Abstract

This study explores the effect of paternalistic leadership (moral leadership, benevolent leadership, and authoritarian leadership) on hotel employees’ voice behavior and the moderating role of organizational identification. This study samples employees of five-star hotels in northern, central, and southern Taiwan. Purposive sampling is used to distribute 450 questionnaires: 150 in northern Taiwan, 150 in central Taiwan, and 150 in southern Taiwan. The number of valid questionnaires was 359, and the effective questionnaire recovery rate was 79.78%. The analysis results indicate that (1) supervisors’ moral leadership negatively affects hotel employees’ voice behavior, (2) supervisors’ benevolent leadership positively affects hotel employees’ voice behavior, (3) supervisors’ authoritarian leadership negatively affects hotel employees’ voice behavior, (4) organizational identification moderates the relationship between moral leadership and voice behavior, (5) organizational identification moderates the relationship between benevolent leadership and voice behavior, and (6) organizational identification moderates the relationship between authoritarian leadership and voice behavior. This study also proposes managerial implications based on the analysis results. This research attempts to make contributions to the literatures of hospitality and tourism.

1. Introduction

Hiring appropriate talent is the main concern of all organizations and a method of creating a competitive advantage [1]. Hospitality organizations have gradually shifted their focus to encouraging employees to seek opportunities to improve, and numerous practitioners and researchers consider enthusiasm at work a competitive advantage that is essential to organizational success [2,3]. Frontline employees in the hotel industry encounter problems such as long working hours, heavy workloads, lack of training, and customer misbehavior [4,5,6,7]. To adjust to changes in the industry and achieve excellent performance, organizations must constantly improve their products and frontline employees must provide constructive feedback [8]. Therefore, the antecedents of hotel industry employees’ voice behavior must be identified.

Friendly and amicable managers utilize a paternalistic leadership style, which positively affects subordinates [9]. Studies on hospitality have demonstrated the effects of paternalistic leadership on employees’ work engagement and extra-role customer service behavior [10]. In the hospitality industry, paternalistic leadership effectively improves employees’ internal service behavior which, in turn, benefits the organization [11]. However, whether paternalistic leadership affects the voice behavior of hotel employees remains to be determined. Scholars have explored paternalistic leadership in hospitality organizations [9,10,11], but few studies have investigated the effect of paternalistic leadership on hotel employees’ voice behavior.

The effects of paternalistic leadership on the behavior of hotel employees may be affected by situational factors. According to social identity theory, individuals are inclined to identify with groups that satisfy needs for self-esteem, belonging, control, and meaning in life [12,13]. If a hotel can satisfy this need among its employees, its employees may be able to strengthen their sense of identity. Therefore, organizational identification may be a situational variable that affects the relationship between paternalistic leadership and hotel employee voice behavior.

The current research in this area appears to be relatively lacking, this study explores the effect of paternalistic leadership on hotel employees’ voice behavior and the moderating role of organizational identification to fill a gap in the literature on hospitality. The findings can serve as reference for the hotel industry to improve supervisors’ leadership style or the working environment.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Voice Behavior

Van Dyne et al. [14] defined voice behavior as challenging the status quo and offering constructive suggestions. LePine and Van Dyne [15] indicated that voice behavior represents employees’ courage to solve work-related problems by voicing their concerns. Morrison [16] defined voice behavior as the free exchange of ideas, suggestions, concerns, and opinions regarding work-related problems to improve an organization or department thereof. Bashshur and Oc [17] defined voice behavior as the free formation of ideas, opinions, suggestions, or methods of communication within or outside an organization to solve problems and improve an organization, group, or individual.

Studies have indicated that voice behavior benefits workplaces and organizations [18,19,20]. Studies have also indicated that voice behavior has numerous antecedents, including commitment to change [21], encouragement to participate [22], moral leadership, authoritarian leadership [23], person–organization fit [1], psychological capital [24], team-member exchange [25], transformational leadership [26], regulatory foci [18], supervisor empowerment [27], and work engagement [28]. Paternalistic leadership may also be an antecedent of hotel employees’ voice behavior.

