Abstract

Responsive educational proposals to develop skills to meet the demands of Industry 4.0 have become imperative to guarantee inclusive, equitable, and quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all, also reducing the negative impact of COVID-19 and the major post-pandemic social issues. This article analyzes which components of Education 4.0 have been considered in 21st century skills frameworks and identifies the teaching and learning methods and key stakeholders impacted. We conducted a systematic literature review (SLR) with research questions to highlight studies that address 21st century frameworks worldwide, identifying which teaching-–earning strategies contain 4.0 components, their learning dimensions, and the targeted stakeholders. The findings allowed us to identify opportunities to create or improve 21st century skills frameworks with the required Education 4.0 components to develop future skills. Our study revealed the absence of these frameworks for teachers and schools. Most are oriented toward students, developing competencies through the dimensions of character, meta-learning, and linking active learning teaching strategies. This work presents studies incorporating innovative educational practices and the core Education 4.0 components. It concludes with a reflection on creating educational models to develop complex-reasoning competencies and auto-systemic thinking to support problem-solving and address social needs.

1. Introduction

Improving the integral training of individuals and promoting quality of life in society should be the primary objectives of education. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 2020 report [1] of the United Nations (UN) Agenda 2030 highlights that the efforts to guarantee inclusive, equitable, and quality education and promote lifelong learning for all (SDG4) have been negatively impacted by the months of absence from school and universities due to COVID-19, impacting educational outcomes. Although many schools offer learning through virtual classrooms, internet access for many students is limited. Additionally, successful teaching depends on the computer literacy of teachers, educational managers, and parents.

The World Economic Forum’s 2021 report [2] describes the major post-pandemic social issues (e.g., extreme weather, deaths from infections, climate action failure, environmental damage, digital gap, cyber failures, lifestyles in crisis). It emphasizes that the gap between the “haves” and “have nots” will widen if access to technology and capacity remain inequitable. Although exemplary countries promote innovation, cooperation, and determination, most have struggled with crisis management during the global pandemic. Four critical response areas to the challenges wrought by COVID-19 are institutional authority, risk financing, information gathering and sharing, and resources and vaccines.

Integral educational framework models allow us to observe and evaluate the competencies required within each discipline from different dimensions, including technological, pedagogical, contextual, and humanistic aspects. The 21st century frameworks provide strategies to identify the skills that students must acquire to enter the future workforce; therefore, educators are tasked to analyze whether the current competencies and learning methods are designed to achieve this. The Partnership for 21st Century Skills [3] is a collaborative organization of governments and businesses that defined a framework for developing the skills, aptitudes, and attitudes to succeed in the workplace and 21st century society. It lists three types of competencies: (1) learning skills (creativity and innovation, critical thinking, and problem-solving; communication and collaboration); (2) literacy skills (information literacy; media literacy; ICT literacy), and (3) life skills (flexibility and adaptability; initiative and self-direction; social and intercultural skills; productivity and accountability; leadership and responsibility). Among the competencies that have become highly relevant today is the reasoning for complexity, where professionals must have the capacity to reflect how to address changing world [4]. Morin (1990) suggests the need to go beyond scientific reasoning into areas such as systems thinking and critical thinking [5], and creative thinking and scientific thinking [6] to develop new solutions to meet societal needs.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) is characterized by disruptive technologies, processes, and practices. For [7], the three most relevant technologies are artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), and algorithms. Incorporating these technologies requires updating educational systems, starting with the organization and management of the classroom, evaluation, pedagogy, ethics, and professional development; furthermore, the pandemic has raised other issues that require complex reasoning, communication, and remote global leadership skills.

To apply the components of Education 4.0, ref. [8] recommends going beyond developing thinking in the classroom to computational thinking using educational robotics and programming, developing students’ soft skills through emotional management, and creating moral dilemmas. Another reference is [9], which performs a systematic review of the correlation between 21st century competency frameworks and digital-competency frameworks. Their findings resulted in a model that integrates core competencies (e.g., information management, communication, collaboration, creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving) and contextual competencies (e.g., ethical awareness, cultural awareness, flexibility, self-direction, and lifelong learning) to ensure academic programs that foster core, contextual, and digital competencies within holistic educational frameworks. Noh et al., 2021 [10] showed that teachers’ design-thinking mindset to develop their students’ creative thinking and innovation skills for Education 4.0 included user-centered designing, empathy, collaboration, optimism, experimentation, prototyping, and mindfulness of process.

It is necessary to analyze the curricula holistically to balance the various objectives of education with the soft and technical competencies required for the 4.0 Industrial Revolution 4.0, thereby ensuring that students comprehensively identify their talents. Ref. [11] conducted a systematic literature review (SLR), focusing on studies related to 21st century skills and teaching, evaluation, assessment, learning sequences, and curriculum design. The authors compared the Education 4.0 components that demonstrate the need to rethink disruptive technology and hybrid-classroom strategies in the 21st century. The authors suggested that teacher training programs incorporate these skills in their curricula, and guidance should be provided to align technological, pedagogical, and disciplinary elements with new methodological approaches to develop 21st century skills among students. Identifying the necessary competencies for Education 4.0 training is a great way to increase the training potential. Other SLR studies have contributed to curriculum design and teacher training; they raise questions about how to assess the technological and pedagogical elements that would be the most appropriate to develop the skills.

This article focuses on analyzing which components of Education 4.0 have been considered in 21st century-skills frameworks and identifying the teaching and learning methods and key stakeholders being impacted. To achieve this, we first describe the dimensions to analyze the studies in this systematic review, discuss Education 4.0 within Industry 4.0, and describe the learning dimensions and teaching and learning methods. Second, we present the method for conducting this study’s systematic literature review (SLR) and the answers to the research questions. We end the discussion with the teaching and learning methods to develop 21st century competencies in Education 4.0 and some of the critical elements of innovative educational practices. The conclusion discusses post-pandemic challenges, the digital gap, and the future research needed to assess the technology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Context of the Study

This study mainly focuses on identifying which components of Education 4.0 are currently used in 21st century frameworks and which teaching and learning strategy is the most successful for developing future skills. The COVID-19 emergency context forced educators and educational institutions to rethink the future education scenarios. Singapore serves as a model to nations worldwide that want to prepare their workforce for the demands of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR). Its holistic educational system is renowned for preparing science, education, engineering, and math students (STEM) how to learn rather than what to learn [12]. Education 4.0 and the future of work are less concerned with what is known conceptually and theoretically than how it can be applied, not only the synthesis and application of knowledge and skills but also the integration of this synthesis with relevant new technologies [13]. The design and assessment of learning must be based on theories, models, techniques, standards, criteria, pedagogies, and components that improve educational quality without borders, places, and timeframes, supported by new teaching and learning methods mediated by technology.

2.2. Education 4.0 in Industry 4.0

Digital transformation and Education 4.0 differ from traditional education because they are enabled, supported, and guided by technology, including artificial intelligence, data management, ubiquitous technologies, robots, cloud computing, and sustainable technologies. A 2018 report by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) [14] identified that increased training in digital skills and Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) fields would be required, and soft skills not easily automated by machines, such as creativity and flexibility. Ref. [15] adopted a generic definition for Education 4.0 in higher education institutions as aligning their services and curricula to prepare the future Industry 4.0 workforce with technologies to address critical challenges such as student experience, the skills gap, data management, innovations in teaching and learning, metrics, open science, research, and cybersecurity.

