On the Micro-Foundations of Creative Economy: Life Satisfaction and Social Identity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Toward a Creative Economy for Sustainable Development

3. Life Satisfaction as a Micro-Foundation of the Creative Economy

4. Life Satisfaction, Social Identity, and the Creative Economy

5. The Construction of Social Identity and the Empirical Analysis

5.1. The Methodology Employed

5.2. The Empirical Results

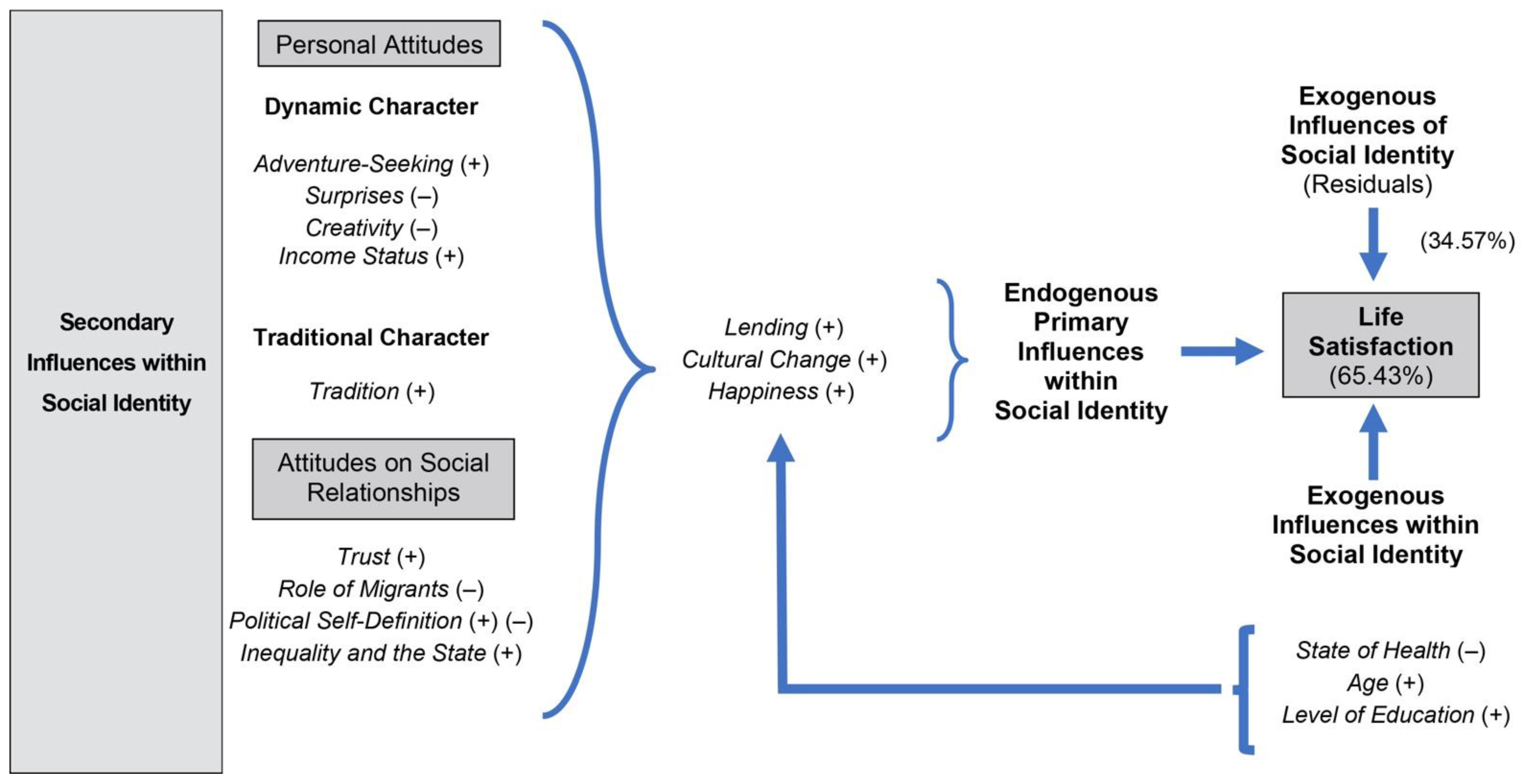

5.3. Exogenous and Endogenous Influences within Social Identity

5.4. Further Analysis of the Endogenous Influences

6. Conclusions: Altered Priorities Are Translated to Altered Identities

7. Policy Implications: Toward Life Satisfaction and Further Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mi, Z.; Coffman, D.-M. The sharing economy promotes sustainable societies. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sousa, L.; Lyubomirsky, S. Life Satisfaction. In Encyclopedia of Women and Gender: Sex Similarities and Differences and the Impact of Society on Gender; Worell, J., Ed.; Academic Press Inc.: San Diego, CA, USA, 2001; Volume 2, pp. 667–676. ISBN 978-0-12-227245-5. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H. Differentiation between Social Groups: Studies in the Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; European Association of Experimental Social Psychology by Academic Press: London, UK, 1978; ISBN 978-0-12-682550-3. [Google Scholar]

- Schimmack, U.; Schupp, J.; Wagner, G. The Influence of Environment and Personality on the Affective and Cognitive Component of Subjective Well-Being. Soc. Indic. Res. Int. Interdiscip. J. Qual.—Life Meas. 2008, 89, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrington-Leigh, C.P. Life Satisfaction and Sustainability: A Policy Framework. SN Soc. Sci. 2021, 1, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, S. Sustainable Development. