The Effect of Proactive Personality on Creativity: The Mediating Role of Feedback-Seeking Behavior

Abstract

:1. Introduction

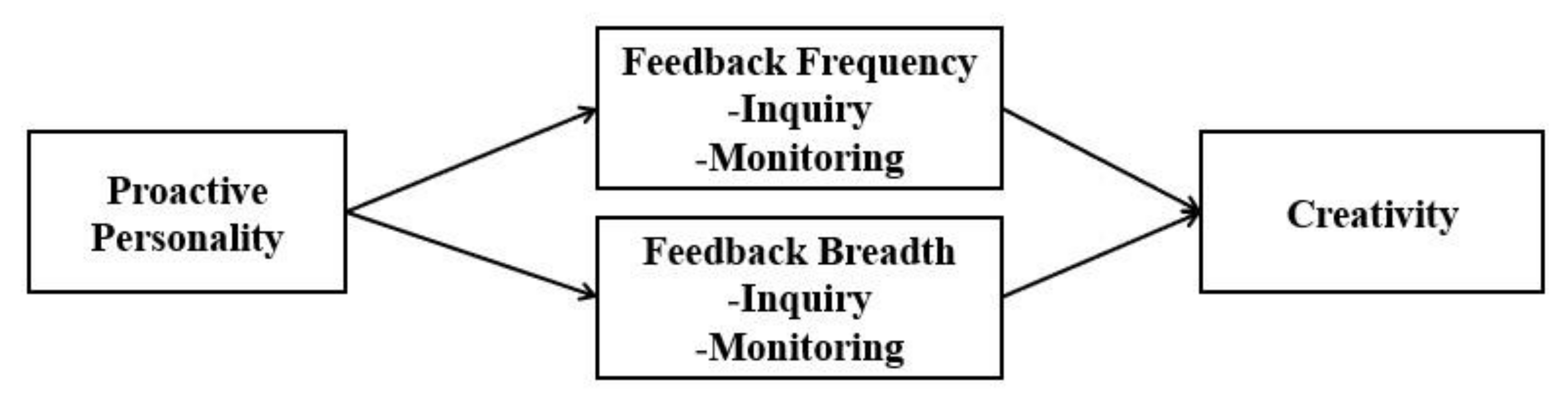

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. The Proactive Personality and Creativity