Education 4.0 relies on digital strategies, digital security, and proper infrastructure. Ref. [16] organized the enablers of digital transformation in Education 4.0 into six categories: (1) technological enablers, (2) organizational enablers, (3) digital competency teaching, (4) soft skills learner, (5) hard skills learner, and (6) pedagogies. Learning analytics are a vital element of Education 4.0 to predict students’ future performance and sustain their continuous improvement [17]. Integrating Industry 4.0’s educational components is the beginning of a model constructed to make the various agents in the educational system more flexible, including pedagogical practices and the technology that supports learning. The integration includes connectivity and storage infrastructure, institutional guidelines, organizational processes, and practices to promote innovation and training of teachers in digital competencies (doing and being) so they have the skills of the digital-native learners.

These initiatives and projects should align with the needs and requirements of educational institutions to respond to current social contexts, considering the drivers of technological megatrends that lead to innovative solutions. Miranda et al., 2021 [18] propose four core components of Education 4.0., which we used to analyze the studies in this SLR (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Core components of Education 4.0 (based on Miranda et al., 2021 [18]).

The challenges of the future of education entail different perspectives: assessing the success of learning with digital media, determining the framework of student competencies, homogenizing the skills that teachers must have to meet the demands of a globalized and digitalized society, and incorporating emerging and disruptive technologies that help achieve the meaningful learning of students.

2.3. Learning Dimensions

Governmental public policies worldwide are reviewing and determining the job skills that individuals must possess to compete in globalized markets, such as massive data management, artificial intelligence, and robotics, while also considering the wellbeing and human development of workers. Ref. [19] mapped the soft skills needed for the new green jobs emerging from the research plans of governments, such as sustainable and connected mobility strategies, the modernization of public administration, the 5G roadmap, the new economy of care and wellness, the digitalization of the education system, among others. Ref. [20] points out that labor competencies depend on individuals’ emotions as a fundamental psychological component of skills developed for work. These complete the engine that generates actions. Thus, cognitive and emotional factors allow individuals to analyze their environment and make the best decisions [21]. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) [22], the new skills needed for employment are well served by a database of skills-jobs mismatch indicators comparable across countries and regularly updated, providing a comprehensive and detailed overview of skills shortages and surpluses across countries.

In this systematic literature review, we used the four-dimensions-of-learning model of the Center for Curriculum Redesign (CCR) [23], which are the knowledge, skills, character, and meta-learning dimensions, defined below:

- (1)

- Knowledge dimension: refers to teaching topics that constitute the traditional and modern disciplines important to many jurisdictions and cultures. Teachers, students, and curriculum designers can find innumerable ways to highlight the core subject areas. This dimension considers digital literacy, synthesis, and integration of design thinking, ethical mindset, information literacy, socio-environmental literacy, empathy, and shared responsibility. It includes global literacy, information culture, systems thinking, environmental culture, and digital culture.

- (2)

- Skills dimension: focuses on students developing skills through active roles in real-world situations that promote self-regulation, communication, and reflection, successfully transferring knowledge and learning to ever-changing situations. They are expected to develop creativity, critical thinking, communication, and collaboration competencies.

- (3)

- Character dimension: refers to character education to build the foundation for lifelong learning, supporting successful relationships in the home, community, and workplace, and developing personal values and virtues for sustainable participation in the globalized world. The competencies in this dimension include mindfulness, curiosity, courage, resilience, ethics, and leadership.

- (4)

- Meta-learning dimension: involves higher-level thinking processes, which control lower-level thinking and the internalization of a growth mindset. Learning-oriented students see mistakes as opportunities for growth and improvement, while performance-oriented learners see them as failures. This dimension features three verbalizations: verbalization of knowledge that is already verbal (such as remembering what happened in a story), verbalization of nonverbal knowledge (such as remembering how a Rubik’s cube was solved), and verbalization of the explanations of verbal or nonverbal knowledge.

The dimensions of learning seek to impact the design of competency-based curricula by integrating the four dimensions of learning into educational models since many frameworks do not cover all the dimensions of lifelong learning and “learning-to-learn” competencies.

2.4. Stakeholders in the Competency Frameworks of the 21st Century

The 21st century skills, knowledge, and attitudes are necessary for citizens to face the digital, sustainable, and social world ethically and humanistically. The Cedefop glossary of the European Commission [24] defines skill as the ability to perform tasks and solve problems. It points out that competency means applying learning outcomes in each context (education, work, personal, or professional development). Students, teachers, and school principals [25] are the main stakeholders in Education 4.0, each with different competency development perspectives. Collaborative and interactive learning environments for Generation Z students [26] require developing autonomous learning, creative thinking, problem-solving, critical thinking, communication, and collaboration skills. Refs. [27,28] suggest that, to address the digital divide issues, policymakers and educational institutes must undertake constructive educational reform in higher education curricula, especially in STEM programs with disruptive technologies, to incorporate the skills and competencies needed to deploy emerging technologies [12,14]. Therefore, school managers in Education 4.0 are expected to value and assess technologies and lead other school stakeholders to acquire technological skills to operate hybrid environments. Aligning education with the expectations of Industry 4.0 is possible when governments and educational institutions build adequate infrastructure to facilitate learning and learning networks that allow joint initiatives with society, thus reducing the digital gap.

New approaches to collaborative spaces, called FabLab or Makerspaces, promote various collaborative activities with different sectors. Two leading frameworks developed are DigiComp [29] and EntreComp [30,31] researched using focus groups in a makerspace to identify the competencies promoted in the DigiComp 2.1 and EntreComp frameworks. Their findings showed that students acquired planning skills, teamwork skills, public speaking, additive manufacturing skills, multidisciplinary thinking, and independent work skills. Partnering with Industry 4.0 requires considering all the educational actors and contemplating inclusive architectural spaces, learning strategies, and technology to solve problems efficiently in a society challenged by constant changes and uncertainty.

2.5. Teaching and Learning Methods

The new educational paradigms underpinning the 21st century frameworks aim to develop holistic competencies with integrated technological tools, thus requiring teaching–learning strategies to be effectively applied. The teaching–learning methods guide a logical, sequenced, and organized process to achieve objectives and evaluate learning, and the most appropriate technologies must be considered to accomplish this. Robotics is a new interdisciplinary teaching tool that offers the possibility of improving school performance, increasing motivation, and developing social skills, cooperative work, and creativity, among others [32]. The introduction of computational thinking refers to solving problems, designing systems, and understanding human behavior using the fundamental concepts of informatics [33]. Ramírez-Montoya, 2012 [34] presented five categories of active pedagogies focusing on teaching thinking skills, knowledge application, research practices, collaborative strategies, and the promotion of digital skills (see Table 2). We reviewed the studies selected for this SLR with this selection of categories.

Table 2.

Categories of active pedagogies (based on Ramírez-Montoya, 2012 [34]).

On the other hand, we must consider that we are evolving towards educational neurotechnology that proposes new ways of processing information in the human brain. A methodological change with pedagogical and technological intention is required in the educational model, embracing that the internet has changed producing, creating content, communicating, having fun, and processing information [31,35]. One of the crucial components for empowering teachers and students in these practices will play the role of the library, since the formation of proactive information culture strengthens an academic’s position in creating and use the information and by making them ready for digital transformation of the diverse approaches in the universities [36]. Providing access to information and knowledge databases to the academic community is a competitive advantage, but training should also be provided to know how to search, select, store and share information becomes a practice representative of a digitally literate society.

