Abstract

How cooperatives generate and absorb social capital has attracted a great deal of attention due to the fact that they are collective organizations owned and democratically managed by their members, and, accordingly, are argued to be closely linked to the nature and dynamics of social capital. However, the extant literature and knowledge on the relationship between cooperatives and social capital remain unstructured and fragmented. This paper aims to provide a narrative literature review that integrates both sides of the relationship between cooperatives and social capital. On the one hand, one side involves how cooperatives create internal social capital and spread it in their immediate environment, and, on the other hand, it involves how the presence of social capital promotes the creation and development of cooperatives. In addition, our theoretical framework integrates the dark side of social capital, that is, how the lack of trust, reciprocal relationships, transparency, and other social capital components can lead to failure of the cooperative. On the basis of this review, we define a research agenda that synthesizes key trends and promising research avenues for further advancement of theoretical and empirical insights about the relationship between cooperatives and social capital, placing particular emphasis on rural and agricultural cooperatives.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, a wide range of literature has emerged concerning clarifying the concrete factors and mechanisms that determine the creation of social capital in enterprises [1,2,3], on the one hand, and with understanding how the existence of regional social capital can promote entrepreneurship [4,5,6,7], on the other hand. There is also consensus on the importance of considering organizational plurality, assuming that different types of organizations (public, private for-profit, and nonprofit organizations, social enterprises, and other hybrid organizations) have specific characteristics that are interrelated with the nature of social capital in different ways [8,9]. Within this framework, cooperatives have received considerable attention in the academic literature because they are considered social capital-based organizations [10,11]. Some studies have analyzed how different internal mechanisms in cooperatives generate social capital within them, and how it is then extended to the community level [10]. Other authors have studied how the presence of social capital specifically promotes the creation, growth, and development of cooperatives due to their characteristics [12,13].

There are several reasons why it is important to analyze rural and agricultural cooperatives in the context of generating and absorbing social capital. On the one hand, cooperatives are part of the ideal, more sustainable model of rural entrepreneurship proposed by Korsgaard et al. [14]. The functioning of agricultural cooperatives as “user-owned, user-controlled, user-benefited agricultural producer organisations” [15] (p. 103) heavily relies on trust, reciprocity, and interpersonal relationships, which helps to overcome market failures, reduce transaction costs, and diminish asymmetric information-related problems [16]. This type of entrepreneurship involves new combinations of local resources that create value not only for entrepreneurs but also for rural areas [14]. Ultimately, this means that cooperatives, through their internal social capital, provide their territories with greater resilience and a significant competitive advantage, since they are based on local resources rooted in the community, which reduces their external dependence [17]. In other words, rural cooperative entrepreneurship emerges as a key element that provides the territory with competitive advantages arising from the generation and extension of social capital [15].

On the other hand, several studies have shown that social capital has a positive effect on the survival and diversification of agricultural producers [18,19,20], helps improve the production capacity of small farmers by increasing trust among stakeholders, and is a valuable resource for strengthening rural organizations and achieving economic and social benefits [21]. In this regard, Moyano [22] points out that the success of the development of rural areas lies in the existence of good interactions among the various institutions and agents involved, which generates confidence among the population and makes it possible to mobilize and cooperate with the actors. In other words, social capital emerges as a key element that explains territorial development in the rural milieu through social and cooperative entrepreneurship [23].

However, the extant literature and knowledge on the relationship between cooperatives and social capital remain unstructured and fragmented. Accordingly, the main goals of this paper are two: firstly, to study the relationship between cooperatives and social capital, and, secondly, to define a research agenda that synthesizes key trends and promising research opportunities for further advancement of theoretical and empirical insights about the relationship between cooperatives and social capital, placing particular emphasis on rural and agricultural cooperatives.

We use a narrative literature review to focus on both sides of the relationship between cooperatives and social capital. On the one hand, how cooperatives create internal social capital and spread it in their immediate environment, and, on the other hand, how the stock of social capital available at the community level positively or negatively influences cooperative entrepreneurship and development. In addition, our theoretical framework also integrates the dark side of social capital, that is, how the lack of trust, reciprocal relationships, transparency, and other components of social capital can lead to the failure of the cooperative.

The paper is structured as follows. In the following section, we describe our methodology. Section 3 addresses the concept of social capital from an organizational plurality perspective. Section 4 deals with the role of cooperatives in the generation of social capital. Section 5 analyzes how the presence of social capital influences the creation and development of cooperatives. Section 6 discusses some limitations of the previous literature and proposes an agenda for future research. The final section highlights some key conclusions and practical implications.

2. Method

To conduct our literature review, we adopted a narrative approach, which can be described as “a comprehensive synthesis of existing works that often discuss theory and context with the aim of provoking thought and controversy” [24] (p. 420). In comparison to systematic literature reviews, a narrative approach relies on more informal mechanisms for organizing and analyzing the literature, but also has greater potential to provide readers with a broad overview and up-to-date knowledge about a topic-related research area [25].

Given that our research goal is to shed light on the complex, the multidimensional nature of the relationship between cooperatives and social capital, a narrative approach was selected due to its potential to comprehensively map large and complex research areas involving multiple issues for purposes of reinterpretation and interconnection [25,26]. This contrasts with systematic literature reviews, which are more suitable to address a single particular aspect or answer more specific and focused questions, usually with a meta-analysis allowing statistical pooling of data [27]. Narrative literature reviewing is argued to be a valuable theory-building technique [28], as it is especially appropriate “as a basis for generating new research questions and identifying future research directions, as well as summarizing the limitations of past work” (Hodgkinson & Ford, [29] (p. 3), see also Rousseau et al. [30]).

Our narrative literature review followed a five-step procedure (as described in Greenhalgh et al. [31] and in Hopkinson and Blois [32]): search, mapping, appraisal, synthesis, and recommendation derivation. We started by running searches in Web of Science, Scopus, Science Direct, Ebsco, and Google Scholar for combinations of relevant keywords such as “social capital”, “social networks”, “trust”, “cooperatives”, “social entrepreneurship”, “agricultural cooperatives”, and “rural entrepreneurship.” As is common in narrative literature reviews, we also carried out hand searches in key journals (e.g., Academy of Management Review, Journal of Rural Studies, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Agribusiness, and Journal of Business Venturing) and used a “snowballing” technique whereby new relevant articles are identified by scanning the reference lists of the full text papers [25,26]. We prioritized the selection of articles published in English in SSCI and Scopus ranked journals, although this did not exclude the review of seminal works and other articles published in unranked sources. Mapping basically involved identifying the key elements of the research paradigm—conceptual, theoretical, methodological, and instrumental [31]. This phase also involved discarding some papers in which social capital did not form the basis of empirical work or a substantial element of theoretical and conceptual argument [32]. After this process, 90 papers were identified as relevant for our research purposes. In the appraisal stage, we evaluated each primary study for the validity and relevance of its arguments to our review question. We also extracted and collated the key results, grouping comparable studies together and paying close attention to conflicting findings. The synthesis phase largely took part during the writing process, and basically involved providing a narrative account of the research field’s key dimensions and interconnections [31,32]. Lastly, through reflection and multidisciplinary dialogue, we distilled recommendations for practice, policy, and further research [31].

3. Social Capital: A Perspective from Organizational Plurality

The study of social capital has been structured into two schools of thought that understand the concept differently. One is the structuralist school of thought, which is more focused on individual benefits derived from social capital and conceptualizes it as a set of resources available to the individual derived from his or her participation in social networks and their norms [33,34]. From this perspective, social capital is defined as “the total of the real or potential resources that are linked to the possession of a lasting network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual knowledge or recognition” [35] (p. 2). The other school of thought, known as culturalist, focuses more on the collective effects and mutual benefits derived from social capital [36,37]. From this perspective, as Putnam [38] (p. 66) points out, “social capital refers to the characteristics of social organization such as networks, norms, and trust that facilitate coordination and cooperation for a mutual benefit.” The interpretation proposed in this paper contains both approaches.

