Abstract

This article presents a Finnish social design study that focuses on consumer perspectives and future expectations related to bio-based products and brands. The qualitative regional study addresses the global concern associated with sustainability of the bioeconomy. Because a gap in research was identified from the regional consumer perspective, the article presents a case study that was held with 50 consumers in Finland. The main research method was qualitative online focus group discussions, with an objective to gain an understanding of consumer behavior, motivations, concerns, and intentions related to bio-based products and brands. The results are presented according to the sustainability framework, which was constructed around four topics: (1) consumer awareness, (2) illustrated examples and their consumer acceptance, (3) consumption habits, and (4) future consumption behavior. The main findings indicate that Finnish consumers were extremely well-informed on the bio-based concept, and they trusted domestic regional brands the most. Throughout the research, Nordic consumers highlighted the role of companies and urged sensible science-based communication on the sustainability aspects. Finally, the results led to consider how the value-sensitive consumer insights may be utilized by proposing prominent impact assessment methods for decision-making in both the business and consumer sectors.

1. Introduction

Social design [1] and socially responsive design [2] have recently flourished as promising methodologies to address the inefficiency of existing models and policies targeting most pressing global concerns. Social design emphasizes the process of solving social problems with sustainable, ecological design, with carefully predefined community samples, and with the aim of social ecology transformation [3,4,5]. Accordingly, this design research presents a qualitative social study that was organized with 50 consumers in Finland, with an emphasis on the sustainability concern associated with bioeconomy. In more detail, the social study was carried out to capture consumers’ attitudes and motivations related to bio-based products (BBP) and brands. The research was carried out by designing a sustainability framework that included three regional studies: a qualitative online focus group discussion (this article) and two quantitative consumer surveys in Ireland and the Netherlands, both including 500 consumers [6]. The sustainability framework was built upon predefined topics: (1) consumer awareness, (2) illustrative examples and their consumer acceptance, (3) consumption habits, and (4) future consumption behavior. The concrete basis of the framework was applied from previous bio-based projects, e.g., RoadToBio, Open-Bio, Bioways, Bioforever, StarProBio, Biobridges, and Brand Perspectives [7,8,9,10,11,12,13], with the emphasis on the nominated framework dedicated to the specific social design objectives. This article also includes initial thoughts on how the qualitative consumer data may be utilized in more quantitative design contexts by proposing tools for future decision-making in the business and consumer sectors.

The article is structured in the following manner. Literature on bioeconomy, past research, and current available tools are reviewed in Section 2. Methodology—including the sustainability framework and used methods and materials—are reviewed in Section 3. Section 4 presents the results that are organized according to the framework: (1) consumer awareness, (2) illustrated examples and their consumer acceptance, (3) consumption habits, and (4) future consumption behavior. Subsequently, the article presents analysis on tools for future decision-making in the business and consumer sectors. Finally, Section 5 concludes with a discussion and summary of the research.

2. Literature

The bioeconomy encompasses all sectors and systems based on biological resources, i.e., animals, plants, micro-organisms, and derived biomass, including organic waste, as well as their functions and principles [14,15]. The EU bioeconomy employs over 18 million people and has a turnaround of around 2 trillion EUR (ibid.). One of the main priorities of the updated EU bioeconomy action plan, published in 2018, is to strengthen and scale up the bio-based sectors, for example by promoting innovative bio-based solutions and developing bio-based, recyclable, and marine biodegradable replacements for plastics. The bioeconomy can help in reaching the EU-wide target of at least 32% renewables by 2030 and finding solutions to replace fossil raw materials broadly across the European industrial sectors, such as construction, packaging, textiles, chemicals, cosmetics, pharma, and consumer products. The bio-based sectors will contribute to meeting the goals of circular economy, for example, by the valorization of organic waste, residues, and side streams by turning them into valuable bio-based products (BBP). Upon up-scaling and strengthening, the bio-based sector can achieve more than just replace fossil-based materials. It can support the renewal of European industrial base and improve the sustainability of industrial products. Sustainability and circularity are at the heart of the EU bioeconomy, and therefore recyclability and reuse of BBP are key elements, as is the protection of biodiversity, and the use of sustainable resources. The bioeconomy should be visible and understandable to everyone as the renewed action plan states that all Europeans can and should benefit from the bioeconomy wherever they live. For this purpose, the EU is taking action to ensure that the local bioeconomy is put to full use. From a wider perspective, the bioeconomy is Europe’s response to the environmental challenges threatening the planet. It can help in reaching the ambitious goals on carbon neutrality as well as the UN 2030 Agenda and Sustainable Development Goals related to responsible consumption and production, climate action, clean and affordable energy, and life below the water [16]. A sustainable bioeconomy in the EU is a necessity for building a carbon-neutral future, which is in line with the climate objectives of the Paris agreement [17,18].

According to the EU Bioeconomy Strategy update (2018), consumers and their behavior can play a major role in supporting the profound transformation required for successful transition to the bio-based economy [15]. Transforming consumption patterns alongside sustainable production is one of the most important movements to achieve the broader goals for sustainable development [19]. Although the rapidly evolving research field encompasses several bio-based product (BBP) domains, there seems to be a gap in research that focuses explicitly on the consumer perspective. Most previous studies (e.g., [8,9,10,11,12,13], principally EU-funded research projects) have evaluated the overall consumer knowledge, interest, and motivations, but have not addressed, e.g., the individual product categories. The previous studies indicate that consumers generally appear to have limited understanding and knowledge about the bio-based products [10,12,20], although they found positive perceptions associated with environmental and sustainability benefits [7,9,12]. In the abovementioned research, financial incentives seem to raise mixed results. For example, Ladu et al. (2021) found that the price is the most remarkable factor affecting consumer purchase decisions [11], but Hao et al. (2019) highlight that consumers have a strong willingness to pay for sustainable solutions [21]. In general, the consumer awareness towards the existence of BBPs seems to lie around 50%, while only 12% have consciously chosen bio-based products over conventional ones [13]. Lack of knowledge and misunderstanding seem to raise mixed and negative feelings towards BBPs [8,12]. The previous research indicates that more work is therefore needed, not only to improve consumer awareness on BBPs, but also to understand their motivations for purchasing BBP, especially in regional contexts. This information is important, as it can, e.g., guide the business sector in their practical investment decisions and marketing activities.

