Abstract

Radio waves are attenuated by atmospheric phenomena such as snow, rain, dust, clouds, and ice, which absorb radio signals. Signal attenuation becomes more severe at extremely high frequencies, usually above 10 GHz. In typical equatorial and tropical locations, rain attenuation is more prevalent. Some established research works have attempted to provide state-of-the-art reviews on modeling and analysis of rain attenuation in the context of extremely high frequencies. However, the existing review works conducted over three decades (1990 to 2022), have not adequately provided comprehensive taxonomies for each method of rain attenuation modeling to expose the trends and possible future research directions. Also, taxonomies of the methods of model validation and regional developmental efforts on rain attenuation modeling have not been explicitly highlighted in the literature. To address these gaps, this paper conducted an extensive literature survey on rain attenuation modeling, methods of analyses, and model validation techniques, leveraging the ITU-R regional categorizations. Specifically, taxonomies in different rain attenuation modeling and analysis areas are extensively discussed. Key findings from the detailed survey have shown that many open research questions, challenges, and applications could open up new research frontiers, leading to novel findings in rain attenuation. Finally, this study is expected to be reference material for the design and analysis of rain attenuation.

1. Introduction

The increasing demand for high data rate and capacity, and the inability of previous generations to meet these demands, have motivated the research and development of the 5G communication network [1,2]. The 5G wireless network has promised to provide a multi-Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) data rate with extremely low latency and better quality of service (QoS) that would support critical services. These services comprise, but are not limited to, the provision of e-health, especially in rural areas [3,4,5], equitable and inclusive education [6,7,8], smart farming [9,10], and bridging of the digital divide [11,12,13].

Millimeter wave (mmWave) communication within the frequency range 30–300 GHz has been proven to be the candidate band for 5G communication networks and beyond due to the scarcity of spectrum frequency below 5 GHz (sub-6 GHz) [14,15,16,17,18]. The mmWave band offers the security of communication transmissions and supports the large bandwidth required to provide higher data rates for fronthaul, backhaul and short building-to-building links [2,19,20,21,22]. However, the major drawback of the millimeter wave signal is its inability to travel over a long distance due to its susceptibility to attenuation by various atmospheric phenomena such as rain, foliage, and other atmospheric absorption [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30].

Rain, among all other atmospheric phenomena, is the major source of microwave and millimeter wave signal attenuation through absorption and scattering in terrestrial and satellite communication links. When the operating frequency exceeds 10 GHz, the attenuation effect becomes very severe, particularly in the tropics, with tendencies of heavy and thunderous rain droplets and depths [31,32,33,34]. Rainfall is a complex meteorological phenomenon due to its inhomogeneous behavior in terms of duration, frequency of occurrence, and location. The inhomogeneous nature makes it highly unpredictable and challenging when estimating its effect on link design. However, if the rainfall rate variation throughout the entire signal path is known, the rain attenuation can be estimated from the integration of the specific attenuation and path length [35,36]. Conventionally, rain rates are measured using rain gauges, disdrometers, and weather radars. The data obtained from such measuring instruments are usually used to develop models that help in predicting and, in some cases, mitigating the effect of rain attenuation on the links.

Several researchers over the years have developed novel models and methods, in some instances modifying existing ones for estimating rain rates across various frequencies and climatic locations [37,38,39,40,41,42,43]; notably, the ITU-R has also developed a couple of models [44,45]. It is worthy to note that some of the climatic variables such as wind speed, rainfall intensity, frequency, polarization, path length, temperature, humidity, etc., have impending effects on rain attenuation. These thus expose the limit of validity of most of the aforementioned models as these models attempt to evaluate the relationship between rain rate and path length to obtain rain attenuation [46].

This paper aims to conduct a systematic review of rain attenuation models. The different prediction and mitigation models are broached, including the taxonomies in different areas of rain attenuation modeling and analysis, noting research gaps and recommending further directions of research. The noteworthy contributions of this review paper are outlined as follows:

- ▪

- An extensive, systematic review of rain attenuation models for the past 30 years (1990–2022) is provided.

- ▪

- A panoramic view of rain attenuation models and an exhaustive review of studies that have utilized these models is presented, including a taxonomy that followed the work of [47].

- ▪

- A comprehensive analysis of the total and specific attenuation based on various atmospheric conditions and other impairments, including the radome, is discussed.

- ▪

- An exhaustive review of rain attenuation prediction using machine learning models is presented, including a proposed taxonomy of these models.

- ▪

- An in-depth analysis and review of fade mitigation techniques is presented.

- ▪

- Critical open research issues and future research directions are identified for rain attenuation and elaborated.

The structure of the paper is as follows: The “Review of Previous Rain Attenuation Models” Section 2 reviews prior review works on rain attenuation models. The “Background on Rain Attenuation” Section 3 summarizes the theory of rain attenuation, rain attenuation factors, and the various ways to obtain rain rate data, as well as the survey of rain attenuation across regions. The “Rain Attenuation Models” Section 4 discusses and reviews the various existing rain attenuation models. Furthermore, signal attenuation due to various atmospheric impairments and total propagation attenuation is examined in the “Total Attenuation” Section 5. Similarly, the specific attenuation scenarios are presented in the “Specific Attenuation” Section 6. The “Review of Different Methods of Model Validation” Section 7 summarizes the various model validation techniques, including the properties of the existing rain attenuation models. The various machine learning-based models are presented and reviewed in the “Machine Learning-Based Rain Attenuation Prediction Models” Section 8. The various fade mitigation techniques, including the weaknesses of the ITU-R model for short distances, are discussed and reviewed in the “Fade Mitigation Techniques For 5G” Section 9. The “Further Research Direction” Section 10 provides a clear path for further research in rain attenuation. Finally, a concise conclusion is drawn in the “Conclusion” Section 11.

2. Review of Previous Rain Attenuation Models

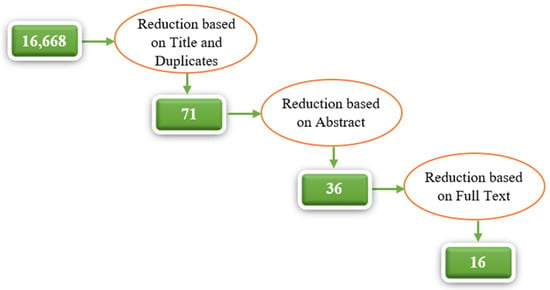

This section presents a systematic review of previous works on rain attenuation, covering the last three decades, 1990 to 2022, with a binocular focus on review articles only. The academic databases employed for this review include IEEE Explore, MDPI, ACM Digital Library, Springer, Science Direct, and Google Scholar. These databases are comprised of reliable and good quality peer-reviewed publications such as review articles, research articles, and conference papers. The search term “rain attenuation review” was used to query these databases to obtain relevant literature review articles published between 1990 and 2022, from which 16,668 review publications were obtained across all the selected databases, all written in the English language which had been chosen as one of the inclusion criteria. To avoid duplicates, papers found on a generic database such as Google Scholar were traced back to their respective publishing journal and counted under that journal, rather than being counted under Google Scholar. Figure 1 shows the article selection process used to screen the pool of articles to further reduce the search results. Table 1 summarizes the number of articles obtained from the different databases consulted, including the percentage in descending order in terms of relevance to the subject of interest. Table 2 presents an overview of previous rain attenuation model reviews which includes their objectives and findings. Table 3 provides a summary of the comparison between the current survey and the existing ones.

Figure 1.

Articles Selection Process.

Table 1.

Search Databases and Number of Articles.

Table 2.

Summary of Previous Rain Attenuation Review Publications.

Table 3.

Summary of Comparison between the Current and Existing Surveys.

From Table 3, it can be seen that most review works focused more on empirical and statistical models without considering mitigation models as well as machine learning-based models for rain attenuation. Also, most of the review work that included the rain attenuation prediction models did not consider the rain fade mitigation techniques and vice versa. From the overall systematic review, it can be seen that there is very little review work done on rain attenuation that shows the trend of work done in the research area and proffers further direction. Hence, this paper aims to extensively review and analyze the different existing prediction and mitigation models for rain attenuation, including machine learning-based models, as well as provide further directions to bridge these existing gaps

3. Background on Rain Attenuation

This section provides a preliminary discussion on rain attenuation, which includes the theory behind rain attenuation, rain attenuation factors, rain data gathering methods, and spatial interpolation methods for estimating rain rate.

