How the Popularity of Short Videos Promotes Regional Endogeneity in Northwest China: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- The problems of rural development have been magnified in the explanatory framework of modernization. The development process of modernization has indeed led to risks faced by rural societies, but attributing the series of problems encountered in development, such as rural poverty, environmental pollution, gender inequality, and unequal educational resources, to the negative effects of modernization tends to create a dichotomy between development and “demodernization”.

- (2)

- The explanatory framework of modernization usually assumes that the endogenous, local knowledge of traditional villages gradually gives way to external knowledge in the modernization process, resulting in the lack of binding norms of action and the labeling of village residents as perpetrators of a crime and their exclusion from the power system of village governance [5,6]. Few studies have focused on the endogenous effects of returning labor on local rural development.

- (3)

- The view of modernity lags behind the current profound changes in the realistic foundations of rural society and theorizes inadequately the new social dynamic processes of change in the rural environment. The new era begins with the increasing rise of the networked society as a new social form on a global scale [7,8]. Networking has brought social systems closer. The state of local development is affected by “present” social dynamic processes but is also experiencing an increasing number of “absent” social dynamic processes from outside the local space [9].

2. Literature Review

2.1. Importance of Return Migration for Rural Endogeneity

2.2. Research on the Relationship between Popularity of Short Videos and Revival of Agricultural Culture in Rural China

2.3. Rural Media Practice and Youth Culture

2.4. Research Gap in Previous Study

3. Date and Methods

3.1. Theory

3.2. Data Collection

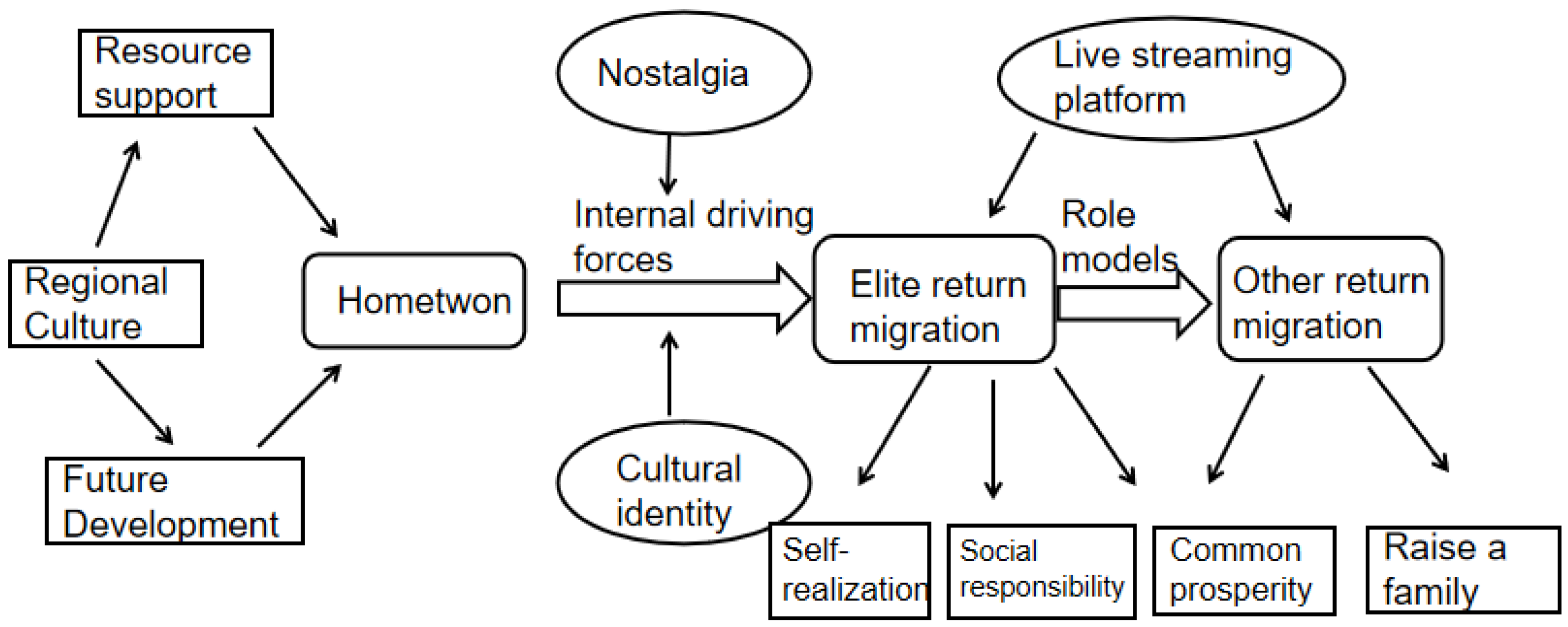

3.3. Data Analysis and Model Building

4. Findings and Discussion

4.1. Infrastructure Improvement

- “In the past, we didn’t have internet access here, and because of the high price of cell phones and Internet, we couldn’t afford to use them. Now the infrastructure is really improved, not only most households have the network, some public places such as libraries and parks also have public network.” (Mr. Niu)

- “When I was a teenager, it was impossible to access the Internet, and not many families in the village had computers. After graduating from high school, I worked in a factory and saved up money for two years before I bought my first smartphone. In the past two years, I can’t imagine that the government has installed internet for every household.” (Mr. Bai)

4.2. The Popularity of Short Videos

