Abstract

Appropriate governance structures are extremely important for fishery-dependent communities in developing integrated territorial development strategies and an adaptive capacity for change, including a climate one. This paper assesses to what extent fishery co-management schemes (e.g., fishery LAGs, being regional/local governance instruments in fishing communities) are strengthening sustainability. The latter includes improving energy efficiency, promoting renewable energy sources (RES), coping with the climate crisis, minimizing environmental impacts, and promoting a sustainable blue economy. For detecting the policy aspects of aligning climate neutrality and a sustainable blue economy, the research lens focuses on the Greek Fisheries Local Action Groups (FLAGs), given that these are mostly located in coastal/marine and insular territories with significant blue growth potential. To map and assess their capacity and efficiency in pursuing Green Deal objectives, a co-development process with FLAG managers was put in place. The results and findings of this process reveal the scarcity of sustainability and blue-economy-related strategies. The key conclusion is that a transition to a post-carbon blue economy on a local level requires an understanding of the evolutionary dynamics of fishery co-management schemes. The latter, being multi-sectoral structures, may boost dialogue and cooperation to harmonize local development strategies and EU policies. Maritime spatial planning (MSP), as an evolutionary governance process itself, can be a driver for making FLAGs evolve and strengthen commonization, blue justice, and equity for fishers.

1. Introduction

Fish and their habitats have been always considered in terms of their vulnerability to marine ecosystem and climate changes. The vulnerability patterns of fishing tradition to climate change are defined by the capacity of fishers to adapt to this change, the ongoing changes to ecosystems, and the yield of the fishing activity. Furthermore, the literature [1,2,3] reports that a rise in temperature affects the abundance, mortality rates, and migratory patterns of fish stocks and defines the kind of species that can be grown in aquaculture farms of certain regions [4]. The consequent socio-economic impacts for local communities dependent on fisheries and aquaculture—meaning the whole market ecosystem—continue to expand. Whilst most work on climate change in fisheries has focused on marine biology, it is of paramount importance to highlight the policy aspects of adapting the fisheries sector to marine ecosystem and climate change [3,4], with a focus on coastal artisanal fisheries. Hence, adaptation strategies should be developed considering the economic impacts of climate change. These strategies should be flexible enough to adapt to the uncertainties of the climate crisis. For the fishing and aquaculture sectors to be sustainable, both the global and local governance of fisheries should be strengthened [4]. On the local level, this should include building the knowledge base of stakeholders about how climate change will affect these fisheries [4]. This knowledge may then suitably inform local strategies [4].

Of course, adaptive capacity for climate change is differentiated across and within fishing communities. It is defined partly by relevant resources, networking, available technology levels, and mainly appropriate governance structures. Building this adaptive capacity can reduce vulnerability to a wide variety of impacts, many of which are unpredictable.

Therefore, the key role for state and local governments is to enable adaptive capacity and resilience within vulnerable communities. There are a wide range of potential adaptation options for fisheries, but also considerable constraints on their implementation by the actors involved, despite their potential benefits [5,6]. Governments are often led to trade-offs between increasing efficiency, targeting the most vulnerable, and building the resilience of the whole system.

The aim of the present paper is to deal with the policy aspects of adapting fisheries to the new realm of climate neutrality, as addressed by the European Green Deal (hereinafter EGD). The Green Deal is the new European growth strategy, which is aimed at metamorphosing the EU into a competitive economy, decoupling economic growth from resource use. The EGD provides a set of actions to restore biodiversity, reduce pollution, and encourage the efficient use of resources by moving to a clean, circular economy. It outlines the investments needed and the financing tools available and clarifies how to achieve a just and inclusive transition. Therefore, the aim of this paper is two-fold:

- (a)

- First, to assess to what extent fishery co-management schemes—as regional/local governance schemes in fishing communities on a pan-European scale—are strengthening sustainability, i.e, coping with the climate crisis, improving energy efficiency, promoting renewable energies, minimizing environmental impacts, and promoting a sustainable blue economy. This is achieved through a mix of qualitative and quantitative research.

- (b)

- Second, to discuss the challenges and potential opportunities created by maritime spatial planning (hereinafter MSP) for enhanced fishery co-management and vice versa [7]. The question is whether the latter, defined as “the collaborative and participatory process of regulatory decision-making among representatives of resource user-groups, government agencies and research institutions” [8], could also be, through its robust network, the critical mass of a “Blue Forum” consisting of stakeholders, scientists, and off-shore operators such as the one planned by the European Commission to promote a sustainable blue economy in the EU [9]. The Commission, intending to expand the necessary dialogue between different sea users, is currently setting up a Blue Forum for sea users in 2022 and offers permanent assistance for MSP, also through the MSP Assistance Mechanism [10].

As a case study for detecting the policy aspects of aligning climate neutrality and a sustainable blue economy, this research lens focuses on the Greek Fisheries Local Action Groups (hereinafter FLAGs), given that these are mostly located in coastal/marine and insular territories with significant blue growth potential. Land and sea, in the Greek context, are strongly interdependent entities. Therefore, their efficiency in pursuing the Green Deal goals has been mapped through a co-development process with FLAG managers, who were asked to assess the Community Led Local Development Strategies (hereinafter CLLD strategies) 2014–2020 and provide prospects for the next period (2021–2027). The assessment also concerns the reforms that may be required for established co-management/governance schemes, in order to make them enablers of a sustainable blue economy and MSP. Special focus is given to small-scale fishery (hereinafter SSF) communities and to their role in the implementation of the Green Deal Strategy (hereinafter GDS), since the latter addresses regional and local territorial development strategies [11].

2. Setting the Scene: The Evolution of Fisheries Co-Management Endeavors

2.1. The Place of Greek Fishery and Aquaculture Sectors in EU-27

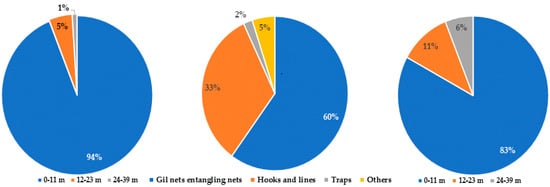

Greece, with a coastline of 15.021 km (covering more than 6000 islands and islets), has a longstanding tradition in the fishery and maritime sectors. Despite its limited contribution to the gross domestic product (less than 3.1%), the Greek fisheries industry represents a primary sector of substantial socio-economic and socio-cultural weight, particularly in coastal/island areas, which are traditionally fishery-dependent areas. Both the fishery and aquaculture industries carry out essential activities in economic, social, and ecological terms. Fish production is noteworthy, i.e., 0.2 million tons of fish in 2018 (including mollusks and shellfish), 80% of which comes from aquaculture and 20% from fisheries [12]. Precisely, in 2021, Greece ranked first among the 27 EU MS, with its fishing fleet representing 19.5% of the EU total, the combined gross tonnage denoting 5.2% of the EU-27, and the total engine power representing 7.8% of the EU-27 total [13]. However, the length of the Greek fishing fleet is 0–11m, in its great majority (94%, see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Greek fishing fleet by length, type of gear, and jobs, 2019 (% of total number of vessels), source: [14].

However, the size of this fishing fleet saw a dramatic decrease compared to its size a decade ago (2011:16.866 vessels noting a decrease of 13.5%), while during the same period, the total tonnage and total engine power also declined (noting decreases of 20.1% and 20.4%, correspondingly) [15]. The key reasons interpreting this shrinkage are: the ageing of the fishers’ population, the absence of an attractive motive for successors to stay in business [16,17], in parallel with conflicts between SSFs and aquaculture activities [18], high inactivity faced mainly by SSFs, together with a reduction in catches’ value due to overfishing, in combination with competition with amateur and retired fishers [19]. In addition, Greece ranks third among the 27 EU member states (hereinafter MS) in terms of fisheries employment (2019), consisting of 16.109 jobs [2], with a very low annual wage per full-time equivalent and total employed (EUR 10.322 and EUR 7.774, respectively in 2019) [16].

Regarding aquaculture, Greece is amongst the five EU MS that produce almost three quarters of the total aquaculture production, both in quantity (9.42% of EU-27) and value (10.19% of EU-27). In terms of employment in aquaculture, Greece ranks third among the 27 MS with a total of 3.524 jobs (2018) [20]. Regarding the fleet structure in 2020, it has been pointed out that 96.5% of the total regards small-scale vessels (13.763 vessels), while the remaining 3.5% (484 vessels) refers to a large-scale fleet. In the same year, 38.6% of the Greek annual fish production was obtained by SSFs, whilst this value referred to 57.6% of the total value of fishing production [20]. SSFs provide 19,396 full-time jobs, ranking Greece as the third country in the EU in terms of employment in the industry [21]. Most of these jobs are in remote and insular territories (see Figure 2), where there are often no alternate livelihood prospects and income streams. Greek SSFs, representing 96.5% of the total fishing fleet, also denote the largest share of the total SSFs in the EU [22]. However, they manage to access only 16.6% of the total purchasers, thereby obtaining only a small fraction of the profits [23].

