Decision-Making Behavior and Risk Perception of Chinese Female Wildlife Tourists

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- To describe characteristics of female tourists participating in wildlife tourism;

- To examine the risk perceptions of Chinese female wildlife tourists;

- To explore the involvement of Chinese female tourists in tourism decision-making and the demographic factors impacting them;

- To validate the relationship between risk perception and participation in tourism decision-making.

2. Literature Review, Research Hypotheses, and Model

2.1. Literature Review

2.1.1. Wildlife Tourism

2.1.2. Female Decision-Making Behavior

2.1.3. Tourism Risk

2.2. Research Hypotheses

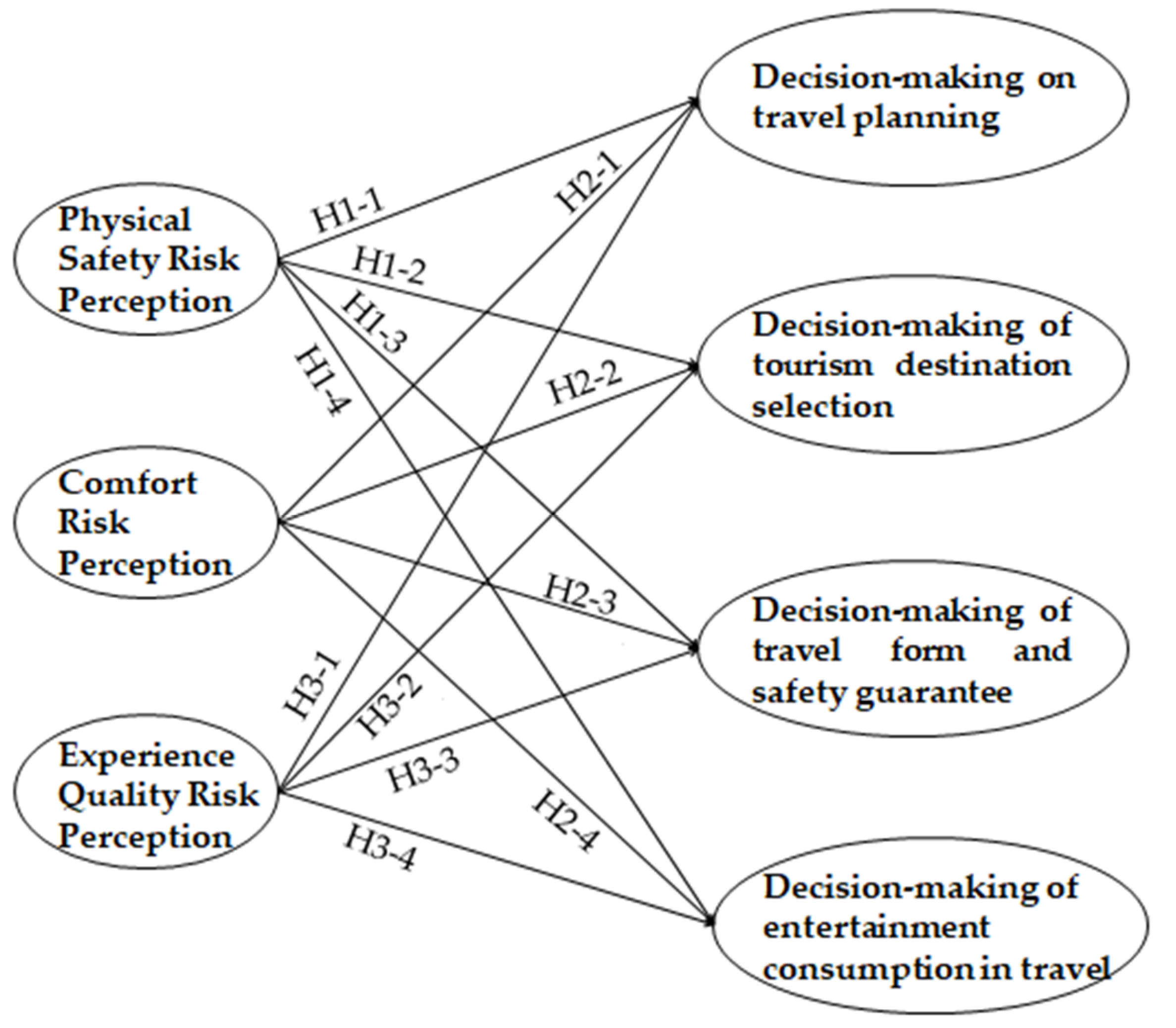

2.3. Research Model

3. Questionnaires Design and Analytical Methods

3.1. Questionnaires Design

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Attributes of Respondents and Travel Characteristics

4.1.1. Attributes of Respondents

4.1.2. Travel Characteristics

4.2. Decision-Making Participation

4.2.1. Female Travelers’ Decision-Making Influence

4.2.2. Female Tourists’ Decision-Making Participation

4.3. Risk Perception and Decision Participation

4.3.1. General Characteristics

4.3.2. Risk Perception

4.3.3. Decision Participation

4.4. Structural Equation Model (SEM)

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions and Implications for Sustainable Tourism

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitation and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Movono, A.; Dahles, H. Female empowerment and tourism: A focus on businesses in a Fijian village. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.; Newsome, D.; Wu, B.; Morrison, A.M. Wildlife tourism in China: A review of the Chinese research literature. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 1116–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.L.; Wang, X.G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.L.; et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cong, L.; Wu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Newsome, D. Risk Perception of interaction with dolphin in Bunbury, West Australia. Acta Sci. Nat. Univ. Pekin. 2017, 1, 179–188. [Google Scholar]

