Abstract

This paper examines two core issues of the university-based entrepreneurship education ecosystem by explicating the key elements of the ecosystem and their roles, and the development process and sustainable construction strategy of the ecosystem. Thirty stakeholders of ecosystems from the US universities were interviewed, and the transcripts of these interviews were coded through a three-phase process, including open, axial, selective coding, and were analyzed based on the grounded theory. It was found that (i) the key elements of the university-based entrepreneurship education ecosystem consist of six units (colleges and universities, learners, educators, government, industry, and community) acting as initiators and seven factors (entrepreneurship curriculum, entrepreneurial activities and practices, organizational structure, resources, leadership vision, core faculty, and operating mechanism) acting as the intermediaries; (ii) These key elements constitute three independent functional subsystems, namely, teaching and innovation, support, and operation that are interconnected by the universities; (iii) The development process of a university-based entrepreneurship education ecosystem involves seven steps as preparation, germination, growth, equilibrium, stagnation, recession, and collapse; (iv) For sustainability, suggestions on a solid foundation, continuous investment, and constant monitoring are provided to university administrators and policymakers to advance higher education’s contribution to social and economic development.

1. Introduction

The importance of entrepreneurship has been widely recognized as one of the driving forces of economic and social development [1,2]. University-based entrepreneurship education is a key link in the establishment of new enterprises, cultivation of innovative talents, scientific, and technological innovation [3,4]. Consequently, entrepreneurship education has become a buzzword in national strategies of various countries and regions, such as the Small Business Innovation Research program of the US [5], the European Education Area of the European Union [6,7], and the Innovation-driven development strategy of China [8]. For institutions of higher education, classroom teaching is the main channel to provide education services for the learners. Therefore, for a long time, scholars and educators have taken entrepreneurship education curriculum and programs as the main field of research [9,10] to reveal the causal conclusions related to entrepreneurship education and improve its impact [11,12]. As far as the output of the whole university is concerned, entrepreneurship courses and programs are the core components of entrepreneurship education, but they are not the whole story. The other components ignored by researchers to some degree may also play a vital role in achieving entrepreneurship-related outcomes. Based on the recognition of this view, recent studies [13,14] have shown that scholars have begun to re-examine the entrepreneurship education in higher education institutions from a system theory perspective. More specifically, ecosystems have become a new research perspective for entrepreneurship education.

Typically, entrepreneurship education ecosystem research requires a systematic approach to explore and study entrepreneurship education issues. Compared with previous studies on entrepreneurship education, the research perspective of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem is considered as a truly systematic and interdisciplinary research method [13,15,16]. The term ‘ecosystem’ comes from biology [17] and has been adopted by many fields as a research perspective or method, including entrepreneurship education. Overall, an entrepreneurship education ecosystem research has two characteristics: case-based research and inductive research. In entrepreneurship education ecosystem research, scholars usually choose one or more university-based entrepreneurship education ecosystems as research objects (cases) [18,19] and then drive conclusions from the outcomes and attributes of the selected universities through a process of scientific induction [18,20]. Although the research on entrepreneurship education ecosystem has many advantages in research systematization [21], relationship research [22], and input–output comparison [23], the two characteristics mentioned above have shortcomings in terms of adaptability and portability, especially when administrators are looking for examples and guidance that are suitable for their universities to establish or enhance their entrepreneurship education ecosystems for sustainability. The reason for this dilemma is that different administrators and educators face different and complex university environments in terms of historical development, staff and student backgrounds, resources and culture, etc., and their entrepreneurship education ecosystems may also be at different stages of development. Inspired by the above issues, the purpose of this study is to seek answers to the following two research questions through interviews and analysis processes:

- QI. What are the key elements of a university-based entrepreneurship education ecosystem?

- QII. Based on the role, importance, and relationship of the constituent key elements, what strategies could be followed to build a sustainable university-based entrepreneurship education ecosystem?

The contribution of this study is to provide a dynamic and interactive view of the university-based entrepreneurship education ecosystem lifecycle process, rather than a static snapshot of the cases presented in previous studies at a certain stage. Hence, the conclusions of this research are drawn based on the views of 30 stakeholders from many different institutions. The study also focuses on the key elements that are generally applicable to the best practices of starting and growing an entrepreneurship education ecosystem for sustainability. The finding of this study may guide the executives and educators of higher education institutions in building their entrepreneurship education ecosystem to strengthen, modify, or rethink the role of different elements in the ecosystem and maintain their entrepreneurship education ecosystem in a healthy and sustainable operating status.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Entrepreneurial Ecosystem

Tansley [24] first coined the term “ecosystem” to recognize the integration of the biotic community and its physical environment as a fundamental unit of ecology within a hierarchy of physical systems that span the range from atom to universe. Since the 1950s, the idea of human–ecological systems as an integrated biosocial approach to understanding communities, urban areas, and environments has been on the rise [18]. In 1982, Nelson and Winter [25] brought the concept of ecosystems to evolutionary economic theory in their work, since economics has always been about the systems that explain differential output and outcomes [26]. As the strategic literature framework of the business ecosystems was constantly improved by Moore [27] and later Iansiti and Levien [28], the concept of an ecosystem was applied to more fields, including knowledge ecosystems [17], entrepreneurial ecosystems [29], organizational ecosystems [30], and so on. In general, the ecosystem is a biotic community encompassing the physical environment and all living entities, and all the complex interactions that facilitate its co-existence, co-dependence, and co-evolution [26]. Therefore, the advantage of ecosystem theory lies in the study of the individual within its overall environment [31]. This systematic view can consider both the individual and the environment [32], so it has been widely developed and applied in recent years, including in the field of the entrepreneurial ecosystem.

The entrepreneurial ecosystem utilizes a ‘systemic view of entrepreneurship’ [31] or ‘ecosystem research approach’ [26] to look at issues related to entrepreneurship. The concept of the entrepreneurial ecosystem has diversely been used in the literature, some of which definitions are concise and rich in general, such as ‘an interconnected group of actors in a local geographic community committed to sustainable development through the support and facilitation of new sustainable ventures’ [29], or ‘a set of interdependent actors and factors coordinated in such a way that they enable productive entrepreneurship within a particular territory’ [33]. Although many studies have shown a correlation between the number of new firms and economic growth, the earlier methods failed to produce a convincing causal relationship between them [34]. The entrepreneurial ecosystem approach is a better way to deal with these complex problems, which the neoclassical economic approach may not appropriately address [35]. The emerging research on the entrepreneurial ecosystem involves evolutionary, socially interactive, and non-linear approaches, and the interactive nature of entrepreneurial processes is in contrast with previous literature that treats it as unitary, atomistic, and individualistic [36,37]. Another feature of the entrepreneurial ecosystem approach is to emphasize the key role of entrepreneurs in innovation [38], while also focusing on several other key actors, including large firms, universities, financial firms, and public organizations that support new and growing firms [39,40]. With the unique perspective and approaches of the entrepreneurial ecosystem recognized by scholars, the number of relevant researches has gradually increased, especially since 2010. Malecki [41] and Cavallo, et al. [42] performed a meta-analysis of publications on the entrepreneurial ecosystem, and the results showed that the entrepreneurial ecosystem has quickly emerged as a promising research area in entrepreneurship. However, Isenberg [43] also pointed out that the popular ecosystem theory of the natural sciences should be applied prudently in the field of entrepreneurship since the ecosystem metaphor does not completely fit entrepreneurship in terms of the creation, the centralized control, the geography, the intention, and the entrepreneur-centrality.