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 6501–6504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Markusen, A.; Wassall, G.H.; DeNatale, D.; Cohen, R. Defining the Creative Economy: Industry and Occupational Approaches. Econ. Dev. Q 2008, 22, 24–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McKenzie, S.; Abdulkadri, A. Mechanisms to Accelerate the Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals in the Caribbean; United Nations Publication: Santiago, Chile, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kacerauskas, T.; Streimikiene, D.; Bartkute, R. Environmental Sustainability of Creative Economy: Evidence from a Lithuanian Case Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štreimikienė, D.; Kacerauskas, T. The creative economy and sustainable development: The Baltic States. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtado, G.; Alves, S. Cidades criativas em Portugal e o papel da arquitetura: Mais uma estratégia a concertar. Rev. Crit. Cienc. Sociais 2012, 99, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodrigues, M.; Franco, M. Measuring the urban sustainable development in cities through a Composite Index: The case of Portugal. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 20, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerisola, S.; Panzera, E. Cultural and Creative Cities and Regional Economic Efficiency: Context Conditions as Catalyzers of Cultural Vibrancy and Creative Economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. The Future of the Creative Economy. 2021. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/uk/Documents/technology-media-telecommunications/deloitte-uk-future-creative-economy-report-final.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Meyer, D. Creativity, Human Capital and Economic Growth. Társadalom És Gazdaság Közép-És Kelet-Európában/Soc. Econ. Cent. East. Eur. 1999, 21, 117–129. [Google Scholar]

- Rybarova, D. Creative Industry as a Key Creative Component of the Slovak Economy. SHS Web Conf. 2020, 74, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granstrand, O. Intellectual Capitalism—An Overview. Nord. J. Political Econ. 1999, 25, 115–127. [Google Scholar]

