Abstract

Social exclusion related to the unemployment of vulnerable population groups constitutes a crucial limitation to achieving a sustainable world. In particular, young and senior populations have specific characteristics that put them at risk of exclusion from the labor market. This circumstance has motivated an attempt to foster cooperation between these age groups to enable them to develop entrepreneurial initiatives that will contribute to close this social vulnerability gap. We approach this topic by focusing on intergenerational entrepreneurship, understood as entrepreneuring projects jointly undertaken by seniors and young adults. The objective of this study was to identify the differences and complementarities between senior and young entrepreneurs with a view to enabling them to develop viable intergenerational entrepreneurial projects, with special emphasis in the motivational push, pull, and blocking factors that affect them. This kind of entrepreneurial initiative fosters knowledge transfer and experience between age groups, promotes job creation and social inclusion, improves a sense of belonging, and, thus, contributes to the construction of a stronger society serving as an engine for sustainable development. Therefore, intergenerational entrepreneurship can be considered a form of social innovation. A mixed-methods approach was utilized in this study, using quantitative data from a questionnaire as a starting point for the characterization and identification of senior and young entrepreneurial profiles, and qualitative data from focus groups, which enabled us to identify complementarities among generations. The results show that there are significant differences between youths and seniors in terms of the motivations and factors that push, pull, or block the decision to form an intergenerational entrepreneurial partnership. These differences can be interpreted as complementarities that can boost intergenerational cooperation to promote social inclusion.

1. Introduction

Social exclusion is becoming a major barrier to the construction of a sustainable future. In particular, the prevalence of unemployment in Europe in recent years is the single most relevant contributor to the persistence of social exclusion [1]. The continent has experienced a rise in social problems and high rates of long-term unemployment, making social exclusion a relevant issue for policymakers [2]. Social exclusion is a broad term and can be understood in differing ways, depending on the context and causes of the exclusion [3]. In this case, we focus on social exclusion related to unemployment, particularly when, in a specific context, a person’s inability to get a job is due to a lack of skills, or cultural and social circumstances related to age and education [1].

Unemployment is a cause of social exclusion or limited self-fulfillment among many social groups, particularly for those lacking competitive skills or work experience [1,3]. In this research, seniors and youngsters (such as unemployed or early retired adults and university graduates facing a lack of job opportunities) were examined because they have specific characteristics that make them vulnerable to exclusion from the labor market. These age groups have the potential to generate social value and sustainable development if intergenerational partnerships are fostered, such that they can work together in viable business projects [4]. Thus, the cooperation between what we call “the young” and “seniors” can represent an opportunity to address the specific vulnerabilities of these age groups, creating employment for disadvantaged segments of the society via entrepreneurship.

The young population is specifically vulnerable to unemployment, which threatens their integration into society [5]. The juvenile unemployment rate has been increasing over the past few years. It stood at 15.5% in 2020, with a wide gender gap (17.34% for women and 14.96% for men) [6]. Moreover, young people are at risk of long-term unemployment because of their low qualifications, passivity in the labor market, precarious financial situation, little social support, and insufficient institutional support [5]. On the other hand, senior adults suffer from age discrimination in the workplace, difficulty adapting to changes in the work environment, and obstacles to getting a job as age increases [7,8] The phenomenon of an aging population require a prolongation of working life and a postponement of retirement [9] that are not easy to attain.

Civil society can play a key role in overcoming the exclusion of these groups via social intervention and fostering social policies to support civil initiatives that reinforce the ties between the individual and society [2]. In this context, this study approaches intergenerational cooperation as a means of combatting social inclusion via entrepreneurship. Intergenerational entrepreneurship is defined as an entrepreneurial initiative in which a joint and continuous commitment of young and senior people is produced in the course of the promotion, investment, start-up, and consolidation of a business project, excluding any form of altruistic and disinterested cooperation in the process.

The objective of this study is to identify the differences and complementarities of senior and young entrepreneurs to approach viable intergenerational entrepreneurial projects in order to promote social cohesion and sustainable development, with special emphasis in the motivational push and pull factors together with the blocking factors affecting the phenomenon. This type of entrepreneurship is a social innovation that promotes job creation by incentivizing inclusion and fostering the transfer of knowledge and experience between age groups. It might represent a solution to unsatisfied social needs. Pinto et al. [10] agree that intergenerational teaching and learning practices can contribute to balancing inequalities and overcoming social segregation, promoting a greater capacity for understanding and respect between generations, which in turn facilitates the development of societies.

Entrepreneurship approached as a social innovation is a suitable method for addressing market failures through the efforts of a variety of actors and the use of their capacities and resources [11,12,13]. Either by necessity or by business vocation, entrepreneurship responds to unsatisfied needs at differing levels of economic development by closing employment or innovation gaps [11]. Entrepreneurship initiatives can help to minimize economic and social challenges, thereby transforming communities and improving their quality of life by connecting resources and growth across differing cultures, economic, and political contexts [14].

The concept and scope of entrepreneurship has evolved over time, changing from its traditional role as an instrument to gather and organize factors of all kinds into a viable business project aimed at delivering products and services to satisfy market needs, to playing an active role in addressing social, environmental, cultural and economic challenges with financially viable initiatives, and in which social innovation and collaboration are distinctive characteristics [15].

The new role entrepreneurship is playing now is fundamental to addressing sustainable development [11,12,13]. The economic fabric faces an enormous challenge with respect to economic, social, and environmental sustainability. That is why sustainable entrepreneurship has emerged as “the process of discovering, evaluating, and exploiting economic opportunities that are present in market failures which detract from sustainability” [16,17]. The purpose of sustainable entrepreneurship, then, is understood as taking advantage of opportunities to create value that encourages economic, environmental, and social prosperity, merging the economic dimension of entrepreneurship with social and ecological development [18]. This type of entrepreneurship has both a profit-making purpose and a social and environmental one, incorporating sustainability from the beginning of the project and integrating the three pillars (economic, social, and environmental) in the business [19].

Sustainable intergenerational entrepreneurship takes place as a means of advancing solidarity and integrating society for everyone, enabling an increasing number of senior people to play an active role in developing sustainable models of production and prosperity [20]. The viability of intergenerational entrepreneurship is based on the complementarity of the skills and needs of the two age groups, which provide business projects with a heightened guarantee of success. However, there is no significant evidence in the academic literature of the viability of intergenerational programs in business creation.

This paper contributes to the literature on motivations for entrepreneurship by offering an inclusive, sustainable, and social perspective on the topic. It sheds light on the differences and complementarities in motivations and blocking factors of entrepreneurial activity among differing age groups so that they can approach viable entrepreneurial projects. It thus incentivizes social cohesion and sustainable development through these initiatives.

The contributions of this paper are relevant to public policy agents, scholars, and society in general. The knowledge produced can have an impact on entrepreneurial public policies or civil society initiatives to integrate differing age groups in entrepreneurial projects, thus being a lever for social transformation.

The data used in this paper came from a European study on the potential of intergenerational entrepreneurship among young and senior entrepreneurs, in which three universities that are working with the young population and three NGOs that are working with the elderly population in Spain, Sweden, and France are participating. A mixed-methods approach was utilized, using quantitative data from a questionnaire as a starting point for the characterization and identification of senior and young entrepreneurship profiles, and qualitative information from focus groups, which enabled us to identify complementarities between generations. The focus groups also enabled us to detect differences between the characteristics of youths and seniors, which could be translated into possible complementarities to achieve successful intergenerational relations.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: First, a literature review is presented, analyzing attitudes and intentions regarding entrepreneurship in light of various theories together with the available literature on intergenerational entrepreneurship. The second section comprises a description of the methods utilized in this study. Finally, the results are presented, followed by a discussion section and concluding remarks.