For communities highly dependent on fisheries, SSF activity is often their main livelihood opportunity, representing a crucial sector for coastal and insular areas [24]. Specifically, coastal communities settled in remote areas, such as small Aegean islands, are entirely dependent on SSF activities, which are often family-run businesses or made up of self-employed workers, where, in most of the cases, the shipowner is also the chief in the vessel [25]. Energy costs represent one of the main incurring costs for Greek SSFs. In 2019, the fleet spent 1.8 million days at sea (DaS), utilizing 84 million liters of fuel. In total, 93% of the total DaS referred to small-scale fleets, which spent 31 million liters of fuel. It is worth noting that the average amount of energy consumption was 7.354 L per vessel [16].

Fisheries and especially SSFs are among the maritime activities that were hardest-hit by the COVID-19 pandemic, due to the unexpected decrease in seafood demand. Findings for Greece from a study conducted for the European Commission [26] show that during the lockdowns, the recession in touristic flows heavily affected seafood demand and several socio-economic impacts were produced for the Greek fleet, due to the cessation of fishing activity. Nevertheless, the sector proved to be resilient enough to this crisis.

2.2. Fisheries Co-Management and Governance as Subjects of Change and Evolution

2.2.1. Fisheries Governance Considered under the Lens of Evolutionary and Interactive Governance

Several governance-related theoretical approaches focus, in one way or another, on change and evolution. The evolutionary governance theory [27,28,29,30,31,32] gives special consideration to the impact generated by governance systems or management settings in general, or by specific actions such as policies and strategies. Some approaches focus on the procedures by which these interventions are designed, or the methods used for the revision of existing institutions. In addition, the interactive governance theory [33], applied to fisheries governance, describes how social “governing systems” (institutional bodies, markets, and regulations …) interact with natural and social “systems-to-be-governed” (local communities, fishers, and consumers…), and how their interplay defines how governance is released to serve its functions [34]. The social interactions and relations influence the justice and equity practices happening within and outside the established institutions [35].

Chuenpagdee [36] claims that more equity and justice for small-scale fisheries requires a thorough understanding of all the kinds of injustices and inequities that may affect fishers, either individually or collectively. These injustices may be either horizontal or vertical and may be sought within the fisheries value chain, but also in relation to governmental institutions and other stakeholder groups. This acknowledgment has already sparked an important debate both between scientists and practitioners on whether FLAGs ensure the inclusive and equitable sustainable development of fishing communities [37,38].

However, such an understanding should also take into account that assumptions concerning the stability of the different components of the governance system are not verified. For instance, there are approaches to policy implementation supposing that, while the policies may endure, their outcomes may evolve over time [27]. Although theories about institutional change initially suppose, for methodological purposes, that actors are stable, such a presumed stability does not always reveal the complexity, diversity, and dynamics usually experienced by governance systems [27,28].

The reality is that communities themselves are evolving, new challenges and issues are arising, policies are given different content, and both collective groups and individual players are being transformed. In a certain governance scheme, the interests, emphasis, understanding, and identities of actors may all be subject to evolution. The same goes for alliances with other actors and their positions in the constellation of actors. This is more apparent today that complex and uncertain environments are booming, where informal rules and processes can be more influential than formal ones [39,40].

Hence, an evolutionary and interactivity-related understanding of governance brings attention to the fact that there is a continuous interplay and that these elements are constantly changing [29]. This evolution is either prompt or takes a long time to manifest. Actors and networks are a part of living systems, and these are constantly evolving and adapting. Therefore, development actions must take place within “evolving systems” and procedures of constant transformation and evolution. This has several effects, including the necessity of realizing how interdependencies affect the choices of actors and how the opportunities and abilities of the latter may result from within a set of interactions or interdependencies [39].

Bugeja-Said et al. [37] argue that FLAGs are important institutions that may support the future of fishery-dependent communities and fishing livelihoods. However, they observe certain shortages, such as the fact that this pan-European network is not at all uniform, neither structurally nor operationally, and that several (in)justice issues are generated. These include a lag in the involvement of fishers in decision making and the non-inclusion of fishery demands in local development strategies, etc.

2.2.2. A Bit of FLAGs History in Greece

Fishery co-management schemes do not escape the transformation processes described in the above section. Specifically, fishery LAGs settled within the European concept of Community-Led Local Development (CLLD) were initially conceived as local partnerships between local communities and sectors such as tourism, leisure, or heritage to foster the social, economic, and environmental thriving of fishery-dependent communities. These corporations are financially supported to carry out local development programs that foster entrepreneurship [41] and conservation initiatives, e.g., the protection of the marine environment and the preservation and enrichment of the tangible and intangible cultural assets of fisheries areas, etc. These multi-stakeholder partnerships were given a mission to combine local knowledge, experiences, and capacities, following a bottom-up approach. They are meant to bring together actors from various social levels, including SSFs [39].

In 2007, the European Fisheries Fund (EFF) endorsed a revitalization similar to the 1994 PESCA initiatives [42], namely the enterprise of Fisheries Local Action Groups (FLAGs), which are classified as co-management schemes [35]. The intention of this was to encourage sustainable development and improve the quality of life in coastal areas with remarkable (though weakening) fishing activity. In this context, Greece established, from 2007 to 2013, a total of eleven (11) FLAGs mainly in coastal areas and on small and remote islands. Their development strategies focused on broadening economic activities outside the fishing sector, mobilizing private investment by fishers or non-fishers in favor of eco-tourism, accommodation facilities, and services for the benefit of small fishery communities, etc. Public investment was also directed to infrastructure related to tourism and quality of life, services in fishery areas, and to the regeneration of villages [43].

These fishery areas presented sufficient coherence in geographical, economic, and social terms. Therefore, these FLAGs brought together fishery actors and other local private and public stakeholders, targeting the development of partnerships involving the wider community and finally a local development strategy. These local development strategies are endogenous and inextricably linked to the characteristics and needs of fishing areas. In a place-based, bottom-up development approach, they are supposed to create a “sense of place” based on common cultural features, preserving the distinct identity and a sort of “marine citizenship” [44] for the local population. In other words, they enhance territorial cohesion [45,46]. Their outputs can be certainly considered as part of the “territorial capital” [46,47] of the area, including social capital [48,49]. The latter is a kind of widespread trust within the local community, motivating local actors to provide funding, time, and effort, making cooperation easier, promoting knowledge diffusion, and enhancing innovation [38].

In this context, fishers and harvesting industries are considered to be key actors of local development in these communities. In fact, through fishery LAGs, the local development policies and strategies were enriched with regional policy approaches and topics, such as technical or social innovation, networking, the quality and protection of the environment, the environmental management of resources, such as energy and waste, and energy efficiency, etc.

The next period (2014–2020) has set out to add value to the fisheries sector at the local level and boost employment and territorial cohesion [46] in fishery- and aquaculture-dependent areas through CLLD programs. The credited budget has increased (from 42 Meuro to 70 Meuro), as has the number of FLAGs (from 11 to 33 units). At this time, thirty-one FLAG strategies have been implemented by multi-funded groups managing LEADER as well as fisheries CLLD. The key objectives of the latter are economic prosperity and social inclusion, job creation, the diversification of activities within and outside fisheries, including other marine sectors, and the promotion of the sustainable development of related products. Included are activities to enhance and capitalize upon the environmental assets of fishery areas, increase the value added of fishery products and innovations along the fishery and aquaculture supply chain, and support for diversification, e.g., tourism and short-sea shipping; lifelong learning; and the promotion of social well-being and cultural heritage in these areas.

The number of fishery LAGs operating in the Mediterranean (with emphasis on Greece and Italy), shows that this initiative has stimulated a lot of interest [50] despite the limited local development benefits, including a non-capacity for reversing the decline of the fishing sector. The suffering conditions in Mediterranean coastal and island communities, driven by the low economic performance of the fishing industry, were proven to be hard to reverse. However, the spill-over effect of innovation, best practice, and expertise has generated or untapped the territorial potentials in areas confronted with comparable constraints [51].