- “Everyone has started using smartphones in the past few years. Because smartphones are so much better and have more functions than previous ones, everyone enjoys using them and is curious about the outside world. We can get a lot of information and understand world events even without going out of this small village. It was at this time that short videos became popular, and people had fun watching others’ works, so they slowly started to try them.” (Ms. Liu)

- “I gave my mom a new smartphone, she can’t read or write, but she can’t stop watching TikTok and Kuaishou every day.” (Mr. Jiang)

- “We used to be isolated from the outside world. What rural people like, city people do not like; what city people like, we rural people also do not understand. With short videos, suddenly the outside world started to look at our small and closed world.” (Mr. Chen)

- “All of the people I know use TikTok and Kuaishou. Why do I need my phone if I don’t watch short videos? Watching short videos makes time pass quickly. My friends and I also communicate with each other through TikTok.” (Mr. Zhang K)

4.3. The Epidemic and the Return of Hometown

- “I was working in a factory doing furniture processing before. Later on, when the epidemic outbroke, the factory’s economic performance was not good, and it even faced closure. My elementary school classmate Mr. Zhao was already a small internet celebrity with more than 10,000 fans. He asked me to go back and work with him, so I simply quit my job and went back to my hometown.” (Wang said)

- “When the epidemic broke out suddenly, I was working in Wuhan and It feels like the sky is falling. So, I thought what’s the meaning of higher education. It’s more important to be with my family, so I took my wife and three-year-old son back to my hometown.” (Mr. Yang)

- “I had a stable job as an IT engineer in Shenzhen, and my income was not low. The epidemic was so terrible that I almost got infected. Because my colleague was hit somehow, as his close contacts, we were also quarantined, and those 14 days were too painful. Then, I thought it was better to go back to the countryside, earning less, but the pressure of life also less, and I can take care of parents. Besides, my parents have given me pressure to get married. These days they have introduced me several girls (laughs).” (Mr. Cheng)

- “I did not want to come back at first. I worked hard and got the Master’s Degree in order to get out of this remote place. However, my mother said every day that our former neighbor, Liu J, who had a PhD, had returned. I do think it is too difficult to buy a house in Shanghai where there are many masters and PhDs. I have nothing competitive, so I went back.” (Ms. Liu)

- “I was a model in Hangzhou, because of the epidemic, our company fell. Then, I opened a studio with a few friends to engage in short video live, which accumulated some fans. Then, I thought since the job is online, why I still had to rent such an expensive house in Hangzhou, so I went back to the countryside. After I came back, several people from my hometown also came back to join my studio.” (Miss Zhang G)

