Abstract

Approaching the ecological agriculture topic in the context of European Policies to accelerate the conversion to those policies is an interdisciplinary challenge. The motivation to develop this subject is based on the longitudinal observation that the ecological agriculture evolution in Romania has been very slow, despite the policies aimed to accelerate the transition from the conventional to the ecological agriculture have been supported since the 2000s. The goal of the paper is to reframe the available data to evidence the slow dynamics of the organic farms’ certification. The methods used are descriptive and numerical analysis, supplemented by a qualitative-transversal interpretation. The research work has been carried out on the dynamic analysis of the ecological agriculture progress in Romania, based on the data with the ecological certification of the specialized companies (2019–2021). The main hypothesis: the slow dynamics are caused by subjective barriers. The results confirm the slow dynamics of ecological certifications due to some limits and barriers to understand the real role and benefits from the ecological agriculture. In this context, the European Union Organic Action Plan for 2021–2030 proves to be a stimulus for the Romanian ecological agriculture.

1. Introduction

The idea of the present paper has started from the general observation that ecological agriculture does not benefit from a high level of interest and applicability in the Romanian market, despite of the natural appropriate conditions and the stimulative European policies. The observation originates from the practical reality and the official reports and data on this topic, too. The design of the paper is based on the goal to support this affirmation by official data of the Agriculture Ministry related to certificated organic farms and import–export balance with ecological products. The direction followed in this paper is to reorganize and present the data in a clear manner to demonstrate that the mentioned observation, perceived as a hypothesis, can be proven. The analysis, supported by collected data and confirming reports, starts from the finding that, in Romania, the dynamics in the ecological production sphere is rather slow, even too slow, as compared to the local production potential. Another finding is related to the extremely unbalanced scale between the import and export of ecological products. Taking these results into consideration, the paper will pursue some causes of the slow dynamics of the ecological certification in agriculture. The hypothesis is connected with the results of some reports at the European level. All these consider the population interest and behavior to buy organic food and by this to support the ecological agriculture. The identification of the connection between the ecological agriculture issue and consumer behavior is not an easy task, the main difficulty being posed by the individuals’ limited knowledge of the environmental components [1]. Even at the theoretical level, the ecological behavior and interest for organic food is accepted by consumers, in practice, it does not always generate a sustainable consumption behavior [2]. It is well known that the Romanian organic food market has a positive trend, but the consumption rate is still very low [3]. Based on the data and information, as results of the studies regarding the ecological agriculture progress at the European level, the topic was analyzed in terms of the evolution of the organic farm certification in Romania.

To understand the essence of the ecological agriculture, the consumption of energy and materials should be taken into account that increase with the population number and the living standards, with harmful consequences such as climate change, natural resources depletion, environmental degradation [4]. Therefore, the main sources of biomass as part of the orientation to the ecological agriculture (energy crops, agricultural waste, forestry, organic waste) can be considered and the contribution of the beekeeping with a great capacity to achieve all the 17 Sustainable Development Goals [5,6], including the sustainable systems of production and consumption [7]. For this reason, the topic equally presents an interest to specialists from the technical field, i.e., production and processing; trading, namely selling and consumption; psycho-social, through the motivations and attitudes towards consumption; political decisions or regulations from the European level, regarding the stimulation of ecological production; and marketing, through the demand–supply or production–consumption relation, specific for the market of products deriving from the ecological agriculture.

The ecological agriculture generates multiple benefits for producers as well as for consumers: food safety, environment protection, resource and landscape conservation, employability, new business opportunities. Meanwhile, the understanding of the motivations beyond the ecological food consumption behavior is essential to stimulate the ecological consumption, production, decision making (including the political ones), as well as to stimulate the development of an ecological production market [8,9].

Related to the intention to buy the products from the ecological agriculture, the main reason for achieving the ecological food consumption is individual health, especially since there is growing concern related to the impact on the environment of an unbalanced and intensive consumption of goods, including food, especially “super foods” [10,11]. However, to determine the sustainable consumption from the ecological agriculture, the consumers must know that their purchasing behavior has a direct impact on many ecological problems [12], and therefore, it is necessary to identify the main barriers in ecological consumption, as well as the factors influencing the increase in demand for this category of food products [2]. The increasing consumption demand for the ecological agricultural domain has led to the natural habitats being converted into production fields, which is why the sustainable agriculture imposes an evolution from three perspectives: as a production system to attain food self-sufficiency; as administration concept; and as a vehicle to support the rural communities [13,14].

Numerous studies in the field are oriented towards a pro-ecological approach in the agriculture. The documentation from the field literature has yielded no reference to conclude the lack of opportunity to adapt the traditional production and consumption system to the ecological one. At the European level, one of the most known policies is that of agriculture sustainability. The main goal of “Organic 3.0” is that to allow the adoption, on a large scale, of the sustainable agricultural production systems, of developing ecological consumption markets, and of promoting new production and consumption holistic systems [15]. The orientation to an overall sustainable future is one of the goals proposed by the European Union’s 2030 Agenda. The sustainable consumption is perceived as one of the strongest pillars for a sustainable development [16].

Another aspect is the need to change the food consumption pattern, seen as a chance for stimulating the ecological agriculture in Romania. The reconfiguration of the demand–supply relationship and the consideration of the way in which consumers are involved in supporting the ecological agricultural production are vital. The health and the sustainability undeniably become the pillars of the ecological agriculture. Individuals are more motivated to consume ecological products since, in their opinion, this allows them to maintain a healthier lifestyle; so, the ecological agriculture may contribute to the improvement of public health and to the ensuring of the cohesion in rural areas [17,18]. Hence, the pro-ecological orientation is theorized as an important predictor of the ecological consumption behavior. The analysis of the ecological product consumer’s behavior should take into account what the consumers think, what the consumers feel, what the consumers do, and what factors influence their behavior [12,19]. The aspects that materialize the appreciation of the environment, based on categories of individuals, groups, or countries, which generated the idea of valorization and ecological products’ consumption, are seen as ecosystem services, to spark increasing interest for even more categories of consumers [20].