2.2. Paternalistic Leadership and Voice Behavior

Farh and Cheng [29] defined paternalistic leadership as a combination of strong discipline, authority, and paternal kindness. Paternalistic leadership consists of three aspects: morality, benevolence, and authority. Moral leadership refers to strong personal virtues, self-discipline, and selflessness. Benevolent leadership is the individualized and holistic care provided to ensure subordinates’ well-being within and outside the work environment. Authoritarianism entails control, authority, and requiring subordinates to be humble and obedient [30]. In an organizational environment, paternalism requires that employees be treated as members of a large family [31]. Paternalistic supervisors exude a fatherly attitude toward their subordinates [32]. Chen [11] investigated employees of Taiwanese hotels for international travelers and discovered that paternalistic leadership improved the quality of internal services. Tuan [10] surveyed employees and supervisors of four- and five-star hotels in Vietnam and discovered that moral leadership and benevolent leadership positively affected employee work engagement and extra-role customer service behavior and that authoritarian leadership negatively affected employees’ work engagement and extra-role customer service behavior. Redmond and Sharafizad [9] investigated Australian hospitality employees and found that paternalistic leadership encouraged discretionary effort among employees.

Social information processing theory dictates that individuals’ attitudes, behaviors, and values are shaped by environmental cues and by information dictating what is valuable and appropriate [33]. From the perspective of social information processing theory [33], hotel employees often perceive supervisors with a moral leadership style as selfless people who lead by example; thus, employees are less likely to voice opinions that differ from those of their supervisors. Accordingly, this study advances the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Supervisors’ moral leadership negatively affects hotel employees’ voice behavior.

According to social information processing theory [33], if supervisors have a benevolent leadership style, then employees may perceive them as kind and understanding; to express gratitude to their supervisors, employees may offer suggestions to improve the workplace. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Supervisors’ benevolent leadership positively affects hotel employees’ voice behavior.

From the viewpoint of social information processing theory [33], if supervisors have an authoritarian leadership style, then employees may fear that voicing differing opinions would be disrespectful. On this basis, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Supervisors’ authoritarian leadership negatively affects hotel employees’ voice behavior.

2.3. Moderating Role of Organizational Identification

Tajfel [34] developed the concept of organizational identification by using social identity theory. Organizational identification refers to employees’ perspective of their membership in an organization. Organizational identification includes individuals expanding their personal self-concept to the organization. Individuals who strongly identify with an organization define themselves by using the characteristics of the organization and act in the organization’s best interests [12,35]. Organizational identification also refers to employees’ degree of attachment to an organization [36]. Hotel employees with a high degree of organizational identification derive a sense of belonging from their hotel and adhere to its policies for the sake of the company. In such a case, supervisors may exhibit a strong moral and authoritarian leadership style that discourages employees from offering suggestions or challenging the status quo to avoid offending their supervisors. Employees often perceive supervisors with a benevolent leadership style as caring and unlikely to exact punishment, which enables employees to offer suggestions without worry. Employees with a low degree of organizational identification are often dissatisfied with the status quo. Supervisors with a strong moral leadership style tend to lead with their hearts. Because subordinates are inspired by their supervisors, employees under such supervisors may offer suggestions for changing the status quo and improving their workplace. In instances of disagreement between employees and their company, employees often perceive supervisors with a benevolent and authoritarian leadership style as only caring about the company, which discourages voice behavior among employees. On this basis, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Organizational identification moderates the relationship between moral leadership and hotel employee voice behavior.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Organizational identification moderates the relationship between benevolent leadership and hotel employees’ voice behavior.

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Organizational identification moderates the relationship between authoritarian leadership and hotel employees’ voice behavior.

