Abstract

Talents are seen as unique strategic resources that are essential to achieving a sustainable competitive advantage. Organizations use TM to source and maintain a high quality and quantity of talents. Despite numerous research and development of practice in this area, insufficient skills of the staff are still underlined, and an unexplored area in this regard is the support for talent development, prior to the employment of employees (i.e., at the stage of their education). There are numerous studies on TM in universities, but they cover all aspects of TM aimed at university staff. There is no research on supporting the talents of students as future employees. Meanwhile, universities “shape” the future staff and from this place employees identified as talented or with great potential are recruited. In connection with the identified gap, the question was asked whether and to what extent universities and educational entities should be involved in discovering and developing talents for the future needs of the economy. The aim of the article was to check how students perceive their future (i.e., their vision of life), how much of it is related to their future job, and how they see universities as an environment to support their talents. The study used the questionnaire-based survey-CAWI (computer assisted web interview) technique. The research was conducted in the Czech Republic, Poland, and Ukraine. The results of the research show that the support of talent development by universities is not sufficient, and the majority of students (despite the fact that the research was conducted in the last semesters of studies) do not have clearly defined goals and methods of achieving them.

1. Introduction

Talent management (TM) is a term that emerged in the late 1990s when McKinsey and Company first referred to it in their report The War for Talent [1]. In the article, the authors argued that it is worth fighting for a better talent, arguing it with the lack of people to run departments and manage critical functions, or to run a business. Since then, TM’s literature has grown enormously. The topic of TM has aroused great interest in both research and managerial practice [2,3,4]. Important contributions to the development of TM theory were made by, among others, Heinen and O’Neill (2004), Ashton and Morton (2005), Boudreau and Ramstad (2005), Tucker et al., (2005), Lewis and Heckman (2006), Collings and Mellahi (2009), McDonnell (2011), Schuler et al., (2011), Dries (2013), Al Ariss, Cascio and Paauwe (2014), Collings, Scullion and Vaiman (2015) [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. And talent management is usually defined as activities and processes that involve the systematic attraction, identification, development, engagement, retention, and deployment of those talents that are of key value to the organization in order to achieve strategic sustainable success [3,7,10,16,17,18]. The definition of TM, however, is still under discussion. So, we can rather speak of a limited consensus in this regard.

The three main motives behind the growing interest in TM are, first, the belief that talents are important in achieving sustainable competitive advantage [13,19]; second, the demographic changes that led to talent supply problems [4,16,17,18]; and third, the transformative changes in business environments that affect the quantity, quality, and characteristics of the required talent [6,12,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. Transition to a knowledge-based economy, but also the 4.0. industry revolution affected the demand for workers. There is a demand for employees who can perform more complex work and who can cope with changes in the organizational structure (for example, teamwork and networking arrangements) and the growing importance of building and maintaining relations [27,28].

While, as outlined earlier, there is currently only a limited consensus on the definition of talent and TM and how to properly research them [29], the academic literature on TM is clearly growing year by year [15,27]. The strategic importance of TM is emphasized in the literature. Wellins, Smith, and Erker (2008) have tried to prove that there is a relationship between better talent and better business outcomes [30]. This is also emphasized by Collings and Mellahi (2009), for whom organizations using strategic talent management systems achieve better results [10]. According to Schiemann (2014) people equity can influence a number of important organizational results, including higher financial results, higher quality and lower employee turnover [31]. According to Kamel (2019) there is a positive relationship between TM and employee engagement, retention, adding value, and improving the organization’s performance [32]. TM is of paramount importance for achieving the mission and goals of the organization [33].

Subsequent papers fill the theory gap identified by Lewis and Heckman (2006) and Nijs et al., (2014) [9,34] and offer organizations a vision and direction in this regard [14,35,36]. However, many questions remain, especially regarding what is happening in practice and, above all, why [37]. Talent-related issues are a major concern of many CEOs [38,39], many of whom point to a shortage of basic skills and abilities as a key threat to their organization’s growth prospects [40]. Surprisingly, there is little knowledge of how TM is created, implemented, and developed in organizations (not to mention its results and effectiveness). Thus, while it seems that TM research can be classified as phenomenon driven, as opposed to theory driven research [13], shortcomings are identified in the realm of practice.

In a recent review of the empirical literature on TM [41], the authors concluded that although the research was conducted in many different contexts (i.e., countries and organizations), the influence of contextual factors and the role of context or individual actors in conceptualizing and TM implementation has been largely neglected. Evidence shows that despite growing consensus on the ‘best fit’ approach to TM [42,43] and the consensus on the contextual meaning of TM [29,44], there has been disappointing progress in grasping contextual problems in empirical TM research.

Von Krogh, Lamastra, and Haefliger (2012) identify two interdependent indications of a research subject qualifying as a “phenomenon”. First, no theory currently available has sufficient scope to explain this phenomenon or related cause and effect relationships with this. Second, no research design or methodology beats any other in exploring various aspects of the phenomenon [45]. Given the above, it is possible to make the conclusion that TM as a field is in fact driven by phenomena, but it is still necessary to conduct research to finally constitute this phenomenon. The identified problems of enterprises in accessing talented employees and the indicated gaps in TM research justify further research, including research on the role of educational institutions and universities as institutions in shaping the talents of future staff. While reviewing the literature, the authors identified a gap in the area of research on the development of students’ talents (i.e., future employees). There is a lot of research on TM in universities, but this is true for college staff. There is a lack of research on supporting student’s talent. Meanwhile, as shown by other studies, exercises and practices [46], the motivation of third parties [47] may influence the development of talents. Developing skills and knowledge is also important for talent development [48].

The research adds value to TM theory by exploring the topics of talent development of students as future employees. This implication is unique to the development of TM theory. This study will help researchers in the field to provide a deeper understanding and develop a theoretical basis for further research.

The article consists of three parts. The theoretical part introduces the concept of talent and TM, pointing to the need to include talent development before hiring employees. The following parts of the article present the methodology and results of the research. The article ends with a discussion and the conclusions of our work.

