Abstract

Throughout time, the global tourism industry and economy have been significantly affected by disasters and crises. At present, COVID-19 represents one of these disasters as it has been causing a serious economic downturn with huge implications in tourism. In this review paper, we have analysed more than 100 papers regarding the effect and consequences of a pandemic on tourism and related industries, the economic situation in countries and areas, and mitigation of the loss incurred due to pandemic situations. The article (1) is based on past research on tourism and economy, (2) examines the effects of a pandemic on listed sectors and mitigation processes, and (3) suggests future research and approaches to help progress the field. We have gathered and categorised the literature reviews into several parts. In addition, we have listed the name of authors, journal names, books, websites, and relevant data.

1. Introduction

After conducting a review of the estimates, it is suggested that if at least three factors are present for the emergence of a new virus, we may call it a pandemic [1]: (1) People do not have much immunity against the virus; (2) The virus spreads from one person to another; and (3) No effective vaccine against the virus is readily available yet. Generally, the impact of tourism can be exacerbated by crisis and disaster. In particular, the effect of a pandemic on the tourism sector is not the same for all regions or countries. For example, during and after the SARS epidemic period, Thailand’s second international gateway, Phuket, suffered a decrease of 67.2% of international tourist arrival from January to June of 2005. Through a collection of information derived almost entirely from published sources and an administered questionnaire, it has been estimated that more than 500 tourism companies, employing approximately 3000 people, had collapsed during these few months with predictions of job losses [2]. Similarly, Wilder-Smith [3] through a discussion on the actions taken for international travel, pointed out that there was a downward trend of 12 million arrivals in Asia Pacific countries due to the spread of the Avian Flu epidemic. The World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC) [4] has conducted research on the economic impact of travel and tourism in about 190 countries and has estimated that more than 3 million people in the tourism and related industry have lost their jobs due to the outbreak of SARS. It was most severe in affected countries like China, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Vietnam, which resulted in losses of approximately USD 20 billion in terms of GDP. During the pandemic, there was less occupancy rate (lower than 20% of its full capacity) in the Chinese hotel industry as well [5]. The consequences of the pandemic were not just in Asia but in America as well. The cholera pandemic in Peru in 1991 cost the country more than USD 770 million due to adverse effects on tourism and food trade embargoes [6]. Gössling et al. [7] compared the impacts of COVID-19 with previous pandemics and other global crises, and explored the changes following a pandemic. The authors highlighted that tourism is particularly susceptible to the measures (such as international, regional, and local travel restrictions) imposed to deal with pandemics.

Meanwhile, the impact of preventive and control measures in Mexico before and during the 1991–2001 cholera epidemic was described in a review. Mexico experienced a paradoxical benefit during and after the cholera pandemic during 1991–2001 [8]. Surprisingly, Mexico did not experience any decrease in tourism activities during the last period. Some other researchers have tried to find some positive effects of the pandemic. Sigala’s [9] article, conducting a critical review of past and emerging literature, discussed the opportunity to consider COVID-19 as an opportunity for transformation. Brouder [10], observing the Evolutionary economic geography (EEG), saw in COVID-19 a unique opportunity for tourism from the political-institutional point of view and its total transformation.

The applicability of the contingent behaviour (CB) method was examined for analysis processes and policies of the recovery of tourism demand in Japan by Okuyama et al. [11]. In their research work, they have designed event, safety, visitor information, and price discounting policies.

After covering the related literature, we have found that there is no such systematic representation of the topic that will give a clear idea regarding the pandemic situation, the tourism sector, the economic activities, and the mitigation of losses due to the pandemic. Thus, the main objective of this study was to gather the literature reviews of the studies that indicate the effects of the pandemic on tourism, economics, and the mitigation process of the loss incurred by these various pre, during, and post-pandemic situations. Although some papers investigated about the issue of pandemic on tourism, there was no such systematised review article published in a peer-reviewed journal yet.

2. Methodology and Related Previous Work

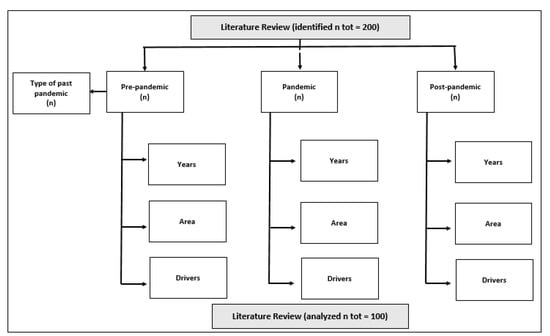

The review included past, pre, during, and post-pandemic articles with no time restrictions. This study covered a collection of bibliographic reviews for a total number of studies read equal to 100 out of a total of 200 identified. This study covers a collection of literature reviews on pre and post-pandemic effects on tourism, economics, and the mitigation process. Thus, we performed a systematic review; an organised plan was followed to select, identify, synthesise, assess, and analyse the relevant studies, as indicated in Figure 1. We analysed 100 articles because the medical and epidemiological ones were not considered within the group of 200 articles.

Figure 1.

Methodology framework. Source: Authors’ elaboration. n tot = total number of publications.

A “Consideration Set” was maintained to include all relevant articles to the reviewed topic. We collected data from five sources, mainly from electronic databases, ISI Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, EBSCOhost, and Google Scholar.

More than 25,000 peer-reviewed journals and over 5000 publishers are enlisted on SCOPUS. Approximately 1.5 billion cited and cross-cited references are on SCOPUS since 1970, which is 10–15% more than some other databases. The initial data were collected from Scopus and included 6320 results from 380 different journals. We removed duplicate journals and articles after a further screening of articles/reviews that are only related to tourism, economics, and pandemic. Additionally, we used Google Scholar to import papers. Google Scholar is well known as one of the most comprehensive internet-based article search engines and a very useful tool utilised in tourism studies [12]. In this paper, we used Google Scholar to search for Appendix A based on the Scopus dataset to improve the comprehensiveness of the data set. There is another database called EBSCOhost that contains a collection of more than 600,000 e-books, medical references, subject indexes, and a series of historical digital archives of 10,000 journal articles. Furthermore, PubMed has a collection of more than 31 million citations for biomedical literature from life science journals, MEDLINE, and online books. Few citations of our topic include full-text content from publisher websites and PubMed Central. The search words “Economic” and “Pandemic” appear in 3433 journal articles and books while “Tourism” and “Pandemic” appear in 65 contents in PubMed. We gathered only 15 papers from PubMed while searching using the “Tourism” and “Economic” and “Pandemic” keywords.

The article search was mainly based on peer-reviewed journals, chapter books, books and editorial collections, and trusted news articles. There was the exclusion of practitioner and conferences publication articles. In addition, we excluded the pre-prints of the manuscripts. The word in the search engine domain was Tourism, Economy and the Mitigation of losses caused by the pandemic. Furthermore, the collection was gathered using the terms “Tourism” & “Economic”, “Mitigation process” & “Pandemic” in the abstract and title/keywords. This particular review method led to the inclusion of more than 200 individual studies, then the reading of the full text reduced them to 100 papers, which were considered eligible. We did not consider the 100 medical and epidemiological articles. We tried to exclude the studies that were not directly linked with the main theme or the title topic, that is, which included the topics used in the search but did not match with the concept. Moreover, repeated articles, journals, or papers that we were unable to download or that were published in other languages rather than English were not counted. Non-English written articles were not selected due to the difficulties of translation and the replicability of the review process [13]. A comprehensive Excel worksheet was made to gather the most relevant data relative to the selected article papers. The following information was inserted in the database, for each study (in Appendix A): (1) Journal name, (2) Author & year, (3) Study regions, (4) Pandemic, (5) Keywords. Journal name was collected from the domains and downloaded articles. There are some collected articles without having specific keywords. The pandemic column represents the analysis and discussed pandemic situation in the article. The study region indicates the covered area/region/countries in the subject article. Usually, the author’s name is collected from the official citations exported to Endnote library software. Due to difference in Title, Keywords, Subject topic, and Year, it was not possible to maintain the chronological order in the list of gathering articles.