Research on the entrepreneurial ecosystem has two major lineages: the strategy literature and the regional development literature [26]. Although the origins are the same, there are three differences between the two lineages. First, the regional development literature focuses more on the boundaries of ecosystems, while the strategy literature generally ignores regions or assumes a global context [44]. Second, the conclusion of the regional development literature is to explain regional performance or inter-regional performance differences, while the strategy literature focuses on the value creation and value capture by individual firms (units) [45]. Third, the strategy literature assumes that some units play a key or leading role in the ecosystem [46], and these units are called ‘lead firm’ [47], ‘keystone’ [48], or ‘ecosystem captain’ [49], etc. In contrast, the regional development literature tends to decentralize, which emphasizes the mutual promotion of units within the ecosystem [33].

According to the classification of the research literature on ecosystem theory by Jacobides, et al. [50], the literature on the entrepreneurial ecosystem can be divided into three categories: environmental, innovative, and framework research. Environmental research focuses on individual firms or start-ups, and ecosystems are viewed as the structural environment in which new ventures are launched. The research goals of this type of research are related to discovering the interaction mechanism between the company and the ecosystem, such as monitoring or responding to the business environment [51]. Innovative research focuses on a focal innovation and the set of components (upstream) and complements (downstream) that support it in the ecosystem [52]. The emphasis of this type of research is on understanding how interdependent units in an ecosystem interact, such as knowledge sharing [53], collaborative investment [54], product complementarity [55], etc., to create and commercialize innovation. Framework research focuses on the structure, operation, and development of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Case analysis is a prominent methodology in this kind of research. For example, Silicon Valley [23,56], Boulder [57], Stanford [58], and Oxford [59,60] are all studied as a case of an entrepreneurial ecosystem framework. In addition to the three types of research described above, there are also some systematic and comprehensive studies of the entrepreneurial ecosystem in the form of academic monographs [61,62]. Regardless of the type of research, almost all cited work above considers entrepreneurship education or universities as playing an important role in the entrepreneurial ecosystem [18,63].

2.2. Entrepreneurship Education Ecosystem

With the popularity and development of research on entrepreneurial ecosystems, the important role of entrepreneurship education and universities in the ecosystem has been increasingly recognized. For instance, with the implementation of the Bayh-Dole Act in the US, which allowed inventors and universities to retain the ownership of intellectual property arising from federally-funded research [64], the research from the perspective of an entrepreneurial ecosystem has started paying more attention to the university [16]. As Rice, et al. [65] note, universities are at the hub of economic development around the world, providing infrastructure, resources, and means to develop entrepreneurial communities. They argue that entrepreneurial ecosystems evolve and expand through the specialization of knowledge and innovation. Therefore, the concept of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem was proposed.

The entrepreneurship education ecosystem refers to those dynamic systems of integrated networks and associations aligned to entrepreneurship education programs [66]. Entrepreneurship education programs are various concrete manifestations of entrepreneurship education, whereby entrepreneurship skills, knowledge, guidance, assistance, and information are disseminated to various stakeholders [67]. In a monograph, Rice, Fetters and Greene [65] systematically analyzed the entrepreneurial ecosystems of six universities and summarized success factors. This research perspective marks the starting point for the research on the entrepreneurship education ecosystem, which decomposes university and entrepreneurship education as an ecosystem rather than as an integral unit within the ecosystem. Since 2010, the research on the entrepreneurship education ecosystem has gradually increased, especially in the past three years as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Number of the research results on entrepreneurship education ecosystem.

In line with the entrepreneurial ecosystem approach, the research on the entrepreneurship education ecosystem can also be divided into two categories. One is to view the entrepreneurship education ecosystem as a subsystem of the entrepreneurial ecosystem. For example, Regele and Neck [68] considered entrepreneurship education as a nested sub-ecosystem within the broader entrepreneurship ecosystem, discussed entrepreneurship education across three distinct levels-K12, higher education, and vocational training, and proposed that entrepreneurship education must develop such coherence by building a network of education programs that fit together in a coordinated way. Another kind of entrepreneurship education ecosystem research is university-based. Such research studies generally point out that universities are at the hub of economic development around the World, providing infrastructure, resources, and means to develop entrepreneurial communities. It is argued that a university-based entrepreneurial ecosystem may evolve and expand through the specialization of knowledge and innovation. An example of such research was given by Brush [18], who explored the concept of an entrepreneurship education ecosystem and adopted the dimensions of infrastructure, stakeholders, and resources to characterize the internal entrepreneurship education ecosystem based on the research of Rice, Fetters and Greene [65]. Although these two types of studies both cover the entrepreneurship education ecosystem and universities in terms of content, few achievements in the current literature specifically take the university-based entrepreneurship education ecosystem as the research object. The university-based entrepreneurship education ecosystem plays an important role in the whole entrepreneurial ecosystem, which is the intersection of these two kinds of studies. Therefore, the research on the university-based entrepreneurship education ecosystem has important significance to the literature contribution, which is also the starting point of this study.

2.3. Composition of the Entrepreneurship Education Ecosystem

Similar to the entrepreneurial ecosystem research, the entrepreneurship education ecosystem is dominated by case studies or comparative studies between cases, while the composition is still the focus and foundation. Composition research studies the framework of the functional units in the entrepreneurship education ecosystem and the interactions among these units. Examples of relatively simple frameworks are the three-dimensional ecosystem framework of entrepreneurship curriculum, entrepreneurship co-curricular, and entrepreneurship research proposed by Brush [18]. Ferrandiz, et al. [69] expanded Brush’s framework to seventeen constituent components. Based on Brush’s framework, Wraae and Thomsen [14] also explored the interaction among stakeholders, including educators, students, institutions, external organizations, and communities. Examples of complex frameworks are the research of De Jager, et al. [70] and Mogollón, et al. [71] on the entrepreneurship education ecosystem in universities. In addition, the research on the interaction among twelve stakeholder groups in the entrepreneurship education ecosystem framework of Bischoff, et al. [72] is also representative, and the relationship among stakeholders was divided into nine relationship types according to the cross combination of coordination and strength. The representative studies on the composition of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem in the literature are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Representative composition of entrepreneurship education ecosystem in the literature.

From these representative studies on the composition of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem, four characteristics could be summarized. First, although there are differences in the naming and classification of the composition, these elements are entrepreneurial stakeholders that are centered around the main functions of universities [73,74,75], among which education [76] and scientific research [23] are at the core of an ecosystem. Second, the boundaries of the university-based entrepreneurship education ecosystem are not determined by the ‘walls’ of the university [19] because institutions, organizations, industries, communities, and other external elements, which are independent of the university, are also included in the scope of the ecosystem [56,66,77]. Third, the elements that make up the entrepreneurship education ecosystem may be tangible such as incubators, teachers, and online entrepreneurship courses [78,79], or they may be intangible such as relationships, values, cultural traditions, and atmosphere [20]. Fourth, although terms such as dimensions [18], units [21,26], factors [72,79], levels [80], and items [22] could be found in the literature to describe the components that make up the entrepreneurship education ecosystem, the element [19,56,78] is the most common term because of its generality and compatibility. Although these case-based studies have made important contributions to the literature, the limitation is that the generalizability of the conclusions is applicable to all university-based entrepreneurial education ecosystems.