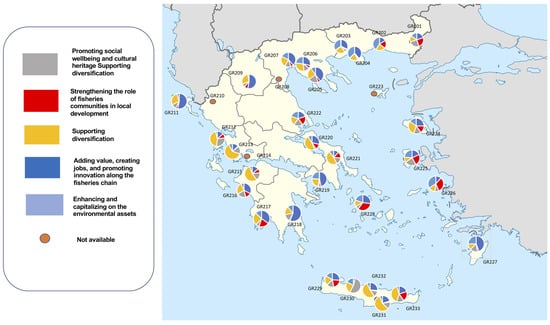

Nowadays, within a well-structured multi-level governance framework, there is still a great potential for FLAGs to open up to new activities, such as a sustainable blue economy. By incorporating several stakeholders into their corporate scheme, they can involve and mobilize the entire local community in the region to implement the Green Deal strategy in the European periphery. Sustainable blue economy targets will most probably give fishers a key role in the corporate structure of each FLAG and make their representation stronger, inclusive, and substantial. In the following Figure 2, the FLAGs participating in the current co-development process are displayed.

Figure 2.

Distribution of FLAGs participating in the research. Source: Own elaboration.

It is noteworthy that, in May 2021, a renewed approach to a sustainable blue economy in the EU was seen, in order to achieve the objectives of the European Green Deal (EGD). The aim of the EU Sustainable Blue Economy Strategy [52] is to embed it into the transition envisioned by the Green Deal and the EU Recovery Plan.

The strategy appeals for a shift from “blue growth” [53], to a “sustainable blue economy” [54] that deems the maritime industry, the environment, and the economy to be inherently linked. It aspires to replace “unchecked expansion” with “clean, climate-proof and sustainable activities that tread lightly on the marine environment”. Therefore, blue sectors (such as fisheries, aquaculture, coastal tourism, maritime transport, port activities, and ship building) are called to reduce their impact on the environment and contribute to healthy seas and the sustainable use of blue resources. More specifically, the new agenda for a sustainable blue economy aims to achieve the objectives of climate neutrality, zero pollution, the promotion of offshore renewable energies (incl. floating wind, thermal, wave, and tidal energy), the decarbonization of maritime transport, the greening of ports that may operate as energy hubs, pollution reduction, and the switch to a circular economy, together with nature and biodiversity conservation increasing fish stocks and the preservation of landscapes.

Table 1 below illustrates the alignment agenda of a sustainable blue economy with EGD. The agenda underlines “maritime spatial management” based on a consultation with all the maritime stakeholders, with the aim of stimulating cooperative exchanges in favor of the sustainable use of marine space (see Table 1 below).

Table 1.

Alignment agenda of sustainable blue economy with the EGD.

2.3. MSP as a Key Process for Fisheries Co-Management, Also Considering Climate Change Effects

When the literature on MSP refers to fisheries, it spotlights the nature of the knowledge that is being incorporated into the MSP process. Said and Trouillet [55] consider the “deep knowledge” of fishers themselves on issues such as the social and cultural aspects of their undertakings, which is more credible than the quantitative and bioeconomic data on fisheries. They argue that MSP usually relies on the latter, leading to mapping outcomes and planning choices that do not essentially exemplify the interests of the fishing industry. Hence, they argue for a more participatory approach to mapping and planning, incorporating currently ignored kinds of information, which also suggests a less formal production of knowledge. This perception is compatible with the one presented by Jentoft et al. [56]. The authors believe that resource users hold knowledge upon their perceptions that may successfully add to fisheries science and produce informed, effective, and equitable solutions to the fishery management challenge. Furthermore, in 2014, Jentoft and Knol [57] argued that fishers and their communities in the crowded North Sea consider MSP to hold both threats and opportunities, depending on the institutions involved and the role they are allowed to play in the planning process.

A more optimistic perspective is addressed by Kyvelou & Ierapetritis [19], exploring options for fishery survival, prosperity, and sustainability in the Mediterranean. Using a co-development process with maritime stakeholders, they analyze the co-existence of fisheries, tourism, and nature conservation as soft “multi-use” in the marine space. They argue that a sustainable livelihood from SSFs depends on the harmonious co-existence of fisheries with other maritime activities, which can support sustainable local development and be a pattern of a “win-win” MSP, with multiple (economic, environmental, social, cultural, and governance-related) benefits for coastal and island communities. Fisheries may co-exist with nature conservation (MPAs) [19,21], but also with climate-smart green energy applications (e.g., offshore wind farms) [58], which are both spatially bordered and operationally mature. These solutions need to be key components of climate-resilient ocean planning. In this sense, MSP may successfully assist the ‘think globally, act locally’ idea, which is an essential part of climate adaptation action.

In addition, the sharing of marine space and marine resources entails both market and public choice instruments [59]. MSP ignoring market outcomes and needs would be barely acceptable due to the opposition of several stakeholders. This seems to be the case in Greece, with strong sectoral interests expressed through national level spatial plans that hamper the implementation of an integrated MSP. However, MSP emerges as a key mechanism for delivering significant non-market societal values [59] and promoting commonization [60], such as environmental quality, the ecological integrity of marine ecosystems, and the protection of marine species that are of conservation value to society (e.g., seals, seabirds, and mammals), but also social equity and justice, safety, and security, etc. The ecosystem approach is based on “systems thinking” and provides a systemic perspective for the future of ecosystems rather than focusing on marine species. When linked with the planning of marine uses, the ecosystem approach previews an ex-ante evaluation and monitoring of the state of ecosystems. This indicates the need to forecast and manage cumulative impacts and ensure the ecosystem health [44].

Hence, MSP, while being an economic process, should both encourage and control market forces simultaneously to avoid the decommonization [60] of the ocean. A key challenge is to achieve a balance between market and non-market considerations and products, and between commonization and decommonization trends. The final assembly is dynamic, varies according to the values of each society and community, and evolves with time, the level of prosperity, the quality of the institutions, and the MSP governance. MSP should be understood as an evolutionary process that is genuinely embedded in and regularly reveals fundamental socio-cultural values, in search of an acceptable proportion between “maritime efficiency”, “maritime quality”, and “maritime identity” [61], the latter including socio-cultural values such as marine citizenship, ocean and insular literacy [44], and other societal values that, together, constitute social well-being [44].

Since fishery LAGs involve resource users, scientists, and regional/local authorities, they are ideal bottom-up constructs for supporting coherent and quality MSP, such as the one described above. Another advantage of these schemes is their longstanding experience and impact on a local level and their everyday contact with local governments.

One should not forget that local governments represent a large array of activities from province, municipal cluster, city, small town, and village governments, industry, and civil society [62]. Additionally, local governments are concerned by at least five SDG 14 targets: addressing coastal and marine pollution (14.1), adaptation to climate change impacts on the coastal zone (14.2), advancing area-based management and protection tools (14.2 and 14.5), creating sustainable blue economy (14.7), and access of SSF to marine resources and markets (14.b). Moreover, the discussion is now open, even by the EC in the context of the European Maritime Fisheries and Aquaculture Fund (hereinafter EMFAF), to involving the perspectives of local/regional authorities (NUTS 2) in MSP processes and implementation [62]. This is besides the focus of the ongoing REGINA-MSP EMFAF project (2022–2024) [63].

3. Materials and Methods

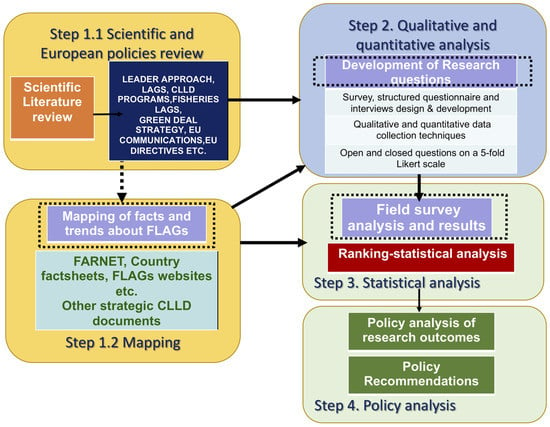

The research methodology (Figure 3) was structured around desk research and a co-development process with FLAG managers in island and coastal local fishing communities of the regions presented in Table 2, below.

Table 2.

Regional distribution of participating FLAGs in the field research, NUTS1.