Literature Review

There are few systemetic review and meta-analysis research work that has been done by researchers on various pandemic and related diseases. A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis has been conducted by Jayawardena et al. [14] regarding Prevalence and trends of the diabetes epidemic in South Asia. They have urged for urgent preventive and curative strategies as there is a significant epidemic of diabetes presented in Sri Lanka and other neighboring South Asian countries. Another systematic review of seroprevalence studies regarding the Syphilis epidemic in China was done by Lin et al. [15]. From their extensive review work, they have concluded that the authority should take into consideration the preventive measures and promote safe sexual behaviour among low- and high-risk groups in China. The syphilis infection rate is not only increasing but also it may accelerate HIV transmission as well. A pandemic can create unprecedent hazards to mental health [16]. In their systematic review, the authors revealed relatively higher rates of depression, psychological disorders, post-traumatic disorders, and anxiety among general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. A systematic review and meta-analysis regarding overall the COVID-19 situation for three month were conducted by Danish et al. [17]. They have shown how the pandemic situation damaged the global economy, impacting it both from the demand and supply sides. A rapid systematic review about effectiveness of travel-related measures during early COVID-19 have been addressed by (Grépin et al. [18]. They argued that travel-related measures would play an important role to control the early transmission dynamics of the COVID-19 pandemic. They have suggested to address important evidence gaps and sort out how these evidence are incorporated in the International Health Regulations in the early phases of a pandemic outbreak. Annie et al. [19] have done another systematic review regarding the roles of transportation and transportation hubs during the coronavirus and influenza pandemics. They have concluded that influenza or coronavirus may spread faster through air transport and land transport transmissions. There is no such evidence of sea transport that may accelerate the coronavirus or influenza virus spread to new areas.

The research studies [20] on tourism risk and crisis mainly covered post-pandemic and disaster management. Haque & Haque [21] demonstrated how to untangle the impacts of swine Avian flu on the tourism industry in Brunei. Donohoe et al. [22] have gathered the related literature to identify Lyme disease risk factors and its implications on tourism management were also discussed. An extensive literature review covering the socio-economic effect of the coronavirus pandemic [23] has shown the post-pandemic effect on the national economic and social level. There is another organised review of the economic and social burden of influenza in middle- and low-income countries [24] that has covered certain economies.

An in-depth analysis by Faruk et al. [25] of the literature over the period 1989–2019, grouped 139 articles into six groups of topics to generate new research questions. Moletta et al. [26] have collected and analysed systematic reviews regarding the guidelines and recommendations for surgeons in their review article. The research by Chen et al. [27] studied 499 newspaper articles, identifying nine key themes, including the impact of COVID-19 in tourism, control of tourism activities, cultural sites, the hospitality industry’s role, government assistance and post-crisis tourism product. The authors conducted a review of 800 newspaper articles from 23 January 2020 (day of the closure of the city of Wuhan) to 28 February 2020 (date of the very high level of global risk), with an auto content analysis method, mainly related to nine key elements regarding COVID-19 and tourism. With this research, the authors invite further studies on changes in people’s perceptions during the COVID-19 pandemic, the response strategies’ effectiveness adopted for crises, and on the marketing of post-crisis tourism and related products that underline the importance of national cooperation.

A quick review of the epidemic and pandemic study on the threatening impact of COVID-19 on psychosis was studied by Brown et al. [28] but did not cover the tourism and economic effects of the pandemic. A thoughtful review and meta-analysis research study has been done by Saunders et al. [29] on the effectiveness of personal protective actions and measures in reducing influenza transmission but did not mainly focus on the mitigation process of the loss incurred by the pandemic.

Evidence-based management by Nicola et al. [30] provides a collection of guidelines that would help control and mitigate the pandemic situation which covers a part of our study research. To minimise and control the pandemic situation, Visacri et al. [31] gathered the role of the pharmacist and Harkin [32] reviewed the role of surgeons during the pandemic situation. Furthermore, Lalmuanawma et al. [33] have done a review study on applications of artificial intelligence and machine learning for the COVID-19 pandemic as a process of controlling and lessening the effects of the pandemic’s situation.

From our collected articles and sources, we have not found any organised peer-reviewed paper that has shown the effect of the pandemic on tourism and the economy. Thus, we have tried to cover and gather the articles that contain the effects of the pandemic on tourism, and the economic and mitigation process of the loss incurred by the pandemic. Our study aims to give a synopsis on the pandemic effect on economies and tourism in various countries, regions, and areas. That would also be helpful to understand the ideas of mitigation process to lessening the consequences. This paper might be helpful for students, academicians, researchers, policymakers and related personal to understand the situation and take necessary action.

3. Graphical Analysis of the Findings

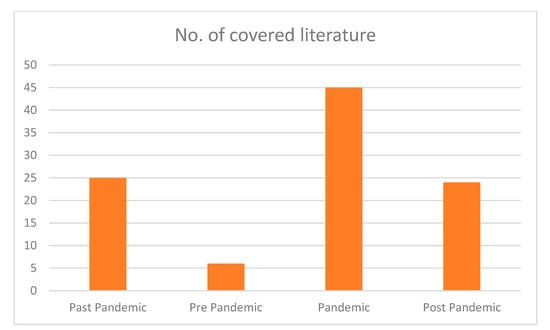

After conducting this structured review, some graphic summaries are presented to allow easier use of the study. Firstly, Figure 2 presents a subdivision of the analysed scientific literature divided into four different pandemic phases.

Figure 2.

Covered literature. Source: Author’s elaboration.

The number of studies during the pandemic situation (total number: 46) was higher than other situations, while the category of past pandemic situations (total number: 28) also has numerous research articles published in peer-reviewed journals. We analysed three studies for pre-pandemic and five for post-pandemic situations. The total number of articles that have been read is 80, of which two covered both pre- and post-pandemic situations (study number 42 in the table in the Appendix A) and study number 67 (in the table in the Appendix A) covered the pandemic and the past pandemic situation. For this reason, the total literature covered was 82. The reason could be the length of the pandemic, as it may extend up to several years. Policymaking and conceptual studies done in the post-pandemic situation also had a great contribution to mitigating the loss incurred due to different pandemics. Some precautionary research articles were published at the pre-pandemic duration. Some NGOs, WHO, and regional health schemes have conducted several pre-pandemic articles as well.

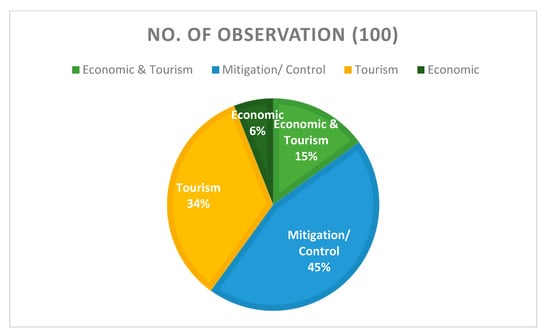

Secondly, we conducted an aggregation by macro-areas covered by the journals and the respective articles analysed as in Table 1. Most products have an orientation towards Mitigation/Control and Tourism. On the contrary, we found less orientation towards economic and economy, and tourism.

Table 1.

List of covered journal and orientation. Source: Author’s elaboration.

Table 1 and Figure 2 above show us the lists of covered journals and the orientation of the covered studies. The number of tourism and related articles were the highest (36), while mitigation and control process were 24 in number. Economic-related studies were 14, and the combination of tourism and economic studies were 6 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Contribution of total study among sectors.

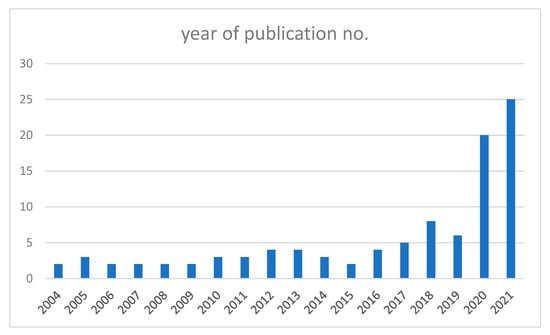

In conclusion, Figure 4 highlighted the peak of publications for the year 2020 with 41 studies published for the topics of this review, whereas, as regards the previous pandemics, the studies have been very few (from one to four publications per year). Therefore, this phenomenon of interest for research on tourism, economy, and mitigation of pandemic crisis must continue to be monitored.

Figure 4.

Number of studied articles by year of publication.

