Abstract

Cities strive to feed growing populations while at the same time minimize the environmental impacts of their food systems. To support cities to achieve their goals, they require systematic and practical actions, including identification of the needs and capacities of food practitioners to guide and support food-related policies and initiatives. This study aims to explore barriers to food-related actions in everyday settings and the potential of a food pedagogy framework to overcome such barriers. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 39 experienced food leaders from diverse food-related areas in Australia. Thematic analysis identified six key themes related to weaknesses in food-related actions, including lack of: a broad understanding about food; acknowledgement of values of food in everyday lives; a broad pedagogical lens; a responsible entity; organizational supports; and coordination between stakeholders and communities. Existing national and global food initiatives were reviewed using a pedagogical framework to identify presence of these barriers to actions, together with strategies that aimed to avoid or diminish such barriers. The findings confirm that a pedagogical approach has potential to enhance the roles and capacities of food practitioners and provide support for government and community structures to achieve a common vision of healthy and sustainable urban food systems.

1. Introduction

Food is a fundamental part of our everyday lives, and we all eat food for life. Food is not just for personal health but has an important multifunctional role in society. Rapid urban growth and limited resources have brought about many major urban food challenges [1]. The growing food demand from urban populations puts further pressure on food systems, food security, and environmental degradation [2]. Global studies have indicated approximately one third of all food produced for human consumption every year is lost or wasted without being consumed, and most food consumption and food waste takes places in cities, particularly in high-income countries [3,4]. Urban food consumption processes or practices can cause high levels of food waste and environmental contamination, which are major contributions to climate change [5]. Additionally, urban lifestyles and unhealthy food environments, such as a higher demand for convenience, a diverse range of processed foods, packaged and ready-made foods outside the home, and higher prices for nutrient-dense foods, have led to dietary changes and increased the prevalence of overweight and obesity and the risks for non-communicable diseases [6,7]. Fast changes in lifestyles disconnect urban residents from the values of food we chose through traditional, cultural, and social contexts. Less attention is directed at how to obtain, process, store, prepare, share, and eat food in more sustainable ways in everyday lives [8,9,10].

To address these complex urban food issues, a growing number of cities around the world have reframed food as important for achieving urban health and more sustainable food systems [11,12]. Government organizations have begun to develop urban food policies/strategies and implement food-related activities with a wide range of stakeholders to create healthy and sustainable societies [5]. These food actions across cities aim to support individual and social health outcomes [13], improve access to healthy, affordable and culturally diverse food [14], and contribute to local economic growth and sustainable development [15]. The need for such food policies and initiatives has gained wide recognition [5,16].

How to enable people, including food practitioners, to understand and achieve the important outcomes from food actions, remains a challenge and is under-researched [17,18]. For example, international food initiatives, such as the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact [12], provide some guidance to the public and private sectors on the development and/or implementation of urban food policies/strategies. However, there is lack of attention to practical implementation. For example, they lack clarification of the roles and practices of different food practitioners, and the capabilities concerning the social, cultural, economic, and environmental aspects of food required for enactment of food-related policies/initiatives [19,20]. Such clarification is important, as food practitioners in the community do not systematically consider their educative roles. Community food leaders may increase their food leadership and impacts if they apply learning frameworks, pedagogies, to their food actions [21].

With respect to pedagogical approaches to food, Flowers and Swan [22] (p. 1) defined a broad concept of food pedagogies as “educational, teaching and learning ideologies and practices carried out by a range of agencies, actors, institutions and media which focus variously on growing, shopping, cooking, eating and disposing of food”. It emphasizes that teaching and learning processes involve a range of stakeholders, consumers, and physical spaces in daily life, proliferate values relating to food, and improve individual, community, and social lives, beyond the transmission of food knowledge and information [23,24,25].

The importance of pedagogical processes of food and how people learn are under-explored compared with the attention paid to ‘what to learn about food’ [18]. Research has a dominant focus on food literacy, that is, the importance of knowledge acquisition about food, for improving individuals’ healthy dietary behaviours and health outcomes or other food-related outcomes such as food security, sustainable food systems, or informed consumerism [26,27,28]. Another major focus of previous studies is school-based food education for children and adolescents regarding the content of school food literacy curricula [29,30] and the impact on dietary behaviours and health outcomes [31]. However, research is not focused on how to provide support or facilitate development of individuals’ perspectives or knowledge about food and food-related issues in broad social settings. A pedagogical approach has the potential to inform urban food actions in practice, raise awareness and acknowledgement of food and food system issues amongst individuals, communities, and policy makers, and improve existing food-related policies and initiatives for creating healthier and sustainable cities.

The current study explores community food leaders’ perspectives as to why food-related activities in everyday settings have not gained traction; that is, what are the barriers to food actions? The study addresses the research questions: What are the barriers to food-related activities in urban areas? In what ways can a food pedagogy framework pre-empt or address barriers to food-related activities, and inform food policies and food initiatives for urban societal health and sustainability?