2.2. The Proactive Personality and Feedback-Seeking

2.3. The Mediating Role of Feedback Frequency

2.4. The Mediating Role of Feedback Breadth

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Samples

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Proactive Personality

3.2.2. Frequency of Feedback Inquiry and Monitoring

3.2.3. Breadth of Feedback-Seeking Inquiry and Monitoring

3.2.4. Creativity

3.2.5. Control Variables

3.3. Analytical Strategy

4. Results

4.1. Validity and Reliability Analysis

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

4.3. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Overall Findings

5.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crant, J.M. Proactive behavior in organizations. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 435–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, D.M.; Schroeder, T.D.; Martinez, H.A. Proactive personality at work: Seeing more to do and doing more? J. Bus. Psychol. 2014, 29, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, S.E.; Crant, J.M.; Kraimer, M.L. Proactive personality and career success. J. Appl. Psychol. 1999, 84, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frese, M.; Kring, W.; Soose, A.; Zempel, J. Personal initiative at work: Differences between East and West Germany. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 37–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, T.S.; Crant, J.M. The proactive component of organizational behavior: A measure and correlates. J. Organ. Behav. 1993, 14, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crant, J.M. The Proactive Personality Scale and objective job performance among real estate agents. J. Appl. Psychol. 1995, 80, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Li, W.-D.; Li, Y.; Liden, R.C.; Li, S.; Zhang, X. Unintended consequences of being proactive? Linking proactive personality to coworker envy, helping, and undermining, and the moderating role of prosocial motivation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 106, 250–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Williams, H.M.; Turner, N. Modeling the antecedents of proactive behavior at work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 636–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fuller, B.J.; Marler, L.E. Change driven by nature: A meta-analytic review of the proactive personality literature. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 75, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-Y.; Hon, A.H.Y.; Crant, J.M. Proactive personality, employee creativity, and newcomer outcomes: A longitudinal study. J. Bus. Psychol. 2009, 24, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-Y.; Hon, A.H.Y.; Lee, D.-R. Proactive personality and employee creativity: The effects of job creativity requirement and supervisor support for creativity. Creat. Res. J. 2011, 22, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crant, J.M.; Bateman, T.S. The central role of proactive behavior in Organizations. In Proceedings of the 2004 Academy of Management Annual Meeting, New Orleans, LA, USA, 6–11 August 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.H.; Fang, Y.; Qureshi, I.; Janseen, O. Understanding employee innovative behavior: Integrating the social network and leader–member exchange perspectives. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Liang, J.; Crant, J.M. The role of proactive personality in job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behavior: A relational perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gong, Y.; Cheung, S.Y.; Wang, M.; Huang, J.C. Unfolding the proactive process for creativity: Integration of the employee proactivity, information exchange, and psychological safety perspectives. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 38, 1611–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anseel, F.; Beatty, A.S.; Shen, W.; Lievens, F.; Sackett, P.R. How are we doing after 30 years? A meta-analytic review of the antecedents and outcomes of feedback-seeking behavior. J. Manag. 2015, 41, 318–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parker, S.K.; Collins, C.G. Taking stock: Integrating and differentiating multiple proactive behaviors. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 633–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ashford, S.J.; Black, J.S. Proactivity during organizational entry: The role of desire for control. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashford, S.J.; De Stobbeleir, K.; Nujella, M. To seek or not to seek: Is that the only question? Recent developments in feedback-seeking literature. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2016, 3, 213–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancouver, J.B.; Morrison, E.W. Feedback inquiry: The effect of source attributes and individual differences. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1995, 62, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijbom, R.B.L.; Anseel, F.; Crommelinck, M.; De Beuckelaer, A.; De Stobbeleir, K.E.M. Why seeking feedback from diverse sources may not be sufficient for stimulating creativity: The role of performance dynamism and creative time pressure. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, J.B.; Marler, L.E.; Hester, K. Promoting felt responsibility for constructive change and proactive behavior: Exploring aspects of an elaborated model of work design. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 1089–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Ashford, S.J. The Dynamics of Proactivity at Work. Res. Organ. Behav. 2008, 28, 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; George, J.M. When job dissatisfaction leads to creativity: Encouraging the expression of voice. Acad. Manage. J. 2001, 44, 682–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seibert, S.E.; Kraimer, M.L.; Crant, J.M. What do proactive people do? A longitudinal model linking proactive personality and career success. Pers. Psychol. 2001, 54, 845–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashford, S.J.; Blatt, R.; VandeWalle, D. Reflections on the looking glass: A review of research on feedback-seeking behavior in organizations. J. Manag. 2003, 29, 769–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashford, S.J.; Cummings, L.L. Feedback as an individual resource: Personal strategies of creating information. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1983, 32, 370–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, S.Y.; Rhee, Y.W.; Lee, J.E.; Choi, J.N. Dual pathways of emotional competence towards incremental and radical creativity: Resource caravans through feedback-seeking frequency and breadth. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2020, 29, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, P.E.; Cober, R.T.; Miller, T. The effect of transformational and transactional leadership perceptions on feedback-seeking intentions. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 1703–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Stobbeleir, K.E.; Ashford, S.J.; Buyens, D. Self-regulation of creativity at work: The role of feedback-seeking behavior in creative performance. Acad. Manage. J. 2011, 54, 811–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chae, H.; Choi, J.N. Contextualizing the effects of job complexity on creativity and task performance: Extending job design theory with social and contextual contingencies. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2018, 91, 316–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, S.Y.; Antefelt, A.; Choi, J.N. Dual effects of job complexity on proactive and responsive creativity: Moderating role of employee ambiguity tolerance. Group Organ. Manag. 2017, 42, 388–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N.; Potočnik, K.; Zhou, J. Innovation and creativity in organizations: A state-of-the-science review, prospective commentary, and guiding framework. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1297–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Preacher, K.J.; Zyphur, M.J.; Zhang, Z. A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychol. Methods 2010, 15, 209–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tyagi, V.; Hanoch, Y.; Hall, S.D.; Runco, M.; Denham, S.L. The risky side of creativity: Domain specific risk taking in creative individuals. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tett, R.P.; Guterman, H.A. Situation trait relevance, trait expression, and cross-situational consistency: Testing a principle of trait activation. J. Res. Pers. 2000, 34, 397–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasifoglu Elidemir, S.; Ozturen, A.; Bayighomog, S.W. Innovative behaviors, employee creativity, and sustainable competitive advantage: A moderated mediation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edmondson, A. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 350–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Items | Factor 1 (Cre) | Factor 2 (In) | Factor 3 (Mo) | Factor 4 (TI) | Factor 5 (PP) | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cre1 | 0.900 | 0.101 | 0.128 | 0.002 | 0.054 | 0.96 |

