Abstract

Background: Cyber security has turned out to be one of the main challenges of recent years. As the variety of system and application vulnerabilities has increased dramatically in recent years, cyber attackers have managed to penetrate the networks and infrastructures of larger numbers of companies, thus increasing the latter’s exposure to cyber threats. To mitigate this exposure, it is crucial for CISOs to have sufficient training and skills to help them identify how well security controls are managed and whether these controls offer the company sufficient protection against cyber threats, as expected. However, recent literature shows a lack of clarity regarding the manner in which the CISOs’ role and the companies’ investment in their skills should change in view of these developments. Therefore, the aim of this study is to investigate the relationship between the CISOs’ level of cyber security-related preparation to mitigate cyber threats (and specifically, the companies’ attitudes toward investing in such preparation) and the recent evolution of cyber threats. Methods: The study data are based on the following public resources: (1) recent scientific literature; (2) cyber threat-related opinion news articles; and (3) OWASP’s reported list of vulnerabilities. Data analysis was performed using various text mining methods and tools. Results: The study’s findings show that although the implementation of cyber defense tools has gained more serious attention in recent years, CISOs still lack sufficient support from management and sufficient knowledge and skills to mitigate current and new cyber threats. Conclusions: The research outcomes may allow practitioners to examine whether the companies’ level of cyber security controls matches the CISOs’ skills, and whether a comprehensive security education program is required. The present article discusses these findings and their implications.

1. Introduction

The Internet and the development of related technologies in recent years have contributed to the successful management of processes and activities in companies, but they are also perceived as having a negative impact on the latter as these show a growing dependence on them [1]. Cyber security threats are among the most negative outcomes of Internet-based technologies, and they have become one of the main challenges of recent years [2]. The increased use of technology during the COVID-19 pandemic has particularly intensified this negative outcome, forcing many companies around the world, both public and private (i.e., unregulated), to examine the strength of their cyber security vis-à-vis their risk exposure [3]. These threats are broad and diverse. They include, for example, phishing attacks, which are threats aimed at fooling people into clicking on links or opening attachments that may cause a malicious software to be installed on their computers, thus exposing them to leaks of sensitive data from their devices [4]. Another prevalent threat is ransomware attacks, which are characterized by the installation of ransomware viruses. This type of malware is often installed on one of the company’s endpoint computers, where it tries to exploit an application’s vulnerabilities to leak sensitive data to the attackers through the Internet. The malware employs an encryption method that renders the company’s data unavailable or inaccessible until the ransom money is paid to the attackers [5]. In addition, IoT devices operated by the company—e.g., smart web cameras, manufacturing equipment, security systems, network elements (switches and routers), are also exposed to cyber-attacks. These attacks are usually executed by “black-hat hackers” [6] who, according to Kaspersky, are in fact “criminals who break into computer networks with malicious intent. They may also release malware that destroys files, holds computers hostage, or steals passwords, credit card numbers, and other personal information” [7]. The stolen data may also be used to penetrate the company’s databases in order to steal additional sensitive information that can be used to extort money from the business.

While threats and risks in general are evaluated according to the probability of them generating unwanted events that cause a certain amount of damage [8], cyber risks are mainly perceived as those that damage the company’s technology or information in a way that in fact exposes the latter to future claims of neglect by customers, suppliers, and even their own employees [9]. These risks may vary and may cause business disruptions that affect the company’s reputation and lead to loss of money. One of the main reasons for the existence of such risks is derived from the fact that the firm is connected to the Internet by means of its servers, endpoint computers, and information systems, which are used to communicate with external and internal devices through the firm’s network and enable the delivery of data communication that supports the firm’s business activities. The fact that computers and network elements that are connected to the Internet expose companies to cyber risks has forced the latter to update their cyber protection policies and hire cyber experts who are responsible for mitigating the cyber vulnerabilities found in said network and computer elements [10]. Risk mitigation may be carried out using cyber defense technologies as part of the cyber security control implementation plans that appear in frameworks such as NIST 800-53 and ISO 27001 [11]. However, these frameworks serve only as guidelines for practical activities, and it is the job of the Chief Information Security Officers,)CISOs(, to consider how to strike a balance between cyber security activities necessary to pursue the company’s business and the prevalent best practices in the field of cyber security governance [12].

1.1. The CISO’s Role: Protecting against Information and Cyber Security Risks

CISOs are hired by companies as experts and are considered to have sufficient training and knowledge to mitigate cyber risks. The CISO’s role is mainly to protect the company against information and cyber security threats. This can be achieved by executing tasks that include, among others, increasing the awareness of employees and managers to cyber risks; implementing OT (Operational Technology) and IT (Information Technology) best practices; performing corrective actions regarding software and technology failures; carrying out maintenance; configuring internal and external infrastructures; and much more [13].

Following the CIA triangle (Confidentiality, Integrity, and Availability of the data) used to describe the basic information security model [14], the various topics involved in the above-mentioned tasks can be divided into the following categories:

- (1)

- Legacy software: systems that run on such software lack the authentication, verification, integrity, and patches for recently found vulnerabilities required to secure uncontrolled access to them.

- (2)

- Default configuration: a situation in which out-of-the-box systems or applications holding the default password or baseline configuration can be easily hacked by cyber attackers.