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

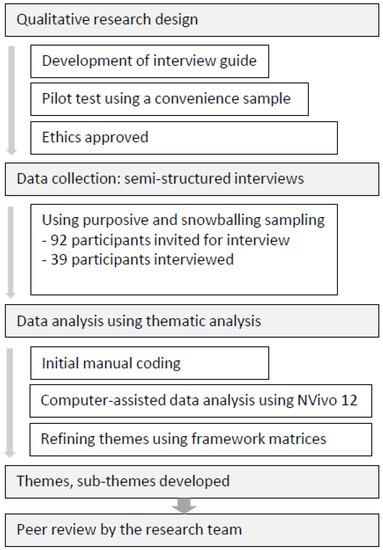

This qualitative study applied a semi-structured interview approach shown in Figure 1 to examine in-depth, the understanding of community food leaders’ viewpoints and experiences around the importance of food in everyday lives and how this can be effectively implemented in everyday settings [32].

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing the qualitative research procedure.

A qualitative research approach has been acknowledged as appropriate for developing new ideas or understandings about an issue or problem which has not been fully explained previously [33], and for improving or stimulating policies and programs solutions [32]. This approach is also primarily used to elicit information from participants who have unique perspectives or have highly specialized roles in society, such as public figures, leading professionals, or senior representatives of organizations [32]. These features of qualitative research aligned with the purpose of this research and the nature of the participants who play important roles in developing and/or implementing food-related activities as key food leaders.

2.2. Participants

Community food leaders with extensive experience and expertise in a diverse range of food-related fields in Australia were recruited via purposive and snowball sampling [33]. These food-related fields included food production, consumption, distribution, education, nutrition, food culture, public health, urban planning, environment, food media, food festivals, food business and hospitality, and policy development or implementation. Potential participants were identified through web-based investigation, the research team’s knowledge of experts in the field, and suggestions from initial interview participants. Potential participants were categorized into three occupation-related groups: government officials, chefs/food leaders, and academics. Participants were at a managerial level or above with several years of experience in food-related fields. An invitation letter for interview was emailed to 92 potential participants.

2.3. Interview Guide

The development of an interview guide was informed by previous literature [34,35]. Open-ended questions and relevant prompts (as necessary) were used to elicit detailed information from participants that fully reflected their views and experiences [32]. A pilot test of the interview guide was conducted using a convenience sample of four food practitioners engaged in food-related fields, to confirm coverage and relevance, as well as their understanding of the questions within the interview guide [36]. The order of the questions was reviewed and minor modifications to wording were made, with no deletions or additions of questions.

Examples of relevant open-ended questions include: (1) What do you think are the food-related matters your community/city are concerned about? (2) Thinking broadly and to the future, what do you consider are the key aspects of food and the food system that everyone should know about? (3) How is your local government encouraging local food-related activities? What do you think can be done to make food more of a priority/core business of local governments?

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Wollongong (approval No.: 2018/557).

2.4. Data Collection

Upon accepting the invitation to participate and prior to starting the interview, each participant was asked to read the participant information sheet and provide their written informed consent, as well as provide permission for the interview to be audio-recorded. Each participant was given a chance to clarify any questions relating to the research. Interview durations ranged between 30 and 70 min. Following the interviews, the audio recordings were transcribed verbatim. The first author reviewed and crosschecked all transcripts against the recordings for accuracy and made corrections if required.

2.5. Data Analysis

Thematic analysis was used to identify patterns and interpret features of the data with regard to the participants’ views and experiences [37]. To generate an initial coding framework with potential themes, the first transcripts from each group were analyzed manually. After the initial coding, the full set of data was imported into NVivo 12 software (QSR International Pty Ltd., Doncaster, Australia) to assist with the management of the analysis. Data were coded, themes were generated and refined from the initial coding framework, and new codes were included as they emerged [38]. Analysis went through an iterative and reflective process, including familiarizing with data via reading, generating initial codes, building potential themes, constructing refined themes, reviewing and defining themes, and producing reports of the data [39]. Framework matrices were constructed to summarize and display data systematically through each interview participant and each theme, and to get a more refined understanding of the content of the themes and the context in which themes occur across the whole data set [32]. Coding was completed by the first author and the identified themes were discussed and finalized with the research team. All authors reviewed, refined, and confirmed the identified themes [40].

3. Results

In total, 39 participants (5 male, 34 females) were interviewed through individual face-to-face (n = 11) interviews and phone/zoom interviews (n = 28): 9 government officials, 19 chefs/food leaders, and 11 academics. Nearly all participants actively engaged with diverse food-related activities in urban or peri-urban areas in Australia. The participants from city councils (n = 7) were all responsible for current urban food strategies or food initiatives’ development and/or implementation. Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of interview participants.

Overall, the participants suggested food policies or urban food strategies could be supportive of and a transparent system for advancing health and urban sustainability. However, they identified barriers to policy development or existing food initiatives, which can be categorized into six key themes. These six themes are presented under two main domains: Pervasive barriers and Structural barriers (Table 2). Participant quotations are labelled with pseudonyms.

Table 2.

Themes that related to barriers to food actions.

3.1. Pervasive Barriers

- (1)

- Lack of broad understanding about food

Many participants expressed a view that most people do not learn about food systematically and do not have an interest in food. They mentioned that people are unaware of or do not care about broader food-related issues such as where food comes from, social and cultural issues, the environmental impacts of food, and food sustainability.