Firms have been considered as fundamental social structures in the creation and diffusion of social capital. As Adler and Kwon [39] (p. 21) point out, “the behavior of a collective actor such as the firm is influenced both by its external links with other firms and institutions and by the fabric of its internal links.” In this sense, the literature has addressed the social capital–firm relationship from an internal and external perspective. That is, the firm has been studied according to the social capital it creates internally and the fundamental role it plays in extending its social capital to other social structures. Leana and Van Buren [40] argue that the most clear way in which firms create social capital is to cultivate relationships among their members. The firm is a key place to create social capital because its members subordinate individual objectives to the achievement of collective goals and actions, and the generation of mutual trust is fundamental to working as a team and achieving these goals.

There is a consensus that social capital improves the operation and results of firms. At the inter-firm level, social capital facilitates the firm’s access to external resources (technology, information, and knowledge) through networks of relationships with other firms [41]. In other words, the existence of social capital favors the success of business relations through the flow of resources such as knowledge, information, and other types of capital, while these transactions are sustained by mutual trust [42]. At the intra-firm level, organizational social capital is considered a key resource for businesses, since it facilitates their internal coordination, as well as collective decision-making and its effective implementation within the organization [40]. In this sense, mutual trust reduces transaction costs by reducing opportunism and the costs of monitoring and control within the firm. Similarly, the existence of high levels of social capital in the firm favors the flow and access to information, organizational innovation and learning, and the generation and accumulation of knowledge, and, in broader terms, strengthens the creation of value (see References [1,2,3]).

Likewise, we find recent studies about how the presence of social capital in a region promotes entrepreneurship [4]. Two approaches can be distinguished. One approach studies how the existence of individual social capital, understood as “the good will and resources that emanate from an individual’s network of social relations” [43] (p. 530), can favor the creation of enterprises. In this context, the literature has focused mainly on the integration of individual entrepreneurs in networks of relationships with other individuals, showing that individual social capital strengthens the capacity of entrepreneurs in various key aspects of the entrepreneurial process, such as in identifying and exploiting entrepreneurial opportunities [6,7].

Another approach analyzes whether the presence of regional social capital promotes entrepreneurial dynamism [5]. Regional social capital refers to “a resource that reflects the nature of social relations in a region, expressed in the levels of widespread trust and norms of civic behavior of its residents” [7] (p. 3). As some works empirically argue [7,44], environments characterized by the presence of social capital favor entrepreneurial dynamism, since there will be a greater flow of knowledge, resources, and information, as well as greater cooperation among social networks or diverse groups.

However, social capital is an ambivalent concept that also includes negative effects [45,46]. Among the negative consequences of social capital, Durston [47] points out the promotion of intragroup conflicts, rivalry and factionalism that can destroy the social institutions of trust and cooperation from which social capital emerges, the direct exclusion of those agents who are strangers to those who have greater trust, excessive demands on group members, and restrictions on individual freedom and downwardly levelling norms.

Analyzing these negative effects from the dimensions of social capital [48], the following can be observed.

- -

- In relation to the structural dimension, social capital in closed networks can lead to discrimination, exploitation, corruption, and domination by mafias and authoritarian systems [49,50], promoting illicit operations and markets [51,52], both within an organization and a region.

- -

- Considering the relational and cognitive dimension, the excess of trust and inadequate control in the organization can allow undetected opportunistic behaviors [53]. In terms of organizational performance [54], Molina et al. [55] find that it is conditional trust that contributes positively to the strategy formulation process, since overinvestment in trusting relationships of little value to the company can lead to misallocation of valuable resources and/or take unnecessary risks that could have substantial negative effects on its performance.

- -

- Finally, regarding the search for new opportunities, Portes and Sesenbrenner [56] show that the difficulties in freeing themselves from obligations established between companies and their current partners (in terms of trust and other considerations) can limit their capacity to take advantage of these opportunities.

These harmful effects of social capital (sectarianism, ethnocentrism, or corruption) should not obscure social capital that has beneficial effects (mutual support, cooperation, institutional trust, and effectiveness) that apply at both the organizational and regional levels [57,58,59].

In this sense, an incipient line of research analyzes the mechanisms and capacities of different types of organizations to create social capital [13,60]. There is also a growing interest in understanding how different types of organizations are capable of taking advantage of scenarios with high levels of social capital to grow and expand [61], that is, whether the presence of social capital in a given region favors, to a greater extent, the creation and maintenance of one or another organization.

A large number of studies have considered social economy organizations as fundamental vehicles for the generation and extension of social capital in communities by strengthening cooperative and solidarity values, social norms, trust, and civic attitudes [9,62,63]. Associations and other cooperative organizations are, thus, situated as nuclei that create social capital, with particularly important effects in rural areas by strengthening their socio-economic development through the reduction of production costs, minimization of risks, greater ease of access to credit, reinvestment, rooting of capital in the territory, and increased involvement and integration of rural actors in the local community [15,16].

4. Cooperatives and the Generation and Extension of Social Capital

Cooperatives are social enterprises in which trust and cooperation are basic pillars. In other words, social capital is understood as one of the main characteristics of these organizations, in comparison with capitalist enterprises, since social networks supported by norms of reciprocity and trust form the fundamental basis of cooperatives [64].

Practices and values such as responsibility, solidarity, the primacy of people over capital, and democratic participation are elements that define their functioning and give them a distinctive and unique character. Internally, the main objective of cooperatives is to meet the needs of their members and other internal stakeholders. Externally, they seek to satisfy the interests of society by providing the goods and services they produce, and even to solve the social problems affecting their local communities [13].

These principles and values, which are common to cooperatives because they reinforce cohesion and identity among members, have a people-oriented nature, offer an open, plural, and democratic organizational structure, and encourage members to build links and bridges with other social networks, both within and outside the community [65]. That is, cooperatives have the capacity to generate different types of social capital [66]. On the one hand, they generate bonding social capital (understood as networks of relationships that occur within a group or community), as they are organizations of joint ownership and democratic management created to serve their members. On the other hand, they generate bridging social capital (understood as networks of relations between groups or similar communities), as long as they are based on the principle of inter-cooperation with other cooperatives. Finally, they generate linking social capital (understood as networks of relations with other groups or external networks), since they are organizations based on solidarity and commitment to the environment and aligning with the needs of society [66].