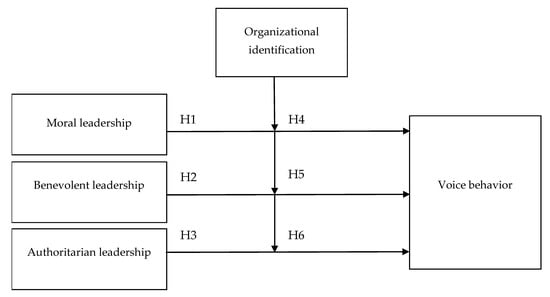

Figure 1 presents the research framework based on the hypotheses.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

3. Methods

3.1. Sampling

This study sampled employees of nine five-star hotels in northern Taiwan (three hotels), central Taiwan (three hotels), and southern Taiwan (three hotels). Purposive sampling was used to distribute questionnaires to hotels on a list of Taiwanese hotels for international travelers released by the Tourism Bureau in 2019. Hair et al. [37] indicated that to develop an effective questionnaire, the number of valid samples should be 5 to 20 times the number of items in the questionnaire. Because the questionnaire has 27 items, the effective sample size is between 135 and 540. The human resources managers of these nine five-star hotels distributed questionnaires to their employees. After the exclusion of invalid questionnaires, the number of distributed questionnaires was 450 (each hotel had 50 questionnaires to distribute).

3.2. Measurement

The items used in this study are three demographic variables: gender, age, and tenure. Paternalistic leadership was measured on the 15-item scale developed by Cheng et al. [38] in terms of moral leadership (five items), benevolent leadership (five items), and authoritarian leadership (five items). A sample item for assessing moral leadership is as follows: “My supervisor is responsible”. A sample item for assessing benevolent leadership is as follows: “My supervisor’s care for me extends to my family”. A sample item for assessing authoritarian leadership is as follows: “My supervisor deliberately keeps distance between us”. Organizational identification is measured using the six-item scale of Mael and Ashforth [39]. A sample item for assessing organizational identification is as follows: “When someone criticizes my company, I feel insulted”. Voice behavior is measured using the six-question scale of Van Dyne and LePine [40]. A sample item for assessing voice behavior is as follows: “I offer suggestions to my supervisor to improve the workplace”.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

This study performed descriptive statistical, correlation, reliability, and confirmatory factor analyses of the valid questionnaire data and regression analysis of the research hypotheses by using SPSS (version 24.0) and AMOS (version 24.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

4. Results

4.1. Respondent Profile

After 8 invalid questionnaires were excluded, 367 questionnaires remained, of which 359 were valid, yielding a 79.78% return rate. Questionnaires that were incomplete or blank, had missing answers or double selection, failed to satisfy the sampling criteria, or exhibited high similarity in scores were deemed invalid. The analysis results indicate that the majority of the participants were women (64.1%) and aged between 19 and 24 years (53.5%). Most of the participants had 1 year or less of work experience in the hotel industry (32.3%).

4.2. Reliability Analysis

A Cronbach’s α coefficient of >0.70 and a revised item–total correlation of >0.45 were used as the measurement standards. The Crobach’s α of moral leadership, benevolent leadership, authoritarian leadership, organizational identification, and voice behavior are 0.92, 0.90, 0.86, 0.92, and 0.90, respectively. These results demonstrate that all dimensions have high reliability.

4.3. Validity Analysis

The confirmatory factor analysis revealed that χ2 = 924.678, degrees of freedom = 314, root mean square error of approximation = 0.07, incremental fit index = 0.91, and comparative fit index = 0.91, all indicating acceptable goodness of fit. Confirmatory factor analysis was performed to determine the validity of the scale (Table 1). A factor loading of less than 0.4 was used as the criterion to exclude items [37]. No items were deleted, and all 27 items are significant (t > 1.96, p < 0.05). The significant factor loadings and high composite reliability indicate that the scale has convergent validity [41]. The average variance extracted (AVE) is 0.70 for moral leadership, 0.65 for benevolent leadership, 0.56 for authoritarian leadership, 0.65 for organizational identification, and 0.60 for voice behavior. Fornell and Larker [42] suggested that AVE must be greater than 0.50. If it is less than 0.50, more than 50% of the variation comes from measurement error, that is, the convergence validity is not sufficient. The AVE of each dimension is greater than 0.5, meeting the significance level and indicating acceptable convergent validity.