- Sava, D. The Concept of Creative Economy. In Emerging Markets Economics and Business, Contributions of Young Researchers, Proceedings of the 5th Conference of Doctoral Students in Economic Sciences, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 25 February 2022; Oradea University Press: Oradea, Romania, 2014; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, R. The Silent Revolution in Europe: Intergenerational Change in Post-Industrial Societies. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1971, 65, 991–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Inglehart, R.; Baker, W.E. Modernization, Cultural Change, and the Persistence of Traditional Values. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2000, 65, 19–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Inglehart, R.; Abramson, P.R. Measuring Postmaterialism. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1999, 93, 665–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, R.; Stuetzer, M.; Obschonka, M.; Thompson, P. Historical Industrialisation, Path Dependence and Contemporary Culture: The Lasting Imprint of Economic Heritage on Local Communities. J. Econ. Geogr. 2021, 21, 841–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throsby, D. Development Strategies for Pacific Island Economies: Is There a Role for the Cultural Industries? Asia Pac. Policy Stud. 2015, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafirovski, M. The Rational Choice Generalization of Neoclassical Economics Reconsidered: Any Theoretical Legitimation for Economic Imperialism? Sociol. Theory 2000, 18, 448–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareto, V. Manuel d’Economie Politique; Marcel Girard: Paris, France, 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Veblen, T. Why Is Economics Not an Evolutionary Science? Q. J. Econ. 1898, 12, 373–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Galbraith, J.K. The Affluent Society; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: Boston, NY, USA, 1958; ISBN 978-0-395-92500-3. [Google Scholar]

- Myrdal, G. The Political Element in the Development of Economic Theory; Routledge & Kegan Paul: London, UK, 1953; ISBN 978-0-88738-827-9. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, D.L.; Randers, J.; Behrens, W.W., III. The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind; Universe Books: New York, NY, USA, 1972; ISBN 0-87663-165-0. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A.H. A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnson, R.D. The Moral and Social Problem of Scarcity. In Rediscovering Social Economics: Beyond the Neoclassical Paradigm; Johnson, R.D., Ed.; Perspectives from Social Economics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterlin, R.A. Will Raising the Incomes of All Increase the Happiness of All? J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1995, 27, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterlin, R.A. Feeding the Illusion of Growth and Happiness: A Reply to Hagerty and Veenhoven. Soc. Indic. Res. 2005, 74, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-19-829758-1. [Google Scholar]

- Gadrey, J.; Jany-Catrice, F. The New Indicators of Well-Being and Development; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-230-00500-6. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J.; Fitoussi, J.-P.; Durand, M. Beyond GDP: Measuring What Counts for Economic and Social Performance; Sciences Po, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. The Creative Attitude; Psychosynthesis Research Foundation, The Structurist #3; University of Saskatchewan: Saskatoon, SK, Canada, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Gilovich, T.; Kumar, A.; Jampol, L. A Wonderful Life: Experiential Consumption and the Pursuit of Happiness. J. Consum. Psychol. 2015, 25, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krys, K.; Park, J.; Kocimska-Zych, A.; Kosiarczyk, A.; Selim, H.A.; Wojtczuk-Turek, A.; Haas, B.W.; Uchida, Y.; Torres, C.; Capaldi, C.A.; et al. Personal Life Satisfaction as a Measure of Societal Happiness Is an Individualistic Presumption: Evidence from Fifty Countries. J. Happiness Stud. 2020, 22, 2197–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H. Individuals and Groups in Social Psychology. Br. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1979, 18, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H. Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1982, 33, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stryker, S.; Burke, P.J. The Past, Present, and Future of an Identity Theory. Soc. Psychol. Q 2000, 63, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turner, J.C.; Hogg, M.A.; Oakes, P.J.; Reicher, S.D.; Wetherell, M.S. Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory; Basil Blackwell: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1987; ISBN 978-0-631-14806-7. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman, D. Identity-Based Motivation: Implications for Action-Readiness, Procedural-Readiness, and Consumer Behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2009, 19, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind: Intercultural Cooperation and Its Importance for Survival; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-07-166418-9. [Google Scholar]