3.1. Theory of Rain Attenuation

In general, electromagnetic waves transport photons, which carry energy where h is Planck’s constant and is the frequency of the emitted electromagnetic wave. Absorption and dispersion occur as the wave travels through matter. Absorption is the capacity of an atom and molecule to retain the energy conveyed by the photons. In the case of dispersion, the retained energy of the photons is re-emitted out, taking various paths with varying concentrations. The spatially dispersed waves are responsible for scattering [56]. These activities caused electromagnetic signals to be attenuated by rain. In this regard, the energy of the molecules can be expressed as Equation (1):

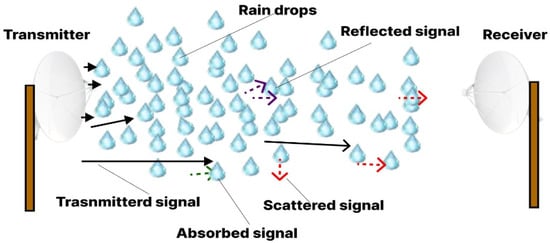

where is the energy of the molecule, is the electron energy of the molecule, is the vibrational energy of the atom around the equilibrium position of the molecule, is the rotational energy corresponding to the rotation of the molecule about its symmetry axis, and is the translational motion energy of the molecule. The difference in energy between a molecule’s initial and excited states is said to be equal to the absorbed energy of the photon when the molecule changes its quantum level. Figure 2 illustrates that raindrops can cause electromagnetic signals to be absorbed, scattered, diffracted, and depolarized.

Figure 2.

Impact of Rain on Electromagnetic Wave Propagation [62].

As the frequency increases, the wavelength becomes smaller. When the wavelength of the rain is a few mm less than the frequency, the attenuation increases. The Average Raindrop Size (ARS) has a diameter of 1.67 mm while 10–100 GHz signals have wavelengths of 30–3 mm. A raindrop has an average diameter of 0.1–5 mm. In the case of Rayleigh scattering by raindrops, known as the scattering function as given in Equation (2), the droplet size is substantially less than the wavelength, which is satisfied for frequencies up to 3 GHz. The function specifically applies to the raindrop scattering properties and is affected by the radius of the raindrop, the shape of the raindrop, the complex permittivity, and the frequency of the transmitted signal.

where is the complex permittivity of the droplet, is the raindrop size, and is the wavelength. Mie’s approximation for the scattering function is given as Equation (3):

where is the imaginary unit and is the Mie’s coefficients which are constituted of Bessel functions of order . The vertical and horizontal polarization for the specific rain attenuation can be expressed as Equation (4):

where is the propagation constant, is the raindrop size, and is the raindrop size distribution which can be calculated using Equation (5) as:

where denotes the rain rate in mm/h.

3.2. Rain Attenuation Factors

3.2.1. Path Length

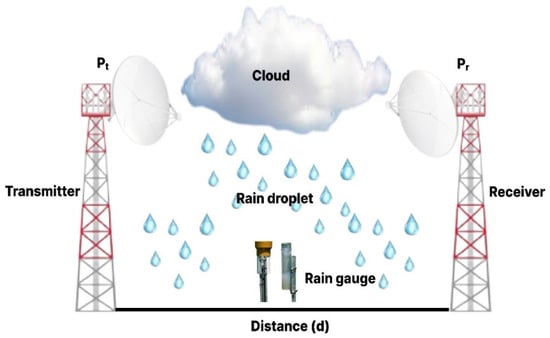

The path length is critical in determining Rain Attenuation which can be estimated by multiplying the effective propagation path length () and specific rain attenuation ) as shown in Equation (6) [2]. Figure 3 depicts a conventional experimental setup to measure rain attenuation, which consists of transmitter and receiver stations separated by a distance or path length

Figure 3.

A Conventional Experimental Setup to Estimate Rain Attenuation [56].

Specific attenuation is calculated using a 1-min cumulative distribution rain rate expressed in decibels per kilometer (dB/km). The path length, typically determined at one end, can be estimated by multiplying the path adjustment factor by the real distance. However, it can be determined from Equation (6) with respect to the point rain rate [62]. According to [47], many models compute the effective propagation path length by employing a compensatory factor known as the path reduction factor or path adjustment factor.

3.2.2. Frequency and Polarization

The specific attenuation, (dB/km), expressed in terms of the rain rate, frequency, and polarization, can be easily estimated using the power-law relationship as shown in Equation (7):

where denotes rainfall rate exceeded at p% of the time, and are the functions of frequency that depends on the polarization, which can be empirical values and can be obtained experimentally [21,63]. The ITU-R P.838-3 [44] includes a look-up table for values of and for frequencies ranging from 1 to 100 GHz in vertical and horizontal polarization.

3.3. Different Sources and Procedures of Rain Rate Data Collection

Due to the dependence of rain attenuation on rain data, available procedures for rain data collection are defined in this section. These methods range from available databases, experimental, synthetic, and data-logged methods, to prediction techniques based on interpolation methods.

3.3.1. Rain Data from Databases

The ITU-R Study Group 3 databanks (DBSG3) [64] rain database is one of the most extensively utilized databases as it contains an extensive set of measurement data of attenuation due to various weather conditions. Furthermore, several weather databases from European institutions, such as the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts, are available and are alternative sources of rain rate data. Unfortunately, the centers do not give information or have rain attenuation equipment for tropical locations. It has therefore been established that those tropical countries need models that could assist in developing their databases for rain data which could be used to prepare the corresponding rain attenuation databases. Other databanks hold weather data that are local to their location; for example, in Nigeria there is the Nigerian Meteorological Agency (NiMet) that can provide recent weather data that can be used by researchers to easily develop and evaluate models as well as estimate the effect of these weather conditions on communication.

3.3.2. Synthetic and Data-Logged Method of Rain Rate Estimation

A mathematical method that can be used to generate rain attenuation time series accurately, known as the Synthetic Storm Technique (SST), converts a rain rate time series at a specific location into a rain attenuation time series [65]. This technique is used in place of the logged data technique to save time and cost.

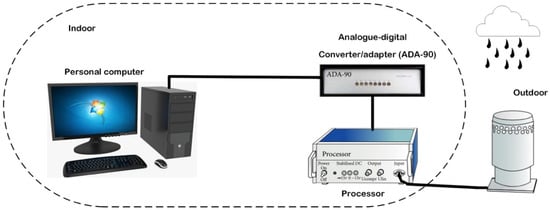

3.3.3. Experimental Setup

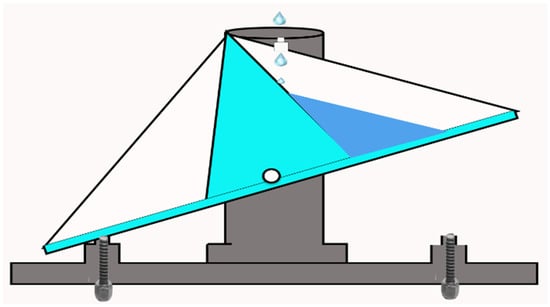

The best way to obtain the rain rate is by measurement through weather instruments and facilities, for instance, a disdrometer or a rain gauge, at a reduced integrating time. A disdrometer is a device that detects raindrop size distributions (DSD). In some instances, the terminal velocity of falling hydrometeors can also be used to distinguish between various kinds of precipitation such as raindrops, snowflakes, graupel, or hail over time [66,67]. Figure 4 depicts a typical setup for rain rate measurement using a disdrometer.

Figure 4.

Measurement System for a Disdrometer [68].

Many studies have employed various kinds of disdrometers, such as the JW RD80 disdrometer [69], or optical disdrometers which use image or laser technology [70,71], to obtain rainfall data used in predicting the rain attenuation within a particular region. However, they are subject to wind and evaporation errors.

The amount of rainfall within a particular location over a period of time can be measured accurately using a meteorological instrument known as a rain gauge. Rain gauges are frequently utilized because of their ease of use and dependability, thus lowering installation and maintenance costs. They also provide reliable in-place observations [66]. However, due to their sparse distribution, rain gauges are inadequate for estimating area rainfall, especially in areas with many spatial variabilities, like mountain ranges. The tipping bucket rain gauge is a popular rain gauge in which each tip correlates to a specific amount of rainfall [72]. Figure 5 shows a tipping bucket rain gauge.