- (3)

- Lack of encryption and authentication in SCADA commands and industrial control protocols (OT) as well as in IT systems (enabling, for instance, man-in-the-middle attacks).

- (4)

- Remote access policies: unaudited remote access servers which are used by hackers as backdoors to penetrate OT networks and take over LAN (local area network) compartments.

- (5)

- Policies and procedures that are not enforced or set as mandatory guidelines.

- (6)

- Lack of network segmentation, which may derive from a network misconfiguration or a failure in the firewall rule-set design and exposes the company to malicious activities.

- (7)

- DDoS attacks used by cyber attackers to sabotage systems, especially if they run vulnerable unpatched applications.

- (8)

- Web application attacks that derive from the poor design of human-computer interfaces (HMI) and their programmable logic processes. An example of these is the structured query language (SQL) injection attack, which is considered to be the most common web hacking technique; it uses an SQL injection code to destroy the victims’ database by bypassing the authentication process of the targeted web page.

- (9)

- Malware: systems and applications that are exposed to malware should run and incorporate host and endpoint-based anti-malware protection tools; this also includes patch-management polices to reduce the level of risk exposure.

- (10)

- Command injection, which involves the insertion of unverified instructions in the company’s servers and may cause an execution of undesired commands by OT systems.

- (11)

- Phishing Attacks: a type of social engineering attack which is often used to steal data such as login credentials. Recipients are tricked into opening a malicious link that may lead to the installation of malware or expose sensitive information to the hacker.

In addition to the above-mentioned risks, the human factor (employees and managers, including CISOs) is also considered a resource that may contribute to the company’s risk exposure, whether intentionally or not, by ignoring important cyber security policies or not implementing them correctly [15].

As the highest-ranking information officers in the firm, CISOs are responsible for successfully managing and handling all these actions, subject to existing best practices and in accordance with their skills and expertise [16].

1.2. Research Aim and Research Questions

In recent years, the academic literature has dealt largely with new cyber security threats and new mitigation methods. However, only few studies have explored the degree to which cyber security is successfully managed by CISOs and whether their skills and knowledge are sufficient to protect companies from cyber damage. Therefore, the aim of this study is to investigate the relationship between the CISOs’ level of cyber security-related preparation to mitigate cyber threats (and specifically, the companies’ attitudes toward investing in such preparation) and the recent evolution of cyber threats. To do so, it proposes to explore the following research questions:

- In what manner do existing and new cyber threats influence the CISO’s role and ability to mitigate them successfully as a function of their knowledge and skills, according to the scientific literature?

- Have corporate attitudes toward investing in CISOs’ training and knowledge changed with the emergence of new cyber security threats in recent years?

These questions are addressed here through the analysis of exhaustive scientific literature documents as well as cyber security opinion articles (known as opinion columns) written by cyber experts and extracted from the media. This analysis was carried out using the following text mining methodologies: sentiment analysis, topic modeling, and a bag-of-words model. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to deal with such questions and aims.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: the materials and methods used to collect the literature and the expert opinion columns are described in Section 2; Section 3 shows the text analysis performed using NLP (natural language processing) methods; Section 4 offers a discussion of the results; Section 5 offers the conclusions, and the main insights; finally, Section 6 deals with limitations and farther research of this study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General

To address the research questions, the following objectives and derived questions were constructed:

- Objective I: Analysis of the relevant scientific and expert opinion literature for the period between 2012 and 2022.

- Derived Question 1: What trends regarding cyber threats and related vulnerabilities are portrayed in the literature?

- Derived Question 2: What can be learned from the analysis of the extant literature about CISOs’ cyber security skills and their success in implementing cyber security policies and frameworks?

- Objective II: Analysis of corporate attitudes toward investing in CISOs’ cyber security training and knowledge.

- Derived Question 3: To what extent have these attitudes changed throughout the years (assuming that there have been changes in cyber threats)?

- Derived Question 4: Are these attitudes in line with the current scientific literature and the cyber security experts’ views as reflected in published expert opinion columns?

2.2. Data Collection

For the purpose of tracing the existing scientific literature and answering the research questions as appears in Objective I, we conducted two processes:

(A) The collection of a corpus of scientific articles from the Web of Science (WoS) database. The corpus was based on scientific papers published in peer-reviewed journals and conference proceedings. Each paper was examined in accordance with Sardi et al. [17] to verify its compliance with the following criteria: (1) Is it related to the topic under investigation? (2) Does it focus on cyber managerial issues, such as mentioning cyber security frameworks like the NIST 800-53 and ISO 270001? (3) Is it written in English? (4) Finally, to validate the papers’ suitability to be included in the corpus, each title was fully read to verify that the document’s pertinence to the explored domain. In addition, the papers in the scientific corpus were classified according to the following issues: (1) number of total publications per journal and total citations per year, and (2) type of paper (theoretical, literature review, descriptive, or empirical research). A list of the 5 most cited scientific corpus papers in each search category is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Five most cited scientific corpus papers per keyword search category.