- Fromm, E. Man for Himself: An Inquiry into the Psychology of Ethics; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.A. Uncertainty–Identity Theory. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Zanna, M.P., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007; Volume 39, pp. 69–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerlof, G.; Kranton, R. Economics and Identity. Q. J. Econ. 2000, 115, 715–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T. Social identity dimensions and consumer behavior in social media. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2017, 22, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrier, J. Reconciling Commodities and Personal Relations in Industrial Society. Theory Soc. 1990, 19, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, M.; Shiu, E.; Hassan, L.M. The influence of social identity on value perceptions and intention. J. Consum. Behav. 2017, 16, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Consumer-Company Identification: A Framework for Understanding Consumers’ Relationships with Companies. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, M.R. Organizational Identification: A Conceptual and Operational Review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2006, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, C.; Wieseke, J.; Hoyer, W.D. Social Identity and the Service-Profit Chain. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassonko, B. The Reciprocal Connection between Identity and Consumption: A Literature Review. Jr. Manag. Sci. 2020, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R. The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles among Western Publics; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, P.; Inglehart, R. Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-108-44442-2. [Google Scholar]

- Afolabi, O.; Balogun, A. Impacts of Psychological Security, Emotional Intelligence and Self-Efficacy on Undergraduates’ Life Satisfaction. Psychol. Thought 2017, 10, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Uhlaner, L.M.; Thurik, R.; Hutjes, J. Post-Materialism as a Cultural Factor Influencing Entrepreneurial Activity across Nations; Erasmus University Rotterdam: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pillath, C.H. Identity Economics and the Creative Economy, Old and New. Cult. Sci. J. 2008, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fujiwara, D.; Dolan, P.; Lawton, R. Happier and More Satisfied? Creative Occupations and Subjective Well-Being in the United Kingdom. Psychosociological Issues Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemati, S.; Maralani, F.M. The Relationship between Life Satisfaction and Happiness: The Mediating Role of Resiliency. Int. J. Psychol. Stud. 2016, 8, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Headey, B.; Muffels, R. Towards a Theory of Life Satisfaction: Accounting for Stability, Change and Volatility in 25-Year Life Trajectories in Germany; SOEP Papers on Multidisciplinary Panel Data Research; DIW Berlin, The German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP): Berlin, Germany, 2016; p. 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greenaway, K.H.; Cruwys, T.; Haslam, S.A.; Jetten, J. Social Identities Promote Well-Being Because They Satisfy Global Psychological Needs. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 46, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4391-9075-3. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Chen, S.; Chen, L.; Li, L. Social Class Identity, Public Service Satisfaction, and Happiness of Residents: The Mediating Role of Social Trust. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 659657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ifeagwazi, C.M.; Chukwuorji, J.C.; Zacchaeus, E.A. Alienation and Psychological Wellbeing: Moderation by Resilience. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 120, 525–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowkar, B. The Mediating Role of Resilience in the Relationship between General and Emotional Intelligence and Life Satisfaction. Contemp. Psychol. Biannu. J. Iran. Psychol. Assoc. 2007, 2, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Scheepers, D.; Ellemers, N. Social Identity Theory. In Social Psychology in Action: Evidence-Based Interventions from Theory to Practice; Sassenberg, K., Vliek, M.L.W., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 129–143. ISBN 978-3-030-13787-8. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, A.; Cummins, P.; Breslin, G.; Stringer, M. Perceptions of Coach Social Identity and Team Confidence, Motivation and Self-Esteem. Psychology 2014, 5, 1175–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinnirella, M.G. Social Identity Perspectives on European Integration: A Comparative Study of National and European Identity Construction in Britain and Italy; London School of Economics and Political Science: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ellemers, N.; Kortekaas, P.; Ouwerkerk, J.W. Self-Categorization, Commitment to the Group and Social Self-Esteem as Related but Distinct Aspects of Social Identity. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 29, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, K. LIII. On Lines and Planes of Closest Fit to Systems of Points in Space. Lond. Edinb. Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 1901, 2, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hotelling, H. Analysis of a Complex of Statistical Variables into Principal Components. J. Educ. Psychol. 1933, 24, 417–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I.T.; Cadima, J. Principal Component Analysis: A Review and Recent Developments. Philos. Trans. R Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2016, 374, 20150202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellow, J.T. Using Principal Components Analysis in Program Evaluation: Some Practical Considerations. J. MultiDisciplinary Eval. 2006, 3, 89–107. [Google Scholar]