Since BBP businesses and brands may indeed have significant effect on consumers’ purchase decisions, this social study has also focused on the business perspective. According to Dammer et al. (2017), the brand influence can be a major driver of the success of bio-based products [22]. For example, a consumer study implemented in Slovakia clarified that over half of the consumers were influenced by brands when making their purchasing discissions [23]. One important sustainability factor for the business sector is circular economy (CE). In recent years, most companies have become aware of the environmental challenges and set their goals towards cleaner production and circular economy. The CE is a sustainable alternative to the linear model, where a reduced amount of materials is required to produce a constant level of products, either because of a reduction in the number of resources used or because the raw materials are replaced with recycled ones [24]. Different indicators that measure the level of CE have been defined: such as the eco-innovation [25], circular economy index [26], and material circularity indicator [27]. Based on the study implemented in Spain, the first firm steps towards circular business models have been taken, including waste recycling and treatment, energy efficiency, and reduction of the environmental impact [28]. Nevertheless, the sustainability-driven approach is complex, and requires transformation in different areas within the organizations.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methodology

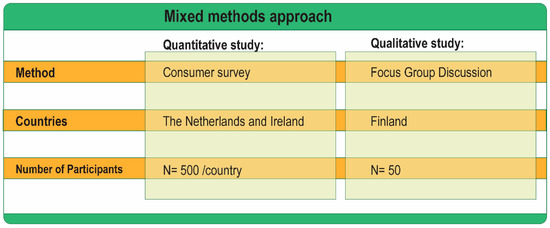

In social research, like in any qualitative research, it is common to build an investigation phase in order to develop a better understanding of the broader context together with the social ecology participants [4,5]. Geels (2011) has proposed creating a practical sustainability framework when studying new socio-technical innovations in any regime shift in order to sketch out the most important dimensions of the related issue and help to specify the types of questions that should be asked from the participants in the transition area [29]. The practical sustainability framework within the social research context falls under Value Sensitive Design, which is a theoretically grounded approach to the design of technology that accounts for human values [30,31]. In addition, the framework is built upon the Theory of Planned Behavior [32], which focuses on the attitudes towards the perception of a product. The hypothesis was to study the ethical values, subjective norms, attitudes, and behavioral intentions towards BBP of the regional study stakeholders as thoroughly as possible within the limitations of the study setup. In this context, the emphasis on capturing consumer feedback depends highly on community acceptance, which Huijts et al. (2011) label as citizen acceptance [33]. This refers to the behavioral responses within communities that are affected by the placement of a technological object close to home. In more detail, the framework applied mixed methods, as it is acknowledged that combining both qualitative and quantitative research methods in a social context can provide broader understanding of the topic [4], see Figure 1. This article limits itself to the qualitative case study that was organized with 50 consumers in Finland. The results from the quantitative part of the framework, conducted in Ireland and the Netherlands, are published by Gaffey et al. [6]. The sustainability framework encompassing the nominated three EU countries was developed for explicitly investigating customer perception of BBPs and brands.

Figure 1.

The approach employed for regional case studies. This article presents the qualitative case study (on the right).

The qualitative case study applied a semi-structured focus group discussion (FGD) to the research. The method offers researchers an opportunity to interview several respondents systematically and simultaneously and promote discussion among them [34,35]. In FGD, the onus is not on generalizable findings, but the purposeful use of social interaction in generating knowledge [35]. In order to tackle most common problems addressed with FGD as method, the focus groups in this study were constructed to be as homogenous as possible with similar demographics, as suggested by Acocella [36]. The intention was to ensure that the conversation remained on a level where it was easy for each participant to be engaged with the discussion and point out their personal opinions and experiences. In general, the benefit of FGDs is that the discussions can spark off one another, suggesting different dimensions and nuances of the original problem that any individual participant might not have thought of. Due to the rapid improvement of Internet facilities, the use of online FGDs has been a growing trend in research over the past decade [37]. Online FGDs can be divided into two categories: asynchronous (with no timing requirement) and synchronous (occurring exactly at the same time period) [38], of which the former was used in this framework. The framework included also some quantitative consumer surveys [39]—polls and open-ended questions—as much as the FGD permitted. The quantitative part was planned in parallel to the structured survey aimed at Irish and Dutch consumers. Once finalized, the content was translated from English to Finnish. (The English version of the FGD survey questionnaire is available online, please see the Supplementary Materials).

3.2. Materials for the Sustainability Framework

The first part of the framework, consumer awareness, was formulated under the research question: “How do consumers recognize or recall bio-based materials, products, and brands?”. It studied prior knowledge, which in practice refers to the ability for a consumer to recognize or recall BBP and the willingness to adopt and purchase them. The concepts for explaining the terminology (i.e., bio-based materials, products, and brands) were sought from previous studies [7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. The second part of the framework—examples and their consumer acceptance—presented five familiar regional examples of bio-based brands with the aim of studying the main incentives for consumers to choose BBP. The background research included the BBP examples (used, e.g., in [12,13]), in addition to open-access bio-based product galleries (accessed on 10 September 2020):

In regional studies, special emphasis was placed on the fact that the brands were familiar to the nominated consumer groups. In the Finnish study, the selected brands were Fazer, Lumene, Nestlé, Adidas, and Lego. The first two brands (Fazer and Lumene) are particularly familiar to Finnish consumers, and the latter three well-known global brands. The scientific background for all the brand narratives were studied to be based on solid and well-justified research. The third part of the framework, consumption habit, was formulated under the question: “What are the current consumption decisions, expectations, and habits?” This part essentially studied the main incentives and key barriers for consumers to choose bio-based alternatives. The questionnaire part exploited some material from the BioBridges project [12]. The fourth part, future consumer, was formulated under the research question: “What are the future concerns, willingness to adopt BBP, and future expectations for consumption?”. From this aspect, some earlier studies had briefly considered the consumer point of view (e.g., [9,11,12]) or they had focused on the positive and negative associations with BBP (e.g., [8]).

The qualitative, asynchronous Finnish FGD was implemented in December 2020. The one-week research period was facilitated by two researchers by assuring that the discussion threads remained active, and the received comments were logical and in line with the sustainability framework. The one-week research period allowed the participants to be more available and prepared, as compared to the quantitative questionnaire used in [6]. The employed collaboration platform was Howspace (manufacturer: Humap Software, Helsinki, Finland). The software was limited by the condition that the participants could not be forced to reply to the quantitative questions, which was opposite to the surveys in Ireland and The Netherlands. Therefore, the sample size (N) value is lower in some of the results section responses. During the research, the participants were able to see all answers from the other respondents in order to enable the discussions. The results from the polls became visible after answering each question.

The targeted consumer groups were citizens aged 36–50 with a family and consumers making buying decisions in their households. All participants were recruited via Bilendi Oy (a survey recruitment provider operating in several EU countries). For qualitative research, the sampling was sufficient and representative regarding the criteria towards gender, age, and geography. There was an even spread of respondents as to gender: 52% women and 48% men and with a sufficient age deviation (presented in Table 1). Participants lived in representatively different parts of Finland; 88% lived with their partner or spouse and children, and 12% with children. In the sample, 77% were the joint decision-makers in their household and 23% were the main decision-makers.

Table 1.

The age distribution of the online FGD participants.

All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before participating in the study. The research was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of VTT (approved on 24 November 2020). It should be noted that due to the specificity of the group selection and its size, the research results represent generalized knowledge of the entire population.

4. Results

Due to the small and geographically limited population sample (50 consumers in Finland), when relevant, the following results are presented according to the amount of responders/number of responses (denoted as n) rather than percentages. The exception is the thematic analysis and positive/negative association analysis, which presents relevant results with a percentage value. Both of these methods are based on the type of words the participants use when responding in the Howspace platform, and the percentage value is therefore counted based on the number of responses, not on the number of participants. Due to the software limitations, the participants could not be forced to reply to all questions, and therefore the sample size (n) may sometimes be lower for some responses. When the respondents were answering the open discussions or were allowed to choose multiple options, the n value became higher than 50.