4.4. Government Support

- “The government’s support is very important. Just after I returned to my hometown, the village chief asked me to talk to him, affirming that I could come back to support my hometown with such a high degree as a doctor, and also giving me a lot of policy support, which laid the foundation for my entrepreneurship.” (Mr. Liu J)

- “We know that it is not easy for people to live due to the epidemic, so we often ask policy support from the higher government to address some real difficulties. In the past few years, there are more poverty alleviation projects, special allocations, tax deductions and other better specific measures. We hope people can actively look for diverse ways out.” (An interviewed official)

- “We can clearly feel central government’s attention to rural work in the past few years, and especially to the fight against poverty and the preservation of rural culture.” (An official interviewed)

4.5. Technology and Financial Support

- “I see others very successful and profitable, so I also want to do short video bloggers. However, at that time, I was worried that I did not have skills and talent in this area, and I was afraid that I would not do well. The main reason why I still took courage to do it later was that our community held a special training course, and it was free of charge. I thought I had nothing to lose anyway, so I signed up to learn. After learning, I had the confidence. If I hadn’t signed up, I guess I wouldn’t have had the confidence to do it.” (Mr. Sun)

- “We don’t have much money at home, and I’m relatively young, so it’s basically impossible to start a business on my own. Before that, I worked for two years in a factory. Then, I heard banks can offer small business loans, so I loaned some money to solve my business fund and started the live stream.” (Mr. Bai)

- “There was once a time when I was making hundreds of calls a day to people with college degrees or higher who were working in this field in Qingyang. Tell them about some entrepreneurial policies, technology promotion and financial support, to get some talents for a small city like ours. We’ve just taken off the hat of poverty, and we need talents.” (an interviewed official)

4.6. Emotional Factors

- “I find that viewers actually expect to see a different approach to life because people are generally feel stressed today, so they want to watch your videos to relax themselves. However, you can’t be too superficial and just play the clown to entertain people, it won’t be liked by the audience. I put a lot of emphasis on using humor to bring out the nostalgia of the audience, so that when they watch my work, they will think of their own lives or their parents’ lives in the past. Only then will the audience like it.” (Mr. Jia)

- “What makes my work successful, I think, is that it captures the collective memory of our generation’s traditional way of life. The clean sky, peaceful summer, cute animals, parents doing farm work, all these form a beautiful picture. The audience will be consciously taken into their own memories at a glance. I worked in city before and found that everyone was under a lot of pressure and had a very fond memory and imagination of the idyllic life in their leisure time.” (Ms. Liu F)

- “I have a PhD in the literature, and I would feel a little frustrated to start doing short videos, what does this have to do with my major? The number of my followers is not even as high as my elementary school classmates who graduate from high school. I have a habit of writing my own poetry. Sometimes I post videos of landscapes with poems I wrote, and I find that the number of hits and favorites goes up dramatically. After that, I started making subtitles for the videos myself, sometimes with ancient poems sometimes with their own poems, and then with the scenery of our hometown, to create short videos. Of course, recently, since some of my fans know that I am a doctor, more attention is paid to topics like how to raise rural children, and I may transform into an education blogger later (laughs).” (Mr. Liu J)

- “When I first started making short videos, my husband and relatives were against it, saying how I could be a woman making funny videos in front of the public that were not dignified in their opinion. However, I enjoyed it, especially because my performances could make people happy and many of my fans regularly watch me live every day.” (Ms. Xu)

4.7. Cultural Transmission

- “At the beginning, it was really difficult. No one watched the videos that we worked so hard to make. Then, our county held this agricultural culture exhibition, invited many successful netizens, and organized exchanges between them and us. After the exchange, I realized that it is not easy to make short videos like this, and there are many skills.” (Mr. Jiang)