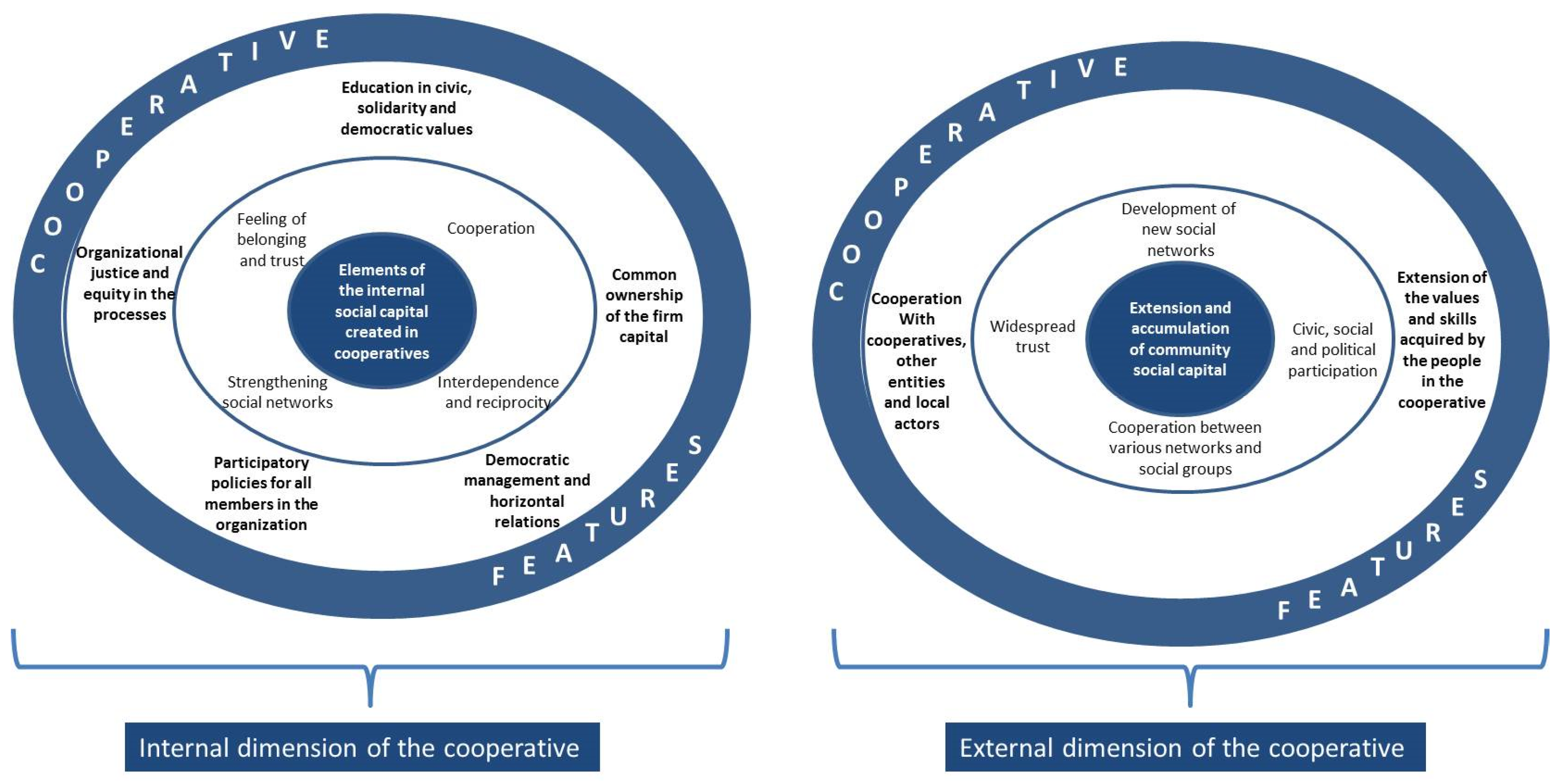

The following is a detailed analysis of the dynamics of internal generation of social capital in cooperatives and their capacity to extend and accumulate social capital at the community level. Figure 1 shows in a schematic and graphic way the interrelations in the generation and extension of social capital in the context of cooperative societies, considering their most important elements.

Figure 1.

Cooperatives and the generation and spread of social capital. Source: Own elaboration.

4.1. Internal Dimension of Cooperatives and Creation of Social Capital

Cooperatives are member-owned business organizations characterized by democratic and inclusive governance [67]. The people who are members of the cooperative are owners through their capital, but also have another transactional relationship with the cooperative (as employees, suppliers, or customers). Control of the cooperative falls under equal conditions on all its members under the rule of “one person, one vote”, regardless of the capital contributed. Voting rights are not divided in relation to capital, but in equal parts among the members. This implies, at its most fundamental level, the same power in decision-making and the election of governing bodies. That is, in the cooperative, a plurality of members shares the organization’s control rights. In turn, equality in the rights of membership implies that governance of the cooperative falls into a horizontal structure in which the decision-making power is distributed equally among all members [68].

Social capital is generated in contexts where mutual interdependence is high [2], as is the case with cooperatives, where joint ownership of the enterprise means a high degree of interdependence among the members [69]. In the same vein, the existence of horizontal and democratic relations in the organization has also been considered a key element that determines the generation of trust and social capital through cooperation and interdependence among members [38]. These aspects find a solid empirical basis in the work of Sabatini et al. [60]. Comparing the behavior of cooperatives, public enterprises, and private capitalist enterprises, their results show that cooperatives have a greater capacity to foster widespread trust, mainly because they are based on more horizontal governance models.

Organizational justice, that is, correctness in organizational procedures, transparency in the transmission of information, and equity in the management of workers’ careers, has been described as another distinctive organizational characteristic of cooperatives [70]. Organizational justice can be considered a relevant factor that also influences the generation of trust and social capital [71]. Organizational justice better distributes the (monetary and non-monetary) burdens and benefits among the parties involved, thus, creating an expectation of fair future rewards, which is an essential precondition for the emergence of trust. Moreover, the spread of fair decisions discourages opportunistic behavior in the organization and favors the accumulation of social capital. In this sense, group pressure, which is one of the key characteristics of cooperative teams, stands as a fundamental mechanism that reduces “parasitism” and promotes the creation of trust [60].

In a clearly connected way, the participation practices that characterize cooperatives are closely linked to the generation of social capital. Cooperatives are organizations characterized not only by the participation of their members in the capital, but also by other advanced policies of participatory management, such as transparency, communication, training, and involvement in daily decision-making [72]. These policies and practices are what make workers act and relate differently in the organization, thus, engendering high levels of social capital. In this line, a positive relationship has been found between worker participation and the promotion of various psychosocial indicators such as job satisfaction, motivation and commitment to the organization, empowerment, mutual aid and cooperation in the work environment, and the generation of trust [73], which are elements closely related to the creation of social capital in firms [40].

Similarly, the collective identification of members, as well as the education cooperatives, provides on shared principles and values (regarding solidarity, responsibility, and democracy) also constitute a key mechanism in the generation of trust and interdependence [74]. In this sense, Majee and Hoyt [75] provide qualitative evidence on the construction of trust among cooperative members derived from the four pillars that support the strengthening of participation and social networks in cooperatives: joint ownership, democratic decision-making processes, teamwork, and open communication. For its part, the study by Arando et al. [76] analyzes the dynamics of social capital generation in cooperatives and other types of enterprises around the dimensions of participation, trust, and social cohesion. The results indicate that cooperatives have a greater capacity to promote the creation of social capital, especially thanks to their characteristic participation practices. Likewise, the work of Bretos and Errasti [77] on the conversion of a capitalist firm into a cooperative shows how this transformation led to greater levels of companionship, cooperation, trust, participation, and, in short, social capital.

On the other hand, various aspects of negative and antithetical social capital have been found to be relevant factors that might contribute to poor performance and dysfunction in cooperatives, and eventually lead to their failure and demise [11,78]. These include a reduced level of trust and loyalty among members, determined by factors such as the lack of transparency in decision-making processes and individualistic and opportunistic behaviors [78,79]. Moreover, various authors have examined the internal organizational characteristics that can make the generation of social capital difficult. Among other factors, they highlight the increased organizational complexity and size and the diversity of partners’ interests, which can make it difficult to create personal ties among members and affect members’ involvement, trust, satisfaction, and loyalty and the adequate flow of information and knowledge sharing [69,80].

4.2. External Dimension of Cooperatives and Creation of Social Capital

The generation of social capital in cooperatives comes not only from the characteristics of their internal organization, but also from their relations with other cooperatives and organizations in the local territory. As we know, cooperatives are strongly rooted in the local environment, primarily because their members are usually residents of the territory where the cooperative is located [68]. Considering that bridging social capital can be generated by links between firms and their members with the local environment, cooperatives will have a greater capacity to generate social capital in their territory, since they create and maintain solid and lasting social networks with local suppliers and clients [13], as well as with other cooperatives and social organizations, since they are based on the principle of inter-cooperation [67].

In this sense, the work of Bauer et al. [13], which compares various types of enterprises, empirically demonstrates that cooperatives and worker-controlled firms generate a greater legacy of social capital, measured by cooperation contracts and business ties with local suppliers and customers, than do conventional capitalist firms, thus, furthering endogenous economic development and the accumulation of social capital in the local territory.

On the other hand, cooperatives also have the capacity to generate linking social capital. That is, being democratic and participative organizations, cooperatives promote the acquisition of civic and relational skills by their members, instill in them democratic and solidarity values, and, in short, favor the emergence of trust and the development of cooperation and reciprocity norms. Following an institutionalist approach (by which organizations have the capacity to generate social capital in a region [65]), it can be deduced that the social capital created and accumulated in a cooperative, based on trust and the established norms of reciprocity, influences the attitudes and behavior of members outside the cooperative, thus, moving toward the generation of social capital at the community level [10,12].