4. Direct and Related Tourism Industry Effects of Pandemics

Many developing countries are over-relying on tourism and related industries. Thus, it is very important to study tourism crisis management [34]. There is a significant negative effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the tourism and hospitality industry [35]. Nepal [36] said that the society and the communities across the globe heavily dependent on tourists, tourism, adventure tourism are particularly vulnerable as their surrounding is threatened by COVID-19. Hall et al. [37] have provided an overview of epidemics and their effects on tourism industries, government measures, and consumer response. They concluded that the selective nature of the effects of COVID-19 and the measures taken to contain it may redirect tourism and reflect the selfish nationalism of some particular countries. Jina et al. [38] investigated the factors that intensify or alleviate the negative impacts of fellow crisis events on the tours and travel industry for China. They have found that the pandemic has a negative effect on the tours and traveling industry in the case of China. Disasters due to pandemics should be managed effectively. Becken and Hughey [39] found that tourism in Northland is hardly considered in disaster management planning. A recent work in 2018 by Novelli et al. [40] analysed the effect of the Ebola virus disease epidemic (EVDE) in the African nation of Gambia, through field observations, interviews and follow-up meetings with stakeholders involved in related crisis management. The findings helped increase the debate on the direct and indirect threat of a pandemic and infectious diseases to tourism in developing countries. Their paper supported the importance of more studies on the resilience of fragile destinations in times of crisis and the need to prepare and a crisis and disaster plan for tourist destinations. There is evidence that tourism demand was significantly reduced by about 403 arrivals in Asia for an additional person probably infected by SARS [41]. The study by Cahyanto et al. [42] looked at the factors which influenced Americans to skip internal travel due to Ebola in the US in late 2014. The model of health belief and an online survey of 1613 Americans was used. The authors sought to understand traveller behaviour due to the Ebola epidemic in the United States. The results showed that most respondents considered Ebola as a serious disease and would take necessary protective measures to prevent and keep themselves safe from the outbreak. Those with a greater perception of risk are more likely to make less domestic travel, while those with higher tolerance levels have shown a lower propensity to skip travel due to Ebola. Kuo et al. [41] studied the impacts of infectious diseases (such as avian influenza and severe acute respiratory syndrome, called SARS) on the arrivals of international tourists to Asian countries. Starting from single data and panel data in a self-progressive moving average model together with a model of exogenous variables (ARMAX), the overall impact of these two diseases on Asia has been estimated. The results show that the different levels of damage associated with SARS could depend on the government’s repression and reaction strategies. De Giglio et al. [43] assessed the presence of legionella in the water networks and the distribution of cases of disease associated with tourist-recreational activities. They have shown the negative effect on tourist arrival on scenic spots due to the presence of legionella.

The present COVID-19 pandemic has hit airlines and related industries very hard. McAleer et al. [44] analysed the impacts of SARS on human deaths and on arrivals of international tourists to Asia. Direct and indirect effects of the pandemic on the airline industry seem to create an uncertainty shock. Many airline companies are lobbying for government subsidies and relief. Other airline companies are going for employee layoff, hence the unemployment rate towards related workforce would be 7–13% [45]. The main topic of Sanchez et al.’s [46] study was the vulnerability of air traffic due to external factors, which caused the cancellation of flights, aircraft landings, and travel bans. There is evidence that shows the risk of a pandemic outbreak would certainly affect the tours and tourism industries, presenting the impulse response functions (IRFs). There is a gradual deterioration in health status as health disaster risk increases. In addition, there is declining health status that led to lower tourism and generic outputs as the health status influences labour capacity and productivity [47]. There is also evidence of great changes in post-pandemic planned travel behaviours, rather than actual behaviours [48]. Sharma and Nicolau [49] analysed the expected impacts in four main tourism sub-sectors (airlines, hotels, cruise lines and rental cars) and analysed how pandemic rescue funds can be priorities in the tourism industry. Additionally, people will shorten the holiday plan during the pandemic time. The travellers may need time to decide on the holiday even after six months or a year after the pandemic is under control. This time will certainly create pressure on tourism and related fields. The airline industry might suffer the most as there is a huge fixed cost they have to count every day. It is assumable that major big airline companies will suffer most compared to the small, low budget and regional ones. The cargo flight industry should suffer too. Countries like Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia have suffered a lot in the tour and travel-related sectors and supporting industries during the current COVID-19 pandemic time [50]. An approximate loss of about USD 1.6 billion in the travel industry due to the COVID-19 pandemic from January 2020 to July 2020 was reported by the Indonesian Hotel and Restaurant Association (PHRI). The Astindo (Indonesian Travel Agent Association) has also published a report that since February 2020, there was relatively no income or very low income for the travel and tour agent industry. The loss could be even larger as there is 80% of potential passengers cancelling their trips, holiday plans, business trips, and so on.

5. Economic Effects of Pandemics

There is evidence of numerous declining visitor numbers, weakened profits, increasing unemployment, less government revenue, and reduced investment [51]. All these can often exacerbate social and economic conditions and may propel the nation into a worsened state of fragility [52]. According to Wang et al. [53], the COVID-19 crisis is affecting the emergence and development of world trade and economy and created the question for survival of businesses around the globe. The authors explored some companies in China to understand what marketing strategies they have adopted. They focused on the low and high levels of collaborative innovations and two levels of motivation (problematic search and slack search). COVID-19 has a significant effect on our daily life and that of earning sources, businesses, disrupting the global trade, interactions and movements [54]. Glover et al. [55] developed a conceptual framework to classify the negative effects that COVID-19 blockade measures have had on the population. Due to COVID-19, the economy tends to be stagnant in many countries. No matter the size of the economy, the current COVID-19 pandemic seems to have a direct effect on the economy at different levels. Assumably, there is speculation that the region with higher integration with the global economy will suffer more due to COVID-19 than the region that has lower integration [56]. Unfortunately, the current lockdown will have a direct effect on the GDP of world major economies; hence, for each month, there would be an approximate loss of +/− 2% points in annual GDP growth [57]. Bakas and Triantafyllou [58] investigated the economic uncertainty caused by global pandemics empirically by analysing the volatility of the commodity, gold, and crude oil price index. The study results showed that this uncertainty has a great impact on the volatility of the commodity and crude oil markets, while on the gold market it has a positive but less significant effect. One of the most affected countries by COVID-19, India, has suffered greatly, economically [59]. Sharif et al. [60] also analysed the nexus between oil price volatility, geopolitical risk, COVID-19, stock market, and the uncertainty of economic law and policy in the United States.

It is forecasted by IMF (International Monetary Fund) that India’s economic growth would be lowered by 1.3% to 4.8% between 2020 and 2021. The Indian statistical bureau also has published similar types of forecasts and says the GDP growth rate would follow a downward trend for India. Ashraf [61] has conducted quantitative research by using the extensive daily data for 77 countries from January 22 to 12 April 2020. He has shown the effect on the economy due to government announcements regarding social distance the study also provides a negative effect on stock market returns due to less economic activity and adverse effects. Another research shows that pandemic uncertainties have a strong negative impact on commodity markets, daily necessaries, luxury items, and the taxicab industry [58]. He and Harris [62] conducted an initial review of how the COVID-19 pandemic can affect CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) and marketing. Their result shows the negative impact of the pandemic on CSR and marketing channels.

Developed countries like the UK also suffered due to the 2008–2009 influenza pandemic. Estimated costs were approximately 5% to 1% of GDP just for illness. For low fatality situations, it is something like 3.3%, and for high fatality situations, it is 4.3% and ever-larger still for the extreme pandemic situation [63]. Correia et al. [64] have presented two main interesting insights on their research. Firstly, they found that regions that were severely affected by the 1918 Flu pandemic saw a persistent and sharp decline in real economic activities. Secondly, cities that took proper initiatives and implemented early and extensive NPIs (Non-Pharmaceutical Intervention) suffered no higher adverse economic effects in the long term. Certainly, there is a major effect of the pandemic on the United States economic uncertainty. Even though the COVID-19 risk is perceived differently over the long-run and short-run could be firstly considered as an economic crisis [65]. Given the current coronavirus crisis, business-to-business (B2B) companies have faced challenges in a complex and rapidly changing environment [66]. Akhtaruzzaman et al. [67] highlighted that listed companies, both financial and non-financial corporations, experienced a significant increase in conditional correlations between equity returns during the COVID-19 epidemic. As argued by the authors, none of the previously published papers attempted to examine the effects of COVID-19 on financial corporations versus non-financial corporations. Additionally, to analyse the impact of the crisis for COVID-19 on a company’s business model, the authors analysed eight B2B companies to outline a future overcoming strategy. Two key contributions were provided: the first, academic, highlighting on how the current coronavirus crisis is affecting business models; the second, professional, developing a process model to manage this crisis. The empirical study drew on the insights of eight companies during the COVID-19 crisis, providing some reflections on the impacts that some crises can have. According to the authors, some situations such as loss of profits can become a foundation of strength after the crisis (e.g., customer loyalty). The key point highlighted by Ritter and Pedersen [66] is the difference between facing challenges during the coronavirus crisis and facing challenges due to that crisis. In this sense, the implications for the business are significant from the pre-existing weaknesses in the business model and from the managerial inability to deal with these weaknesses before the crisis. Therefore, the authors said that without awareness of adequate preparation, business models would be at risk and, therefore, organisations will have to rethink their management approaches by providing new solutions in which to invest to deal with these risks. The effect of the pandemic on economic and daily activities was also severe in some cases. According to Pantano et al. [68], the COVID-19 pandemic is causing several short- and medium-term outages in the retail sector, too.