2. Literature Review

In recent decades, the importance of entrepreneurs and SMEs has been recognized as a source of economic dynamism and innovation [21,22,23,24,25,26]. In fact, the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) report for 2018/19 highlights the impact of entrepreneurial dynamism on economic growth [27]. Several studies have helped to verify the existence of a direct relationship between the level of entrepreneurial activity and the level of the development of economic growth over time. In this sense, entrepreneurial policies are considered to be one of the most important instruments for economic growth. They are understood to be the fundamental pillars of job creation, economic growth, global competitiveness, and social development [11,12,13]. Evidence of this is the institutional push that the European Union is giving to entrepreneurial activity in the Green Paper titled The Entrepreneurship spirit in Europe [28].

Entrepreneurship has been the object of study by academics and researchers from many disciplines, with significant contributions ranging from psychology and sociology to organizational design and strategy formulation.

As a starting point for this study, the intentions for engaging in entrepreneurship were deeply researched. The attitudes of individuals towards entrepreneurship are determined by their beliefs, meaning that their decisions depend on the perceived advantages and disadvantages of a potential entrepreneurial endeavor [29]. Paturel [30] and Veciana [31] stand out as being among the most important authors to have contributed to this topic. According to these authors, human beings are a product of the environment in which they develop. Consequently, the attitudes, motivations, decisions, and all those aspects that condition human behavior when creating a company are conditioned by their environment.

Motivation can be considered to be “a set of forces that drive, direct and maintain a certain behavior” [32]. Authors such as Maslow [33], Vroom [34], Herzberg [35], and Porter and Lawler [36] studied the motivations of people and defined it as the drive of an individual carry out any activity. It is also worth highlighting the contribution of Ajzen [37], who defines three determinants of motivation: the attitude toward the behavior; the social pressure to carry it out or not; and the perceived ease or difficulty regarding the expression of a certain behavior.

When referring specifically to entrepreneurship, there are differing perspectives on motivation. Paturel [30] proposes that the process of creating a company is the result of three factors: the aspirations or motivations of the creator, the skills and resources of the founder, and the environment or surroundings (opportunities and incentives). Moreover, Gatewood, Shaver, Powes, and Gaartner [38], and Manolova, Brush, and Edelman [39], found that the effort or intensity of entrepreneurship depends on how committed the entrepreneur was to his project, on the expectations he had about it, and on his confidence in his capacity and ability to execute the project.

Other authors, such as Barba-Sánchez and Atienza-Sahuquillo [40], add a differentiation between personal characteristics, abilities, and motivations to become an entrepreneur [41]. Quevedo, Izar, and Romo [42], Gnyawali [43], and Shapero [44] also contributed to the theory by differentiating exogenous factors related to the environment in general, the specific sector in which the business will operate, and even the entrepreneur’s own environment or personal sphere, which affect the will and capacity of the entrepreneur to undertake a project.

Marulanda, Montoya, and Velez [45] propose a model consisting of five categories, including motivational factors: personal; scientific knowledge; resource availability; incubator organization; and social environment. They agree that the process of business creation is determined largely by the internal and external perception of the individual, which depends on the support and the perception of the activity at a social level.

These contributions demonstrate the complexity of entrepreneurial motivation. It is also worth noting GEM approach considering two types of “classical” differentiated motivations [46] to become an entrepreneur: by necessity, induced by circumstances related to survival or the lack of work alternatives; and by opportunity, when it is a consequence of a series of favorable circumstances that represent an option for personal improvement with limited risks.

Following Coduras [47], the concepts of entrepreneurship by opportunity and necessity are related to pull and push factors [48,49,50]. According to Amit and Muller [48] and Kirkwood [51], push factors are characterized by often negative personal or external circumstances. Entrepreneurs motivated by push factors are those whose dissatisfaction with their positions pushes them to start a new venture. Pull factors, by contrast, are those that attract people to venture into a new business, such as identifying an opportunity. “Pull entrepreneurs” are those who initiate venture activity because of the attractiveness of the business idea and its personal implications. Sarri and Trihopoulou [52] identify several motivations related to push and pull factors. Factors related to the former include unemployment, dismissal, the need for professional growth, dissatisfaction with previous employment, and family pressures, among others. Pull factors are the desire for independence, achievement, to make a profit, or social prestige. The entrepreneurial intentions work as a trigger for self-employment decisions for individuals with humane-oriented personal values when engaging in opportunity-based entrepreneurship [53].

Kirkwood [51] and, much earlier, Cromie [54], applied a comparative gender approach to exploring differences between various business motivations. Kirkwood [51] differentiates pull factors from push factors as benchmarks for entrepreneurship. Among the pull factors, he mentions independence, money, challenges or achievement, opportunity, and lifestyle. The main push factors were dissatisfaction at work, changes in the work situation, and having children and other personal responsibilities.

Choo and Wong [55] make an important further contribution by highlighting both the main motivations and the main barriers, adding the blocking factors to the equation. They suggest that the motivations to start a business are the potential intrinsic rewards, autonomy, and independence. On the other hand, the barriers to starting a business are mainly a lack of capital, skills, operating costs, and confidence. Therefore, it can be concluded that the barriers are not only extrinsic, but also intrinsic factors.

From the above, it is evident that the social and cultural context has an influence on the development of individuals, their training, values, and capacities, as well as so-called internal factors that condition the entrepreneurial process. This distinction often explains the differing perspectives regarding entrepreneurship when comparing countries, and even regions within the same country.

One can conclude from this general research of the academic literature that an individual’s motivation to become an entrepreneur is often complex and multifaceted. Thus, motivational factors (attitudes, values, and psychological characteristics) can be categorized from a variety of perspectives, giving rise to an infinite mix of circumstances. It is primarily the intrinsic conditions, which are conditioned by the perception of extrinsic factors, that can “push” or “block” the entrepreneurial process. These were the foundations on which our research was developed.

Despite the fact that numerous studies have been conducted on motivations in the entrepreneurial process, the motivational differences between age groups have not been explored. Nevertheless, some progress has been made in terms of researching entrepreneurship in the various age groups individually.

As a result of the increasing interest in the entrepreneurial phenomenon, an extensive number of studies have been conducted on specific groups: young people [56], seniors [57], women [51], and groups at risk of exclusion through social innovation initiatives [58], as well as on social entrepreneurship projects [59] and by geographical area, as can be seen in the GEM national reports.

There are numerous studies in the literature on senior entrepreneurship [60] as a means to solve the social and economic problems of an aging population, because those people would stay in the labor force and might even generate economic growth [61,62]. There are authors who address differing aspects of this phenomenon related to seniors’ profiles and driving motivations [63,64], while the European Union has prepared the report document Senior Entrepreneurship Good Practices Manual [65], in which, although only senior entrepreneurship is addressed, it has an implicit intergenerational perspective because it identifies the various roles of seniors in the entrepreneurial process (entrepreneur, supporting businesses, or mentoring) in a series of cases analyzed. This study has been complemented by other projects in this area, such as the Senior Entrepreneurs: Best Practices Exchange [66] and the 50+ Entrepreneurship Platform [67]. It is also worth mentioning projects with a focus on the transfer of unidirectional knowledge from one age group to another, both from old to young, as is the case in mentoring, or the cooperation of senior entrepreneurs with universities to improve professional skills and the motivation of students to undertake entrepreneurship [68], as well as in the opposite direction, from young to old, helping them to acquire technological skills and competencies [69].

In the field of business administration, most of the scientific literature refers to gener-ational changes in family businesses [70,71].