This is because, on the one hand, citizens who have developed an attitude of cooperation and trust in their working relationships are more likely to behave the same way outside the workplace. On the other hand, these citizens will be better able to represent common interests in public life, thus, improving the quality of democratic governance [60]. Therefore, it can be affirmed that participation in cooperatives favors the development of new social networks and links among members, promoting, in short, social and political participation. As shown by Majee and Hoyt’s work [75], the frequent interactions and cooperation among members of a cooperative improve participation and encourage the creation of networks among them and with other community groups, thus, strengthening trust and promoting social participation in the community.

In short, as Dasgupta [81] suggests, the added value of cooperatives lies in their ability to internalize civic attitudes, promote honesty and integrity, facilitate trust in others, and act with a sense of justice. Thus, the greater the presence of cooperatives in a region, the greater the opportunities for the community to learn and acquire specific norms and values. Some works have theoretically supported the potential of cooperatives to foster social capital in communities by promoting trust and cooperation and strengthening networks at the local level, thanks to their capacity to generate solid relationships among their members based on trust and reciprocity and their tendency to configure wide networks with other institutions, such as local governments, trade unions, or nonprofit organizations [10,65,82].

On the other hand, these processes of generating social capital in a given region can lead to the existence of widespread social pressure that promotes excessive homogenization among the members of the same community, reducing diversity and the capacity for innovation. The development of the cooperative principle of inter-cooperation [83] and the generation of greater social capital bridging should make it possible to reduce this dark side of social capital by creating links with other organizations and networks to allow external control of the system and a virtuous process toward innovation and the creation of opportunities.

5. Social Capital and Cooperative Entrepreneurship

As Uphoff [84] (p. 216) points out, social capital is “an accumulation of diverse types of assets of a social, psychological, cultural, cognitive, and institutional nature that increase the amount (or probability) of cooperative behavior aimed at obtaining mutual benefit.” From this approach, it follows that the presence of social capital in a region can lead to greater sustainability of organizational structures that will differ in their way of promoting trust and cooperative behavior. Furthermore, some works suggest that the presence of social capital in a region favors the creation and proliferation of cooperatives [61,85,86,87] since social capital, from the point of view of both trust and of social networks, is the main asset that differentiates entrepreneurs who create cooperatives and those who create other social enterprises [8].

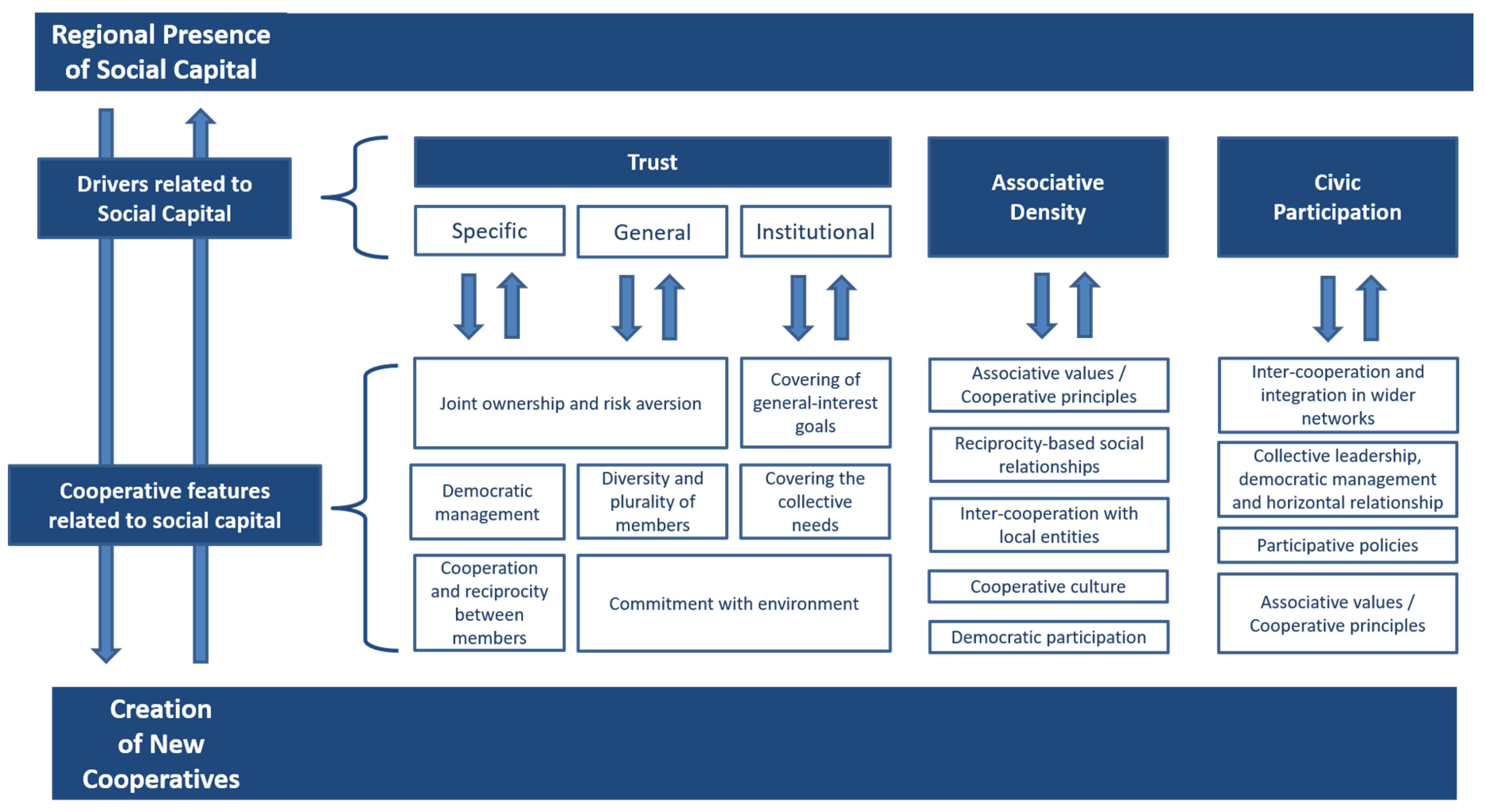

The following section examines how the presence of social capital in a region can favor the creation of cooperatives, as outlined in Figure 2. Specifically, three key factors linked to social capital are addressed: trust, associative density, and civic participation [36]. These factors have been shown to be critical in explaining the creation of cooperatives and the size and dynamism of the cooperative sector in different regions. For example, Trigkas et al. [88] largely explain the shortage of cooperatives in certain rural regions of Greece by reduced levels of trust and social interactions, participation in the local community, and voluntarism.

Figure 2.

Regional social capital and the creation of cooperatives. Source: Own elaboration.

5.1. Trust and the Creation of Cooperatives

First, a region with high levels of social capital will be characterized by the presence of greater trust. Thus, there will be greater flows of information and knowledge and a greater willingness to cooperate thanks to the reduction of conflicts between networks or groups [7,44]. Three types of trust can be distinguished: generalized, specific, and institutional. Generalized trust is based on trust in other people who are not intimately known. Specific trust refers to trust in individuals or groups that are part of closer circles. Finally, institutional trust is based on people’s trust in their institutions [44].

As noted above, cooperatives often have horizontal power and decision-making structures and their ownership is often more evenly distributed, implying the need for strong trust in the managers and other members [61]. Likewise, establishing a jointly owned enterprise such as a cooperative implies high risk, since the members usually invest a large part of their savings in creating the cooperative, which requires strong interdependence and trust among them [89]. Similarly, cooperatives tend to rely on relational contracts between members rather than formal regulations, which implies that there is less willingness to impose sanctions [90], and, consequently, trust will have much greater importance. All of these elements imply that there must be a high degree of trust among the members of a cooperative.