| Cre2 | 0.937 | 0.084 | 0.077 | 0.024 | 0.049 | |

| Cre3 | 0.951 | 0.060 | 0.031 | 0.004 | 0.018 | |

| Cre4 | 0.891 | 0.006 | 0.049 | −0.021 | 0.051 | |

| Cre5 | 0.902 | 0.069 | 0.074 | 0.044 | 0.040 | |

| Cre6 | 0.887 | 0.035 | 0.062 | 0.046 | 0.116 | |

| InSu1 | 0.055 | 0.809 | 0.185 | 0.088 | 0.154 | 0.96 |

| InSu2 | 0.051 | 0.796 | 0.196 | 0.138 | 0.151 | |

| InTM1 | 0.057 | 0.897 | 0.210 | 0.164 | 0.062 | |

| InTM2 | 0.071 | 0.909 | 0.166 | 0.139 | 0.047 | |

| InOT1 | 0.078 | 0.903 | 0.141 | 0.138 | 0.085 | |

| InOT2 | 0.060 | 0.912 | 0.091 | 0.119 | 0.033 | |

| MoSu1 | 0.087 | 0.286 | 0.699 | 0.032 | 0.228 | 0.92 |

| MoSu2 | 0.057 | 0.273 | 0.650 | 0.018 | 0.154 | |

| MoTM1 | 0.094 | 0.113 | 0.873 | −0.034 | 0.032 | |

| MoTM2 | 0.064 | 0.123 | 0.932 | 0.021 | 0.050 | |

| MoOT1 | 0.059 | 0.128 | 0.896 | 0.088 | 0.061 | |

| MoOT2 | 0.072 | 0.123 | 0.936 | 0.047 | 0.041 | |

| TI1 | −0.005 | 0.153 | −0.005 | 0.825 | 0.038 | 0.91 |

| TI2 | −0.001 | 0.052 | 0.169 | 0.867 | 0.028 | |

| TI3 | 0.058 | 0.105 | 0.123 | 0.849 | 0.053 | |

| TI4 | 0.022 | 0.211 | −0.055 | 0.857 | 0.028 | |

| TI5 | 0.012 | 0.137 | −0.086 | 0.821 | 0.139 | |

| PP1 | 0.041 | 0.187 | 0.023 | 0.076 | 0.803 | 0.84 |

| PP2 | 0.109 | 0.139 | 0.029 | 0.119 | 0.858 | |

| PP3 | 0.073 | −0.089 | 0.335 | −0.013 | 0.710 | |

| PP4 | 0.054 | 0.154 | 0.108 | 0.076 | 0.805 | |

| Eigenvalues | 5.069 | 4.993 | 4.479 | 3.713 | 2.727 | |

| Variance explained (%) | 18.774 | 18.494 | 16.588 | 13.750 | 10.100 | |

| Accumulative variance explained (%) | 18.774 | 37.269 | 53.857 | 67.607 | 77.707 |