6. Long-Run Implications and Effect Following Pandemics

In recent months, some articles have focused on the long-term effects associated with the pandemic. Among these, Ching Goh [69] focused on the strategies proposed within the touristic industry and by the government for overcome the current crisis for a better tourism. The author also found that few studies have addressed health-related crises in developing countries such as Malaysia and even fewer studies have addressed the threat of tourism sector epidemics. Therefore, as Ching Goh [69] states, recovery will greatly depend on the availability of vaccines and the confidence to travel for holidays, as UNWTO has also indicated. Instead, according to Praveen [70], hoteliers, during the stop phase, could be used as vaccination distribution centres and designated by tour guides to coordinate vaccine groups. Thus, vaccinated people could travel without the need to quarantine and safely enter Malaysia. On the contrary, however, a series of challenges, possible solutions and ways to follow have been launched to relaunch the tourism sector in the uncertainties of Covid-19 [71]. However, the administration of the COVID-19 vaccine represents an important measure to allow tourism to recover as suggested by the World Health Organization (WHO) [72]. Unfortunately, people are still afraid of the vaccine and the safety of its side effects. These factors guide their vaccination decision [73]. However, public and private institutions have a great responsibility. Government, pharmaceutical companies, and doctors play an important role in vaccine confidence as they must emphasise efficacy and reduce concerns [74]. For this reason, [71] through a questionnaire administered, the authors found that despite the government’s focus on the tourism sector, people are still undecided about travel. The other side of the coin is that it emerged from some studies that rich countries have already secured 60% of the total supply of vaccines against COVID-19, while developing countries such as India have had to start a diplomatic campaign called “Vaccine Maitri” to provide COVID-19 vaccine doses to low-income countries in need. In particular, rich countries, which account for 16% of the world’s population, have already secured 60% of the total vaccine supplies for their citizens [75]. Among these rich countries, Canada primarily has pre-ordered enough vaccine doses to vaccinate nine times its population, while the UK has enough doses to vaccinate six times; the United States, Australia, Chile, and European Union members have pre-ordered supplies of vaccines beyond their national needs [76]. Despite everything, during the COVID-19 crisis, a number of measures were taken to limit travel and social activities outside the home. These measures have had a great impact on travel and modes of transport. of travel. Some authors have investigated the differences in individual travel behaviours during and after the COVID-19 pandemic in the city of Huzhou. Following some semi-structured interviews to examine the influence of COVID-19 on travel behaviour and perceptions of different groups, the results indicated that the travel demand was significantly reduced, the decrease in travel reduced the participation in different activities, and the duration of the impacts varied from person to person. However, a positive effect was recorded by investments related to COVID-19 in the field of medical research amounting to CNY 116.9 billion. These funds have been used for vaccine research, medical supplies, drug reserves, hospital construction and other aspects related to the prevention and treatment of pandemics [77]. Some authors have also studied how some airlines struggling with falling demand during the COVID-19 pandemic are promoting the adoption of Sustainable Aviation Fuel during this difficult time to experience a more sustainable recovery [78]. Other authors, on the other hand, have analysed how the eating habits of consumers in Russia have changed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Through an online survey, the potential problems and opportunities that this could entail for the Russian food system were analysed. The results revealed consumers have reduced the number of shopping trips and shopping more with each trip to minimise shop visits; stocks of non-perishable food products have been increased; healthier diets have been adopted; increase in culinary skills and a decrease in food waste have been observed [79]. According to Corazza and Musso [80] as the virus continues to spread around the world and mass vaccinations are in place, transport policymakers need to analyse the changing mobility and seek alternative solutions. Another problem is that during the autumn 2020 lockdown, restaurants were again forced to limit their opening hours, and many closed permanently. This led to the abandonment of the external areas with consequent long-term economic damage for the municipality, due to the lack of revenue from parking rates and from public land rents. Finally, some authors [81] focused on some differences between the post-pandemic effects. For example, a global safety agenda was established following the H1N1 flu. After Ebola in 2014, world leaders convened at the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting in Davos. COVID-19 faced urgent implementation issues and the scope of vaccination programs around the world for make sure no programs are left behind. An Asian countertrend, instead, was highlighted by Thrombe and Agarwal [82]: the impact of COVID-19 on the travel behaviour and mobility patterns of individuals was assessed by conducting a web survey in the urban agglomerations of India. The findings indicated an increase in the Pan-Indian level of car addiction following the COVID-19 crisis.

In conclusion, on the other hand, the results recorded by Ghanbari [83] through a clinical study were positive: people with a weak immune system recorded an important improvement rate through adequate medical incentives to prevent the widespread and unbridled epidemic of the second wave of COVID-19. For this reason, providing information on the safety and efficacy of new COVID-19 vaccines would positively increase the vaccine rush [84]. Indeed, the global vaccination process is crucial for the reboot of the mass tourism industry. In fact, the voluntary participation of people is required to reduce the health risks of guests, visitors, and staff [85]. However, while immunisation is highly effective for public health, even more efforts are needed to improve currently suboptimal rates of vaccination against various diseases among adults who may be at risk due to their age, medical condition or occupation [86]. The doubt about COVID-19 vaccination arises because they are new brands of consumer health technology introduced into the market. Hence, consumer behaviour approaches are critical to reduce the risk of vaccine hesitation, greater transparency, effective messaging, trust, and fair distribution [87]. However, the study by Gursoy et al. [88] found that over 70% of US respondents are willing to be vaccinated with a COVID-19 vaccine to improve living conditions.

7. Control and Mitigation of the Loss from Pandemics

From a review of the recent crisis recovery processes conducted by Ioanniddes and Gyimóthy [89], it emerged that the tourism sector could recover from this sudden market shock for government interventions. Studies with mixed methods that combine quantitative analyses with strong qualitative observations are hoped to be an interesting solution. Other authors [90] presented six examples of what a pandemic research program might look like to predict a new paradigm. They suggested that the pandemic stressed that tourism must be understood in the wider global economic and political context. The paper presented by Bruinen de Bruin et al. [91] made an explanation of risk mitigation methods persuaded by countries around the globe facing the present COVID-19 pandemic. The authors have gathered risk mitigation measures taken globally to contain and, since March 2020, to lessen the spread of the virus. The authors stressed, however, that at the time of drafting, it was still too early to express quantitative efficacy at every mitigation cluster. This article is based on the study of national literature, the media and information channels, considering the current pandemic. The authors have collected and grouped the risk mitigation measures adopted first worldwide in an attempt to contain and lessen the risks of COVID-19 by controlling the spread of the virus. The aim was to make a collection of mitigation measures available globally and to highlight the importance of sharing information between countries and sectors to improve risk governance. From a conceptual point of view, this document provided a collection of the various risk mitigation measures adopted around using a harmonisation of the taxonomic approach. Kassa et al. [92] analysed a mathematical model for the transmission of the COVID-19 disease. Therefore, in the absence of vaccination, countries should detect and sent to isolation at least 35% of the asymptomatic infectious patients and isolate at least 50% of symptomatic groups to control disease progression. Using the mathematical model, the decision-makers should estimate the risk and try to predict the spread of the virus among the citizens. Generally speaking, the combination of a mathematical model and infection disease rate would identify some common background that might help to create a model and system to understand and mitigate the loss. To some extent, COVID-19 has a similar pattern of spreading with that of SARS. Thus, the indirect transmission through the environment, individual’s behaviour in the society, popular events, and visits to historical places has to be taken into consideration.

Starting from the large-scale simulation of the flu pandemic conducted by the Ministry of Health of Indonesia, in collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2017, multi-sectorial capacity in response to the pandemic in Indonesia [93] assessed the strengths and weaknesses of the International Health Regulations (IHR). To provide useful information for planning actions against future pandemics, Panovska-Griffiths et al. [94] investigated the effects of using vaccination programs and the absence of anti-viral drugs. Using existing literature and some discussions with policymakers in the UK, four past flu pandemics have been analysed. In all the circumstances considered, the vaccination was more advantageous if it started on time and covered as many people as possible. The authors recommend future planning with the use of timely (i.e., previously purchased) vaccines against emerging flu pandemics. Marczinski [95] analysed the effects of vaccination following a flu pandemic. He conducted a study analysing the perceptions of H1N1 vaccines and stated the need to better analyse the psychological characteristics of patients to plan an effective vaccination campaign.