It has also been suggested that general trust is much more important than specific trust for the growth of the cooperative sector [61]. In this sense, cooperative members often share strong common bonds based on close personal relationships. However, further growth of cooperatives is limited precisely by the requirement for personalized relationships and trust among close members. As Fischer [91] points out, the importance of these common bonds and personal relationships decreases as the general trust in society increases. Therefore, it seems that the role of generalized trust becomes more relevant than specific trust in the creation of cooperatives. On the other hand, institutional trust also influences their creation. Cooperatives are organizations linked to public institutions, since, due to their social and economic role, they are objects of public policies [65]. That is, they are strategic actors for achieving the social and development objectives of governments [92]. Therefore, it can be said that the presence of institutional trust is a relevant factor in defining the development of cooperatives in a region. Rural cooperatives are, in many cases, the main economic engine of their area, and, consequently, a greater presence of institutional social capital in the region allows a more and better cooperative internal operation, which will lead to greater economic and social development.

Some works have empirically analyzed the relationship between the presence of trust and cooperative development. Jones and Kalmi [61] relate trust to differences in the size of the cooperative sector between countries. Taking as a reference the 300 largest cooperatives in the world as listed by the International Cooperative Alliance, they conclude that the presence of trust is a key determinant in the incidence and size of the cooperative sector. Furthermore, they argue that trust behaves more as a prerequisite for than a consequence of the size of the sector, which suggests that trust is an explanatory factor for the development of cooperatives. Similarly, Carrasco and Buendía-Martínez [86] analyze differences in the growth and size of the cooperative sector among countries in the European Union in terms of the role played by social capital. Their results support that trust (taken as a proxy for social capital) is positively related to the size of the cooperative sector in those countries.

5.2. Associative Density and the Creation of Cooperatives

Second, a region with high levels of social capital will be characterized by a high number and density of civic and voluntary associations as well as a greater membership of people in these groups [36,38,93]. Cooperatives have also been considered as organizations with a very similar nature to these types of associations, sharing common principles and values [65]. In fact, works such as Putnam’s [36] use the density of associations in a region as a proxy for measuring social capital.

It can be affirmed that, in a region with a high presence of associations, cooperative development will be favored due to the effect on cultural elements and to aspects related to the validation, internalization, and legitimization of these organizational forms [12,76,89]. Consequently, the associative culture in a region, manifested by a greater density of cooperatives, favors the creation of cooperatives thanks to the externalities of conurbation [12].

Similarly, cooperatives and other associative organizations have been described as “schools of democracy” based on cooperative values, trust, and social norms [13,63]. Various studies have shown that belonging to this type of organization encourages members to develop new social networks [62,93], thus, favoring the creation of enterprises, while the integration of entrepreneurs into various social networks facilitates the identification and exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities [7,94]. Specifically, the creation of cooperatives may be particularly favored by this factor, since, in a region with high associative density, individuals will have values and capacities that make them more likely to cooperate and participate democratically, and these are key elements for the creation of cooperatives [76,95].

In this sense, the research of Carrasco and Buendía-Martínez [86] shows that countries with a higher density of associations have greater dimension and importance in their cooperative sector. In fact, as they point out, “the set of social networks (such as those created through associations) allows individuals to acquire advantages of belonging to a community by facilitating the acquisition of skills and resources. Cooperatives incorporate a greater load of social capital because of their structural configuration and because of the process of membership” [86] (p. 141). For their part, Chloupkova et al. [87] argue that the emergence of the agricultural cooperative movement in Denmark and Poland was driven by members who were previously involved in different agricultural and cultural associations through which they created stable networks based on trust and interdependence. In a similar vein, Beltrán-Tapia [85] shows that the collective and associative management of resources through communal lands contributed decisively to the emergence of agricultural cooperatives in Spain in the early 20th century because this association provided the social networks to facilitate the dissemination of information and the construction of knowledge and mutual trust.

5.3. Civic Participation and the Creation of Cooperatives

Third, a region with high levels of social capital will be characterized by greater civic participation of people. In this context, various elements of civic participation have been employed, which are related to the presence of social capital, such as donating blood, making charitable donations, reading newspapers, signing documents in support of a cause, participating in demonstrations, working in political parties, attending electoral meetings and political events, or participating in electoral elections [36].

The common denominator of these elements is that the region will be characterized by a high level of participation by its citizens in social and political life, making it more likely that these individuals will strengthen their confidence and participate in new social networks or groups [36]. Ultimately, these conditions will encourage citizens to become interested, learn, and actively participate in various areas of local life with the aim of promoting the well-being of the community [96]. As the literature in this field has shown, these aspects encourage entrepreneurship by making it easier for enterprising individuals to contrast different visions and ideas, access new relevant information, acquire and disseminate new knowledge, or have more opportunities to obtain the necessary resources [7,43,94].

In the specific field of cooperatives, it can be said that the previously mentioned aspects will promote their sustainability. As the literature points out, the key elements of civic participation promote collective and collaborative leadership, horizontal power relations, and democratic decision-making [97]. Civic participation also fosters partnership, organization, and collective action to address the needs of individuals and society at large [98]. In this sense, cooperatives are characterized by collective processes. In addition, they are constituted to meet the needs of their own members and, on many occasions, to address the problems affecting their environment by cooperating with other local organizations and actors in broader social networks based on the alignment of general interests [13].

In short, as Conte and Jones [95] suggest, individuals with a greater capability and preference for participation may be more likely to form cooperatives, so civic participation may be a key mechanism in the process of cooperative enterprises. Ostergaard et al. [96] show that the survival rate of Norwegian cooperative savings banks is positively related to reading newspapers and making charitable donations, which are factors they use to measure the presence of regional social capital. In a more comprehensive recent study, Carrasco-Monteagudo and Buendía-Martínez [99] reveal how a high level of political activism in a region significantly promotes and nourishes the development of cooperative business ventures deeply rooted in the local environment, since political activism generates a social climate characterized by trust and strong interpersonal relationships, which is more conducive to mutualism.

6. A Further Research Agenda

6.1. Typology of Causality in the Relationship between Cooperatives and Social Capital

As our previous review has shown, there are two approaches for addressing the relationship between cooperatives and social capital: (1) Do cooperatives generate social capital internally and extend it to the community level? and (2) Does the presence of community social capital favor cooperative development in a given region? The literature suggests a positive relationship in both directions. Although, it has been analyzed in isolation. While some works point out that cooperatives generate social capital [13,60,75], others propose the opposite relationship, that is, that social capital favors the creation of cooperatives [61,85,86]. Therefore, there is apparently a “virtuous” cycle by which cooperatives and social capital interrelate and provide feedback. However, we still do not understand the predominant force and direction in this cycle and more research is needed to obtain clear evidence [65]. That is, what factor has the greatest influence, the generation of social capital by the presence of cooperatives in a region, or the creation and dissemination of cooperatives through the presence of social capital?

6.2. Internal Dynamics of Cooperatives and the Generation and Extension of Social Capital

Although the study of cooperatives comprises a prolific field for analyzing this question, it seems necessary to better understand the interrelationships among the internal dynamics of cooperatives that affect the generation of social capital, as Borzaga and Sforzi [65] point out.

First, until now, only the role of certain internal dynamics of cooperatives in the generation of social capital has been analyzed. For example, Sabatini et al. [60] focus on how the labor environment in cooperatives favors the generation of social capital. Specifically, their dependent variable is given by answers to the question: Thinking about the difference between the day you started working and today, how do you think the work environment has influenced your confidence in others? In this sense, our theoretical analysis identifies a wider range of internal factors in cooperatives that can influence the generation of social capital, such as training and education in cooperative values, organizational justice, and equity in professional careers within cooperatives, or, in broader terms, their horizontal democratic management and participation practices.

Second, previous studies analyzed the capacity of cooperatives to generate social capital according to certain dimensions of this concept. For example, Bauer et al. [13] show that they do this by encouraging the establishment of cooperative contracts and business ties with local suppliers and customers. Similarly, Sabatini et al. [60] conclude that they do it by fostering the creation of trust among members. In this line, our analysis suggests that cooperatives can promote other key dimensions of social capital such as interdependence and reciprocity among members, the feeling of belonging and mutual trust, cooperation, and the strengthening of social networks. These factors can be contrasted empirically by future studies to advance a more comprehensive understanding of how the internal dynamics of cooperatives foster the creation of social capital.

