status and geographic location (urban/rural) |

| 1.2 By 2030, reduce at least by half the proportion of men, women and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions according to national definitions | 1.2.1 Proportion of population living below the national poverty line, by sex and age | |

| 1.4 By 2030, ensure that all men and women, in particular the poor and the vulnerable, have equal rights to economic resources, as well as access to basic services | 1.4.1 Proportion of population living in households with access to basic services | |

| SDG2: ‘End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture’ | 2.1 By 2030, end hunger and ensure access by all people, in particular the poor and people in vulnerable situations, including infants, to safe, nutritious and sufficient food all year round | 2.1.1 Prevalence of undernourishment |

| 2.1.2 Prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity in the population, based on the Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES) | ||

| 2.2 By 2030, end all forms of malnutrition, including achieving, by 2025, the internationally agreed targets on stunting and wasting in children under 5 years of age, and address the nutritional needs of adolescent girls, pregnant and | 2.2.1 Prevalence of stunting among children under 5 years of age | |

| 2.2.2 Prevalence of malnutrition among children under 5 years of age, by type (wasting and overweight). | ||

| SDG3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all age | 3.3 By 2030, end the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and neglected tropical diseases and combat hepatitis, water-borne diseases and other communicable diseases | 3.3.1 Number of new HIV infections per 1000 uninfected population, by sex, age and key populations |

| 3.3.2 Tuberculosis incidence per 100,000 population | ||

| 3.3.3 Malaria incidence per 1000 population | ||

| 3.3.4 Hepatitis B incidence per 100,000 population | ||

| 3.8 Achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all | 3.8.1 Coverage of essential health services | |

| Goal4: ‘Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all’ | 4.1 By 2030, ensure that all girls and boys complete free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education leading to relevant and effective learning outcomes | 4.1.2 Completion rate (primary education, lower secondary education, upper secondary education) |

| 4.2 By 2030, ensure that all girls and boys have access to quality early childhood development, care and pre-primary education so that they are ready for primary education | 4.2.2 Participation rate in organized learning (one year before the official primary entry age), by sex | |

| 4.3 By 2030, ensure equal access for all women and men to affordable and quality technical, vocational and tertiary education, including university | 4.3.1 Participation rate of youth and adults in formal and non-formal education and training in the previous 12 months, by sex | |

| 4.6 By 2030, ensure that all youth and a substantial proportion of adults, both men and women, achieve literacy and numeracy | 4.6.1 Proportion of population in a given age group achieving at least a fixed level of proficiency in functional (a) literacy and (b) numeracy skills, by sex | |

| 4.a Build and upgrade education facilities that are child, disability and gender sensitive and provide safe, non-violent, inclusive and effective learning environments for all | 4.a.1 Proportion of schools offering basic services, by type of service | |

| Goal5: ‘Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls’ | 5.2 Eliminate all forms of violence against all women and girls in the public and private spheres, including trafficking and sexual and other types of exploitation | 5.2.2 Proportion of women and girls aged 15 years and older subjected to sexual violence by persons other than an intimate partner in the previous 12 months, by age and place of occurrence |

| 5.3 Eliminate all harmful practices, such as child, early and forced marriage and female genital mutilation | 5.3.1 Proportion of women aged 20–24 years who were married or in a union before age 15 and before age 18 | |

| 5.b Enhance the use of enabling technology, in particular information and communication technology, to promote the empowerment of women | 5.b.1 Proportion of individuals who own a mobile telephone, by sex | |

| Goal6: ‘Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all’ | 6.1 By 2030, achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all | 6.1.1 Proportion of population using safely managed drinking water services |

| 6.2 By 2030, achieve access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all and end open defecation, paying special attention to the needs of women and girls and those in vulnerable situations | 6.2.1 Proportion of population using (a) safely managed sanitation services and (b) a hand-washing facility with soap and water | |

| Goal7: ‘Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all’ | 7.1 By 2030, ensure universal access to affordable, reliable and modern energy services | 7.1.1 Proportion of population with access to electricity |