2.4. Construction Strategy of the Entrepreneurship Education Ecosystem

The relationship between theoretical research and practical application is mutually reinforcing, so it may provide suggestions and references for the practice of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem after summarizing theories and regularity in case studies. Therefore, the research on the construction strategy, or related to it, has become another important branch of the research on the entrepreneurship education ecosystem, although the number of such studies is still very limited. In addition, due to the limitation of work on the definition and scope of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem, the corresponding construction strategies also showed great dispersion.

The development of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem is an important perspective of construction strategy research. Brush [18] divided the entrepreneurship education ecosystem into domains (curricular, co-curricular, scholarship, and outreach) and dimensions (stakeholders, resources, culture, and infrastructure) in her research, and proposed a four-step construction strategy. (1) Assess: information gathering, benchmarking, discussions, and determine strengths and capabilities. (2) Engage: identify champions, develop definitions and concepts, and research groups. (3) Test ideas/experiment: pilot classes, workshops, and stakeholder events. (4) Build: courses and programs, metrics/monitoring, and practices for innovation and expansion. The entrepreneurship education ecosystem is built based on multiple universities in the industry or region is a research topic with practical significance [81]. The initial stage of the construction of the entire ecosystem was divided into three steps. (1) Develop models for ingraining entrepreneurship education into specific engineering and technology curricula and drive new course concepts into the policy action of the partnering universities. (2) Build a network for entrepreneurship education by implementing a pilot between the universities within their innovation and entrepreneurial ecosystems. (3) Share best practices for promoting hands-on entrepreneurial skills within accelerations, local hubs, technology platforms, and student-driven start-up activities.

Another kind of research on the construction strategy of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem is closely related to the composition because their starting point is the relationship between these constituent elements and the successful construction of the ecosystem. For example, Rice, Fetters and Greene [65] summarized success factors in their work as follows: (1) Senior leadership vision, engagement, and sponsorship; (2) strong programmatic and faculty leadership; (3) sustained commitment over a long period; (4) commitment of substantial financial resources; (5) commitment to continuing innovation in curriculum and programs; (6) an appropriate organizational infrastructure; and (7) commitment to building the extended enterprise and achieving critical mass. After discussing three cases of entrepreneurship education ecosystem adopted by Cornell University, the University of Rochester, and Syracuse University, Antal, et al. [82] proposed four viewpoints for success: (1) Some administrative support from parts of the university at the start; (2) a focus on entrepreneurship education and programs for students; (3) faculty champions in schools and colleges across campus; (4) emotional and financial investment of alumni. Similar studies have been carried out by Lyons and Alshibani [83], Schmidt and Molkentin [84], and Belitski and Heron [21].

The perspectives of the development process and the ecosystem composition have their own advantages in the research of the construction strategy of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem. The strategy proposed from the perspective of the development process of the ecosystem is more prominent in its guiding significance to practice, while the strategy proposed from the perspective of the composition reflects the role and importance of different elements in the ecosystem.

However, there are still many meaningful issues that could be explored and discussed urgently to enrich the comprehensiveness of the research on the sustainable construction strategy of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem. For example, there is almost no research focus on the entire process of the development of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem and revealing the characteristics of each stage at the theoretical or case study level. Similar to small enterprises in different developmental stages having different institutional settings and business models, the entrepreneurship education ecosystem in various developmental states might contain different compositions and face different situations. In addition, just as the factors and causes of entrepreneurial success were advocated and pursued at the early stage of the entrepreneurship research, the study on the success of entrepreneurship education ecosystem construction has become mainstream, while the failure factors or cases are ignored and marginalized.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

The research of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem is still in its infancy. Limited to the complexity and cost of research, this study follows the inductive approach commonly used in entrepreneurial ecosystem research. Specifically, this study used the interview method and analyzed the interview responses of stakeholders in entrepreneurship education ecosystems with qualitative analysis software, and then drew meaningful findings and conclusions for best practices.

The research was carried out in three stages: (1) The exploration stage, which included searching, sorting out, and analyzing references, defining research boundaries, focusing on research gap in the literature, and forming an interview outline; (2) The data collection stage through interviewing 30 entrepreneurship education ecosystem stakeholders selected based on the principle of purposeful sampling; (3) The data analysis stage, which involved transcribing the interview recordings into the text format and text analyses in the NVivo12 qualitative analysis software. Based on the grounded theory, the collated interview transcripts were sequentially coded with open coding, axial coding, and selective coding [85].

3.2. Sample Selection

Following the logic of qualitative research, the sampling strategy was purposeful and oriented towards achieving theoretical saturation [86]. Specifically, this study collected the contact information of participants at ten academic conferences/events of different sizes held in the US on the theme of entrepreneurship education or university-based innovation and entrepreneurship. Then, participants were asked whether they would like to take part in either in-person or video conferencing interviews of this study. Participants in these conferences were university-based entrepreneurship education ecosystem stakeholders who are familiar with, passionate, and looking forward to the improvement of the ecosystem. Based on the premise of fully respecting the interviewees’ consent and compliance with research ethics, this study comprehensively considered the distribution of factors such as gender, industry, position, work experience, and educational background. Finally, 30 positive respondents who expressed willingness to take part in our research from ten regions, nine universities or campuses, five other organizations were identified as interviewees in this study. The details of the relevant demographics of the interviewees are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Interview sample details (n = 30).

3.3. Data Collection

The interviews were conducted either in-person or remotely via video conferencing by three interview team members, which were uniformly trained on the research objectives and interview skills before the interviews started. Interviews were conducted on relatively independent occasions at scheduled times, and each interview lasted 25–40 min. The interview was semi-structured and consisted of five main questions, including (1) the key constituent elements of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem, (2) the role and (3) importance of these key elements, (4) how to build the ecosystem, and (5) the best practices for sustainability of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem the interviewees had observed. Interviewees were appropriately questioned based on their responses to fixed questions. The entire recordings of the interview were transcribed into text, which was imported into the database built by NVivo12 after clarifying the interviewees’ vague views and confirming the content.

3.4. Data Analysis

Each interview’s text data was analyzed in NVivo12. According to the grounded theory, the analysis of the interview text and the coding process was also divided into three phases [85]. Firstly, during the open coding phase, the interview text was reviewed carefully and repeatedly. The meaningful local concepts in the interview text were identified and established as free nodes. In NVivo’s process of text analysis, a node refers to a collection of references about a specific theme or case, and researchers gather the references by coding sources to a node. Secondly, in the axial coding phase, similar free nodes were classified and merged concerning the research purpose and interview outline. For example, most of the interviewees mentioned “enough places”, “gathering space”, “physical places”, “workspace”, “together space”, and “office space” when talking about the key elements of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem, so a node named “space” was established in the “elements” node directory. Then, the characteristics of different classification nodes were mined and analyzed, and the nodes were reconstructed and renamed accordingly. For example, when interviewees talked about the importance of the constituent elements of the ecosystem, almost all the local concepts that they used involved the comparison of two different elements or the comparison of one element with other elements. Therefore, the free nodes describing the importance of the constituent elements were transformed into the relationship nodes. Finally, during the selective coding phase, the classified nodes were organized into a tree-like hierarchical structure based on logic, containment, and dependencies in the node directory.