2. Contemporary Understanding of Talent and Talent Management

According to some authors, talent is defined as the sum of a person’s abilities—his or her innate talents, skills, knowledge, experience, intelligence, judgment, attitude, character and motivation—and also includes his or her ability to learn and develop [31,49]. However, the concept of talent is not easy to identify. Changes in its definition over the years mean that we can interpret talent in different ways [50,51,52].

The assumption that some people have several kinds of talents from birth leads to the concept of so called “innate talent” which is usually referred to as musical or sports talent [53,54,55,56,57]. There are also some differences in terms of definitions in this respect. Heller, for example, thus defines scientific giftedness, which for him means nothing but the potential of scientific thinking or as a special talent for success [58]. Detterman states outright that “innate ability is what you are talking about when you are talking about talent” [54]. The basis of this approach is the belief that talent originates in genetically transmitted structures, so is at least partly innate [59,60]. However, this would mean that the early signs of talent can be used to predict future success.

Not everyone agrees with this approach. For some, basing talent on an innate ability that will make a person stand out in the future is too strong a criterion [61,62]. There has been serious opposition to the suggestion that the impact usually attributed to talent can be explained by many known performance level determinants (including hereditary) that do not fit the definition of talent [46,47,62,63,64]. Inter alia, the importance of exercise, practice [46], and motivation from third parties [64] was emphasized. According to Gagne (2000), talent exists in the few individuals who have the necessary abilities to make a difference in a given field of human performance, be it academia, arts, entertainment, sports, social action, technology, or business. However, Gagne ‘claims that talent emerges from skill as a consequence of an individual’s learning experience. In this approach, talent means the superior mastery of systematically developed abilities and knowledge in at least one area of human activity [48].

The introduction of the concept of TM also did not help to organize the approach to defining talents. Even though more than two decades have passed since the term was first used, it is still difficult to pin down the exact meaning of the term “talent management”. The main cause of these difficulties is the so-called confusion in terms of definitions and terms, and numerous assumptions by authors writing about TM [9]. Some authors still point to deficiencies in the theoretical framework of the TM concept [9,34].

The lack of consistent definitions of TM means that in practice there are at least three different ways of interpreting a TM: (1) TM is often used simply as a new term for common HR practices; (2) it can allude to succession-planning practices; and (3) it can refer more generically to the management of talented employees [9,14,65]. The terms “talent management”, “talent strategy”, “succession management”, and “human resource planning” are often used interchangeably [9]. There is therefore no uniform understanding of talent management, its goals and scope. Also, there is still controversy about whether TM is about talent management of all employees (an inclusive or strengths-based approach to TM) or is it only about talent of high-potential or high-performance employees (TM-exclusive approach) [66,67].

According to Sloan, Hazucha, and Van Katwyk (2003), managing talent in a strategic way is to choose the right person in the right place and at the right time [68]. Similarly, the concept of TM is defined by Duttagupta (2005), according to which TM is the strategic management of talent flow within an organization, and its aim is to ensure the availability of talent to match the right people to the right job at the right time based on strategic business goals [69]. Warren (2006) defines TM briefly as the combination of the identification, development, commitment, retention, and deployment of talent [70]. A slightly broader definition, but with the same message, can be found in Silzer and Dowell (2010) who define TM as an integrated set of processes, programs and cultural norms in an organization design and implemented to attract, develop, deploy, and retain talent to achieve strategic objectives and meet future business needs [50].

For Hughes and Rog (2008) TM is an espoused and enacted commitment to implementing an integrated, strategic and technology enabled approach to human resource management (HRM) [71]. However, these authors’ TM refers precisely to HRM. Similarly, for Baqutayan (2014) TM is management of the people or employees themselves by retaining the right individuals, for the right positions, at the right time. The author concluded that anyone can be talented and since all employees in an organization determine the success of the organizations, so TM applies to all employees [72]. Also, Schiemann (2014) defines TM as a unique function that integrates all activities and responsibilities related to talent lifecycle management regardless of geographic location-from attracting and acquiring talent to developing and retaining them [31]. It is also defined as a holistic and strategic approach to human resources and business planning or as a new way to increase the efficiency of an organization, with the first goal of increasing the potential of employees who are perceived to be able to make a valuable change for the organization, now or in the future and the second is to satisfy the employee and make him enjoy working in a job that corresponds to his skills and competences [72].

According to Collings and Mellahi (2009), talent refers to people with high potential, who have the ability and tendency to systematically develop the necessary skills and expertise to perform key roles in an organization [10]. These authors defined TM as activities and processes that involve the systematic identification of key positions which differentially contribute to the organization’s sustainable competitive advantage, the development of a talent pool of high potential and high performing workers to fill these roles, and such development of human resource that facilitate a filling these positions with competent workers and to ensure their continued commitment to the organization [10]. Vaiman, Haslberger, and Vance also refer TM to process that is designed to attract, develop, mobilize and retain key people [73]. Therefore at least for some authors, systems should be put in place that will enable talented people to excel and develop a successful career, as well as a positive working environment in the organization [72]. This is a reason why, in many organizations, TM means a separate path for dealing with people recognized as key, talented or with high potential. For example, over 60% of UK managers agreed that those identified as high potential or talent were expected to become senior managers/partners. At the same time, being identified as talent in British organizations means more pressure, more opportunities for growth, and better promotion [74]. However, this means that an essential step in TM is to identify and attract talented/high-potential individuals to the organization. King (2015) proposed a model according to which TM is an interactive process that includes four main factors: top management responsible for determining the talent strategy (intention, planning and definition of the concept “talent”), superiors who provide and serve the attraction, developing and implementing talents, talent managers who recognize and select talents, and finally the talented employees themselves who support learning and development [75].

Therefore, TM does not only apply to employees already employed, but the shaping of talents takes place earlier in the so-called the period preceding employment, i.e., in higher education. It is the support that students receive from the university that shapes their preparation for future work, the level of aspirations or goals they set for themselves and the ability and tendency to systematically develop the necessary skills and expertise to perform key roles in an organization.