4.1. Consumer Awareness about Bio-Based Products

In the first part of the framework, the FGD participants’ awareness about bio-based products and/or brands was studied. Based on the responses (n = 47), most of the participants felt that they were totally or to some extent aware of BBPs and brands (35 respondents), and only 6 somewhat disagreed. In more detail, the bio-based materials, products, and brands were introduced to the participants by two definitions created by the European Committee for Standardization and by the USDA BioPreferred program:

Definition 1.

“The term bio-based product refers to products wholly or partly derived from biomass, such as plants, trees, or animals (the biomass can have undergone physical, chemical, or biological treatment)”. (European Committee for Standardization [40,41]).

Definition 2.

“The term bio-based product refers to commercial or industrial products (other than food or feed) which are composed, in whole or in significant part, of biological products, including renewable domestic agricultural materials (e.g., plant, animal, and aquatic materials), forestry materials, intermediate materials, or feedstocks. As opposite, bio-based materials exclude motor vehicle fuels, heating oil, or electricity produced from biomass”. (USDA BioPreferred® Program) [42].

Based on the results, the observed difference between the two definitions was almost non-existent (see Table 2), although during the discussions, the consumers clarified that the first (shorter) one, seemed to be clearer. In six responses, Definition 1 was stated to be more understandable and concise than Definition 2. Three participants specifically favored Definition 2. Eight thought that both definitions were obvious at a glance, and six that they were overly complex. As a positive response, participants were eager to hear more about BBP based on these two definitions. In particular, they expected to hear more examples about the BBP in question. Open discussions were related to ethical issues, vegan alternatives, biomass, animal-based biomass, and biological treatment. The most concern was raised about the chemical treatment, e.g., “What is it …?”, “Definition is not clear”, and comments like, “It is always a risk to the environment”. Of all the responses, 42% had positive associations, 15% had negative associations, and 43% had neither a positive nor negative association or something in between.

Table 2.

Understanding of two different definitions for bio-based products by FGD participants (n = 47 for this question).

When requesting the first specific types of word associations with the term “bio-based product”, the words “organic”, “natural”, “ecological”, and “recyclable” were the primary answers (see the word cloud in Figure 2). Among those, there were 48% positive associations in the open discussion, with justifications being the product’s material, which is “based in nature”, “is manufactured from organic ingredients”, and “is just as biodegradable as the original material it was produced from”. Similarly, negative associations (22%) were related to the processing of the material, which we seen to be “as contaminating as the non-bio-based alternative”. It was also pointed out that after the process, the product may not be biodegradable at all. Some participants argued heavily that BBP “could be seen only as greenwashing”. They requested more research-based knowledge than brand-based knowledge and the need for the whole production chain to be environmentally friendly by stating: “If the manufacturing requires a lot of energy and chemicals, it is not an ecological alternative”. When asking about the companies and brands associated with the BBPs (open discussion, 66 responses), almost one third (19) of the responses chose the option “Nothing comes to mind”. The articulated domestic/regional brands in the open discussion were related to degradants (7), coating (7), garbage bags (5), food (5), forest industry (5), and cosmetics (3).

Figure 2.

Consumer awareness: word associations with “the bio-based product”.

4.2. Examples and Evaluation of Bio-Based Products

In the second part of the framework, well-known brands and their BBP solutions were presented to consumers with short narratives and illustrations (see Figure 3). Despite familiar brands, when issuing concepts that the consumers were not familiar with, it was seen as useful to present the topics in this way. The nominated brands were Fazer (food packaging), Lumene (cosmetics), Nestlé (drinking bottles), Adidas (shoes), and Lego (toys).

Figure 3.

Some examples of illustrations presented to FGD participants.

4.2.1. Fazer (Food Packaging)

A short narrative of Fazer’s solution was presented to the FGD participants:

“Fazer focuses on reducing emissions and the amount of food waste, develops more and more sustainable packaging, and increases the use of plant-based ingredients in its products. Recently, Fazer has brought pralines in a compostable, microplastic-free box to Christmas sales”.

According to Finnish consumers (n = 46), Fazer was seen as a trusted brand (44) (see Table 3). The participants also felt that the brand refers to sustainability (32). The minority felt that the work of Fazer towards a bio-based future was only greenwashing (13).

Table 3.

Brand evaluations by the FGD participants.

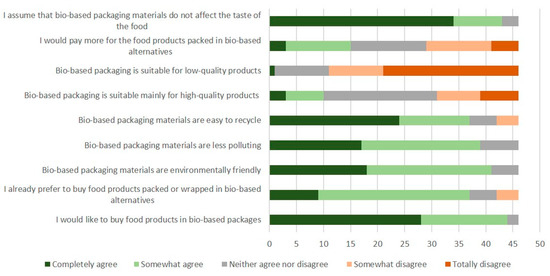

Generally, related to bio-based food packaging materials, consumers felt that bio-based packaging does not affect the taste of the food inside (43), and they would like to buy products in bio-based packages (44) (see Figure 4). In addition, the consumers felt that bio-based packaging materials were environmentally friendly (41), less polluting (39), and easy to recycle (37). Most consumers (37) stated that they already preferred to buy food products wrapped in bio-based alternatives. Only 15 of the consumers were willing to pay more for the food products packed in bio-based materials.

Figure 4.

Evaluation of bio-based food packaging materials.

As with other food and beverage products covered by bio-based materials, consumers expected to see vegetables, fruits, dairy products, juice, meat, and pre-cooked meals. Consumers expressed that, in general, “The amount of packaging materials in total should be decreased”, and the use of bio-based materials should be significantly increased: “I hope all the packages could be bio-based materials in the future”. However, some consumers were more skeptical, e.g., “Are the bio-based packages really microbiologically and hygienically comparable to plastics?”. Evidently, the work for a more sustainable future was seen as valuable, as one of the respondents commented: “The plans are encouraging; waiting eagerly for new innovations”.

4.2.2. Lumene (Cosmetics)

A short narrative of Lumene’s solution was presented to the FGD participants:

“Lumene has replaced the exfoliating rinse-off plastic microbeads with salt and silica sand-like ingredients. Many of Lumene products are also developed from by-products of food and forestry. The aim is to replace packaging materials with bio-based or biodegradable materials”.

According to Finnish consumers (n = 45), Lumene was seen as a trusted brand (33) (see Table 3). The participants also felt that the brand refers to sustainability (28). A minority (12) felt that the work of Lumene towards a bio-based future was only greenwashing.

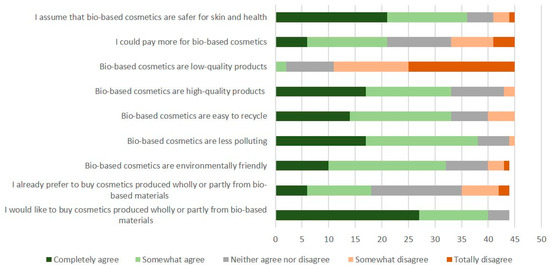

Consumers generally felt that bio-based cosmetics were safer for skin and health (36), and they would like to buy cosmetics produced wholly or partly from bio-based materials (40) (see Figure 5). Consumers also felt that bio-based cosmetics were environmentally friendly (32), less polluting (38), and easy to recycle (38). Only 18 consumers stated that they already preferred to buy bio-based cosmetics. In general, the participants felt that bio-based cosmetics were high-quality products (33). About half of the consumers (21) would pay more for cosmetic products packed in bio-based alternatives.