Figure 5.

Tipping Bucket Rain Gauge [73].

Atmospheric parameters—air pressure, humidity, temperature, wind direction, and speed, as well as precipitation—can be measured using instruments and equipment housed in a facility known as a weather station. Information obtained can be employed to study and forecast weather and climate. A weather radar is a remote sensing device used by hydrological and meteorological communities to estimate area precipitation with high spatial and temporal precision [74]. To measure the rain rate in some instances, the rain cell’s radar information can be used by sending out an electromagnetic signal that interacts with the raindrops at the atmospheric level, which would reflect the intercepted power towards the radar—backscattering. According to [75], using radar to compute the rain rate primarily involves three steps: (1) Calibrating the radar, which influences the accuracy of the rain rates as a miscalibration can lead to bias in the rain rate results. (2) Quality control, which is the scrutinization of the radar data to reduce the effects of non-meteorological scatters both on the ground and in the atmosphere such as aircraft, etc. (3) Rain rate estimation using the calibrated reflectivity values, which describes the size, shape, state, and concentration of the hydrometeor as well as the azimuth, distance, polarization, intensity, phase, etc., which can be used to then compute the rain rate. Most research did not utilize a weather radar, but rather used either a disdrometer or a rain gauge and, in most cases, used the combination of both to get rainfall data.

3.3.4. Spatial Interpolation Method for Rain Rate Prediction

The use of spatial distribution methods for rain rate prediction is critical due to the impossibility of measuring rain rates everywhere in a given location. When experimental methods cannot accurately calculate rain rates, the spatial distribution method is employed to ensure accuracy. Some mathematical models have been developed to improve the accuracy of this method. One such model is called the Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW) method, and the expression for the determination of the rain rate at a location up to 30 km is as shown in Equation (8):

where is the rain rate, is the number of rain gauges, is the weighted sum of the rain gauges’ readings, and is the weight of each rain gauge reading. The MultiEXCELL method can be used in a situation where local rain data are available. Several kinds of literature have used this method to obtain rain rates. The calculation and estimation of rain attenuation based on the three factors have been discussed in this section. The four different data collection methods were also presented and discussed, as well as the spatial interpolation methods of rain rate prediction used to ensure accuracy, based on mathematical models, in locations where an experimental setup cannot accurately measure the rain rate.

3.4. Survey across Regions

Rain as a natural event is defined using different rate intensity thresholds. The most generally used term in the literature is based on the interval when the rain rate exceeds 0.2 mm/h. Based on an approach that seeks to exploit the inhomogeneous nature of tropical rain distribution, called Site Diversity, a rainfall event can either be convective (CV), stratiform (ST), or storm-wind [76].

A CV rain event is an intense rainstorm within a small geographical area for a short duration. ST, on the other hand, is a mild shower that lasts longer and is more widespread. Storm-wind rain is a rainstorm characterized by intense clouds and severe aftereffects in some local locations for brief periods [77,78]. Hence, since all the rain types are defined within the distance domain called rain cells, any two links located at different places (or cells) will experience different levels of attenuation while receiving signals from the same source [79]. CV and ST are more prevalent in the tropics and in temperate regions, respectively [80].

Rainfall is a crucial climatic component in a tropical environment like Nigeria where it can severely influence both earth-space and satellite communication links operating at frequencies exceeding 10 GHz, thus making it a critical design factor for wireless communication systems. This impairment is termed rain attenuation and is found to vary directly with both the raindrop size and the rain rate [81]. The two existing approaches for estimating rain attenuation both use measured rainfall rate statistics, namely, (1) empirical methods where attenuation due to rain is estimated using real measured rain data from databases across various tropical areas, and (2) physical methods which deal with the physical characteristics involved in the estimation of attenuation process [54,82]. However, the resource implications for an empirical approach to be adopted, particularly in the tropics, have rendered it less realistic, significantly impacting the availability of the much-needed rain measurement data to build appropriate physical models for the design of abundant wireless channels [83].

Over the years, the ITU-R sector has been able to develop, through research efforts, a unified global model that can be used to estimate the attenuation due to rain for both LOS and NLOS environments corresponding to the major global divide that has divided the world into temperate and tropical regions. The new ITU-R 530-16 results from ongoing work and developments to solve performance problems associated with prior models. However, measured rain data from the equatorial and tropical areas have not been employed to validate this model [84]. Table 4 shows the summary of different work carried out across regions based on the ITU, including the model proposed, findings, and site locations.

Table 4.

Summary of Rain Attenuation across Regions.

4. Rain Attenuation Models

In this section, the different existing rain attenuation models classified under five categories are presented and discussed as well as a brief review of previous research on rain attenuation in 5G using these models.

4.1. Empirical Models

This section discusses some of the empirical models and reviews relevant work on rain attenuation for 5G using these models. An empirical model is based on experimental data observations that can be described mathematically. Eight empirical models are used for the rain attenuation model, and a review of the rain attenuation modeling using these models is presented in Table 5.

4.1.1. Garcia Model

This model [106] is one of the modified versions of the Lin model that is best suited for temperate European locations and can be represented mathematically expressed as shown in Equation (9):

where denotes rain attenuation (dB), denotes rain rate (mm/h) averaged on a given time interval of 1 min, is the path length in km, and and are functions of frequency.

4.1.2. Crane Model

This model [37] predicts high attenuation in low rainfall locations and offers global rain distribution. It can be expressed mathematically as shown in Equation (10):

where denotes rain attenuation (dB), denotes rain rate (mm/h) exceeded at %p of the time, and and are functions of frequency. Other remaining coefficients are empirical constants of the model, expressed in Equations (11)–(14):

4.1.3. Mello Model

This model [40] was developed by utilizing a complete rainfall rate distribution as input to predict the rain attenuation cumulative distribution due to the inaccurate prediction of the ITU-R model, where two regions having different rainfall rate conditions would have similar values of rain attenuation , and can be expressed mathematically as shown in Equation (15):

where denotes rain attenuation exceeded at p% of the time, denotes rainfall rate in mm/h, is the path length, while and are functions of frequency.

4.1.4. Moupfouma Model

In this model [39], is the distance between ground stations, that is, the actual propagation path length; its equivalent propagation path length can be determined using an adjustment factor that ensures the uniformity of the rain on the entire propagation path and can be represented mathematically as shown in Equation (16):

where is the rain attenuation expressed in dB exceeded at p% of the time. The specific attenuation in terms of the rain rate expressed in dB/km is , is the rain rate exceeded p% of the time, and is the equivalent path length for which the rain propagation is assumed to be uniform.

4.1.5. Peric Model

According to [47], this dynamic model has no real network–environment test and application. Rather, it is based on the cumulative distribution function for a particular area of interest, the number of rain occurrences that exceed the rain intensity threshold, the rain advection vector intensity, and the rain advection vector azimuth.

4.1.6. Abdulrahman Model

Using a variety of non-linear regression approaches, this model [107] investigates the correlation between path adjustment factors and different physical path lengths. The rain attenuation, based on this model, can be expressed mathematically as shown in Equation (17):

where:

is the rain attenuation (dB) exceeded at p% of the time, denotes rain rate (mm/h) exceeded at p% of the time, and is the slope which can be expressed in Equation (19):

where:

4.1.7. Da Silva Model

This model [108] was primarily developed to estimate the rain attenuation in earth–space and terrestrial links. The model utilized a complete rainfall rate distribution as input and can be applied for terrestrial and slant links. A more general prediction method that includes slant links but is more suitable for terrestrial links can be represented mathematically as shown in Equation (21):

where denotes rain attenuation exceeded at p% of time, denotes rain rate (mm/h) exceeded at p% of time, and are functions of frequency, denotes the approximate effective rain rate and can each be expressed mathematically as shown in Equation (22):

For slant links, . However, for terrestrial links, and , which denotes cell diameter expressed as shown in Equation (23):

4.1.8. Budalal Model

This model [43] is best suited for short-range outdoor links in a 5G network with frequencies above 25 GHz. It can be expressed mathematically as shown in Equations (24) and (25):

where is the path length, denotes rain rate (mm/h) exceeded at p% of time, is the frequency in GHz, and is the proposed Increment Factor.