So far, the role of universities in the “war for talents” has been analyzed, among others, by Li and Lowe, who studied the role of universities in the recruitment of ‘the brightest and the best’ internationally mobile students and their subsequent retention by the host country as high-skill workers [76]. The important role of universities in shaping talents in the context of economic changes was also pointed by Azman, Sirat, and Pang (2016) [77]. A certain connection with creation of talents among students can also be found in the work of Liu and Xu, who indicate the necessity of cooperation between schools and enterprises in cultivating talents, perfecting the course system construction, building a high-level and double-qualified teaching staff in, and building practice bases both inside and outside universities [78]. There are a lot of papers that concern TM at universities, but these are largely about the TM process of university employees. These are not research that deal with building talent among students, and therefore are not included in this article.

3. Materials and Methods

The materials, the results of working of which are covered in the article, are part of an international study on talent management. To conduct the study, empirical data were collected in the form of a questionnaire-based survey-CAWI (Computer Assisted Web Interview) technique. The survey was prepared in Czech, Polish and Ukrainian. Online surveys were available at: https://www.survio.com/survey/d/H9Y1B1R1Q0T4M7U6Y (Czech Republic) https://ankieta.interaktywnie.com/ (Poland) and https://forms.gle/8cfr1sA9mt5JMZYr5 (Ukraine) and information about the surveys was sent by mail to students.

The survey process lasted within a period from April to June 2021 on the basis of three universities in three countries: Ukraine, Poland, and Czech Republic. The questionnaire-based survey had the nature of scientific intelligence and was not aimed at substantiating the representativeness of the sample. The survey covered 513 students. The aim of the study was to check what goals students have, what is their level of aspiration, whether they are characterized by the ability and tendency to systematically develop the necessary skills and competences to perform key roles in the organization, and how they perceive the support for talent development at their universities. In order not to impose the answers, students were asked about their life vision, life mission, whether universities support them in developing their talents, and what kind of support they would like. When asking about the forms of student support, typical activities were indicated that are undertaken at universities in the surveyed countries. The respondents could additionally indicate their own option.

The sample selection was targeted. The surveyed students are students who were at the sixth or seventh level of education according to the ISCED classification (bachelor’s or equivalent level-level 6 or master’s or equivalent-level 7). All surveyed students studied management-related fields of study, i.e., management, management and production engineering, economics and business management, business management, economics and management, etc. Students who study such faculties as management and related subjects were deliberately selected for the study. It was assumed in the research that these students more often than others plan to start their own business, and therefore have more defined life goals and a life vision than others, and are more interested in managerial positions in enterprises than other students, and thus they are more interested on the development of their own talents. Students of humanities, strictly technical sciences, and other faculties were not included in the research. Basic information about the research is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic information about the research.

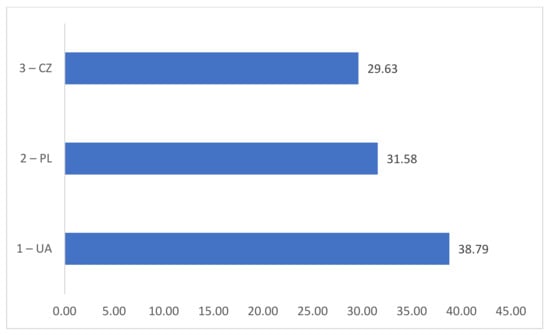

The first survey question (Q1) was related to the country of residence of the respon-dent: 1—UA (Ukraine); 2—PL (Poland); 3—CZ (Czech Republic). The representatives of Ukraine constituted the largest share among the respondents. There, the survey was conducted among students of the Lviv Polytechnic National University and covered 199 respondents. 162 respondents came from Poland. They were students of the University of Bielsko-Biala. On the part of the Czech Republic, 152 respondents took part in the survey. All students came from the Moravian Business College Olomouc (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structure of respondents by countries, %.

The second survey question (Q2) was related to the respondents’ gender: 1—female; 2—male. According to the total number of respondents, the share of women was 57.3%, including those among respondents from Ukraine—58.3%; from Poland—53.7%; from the Czech Republic—59.9%.

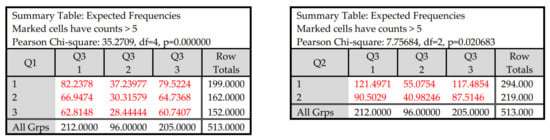

In addition to the survey method, the study used the following methods: reduction, for summarizing and systematizing the results in terms of countries and in general by the set of respondents; grouping, for determining the structure of answers to individual questions and combined questions; graphic method, for visual representation of the distribution of students’ answers by results of the groups; and relationship analysis, for justifying the influence of factors on the results. Data analysis procedures of the STATISTICA and Excel software products were used for data processing. This allowed to obtain the value of the level of significance (p) of the Pearson Chi-Square indicator in the study of the distributions of the respondents’ responses presented in the form of multicellular contingency tables. In order to identify the direction of dependence, the respondents’ answers were reduced to two alternatives and the indicators of the analysis of the four-cell conjugation table were used.

When developing the survey results, the authors also focused on the question of whether the distribution of students’ responses to individual survey questions by country and gender is statistically different.

4. Results

To answer survey question “Do you have a specific life vision?” (Q3), respondents were asked to choose one of three answer options: 1—yes; 2—no; 3—some/maybe. Despite the fact that answer “1—yes” was most often chosen by the respondents in 212 cases (41.3%), it cannot be said that the vast majority of students have a specific vision of life: in 205 cases (40.0%), there was answer “3—some/maybe” and, in 96 cases (18.7%), there was answer “2—no” (Figure 2). The choice of answer “1—yes” was most common among the representatives of Ukraine (45.7%). Specifically, Ukrainian students have a minimal difference (by 2.0 percentage points) between answers “3—some/maybe” (28.1%) and “2—no” (26.1%). Representatives of the Czech Republic most often chose answer “3—some/Maybe” (52.0%) that exceeded the frequency of choosing answer “2—no” by 42.8 percentage points and the frequency of choosing answer “1—yes” by 13.2 percentage points. Representatives of Poland answered “3—some/maybe” in 45.7% that exceeds frequency of answer “2—no” by 29.6 percentage points and frequency of answer “1—yes” by 7.4 percentage points. The difference in answers to question Q3 by countries was statistically significant. That is, the factor of the country influences the level of certainty of the vision of life.