(B) Following the vulnerability analysis and risk assessment mentioned in Northern et al. [18], the most dangerous common vulnerabilities and exposures (CVEs) for the years 2019 to 2021, which had scores > 9.0 and were hosted at cve.mitre.org, and the Ultimate Security Vulnerability Data source were extracted (Table 2). These vulnerabilities were used to evaluate whether those CVEs are mentioned explicitly or inexplicitly in the document corpus using text mining analysis.

Table 2.

List of 50 most dangerous (Score > 9.0) CVEs in 2019–2021.

To address Objective II, 3742 opinion news articles written by cyber specialists and provided by Ahmed et al. [19] through the MendeleyTM repository were extracted (see Table 3 for examples). These articles were also analyzed for any mention of attitudes related to the investment in CISOs’ training to handle new cyber threats and mitigate the most dangerous vulnerabilities described above.

Table 3.

Examples of several news articles written by cyber specialists.

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Scientific Paper Extraction According to Topic and Affiliated Keywords

Scientific papers were extracted from the Web of Science (WoS) database using the InCites graphical interface. Following the guidelines of Gheyas and Abdallah [20], a systematic literature corpus collection was performed for the period between 2012 and 2022. The search was configured by the graphical search combo box and contained the following editions:

- Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI-EXPANDED):1993–present

- Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI): 1993–present

- Arts & Humanities Citation Index (AHCI): 1993–present

- Conference Proceedings Citation Index—Science (CPCI-S): 1990–present

- Conference Proceedings Citation Index—Social Science & Humanities (CPCI-SSH): 1990–present

- Emerging Sources Citations Index (ESCI): 2015–present.

The papers’ titles were searched for topics using keywords suggested by Sardi et al. [17]: “CISO” and/or “Chief Information Security Officer” and/or “Awareness” and/or “Management” and/or “Risk Management” and/or “Risk Assessment” and/or “Risk Evaluation” and/or “Guidelines” and/or “Cybersecurity” and/or “Cyber-Risk” and/or “Ransomware” and/or “Malware” and/or “Threats”.

2.3.2. Extraction and Analysis of Vulnerabilities List and Cyber Experts’ Opinion Articles

Following Mounika et al. [21], the OWASP’s top vulnerabilities (score > 9.0) in the last 3 years were extracted. This process was based on the CVE® list (cve.mitre.org, accessed on 29 December 2021) and the CVE Details Ultimate Security Vulnerability Data source (www.cvedetails.com, accessed on 29 December 2021). Those sources provide up-to-date information related to common cyber vulnerabilities and exposures (CVEs) according to family categories. The details related to each CVE were saved in a separate row in an Excel file designed with the following columns: Column 1—Sequence Number; Column 2—CVE ID; Column 3—Publication Date; Column 4—CVE Description. In addition, following Ahmed et al. [19], a total of 3742 opinion columns written by cyber experts were harvested from the Mendeley repository. The repository was clustered into 4 groups according to its labels: (1) Cyber Attack, (2) Data Breaches, (3) Malware, and (4) Vulnerability. The articles in each cluster were analyzed using several text mining tools (JavaScript, R code, and OrangeTM toolkit) as described below (refer to Topic Modeling and Sentiment Analysis) to generate topic modeling and a word cloud for each cluster.

Topic Modeling and Sentiment Analysis

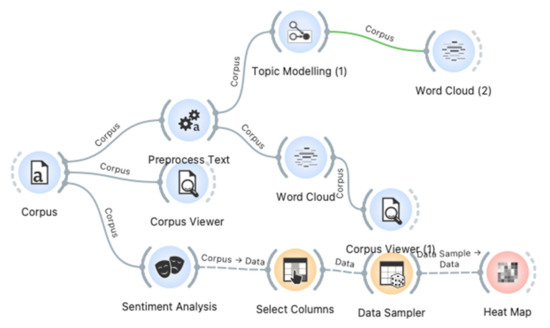

For the topic modeling evaluation process, which was used to examine whether the scientific papers and expert opinion columns are related to the same topics and address them in different ways, an out-of-the-box tool and a programming code written in R and JavaScript were used. The topic modeling feature provided by the OrangeTM toolkit (Figure 1) and an R code script executed using RStudio were implemented [22]. The JavaScript code was executed using the Eclipse Foundation’s IDE 2021-12 Package for JavaScript programming. The topic modeling procedure was used to analyze two types of document corpora: scientific papers and expert opinion columns. The analysis was performed on both repositories in the same manner: following Korenčić et al. [23], the latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) unsupervised learning algorithm was used to analyze a large volume of unlabeled text through the evaluation of clusters of words that frequently occur together [24,25], under the assumption that similar words appearing in similar contexts represent the same topic. Subsequently, the scientific corpus and the expert opinion columns’ content were analyzed using the following methods: (1) A search for paragraphs containing words provided by the Merriam-Webster online thesaurus lexicon (https://www.merriam-webster.com/thesaurus, accessed on 29 December 2021). The words selected were synonyms and antonyms of the verbs “to perform”, “to succeed”, “to fail”, and “to train”, which are related both to the CISOs’ performance evaluation by the company’s senior management and to the willingness of the latter to invest in the CISOs’ training skills; (2) bag-of-words model; and (3) sentiment analysis.

Figure 1.

Topic modeling and sentiment analysis model created using the OrangeTM toolkit.