“I think it’s from young now, we’re not getting taught where our food comes from in school systems, we’re not getting that kind of awareness and that connection with food in terms of where people made getting it from.… People need to be interested in food and probably need to see food as something that’s enjoyable and pleasurable too, and then go to the next step of looking at what impact is the food that I’m [eating is] having?”(Emilia, NGO program manager)

A range of participants also noted that government officials’ narrow perspectives and inadequate understanding of food-related matters produced food initiatives that did not align with multiple stakeholders’ views of and communities’ needs about food. They indicated more attention and effort by food policy/strategy decision-makers are required to enhance government officials’ capacities and expertise. Officials also need to recognize the importance of ensuring the broader aspects of urban food issues are reflected in their decision-making. Drawing on expertise in agriculture, social and cultural aspects of food, food systems, and sustainability is necessary to design, manage, and implement effective and locally relevant food strategies and food initiatives.

“The problem with the public service in Australia is that usually the people in the various public service jobs, they’re not content [food] experts in their subjects. They’re just process [administrating services] experts, but they get to make decisions about agriculture, … they don’t know anything about it. They only know industrial farming. So that’s why we have to keep turning up and helping them understand the alternatives to how food can and should be grown.”(Tessa, NGO president)

- (2)

- Lack of acknowledgement of values of food in everyday lives

Many participants mentioned that most people do not value the important roles food plays in their everyday lives. They referred to a disconnection between people and food, resulting in a lack of interest and appreciation of food, and in limited consideration of food’s values and its relationships in our lives.

“I think there’s such a strong disconnect at the moment between the food that people are eating and [people]. I think there’s no mindfulness around their food. You know, the vast majority just buy something quickly, cook it up and they don’t really think about it, they are eating it and even there’s just so many foods so that they are not really cooking much that cooking skills has been lost.”(Callie, City council official)

The disconnection between people and their food also extended to a lack of understanding and valuing of the complexities of the food system, reflecting that people in urban areas are often physically separated from the production of food.

“We go through this massive amount of food, and we forget how long it takes, how much effort it takes, and how much you’ve got to care for that thing before it even gets to your table. Because we’re not connected to our food cycle, we’ve lost that reverence for food. It’s no longer something that we’re very grateful for. It’s something that is just a commodity.”(Cali, Food culture academic)

Some participants from government organizations, as well as NGO managers, considered that key government actors had a narrow perspective regarding food that was a barrier to addressing food issues. They considered that government actors, particularly at executive and councilor levels, primarily valued food as a tool for improving the economic opportunities for a city. They had less interest in and under-valued the social and environmental aspects of food, such as public health and wellbeing, social and cultural roles, and sustainable lifestyles. The participants stressed it was important to incorporate broader perspectives, including food culture, into the development of food policies or strategies. They felt it was necessary to inspire policy makers to pay attention to and value food more broadly, including its tastes, pleasures, tradition and culture, intercultural exchanges, social integration, conviviality, and community engagement.

“Council has a food strategy. It’s quite hard to get momentum in Council when the food strategy’s not going to make money for Council. It hasn’t got any of those things where a councilor grabs onto it and says, ‘wow, this is a really fantastic strategy’.… Well, that’s possibly why I put that last pillar in [to the food strategy] around food culture.… [it’s] not something which in general [gets] a lot of interest amongst our counsellors and our executive.(Callie, City council official)

Participants indicated that the lack of practical food experiences within people’s daily lives and everyday interactions was a barrier to advancing food awareness. Practical experiences within people’s daily lives and everyday interactions with diverse people and in various spaces were considered important to acknowledge the value of food within people’s lives and their communities beyond the biological need for food. Creating more practical food interaction opportunities across the community would support development of people’s recognition of the relationships between the way they eat and their own health and the health of planet.

“By engaging the audience with meaningful content in a way that feels like an enjoyable cultural experience, we wanted them to feel positively about their food, to perhaps have a shift in thinking about their food choices. We wanted to give visitors discussion points so that they would talk about this content with people after the exhibition. We wanted visitors to see the relevance of this health information to their everyday life and not write it off as too science-y and just not for me.”(Julia, Food exhibition organizer)

- (3)

- Not thinking of food issues through a broad pedagogical lens

Participants indicated that efforts or opportunities for enabling adults to eat well and enjoy their food were not very visible within government organizations and across communities. They noted that most people, including food practitioners engaged in diverse food-related fields, did not recognize the pedagogical nature or processes of their involvement with food and its influence on themselves, communities, society and environmental health, and sustainability.

“A lot of small businesses actually do quite a lot, but they never say anything about it.… I also think that a lot of them don’t think they’re doing anything, but they’re actually doing quite a lot to make things better.”(Parker, Food social enterprise)

Some of the academics, NGOs, and city council officials stated that a lack of a focused food framework was a problem. Generally, food issues were informed by, and sat within, other frameworks such as nutrition, public health and wellbeing, food safety, agriculture, economics, and the environment. They considered it was critical to have a specific food framework that can assist adults in valuing food and learning about broader aspects of food within systems. For example, one participant highlighted the limitations of a nutrition framework.

“There’s no communication taught in nutrition degrees, No, none of that. There’s absolutely no gastronomy taught [about] how to create these meals and how to create a healthy meal. It’s [an] extraordinarily poorly conceived model.… it needs to change.”(Cali, Food culture academic)

3.2. Structural Barriers

- (4)

- No responsible entity

A key theme identified by many participants was that of there being ‘No responsible entity’ to provide leadership for addressing complex food-related issues. Participants shared a general understanding that food covers a range of areas including health and nutrition, agriculture, food production, consumption, disposal, and economy. However, there was no person/unit responsible for connecting these (policy) areas or for having a role in developing or implementing integrated food policies or initiatives within government organizations.