Implementing emerging technologies in the classroom learning methodologies reinforces learning in each educational stage. Scenarios with immersive technology such as augmented reality, contributes to a high level of presence and the simulation of realistic scenarios in a course [37]. On the other hand, the inclusion of Immersive Virtual Reality (IVR), associated with manipulative/experiential activities based on the STEM approach positively impacts the scientific-mathematical attitudes of participating students [38]. It´s not enough to have technology, its necessary to have pedagogical methodologies that favor learning.

Educational innovation is an evolution of teaching and learning methods and techniques, which are driven by new social, political, cultural and technological trends. University maker spaces provide and environment for collaborative learning and reinforce the teaching-learning process [39]. Suggestions to promote and enhance current creative education in STEM Maker education and meet the needs of students and teachers [40] recommend the development of new learning materials and online learning systems through the integration of product design and computer-aided design (CAD). Maker spaces generate possibilities to train the general public of any age in open innovation practices with technologies such as robots, electronics, 3D printers, research laboratories, so it is essential for governments and educational institutions to make available to the public such spaces.

From the perspective STEM education (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) the incorporation of the disciplines of behavioral sciences, humanities and art is demanded., in order to favor an integral education. An example is the theoretical model of Van den Hurk et al. (2019) [41] focuses on three types of factors that may affect persistence of learning in STEM: (1) environmental factors (e.g., the social context and social environment); (2) school-level factors (e.g., instruction, teachers, and pedagogy); and (3) student-level factors (e.g., students’ attitudes, motivation and aptitude). An other important aspect of STEM education is the design of STEM activities, for this design influences how the activities mediate students’ experiences in the STEM Classroom [42]. The sistematic review of Kayan-Fadlelmula, et al. (2022) [43] revealed an absence of research that explores enablers thay may enhance student participation in STEM-related fields of study and careers. The integration of diverse learning dimensions is a key to developing 21st century competencies and enabling Industry 4.0 requirements to face ambiguous and changing global scenarios.

2.6. Systematic Literature Review Method

To carry out the study, we used a systematic literature review (SLR) as a strategy to identify studies about frameworks created by various educational institutions, international bodies, and governments to develop 21st century competencies and analyze their potential to be incorporated in Education 4.0. SLRs are used to identify, evaluate, and interpret the data available within a period in each field of research. The process of this review is supported, in general terms, by the guidelines established by [44], focused on conducting SLRs in software engineering [38], and the contributions of [45,46,47]. The five phases of the review are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Systematic literature review process (own elaboration, based on Brereton, et al., 2007 [44]; Higgins & Green, 2006 [45]; Kitchenham, 2004 [46]; Chambers et al., 2009 [47]).

Phase 1. Research questions

During phase 1, eight questions were established to analyze the research published (unlimited until 2021). The questions were designed to cover the research’s objective and identify relevant and specific characteristics that could answer the questions shown in Table 3 [44,48].

Table 3.

Research questions (own elaboration).

Phase 2. Search process

The search process in the SCOPUS and WoS databases began with defining the keywords to use in their search engines with the AND operator, per the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The search was performed on September 4, 2021. The search string for both databases is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Keyword search.

Phase 3. Inclusion and extraction criteria

The search protocol and guidelines for selecting and evaluating relevant studies were developed as follows:

Search resources: Scopus database and Web of Science database.

Categories and keywords: (“Frameworks”), (“twenty-first century skills”).

Inclusion criteria: Period: Unlimited until 2021. Type of document: articles; Language: English.

Inclusion criteria: Conference and proceedings, papers, books; duplicate.

Phase 4. Data selection and extraction process

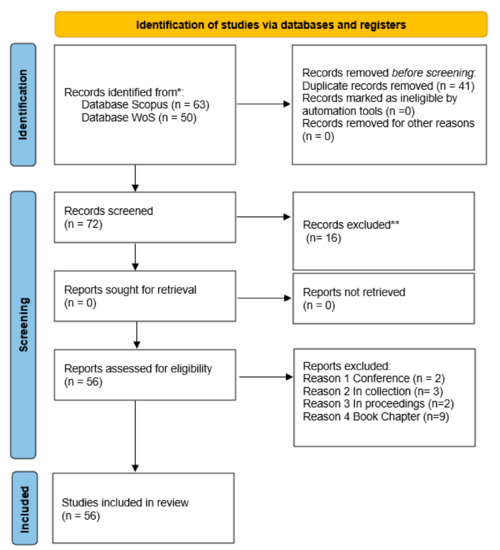

In phase 4, the articles were searched, then data extraction was performed. Subsequently, the information was input into an Excel database. The search resulted in 113 studies: 63 in Scopus and 50 in WoS. The information extracted from each article included the author(s), keywords, title, type of access, year of publication, name of publication, number of citations, DOI number, affiliations, language, country, and abstract. Based on these data, 41 duplicate articles were identified and moved to another database sheet, resulting in 72 articles. After the selection was applied according to the type of study, there were 56 articles as review candidates. Figure 2 shows the delimitation based on the PRISMA method [49].

Figure 2.

Selection process (PRISMA based on Page et al., 2021 [49]).

Phase 5. Data Synthesis

In phase 5, the classification sought to identify studies addressing twenty-first century frameworks in the WOS and SCOPUS databases and answer research questions RQ1, RQ2, RQ3, RQ4, and RQ5 described in Table 4. We sought to identify the teaching and learning strategies applied, the stakeholders, the learning dimensions, and their classification in the core of Education 4.0. The abstract’s information, keywords, and title were reviewed to categorize each article properly.

3. Results

The systematic literature review methodology results documented in an Excel database are available at the following address: https://zenodo.org/record/5574275 (accessed on 25 October 2021). This section presents the results related to the research questions. The tools used for the graphs were Excel and Tableau.

- RQ1.

- What were the articles’ objects of study?

The articles under study are presented in Table 5. The Id is the article identifier number for identification purposes in the following sections of this article. A summary of each article found is detailed below. These frameworks highlight educational models and learning strategies to develop future skills in educational institutions that align with the demands of Industry 4.0 (Appendix A).

Table 5.

Studies in the SLR.

These articles may be of interest to support training systems in different disciplines and academic degree programs that aim to develop future skills in students and provide solutions to social, health, climate change, digital divide, and complex thinking problems (Appendix A). They can also be the objects of analysis to integrate new possibilities for design curricula to strengthen formal, non-formal, and informal training and lifelong learning. Educational agencies, ministries of education, and companies with training components can find meanings from these works.

- RQ2.

- How many studies are in the Scopus and WoS databases over time and the dimension of learning targeted?