Topic Modeling Using the LDA Method and Sentiment Analysis

The R script and the jsLDA master code in JavaScript language were used for topic modeling analysis. The LDA (Latent Dirichlet Allocation) algorithm postulates that each document may contain several words that may be affiliated with distinct topics in the document. For the scientific corpus, the text of each document was cleaned and categorized in the following citation degree scale (ranging from 1 to 5, where 1 = low and 5 = very high) according to the number of affiliated citations in each paper. Documents with 0–10 citations were defined as having an overall citation degree of 1; the amount of 11–20 citations granted the paper an overall citation degree of 2; papers with 21–30 citations were set to have an overall citation degree of 3; papers with 31–40 citations were set at an overall citation degree of 4; and papers exceeding 41 citations were defined as having an overall citation degree of 5. No pre-processing was performed on the expert opinion column list. However, topic modeling and a word cloud were constructed to evaluate whether the content of documents related to the CISOs’ performance and skills matches the companies’ willingness to invest in their training. Finally, sentiment analysis was conducted on the scientific and the expert opinion corpora.

Figure 1 exhibits the entire schema of the model designed by the OrangeTM toolkit. The model executed three types of analyses: word cloud, topic modeling, and sentiment. In the first stage, the corpus component was used to load scientific papers and expert opinion columns to the database. These documents were visualized using the Corpus Viewer component. In the next phase, each document’s abstract was “cleaned” from undesired text such as numbers, symbols, and adjectives to ready it for analysis using the Topic Modeling component. In addition, the Word Cloud component was used to evaluate the frequency of words in each document and to present a complete frequency-based diagram on both types of documents. The Sentiment Analysis component was used to present the sentiment heat map (prepared with the help of the Heat Map component). In preparation for this, sentiment data was selected using the “Select Columns” and “Data Sampler” components with the following configuration: Selected Features: positive, negative, neutral, and compound patterns; Target = Category; Metadata = Tests. The advantage of this diagram lies in its simplicity. However, in order to perform complex diagrams and further analyses (such as in the case of topic modeling), it was also mandatory to execute programming code (in JavaScript and R).

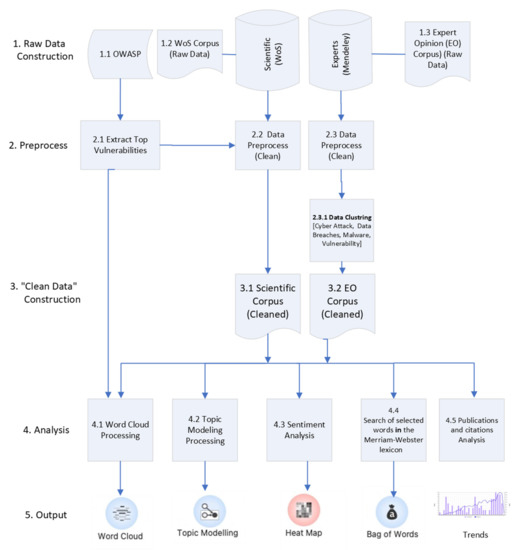

A summary related to the initial process, analyses, and outputs is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

A summary schema of the study.