Similarly, our knowledge of the capacity of cooperatives to extend internally generated social capital to the community level is also extremely limited. Given the complexity involved in analyzing these aspects, a broader base of qualitative work, such as that of Majee and Hoyd [75], which addresses the connection of some internal mechanisms of cooperatives (such as open communication) with the extension of social capital at the community level, may shed light on this issue. Additionally, the availability of data series that allow a better approach to the concept of social capital may be key in the future to validate the conclusions of these qualitative studies.

6.3. Regional Social Capital and Its Influence on Rural Cooperative Development

Social capital varies geographically according to culture, identity patterns, and territorial belonging [36]. Some authors have considered territories with people who know how to use social capital as a factor in territorial development to be fortunate. Various studies on social capital relate its variables to rural development and the importance of social resources for establishing processes that improve the participation, management, and decision-making of the local population [22,100]. The collective action of local actors is fundamental for modifying the social links derived from certain daily routines of interaction and is an indispensable element in building proximity in its broadest sense [101]. It is, therefore, necessary to frame the study of social capital in the socio-spatial context [102]. The local institutional framework is key in both the formation of social capital and its impact on the trajectory of territorial development [103].

On the other hand, our theoretical analysis identifies several dimensions of social capital, such as associative density, civic participation, and trust (generalized, specific, and institutional), and, furthermore, maps its interrelationships with organizational aspects, such as joint ownership and member risk aversion, cooperation and reciprocity among members, collective leadership and horizontal relations, member diversity and plurality, and inter-cooperation among cooperatives and collaboration with other local organizations and institutions. Including social capital in models that analyze cooperative development in regions can help to better understand the influence of its various factors in a given region or country. Likewise, it is proposed to deepen the understanding of how different institutional levels favor cooperative entrepreneurship in rural as opposed to urban areas (given the different characteristics and conditions in both) and how the structures of territorial governance support the participation of social actors.

6.4. Quality of Social Capital and Its Relationship with Cooperatives

Cooperatives, like any other type of organization, have to obtain legitimacy to act and to access the specific resources of the rural environment. Legitimacy can be understood as a state that reflects cultural alignment, normative support, or consistency with relevant rules and laws [104]. Legitimacy is the widespread perception or assumption that an entity’s activities are desirable, correct, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions [105]. Adjusting to social expectations is important for organizations because it allows them to gain and maintain legitimacy in the eyes of their stakeholders [106]. Thus, by increasing legitimacy among stakeholders, any organization can increase its access to other critical resources needed to achieve organizational success or survive [105]. Therefore, analyzing the legitimacy of cooperatives to operate in rural areas by virtue of the quality of social capital they generate compared to other organizational forms is key to understanding their contributions to these areas. It is necessary to deepen, through qualitative research, the quality of social capital generated in rural and agricultural cooperatives.

6.5. Institutional Factors that Affect (Limit/Favor) the Expansion of the Cooperative Enterprise in Rural Areas

Considering the above, it is worth asking why cooperative societies have not reached a greater development and have a greater presence in the business life of certain regions, mainly those with a higher social capital.

Díaz-Foncea [107] points out that such supply factors (push factors such as unemployment or GDP) as demand factors (pull factors such as the entrepreneurial characteristics of the population) affect the creation and growth of these organizations to a greater extent. Likewise, formal institutional factors (the legal facilities for their creation or the number of public agencies specialized in them) or informal factors (such as the existing cooperative culture in a region) are key factors to establish the number of cooperatives created in a territory as well as in the rural area. Certainly, these factors will interrelate with those linked to social capital to affect the creation of cooperatives and the development of this sector.

Likewise, an important aspect to consider in the development of a sector is the role it is given within the socioeconomic system, that is, the functions or space assigned or recognized to that sector. This will influence the perception that society and the public authorities have of the sector and, therefore, the importance given to it within society. Despite the outstanding advantages shown in the generation of social capital, the creation of these entities requires other incentives and factors, as well as policies that promote cooperative entrepreneurship.

Different institutional spheres have made statements regarding the need to recognize cooperatives (and the Social Economy (ES) in general) as a differential reality to the company, which prioritizes other results apart from economic and financial ones. Following Chaves [108], two major groups of policies to promote the Social Economy can be clearly distinguished: on the one hand, soft policies, aimed at establishing a favorable environment in which these types of firms emerge, operate, and develop, and on the other hand, hard policies, aimed at improving the competitiveness and market access of the firms themselves as business units. Chaves and Savall [109] show that cooperatives and worker-owned firms have not been given much support during the last crisis in Spain and that the deployment of new mechanisms to promote cooperativism has been very limited.

On the contrary, some studies show the importance of articulating different institutional tools to achieve a greater relevance of cooperatives in the territory. Bastida et al. [110] show that the development of our own legislation on the Social Economy has positive implications for the promotion and consolidation of the business fabric of the Social Economy, which justifies, for example, the special tax treatment of cooperatives and highlights how, by strengthening the fiscal framework of cooperatives, it is possible to lay the foundations for sustainable economic development [111]. On this issue, a relevant work in this direction is presented in the study entitled Best Practices in Public Policies regarding the European Social Economy Post the Economic Crisis [112].

7. Conclusions

The objective of this paper was to theoretically analyze the relationship between social capital and cooperatives from a double perspective: the role of cooperatives in the generation and extension of social capital, and the influence of regional social capital in the creation of cooperatives. In this sense, several internal dynamics of cooperatives and their influence on the generation of social capital have been identified, as well as the potential mechanisms through which cooperatives can extend social capital in their local environment. The main factors related to social capital that can promote the creation of cooperatives in a given region have also been analyzed. The structuring of this set of factors and mechanisms constitutes a solid theoretical basis for future research to provide empirical evidence that will allow us to continue advancing the understanding of the two-way relationship between social capital and cooperatives. Along these lines, based on an extensive review of the literature in this field, our paper proposes an agenda for further research in which some fundamental limitations of the previous literature are detected and various strategies and tools are proposed to address them.

Our study, together with the results of further research, may have important implications at both the academic and practical level and in terms of public policy. At the academic level, we address two fundamental lines of research in the current literature. On the one hand, in recent years, there has been an extensive debate about the factors that influence the creation of worker-owned firms [76,89,113]. Our research suggests that an analysis of social capital can be useful in moving in this direction. On the other hand, after the outbreak of the last economic crisis, there has been renewed academic interest in the role of worker-owned firms in promoting sustainable local economic development and social cohesion in territories [92]. Again, this paper argues that the study of social capital may be essential to shed light on the mechanisms by which these types of enterprises promote these objectives.