Figure 2.

The results of analyzing the distribution of respondents’ answers about a specific vision of life.

The analysis of the distribution of answers to survey question Q3 in terms of the respondents’ gender revealed that the choice of answer “1—yes” was more common among men (47.5%), and the choice of answer “3—some/maybe” was more common among women (44.9%). Answer “2—no” was found in 54 cases among women (18.4%) and in 42 cases among men (19.2%). The difference between the answers to question Q3 in terms of gender was statistically significant. In consideration of alternative answers (1—yes; 2—no) as an effective feature, a statistically significant relationship did not manifest itself (Table 2).

Table 2.

Analysis of the distribution of answers by gender and definiteness in the vision of life (Q3).

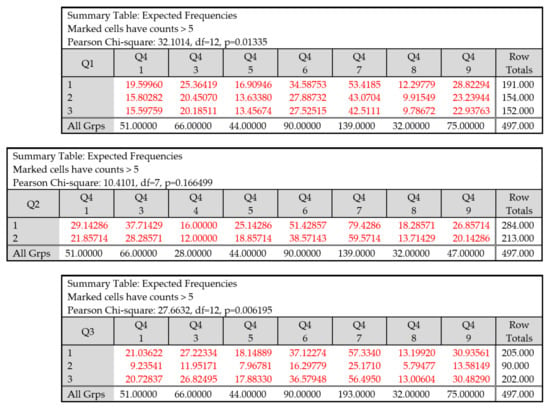

To answer survey question “What is your work mission?” (Q4), respondents were asked to choose one of nine answer options (Table 3). Most often, students see their work mission in satisfaction from job—139 people (28%) and self-realization—90 people (18.1%). Among the work mission options, the desire to make people happy/make world better—66 people (13.3%) ranked third. Relatively few students indicated such values as continuous education—51 people (10.3%) and professional development—28 people (5.6%). The smallest number of students indicated personal health—14 people (2.8%).

Table 3.

Distribution of answers to questionnaire questions “What is your work mission?” (Q4).

A statistically significant relationship was found in the analysis of answers to questions Q1–Q4 and Q3–Q4, but it did not manifest itself in questions Q2–Q4 (Figure 3). Among the representatives of Poland, compared to other countries, the highest shares of the choice of the answer about satisfaction from job—46 people (29.9%) and self-realization—44 people (28.6%) were observed. Representatives of Ukraine most often chose the same options for the vision of the work mission: satisfaction from job—46 people (25.1%); self-realization—30 people (5.7%). Among the representatives of the Czech Republic, the share of choosing the answer about satisfaction from job was also the highest among other options of the work mission—45 people (29.6%), while the second most popular answer was “3—make people happy/make the world better”—28 people (18.4%).

Figure 3.

The results of the analyzing the distribution of responses about the work mission.

Respondents who answered “1—yes” to the survey question “Do you have a specific life vision?” (Q3) most often see their work mission in satisfaction from job—48 people (23.4%) and in self-realization—22 people (22.0%). The situation is similar with respondents who chose answer “3—some/maybe” and answer “2—no” to the same question. The share of choosing in the mission a satisfaction from job was, respectively, 35.1% and 22.2% and self-realization—15.3% and 16.6%.

To answer survey question “What would you like to do in your life on a daily basis to fulfill your vision?” (Q5), respondents were asked to choose one of eight answer options (Table 4). The TOP-3 intentions of implementing one’s own vision included: 2—practice or running a business—98 people (28.3%); 1—study (education)—76 people (22%); 3—keeping in touch with family and friends—66 people (19.1%).

Table 4.

Distribution of answers to survey question “What would you like to do in your life on a daily basis to fulfill your vision?” (Q5).

A statistically significant relationship was found in the analysis of answers to questions Q3–Q5 and did not manifest itself in questions Q2–Q5 (Figure 4). Among the activities that respondents most often wanted to perform on a daily basis in order to achieve their vision, the respondents who answered “1—yes” to question Q3 of the survey, chose practice or running a business—51 people (34.7%) and study (education)—39 people (26.4%). Respondents who answered “2—no” to survey question Q3 chose the answer “other”—32 people (42.1%) and making money—17 people (22.4%) and the respondents who answered “3—some/maybe” to survey question Q3 said that they want to making money—41 people (33.6%) and practice or running business—35 people (28.7%).

Figure 4.

The results of the analyzing the distribution of respondents’ answers to survey question “What would you like to do in your life on a daily basis to fulfill your vision?”.

For the responses #3, 4, 5, and 7 of the question Q5 no statistically proved relationship were found.

It was further analyzed whether students who chose continuing education as their work mission tended to have the desire to learn in their lives on a daily basis in order to fulfill their vision (Table 5). The results of our analysis show that there is a statistically significant relationship of moderate strength between the studied features. Chances to manifest such desire are four times lower in students who do not associate the work mission with continuing education.

Table 5.

Analysis of the distribution of responses about to the choice of the mission of continuous education and the desire to learn in own life on a daily basis in order to fulfill own vision.

To answer survey question whether students are sufficiently supported by the university in developing their talents (Q6), respondents were asked to choose one of three answer options: “1—yes”; “2—no”; “3—some/maybe”. Unfortunately, students most often chose the answer “3—some/maybe” to this question—292 people (56.9%). Only 30.0% answered “1—yes”. In analyzing the distributions of answers to survey questions Q1–Q6; Q2–Q6; Q3–Q6 a statistically significant relationship did not manifest itself.

A statistically significant direct relationship was found in the analysis of answers to questions Q3–Q6 (Pearson Chi-square = 100.0331259 that is much higher of the critical value of Pearson Chi-square = 13.277 at the level of p = 0.01). The presence of life vision among students is higher among students who feel that their university support students in developing their talents (Table 6).