Many possible interventions and precautions have the potential to mitigate the potential effect that occurs due to the pandemic, but still, there is no single magic bullet that can be very effective under any circumstances [96]. No doubt the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed insufficiency of knowledge of epidemic responses and preparedness for any individual nation. The authors [97] highlighted that existing digital inequalities have been amplified with the COVID-19 crisis. They conclude that a series of community and political actions and interventions are necessary to consolidate community safeness to support the vulnerable people and to prevent the inequalities existing in public health. Gallego and Font [98] used a Big Data-based methodology from which timely and essential granular data are derived in highly volatile situations, such as the COVID-19 crisis. In addition, patient reporting and tracking regularly of flu, influenza, and other respiratory diseases globally could be used as a useful tool for creating fundamental respiratory disease information guidelines and monitoring for signals of a future epidemic or other events of international importance [99]. Crick and Crick [100] also highlighted the heterogeneity of cooperation strategies that industries can use in the time of global crisis and, therefore, the need for closely related professionals to balance the benefits and risks of coopetition activities. Thus, more research and a globally integrated process are necessary to mitigate and lessen the outbreak next time. Within the time frame, the development of national and international effective communication channels and response protocols will certainly allow integrated global action [101]. In addition, dynamic models and tools establishment can ensure that the world is better prepared for a future pandemic. China has learned a lesson from the previous H1N1 pandemic that science and technology can play a vital role to control the spread of the virus and mitigate the loss that might occur due to the pandemic and related issues [102]. Apart from that, veterinarians also can play a great role in infectious diseases like SARS, COVID-19, and so on, as these diseases are quite familiar to veterinarians for a long time [103]. The experience they (veterinarians) have gained while dealing with the community health system such as controlling and characterisation of earlier health issues of poultry and livestock including avian flu, foot, bluetongue and mouth diseases, are responsible for huge social and economic losses, is no doubt of great help to lessen the impact of the world crisis.

8. Summary and Future Research Scope

Countries relying on the tourism and travel industry have suffered the most from the surge in COVID-19 cases worldwide. Vaccine tourism is a necessity to rebuild the scope of tourism and the creative economy. Countries like Thailand and Indonesia are trying to introduce vaccine tourism to rejuvenate their economy, and the repercussions are yet to be unveiled [104]. Domestic tourism (75% of the tourism economy in OECD countries) could be another vital source to recover the entire tourism sector. Inland local tourism offers the chance for driving recovery, particularly in regions, cities, and countries where the sector supports many jobs and businesses. Proper planning, coordination, and early preparedness against the response of COVID-19, SARS, and any other related respiratory diseases should provide a unique opportunity to build and implement a worldwide effective system. This system should be helpful for sustainability and surveillance to meet global, regional, and local needs. Introducing tax incentives for the infected sectors, SMEs, and individuals would certainly mitigate the economic and social loss that have occurred due to the pandemic. It is suggested to strengthen the resilience of the related economic sector as well. Insurance coverage for the unemployed, health coverage, social security, supporting business securities, and funds to prevent job losses are also very important to run the economic activities and mitigate the loss. Some studies recommend that there should exist palliative measures taking place for all and this will help to reduce the economic difficulties and hardship as a result of this pandemic [105].

Future study scope could focus on theoretical and conceptual model building, creating more public awareness policies to mitigate to control and lessening the loss, more advanced technological involvement to identify the infected and hotspots areas, contact traces, invention of the vaccine, testing and refinement by related empirical studies. Models from other related disciplines to explore parts of macro- and micro-level models could be adopted or used for future study as well. Linking up the greater micro- to the macro-level focus of study may be helped by meso-level theories. It could be necessary to provide more focus on concepts that have relation and implications across parts of the tourism sector and related industries’ involvement.

Benjamin et al. [106] say that resilient post-pandemic tourism must be fair and fair in terms of stakeholders; research, however, must publicly involve the travel industry. The author Crossley [107] explored the relationship between the COVID-19 epidemic and the climate change movement. More research and analysis are needed related to tourism, the behaviour of medical tourists, the rationale for travel, the economic and social impact of medical tourism, the role of middlemen and intermediaries, the place of medical and related tourism within tourism (linkages with hotels, airlines, travel agents), and ethical and moral concerns and global health restructuring [108]. Even until now, there is still significant scope of scientific evidence of the way how influenza viruses are transmitted. Thus, there is a scope of future studies to understand the basic transmission way or patterns of influenza viruses and their effective mitigation process [96]. As suggested, it is also possible to have further research study on the long-term effect of a public health crisis on the travel and tourism industry. Moreover, the longer-term effect and implication on destination competitiveness tourism should be revealed [109].

Many major regional powers like South Africa and India enjoy the benefits of medical tourism from neighbouring countries. Due to some reason like the coronavirus outbreak, or being cheated by middlemen, access to these benefits may be hampered. There should be extensive research to find out the underlying reasons. The danger for ‘disenfranchised’ medical tourists from nearby countries of South Africa is that some sort of xenophobia about South Africa may increase exclusion and denial of treatment. Along with other related tourism, medical tourism, epidemic prevention method, the effect of the pandemic on South Africa’s medical tourism requires further research [110]. Celebrities, ministers, medics, academics, and others have been writing and tweeting “Stay Home” and “flatten the curve” in Saudi Arabia [111], but still, the country is suffering from many new infected people. There should be research on social media’s impact to flatten the curve and controlling the outbreak. Finally, researchers have to continue focusing on these issues to provide useful tools to public and private stakeholders planning post-pandemic crisis models and solutions. In conclusion, global vaccination coverage can only be achieved by ensuring equal access to COVID-19 vaccines [75].

Author Contributions

A.P., methodology, writing—original draft preparation, and validation; T.C., data curation, visualization, and resources; M.A.B., writing—review and editing; H.A., visualization and supervision by H.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

There was no funding for this research study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank all of our co-authors who has been put a great effort to finish this work. We would like to thank Liu Jun and Zhang Qiannan to help us for this project. All the help from the library personnel of GDUFE was really appreciable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. List of Covered Journals and Main Information

| No. | Journal Name | Author and Year | Study Region | Pandemic | Keywords |

| 1 | Journal of Infection and Chemotherapy | (Yoshimura et al., 2017) | Japan | Influenza | Travel Japan, Infectious Diseas |

| 2 | Tourism Management | (Okuyama, 2018) | Kyoto, Japan | Bird flu | Natural Disaster, Tourism Demand, Recovery Process, Contingent Behavior Method |

| 3 | One Health | (Lorusso et al., 2020) | Italy | COVID, SARS | SARS-Cov-2, COVID-19, Molecular Characterization, Next Generation Sequencing, Mutations Variants, One Health, Veterinarian |

| 4 | Mathematics and Computers in Simulation | (Lim, McAleer, & Min, 2009) | Japan, Taiwan | Pre-pandemic | International Tourism Demand; ARMAX Modelling; Income Elasticity; New Zealand; Taiwan |

| 5 | Tourism Management | (Kuo, Chen, Tseng, Ju, & Huang, 2008) | Asian countries | Avian flu, influenza, SARS | SARS; Avian Flu; International Travel; ARMAX; Dynamic Panel Model |

| 6 | Disease a month | (McFee, 2007) | World | Spanish flu | Not Found |

| 7 | Public Health | (Briand, Mounts, & Chamberland, 2011) | Global | CoVs | Surveillance, Influenza, Pandemic, H1n1 |

| 8 | International Journal of Infectious Diseases | (Sepulveda, Valdespino, & Garcia-Garcia, 2006) | Mexico | Cholera | Cholera, Control Program, Mexico, Vibrio Cholerae |

| 9 | Tourism Management | (Connell, 2013) | Global, Thailand | Pandemic | Medical Tourism, Medical Travel, Procedures, Typology, Diaspora, Tourist Numbers, Marketing, Multinationals |

| 10 | Annals of Tourism Research | (Yang, Zhang, & Chen, 2020) | Wuhan | Pandemic | Not Found |

| 11 | Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives | (Sobieralski, 2020) | Global | COVID-19 | Airline Labor, COVID-19, Recessions, Uncertainty, Unemployment |

