Collective or Individual? What Types of Tourism Reduce Economic Inequality in Peripheral Regions?

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Ambiguous Impact of Tourism on Economic Growth and Inequality

1.2. The Potential Role of Individual Accommodation Tourism in Reducing Economic Inequality

1.3. Warmia-Masuria Province as an Example of a Peripheral Region with Tourism Potential

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Empirical Model

2.2. Data Preparation

3. Results

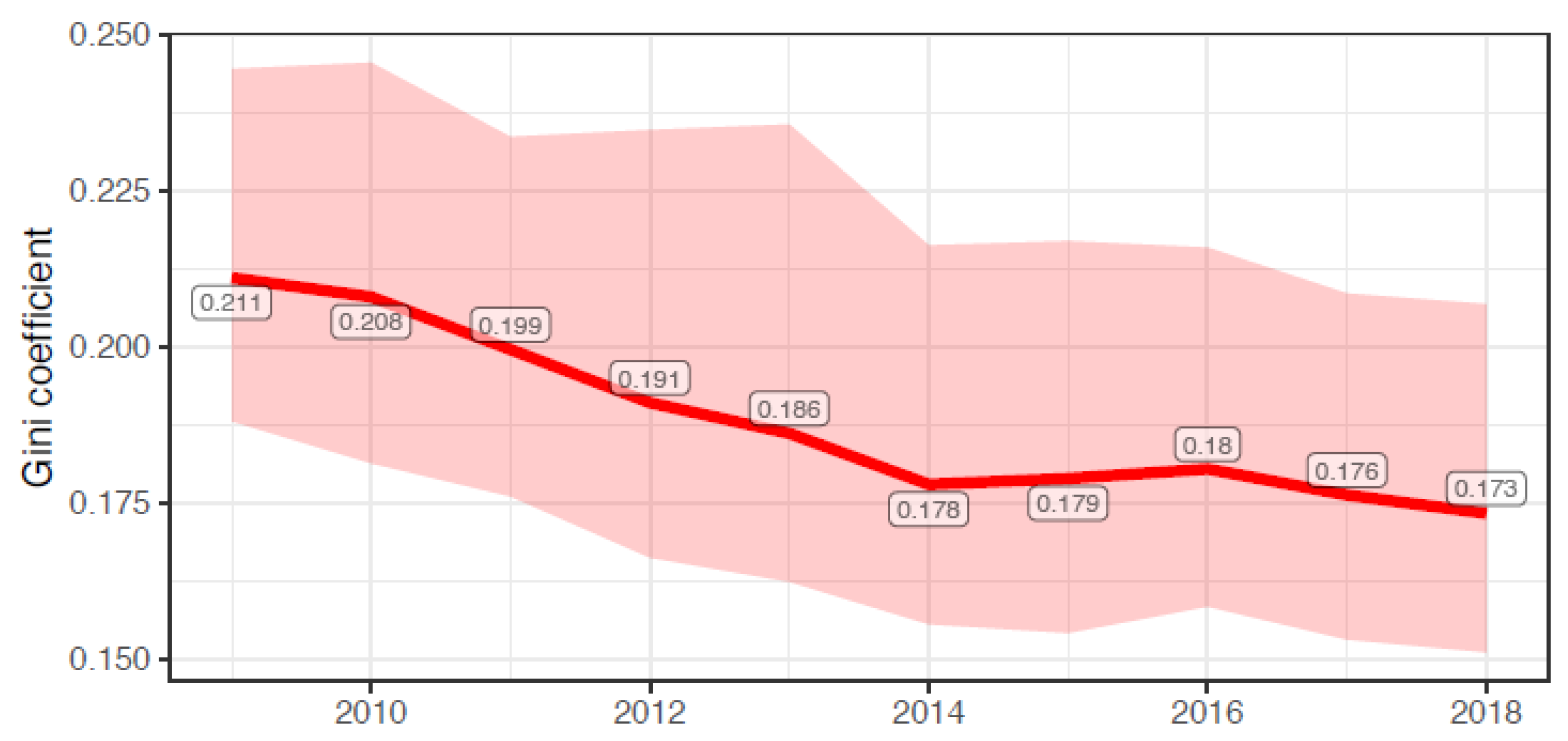

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. The Role of Touristic Accommodation in Reducing Economic Inequality

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alfani, G.; Ryckbosch, W. Growing Apart in Early Modern Europe? A Comparison of Inequality Trends in Italy and the Low Countries, 1500–1800. Explor. Econ. Hist. 2016, 62, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukowski, P.; Novokmet, F. Between Communism and Capitalism: Long-Term Inequality in Poland, 1892–2015. Cep Discuss. Pap. 2019, 1628, 1–90. [Google Scholar]