Trustworthiness is considered a more appropriate criterion for evaluating qualitative studies [87]. Therefore, three team members independently coded and compared the coding repetition rate with each other to ensure the reliability of the qualitative analysis of the interview text. To avoid errors caused by different coders using different vocabularies for the same node, the three sets of coding tables were modified and clarified before performing the reliability test. Specifically, similar words and synonyms, such as universities and colleges, teaching methods and pedagogy, financial and economic support were negotiated and unified. After such corrections, a team was set as the basic group, and the other two teams were set as the comparison group. The code comparison tool of NVivo was used to measure the repetition rate of the coding tables of the base group and the comparison group. According to the average weighting of each interview text, the comparison results were 90.75% (Cohen’s Kappa coefficient = 0.8219) and 86.31% (Cohen’s Kappa coefficient = 0.7328), which were within acceptable ranges. Table 4 presents the number of nodes at all levels of the interview text after analysis and coding.

Table 4.

Number of nodes at all levels after coding.

3.4.1. Key Elements of the Entrepreneurship Education Ecosystem

Although this study attempted to summarize the common aspects in the composition of the university-based entrepreneurship education ecosystem, almost all interviewees expressed that the key elements of the ecosystem should or could be different in various environments, stages, and situations. For example, “They (the elements) should be drawn depending on the specific situation of the university” (Interviewee #2). However, in the process of encoding and analyzing the interview text, it was found that the differences expressed by the interviewees were actually due to variations in the characterization of the same or similar elements under different conditions. Therefore, it did not affect the summary of the key elements frequently mentioned by most interviewees after clarification. For example, “entrepreneurship degrees prevalent in Australian universities” (Interviewee #5), “entrepreneurship education minor offered by many universities” (Interviewee #11), “a range of entrepreneurship education courses” (Interviewee #21) were shown in the responses of different interviewees to describe the same key elements. They are just different forms of the entrepreneurship education curriculum, so the “entrepreneurship curriculum” as a key element of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem could not be denied. Similarly, various forms of institutions were mentioned by interviewees as constituent elements of the ecosystem, including “entrepreneurship center or similar institutions are the core of the ecosystem” (Interviewee #1), “cooperation between entrepreneurship education institutions and supporting institutions is the key” (Interviewee #3), “entrepreneurship education institutions at both the university and college levels are necessary” (Interviewee #17). The interviewees were presenting what they thought would be the most ideal framework for university institutions within the entrepreneurship education ecosystem. The significance of this divergent view is that organizational structure is an important part of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem. As a result, “organizational structure” is one of the key elements in the analysis of the presentation of the characteristics of the interviewees.

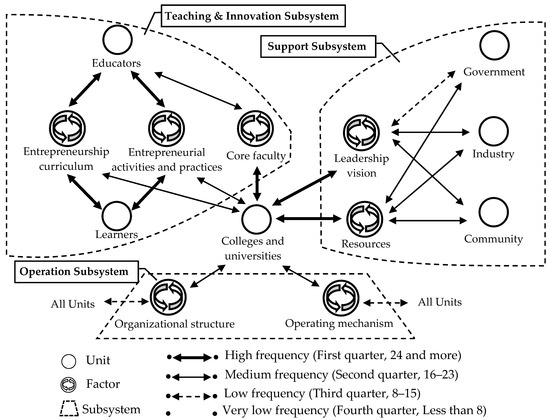

The analysis process sought common elements in the interview text but also aimed to preserve differences in the perspective of the interviewees, and these two contradictory objectives became the basis for the classification of key elements in the coding process and led to interesting revelations. Especially in the selective coding stage, the characteristics of the key elements presented two distinct classifications. One type of the key elements, encoded as units, was an institution, organization, or stakeholder group in the entrepreneurship education ecosystem, which was the source or target of behavior, resources, information, and interaction. Another type of the key elements, encoded as factors, was an intermediary that linked the units of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem together, or the conditions and environment associated with the units. Table 5 presents the results of the interview text analysis on the key elements of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem, which were composed of six units and seven factors. Among them, six units referred to colleges and universities, learners, educators, government, industry, and community. On the other hand, seven factors included entrepreneurship curriculum, entrepreneurial activities and practices, organizational structure, resources, leadership vision, core faculty, and operating mechanism. Based on this, the key elements of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem generated by NVivo Map Tool are shown in Figure 1.

Table 5.

Key elements of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem.

Figure 1.

Map of key elements of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem.

To further clarify the relations among the key elements that make up the entrepreneurship education ecosystem, Figure 2 graphically presents the relationship nodes identified from the analysis of the roles and their importance along with the key elements. In the figure, the units and factors are depicted by two types of circles that are connected by arrows of different thicknesses according to the frequency of the secondary relationship nodes. The frequency values were calculated as the number of coded relationship nodes used to describe the relations among the elements in the interview text. The relations between any two elements had a maximum frequency of 31 and a minimum frequency of 0, and the frequencies were categorized into four levels from “Very Low” to “High”, respectively represented by different types of arrows in Figure 2. The identified units and factors are grouped into three areas as the teaching and innovation, support, and operation subsystem based on their roles in the entrepreneurship education ecosystem, and the colleges and universities interconnect these main areas.

Figure 2.

The relation among the key elements of the entrepreneurial education ecosystem.

3.4.2. Development Cycles of the Entrepreneurship Education Ecosystem

Biological ecosystems are dynamic, and the entrepreneurship education ecosystem is no exception. Some terms describing dynamicity, such as time, order, stages, steps, and process were identified in the analysis of the interview text in this study. Moreover, these terms did not appear independently in a vacuum but were accompanied by the description of the characteristics of a specific period of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem. Then, these terms associated with the corresponding descriptions were coded and classified according to the similarity of the descriptions of the characteristics. As one of the analysis results of the interview text, the development cycles of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem could be divided into three stages and seven steps, which correspond to the primary and secondary nodes, respectively (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Development cycles of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem.

3.4.3. Importance and Role of the Factors in Development Cycles

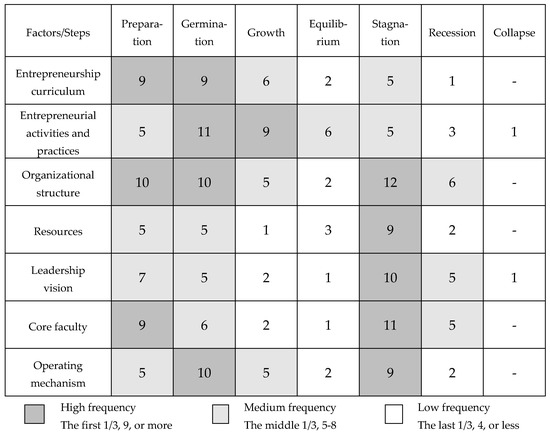

Ignoring the sudden changes to the ecosystem caused by extreme external forces, such as university mergers or natural disasters, the entrepreneurship education ecosystems are all in one of the seven steps of the development cycle found in this study. These seven steps were divided based on the characteristics and the relationships of the elements in the ecosystem. From a dialectical perspective, the elements of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem may play different roles and have varying importance in the seven steps of the development cycle. The role and importance of the unit-type elements are more intuitive (e.g., the role of educators and learners). Compared with the units, understanding the role and importance of the factor elements that link the units together is a more valuable and meaningful study [88]. Although one-third of the interviewees initially responded “equally” to the question about the importance of the factors of the ecosystem, they provided more specific answers while discussing the steps of the development cycle. Then, it was found that when interviewees described or discussed a certain step of the development cycle, some factors of the ecosystem were mentioned frequently. Moreover, the role and importance of certain factors were always associated with a specific step of the development cycle. To explore the role and importance of ecosystem factors in the different steps of the development cycles, this study used the coding tool of NVivo to conduct a cross-analysis of elements coding and development processes coding. The factors part of the secondary node of elements coding and the secondary node of development processes coding were cross-tabulated, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Cross-matrix analysis of factors and steps.