The compatibility of their strategies with the Green Deal Strategy was the initial research target. However, since the CLLD programs started with great delay in 2019, the need to investigate their alignment with the current European sustainable blue economy, also issued in 2019, was a sine qua non idea. The 2021–2027 strategies were assessed, also considering regional and territorial diversity (insular and coastal allocation) and the resulting specific needs, as seen by the FLAGs themselves. Hence, the research methodology was structured around the following five steps (Figure 3):

Step 1.1. A literature review based on both scientific articles and EU technical and policy reports about the LEADER approach, and in particular, the role of LAGs and CLLD programs in the development of fishery-dependent areas. The search was extended to the Green Deal Strategy to identify its thematic priorities integrated into related community policies (such as the EU Communication of May 2021 on blue economy). Recent articles about the extent to which climate change and environmental risks are being integrated into CLLD Programs were also examined.

Step 1.2. A mapping of the facts and trends concerning the FLAGs identified in strategic documents, including material posted on the Fisheries Areas network (FARNET) website or included in the current strategy of the CLLD Programs, that are implemented in Greek fishery-dependent areas. The data and information from the Country Factsheet and the webpages of the FLAGs were valorized.

Step 2. This step included the identification of the research questions and the design of a mixed research method, combining quantitative and qualitative data collection techniques (survey and interviews, etc.) to obtain insights from the FLAGs. Structured questionnaires and interviews were used to assess their local development strategies, with reference to both the GDS and sustainable blue economy priorities. The structured questionnaire had open and closed questions, based on the five-fold Likert scale (1—strongly disagree, 2—disagree, 3—neither disagree nor agree, 4—agree, and 5—strongly agree). The co-development process took place during autumn and winter of 2021 and a great majority of the Greek FLAGs (87.9%) responded positively to the invitation.

Step 3. A statistical analysis of the outcomes and research results. The regional scale (NUTS1) and territorial diversity (insular, coastal, insular and coastal…) were taken into account in the analysis (Table 2).

Step 4. A policy analysis following the previous evaluation process. The critical factors and green and blue thematic priorities were assessed, and policy recommendations were formulated (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Outline of the research methodology.

In the framework of Step 2, two major blocks of questions appeared in the research survey:

Block 1. The participants were asked to assess the contribution of the CLLD strategy to fishery-dependent areas, in terms of

- the energy efficiency in the aquaculture industry and the range of energy sources in the sector;

- the emissions and energy efficiency of fishing vessels;

- the use of renewable energy sources (hereinafter RES);

- the impacts from the “invasion” of alien species;

- the awareness, education, and training of individual and collective actors about use of RES and the elimination of marine pollution;

- the waste management of aquaculture and fish-processing plants;

- ways of tackling overfishing; and

- fishery-driven and other marine litter (fishing nets and plastics, etc.)

Block 2. The participants were requested to prioritize the sustainable blue economy thematic directions in terms of their pragmatic value for fishery-dependent areas during the current programming period (2021–2027), such as:

- climate neutrality, zero pollution, circular economy, and waste prevention;

- the biodiversity and investment in nature-based solutions;

- coastal resilience;

- responsible food systems;

- ocean/island literacy;

- research and innovation, blue skills and jobs;

- citizen participation;

- maritime spatial planning;

- regional co-operation on a sea-basin level and support of coastal areas;

- safety at sea; and

- the international promotion of a sustainable blue economy.

4. Results

Thematic Focuses of CLLD Strategies 2014–2020

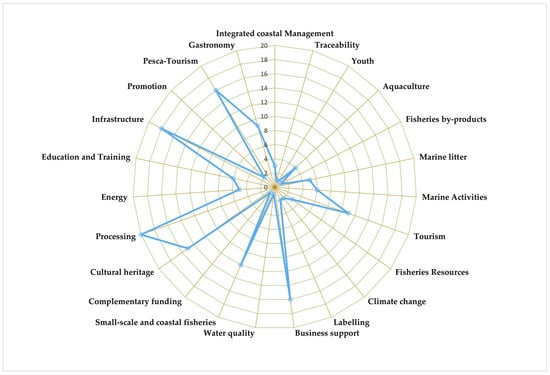

Upon examining the thematic focus of the CLLD strategies implemented during the period of 2014–2020 (extended to 2023), it was found that fish processing (endorsed by 60.6% of the FLAGs) was of high relevance. This follows the “support to business” (endorsed by 54.5% of the respondents), the need for infrastructure (54.5%), the promotion of fishing tourism (48.5%), and the promotion of cultural heritage (45.5%).

On the other side, environmental strategies harmonized with the Green Deal have attracted very little interest. Only 5 among the 33 FLAGs have opted for “Energy” and “Marine Litter” as a key topic of their strategy. Fewer were FLAGs that designed and implemented an integrated coastal zone management (hereinafter ICZM) strategy (3/33), and much fewer dealt with “Climate Change” (2/33) and “Water quality” (1/33) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Thematic priorities of FLAGs strategies in Greece 2014–2020. Source: Own elaboration of data from factsheet Greece, Fisheries Areas Network (FARNET), 2017.

However, interest in environmental issues was demonstrated by three FLAGs in northern and western Greece, that is, the Evros FLAG (with “Water quality” and “Energy” as its key choices), the Western Thessaloniki FLAG (with “Marine Litter” and ICZM as its key thematic priorities), and the South Ipeiros and Amvrakikos FLAG (opting for “ ICZM” and “Climate Change”).

As for the “Energy” priority, this has been adopted and applied in the strategies of fishery-dependent areas with significant wind potential included in the designated as “Wind Priority Areas” in the “Special Spatial Planning Framework for Renewable Energy Sources”, which is currently under revision (Rodopi and Evros FLAG in Thrace, Central and South Evia FLAGs).

As for “marine litter”, this was chosen as a strategic priority for island and coastal fishery areas that are either quite burdened environmentally or highly touristic areas such as the Cyclades islands FLAG, the Rethymno/Crete island FLAG, the Lesvos island FLAG, and the east and west Thessaloniki FLAGs. On the other hand, the FLAGs located in coastal areas that are close to or include important MPAs chose ICZM as a strategic theme (western Thessaloniki and south Ipeiros-Amvrakikos FLAGs). Finally, “Climate change” is observed in coastal and island fishery-dependent areas, such as the north and south Crete and south Ipeiros-Amvrakikos FLAGs.

Similar to this is the portrait illustrating the distribution of the budget, according to the different objectives supporting a sustainable blue economy in the applied CLLD Strategies 2014–2020 (extended to 2023). In the majority of local programs, a greater financial budget is attributed to the following objectives: “Adding value, creating jobs, and promoting innovation along the fishery chain” (more than quarter of the total budget is allocated to 42.2% of the programs); “Supporting diversification” (a quarter of the total budget is dedicated to the 30.3% of the programs), and “Enhancing and capitalizing on the environmental assets” (18.2% allocates more than a quarter and 36.6% less than 10% of their total budget) (Figure 5).

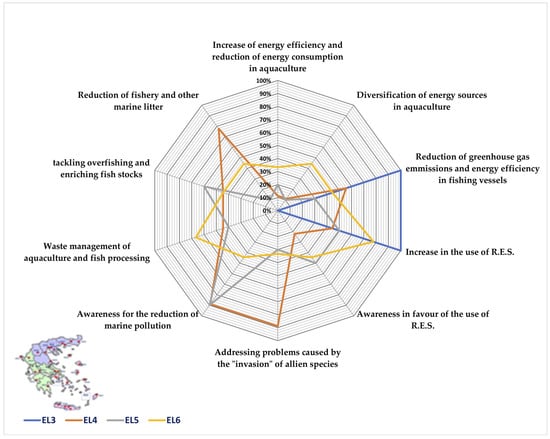

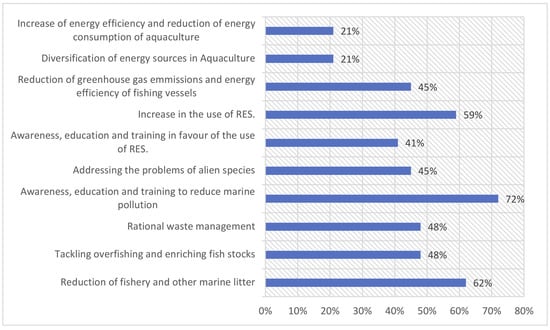

The results of the field survey revealed that 72% of the participants stated that their strategy adds to the awareness, education, and training for individual and collective actors, targeting a reduction in marine litter. Furthermore, 62% of the respondents replied that their strategies favor a reduction in marine litter (nets and plastics, etc.), whilst 59% of the participants stated that their strategy favors an increase in RES.