Table 6.

The distribution of answers by support of students in developing their talents (Q6) by universities and definiteness in the vision of life (Q3).

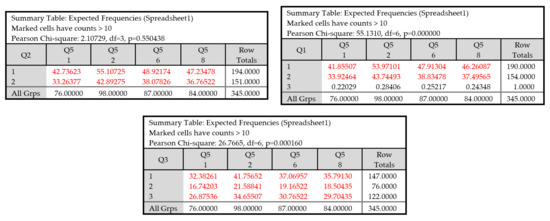

To answer survey question “What are the best ways to support the student’s talent that you would appreciate?” (Q7), respondents were asked to choose one of 10 answer options (Table 7). Respondents included the following into the TOP-3 ways to support the students’ talents: “7—special circles/clubs/cultural events/forums” (106 people or 21.9%); “8—scholarship/grants” (62 people or 12.8%) and “4—extracurricular classes/trainings” (57 people or 11.8%). Surprisingly, such responses as career office/job fairs; international exchange programs and individual study plan had very few responses (in sequence respectively: 6.8%; 4.1% and 1.7%).

Table 7.

Distribution of answers to survey question “What are the best ways to support the student’s talent that you would appreciate?” (Q7).

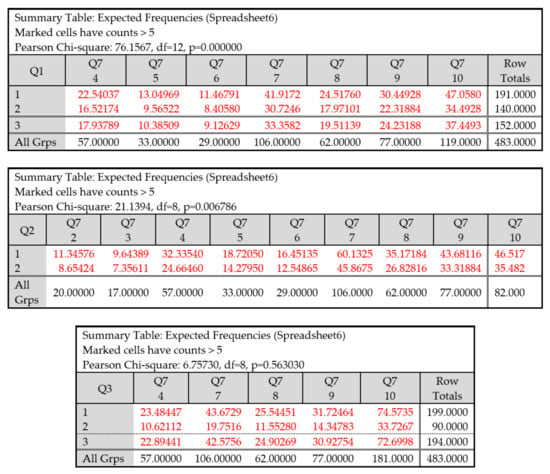

Statistically significant differences in the distributions were found when analyzing questions Q1–Q7; Q2–Q7 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The results of the analysis of the distribution of respondents’ answers to survey questions Q1–Q7; Q2–Q7; Q3–Q7.

The structure of the answers of respondents who chose answer “1—yes” to survey question “Are students supported enough in developing their talents by their university or college?” (Q6) in terms of question Q7 be in harmony with the general structure of answers (Table 8). Specifically, the students’ educational institutions which support talents somewhat more often chose answer “7—special circles/clubs/cultural events/forums” and much less often chose answer “9—don’t know”.

Table 8.

Comparison of the structure of answers to question Q7 of all respondents and the structure of answers of those who chose answer “1” to question Q6.

5. Discussion

TM is for many researchers a strategic initiative of an organization aimed at attracting, developing, and retaining talented employees in order to achieve a competitive advantage [79]. Talents are perceived as unique strategic resources, crucial for achieving a sustainable competitive advantage [13], and organizations use talent management to capture, leverage, and protect these resources [80]. Talent, however, seems to be related to employable competencies, such as general meta-competences (as self-development, creativity, analysis, problem-solving) and personality traits (including core competences as knowledge/cognitive competence, functional competence, personal or behavioral competence, values/ethical competence), which are more difficult to identify than hard technical qualifications [81,82].

When analyzing the students’ responses, it should be stated that the vast majority of them do not have a specific vision of life, what also means the lack of specific goals and ways to achieve them. At the same time, they want to be satisfied with their work and be able to fulfill themselves. It is good that some of them, to realize their vision of life, are interested in practicing or running a company, as well as studying, which is important for their future potential as employees. The willingness to do additional work, to lead, and to improve competences makes them employees who can potentially be qualified as talented or with high potential. However, these features are more common among students who positively assess the university’s support in the development of their talents.

Unfortunately, the most common answer to the question whether universities support students in developing their talents is not an affirmative answer. Most of the respondents did not answer unequivocally. On the one hand, it may mean the lack of knowledge of students about the ways of supporting their development by universities, the lack of such support or, possibly, insufficient support from universities. However, it is also a tip for the university management to pay attention to supporting the talents of students or to better promote activities undertaken in this area.

The literature emphasizes such student support systems as cooperation between enterprises or other entities and universities, the aim of which is to develop specific, necessary competences among students [65,83,84,85]. Meanwhile, according to students, the most beneficial ways of supporting talent development by universities are special circles, clubs, cultural events and forums, scholarship and grants, extracurricular classes, and trainings. Despite the possibility of indicating additional forms of supporting talents, the respondents did not indicate cooperation with enterprises.

However, open questions Q4, Q5, and Q7 generated a huge number of different answers from students. For analytical purposes authors had to group them. The large percent-age of “other” answers (14.2% and 15.3%, respectively, in questions Q5 and Q7) signals that there is no common thought about what to do in our life on daily base to fulfill our vision and what are the most useful ways of talent support by a university.

Although the competitive advantage in context of strategic management is often published topic, it is mostly focused on business oriented strategic planning (e.g., Barney et al., 1994) [86]. We focus on the point of view of students’ general life strategy and our research shows unique results suggesting division on no-oriented, job-oriented, self-oriented, and service-oriented students who want to learn and possibly practice the business management principles with the team of family and friends. Strong life priority will in future influence their intent to express themselves in running self-driven own business or to be a loyal and high-reproductive employee. Outstanding performance outcomes reflect competitive advantage created by motivated people and unique production resources (Lau, 2002).