Table 5 presents the summary of works that have utilized these empirical models including the methodology adopted, method of validation, and findings.

Table 5.

Summary of Rain Attenuation Using Empirical Models.

Table 5.

Summary of Rain Attenuation Using Empirical Models.

| Ref. | Objective of Research | Methodology Adopted | Method of Validation | Result Obtained | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [43] | To investigate and modify the ITU-R P.530-17 rain attenuation prediction model for terrestrial line-of-sight at short-distance for 26 and 38 GHz at mm-wave frequencies in Malaysia. | Two links operating at 26 and 38 GHz were used to collect weather data employing a Casella rain gauge for 1 year with a 1-min integration time and path length of 300 m. | The study validated the proposed model by employing two links operating at 25 GHz with a path length of 223 m in Japan and 75 GHz with a path length of 100 m in Korea. | The results reveal that all estimations are close to the suggested prediction model. | 2020 |

| [2] | To compare five different prediction models to find the optimal rain attenuation model for 5G in Malaysia. | The research utilized a 1-year precipitation data collected from a tipping bucket rain gauge over a link of 0.2 km path length operating at 6 and 28 GHz. | The rain attenuation was calculated from the product of the specific attenuation and the path length at a rain rate of 0.01% as shown below: | Results revealed that the modified Mello model estimated a lower value for the attenuation for low and high operating frequencies. | 2020 |

| [20] | To investigate the effect of rain on short-range fixed links, that is, building-to-building transmission. | Data utilized for this research were obtained using a PWS100 high-performance disdrometer at 25.84 and 77.52 GHz. | The ITU-R and DSD models were employed to predict the attenuation due to rain expressed mathematically as: | The results showed that the ITU-R model overestimates the attenuation for lower rain rates, whereas for higher rain rates it estimates lower attenuation than the DSD model. | 2019 |

| [21] | To investigate the effect of precipitation and wet antennas on millimeter-wave transmission links operating at 28 GHz and 38 GHz Line of Sight (LOS). | The study used a 700 m path length millimeter wave link operating at 28 and 38 GHz in central Beijing. A disdrometer and rain gauge was employed to measure rainfall and the received signal level was gathered every 15 s. | A power law equation was used to calculate the expected signal attenuation (theoretical) and then compared with the measured signal attenuation (practical): | Results showed that the measured signal attenuation was 1–1.5 dB greater than expected for 28 GHz, 1.6–2.5 dB greater than expected for 38 GHz due to the wet antenna, and a signal loss of 4.2 dB was recorded over the 700 m link. | 2019 |

| [62] | To investigate the effect of rain using real-world observations on mm-wave propagation at 26 GHz frequency. | The study used a microwave 5G radio link technology with a 1.3 km path length to collect measurements logged daily. Then, every year, MATLAB was utilized to process and analyze data. | Two ITU-R models—P.530-16 and P.838-3—were employed to measure the effect of rain on the propagation of electromagnetic signals. | Results showed that the specific attenuation at 0.01% was 26.2 dB/km at 120 mm/hr. The rain rate and the estimated rain attenuation across 1.3 km was 34 dB. | 2018 |

| [109] | Improve rain attenuation estimates for 5G wireless networks operating in heavy rain zones at 28 GHz and 38 GHz. | The study used 3-year raindrop size distribution data gathered in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, utilizing a “Joss-type” RD69 disdrometer, which comprised 100,512 rainy data with a 1-min integration time. | Gamma and normalized models were used to evaluate the performance and can respectively be expressed mathematically as: | The results demonstrated that the locally determined power laws appear to be the most accurate link between specific attenuation and rainfall intensity. | 2017 |

| [94] | To compare six alternative models to find the best rain attenuation model for higher microwave bands in Icheon, South Korea. | The study used 3-year rainfall data gathered via line-of-sight terrestrial links at 38 and 75 GHz, with path lengths of 3.2 and 0.1 km, respectively, and an average sampling rate of 1 min. | The relative error margin, , was employed to evaluate the models and can be expressed mathematically as: | The analytical results showed that the ITU-R P. 530-16 model predicted accurately for both 38 and 75 GHz, whereas the Abdulrahman model predicted accurately for just 38 GHz. | 2017 |

| [19] | To investigate the impact of rain on short-range radio networks operating at the 35 GHz mmWave frequency. | The measurement was experimentally obtained from a 35 GHz radio link with a path length of 230 m to measure rain-specific attenuation and rain rate distribution. | Experiments of rain attenuation at 103 GHz with a path length of 390 m at different rainfall rates were conducted to validate the rain rate distribution. | Results after comparison showed that Wellbul distribution for raindrops is following the experiments. | 2006 |

4.2. Statistical Models

This section introduces and discusses the various prediction models in the statistical model category and reviews previous works based on these models on rain attenuation for the 5G network. A statistical model, as opposed to an empirical model, is based on statistical meteorological data analysis, and results are derived by regression analysis. Two statistical models are considered: the ITU-R model and the Singh model.

4.2.1. ITU-R Model

This model can estimate rain attenuation for frequencies ranging from 1 to 100 GHz with path lengths up to 60 km. It is based on the distance factor that depends on the rain-rate , link length, frequency, and the coefficient of the specific attenuation [47,110]. The International Telecommunication Union’s Radiocommunication Sector (ITU-R) issued some recommendations that have become the most generally used globally in estimating rain attenuation [63]. The ITU model is based on a parameter of 0.01% of the annual rain rate. Rain attenuation is caused by the overall rainfall crossing the propagation path, typically described as the integration of the specific attenuation along the path. The model gives fade depth attenuation as expressed in Equation (26):

where is the rain rate measured in mm/h and defined as of the rain rate for a specific location, is measured in and gives the specific attenuation, is the length of the link measured in km, and are functions of frequency at 20, while path adjustment factor is expressed as in Equation (27):

where gives the effective path length and is mathematically expressed as shown in Equation (28):

The model has become a worldwide baseline for evaluating research findings, though not without flaws, such as focusing on the effect of rain while ignoring the effects of other meteorological elements such as snowflakes or hail [84]. The model has further been reported to indicate a poor correlation with experimental data, especially in the tropics [111]. Furthermore, its use outside its prescribed limited frequency and rain rate ranges could inflict up to a whopping error [112]. It also features more complex computations involving high-frequency asymptotic expansion because of the inhomogeneous nature of tropical raindrop-size distributions [113,114,115]. Lastly, for wider applications, the model depends on extrapolation in respect of computations for rain spheres and rain rates, which could be a potent source of error in the tropics [116]. Because of the above limitations of the ITU-R P618-9, the latest modification—ITU-R P530-16—features the inclusion of location-tuning parameters [84]. The path reduction factor can be expressed as given in Equation (29):

The equations of interpolation for various percentages of time ranging from 0.001 to 1% are expressed in Equations (30)–(34):

where denotes the rain rate (mm/h) exceeded at p% of the time, denotes the path adjustment factor exceeded at the same percentage of the time, denotes the radio path length (km), Cn denotes the interpolation constant where n = 1,2,3, while and are functions of frequency obtained from [44]. The latest modification to the ITU-R model line, the ITU-R 530-16, has been reported to have shown significant improvement in handling attenuation, even though point accuracy is still far-fetched, and there is a need for more sustained efforts on a more realistic estimation of attenuation in the tropical and equatorial regions.

4.2.2. Singh Model

For the frequency range of 1 GHz to 100 GHz, the Singh model adopts the analytical method of ITU to determine specific attenuation, depending on the polarization type, vertical or horizontal. However, for most of the computational system requirements, the Singh model is simpler than the ITU model as it tries to do away with the requirement of determining the frequency-dependent regression coefficients, and . Due to the intricacy of the other prediction models, this is a simple mathematical model that has only square and cubic equations that are solely reliant on the frequency and rain rates. As a result, calculating the attenuation induced by higher frequencies at any given frequency and rain rate is relatively simple [63]. The mathematical representation of this model is given in Equation (35):

where denotes the specific attenuation (dB/km), denotes the frequency, and the coefficients for horizontal polarization in terms of the rain rate are given in Equations (36)–(39):

and Equations (40)–(43) are for vertical polarization:

Table 6 presents the summary of works that utilized these statistical models including the methodology adopted, method of validation, and results obtained.

Table 6.

Summary of Rain Attenuation Using Statistical Models.