Similarly, to the terms “organic” or “biological agriculture” used in other states, the term “ecological agriculture” has been chosen in Romania to define its role in producing healthier foods, connected with the responsible management, whose “peak” of consumption has not been reached yet according to the experts [21]. The ecological agriculture is undoubtedly a dynamic and continuously developing system, based on the agroecology science. It ensures profit to producers, improves the soil fertilization, protects biodiversity, and manages in a balanced manner the environment, and consequently, the future of the ecological agriculture will decisively depend on the consumers’ demand [21,22].

The supporters of the ecological agriculture disseminate the principles and recommendations to encourage the development of such agricultural exploitations, especially since the perceived authenticity of the ecological food depends on their taste, on quality, on the labeling manner, etc. [23,24]. In the context of resuming the sustainability policies, agriculture has been confronting with new challenges, to produce more, to pollute less, and to distribute better [25]. In Romania, the financial aid granted to active farmers registered in the ecological agriculture system is awarded in two ways: (i) the conversion to the ecological agriculture methods; (ii) and the maintenance of the ecological agriculture practices [26]. The present agricultural policies, in line with those of sustainability, are oriented to support the sustainable producers, processors, and traders. The Community Agricultural Policy (CAP) supports the ecological agriculture sector through regulations, norms, and standards, as ecological agriculture certification, within the frame to manage sustainable and ecological crop systems, grant food safety, environment protection, and natural resource valorization, together with consistent investment in the rural area [27,28]. Romanian farmers express a great potential to increase the ecological agriculture, but not in all by self-determination, because there are the influences of the subsidies from common agricultural policy and the external commercial relation with organic products [12].

This paper, a scientific communication, considers a subject of ecological agriculture, which is topical and of interest to several fields. Conceived in the way of a simple model of an information chain, information transmission, and data interpretation, the present communication is based on interaction and relationships between ideas, all these having the effect of reducing uncertainty regarding the chosen study subject. The main purpose of the paper is to clarify and highlight the importance of the topic chosen for the study. The motivation for the choice of the topic is given by a set of findings of the stage in which the conversion to organic farming is. In fact, a set of ideas was collected that were reorganized and presented in a new, clearer light, marking the topicality and importance of the subject. The course that allowed the establishment of the work process was identification and presentation of the problem under discussion, presentation of the authors’ point of view, argumentation of the topic with references from the specialized literature, presentation of the results of the interpretation and related discussions. An important motivation to elaborate the paper is based on some identified gaps such as the limited literature on the subject of organic farming certifications; summary or unclear data and reporting to conclude the dynamics of the ecological certification process; the non-uniformity of the reported data, and inadvertences with the data from Eurostat; only a few approaches in the specific literature regarding the link between ecological behavior, sustainable development and objectives of conversion to organic agriculture. For all these, the novelty and contribution of the paper consist in the approach of a new and exciting study topic: ecological certification, consideration of this topic by association with that of European policies from the “Organic Action Plan for 2021–2030”, both of the most up-to-date, and the creation of connections with basic aspects of ecological consumption behavior. About the methodology of the work, the method of management and analysis of the data collected from the official reports on ecological certification in Romania (Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development) were collected, grouped and reorganized in a single dashboard, so that the dynamics and fluctuations of the process of ecological certification, as a result of the interpretations made; moreover, it was considered for analysis not only of certified economic units, but also of authorized certifiers and the organized data were analyzed by association and comparison with similar data from EC and Eurostat reports.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology and Context

The main topic reflected in this paper is: how the transition to the ecological agriculture in Romania has evolved, which is the Romanian perspective regarding the certification of ecological farms, and which influence the European policies supporting the ecological agriculture, as a pillar of sustainable agriculture, have on the Romanian farmers.

According to the European Commission proposals, the care for the environment, climate, landscape and the natural resources will represent an essential component of CAP, materialized in the following objectives [29]:

- -

- Contribution to the sustainable energy, to diminish the climate changes and to promote adaptions to the latter;

- -

- The promotion of sustainable development and efficient management of the natural resources;

- -

- The contribution to the protection of biodiversity, improvement of ecosystem services, and conservation of habitats and landscapes.

Today, the European Union (EU) ecological market is relatively dynamic, having growth rates that vary from country to country. The development perspectives are due to the innovating character of the products derived from the ecological agriculture, the increasing support of the European policies, the consumption demand increase, the change of perception and the pro-ecological behavior; thus, the level of ecological products consumption reached in 2020, as European average, 102 Euro/inhabitant [30].

The European Commission constituted the ecological agriculture regulatory framework by means of the most comprehensive plan of ecological action for the EU, the “Organic Action Plan for 2021–2030” through which it will monitor the achievement of the “European Green Deal” goal of ensuring a 25% area occupied by agricultural land intended for the ecological agriculture till 2030, an aspect that correlates with the demands of ecological agriculture contribution to solve the problems pertaining to sustainability of the demand–supply ratio of products derived from ecological production systems [31,32].

In order to confer a solid status to the action plan relevant to ecological agriculture, in 2021, at EU level, a public consultation took place as a market survey regarding the adequacy of this plan. The consultation had a significant effect to clarify the aspects related to the necessity of increasing ecological production, the stimulation of the ecological products demand, and the adoption of a “pro-environment” behavior. There were 840 answers to this open public consultation and the respondents belonged to 41 countries, all from the EU and non-EU, with EU citizens offering the highest contribution (52% from the total of respondents), whereas the profile of the respondents varied from business organizations (16%), business associations (8%), NGOs (6.07%), academic and research institutions (4%), and public authorities (4%) to environment organizations (1%). The results of the study indicate the following: 78% of the respondents acknowledge the presence of obstacles to greater production and consumption of organic food in the EU. This conclusion is in line with the low dynamics and the progress difficulties of the ecological agriculture in Romania, an aspect that will be emphasized in the presentation of our results.

The obstacles in the progress of the ecological agriculture perceived as the most important are [33]:

- -

- Insufficient financial incentives for producers to convert to organic production (76%);

- -

- Competition with other ways of producing and/or other schemes (74%);

- -

- Low consumer awareness of the benefits from organic production for climate and environment (73%);

- -

- As much as 63% of the respondents deem that organic food is too expensive for consumers;

- -

- A lack of consumer awareness of the EU label (63%);

- -

- Too many ecological food schemes that can be confused with organics (59%);

- -

- There is a very large consensus to support the actions proposed for stimulating the production of organic products (from 74% to 91% of the replies).

