Abstract

Following the fall of the socialist regime, Central and Eastern Europe’s cities underwent a systemic transformation that was greatly influenced by internationalization and globalization. Due to their EU membership, these cities could also access structural development funds, which had an important impact on how urban restructuring has proceeded in recent years. In this article, we analyze both the data and the opinions of various actors concerning social resilience aspects in regeneration strategies employed in Polish cities related to the political shock of the systemic transformation and the consequences of this process. Particular emphasis is on linking these policies with the former character and changes in the social and physical and environmental structure of historic districts. The city of Poznań, which is considered a forerunner of regeneration in Poland, was chosen as a case study. Strategies related to improving the condition of buildings and land use have been successfully implemented, although they have sometimes attracted criticism from climate change activists, while those related to improving the living situation of people living in regenerated areas have failed. Urban regeneration resulted in the gentrification and few social benefits were obtained. Regeneration efforts have not achieved possible outcomes in terms of social resilience.

1. Introduction

After the fall of the socialist regime, cities in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) experienced a political shock of systemic transformation that was significantly influenced by internationalization and globalization. Due to their EU membership, these cities could access structural development funds, which had an important impact on how urban restructuring has proceeded in recent years [1]. This has led to a reorientation of strategic policy and the establishment of a legal framework for comprehensive urban regeneration [2]. The regeneration initiatives were often undertaken in centrally located historic districts [3]. This is due to the “repair gap” from the socialist era, which has led to technical and environmental degradation. This is accompanied by the rapid depopulation of the centers, and a drain of young people that leads to the rapid aging of the inner cities [4]. The observed shock has resulted in more than 55% of Poland’s problem areas being located in inner-city areas (Statistics Poland, GUS). As a result, urban regeneration is one of the main challenges for the contemporary development of CEE cities, especially in densely built-up central areas [5].

In this article, we analyze both the data and the opinions of various actors concerning social resilience aspects in regeneration strategies employed in the historic districts in Polish cities related to “stressor”, which were the shock of the systemic transformation and the consequences of this process. Particular emphasis is on linking these policies with the former character and changes in the social-economic and physical-spatial and environmental structure of historic districts. With this work, we aim to fill a gap in the research on CEE countries. The literature on the post-communist city has so far failed to offer a theoretical engagement with the notion of social resilience, and the resilience concept has failed to adequately consider issues of post-communist transformation [6].

The paper is divided into five sections. After the introduction, we presented a theoretical framework for our work. In this section, we presented social resilience concept, the idea of resilience strategies, and the specifics of regeneration strategies developed and implemented in CEE. We then described the materials and research methods. The analysis was conducted at two levels—national and local. The city of Poznań, which is considered a precursor of regeneration in Poland, is chosen as a case study. Since 2006, six urban regeneration programs have been implemented there, with varying results. They provide a good basis for assessing the Polish city’s resilience in terms of regeneration efforts. In the next part, we have identified manifestations of resilience policies on national and local levels. The article ends with a discussion and conclusion, in which we summarize the collected research results and compare them with studies from other works.

2. Theoretical Frameworks

2.1. Social Resilience Concept

The academic application of the term and the concept of resilience dates back several decades in psychology and sociology, but the resilience of ecological systems is seen as the source of modern resilience theory [7,8]. It was here that the nomenclature, prevalent in research on various dimensions of urban resilience, was developed [9]. As a result, the general definition of urban resilience has some environmental references: ability to maintain human and ecosystem functions simultaneously over the long term, even during a disaster or crisis, and the capacity to deal with sudden change and continue to develop [10,11]. The same is true for the social resilience of cities. The social resilience paradigm is part of an expanding scientific attempt to assess the ability of cities around the world to transform their political, economic and technical structures in line with the demands of a more demanding environment in the future [6,12,13,14]. It can be also defined as the ability of communities to withstand external shocks to their social infrastructure [15].

The general resilience concept is rooted in and dominated by ecological systems thinking, however, social resilience departs from the general resilience discourse by adopting an actor-oriented perspective [16]. It addresses issues such as:

- (1)

- Individual natural hazards and disasters, related to climate change; see, e.g.: [17,18,19];

- (2)

- Long-term stress related to natural resource scarcity and environmental variability; see eg.: [15,20,21];but also:

- (3)

- Social change, institutional change, and development issues, see eg.: [6,22,23].

These studies typically use social resilience as a guiding concept, which is further adapted to the issue under study.

The study emphasizes that social resilience is strongly influenced by institutions and networks that enable people to access resources, learn from experiences and develop constructive strategies for dealing with common problems [24]. As a result, social resilience is institutionally determined because institutions permeate all social systems and institutions fundamentally determine the economic system in terms of its structure and distribution of assets ([15]. At the same time, social resilience has to provide a suitable answer to the question of the interplay between social structures and the agency of social actors [25].