3. Results

3.1. Science Mapping and Scientometric Data Analysis

3.1.1. Distribution of Documents Related to Cyber Security and CISO Appearing in the Scientific Literature in 1991–2022

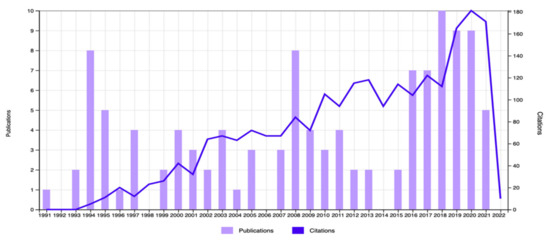

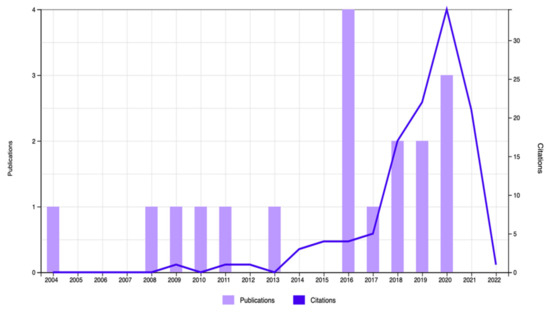

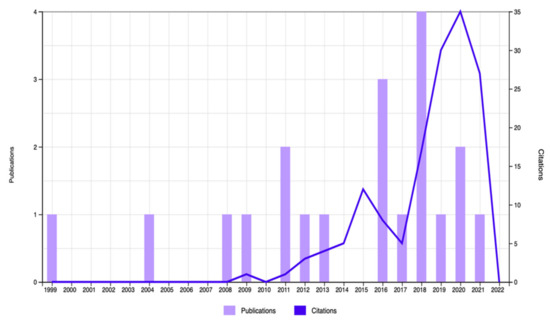

The documents’ distribution for the 2011–2022 period revealed a consistent trend in the number of citations dealing with cyber security issues and the role of the CISOs. A total of 96 publication with 2107 citations were found during the search process conducted using the keywords “CISO” or “Chief Information Security Officer” and “risk assessment”; 115 publications with 1972 citations were found during the search process conducted with “CISO” or “Chief Information Security Officer” and “risk management”; and 95 publications with 2099 citations were found during the search process implemented using the keywords “CISO” or “Chief Information Security Officer” and “risk awareness”. This document distribution also showed that that the number of citations appearing in the years 2018 to 2021 was higher than the number of citations mentioned in previous years (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5). With respect to the keywords “risk management”, “risk assessment”, “training”, and “guidelines”, it was found that more than 50% of the publications belonged to the field of Computer Science and Information Systems (Table 4). The evaluation of the 5 most prominent topics mentioned in documents published in recent years revealed that cyber security audits, the effectiveness of cyber security controls, data security breaches, the impact of the company’s investment on cyber security controls, and the gap between the companies’ investment in cyber security controls and the contribution of the CISO’s skills to implement successfully company’s cyber security controls are the main topics that still concern academic scholars and practicians (Table 1).

Figure 3.

Total publications and citations (topic = CISO and risk management).

Figure 4.

Total publications and citations (topic = CISO and training).

Figure 5.

Total publications and citations (topic = CISO and guidelines).

Table 4.

Prominent distribution fields in the corpus of documents obtained with various keyword searches and document distribution in relevant fields according to WoS category.

3.1.2. Topic Modeling and Sentiment Analysis

The execution of the jsLDA in JavaScript and R code on the scientific papers and expert columns corpora demonstrated the following.

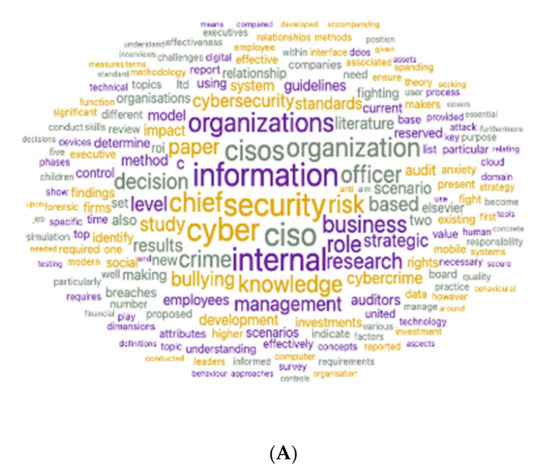

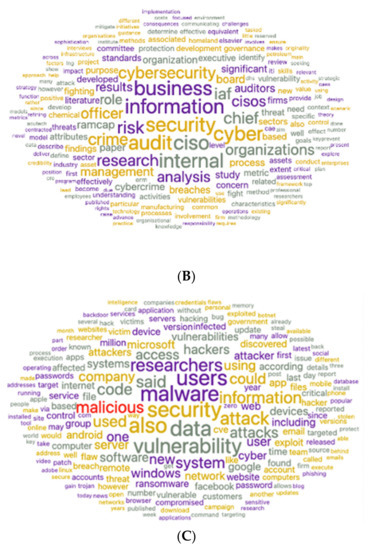

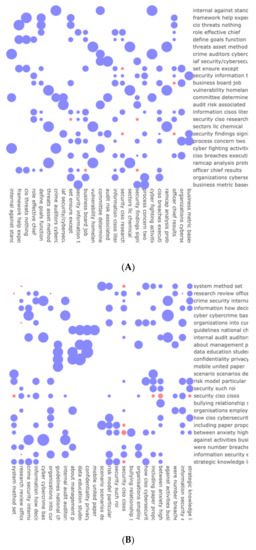

As shown in Table 5, topic specificity (a measure of venues that depends on the titles of the papers published in a specific venue over a specific year) assumes that longer words often carry more specific meaning (close to 1), whereas shorter words may not belong to the examined topic at all (close to 0) and word frequency analyses were performed on the scientific corpus for each of the following categories: risk assessment, cyber guidelines, and cyber risk management. In the risk assessment category, the words “audit”, “internal”, “cyber”, and “officer” received the highest specificity score (close to 1). In the cyber guidelines category, the words “cyber” and “organization” received the highest specificity scores (1 and 0.83, respectively). Finally, in the cyber risk management category, most of the words received a low topic specificity score ranging between 0.032 and 0.2. Moreover, the word cloud distributions conducted on the abstracts and titles of documents extracted from the scientific corpus (Figure 6A,B) and the expert opinion columns (Figure 6C) provide interesting results. While Figure 6C indicates that the investment in CISO training and knowledge to cope with cyber breaches is quite low (the relevant words hardly appear in the cloud’s center, and when they do, they are in quite a small font), Figure 6A,B shows that the role of the CISO as a guard against cyber threats is of importance. Words such as “management”, “knowledge”, “CISO”, and “study” appear frequently in these word clouds, thus pointing to their importance. This finding was also supported by the topic modeling correlation analysis conducted on the scientific corpus of documents belonging to the risk assessment cluster. The analysis revealed that the abstracts do not contain much information on the attitude toward investment in CISOs’ skills and training, but they mention its importance. For example, the evaluation of the blue dots reveals that phrases such as “The effective role of the chief information security officer …” are not considered to have priority over other topics (i.e., they are portrayed as small dots). On the contrary, topics that discuss security solutions, i.e., “organizations’ cyber security defense solutions”, are preferred (Figure 7A). In the risk assessment cluster, the most prominent topics found via this analysis were threats and vulnerabilities, audit risk, cyber fighting activities, organization processes, framework, and threats. The least prominent topics were CISO and research. In the same manner, the most prominent topics contained in at the scientific corpus of documents belonging to the “CISO + guidelines” cluster (Figure 6B and Figure 7B) were education, risk management and model, cybercrime, business activities, and information security. The least prominent topics were security and method officer. For example, in Figure 6B, the dominant words were “study”, “management”, and “CISO”, while Figure 6B showed “CISOs’ strategic knowledge” and “CISO employment by organizations ” to be dominant.