- “My work mainly presents the oldest way of agricultural production we have here, because it is our most valuable cultural heritage. Its uniqueness lies in the fusion of agricultural production and artistic aesthetics. For example, our unique rituals here are intangible cultural heritage. When the viewers watching it, they learn about the rich cultural knowledge and meanwhile have a very beautiful spiritual enjoyment. That’s why live streaming is a very important form of cultural transmission.” (Mr. Wang)

- “It’s important to use the language of the camera. We are the descendants of the Yellow Emperor, so it’s important for us to understand the culture of this place to make live broadcasts with local characteristics.” (Miss Fang)

- “I didn’t like to study since I was a child (laughs), so now I can only sing and tell jokes in short videos. Many fans want me to talk about the cultural characteristics of Qingyang, but I don’t know and can’t express myself. If only the government could organize relevant training, I will definitely learn well this time.” (Zhang K)

4.8. Economic Benefits and Endogenetic Drive

- “I have returned to my hometown to do short videos for almost two years, and I think my income can almost support our family of three. This year I have earned about 15,000 EUR. Yes, I used to work outside to send money back every year, just a few tens of thousands, but now staying with my family makes us happier.” (Mr. Niu)

- “Sometimes more clicks can cash in on the traffic. You can bring goods; help sell agricultural products and other cultural products. These cooperation companies will also give us some pay. We feel that this live industry is dynamic, and we have confidence in the future.” (Mr. Wang)

- “Next month there are two other villagers back, a couple, also intend to live stream with me.” (Mr. Sun)

- “This is not only an interest of villagers, but rather of people working as a new industry to generate revenue. According to our statistics bureau, the income of many short video bloggers account for more than eighty percent of household income. Many of them are couples.” (An interview official)

- “Our government will formulate a series of policies and try our best to help the cultural industry of Qingyang City develop well.” (An interview official)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van der Ploeg, J.D.; Renting, H.; Brunori, G.; Knickel, K.; Mannion, J.; Marsden, T.; De Roest, K.; Sevilla-Guzmán, E.; Ventura, F. Rural development: From practices and policies towards theory. Sociol. Rural 2000, 40, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourqia, R.; Sili, M. New Paths of Development: Perspectives from the Global South; Sustainable Development Goals Series; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, D. Social Transformation and Environmental Issues in Contemporary China: A Preliminary Analytical Framework. Southeast Acad. 2000, 5, 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Y. Disembedded development: An explanatory framework for rural environmental problems. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. 2017, 3, 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. Environmental issues in the process of rural development. J. Jiangsu Adm. Coll. 2014, 2, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, A.J. From exogenous to endogenous pollution: The socio-cultural logic of water environment degradation in Taihu Lake Basin. Xuehai 2007, 1, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S. Postmodern Western Sociological Theory, 2nd ed.; Beijing University Press: Beijing, China, 2014; pp. 316–343. [Google Scholar]