- Brea-Martínez, G.; Pujadas-Mora, J.-M. Estimating Long-Term Socioeconomic Inequality in Southern Europe: The Barcelona Area, 1481–1880. Eur. Rev. Econ. Hist. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowski, M.; van Zanden, J.L. Income and Its Distribution in Preindustrial Poland. Cliometrica 2017, 11, 375–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, P.T.; Jacks, D.S.; Levin, P.A.; Lindert, P.H. Real Inequality in Europe since 1500. J. Econ. Hist. 2002, 62, 322–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enflo, K.; Henning, M.; Schon, L. Swedish Regional GDP 1855–2000: Estimations and General Trends in the Swedish Regional System. Res. Econ. Hist. 2014, 30, 47–89. [Google Scholar]

- De Dominicis, L. Inequality and Growth in European Regions: Towards a Place-Based Approach. Spat. Econ. Anal. 2014, 9, 120–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iammarino, S.; Rodriguez-Pose, A.; Storper, M. Regional Inequality in Europe: Evidence, Theory and Policy Implications. J. Econ. Geogr. 2019, 19, 273–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sznajder, M.; Przezbórska, L. Agroturystyka [Agritourism]; PWE: Warsaw, Poland, 2006; ISBN 83-208-1607-6. [Google Scholar]

- Tew, C.; Barbieri, C. The Perceived Benefits of Agritourism: The Provider’s Perspective. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammirato, S.; Felicetti, A.M.; Raso, C.; Pansera, B.A.; Violi, A. Agritourism and Sustainability: What We Can Learn from a Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollenburg, C.; Buckley, R. Stated Economic and Social Motivations of Farm Tourism Operators. J. Travel Res. 2007, 45, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dluzewska, A.M. Well-Being versus Sustainable Development in Tourism-The Host Perspective. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 512–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dluzewska, A.M. Wellbeing versus Sustainable Development—Conceptual Framework and Application Challenges. Probl. Ekorozw. 2017, 12, 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Carrascal Incera, A.; Fernández, M.F. Tourism and Income Distribution: Evidence from a Developed Regional Economy. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, C.; Li, H.; Zhang, Q. Achieving Balanced Regional Development in China: Is Domestic or International Tourism More Efficacious? Tour. Econ. 2015, 21, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, J.L.; Li, G.; Goh, C. Tourism and Regional Income Inequality: Evidence from China. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 58, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, M.C. Does Tourism Development Promote Economic Growth in Transition Countries? A Panel Data Analysis. Econ. Model. 2013, 33, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brida, J.G.; Cortes-Jimenez, I.; Pulina, M. Has the Tourism-Led Growth Hypothesis Been Validated? A Literature Review. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 394–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WTTC Economic Impact Reports. Available online: https://wttc.org/Research/Economic-Impact (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Pablo-Romero, M.D.P.; Molina, J.A. Tourism and Economic Growth: A Review of Empirical Literature. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 8, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Seetanah, B.; Jaffur, Z.R.K.; Moraghen, P.G.W.; Sannassee, R.V. Tourism and Economic Growth: A Meta-Regression Analysis. J. Travel Res. 2019, 59, 404–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes-Jimenez, I.; Pulina, M. Inbound Tourism and Long-Run Economic Growth. Curr. Issues Tour. 2010, 13, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunduz, L.; Hatemi, J.A. Is the Tourism-Led Growth Hypothesis Valid for Turkey? Appl. Econ. Lett. 2005, 12, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dritsakis, N. Tourism as a Long-Run Economic Growth Factor: An Empirical Investigation for Greece Using Causality Analysis. Tour. Econ. 2004, 10, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaguer, J.; Cantavella-Jordá, M. Tourism as a Long-Run Economic Growth Factor: The Spanish Case. Appl. Econ. 2002, 34, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lean, H.H.; Tang, C.F. Is the Tourism-Led Growth Hypothesis Stable for Malaysia? A Note. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 12, 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Chen, M.-H.; Jang, S.S. Tourism Expansion and Economic Development: The Case of Taiwan. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brida, J.G.; Pulina, M. A Literature Review on the Tourism-Led-Growth Hypothesis. Work. Pap. Crenos 2010, 17, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Brau, R.; Lanza, A.; Pigliaru, F. How Fast Are Small Tourism Countries Growing? Evidence from the Data for 1980–2003. Tour. Econ. 2007, 13, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, A.; Temple, P.; Urga, G. The Implications of Tourism Specialisation in the Long Run: An Econometric Analysis for 13 OECD Economies. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberto, A.D. High Skills, High Growth: Is Tourism an Exception? J. Int. Trade Econ. Dev. 2013, 22, 749–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alhowaish, A.K. Is Tourism Development a Sustainable Economic Growth Strategy in the Long Run? Evidence from GCC Countries. Sustainability 2016, 8, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.G. Tourism, Trade, and Income: Evidence from Singapore. Anatolia 2012, 23, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, C.-O. The Contribution of Tourism Development to Economic Growth in the Korean Economy. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, J.E.; Mervar, A. Research Note: The Tourism-Growth Nexus in Croatia. Tour. Econ. 2010, 16, 1089–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inchausti-Sintes, F.; Voltes-Dorta, A.; Suau-Sánchez, P. The Income Elasticity Gap and Its Implications for Economic Growth and Tourism Development: The Balearic vs the Canary Islands. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brida, J.G.; Risso, W.A. Tourism as a Determinant of Long-run Economic Growth. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2010, 2, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trang, M.; Chau Duc, N. The Contribution of Tourism to Economic Growth in Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam. Middle East J. Bus. 2013, 8, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Jiang, L. A review of research on the contribution of tourism to economic growth. Tour. Trib. 2017, 32, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.X.; Jin, M.; Shi, W. Tourism as an Important Impetus to Promoting Economic Growth: A Critical Review. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 26, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriotis, K. Scale of Hospitality FIrms and Local Economic Development: Evidence from Crete. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.M.; Shaw, G. (Eds.) Tourism and Economic Development: European Experience, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1998; ISBN 978-0-471-98316-3. [Google Scholar]