2.2. Resilience Strategies

Urban resilience requires new planning strategies and procedures that transcend conventional planning approaches by integrating uncertainties into the planning process and prioritizing stakeholders’ expectations [26]. Strategies should be also flexible enough to quickly adapt to rapidly changing environments [27]. Studies [28] point to various disruptive signals (“stressors”) for which resilience strategies are built, and the consequences that may occur due to the action of a given stressor. Among the stressors indicated are: (1) natural: disasters such as hurricanes, earthquakes, tsunamis; (2) technological: problems occurring on the side of complex technical systems; (3) social: include intentional acts that can harm cities, such as acts of terrorism, war, crime, riots; and (4) economic: the deterioration of the economic outlook and the end of the prosperity. Especially the latter should be considered important from the point of view of the changes observed in CEE. They are usually caused due to declines in job prospects, rising poverty, deteriorating housing and infrastructure, the exit of businesses, and poor investment in the future by local government agencies [29]. The above problems occurred in the first years of systemic transformation and also formed the basis for regeneration efforts. However, it is worth noting that sometimes economic stressors can also be exogenous factors, such as a global recession that affects the flow of resources to local companies, institutions, and people [30].

The action of stressors can lead to various situations: (1) destruction, which is the permanent loss or incapacitation of any of the city’s components or the network links that connect the components, (2) decline, which is the gradual aging of a city component, making it less able to function or survive in its environment, or (3) disruption—component disruption is common and often included in traditional infrastructure management, disaster recovery and emergency management plans. All of the situations described can have serious consequences for a city, some of which may not be reversible [28]. There are three action sets in resilience strategies where urban planners, policymakers, and citizens can participate in building resilient cities:

- (1)

- Planning: this involves building greater resilience capacity by creating plans that are flexible and can keep up with a rapidly changing environment; plans should also be responsive to change as new information and events emerge during the process;

- (2)

- Designing related to the implementation of planned activities, which means designing physical (e.g., buildings) or logical (e.g., policies) artifacts; focusing on adaptability will ensure that the planning results achieved can be reused, stretched, and even modified in times of stress;

- (3)

- Governance, which includes the set of decisions and actions we take in times of normalcy and in times of crisis that affect the current and future state of various elements of the city [28].

The above measures make up the strategy for building urban resilience. For their success, however, public participation is necessary. This is because social capital plays a key role in building and maintaining (social) resilience [31]. It is crucial to assess the involvement of social actors in particular sets of actions to build the city’s resilience and the impact of these activities on the life of local neighborhoods.

2.3. Urban Regeneration in CEE

Following the fall of state socialism, the “Western approach” (The evolution of the “Western approach” to regeneration is described, for example, in the works of [32,33,34]. The contemporary “Western approach” to regeneration is described as a comprehensive form of policy and practice; there is emphasis on integrated policy and interventions.) to strategic planning and urban regeneration, with its holistic and integrative approach to development, began to dominate the evolving policies and management practices of post-socialist cities [35]. This resulted from understanding urban development not only as physical and spatial, but also social, environmental, and economic. Therefore, it naturally responds to the need for a planning mechanism capable of addressing the challenges facing post-socialist cities [36]. Authors [37] (p. 17), define urban regeneration as: “a comprehensive and integrated vision and action that leads to the solution of urban problems and that aims to bring about a lasting improvement in the economic, physical, social and environmental condition of the area that has undergone a change.” Of course, urban regeneration takes place under different conditions. Consequently, regeneration strategies are not identical and do not produce the same results. This is particularly evident when comparing regeneration efforts in Western Europe and post-socialist countries [38].

To be successful, urban regeneration requires, in addition to resources, the cooperation of a wide range of organizations, communities and individuals who work together and share a common vision and goals. As [39] notes, the range of actors involved varies from case to case, but typically includes central government, local government, the private sector, the community, the voluntary sector, and residents. Since the 1980s, the partnership model has been dominant in regeneration in Western European countries. As [40] points out, the multidimensional and complex nature of urban problems requires integrated, coordinated, and comprehensive strategies involving a wide range of actors. On the other hand, numerous examples prove that “Western approaches” to regeneration do not always fit in [41,42,43,44]. Ref. [41] argues that this is due to the lack of cooperation between stakeholders and the central government’s key role in urban planning. Ref. [45] emphasize the difficulty of community involvement due to the lack of initiative from local leaders and decision-makers in the revitalization process. The above conditions significantly affect the nature of social resilience in urban regeneration.

3. Materials and Methods

We used the original methodological approach in this study, following the mixed-methods research concept [46]. It involved desk research, supported by quantitative and qualitative content analysis.

We first analyzed regeneration strategies across the country. The object of our particular interest was to highlight key social and environmental aspects from the perspective of building urban resilience at the stage of programming, implementing, and monitoring of the regeneration process. We presented key information on the regeneration strategy, including the importance of each sphere (based on the opinions of local leaders), the actors involved in the process, and participatory methods for including a wide range of change actors. The basis for the analysis was data from Statistics Poland (GUS—Główny Urząd Statystyczny) for 2019. Then, we screened policy documents and grey literature to compile up-to-date background information on urban regeneration in Poznań. We analyzed various urban regeneration programs, including Poznań’s GPR (Gminny Program Rewitalizacji dla Miasta Poznania), a city’s regeneration strategy, and information provided by the municipal authorities in reports on regeneration activities in the period from 2006 to 2020. Next, aiming at a first-hand assessment of regeneration’s spatial, technical, social, economic, and environmental effects, we conducted the site inventories in regenerated areas. Following this, to gain deeper insights into regeneration effects and practices, we used the purposive sampling method [47]. Long-term and active involvement in the regeneration process was a requirement for selecting participants for the sample. Most interviewees have a political or economic interest in the neighborhoods being regenerated. Observing the process of ongoing transformation, between March 2017 and August 2022, we conducted ten individual in-depth interviews. They were carried out with individuals representing diverse social groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Individuals who were interviewed in-depth.