Beyond those aforementioned initiatives of a public nature and the spontaneous initiatives of civil society, academic research works on intergenerational entrepreneurship are rather scarce. Thus, Isele and Rogoff [4], based on GEM data, conclude that young population groups are more prone to take up entrepreneuring than older age groups, who undertake by opportunity, and, due to the characteristics of entrepreneurs, tend to be more successful.

The lack of formal studies on intergenerational entrepreneurial activity is not an obstacle to recognizing the potential benefits of the participation of people of different age groups, or their ability to face the challenges and problems associated with starting a business project. It is also evident that individuals of differing age groups differ not only in terms of knowledge, skills, abilities, and experiences, but also in their value systems, attitudes, and vision of reality, due to their ways of learning and communicating [72]. These differences influence their behavior and expectations in areas as diverse as family, social relationships, as citizens, work, and as entrepreneurs [73,74]. Defining the boundaries between generations is therefore extremely valuable in this area.

However, there is no common criterion to establish the age ranges of each generation, although there is unanimity that a generation [75] is made up of a set of individuals who, having been born in the same interval of time, have been exposed to similar social and cultural experiences that differ from those of other societies [74]. Therefore, in studies carried out in countries with differing economic, social, and cultural development, we can find differences in the age ranges of the generations [76], making it extremely difficult to conclusively define the boundaries between young, adult, and senior people. The definition of age ranges and the status of young or senior is a matter of debate conditioned by socioeconomic, demographic, and geographical factors, among others, and there seems to be no unanimity in the scientific community about this. A UN study about age classifications emphasizes the differing dimensions and approaches to the question among UN country members [77]. Moreover, in different population censuses, citizens are categorized in the age range of 25–65 years as “adults”, followed by an “elderly” or “senior” group above 65 years of age [78]. Eurostat splits the adult category into two (25–49 and 50–64 years) [79], and the OECD distinguishes three groups according to working age (15–24, 25–54, and 55–64 years) [80]. However, these approaches differ from the GEM classification (18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, and 55–65 years) which happens to be appropriate and accepted in relation to the entrepreneuring phenomenon [81]. However, the research team was constrained by the population scope (university students and early retired or unemployed adults) of the EU project sponsoring it and was pushed to define a realistic age range of 20–30 years of age for what is labeled “young people”, and more than 50 years for what is called “senior” for the purposes of this research.

Nevertheless, it is evident that intergenerational entrepreneurship as a social innovation promotes job creation through social inclusion and fosters the transfer of knowledge and experience between generations. Intergenerational teaching and learning practices can contribute to balancing inequalities and to overcoming social segregation and promote a greater capacity for understanding and respect between generations, which fosters the development of societies [10].

According to Backman and Karlsson [82], seniors can help the young to focus and prioritize, while young people, for example, can guide seniors in terms of valuable sources of information and helping them to adopt and adapt to new technological systems and digital platforms. Intergenerational programs are oriented to the exchange of knowledge and experiences between people of differing ages. It is about fostering a two-way enrichment process, whereby both age groups can learn together and from each other. According to Starks [83] these programs facilitated the retention of the tacit knowledge of both generations. It also promotes an active maturity and is a source of health and well-being. As life expectancy increases and older people claim an active role in society, there is a greater awareness of the role they can play in shaping the society of the future. Starks [83] also highlights teamwork as a successful activity for organizations and business projects. Another aspect of interaction between intergenerational groups is that it can also help to alleviate the current decline in the pension system. In sum, it facilitates a bidirectional transfer of values and knowledge between the two groups [84], as well as being an opportunity to create links and networks that promote a solidary and inclusive society.

In light of these considerations, we argue that differences in terms of motivations, and pushing and blocking factors for entrepreneurship between the two age groups (young and senior) represent the complementarities required to develop successful intergenerational business projects. Moreover, we posit that there are collaborative attitudes between the two groups that make it possible to tackle business projects jointly.

3. Materials and Methods

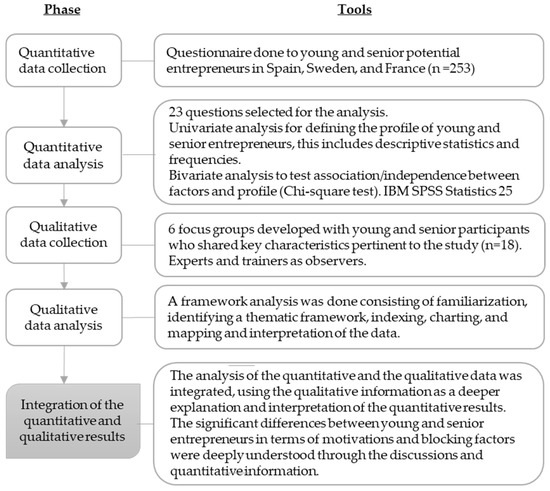

According to several authors who have analyzed entrepreneurship research publications [85,86,87,88,89,90] entrepreneurship research is dominated by quantitative methods [91]. They argue that qualitative methods are increasingly less preferred for publication than quantitative methodologies. However, the application of qualitative approaches might facilitate a deeper understanding of the topic in this field of study [91,92] and enrich the conclusions provided by quantitative methods [93,94]. A mixed methodology was adopted for our study to achieve the objective of identifying the differences and complementarities between young and senior entrepreneurs. Mixed-methods research combines qualitative and quantitative data collection and data analysis within a single study [95]. The two methods reinforce each other to provide the most informative, complete, balanced, consistent, conclusive, and useful framework [96].

This combination can also neutralize the limitations of one method and reinforce the advantages of the other, thus generating superior results [97,98]. Besides, it is suitable for exploring and explaining the entrepreneurial process and its complexity [95,99,100]. Therefore, the researcher normally merges two datasets to finally bring the results together in the interpretation and analysis [101].

Considering the two dimensions of mixed methods proposed by Molina-Azorín et al. [95]—implementation and priority—we chose a sequential mixed method, prioritizing the qualitative methodology. This approach enabled the qualitative part to clarify, interpret, and enrich the quantitative results of the fieldwork by identifying the differences and complementarities of the motivations and blocking factors between seniors and young entrepreneurs engaging in intergenerational entrepreneuring projects.

The procedure comprised a three-step sequence. First, quantitative data was gathered through a survey of two population groups (young people and seniors) in three European countries (Spain, Sweden, and France) with a view to determining similarities and differences between them in terms of motivations and blocking factors with respect to become entrepreneurs. Second, this information served as a starting point to subsequently develop a series of focus groups to delve deeper into the similarities and differences between the two groups in relation to developing intergenerational entrepreneurship projects. Finally, the information gathered utilizing the two methodologies was analyzed jointly. This research took place in the context of a European project, Erasmus+, which involved three universities and three NGOs that specialized in the senior populations. This project, approved in 2018, was a strategic partnership KA203 and had the objective of promoting intergenerational entrepreneurship among potential young and senior entrepreneurs by serving as a platform for the exchange of good practices and accompanying them in the entrepreneurial process.

Based on the visual model of a sequential mixed methodology developed by Ivankova et al. [102], Figure 1 is a summary of the model used, with an explanation of the order and procedure of each phase.

Figure 1.

Research methodology.

3.1. Quantitative Sample and Methodology

The target population was young and senior populations involved or interested in entrepreneuring. The research team was constrained by the population scope of the EU project sponsoring it: university students and adults with previous work experience but currently unemployed or retired, and thus beneficiaries of specialized NGOs providing services aimed at social and professional integration. This constraint resulted in a realistic age range definition of 20–30 years of age for the category “young” people, and over 50 years for the “seniors” category. The participants were selected on the basis of their expressed interest in becoming entrepreneurs, which made it possible to find individuals who might have had the intention of starting a new business, but for some reason had not done so yet. The target population for this research and the sampling method was by quotas. The sample size was determined on the basis of the following parameters: a confidence level of 95%; a desired sampling error of 5%; and the hypothesis of maximum indeterminacy regarding the proportion of individuals who would start an intergenerational entrepreneurship project (p = q = 50 percent). The population data found in the World Development Indicators [103] was used, according to which the number of people between 20 and 30 years old, and 50 or more years old in Spain, Sweden, and France totaled 44,961,031 people.