| 7.1.2 Proportion of population with primary reliance on clean fuels and technology | ||

| Goal8: Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all | 8.5 By 2030, achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men, including for young people and persons with disabilities, and equal pay for work of equal value | 8.5.2 Unemployment rate, by sex, age and persons with disabilities |

| 8.7 Take immediate and effective measures to eradicate forced labour, end modern slavery and human trafficking and secure the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labor, including recruitment and use of child soldiers, and by 2025 end child labor in all its forms | 8.7.1 Proportion and number of children aged 5–17 years engaged in child labor, by sex and age | |

| Goal10: Reduce inequality within and among countries | 10.3 Ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome, including by eliminating discriminatory laws, policies and practices and promoting appropriate legislation, policies and action in this regard | 10.3.1 Proportion of population reporting having personally felt discriminated against or harassed in the previous 12 months on the basis of a ground of discrimination prohibited under international human rights law |

| 10.7 Facilitate orderly, safe, regular and responsible migration and mobility of people, including through the implementation of planned and well-managed migration policies | 10.7.4 Proportion of the population who are refugees, by country of origin | |

| Goal11: ‘make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable’ | 11.1 By 2030, ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services and upgrade slums | 11.1.1 Proportion of urban population living in slums, informal settlements or inadequate housing |

| 11.2 By 2030, provide access to safe, affordable, accessible and sustainable transport systems for all, improving road safety, notably by expanding public transport, with special attention to the needs of those in vulnerable situations, women, children, persons with disabilities and older persons. 16.1 Significantly reduce all forms of violence and related death rates everywhere | 11.2.1 Proportion of population that has convenient access to public transport, by sex, age and persons with disabilities | |

| Goal16: ‘Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels’ | 16.1.3 Proportion of population subjected to (a) physical violence, (b) psychological violence and (c) sexual violence in the previous 12 months | |

| 16.1.4 Proportion of population that feel safe walking alone around the area they live | ||

| Goal17: ‘Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development’ | 17.8 Fully operationalize the technology bank and science, technology and innovation capacity-building mechanism for least developed countries by 2017 and enhance the use of enabling technology, in particular information and communications technology | 17.8.1 Proportion of individuals using the Internet |

Table A2.

Overall Index for Sustainable Development Goals, results of arithmetic mean methods.

Table A2.

Overall Index for Sustainable Development Goals, results of arithmetic mean methods.

| Iraq | Jordan | Lebanon | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Score for each SDG | GOAL1 End poverty in all its forms everywhere | 65.6 | 43.5 | 37.2 | 48.8 |

| GOAL2 End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture | 76.7 | 83.6 | 50.9 | 70.4 | |

| GOAL3 Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages | 51.4 | 53.5 | 49.0 | 51.3 | |

| GOAL4 Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all | 87.9 | 57.8 | 20.8 | 55.5 | |

| GOAL5 Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls | 87.9 | 81.0 | 78.1 | 82.3 | |

| GOAL6 Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all | 80.8 | 85.7 | 68.2 | 78.2 | |

| GOAL7 Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all | 92.1 | 98.2 | 100.0 | 96.8 | |

| GOAL8 Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all | 63.9 | 66.5 | 63.9 | 64.8 | |

| GOAL10 Reduce inequality within and among countries | 32.6 | 20.7 | 47.8 | 33.7 | |

| GOAL11 Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable | 66.7 | 49.6 | 52.1 | 56.1 | |

| GOAL16 Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels | 57.3 | 62.8 | 45.9 | 55.3 | |

| GOAL17 Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development | 67.4 | 50.0 | 30.4 | 49.3 | |

| Average | 69.2 | 62.7 | 53.7 | 61.9 | |

Table A3.

SDG Mean ranking by countries, results of Kruskal–Wallis Test.

Table A3.