The novelty of the paper is based especially on above-described unique approach and application of fresh primary data from three Central-Eastern European countries. It is necessary to point out that the data were collected prior to military conflict in Ukraine, which certainly influences the studied phenomena. The paper contributes and adds value to the theory of TM and competitive advantage, which makes clearer the attributes that allows an organization to outperform its competitors. A competitive advantage may include access to highly skilled labor or, e.g., natural resources, low-cost power sources, geographic location, and access to new technologies. While expanding the theory the practical application can be seen in improvement of talent development processes at universities and colleges as well as in further motivation and support for planning and running business, possibly with the circles, clubs, and forums and by scholarships and grants.

6. Conclusions

TM includes, among others, selecting the right person in the right place at the right time, ensuring the availability of talent, matching the right people for the right job at the right time based on strategic business goals, and identifying or attracting talent. Some skills are developed before starting work in which the education system plays an important role. Universities in particular, by shaping the offer of extracurricular activities and classes, can have a large impact on the preparation of graduates for future work and the development of their talents [87,88]. Meanwhile, more than half of the students have no specific vision of life. They do not have clear goals, and are not aware of the support from universities that can help them develop their talents. However, this means that universities do not help shape the vision of their students’ lives and their talents. Universities have the tools and possibilities, but students despite their relatively mature age still mostly do not know what they want to do in life.

According to the results obtained, the level of supporting students’ talents by universities is insufficient. Educational institution management should intensify efforts to diversify ways of discovering and supporting talent through greater use of individualized curricula, student associations, career offices/job fairs, scholarships/grants, incubators/startups, etc.

7. Limitations

The selection of responses for statistical analysis has been realized for the purpose of reaching the research goals, evaluability and suitability for the paper, type of variables, if they are classification/identification or factual, and if they have quantitative or qualitative value. Furthermore, only part of the research questionnaire has been evaluated, whereas other questions focused on start-ups, family business and work migration of graduate students and mutual influences of these factors will be the subject of further research.

In the theoretical part, the area of literature describing the theoretical foundations of talent development in the academic environment has been deliberately omitted. The authors focus on general definitions of talent and talent management and the role of universities in the discovery and development of talent among students, not focused on a specific sector (including higher education).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P., H.H. and O.K.; methodology, A.P.; software, O.K.; validation, A.P., H.H. and O.K.; formal analysis, A.P. and O.K.; investigation, H.H., A.P. and O.K.; resources, A.P., H.H. and O.K.; data curation, A.P., H.H. and O.K.; writing—original draft preparation, H.H., O.K. and A.P.; writing—review and editing, H.H., A.P. and O.K.; visualization, H.H., A.P. and O.K.; supervision, H.H., A.P. and O.K.; project administration, A.P.; funding acquisition, H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded under the statutory research undertaken by: the Lviv Polytechnic National University (Ukraine), the University of Bielsko-Biala (Poland) and the Moravian Business College Olomouc (Czech Republic). This paper has been prepared with the support of the project Erasmus+ BESPOKE 2021-1-HU01-KA220-HED-000032002. The APC was funded by University of Bielsko-Biala.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chambers, E.G.; Foulon, M.; Handfield-Jones, H.; Hankin, S.M.; Michaels, E.G. The War for Talent. Jan. McKinsey Q. 1998, 3, 44–57. Available online: https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/3299491/TheWarforTalent.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Cappelli, P. Talent Management for the Twenty-First Century. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 86, 74–81. Available online: https://hbr.org/2008/03/talent-management-for-the-twenty-first-century (accessed on 29 November 2021). [PubMed]

- Scullion, H.; Collings, D.G.; Caligiuri, P. Global Talent Management. J. World Bus. 2010, 45, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarique, I.; Schuler, R.S. Global talent management: Literature review, integrative framework, and suggestions for further research. J. World Bus. 2010, 45, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinen, J.S.; O’Neill, C. Managing Talent to Maximize Performance. Employ. Relat. Today 2004, 31, 67–82. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/ert.20018 (accessed on 10 December 2021). [CrossRef]