The sample size, n, was calculated as follows:

The calculation above provided a sample size of 384 persons.

Since the period for data collection was limited, only 253 responses were obtained, which resulted in the sampling error being:

This result means that a reasonable margin of error [104,105,106,107] is borne in mind for the results presented below.

The questionnaire used was framed in the European project described previously. It is important to clarify that this project had a broader goal than the objective of this research. For this reason, the questionnaire was designed to collect more extensive data than that required for this study. Its contents and tools had been created to enable matching the two groups as a basis for the development of an entrepreneurial project that incorporated practices related to knowledge transfer and intergenerational learning during the life cycle of the entrepreneurial activity.

There were two versions of the questionnaire, one adapted to young people (36 questions) and the other to seniors (43 questions) to suit each population’s characteristics. In sum, the questionnaire included a set of profile questions, variables on the motivations and blocking factors for entrepreneurship, and a section of questions on entrepreneurial activity for individuals who had already started their business projects. These variables included income, time spent working in the business, economic activity, and suchlike. As the focus of this research was on potential entrepreneurs and their motivations or blocking factors in relation to starting a new business, the variables related to knowledge transfer and intergenerational learning in the life-cycle stages were not considered. Consequently, only 23 items from the questionnaire were analyzed. These were, firstly, questions referring to profile (10 in total): age, population group, gender, city, country, education, who one lives with, couple’s occupation, first experience as an entrepreneur, and when to start. Secondly, responses to 13 questions about motivational push and pull factors, and values that could be considered either motivational or blocking factors were analyzed.

Specifically, of the variables for motivational or blocking factors were utilized, following the contributions of various authors: thoughts about being an entrepreneur, intention of creating a company, the reason to start an entrepreneurial project [41,45,47,51,54,108] interest in entrepreneurship [45], cultural or family values, perception of the creation of a company [41,45,51,108], the importance of various factors for being an entrepreneur [55,109], the needs of the project [41,45,54,55,109], problems when starting a business due to age [55], support from relatives [45,47,54,108,109], relatives’ experience in entrepreneurship [45,47,54,108], and financial situation [45,55,109].

Additionally, it was necessary to identify the differing positions of the two groups. A univariate analysis was performed on the collected data to determine the profiles of each group, consisting of descriptive statistics and frequencies. Subsequently, a bivariate analysis was conducted to test whether there were significant correlations between the motivating factors and those that block the entrepreneurial process, and the attributes of the respondents’ profiles, focusing on the type of population: young people or seniors. This enabled us to identify the most relevant motivating or blocking factors in the entrepreneuring process for each group. For this analysis, the chi-square test for association/independence was used. This enabled us to determine whether two categorical variables were independent of each other [110,111,112,113].

Thus, for the first set of variables, that is, those referring to the motivations of the entrepreneurial process, the first null hypothesis was:

Hypothesis 1.

Each categorical variable referring to motivations is independent of the population groups (youth and seniors).

Additionally, for the last set of category variables referring to the blocking factors of the entrepreneurial process, the second null hypothesis was:

Hypothesis 2.

Each categorical variable referring to blocking factors is independent of the population group (youth and seniors).

Once the motivations and blocking factors that were common to the two groups and the differences had been analyzed, the gaps and complementarities were identified, thus providing input for the qualitative analysis.

3.2. Qualitative Sample and Methodology

It was necessary to carry out a deeper analysis of which needs, ideas, difficulties, etc., the two groups faced, and to have the flexibility to delve into these issues. Focus groups were chosen for this purpose with the intention of gaining a deeper understanding of the young and senior entrepreneurs during the debate to determine the reasons for these gaps and complementarities in terms of their needs and assets for entrepreneurship.

Thus, focus groups were conducted in the three countries. Experts, young, and senior entrepreneurs were summoned using the communication and network resources of the participating organizations. In sum, 18 participants gathered to discuss intergenerational entrepreneurship in six discussion groups. Experts and trainers were present as listeners and observers to contribute to the general conclusions.

Focus groups can serve as primary sources of data and are appropriate for the generation of new ideas formed within a social context [114]. They play three main roles in social sciences research: (1) they are a self-contained method in studies for which they serve as the principal sources of data; (2) they can be used as a supplementary data source; and (3) they are also used in multi-method studies, in which two or more means of gathering data are used [115]. According to Kitzinger [116], group interaction is explicitly used when utilizing the focus group method. In addition, they represent a dynamic form of interaction that capitalizes on communication among the research participants to generate rich information.

In our case, the focus groups were used to provide a qualitative framework for the results obtained from the univariate and bivariate analyses. Gathering information, thoughts, and opinions from junior and senior participants enabled us to delve into the dimensions of the human being that are intrinsically qualitative, to understand the needs of intergenerational groups and the reasons for the differences and complementarities of the two social groups. Following Powell and Single [117], our procedure comprised four steps. The first stage involved the creation of six focus groups that included young and senior individuals who could share key characteristics pertinent to the study. The second stage consisted of creating a protocol for the group discussions and a set of items to be discussed as a guideline.

This was done using a “framework analysis” to define the specific topics to be addressed, as described by Ritchie and Spencer [118], since this methodology best suits research with specific questions, a pre-designed sample (seniors and young entrepreneurs), and a limited timeframe [119]. Moreover, a panel of experts—trainers and mentors in entrepreneurship and intergenerational projects—acted as facilitators throughout a series of meetings with the project’s partners. During these meetings, the discussion items for the focus groups were chosen, doubled-checked by peers, and validated (see Table 1 below).

Table 1.

Discussion topics.

The third stage involved conducting group discussions, which were led by a moderator. The participants gathered to address the agenda at a location in which the participants felt comfortable enough to engage in a dynamic discussion for about two hours [120]. The task of the moderator was not to conduct interviews, but to facilitate a comprehensive exchange of viewpoints. All the participants were free to contribute openly and respond to the ideas of others [121]. In this study, each focus group took a maximum of two hours, including greetings, instructions, discussion, and conclusions. In total, six focus groups were held: two in Spain, one in France, and three in Sweden, with the participation of 18 young and senior entrepreneurs, of which nine were men and nine women, in each of them.

The fourth stage consisted of the analysis of the information gathered by the panel of expert, in which complementarities and gaps between the two groups are identified.

For an optimal analysis of the information, the discussions were recorded, documented, and transcribed. Then, the data obtained was processed to detect the main themes and to identify common thoughts and differences between the groups.

The reliability of the results lies in the logic applied to organizing the data. The most frequently agreed or disagreed upon themes were identified as the main ones. Differences and points of agreement between seniors and young people were identified by the intensity and frequency of the comments. The information was analyzed in relation to the study objective, while carefully avoiding bias [118].

The results of this analysis are presented in the next section.

4. Results

In this section, the results of the study are presented. First, the results of the quantitative analysis are described, then those of the qualitative analysis and, finally, the integration of both to offer a full, in-depth interpretation.

The quantitative analysis begins with a description of the sample defined using the univariate analysis and then the analysis deepens by indicating the results of the bivariate methodology.

The univariate analysis enabled us to describe the sample of 253 people who answered the questionnaire:

- 53% of the respondents were young and 47% seniors.

- 40.3% responded in Spain, 37.5% in France, and 22.1% in Sweden.