Figure 5.

Evaluation of bio-based cosmetics.

In the open discussions, the participants articulated that “The use of bio-based cosmetics will increase in the near future” and that “Bio-based cosmetics should be the new normal”. Consumers felt that current prices for bio-based cosmetics were too high: “I would like to try bio-based cosmetics. However, those are usually too expensive”. The general idea of bio-based cosmetics was yet intriguing: “It’s good that plastics are replaced. It’s altogether a different thing whether the product is any more sustainable than the original option”, and an important remark was pointed out: “Allergies must also be taken into account in bio-based cosmetics”.

4.2.3. Nestlé (Drinking Bottles)

A short narrative of Nestlé’s solution was presented to the FGD participants:

“Nestlé aims to develop 100% bio-based bottles. Focusing on waste biomass such as cardboard and sawdust, the goal is to bring Origin Materials technology to commercial scale, making bio-based PET accessible for the entire beverage industry”.

According to the Finnish consumers (n = 45), Nestlé was not seen as a trusted brand as the domestic, regional brands: less than half (18) held Nestlé as a trusted brand (see Table 3). Only seven thought that the brand was associated with sustainability, and more than half (25) felt that the work of Nestlé towards a bio-based future was only greenwashing.

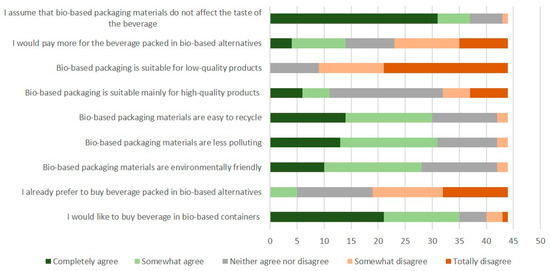

Generally, related to bio-based beverage and food packaging, the consumers (n = 44) felt that bio-based materials (in bottles) do not affect the taste of the food inside (37), and they would like to buy products in bio-based packages (35) (see Figure 6). In addition, the consumers felt that bio-based bottles were environmentally friendly (28), less polluting (31), and easy to recycle (30). Only five participants explained that they already preferred to buy beverage/food products packed or wrapped in bio-based alternatives. Only 14 would pay more for beverage and food products packed in bio-based alternatives.

Figure 6.

Evaluation of bio-based packaging materials for bottles.

Consumers felt that in general, the replacement of plastics in bottles is “Going in a better direction” and “Absolutely a great idea due to the huge consumption of plastic bottles”. Skeptical remarks towards the sustainability of bio-based bottles were expressed: “Are the bio-based bottles even as sustainable as the recycled plastic bottles?” and “How to recycle bio-based bottles?”. The regional consumer group felt that the recycling of bottles works efficiently in Finland due to the inclusive deposit and reuse system.

4.2.4. Adidas (Shoes)

A short narrative of the Adidas’ solution was presented to the FGD participants:

“Adidas aims to produce shoes from 100% biodegradable material created from biopolymers that aims to replicate natural silk. The company has pledged to eliminate virgin plastic from its supply chain”.

According to the Finnish consumers (n = 43/44), Adidas was not seen as a trusted as the regional, domestic brands. Less than half (16) held Adidas as a trusted brand (see Table 3). Only six participants thought that the brand refers to sustainability, though less than half (16) felt that the work of Adidas towards a bio-based future is greenwashing.

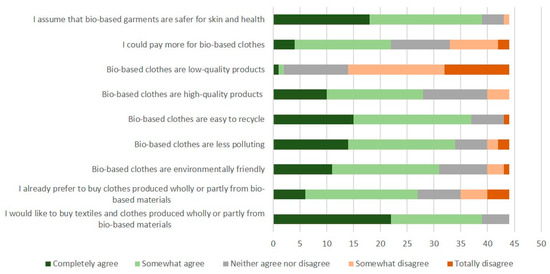

In general, consumers felt that bio-based garments are safer for skin and health (39), and they would like to buy textiles and clothes produced wholly or partly from bio-based materials (39/44) (see Figure 7). Consumers also felt that bio-based clothes were environmentally friendly (31), less polluting (34), and easy to recycle (37). More than half (27) stated that they already preferred to buy clothes produced wholly or partly from bio-based materials. They felt that bio-based clothes were high-quality products (28). Only half of the respondents (22) would be willing to pay more for bio-based clothes.

Figure 7.

Evaluation of bio-based garments.

Consumers felt that in general, they would like to see more bio-based clothes in the future, by expressing “I hope bio-based materials will be then commonly used”. One respondent commented that “If the price of clothing increases because of the higher quality and ecological origin, it is ok. Modern fast fashion is shocking and completely pointless”. Still, consumers were skeptical about the durability of the bio-based clothes and their actual environmental friendliness.

4.2.5. Lego (Toys)

A short narrative of the Lego’s solution was presented to the FGD participants:

“Recently called the ‘world’s most powerful brand,’ toy manufacturer Lego is looking for a bio-based replacement for its iconic plastic bricks. Lego is developing sustainable raw materials to manufacture elements as well as packaging materials”.

According to Finnish consumers (n = 44), Lego was a trusted global brand (33) (see Table 3). In general, the participants thought that the brand refers to sustainability (26). Only a minority of the respondents (7) felt that this was only greenwashing. In addition to Lego, other games or toys were mentioned as suitable for BBP, such as board games, beach toys and other outdoor toys, infant toys, all plastic toys, dollhouses, books, craft material, train tracks, and game controllers.

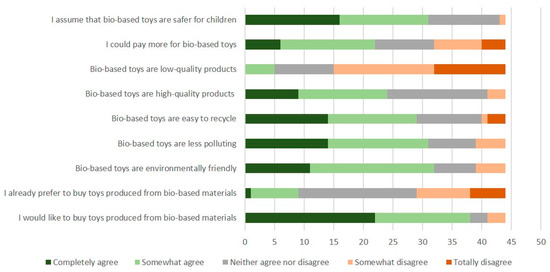

In general, the consumers felt that the bio-based toys were safer for children (31) and they would like to purchase toys produced from bio-based materials (38) (see Figure 8). The participants felt that bio-based toys were environmentally friendly (32), less polluting (31), and easy to recycle (29). Only nine stated that they already preferred to buy toys produced from bio-based materials. They felt that bio-based toys were high-quality products (24). Half of the respondents (22) stated that they would pay more for bio-based toys.

Figure 8.

Evaluation of bio-based toys.

Consumers felt that “Lego is a valuable brand, and it could act as a good example for others”. By this, they were referring to the huge number of plastics products in families. The participants saw a lot of potential in toys and their packaging. One participant expressed “I really hope that the bio-based toys are the new normal in the future”. Still, they clearly pointed out that “Safety is the most important issue in this context”.

4.3. Consumption Habits

About shopping habits, Finnish consumers (n = 45) stated that they were mainly looking for familiar brands (34 responses) and did not actively try to find bio-based products (25 responses). Twenty-seven did not rely on trusted brands to provide them with BBP solutions. Only 16 compared BBP with similar alternatives when they were making consumption decisions and preferred the bio-based option. Thirty-one felt that it was not easy to find BBP in the store or in supply. The consumers experienced that there was a severe lack of communication regarding BBP. In more detail, the communication was not clear (26) and/or the product labels were not understandable or easy to read (24). Regarding information, 17 mentioned that it was usually the advertisements that led them to find BBP.