The interviews lasted between 30 min and 1 h and 15 min and were recorded. The questionnaire consisted of 14 questions related to diverse aspects of regeneration. During these talks, we asked the participants how they perceive regeneration policy in Poznań, also from the point of view of building the city’s resilience. One of our primary goals was to understand their impressions of regeneration’s impact on the local community, spatial development, quality of build-up, and natural environment, as well as property values. As it turned out that the process greatly affected the social structure of the regenerated areas, in our later rounds of interviews, we specifically reached out to those responsible for social issues and representatives of the city administration to acquire an accurate understanding.

4. Results

4.1. Poland

In the post-transition period of 1990, regeneration projects in Poland were unplanned and chaotic, as there was no coherent vision for urban development. The process in that period assumed only physical change of degraded areas, leaving aside issues related to solving social and economic problems. The key to changing this situation was the accession to the European Union in 2004. Cities received organizational and financial support, which in subsequent years initiated systemic changes at the national level. Today, urban regeneration is an important element of state policy, as reflected in the national Strategy for Responsible Development, the National Regeneration Plan, and Poland’s Reconstruction and Resilience Plan [48]. In addition, the Regeneration Act was adopted in 2015, which creates a solid legal framework for the transformation of degraded urban areas. Since 2015, emphasis has been placed on a comprehensive approach to regeneration. It distinguishes between activities in the social sphere (taken as a starting point, related to unemployment, poverty, crime, and access to culture and education), environmental sphere (related to the quality of the environment and adaptation to climate change), economic sphere (related to the level of entrepreneurship and growth of the local economy), functional-spatial sphere (focused on the functional development of space) and technical sphere (focused on the modernization of buildings). The primary source of support for regeneration in Poland is European Union funds channeled in the form of grants to local governments, as well as in the form of low-interest loans for entrepreneurs (JESSICA Initiative). The total value of regeneration activities planned in the current programming period, i.e., 2014–2023 in Poland exceeds EUR 11 billion [49].

At the end of 2019, more than 53% of municipalities had prepared regeneration strategies (usually they were regeneration programs, in much rarer cases documents on development in general, which included regeneration in part). When urban municipalities alone are considered, the figure is even higher at 69%. In total, almost 10% of the country’s area has been declared a degraded area. The area is inhabited by more than 8.3 million people, i.e., slightly more than 20% of the country’s population. As was mentioned at the outset, 55% of these areas are located in the inner city. Regeneration strategies should therefore be seen as a fundamental tool used at the local level to build urban resilience in Poland.

At the local level, city governments are responsible for managing regeneration. They prepare regeneration strategies and involve, as appropriate, other stakeholders in regeneration activities. One of the forms in which this can take place is Regeneration Committees, advisory bodies to local authorities, which should consist of regeneration stakeholders: residents, entrepreneurs, and NGO representatives. They are mandatory if local governments want to use additional organizational and legal instruments to accelerate regeneration, which are listed in the Regeneration Act, i.e., additional sources of funding. At the end of 2017, Committees had been established in about 51% of municipalities where regeneration programs were in place. When we consider the static data, the Regeneration Committees were only partially composed of social stakeholders: 23% were residents, 15.5% were representatives of NGOs, and 9% were entrepreneurs. More than half of the members were officials of various units, city, and neighborhood councilors. Theoretically a social body, it was therefore dominated by people with professional ties to development and regeneration.

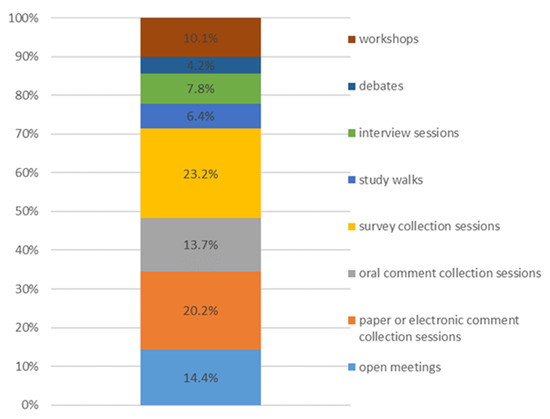

Another important element in evaluating regeneration strategies in Poland is also the level and nature of public involvement. According to current regulations, the preparation of each regeneration program should use a minimum three methods of participation. The choice of specific methods is largely left to local governments. As a result, taking the ladder of [50] into account, only about 22% of the methods can be considered as methods indicative of actual citizen control (workshops, debates, interview sessions) (Figure 1). Simple forms dominated, related only to informing residents or simple consultation, through the collection of surveys—either on paper or electronically, the collection of oral comments and non-binding study walks.