4.3. Fade-Slope Model

This section discusses the different models in the fade-slope models category and reviews previous works on rain attenuation for 5G networks using these models. The fade slope represents the variation in the attenuation due to rain in terms of the attenuation level, sample time, and environmental conditions such as drop size distribution and rain type. To establish the fade mitigation measures, a fade slope is necessary. The two fade-slope models discussed here are the Andrade model and the Chebil model.

4.3.1. Andrade Model

The fade-slope variance [128] is proportional to the attenuation and can be expressed mathematically as shown in Equation (44):

where is the fade slope, denotes the rain attenuation, and is the constant of proportionality. The next level attenuation can be estimated from the current attenuation value and fade slope randomly by the predictor using Equation (45):

where denotes the prediction time; can be considered the minimum prediction time or the time of experimental sampling data.

4.3.2. Chebil Model

This model [129] can be expressed mathematically as given in Equation (46):

where is the conditional distribution of the fade slope, is the fade slope, and is the fade-slope standard deviation expressed in Equation (47):

where is the rain attenuation.

Table 7 presents the summary of research works that have used these fade-slope models including the methodology adopted, methods of validation, and results obtained.

Table 7.

Summary of Rain Attenuation Using Fade-Slope Models.

4.4. Physical Models

The physical models and a review of previous works on rain attenuation that utilized these models for 5G networks are discussed in this section. The physical models were developed based on the correspondence between the formation of the rain attenuation model formulation and the physical structure of rain events. There are three physical models, which include:

4.4.1. Crane Two-Component (T-C) Model

The model was proposed primarily for Western Europe and the United States; however, it has difficulty estimating rainfall features such as the frequency of occurrence and mean rainfall for weak and powerful rain cells. This rain attenuation prediction model presents separate procedures for heavy and mild rain statistics to account for the contributions of areas with heavy rainstorms (also known as volume cells) and larger areas of lesser rain intensity enclosing the showers (also known as debris), as for a stratiform rain event associated with Europe and America [133]. For a particular propagation path, the model adopts the existence of either a sole volume cell, debris, or both. It is targeted at calculating the probability that a certain attenuation level is surpassed, whose value might be produced by either component of the rain process (volume cell or debris). These probabilities are calculated independently and summed up to produce the desired estimate. At its simplest, the model involves the following steps: (a) propagation path determination for the global climate; (b) establishment of a mathematical link between the anticipated path length in volume cell and debris regions; (c) determinination of the expected amount of attenuation; (d) calculation of the required rain rate to produce rain attenuation; and (e) calculation of the probability that the given attenuation is set in step (c) above, given by the expression in Equation (48):

where is the desired probability that the specific attenuation is exceeded, is the probability of a cell, denotes the probability of debris, is the normal distribution function, is the standard deviation of the natural logarithm of the rain rate, and are the length scale (in kilometers) for the cell and debris, respectively, and are the cell and debris respective path lengths, and and are the rain rates for debris and cell, respectively.

The model has been reported to work for both satellite and terrestrial links. However, it has exhibited relative difficulty in determining some parameters, such as the probabilities of occurrence and average rainfall for both volume cells and debris.

4.4.2. Ghiani Model

This model [41] is based on MultiEXCELL-derived rain attenuation statistics and is a correction-based path reduction factor model for terrestrial networks. It can be expressed mathematically as shown in Equation (49):

Calculating the rain attenuation assuming the rain rate is constant throughout the transmission link in terms of the path reduction factor given by Equation (50):

Deriving the path reduction factor for the rain maps generated by the MultiEXCELL model:

It was also noted that the average path reduction factor (PF) trends followed an exponential function expressed in Equation (52):

where the symbols , , and are regression coefficients of the path length and frequency. By neglecting the effect of frequency, the rain attenuation can be expressed in Equation (53):

where the coefficients , , and can be expressed as Equations (54)–(56), respectively:

4.4.3. Capsoni Model

This model [134] is made up of multiple rain cell formations known as kernels, in which the rainfall intensity varies with distance from the center in terms of the peak intensity as expressed in Equation (57):

where is the rainfall, is the distance from the center, is the conditional average radius, and is the peak intensity; the cumulative probability of attenuation can be expressed mathematically in Equation (58):

where is the effective rain rate and .

The rain distribution can be computed using the Equation (59):

This model does not provide attenuation. However, it can be easily estimated through a synthetic rain rate employing an appropriate estimation model. The COST 205, 1985 database was used to validate the model. EXCELL has been widely used to investigate the performance of telecommunications links. However, two drawbacks associated with it are, on the one hand, the choice of exponential distribution of rain rate, which is not observed in nature, and on the other hand, the overestimation of . The enhanced EXCELL is said to work for both stratiform and convective rain. Table 8 presents a summary of work that has utilized these physical models including the methodology adopted, the methods of validation, and the results obtained.

Table 8.

Summary of Rain Attenuation Using Physical Models.

4.5. Optimization-Based Models

The optimization-based models emphasize the use of the optimization process in the formulation of input parameters for additional factors affecting rain attenuation, such as the minimum error value. This section presents and discusses three different models in the optimization-based models category as well as provides a review of previous work done using these models.

4.5.1. Pinto Model

This model is an improved variant of the ITU-R P.530-17 rain attenuation prediction model, which is likewise based on the distance correction factor as used in the ITU-R model, as well as the effective rainfall rate distribution () [137]. This model can be represented mathematically as shown in Equation (60):

where is the rain attenuation at %p of time, denotes the rain rate at %p of time, denotes the path length, and and are functions of frequency.

The model employs the quasi-Newton approach and particle swarm optimization (PSO) to reduce the RMSE. The quasi-Newton multiple nonlinear regression (QNMRN) and Gaussian RMSE (GRMSE) algorithms are used to generate the coefficients which are then fine-tuned using the PSO method.

4.5.2. Livieratos Model

This regression method relies on Supervised Machine Learning (SML) that leverages Gaussian process (GP) compatible kernel functions derived using the ITU Study Group Databank [42]. Cross-validation was employed to evaluate the performance of the model based on four kernel functions; however, the rain attenuation algorithm must be trained in a specific area of interest to predict rain attenuation in a certain geography, weather, or carrier frequency.

4.5.3. Develi Model

This model [38] was tested utilizing the Differential Evolution Approach (DEA) optimization technique at 97 GHz on a terrestrial link in the United Kingdom (UK). The model was used to show the nonlinear relationship between the inputs (rainfall rate and percentage of time) and outputs (rainfall rate and percentage of time) (rain attenuation) given in Equation (61):

where denotes the rain attenuation, denotes the rainfall rate, denotes the time percentage, and the sum of the parameters and determines the number of the input terms in the model while the parameters and are the model parameters. Equation (61) can be rewritten in closed form as shown in Equation (62):

where the function denotes the nonlinear relationship between , and . The mean absolute model error () can be defined as Equation (63):

where denotes the amount of information in the measurement set. Substituting Equation (62) into Equation (63) gives Equation (64):

The cost function for this equation is the mean absolute error, which is employed to derive the optimized error using the DEA algorithm. The mutation operation is crucial to the DE algorithm. The mutant vector can be written as shown in Equation (65):

where denotes the generation index, denotes the mutation variable, , and are three arbitrarily chosen individual indexes, and the and refer to the gene pool and the optimal entity in the population, respectively. Different works that have utilized these optimization-based models have been reviewed and presented in Table 9 including the methodology adopted, the various method of validation used, as well as the results obtained.

Table 9.

Summary of Rain Attenuation Using Optimization-Based Models.

Table 10 presents and classifies the various rain attenuation prediction models in terms of their input parameters or functions such as path length, frequency, rain rate, etc.

Table 10.

Input Parameters of the Existing Terrestrial Rain Attenuation Models.

This section has reviewed the various existing models used in modeling rain attenuation. Eventually, it grouped them into five categories: empirical, statistical, physical, fade-slope, and optimization-based models, which can be employed to estimate attenuation due to rain in tropical locations. According to the reviews, it can be concluded that none of the prediction models can be considered a complete model sufficient to accurately meet all demands for various infrastructure setup characteristics, geographic regions, or climate variations. From the taxonomy table, it can be seen that most of the models took into consideration the path length, frequency, and polarization, except the Develi model, which only considered the rain rate and time-series parameters.