Table 1.

Confirmatory factor analysis results.

A low correlation coefficient between two constructs suggests good discriminant validity [42,43]. The square root of the AVE of each dimension must be greater than the correlation coefficient between a given dimension and the other dimensions [37]. The discriminant validity analysis revealed that the square root of the AVE of each dimension ranges from 0.75 to 0.84 (Table 2), which is greater than the correlation coefficient between dimensions. Thus, the scales have favorable discriminant validity.

Table 2.

Mean, standard error, square root of AVE, and correlation coefficients.

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis 1–3 concerns the relationship between supervisors’ paternalistic leadership (moral leadership, benevolent leadership, and authoritarian leadership) and hotel employees’ voice behavior. To verify the hypotheses, this study uses voice behavior as the dependent variable; gender, age, and tenure as control variables; moral leadership, benevolent leadership, and authoritarian leadership as independent variables; and organizational identity as the moderating variable. The interaction terms of paternalistic leadership (moral, benevolent, and authoritarian leadership) and organizational identification are added to the regression formula. The results are listed in Table 3. The results indicate that moral leadership has a significant effect on voice behavior (β = −0.11, p < 0.05). Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is supported. Benevolent leadership has a significant effect on voice behavior (β = 0.21, p < 0.001). Therefore, Hypothesis 2 is supported. Authoritarian leadership has a significant effect on voice behavior (β = −0.11, p < 0.05). Therefore, Hypothesis 3 is supported.

Table 3.

Regression of paternalistic leadership and organizational identification for voice behavior.

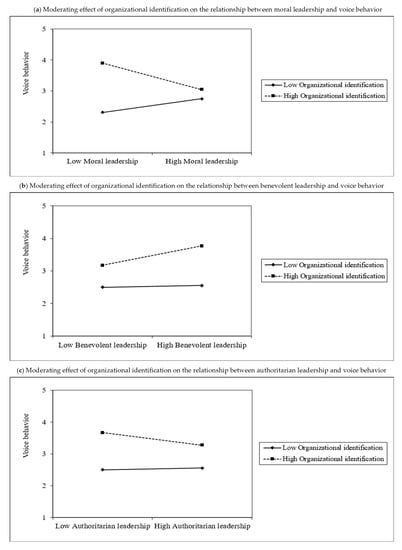

Hypotheses 4–6 concerns whether organizational identification moderate the relationship between supervisors’ paternalistic leadership (moral leadership, benevolent leadership, and authoritarian leadership) and hotel employees’ voice behavior. The analysis results indicate that the interaction of moral leadership and organizational identification has a significant effect on voice behavior (β = −0.20, p < 0.001). Under a high degree of organizational identification, moral leadership negatively affects voice behavior (Figure 2a). Under a low degree of organizational identification, moral leadership positively affects voice behavior. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 is supported. The interaction between benevolent leadership and organizational identification has a significant effect on voice behavior (β = 0.09, p < 0.10). Under a high degree of organizational identification, benevolent leadership positively affects voice behavior (Figure 2b). Under a low degree of organizational identification, benevolent leadership does not strongly affect voice behavior. Therefore, Hypothesis 5 is supported. The interaction between authoritarian leadership and organizational identification has a significant effect on voice behavior (β = −0.09, p < 0.10). Under a high degree of organizational identification, authoritarian leadership negatively affects voice behavior (Figure 2c). Under a low degree of organizational identification, authoritarian leadership does not strongly affect voice behavior. Therefore, Hypothesis 6 is supported.

Figure 2.