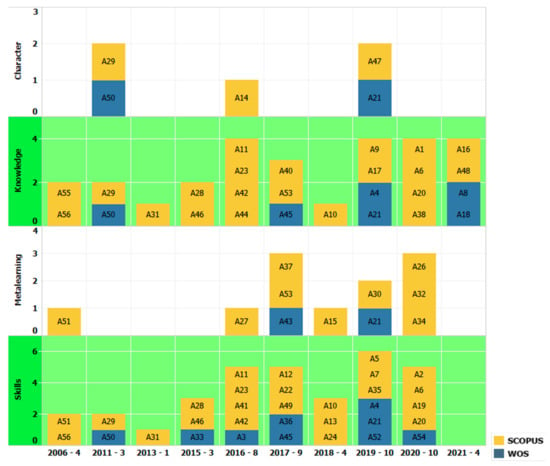

Figure 3 shows the learning dimensions, where it is reflected that 42% of the studies focused on developing the skills dimension. There, we found frameworks with titles such as Problem-solving in STEM (A2), Social Innovation Education (A41), Partnership for 21st Century Skills (A5, A24, A35, A52, A51, A29, A50), Entrepreneurial Projects (A31), Computational Thinking is a Problem-Solving Skillset (A12), ATC21S (A54), and Foster Creativity in an Inclusive Classroom (A19).

Figure 3.

Scopus and WoS databases over time and learning dimensions targeted.

In the knowledge dimension (36%), we found frameworks entitled Bridge21 (A20), Framework for Critical Online Reasoning (A6), Dell Initiatives (A56) and Microsoft (A55), STEAM Skills Development (A40), Design-led Education Innovation Matrix (A9), and Makers and Inventors (A9).

In the meta-learning dimension (15%), we found frameworks with titles such as Professional Learning Community (A27), TPACK (A32, A37, A43), Culturally Contextualizing the Multisensory Experience (A15), Pedagogies for Inclusion (A30), and Implicit Reasoning (A34).

Frameworks in the character dimension (7%) include Partnership for 21st Century Skills (A29, A14, A50) and Expectations of Religious Education (A47).

The Partnership for 21st Century Skills framework was classified into three learning dimensions: skills, knowledge, and character (not placing in meta-learning), so we consider it a good reference for application in institutions.

The data reflect that the first frameworks of 21st century competencies began to be addressed in 2006. Figure 3 is a graph where the X-axis represents the year the study was published and the number of studies found. The Y-axis represents the teaching and learning dimensions of the CCR, thus reflecting that the minimum number of studies focuses on applying the character and meta-learning dimensions. For educational practices, this analysis presents areas of opportunity for developing higher-level thinking processes in students, which control lower-level thinking. The idea is to internalize a growth mindset and engage students in lifelong learning to ensure sustainable participation in a global world and develop character with high personal values and virtues to achieve successful relationships [23].

- RQ3.

- What are the core Education 4.0 teaching and learning strategies applied in the study?

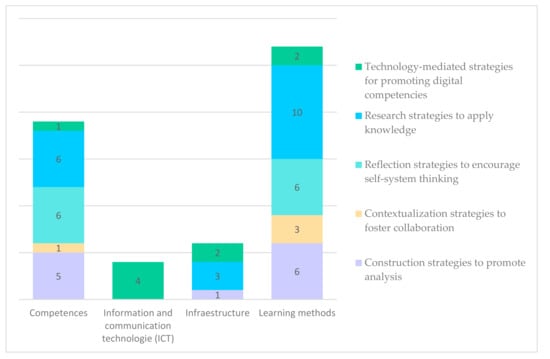

The most prevalent teaching and learning strategies that intersect with the core of Education 4.0 are presented in Figure 4 [18,34]. The most used were research strategies to apply knowledge with techniques such as research-based learning, project-based learning, and evidence-based educational innovation, followed by reflection strategies to encourage self-systemic thinking. The least used were contextual strategies to foster collaboration (A19, A39, A31, A38).

Figure 4.

Core Education 4.0 learning strategies.

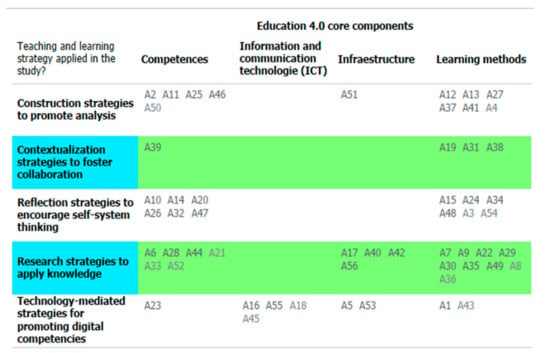

Figure 5 shows the study matrix with the article ID at the intersection of core Education 4.0 [18] and the teaching-and-learning-strategy classifications [34]. The figure highlights studies in information and communication technologies (ICT) with technology-mediated strategies to promote digital competencies (A16, A55, A18 and A45) and studies of the core infrastructure to support research strategies to apply knowledge (A17, A40, A42, A56). These stand out in the intersection.

Figure 5.

Learning strategy studies in the Education 4.0 core.

The data in Figure 4 and Figure 5 shed light on the educational practices where educational innovation is directed towards research strategies to apply knowledge. The techniques include research-based learning, project-based learning, and evidence-based educational innovation. The most significant gap worldwide reflects the need to conduct more research to implement and equip educational institutions’ technological infrastructure and integrate teaching and learning methods with technology.

- RQ4.

- Who are the stakeholders identified in the publications, and what core Education 4.0 competencies have been worked on in the frameworks?

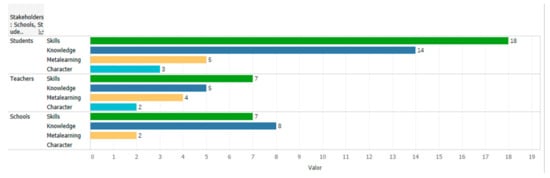

Figure 6 shows the learning dimensions of the Center for Curriculum Redesign (CCR) (Skills, Knowledge, Character, and Meta-learning). The most used are Skills (32 studies) and Knowledge (27 studies). The least are Meta-learning (11 studies) and Character (5 studies). Notably, the main stakeholders identified in the 21st century frameworks are students, ahead of teachers and training partners in industry and other sectors.

Figure 6.

Stakeholders and learning dimensions.

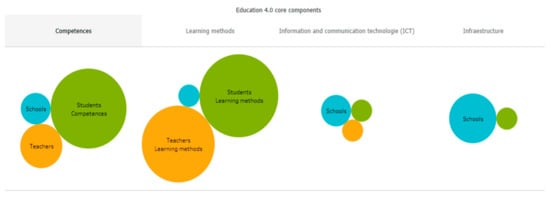

In contrast, Figure 7 highlights the finding of stakeholders (teachers, students, school managers) in the core components of Education 4.0 [4] to whom the frameworks were applied. The most significant number of studies focused on students. It is interesting to note the lack of studies on the Education 4.0 core components in infrastructure and information technologies (ICT).

Figure 7.

Stakeholders and Education 4.0.

Mapping competencies and stakeholders opens the perspective for cross-sectoral work. The academic, governmental, social, and business sectors have opportunities for competencies training, with excellent potential for intersecting linkages. The opportunities for training in curricular development, technologies, resources, and training programs stand out. In addition, there are implications for educational research in terms of following up on results, critical factors, and improvements that generate new knowledge, products, and services.