- Kanzola, A.-M.; Petrakis, P.E. Τhe Sustainability of Creativity. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassel, C. Principal Component Analysis of Social Capital Indicators—Office for National Statistics; Office of National Statistcis: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Veenhoven, R. Is Happiness a Trait. In Citation Classics from Social Indicators Research: The Most Cited Articles Edited and Introduced by Alex C. Michalos; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Social Indicators Research Series; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 477–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky The Benefits of Frequent Positive Affect: Does Happiness Lead to Success? APA PsycArticles 2005, 131, 803–855. [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coffey, J.K.; Warren, M.T.; Gottfried, A.W. Does Infant Happiness Forecast Adult Life Satisfaction? Examining Subjective Well-Being in the First Quarter Century of Life. J. Happiness Stud. 2015, 16, 1401–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakkeli, N.Z. Health, Work, and Contributing Factors on Life Satisfaction: A Study in Norway before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. SSM—Population Health 2021, 14, 100804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmore, E.; Luikart, C. Health and Social Factors Related to Life Satisfaction. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1972, 13, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haybron, D.M. The Pursuit of Unhappiness: The Elusive Psychology of Well-Being; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-19-959246-3. [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo, P.; Jones, W.; Wang, L.; Shen, X.; Goldner, E.M. The Fundamental Association between Mental Health and Life Satisfaction: Results from Successive Waves of a Canadian National Survey. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Puvill, T.; Lindenberg, J.; de Craen, A.J.M.; Slaets, J.P.J.; Westendorp, R.G.J. Impact of Physical and Mental Health on Life Satisfaction in Old Age: A Population Based Observational Study. BMC Geriatr. 2016, 16, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schnohr, P.; Kristensen, T.S.; Prescott, E.; Scharling, H. Stress and Life Dissatisfaction Are Inversely Associated with Jogging and Other Types of Physical Activity in Leisure Time—The Copenhagen City Heart Study. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2005, 15, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukat, J.; Margraf, J.; Lutz, R.; van der Veld, W.M.; Becker, E.S. Psychometric Properties of the Positive Mental Health Scale (PMH-Scale). BMC Psychol. 2016, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Panchal, N.; Kamal, R. The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use; KFF: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman, D.; Coon, H.M.; Kemmelmeier, M. Rethinking Individualism and Collectivism: Evaluation of Theoretical Assumptions and Meta-Analyses. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 128, 3–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steward, J.H. Theory of Culture Change; the Methodology of Multilinear Evolution; University of Illinois Press: Urbana, IL, USA, 1955; ISBN 978-0-252-00295-3. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis, H. The Ibadan Conference and Beyond. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2009, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrakis, P.E. The New Political Economy of Greece up to 2030, 1st ed.; 2020 edition; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-47074-6. [Google Scholar]

- Garicano, L. Capitalism after Covid. Conversations with 21 Economists; Garicano, L., Ed.; Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) Press: London, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-1-912179-45-9. [Google Scholar]