- 52.6% were female, 47% male, and 0.4% had other gender identities.

- Their educational level was 3.2% PhD, 51.8% Master, 39.5% Bachelor or Graduate, 4.0% Vocational Education, and 1.2% indicated that they did not hold any of the above qualifications.

Appendix A Table A1 shows the results of the bivariate analysis for all the variables considered as motivating and blocking factors for the two groups. The last column indicates whether there were significant differences between them. That is, whether being in the young or senior population group affected the motivating or blocking factor variable (the null hypothesis is rejected) or not (the null hypothesis is accepted).

This information made it possible to identify the motivations and the blocking factors that are common to both groups and those that are different or more relevant to each of them. These results were triangulated later with the results from the qualitative methodology, thus integrating both methodologies and obtaining a deeper understanding of the differences and complementarities between the two age groups.

The qualitative analysis was carried out using information from the focus groups to obtain more precise knowledge of the factors that affected both groups, so that gaps and complementarities between them could be detected to promote intergenerational entrepreneurial projects. The discussions had involved seven topics: (i) the personal situations of the young and senior entrepreneurs; (ii) professional network; (iii) the perception of intergenerational entrepreneurship; (iv) perception of complementarities between the two groups; (v) perception of their roles as young or senior members of an entrepreneurial team; (vi) the soft and hard skills required; and (vii) common and specific skills needed by the group.

In terms of the first theme, the personal situations of the young and senior entrepreneurs, the seniors expressed that they had more pressing circumstances, such as debts, taxes, and legal situations than young entrepreneurs. However, they were also predisposed to supporting with their experience, finances, time, and ‘other’ in entrepreneurial projects. In the second category, professional network, the seniors had a broader network than the young people, but the youngsters knew how to navigate social media and how to network. An interesting finding was that the young entrepreneurs did not perceive contacts as being critical for a successful business. In terms of the third category, perceptions of intergenerational entrepreneurship, the seniors often perceived it positively as a top-down approach, while the young people rarely referred to seniors when talking about projects. On the other hand, the seniors spoke to or approached young people for assistance with the skills and knowledge they lacked. By contrast, the young people indicated that they would avoid the seniors because they feared that the older people would adopt paternal attitudes. The fourth category was the perception of complementarities between the two groups. The findings indicate that, in the eyes of senior entrepreneurs, young people have more technical knowledge, and their presence is evidence of dynamism for the future of a project. Meanwhile, in the eyes of young entrepreneurs, seniors have the know-how and networks. Fifthly, their perceptions of their roles as young and senior entrepreneurs did not differ. The leading role in the project should depend on the project’s purpose and on the respective hard and soft skills of the participants, be they youngsters or veterans. The sixth category was about which hard and soft skills each group had. The seniors had existing hard skills that were well-proven and honed by practice. In relation to soft skills, the seniors tended to allow themselves more time to succeed and were usually better at anticipating difficulties. Conversely, the young people had more “technical” training in relation to entrepreneurship and the projects concerned, but they lacked experience. Finally, the last category was the specific skills by group (senior or young). The seniors indicated that they needed more ICT and digital media training, depending on the project, as well as knowledge of social media and emotional management for working with the youth. The young people felt they needed an entrepreneurial training package, as well as emotional management for working with seniors, particularly listening and understanding.

From the information obtained after discussing the seven topics, both groups considered the seven factors presented in Table 2 to be the top concerns for intergenerational entrepreneurial teams.

Table 2.

Top concerns for intergenerational teams.

The quantitative results regarding the significant differences, and common motivations and blocking factors for young and senior entrepreneurs were analyzed together with the top concerns and findings from the focus groups. From the above, two summary tables are presented (Table 3 and Table 4), which contain the factors that were common to the two groups and the significant differences between them, with an indication of the most relevant motivations for each of them.

Table 3.

Motivations by group.

Table 4.

Blocking factors by group.

As explained in Table 3, for both groups involved in intergenerational entrepreneurship, the main motivations they had in common were that they had an interesting business idea or needed to earn more money; their friends made them interested in entrepreneurship; and family and cultural values motivated them to be entrepreneurs. However, there were some differences in motivations between the two groups. The young people included among their main motivations for starting a business having the dream of doing so. Moreover, their interest in entrepreneurship came from their schools, families, and/or the media. On the other hand, the seniors stated that there might be other reasons for becoming entrepreneurs, over and above having an interesting business idea.

Both groups considered having passion, ideas, skills, social and professional contacts, support, financing, and the trust of others to be important factors when becoming an entrepreneur; they believed that their families and partners or friends would motivate them to start a business; and they had relatives who had managed businesses. Young people also had other motivational factors: they found it interesting to create a company; they believed that their families, partners, and/or friends would give them advice, facilitate social or professional contacts, give them financial support, and help them in small daily matters; moreover, their parents had managed companies. The seniors also considered social and professional contacts to be extremely relevant factors and, in their case, friends and spouses or partners had managed businesses.

In relation to the blocking factors (see Table 4), both groups thought that the process of creating a company was complicated. Regarding the project, they believed that they had certain needs in terms of social contacts, their professions, support from others, skills, the trust of others, passion, or ideas. They believed that they might experience some problems due to their age when creating a company, whether it be some type of discrimination by suppliers, customers, public administrations, or insurers, a lack of the necessary skills or little support from others. However, the young people indicated that a lack of financing was the most relevant blocking factor. They thought that there were other problems they might experience due to their age, such as the ability to obtain the necessary funding when starting the business, a lack of social and professional contacts, or little trust from others. The seniors, meanwhile, added that there were other types of problems due to their age, such as loneliness, change of mindset, life management, discrimination, and a lack of recognition, among others. They believed that their families, partners, or friends would probably not support them, and that the financial situation of their families or partners would influence their decision to become entrepreneurs or partners in a company.

In summary, there are both a common ground and valuable complementarities that intergenerational teams can utilize to establish successful entrepreneurial projects. This is so despite some reluctancies and cultural barriers, which can be addressed with a successful matching process.

5. Discussion

In this paper, we focused on identifying the differences and complementarities between the motivations and blocking factors of seniors and young entrepreneurs for potential intergenerational entrepreneurship projects. According to Isele and Rogoff [4], understanding the factors affecting business creation and integrating young and senior populations can dynamize the culture of entrepreneurship by providing intergenerational teams with added value. Among these factors, some can be identified as complementarities that can be potentiated to build a viable project based on intergenerational cooperation, whereas others represent barriers to such an endeavor.

Motivational factors for one collective can represent blocking factors for another, which indicate complementing possibilities for an intergenerational match. In terms of motivations, the findings disclose that both groups had in common a series of motivations for starting a business; either they had an interesting business idea, or they needed to earn more money. Moreover, their close networks, such as family and friends, motivated them to be entrepreneurs. Motivations can be determined by various attitudes and perceptions, as Ajzen [37] mentioned, resulting in differences in motivations.

Young people and seniors complement each other in terms of financial situation, life circumstances, and network, among others. This can be understood as complementarities of the exogenous factors or environment conditions of the two age groups [42,43,44]. For seniors, personal conditions regarding debts, tax pressures, and responsibilities tend to be more pressing and complex, representing a blocking factor for entrepreneurship, while for the young, this does not represent a blocking factor, because they have fewer responsibilities. This result is in line with Marulanda, Montoya, and Velez’s [45] argument that the differences in the perception and availability of resources is determinantal to the process of business creation.