Regarding the ecological agriculture perspectives for the 2030 horizon, the largest share of respondents, which agree with the financial support through the CAP in order to stimulate the conversion from conventional to organic farming, indicates:

- -

- The importance to provide sufficient training and advice to stimulate conversion into organic farming (91%);

- -

- The necessity to strengthen local and small-scale processing and foster short supply chains (90%);

- -

- The recognition of the need for organic producers to receive support to improve their bargaining power in the supply chain (88%);

- -

- The need to improve information and data related to developments in the organic market, to facilitate decisions for producers (87%).

About the question on the main environmental advantages of ecological production, the respondents identified the beneficial effects of organic production in relation to [33]:

- -

- Biodiversity (92%);

- -

- Protection of the soil quality (88%);

- -

- Protection of the water quality (84%);

- -

- Promotion of the circular economy (83%);

- -

- Responsible use of energy and natural resources (80%);

- -

- Promotion of the carbon neutrality, and adaptation to a changing climate which helps reduce air pollution (78%).

Based on the EU official specific reports for the “Green Deal 2030” regarding the conversion to the ecological agriculture for 25% of the agricultural land till 2030, in 2019, the ecological agriculture area was of only 8.5% from the total EU agricultural land; therefore, we consider that the goal to attain 25% is pretty bold. However, within 10 years (2009–2019), the ecologically cultivated area in the EU has increased by 66%. Romania is situated on a deficient position with only 2.9% ecologically cultivated area in 2021. Nevertheless, among the best European results regarding the progress of ecological agriculture in accordance with the sustainability demands, there are [34]:

- -

- The increase of biodiversity, with 30% on the ecological farms’ areas;

- -

- The maximization of the pollination benefits;

- -

- The limitation of using fertilizers, herbicides, and pesticides;

- -

- The improvement of animals’ living conditions.

Therefore, the European agriculture will undergo, starting from 2022, three major modifications, especially since an extremely important regulation was issued, but the following inputs should be first approved in conventional agriculture and, then, in ecological agriculture [35]:

- -

- New restrictions for the use of ecological inputs, mainly of fertilizers and pesticides;

- -

- The marketing of organic and organic-mineral fertilizers in all the EU member states without the necessity of obtaining marketing approval/authorization from each member state;

- -

- The obligation of farmers from the EU member states to retain the carbon in the soil.

These aspects will allow the understanding of the most important modeling references of the ecological products consumers’ behavior and will offer an analytical detailed framework for the analysis of the behavior changes of the ecological food and consumer products [36]. An established approach of the consumer’s behavior is based on the theory of behavioral decision, given that the consumers’ perception regarding welfare can have a greater impact on the eating habits and can support a more holistic assessment of a product compared to the general assessment or the preoccupation with the protection of the environment [37,38]. Some established models which have pursued the connection between the consumption behavior and some environment-related aspects have been comprised in three specific theories: Schwartz’s Theory (1992, 1994) of activating norms; Ajzen’s Theory (1985) of planned behavior; the theory of the “perceived behavioral control”, which together with the “social and moral norms” has had a significant effect on the development of the ecological food product market [37,38,39]. The topic of interest to buy and consume organic food or to manifest an ecological general behavior is considered in the context of the European policies formulated to support the accelerated conversion to the ecological agriculture. Because the agricultural production is responsible for the food security and the protection of the environment, the consumption of organic food, based on the ecological behavior, can increase the opportunities for businesses in the ecological agriculture for the production, processing, commerce, with significant benefits to the whole society [40,41,42]. To connect the aspects of the ecological agriculture with the environmental protection and ecological behavior, it is found that the ecological agriculture certification which is being made in an eco-friendly system is increasingly popular [43,44,45]. The benefits of the organic farms’ certification are similar with the sustainable development goals—horizon 2030: environmental protection, conservation of soil fertility, preservation of biodiversity, respect of natural cycles and animal welfare, transparent labelling for consumers; the European Union organic farming rules cover agricultural products [46,47]. Despite of these benefits and the window of opportunity to promote organic farming for the Central and Eastern European countries, including Romania, there some limits and barriers [48,49,50]. Conclusively, certification in agriculture generates economic opportunities for farmers [51,52].

2.2. Research Design

The main part of the paper is dedicated to an analysis regarding the dynamics of the ecological agriculture in Romania, under the direct influence of the European policies that support the ecological certification and the most rapid extension of the ecological market. The study starts from the main idea that the ecological agriculture is stimulated through the increase of the ecological agricultural product consumption which, in turn, can be achieved through influences and incentives from the European policies and regulations. A principal hypothesis is that the functionality of the motivational-perceptive system is the one that determines slower or more rapid progress results in adopting on an even larger scale the production and consumption of ecological food products. The variables that have allowed the analysis of this evolution are: (i) the number of ecological farms; (ii) the number of certification companies; and (iii) the number of companies that capitalize on ecological products for import-export.

Related to the procedure, we have constituted a database with the companies accredited to certify the systems from the ecological agriculture in Romania for an interval of three years (2019–2021); the data have been supplied by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, grouped and organized with the aim of achieving the descriptive analysis. Then, the data were reframed and reorganized to expose and demonstrate the slow dynamics of certification and, for some certificated companies, the relinquishment of certification during these 3 years. So, it can be deducted that there were some reasons for this decision that affect negatively the progress of the Romanian ecological agriculture and organic food market.

This approach starts from the need of identifying the principal barriers in increasing the market quota of the ecological food products: the lack of consumers’ knowledge and information, the relatively high price, the reduced availability of ecological food products [53,54].

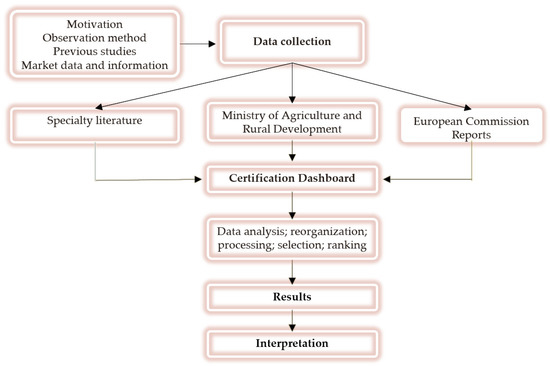

In the following Figure 1 the research design related to the data collection process is shown schematically.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the data acquisition process for the study of ecological certifications.