Moderating effect of organizational identification on the relationship between paternalistic leadership and voice behavior.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

There are many different potential advanced methods that can be used in behavioral science research, such as multi-objective particle swarm optimization [44], mixed logit model [45], hybrid choice modeling [46], Hayes’ Process macro [47] and structural equation modeling [48]. This study uses multiple regression to test the research hypotheses. All six hypotheses are empirically supported. The analysis results indicate that supervisors’ moral and authoritarian leadership discourages voice behavior among hotel employees and that benevolent leadership encourages voice behavior among hotel employees. This result is consistent with the viewpoint of social information processing theory. Organizational identification moderates the relationship between paternalistic leadership (moral leadership, benevolent leadership, and authoritarian leadership) and voice behavior; this result is consistent with the viewpoint of social identity theory. The analysis results confirm the findings of Dedahanov et al. [23] that supervisors’ authoritarian leadership can decrease employees’ voice behavior. On the other hand, the findings of this study extend the research of Lu and Lu [1], Dai et al. [18], Svendsen and Joensson [21], Ruiz-Palomino et al. [22], Han and Hwang [24], Shih and Wijaya [25], Liang et al. [26], Park et al. [27], and Cumberland et al. [28]. Different from the studies mentioned above that discuss the effects of person–organization fit, regulatory foci, commitment to change, encouragement to participate, psychological capital, team-member exchange, transformational leadership, supervisor empowerment, and work engagement on voice behavior, this study explores the effects of paternalistic leadership (moral leadership, benevolent leadership, and authoritarian leadership) and organizational identification on employees’ voice behavior from the perspective of social information processing theory and social identity theory to fill a gap in the hospitality and tourism literature.

5.2. Implications for Managerial Practice

The results support Hypothesis 1, that is, supervisors’ moral leadership discourages hotel employees from offering suggestions. Hypothesis 2 was also supported, indicating that supervisors’ benevolent leadership encourages voice behavior among hotel employees. Hypothesis 3 was supported and indicates that supervisors’ authoritarian leadership discourages hotel employees from offering suggestions. If hotel managers understand supervisors’ leadership styles, they can instruct supervisors to use a benevolent leadership style and to listen to the opinions of their employees when necessary. To ensure employees follow the rules without voicing their opinions, hotel managers should instruct supervisors to lead by example and to care for their subordinates.