“We would like to see a food security strategy or policy platform. Because food security does not sit nearly anywhere in the government. Social services say it is health issues. Health says it is educational issues. Education says agriculture issues … or rural and regional infrastructure, you know. They keep passing it around, and no one will take responsibility for it.”(Samantha, NGO general manager)

The lack of leadership, responsibility, and political momentum was considered by some of the government participants and NGOs managers to lead to difficulties in executing food strategies or programs and for their ongoing support within government organizations. These participants indicated the importance of having a specific person/unit in place at government level who has a broad understanding of food and food-related issues, is able to manage food policies or initiatives, can take supportive actions, and has a strong political will for building healthy and sustainable societies. Participants believed the roles and perspectives of government actors, including city council officers charged with developing food strategies, city councilors, mayors, and politicians, are critical in executing food initiatives to address food-related matters. They emphasized the need for change, with different food perspectives driving the change within government organizations.

“If there’s not an individual who is advocating for or has expertise in the area, then it won’t get done. Or if there’s no pressure from elected representatives or from the community, then the work won’t get done, or it will just get done in the same way that it does. So I think, to drive change, we really do need people who’ve got skills and passion and expertise in the area.”(Vickey, City council official)

- (5)

- Organizational constraints within government organizations

‘Organizational constraints within government organizations’ were barriers identified by participants, including physical structures, accountabilities, practical issues, and higher level legislative frameworks.

Participants viewed government structures as siloes. They considered that government departments worked well within themselves but that a broad approach to food matters requires cooperation across different government units and departments, which is lacking. Compartmentalization of departments impacts the formulation and/or implementation of broadly conceived and integrated food policies and initiatives. They noted a need for an integrative approach whereby different government departments come together to create a holistic view of food in terms of food policy and food strategies development.

“It is very hard to work together and to try to work with all departments and bring everyone together. We need something that everyone comes together at the table.… I think with food and food strategies, you cannot just focus on agriculture, you cannot just focus on healthy eating. You have got to have everyone, … from growing to eating it.”(Ruby, Public health official)

In addition, participants considered that government structures did not reflect or embed the importance of food issues within their policies or strategies. Reflective of the lack of valuing food at the personal level, institutions also did not place importance on food in the same way it valued the economy, public safety, and basic public health issues. Thus, in addition to a lack of administrative structures responsible for food, there was a lack of accountability related to food matters.

The absence of supportive and transparent structures and lack of embedded valuing of food with associated administrative accountability hindered both the development of food policies or food initiatives and their continuity within city council institutions.

“To make real change … start influencing the system and start making this system different.… So for me, what’s important is that [a food-related activity] becomes [embedded] in the system. In the system then if I can go tomorrow, it’s still going to continue happening.… Because that’s when things become sustainable.… So we need something else, something else needs to go deeper in the fabric of how the system works. Once in there, it’s really hard to get out.”(Charlotte, City council official)

In addition, participants identified other practical structural constraints at the municipal level, including staff working on food-related activities who struggle with a lack of financial resources, limited staffing, and high workload.

Participants stressed the importance of overarching legislative approaches. One academic scholar emphasized the importance of creating an overarching legislative framework to secure and ensure broadly-based commitment to food matters from government. As an example, she commented, “Currently there isn’t any legislation to ensure that people have access to an adequate food supply in Australia. So, nobody is responsible for making sure communities have enough food.” Other participants indicated the need for creating supportive structures, such as laws, food policies or food strategies, with responsible city departments or units, to ensure coordination and consistency of work and to improve urban food-related issues pertinent to food security, health, social integration, local economies, and the environment.

“In terms of overall coordination [about food strategy/policy] I know we don’t have anybody in that.… I think it [a formal structure] is needed at either the state or the federal level to have [responsibility]. I don’t know if a Food Policy Council is the right thing. I’m not really across what the best contemporary model is. But I do think that we need some top-down support for … what is going to be unstoppable on the ground.”(Vickey, City council official)

Most of the participants, across all three groups of food-related experts, believed that supportive structures provide opportunities for people to increase awareness and interest about food and food systems.

“Government food policy would do something. Like if it [food] goes higher on the government agenda, more people will be aware that it matters. If it is not on the government agenda, then we are not going to foster a diverse good food system.”(Dior, public health academic)

- (6)

- Lack of coordination with stakeholders and communities

Many participants mentioned the challenges involved in working with all departments and bringing everyone together. These challenges reflected the institutional structures, with diverse food-related activities scattered across different government departments, as well as the existence of different groups in communities. They highlighted the need to ensure that the diversity of actors and their views were engaged in the process.

“[Food strategy] has to be broad because everyone eats. All the world, rich or poor, they’re all going to have some sort of interest and there’s many angles to it. So, the broader that engagement can be, the more diverse the views. So that’s something that now there’s been a lot more understanding of the need to engage.”(Jade, City Councilor)

Participants stressed the importance of cooperation between actors involved in food in the public and private sectors. They noted that government officials should have a commitment to connect, coordinate, and support more opportunities for all key actors to have their voices heard and to engage with food-related activities. One local government participant gave the positive example of the actions for her council.