Regarding social and professional contacts, youngsters and seniors have a strong complementarity. While this can be a blocking factor for young people, for seniors it is a motivational factor for entrepreneurship. Some young people do not have a broad network, but they do know how to navigate the Internet and social media. By contrast, seniors have the personal contacts and the network. Another important complementarity relates to the passion of young people and emotional support. Young people and seniors complement each other when starting a business because young entrepreneurs dream of creating a “unicorn” and selling it, regardless of the viability in the long run, while seniors start a business to be sustainable in the long run. Emotional support plays an important role for youth. They lack patience and tend to underestimate others’ points of view. They also often fail to analyze and sell, and have difficulty defining viable business models. All of these are blocking factors. However, they have a lower cost of failure, and training will enable them to succeed eventually. On the other hand, seniors have a predisposition to support other entrepreneurial projects with experience, money, and time rather than starting their own businesses. Family support and experience in the field of entrepreneurship is also a pulling motivational factor for both generations. Thus, according to Amit and Muller [48] and Kirkwood [51], push factors are characterized by often negative personal or external factors. Meanwhile, pull factors, such as identifying an opportunity, are those that attract people to venture into a new business.

In terms of the two groups cooperating in an entrepreneurship venture, seniors consider intergenerational entrepreneurship a positive top-down approach. By contrast, young people rarely refer to seniors when talking about their projects. However, they acknowledge that seniors have the skills and knowledge that they lack. In terms of the limitations to intergenerational entrepreneurial activity, the two groups agree on the difficulty of starting a business. Moreover, both groups thought they could have problems due to their ages and suffer certain discrimination.

6. Conclusions

This research shows the potential of matching the skills of different population groups—young and senior—to support the promotion of social cohesion and, therefore, reinforce sustainable development in society. As Paturel [30] and Veciana [31] explain, environment is a determinant of an individual’s development, and their values, capacities, and external factors determine entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurial profiles are as diverse as the differing contexts and cultures around the globe. In fact, the promotion of these types of entrepreneurial initiatives can improve the perception of belonging to specific population groups, leading to a stronger, interconnected society that adds value to the community, as a vehicle for a more sustainable future. Considering that the results of this paper are specific of the project context, extending this study to other areas and groups at risk of social exclusion, with other populations with different profiles and qualifications, could be considered.

Finally, our study demonstrated that the two profiles under study have highly proven complementarities to jointly generate social value when working in intergenerational teams, eliminating some of the vulnerabilities that these groups might experience in society, either when starting a business or simply continuing with it. In this respect, these results represent an opportunity to address the specific vulnerabilities of these age groups, especially in disadvantaged segments of society, by creating employment via entrepreneurship. In fact, our findings can help university graduates and unemployed or early retired adults who face a lack of job opportunities to negotiate viable synergies of intergenerational entrepreneurship.

All in all, there is a common understanding of the potential complementarity between young people and seniors that should enable them to start a successful entrepreneurial project, but there is a need to improve various areas so that the cooperation can function well. The top concerns for intergenerational teams identified in our research could be a good starting point for those working with the entrepreneurial population and those with entrepreneurial intentions. It should assist them to first identify profile characteristics, motivations, and needs, and secondly, to promote the establishment of intergenerational projects with young and senior populations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P.-E., B.S. and Y.B.; methodology, Y.B., A.P.-E. and C.N.-M.; formal analysis, Y.B. and C.N.-M.; investigation, B.S., A.P.-E. and Y.B.; data curation, Y.B. and C.N.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P.-E.; writing—review and editing, B.S., Y.B., A.P.-E. and C.N.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by IVI project (2018-1-FR01-KA204-047946). Erasmus+ Key Action 204, funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

Data Availability Statement

Private dataset is available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors the partners of the IVI project and, in special, Isidro de Pablo for the valuable support in all the process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Results of the bivariate analysis for variables related to motivational and blocking factors.

Table A1.

Results of the bivariate analysis for variables related to motivational and blocking factors.

| Variable | Result | χ2 | p Value | Categorical Variables Independent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have you ever thought about being an entrepreneur? | 78.8 percent of the young respondents had thought of becoming entrepreneurs, while 72 percent of the seniors had thought about it. | 6.098 | 0.047 | H1 rejected | |

| Do you intend to create your own company? | 68.7 percent of the young respondents had the intention of creating a company, while 57.4 percent of the seniors had that intention. | 8.11 | 0.017 | H1 rejected | |

| What was the most important reason for which you started your project, or why you would start an entrepreneurial project? | Idea | 43.5 percent of the young respondents thought having an idea was an important reason to become an entrepreneur, versus 32.5 percent of the seniors. | 3.183 | 0.074 | H1 accepted |

| Money | 6.1 percent of the young respondents thought that money was an important reason for becoming an entrepreneur, versus 8.5 percent of the seniors. | 0.547 | 0.46 | H1 accepted | |

| Dream | 35.1 percent of the young respondents thought having a dream was an important reason to become an entrepreneur, versus 17.9 percent of the seniors. | 9.236 | 0.002 | H1 rejected | |

| Not interested | 6.9 percent of the young respondents were not interested in becoming entrepreneurs, versus 12 percent of the seniors. | 1.907 | 0.167 | H1 accepted | |

| Other | 8.4 percent of the young respondents considered other reasons important for becoming entrepreneurs, versus 29.1 percent of the seniors. | 17.766 | 0 | H1 rejected | |

| How did you get interested in entrepreneurship? | Friends | 29 percent of the young participants became interested in entrepreneurship because of friends, versus 19.8 percent of the seniors. | 2.788 | 0.095 | H1 accepted |

| Family | 35.9 percent of the young participants became interested in entrepreneurship because of family, versus 24.1 percent of the seniors. | 4.01 | 0.045 | H1 rejected | |

| School | 44.3 percent of the young participants became interested in entrepreneurship because of school, versus 20.7 percent of the seniors. | 15.431 | 0 | H1 rejected | |

| Media | 30.5 percent of the young participants became interested in entrepreneurship because of media, versus 10.3 percent of the seniors. | 15.088 | 0 | H1 rejected | |

| Not interested | 6.1 percent of the young respondents were not interested in becoming an entrepreneur, versus 12.9 percent of the seniors. | 3.393 | 0.065 | H1 accepted | |

| Other | 16.8 percent of the young participants became interested in entrepreneurship for other reasons, versus 44 percent of the seniors. | 21.817 | 0 | H1 rejected | |

| Are there any cultural and/or family values which affect your decisions regarding entrepreneurship? | Yes, cultural values encourage me to be an entrepreneur | Cultural values encouraged 33.3 percent of the young respondents to be entrepreneurs, while 25.7 percent of the seniors were encouraged by cultural values. | 1.585 | 0.208 | H1 accepted |

| Yes, family values encourage me to be an entrepreneur | Family values encouraged 38.7 percent of the young respondents to be entrepreneurs, while 27.4 percent of the seniors were encouraged by family values. | 3.235 | 0.072 | H1 accepted | |

| Yes, cultural values discourage me from being an entrepreneur | Cultural values discouraged 8.1 percent of the young respondents from being entrepreneurs, while 3.5 percent of the seniors were discouraged by cultural values. | 2.138 | 0.144 | H1 accepted | |

| Yes, family values discourage me from being an entrepreneur | Family values discouraged 5.4 percent of young respondents from being entrepreneurs, while 9.7 percent of the seniors were discouraged by family values. | 1.496 | 0.221 | H1 accepted | |

| No | 38.7 percent of the young respondents considered that no cultural and/or family values affected their decisions regarding entrepreneurship, versus 41.6 percent of the seniors. | 0.19 | 0.663 | H1 accepted | |

| How would you describe the creation of a company? | Interesting | 70.9 percent of the young respondents described the creation of a company as interesting, versus 53 percent of the seniors. | 8.548 | 0.003 | H2 rejected |

| Burdensome | 44.8 percent of the young respondents described the creation of a company as burdensome, versus 35 percent of the seniors. | 2.461 | 0.117 | H2 accepted | |