- Vanegas, M.; Gartner, W.; Senauer, B. Tourism and Poverty Reduction: An Economic Sector Analysis for Costa Rica and Nicaragua. Tour. Econ. 2015, 21, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z. Deepening or Lessening? The Effects of Tourism on Regional Inequality. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Sinha, C. The Spatial Distribution of Tourism in China: Trends and Impacts. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 14, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. Income Inequality in Tourism Services-Dependent Counties. Curr. Issues Tour. 2009, 12, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balińska, A.; Zawadka, J. Znaczenie Agroturystyki w Rozwoju Obszarów Wiejskich [The Importance of Agritourism in Rural Development]. Zesz. Nauk. Sggw Ekon. I Organ. Gospod. Żywnościowej 2013, 102, 127–143. [Google Scholar]

- Marin, D. Study on the Economic Impact of Tourism and of Agrotourism on Local Communities. Res. J. Agric. Sci. 2015, 47, 160–163. [Google Scholar]

- Ciolac, R.; Adamov, T.; Iancu, T.; Popescu, G.; Ramona, L.; Rujescu, C.; Marin, D. Agritourism-A Sustainable Development Factor for Improving the ‘Health’ of Rural Settlements. Case Study Apuseni Mountains Area. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGehee, N.G.; Kim, K. Motivation for Agri-Tourism Entrepreneurship. J. Travel Res. 2004, 43, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, C. Assessing the Sustainability of Agritourism in the US: A Comparison between Agritourism and Other Farm Entrepreneurial Ventures. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 252–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Sandt, A.; McFadden, D.T. Diversification through Agritourism in a Changing U.S. Farmscape. West. Econ. Forum 2016, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, B.J.; Attavanich, W.; Jin, Y. Does Agritourism Enhance Farm Profitability? J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2014, 39, 69–87. [Google Scholar]

- Khanal, A. Agritourism and Off-Farm Work: Survival Strategies for Small Farms. Agric. Econ. 2014, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, H.; Khanal, A.R.; Mishra, A.K. Farmers’ Participation in Agritourism: Does It Affect the Bottom Line? Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2013, 42, 471–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jęczmyk, A.; Uglis, J.; Graja-Zwolińska, S.; Maćkowiak, M.; Spychała, A.; Sikora, J. Research Note: Economic Benefits of Agritourism Development in Poland—An Empirical Study. Tour. Econ. Fast Track 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giurea, R.; Ioan, A.M.; Ragazzi, M.; Cioca, L.I. Focusing Agro-Tourism Structures for Environmental Optimization. Qual. Access Success 2017, 18, 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, C.; Barbieri, C.; LaPan, C. The Influence of Agritourism on Niche Meats Loyalty and Purchasing. J. Travel Res. 2015, 55, 643–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batyk, I.M. The Importance of Local Border Traffic Between the Polish and Russia on Trade in the Era of Sanctions on the Polish Agri-Food Products. Gospod. Reg. I Miedzynar. 2015, 1, 235–246. [Google Scholar]