“[XX council] has a food system strategy.… and that’s really going to set up a big framework for the region. It’s not just a city strategy but also … multi stakeholders. So we’ve got 32 different organizations and community groups that are on board that are going to lead through system actions over the next 10 years.… In terms of my position and officer level, I think it’s sort of a connecting role and coordination … connecting different groups, and sort of helping make sure that there’s not duplication going on, but we’re all actually working together within Council as well as externally, in linking up different stakeholders.”(Rachel, City council officer)

4. Discussion

This study is the first to report community food leaders’ perspectives on the barriers to advancing food initiatives and food policies within urban areas. Community food leaders recognize that a wide range of stakeholders play a role in addressing urban food-related issues, such as food insecurity, hunger, the increase of food-related chronic diseases, unsustainable urban food systems, and food-related impacts of climate change. They consider efforts or opportunities for enabling adults to value food and engage with broader food-related issues are not particularly visible within government organizations or in communities. They also identify multiple other barriers to advancing food issues in an effective manner.

The barriers to advancing food actions identified in this study are reflective of a range of previous research. Lack of attention to the topic of food within government institutions is identified by Muriuki et al. [41]. Lack of central authority and responsibility for the development and implementation processes of food policies or food initiatives is identified by the Commission for the Human Future [42] and Park et al. [43]. Lack of capacities of government actors for food policy implementation is identified by Reiher [44] and Doernberg et al. [20] as barriers to advancing policy issues.

Unique to this study is the identification of the importance of values of food. Food values refer to embracing interconnected social, cultural, political, agricultural, and environmental factors beyond economic value [45], and reflect individual thoughts, meanings, feelings, beliefs, and motives over life experiences [46]. Multiple values underpin food choices and influence food-related actions towards health and sustainable living [47,48]. The important role of the values of food within food policies and initiatives has not been highlighted in previous literature. Further research is required to explore the concept of the intrinsic values of food, such as what people perceive them to be, how people link individual health and a healthy environment, and how they may be nurtured and promoted through food policies or food initiatives.

Having identified the barriers to addressing food issues, it is important to consider how to overcome them. Three key areas require consideration—how the importance of food knowledge and values can be acknowledged; what strategies/frameworks may assist in preventing or overcoming the identified barriers; and what actions can embed food within government and community structures (refer to Table 3, column 2).

Table 3.

Three key considerations to overcome barriers to the implementation of food initiatives within urban settings.

The first key consideration arising from this study is the importance of inspiring people’s understanding and valuing of food within their daily lives and in their communities. The need to improve informed understanding and integrated perspectives of urban food matters is consistent with the concept of critical food pedagogies by Sumner [25], which aims to build critical food knowledge around food systems and sustainability for adults to address food-related issues and broader social issues. She acknowledges that food is intrinsic to life. This finding aligns with a previous study of a conceptual framework of food pedagogies, which emphasizes embracing social and cultural values of food into food policies and food initiatives [43].

The facilitation of practical experiences within daily lives enables people to engage with food, and realize the values of food related to pleasure, culture, social identities, healthy lifestyles, and sustainable food systems. This finding is consistent with other studies linking everyday interactions surrounding food with people’s motivation to engage with food, increasing their food knowledge, and promoting social, cultural, ethical, and environmental values, and sustainable food practices [24,49,50,51,52,53].

Previous research has documented the significance of raising knowledge of food matters, food literacy, for individuals or communities [27,54,55]. Yet, how government bodies and key food practitioners consider food-related values within food policies or food initiatives remains a gap in the literature [18]. A recent food strategy guidance document argues for strengthening the capacity of government actors and diverse stakeholders to advance information and knowledge about complex urban food matters [13]. However, little attention is given to the importance of valuing food within the development or implementation of food policies, food initiatives, or education programs. A previous study demonstrates that values-based practices can support food knowledge and skills and transmit more meaningful values to individuals’ and communities’ lives, including appreciation, consciousness, respect, and their relationships with food [56]. This finding suggests that in order to achieve wider and systematic changes for societal health and sustainability, the importance of food knowledge (food literacy) and the intrinsic values of food should be ‘taught’ and ‘nurtured’ together in a social context, as one component of pedagogical processes of food.

The second consideration of the findings is how to overcome these barriers to food-related actions. A recently developed food pedagogy framework [21] has potential relevance to address and embed resilience against the barriers when developing or implementing urban food initiatives. The framework utilizes a social perspective that encompasses everyday spaces, interactions with a range of people related to food, practical experiences, supportive systems, and engagement with social issues. To explore the potential of a food pedagogy framework, together with important food literacy outcomes (Table 4, column 1), a range of existing urban food strategies are reviewed in relation to recognizing or overcoming the barriers to action, as shown in Table 4, columns 2 and 3.

Table 4.

Reviewing existing urban food policies/strategies using the food pedagogy framework.

Food policies or food initiatives often reflect a strong focus on improving individual awareness-raising and information about food to change individuals’ behaviours for personal health benefits or a sustainable food system [5]. For example, Greater Bendigo’s food system strategy indicates poor food literacy issues as barriers to health and food security and it focuses on increasing individuals’ nutrition knowledge and food preparation skills in cooking and growing [57]. To overcome such barriers, the strategy proposes a collaborative, cross-sector, multi-stakeholder approach to achieve collective impacts to support, coordinate, and strengthen local food systems. However, there is limited attention paid to how, beyond nutrition and cooking/growing skills, critical food literacy is achieved in practice in community settings, or who could promote critical food knowledge. The document briefly mentions the cultural value of the region. However, there is little mention of initiatives to enhance key food practitioners’ practices or their understandings, perspectives, and attitudes towards the social, cultural or ecological aspects of food. This might be due to the absence of a broad pedagogical lens, which could assist food practitioners to consider their everyday food practices from a holistic approach and recognize their educational roles to transfer both knowledge and the valuing of food amongst urban residents.