Hypotheses 4–6 were supported, indicating that if employees feel a sense of belonging in their hotels, moral and authoritarian leadership from supervisors can discourage voice behavior among employees, whereas benevolent leadership from supervisors encourages employees to voice their opinions. Employees with a high degree of organizational identification are more willing to express their opinions. Therefore, hotel managers can improve the workplace by considering salary, welfare, and other aspects from the perspective of their employees. This ensures that employees feel pride in their company, follow the company’s rules, and display voice behavior when required.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings of this study and their implications; these limitations may also serve as a starting point for subsequent studies. First, the participants were employees in Taiwan’s hotel industry. Whether the results can be extrapolated to other cultural contexts (such as Europe) should be investigated. Jin et al. [49] indicated that abusive behavior from supervisors can cause deviant behavior in the workplace. Abusive behavior from supervisors may affect the voice behavior of employees; this can be explored in subsequent studies. Dyne et al. [50] subdivided voice behavior into acquiescent voice, defensive voice, and prosocial voice behavior. Subsequent studies can explore the effects of the three dimensions of paternalistic leadership on these three types of voice behavior. Furthermore, previous studies pointed out that shared leadership positively influences proactive behavior, creativity, and innovative behavior [51,52,53]. Future studies can explore the effects of shared leadership on hotel employees’ voice behavior. Finally, prospect theory is regarded as a leading behavioral paradigm to understand decision making under risk and has been widely applied in psychological and behavioral economic studies [54,55]. Future research can use prospect theory to explore the antecedents of hotel employees’ voice behavior.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.-L.Z., C.-H.L. and C.-L.M.; methodology, W.-L.Z.; software, W.-L.Z.; validation, W.-L.Z., C.-H.L. and C.-L.M.; formal analysis, W.-L.Z.; investigation, W.-L.Z.; resources, C.-H.L. and C.-L.M.; data curation, W.-L.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, W.-L.Z., C.-H.L. and C.-L.M.; writing—review and editing, W.-L.Z., C.-H.L. and C.-L.M.; visualization, W.-L.Z.; supervision, W.-L.Z.; project administration, W.-L.Z.; funding acquisition, C.-H.L. and C.-L.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the questionnaire survey for the article is an unnamed, non-interactive and non-intrusive research conducted in public, and will not identify specific individuals from the collected information.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lu, A.C.C.; Lu, L. Drivers of hotel employee’s voice behavior: A moderated mediation model. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 85, 102340. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Lyu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, X.; Li, W. The impact of high-commitment HR practices on hotel employees’ proactive customer service performance. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2017, 58, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loi, R.; Ao, O.K.; Xu, A.J. Perceived organizational support and coworker support as antecedents of foreign workers’ voice and psychological stress. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.D.; Chen, K.Y.; Zhuang, W.L. Moderating effect of work-family conflict on the relationship between leader-member exchange and relative deprivation: Links to behavioral outcomes. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.D.; Hou, Y.H.; Chen, K.Y.; Zhuang, W.L. To help or not to help: Antecedents of hotel employees’ organizational citizenship behavior. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1293–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Beirami, E.; Bouzari, M.; Safavi, H.P. Does work engagement mediate the effects of challenge stressors on job outcomes? Evidence from the hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilic, H.; Okumus, F. Factors influencing productivity in small island hotels: Evidence from Northern Cyprus. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2005, 17, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raub, S. Does bureaucracy kill individual initiative? The impact of structure on organizational citizenship behavior in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmond, J.; Sharafizad, J. Discretionary effort of regional hospitality small business employees: Impact of non-monetary work factors. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 86, 102452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, L.T. Driving employees to serve customers beyond their roles in the Vietnamese hospitality industry: The roles of paternalistic leadership and discretionary HR practices. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.J. Factors influencing internal service quality at international tourist hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 35, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.A.; Terry, D.J. Social identity and self-categorization processes in organizational contexts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyne, L.; Cummings, L.L.; Parks, J.M. Extra-role behaviors: In pursuit of construct and definitional clarity. Res. Organ. Behav. 1995, 17, 215–285. [Google Scholar]