- Ashton, C.; Morton, L. Managing talent for competitive advantage: Taking a systemic approach to talent management. Strateg. HR Rev. 2005, 4, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreau, J.W.; Ramstad, P.M. Talentship, talent segmentation, and sustainability: A new HR decision science paradigm for a new strategy definition. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2005, 44, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, E.; Kao, T.; Verma, N. Next-Generation Talent Management: Insights on How Workforce Trends Are Changing the Face of Talent Management. Bus. Credit. 2005, 107, 20–27. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.505.8610&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Lewis, R.E.; Heckman, R.J. Talent management: A critical review. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2006, 16, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collings, D.G.; Mellahi, K. Strategic talent management: A review and research agenda. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2009, 19, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, A. “Still fighting the “War for Talent”? Bridging the science versus practice gap. J. Bus. Psychol. 2011, 26, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, R.S.; Jackson, S.E.; Tarique, I. Global Talent Management and Global Talent Challenges: Strategic Opportunities for IHRM. J. World Bus. 2011, 46, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dries, N. The psychology of talent management: A review and research agenda. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2013, 23, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ariss, A.; Cascio, W.F.; Paauwe, J. Talent management: Current theories and future research directions. J. World Bus. 2014, 49, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collings, D.G.; Scullion, H.; Vaiman, V. Talent management: Progress and prospects. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2015, 25, 233–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WEF. The Future of Jobs Employment, Skills and Workforce Strategy for the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Growth Strategies 2016; World Economic Forum: Cologny, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claus, L. HR disruption—Time already to reinvent talent management. Bus. Res. Q. 2019, 22, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiche, B.S.; Lee, Y.; Allen, D.G. Actors, structure, and processes: A review and conceptualization of global work integrating IB and HRM research. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 359–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huselid, M.A.; Beatty, R.W.; Becker, B.E. “A Players” or “A Positions”? The Strategic Logic of Workforce Management. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2005, 83, 110–117. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16334586/ (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Lepak, D.P.; Snell, S.A. Examining the Human Resource Architecture: The Relationships among Human Capital, Employment, and Human Resource Configurations. J. Manag. 2002, 28, 517–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthridge, M.; Komm, A.B.; Lawson, E. Making Talent a Strategic Priority. McKinsey Q. 2008, 1, 48–59. Available online: http://www.leadway.org/PDF/Making%20talent%20a%20strategic%20priority.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Beechler, S.; Woodward, I.C. The Global “War for Talent”. J. Int. Manag. 2009, 15, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, R.S.; Jackson, S.E.; Tarique, I. Framework for Global Talent Management: HR Actions for Dealing with Global Talent Challenges. In Global Talent Management; Scullion, H., Collings, D.G., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 17–36. Available online: https://www.smlr.rutgers.edu/sites/smlr/files/Documents/Faculty-Staff-Docs/the_global_talent_management_challenge_jan_15_2010_framework.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Vaiman, V.; Scullion, H.; Collings, D. Talent Management Decision Making. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 925–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, B.E.; Huselid, M.A. Strategic Human Resources Management: Where Do We Go from Here? J. Manag. 2006, 32, 898–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Jaw, B.; Tsai, C. Building dynamic strategic capabilities: A human capital perspective. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 1129–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thunnissen, M.; Boselie, P.; Fruytier, B. A review of talent management: ‘infancy or adolescence?’. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 1744–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whysall, Z.; Owtram, M.; Brittain, S. The new talent management challenges of Industry 4.0. J. Manag. Dev. 2019, 38, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Gallardo, E.; Nijs, S.; Dries, N.; Gallo, P. Towards an understanding of talent management as a phenomenon-driven field using bibliometric and content analysis. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2015, 25, 264–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellins, R.S.; Smith, A.B.; Erker, S. Nine Best for Effective Talent Management. Development Dimensions International. 2008. Available online: https://www.slideshare.net/dsides/nine-best-practices-for-effective-talent-management-50134916?msclkid=7edbbf38b28411ecb82abaea5d9d3a57 (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Schiemann, W.A. From talent management to talent optimization. J. World Bus. 2014, 49, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, N. Implementing talent management and its effect on employee engagement and organizational performance. In Proceedings of the Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition & Conference, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 11–14 November 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.P. Talent management literature review. J. Hum. Resour. 2021, 1, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijs, S.; Gallardo-Gallardo, E.; Dries, N.; Sels, L. A multidisciplinary review into the definition, operationalization, and measurement of talent. J. World Bus. 2014, 49, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelli, P.; Keller, J.R. Talent Management: Conceptual approaches and practical challenges. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 305–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascio, W.F.; Boudreau, J.W. The search for global competence: From international HR to talent management. J. World Bus. 2016, 51, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thunnissen, M.; Gallardo-Gallardo, E. Talent Management in Practice; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalla, V.; Caye, J.M.; Lovich, D.; Tollman, P. A CEO’s Guide to Talent Management Today. Boston Consulting Group. 2018. Available online: https://image-src.bcg.com/Images/BCG-A-CEOs-Guide-to-Talent-Management-Today-Apr-2018_tcm27-188660.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Groysberg, B.; Connolly, K. The 3 Things CEOs Worry about the Most. Harvard Business Review. 2015. Available online: https://hbr.org/2015/03/the-3-things-ceos-worry-about-the-most (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- PwC. PwC’s 25th Annual Global CEO Survey. 2022. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/ceo-agenda/ceosurvey/2022.html?WT.mc_id=CT3-PL300-DM1-TR2-LS4-ND22-TT20-CN_ceo-survey-semceo (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Thunnissen, M.; Gallardo-Gallardo, E. Rigor and relevance in empirical TM research: Key issues and challenges. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2019, 22, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrow, V.; Hirsh, W. Talent Management: Issues of Focus and Fit. Public Pers. Manag. 2008, 37, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, G.K.; Björkman, I.; Farndale, E.; Morris, S.S.; Paauwe, J.; Stiles, P.; Trevor, J.; Wright, P. Six Principles of Effective Global Talent Management. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2012, 53, 25–32. Available online: https://sloanreview.mit.edu/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/01b770190b.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2021). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Khilji, S.E.; Tarique, I.; Schuler, R. Incorporating the macro view in global talent management. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2015, 25, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogh, G.; Rossi, C.; Haefliger, L.S. Phenomenon-based Research in Management and Organisation Science: When is it Rigorous and Does it Matter? Long Range Plan. 2012, 45, 277–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloboda, J.A.; Davidson, J.W.; Howe, M.J.A.; Moore, D.G. The role of practice in the development of performing musicians. Br. J. Psychol. 1996, 87, 287–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, J.W.; Howe, M.J.A.; Moore, D.G.; Sloboda, J.A. The role of parental influences in the development of musical performance. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 1996, 14, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, F. Understanding the complex choreography of talent development through DMGT-based analysis. In International Handbook of Giftedness and Talent, 2nd ed.; Heller, K.A., Monks, F.J., Subotnik, R.F., Sternberg, R.J., Eds.; Elsevier Science: Oxford, UK, 2000; pp. 67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Qeed, M.A.; Khaddam, A.A.H.; Al-Azzam, Z.F.; Atieh, K.A.E.F. The effect of talent management and emotional intelligence on organizational performance: Applied study on pharmaceutical industry in Jordan. JBRMR 2018, 13, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silzer, R.; Dowell, B.E. (Eds.) Strategic Talent Management Matters. In Strategy-Driven Talent Management: A Leadership Imperative; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 3–72. Available online: http://pusin.ppm-manajemen.ac.id/pusin/assets/file_digital/FA_AFB_Sil.pdf#page=51 (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Tansley, C. What do we mean by the term “talent” in talent management? Ind. Commer. Train. 2011, 43, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamsen, B. Demystifying Talent Management: A Critical Approach to the Realities of Talent; Palgrave MacMillan: London, UK, 2016; p. 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, D.H. Creativity: Dreams, insights, and transformations. In The Nature of Creativity: Contemporary Psychological Perspectives; Sternberg, R.J., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988; pp. 271–297. [Google Scholar]