Figure 1.

Participatory methods used in drafting regeneration strategies. Source: own elaboration based on Statistics Poland (GUS).

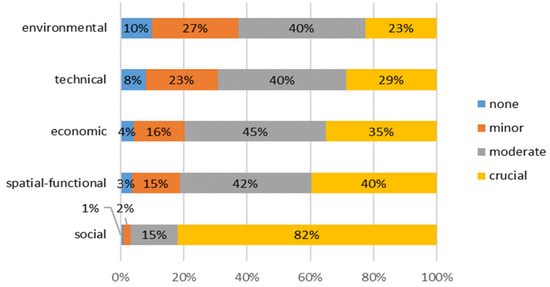

An important part of building a regeneration strategy is to define the boundaries of the regeneration area, where the recovery activities will be carried out. The social sphere was considered key in Poland when identifying an area for regeneration, which is important for building social resilience. As many as 82% of local leaders considered it crucial, and another 15% considered it moderately important. The environmental sphere is quite different. It is undervalued by respondents. As many as 10% consider it completely unimportant and another 27% consider it of little importance. In the opinion of only 23% of respondents, it is crucial. As a result, environmental aspects are described as the least important among all five spheres into which problems in areas in need of regeneration in Poland are divided (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The importance of each sphere in indicating the area for regeneration. Source: own elaboration based on Statistics Poland (GUS).

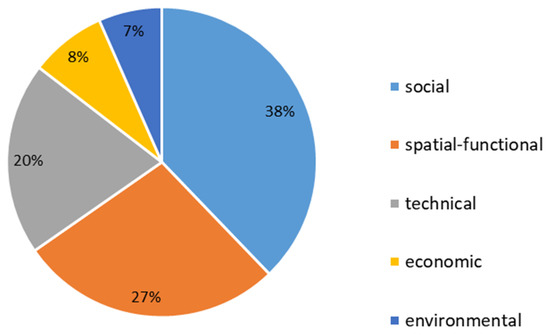

The situation is similar when one considers the projects envisioned for implementation in regeneration strategies. As many as 38% of all projects are activities that will primarily solve the diagnosed social problems. This is followed by spatial-functional, technical and economic problems. Environmental aspects are the rarest focus of ongoing regeneration projects (they account for only 7% of all activities) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Types of projects in regeneration strategies. Source: own elaboration based on Statistics Poland (GUS).

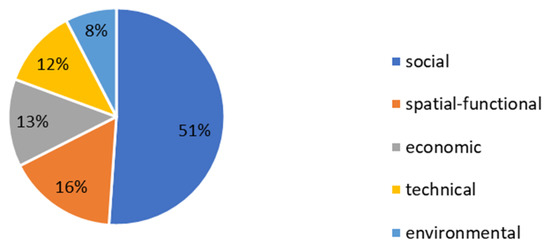

Very important from the point of view of regeneration efficiency is the monitoring stage. It allows for the evaluation of measures taken and their possible correction. This is to ensure as much planning flexibility as possible, which is in line with building strategies that are resilient to (unexpected) changes. In Poland, the regeneration monitoring system is still under construction, but an extremely important role is currently being given to it. Its development is mandatory for every regeneration program. In terms of indicators for monitoring, similar trends are observed to those of the stage of diagnosis and implementation of activities. Social indicators were most often chosen for monitoring, accounting for 51% of all indicators (Figure 4). Spatial-functional, economic and technical indicators were used with much lower frequency (12–15% of cases). By contrast, environmental indicators were by far the least frequently chosen (8%).

Figure 4.

Types of indicators used to monitor the effects of regeneration. Source: own elaboration based on Statistics Poland (GUS).

The above data collected at the national level allow us to identify several characteristics of the Polish approach to regeneration, which may have implications for building community resilience strategies:

- (1)

- A systematized approach to regeneration, its strong institutionalization, associated with clear, legal regulations, however limiting to some extent bottom-up initiatives;

- (2)

- The universality of regeneration strategies and their key role in the process of building resilience at the local level;

- (3)

- Comprehensiveness of regeneration strategies, with special attention to social aspects (unemployment, crime, poverty, low levels of education), which are considered to have been most affected by the shock of the transformation and decline of urban centers;

- (4)

- Largely posed public participation in regeneration. Although Regeneration Committees have been established among local communities, they are dominated by officials rather than local leaders. In addition, simple methods of public participation are being used, which have little effect on actual citizen control.