4. Discussion

This study presents the SCOPUS and WoS databases articles that refer to 21st century frameworks up to 2021. Table 5 shows 56 studies found with 21st century frameworks. In general, they highlight successful cases in educational practices. Some point out the teaching and learning strategies to trigger their students and teachers’ competencies and led to various educational institutions’ initiatives. The WEF 2021 report [2] presents the social problems during the global pandemic. The 2021 report of the 2030 Agenda [1] reveals that the efforts to achieve SDG 4 objectives have been negatively impacted by the months of students’ absence from school, hence the importance of incorporating educational scenarios that focus on developing skills demanded by the workforce of the future and Industry 4.0. Analyzing these studies reveals the gaps in formulating new competencies, learning methods, and frameworks by school managers and schools. Other gaps include developing competencies with digital technological tools necessary to address the primary post-pandemic social problems, raising awareness among governments and institutions of the gap between the “haves” and “have-nots.” Additionally, there is little research on the risks of continuing traditional teaching and learning methods and evolving to a 4.0 model.

To perform adequately in the changing world, citizens must manage various digital tools, be autonomous, take charge of their security and identity in social networks, and be responsible and ethical. Figure 3 reflects the minimal studies found in WoS and SCOPUS through 2021 that focus on the CCR character and meta-learning dimensions. Character education builds the foundation for lifelong learning, successful relationships in the home, community, workplace, and values development. Meta-learning involves higher-level thought processes, which control lower-level thoughts, and promotes the internalization of a growth mindset [23]. Study A28 presented a future skills instrument for students to choose the skills they consider most important. The most highly rated were social skills and collaboration. Boys appreciated technical skills, while the girls ranked social skills more highly. Refs. [20,21] point out that future jobs depend on cognitive and emotional factors that allow individuals to analyze their environments and make the best decisions. Ref. [8] exemplifies how educational robotics and programming can develop soft skills through emotional management and moral dilemmas. To teach character and meta-learning, trainers can design teaching and learning activities with reflection strategies to encourage systemic self-learning, contextual strategies to foster collaboration, research-based learning, project-based learning, and evidence-based educational innovations using information and communication technologies.

To guide good practices, institutions can build a repository of information for teachers with methodological guides on teaching–learning strategies and the technologies to be applied for their students on topics such as creativity, complex decision-making, data science, use of information technologies, and socio-emotional skills. Figure 4 shows that the teaching–learning strategies most used to develop Education 4.0 core competencies [18] are research strategies to apply knowledge and reflection strategies to promote self-learning (auto-systemic thinking) [34]. Figure 5 shows that fewer studies were found in the Education 4.0 infrastructure and ICT core components [18], highlighting a gap in the learning strategies that employ information and communication technologies and promote digital skills. One of the crucial components for empowering teachers and students in these practices will play the role of the library, since the formation of proactive information culture strengthens an academic’s position in creating and use the information [36]. Increasing academic performance and motivation [32] through creativity, collaboration, critical thinking, and communication [27] can challenge teachers who are not trained with new approaches.

The A51 study notes that teachers find it frustrating that schools do not have adequate resources to teach 21st century skills and suggests addressing the need for physical, technological, and policy infrastructures, curricular materials, and best practices for meaningful teaching and assessment. Scenarios with immersive technology [37] such the inclusion of Immersive Virtual Reality (IVR), associated with manipulative/experiential activities based on the STEM approach positively impacts the scientific-mathematical attitudes of participating students [38].Rethinking learning objectives to develop the four dimensions of learning (skills, knowledge, character, and meta-learning) infers that schools have equipment with an internet connection, access to digital libraries, cloud tools to create educational resources, and laboratories with robotics, augmented reality, and virtual reality practices. University maker spaces provide and environment for collaborative learning and reinforce the teaching-learning process [39]. Schools must have an educational model that uses quality assessments of learning and skills acquisition for Industry 4.0 and facilitates the harmonious interactions of people in a digital, globally connected world.

If an institution plans to incorporate an Education 4.0 framework, it should address skills development comprehensively (soft skills and hard skills) in students, teachers, and managers, and plan strategies to equip classrooms and provide relevant technological infrastructure and digital resources to teachers and stakeholders. Figure 6 shows that the frameworks found in our review focus on the learning dimensions, skills, and knowledge, and few focus on character and meta-learning. Figure 7 shows the lack of frameworks to support teachers and schools in preparing for Education 4.0 and Industry 4.0.

Along these lines, study A17 reported success in a primary school that used a makerspace, where multiple levels of interactions with various tools, activities, and contexts enabled computational thinking, computational decision making, and design-driven education. Suggestions to promote and enhance current creative education in STEM Maker education and meet the needs of students and teachers [40] recommend the development of new learning materials and online learning systems through the integration of product design and computer-aided design (CAD).

Study A40 described STEAM competencies developed in a robotics laboratory. Although it is expected to develop competencies in students, it is still necessary to create models that cater to teachers and school managers and provide the necessary resources to strengthen the educational institutions [25], such the theoretical model of Van den Hurk et al. (2019) [41] focuses on three types of factors that may affect persistence of learning in STEM: (1) environmental factors; (2) school-level factors; and (3) student-level factors. Schools must make better decisions to equip the learning environments of Generation Z students [26] with recreational, comfortable, sustainable, and accessible spaces [18]. An other important aspect of STEM education is the design of STEM activities, for this design influences how the activities mediate students’ experiences in the STEM Classroom [42]. Mechanisms can be established to implement constructive educational reforms in higher education curricula. Additionally, emphasis should be placed on building educational frameworks based on scientific development and ethics [50] to trigger the development of future skills for Industry 4.0 [14,15]. The frameworks should support financially sustainable models over time and deploy disruptive technologies, equip spaces to train teachers, parents, and educational managers, and evolve towards Education 4.0 in the shortest possible time.

5. Conclusions

Integrating the core 4.0 educational components with Industry 4.0 is the beginning of a model that involves the different stakeholders in the education system in flexible, pedagogical practices. This integration considers the technology that supports learning, connectivity, storage infrastructure, institutional guidelines, organizational processes, practices to promote innovation, digital skills training for teachers (doing and being), and coexistence with digital native students.

This article focused on analyzing which components of Education 4.0 are being used in 21st century frameworks and which teaching and learning strategy is the most successful for developing future skills. The data reveal (a) that literature on frameworks highlight case studies and teaching and learning strategies to develop 21st century skills; (b) the skills and knowledge learning dimensions have comprehensive studies, and there are areas of opportunity for studies on the development of character and meta-learning skills; (c) the most used teaching and learning strategies setting the trends for educational innovation are research strategies to apply knowledge and reflection and encourage auto-systemic thinking; (d) the components of Education 4.0 most addressed are learning methods and competencies; there is a lack of studies aimed at strengthening the infrastructure of schools and the use of ICT, and (e) there is a notable absence of frameworks aimed at teachers and managers and applying strategies to strengthen educational innovation in schools.

The implications for educational practice are to generate educational models and formal and informal educational practices that scale the development of 21st century competencies to a complex, changing world. It is essential to clearly understand the objectives and indicators of employment competencies to assess competency models worldwide, updating them periodically using research data from educational institutions. The social transformations brought about by the technological revolution in communications have directly impacted the way people act. The dynamics of Industry 4.0 in the present and the future present a reality that makes changes imperative for Education 4.0: Educational models must integrate artificial intelligence, data management, ubiquitous technologies, robots, and cloud computing to facilitate, among many other things, reducing the post-pandemic collateral damage of a world in complete technological change.