The numbers in the cross-analysis matrix are the frequency that corresponds to both the row and column encoding nodes in the interview text. Different factors have different frequencies in different steps of the development cycle. A higher frequency meant that the corresponding factors of the ecosystem are strongly related to a specific step of the cycle. This strong correlation is essentially an internal manifestation of the role and importance of the factor in a specific step, which provides an innovative research perspective for this study. Meanwhile, the frequency distribution of factors in different steps of the development cycles also exhibited certain patterns: Some factors were more frequent at the beginning steps; some factors were more frequent in the stabilization stage; the frequencies of some factors were evenly distributed throughout all steps of the development cycle. Based on the emerged patterns in the cross-analysis matrix, this study divided the factors of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem into three categories, namely: Launch factors, process factors, and maintenance factors.

4. Findings

4.1. Key Elements of Categories

The key elements of the university-based entrepreneurship education ecosystem consist of six units and seven factors, which constitute three independent functional subsystems.

4.1.1. Unit Category

In terms of the key elements of the unit category, the findings of this study were consistent with the research results of scholars on the ecosystem of entrepreneurship education. Learners and educators were mentioned as key elements repeatedly by almost all interviewees. In particular, government, industry, and community were identified as key elements. Consistent conclusions were determined by the inherent nature of entrepreneurship education [14,18,71,89] because it is not the general education of universities, but the education about entrepreneurship (Interviewee #9). Entrepreneurship education has a positive impact on innovation and entrepreneurship activities [90], which is an important driving force for economic and social development. Therefore, the government, industry, and community encouraged and invested various resources in entrepreneurship education with the expectation that entrepreneurship education could export new enterprises, new jobs, new talents, new technologies, etc. (Interviewee #19). When analyzing the composition of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem, the ecosystem must be placed in a specific context that is determined by the policies of the country and state, the needs of the industry, and the situation of the local community where the university is located (Interviewee #7). The government, industry, and community were identified as the key elements of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem because they are located in different parts of the ecosystem’s relation chain [91,92]. Simultaneously, entrepreneur teams in universities need to tap the entrepreneurship education ecosystem for capital, which always comes from outside organizations such as angel investors, companies, governments, and industries (Interviewee #26). These inputs and expected outputs of the government, industry, and community also constitute the main components of the resource and information flow in the entrepreneurship education ecosystem.

The unique finding of this study was to identify the university as an element placed in the entrepreneurship education ecosystem, rather than considering specific colleges or different academic programs. The centrality of universities to entrepreneurship education has never been challenged (Interviewee #6). However, the research perspective of the university-based entrepreneurship education ecosystem usually focuses on individual academic programs [18,21,90,93], so that the university as an element of the ecosystem is ignored by most scholars. For the ecosystem level, the internal composition of the university presents some common characteristics in terms of interests, behaviors, and value trends. This uniqueness of a university is the foundation and start point for building an entrepreneurship education ecosystem (Interviewee #15). Therefore, it is necessary to consider the university as a whole in the ecosystem, especially when exploring the relationship between the university and the government, industry, and community. In addition, any element that is considered to be an internal element of the university, such as students or faculty, may not represent the university. The boundary of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem is not the university campus, but the strength of the relationship between the candidate element and other elements of the ecosystem (Interviewee #13). In other words, whether entrepreneurship education activities occur inside or outside the university (Interviewee #1), whether the learners are current students or graduates (Interviewee #21), and whether the educator is a faculty member or part-time entrepreneur mentor (Interviewee #24) is not the criterion for identifying an element that belongs to the entrepreneurship education ecosystem. Therefore, our findings suggest considering the entire university, rather than individual academic units, as an element in the entrepreneurship education ecosystem.

4.1.2. Factor Category

The key elements in the factor category could be divided into three types according to the characteristics of the roles that they play in the entrepreneurship education ecosystem. These three types are the intermediary, the condition, and the environment, which represent the main interaction and relationship among different units. The vibrant ecosystem needs the interactions and the relationships to be mapped and managed (Interviewee #23). The factors of intermediary type mainly refer to entrepreneurship curriculum and entrepreneurial activities and practice, which connect educators and learners. The scope of entrepreneurship curriculum encompasses formal degree courses of the entrepreneurship (Interviewee #30), courses in entrepreneurship minors (Interviewee #14), entrepreneurship co-curricular (Interviewee #6), and lectures and workshops on entrepreneurship (Interviewee #11), most of which take place in the classroom. The scope of entrepreneurial activities and practices is much broader, including activities that take place outside the classroom (Interviewee #5) for teaching and improving the results of entrepreneurship, as well as technological innovation and entrepreneurship research in the form of “teaching in doing” (Interviewee #19), most of which take place in laboratories or research institutions. The main function of entrepreneurship curriculum, as well as entrepreneurial activities and practices, are to transfer entrepreneurial skills, spirit, knowledge, and information between educators and learners (Interviewee #9), so these two factors are the main channel and method of entrepreneurship education. These transmitted things may have existed in the past from knowledge and experience, or they may have been created during the transfer process (Interviewee #13), which reflects on the uniqueness of entrepreneurship education for future-oriented and practice-oriented education.

The factors of condition type mainly refer to resources, leadership vision, and core faculty. This type of factor has a profound impact on the existence and development of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem and presents the status of the causal relationship between the units. Specifically, the resources factor composes of human, material, financials, time, space, and information (Interviewee #5) and links some related units in the entrepreneurship education ecosystem. The leadership vision presents a higher education institution’s positioning, concept, and goals for entrepreneurship education, and its role is to generate cohesion (Interviewee #25) that brings other units in the entrepreneurship education ecosystem together and gives stakeholders encouragement and confidence (Interviewee #22). Core faculty refers to leaders, who are prominent figures among full-time and part-time members in the entrepreneurship education ecosystem. They were found to be closely related to the creation, development, and crisis exclusion of the ecosystem (Interviewee #14).

The factors of environment type mainly include the operating mechanism and organizational structure, which are the background and context of the elements of the ecosystem. At least half of the interviewees repeatedly mentioned the institutions and guidelines/policies, such as the entrepreneurship center, club, incubator, laboratory, management system, technology transformation, library support mechanism, and so on. Depending on whether they are tangible or not, the factors of environment type were divided into organizational structure and operating mechanism. It needs to be pointed out that both of them are most widely used to classify and even name the whole entrepreneurship education ecosystem because of their distinctive characteristics. For example, the “Triple Helix” and “Magnet-Model” frequently mentioned by interviewees originated from the description of institutions or mechanisms and have become the “brand” of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem for some universities, and they are widely spread.