The paper uses data from the Romanian Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, and from the specific EU reports, which have been processed and analyzed to highlight the evolving tendency of the transition to the ecological agriculture.

2.3. Methods

The analysis has been completed descriptively, illustrating the dynamics and, implicitly, the interest to support the ecological agriculture in Romania. The basic time span for the analysis is 2019–2021, and the data refer to certifying the components of the ecological agriculture in Romania.

The methods used are: the description, the longitudinal data analysis, the graphical and numerical analysis. Overall, the study is a transversal analysis and is mainly supplemented by a qualitative analysis [55].

The main goal is based on cross-sectional data considering a database collected from official sources regarding the certificates issued in Romania as a tool for ecological agriculture. The data were used to illustrate the numbers of certificates for producers, traders, aquaculture, spontaneous flora, exporting and importing domains, within the last three years and for all the companies registered to issue these certificates. We used the analysis data of imports and exports consisting in ecologically certified products, with the aim of capturing the dynamics in comparison with the fields of production and processing and to identify the import–export balance.

This study significantly takes into account the fact that the attainment of the long-term ecological consumption goal depends decisively on the consumers. Most studies have been preoccupied with the behavior of adult population which is the main purchase force at present, but is important to consider the behavior of the young generation, which will very quickly reach the productive age and will become the new production and consumption force [56,57].

3. Results

The main domains for which the ecological certificates are being issued are: producers, processers, traders, aquaculture, spontaneous flora, exporting and importing.

The numbers of certificates for all these domains are illustrated, within the last three years and for all the companies registered to issue these certificates. The presented data show that the numbers of certificates on the mentioned domains are slightly dropping, although there are direct and clear measures supporting the requirement of these certificates in the long-term (Table 1). The slight decrease in number of certificates is numerically visible when analyzing each company (Table 2). Still, when analyzed globally for all companies, data show stable or slightly increased numbers of certificates, except for the last two domains—imports and exports. The explanations consist in: lack of confidence in success given the reluctance or lack of consumers action, the mentality associated with low living standards that maintain the orientation towards non-ecological consumption, lack of confidence in supportive government policies of organic farming, short-term interest in receiving funding, and the lack of positive reactions from the consumer market.

Table 1.

The evolution of ecological certifications by domains in Romanian agriculture (company no., 2019–2021).

Table 2.

Accredited companies for issuing ecological certificates (number of certificates issued, 2019–2021).

As can be seen from Table 1, the dynamics of certifications for companies engaged in the conversion to organic agriculture is very slow, the increase being only 1.84% in 2021 compared to 2020 for producers and 11.11% for traders. For ecologically certified exporters and importers, the dynamics is irrelevant in percentage terms, given the extremely small number of these companies on the Romanian agricultural market (in 2021, only 3 exporters and 13 importers compared to 15 in 2019). This case will be presented later in the analysis of the import–export balance of ecologically certified companies. For processors, aquaculture, and spontaneous flora, the situation is negative, the number of certified companies from one year to another (2020 compared to 2021 and 2019 compared to 2020) decreasing. Overall, as can be seen from the data in Table 1, the situation is unfavorable and does not indicate progress in the ecological certification of Romanian agricultural companies.

As can be seen from Table 2, the evolution of the number of companies certified by the accredited companies is very slow, during the 3-year analysis. Thus, in 2020 compared to 2019, the increase was only 2.60%, in 2021 compared to 2020, a reduced increase of only 1.98%, and in 2021 compared to 2019, a minor increase of 4.64%. We note that most certifiers have issued ecological certifications in the main areas: production, processing and trade. In 2019, only 2 certifiers did not issue certificates for producers and processors; in 2020, only one company issued certificates only for producers, and in 2021, also only one company issued certificates only for producers. It can also be seen from the data in Table 2 that there are fluctuations in maintaining the activity of the certifying companies. Thus, 2 of them are no longer active in 2021, and 1 is present from 2021. An analysis of the dynamics for each of the 14 certifying companies, in terms of the number of certificates issued, shows that in 2021 compared to 2020, 5 of them have recorded negative evolution, and 9 recorded favorable evolution, but at a very low rate.

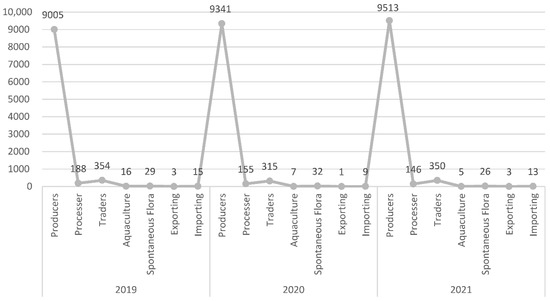

Figure 2 shows the global situation of all certifications of the three years analyzed on the seven accredited certification fields.

Figure 2.

Global variation for the number of certificates for each domain and over 3 years.

As can be seen in Figure 2, the discrepancy between the number of ecologically certified producers, on the one hand, and the number of economic operators from other certifiable fields, on the other hand, is significant.

As shown in Table 1 and Table 2, data and number of certificates should be carefully analyzed, because there are signs related to a slight decrease of the certificates number. No additional difference test was computed due to the small number of companies and observation (i.e., three distinct years). For example, regarding Company 1 (Ecocert LLC) in 2019, 3300 producer certificates were issued and this number rose to 3312 in 2020, and slightly dropped to 3073 in 2021. There seems to be a variation that could indicate different problems or dynamics. In other cases, the numbers are changing into a negative trend altogether. For example, the number of certificates for the processor is 54 in 2019, and this number dropped to 26 in 2020, and even more to 18 in 2021. Although the results have not been tested as significant differences, future studies should monitor the trend and collect data regarding these variations.