Reconstructing knowledge and the ways to apply it, not only in doing but also in perceiving, can serve as a starting point to generate the necessary changes to construct a sustainable development future in all disciplines of knowledge. Similarly, the implications of research results are to follow up with training that generates new knowledge, services, or products in 21st century education. Training in complex reasoning skills, with scientific, critical, creative, innovative, and systemic thinking, and developing habits for wellbeing, mental health, and interpersonal relationships will support training that leads to problem-solving and attention to social needs. Another educational challenge is to use disruptive and intelligent technologies that develop integrated soft and hard skills.

The value of this study was to identify trends in competencies for teachers, trainers, designers, researchers, and decision-makers interested in educational innovation. It invites further exploration of 21st century competency development and its possibilities.

Funding

This publication is a product of the project "OpenResearchLab: innovation with artificial intelligence and robotics to scale domain levels of reasoning for complexity” (ID Novus N21-207), funded by the Institute for the Future of Education, Tecnologico de Monterrey.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset presented in this study is openly available at https://zenodo.org/record/5574275 (accessed on 25 October 2021).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the technical support of WritingLab, Institute for the Future of Education, Tecnologico de Monterrey, Mexico, in the production of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

| Id | Reference APA |

| A1 | Tiemann, R. and Annaggar, A. (2020). A framework for the theory-driven design of digital learning environments (FDDLEs) using the example of problem-solving in chemistry education. Interactive Learning Environments, 1–14. |

| A2 | Priemer, B., Eilerts, K., Filler, A., Pinkwart, N., Rösken-Winter, B., Tiemann, R., and Zu Belzen, A. U. (2020). A framework to foster problem-solving in STEM and computing education. Research in Science & Technological Education, 38(1), 105–130. |

| A3 | Niemi, H., Nevgi, A., and Aksit, F. (2016). Active learning promoting student teachers’ professional competencies in Finland and Turkey. European Journal of Teacher Education, 39(4), 471–490. |

| A4 | Menekse, M., Purzer, S., and Heo, D. (2019). An investigation of verbal episodes that relate to individual and team performance in engineering student teams. International Journal of STEM Education, 6(1), 1–13. |

| A5 | Portman, D. and Broido, M. (2019). Apprenticing future economists: Analyzing an ESP course through the lens of the new CEFR extended framework. Language Learning in Higher Education, 9(2), 395–413. |

| A6 | Molerov, D., Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, O., Nagel, M. T., Brückner, S., Schmidt, S., and Shavelson, R. J. (2020). Assessing University Students’ Critical Online Reasoning Ability: A Conceptual and Assessment Framework with Preliminary Evidence. |

| A7 | Shavelson, R. J., Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, O., Beck, K., Schmidt, S., and Marino, J. P. (2019). Assessment of university students’ critical thinking: Next-generation performance assessment. International Journal of Testing, 19(4), 337–362. |

| A8 | Zgraggen, M. (2021). Blended learning model in a vocational educational training hospitality setting: from teachers’ perspectives. International Journal of Training Research, 1–27. |

| A9 | Wright, N. and Wrigley, C. (2019). Broadening design-led education horizons: Conceptual insights and future research directions. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 29(1), 1–23. |

| A10 | Mehrotra, S. and Mehrotra, V. S. (2018). Challenges Beyond Schooling: Innovative Models for Youth Skills Development in India. In Transitions to Post-School Life (pp. 13–34). Springer, Singapore. |

| A11 | Gretter, S. and Yadav, A. (2016). Computational thinking and media & information literacy: An integrated approach to teaching twenty-first century skills. TechTrends, 60(5), 510–516. |

| A12 | Yadav, A., Good, J., Voogt, J., and Fisser, P. (2017). Computational thinking as an emerging competence domain. In Competence-based vocational and professional education (pp. 1051–1067). Springer, Cham. |

| A13 | Hoogland, K. and Tout, D. (2018). Computer-based assessment of mathematics into the twenty-first century: pressures and tensions. ZDM, 50(4), 675–686. |

| A14 | Tan, L. (2016). Confucius: Philosopher of twenty-first century skills. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 48(12), 1233–1243. |

| A15 | Hodge, C. J. (2018). Decolonizing Collections-Based Learning: Experiential Observation as an Interdisciplinary Framework for Object Study. Museum Anthropology, 41(2), 142–158. |

| A16 | Hu, Y. and Spiro, R. J. (2021). Design for now, but with the future in mind: a “cognitive flexibility theory” perspective on online learning through the lens of MOOCs. Educational Technology Research and Development, 69(1), 373–378. |

| A17 | Laru, J., Vuopala, E., Iwata, M., Pitkänen, K., Sanchez, I., Mäntymäki, A., … and Näykki, J. (2019). Designing seamless learning activities for school visitors in the context of Fab Lab Oulu. In Seamless Learning (pp. 153–169). Springer, Singapore. |

| A18 | Moya, S. and Camacho, M. (2021). Developing a Framework for Mobile Learning Adoption and Sustainable Development. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 1–18. |

| A19 | Eddles-Hirsch, K., Kennedy-Clark, S., and Francis, T. (2020). Developing creativity through authentic programming in the inclusive classroom. Education 3–13, 48(8), 909–918. |

| A20 | Sullivan, K., Bray, A., and Tangney, B. (2020). Developing twenty-first century skills in out-of-school education: the Bridge21 Transition Year programme. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 1–17. |

| A21 | Javed, M. S., Athar, M. R., and Saboor, A. (2019). Development of a twenty-first century skills scale for Agri varsities. Cogent Business & Management, 6(1), 1692485. |

| A22 | Butler, D., Leahy, M., Hallissy, M., and Brown, M. (2017). Different strokes for different folks: Scaling a blended model of teacher professional learning. Interactive Technology and Smart Education. |

| A23 | Niemi, H. and Multisilta, J. (2016). Digital storytelling promoting twenty-first century skills and student engagement. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 25(4), 451–468. |

| A24 | Kusumoto, Y. (2018). Enhancing critical thinking through active learning. Language Learning in Higher Education, 8(1), 45–63. |

| A25 | Kay, K., and Honey, M. (2006). Establishing the R&D agenda for twenty-first century learning. New Directions for Youth Development, (110), 63–80. |

| A26 | Reichert, F., Zhang, D. J., Law, N. W., Wong, G. K., and de la Torre, J. (2020). Exploring the structure of digital literacy competence assessed using authentic software applications. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(6), 2991–3013. |

| A27 | Salleh, H. (2016). Facilitation for professional learning community conversations in Singapore. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 36(2), 285–300. |

| A28 | Ahonen, A. K., and Kinnunen, P. (2015). How do students value the importance of twenty-first century skills? Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 59(4), 395–412. |

| A29 | Arati, D., Todorova, A., and Merrett, R. (2011). Implementation and sustainability of a global ICT company’s programme to help teachers integrate technology into learning and teaching in Germany, France, and the UK. Research in Learning Technology, 19. |

| A30 | Herodotou, C., Sharples, M., Gaved, M., Kukulska-Hulme, A., Rienties, B., Scanlon, E., and Whitelock, D. (2019). Innovative pedagogies of the future: An evidence-based selection. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 4, p. 113). Frontiers. |

| A31 | Izzrech, K., Del Giudice, M., and Della Peruta, M. R. (2013). Investigating entrepreneurship among Algerian youth: Is it a knowledge-intensive factory? Journal of the knowledge economy, 4(3), 319–329. |