When choosing between several products, the following issues were stated as affecting their decision to buy specific brands (n = 31): well-recognized, familiar, domestic/local product (11); price (8); familiar brand/company and reputation (7); quality and reliability (6); durability, functionality, and need (6); advertising campaigns and/or outer appearances (6); recommendations (5); quality-to-price ratio (4); and environmental friendliness (3). When choosing between similar products (n = 29), the most important factors were country of production (9), product quality (9), packaging solutions (4), country of origin (3), prior experience (3), usability (3), and brand image (3).

In the open discussions, the consumers articulated these responses in more detail. Positive associations were received in 17.5% of the responses, including statements such as “I recycle all plastics. Any new solutions for packaging materials are always interesting”. Negative associations were received in 32% of the responses. Here, the concerns were related to the accuracy of available information, e.g., “I wonder how exact the information about the bio-based products are. Are they even safe at all?”, or they were related to the lack of communication: “The first distressing things that come to mind are the terrace garden materials and single-use plastics. I have not seen much communication about those”. Comments that were neither negative nor positive or something in between were given in 47% of the responses. Here, the consumers pointed out that they had not paid much attention to the available options: “I have not given much thought to the bio-based brands. There seems to be a lack of ads and communication”. Some felt that there were more important factors that affected their decision-making than bio-based materials: “I prefer the bio-based alternatives, if they are available. Otherwise, the bio-based solution is just some extra benefit. It is seldom the critical factor that determines the final choice”.

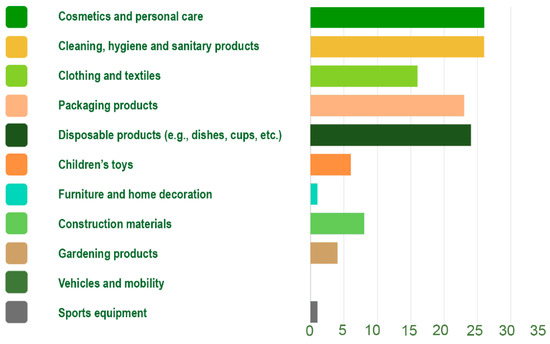

Finnish consumers perceived that out of 11 predefined categories (the participants were able to choose up to three options; total responses n = 136), the most interesting BBP sectors were related to cosmetics and personal care (26), cleaning, hygiene, and sanitary products (26), disposable products (24), and packaging products (23), in addition to clothing and textiles (16) (see Figure 9). The reason consumers chose these options included: “They are easily available”, “I use them already”, “I thought that bio-based materials would suit well for those categories”, and “I selected products that have a short life-span and are consumed a lot”.

Figure 9.

Sectors of interest to Finnish consumers for buying bio-based products.

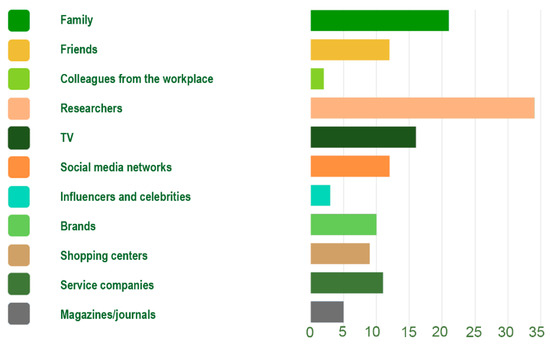

Out of 11 predefined categories (the participants were able to choose any number of options; total responses n = 136), the most influential media or social connection from which the participants preferred to receive or share information about the BBP were researchers (34), family (21), and television (16) (see Figure 10). The consumers felt that “Fact-based knowledge and research data is the most reliable source of information”; some preferred newspaper articles. Consumers also pointed out the importance of information being easily available: “Information should be easily available, even when one is not specifically pursuing it”. Social media was pointed out as being influential and visible: “I react mostly to social media”. Some consumers felt that the advertisements (from different media sources) were more appealing, although others mentioned that they were not able to trust those at all. As for BBP, consumers were keen to discuss the issues with their families and friends.

Figure 10.

The most interesting channels for the Finnish consumers to receive information about BBP.

4.4. Future Consumer

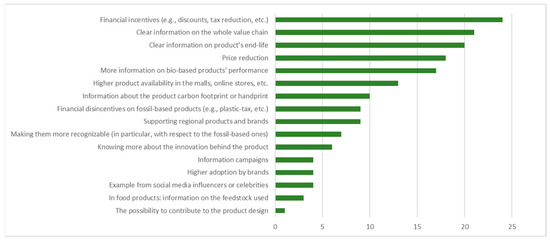

The Finnish participants (n = 44) felt that they were going to buy more bio-based products (41) and more products packaged in bio-based materials (43) in the future. Consumers felt that financial incentives (25), clear information about the entire value chain (21), and the product’s end-life (20) were among the most important motivational factors affecting future behavior toward bio-based products (see Figure 11). They were less motivated from the possibility to contribute to the product design (1), information on the feedstock used in food products (3), higher adoption by brands (4), information campaigns (4), and example from social media influencers or celebrities (4).

Figure 11.

Motivation to buy bio-based products.

In the open discussion (analyzed with thematic analysis, including 57 responses) about the incentives and expectations of future consumption, 17 participants highlighted reasonable price, stating that “Eco is not just a privilege for the wealthy”, and especially underlined the role of brands and their quality–price responsibility. About the higher price, the participants urged brands to “Demonstrate some certificate that would verify that they really are environmentally friendly” and emphasized that “They should also take into account the manufacturing and end-of-life cycle.” Some consumers (8) required more information, by stating “Motivation is about understanding why the bio-based alternatives are better; this can be informed by the labeling” and “Fact-based knowledge should be presented in a way that is easy to understand.” Few consumers (7) mentioned “environmentally friendly products” as their main motivation, specifying: “Having a clear conscience”, “Saving the planet”, “Making good”, and “Achieving more”. Some participants (4) mentioned that the bio-based alternatives should be: “Mainstream offering in the selection”, and “Natural alternatives in compact sizes”. In individual answers, the participants brought up issues relating to quality, trustworthiness, benefit, “carrot rather than stick”, and user experience.

When asked about whether the participants saw bio-based materials as a solution to environmental challenges in the future (open discussion, thematic analysis, total responses n = 56), only three responses were positive. Finnish consumers stressed that the problem can be issued only “As part of the whole” (14)—“Together with other solutions”, “BBPs are part of solution, but not enough by themselves”, “The overall burden of chemicals and contamination counts”, “The Western world cannot solve these problems alone”. Some consumers (6) were overly skeptical, stating that the bio-based alternatives had little influence on climate change and more information was needed on the complete lifecycle effects and consumption reduction. In the individual answers, the participants articulated that “The non-bio-based alternatives are equally important when recycled properly”, and referred to the efficient recycling of plastics: “Bio-particles in the oceans are a huge concern” and “It depends on how globally inclusive the bio-based concept is”.