Table 5.

Topic specificity and word frequency results for each explored category. Note: words occurring in only one topic have a specificity of 1, words evenly distributed among all topics have a specificity of 0.

Figure 6.

(A) Word cloud distribution of WoS documents (label = risk assessment). (B) Word cloud distribution of WoS documents (label = cyber guidelines). (C) Word cloud distribution of expert opinion columns.

Figure 7.

(A) Topic correlations for risk assessment category. (B) Topic correlations for cyber guidelines category.

The ranking and cited reference count of the scientific articles within each category is shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

List of papers found to be relevant to the topics “CISO” and “risk management”; “risk Assessment”; “Awareness”; “Training”; “Guidelines” in the domain of Information Systems, Computer Science, and Management.

As mentioned in Section “Topic Modeling Using the LDA Method and Sentiment Analysis”, a list of words was produced on the basis of the synonyms and antonyms of a selected group of verbs, and subsequently the corpora of documents (scientific articles and expert opinion columns) were searched for those same words. The verb “to perform” provided the following synonyms, which were found in both types of documents: “achieve”, “commit”, “compass”, “execute”, “effect”, “implement”, “repeat”, “attain”, “complete”, “end”, “skimp”, “slur”, “run”, “control”, “direct”, “manage”, “regulate”, and “supervise”.

The verb “to succeed” generated the following synonyms found in the scientific literature and the expert opinion columns: “deliver” and “work out”. The synonyms found for the verb “to fail” that appeared both in the scientific literature and opinion columns are “break down” and “malfunction”. In the case of the verb “to train”, the synonyms found in the scientific literature and the expert opinion columns are “educate” and “instruct”.

In general, the results show that both the scientific literature and the experts’ attitude toward CISOs indicate that companies do not tend to invest in the latter’s skills and training above a certain amount of money. For example, in scientific papers extracted from WoS using a search process with the keywords “CISO + training” and also searched in the abstract with the word “implement”, the following text emerged: “As organizations continue to invest in phishing awareness training programs, many chief information security officers (CISOs) are concerned when their training exercise click rates are high or variable, as they must justify training budgets to organization officials who question the efficacy of awareness training when click rates are not declining” [26] (p. 1). When the searched word was “deliver”, the following paragraphs were found:

- (1)

- “We conclude that as the CISO role continues to develop CISOs need to reflect on effective ways of achieving credibility in their organizations and, in particular, to work on communicating with employees and engaging them in security initiatives” [27] (p. 396).

- (2)

- “While it may seem obvious that their role is to define and deliver organizational security goals, there has been little discussion on what makes a CISO able to deliver this effectively” [27] (p. 396).

In the same manner, the following attitude toward CISOs’ training and performance emerged from the expert opinion columns:

- (3)

- “CISOs and CIOs need to know better than anyone the security pulse of their organizations. On the other hand, they cannot be flooded with every changing detail” [28].

- (4)

- “Moreover, CIOs and CISOs are heavily dependent on their team for knowledge and often lack the immediate interaction with the events in real-time” [29].