- Detterman, D.K. Giftedness and intelligence: One and the same? In Ciba Foundation Symposium 178: The Origins and Development of High Ability; Bock, G.R., Ackrille, K., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1993; pp. 22–59. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck, H.J.; Barrett, P.T. Brain research related to giftedness. In International Handbook of Research and Development of Giftedness and Talent; Heller, K.A., Monks, F.J., Passow, A.H., Eds.; Pergamon: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 115–138. [Google Scholar]

- Benbow, C.P.; Lubinski, D. Psychological profiles of the mathematically talented: Some sex differences and evidence supporting their biological basis. In Ciba Foundation Symposium 178: The Origins and Development of High Ability; Bock, G.R., Ackrille, K., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1993; pp. 44–66. [Google Scholar]

- Tranckle, P.; Cushion, C.J. Rethinking giftedness and talent. Sport Quest 2006, 58, 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, K.A. Scientific ability. In Ciba Foundation Symposium 178: The Origins and Development of High Ability; Bock, G.R., Ackrille, K., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1993; pp. 139–159. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, H. Reflections on Multiple Intelligences: Myths and Messages. Phi Delta Kappan 1995, 77, 200–209. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/i20405524 (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Gardner, H. Early giftedness and later achievement. In Ciba Foundation Symposium 178: The Origins and Development of High Ability; Bock, G.R., Ackrille, K., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1993; pp. 175–186. [Google Scholar]

- Sloboda, J.A. The Musical Mind: The Cognitive Psychology of Music; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, M.J.A.; Davidson, J.W.; Sloboda, J.A. Innate talents: Reality or myth? Behav. Brain Sci. 1998, 21, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloboda, J.A.; Howe, M.J.A. Transitions in the early musical careers of able young musicians: Choosing instruments and teachers. J. Res. Music. Educ. 1992, 40, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, K.A.; Krampe, R.T.; Heizman, S. Can we create gifted people? In Ciba Foundation Symposium 178: The Origins and Development of High Ability; Bock, G.R., Ackrille, K., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1993; pp. 222–249. [Google Scholar]

- Cadorin, E.; Germain-Alamartine, E.; Bienkowska, D.; Klofsten, M. Universities and science parks: Engagements and interactions in developing and attracting talent. In Developing Engaged and Entrepreneurial Universities, Theories, Concepts and Empirical Findings; Kliewe, T., Kesting, T., Plewa, C., Baaken, T., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 151–169. [Google Scholar]

- Iles, P.; Preece, D.; Chuai, X. Talent management as a management fashion in HRD: Towards a research agenda. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2010, 13, 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Tansley, C. Sneaking through the minefield of talent management: The notion of rhetorical obfuscation. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 3673–3691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, E.B.; Hazucha, J.F.; Van Katwyk, P.T. Strategic management of global leadership talent. Adv. Glob. Leadersh. 2003, 3, 235–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duttagupta, R. Identifying and Managing Your Assets: Talent Management; PricewaterhouseCoopers: London, UK, 2005; Available online: http://www.buildingipvalue.com/05_SF/374_378.htm (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Warren, C. Curtain call: Talent Management. People Manag. 2006, 12, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, C.H.J.; Rog, E. Talent management: A strategy for improving employee recruitment, retention and engagement within hospitality organizations. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 20, 743–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baqutayan, S.M.S. Is talent management important? An overview of talent management and the way to optimize employee performance. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 2290–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaiman, V.; Haslberger, A.; Vance, C.M. Recognizing the important role of self-initiated expatriates in effective global talent management. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2015, 25, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blass, E. Talent Management: Maximising Talent for Business Performance. 2007. Available online: https://eoe.leadershipacademy.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2019/04/1237115518_RBgM_maximising_talent_for_business_performance.pdf?msclkid=aedc6eebb28e11ecbf3bc334f9b69cc3 (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- King, K.A. The talent deal and journey Understanding how employees respond to talent identification over time. Empl. Relat. 2015, 38, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.J.; Lowe, J. Mobile student to mobile worker: The role of universities in the ‘war for talent’. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2016, 37, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azman, N.; Sirat, M.; Pang, V. Managing and mobilising talent in Malaysia: Issues, challenges and policy implications for Malaysian universities. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2016, 38, 316–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, Z. Educational Reform and Exploration on Cultivating Innovation and Entrepreneurship Talents in Universities. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Politics, Economics and Management, Zhengzhou, China, 27–28 April 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, A.; Rajithakumar, S.; Menon, M. Talent management and employee retention: An integrative research framework. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2019, 18, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparrow, P.R.; Makram, H. What is the value of talent management? Building value-driven processes within a talent management architecture. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2015, 25, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, S.; Ellström, P. Employability and talent management: Challenges for HRD practices. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2012, 36, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheetham, G.; Chivers, G. Towards a holistic model of professional competence. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 1996, 20, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T. Interaction among high-tech talent and its impact on innovation performance: A comparison of Taiwanese science parks at different stages of development. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2008, 16, 163–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berbegal-Mirabent, J.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D.; García, J. Can a magic recipe foster university spin-off creation? J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 2272–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löfsten, H.; Klofsten, M.; Cadorin, E. Science Parks and talent attraction management: University students as a strategic resource for innovation and entrepreneurship. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 2465–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B.; Zajac, E.J. Competitive Organizational Behavior: Toward an Organizationally-Based Theory of Competitive Advantage. Strat. Manag. J. 1994, 15, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm-Nielsen, L.B.; Thorn, K.; Olesen, J.D.; Huey, T. Talent development as a university mission: The quadruple helix. High. Educ. Manag. Policy 2013, 24, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolnhofer-Derecskei, A.; Pawliczek, A. Talent Management as an Effect of Globalization in Case of Visegrad 4 Countries. In Proceedings of the 18th International Scientific Conference Globalization and Its Socio-Economic Consequences University of Zilina, Faculty of Operation and Economics of Transport and Communications, Department of Economics, Rajecke Teplice, Slovakia, 10–11 October 2018; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339461229_TALENT_MANAGEMENT_AS_AN_EFFECT_OF_GLOBALIZATION_IN_CASE_OF_VISEGRAD_4_COUNTRIES (accessed on 15 March 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).