- Catells, M. The Rise of the Network Society; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Y. Environmental mobility: An environmental sociological agenda in the age of globalization. Sociol. Rev. 2018, 1, 56–68. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics of TikTok. TikTok Releases First Data Report on Three Issues Relating to Rural Development, Rural Video Creators’ Income up 15 Times Year-on-Year. 2021. Available online: http://www.farmer.com.cn/2021/06/23/99872915.html (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Pottinger, R. Return Migration and Rural Industrial Employment: A Navajo Case Study. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderkamp, J. Return migration: Its significance and behavior. Econ. Inq. 1972, 10, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M. Success story? Japanese immigrant economic achievement and return migration, 1920–1930. J. Econ. Hist. 1995, 55, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orrenius, P.M. Return Migration from Mexico: Theory and Evidence; University of California: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tiemoko, R. Migration, return and socio-economic change in West Africa: The role of family. Popul. Space Place 2004, 10, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z. A review of theories on the return of migrant labor from abroad. Popul. Dev. 2013, 1, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Borjas, G.J.; Bratsberg, B. Who leaves? The outmigration of the foreign-born. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1994, 78, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. Causes and Consequences of Return Migration: Recent Evidence from China. J. Comp. Econ. 2002, 2, 376–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cui, C.; Zhao, Y. Working and Returning to the Hometown: Employment Transformation and Rural Development: A Study of Some Migrant Workers Moving to the City to Return to the Hometown and Start Their Own Business. Manag. World 2003, 7, 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, K. Work experience and career change and entrepreneurial participation. World Econ. 2009, 6, 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Kapur, D. Remittances: The new development mantra? In Proceedings of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), 1–21 April 2004; Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/gdsmdpbg2420045_en.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Ren, Z.; Zhou, Y. Will return migration lead to rural development? A review based on facts and literatures. J. Zhejiang Sci.-Tech. Univ. 2021, 46, 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Zhang, H. Rebuilding rural subjectivity with farmers’ organization: The foundation of rural revitalization in the new era. J. China Agric. Univ. 2018, 35, 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Li, Q. Research on the endogenous motivation of rural revitalization subjectivity and its stimulation path D. Source Environ. 2020, 34, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, M.; Wang, Y. Blockchain enabled journalism and the suppression of the right to be forgotten. Media Technol. China 2021, 11, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Xu, S.; Wu, W. How media logic is embedded in action—A study of short videos of returning youth. Contemp. Youth Stud. 2022, 376, 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Agricultural Research in Kuaishou. The 2021 Kuaishou Sannong Ecology Report; Kuaishou Co.: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.chinanews.com.cn/business/2021/01-21/9393018.shtml (accessed on 8 February 2022).

- Li, D. Short videos: Recording vivid scenes of rural revitalization. Financ. Times 2022, 3, 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Sha, Y. The disputed and the obscured: Rediscovering the subject of rural revitalization. Jianghuai Forum 2018, 6, 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Graue, M.E.; Walsh, D.J. Studying Children in Context: Theories, Methods, and Ethics; Sage: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, G. The same people in the same places? Socio-spatial identities and migration in youth. Sociology 1999, 33, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- White, B. Agriculture and the generation problem: Rural youth, employment and the future of farming. IDS Bull. 2012, 43, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burn, A.; Parker, D. Analysing Media Texts; Continuum International Publishing Group: New York City, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, S. Teaching Youth Media: A Critical Guide to Literacy, Video Production, & Social Change; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, P.; Green, B. Researching rural places: On social justice and rural education. Qual. Inq. 2013, 19, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Y. The endogenous perspective of rural cultural communication: The dilemma and the way out of “culture to the countryside”. Mod. Commun. J. Commun. Univ. China 2016, 6, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Pyles, D.G. Rural media literacy: Youth documentary videomaking as a rural literacy practice. J. Res. Rural Educ. 2016, 31, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y. Discussion on the dissemination of “vernacular video” in the era of self-media. Collection 2019, 7, 107–109. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y. Study on the influence of the new era of net popularity economy on college students’ consumption behavior. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 11, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. An analysis of the body narratives of peasant netizens’ short videos in the context of youth subculture. J. Res. Guide 2020, 12, 232–233. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Tan, C.K.K.; Yang, Y. Shehui Ren: Cultural production and rural youths’ use of the Kuaishou video-sharing app in Eastern China. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2020, 23, 1499–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grainge, P. Nostalgia and Style in Retro America: Moods, Modes, and Media recycling. J. Am. Comp. Cult. 2000, 23, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulding, C. Romancing the Past: Heritage Visiting and the Nostalgic Consumer. Psychol. Mark. 2001, 18, 565–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higson, A. Nostalgia is Not What It Used to be: Heritage Films, Nostalgia Websites and Contemporary consumers. Consum. Mark. Cult. 2014, 17, 120–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, M.; Keightley, E. The Modalities of Nostalgia. Curr. Sociol. 2006, 54, 919–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fred, D. Yearning for Yesterday: A Sociology of Nostalgia; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, X. Methodology of grounded theory research: Elements, research procedures and criteria for judging. Public Adm. Rev. 2008, 3, 23–43. [Google Scholar]

- The 5G Network Has Achieved Full Coverage in the Municipal Area of Qingyang. Qingyang Mob. 2020, 8, 27–32. Available online: https://www.163.com/dy/article/FKMHVR0105452FWK.html (accessed on 8 February 2022).