4.2. Three Subsystems of Division

The teaching and innovation, support, and operation subsystems were identified by analyzing the relations among key elements of the university-based entrepreneurship education ecosystem. The teaching and innovation subsystem is the core of the ecosystem, including educators, core faculty, learners, entrepreneurship curriculum, and entrepreneurial activities/practices. The teaching and innovation subsystem relies on the process of knowledge transfer to catalyze the birth of potential entrepreneurs (Interviewee #12) and relies on universities’ capacities in research to continue to create new value through innovative technologies, business models, products, and services (Interviewee #3). The support subsystem consists primarily of leadership vision, resources, government, industry, and community, and it provides two-way, mutually beneficial support (Interviewee #5) for the other two subsystems. It emphasizes “support” rather than “input” and “output” to avoid the boundary of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem being preconceived as the campus of the university. The formation and adjustment of the Leadership vision are inextricably linked to the concept of entrepreneurship education in government, industry, and community (Interviewee #20). With a high degree of adaptation between them, the resources needed for the entrepreneurship education ecosystem are drawn from the government, industry, and community and used by other subsystems. In contrast, entrepreneurs and new technologies, business models, products, and services are also the resources to the government, industry, and community, so the working mode of the support subsystem is two-way and reciprocal. The operation subsystem is mainly composed of the organization structure and operation mechanism, the function of which is to ensure the daily operation of the entire entrepreneurship education ecosystem.

In addition, the significance and contribution of the above findings of the relation among the elements of this study also provide a new research perspective for other entrepreneurship ecosystem studies by explaining the details of phenomena and events in the entrepreneurship education ecosystem. For example, the process of an entrepreneurial student team’s obtaining start-up funds to develop their businesses within the entrepreneurship education ecosystem can be explained according to the framework of the key elements and relationships of the ecosystem discovered in this study as follows. An entrepreneurship education concept (leadership vision) of the university attracts the attention of an enterprise in an Industry. This enterprise sets up an entrepreneurship scholarship (resources) at the university to encourage students to start businesses and develop industry innovation. With the scholarship, the director (core faculty) of the university’s entrepreneurship center launches an entrepreneurship competition (entrepreneurial activities and practice) according to the responsibilities and functions of the organization (organizational structure). Under the guidance and assistance of entrepreneurship teachers (educators), students (learners) who have passed the entrepreneurship training program (entrepreneurship curriculum) form entrepreneurship teams to participate in the competition. The entrepreneurship competition selects the best teams according to the relevant rules (operating mechanisms) and awards them with some scholarships. Most of the events and phenomena similar to this example could be presented in detail in the entrepreneurship education ecosystem.

4.3. Stages of Development

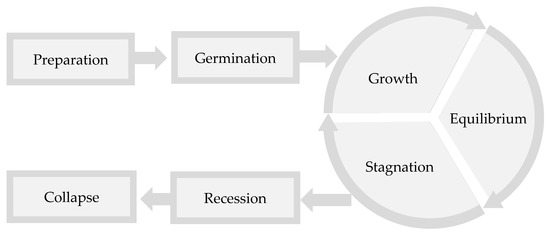

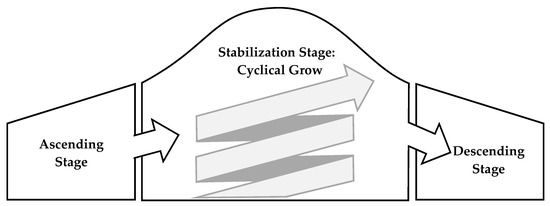

The development process of a university-based entrepreneurship education ecosystem involves three stages, which can be subdivided into seven steps.

In chronological order, the first stage was the ascending stage, including the two steps of preparation and germination. The second stage was the stabilization stage, including the three steps of growth, equilibrium, and stagnation. The last was the declining stage, including the two steps of recession and collapse. Among them, the two stages of ascending and declining were a one-way development process. However, the three steps of the stabilization stage showed typical cyclic characteristics. Based on these findings, the diagram of development cycles of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem was constructed, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Development cycles of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem.

4.3.1. Ascending Stage

For the entrepreneurship education ecosystem, the ascending stage of the development cycle is the process of establishing the ecosystem from scratch. Depending on whether the plan is put into action, this initial stage of the ecosystem development cycle can be divided into two steps: preparation and germination. In the preparation step, the development blueprint of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem is proposed, which clarifies the goals (Interviewee #2) or the development direction of the ecosystem (Interviewee #25). This development blueprint is critical to ecosystem development because it marked the difference between the entrepreneurship education ecosystem and the spontaneous entrepreneurship curriculum improvement or organizational collaboration (Interviewee #9). Therefore, the blueprint must be panoramic, systematic, and framed, and in most cases was proposed by leadership (Interviewee #16) or in line with the leadership’s vision (Interviewee #22). The uniqueness of the germination step lies in the action. However, this kind of action is limited to the development of relatively independent elements within the ecosystem, and these early-developed elements rarely have regular contacts, interactions, and information exchanges with each other. Once the elements were regularly linked by some mechanism (such as interaction, information exchange, or mutual dependence), which marked the formation of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem (Interviewee #29), and then the development of the ecosystem entered the next stage.

4.3.2. Stabilization Stage

The stabilization stage is the core stage of the development cycles of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem. Moreover, the three steps of growth, equilibrium, and stagnation are included in this core stage. These three steps represent a sustainable cyclical sequence as shown in Figure 3. In the process of the growth step, the entrepreneurship education ecosystem presents a thriving situation. Specific manifestations include: The increase of entrepreneurship courses (Interviewee #6); increased participation in entrepreneurship courses, practices, and activities (Interviewee #17); resources, including finance, were constantly enriched (Interviewee #13); normalization of multi-element cooperation (Interviewee #10); with universities as the center, ecosystem cooperation in industry and community continued to expand and strengthen (Interviewee #15), etc. On the contrary, the stagnation step indicates that the development of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem is in crisis and cannot be sustained. This unsustainable state of the ecosystem is reflected as follows: Entrepreneurship courses gradually failed to meet learners’ needs in terms of content or timeliness (Interviewee #27); resources tend to be exhausted or unable to meet the needs of ecosystem development (Interviewee #30); industry or community cooperation was inefficient, stagnant or shrinking (Interviewee #16); the institutional framework or operational mechanism was not compatible with other elements (Interviewee #24), etc. In particular, the crisis identified by the stagnation step does not refer to minor problems and contradictions that occur in the operation of the various elements of the ecosystem. For example, a case used in an entrepreneurship classroom did not receive positive feedback from learners, or occasionally the number of students choosing entrepreneurship courses has decreased. There are some minor problems and contradictions that often exist in a variety of daily teaching and ecosystem operations. The so-called crisis in the stagnation step means that the state or situation caused by an event has a greater impact on the entire entrepreneurship ecosystem. Related to a specific negative event is the distinctive feature of the stagnation step of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem development cycles. The typical examples of the stagnation step in the responses of the interviewees talking about the best practice of the ecosystem were the cases of Emlyon Business School and Babson College. The entrepreneurship education ecosystem of Emlyon Business School has experienced three crises, corresponding to the promotion of entrepreneurship education, the reform of teaching methods, and the development of inter-academic courses, which were called ‘Three Waves’ by Fayolle and Byrne [94]. Additionally, when summing the experience of the Babson College, Fetters, et al. [95] mentioned that the development of the ecosystem is both staged and wavy, and the valley represents the crisis of the ecosystem and major events. When opportunity-rich growth and challenging stagnation are in check and balance, the entrepreneurship education ecosystem is in equilibrium. The equilibrium step is a dynamic and changeable state (Interviewee #26), and its duration can be long or short (Interviewee #13). The state of most entrepreneurship education ecosystems, in reality, is in one of these three steps of the stabilization stage. Furthermore, a sustainable cycle was formed between these three steps: An entrepreneurship education ecosystem at the equilibrium step is in crisis due to unexpected events and has transitioned into the stagnation step. Then, if the internal or external forces of the ecosystem correctly respond to and resolve this crisis, the entrepreneurship education ecosystem in the stagnation step will enter the next growth step. Compared with the original state of the ecosystem, this new growth may gradually compensate for the damage or loss caused by the stagnation period, or it may progress toward a larger and healthier state based on the original. Regardless of the way of growth, the ecosystem development direction is to enter the next step of the equilibrium. As mentioned by the interviewees, the development process of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem was very similar to the development of a new enterprise (Interviewee #12). New enterprises must constantly face new business development and market challenges (Interviewee #30), and they were always in a state of opportunity and crisis (Interviewee #3). Therefore, in the stabilization stage of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem, the development process can be summarized as sustainable cyclical growth, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Sustainable cyclical growth in the development cycles of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem.