In the open discussions (with thematic analysis; total responses n = 25), the FGD participants stated that the environmental issues should be communicated to consumers:

- Honestly, without cover-up stories, no greenwash (7)

- Openly and transparently (5)

- With research and fact-based knowledge (5)

- Multifaceted or multichannel information with wide distribution (2)

- With clear customer-driven communication (2)

- All benefits and disadvantages clearly on the table (1)

- By presenting all global players and subcontracting parties (1).

The participants (n = 53) saw that the major advantages of the BBP and materials were recyclable materials, compostable, waste reduction, and fast degradability (18); environment friendliness, less pollution, consumes fewer planet resources (7); naturalness, make use of natural materials (4); no end-of-lifecycle pollution aspects (2); sustainable development (2); creation of new employment (2); and “safety and reliability—safer for all living organisms” (1). In the individual answers, the participants highlighted such topics as ecological awareness, depletion of natural resources, cleanness, non-toxicants, regeneration, manageability, fair for future generations, and better solutions for saving the planet.

The biggest concerns, risks, and negative impacts related to BBP and materials were contemplated in the open discussions (thematic analysis; total responses n = 53). In 13 responses, the Finnish consumers highlighted harm to the environment, i.e., intensive farming, the destruction of the rain forests, and BBP agriculture replacing fields and natural forests. Some consumers (12) emphasized manufacturing and its costs as having the most negative impact. Manufacturing was seen as severely polluting, as it consumes more energy than the non-bio-based alternatives. Consumers were also looking for more information on who, where, and how the BBP is manufactured. In addition, in 10 responses, the higher price was seen to create an overwhelming barrier for using BBP. Consumers felt that they were also misinformed, since bio-based alternatives are promoted as being ecological, although in reality, they are not (4). Participants were also skeptical about the durability (4) and safety (4) of the bio-based products, since the BBP definitions allowed the use of toxic chemicals and created hazardous emissions.

As a final part, the FGD participants were asked about the COVID-19 situation and whether it had made consumers more cautious regarding BBP alternatives. The participants (thematic analysis; total responses n = 56) responded that COVID-19 had no effect (9) or not much effect (3) on their consumption behavior: “As for the part of the bio-based alternatives, there is some increase, but not due to COVID-19”. The minority (2) felt that the pandemic had some effect on their consumption behavior: “It has forced me to think about the overall situation of the planet, but not so much everyday consumption”. Some participants (3) emphasized that COVID-19 had caused less consumption since “Money is saved because of the lack of eating out, culture, and entertainment”. In individual answers, it was stated that the consumption was steered towards sustainable behavior: “There is more time to pick berries”, or “Buy used clothes and toys from the flea market”.

5. Discussion

The bio-based industry is characterized by the challenges in terms of risk and uncertainty, that are related to four main key issues encompassing the bio-based economy, i.e., (1) the sustainability of bio-based products; (2) the costs and prices of conventional versus bio-based products; (3) consumer acceptance and demand for bio-based products; and (4) the bridging of the circular bio-based economy to other sustainable pathways [43]. In this social research context, the objective was to focus on these general challenges, in addition to building a framework that highlights the explicit regional consumer perspective. Previous research has done efficient work in delineating public perception of bio-based products and brands in the broader context by focusing on the social acceptance [8], consumer willingness to pay for bio-based products [44], in addition to comprehensive societal needs and concerns [9]. The sustainability framework was pursued to understand the future consumers’ attitudes, motivations, drivers, and concerns related to BBPs and brands in the regional context. The framework was constructed around: (1) consumer awareness, (2) illustrating examples and their consumer acceptance, (3) consumption habits, and (4) future consumption behavior. Previous consumer research on BBP already demonstrated how the public seems to have a positive attitude and interest in bio-based products [7,9,12], which was also verified in this regional case study. The results were also in accordance with earlier studies [6,7,9,13], which revealed that consumers find BBP trustworthy, recognize their potentially positive environmental impact, and are willing to pay more for BBP of the same functionality and properties. In addition, consumers felt that their individual purchasing choices can have a positive impact on the environment, as recalled by [24].

The first part of the sustainability framework studied consumer awareness, aiming to define how the FGD participants recognized or recalled bio-based materials, products, and brands. The results showed that the Finnish consumers were educated and well-informed as they were able to understand the presented BBP definitions and their deviancy, and also familiar with bio-based products, unlike previous studies in which the majority of consumers were not acquainted with those [7,8]. Moreover, the parallel study implemented in the Netherlands and Ireland verified that most consumers (77% and 72%) were not familiar with any BBP and brands [6]. The participants of our Finnish study enumerated several (mostly domestic) brands associated with the BBP in relation to degradants, coating, garbage bags, food products, forestry, and cosmetics. This is somewhat in accordance with [8], in which consumers associated the term strongly with clothing, degradants, cosmetics, food products, and cleaners. When requesting the first specific types of word associations with the term “bio-based product”, the words “organic, natural, ecological, and recyclable” were the primary answers. This is again directly in accordance with [8], where respondents also mentioned “organic”, “natural”, “ecological”, and “recyclable”. In more detail, the participants in our FGD study raised important questions about ethical issues, vegan alternatives, biomass, and animal-based biomass, in addition to biological and chemical treatment.

The second part of the framework illustrated five examples of well-known brands: Fazer, Lumene, Nestlé, Adidas, and Lego and their plans for the bio-based future. The latter three global brands were already presented in previous studies [22,23]; however, those did not study their consumer acceptance. From the brands evaluated in our study, Fazer was the most trusted among the Finnish consumers regarding BBP, with Lumene and Lego sharing second place. The same brands were also referred to as the most trusted ones regarding sustainability and their work towards a bio-based future was not seen as greenwashing. Regarding product sectors, the consumers preferred to buy food, nutrients, and liquids packaged in bio-based materials. Cosmetics, textiles/clothes/garments, and toys were also mentioned. In general, the participants thought that BBP and bio-based packaging materials were environmentally friendly, less polluting, and easy to recycle. However, Finnish consumers were not willing to pay more for bio-based options, which is in accordance with the study of Ladu et al. [11]. This, however, contradicts the parallel study in the Netherlands and Ireland [6], where the main motivational criteria for consumers were lower price and functionality of the product. Based on previous studies, consumers are willing to pay extra for special product categories, such as “green premium” [1,13,44]; according to Gaffey et al. (2021), they are willing to pay even 25–50% extra price for this BBP sector [13].

The third part of the framework, consumption habits, elicited consumption decision-making, expectations, and current habits, i.e., the main incentives and key barriers when choosing bio-based alternatives. As a result, Finnish consumers were mainly looking for certain brands that they were already familiar with and did not actively try to find BBP. In contrast, the Dutch (81%), and especially Irish consumers (93%) prefer buying bio-based products as opposed to fossil-based ones [6]. The most interesting BBP sectors were related to cosmetics and personal care, cleaning, hygiene and sanitary, disposable, and packaging products. In the parallel study in the Netherlands and Ireland, the preferred BBP sectors were packaging, disposable, and cleaning, hygiene and sanitary products [6]. The interest of Finnish consumers towards bio-based cosmetics and personal care products might result from the strong Finnish cosmetics brand, Lumene. For the main incentive affecting the overall buying decision of any BBP, most participants highlighted that the product should be familiar, domestic/local, and well-recognized. Price came in the second position, and brand (image, familiar company, and/or reputation) in third. In essence, the participants highlighted the lack of fact-based communication related to bio-based products, which manifested itself in the product labels and advertisements. Previous research highlighted that the differences between “bio-based”, “bioplastic”, “biodegradable”, and “compostable” are not yet clearly communicated by brands [13]. The terms are often used interchangeably, clouding understanding of the products labeled as such; for instance, Coop and Unilever communicate on bioplastics without specifying which materials are bio-based or biodegradable (ibid.). In several discussion threads of our FGD study, the consumers highlighted the role of “Fact-based knowledge that should be presented in a way that is easy to comprehend”. The most influential media and social connections for the Finnish consumers were researchers, family, and television.