As noted above (shown in Table 4, column 3), structural barriers also exist within government and other organizations. The report, “Proposal for sustainable urban food in the ACT (Australian Capital Territory)”, acknowledges the need for a responsible entity to take charge of food policy development and implementation [58]. It suggests developing an external governance structure, outside of government, with appointment of a central external expert to implement and coordinate an integrated food policy. However, the report overlooks the need for internal structural change within government organizations regarding leadership roles for government officials, administrative structural constraints, accountabilities, or practical issues for food policy implementation. Creation of an external agency may perpetuate the limited acknowledgement of the importance of food issues within government structures, identified as a barrier in this study. Alternatively, if systemic change within government is identified as a long-term goal, creation of an external agency may represent an interim step towards achieving this outcome.

A component of the broad pedagogical approach highlights that government officials and organizations have responsibilities for and capacities in the development or coordination of urban food policies and food initiatives. Lack of attention within urban food policies regarding government organizations and government officials, compared to a strong focus on food governance approaches dealing with multi-stakeholder engagement, has recently been identified as an issue by Doernberg et al. [20]. Food policies and many food initiatives rely on at least some level of government support. This reinforces the need to include structural considerations in a systematic approach to developing and supporting existing food policies or governments’/community organizations’ food actions, as detailed within the food pedagogy framework.

Lack of attention to the need for relevant infrastructure is also an issue with the international food initiatives. “The Milan Urban Food Policy Pact”, an international agreement signed by mayors of cities all over the world in 2015, aims to develop more sustainable food systems and promote healthy diets. More than 200 cities have signed this agreement [12]. It provides a working tool to help guide public and private sectors to develop and implement urban food policies and initiatives. Unfortunately, the diverse actors’ roles, responsibilities, and capacities for implementing food practices and engaging communities in food issues is underdeveloped in the document [19], potentially undermining the effectiveness of this important food policy initiative.

Other food policy initiatives do reflect more components of the broad pedagogical approach, including the need for government and organizational structures. The Nordic national food policy report, “Solutions Menu”, highlights the importance of an overarching and integrated infrastructure to underpin the interactions between top-down and bottom-up approaches and the imperative to embrace policy makers, organizations, and private sectors to coordinate food initiatives [35]. Within the supportive systems, food culture and gastronomy are core, to be learned and shared together with all stakeholders in their everyday lives. The initiative includes raising awareness and values of food together, to address health, social, economic, and environmental issues.

One important component of pedagogical actions for developing supportive systems is government actors’ roles and their responsible leadership around broader perspectives of food. This can help inform awareness about food and food system issues amongst urban communities and adequately execute and manage the processes of food policies or food initiatives [44,59]. Another important consideration is the need to change organizational structures to be supportive and transparent. There is limited evidence of integrated structures or frameworks for food systems such as legislation, bureaucratic structures to coordinate existing policies and programs or support for stakeholders and communities [42]. Such structural changes could systematically help inform government/non-government organizations and community food-related actions, reinforce relationships between governments and communities, and ensure accountabilities of food practitioners to create healthy and sustainable food systems [20,59].

Use of the components of a food pedagogy framework to review existing food policies and strategies highlights examples of how existing initiatives pre-empt or overcome the barriers to action identified in this study. However, no one initiative addresses all issues that act as barriers. Use of a food pedagogy framework during the development and planning of urban food policies and programs may provide a systematic and broad perspective that contributes to the future success of urban food actions.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, this study explored the importance of barriers to food initiatives for adults in community-based settings from the perspective of a variety of community food leaders. However, other fundamental barriers for advancing urban food policies and food initiatives may have been missed, such as the influence or lack of school-based food education systems including home economics and health education. Future research could explore how a food pedagogy framework can build on and/or inform school-based food initiatives. Second, barriers to food-related actions and a proposition for the relevance of a food pedagogy framework to overcome these barriers with four existing urban food strategies were explored. However, the proposed framework has not been utilized in practice. Future case studies in urban settings are needed to demonstrate the application of the food pedagogy framework, with consideration of diverse food practitioners and different pedagogical spaces in communities. Third, the purposive sampling used in this study led to limited diversity in terms of groups within the food system, as well as in gender representation, with few male participants interviewed. As such, the data were analyzed as a collective, rather than by gender or other descriptive participant characteristics. Future studies should seek a broader base of community food leaders in other areas of food systems, which also may include more male food leaders. For example, leaders in the agriculture industry, food manufacturing, food technologies, particular cultural groups, and politicians in local/state/federal government organizations, may have influence over or provide further insights into the implementation of food pedagogies within urban settings.