Similarly, as Bretos and Marcuello [68] point out, a key question for practice lies in understanding how cooperatives that are strongly rooted in their local territories, but are also market-oriented, can align their internal objectives with the broader interests and needs of their local environments. Assuming a positive impact of internal social capital on the competitiveness and efficiency of firms [2,6] and positive effects at the community level [60], our research suggests that these organizations may find that strengthening social capital is a key way to achieve their internal and external objectives. Finally, the results of our study may have fundamental public policy implications. Given the unique capabilities of cooperatives to generate social capital, local governments interested in promoting endogenous economic development and strengthening community ties could facilitate and encourage the creation of these organizations to achieve this. This is particularly critical in a context in which, paradoxically, public policies aimed at promoting participatory enterprises have clearly been undermined in recent years despite the essential socio-economic role these organizations play in today’s society.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.B. and M.D.-F.; methodology, I.B.; validation, I.B., I.S.-G. and M.D.-F.; formal analysis, I.S.-G. and I.B.; writing—original draft preparation, I.B.; writing—review and editing, I.B., M.D.-F., and I.S.-G.; funding acquisition, I.S.-G. and M.D.-F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Regional Government of Aragon and the European Regional Development Fund (Construyendo Europa desde Aragón), grant number GESES S28_17R. Likewise, the research has been supported by the project Economic Rationality, Political Ecology and Globalization: towards a new cosmopolitan rationality [PID2019-109252RB-I00], granted by the State Agency for Research—Ministry of Science and Innovation of the Kingdom of Spain [State Program for R+D+i Oriented to the Challenges of Society].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sanchez-Famoso, V.; Maseda, A.; Iturralde, T. The role of internal social capital in organisational innovation. An empirical study of family firms. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 950–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.Y.; Liu, C.-W. High performance work systems and organizational effectiveness: The mediating role of social capital. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2015, 25, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastoriza, D.; Arino, M.A.; Ricart, J.E.; Canela, M.A. Does an ethical work context generate internal social capital? J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 129, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, I.; Dana, L. Boundaries of social capital in entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2013, 37, 603–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.-W.; Heflin, C.; Ruef, M. Community social capital and entrepreneurship. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2013, 78, 980–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, W.; Arzlanian, S.; Elfring, T. Social capital of entrepreneurs and small firm performance: A meta-analysis of contextual and methodological moderators. J. Bus. Ventur. 2014, 29, 152–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, M.; González-Álvarez, N. Social capital effects on the discovery and exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2016, 12, 507–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedajlovic, E.; Honig, B.; Moore, C.B.; Payne, G.T.; Wright, M. Social capital and entrepreneurship: A schema and research agenda. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2013, 37, 455–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauwens, T.; Defourny, J. Social capital and mutual versus public benefit: The case of renewable energy cooperatives. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2017, 88, 203–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentinov, V.L. Toward a social capital theory of cooperative organisation. J. Coop. Stud. 2004, 37, 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Spognardi, A. Cooperatives and Social Capital: A Theoretically-Grounded Approach. CIRIEC-Esp Rev Econ Pública Soc Coop. 2019, 97, 313–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arando, S.; Gago, M.; Podivinsky, J.M.; Stewart, G. Do labour-managed firms benefit from agglomeration? J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2012, 84, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, C.M.; Guzmán, C.; Santos, F.J. Social capital as a distinctive feature of Social Economy firms. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2012, 8, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsgaard, S.; Müller, S.; Tanvig, H.W. Rural entrepreneurship or entrepreneurship in the rural–between place and space. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2015, 21, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tregear, A.; Cooper, S. Embeddedness, social capital and learning in rural areas: The case of producer cooperatives. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 44, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kustepeli, Y.; Gulcan, Y.; Yercan, M.; Yıldırım, B. The role of agricultural development cooperatives in establishing social capital. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2020, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristow, G. Resilient regions: Replaceing regional competitiveness. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeffner, M.; Baggio, J.A.; Galvin, K. Investigating environmental migration and other rural drought adaptation strategies in Baja California Sur, Mexico. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2018, 18, 1495–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuepper, D.; Yesigat Ayenew, H.; Sauer, J. Social capital, income diversification and climate change adaptation: Panel data evidence from rural Ethiopia. J. Agric. Econ. 2018, 69, 458–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaméogo, T.B.; Fonta, W.M.; Wünscher, T. Can social capital influence smallholder farmers’ climate-change adaptation decisions? Evidence from three semi-arid communities in Burkina Faso, West Africa. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellucci, D.I. Empresas, capital social y calidad. Un estudio de casos múltiples en Mar del Plata, Argentina. Estud. Perspect. En Tur. 2013, 22, 1096–1120. [Google Scholar]

- Moyano, E. Capital social, gobernanza y desarrollo en áreas rurales. Ambient. La Rev. del Minist. de Medio Ambiente 2009, 88, 112–126. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, R.; Fink, M. Rural social entrepreneurship: The role of social capital within and across institutional levels. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 70, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meglio, O.; Risberg, A. The (mis) measurement of M&A performance—A systematic narrative literature review. Scand. J. Manag. 2011, 27, 418–433. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Woods, M.; Agarwal, S.; Jones, D.; Young, B.; Sutton, A. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: A review of possible methods. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2005, 10, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, B.M.; Skinningsrud, B.; Vikse, J.; Pękala, P.A.; Walocha, J.A.; Loukas, M.; Tubbs, R.S.; Tomaszewski, K.A. Systematic reviews versus narrative reviews in clinical anatomy: Methodological approaches in the era of evidence-based anatomy. Clin. Anat. 2018, 31, 364–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denyer, D.; Tranfield, D. Producing a systematic review. In The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Research Methods; Buchanan, D.A., Bryman, A., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2009; pp. 671–689. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. Writing narrative literature reviews. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1997, 1, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkinson, G.P.; Ford, J.K. Narrative, meta-analytic, and systematic reviews: What are the differences and why do they matter? J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, S1–S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, D.M.; Manning, J.; Denyer, D. 11 Evidence in management and organizational science: Assembling the field’s full weight of scientific knowledge through syntheses. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2008, 2, 475–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Robert, G.; Macfarlane, F.; Bate, P.; Kyriakidou, O.; Peacock, R. Storylines of research in diffusion of innovation: A meta-narrative approach to systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 61, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkinson, G.C.; Blois, K. Power-base research in marketing channels: A narrative review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. The forms of capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Greenwood: New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J. Foundations of Social Theory; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Le capital social: Notes provisoires. Actes Rech. En Sci. Soc. 1980, 31, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D.; Leonardi, R.; Nanetti, R.Y. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1994; ISBN 1-4008-2074-X. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama, F. Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995; Volume 99. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 0-7432-0304-6. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, P.S.; Kwon, S.-W. Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leana III, C.R.; Van Buren, H.J. Organizational social capital and employment practices. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 538–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitt, M.A.; Lee, H.-U.; Yucel, E. The importance of social capital to the management of multinational enterprises: Relational networks among Asian and Western firms. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2002, 19, 353–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koka, B.R.; Prescott, J.E. Strategic alliances as social capital: A multidimensional view. Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 795–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carolis, D.M.; Litzky, B.E.; Eddleston, K.A. Why networks enhance the progress of new venture creation: The influence of social capital and cognition. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 527–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.-W.; Arenius, P. Nations of entrepreneurs: A social capital perspective. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, A. Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1998, 24, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, A. Downsides of social capital. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 18407–18408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durston, J. ¿ Qué es el Capital Social Comunitario? Serie Políticas sociales, nº 38; Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL): Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, A.; Landolt, P. Social capital: Promise and pitfalls of its role in development. J. Lat. Am. Stud. 2000, 32, 529–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putzel, J. Policy arena: Accounting for the ‘dark side’of social capital: Reading Robert Putnam on democracy. J. Int. Dev. J. Dev. Stud. Assoc. 1997, 9, 939–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macit, R. Becoming a drug dealer in Turkey. J. Drug Issues 2018, 48, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalonga-Olives, E.; Kawachi, I. The dark side of social capital: A systematic review of the negative health effects of social capital. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 194, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langfred, C.W. Too much of a good thing? Negative effects of high trust and individual autonomy in self-managing teams. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 385–399. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, R.M. Trust and distrust in organizations: Emerging perspectives, enduring questions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1999, 50, 569–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Morales, F.X.; Martínez-Fernández, M.T.; Torlò, V.J. The dark side of trust: The benefits, costs and optimal levels of trust for innovation performance. Long Range Plann. 2011, 44, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, A.; Sensenbrenner, J. Embeddedness and immigration: Notes on the social determinants of economic action. Am. J. Sociol. 1993, 98, 1320–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graeff, P.; Svendsen, G.T. Trust and corruption: The influence of positive and negative social capital on the economic development in the European Union. Qual. Quant. 2013, 47, 2829–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. El Declive del Capital Social; Círculo de Lectores: Barcelona, Spain, 2003; ISBN 84-8109-421-8. [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein, B. The Quality of Government: Corruption, Social Trust, and Inequality in International Perspective; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2011; ISBN 0-226-72958-3. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini, F.; Modena, F.; Tortia, E. Do cooperative enterprises create social trust? Small Bus. Econ. 2014, 42, 621–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.C.; Kalmi, P. Trust, inequality and the size of the co-operative sector: Cross-country evidence. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2009, 80, 165–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollebaek, D.; Selle, P. The importance of passive membership for social capital formation. In Generating Social Capital; Springer: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 67–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hooghe, M.; Stolle, D. Generating Social Capital: Civil Society and Institutions in Comparative Perspective; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; ISBN 1-4039-7954-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hogeland, J.A. The economic culture of US agricultural cooperatives. Cult. Agric. 2006, 28, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzaga, C.; Sforzi, J. Social capital, cooperatives and social enterprises’. In Social Capital and Economics; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 193–214T. [Google Scholar]