Regarding the global variation of the number of certificates, results show a distinct trend (Figure 1):

- -

- Results show a stable number of certificates for the producer certificates, with a small increase over the years, from 9005 in 2019 to 9341 in 2020 and to 9513 in 2021;

- -

- Regarding the processor, the number of certificates is decreasing from 188 in 2019 to 155 in 2020 and to 146 in 2021;

- -

- There is a stable number of certificates regarding the trader’s number of certificates, from 354 in 2019 to 315 in 2020 and 350 in 2021;

- -

- In the aquaculture domain, the number of certificates is decreasing over the years from 16 in 2019 to 7 in 2020 and to 5 in 2021;

- -

- In the spontaneous flora domain, the data show a stable number of certificates, with a slight increase from 29 in 2019 to 32 in 2020 and a slight decrease to 26 in 2021;

- -

- In the exporting and importing domain, there is a small number of certificates, under 10 certificates and the number of certificates is generally decreasing.

Concerning the import–export relationship as mechanism of stimulation and encouragement of ecological agriculture, it can be observed that, at the European level, the activity is dynamic and the imports are consistent, but in Romania, the situation is slightly satisfying given the extremely reduced number of participating actors in the exchange relationship of import–export with products derived from the ecological agriculture, the commercial balance with these products is strongly unbalanced.

At the European level, the generalized situation of the import–export relationship perceived as stimulating factor of boosting ecological agriculture is the following with regard to the origin and destination of organic imports; almost one third of the 2020 organic imports into the EU are by the Netherlands (31%), Germany (18%), Belgium (11%), and France (10%).

Ecological imports into Member States increased to 5% in 2021, compared to 4% in 2019, given the direction of European policies to encourage organic consumption and the acceleration to conversion to organic farming, including with the financial support of related regulations. Main trading partners include Ecuador, Dominican Republic, China, and Ukraine. The ten largest export countries of organic products to the EU represented 64% of the imports in 2020. The main products imported: tropical fruit, nuts, spices, oilcakes, beet and cane sugar, cereals, excluding wheat and rice, oilseeds, excluding soybeans, other products [58].

An import–export balance at the level of Romania for the ecological products in a-accordance with the certification of this sector indicates an imbalance and a very slow and even insignificant dynamics of the ecological food product export (Table 3).

Table 3.

Imports and exports of ecological products of the certified companies in Romania.

The information in Table 3 indicates that the number of exporters is much smaller than that of importers for each of the 3 analyzed years, respectively, and that the number of exporters is small and fluctuating, without considering the reporting to importers. Regarding importers, the situation is not favorable either, given that fluctuations and decreases are recorded for the years of analysis. Regarding the imported and exported products, it is natural to find specific cultural differences, i.e., to import exotic or tropical products, while for export, it is observed that the main types of products are from the category of basic raw materials, without exporting processed products.

The new Common Agricultural Policy which has the role of accelerating the transition to ecological agriculture for many operators on the agricultural market contains a series of reforms for supporting this transition, so that it may bring a more consistent contribution to the European Ecological Pact goals [59].

4. Discussion

The ecological agriculture is strongly supported via the groups of producers, processors, and traders. The balance management of resources of achieving the sustainable development objectives related to the production and consumption is dependent on the agro-environment, agroecological innovations, agroecological knowledge transfer, consultancy, and innovations. In these conditions, their knowledge and funding are the pillars of the ecological agriculture [60].

The preparation for a faster transition to ecological agriculture systems is in the major interest area of the European objectives related to the intensification of measures of adopting the ecological agriculture. Also, the increasing number of organic operations that pass from good practice to best practice, and the increase of the agricultural operations that become more sustainable and integrate organic principles and methods represent a target [60]. The ecological agriculture “is a production system that sustains the health of soils, ecosystems and people”; it relies on ecological processes, biodiversity, and cycles adapted to local conditions, rather than the use of inputs with adverse effects. However, one of the most important aspects is the combination between tradition, innovation, and science to ensure the natural resources and environment protection and a good management of these, and to support the good quality of life for all involved [33,61].

The action Plan of EU regarding the ecological agriculture offers instruments for achieving the target of 25% of agricultural land ecologically cultivated and exploited till 2030 through the program “From Farm to Fork”, the emphasis being placed—in the first stage—on conservation practices [62]. From the perspective of the individual consumption behavior, it can be concluded that this one is influenced by the social and political framework-conditions, and that the companies could have a more decisive role in order to influence the accountability and to create the favorable context of sustainable production and consumption despite the fact that there are some opinions that support the lack of profitability and a low level of success of practicing ecological agriculture [62,63]. The European Commission has elaborated regulations that will favor the extension of production and consumption related ecological practices. The public consultation has exploited the opinions of the co-interested with regard to the progress opportunities of the ecological agriculture in all EU countries [33,60].

One of the most representative directions to follow the ecological agriculture for the attainment of the sustainable development goals in accordance with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals which aim to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure prosperity for everyone by 2030, is emphasized and in complete agreement with the Organic Action Plan. From the three Axes of the Organic Action Plan, Axis 3: “Organics leading by example: improving the contribution of organic farming to sustainability” is the most relevant for the objectives of sustainability and support of ecological agriculture [32]. In this context, it is essential to take measures and specific actions in agreement with the ecological agriculture pillars: supply, to facilitate the capacity development for truly sustainable production, demand, for the campaign to multipliers the organic communications, policy and guarantee, to provide competence for the creation of a favorable policy environment. Starting 2022, the European Commission has reinforced the practice of ecological agriculture. The process is ordinated in specific steps with the involvement of the stakeholders and the market because it is needed to create a pilot network of climate positive organic holdings, to share best practices.

The results obtained are the ones that allowed the outline of these interpretive aspects, based on the collected and processed data. A major difficulty was given by the fact that the information from the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development’s official reports was brief and presented some inconsistencies. Thus, although a county centralizer was identified (from 2020), it does not reflect the dynamics of ecological certifications, while a dynamic for the period 2010–2021 was published, but with different indicators compared to the reports for the period 2019–2021; the data sources present lists with only the names of the companies that are going to be certified for organic agriculture or to convert to them and a grouping with the domains in which the certifiers operate.