4.3.3. Descending Stage

The descending stage is the last stage of the development of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem. Interviewees rarely gave realistic examples of ecosystems in the descending stage, because successful and active ecosystems were often widely advertised rather than failed and unhealthy ones. In the context of the development process of the idealized entrepreneurship education ecosystem set in this study, interviewees gave negative responses to the development of the ecosystem that could not overcome the crisis step. Intuitively, the ecosystem is bound to go from bad to worse and to recession and collapse when its sustainability is affected. Therefore, the difficult problem facing the entrepreneurship education ecosystem in the crisis of the stagnation step is resolved as a sign, which determined whether the ecosystem continues to enter the development cycle or enters the descending stage. The two steps of recession and collapse constitute the declining stage. The recession step is characterized by the gradual shrinking or declining of elements and the reduction of interactions and information exchange between the elements in the ecosystem. For example, the departure of core faculty and staff (Interviewee #13); the decrease in the number of teachers engaged in entrepreneurship courses (Interviewee #16); insufficient resources to support the daily operation of the incubator (Interviewee #1); the cooperation program between the university and the community or industry were canceled (Interviewee #28), etc. When regular entrepreneurship education activities cannot be carried out in universities, the entrepreneurship education ecosystem enters the collapse step. The collapse step is the last one in the development process of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem, and it means the gradual end of the ecosystem.

4.4. Roles of the Factors

The factors play different functions in each stage of the development of a university-based entrepreneurship education ecosystem.

4.4.1. Launch Factors

The launch factors play a core role in the startup of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem by providing the foundation for the germination, growth, and expansion of the ecosystem. The launch factors mainly include entrepreneurship curriculum and entrepreneurial activities and practices, which could take place in or out of the classroom. Regardless of theory or practice, entrepreneurship education is at the foundation of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem. When a blueprint for building an ecosystem was planned, many factors could not be started at the same time due to the availability of resources, but entrepreneurship courses and practices were always the priority according to the interviewees. If we were asked to drop these factors one by one according to the importance, there is no doubt that the last thing left must be the entrepreneurship course in the initial stage of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem (Interviewee #11). Self-sustaining is an important feature of biological ecosystems, but it is often overlooked in other fields. Without considering self-sustaining, some researchers decomposed entrepreneurship curriculum and practices into more factors [14,18], thus forming a narrow sense of entrepreneurship education ecosystem. From a broad perspective, these studies were the best interpretations of the launch factors that play a core role in the ecosystem. The launch factors are very important in the early stage of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem, but it does not mean that they can be ignored at later stages. Downplayed or weakened launch factors in the stabilization stage may lead to stagnation of the development of the ecosystem due to unstable foundations. To be specific, in the early stage of ecosystem development, the role of the launch factors is as follows: Provision of formal entrepreneurship curriculum system (Interviewee #5); regular entrepreneurship lecture series or workshop (Interviewee #13); daily guide and assistance potential entrepreneurs or entrepreneurial team practice activities (Interviewee #20). In other development stages, the improvement and solidification of the launch factors are the abundance and variety of courses (Interviewee #19), the cutting-edge and timeliness of course content (Interviewee #7), and the personalization and diversification of practical activities (Interviewee #14). Essentially, the launch factors, which consist of entrepreneurship courses and practices, are the main way to achieve the goals of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem. Supported by the environment, conditions, and resources of the ecosystem, the launch factors realize the delivery and transformation of entrepreneurial-related knowledge through the interaction of Learners and Educators. Furthermore, the launch factors promote potential entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial teams and provide the foundation for the birth of new ideas, new solutions, and new enterprises. Therefore, metaphorically, the launch factors are the chloroplast of synthetic entrepreneurial “Organic Matter” (Interviewee #7) and the “Engine” that keeps the ecosystem alive (Interviewee #11).

4.4.2. Process Factors

The process factors are defined as factors that function continuously at various steps in the development cycle of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem, and they are primarily important to the ecosystem in a supportive manner. Resources and leadership vision constitute process factors, both of which respectively provide endless dynamics for the ecosystem at the realistic and spiritual levels. Resources from the government, industry, and community in addition to internal university resources provide the necessary human, economic, and material support in the construction and development of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem. Support and attitudes also lead to a more positive risk perception among potential entrepreneurs within the ecosystem [96]. Moreover, the availability of resources determines to some extent the length or efficiency of ecosystem construction and development. Resources are vital to the ecosystem at all times, just as water and electricity are to factories (Interviewee #8). The leadership vision works by encouraging, spurring, or motivating all human factors within the ecosystem, including teachers, students, faculty, managers, entrepreneurs, investors, and officials. Specifically, the role of the leadership vision is reflected by several interviewees: The outline of the ecosystem blueprint (Interviewee #19); the formulation of phased goals (Interviewee #30); The potential allocation of benefits and resources (Interviewee #4); the stable and sustainable development direction (Interviewee #13); the promotion of cooperation inside and outside the university (Interviewee #15); the acquisition of the sense of accomplishment and mission of faculty and staff (Interviewee #28). In addition, it has been found that the stagnation step of ecosystem development is often caused by changes in the state of process factors. Changes in resources and leadership vision are among the reasons that trigger the entrepreneurship education ecosystem to enter a crisis state, which is directly reflected in the high frequency of the corresponding data in the cross-matrix table. For example, changes in the economic situation and markets would affect the resource input of industry to the ecosystem (Interviewee #17), or the replacement of university president may lead to subversive changes in leadership vision (Interviewee #10). For sustainability, the stagnation step of the development cycle is a crossroad: if managed properly, it can make the ecosystem evolve and upgrade into the next level of the development cycle, or it can also make the ecosystem decline and shrink into the decline stage. In this regard, the process factors are the key to diagnosing problems in an ecosystem and taking measures, whether passively influenced by external factors of the ecosystem or actively initiating internal reform of the ecosystem.