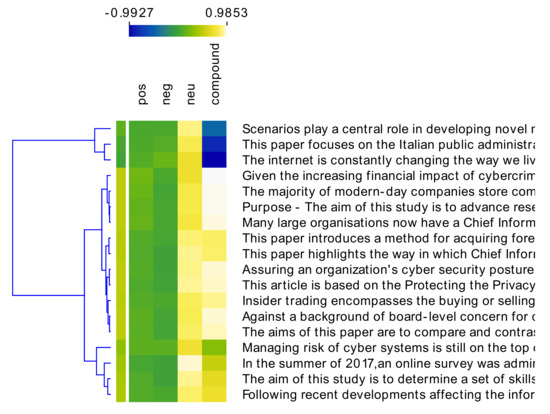

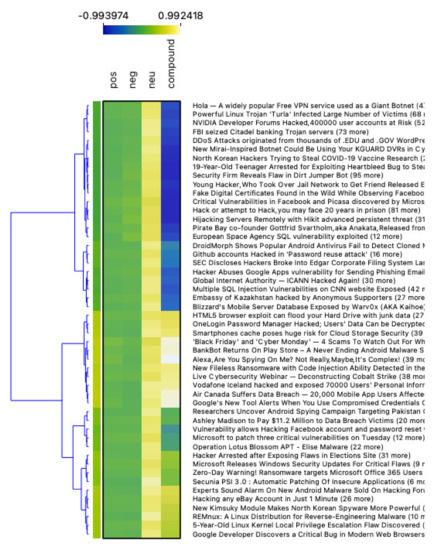

Finally, sentiment analysis conducted on the scientific corpus and the expert opinion columns shows that while the former points to a weak positive or neutral attitude of management toward investing money in CISOs’ training and skills (Figure 8), experts are much more negative on the issue (Figure 9), although they mention that investing in CISO education is mandatory. They believe that such an investment is crucial for the CISO’s success. Furthermore, they think that as CISOs enhance their skills and knowledge, they may implement improved cyber defense tools that match current and future threats, thus contributing to the companies’ cyber strength. This attitude is also supported by the fact that references to the top CVEs, whether this is through words related to type of vulnerability or the exact CVE ID, appear much more frequently in the word cloud distribution of the expert opinion columns compared to that of the scientific corpus (Figure 6C). For example, the word cloud extracted from the expert opinion columns mentions words such as “CVE” (2050 times); “execute” (927 times); “execution” (1130 times) and “memory” (884 times), which are hardly found in the scientific paper corpus. These words are mentioned in the top CVE list (“CVE” as part of the CVE ID; “execute” or “execution” as part of Exec Code; and “memory” as part of the Buffer Overflow and Exec Code Memory Corruption).

Figure 8.

Sentiment analysis conducted on scientific papers related to training and guidelines.

Figure 9.

Sentiment analysis conducted on expert opinion columns related to training and guidelines.

4. Discussion

The present study shows that there is a consistent increase in scientific literature and expert opinion discussions concerning cyber threats in general and the role of the CISO, as a key function that protects companies from cyber risks, in particular. The literature shows that the number of relevant citations throughout the years, especially since 2018, has also increased. The results show that in order to maintain or improve their cyber security strength, companies must do better in the fields of risk management, risk assessment related to audits, increasing the awareness of employees and managers, and improving the skills and training of CISOs to mitigate new threats while implementing new guidelines. Among recently found vulnerabilities, data breach malware codes and ransomware are critical cyber threats to businesses. A correlation analysis of the documents shows that there is still a gap between the companies’ investment in cyber security controls and their willingness to invest in CISOs’ skills. In addition, the most dangerous vulnerabilities (and the affiliated vulnerability types) appearing in the CVE lists for the last 3 years are hardly mentioned in the scientific literature as problems or provided a theoretical/practical solution, while they are more referenced in expert opinion columns. Moreover, the findings show that while the scientific literature is not heavily concerned with the lack of CISO knowledge and training and its effect on the CISO’s ability to handle and mitigate cyber threats successfully, expert opinion columns clearly show that this concern should be taken into much greater consideration, as experts dwell much more on said training and skills than on providing practical solutions to cyber threats. These findings are supported by text analysis using both topic modeling and sentiment analysis.

5. Conclusions

From all of the above, it can be concluded that the scientific literature is mainly interested in academic solutions or models for the mitigation of risks, while it does not pay much attention to the role, skills, and knowledge of CISOs as safeguards against cyber threats. On the contrary, practitioners are much more concerned with the lack of efficient and trained CISOs who can take the lead and control the flexible and rapidly changing environment and risks related to cyber threats. Finally, this study points to the need for companies to evaluate the level of their CISOs’ knowledge of new cyber challenges and risks, and to consistently invest both in improving this knowledge and in new technological solutions to mitigate those risks. The study’s conclusions indicate that a simultaneous investment in both fronts might improve the companies’ cyber strength and reduce additional costs in the future that might result from any neglect in the present level of commitment to either field.

6. Limitations and Further Research

The study did not implement any questionnaire-based analysis designed for hypothesis testing. It is suggested that future research extends the current study by examining companies in search of areas that show a gap in the CISOs’ skills and knowledge required to successfully mitigate cyber threats, and by suggesting ways to reduce that gap in the long run. Moreover, it is important to mention that the expert opinion columns written by cyber specialists may contain content that might be considered to reveal a pronounced tendency toward greater subjectivity and partiality. In this study, out of a total of 3742 articles, only 1% showed an extreme tendency toward partiality (either positive or negative), and they were read in full to consider their fit to the research corpus, it is suggested that future studies present new approaches to distinguish between legitimate opinions and those that might be considered to be too subjective or partial to be taken into account for research purposes.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by Ariel Cyber Innovation Center and the Research and Development Authority at Ariel University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ariel University (Protocol Code: AU-SOC-MZ-20211130, Date of Approval: 30 November 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable for studies not involving humans or animals.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ariel Cyber Innovation Center in conjunction with the Israel National Cyber directorate in the Prime Minister’s Office.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Hasan, M.; Islam, M.M.; Zarif, M.I.I.; Hashem, M.M.A. Attack and anomaly detection in IoT sensors in IoT sites using machine learning approaches. Internet Things 2019, 7, 100059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantha, B.R.; de Soto, B.G. Cyber security challenges and vulnerability assessment in the construction industry. In Proceeding of the Creative Construction Conference 2019, Budapest, Hungary, 29 June–2 July 2019; pp. 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, M. Public–private partnerships in national cyber-security strategies. Int. Aff. 2016, 92, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pienta, D.; Thatcher, J.B.; Johnston, A.C. A taxonomy of phishing: Attack types spanning economic, temporal, breadth, and target boundaries. In Proceedings of the 13th Pre-ICIS Workshop on Information Security and Privacy, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13 December 2018; Volume 1, pp. 2216–2224. [Google Scholar]