However, some notable findings are that 41.4% of the respondents disagreed (to strongly disagree) about the positive impact of their strategy in terms of increasing the energy efficiency in aquaculture, whilst 24.1% disagreed (to strongly disagree) about its positive influence on promoting awareness, education, and training targeting the promotion of RES. Lastly, 20.7% disagreed (to strongly disagree) about the assumption that the strategy had little to no contribution to the rational waste management in aquaculture and fish processing (Figure 5).

The energy costs and the rational waste management in fish farming units are of greater interest. The investigation revealed a remarkable emphasis on the “increase of energy efficiency of aquaculture units” in areas of the region of central Greece (EL6) (33.3% strongly agreed with this need). In the same region, a high percentage of respondents (44.4%) agreed about the diversification of energy sources feeding aquaculture farms. Effective waste management in aquaculture and fish processing plants is expected to be achieved through FLAGs planning, according to 66.7% of the respondents.

The special weight given to aquaculture comes from the fact that almost 65% of the aquaculture units that specialize in mariculture are located in coastal areas of the region of central Greece (EL6), but also from the fact that the aquaculture industry is better organized on a national level [64], also favored by legislation about zoning, which is dedicated almost exclusively to this sector.

According to the estimates of FLAGs managers, the highest contribution to the reduction in gas emissions and improvement in the energy efficiency of fishing vessels due to the implementation of the strategies is recorded in the fishing-dependent areas of the regions of Attica (EL3), the Aegean islands and Crete island (EL4), and the region of central Greece (EL6) (55.6%, 55.6%, and 44.4% percentages of consent, respectively).

Moreover, the programs implemented in the fishing areas of central Greece, northern Greece, and the Aegean islands and Crete island, with significant SSF activity, present a meaningful contribution to “tackling overfishing and enriching fish stocks” (the percentages of agreement range from 44.4% to 60%) (Figure 6).

On the contrary, hurdles caused by the “invasion of alien species” were strongly addressed in the insular space, precisely in the region of the Aegean islands and Crete island (EL4) (88.9% of the responses). This is logical, since Crete presents the highest number of observed invasive alien fish species in the country [65]. On the other side, enhancing the use of RES was endorsed by the regions of central (EL6) and northern Greece (EL5) (strong consent by 77.8% and 50.0% of the respondents, respectively).

In addition, Figure 6 shows that the awareness, education, and training for increasing the social acceptance of renewable energies were endorsed by the regions of northern and central Greece (EL5 and EL6), with 50% and 44.4% of the respondents agreeing to strongly agreeing, respectively. In these two regions (EL5 and EL6), the so-called “Wind Priority Areas” are included, as defined by the “Special Spatial Planning Framework for Renewable Energy Sources”, which is currently under revision and update, following the REPOWER EU strategy [66] and relevant Greek legislation, since they are regions with significant wind potential [67].

Figure 5.

Budget allocation to Greek FLAGs, 2014–2020. Source: Factsheet Greece, Fisheries Areas Network (FARNET), 2017.

Figure 6.

Impacts of the CLLD Strategies 2014–2020 on the fishery-dependent communities. Cumulative percentage of respondents “agreeing” to “strongly agreeing”. Source: Own elaboration, 2021–2022.

A huge interest has been raised regarding the awareness, education, and training of individual and collective actors about how to reduce marine litter in all the fishery-dependent areas of the country, since 90% and 88% of the respondents, coming from northern Greece (EL5) and the Aegean islands and Crete island (EL4), respectively, stated that they strongly agree with this strategy. In the same regions, the reduction in fishery and other marine litter (fishing nets and plastics, etc.) is highly supported by the CLLD programs, with 77.8% and 44% of the participants, respectively, providing their agreement (Figure 7).

Furthermore, when grouping the research results based on the type of the intervention area (into insular, inland, coastal, and “insular & coastal” fishing-dependent areas), the findings are summarized as follows:

- ■

- in insular areas and areas including both island and coastal fishery areas, a significant impact on the reduction in gas emissions, as well as an increase in the energy efficiency of the fishing vessels, is expected (Table 3).

- ▪

- in the coastal and inland fishing-dependent areas, as well as the mixed island and coastal spaces, the impact on increasing the use of RES is expected to be particularly important (Table 3).

- ▪

- the impact of CLLD Programs on the awareness, education, and training in favor of the use of RES is particularly important in the inland fishing-dependent areas and the coastal and insular spaces as well (Table 3).

- ▪

- as has already been noticed, the “invasion” of alien species in the Greek seas is addressed, to a greater extent, in the exclusively island fishing-dependent areas (Table 3).

- ▪

- the impact of the CLLD programs on the awareness, education, and training of both citizens and local agencies/enterprises in order to reduce marine litter seems to be vital in all four types of intervention areas (inland only, island only, coastal only, and areas combining island and coastal areas), see also Table 3.

- ▪

- the influence of the CLLD programs is vital to the rational waste management of aquaculture and fish-processing plants in coastal areas, mixed coastal areas, and insular spaces (Table 3).

- ▪

- Tackling overfishing and enriching fish stocks seems to be more important in inland and coastal fishery-dependent areas (Table 3).

- ■

- Finally, reducing fishery-driven and other marine litter is expected to benefit all types of the fishing-dependent areas (insular, coastal, inland, and insular & coastal) (Table 3).

Figure 7.

Influence of Green Deal on CLLD strategies in the fishery-dependent communities on a regional level (NUTS1). Source: Own elaboration, 2021–2022.

Table 3.

Actions prioritized to be supported by CLLD programs, per type of area.

Table 3.

Actions prioritized to be supported by CLLD programs, per type of area.

| Type of Area | Actions Where Contribution Is Expected | Percentages Appeared in the Survey (Stating that They Agree to Strongly Agree) |

|---|---|---|

Excl. Insular | -reduction in gas emissions/increase in energy efficiency of fishing vessels | 54.5% |

| -reduction in fishery and other marine litter | 100.0% | |

| -awareness/education/training of people, local agencies, and enterprises to reduce marine litter | 72.7% | |

| -invasion of alien species in the Greek seas | 72.7% | |

| -increase in the energy efficiency of the fishing vessels | 50.0% | |

Excl. Coastal | -increase in the use of renewable energy sources | 100.0% |

| -reduce fishery and other marine litter | 63.6% | |

| -tackle overfishing and increase fish stocks | 63.6% | |

| -rational waste management of aquaculture and fish-processing plants | 63.6% | |

| -awareness/education/training of people, local agencies, and entrepreneurs to reduce marine pollution | 72.7% | |

Inland | -increase the use of RES | 63.0% |

| -tackle overfishing and enrich fish stocks | 100.0% | |

| -awareness/education/training in favor of the use of RES | 100.0% | |

| -reduce fishery and other marine litter | 63.6% | |

| -awareness/education/training of people, local agencies, and enterprises to reduce marine pollution | 100.0% | |

Insular & coastal | -reduce gas emissions/increase energy efficiency of fishing vessels | 54.5% |

| -increase the use of RES | 66.0% | |

| -awareness, education, and training in favor of the use of RES. | 66.6% | |

| -rational waste management of aquaculture and fish-processing plants | 50.0% | |

| -reduce fishery and other marine litter | 50.0% | |

| -awareness/education/training of people, local agencies, and enterprises to reduce marine litter | 66.67% | |

| -increase energy efficiency of the fishing vessels | 50.0% |

Source: Research survey results and own elaboration.

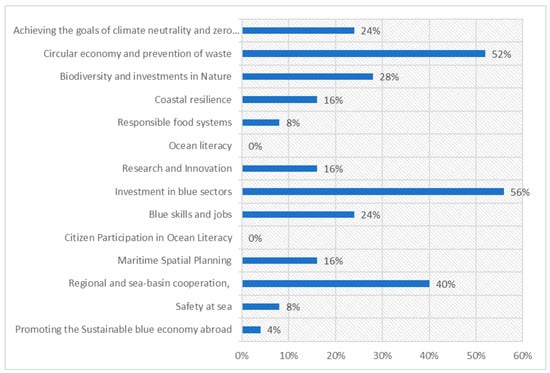

Ultimately, the participating FLAGs were asked to prioritize, considering the most realistic goals for their fishing communities, the EU thematic directions for a sustainable blue economy, in view of the new period of 2021–2027. Their answers (Figure 8, below) highlight that the Greek fishery-dependent areas have a limited capacity for adopting and implementing these directions. More specifically, only “Investment in blue sectors” and “waste elimination and circular economy” are prioritized in terms of their feasibility (chosen by 56% and 52% of the respondents, respectively). Apart from “regional cooperation”, which ranks third, the other priorities attracted very little to zero interest. It is remarkable that GDS-related directions such as “Biodiversity and investment in nature”, “Achieving the goals of climate neutrality and zero pollution”, “Marine/Maritime spatial planning”, “Coastal resilience”, and “Responsible food systems” were picked as more realistic by less than 30% of the respondents.