4.2. Poznan

Regeneration efforts in Poznań were initiated in 2005. They resulted, on the one hand, from the emerging socio-economic and spatial problems of the city, and on the other hand, an important reason was the possibility of funding urban development from the European Union. In the following years, successive regeneration strategies and programs were developed and implemented, related to the idea of step-by-step renewal, planned as a long-term process of successive changes. The entire historic district of the city was considered degraded, with a high concentration of socio-economic (high unemployment, poverty) and spatial (poor technical condition of buildings) problems. Undoubtedly, these phenomena were accompanied by environmental problems, but they were not described by indicators. The projects implemented included the following areas:

- − Large-scale investments, related to the renovation of the city’s main streets, improving accessibility to public transportation, building a bridge to improve the connectivity of regeneration areas, building museums and cultural centers, regenerating riverside areas along the Warta River, and renovating municipal housing stock;

- − Initiatives to integrate and activate local communities, involving the organization of periodic meetings, cultural events, concerts, exhibitions, theatrical performances;

- − Small improvements involving the repair and construction of sidewalks, bicycle paths, arranging public spaces, creating small green areas, introducing elements of small architecture.

Private investments are increasingly accompanying the activities of public authorities. They are often associated with the renovation of private tenements and the construction of new residential and commercial buildings in so-called “plombas”, i.e., undeveloped spaces between buildings, as well as the development of post-industrial and post-military sites (e.g., the Old Brewery Cultural and Commercial Center, City Park housing estate). Support in this regard was offered by the JESSICA initiative, which includes low-interest loans for regeneration activities. However, an unintended effect of the regeneration process was the relocation of poorer residents to other parts of the city not covered by regeneration. Gentrification has become an indispensable part of urban revitalization [51]. The value of regeneration projects in Poznań between 2014 and 2023 alone is estimated at 34 million euros by the Ministry of Development Funds and Regional Policy of Poland. As a result, only five meetings have been held in 4 years (which, however, was also affected by the COVID-19 pandemic). However, no constructive criticism of the regeneration process has been formulated by members of the Regeneration Committee.

4.2.1. Social and Economic Aspects

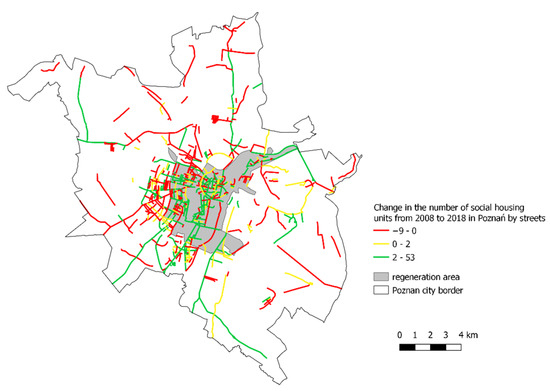

The ongoing regeneration was met with mixed opinions from those surveyed. All interviewees believed that the regeneration has had significant repercussions on the social structure of the regenerated area, undermining opportunities for local development partnerships. They claimed that people living in private owners’ buildings were the most affected by the process. The uncontrolled increase in leases in renovated private buildings has effectively deprived less affluent people of the possibility of staying in their flats, forcing many of the original inhabitants to displacement. The former, permanent residents of the regenerated area were replaced by new, better-off ones. The lack of regulations to protect the original inhabitants was considered to be the reason for this situation. Such rules were not included in the Urban Regeneration Act of 2015. Several interviewees, including an employee of the Municipal Family Support Center, highlighted that as a result, only people living in social housing with low and regulated rent were in a better situation. As a result, the regeneration area is seeing an increase in this type of housing, which, however, to some extent compensates for the need to relocate from private owner-occupied housing (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Change in the number of social housing units from 2008 to 2018 in Poznan by streets. Source: own elaboration based on data from Poznań City Hall.

The interlocutors not only paid attention to replacing the social fabric but also to changing the dominant character of the revitalized districts from permanently inhabited to “areas for rent”, resulting in the disappearance of the community. In renovated buildings, they noticed a tendency to transform flats into offices. This modus operandi allowed the owners to obtain higher rental income. In turn, buying apartments in newly erected buildings was often treated as an investment. One of the speakers—the developer—did not hide his surprise that most of the first apartments he had built in the regeneration area went for rent. Today the same entrepreneur, still operating there, optimizes profits by offering mainly micro-apartments, i.e., 21 to 33 square meters. In practice, these flats are for both short-term and long-term rental. Another interviewee, the city councilor, emphasized that the real estate market, where these small investment dwellings prevail, is not conducive to settling families with children in the regeneration area. In addition, he said, buying apartments in the city center is often too expensive for those who wish to live there, whereas families who could afford it prefer living in peripheries and suburbs. The city, in turn, for any sake, cannot afford to buy from developers of such expensive real estate for council housing.

As mentioned earlier, housing values and rents have increased in the revitalized area. That was highlighted by all participating in the in-depth interviews. Most of them considered developers and wealthy people the biggest beneficiaries of the regeneration process. In addition, economic changes related to regeneration were also reflected in the range of services available. During interviews, respondents noted that the nature of services offered has definitely changed. The number of cafes, restaurants, hotels and hostels has increased. Other available service establishments are used by law firms, beauty salons and private medical facilities. These new services are better suited to the needs of new residents and tourists than those who originally lived in the area. They have found that the new services are not only beyond the financial reach of the original residents, but also lie outside the spectrum of their needs, and are sometimes downright inconvenient for them. In turn, essential services such as affordable local grocery stores and food stalls, i.e., low-profit businesses, have become less numerous. They have been largely superseded by more expensive outlets, i.e., national chains of small convenience stores or, e.g., artisan bakeries and organic food stores. Our interviewees noted that market activities targeting the middle class and tourists prevail in the regenerated areas; therefore, they are not low-income-friendly spaces.