5. Total Attenuation

This section examines signal attenuation due to the cloud, rainfall, atmospheric gases, and the total propagation attenuation loss, as well as providing a summary of these models and their input parameters.

5.1. Propagation through Cloud

Cloud liquid water content is another atmospheric element, apart from rain, that absorbs and scatters electromagnetic signals, especially for frequencies above 10 GHz, propagating from the sender to the receiver, causing attenuation of the signal. The impact of a cloud on signals is less than that of rain since the attenuation is determined by the cloud’s properties, such as its width, depth, and thermal readings (temperature), unlike rain which takes into consideration the communicating system’s parameters [141]. According to [142], cloud attenuation can be measured or quantified using the liquid water content and can be mathematically expressed as shown in Equation (66):

where is the liquid water content, is the angle of elevation, and cloud-specific attenuation coefficient, which can be expressed mathematically as shown in Equation (67):

where is the complex dielectric permittivity of water contents within the cloud.

where and denote the principal and secondary relaxation frequencies, respectively, is the temperature, and the values of and are 5.48 and 3.51, respectively.

5.2. Propagation through Rain

Rain, one of the main dynamic natural occurrences, reduces the power of transmitted electromagnetic signals due to absorption and dispersion depending on the rainfall rate and the physical structure, such as the width, height, and number of droplets that the signal passes through [34,142]. The universal power-law model used to describe the rain attenuation and specific attenuation are provided in Equations (6) and (7). The relationship between the path length () and the path reduction factor () is also provided in Equation (29). The power-law parameters and can be derived using the following Equations (73) and (74):

The rain rate can be derived in terms of the total depth of water droplets caused by rain (mm) and the total time of rainfall (hrs.) as expressed in Equation (75):

5.3. Propagation through Atmospheric Gases

Numerous gases, including oxygen and water vapor, are present in the atmosphere. These gases have varying heights, loftiness, and breadths, resulting in varying degrees of multipath attenuation of electromagnetic signals [34]. The attenuation caused by oxygen can be distinguished from all other atmospheric impairments. Its impact is consistent across all regions and it is not dependent on any meteorological parameters, unlike the attenuation due to water vapor which absorbs and scatters the signal and is based on meteorological properties such as temperature, water vapor content, and height above sea level [143]. According to [144], the attenuation caused by water vapor (for ) and oxygen (dry air) can be calculated, respectively, as shown in Equations (76) and (77):

where denotes the attenuation caused by water vapor, denotes the frequency (GHz), , , is pressure, is temperature, and is the attenuation caused by oxygen. The total attenuation due to atmospheric gases for both uplink and downlink transmission can be expressed as shown in Equation (78):

where and are the equivalent height for oxygen (dry air) and water vapor, respectively, and denotes the angle of elevation.

5.4. Propagation through Radome

A radome, coined from the two words radar and dome, is a weatherproof enclosure constructed of structural plastic to protect the surface of an antenna, such as a microwave or radar antenna, from external environmental disturbances like wind, rain, ice, sand, and ultraviolet rays, and also to conceal the electronic equipment of the antenna from the public [145,146]. The radome can attenuate the receiving and transmitting signals, especially when wet; hence, it should be constructed using low-permittivity materials, shaped to achieve good transparency for the desired frequency, and hydrophobic-coated to avoid additional attenuation due to the wet radome surface [147,148]. Attenuation due to radome occurs by reflection and absorption based on the signal frequency as well as the thermal reading (temperature) and width of the water slab [149]. A simple model was utilized by [150] to calculate the overall radome attenuation through a two-layer structure and expressed as in Equation (79)

where and denote the electrical thickness of the radome and water layers, respectively, expressed as given in Equations (80) and (81):

where denotes the free-space wavenumber, denotes the complex relative dielectric constants of the radome material, denotes the complex relative dielectric constants of the water at the X band, while and denote the physical thickness of the radome and water layer, respectively.

and denote the respective transmission and reflection coefficients for the electric field at the (1) air–radome, (2) radome–water, and (3) water–air interfaces, and expressed as shown in Equations (82)–(85):

The thickness of water, according to [149], can be related to the rainfall rate using Gibble’s Equation (86):

where is the thickness of the water layer, denotes the kinematic viscosity of water (kg/m/s), denotes the radius of the radome, denotes the rainfall rate, and denotes the gravitational acceleration.

5.5. Total Propagation Attenuation Loss

The total attenuation is a critical parameter to consider as it provides the necessary information for effectively designing communication links such as Earth–satellite and terrestrial communication links. The total attenuation, as defined by [45], is the sum of the individual attenuation parameters, including attenuation caused when the signal propagates through free space, clouds, rain, atmospheric gases, radome, etc. Hence, the total attenuation can be mathematically expressed as shown in Equation (87):

where is the attenuation loss due to non-line of sight, denotes the free space attenuation as expressed in [151], denotes the attenuation due to cloud Equation (66), attenuation due to rain Equation (6), attenuation due to atmospheric gases (dry air and water vapor) Equation (78), and attenuation due to radome Equation (79).

Table 11 presents the various input parameters of the different atmospheric impairments models as well as radome for total attenuation.

Table 11.

Input Parameters of the Atmospheric Impairments Models for Total Attenuation.

5.6. Review of Total Attenuation Models

This section reviews various signal propagation models used to calculate attenuation as signals travel through various media, including free space, clouds, rain, radomes, and atmospheric gases (water vapor and dry air). These are summarized in Table 12, Table 13 and Table 14 for propagation through the cloud, atmospheric gases, and radome, respectively.

Table 12.

Summary of Attenuation through the Cloud.

Table 13.

Summary of Attenuation through Atmospheric Gases.

Table 14.

Summary of Attenuation through Radome.

6. Specific Attenuation

This section presents and discusses the specific attenuation models calculation based on rainfall, atmospheric gases (oxygen and water vapor), and clouds.

6.1. Specific Attenuation Model Due to Rainfall

As described earlier, Equations (6), (7), (29), and (73)–(75) provide detailed relationships of specific attenuation (dB/km) due to rainfall across terrestrial communication channels and also the relationship between the specific attenuation and rainfall rate, frequency, and polarization characteristics.

6.2. Specific Attenuation Model Due to Atmospheric Gases

The specific attenuation due to atmospheric gases, according to [144], can be precisely calculated as the sum of the individual spectral lines from oxygen and water vapor at any value of pressure, temperature, and humidity along with a few additional parameters as shown in Equation (88):

where and denote the specific attenuation (dB/km) for oxygen and water vapor, respectively, denotes the frequency (GHz) while and are the imaginary parts of the frequency-dependent complex refractivity expressed as in Equations (89) and (90):

where denotes the strength of the th oxygen or water vapor line, denotes the oxygen or water vapor line shape factor, and denotes the dry continuum due to pressure-induced nitrogen absorption and the Debye spectrum as given by Equation (91). That is,

where denotes the width parameter for the Debye spectrum expressed in Equation (92):

The line strength can be obtained for both dry air and water vapor using the following Equations (93) and (94):

where is the temperature in Kelvin, , denotes the oxygen pressure (), and is the water vapor partial pressure (). Hence, the total barometric pressure can be expressed in Equation (95):

6.3. Specific Attenuation Due to Clouds

It has been shown in [162] that the Rayleigh Scattering Approximation is accurate for frequencies up to 200 GHz for clouds or fog that contain predominantly small droplets of diameter less than 0.01 cm and the specific attenuation due to the cloud can be expressed in Equation (96):

where denotes the specific attenuation within the cloud (dB/km), denotes the frequency, denotes the cloud liquid water temperature (Kelvin), denotes the liquid water density in the cloud or fog (g/m3), and denotes the cloud liquid water-specific attenuation coefficient, which can be represented mathematically as Equation (97):

Table 15 presents the various input parameters of the different atmospheric impairments models for specific attenuation.

Table 15.

Input Parameters of the Atmospheric Impairment for Specific Attenuation.

6.4. Review of Total Attenuation Models

This section reviews various signal propagation models used to calculate specific attenuation as signals travel through various media, such as clouds, rain, and atmospheric gases (water vapor and dry air). Table 16 presents the summary of specific models.

Table 16.

Summary of Specific Attenuation Models.