Figure 8.

Preparedness of fishery-dependent areas to adopt the thematic directions for the Sustainable Blue Economy in the new programming period 2021–2027, in Greece. Source: Own elaboration, 2021–2022.

In addition, through the open-ended questions and interviews with several stakeholders, fruitful insights were provided on topics such as the role of FLAGs, the importance of coastal fishing, and the obstacles they are facing, as well as the prospects for reorienting their local strategies in the context of the blue economy. The relevant statements were collected and are presented below:

“FLAGs are a cornerstone for achieving development goals in the marine environment and relevant jobs”;

“Coastal fishing is still considered to be very crucial for the local fishing communities”;

“The current legislative framework hinders the implementation of many important CLLD related measures, often rendering the strategic directions of the fisheries LAGs’ dormant and failing to address the needs of their respective areas”.

In addition, the respondents highlighted the lack of knowledge and information, pointing that:

“Fishers know little about conservation of marine ecosystems, overfishing, circular economy and fishing tourism”

“Fisheries need to de sufficiently informed about and adapted to the ecosystem-based management and take initiatives to reduce overfishing and make fishing effort productive, in the long term”.

As an example, they mentioned the initiative taken by the fishers of the island of Gyaros that consented, through a participatory procedure aided by WWF, to reduce the fishing effort for more than five years in the marine protected area (MPA) of the island, with the aim of enriching the fish stocks in the medium and long term.

Moreover, recommendations were given, such as:

“FLAGs should step up their efforts in reaching out fishers, raising their awareness through relevant educational programs and seminars”, and also

“In order for training to have the greatest participation and the best result it should not be a classical training program. It should be done at the right time and place. For example, it should take place after the sale of the day’s catch, next to the boats or in the coffee shops where fishers meet and have the opportunity to discuss and address questions”.

The support of FLAGs for “raising awareness of the local fishing communities” for relevant issues was acknowledged as the most decisive.

Justice issues were also highlighted, such as the limited representation of fishers within FLAGs as well as the limited political representation of fishers in general. It was said that:

“The role and responsibilities of fishery LAGs should be expanded to enable the implementation of a holistic development strategy on local level, improving the position and the role of coastal fishers, both within the LAGs and the fishing local communities”, and

“The exclusion of local fishers is due to the fact that they are often elderly, low-educated people, working rather alone and not easily trusting new comers”

In contrast, full acknowledgement was provided to environmental NGOs or research centers implementing on-site participatory initiatives. Alongside the CLLD programs, the above institutions are viewed as “successfully undertaking participatory initiatives to conserve and protect coastal and underwater ecosystems, jointly with local fishers and local people and stakeholders”. Precisely, special reference was made to the Hellenic Centre for Marine Research and the WWF.

Another issue that emerged through the open-ended questions and interviews concerned the funding and budget allocation to the CLLD Programs and 33 FLAGs. Specifically, doubts were addressed about whether the particularities and challenges of each fishing area were taken into account (e.g., between island and inland fishing communities).

The limited financial resources of the CLLD Programs were pointed out, arguing that “financial resources must be mobilized so that tangible results are achieved” and also that “funding is required for information and training on the use of new fishing tools such as depth gauges, new technology equipment, etc.”. Finally, the respondents pointed out the outdated fishing gears of coastal fishers, strongly suggesting that “the renewal of the fishing gears of coastal fishers should be financed during the new programming period”.

5. Discussion

In this research, the authors reveal that co-management schemes are not only about the powers of different nature, the interactions among them, and regulating measures. They are deeply shaped by the interplay of “governing systems” and “systems-to be governed” and the evolving global governance. In this context, they can create, seize, and promote opportunities. FLAGs are social constructs through which knowledge is co-created, social and cultural values may be formulated and reshaped, and a sense of community is enhanced. Co-management schemes are not stable, on the contrary they are an evolving and reflexive process.

Therefore, we strongly believe that an evolutionary understanding of fisheries governance, as described in Section 2.2 and within the multi-level and multi-actor governance framework for FLAGs, can support a new role and future for these schemes. This mission may encompass the avoidance of purely sectoral approaches, mainly through the promotion of integrated sustainable blue economy outcomes, in areas and communities dependent on fisheries. In parallel, by incorporating different stakeholders into their corporate scheme, they can involve and mobilize the entire local community in the region to implement the Green Deal in the European periphery. Fishers have a key role in the corporate structure of each FLAG, therefore their representation should be stronger, inclusive, substantial, and equitable.

However, the research findings highlighted several shortages in the evolution of the FLAGs within the current European institutional environment. For instance, the mitigation of climate and environmental impacts and the development of RES do not appear outstandingly in the FLAG strategies and their budget allocation. Environmental strategies, harmonized with the basic guidelines of the Green Deal, have attracted very little interest. Moreover, the share of FLAGs that have designed and implemented a strategy driven by “Integrated coastal management” (ICM), “climate change”, and “water quality” was limited. FLAG managers prioritized very few of the EU thematic directions for the Sustainable Blue Economy, estimating them as less realistic for their fishery-dependent areas in the current period (2021–27).

The field survey revealed that “Investment”, “Circular economy”, and “Waste prevention” were the most prioritized actions and considered as more realistic for the current period. Apparently, these strategies may be understood and supported by both the national government and private sector. All the other potential actions, Europeanized and internationalized to a higher degree, attracted very little to zero interest (such as “Maritime spatial planning” and “Biodiversity and investment in nature” linked with the EU Biodiversity Strategy and “Achieving the goals of climate neutrality and zero pollution” and “Responsible and Sustainable food systems” linked to the Farm-to-Fork (F2F) Strategy, the two latter being parts of the European Green Deal). “Coastal resilience” is also neglected, most probably because of its complexity.

This negative result reflects, inter alia, the attitude of fishers and often of fishing communities towards European policy, which is perceived as rather “hostile” for SSFs, since it has produced policies for diminishing fishing efforts and incentives are provided to push fishers to abandon their activity and destroy their vessels [21].

Seeking the wider implications of implementing the CLLD 2014–2020 Programs, the total findings of this field research revealed that the FLAG strategies have a remarkable contribution to the reduction in marine pollution and marine litter provoked by fisheries, focusing most on soft actions that raise awareness rather than supporting “hard” investment. In addition, the CLLD programs seem to support SSFs rather than aquaculture. Of course, regional and territorial differentiations were observed, depending also on the productive specialization of each region. For example, the region of central Greece (EL6), where several aquaculture farms are allocated, shows greater interest in a sustainable blue economy for aquaculture through the CLLD programs. In contrast, the region of the Aegean islands and Crete island (EL4), with the largest number of jobs in the fisheries industry, seems to contribute the most to the sustainable blue economy investments affecting SSFs (stressing the problems caused by the invasion of alien species, the reduction in fishery-driven marine litter, the energy efficiency of fishing vessels, and the cutback of marine pollution). This particular finding demonstrates that different regions and territories face different environmental challenges and pressures. Hence, a tailor-made approach should be adopted when allocating financial resources to FLAGs by the European Maritime, Fisheries and Aquaculture Fund (EMFAF), and other funds.

State policy makers, local/regional stakeholders in Greek fishery-dependent areas, and of course fisheries have a low level of awareness about the climate crisis and the means to address it in their strategies. A transition to a post-carbon society unquestionably requires further targeted assistance [68] and capacity building within FLAGs, as well as awareness and inclusive participatory procedures addressing the local communities.

It becomes crucial that a low level of education and information, together with the ageing of fishers, hampers the renewal of fishing gear that could foster a circular economy and reduce the pollution from plastics and microplastics. Fishers are lacking information and knowledge on the conservation of marine ecosystems and the strategies to reverse biodiversity loss and increase fish stocks. They are not fully aware of how Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) can contribute to climate mitigation and resilience, minimizing the environmental impacts on marine habitats and generating significant financial and social benefits in the long term. The research observed the total absence of a climate-oriented knowledge base, which acts as a structural barrier to the adoption of new marketing standards for sea food and new innovative business ideas and economic opportunities, i.e., based on the use of algae and seagrass on cell-based seafood or sustainable aquaculture.