SDG Mean ranking by countries, results of Kruskal–Wallis Test.

| SDG | SDG1 | SDG2 | SDG3 | SDG4 | SDG5 | SDG6 | SDG7 | SDG8 | SDG10 | SDG11 | SDG16 | SDG17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iraq | 46.84 | 53.73 | 55.78 | 29.95 | 43.48 | 44.53 | 45.68 | 42.41 | 52.89 | 59.66 | 51.52 | 56.86 |

| Jordan | 38.61 | 53.68 | 47.39 | 39.84 | 55.83 | 54.00 | 50.00 | 50.47 | 43.85 | 31.90 | 44.18 | 48.25 |

| Lebanon | 35.29 | 29.05 | 46.46.5 | 13.13 | 46.73 | 33.52 | 50.00 | 46.64 | 48.48 | 54.28 | 38.50 | 38.57 |

| p-Value | 0.139 | 0.001 ** | 0.167 | 0.001 ** | 0.136 | 0.009 ** | 0.091 | 0.396 | 0.157 | 0.001 ** | 0.121 | 0.014 * |

** Significant at 1% level; * Significant at 5% level. The underlined values present different country’s ranking from that presented when using the arithmetic mean methods.

Appendix B

Table A4.

Data related to respondents and SDGs indicators and targets.

Table A4.

Data related to respondents and SDGs indicators and targets.

| Related Question/Indicator | Iraq | Jordan | Lebanon | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 50.00% | 64.5% | 50.00% | 54.20% |

| Male | 50.00% | 35.50% | 50.00% | 44.80% | |

| Prefer not to say | 00.00% | 03.10% | 00.00% | 01.00% | |

| Marital status | Married | 46.30% | 59.40% | 76.20% | 57.40% |

| Single | 43.90% | 34.40% | 19.00% | 35.10% | |

| Other | 09.80% | 06.30% | 04.80% | 07.40% | |

| Daily income per person per day | Less than USD 1 | 25.00% | 20.70% | 23.80% | 23.20% |

| Between USD (1–2) | 12.50% | 34.50% | 38.10% | 26.80% | |

| Between USD (2–3) | 6.20% | 3.40% | 14.3 | 7.30% | |

| Between USD (3–5) | 15.40% | 17.30% | 9.50% | 14.70% | |

| Between USD (5–10) | 31.30% | 13.80% | 9.50% | 19.50% | |

| More than USD 10 | 9.40% | 6.90% | 4.80% | 7.30% | |

| Other | 0.00% | 3.40% | 0.00% | 1.20% | |

| Access to basic services | No access | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Access to some services | 65.20% | 84.40% | 78.30% | 74.30% | |

| Access to all services | 34.80% | 15.60% | 21.70% | 25.70% | |

| Undernourishment | No | 65.90% | 71.00% | 17.40% | 56.10% |

| Yes | 18.20% | 16.10% | 60.90% | 27.60% | |

| Maybe | 15.90% | 12.90% | 21.70% | 16.30% | |

| Household malnutrition, stunting, and wasting | No | 73.30% | 83.90% | 63.60% | 74.50% |

| Yes | 26.70% | 12.90% | 36.40% | 24.50% | |

| Other | 0.00% | 3.20% | 0.00% | 1.00% | |

| Access to safe, nutritious and sufficient food all year round | Valid | 44 | 31 | 23 | |

| Missing | 2 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Mean | 4.07 | 4.1 | 3.09 | ||

| Median | 4 | 4 | 3 | ||

| Mode | 4 | 3 | 3 | ||

| Range | 6 | 6 | 5 | ||

| Minimum | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Maximum | 7 | 7 | 6 | ||

| Food insecurity for Syrian refugees and their host countries | Syrian refugee/Camp level | 32.9% 1 | 21% 2 | 50% 3 | 1 (The World Bank, FAO, IFAD, and WFP, 2021), 2 (The World Bank, FAO, IFAD, and WFP, 2020), 3 (WFP, 2021) |

| National/Host level | 4.7% 1 | 3% 2 | 34% 3 | ||

| IDP | 17.5% 1 | ||||

| Access to essential health services | No | 15.20% | 10.30% | 17.40% | 14.30% |

| At least one service | 80.40% | 79.30% | 82.60% | 80.60% | |

| Yes, All services | 4.30% | 10.30% | 0.00% | 5.10% | |

| Completion of primary and secondary education | No | 28.60% | 10.00% | 85.00% | 39.70% |