| A32 | Başaran, B. (2020). Investigating science and mathematics teacher candidate’s perceptions of TPACK-21 based on 21st century skills. Ilkogretim Online, 19(4). |

| A33 | Gold, A. U., Oonk, D. J., Smith, L., Boykoff, M. T., Osnes, B., and Sullivan, S. B. (2015). A lens on climate change: Making climate meaningful through student-produced videos. Journal of Geography, 114(6), 235–246. |

| A34 | Bronkhorst, H., Roorda, G., Suhre, C., and Goedhart, M. (2020). Logical reasoning in formal and everyday reasoning tasks. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 18(8), 1673–1694. |

| A35 | Doorman, M., Bos, R., de Haan, D., Jonker, V., Mol, A., and Wijers, M. (2019). Making and implementing a mathematics day challenge as a makerspace for teams of students. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 17(1), 149–165. |

| A36 | Häkkinen, P., Järvelä, S., Mäkitalo-Siegl, K., Ahonen, A., Näykki, P., and Valtonen, T. (2017). Preparing teacher-students for twenty-first century learning practices (PREP 21): a framework for enhancing collaborative problem-solving and strategic learning skills. Teachers and Teaching, 23(1), 25–41. |

| A37 | Cherner, T. and Smith, D. (2017). Reconceptualizing TPACK to meet the needs of twenty-first century education. The New Educator, 13(4), 329–349. |

| A38 | Kickbusch, S., Wright, N., Sternberg, J., and Dawes, L. (2020). Rethinking learning design: Reconceptualizing the role of the learning designer in pre-service teacher preparation through a design-led approach. International Journal of Design Education, 14(4), 29–45. |

| A39 | Lee, C. S., and Kolodner, J. L. (2011). Scaffolding students’ development of creative design skills: A curriculum reference model. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 14(1), 3–15. |

| A40 | Smyrnova-Trybulska, E., Morze, N., Kommers, P., Zuziak, W., and Gladun, M. (2017). Selected aspects and conditions of the use of robots in STEM education for young learners as viewed by teachers and students. Interactive Technology and Smart Education. |

| A41 | Alden-Rivers, B. (2016). Social innovation education: Designing learning for an uncertain world. In Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Education. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. |

| A42 | Kitchens, R. K., and Barker, M. E. (2016). Synthesizing pedagogies and engaging students: Creating blended eLearning strategies for library research and writing instruction. The Reference Librarian, 57(4), 323–335. |

| A43 | Hannaway, D. M., and Steyn, M. G. (2017). Teachers’ experiences of technology-based teaching and learning in the Foundation Phase. Early Child Development and Care, 187(11), 1745–1759. |

| A44 | Blau, I., Peled, Y., and Nusan, A. (2016). Technological, pedagogical and content knowledge in one-to-one classroom: teachers developing “digital wisdom”. Interactive Learning Environments, 24(6), 1215–1230. |

| A45 | Weninger, C. (2017). The “vernacularization” of global education policy: media and digital literacy as twenty-first century skills in Singapore. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 37(4), 500–516. |

| A46 | Lin, T. B., Mokhtar, I. A., and Wang, L. Y. (2015). The construct of media and information literacy in Singapore education system: global trends and local policies. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 35(4), 423–437. |

| A47 | Viinikka, K.-, and Ubani, M. (2019). The expectations of Finnish RE student teachers of their professional development in their academic studies in the light of twenty-first century skills. Journal of Beliefs & Values, 40(4), 447–463. |

| A48 | Gupta, R. (2021). The Role of Pedagogy in Developing Life Skills. Margin: The Journal of Applied Economic Research, 15(1), 50–72. |

| A49 | Valtonen, T., Sointu, E., Kukkonen, J., Kontkanen, S., Lambert, M. C., and Mäkitalo-Siegl, K. (2017). TPACK updated to measure pre-service teachers’ twenty-first century skills. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 33(3). |

| A50 | Snape, P., and Fox-Turnbull, W. (2011). Twenty-first century learning and technology education nexus. Problems of Education in the 21st Century, 34, 149. |

| A51 | Wilson, J. I. (2006). Twenty-first century learning for teachers: helping educators bring new skills into the classroom. New Directions for Youth Development, (110), 149–154. Doi: 10.1002/yd.175 |

| A52 | Engerman, J. A., Carr-Chellman, A. A., and MacAllan, M. (2019). Understanding learning in video games: A phenomenological approach to unpacking boy cultures in virtual worlds. Education and Information Technologies, 24(6), 3311–3327. |

| A53 | Sahlin, J. S., Tsertsidis, A., and Islam, M. S. (2017). Usages and impacts of the integration of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in elementary classrooms: a case study of Swedish municipality schools. Interactive Learning Environments, 25(5), 561–579. |

| A54 | Lipiäinen, T., Ubani, M., Viinikka, K., and Kallioniemi, A. (2020). What does “new learning” require from religious education teachers? A study of Finnish RE teachers’ perceptions. Journal of Religious Education, 68(2), 213–231. |

| A55 | Knox, A. (2006). Why American business demands twenty-first century learning: A company perspective. New Directions for Youth Development, (110), 31–7. |

| A56 | Bruett, K. (2006). Why American business demands twenty-first century skills: an industry perspective. New directions for youth development, (110), 25–30. |

References

- UN. The Sustainable Development Goals Report. 2020. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2020/ (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- McLennan, M. The Global Risks Report. 2021 16th Edition. Available online: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_The_Global_Risks_Report_2021.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Partnership for 21st Century Skills. Framework for 21st Century Learning. 2019. Available online: https://bit.ly/3FS9JBC (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- Tecnologico de Monterrey. Razonamiento para la Complejidad. In Tecnologico de Monterrey, 7 Competencias con las que el Tec Busca Preparar a sus Estudiantes; 2019; Available online: https://bit.ly/3AsM6NL (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- Morin, E.; Pakman, M. Introducción al Pensamiento Complejo; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2011; ISBN 978-84-7432-518-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Montoya, M.S.; Álvarez-Icaza, I.; Sanabria-Zepeda, J.C.; López-Caudana, E.O.; Alonso, P.E.; Miranda, J. Scaling Complex Thinking for Everyone through Open Science: A Conceptual Methodological Framework. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing Multiculturality TEEM21, Barcelona, Spain, 26–29 October 2021; University of Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2021; pp. 806–811. [Google Scholar]

- Chaka, C. Skills, Competencies and Literacies Attributed to 4IR/Industry 4.0: Scoping Review. IFLA J. 2020, 46, 369–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álamo Venegas, J.J.; Alonso Díaz, L.; Yuste Tosina, R.; López Ramos, V.M. La Dimensión Educativa de la robótica: Del Desarrollo del Pensamiento al Pensamiento Computacional en el aula. Campo Abierto. Rev. de Educ. 2021, 40, 2. Available online: https://bit.ly/3jbxUkG (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- van Laar, E.; van Deursen, A.J.A.M.; van Dijk, J.A.G.M.; de Haan, J. The Relation between 21st-Century Skills and Digital Skills: A Systematic Literature Review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 72, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, S.C.; Karim, A.M.A. Design Thinking Mindset to Enhance Education 4.0 Competitiveness in Malaysia. IJERE 2021, 10, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Salamanca, J.C.; Agudelo, O.L.; Salinas, J. Key Competencies, Education for Sustainable Development and Strategies for the Development of 21st Century Skills. A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleason, N.W. (Ed.) Higher Education in the Era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution; Springer: Singapore, 2018; ISBN 9789811301933. Available online: https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/23279 (accessed on 16 September 2021).