The power law has been used to calculate rain attenuation since the 1940s and is still being used to estimate the attenuation by network designers and operators. The ITU-R standard has provided a simplified technical standard that guides the establishment of the power-law based correlation between the attenuation due to rain and the rainfall rate (P.838-3). More recently, the power law was explored for monitoring rainfall occasioned by the availability of attenuation data collected from the Commercial Microwave Networks (CMNs) backhaul infrastructure. This advancement has paved the way for opportunistic surveillance instruments that require little or no additional hardware or cost. Also, more recently, supervised machine learning (SML) is gaining traction in the quest for calibrating the power-law parameters.

7. Review of Different Methods of Model Validation

This section presents a review of different model validation methods and summarizes model validation techniques.

In the literature, when new mathematical models are developed, there is usually a means to validate the model. For rain attenuation, the models are subjected to different validation tests to determine their ability to predict rain attenuation. According to the ITU-R, there are standard procedures for testing the validity of mathematical models developed for rain attenuation predictions. As a result, it is necessary to analyze some of these models to determine the current and future developments in this area. Some of the works of literature in this field were noted in [165]. In this context, this study has executively selected four model validation methodologies based on the recommendation of the ITU-R [166] which are available in the literature. The methodologies are (I) an input-to-output correlation or coefficient of determination, (II) Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and RMS functions, (III) goodness-of-fit function, and (IV) Chi-square models.

The coefficient of determination function is defined as the total variations in a proposed model or, in some cases, multiple regression models. Mathematically, it is defined in Equation (98):

Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) is utilized to measure the difference in numerical estimation and can be expressed mathematically as given in Equation (99):

Another variant of the RMSE function is the Spread-Corrected RMSE (SC-RMSE) as expressed in Equation (100):

where:

The goodness-of-fit function can be used to test how well the developed model observed data fits the predicted data and this can be expressed in Equation (102):

In some cases, this is called the Pearson goodness-of-fit function, and the expression for this is defined in Equation (103):

where is the observed count in cell and is the expected count in the cell when .

Chi-square can also be used to validate developed models and can be expressed mathematically as defined in Equation (104). The Chi-square statistics were employed to evaluate the method’s performance.

The difference between the predicted rain rate value and the measured rain rate value is given by relative error () expressed in Equation (105):

where : is the predicted value and is the measured rain rate estimated for . The maximum error and the mean error can be expressed mathematically as shown in Equations (106) and (107), respectively:

Rank Correlation,

This measures the strength of the relationship of related data. It does not assume measurement for statistical dependence between the measured and predicted; hence, it is non-parametric. Mathematically, it can be expressed as shown in Equation (108):

where are mean measured and predicted rain rates for .

Table 17 presents the properties of the various existing rain attenuation models based on the thresholds for each parameter considered when developing the models including the predicted rain attenuation value range.

Table 17.

Properties of the Existing Rain Attenuation Prediction Models.

From Table 17, it can be seen that rain attenuation increases with increasing rainfall rates. Furthermore, as the time percentage increases, the rain attenuation values decrease. For example, at p = 1%, the attenuation value can be as low as 1.01 dB, whereas the attenuation can be as high as 40.48 dB at 0.001% [94]. However, according to ITU recommendations, a low value for the standard deviation and root mean square (RMS) for the majority of time percentages indicate that the proposed model is highly accurate [167].

Table 18 presents a summary of some works that have successfully utilized any of the aforementioned model validation techniques to evaluate the performance of their respective proposed models.

Table 18.

Summary of Model Validation Techniques.

From Table 18, it is clear from the method of validation that root mean square (RMS) is the method that most of the researchers are using to test the accuracy of the developed models. Some methods that have not been given attention are the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and the Anderson–Darling tests.

8. Machine Learning-Based Rain Attenuation Prediction Models

This section presents the reviews of machine-learning-based rain attenuation prediction models that have been proposed to date (August 2022) and a taxonomy. Also, a brief review of the issues with aerial communication is provided. Table 19 summarizes the machine learning-based rain attenuation models.

Table 19.

Summary of Machine Learning-Based Models.

Findings from Table 19 indicate that machine learning models are simple and can accurately predict rain attenuation. However, it can also be seen that the performance of most of the machine learning-based models developed was evaluated against a statistical model, the ITU-R model of which the ML-based model performs better.

Table 20 presents the various machine learning-based models considered in the literature.

Table 20.

Machine Learning-Based Models Considered in the Literature.

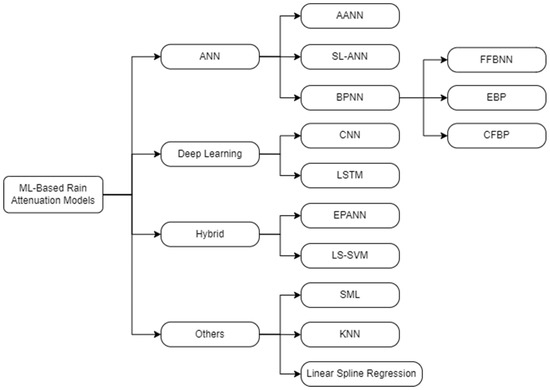

From Table 20, it can be seen that only a few ML-based rain attenuation models have been developed and evaluated; hence, there are still gaps to fill this research area. Figure 6 shows the taxonomy of the machine learning-based rain attenuation models considered in the literature.

Figure 6.

Taxonomy of the Machine Learning-Based Rain Attenuation Models.

Aerial Communication

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), popularly known as drones, are self-contained and can fly autonomously or be controlled by base stations. These autonomous node applications offer intriguing new approaches to completing a mission, whether related to military or civilian operations such as remote sensing, managing wildlife, traffic monitoring, etc. [185]. UAV communication has become an integral part of the development of the 5G and beyond network; however, one of the major application challenges faced by 5G and beyond UAV communication is weather and climate change. In [186], aerial channel models, precisely the air-to-ground channel models for different meteorological conditions such as rain, fog, and snow were investigated within a frequency range from 2–900 GHz based on the specific attenuation models for the different meteorology conditions. The results showed that rain and snow are very severe for mm-wave and THz bands, respectively. The effect of rain on the deployment of a UAV as an aerial base station in Malaysia was studied in [187] where the antenna height of the user, attenuation due to rain, and high-frequency penetration loss were considered for both the outdoor-to-outdoor and outdoor-to-indoor path loss models. The study utilized two algorithms known as Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Gradient Descent. The results obtained indicated that the PSO algorithm requires less iteration to converge compared to the GO algorithm and that the effect of rain attenuation increases for higher frequency which results in a corresponding need for the UAV to increase its transmit power by a factor of 4 and 15 for outdoor-to-outdoor and outdoor-to-indoor, respectively.

9. Fade Mitigation Techniques for 5G

Fade mitigation techniques (FMTs) are adaptive communication systems employed to correct in real time the effect of attenuation on slant path [188]. Fading has three major effects: rapid fluctuations in signal strength over short distances or intervals, alterations in signal frequency, and multiple signals arriving at different times. Signals are spread out in time when they are put together at the antenna. This can result in signal smearing and interference between received bits.

Due to high rainfall in tropical climates, a signal is attenuated, and this signal attenuation can be decreased utilizing FMT. To regulate FMT approaches in real-time, there is the need to first understand the dynamic and statistical features of attenuation due to rain, which is the major source of channel or path loss, especially when the frequency exceeds 10 GHz [189]. Several methods to mitigate attenuation at the physical layer are classified as Power Control, Adaptive Waveform, Diversity, and Layer 2. The power control, adaptive waveforms, and Layer 2 techniques benefit from the system’s idle excess resources, whereas the diversity technique uses a re-route method. With the sharing of idle resources, the main aim is to make up for the fading of the link to sustain or optimize the performance. The diversity technique, on the other hand, can preserve the performance of the link by altering the geometry of the link or the frequency band [190].

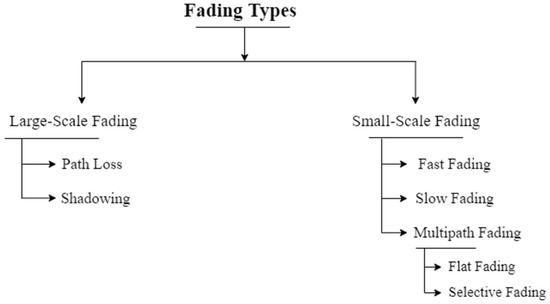

9.1. Types of Fading

The different types of fading, as shown in Figure 7, are given considering the various channel impairments and positions of the transmitter and receiver.