- Becchetti, L.; Conzo, P. Credit Access and Life Satisfaction: Evaluating the Nonmonetary Effects of Micro Finance. Appl. Econ. 2013, 45, 1201–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, H.V.; Ho, H. Analysis of Factors Influencing Credit Access of Vietnamese Informal Labors in the Time of COVID-19 Pandemic. Economies 2022, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, B.S.; Stutzer, A. Happiness and Economics; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L.L.; Isaacowitz, D.M.; Charles, S.T. Taking Time Seriously: A Theory of Socioemotional Selectivity. Am. Psychol. 1999, 54, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carstensen, L.L.; Fung, H.H.; Charles, S.T. Socioemotional Selectivity Theory and the Regulation of Emotion in the Second Half of Life. Motiv. Emot. 2003, 27, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, H.Y.; Chan, A.W.H. The Effect of Education on Life Satisfaction across Countries. Alta. J. Educ. Res. 2009, 55, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila, L.E. The Outcomes of Investment in Education and People’s Well-Being. Eur. J. Educ. 2005, 40, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Mar Salinas-Jiménez, M.; Artés, J.; Salinas-Jiménez, J. Education as a Positional Good: A Life Satisfaction Approach. Soc. Indic. Res. 2011, 103, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, R. Education and Economic Growth. Ann. Econ. Financ. 2013, 14, 301–328. [Google Scholar]

- Hanushek, E.A.; Woessmann, L. Education and Economic Growth. In International Encyclopedia of Education; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 2, pp. 245–252. [Google Scholar]

- Delis, M.D.; Fringuellotti, F.; Ongena, S. Credit, Income, and Inequality. In Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Staff Report, No. 929s; Federal Reserve Bank of New York: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiamah, T.A.; Steel, W.F.; Ackah, C. Determinants of Credit Demand and Credit Constraints among Households in Ghana. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertler, M.; Karadi, P. A Model of Unconventional Monetary Policy. J. Monet. Econ. 2011, 58, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucato, M. Mission Economy: A Moonshot Guide to Changing Capitalism; Harper Business: New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-0-06-304623-8. [Google Scholar]

- Petrakis, P.E.; Kanzola, A.M. Alternative Futures of Capitalist Economy. In Proceedings of the After Covid? Critical Conjunctures and Contingent Pathways of Contemporary Capitalism, Online, 2–5 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Latif, E. Does Income Inequality Impact Individual Happiness? Evidence from Canada. Int. J. Appl. Econ. 2018, 15, 42–79. [Google Scholar]

- Oishi, S.; Kesebir, S.; Diener, E. Income Inequality and Happiness. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 22, 1095–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagi, T. Moral, Trust and Happiness—Why Does Trust Improves Happiness? J. Organ. Psychol. 2017, 17, 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Schlenker, B.R.; Chambers, J.R.; Le, B.M. Conservatives Are Happier than Liberals, but Why? Political Ideology, Personality, and Life Satisfaction. J. Res. Personal. 2012, 46, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogilner, C.; Aaker, J.; Kamvar, S.D. How Happiness Affects Choice. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.-Y.; Chuah, C.-Q.; Lee, S.-T.; Tan, C.-S. Being Creative Makes You Happier: The Positive Effect of Creativity on Subjective Well-Being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, M.; Gibb, J.K. Culture, Behavior and Health. Evol. Med. Public Health 2020, 2020, 12–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hruschka, D.J.; Hadley, C. A Glossary of Culture in Epidemiology. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2008, 62, 947–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, F. Identity: The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment; Farrar Straus & Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-0-374-12929-3. [Google Scholar]