A prerequisite for the development of a sustainable blue economy seems to be the enhancement of professional associations and the promotion and monitoring of fishers’ involvement in the decision making processes within FLAGs. The actual limited involvement of fishers in the LAGs may constrain the launch of a local blue forum for users of the sea and make the dialogue and cooperative exchange between stakeholders less inclusive, if not conflicting. The limited representation of resource users in the FLAGs will limit the possibilities for implementing the Maritime Spatial Planning Directive (MSPD), which seeks to introduce an ecosystem-based and sustainable approach to local development in marine areas. The involvement of local fishers in the planning, implementation, and monitoring of the CLLD programs will highlight the weight of the protection and preservation of underwater ecosystems in the life and profession of fishers and will probably boost succession in the industry.

Another barrier is the outdated current legislative and institutional framework that often hinders the implementation of measures regarding the marine environment and maritime jobs. For example, the absence of a regulatory institutional framework for the development and operation of offshore renewable energies (RES) demonstrates the limited national and regional interest, as well as the absence of strategic directions at the national and regional levels. In addition, the decarbonization of maritime transport or the greening of ports are not part of the key strategic directions of the bottom-up LEADER approach in FLAGs. Moreover, energy investments in aquaculture, due to a higher budget, are often financed by the sectoral Fisheries programs 2014–2020 and not by the CLLD Programs.

During the planning of the CLLD Programs and the allocation of financial resources to the FLAGs during the programming period 2021–2027, special criteria linked to regional, territorial, or other specificities of the marine and coastal environment have to be considered. Awareness activities, training programs, and seminars aimed at local fishers addressing the mentioned serious lack of knowledge and information on the importance of the marine environment (issues such as the protection of underwater ecosystems, overfishing, circular economy, and fishing tourism) must be held at a day, time, and place that facilitates the fishers’ activity schedule. Partnerships of FLAGs with environmental NGOs through learning activities and other joint initiatives would further deepen fishers’ knowledge and information, while enabling them to provide their useful “deep knowledge” of the sea to other societal groups.

In addition, special funding must be targeted to the renewal of the fishing gears of coastal fishers and informing and training new generations of fishers on the use of new fishing tools (depth gauges and new technology equipment, etc.).

6. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

This article mapped and assessed, in selected Mediterranean coastal and marine interfaces, the strategies practiced by fishery co-management schemes (fishery LAGs). It displayed how these governance systems were adaptive, either under the ongoing impact of environmental degradation, climate change, and overfishing, etc. or from the perspective of the newly risen sustainable blue economy and Green Deal strategic priorities.

The results of this assessment may question the effectiveness of the former governance system in the area, revealing its institutional weakness and the urgency for the evolution of governing relations that otherwise they may lean towards informal, action-learning structures such as the famous “communities of practice” [39,40].

The research was carried out on a sample of co-management schemes, a major part of which are based on insular and coastal fishery-dependent communities. Whilst fishery LAGs were initially framed in a place-based approach consistent with regional policy, pursuing integrated endogenous development strategies, they often either slip into serving tourism-driven (incl. restoration) sectoral interests alone or adopting an extreme territorial approach that ends up in redirecting fishing funds to other industries with a greater economic robustness and ability to profit from funding, such as tourism. FLAGs are poorly aware about ecosystem-based management and often look ineffective in competently integrating global policies (e.g., climate change adaptation, circular economy, “Farm to Fork” strategy, and other global/European policies) into local strategies.

Hence, a transition to a post-carbon blue economy on a local level requires a deep understanding of the evolutionary character both of fishery-dependent local communities, also due to their conjunction with ecosystems, and fishery co-management and governance schemes.

Here comes the role of maritime spatial planning (MSP). MSP, as an evolutionary governance process itself, may be, in the framework of a sustainable blue economy, a real driver for making these multi-stakeholder management schemes evolve. A key path for them should be to strengthen the commonization of the ocean space and blue justice and equity for fishers. MSP, especially in the eastern Mediterranean, should follow a more democratic and inclusive political approach than the actual one, reflecting the numerous voices both in MSP data acquisition and the planning and consultation process in general. Additionally, justice must be a vital quality of both the process and results of MSP, where SSFs have an important involvement. On the other hand, since fishery LAGs are coherent, multi-sectoral schemes dedicated to designing and managing integrated territorial development strategies for their regions, they may boost the cooperation that is essential for effective MSP processes, promoting harmonization between local development strategies and EU policies.

As local units that bring together stakeholders from different industries, fishery LAGs are ideally positioned to assist and boost the transition to a sustainable blue economy. They may provide support in inciting innovation through participatory territorial projects and networking actions, thus increasing the consistency of local strategies and policies. A new future for fishery LAGs, especially in marine and insular contexts with significant blue growth potential, should be sought. In this case, CLLD may play a pivotal role in developing a sustainable blue economy in these regions, combining the restoration of marine ecosystems and resources with the inclusive maintenance of local income streams.

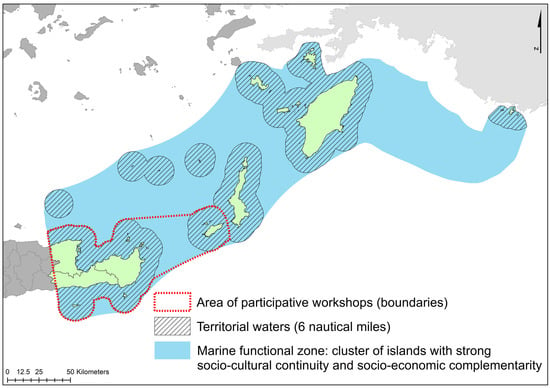

In Greece, the future of FLAGs should also go in parallel, especially in the insular space, with the conceptual construction and practice of the maritime spatial planning to be decided on and approved by the country. The Greek insular space needs an adaptive organization in “marine functional zones” (Figure 9), consisting of clusters of islands with a socio-economic complementarity and a socio-cultural continuity [69]. FLAGs may ideally assist this through the management of “integrated maritime investments” (IMI), analogous to the “territorial integrated investments” (ITI), for the implementation of which, LAGs and FLAGs were given significant roles in the previous programming period [11].

Figure 9.

Indicative “marine functional zone” incl. a cluster of islands in the Dodecanese (Aegean Sea) with socio-economic complementarity and socio-cultural continuity. Source: HER-SEA project [69].

Maritime strategies on a local level can benefit from fortified links with the EU Green Deal towards more resilient insular territories. Thanks to its solid content and funding, the EU Green Deal can assist a more targeted strategic orientation based on the valorization of marine resources. The strategy can also group and mobilize the appropriate stakeholders and combine investments from different funding sources. At the same time, local development strategies oriented towards a sustainable blue economy can efficiently contribute to delivering the EU Green Deal.

Finally, all the above are consistent with the EU cohesion policy 2021–2027, within which, integrated territorial development for non-urban areas is gaining momentum in comparison to the previous period [11]. This new policy framework is fundamental for enabling the use of the opportunities it offers to support cross-sectoral integrated territorial and local strategies. The CLLD programs remain a major territorial tool for this integration and FLAGs may be drivers of change, provided they turn to better addressing the EGD-related policies and delivering relevant integrated strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.K. and D.G.I.; methodology, S.S.K. and D.G.I.; software, D.G.I.; validation, S.S.K.; formal analysis, S.S.K. and D.G.I.; investigation, S.S.K., D.G.I. and M.C.; resources, S.S.K., D.G.I. and M.C.; data curation, D.G.I.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.K., D.G.I. and M.C.; writing—review and editing, S.S.K. and M.C.; visualization, S.S.K. and D.G.I.; supervision, S.S.K.; project administration, S.S.K. and D.G.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the fact that humans were anonymous representatives of their organizations and after being fully informed about the aim of the research, they provided their written consent in participating under the quality of FLAG managers.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the fishery LAG representatives for their collaboration and valuable insights. They are also grateful to the anonymous reviewers of the manuscript, for their precious remarks.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Barange, M.; Bahri, T.; Beveridge, M.C.M.; Cochrane, K.L.; Funge-Smith, S.; Poulain, F. (Eds.) Impacts of Climate Change on Fisheries and Aquaculture: Synthesis of Current Knowledge, Adaptation and Mitigation Options; FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper No. 627; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018; p. 628. [Google Scholar]