- Economic Performance of Qingyang City in 2021 and Outlook for 2022. Gansu Prov. Bur. Stat. 2022, 1, 14. Available online: http://tjj.gansu.gov.cn/tjj/c117494/202201/1954014.shtml (accessed on 8 February 2022).

- Cai, F. Demographic transition, demographic dividend and the Lewis turning point. Econ. Res. 2010, 45, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.-R. The Modernity of Localization and its Consequences. J. Fujian Norm. Univ. 2009, 5, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C. Beyond “hollowing out”: Urban-rural mobility in counties from the perspective of internal hairstyle development. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2021, 21, 91–100. [Google Scholar]

| Interviewee | Gender | Age | Education | Marital Status | Full Time/Part Time | Number of Followers (Thousand) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jiang | Male | 21 | High School | Single | Full time | 28 |

| Wang | Male | 26 | College | Married | Full time | 21 |

| Zhao | Male | 28 | Bachelor Degree | Married | Part time | 26 |

| Liu F | Female | 32 | Master Degree | Married | Full time | 122 |

| Zhang G | Female | 25 | College | Single | Part time | 28 |

| Cheng | Male | 30 | Master Degree | Divorced | Full time | 39 |

| Xu | Female | 29 | Bachelor Degree | Married | Full time | 29 |

| Chen | Male | 29 | Bachelor Degree | Single | Full time | 86 |

| Liu J | Male | 33 | Doctoral Degree | Married | Part time | 20 |

| Sheng | Female | 24 | College | Single | Full time | 37 |

| Niu | Male | 35 | Bachelor Degree | Married | Full time | 84 |

| Bai | Male | 22 | High School | Single | Full time | 28 |

| Zhang K | Male | 20 | High School | Single | Full time | 20 |

| Jia | Male | 26 | Bachelor Degree | Single | Part time | 21 |

| Fang | Female | 20 | High School | Single | Full time | 22 |

| Yang | Male | 29 | Master Degree | Married | Full time | 46 |

| Sun | Male | 27 | Bachelor Degree | Divorced | Full time | 51 |

| Main Category | Initial Category | Connotation of the Relationship |

|---|---|---|

| Resource support | Policy support Agricultural resources Platform support | Policy support from national and local governments combined with Qingyang’s own internal agricultural and cultural resources, as well as the multi-channel promotion and support of live streaming platforms triggered elements of resource support for the return of migrant labor. |

| Regional culture | Regional characteristics Cultural identity Brand certification | The distinctive regional culture, cultural identity and brand effect provide business opportunities and support for the return of labor. |

| Emotional belonging | Emotional resonance Raise a family | Traditional Chinese culture emphasizes filial piety. The emotional support of family and hometown is the eternal centripetal force for the return of labor. |

| Future development | Common prosperity Social responsibility Future confidence | The return to their hometowns is both a social responsibility and a confidence in their future development and common prosperity. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jia, C.; Zhang, J. How the Popularity of Short Videos Promotes Regional Endogeneity in Northwest China: A Qualitative Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3664. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063664

Jia C, Zhang J. How the Popularity of Short Videos Promotes Regional Endogeneity in Northwest China: A Qualitative Study. Sustainability. 2022; 14(6):3664. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063664

Chicago/Turabian StyleJia, Chao, and Jingting Zhang. 2022. "How the Popularity of Short Videos Promotes Regional Endogeneity in Northwest China: A Qualitative Study" Sustainability 14, no. 6: 3664. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063664

APA StyleJia, C., & Zhang, J. (2022). How the Popularity of Short Videos Promotes Regional Endogeneity in Northwest China: A Qualitative Study. Sustainability, 14(6), 3664. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063664