| Easy | Three percent of the young respondents described the creation of a company as easy, versus 6.8 percent of the seniors. | 2.036 | 0.154 | H2 accepted | |

| Other | Nine percent of the young respondents described the creation of a company with other qualities, versus 12.8 percent of the seniors. | 0.972 | 0.324 | H2 accepted | |

| How important are these factors for being an entrepreneur? | Funding | 85.6 percent of the young respondents considered funding as an important factor for being an entrepreneur, versus 79 percent of the seniors. | 1.894 | 0.169 | H2 accepted |

| Social and professional contacts | 90.1 percent of the young respondents considered social and professional contacts as an important factor for being an entrepreneur, versus 100 percent of the seniors. | 12.355 | 0 | H2 rejected | |

| Ideas | 93.2 percent of the young respondents considered having an idea as an important factor for being an entrepreneur, versus 96.6 percent of the seniors. | 1.486 | 0.223 | H2 accepted | |

| Support | 89.5 percent of young respondents considered having support as an important factor for being an entrepreneur, versus 94.9 percent of the seniors. | 2.464 | 0.116 | H2 accepted | |

| Passion | 95.5 percent of the young respondents considered having passion as an important factor for being an entrepreneur, versus 98.3 percent of the seniors. | 1.607 | 0.205 | H2 accepted | |

| Skills | 93.2 percent of the young respondents considered having skills as an important factor for being an entrepreneur, versus 98.3 percent of the seniors. | 3.888 | 0.049 | H2 rejected | |

| Other persons trusting you | 84.2 percent of the young respondents considered being trusted by others as an important factor for being an entrepreneur, versus 97.4 percent of the seniors. | 12.545 | 0 | H2 rejected | |

| In relation to the needs of your project, do you agree or disagree that you are lacking the following aspects? | Funding | 80.8 percent of the young respondents agreed that they lacked funding for their projects, versus 64.6 percent of seniors. | 4.602 | 0.032 | H2 rejected |

| Social and professional contacts | 75.3 percent of the young respondents agreed that they lacked social and professional contacts for their projects, versus 62.7 percent of the seniors. | 2.731 | 0.098 | H2 accepted | |

| Ideas | 59 percent of the young respondents agreed that they lacked ideas for their projects, versus 71.4 percent of the seniors. | 0.419 | 0.518 | H2 accepted | |

| Support | 74.4 percent of the young respondents agreed that they lacked support for their projects, versus 57.1 percent of the seniors. | 0.983 | 0.321 | H2 accepted | |

| Passion | 61.4 percent of the young respondents agreed that they lacked passion for their projects, versus 60 percent of the seniors. | 0.004 | 0.95 | H2 accepted | |

| Skills | 69.1 percent of the young respondents agreed that they lacked skills for their projects, versus 66.7 percent of the seniors. | 0.015 | 0.902 | H2 accepted | |

| Other persons trusting you | 65.2 percent of the young respondents agreed that they lacked the trust from others for their projects, versus 60 percent of the seniors. | 0.057 | 0.812 | H2 accepted | |

| Do you have or think that you would experience a problem when starting a business due to age? | 48 percent of the young respondents thought they would experience a problem when starting a business due to their age, versus 71.3 percent of the seniors. | 13.522 | 0 | H2 rejected | |

| What kind of problems do you think you might experience when starting a business due to your age? | Harder to get funding | 72.1 percent of the young respondents thought they might find it harder to source funding due to their age, versus 29.4 percent of the seniors. | 25.628 | 0 | H2 rejected |

| Lacking social and professional contacts | 49 percent of the young respondents thought they might lack social and professional contacts due to their age, versus 27.5 percent of the seniors. | 6.549 | 0.01 | H2 rejected | |

| Little support from others | 11.5 percent of the young respondents thought they might have little support from others due to their age, versus 15.7 percent of the seniors. | 0.524 | 0.469 | H2 accepted | |

| Lack of the necessary skills | 26 percent of the young respondents thought they might lack the necessary skills due to their age, versus 15.7 percent of the seniors. | 2.067 | 0.151 | H2 accepted | |

| Little trust from others | 22.1 percent of the young respondents thought they might experience less trust from others due to their age, versus 3.9 percent of the seniors. | 8.373 | 0.004 | H2 rejected | |

| Discrimination | 32.7 percent of the young respondents thought they might experience discrimination due to their age, versus 25.5 percent of the seniors. | 0.84 | 0.359 | H2 accepted | |

| Other | 2.9 percent of the young respondents thought they might experience other problems due to their age, versus 21.6 percent of the seniors. | 14.539 | 0 | H2 rejected | |

| What would be or has been the reaction of your family, partner, or friends when you start/ed your business? | They will/did not support me | 6.1 percent of the young respondents answered that their families, partners, or friends would/did not support them, versus 14.2 percent of the seniors. | 4.519 | 0.034 | H2 rejected |

| Financial support | 45.5 percent of the young respondents answered that their families, partners, or friends would/did give them financial support, versus 21.2 percent of the seniors. | 15.845 | 0 | H2 rejected | |

| Knowledge/advise | 72 percent of the young respondents answered that their families, partners, or friends would/did support them with knowledge or advice, versus 18.6 percent of the seniors. | 69.602 | 0 | H2 rejected | |

| Practical matters | 45.5 percent of the young respondents answered that their families, partners, or friends would/did support them in practical matters, versus 23 percent of the seniors. | 13.46 | 0 | H2 rejected | |

| Social and professional contacts | 58.3 percent of the young respondents answered that their families, partners, or friends would/did support them with social and professional contacts, versus 32.7 percent of the seniors. | 16.02 | 0 | H2 rejected | |

| Encouragement | 74.2 percent of the young respondents answered that their families, partners, or friends would/did encourage them, versus 70.8 percent of the seniors. | 0.364 | 0.546 | H2 accepted | |

| Other | 1.5 percent of the young respondents answered that their families, partners, or friends would have/had another reaction, versus 1.8 percent of the seniors. | 0.025 | 0.875 | H2 accepted | |

| Has any person in your immediate circle been managing a business? | Mother and/or father | 38.2 percent of the young respondents’ mothers or fathers had been managing a business, versus 15.4 percent of the seniors. | 16.12 | 0 | H2 rejected |

| Siblings | 7.6 percent of the young respondents’ siblings had been managing a business, versus 15.4 percent of the seniors. | 3.7 | 0.054 | H2 accepted | |

| Other relatives | 31.3 percent of the young respondents’ other relatives had been managing a business, versus 28.2 percent of seniors. | 0.282 | 0.595 | H2 accepted | |

| Spouse or partner | 2.3 percent of the young respondents’ spouses or partners had been managing a business, versus 13.7 percent of seniors. | 11.324 | 0.001 | H2 rejected | |

| Friends | 30.5 percent of the young respondents’ friends had been managing a business, versus 45.3 percent of the seniors. | 5.748 | 0.017 | H2 rejected | |

| No | No relative of 20.6 percent of young respondents had been managing a business, versus 15.4 percent of the seniors. | 1.136 | 0.286 | H2 accepted | |

| Do you think your family’s/partner’s financial situation might influence your decisions to become an entrepreneur or a partner? | 33.3 percent of young respondents felt that their families’/partners’ financial situation would influence their decision to become an entrepreneur, versus 57.1 percent of the seniors. | 14.03 | 0.003 | H2 rejected | |