- Anghel, M.; Racautanu, A. A note on different types of ransomware attacks. Cryptol. Eprint Arch. 2019, 605. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, K.H.; Shakarian, J. Black-hat hackers’ crisis information processing in the darknet: A case study of cyber underground market shutdowns. In Networks, Hacking, and Media–Citams@30: Now and Then and Tomorrow; Studies in Media and Communications, Volume 17; Wellman, B., Robinson, L., Brienza, C., Chen, W., Cotton, S., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018; pp. 113–135. [Google Scholar]

- Black Hat, White Hat, and Gray Hat Hackers—Definition and Explanation. Available online: https://www.kaspersky.com/resource-center/definitions/hacker-hat-type (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Shetty, S.; McShane, M.; Zhang, L.; Kesan, J.P.; Kamhoua, C.A.; Kwiat, K.; Njilla, L.L. Reducing informational disadvantages to improve cyber risk management. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur. Issues Pract. 2018, 43, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumov, S.; Kabanov, I. Dynamic framework for assessing cyber security risks in a changing environment. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Information Science and Communications Technologies (ICISCT), Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 2–4 November 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, Z. A practical road map for assessing cyber risk. J. Risk Res. 2019, 22, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailloux, L.O.; McEvilley, M.A.; Khou, S.; Pecarina, J.M. Putting the “Systems” in Security Engineering: An Examination of NIST Special Publication 800–160. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2016, 14, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masduki, B.W.; Ramli, K.; Salman, M. Leverage intrusion detection system framework for cyber situational awareness system. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Smart Cities, Automation & Intelligent Computing Systems (ICON-SONICS), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 8–10 November 2017; pp. 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Shcherbakov, M.V.; Glotov, A.V.; Cheremisinov, S.V. Proactive and predictive maintenance of cyber-physical systems. In Cyber-Physical Systems: Advances in Design & Modelling, 1st ed.; Kravets, A.G., Bolshakov, A.A., Shcherbakov, M.V., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 259, pp. 263–278. [Google Scholar]

- Easttom, C.; Butler, W. A modified McCumber cube as a basis for a taxonomy of cyber attacks. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 9th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 7–9 January 2019; pp. 943–949. [Google Scholar]

- Jamilov, R.; Rey, H.; Tahoun, A. The anatomy of cyber risk. NBER Working Paper 28906, National Bureau of Economic Research. 2021. Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w28906 (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Karanja, E.; Rosso, M.A. The chief information security officer: An exploratory study. J. Int. Technol. Inf. Manag. 2017, 26, 23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Sardi, L.; Idri, A.; Fernández-Alemán, J.L. A systematic review of gamification in e-Health. J. Biomed. Inform. 2017, 71, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northern, B.; Burks, T.; Hatcher, M.; Rogers, M.; Ulybyshev, D. VERCASM-CPS: Vulnerability Analysis and Cyber Risk Assessment for Cyber-Physical Systems. Information 2021, 12, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Anwar, T.; Tanvir, S.; Saha, R.; Shoumo, S.Z.H.; Hossain, S.; Rasel, A.A. Cybersecurity News Article Dataset; Mendeley Data, V1; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gheyas, I.A.; Abdallah, A.E. Detection and Prediction of Insider Threats to Cyber Security: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Big Data Anal. 2016, 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mounika, V.; Yuan, X.; Bandaru, K. Analyzing CVE Database Using Unsupervised Topic Modelling. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (CSCI), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 5–7 December 2019; pp. 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Hornik, K.; Grün, B. Topicmodels: An R package for fitting topic models. J. Stat. Soft. 2011, 40, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Korenčić, D.; Ristov, S.; Repar, J.; Šnajder, J. A Topic Coverage Approach to Evaluation of Topic Models. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 123280–123312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyvers, M.; Griffiths, T. Probabilistic topic models. In Handbook of Latent Semantic Analysis, 1st ed.; Landauer, T.K., McNamara, D.S., Dennis, S., Kintsch, W., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 427–448. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd-Graber, J.; Blei, D. Multilingual Topic Models for Unaligned Text. arXiv 2012, arXiv:1205.2657. [Google Scholar]

- Steves, M.; Greene, K.; Theofanos, M. Categorizing Human Phishing difficulty: A Phish Scale. J. Cybersecur. 2020, 6, tyaa009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashenden, D.; Sasse, A. CISOs and organisational culture: Their own worst enemy? Comput. Secur. 2013, 39, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khandelwal, S. Popular Period Tracking Apps Share Your Sexual Health Data With Facebook. The Hacker News, 12 September 2019. Available online: https://thehackernews.com/2019/09/facebook-period-tracker-privacy.html (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- CISO Kit—Breach Protection in the Palm of Your Hand. The Hacker News, 11 September 2019.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).