The last part of the sustainability framework, the future consumer, focused on future concerns, the willingness to adopt BBP, future expectations, and consumption in the future. In essence, the Finnish consumers expected to buy more BBPs and products packaged in bio-based materials, as was also the case with the parallel study implemented in the Netherlands and Ireland [6]. The highest motivation was aroused by financial incentives (e.g., price reduction, discounts, tax reduction, etc.), and lower motivation was associated with the higher adoption by brands, information campaigns, and social media influencers/celebrities. In general, when considering the pros and cons of the bio-based products and materials, the Finnish participants saw that the biggest advantages were recyclable materials, compostability, reducing of waste, fast degradability, environmental friendliness, less pollution and naturality. About the biggest concerns, risks and negative impact related to bio-based products and materials, the participants raised harm to the environment, intensive farming, manufacturing (cost of it, consumes more energy than non-bio-based alternatives, information about it: who, where, how is manufacturing the products); higher price; and in some cases, disinformation (bio-based alternatives are promoted being ecological although they are not). This is in accordance with the findings of [8], in which the negative associations were joined with higher costs, marketing tricks, and low availability. In our study, the participants expressed their desire for environmental issues to be communicated honestly, with no cover-up stories or greenwashing, and with all the benefits and disadvantages clearly visible. The consumers highlighted the role of companies—that more information and transparency on their part was needed, which should be presented by some sort of certification related to environmental aspects. These responses can be categorized as characteristic for the well-informed Finnish respondents.

6. Conclusions

The limitations of the qualitative social design study are well acknowledged. Chen et al. clarify that social design researchers often produce “local” understanding that describes the context, that cannot be applied to other, even similar, cases, and the results may be considered temporary rather than long-standing [1]. In contrast, the strength of the qualitative social design research is the in-depth perception and active user participation that is conducted with a longer timespan than, e.g., questionnaire-based quantitative research. In essence, our research was based on the local understanding with a limited qualitative regional study sample comprising 50 consumers in Finland that focused on the consumer perspective and future expectations related to bio-based products (BBP) and brands. Throughout the article, the results were supplemented with the quantitative surveys conducted in Ireland and the Netherlands, published by Gaffey et al. [6], in order to give perspective to the regional study and overcome the limitations of the qualitative research. As stated in the introduction, combining both qualitative and quantitative research methods in the social context can provide a broader understanding of the topic [4].

While solutions to large-scale social problems were beyond the means of this article, there remain several design problems that can be addressed with a proper choice of available methods that are not currently utilizing consumer-related value-sensitive data optimally, or at all. In order to make better use of the results, ideas, and opinions of such well-informed responders as the FGD participants (likely to be found in many countries with a highly educated consumer base), we propose the establishment of a firmer link between the use of value-sensitive consumer data and various design practices in order to utilize both qualitative and quantitative data inputs. The FGD consumer research highlighted the questions and value statements related to the lifecycle assessment and lifecycle cost. Better utilization of high-quality answers should be enabled and welcomed by all parties associated with design and decision-making in academia, governance, and private companies who wish to engage customers in a meaningful dialogue. It is important to note that while the impact assessment methods introduced in this article (LCA, LCC, SLCA, and SD) can help companies to study the possibilities related to diminishing their environmental impacts and improving their financial performance, they can also be helpful in engaging customers by providing them with verifiable (standards-respecting) data and scientifically sound performance measures, which can help customers make informed decisions. On the other hand, the transparency and common understanding of the rules and principles of the environmental indicators will make it more difficult for companies to “greenwash” their products, as the future customers will demand effective, science-based environmental actions.

Our future work will continue by developing a sustainability assessment tool that focuses on the environmental aspects. Based on the research presented in this article, we argue that combining methods and tools covering both the environmental and social aspects is a promising opportunity for future BBP development. Currently, the social LCA (SLCA) is still in the development phase, but there is continuous progress in the relevant guidelines, databases, and standards supporting the implementation of SLCA in practice. The social aspects are expected to become all the more important with the new EU legislation and directive for corporate sustainability reporting, which also increases the demands related to reporting of social issues.

Supplementary Materials

The questionnaire used in the asynchronous online FGD is available online (18 March 2022) at: https://publications.vtt.fi/julkaisut/muut/2022/BioSwitch-Appendix_A.pdf.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: T.K. and K.V.; methodology: T.K., K.V.; validation: T.K. and K.V.; formal analysis: T.K., K.V., H.K., T.V.-K. and S.M.; investigation: T.K. and K.V.; resources: H.K.; data curation: T.K. and K.V.; writing—original draft preparation: T.K., K.V., H.K., T.V.-K. and S.M.; writing—review and editing: T.K.; visualization: T.K. and K.V.; supervision: T.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was conducted in the context of the project BIOSWITCH (Encouraging Brand Owners to Switch-to-Bio-Based in highly innovative ecosystems). This research was funded by the Bio-Based Industries Joint Undertaking (JU) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program, grant agreement number 887727.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of VTT (on 24 November 2020) for studies involving humans. Statement of the Ethical Committee of VTT is available online (18 March 2022) at: https://publications.vtt.fi/julkaisut/muut/2022/BioSwitch-Ethical_assesment.pdf.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of VTT (on 24 November 2020). The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy issues.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Munster Technological University (MTU) and BTG Biomass Technology Group BV (BTG) who carried out a parallel study in Ireland and the Netherlands and provided support in formulating the research questions. The authors would also like to acknowledge the role of Bilendi Oy in supporting the recruitment of consumer respondents to undertake this study. The images for Figure 3 are open-source materials from Pixabay.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Chen, D.S.; Cheng, L.L.; Hummels, C.; Koskinen, I. Social Design: An Introduction. Int. J. Des. 2016, 10, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Julier, G.; Kimbell, L. Keeping the System Going: Social Design and the Reproduction of Inequalities in Neoliberal Times. Des. Issues 2019, 35, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sanders, E.B.-N.; Stappers, P.J. Co-Creation and the New Landscapes of Design. CoDesign 2008, 4, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Björgvinsson, E.; Ehn, P.; Hillgren, P.A. Participatory Design and “Democratizing Innovation”. In Proceedings of the 11th Biennial Participatory Design Conference, Sydney, Australia, 29 November–3 December 2010; pp. 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzini, E. Design When Everybody Designs. An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation. Techne J. Technol. Archit. Environ. 2017, 13, 360–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffey, J.; McMahon, H.; Marsh, E.; Vehmas, K.; Kymäläinen, T.; Vos, J. Understanding consumer perspectives of bio-based products—A comparative case study from Ireland and The Netherlands. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfau, S.; Vos, J.; Dammer, L.; Arendt, O. Public Perception of Bio-Based Products. RoadToBio Deliverable D2.2. 2017. Available online: https://www.roadtobio.eu/uploads/publications/deliverables/RoadToBio_D22_Public_perception_of_bio-based_products.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2021).