- Marcuello Servós, C.; Saz Gil, M.I. Los principios cooperativos facilitadores de la innovación: Un modelo teórico. REVESCO Rev Estud Coop. 2008, 94, 59–79. [Google Scholar]

- Birchall, J. People-centred businesses. In People-Centred Businesses; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bretos, I.; Marcuello, C. Revisiting globalization challenges and opportunities in the development of cooperatives. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2017, 88, 47–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, J.; Svendsen, G.L.; Svendsen, G.T. Are large and complex agricultural cooperatives losing their social capital? Agribusiness 2012, 28, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortia, E.C. Worker well-being and perceived fairness: Survey-based findings from Italy. J. Socio-Econ. 2008, 37, 2080–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, A.; Benson, P. Organisational justice climate, social capital and firm performance. J. Manag. Dev. 2013, 32, 721–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretos, I.; Errasti, A. Challenges and opportunities for the regeneration of multinational worker cooperatives: Lessons from the Mondragon Corporation—a case study of the Fagor Ederlan Group. Organization 2017, 24, 154–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, R.R.; Wright, P.M. The impact of high-performance human resource practices on employees’ attitudes and behaviors. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 366–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ole Borgen, S. Identification as a trust-generating mechanism in cooperatives. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2001, 72, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majee, W.; Hoyt, A. Are worker-owned cooperatives the brewing pots for social capital? Community Dev. 2010, 41, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arando, S.; Peña, I.; Verheul, I. Market entry of firms with different legal forms: An empirical test of the influence of institutional factors. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2009, 5, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretos, I.; Errasti, A. Dinámicas de regeneración en las cooperativas multinacionales de Mondragón: La reproducción del modelo cooperativo en las filiales capitalistas. CIRIEC-Esp. Rev. Econ. Pública Soc. Coop. 2016, 86, 4–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kasabov, E. Investigating difficulties and failure in early-stage rural cooperatives through a social capital lens. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2016, 23, 895–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamprinopoulou, C.; Tregear, A.; Ness, M. Agrifood SMEs in Greece: The role of collective action. Br. Food J. 2006, 108, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Friis, A.; Nilsson, J. Social capital among members in grain marketing cooperatives of different sizes. Agribusiness 2016, 32, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, P. Economic progress and the idea of social capital. In Social Capital A Multifaceted Perspective; Dasgupta, P., Serageldin, I., Eds.; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; pp. 325–424. [Google Scholar]

- Giagnocavo, C.; Gerez, S.; Sforzi, J. Cooperative bank strategies for social-economic problem solving: Supporting social enterprise and local development. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2012, 83, 281–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICA. Declaration on Cooperative Identity; International Cooperative Alliance: Manchester, UK, 1995; Available online: https://www.ica.coop/en/cooperatives/cooperative-identity (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Uphoff, N. Understanding social capital: Learning from the analysis and experience of participation. In Social Capital A Multifaceted Perspective; Dasgupta, P., Serageldin, I., Eds.; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; pp. 215–249. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán Tapia, F.J. Commons, social capital, and the emergence of agricultural cooperatives in early twentieth century Spain. Eur. Rev. Econ. Hist. 2012, 16, 511–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, I.; Buendía-Martínez, I. El tamaño del sector cooperativo en la Unión Europea: Una explicación desde la teoría del crecimiento económico. CIRIEC-Esp. Rev. Econ. Pública Soc Coop. 2013, 78, 125–148. [Google Scholar]

- Chloupkova, J.; Svendsen, G.L.H.; Svendsen, G.T. Building and destroying social capital: The case of cooperative movements in Denmark and Poland. Agric. Hum. Values 2003, 20, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigkas, M.; Partalidou, M.; Lazaridou, D. Trust and Other Historical Proxies of Social Capital: Do They Matter in Promoting Social Entrepreneurship in Greek Rural Areas? J. Soc. Entrep. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérotin, V. Entry, exit, and the business cycle: Are cooperatives different? J. Comp. Econ. 2006, 34, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, H.S.; Sykuta, M.E. Farmer trust in producer-and investor-owned firms: Evidence from Missouri corn and soybean producers. Agribus. Int. J. 2006, 22, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, K.P. Financial Cooperatives: A “Market Solution” to SME and Rural Financing 1998; CREFA Working Paper 98–03; Laval University: Quebec, QC, Canada, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Monzón, J.L. Empresas sociales y economía social: Perímetro y propuestas metodológicas para la medición de su impacto socioeconómico en la UE. Rev Econ Mund. 2013, 35, 151–163. [Google Scholar]

- Stolle, D. The sources of social capital. In Generating Social Capital; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 19–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bergh, P.; Thorgren, S.; Wincent, J. Entrepreneurs learning together: The importance of building trust for learning and exploiting business opportunities. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2011, 7, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, M.A.; Jones, D.C. On the entry of employee-owned firms: Theory and evidence from US manufacturing industries, 1870–1960. Adv. Econ. Anal. Particip. Labor Manag. Firms 2015, 16, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ostergaard, C.; Schindele, I.; Vale, B. Social capital and the viability of nonprofit firms: Evidence from Norwegian savings banks. In Proceedings of the AEA Annual Meeting, New Orleans, LA, USA, 4–6 January 2008; Available online: http://www.mktudegy.hu/files/SchindeleI.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Rosenthal, C.S. Determinants of collaborative leadership: Civic engagement, gender or organizational norms? Polit. Res. Q. 1998, 51, 847–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.; Ahn, T.-K. Una perspectiva del capital social desde las ciencias sociales: Capital social y acción colectiva. Rev. Mex. Sociol. 2003, 65, 155–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, I.; Buendía-Martínez, I. Political Activism as Driver of Cooperative Sector. Voluntas 2020, 31, 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teilmann, K. Measuring social capital accumulation in rural development. J. Rural Stud. 2012, 28, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, A.; Rallet, A. Proximity and localization. Reg. Stud. 2005, 39, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naughton, L. Geographical narratives of social capital: Telling different stories about the socio-economy with context, space, place, power and agency. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2014, 38, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyx, J.; Leonard, R. The conversion of social capital into community development: An intervention in Australia’s outback. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2010, 34, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W. Institutions and Organizations, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brønn, P.S.; Vidaver-Cohen, D. Corporate motives for social initiative: Legitimacy, sustainability, or the bottom line? J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Foncea, M. Sociedades Cooperativas y Emprendedor Cooperativo: Análisis de los Factores Determinantes de su Desarrollo. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Zaragoza, Zaragoza, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves, R. Las actividades de cobertura institucional: Infraestructuras de apoyo y políticas de apoyo a la economía social. In La Economía Social en España en el Año 2008; Monzón, J.L., Ed.; Ciriec-España: Valencia, Spain, 2010; pp. 565–592. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves, R.; Savall, T. La insuficiencia de las actuales políticas de fomento de cooperativas y sociedades laborales frente a la crisis en España. REVESCO Rev. Estud. Coop. 2013, 113, 61–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastida, M.; Vaquero, A.; Cancelo, M. La contribución de la ley de economía social de Galicia al desarrollo territorial ya la mejora del empleo. Revesco 2020, 134, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- García, A.V.; Bastida, M.; Taín, M.Á.V. Tax measures promoting cooperatives: A fiscal driver in the context of the sustainable development agenda. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2020, 26, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, R.; Monzón, J.L. Best Practices in Public Policies Regarding the European Social Economy Post the Economic Crisis–Study. 2018. Available online: https://www.eesc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/files/qe-04-18-002-en-n.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2020).