5. Conclusions

This study identified barriers to food-related actions to address complex urban food issues. Importantly, it highlighted that food policies and practices need to consider both the values of food and food knowledge. Additionally, the study found that a food pedagogy framework can provide a systematic approach to review the extent to which existing food policies and initiatives incorporate measures to prevent or minimize these barriers to food-related actions. Application of a food pedagogy framework may strengthen current food policies/strategies and responsible government organizational structures to create a shared vision of healthy and sustainable urban food systems and to advance urban food actions. An implication of the findings is that key food practitioners, particularly policy makers, government officials and government organizations should consider themselves as food leaders, as well as co-learners and food pedagogues. They have key roles to create and sustain broad understandings about food, nurture meaningful valuing of food, and create more sustainable relationships with food across urban societies. Future research is needed to explore the potential contributions of food pedagogy frameworks—for example, how a food pedagogy framework can build on food learnings within school education systems. Future case studies could also apply a food pedagogy framework in diverse community-based learning environments, such as public spaces, food festivals, and urban pop-up structures, to provide insights into how diverse food environments and practitioners can contribute to creating healthy sustainable societies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.J.P., H.Y., J.R. and C.M.; methodology, S.J.P., H.Y., J.R. and C.M.; data collection, S.J.P.; formal analysis, S.J.P.; writing—original draft manuscript, S.J.P.; writing—review & editing, S.J.P., H.Y., J.R. and C.M.; visualization, S.J.P. and H.Y.; supervision, H.Y., J.R. and C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was provided for the research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of University of Wollongong (approval No.: 2018/557, 11 Dec 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants in this study who contributed their time for the interviews.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- Jennings, S.; Cottee, J.; Curtis, T.; Miller, S. Food in an Urbanised World: The Role of City Region Food Systems in Resilience and Sustainable Development; International Sustainability Unit (ISU): Rome, Italy, 2015; Available online: http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/FCIT/documents/Food_in_an_Urbanised_World_Report_DRAFT_February_2015.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2018).

- IFPRI. 2017 Global Food Policy Report; International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI): Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Food Wastage Footprint: Impacts on Natural Resources. Available online: http://www.fao.org/docrep/018/i3347e/i3347e.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Garcia-Herrero, I.; Hoehn, D.; Margallo, M.; Laso, J.; Bala, A.; Batlle-Bayer, L.; Fullana, P.; Vazquez-Rowe, I.; Gonzalez, M.; Durá, M.J.F.P. On the estimation of potential food waste reduction to support sustainable production and consumption policies. Food Policy 2018, 80, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, C.; Bricas, N.; Conaré, D.; Daviron, B.; Debru, J.; Michel, L.; Soulard, C. Designing Urban Food Policies: Concepts and Approaches; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global Report on Urban Health: Equitable Healthier Cities for Sustainable Development; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes, C.; Harris, J.; Gillespie, S. Changing diets: Urbanization and the nutrition transition. In 2017 Global Food Policy Report; International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI): Washington, DC, USA, 2017; pp. 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, E.; Cockx, L.; Swinnen, J. Culture and food security. Glob. Food Secur. 2018, 17, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Savin, P.; Alecsandri, V. Romanian traditional food heritage in the context of urban development. In Globalization Intercultural Dialogue: Multidisciplinary Perspectives; Arhipelag XXI Press: Târgu-Mureş, România, 2014; pp. 920–923. [Google Scholar]

- Barilla Centre for Food & Nutrition. The Cultural Dimension of Food; Barilla Centre for Food & Nutrition: Parma, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, K.; Sonnino, R. The urban foodscape: World cities and the new food equation. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MUFPP. Milan Urban Food Policy Pact. Available online: https://www.milanurbanfoodpolicypact.org/the-milan-pact/ (accessed on 8 July 2021).

- Tefft, J.; Jonasova, M.; Adjao, R.; Morgan, A. Food Systems for an Urbanizing World; World Bank Group, FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cavicchi, A.; Stancova, K. Food and Gastronomy as Elements of Regional Innovation Strategies; European Commission, Joint Research Centre, Institute for Prospective Technological Studies: Seville, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- De Cunto, A.; Tegoni, C.; Sonnino, R.; Michel, C.; Lajili-Djalaï, F. Food in Cities: Study on Innovation for a Sustainable and Healthy Production, Delivery, and Consumption of Food in Cities; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tegoni, C.; Licomati, S. The Milan Urban Food Policy Pact: The potential of food and the key role of cities in localizing SDGs. JUNCO J. Univ. Int. Dev. Coop. 2017, 1, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J.P. Towards post-industrial foodways: Public pedagogy, spaces, and the struggle for cultural legitimacy. Policy Futures Educ. 2019, 17, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Yeatman, H.; Russell, J.; MacPhail, C. Food pedagogy-key elements for urban health and sustainability: A scoping review. Appetite 2022, 168, 105672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cretella, A. Alternative food and the urban institutional agenda: Challenges and insights from Pisa. J. Rural. Stud. 2019, 69, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doernberg, A.; Horn, P.; Zasada, I.; Piorr, A. Urban food policies in German city regions: An overview of key players and policy instruments. Food Policy 2019, 89, 101782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Yeatman, H.; Russell, J.; MacPhail, C. Creating food learning opportunities for adults within daily lives: A framework for food pedagogies. CHERP, 2021; under review. [Google Scholar]

- Flowers, R.; Swan, E. Food pedagogies: Histories, definitions and moralities. In Food Pedagogies; Flowers, R., Swan, E., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Flowers, R.; Swan, E. Introduction: Why food?: Why pedagogy?: Why adult education? Aust. J. Adult Learn. 2012, 52, 419–433. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F.; Moskwa, E.; Gifford, S. The restaurateur as a sustainability pedagogue: The case of Stuart Gifford and Sarah’s Sister’s Sustainable Café. Ann. Leis. Res. 2014, 17, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, J. Learning to eat with attitude: Critical food pedagogies. In Food Pedagogies; Flowers, R., Swan, E., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 201–214. [Google Scholar]