5. Conclusions

Given the slowly conversion to ecological agriculture and no-dynamic certification process in the Romanian agriculture, the need to increasingly consider the aspects related to sustainability has been highlighted, in accordance with the orientation tendencies towards the ecological agriculture, due the orientation of food consumption in the approximately last five years towards healthier and more environmentally friendly products. Therefore, the sustainability condition of the ecological agriculture in Romania is ensured through the simultaneous achievement of the three basic goals of the sustainable development: environmentally friendly production, individual and collective benefits of consumers, conservation and protection of natural resources. A major result of this paper has been the emphasis of: the potentially positive impact of the European policies on the conversion to the ecological agriculture of an increasingly higher number of operators in Romania; the link between the ecological products’ market and the pro-ecological behavior; the influence of mentality and favorable perception of the ecological agriculture on the extension of this market; and the attainment of the European Union Organic Action Plan 2030 goals. The processed information and the obtained results indicate the insignificant or even slow progress of the ecological agriculture in Romania, even though the targeting of these production systems began 15 years ago.

The ecological agriculture is based on some strong principles of health, ecology, fairness and care, all together considered. In this framework, it is very important to consider the various forms of certified and non-certified ecologic agriculture. In this context, the certification of the ecological farms proves to be the confidence ambassador for granting the sustainability objectives of durable production and consumption, while the perspective of ecological agriculture certifying systems is attributed to certification organizations as well as to the companies that are being certified. Nevertheless, to allow the system to function in the direction of the ensuring sustainability, it is necessary that the consumption market manifests the ecological food consumption demand so that the producers may be motivated to be certified and the authorized certification organisms may sustain the continuity of this process. The last three years of monitoring the certifications of the operators in the ecological agriculture production system (2019–2021) have revealed a sustained preoccupation regarding the promotion of the ecological agriculture, but without the applicability and practical references, this target will remain a utopia. However, in spite of the interesting investigation carried out, the current situation in Romania is not very satisfying, since there are only 13 certifiers and the oscillations from one year to another are significant for the indication of instability and lack of conviction in the ecological agriculture potential. The consumption market of products deriving from the ecological agriculture is mostly covered by the companies that deal with the import of ecological food products.

The main result of the paper and the practical contribution is that of reorganizing and showing the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development reports data in order to expose the unfavorable situation for this topic. The result of the paper can contribute to the specific literature dedicated to the need to stimulate the institutional, individual and society interest for the ecological agriculture. Because the certification of the Romanian ecologic farms is not a successful process until now, a set of measures to eliminate this lack of interest or to stimulate this process in a favorable manner can be considered; and this is the ministry or government responsibility which can develop stimulative levers. Conclusively, the results of the study that focused on organic certification in Romania, in the context of the launch of the Organic Action Plan for 2021–2030, contribute to filling the gaps in the literature, which is currently limited. The work provides a support of conclusive data that allow detailing the general approaches regarding the progress of ecological agriculture in Romania. The dynamics analysis of the ecological certifications, which points out the evolution of progress in the last 3 years (2019–2021) does not yet exist, so the paper repositions the interest in ecological agriculture from the perspective of mobilization for specific conversion actions to this type of agriculture. The implication of our findings consist in: the built work base that allows for a subsequent causal analysis, based on the conclusions regarding the dynamics and status of ecological certifications over the last 3 years (2019–2021); the analysis was carried out differently for certified companies and for certifiers, the differences in terms of conversion—certification being also highlighted; the barriers identified in the EC studies regarding the conversion to organic agriculture (insufficient funding, high prices of organically certified products, competitiveness with other products, low interest from consumers, lack of knowledge of the eco label) were associated with the progress result of the dynamics of organic certification in Romania; it was highlighted that the objectives of ecological agriculture are of the same category of interest as the objectives of sustainable development SDG 17: sustainable production and consumption; the role of the Organic Action Plan for 2021–2030 for the adoption of ecological production systems was highlighted, mentioning that the stimulation of ecological consumption behavior is a necessity that determines and stimulates the progress of ecological agriculture.

There are some limits of the paper consisting in the lack of exploration of the real causes for which the certification of ecological farms is not favorable, using just a descriptive and numerical analysis instead of quantitative one, and difficulty to create a connection between the European policies supporting the ecological agriculture and the bad situation in Romania for this area. Overall, the paper is predominantly a qualitative analysis, a quantitative analysis not being presented, except in descriptive form and data interpretation; descriptive analysis and data processing can lead to summary interpretation results; limitation to the data provided by the ministry; the difficulty of analyzing the link between ecological agriculture and ecological consumption behavior, which requires a thorough qualitative research, led to the lack of orientation towards this subject; there is a lack of actual research that uses more advanced analysis methods.