4.4.3. Maintenance Factors

The maintenance factors are critical to the early stages and stagnation step of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem because their role is to get the ecosystem out of its unhealthy state and through the crisis. The maintenance factors include organizational structure, operating mechanism, and core faculty, which play the maintenance function for the ecosystem in different ways. The emergence of two high-frequency peaks in the early stages and the stagnation step of the ecosystem development cycle is the unique feature of maintenance factors through the analysis of the cross-matrix table. Organizational structure and operating mechanism are classified as environment types in the presentation of the composition of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem. However, unlike other natural environments, which are difficult to be transformed, organizational structures and operational mechanisms need to be adjusted promptly to facilitate the development of the ecosystem. Organizational structure was like tangible computer hardware, and operating mechanism is like intangible software running on a computer…both of them must be adapted to exert maximum efficiency (Interviewee #20). This adaptability is reflected in two aspects. The first is the internal matching of both the organizational structure and operating mechanism. In the face of numerous institutions and complex relationships within the ecosystem, the unclear division of responsibilities and extensive management regimes could inevitably lead to low efficiency and poor communication [79]. The other is that the organizational structure and operating mechanism match the development scale and stage of the entire entrepreneurship education ecosystem. The small-scale ecosystem in the early stage and the large-scale ecosystem in the equilibrium stage necessarily correspond to different organizational structures and operating mechanisms. Core faculty is also one of the maintenance factors, although it was not intended to be an element at the beginning of the study because it is more like a unit, essentially. The reason why core faculty members stand out from educators, leaders, administrators, or other primary and secondary nodes of coding as an independent ecosystem factor was that interviewees frequently mentioned it in the early stage and stagflation step of ecosystem development. Core faculty may be the president of a university, the administrator of an institution, the leader of a discipline, or even a socially versatile person. In addition, most of the core faculty were described by interviewees in terms of genius, talent, legend, leadership, excellence, distinction, preeminence, etc. Core faculty are the ones who can lead others to overcome difficulties and turn the situation when the entrepreneurship education ecosystem was established or in crisis. Unsurprisingly, when the interviewees listed and talked about specific cases of the development process of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem, these core faculty were one or more specific people with identified names. For example, one of the reasons for Silicon Valley’s success was the role of universities in promoting entrepreneurship and innovation. If an entrepreneurship education ecosystem was defined based on Stanford University, its early growth and expansion will undoubtedly be inseparable from his work and vision during Frederick Terman’s tenure as the dean of the School of Engineering (Interviewee #12). Another typical example is an entrepreneurship education ecosystem centered on the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), including the Route 128 Entrepreneurship Cluster. Its development process had been up and down several times, but in its development process, it is necessary to mention a legendary figure who shoulders of industry, academia, and research, Professor Robert Langer of MIT. With him at the forefront, Kendall Square had developed into an innovation-intensive area for life sciences (Interviewee #10). The development of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem is always linked to the names of a few core faculty, whether these names are known by a few or many people. Therefore, the behavior of core faculty and the adjustment of organizational structures and operating mechanisms have the same maintenance effect on the ecosystem. If the process factor is the underlying cause of the crisis of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem, then the maintenance factors may provide specific measures and key persons to resolve these crises.

5. Discussion

The growth of the university-based entrepreneurship education ecosystem could not be completed overnight. It requires a long time, resources, and continuous input from all stakeholders, as well as careful planning, continuous adjustment, and innovation in dealing with adverse situations, and may even require a little luck. The center of the university-based entrepreneurship education ecosystem is the university. Although almost all the stakeholders may contribute to the growth and development of the ecosystem from their respective roles, university administrators play an irreplaceable main role in coordinating and promoting the construction of the ecosystem due to their unique advantages in power, responsibility, and resources. Therefore, based on the analysis of the key elements of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem and the role and importance of these elements in different steps of the development cycle, the following strategies for constructing the entrepreneurship education ecosystem could be recommended for university administrators.

University administrators need to pay great attention and lay a solid foundation to accumulate, improve, and develop the identified launch factors. As the first step in building an entrepreneurship education ecosystem, the planning blueprint and specific actions begin with entrepreneurship courses and practices, whether it is entrepreneurship curriculum in the classroom or co-curricular entrepreneurial activities and practices outside the classroom. The launch factors are both the core and the foundation of the entire entrepreneurship education ecosystem. If significant progress could not be achieved in the launch factors at the early stage, these factors would inevitably restrict the development scale and lay hidden dangers for the future development of the ecosystem. Therefore, for the establishment of an idealized entrepreneurship education ecosystem, the following strategies for the launch factors are suggested. (1) The entrepreneurship curriculum, activities, and practices are taken as the first step to build an idealized entrepreneurship education ecosystem, and continuous development and improvement. (2) The development and improvement of entrepreneurship curriculum, activities, and practices should be both competency-driven and problem-driven, to ensure that the course content could meet learners’ long-term expectations for entrepreneurship education. (3) After completing the initial construction of the entrepreneurship curriculum, activities, and practices, with the expansion of entrepreneurship education ecosystem scale, it is necessary to gradually expand and enrich in quantity, level, and form. (4) The pioneering and coverage of entrepreneurship curriculum, activities, and practices should be constantly maintained to keep the vitality and attraction of entrepreneurship education for all kinds of learners. (5) Learner-centered teaching methods need to be encouraged, explored, and innovated to highlight the interactivity and practicality of entrepreneurship education.

For the process factors, university administrators need to invest, expand, and innovate continuously based on inheritance. It is a long process to build a self-sustainable entrepreneurship education ecosystem. This extensive construction process requires constantly creating educational value with resources from within and outside the university, such as the government, industry, and community. In addition, this construction process is also the process of transforming the blueprint and goals in the leadership vision from intangible to reality. The leadership vision needs to be recognized by ecosystem stakeholders at various institutions and levels within the university, and it also needs to be consistent with the values of government, industry, and community. This recognition and consensus would create synergy between the internal and external resources of the university, thereby promoting the establishment of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem. The process factors of leadership vision and resource composition could adopt the following strategies in the construction of an ideal entrepreneurship education ecosystem. (1) The senior leaders of the university need to have a deeper understanding of entrepreneurship education and have lasting enthusiasm for the establishment of an entrepreneurship education ecosystem. (2) The university leaders actively participate in the construction of the ecosystem and incline to support entrepreneurship education in resource allocation are often the prerequisite for the sustainable and stable development of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem. (3) The brain trust or advisory board for the entrepreneurship education ecosystem is proposed to be established in university to provide intellectual support for senior leadership decisions. (4) The leadership vision should maintain certain relative stability from subversive changes caused by the switch of position candidates while fine-tuning the leadership vision in response to changing circumstances and ecosystem needs to be encouraged. (5) The output of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem, which could be in the form of new business creation, innovation, and economic growth, should be maximized and publicized to ensure contentious support from governments, industries, and communities. (6) The acquisition of resources is not the sole responsibility of the leader, and faculty and staff are encouraged to seek outside resources to collectively build the entrepreneurship education ecosystem rather than to act like outsiders.