4.2.2. Environmental Aspects

Although they were not the most discussed aspects, respondents noted that several activities were carried out as part of the renewal, which targeted improving the quality of the city’s natural environment. As in the area of regeneration the air cleanliness standards are exceeded, and the most important source of pollutants supplied to the air is anthropogenic emission, inter alia, out of a large number of households based on individual heating systems powered by solid fuels, the city decided to introduce the KAWKA program encouraging the replacement of heat sources with ecological ones. However, as the employee of the Municipal Family Support Center emphasized, despite financial incentives, many households did not take advantage of this opportunity, fearing a dramatic increase in heating costs. He stated that the most economical solution for less-affluent families is still a stove, in which, if necessary, almost everything can be burned. On the other hand, an ecological activist and author of environmental impact forecasts for the city of Poznań positively assessed the city’s activities aimed at protecting the Warta River embankment. In a similar vein, he spoke about the city’s initiative, which is indispensable in the face of adaptation to climate change, to promote small retention by creating rain gardens and changing the surface of, e.g., playgrounds. Nevertheless, he also noted that the city’s attempts to introduce greenery in large investments carried out in the area of revitalization are insufficient “there are too few trees, they are too young for now, which intensifies the impression that their number is little, they are often planted in pots, which means that they will never grow as fine trees. The problem of soil sealing is present in Poznań, as in many other cities in Poland.” Other interviewees were also of the opinion that although the city revitalizes small green areas, the scale of these activities is deficient. Additionally, some of these green initiatives, such as community gardens co-initiated by the city in revitalized districts, do not survive in the long term.

4.2.3. Spatial and Technical Aspects

The interviewees generally positively commented on the spatial changes in the area of regeneration. They highlighted the order and new attractive image of previously neglected spots, the creation of the parks and greenery, the modernization of public spaces, the arrival of new street furniture, and the development of places to promote cultural life. However, the site inventories showed that still in prime locations, in the very center of the city, there are unsightly car parks. Such areas, often adjacent to emblematic monuments, prove that the regenerated space has not caught up with Western European standards. In addition, while evaluating the spatial aspect of regeneration, some speakers noticed other spatial development problems. They complained about the insufficient connection of the implemented investments with the real needs of the inhabitants. One person, an architect, gave examples of several projects implemented without cooperation with local communities and as a result, in his opinion, are still not integrated into the regenerated areas, i.e., a green square, an exhibition pavilion, a cultural center. At the same time, however, the same interviewee spoke positively of the bicycle routes and paths running along the Warta river in the city center.

When asked about the technical side of the regeneration process, interviewees highlighted that many buildings had undergone restoration. The result is that shabby façades are much less frequent, although still present. They noticed that flats in renovated tenement houses have now a completely different standard. However, there were also critical comments questioning the quality of the work performed. Some interviewees, doubting its long-term effect, suggested that they were done superficially without due diligence. Criticism also concerned the insufficient quality of street furniture and excessive concreting of regenerated spaces (“concertos”—betonoza), which site inventories confirmed. The speakers, complaining about the lack of proper protection of architecture and landscape, also argued that new residential buildings are often out of tune with their mismatched surroundings and questionable architectural quality. They disturb and completely change the regenerated area’s image.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The systemic transformation in Europe was a shock that can be described as an economic stressor that led to the decline of cities, especially their central, historic parts. The response to this phenomenon was regeneration strategies, which, thanks to support from European Union funds, have become an extremely popular tool to support urban development. CEE countries, especially in the area of regeneration, have tried to work out national policies between the pressures of European Union regulations on the one hand and the temptations of a self-regulating liberal economy on the other [52]. It was an extremely difficult path with good and bad sides for urban residents. Over the years, the approach to regeneration has evolved towards an increasing emphasis on social aspects while underestimating environmental issues. It was, in a way, an understandable direction, as the effect of systemic transformation in CEE was often unemployment and increased poverty [53]. However, our study findings show that regeneration projects had precisely the opposite effects: very low social efficiency, gentrification and exclusion. This was due not only to insufficient public participation but also to the fact that the indicators used in the renewal process serve to characterize society rather than an in-depth analysis aimed at solving its problems, e.g., the migration of residents was not monitored, nor was the ownership structure of flats in revitalized districts. Defining areas of regeneration based on the social problems identified did not translate into solving them, but it did help to intensify investment processes there. Our study revealed that regeneration in Poznan led to rapidly rising private housing rental prices and the relocation of residents. Social housing development activities have done little to offset this problem. This is consistent with studies conducted in other cities that show that regeneration leads to the subsequent loss of social diversity in the affected area due to rent increases and changes in housing tenure [54,55]. The process of gentrification is therefore inherent in the regeneration of Poznan (and many other Polish cities) [51]. Private investors are much more important in regeneration leading to gentrification than in many other CEE countries [56]. Services are also changing. These new ones are better suited to the needs of new residents and tourists rather than those who originally lived in the regeneration areas. In light of the results of the study, environmental issues, undervalued by regeneration programs, have a large impact on the public perception and assessment of the process. It might seem to be the case that environmental issues resonate more with the public than the socially disadvantageous consequences of the regeneration process. People are very concerned about the environmental misses of the projects, such as the lack of urban greenery, and soil sealing. In Poland, the phenomenon of concreting spaces (“concertos”) is commonly equated with regeneration. This is because many investments have abandoned the introduction of greenery, which would generate additional maintenance costs, or could be harmful to underground technical infrastructure networks. Regeneration strategies, which are supposed to be a response to the transformation shock, largely lead to further shocks, related to the relocation of residents, increased air pollution, or increased air temperatures in the center (as a result of concreting the space). The situation could be different if a greater role were given to the local community and if a problem-solving approach were adopted. As [57] note, the engagement of multi-layered stakeholders can only take place with considerable difficulty under the top-down policies that still prevail in Poland.