| Yes | 67.90% | 90.00% | 10.00% | 57.40% | |

| Other | 3.60% | 0.00% | 5.00% | 2.90% | |

| Access to early childhood development and pre-primary education that prepare them for primary education | No | 20.00% | 23.10% | 83.30% | 42.90% |

| Yes | 80.00% | 76.90% | 16.70% | 57.10% | |

| Access to affordable and quality technical, vocational or tertiary education, including university | No | 50.00% | 46.90% | 80.00% | 56.00% |

| Yes | 50.00% | 37.50% | 20.00% | 38.10% | |

| Other | 0.00% | 15.60% | 0.00% | 6.00% | |

| Household members are not able to read or do basic mathematical calculations | No | 83.70% | 78.10% | 57.10% | 76.00% |

| Yes | 16.30% | 15.60% | 42.90% | 21.90% | |

| Other | 0.00% | 6.30% | 0.00% | 2.10% | |

| Access to basic services in schools | No | 15.20% | 9.70% | 30.40% | 17.00% |

| Yes | 8.70% | 6.50% | 0.00% | 6.00% | |

| Partial | 76.10% | 83.90% | 69.60% | 77.00% | |

| Access to safe and affordable drinking water | No | 9.10% | 22.60% | 40.90% | 20.60% |

| Yes | 90.90% | 77.40% | 59.10% | 79.40% | |

| Access to washing hand facility with soap and water | No | 2.40% | 6.70% | 0.00% | 5.30% |

| Yes | 97.60% | 93.30% | 100.00% | 94.70% | |

| Access to adequate and appropriate sanitation services | No | 46.10% | 13.30% | 54.50% | 37.40% |

| Yes | 53.90% | 86.70% | 45.50% | 62.60% | |

| Access to electricity | No | 6.80% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 5.20% |

| Yes | 93.20% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 94.80% | |

| Energy used for cooking requirement by type and country | Charcoal | 2.30% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 1.00% |

| Electricity | 0.00% | 3.30% | 0.00% | 1.00% | |

| Fuel wood | 4.50% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 2.10% | |

| Fuel | 2.30% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 1.00% | |

| Gas | 90.90% | 93.30% | 100.00% | 93.80% | |

| Other | 0.00% | 3.30% | 0.00% | 1.00% | |

| How energy requirements for cooking are obtained | Humanitarian assistance | 19.60% | 46.70% | 13.00% | 26.30% |

| Picked from nearby forest locations | 4.30% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 2.00% | |

| Picked from distant forest locations | 2.20% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 1.00% | |

| Purchase/Paid yourself | 80.40% | 76.70% | 78.30% | 78.80% | |

| Exchange food shares for energy source | 4.30% | 6.70% | 0.00% | 4.00% | |

| Unemployment rate | Self-employed | 9.10% | 3.10% | 4.20% | 6% |

| Employee in the host country government | 6.80% | 3.10% | 0% | 4% | |

| Employee in private company | 11.40% | 6.30% | 8.30% | 9% | |

| Employee with international humanitarian organization | 11.40% | 28.10% | 4.20% | 15% | |

| Agriculture | 2.30% | 6.30% | 4.20% | 4% | |

| Housekeeper | 18.20% | 18.80% | 33.30% | 22% | |

| Working without official work permit | 6.80% | 0% | 20.80% | 8% | |

| I do not have work | 34.10% | 34.40% | 20.80% | 31% | |

| Other | 0% | 0% | 4.20% | 1% | |

| Child Labor | No | 80.00% | 86.20% | 81.80% | 82.40% |

| Yes | 20.00% | 13.80% | 18.20% | 17.60% | |

| Type of shelters | A building which is part of residential compound | 9.10% | 3.10% | 4.50% | 6.10% |