As a future work direction, the model of the European barometer to investigate the barriers for the ecological agriculture progress will be considered, with applicability for the Romanian market. We have in mind and will focus on: carrying out a cause–effect type investigation, through which to identify the barriers and causes why the dynamics of the ecological certification process in Romanian agriculture is so slow and fluctuating; emphasizing the important need for certification as a specific measure to effectively switch to organic agriculture and to take measures from the Organic Action Plan for 2021–2030; analysis of the import–export imbalance with ecological products, with an emphasis on identifying the causes; exploring the causes of the unfavorable dynamics identified in this paper, using quantitative methods.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.F.J., M.M., F.-D.L. and C.L.C.; methodology, A.F.J., M.M. and A.-D.R.; software, A.-D.R.; validation, F.-D.L.; formal analysis, F.-D.L.; investigation, A.F.J. and M.M.; resources, M.M., A.-D.R. and F.-D.L.; data curation, A.F.J.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M. and A.-D.R.; writing—review and editing, A.F.J. and A.-D.R.; visualization, A.-D.R., F.-D.L. and C.L.C.; supervision, C.L.C.; project administration, M.M. and C.L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets used in the study: https://www.madr.ro/agricultura-ecologica/operatorii-certificati-in-agricultura-ecologica-2021.html; https://www.madr.ro/agricultura-ecologica/operatorii-certificati-in-agricultura-ecologica-2020.html; https://www.madr.ro/agricultura-ecologica/operatorii-certificati-in-agricultura-ecologica-2019.html, all accessed on 11 August 2022.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tilikidou, Z.; Zotos, Y. Ecological Consumer Behavior: Review and Suggestions for Future Research; MEDIT: Seoul, Korea, 1999; pp. 14–21. Available online: http://www.iamb.it/share/img_new_medit_articoli/656_14tilikidou.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Muresan, I.C.; Harun, R.; Arion, F.H.; Brata, A.M.; Chereches, I.A.; Chiciudean, G.O.; Dumitras, D.E.; Oroian, C.F.; Tirpe, O.P. Consumers’ Attitude towards Sustainable Food Consumption during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Romania. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiciudean, G.O.; Harun, R.; Ilea, M.; Chiciudean, D.I.; Arion, F.H.; Ilies, G.; Muresan, I.C. Organic Food Consumers and Purchase Intention: A Case Study in Romania. Agronomy 2019, 9, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, E.; Hoaghia, M.-A.; Senila, L.; Scurtu, D.A.; Varaticeanu, C.; Roman, C.; Dumitras, D.E. Life Cycle Assessment of Biofuels Production Processes in Viticulture in the Context of Circular Economy. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senila, L.; Tenu, I.; Carlescu, P.; Corduneanu, O.; Dumitrachi, E.; Kovacs, E.; Scurtu, D.; Cadar, O.; Becze, A.; Senila, M.; et al. Sustainable Biomass Pellets Production Using Vineyard Wastes. Agriculture 2020, 10, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocol, C.; Šedík, P.; Brumă, I.; Amuza, A.; Chirsanova, A. Organic Beekeeping Practices in Romania: Status and Perspectives towards a Sustainable Development. Agriculture 2021, 11, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.; Pauli, N.; Biggs, E.; Barbour, L.; Boruff, B. Why bees are critical for achieving sustainable development. Ambio 2020, 50, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pek, C.K.; Foo, F.E. Agricultural Multifunctionality for Sustainable Development in Malaysia: A Contingent Valuation Method Approach. Malays. J. Sustain. Agric. 2022, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polimeni, J.M.; Iorgulescu, R.I.; Mihnea, A. Understanding consumer motivations for buying sustainable agricultural products at Romanian farmers markets. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 184, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, A.K. Consumers’ purchasing decisions regarding environmentally friendly products: An empirical analysis of German consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 31, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrach, A.; Sanz, M.J. Environmental and social consequences of the increase in the demand for ‘superfoods’ world-wide. People Nat. 2020, 2, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoleru, V.; Munteanu, N.; Istrate, A. Perception Towards Organic vs. Conventional Products in Romania. Sustainability. 2019, 11, 2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeanneret, P.; Lüscher, G.; Schneider, M.K.; Pointereau, P.; Arndorfer, M.; Bailey, D.; Balázs, K.; Báldi, A.; Choisis, J.-P.; Dennis, P.; et al. An increase in food production in Europe could dramatically affect farmland biodiversity. Commun. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecological Agricultural Projects. A History of Sustainable Agriculture. Available online: https://www.eap.mcgill.ca/AASA_1.htm (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Arbenz, M.; Gould, D.; Stopes, C. Organic 3.0—For Truly Sustainable Farming and Consumption; IFOAM Organics International: Bonn, Germany, 2016; pp. 1–28. Available online: https://www.ifoam.bio/sites/default/files/2020-05/Oganic3.0_v.2_web.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Muresan, I.C.; Harun, R.; Andreica, I.; Chiciudean, G.O.; Kovacs, E.; Oroian, C.F.; Brata, A.M.; Dumitras, D.E. Household Attitudes and Behavior towards the Food Waste Generation before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Romania. Agronomy 2022, 12, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.; Rahman, K. Understanding the consumer behavior towards organic food: A study of the Bangladesh market. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 17, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nithya, N.; Kiruthika, R.; Dhanaprakhash, S. Shift in the mindset: Increasing preference towards organic food products in Indian context. Org. Agric. 2022, 12, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, A.C.; Ehret, P.J.; Brick, C. Measuring pro-environmental orientation: Testing and building scales. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 81, 101780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroede, H.W. Environmental Values and Their Relationship to Ecological Services. In Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Conference of Environmental Design Research Association, Chicago, IL, USA, 25–28 May 2011; Mittleman, D., Middleton, D.A., Eds.; Make no little plans. The Environmental Design Research Association (EDRA): McLean, VA, USA, 2011; pp. 212–217. [Google Scholar]