Author Contributions

All parts of the article and stages of the work were worked out jointly by all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval was waived for this study due to the fact that it is not in the guidelines of the National Science Center of Poland, a major research grantor, regarding research for which an Ethics Committee opinion is required https://ncn.gov.pl/sites/default/files/pliki/2016_zalecenia_Rady_NCN_dot_etyki_badan.pdf, accessed on 2 September 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Statistics Poland (GUS). https://stat.gov.pl/ accessed on 20 August 2022.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the interviewees who expressed their willingness to cooperate in implementing this study. We also thank the reviewers for their valuable insights.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Vilenica, A.; Florea, I.; Popovici, V.; Pósfai, Z. Urban struggles and theorising from Eastern European cities. In Global Urbanism; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 306–316. [Google Scholar]

- Ciesiółka, P.; Burov, A. Paths of the urban regeneration process in Central and Eastern Europe after EU enlargement—Poland and Bulgaria as comparative case studies. Spatium 2021, 46, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusiak, J. Revitalizing urban revitalization in Poland: Towards a new agenda for research and practice. Urban Dev. Issues 2019, 63, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gołata, E.; Kuropka, I. Large cities in Poland in face of demographic changes. In Bulletin of Geography; Szymańska, D., Biegańska, J., Eds.; Socio-Economic Series, No. 34; Nicolaus Copernicus University: Toruń, Poland, 2016; pp. 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cysek-Pawlak, M.; Krzysztofik, S.; Makowski, A. Urban regeneration and urban resilience planning through connectivity: The importance of this principle of new urbanism. Eur. Spat. Res. Policy 2022, 29, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzarovski, S.; Salukvadze, J.; Gentile, M. A Socially Resilient Urban Transition? The Contested Landscapes of Apartment Building Extensions in Two Post-communist Cities. Urban Stud. 2011, 48, 2689–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1973, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C. Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Glob. Environ. Change. 2006, 16, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P.; Stults, M. Defining urban resilience: A review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 147, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, S. Growing Biodiverse Urban Futures: Renaturalization and Rewilding as Strategies to Strengthen Urban Resilience. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckle, P. New Approaches to Assessing Vulnerability and Resilience. Aust. J. Emerg. Manag. 2000, 15, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Pelling, M. The Vulnerability of Cities: Natural Disasters and Social Resilience; Earthscan Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Alberti, M.; Marzluff, J.M. Ecological resilience in urban ecosystems: Linking urban patterns to human and ecological functions. Urban Ecosyst. 2004, 7, 241–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coaffee, J.; Wood, D.M.; Rogers, P. The Everyday Resilience of the City: How Cities Respond to Terrorism and Disaster; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Adger, W.N. Social and ecological resilience: Are they related? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2000, 24, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keck, M.; Sakdapolrak, P. What is social resilience? Lessons learned and ways forward. Erdkunde 2013, 67, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashman, A. Case study of institutional and social responses to flooding: Reforming for resilience? J. Flood Risk Manag. 2011, 4, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, D. Participatory modelling of vulnerability and adaptive capacity in flood risk management. Nat. Hazards 2011, 67, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, M.; Willis, E.; Wadham, B.; Binks, B. Attitudes to Drought in Outback Communities in South Australia. Geogr. Res. 2010, 48, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langridge, R.; Christian-Smith, J.; Lohse, K.A. Access and Resilience: Analyzing the Construction of Social Resilience to the Threat of Water Scarcity. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, N.; Marshall, P.; Abdulla, A. Using social resilience and resource dependency to increase the effectiveness of marine conservation initiatives in Salum, Egypt. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2009, 52, 901–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G.R. Transformation from “Carbon Valley” to a “Post-Carbon Society” in a climate change hot spot: The coalfields of the Hunter Valley, New South Wales, Australia. Ecol. Soc. 2008, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keck, M.; Bohle, H.-G.; Zingel, W.-P. Dealing with insecurity. Informal business relations and risk governance among food wholesalers in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Z. Wirtsch. 2012, 56, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavovic, B.C.; Scheyvens, R.A.; Overton, J.D. Waves of adversity, layers of resilience: Exploring the sustainable livelihoods approach. In Contesting Development: Pathways to Better Practice, Proceedings of 3rd Biennial Conference of the Aotearoa New Zealand International Development Network (DevNet), Palmerston North, New Zealand, 5–7 December 2002; Storey, D., Overton, J., Eds, B.N., Eds.; Institute of Development Studies: Palmerston North, New Zealand, 2003; pp. 289–293. [Google Scholar]