- Maulu, S.; Hasimuna, O.J.; Haambiya, L.H.; Monde, C.; Musuka, C.G.; Makorwa, T.H.; Munganga, B.P.; Phiri, K.J.; Nsekanabo, J.D. Climate Change Effects on Aquaculture Production: Sustainability Implications, Mitigation, and Adaptations. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 609097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daw, T.; Adger, W.N.; Brown, K.; Badjeck, M.-C. Climate change and capture fisheries: Potential impacts, adaptation and mitigation. In Climate Change Implications for Fisheries and Aquaculture: Overview of Current Scientific Knowledge; FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper. No. 530; Cochrane, K., De Young, C., Soto, D., Bahri, T., Eds.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2009; pp. 107–150. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. The Economics of adapting Fisheries to Climate Change; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, M.A.; Catalán, I.A.; Damalas, D.; Elliott, M.; Ferreira, J.G.; Hamon, K.G.; Kamermans, P.; Kay, S.; Kreiß, C.M.; Pinnegar, J.K.; et al. Climate Change and European Fisheries and Aquaculture: ‘CERES’; Project Synthesis Report: Hamburg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- F.A.O. Assessing Climate Change Vulnerability in Fisheries and Aquaculture: Available Methodologies and Their Relevance for the Sector; FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper No. 597; Brugère, C., De Young, C., Eds.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries: Community-Led Local Development and the Blue Economy, Publications Office of the European Union; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2023; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2771/392 (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- F.A.O. The State of Mediterranean and Black Sea Fisheries; General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean: Rome, Italy, 2016; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i5496e.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- European Commission. Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council, Outlining the Progress Made in Implementing Directive 2014/89/EU Establishing a Framework for Maritime Spatial Planning; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- European MSP Platform. Available online: www.msp-platform.eu (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- Pertoldi, M.; Fioretti, C.; Guzzo, F.; Testori, G.; De Bruijn, M.; Ferry, M.; Kah, S.; Servillo, L.A.; Windisch, S. Handbook of Territorial and Local Development Strategies; Pertoldi, M., Fioretti, C., Guzzo, F., Testori, G., Eds.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Fisheries and Aquaculture in Greece. OECD Review of Fisheries Country Notes|January 2021. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/agriculture/topics/fisheries-and-aquaculture/documents/report_cn_fish_grc.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- European Union. Facts and Figures on the Common Fisheries Policy, Basic Statistical Data-2022; European Union: Luxemburg, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- E.U.M.O.F.A. European Market Observatory for Fisheries and Aquaculture Products; Country Profile; E.U.M.O.F.A: Athens, Greece, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Fleet in a Glimpse, Situation as in July 2011. Available online: https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/fleet-europa/stat_glimpse_en (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- Scientific, Technical and Economic Committee for Fisheries (STECF). The 2021 Annual Economic Report on the EU Fishing Fleet (STECF 21-08); EUR 28359 EN; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021; ISBN 978-92-76-40959-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liontakis, A.; Vassilopoulou, V. Exploring fishing tourism sustainability in North-Eastern Mediterranean waters, through a stochastic modelling analysis: An opportunity for the few or a viable option for coastal communities? Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2022, 221, 106118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilopoulou, V.; Kikeri, M.; Politikos, D.; Kavadas, S. Action Plan on the Testing Area of Greece. Portodimare Project, Interreg Adrion. 2021. Available online: https://portodimare.adrioninterreg.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/DT2.8.3_Action-Plan-on-the-testing-area-of-Greece_new.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- Kyvelou, S.S.I.; Ierapetritis, D.G. Fisheries Sustainability through Soft Multi-Use Maritime Spatial Planning and Local Development Co-Management: Potentials and Challenges in Greece. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellenic Statistical Authority. Marine Fishing Survey with Motorized Vessels; Hellenic Statistical Authority: Athens, Greece, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kyvelou, S.S.I.; Ierapetritis, D.G. Fostering Spatial Efficiency in the Marine Space, in a Socially Sustainable Way: Lessons Learnt from a Soft Multi-Use Assessment in the Mediterranean. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 613721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfadyen, G.P.; Cappell, R. Characteristics of Small-Scale Coastal Fisheries in Europe. EPRS: European Parliamentary Research Service. 2011. Available online: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1338828/characteristics-of-small-scale-coastal-fisheries-in-europe/1947856/ (accessed on 19 November 2022).

- Harris, M. Greenpeace Launches “A Box of Sea” to Promote Low-Impact Fishing. 2016. Available online: http://greece.greekreporter.com/2016/06/25/greenpeace-launches-a-box-of-sea-to-promote-low-impact-fishing/ (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- Tzanatos, E.; Dimitriou, E.; Katselis, G.; Georgiadis, M.; Koutsikopoulos, C. Composition, temporal dynamics and regional characteristics of small-scale fisheries in Greece. Fish. Res. 2005, 73, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazou-Dean, A. Low Impact Fishers: The Future of Our Seas. 2014. Available online: http://www.medsos.gr/medsos/images/stories/PDF/LAZOU.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Pititto, A.; Rainone, D.; Sannino, V.; Chever, T.; Herry, L.; Parant, S.; Souidi, S.; Ballesteros, M.; Chapela, R.; Santiago, J.L. Research for PECH Committee—Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on EU fisheries and aquaculture, European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies, Brussels. 2021. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2861/292305 (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- Beunen, R.; Van Assche, K.; Gruezmacher, M. Evolutionary Perspectives on Environmental Governance: Strategy and the C Construction of Governance, Community, and Environment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partelow, S.A.; Schlüter, D.; Armitage, M.; Bavinck, K.; Carlisle, R.; Gruby, A.K.; Hornidge, M.; Le Tissier, J.; Pittman, A.M.; Song, L.P.; et al. Environmental governance theories: A review and application to coastal systems. Ecol. Soc. 2020, 25, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierson, P. Politics in Time: History, Institutions, and Social Analysis; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Van Assche, K.; Beunen, R.; Duineveld, M. Evolutionary Governance Theory: An Introduction; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Van Assche, K.; Hornidge, A.K.; Schlüter, A.; Vaidianu, N. Governance and the coastal condition: Towards new modes of observation, adaptation and integration. Mar. Policy. 2020, 112, 103413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beunen, R.; Van Assche, K. Steering in Governance: Evolutionary Perspectives. Politics Gov. 2021, 9, 365–368. Available online: https://www.cogitatiopress.com/politicsandgovernance/issue/viewIssue/261/PDF261 (accessed on 5 February 2023). [CrossRef]

- Kooiman, J.; Bavinck, M.; Jentoft, S.; Pullin, R. (Eds.) Fish for Life Interactive Governance for Fisheries; MARE Publication Series No. 3; Amsterdam University: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; Available online: https://library.oapen.org/viewer/web/viewer.html?file=/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/35130/340216.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 19 November 2022).

- Jentoft, S. Limits of governability: Institutional implications for fisheries and coastal governance. Mar. Policy 2004, 31, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linke, S.; Bruckmeier, K. Co-management in fisheries—Experiences and changing approaches in Europe. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2015, 104, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuenpagdee, R. Blue justice for small-scale fisheries: What, why and how. In Blue Justice for Small-Scale Fisheries: A Global Scan; Kerezi, V., Kinga Pietruszka, D., Chuenpagdee, R., Eds.; TBTI Global Publication Series: St. John’s, NL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bugeja-Said, A.; Svels, K.; Thuesen, A.A.; Linke, S.; Salmi, P.; Lorenzo, I.G.; de los Ángeles Piñeiro Antelo, A.; Villasante, S.; Orduña, P.P.; Pascual-Fernández, J.J.; et al. Flagging Justice Matters in EU Fisheries Local Action Groups (FLAGs). In Blue Justice; MARE Publication, Series; Jentoft, S., Chuenpagdee, R., Bugeja Said, A., Isaacs, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2021; Volume 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, P.; Linke, S.; Siegrist, N.; Svels, K. A new hope for small-scale fisheries through local action groups? Comparing Finnish and Swedish experiences. Marit. Stud. 2022, 21, 309–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Root, H.; Jones, H.; Wild, L. Managing Complexity and Uncertainty in Development Policy and Practice. (PDF) Managing Complexity and Uncertainty in Development Policy and Practice. 2015. Available online: https://www.edu-links.org/sites/default/files/media/file/5191.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Wenger, E.C.; Snyder, W.M. Communities of Practice: The Organizational Frontier. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2000, 78, 139–145. [Google Scholar]

- Ierapetritis, D.G.; Lagos, D. Building rural entrepreneurship in Greece: Lessons from lifelong learning programmes. In Entrepreneurship, Social Capital and Governance: Directions for the Sustainable Development and Competitiveness of Regions; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2012; pp. 281–301. [Google Scholar]