| Caravans | 6.80% | 90.60% | 0.00% | 32.70% | |

| Cement building with zinc/iron sheets roof | 20.50% | 0.00% | 4.50% | 10.20% | |

| Combined both caravans and tents | 0.00% | 3.10% | 0.00% | 1.00% | |

| Interlocking stabilized soil blocks | 2.30% | 0.00% | 9.10% | 3.10% | |

| Room made of stone, block, or brick with zinc or iron sheets roof | 4.50% | 0.00% | 4.50% | 3.10% | |

| Tent | 54.50% | 3.10% | 77.30% | 42.90% | |

| Transitional structures made of wooden poles, and iron sheets roof or polythene | 2.30% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 1.00% | |

| Access to public transport systems | No | 23.90% | 77.40% | 34.80% | 43.00% |

| Yes | 76.10% | 22.60% | 65.20% | 57.00% | |

| Women faced any physical, sexual, or psychological violence | No | 80.00% | 80.00% | 70.00% | 78.00% |

| Yes | 20.00% | 20.00% | 30.00% | 22.00% | |

| Faced any physical, sexual, or psychological violence | No | 86.40% | 68.70% | 77.30% | 78.60% |

| Yes | 13.60% | 31.30% | 22.70% | 21.40% | |

| Faced discrimination or harassment | No | 32.60% | 20.70% | 47.80% | 32.70% |

| Yes | 67.40% | 79.30% | 52.20% | 0.673 | |

| Child marriage | Under 15 years old | 2.20% | 3.10% | 0.00% | 2.00% |

| Under 18 years old | 10.90% | 3.10% | 17.40% | 9.90% | |

| 18 years old and above | 26.10% | 53.10% | 47.80% | 39.60% | |

| Not married | 60.90% | 40.60% | 34.80% | 48.50% | |

| Feel secure/safe in the streets of the camp | Valid | 38 | 31 | 19 | |

| Missing | 8 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Mean | 2.58 * | 4.26 * | 1.32 * | ||

| Median | 2 | 4 | 1 | ||

| Std. Deviation | 1.464 | 1.932 | 0.582 | ||

| Range | 5 | 6 | 2 | ||

| Minimum | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Maximum | 6 | 7 | 3 | ||

| Access to mobile phone | No | 0.00% | 0.00% | 5.00% | 1.70% |

| Yes | 100% | 100% | 95% | 98.30% | |

| Access to Internet | No | 32.60% | 50.00% | 69.60% | 46.50% |

| Yes | 67.40% | 50.00% | 30.40% | 53.50% |

* Significant at 5% level.

Table A5.

Malnutrition, stunting, and wasting.

Table A5.

Malnutrition, stunting, and wasting.

| Year of Survey | Iraq—Domiz Camp | Jordan—Alzaatari Camp | Lebanon—Beqaa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wasting % (95% CI) | 2015–2016 | 9.5% 1 | 4.1% 1 | 2.4% 1 |

| 2013 | 4.1% 2 | 1.2% 2 | 4.4% 2 | |

| Stunting % (95% CI) | 2015–2016 | 7.4% 1 | 7.4% 1 | 9.6% 1 |

| 2013 | 19.0% 2 | 16.7% 2 | 21.0% 2 | |

| Overweight and Obesity | 2015–2016 | 6.1% 1 | 11.9% 1 | 11.9% 1 |

| 2016 | - | 1.6% 3 | - |

1 Pernitez-Agan et. al. 2019 []; 2 Hossain 2013 []; 3 UNHCR 2016 from [].

References

- Amnesty International. An International Failure: The Syrian Refugee Crisis. Amnesty Int. 2013. Available online: https://www.amnesty.ca/sites/amnesty/files/an_international_failure_-_the_syrian_refugee_crisis.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- UNHCR. Situation Syria Regional Refugee Response. 2020. Available online: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/syria/location/53 (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- UNHCR. 2020 Annual Report, Regional Refugee and Resilience Plan in Response to the Syria Crisis May 2021. 2020. Available online: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/86636 (accessed on 8 January 2022).