- Lomborg, B. Welfare in the 21st century: Increasing development, reducing inequality, the impact of climate change, and the cost of climate policies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 156, 119981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhearson, T.; Raymond, C.M.; Gulsrud, N.; Albert, C.; Coles, N.; Fagerholm, N.; Nagatsu, M.; Olafsson, A.S.; Soininen, N.; Vierikko, K. Radical changes are needed for transformations to a good Anthropocene. NPJ Urban Sustain. 2021, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Atwi, A.A.; Amankwah-Amoah, J.; Khan, Z. Micro-foundations of organizational design and sustainability: The mediating role of learning ambidexterity. Int. Bus. Rev. 2021, 30, 101656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parwita, G.B.; Arsawan, I.W.E.; Koval, V.; Hrinchenko, R.; Bogdanova, N.; Tamosiuniene, R. Organizational Innovation Capability: Integrating Human Resource Management Practice, Knowledge Management, and Individual Creativity. Intelekttine Econ. Intelect. Econ. 2021, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, M.; Koval, V.; Tepavicharova, M.; Zerkal, A.; Radchenko, A.; Bondarchuk, N. The Interaction between Human Resources Motivation and the Commitment to the organization. J. Secur. Sustain. Issues 2020, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hett, F.; Kröll, M.; Mechtel, M. The Structure and Behavioral Effects of Revealed Social Identity Preferences; IAAEU Discussion Paper Series in Economics; University of Trier, Institute for Labour Law and Industrial Relations in the European Union (IAAEU): Trier, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, M.; Bamberg, S.; Rees, J.; Rollin, P. Social Identity as a Key Concept for Connecting Transformative Societal Change with Individual Environmental Activism. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 72, 101525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, P.; Ryan, R.; Duineveld, J.; Bradshaw, E. Validation of the Social Identity Group Need Satisfaction and Frustration Scale. PsyArXiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornung, J.; Bandelow, N.C.; Vogeler, C.S. Social Identities in the Policy Process. Policy Sci. 2019, 52, 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kanzola, A.-M.; Papaioannou, K.; Petrakis, P.E. Social Identity, Rationality, Creativity. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2021, 28, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. The Theory of Economic Development; Harvard Economic Studies 46; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1934; ISBN 9780674879904. [Google Scholar]

- Alchian, A.A. Uncertainty, Evolution, and Economic Theory. J. Political Econ. 1950, 58, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nelson, R.R.; Winter, S.G. An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1985; ISBN 978-0-674-27228-6. [Google Scholar]

- Stoelhorst, J.W. Generalized Darwinism from the Bottom Up: An Evolutionary View of Socio-Economic Behavior and Organization. In Advances in Evolutionary Institutional Economics: Evolutionary Modules, Non-Knowledge, and Strategy, Wolfram Elsner and Hardy Hanappi, Eds; SSRN: Rochester, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlesworth, B.; Lande, R.; Slatkin, M. A Neo-Darwinian Commentary on Macroevolution. Evolution 1982, 36, 474–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Grouping of Variables | Variables |

|---|---|

| Degree of Life Satisfaction and Individual State | Happiness (+) State of Health (–) |

| Identity Traits | |

| Life Attitudes | Cultural Change (+) Lending (+) |

| Demographics | Age (+) Level of Education (+) |

| Dependent Variables | R2 | Grouping of Variables | Variables |

|---|---|---|---|

| Happiness | 15.43% | Exogenous Influences within Social Identity | Sate of Health (–) Age (–) |

| Positive Secondary Influences within Social Identity | Inequality and the State (+) Trust (+) Adventure-Seeking (+) Political Self-Definition (+) | ||

| Negative Secondary Influences within Social Identity | Surprises (–) Creativity (–) | ||

| Cultural Change | 36.28% | Exogenous Influences within Social Identity | State of Health (–) |

| Positive Secondary Influences within Social Identity | Tradition (+) | ||

| Negative secondary Influences within Social Identity | Role of Migrants (–) Political Self-Definition (–) | ||

| Lending | 3.08% | Exogenous Influences within Social Identity | Income Status (+) Age (–) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Petrakis, P.E.; Kanzola, A.-M. On the Micro-Foundations of Creative Economy: Life Satisfaction and Social Identity. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4878. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094878

Petrakis PE, Kanzola A-M. On the Micro-Foundations of Creative Economy: Life Satisfaction and Social Identity. Sustainability. 2022; 14(9):4878. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094878

Chicago/Turabian StylePetrakis, Panagiotis E., and Anna-Maria Kanzola. 2022. "On the Micro-Foundations of Creative Economy: Life Satisfaction and Social Identity" Sustainability 14, no. 9: 4878. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094878

APA StylePetrakis, P. E., & Kanzola, A.-M. (2022). On the Micro-Foundations of Creative Economy: Life Satisfaction and Social Identity. Sustainability, 14(9), 4878. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094878