| 12 | Science of the Total Environment | (Chakraborty & Maity, 2020) | Global | COVID-19 | COVID-19, Pandemics, Global Health, Economic, Prevention |

| 13 | Annals of Tourism Research | (Li, Nguyen, & Coca-Stefaniak, 2020) | China | COVID-19 | Not Found |

| 14 | Journal of Clinical Epidemiology | Glover et al., 2020 | World | COVID-19 | COVID-19; Equity; Inequity; Adverse effects; Public health; Impact assessment |

| 15 | Tourism Management | (Perles et al., 2017) | Spain | Pandemic | Economic Crisis, Destination Competitiveness, Permanent Shocks, Economic Transmission Mechanisms, Switching Regression Models |

| 16 | Health Policy | (Keogh-Brown & Smith, 2008) | World | Influenza | Macro-Economics; Cost; Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Virus |

| 17 | Social Science & Medicine | (Crush & Chikanda, 2015) | South-Africa | In general | Migration, Medical Tourism, South Africa, Transnational Healthcare |

| 18 | Journal of Business Research | (Pantano et al., 2020) | In General | COVID-19 | Retailing; Consumer behavior; COVID-19; Emergency; Retail strategy; Pandemic |

| 19 | Journal of infection | (Aitken, Chin, Liew, & Ofori-Asenso, 2020) | World | COVID-19 | Not Found |

| 20 | Public Health | (Liang et al., 2012) | China | H1N1 | Response, Pandemic (H1n1) 2009, China, Lessons |

| 21 | Journal of Infection and Public Health | (Algaissi et al., 2020) | Saudi Arabia | MERS | Saudi Arabia, COVID-19, MERS-Cov, Control Measures, Travel Restrictions |

| 22 | Japanese society of came therapy | (Oshitani, 2006) | Hongkong | H1N1 | Influenza, Pandemic, Mitigating Strategy |

| 23 | International journal of Tourism Research | (Henderson & Ng, 2004) | Asian Countries | SARS | Not Found |

| 24 | Book: Tourism Crises | (Henderson, 2007) | World | Pandemic | Book |

| 25 | Annals of Tourism Research | (Novelli, Morgan, & Nibigira, 2012) | Burundi | Post-conflict | Post-Conflict, Societies Rapid, Situation Analysis, Hopeful Tourism, Fragile States, Africa, Burundi |

| 26 | Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing | (De Sausmarez, 2004) | Malaysia | Asian crisis | Tourism, Malaysia, Asian Financial Crisis, Crisis Management, Private Sector |

| 27 | Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome | (Gopalan, Misra, Research, & Reviews, 2020) | India | COVID-19 | Not Found |

| 28 | Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance | (Ashraf, 2020) | World | COVID-19 | COVID-19, Coronavirus, SARS-Cov-2, Pandemic, Stock Market Government Interventions, Social Distancing |

| 29 | Economics Letters | (Bakas & Triantafyllou, 2020) | World | COVID-19 | Commodity Markets, Economic Uncertainty, Volatility |

| 30 | The BMJ | (Smith, Keogh-Brown, Barnett, & Tait, 2009 | UK | Influenza | Not Found |

| 31 | Public Health Emergency Collection | (Haleem, Javaid, & Vaishya, 2020) | General | COVID-19 | Not Found |

| 32 | The Economic Historian | (Correia, 2020) | U.S. | Spanish Flu | Not Found |

| 33 | SSRN | (Sharif, Aloui, Yarovaya, & Approach, 2020) | U.S. | COVID-19 | Not Found |

| 34 | Book: centre of policy studies | (Verikios et al., 2011) | World | Influenza | Book |

| 35 | Journal of Infection and Chemotherapy | (Yoshimura et al., 2017) | Japan | Influenza | Not Found |

| 36 | IJALBS | (Abodunrin et al., 2020) | worldwide | Pandemic | Coronavirus, Pandemic, Global Economy, Economy;COVID-19 |

| 37 | One Health | (Lorusso et al., 2020) | Italy | COVID, SARS | SARS-Cov-2, COVID-19, Molecular Characterization, Next Generation Sequencing, Mutations Variants, One Health, Veterinarian |

| 38 | Environmental Research | (De Giglio et al., 2019) | Italy | Pandemic | not found |

| 39 | International Journal of Surgery | (Moletta et al., 2020) | Global | COVID-19 | COVID-19, Surgery, Pandemic Emergency, Operatory room, Aerosol generating procedures |

| 40 | Journal of Business Research | (He & Harris, 2020) | Uk | Pandemic | COVID-19; Corporate Social Responsibility; Marketing; Consumer Ethical Decision Making; Marketing Philosophy; Business Ethics |

| 41 | Journal of Business Research | (Sigala, 2020) | World | Post-COVID | Tourism; COVID-19; Impacts; Recovery; Resilience; Crisis |

| 42 | International Journal of Hospitality Management | (Aladaga et al., 2020) | World | Pre And Post-Pandemic | Strategy Implementation, Hospitality, Tourism, Strategic Management, Systematic Literature Review |

| 43 | Journal of Transport Geography | (Suau Sanchez et al., 2020) | China/World | Pandemic | Not Found |

| 44 | Industrial Marketing Management | (Ritter, Pedersen, 2020) | World | Pandemic | Business Model, Value Proposition, Customer, Capability, Crisis, Impact Type |

| 45 | Computer in Human Behaviour | (Beaunoyer et al., 2020) | Spain/World | Pandemic | Coronavirus, COVID-19, Digital Inequalities, Pandemic, Vulnerable Population |

| 46 | Safety Science | (McCourta, et al., 2020) | World | Post Pandemic | COVID-19, Risk Mitigation Measures, Corona Virus, Public Health, Mitigation Impact, SARS-Cov-2 |

| 47 | Chaos, Solitons and Fractals | (Semu et al., 2020) | World | Post Pandemic | COVID-19 Epidemiological Model Self-Protection Disease Threshold Backward Bifurcation Sensitivity Analysis Mitigation Strategy |

| 48 | Journal of Business Research | (Yonggui Wang et al., 2020) | China | COVID-19 | COVID-19, Crisis, Firms In China, Typology Marketing Innovation Strategies, Dynamic Capabilities, Resource Dependence |

| 49 | International Journal of Surgery | (Maria et al., 2020) | UK | COVID-19, SARS | Economy, Economic Impact, COVID-19, SARS-Cov-2, Coronavirus |

| 50 | Industrial Marketing Management | (James M. Crick, Dave Crick, 2020) | UK | Pandemic | Coopetition, Coronavirus, COVID-19, Business-To-Business Marketing, |

| 51 | Finance Research Letter | (Md Akhtaruzzamana, Sabri Boubakerb, Ahmet Sensoy, 2020) | World | COVID-19 | COVID–19 Financial Contagion, Spillover Index, Financial Firms, Nonfinancial Firms, Hedge Ratios |

| 52 | International Review of Financial Analysis | (Arshian Sharifa, Chaker Alouib, Larisa Yarovayac, 2020) | USA | COVID-19 Pandemic | COVID-19, Economic Policy Uncertainty, Geopolitical Risk, Stock Market, Oil Prices, Wavelet, Causality |

| 53 | Tourism Management | (Jina et al., 2019) | East Asia | Pre-Pandemic | Crisis event, Recovery, Chinese outbound tourism, Japan, South Korea |

| 54 | Journal of Business Research | (Eleonora et al., 2020) | World | Pandemic | Retailing, Consumer behavior, COVID-19, Emergency, Retail strategy, Pandemic |

| 55 | Current issue in Tourism | (Chen, Huang & Li, 2020) | China | COVID-19 | Tourism crisis; COVID-19; news coverage; content analysis; Gephi |

| 56 | Tourism Geographies | (Brouder, 2020) | World | COVID-19 | COVID-19; evolutionary economic geography; path dependence; pathways; reset; tourism; transformation |

| 57 | Journal of Sustainable Tourism | (Gössling, Scott & Hall, 2020) | World | COVID-19 | Global change; COVID-19; pandemic; crisis; travel restrictions; tourism demand; resilience |

| 58 | Journal of Sustainable Tourism | (Gallego & Font, 2020) | World | COVID-19 | COVID-19; tourism; risk; Big Data; forecast; impact |

| 59 | Annals of Tourism Research | (Novelli et al., 2018) | Gambia | Ebola | Ebola, Tourism crisis, The Gambia, Perception, Preparedness, Recovery |