- Begley, A.; Paynter, E.; Butcher, L.; Dhaliwal, S. Examining the association between food literacy and food insecurity. Nutrients 2019, 11, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cullen, T.; Hatch, J.; Martin, W.; Higgins, J.; Sheppard, R. Food Literacy: Definition and Framework for Action. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2015, 76, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidgen, H. Food Literacy: Key Concepts for Health and Education; Vigeon, H., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nanayakkara, J.; Margerison, C.; Worsley, A. Food professionals’ opinions of the Food Studies curriculum in Australia. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 2945–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadegholvad, S.; Yeatman, H.; Parrish, A.M.; Worsley, A. What Should Be Taught in Secondary Schools’ Nutrition and Food Systems Education? Views from Prominent Food-Related Professionals in Australia. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ronto, R.; Ball, L.; Pendergast, D.; Harris, N. Adolescents’ perspectives on food literacy and its impact on their dietary behaviours. Appetite 2016, 107, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.; Lewis, J.; Nicholls, C.; Ormston, R. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers; Sage: Los Angeles, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hesse-Biber, S. The Practice of Qualitative Research, 3th ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes, C.; Halliday, J. What Makes Urban Food Policy Happen? Insights from Five Case Studies; International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Halloran, A.; Fischer-Møller, M.; Persson, M.; Skylare, E. Solutions Menu: A Nordic Guide to Sustainable Food Policy; Nordic Council of Ministers: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kallio, H.; Pietilä, A.; Johnson, M.; Kangasniemi, M. Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 2954–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 12, 297–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological; APA Handbooks in Psychology®; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Terry, G.; Hayfield, N.; Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic analysis. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2nd ed.; Willing, C., Statinton-Rogers, W., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2017; pp. 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, H.; Smith, J. Issues of validity and reliability in qualitative research. Evid.-Based Nurs. 2015, 18, 34–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muriuki, G.; Schubert, L.; Hussey, K.; Roitman, S. Urban Food Systems–A Renewed Role for Local Governments in Australia; The University of Queensland: Brisbane, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Commission for the Human Future. The Need for a Strategic Food Policy in Australia; The Commission for the Human Future: Canberra, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Yeatman, H.; Russell, J.; MacPhail, C. Key aspects of food-related activities for developing a conceptual framework of food pedagogies–Perspectives from community food leaders in Australia. FCS, 2021; under review. [Google Scholar]

- Reiher, C. Food pedagogies in Japan: From the implementation of the Basic Law on Food Education to Fukushima. Aust. J. Adult Learn. 2012, 52, 507–531. [Google Scholar]

- Prentice, G.; Peters, D. The Role of Values in Food Choice Behaviors; The World of Food Ingredients: Arnhem, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Monterrosa, E.; Frongillo, E.; Drewnowski, A.; Pee, S.; Vandevijvere, S. Sociocultural Influences on Food Choices and Implications for Sustainable Healthy Diets. Food Nutr. Bull. 2020, 41, 59S–73S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuts, F.; Mol, A. What is a good tomato? A case of valuing in practice. Valuat. Stud. 2013, 1, 125–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, J. Food Values: The Local and the Authentic. Crit. Anthropol. 2007, 27, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcan, R. Back to the Future: Australian Suburban Chicken-Keeping as Cultural Pedagogy and Practice Revival. Locale Aust.-Pac. J. Reg. Food Stud. 2018, 7, 15–44. [Google Scholar]

- Dyen, M.; Sirieix, L. How does a local initiative contribute to social inclusion and promote sustainable food practices? Focus on the example of social cooking workshops. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajzer Mitchell, I.; Low, W.; Davenport, E.; Brigham, T. Running wild in the marketplace: The articulation and negotiation of an alternative food network. J. Mark. Manag. 2017, 33, 502–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shani, A.; Belhassen, Y.; Soskolne, D. Teaching professional ethics in culinary studies. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 25, 447–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morone, P.; Falcone, P.M.; Imbert, E.; Morone, A. Does food sharing lead to food waste reduction? An experimental analysis to assess challenges and opportunities of a new consumption model. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 185, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, J. Food literacy: A critical tool in a complex foodscape. J. Fam. Consum. Sci. 2017, 109, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, J. Reading the world: Food literacy and the potential for food system transformation. Stud. Educ. Adults 2015, 47, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brien, D.L.; McAllister, M. ‘Sunshine has a taste, you know’ Using regional food memoirs to develop values-based food practices. Locale Aust.-Pac. J. Reg. Food Stud. 2015, 5, 32–57. [Google Scholar]

- City of Greater Bendigo. Greater Bendigo’s Food System Strategy 2020–2030; City of Greater Bendigo (CGB): Bendigo, Australia, 2020.

- RDA ACT. Proposal for Sustainable Urban Food in the ACT. Available online: https://www.agrifood-hub.com/sustainableurbanfood.html (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Van de Griend, J.; Duncan, J.; Wiskerke, J. How civil servants frame participation: Balancing municipal responsibility with citizen initiative in Ede’s food policy. Politics Gov. 2019, 7, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).