- LePine, J.A.; Van Dyne, L. Predicting voice behavior in work groups. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 853–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, E. Employee voice behavior: Integration and directions for future research. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2011, 5, 373–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashshur, M.R.; Oc, B. When voice matters a multilevel review of the impact of voice in organizations. J. Manag. 2015, 41, 1530–1554. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Y.D.; Zhuang, W.L.; Yang, P.K.; Wang, Y.J.; Huan, T.C. Exploring hotel employees’ regulatory foci and voice behavior: The moderating role of leader-member exchange. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClean, E.J.; Burris, E.R.; Detert, J.R. When does voice to exit? It depends on leadership. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 525–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morrison, E.W.; Wheeler-Smith, S.; Kamdar, D. Speaking up in groups: A cross-level study of group voice climate. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Svendsen, M.; Joensson, T.S. Transformational leadership and change related voice behavior. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2016, 37, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Palomino, P.; Hernández-Perlines, F.; Jiménez-Estévez, P.; Gutiérrez-Broncano, S. CEO servant leadership and firm innovativeness in hotels: A multiple mediation model of encouragement of participation and employees’ voice. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 1647–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedahanov, A.T.; Lee, D.H.; Rhee, J.; Yoon, J. Entrepreneur’s paternalistic leadership style and creativity: The mediating role of employee voice. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54, 2310–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, M.C.; Hwang, P.C. How leader secure-base support facilitates hotel employees’ promotive and prohibitive voices: Moderating role of regulatory foci. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 1666–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, H.A.; Wijaya, N.H.S. Team-member exchange, voice behavior, and creative work involvement. Int. J. Manpow. 2017, 38, 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.L.; Chang, H.F.; Ko, M.H.; Lin, C.W. Transformational leadership and employee voices in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 374–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.J.; Doan, T.; Zhu, D.; Kim, P.B. How do empowered employees engage in voice behaviors? A moderated mediation model based on work-related flow and supervisors’ emotional expression spin. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumberland, D.M.; Shuck, B.; Immekus, J.; Alagaraja, M. An emergent understanding of influences on managers’ voices in SMEs. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2018, 39, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farh, J.L.; Cheng, B.S. A cultural analysis of paternalistic leadership in Chinese organizations. In Management and Organization in the Chinese Context; Li, J.T., Tsui, A.S., Weldon, E., Eds.; Macmillan: London, UK, 2000; pp. 85–127. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, B.S.; Chou, L.F.; Wu, T.Y.; Huang, M.P.; Farh, J.L. Paternalistic leadership and subordinate responses: Establishing a leadership model in Chinese organizations. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 7, 89–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussolino, D.; Calabrò, A. Paternalistic leadership in family firms: Types and implications for intergenerational succession. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2014, 5, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, E.K.; Scandura, T.A. Paternalistic leadership: A review and agenda for future research. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 566–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salancik, G.R.; Pfeffer, J. A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Adm. Sci. Q. 1978, 23, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H. Differentiation between Social Groups: Studies in the Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Academic Press: London, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Harrison, S.H.; Corley, K.G. Identification in organizations: An examination of four fundamental questions. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 325–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teng, C.; Lu, A.; Huang, Z.; Fang, C. Ethical work climate, organizational identification, leader-member-exchange (LMX) and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB): A study of three star hotels in Taiwan. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, B.S.; Chou, L.F.; Huang, M.P.; Farh, J.L.; Peng, S.Q. A triad model of paternalistic leadership: Evidence from business organizations in Mainland China. Indig. Psychol. Res. Chin. Soc. 2003, 20, 209–250. [Google Scholar]

- Mael, F.A.; Ashforth, B.E. Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 1992, 13, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyne, L.; LePine, J.A. Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: Evidence of construct and predictive validity. Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 14, 108–119. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y.J. On the evaluation of structural equation model. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Dai, Q. Portfolio optimization of photovoltaic/battery energy storage/electric vehicle charging stations with sustainability perspective based on cumulative prospect theory and MOPSO. Sustainability 2020, 12, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- González, R.M.; Marrero, Á.S.; Cherchi, E. Testing for inertia effect when a new tram is implemented. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2017, 98, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gao, K.; Yang, Y.; Sun, L.; Ou, X. Revealing psychological inertia in mode shift behavior and its quantitative influences on commuting trips. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2020, 71, 272–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, K.-S.; Han, J.R.; Park, S.R. The influence of hotel employees’ perception of CSR on organizational commitment: The moderating role of job level. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Hall, C.M.; Bonn, M. Factors affecting pandemic biosecurity behaviors of international travelers: Moderating roles of gender, age, and travel frequency. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Kim, K.; DiPietro, R.B. Workplace incivility in restaurants: Who’s the real victim? Employee deviance and customer reciprocity. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 86, 102459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyne, L.V.; Ang, S.; Botero, I.C. Conceptualizing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs. J. Manag. Stud. 2003, 40, 1359–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Ye, B.H.; Xu, X. The cross-level effect of shared leadership on tourism employee proactive behavior and adaptive performance. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.M.; Chen, T.J. Collective psychological capital: Linking shared leadership, organizational commitment, and creativity. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 74, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandavasi, R.K.K.; McConville, D.C.; Uen, J.-F.; Yepuru, P. Knowledge sharing, shared leadership and innovative behaviour: A cross-level analysis. Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 41, 1221–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Hensher, D. Prospect theoretic contributions in understanding traveller behaviour: A review and some comments. Transp. Rev. 2011, 31, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Sun, L.; Yang, Y.; Meng, F.; Ou, X. Cumulative prospect theory coupled with multi-attribute decision making for modeling travel behavior. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2021, 148, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).