References

- Sen, A. Social Exclusion: Concept, Application, and Scrutiny; Asian Development Bank: Manila, Philippines, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla, A.; Lapeyre, F. Social Exclusion: Towards an Analytical and Operational Framework. Dev. Chang. 1997, 28, 413–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peace, R. Social Exclusion: A Concept in Need of Definition? Soc. Policy J. N. Z. 2001, 16, 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Isele, E.; Rogoff, E.G. Senior Entrepreneurship: The New Normal. Public Policy Aging Rep. 2014, 24, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kieselbach, T. Long-Term Unemployment Among Young People: The Risk of Social Exclusion. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2003, 32, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unemployment, Youth Total (% of Total Labor Force Ages 15–24) (Modeled ILO Estimate)|Data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.1524.ZS (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Yeatts, D.E.; Folts, W.E.; Knapp, J.D. Older Workers’ Adaptation to a Changing Workplace: Employment Issues for the 21st Century. Educ. Gerontol. 2000, 26, 565–582. [Google Scholar]

- Malinen, S.; Johnston, L. Workplace Ageism: Discovering Hidden Bias. Exp. Aging Res. 2013, 39, 445–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solem, P. Ageism and Age Discrimination in Working Life. Nord. Psychol. 2015, 68, 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, T.A.; Marreel, I.; Hatton-Yeo, A. Guia de Ideas para la Planificación y Aplicación de Proyectos Intergeneracionales (Guide of Ideas for Planning and Implementing Intergenerational Projects). 2009; ISBN 978-989-8283-01-6. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED507360.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Laborde, M.N.; Veiga, L. Emprendimiento y desarrollo económico. Rev. Antig. Alumnos IEEM 2010, 13, 84–85. [Google Scholar]

- Arzeni, S.; Pellegrin, J.P. Entrepreneurship and Local Development. OECD Obs. 1997, 204, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Naudé, W. Entrepreneurship and Economic Development: Theory, Evidence and Policy. Evid. Policy IZA Discuss. Pap. 2013, 7507. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2314802 (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Ribeiro-Soriano, D. Small Business and Entrepreneurship: Their Role in Economic and Social Development. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2017, 29, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donati, P.P. La Crisis del Estado Social y la Emergencia del Tercer Sector: Hacia una Nueva Configuración Relacional. Rev. Minist. Trab. Asun. Soc. 1997, 5, 15–36. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, T.; McMullen, J. Toward a Theory of Sustainable Entrepreneurship: Reducing Environmental Degradation through Entrepreneurial Action. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 50–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.; Winn, M. Market Imperfections, Opportunity and Sustainable Entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, M.; Joshi, B.P. Entrepreneurship and Sustainable Development. J. Entrep. Manag. 2017, 6, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Moreno, D. Emprendimiento Sostenible, Significado y Dimensiones. Katharsis 2016, 21, 449–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- United Nations. Report of the Second World Assembly on Ageing; United Nations: Madrid, Spain, 2002; Available online: http://undocs.org/A/CONF.197/9 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Schumpeter, J.A. Teoría del Desenvolvimiento Económico: Una Investigación Sobre Ganancias, Capital, Crédito, Interés y Ciclo Económico, 3rd ed.; Fondo de Cultura Económica: Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Thurik, R. Linking Entrepreneurship to Growth. OECD STI Work. Pap. 2001, 2001/2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B. The Entrepreneurial Society; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Audretsch, D.B. SMEs in the Age of Globalization; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2003; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Carree, M.A.; Thurik, R. The Impact of Entrepreneurship on Economic Growth. In Handbook of Entrepreneurship Research; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 437–471. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, F.J. Convergencia, Desarrollo y Empresarialidad en el Proceso de Globalizacioόn Econoόmica. Rev. Econ. Mund. 2004, 10–11, 171–202. [Google Scholar]

- Red Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM). Informe Gem España 2018–2019. Available online: https://www.gem-spain.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/GEM2018-2019.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- European Commission. Green Paper on Entrepreneurship in Europe, 2003, COM (2003) 27 Final. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/content/green-paper-entrepreneurship-europe-0_en (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Rueda, M.I.; Fernández, A.; Herrero, Á. Aplicación de la Teoría de la acción Razonada al ámbito Emprendedor en un Contexto Universitario. Repos. Abierto Univ. Cantab. Investig. Reg. 2013, 26, 141–158. [Google Scholar]

- Paturel, R. Pratique du Management Stratégique; Presses Universitaires de Grenoble: Grenoble, Isère, France, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Veciana, J. Creación de Empresas como Programa de Investigación Científica. Rev. Eur. Dir. Econ. Empresa 1999, 8, 11–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hitt, M.; Stewart, B.J.; Porter, L. Administración; Pearson Education: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A.H. Motivation and Personality; Harper & Row Publishers, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Vroom, V.H. Work and Motivation; John Wiley & Sons. Inc: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Herzberg, F. Work and the Nature of Man; World Press: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, L.W.; Lawler, E.E. What Job Attitudes Tell About Motivation; Harvard Business Review Reprint Service: Boston, MA, USA, 1968; pp. 118–126. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatewood, E.J.; Shaver, K.G.; Powers, J.B.; Gartner, W.B. Entrepreneurial Expectancy, Task Effort, and Performance. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2002, 27, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolova, T.S.; Brush, C.G.; Edelman, L.F. What Do Women Entrepreneurs Want? Strateg. Chang. 2008, 17, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba-Sanchez, V.; Atienza-Sahuquillo, C. Entrepreneurial Behavior: Impact of Motivation Factors on Decision to Create a New Venture. Investig. Eur. Dir. Econ. Empresa 2011, 18, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domenichelli, R. Factores Condicionantes de la Actividad Emprendedora. Rev. Treb. Econ. Soc. 2012, 64, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Quevedo, L.M.; Izar, J.M.; Romo, L. Factores Endógenos y Exógenos de Mujeres y Hombres Emprendedores de España, Estados Unidos y México. Investig. Cienc. 2010, 18, 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Gnyawali, D.R.; Fogel, D.S. Environments for Entrepreneurship Development: Key Dimensions and Research Implications. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1994, 18, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapero, A.T. The Entrepreneurial Event; College of Administrative Science, Ohio State University: Columbus, OH, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Marulanda, F.Á.; Montoya, I.A.; Vélez, J.M. Teorías Motivacionales en el estudio del emprendimiento. Rev. Científica Pensam. Gestión 2014, 36, 204–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, U.; Hart, M.; Mickiewicz, T.; Drews, C.C. Understanding Motivations for Entrepreneurship. BIS Res. Pap. Dep. Bus. Innov. Ski. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coduras, A. La Motivación para emprender en España. Ekon. Rev. Vasca Econ. 2006, 62, 12–39. [Google Scholar]

- Amit, R.; Muller, E. “Push” and “Pull” Entrepreneurship. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 1995, 12, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, A. The Push and Pull of a Vision. Motiv. Strateg. Entrep. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, S. Be a Push Not a Pull Entrepreneur. Am. Manag. Assoc. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood, J. Motivational Factors in a Push-Pull Theory of Entrepreneurship. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2009, 24, 346–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarri, K.; Trihopoulou, A. Female Entrepreneurs’ Personal Characteristics and Motivation: A Review of the Greek Situation. Women Manag. Rev. 2005, 20, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.; Neumeyer, X.; Liñán, F. Understanding How and When Personal Values Foster Entrepreneurial Behavior: A Humane Perspective. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2021, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cromie, S. Motivations of Aspiring Male and Female Entrepreneurs. J. Organ. Behav. 1987, 8, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, S.; Wong, M. Entrepreneurial Intention: Triggers and Barriers to New Venture Creations in Singapore. Singap. Manag. Rev. 2006, 28, 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero, M.; Amorós, J.E.; Urbano, D. Do Employees’ Generational Cohorts Influence Corporate Venturing? A Multilevel Analysis. Small Bus. Econ. 2019, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]