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 36.98 | 8.42 | |||||||||||

| 2. Gender | 0.57 | 0.50 | 0.04 | ||||||||||

| 3. Education | 2.83 | 0.73 | −0.03 | 0.19 *** | |||||||||

| 4. Tenure | 7.49 | 7.68 | 0.67 *** | 0.12 * | −0.05 | ||||||||

| 5. Task Type | 0.23 | 0.42 | −0.12 * | 0.06 | 0.14 ** | −0.19 *** | |||||||

| 6. Task Interdependence | 4.00 | 1.11 | −0.06 | 0.03 | −0.12 * | −0.06 | 0.08 | ||||||

| 7. Proactive Personality | 4.39 | 0.99 | 0.17 ** | 0.16 ** | 0.01 | 0.10 | −0.08 | 0.17 ** | |||||

| 8. Frequency of Inquiry | 3.86 | 1.32 | −0.13 * | 0.01 | −0.04 | −0.09 | 0.10 | 0.30 *** | 0.26 *** | ||||

| 9. Breadth of Inquiry | 0.66 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.08 | 0.06 | −0.06 | −0.09 | −0.01 | |||

| 10. Frequency of Monitoring | 4.71 | 1.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.07 | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.11 * | 0.27 *** | 0.39 *** | −0.03 | ||

| 11. Breadth of Monitoring | 0.66 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.10 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.09 | 0.11 * | 0.05 | |

| 12. Creativity | 4.55 | 1.10 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.16 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.01 | 0.18 ** | 0.02 |

| Variable | Creativity | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | Model 10 | |

| Step 1: Control | ||||||||||

| Age | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Gender | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.08 |

| Education | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Tenure | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 |

| Task Type | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.20 |

| Task Interdependence | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Step 2: Main Effect | ||||||||||

| Proactive Personality | 0.16 * | 0.12 | 0.11 | |||||||

| Step 3: Feedback-Seeking Behavior | ||||||||||

| Frequency of Inquiry | 0.13 ** | 0.13 ** | 0.11 * | |||||||

| Breadth of Inquiry | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.86 | |||||||

| Frequency of Monitoring | 0.18 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.15 * | |||||||

| Breadth of Monitoring | 0.97 | 0.49 | 0.81 | |||||||

| Pseudo R square | 0.002 | 0.019 | 0.023 | 0.000 | 0.020 | 0.029 | 0.027 | 0.000 | 0.025 | 0.032 |

| Variable | Frequency of Inquiry | Breadth of Inquiry | Frequency of Monitoring | Breadth of Monitoring | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | |

| Step 1: Control | ||||||||

| Age | −0.018 | −0.061 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | −0.004 | −0.000 | −0.000 |

| Gender | −0.019 | −0.122 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.028 | −0.058 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Education | −0.011 | −0.020 | −0.002 | −0.002 | 0.135 | 0.125 | −0.002 | −0.002 |

| Tenure | 0.005 | 0.008 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Task Type | 0.238 | 0.310 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.164 | 0.218 | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| Task Interdependence | 0.345 *** | 0.293 *** | −0.001 | 0.000 | 0.093 * | 0.052 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Step 2: Main Effect | ||||||||

| Proactive Personality | 0.342 *** | −0.002 | 0.278 *** | −0.001 | ||||

| Pseudo R square | 0.093 | 0.154 | 0.029 | 0.029 | 0.001 | 0.071 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Independent Variable | Mediators | Dependent Variable | Conditional Indirect Effect | Bootstrapping Bias-Corrected 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Proactive Personality | Frequency of Feedback Inquiry | Creativity | 0.038 | 0.007 | 0.088 |

| Frequency of Feedback Monitoring | 0.044 | 0.012 | 0.100 | ||

| Breadth of Feedback Inquiry | −0.002 | −0.021 | 0.008 | ||

| Breadth of Feedback Monitoring | −0.001 | −0.015 | 0.006 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chae, H.; Park, J. The Effect of Proactive Personality on Creativity: The Mediating Role of Feedback-Seeking Behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1495. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031495

Chae H, Park J. The Effect of Proactive Personality on Creativity: The Mediating Role of Feedback-Seeking Behavior. Sustainability. 2022; 14(3):1495. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031495

Chicago/Turabian StyleChae, Heesun, and Jisung Park. 2022. "The Effect of Proactive Personality on Creativity: The Mediating Role of Feedback-Seeking Behavior" Sustainability 14, no. 3: 1495. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031495

APA StyleChae, H., & Park, J. (2022). The Effect of Proactive Personality on Creativity: The Mediating Role of Feedback-Seeking Behavior. Sustainability, 14(3), 1495. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031495