| 60 | Tourism Management Perspectives | (Cahyanto et al., 2016) | USA | Ebola | Ebola, Health Belief Model, Travel avoidance, United States |

| 61 | Tourism Management | (Hsiao et al., 2008) | Asia | SARS | SARS; Avian Flu; International travel; ARMAX; Dynamic panel model |

| 62 | Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management | (Tariq H. Haque, M. Ohidul Haque, 2018) | Brunei | Swine flu | Swine flu, Global financial crisis, Tourism, ARIMA and intervention time series analysis, models, Forecasting, Economy |

| 63 | Tourism Management | (Donohoe et al., 2015) | USA | Lyme disease | Health risk, Infectious disease, Lyme disease Ticks |

| 64 | Environmental Research | (Osvalda, et al., 2019) | Southern of Italy | Legionella | Legionella, Geostatistical analysis, Climate, Touristic facilities |

| 65 | Environmental Modelling and Software | (Michael et al., 2010) | Asia | Sars and Avian Flu | SARS, Avian Flu, International tourism, Static fixed effects model, Dynamic panel, Data model |

| 66 | Journal of Infection and Public Health | (Wignjadiputro et al., 2020) | Indonesia | Flu pandemic | Influenza, Pandemic preparedness, Simulation exercise, Indonesia |

| 67 | Journal of Theoretical Biology | (Panovska-Griffiths et al., 2019) | General/World | Influenza Pandemic | Pandemic influenza Epidemiological modelling Net-present value of pandemic immunisation Pre-purchase pandemic vaccine Responsive-purchase pandemic vaccine |

| 68 | Tourism Management | (Zenker & Kock, 2020) | General/World | Pandemic | Crises Disasters Coronavirus Covid 19 Pandemic Research Agenda |

| 69 | Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics | (Marczinski, 2012) | USA | Flu pandemic | influenza, pandemic, perceptions, pH1N1, vaccination |

| 70 | Tourism Geographies | (Benjamin et al., 2020) | USA | Pandemic | COVID-19, post-pandemic tourism, social equity, RESET |

| 71 | Tourism Geographies | (Ioannides & Szilvia Gyimóthy, 2020) | World | Pandemic | COVID-19, pandemics, mobility, resilience, sustainable tourism, immobility |

| 72 | Current Issues in Tourism | (Seyitoğlu and Stanislav, 2020) | World | Pandemic | Service robots, social robots, physical distancing, social connectedness, physically and socially distant service, COVID-19 |

| 73 | Tourism Geographies | (Hall et al., 2020) | World | Pandemic | COVID-19, disaster recovery, sustainable tourism, disaster management, pandemic impact, pandemic response, crisis management, resilience, tourism policy, third-order change |

| 74 | Tourism Geographies | (Crossley, 2020) | World | Pandemic | Hopeful tourism, social media, environment, climate change, pandemic, wildlife, grief |

| 75 | Annals of Tourism Research | (Sharma & Nicolau, 2020) | USA | COVID-19 | Not Found |

| 76 | Chaos, Solitons & Fractals | (Kassa et al., 2020) | Worldwide | COVID-19 | COVID-19, Epidemiological model, Self-protection, Disease threshold |

| 77 | Annals of Tourism Research | (Ritchne & Jiong, 2019) | worldwide | Crisis | Risk, Crisis management, Disaster management, Resilience |

| 78 | Vaccine | (Fransisco et al., 2015) | Low-middle income | Influenza | Systematic review, Influenza, Cost, Broader economic impact |

| 79 | Schizophrenia Research | (Brown et al., 2020) | Worldwide | COVID-19 | Psychosis, Schizophrenia, Pandemic, Epidemic, SARS, MERS, COVID-19 |

| 80 | Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy | (Visacri et al.,2020) | Worldwide | COVID-19 | COVID-19, Pharmacists, Pharmaceutical services, Review |

| 81 | The star | (Praveen, A. 2021) | Malaysia | COVID-19 | Not found |

| 82 | Research in Globalization | (Ching Goh, Hong. 2021) | Malaysia | COVID-19 | High-value tourism, Mass tourism, Sustainable tourism, Pandemic, Sabah |

| 83 | Journal of Destination Marketing & Management | (Dash, S.B., Sharma, P. 2021) | India | COVID-19 | COVID-19, Policy, Tourism industries, Tourism revival, India, Pandemic |

| 84 | World Health Organization (2021) | WHO author | Worldwide | COVID-19 | Not found |

| 85 | Frontline. (2021 | Desk Author | India | COVID-19 | Not Found |

| 86 | NDTV. (2021) | Desk Reporter | India | COVID-19 | Not Found |

| 87 | Archives of Medical Research | (Sharun, K., Dhama, K. 2021) | Global | COVID-19 | COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Vaccine diplomacy, Vaccination coverage, Vaccine |

| 88 | Blog, 2021 | Dhar B. | India | COVID-19 | Not Found |

| 89 | Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives | Yang, Y. et al. | Global | COVID-19 | COVID-19,Well-being, Social equity, Travel behaviour Transport and health, Transport planning |

| 90 | Energy Research & Social Science, | Santos, K., Delina, L. (2021) | Global | COVID-19 | Sustainable aviation fuel, Airline emissions, Biofuels, Covid-19, Economic stimulus, Energy transition |

| 91 | Appetite | (Hassen, T.B. et al., 2021) | Russia | COVID-19 | COVID-19, Coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, Eating behavior, Diet, Food purchases, Food waste, Russia |

| 92 | Transport Policy, | (Corazza, M.V. et al., 2021) | Global | Pandemic | Pandemic, Mobility, Transit, Emergency, Lockdown, New normal |

| 93 | EClinicalMedicine | (Hotez et al., 2021) | Global | COVID-19 | COVID-19, Health equity, Vaccine distribution, therapeutics |

| 94 | Transport Policy | (Thombre, A. et al., 2021) | Global | COVID-19 | Not Found |

| 95 | Chaos solitons & Fractals | (Ghanbari, B. 2020) | Iran | COVID-19 | Not Found |

| 96 | British Journal Of Health Psychology | (Davis, C.J., Golding, M., McKay, R, 2021) | U.K. | COVID-19 | Vaccine, COVID-19, Efficiency information |

| 97 | Current Issues in Tourism | (Williams, N.L. et al., 2021) | Global | COVID-19 | Not Found |

| 98 | European Journal Of Internal Medicine | (Esposito, S., Durando, P., Bosis, S., Ansaldi, F., 2021) | Global | Pandemic | Adults; Infectious diseases; Prevention; The elderly; Vaccination; Vaccine. |

| 99 | National Library of Medicine | (Mojagi, M. 2021) | Global | COVID-19 | COVID-19; COVID-19 Vaccine; Health Communication; Marketing; Public Health; Vaccine. |

| 100 | The service Industries Journal | (Gursoy, D. et al., 2021) | Global | COVID-19 | vaccine hesitancytravel anxietyhospitalitytourismtravelers |

References

- McFee, R.B. Avian influenza: The next pandemic? Dis. Mon. 2007, 53, 348–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.C. Corporate social responsibility and tourism: Hotel companies in Phuket, Thailand, after the Indian Ocean tsunami. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 26, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilder-Smith, A. The severe acute respiratory syndrome: Impact on travel and tourism. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2006, 4, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WTTC. Special SARS Analysis: Impact of Travel and Tourism (Hong Kong, C., Singapore and Vietnam Reports); World Travel and Tourism Council: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Terence, B. Hotel News Now. 2020. Available online: http://hotelnewsnow.com/Articles/300132/Chinese-hotels-seeing-steepdeclines-from-coronavirus (accessed on 5 February 2020).

- WHO Global Task Force on Cholera Control. Cholera Outbreak: Assessing the Outbreak Response and Improving Preparedness. World Health Organization, 2004; Volume 4. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43017 (accessed on 5 February 2020).