- Salleh, M.M.; Ali, S.M.; Harun, E.H.; Jalil, M.A.; Shaharudin, M.R. Consumer’s Perception and Purchase Intentions towards Organic Food Products. Can. Soc. Sci. 2010, 6, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, B.A.; Emmanuel, K.Y. Organic and Conventional Food: A Literature Review of the Economics of Consumer Perceptions and Preferences. Org. Agric. Cent. Can. 2006, 6, 1–59. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/229051543_Organic_and_conventional_food_A_literature_review_of_the_economics_of_consumer_percetions_and_preferences (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Bojnec, S.; Petrescu, D.C.; Petrescu-Mag, R.M.; Rădulescu, C.V. Locally produced organic food: Consumer preferences. Amfiteatru Econ. 2019, 21, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraud, G. Consumer Perception and Marketing of Origin and Organic Labelled Food Products in Europe. Series on Computers and Operations Research Marketing Trends for Organic Food in the 21st Century. 2004, pp. 191–203. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812796622_0012 (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Rădulescu, V.; Cetină, I.; Cruceru, A.F.; Goldbach, D. Consumers’ Attitude and Intention towards Organic Fruits and Vegetables: Empirical Study on Romanian Consumers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, Information Guide for the Beneficiaries of Measure 11—Organic Farming in PNDR 2014–2020, Bucharest, 2021. Available online: https://madr.ro/docs/dezvoltare-rurala/agro-mediu/2021/3.-M.11-Ghid-beneficiari-2021.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- The Transition to Agroecology: Using the PAC Policy to Build New Food Systems, IFOAM EU Group, Friend of The Earth Europe, ARC 2020—Agriculture and Rural Conservation, 2020. Available online: https://www.arc2020.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Agroecologie-ARC2020.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- European Commission. Agriculture and Rural Development Policy. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/policies/agriculture-and-rural-development_en (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- European Commission. Common Agricultural Policy after 2020: Environmental Benefits and Simplification. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/food-farming-fisheries/key_policies/documents/cap-post-2020-environ-benefits-simplification_ro.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- IFOAM Organics Europe. Organic in Europe. Production and Consumption Moving Beyond a Niche. Available online: https://www.organicseurope.bio/about-us/organic-in-europe/ (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- European Union. Working Document of the Staff of the Commission Consultation of Interested Parties—Synthesis Report a-ccompanying the Document Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on an Action Plan for the Development of Organic Production. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/RO/ALL/?uri=CELEX:52021SC0065 (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- European Commission. Organic Action Plan. Action Plan for Organic Production in the EU. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/food-farming-fisheries/farming/organic-farming/organic-action-plan_en (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on an Action Plan for the Development of Organic Production. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/RO/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52021DC0141R(01)&from=EN (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- European Commission. Organic Farming. Policy, Rules, Organic Certifications, Support and Criteria for Organic Farming. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/food-farming-fisheries/farming/organic-farming_en (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Vermesan, H.; Mangau, A.; Tiuc, A.E. Perspectives of Circular Economy in Romanian Space. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, J.; Paul, J. Consumer behavior and purchase intention for organic food: A review and research agenda. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 38, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafir, E.; LeBoeuf, R.A. Rationality. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 2002, 53, 491–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaei-Moghaddam, K.; Vatankhah, N.; Ajili, A. Adoption of pro-environmental behaviors among farmers: Application of Value–Belief–Norm theory. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2020, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Wang, L.; Yang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M. Consumer perceptions and attitudes of organic food products in Eastern China. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleșeriu, C.; Cosma, S.A.; Bocăneț, V. Values and Planned Behaviour of the Romanian Organic Food Consumer. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenhour, C. On Conflicted Swedish Consumers, the Effort to “Stop Shopping” & Neoliberal Environmental Governance. J. Consum. Behav. 2010, 9, 454–469. Available online: http://works.bepress.com/cindy_isenhour/6/ (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Tilman, D. The greening of the green revolution. Nature 1998, 396, 211–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackman, A.; Naranjo, M.A. Does Eco-Certification Have Environmental Benefits? Organic Coffee in Costa Rica; Discussion Paper; Resources for the Future: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 10–58. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/9304506.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Giovannucci, D.; Ponte, S. Standards as a new form of social contract? Sustainability initiatives in the coffee industry. Food Policy 2005, 30, 284–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, R.; Ward, J. Coffee, Conservation and Commerce in the Western Hemisphere: How Individuals and Institutions Can Promote Ecologically Sound Farming and Forest Management in Northern Latin America; Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center: Washington, DC, USA; Natural Resources Defense Council: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Organic Agriculture Europe. EU Organic Regulation (EU) 2018/848. Available online: https://www.ecocert.com/en/certification-detail/organic-farming-europe-eu-n-848-2018 (accessed on 18 June 2022).

- New Regulation on Organic Production by the European Commission, 2020. Available online: https://european-accreditation.org/new-regulation-on-organic-production-by-the-european-commission/ (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Larsson, M.; Morin, L.; Hahn, T.; Sandahl, J. Institutional barriers to organic farming in Central and Eastern European countries of the Baltic Sea region. Agric. Food Econ. 2013, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, M. Environmental Entrepreneurship in Organic Agriculture in Järna, Sweden. J. Sustain. Agric. 2012, 36, 153–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU SEC (2004) 739. European Action Plan for Organic Food and Farming, Commission Staff Working Document. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2004:0415:FIN:EN:PDF (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Grovermann, C.; Quiédeville, S.; Muller, A.; Leiber, F.; Stolze, M.; Moakes, S. Does organic certification make economic sense for dairy farmers in Europe?—A latent class counterfactual analysis. Agric. Econ. 2021, 52, 1001–1012. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/agec.12662 (accessed on 1 July 2022). [CrossRef]

- Agroecological and Other Innovative Approaches for Sustainable Agriculture and Food Systems That Enhance Food Security and Nutrition; High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security (HLPE): Rome, Italy, 2019; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/ca5602en/ca5602en.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Winter, C.; Lockwood, M. A model for measuring natural area values and park preferences. Environ. Conserv. 2005, 32, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Wolfing, S.; Fuhrer, U. Environmental attitude and ecological behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 1999, 19, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Švecová, J.; Pavla, O. The determinants of consumer behavior of students from Brno when purchasing organic food. Rev. Econ. Perspect. 2019, 19, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.F. Consumer attitudes and purchase intentions in relation to organic foods in Taiwan: Moderating effects of food-related personality traits. Food Qual. Prefer. 2007, 18, 1008–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widayat, W.; Praharjo, A.; Putri, V.P.; Andharini, S.N.; Masudin, I. Responsible Consumer Behavior: Driving Factors of Pro-Environmental Behavior toward Post-Consumption Plastic Packaging. Sustainability 2022, 14, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. EU Agricultural Market Briefs No. 18, June 2021. EU Imports of Organic Agri-Food Products Key Developments in 2020, European Union 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/food-farming-fisheries/farming/documents/agri-market-brief-18-organic-imports_en.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- European Commission. The New Common Agricultural Policy: 2023-27. NOUA PAC 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/food-farming-fisheries/key-policies/common-agricultural-policy/new-cap-2023-27_ro (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- IFOAM Organics International. Strategic Plan 2017–2025 of IFOAM Organics International, IFOAM. Available online: https://www.ifoam.bio/strategic-plan-2017-2025 (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Terlau, W.; Hirsch, D. Sustainable Consumption and the Attitude-Behavior-Gap Phenomenon-Causes and Measurements towards a Sustainable Development. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2015, 6, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasile, A.J.; Popescu, C.; Ion, R.A.; Dobre, I. From conventional to organic in Romanian agriculture—Impact assessment of a land use changing paradigm. Land Use Policy 2015, 46, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yara’s Roadmap for Putting Europe’s Farm to Fork Strategy into Action Reducing Nutrient Losses, Increasing Yields and Produ-cing Healthier Crops (June 2021). Available online: https://www.yara.com/siteassets/crop-nutrition/sustainable-agriculture-in-europe/yara-europe-putting-farm-to-fork-into-action.pdf/ (accessed on 19 April 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).