- Meeusen, M.; Peuckert, J.; Quitzow, R. Acceptance Factors for Bio-Based Products and Related Information Systems. Open-Bio Deliverable D9.2. 2015. Available online: https://www.bioeconomy-library.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Acceptance-factors-for-bio-based-products-and-related-information-systems.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2021).

- Delioglamnis, I.; Kouzi, E.; Tsagaraki, E.; Bougiouklis, M.; Tollias, I. Public Perception of Bio-Based Products—Societal Needs and Concerns (Updated Version). BIOWAYS Deliverable D2.4. 2018. Available online: http://www.bioways.eu/download.php?f=307&l=en&key=f1d76fb7f2ae06b3ee3d4372a896d977 (accessed on 18 June 2021).

- Carus, M.; Partanen, A.; Piotrowski, S.; Dammer, L. Market Analysis, BIOFOREVER Deliverable D7.2. 2019. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/720710/results (accessed on 18 June 2021).

- Ladu, L.; Wurster, S.; Clavell, J.; van Iersel, S.; Ugarte, S.; Voogt, M.; Falcone, P.M.; Imert, E.; Tartiu, V.E.; Morone, P.; et al. Acceptance Factors among Consumers and Businesses for Bio-Based Sustainability Schemes. STARProBio. Deliverable D5.1. 2019. Available online: http://www.star-probio.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/STAR-ProBio_D5.1_final.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2021).

- Sabini, M.; Cheren, S.; Borgna, S. D6.2, Action Plan for Raising Consumers’ Awareness. BIOBRIDGES Deliverable, D6.2. 2020. Available online: https://www.biobridges-project.eu/download.php?f=310&l=en&key=dd712023b6d8ddeb450d971a18048ee1 (accessed on 18 June 2021).

- Gaffey, J.; McMahon, H.; Marsh, E.; Vos, J. Switching to Biobased Products—The Brand Owner Perspective. Ind. Biotechnol. 2021, 17, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Bioeconomy: The European Way to Use Our Natural Resources. 2018. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/775a2dc7-2a8b-11e9-8d04-01aa75ed71a1/language-en/format-PDF/source-search (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- European Commission. Updated Bioeconomy Strategy—A Sustainable Bioeconomy for Europe: Strengthening the Connection between Economy, Society and the Environment; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/publications/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- United Nations. Paris Agreement. 2015. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Yildirim, S. The Consumer Role for Sustainable Development: How Consumers Contribute Sustainable Development Goals. In Anthropological Approaches to Understanding Consumption Patterns and Consumer; Chkoniya, V., Oliveira Madsen, A., Bukhrashvili, P., Eds.; IGI GLOBAL Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 325–328. [Google Scholar]

- Skoczinski, P.; Carus, M.; de Guzman, D.; Käb, H.; Chinthapalli, R.; Ravenstijn, J.; Baltus, W.; Raschka, A. Bio-Based Building Blocks and Polymers—Global Capacities, Production and Trends 2020–2025; Nova-Institute: Hürth, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, Y.; Liu, H.; Chen, H.; Sha, Y.; Ji, H.; Fan, J. What affect consumers’ willingness to pay for green packaging? Evidence from China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dammer, L.; Carus, M.; Iffland, K.; Piotrowski, S.; Sarmento, L.; Chinthapalli, R.; Raschka, A. Current Situation and Trends of the Bio-Based Industries in Europe with a Focus on Bio-Based Materials—Pilot Study for BBI JU; Nova-Institute: Hürth, Germany, 2017; Available online: https://www.bbi.europa.eu/sites/default/files/media/bbiju-pilotstudy.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2021).

- Chovanováa, H.; Korshunovb, A.I.; Babčanovác, D. Impact of brand on consumer behavior. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 34, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Figge, F.; Givry, P.; Canning, L.; Franklin-Johnson, E.; Thorpe, A. Eco-efficiency of virgin resources: A measure at the interface between micro and macro levels. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 138, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smol, M.; Kulczycka, J.; Avdiushchenko, A. Circular economy indicators in relation to eco-innovation in European regions. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2017, 19, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Di Maio, F.; Rem, P.C. A robust indicator for promoting circular economy through recycling. J. Environ. Prot. 2015, 6, 1095–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation and Granta Design. Circularity Indicators: An Approach to Measuring Circularity. May 2015. Available online: https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/topics/circular-economy-introduction/overview (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Aranda-Usón, A.; Portillo-Tarragona, P.; Scarpellini, S.; Llena-Macarulla, F. The progressive adoption of a circular economy by businesses for cleaner production: An approach for a regional study in Spain. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. From Sectoral Systems of Innovation to Socio-Technical Systems: Insights about Dynamics and Change from Sociology and Institutional Theory. Res. Policy 2004, 33, 897–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, B.; Kahn, P.H.; Borning, A.; Huldtgren, A. Value sensitive design and information systems. In Early Engagement and New Technologies: Opening up the Laboratory; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 55–95. [Google Scholar]

- Borning, A.; Muller, M. Next steps for value sensitive design. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Austin, TX, USA, 5–10 May 2012; pp. 1125–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Azjen, I. The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 1113–1127. [Google Scholar]

- Huijts, N.M.; Molina, E.J.; Stegb, L. Psychological factors influencing sustainable energy technology acceptance: A review-based comprehensive framework. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 16, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhurst, R. Semi-structured interviews and focus groups. Key Methods Geogr. 2003, 3, 143–156. [Google Scholar]

- William, B. Evaluating the Efficacy of Focus Group Discussion (FGD) in Qualitative Social Research. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2012, 3, 54–57. [Google Scholar]

- Acocella, I. The Focus Groups in Social Research: Advantages and Disadvantages. Qual. Quant. 2012, 46, 1125–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, K.; Williams, M. Researching Online Populations: The Use of Online Focus Groups for Social Research. Qual. Res. 2005, 5, 395–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, F.E.; Morris, M.; Rumsey, N. Doing Synchronoush Online Focus Groups with Young People: Methodological Reflections. Qual. Health Res. 2007, 17, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granello, D.H.; Wheaton, J.E. Online data collection: Strategies for research. J. Couns. Dev. 2004, 82, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Committee for Standardization. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/sectors/biotechnology/bio-based-products_en (accessed on 9 March 2022).

- Kutnik, M.; Suttie, E.; Brischke, C. Durability, efficacy and performance of bio-based construction materials: Standardisation background and systems of evaluation and authorisation for the European market. In Performance of Bio-Based Building Materials; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2017; pp. 593–610. [Google Scholar]

- USDA BioPreferred® Program. Available online: https://www.biopreferred.gov/BioPreferred/faces/pages/BiobasedProducts.xhtml (accessed on 9 March 2022).

- Falcone, P.M.; Imbert, E. Tackling Uncertainty in the Bio-Based Economy. Int. J. Stand. Res. 2019, 17, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morone, P.; Caferra, R.; D’Adamo, I.; Falcone, P.M.; Imbert, E.; Morone, A. Consumer willingness to pay for bio-based products: Do certifications matter? Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 240, 108248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).