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepulveda, J.; Valdespino, J.L.; Garcia-Garcia, L. Cholera in Mexico: The paradoxical benefits of the last pandemic. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2006, 10, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sigala, M. Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouder, P. Reset redux: Possible evolutionary pathways towards the transformation of tourism in a COVID-19 world. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuyama, T. Analysis of optimal timing of tourism demand recovery policies from natural disaster using the contingent behavior method. Tour. Manag. 2018, 64, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benckendorff, P.; Zehrer, A. A network analysis of tourism research. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 43, 121–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.; Lipsey, M.; Derzon, J. The effects of school-based intervention programs on aggressive behavior: A meta-analysis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2003, 71, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawardena, R.; Ranasinghe, P.; Byrne, N.M.; Soares, M.J.; Katulanda, P.; Hills, A.P. Prevalence and trends of the diabetes epidemic in South Asia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lin, C.C.; Gao, X.; Chen, X.S.; Chen, Q.; Cohen, M.S. China’s Syphilis Epidemic: A Systematic Review of Seroprevalence Studies. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2006, 33, 726–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Lipsitz, O.; Nasri, F.; Lui, L.M.; Gill, H.; Phan, L.; Chen-Li, D.; Iacobucci, M.; Ho, R.; Majeed, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, D.; Batool, A.; Bazaz, M.A. Three months of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev. Med. Virol. 2020, 30, e2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grépin, K.A.; Ho, T.L.; Liu, Z.; Marion, S.; Piper, J.; Worsnop, C.Z.; Lee, K. Evidence of the effectiveness of travel-related measures during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid systematic review. BMJ Global Health 2021, 6, e004537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, A.; St-Onge Ahmad, S.; Beck, C.R.; Nguyen-Van-Tam, J.S. The roles of transportation and transportation hubs in the propagation of influenza and coronaviruses: A systematic review. J. Travel Med. 2016, 23, tav002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ritchie, B.W.; Jiang, Y. A review of research on tourism risk, crisis and disaster management: Launching the annals of tourism research curated collection on tourism risk, crisis and disaster management. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 79, 102812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, T.H.; Haque, M.O. The swine flu and its impacts on tourism in Brunei. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 36, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohoe, H.; Pennington-Gray, L.; Omodior, O. Lyme disease: Current issues, implications, and recommendations for tourism management. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicola, M.; Alsafi, Z.; Sohrabi, C.; Kerwan, A.; Al-Jabir, A.; Iosifidis, C.; Agha, R. The Socio-Economic Implications of the Coronavirus and COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 78, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Francisco, N.; Donadel, M.; Jit, M.; Hutubessy, R. A systematic review of the social and economic burden of influenza in low- and middle-income countries. Vaccine 2015, 33, 6537–6544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruk Aladag, O.; Ali Köseoglu, M.; King, B.; Mehraliyev, F. Strategy implementation research in hospitality and tourism: Current status and future potential. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moletta, L.; Pierobon, E.S.; Capovilla, G.; Costantini, M.; Salvador, R.; Merigliano, S.; Valmasoni, M. International guidelines and recommendations for surgery during Covid-19 pandemic: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 79, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Huang, X.; Li, Z. A content analysis of Chinese news coverage on COVID-19 and tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.; Gray, R.; Lo Monaco, S.; O’Donoghue, B.; Nelson, B.; Thompson, A.; McGorry, P. The potential impact of COVID-19 on psychosis: A rapid review of contemporary epidemic and pandemic research. Schizophr. Res. 2020, 222, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders-Hastings, P.; Crispo, J.A.G.; Sikora, L.; Krewski, D. Effectiveness of personal protective measures in reducing pandemic influenza transmission: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemics 2017, 20, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicola, M.; O’Neill, N.; Sohrabi, C.; Khan, M.; Agha, M.; Agha, R. Evidence based management guideline for the COVID-19 pandemic—Review article. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 77, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visacri, M.B.; Figueiredo, I.V.; de Mendonça Lima, T. Role of pharmacist during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 17, 1799–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harkin, D.W. Ethics for surgeons during the COVID-19 pandemic, review article. Ann. Med. Surg. 2020, 55, 316–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalmuanawma, S.; Hussain, J.; Chhakchhuak, L. Applications of machine learning and artificial intelligence for Covid-19 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic: A review. ChaosSolitons Fractals 2020, 139, 110059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sausmarez, N.; Marketing, T. Malaysia’s response to the Asian financial crisis: Implications for tourism and sectoral crisis management. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2004, 15, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyitoğlu, F.; Ivanov, S. Service robots as a tool for physical distancing in tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 1631–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, S.K. Travel and tourism after COVID-19—Business as usual or opportunity to reset? Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 646–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.H.; Scott, D.; Gössling, S. Pandemics, transformations and tourism: Be careful what you wish for. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 577–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jina, X.C.; QU, M.; Bao, J. Impact of crisis events on Chinese outbound tourist flow: A framework for post-events growth. Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becken, S.; Hughey, K.F.D. Linking tourism into emergency management structures to enhance disaster risk reduction. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 77e85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Novelli, M.; Gussing Burgess, L.; Jones, A.; Ritchie, W. ‘No Ebola…still doomed’—The Ebola-induced tourism crisis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 70, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, H.I.; Chen, C.C.; Tseng, W.C.; Ju, L.F.; Huang, B.W. Assessing impacts of SARS and Avian Flu on international tourism demand to Asia. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 917–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyanto, I.; Wiblishauser, M.; Pennington-Gray, L.; Schroeder, A. The dynamics of travel avoidance: The case of Ebola in the US. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 20, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giglio, O.; Fasano, F.; Diella, G.; Lopuzzo, M.; Napoli, C.; Apollonio, F.; Brigida, S.; Calia, C.; Campanale, C.; Marzella, A.; et al. Legionella and legionellosis in touristic-recreational facilities: Influence of climate factors and geostatistical analysis in Southern Italy (2001–2017). Environ. Res. 2019, 178, 108721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAleer, M.; Huang, B.-W.; Kuo, H.-I.; Chen, C.-C.; Chang, C.-L. An econometric analysis of SARS and Avian Flu on international tourist arrivals to Asia. Environ. Model. Softw. 2010, 25, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobieralski, J.B. COVID-19 and airline employment: Insights from historical uncertainty shocks to the industry. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 5, 100123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suau Sanchez, P.; Voltes-Dorta, A.; Cugueró-Escofet, N. An early assessment of the impact of COVID-19 on air transport: Just another crisis or the end of aviation as we know it? J. Transp. Geogr. 2020, 86, 102749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X. Coronavirus pandemic and tourism: Dynamic stochastic general equilibrium modeling of infectious disease outbreak. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 83, 102913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Nguyen, T.H.H.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A. Coronavirus impacts on post-pandemic planned travel behaviours. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 86, 102964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Nicolau, J.L. An open market valuation of the effects of COVID-19 on the travel and tourism industry. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 83, 102990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antara, (Travel Agencies: We Are Collapsing Because of the Impact of Corona) Bisnis Tempo. 5 March 2020. Available online: https://bisnis.tempo.co/read/1315728/dampak-corona-biro-travel-saat-ini-kami-memang-kolaps/full&view=ok (accessed on 5 February 2020).

- Henderson, J.C. Tourism Crises: Causes, Consequences and Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Novelli, M.; Morgan, N.; Nibigira, C. Tourism in a post-conflict situation of fragility. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 1446–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hong, A.; Li, X.; Gao, J. Marketing innovations during a global crisis: A study of China firms’ response to COVID-19. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Vaishya, R. Effects of COVID 19 pandemic in daily life. Curr. Med. Res. Pract. 2020, 10, 78–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, R.E.; van Schalkwyk, M.C.; Akl, E.A.; Kristjannson, E.; Lotfi, T.; Petkovic, J.; Petticrew, M.P.; Pottie, K.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V. A framework for identifying and mitigating the equity harms of COVID-19 policy interventions. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 128, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verikios, G.; Sullivan, M.; Stojanovski, P.; Giesecke, J.A.; Woo, G. The Global Economic Effects of Pandemic Influenza; Centre of Policy Studies (CoPS): Budapest, Hungary, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, I.; Maity, P. COVID-19 outbreak: Migration, effects on society, global environment and prevention. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakas, D.; Triantafyllou, A. Commodity price volatility and the economic uncertainty of pandemics. Econ. Lett. 2020, 193, 109283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalan, H.S.; Misra, A. COVID-19 Pandemic and Challenges for Socio-economic Issues, Healthcare and National Programs in India. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 757–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharif, A.; Aloui, C.; Yarovaya, L. Covid-19 pandemic, oil prices, stock market, geo political risk and policy uncertainty nexus in the us economy: Fresh evidence from the wavelet-based approach. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2020, 70, 101496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, B.N. Economic impact of government interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic: International evidence from financial markets. J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 2020, 27, 100371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Harris, L. The impact of Covid-19 pandemic on corporate social responsibility and marketing philosophy. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.D.; Keogh-Brown, M.R.; Barnett, T.; Tait, J. The economy-wide impact of pandemic influenza on the UK: A computable general equilibrium modelling experiment. BMJ 2009, 339, b4571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]