Figure 7.

Different Types of Fading.

9.1.1. Large-Scale Fading

Path loss produced by the impacts of the signal traveling over broad areas is referred to as large-scale fading. The presence of noticeable topographical characteristics such as mountains/hills, trees/forests, billboards, clumps of buildings, etc., between the transmitter and receiver affects this phenomenon [191]. Path loss and shadowing effects are included in large-scale fading.

- A.

- Path Loss

As signals propagate through the medium over a long distance, the signal strength decreases with an increase in the distance. This is referred to as path loss or attenuation [151]. The amplitude of signals spreads as they propagate through the medium and, if not compensated for, the signal would become unintelligible at the receiving end. This loss is independent of the communicating parameters such as the transmitter, the type of medium, or the receiver, although it can be mitigated by increasing the area of the receiver’s capture [191].

- B.

- Shadowing

This refers to signal power loss caused by obstructions in the propagation route. Shadowing effects can be used to reduce signal loss in various ways. One of the most effective is LOS propagation. The EM wave frequency also affects shadowing losses. EM waves can pass through different surfaces but lose power, i.e., signal attenuation. The type of surface and the frequency of the signal determine the amount of loss. In general, as the frequency increases, the penetration power of a signal decreases.

9.1.2. Small-Scale Fading

Small-scale fading describes the substantial variations in the phase and amplitude of a signal that can occur due to minor variations in the spatial separation between a transmitter and receiver [191]. Small-scale fading occurs when the intermediate components in the signal’s path change. Multipath propagation, motion between sender and destination, surrounding object speed, and signal transmission bandwidth are all physical elements that cause small-scale fading. Small-scale fading in the radio propagation channel is influenced by the physical causes highlighted below:

- Multipath propagation

This is one of the elements that contribute to radio signal deterioration. Because of the irregularity in the atmosphere, the Point Radio Refractive Gradient (PRRG) varies with height, time of day, and season [192]. As a result of this phenomenon, radio waves arrive at the receiving antenna via two or more routes. Because of this inter-symbol interference, the time the signal takes to reach the destination becomes lengthened. Effects of multipath include constructive interference, destructive interference, and signal phase shifting.

- 2.

- Speed of the mobile

The effect of the various doppler shifts on multipath components is random frequency modulation between the base station and the mobile. Doppler shift is positive when receiving mobile travels toward the base station, and it is negative otherwise [192,193].

- 3.

- Speed of surrounding objects

The effect of objects being in motion in the radio channel is a Doppler shift based on varying times on the multipath components. However, if the neighboring objects move faster than the mobile, this effect precedes fading [193].

- 4.

- Transmission bandwidth of the signal

If the bandwidth of the transmitted signal exceeds the “bandwidth” of the multipath channel—which is measured by the coherence bandwidth—distortion will occur on the receiving signal, although fading would not occur over a small distance. However, if the bandwidth of the transmitted signal is lower than the bandwidth of the multipath channel bandwidth, there would not be a distortion of the received signal, but its signal power changes frequently. The coherence bandwidth, related to the channel’s unique multipath structure, is used to quantify the channel’s bandwidth. Coherence bandwidth is defined as the estimate of the maximum frequency for which the signal is in relation to the amplitude [192].

The types of small-scale fading include the following:

- A.

- Frequency selective fading: The signal is transmitted and received via multiple propagation paths, each with relative delay and amplitude variation. Multipath propagation occurs when different regions of the transmitted signal spectrum are attenuated differentially, resulting in frequency selective fading. The channel spectral response is not flat in this case, but exhibits dip or fade in response to reflections canceling particular frequencies at the receiver.

- B.

- Frequency non-selective fading: Frequency non-selective fading, also known as flat fading, occurs when all signal component frequencies experience nearly the same amount of fading. Such fading occurs when the transmitted signal’s bandwidth is less than the channel’s coherence bandwidth. If the symbol period of the signal is greater than the RMS delay spread of the channel, then the fading is flat.

- C.

- Slow fading: Slow fading can occur as a result of occurrences such as shadowing, which occurs when a significant object, for example, a mountain/hill or a billboard, obstructs the path of the signal between the source and destination. It occurs over time and alters the received signal mean value. It is mostly concerned with moving away from the source and observing the estimated decrease in the intensity of the signal.

- D.

- Fast fading: In this case, the signal suffers from frequency dispersion due to Doppler spreading, which causes distortion. Fast fading is based on the speed of the mobile and the bandwidth of the transmitted signal. Due to the rapid changes in the channel, which is more than the signal period, the channel alters in one period.

9.2. Power Control Technique (PCT)

The PCT-fed mitigation concept is divided into four: (i) Up-Link Power Control (ULPC), (ii) End-End Power Control (EEPC), (iii) Down-Link Power Control (DLPC), and (iv) Onboard Beam Size (OBBS). However, in case the rain fade lasts a long time and is expensive, then the power control strategy demands high power capacity because the satellite transmitter that provides coverage to a diverse set of customers in various geographical regions must continuously operate at, or close to, the maximum power to mitigate the attenuation experienced by just one of the ground stations [190].

9.3. Adaptive Waveform

The primary idea that regulates adaptive transmission is to maintain a constant Eb/No by adjusting transmission parameters such as power level, symbol rate, modulation order, coding rate/scheme, or any combination of these parameters [194]. Adaptive Waveform is classified into three stages, which are: (i) Adaptive Coding (AC), (ii) Adaptive Modulation (AM), and (iii) Data Rate Reduction (DRR) techniques [195,196,197].

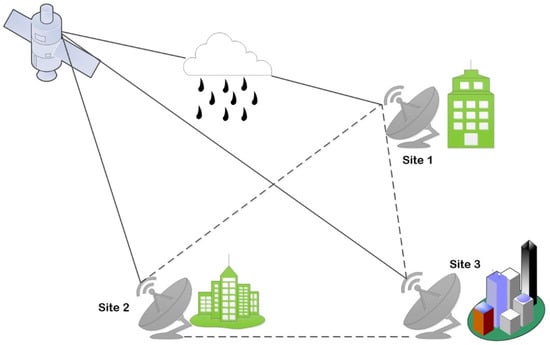

9.4. Diversity Reception Techniques

The diversity reception technique compensates for fading channel impairments and is typically achieved, for example, by using two or more receiving antennas. The diversity technique is employed to mitigate or compensate for fades experienced by the receiver. Base stations and mobile receivers can both use diverse approaches. These strategies aim to reroute signals within the network to mitigate network disruptions caused by atmospheric perturbation. Diversity is of three types: site diversity (SD), satellite diversity (SatD), and frequency diversity (FD) [188]. These procedures are quite costly since the related equipment must be redundant. Some of these techniques are applied [88] where a frequency diversity model has been used to reduce signal attenuation in heavy rainfall zones. The FD is used to overcome the rain fade in microwave point-to-point links as discussed in [198]. Figure 8 depicts the site diversity technique which consists of linking two or more ground stations that are receiving the same signal so that if the signal is attenuated in one area, another ground station can compensate for it.

Figure 8.

Illustration of Site Diversity Scheme.

9.5. Frequency Variation Correction Factor

Frequency variation performance can be defined in terms of the outage percentage of time [88]. The variation correction factor [189,193] can be expressed mathematically as shown in Equation (109):

where denotes the outage percentage of an exact fade margin with no variation, and denotes the outage percentage with the same fade margin in the variation frequency.

From Equation (109), the correction factor depends on the outage level at the required attenuation, frequency separation, and diversity frequency. The specific attenuation for the frequency is considered the starting point of the correction factor development [189]. A diversity correction factor model was proposed in [199] with a frequency separation of 5 GHz based on the fading margin required for system design. The result showed a significant improvement within the frequencies ranging from 5 to 15 GHz, with no improvement above 15 GHz. However, a model for any frequency separation and path length for microwave communications is required.

9.6. Mitigation Techniques at Layer 2

At the layer 2 levels, FMTs do not try to mitigate a fade occurrence but instead rely on message re-transmission. At layer 2, two distinct approaches are possible: Automatic Repeat Request (ARQ) and Time Diversity (TD).

9.6.1. Automatic Repeat Request (ARQ)