- Coulter, P.B. Measuring Inequality: A Methodological Handbook, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1989; ISBN 978-0-429-04287-4. [Google Scholar]

- Eliazar, I. A Tour of Inequality. Ann. Phys. 2018, 389, 306–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, T.; Smith, B.; Wills, S. Measuring Inequality. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2019, 35, 368–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitthiyot, T.; Holasut, K. A Simple Method for Measuring Inequality. Palgrave Commun. 2020, 6, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciołek, D. Estimation of gross domestic product in Polish counties. Gospod. Nar. Natl. Econ. 2017, 3, 55–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, J.A.; Zandvakili, S. Statistical Inference Via Bootstrapping for Measures of Inequality. J. Appl. Econom. 1997, 12, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, P.M.; Weiner, J.; Mitchell-Olds, T.; Woodley, R. Bootstrapping the Gini Coefficient of Inequality. Ecology 1987, 68, 1548–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, F.X.; Yilmaz, K. Better to Give than to Receive: Predictive Directional Measurement of Volatility Spillovers. Int. J. Forecast. 2012, 28, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakakis, N.; Dragouni, M.; Filis, G. How Strong Is the Linkage between Tourism and Economic Growth in Europe? Econ. Model. 2015, 44, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickey, D.A.; Fuller, W.A. Distribution of the Estimators for Autoregressive Time Series with a Unit Root. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1979, 74, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, H.H.; Shin, Y. Generalized Impulse Response Analysis in Linear Multivariate Models. Econ. Lett. 1998, 58, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GUS Local Data Bank. Available online: https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/BDL/start (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Tennekes, M. Tmap: Thematic Maps in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2018, 84, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-24277-4. [Google Scholar]

- Efron, B.; Tibshirani, R. Improvements on Cross-Validation: The 632+ Bootstrap Method. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1997, 92, 548–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, S.J.; Smith, R.J. A Spatial Decomposition of the Gini Coefficient. Lett. Spat. Resour. Sci. 2013, 6, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pforr, C.; Hosie, P. Crisis Management in the Tourism Industry: Beating the Odds? Disaster Prev. Manag. Int. J. 2010, 19, 515–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jago, L. Evaluating Economic Impacts of Major Sports Events—A Meta Analysis of the Key Trends. Curr. Issues Tour. 2013, 16, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevan, R.; Suardi, S. Panel Evidence on the Impact of Tourism Growth on Poverty, Poverty Gap and Income Inequality. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Real Tax Income Revenues | No Collective Accommodation | No Individual Accommodation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nearest Neighbors | Non-Neighbors | Nearest Neighbors | Non-Neighbors | Nearest Neighbors | Non-Neighbors | |

| 2009 | 6.00 | 94.00 | 6.01 | 93.99 | 5.96 | 94.04 |

| 2010 | 5.98 | 94.02 | 6.02 | 93.98 | 5.94 | 94.06 |

| 2011 | 6.10 | 93.90 | 6.08 | 93.92 | 6.04 | 93.96 |

| 2012 | 5.78 | 94.22 | 5.79 | 94.21 | 5.84 | 94.16 |

| 2013 | 5.82 | 94.18 | 5.83 | 94.17 | 5.93 | 94.07 |

| 2014 | 5.82 | 94.18 | 5.86 | 94.14 | 5.99 | 94.01 |

| 2015 | 5.73 | 94.27 | 5.85 | 94.15 | 6.01 | 93.99 |

| 2016 | 5.80 | 94.20 | 5.90 | 94.10 | 6.08 | 93.92 |

| 2017 | 5.81 | 94.19 | 5.91 | 94.09 | 6.07 | 93.93 |

| 2018 | 5.84 | 94.16 | 5.98 | 94.02 | 6.13 | 93.87 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tucki, A.; Pylak, K. Collective or Individual? What Types of Tourism Reduce Economic Inequality in Peripheral Regions? Sustainability 2021, 13, 4898. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094898

Tucki A, Pylak K. Collective or Individual? What Types of Tourism Reduce Economic Inequality in Peripheral Regions? Sustainability. 2021; 13(9):4898. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094898

Chicago/Turabian StyleTucki, Andrzej, and Korneliusz Pylak. 2021. "Collective or Individual? What Types of Tourism Reduce Economic Inequality in Peripheral Regions?" Sustainability 13, no. 9: 4898. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094898

APA StyleTucki, A., & Pylak, K. (2021). Collective or Individual? What Types of Tourism Reduce Economic Inequality in Peripheral Regions? Sustainability, 13(9), 4898. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094898