- Hong, C.; Ma, W.W.K. (Eds.) Introduction: Education 4.0: Applied Degree Education and the Future of Work. In Applied Degree Education and the Future of Work; Lecture Notes in Educational Technology; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 1–13. ISBN 9789811531415. [Google Scholar]

- PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC). Will Robots Really Steal Our Jobs? An International Analysis of the Potential Long-Term Impact of Automation 2018. Available online: https://www.pwc.co.uk/economic-services/assets/international-impact-of-automation-feb-2018.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- Bonfield, C.A.; Salter, M.; Longmuir, A.; Benson, M.; Adachi, C. Transformation or Evolution? Education 4.0, Teaching and Learning in the Digital Age. High. Educ. Pedagog. 2020, 5, 223–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlos de Sousa Oliveira, K.; André Cavalcante de Souza, R. Habilitadores Da Transformação Digital Em Direção à Educação 4.0. Renote 2020, 18, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciolacu, M.; Tehrani, A.F.; Beer, R.; Popp, H. Education 4.0—Fostering Student’s Performance with Machine Learning Methods. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 23rd International Symposium for Design and Technology in Electronic Packaging (SIITME), Constanta, Romania, 26–29 October 2017; pp. 438–443. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, J.; Navarrete, C.; Noguez, J.; Molina-Espinosa, J.-M.; Ramírez-Montoya, M.-S.; Navarro-Tuch, S.A.; Bustamante-Bello, M.-R.; Rosas-Fernández, J.-B.; Molina, A. The Core Components of Education 4.0 in Higher Education: Three Case Studies in Engineering Education. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2021, 93, 107278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Vaquero, M.; Sánchez-Bayón, A.; Lominchar, J. European Green Deal and Recovery Plan: Green Jobs, Skills and Wellbeing Economics in Spain. Energies 2021, 14, 4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alles, M.A. Desarrollo del Talento Humano Basado en Competencias; Ediciones Granica SA: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Duque Ceballos, J.L.; García Solarte, M.; Hurtado Ayala, A. Influencia de la inteligencia emocional sobre las competencias laborales: Un estudio empírico con empleados del nivel administrativo. Estud. Gerenc. 2017, 33, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OCDE. The Future of Education and Skills. Education 2030. 2018. Available online: http://go.uv.es/1fDpQnn (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- Fadel, C.; Bialik, M.; Trilling, B.; Schleicher, A. Four-Dimensional Education: The Competencies Learners Need to Succeed; Center for Curriculum Redesign: Boston, MA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-5186-4256-2. [Google Scholar]

- Cedefop. Annual Report 2014; Cedefop Information Series; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2015; Available online: https://bit.ly/3AOReKz (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Himmetoglu, B.; Aydug, D.; Bayrak, C. Education 4.0: Defining the teacher, the student, and the school manager aspects of the revolution. Turk. Online J. Distance Educ. 2020, 21, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz Hussin, A. Education 4.0 Made Simple: Ideas For Teaching. IJELS 2018, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, G. May 4 Be with You: Creating Education 4.0. J. Learn. Dev. 2019, 6, 95–115. Available online: https://bit.ly/3aKxXiX (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Shirazi, F.; Hajli, N. IT-Enabled Sustainable Innovation and the Global Digital Divides. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A. DIGCOMP: A Framework for Developing and Understanding Digital Competence in Europe. 2013. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/yc9at8t6 (accessed on 5 April 2021).

- Bacigalupo, M. Entrepreneurship as a competence. In World Encyclopedia of Entrepreneurship; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rayna, T.; Striukova, L. Fostering Skills for the 21st Century: The Role of Fab Labs and Makerspaces. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 164, 120391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivas-Fernandez, L.; Sáez-López, J.M. Integración de la robótica educativa en Educación Primaria. Rev. Latinoam. De Tecnol. Educ.-RELATEC 2019, 18, 107–129. [Google Scholar]

- Wing, J.M. Computational thinking. Commun. ACM 2006, 49, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Montoya, M.S. Modelos y Estrategias de Enseñanza para Ambientes Innovadores; Editorial Digital: Monterrey, México, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pradas Montilla, S. La Neurotecnología Educativa. Claves Del Uso de La Tecnología En El Proceso de Aprendizaje. ReiDoCrea Rev. Electrónica De Investig. Docencia Creat. 2017, 6, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deja, M.; Rak, D.; Bell, B. Digital Transformation Readiness: Perspectives on Academia and Library Outcomes in Information Literacy. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2021, 47, 102403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seufert, C.; Oberdörfer, S.; Roth, A.; Grafe, S.; Lugrin, J.-L.; Latoschik, M.E. Classroom Management Competency Enhancement for Student Teachers Using a Fully Immersive Virtual Classroom. Comput. Educ. 2022, 179, 104410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Díaz, F.; Carrillo-Rosúa, J.; Fernández-Plaza, J.A. Uso de Tecnologías Inmersivas y Su Impacto En Las Actitudes Científico-Matemáticas Del Estudiantado de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria En Un Contexto En Riesgo de Exclusión Social. Educar 2021, 57, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.F.; Barber III, D.; Harris, M.; Haymore, J. What Can Universities Learn From Organizational Creative Space Design Research? A Look at Maker Spaces. JHETP 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.; Shih, Y. Enhance STEM Education by Integrating Product Design with Computer-Aided Design Approaches. CADandA 2021, 19, 694–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Hurk, A.; Meelissen, M.; van Langen, A. Interventions in Education to Prevent STEM Pipeline Leakage. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2019, 41, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daher, W.; Awawdeh Shahbari, J. Design of STEM Activities: Experiences and Perceptions of Prospective Secondary School Teachers. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2020, 15, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kayan-Fadlelmula, F.; Sellami, A.; Abdelkader, N.; Umer, S. A Systematic Review of STEM Education Research in the GCC Countries: Trends, Gaps and Barriers. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2022, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brereton, P.; Kitchenham, B.A.; Budgen, D.; Turner, M.; Khalil, M. Lessons from Applying the Systematic Literature Review Process within the Software Engineering Domain. J. Syst. Softw. 2007, 80, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Higgins, J.P.; Green, S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions 4.2.6. Cochrane Libr. 2006, 4, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchenham, B. Procedures for Performing Systematic Reviews; Keele University: Keele, UK, 2004; Volume 33, pp. 1–26. Available online: https://bit.ly/2XnwE6y (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Chambers, D.; Rodgers, M.; Golder, S.; Pepper, C.; Todd, D.; Woolacott, N. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. 2009. Available online: https://bit.ly/3FSM9oe (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- García-Peñalvo, F.J. Mapeos Sistemáticos de Literatura, Revisiones Sistemáticas de Literatura y Benchmarking de Programas Formativos. 2017. Available online: http://repositorio.grial.eu/handle/grial/1056 (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifaki, E.; Petousi, V. Contextualising Harm in the Framework of Research Misconduct. Findings from Discourse Analysis of Scientific Publications. IJSD 2020, 23, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).