- Bohle, H.-G.; Etzold, B.; Keck, M. Resilience as agency. IHDP-Update 2009, 2, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Jabareen, Y. Planning the resilient city: Concepts and strategies for coping with climate change and environmental risk. Cities 2013, 31, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirfenderesk, H.; Corkill, D. Sustainable management of risks associated with climate change. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 2009, 1, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desouza, K.; Flanery, T.H. Designing, planning, and managing resilient cities: A conceptual framework. Cities 2013, 35, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, W.J. When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor; Knopf: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sassen, S. Cities in a world economy. In The Boston Globe (2013): A Reconstruction of Terror; Pine Forge Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Scheffran, J.; Marmer, E.; Sow, P. Migration as a contribution to resilience and innovation in climate adaptation: Social networks and co-development in Northwest Africa. Appl. Geogr. 2012, 33, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stohr, W. Regional Policy at the Crossroads: On Overview. In Regional Policy at the Crossroads: European Perspective; Albrechts, L., Moulaert, F., Roberts, P., Swyngedlouw, E., Eds.; Jessica Kingsley: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Lichfield, D. Urban Regeneration for the 1990’s; London Planning Advisory Committee: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Pugalis, L.; Liddle, J. Editorial: Austerity era regeneration. Conceptual issues and practical challenges. Part 1. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 2013, 6, 333–338. [Google Scholar]

- Albrechts, L. Strategic (spatial) planning re-examined, Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design. SAGE J. 2004, 31, 743–758. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J.W.; Kühn, M. Urban Change and Urban Development Strategies in Central East Europe: A Selective Assessment of Events Since 1989. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2012, 20, 1093–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, P.; Sykes, H. Urban Regeneration; Sage: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Temelová, J. Urban revitalization in central and inner parts of (post-socialist) cities: Conditions and consequences. In Regenerating Urban Core; Ilmavirta, T., Ed.; Center for Urban and Regional Studies: Helsinki, Finland, 2009; pp. 12–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, T. Urban Geography, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, A. Strategy and Partnership in Urban Regeneration. In Urban Regeneration; A Handbook; Roberts, P., Sykes, H., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, M. Gentrification and Social Stratification in Tallinn: Strategies for Local Governance; SOCO Project Paper No. 86; Institut für die Wissenschaften vom Menschen: Vienna, Austria, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Földi, Z. Neighbourhood Dynamics in Inner-Budapest: A Realist Approach; Netherlands Geographical Studies No. 350; University of Utrecht: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek, S.; Marcińczak, S. The blessing in disguise. Urban regeneration in Poland in a neo-liberal milieu. In The Routledge Companion to Urban Regeneration; Leary, M.E., McCarthy, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ciesiółka, P.; Gunko, M.; Pivovar, G.A. Who defines urban regeneration? Comparative analysis of medium-sized cities in Poland and Russia. Geogr. Pol. 2020, 93, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsson, E.; Elander, I. Sustainability Potential of a Redevelopment Initiative in Swedish Public Housing: The Ambiguous Role of Residents’ Participation and Place Identity. Prog. Plan. 2015, 103, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesiółka, P. Urban Regeneration as a New Trend in the Development Policy in Poland. Quaestiones Geographicae 2018, 37, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarczewski, W.; Kułaczkowska, A. Raport o Stanie Polskich Miast Rewitalizacja; Instytut Rozwoju Miast i Regionów: Warszawa, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Arnstein, S. A Ladder of Community Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesiółka, P.; Maćkiewicz, B. From regeneration to gentrification: Insights from a Polish city. People Place Policy Online 2020, 14, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallagst, K.; Mercier, G. Urban and regional development in central and eastern European countries—From EU requirements to innovative practices? In Eastern European Cities in the Post-Socialist Period; Stanilov, K., Ed.; Springer-Verlag: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Enyedi, G. Transformation in Central European postsocialist cities. Discuss. Pap. Cent. Reg. Stud. Hung. Acad. Sci. 1998, 21, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N. Gentrification and the rentgap. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1987, 77, 462–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, R. Social and community issues. In Urban Regeneration; Roberts, P., Sykes, H., Granger, R., Eds.; SAGE: London, UK, 2016; pp. 99–112. [Google Scholar]

- Sykora, L. Gentrification in Post-communist Cities. In Gentrification in a Global Context; Atkinson, R., Bridge, G., Eds.; The New Urban Colonialism; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2005; pp. 90–105. [Google Scholar]

- Kourtit, K.; Nijkamp, P.; Vaz, T.D.N. Cities in a shrinking globe. Int. J. Glob. Environ. Issues 2015, 14, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).