- Panta, S.K.; Thapa, B. Entrepreneurship and women’s empowerment in gateway communities of Bardia National Park, Nepal. J. Ecotourism 2018, 17, 20–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón, D.M.; Cole, S. No sustainability for tourism without gender equality. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 903–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontogeorgopoulos, N. Wildlife tourism in semi-captive settings: A case study of elephant camps in northern Thailand. Curr. Issues Tour. 2009, 12, 429–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, M. Risk and uncertainty in travel decision-making: Tourist and destination perspective. J. Travel Res. 2016, 57, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-Domecq, C.; Pritchard, A.; Segovia-Perez, M.; Morgan, N.; Villace-Molinero, T. Tourism gender research: A critical accounting. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 52, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Filiatrault, P.; Ritchie, J.R. Joint purchasing decisions: A comparison of influence structure in family and couple decision making units. J. Consum. Res. 1980, 7, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.C.L.; Khoo-Lattimore, C.; Arcodia, C. A systematic literature review of risk and gender research in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moorhouse, T.P.; D’Cruze, N.C.; Macdonald, D.W. Are Chinese nationals’ attitudes to wildlife tourist attractions different from those of other nationalities? J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 12–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoine, Z. Wives’ involvement in tourism decision processes. Ann. Tour. Res. 1998, 5, 890–930. [Google Scholar]

- Lepp, A.; Gibson, H. Tourist roles, perceived risk and international tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 606–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, D.; Rodger, K.; Pearce, J.; Chan, K.L.J. Visitor satisfaction with a key wildlife tourism destination within the context of a damaged landscape. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 729–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seow, D.; Brown, L. The solo female Asian tourist. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 1187–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uduji, J.I.; Okolo-Obasi, E.N.; Asongu, S.A. Sustaining cultural tourism through higher female participation in Nigeria: The role of corporate social responsibility in oil host communities. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 22, 120–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, E.C.L.; Khoo-Lattimore, C.; Arcodia, C. Constructing space and self through risk taking: A case of Asian solo female travelers. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Hitchcock, M.J. The Chinese female tourist gaze: A netnography of young women’s blogs on Macao. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizam, A. Research on Tourism Consumer Behavior; Northeast University of Finance and Economics Press: Dalian, China, 2005; pp. 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Shackley, M.L. Wildlife Tourism; International Tourism Business Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kozak, M.; Crotts, J.C.; Law, R. The impact of the perception of risk on international travellers. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2007, 9, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, P.C.; Braithwaite, D. Towards a conceptual framework for wildlife tourism. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamula Nikolić, T.; Pantić, S.P.; Paunović, I.; Filipović, S. Sustainable travel decision-making of Europeans: Insights from a household survey. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øian, H.; Aas, Ø.; Skår, M.; Andersen, O.; Stensland, S. Rhetoric and hegemony in consumptive wildlife tourism: Polarizing sustainability discourses among angling tourism stakeholders. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1547–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Zhou, Y.; Wei, X.; Wu, J. A Study on the environmental risk perceptions of inbound tourists for China using negative IPA assessment. Tour. Trib. 2015, 30, 54–62. [Google Scholar]

- Asmelash, A.G.; Kumar, S. Assessing progress of tourism sustainability: Developing and validating sustainability indicators. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Cong, L.; Wall, G. Tourists’ spatio-temporal behaviour and concerns in park tourism: Giant Panda National Park, Sichuan, China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 924–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, C.A.; Snepenger, J.D. Family decision making and tourism behavior and attitudes. J. Travel Res. 1988, 26, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, R.; Packer, J.; Sutherland, L.A. Visitors’ memories of wildlife tourism: Implications for the design of powerful interpretive experiences. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 770–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Packer, J.; Ballantyne, R. Comparing captive and non-captive wildlife tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 1242–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodger, K.; Moore, S.A.; Newsome, D. Wildlife tourism, science and actor network theory. Ann. Tour. Res. 2009, 36, 645–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Curtin, S. The self-presentation and self-development of serious wildlife tourists. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2010, 12, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Cruze, N.; Niehaus, C.; Balaskas, M.; Vieto, R.; Carder, G.; Richardson, V.A.; Macdonald, D.W. Wildlife tourism in Latin America: Taxonomy and conservation status. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1562–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila-Foucat, V.S.; Rodríguez-Robayo, K.J. Determinants of livelihood diversification: The case wildlife tourism in four coastal communities in Oaxaca, Mexico. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, F.G.; Long, G.L.; Liu, X.S. Two-step quantum direct communication protocol using the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen pair block. Phys. Rev. A 2003, 68, 042317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cong, L.; Wu, B.; Morrison, A.M.; Shu, H.; Wang, M. Analysis of wildlife tourism experiences with endangered species: An exploratory study of encounters with giant pandas in Chengdu, China. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnaird, V.; Hall, D. Understanding tourism processes: A gender-aware framework. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A. Travel risks vs. tourist decision making: A tourist perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Syst. 2015, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibnou-Laaroussi, S.; Rjoub, H.; Wong, W.K. Sustainability of green tourism among international tourists and its influence on the achievement of green environment: Evidence from North Cyprus. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.C.; Hsieh, A.T.; Yeh, Y.C.; Tsai, C.W. Who is the decision-maker: The parents or the child in group package tours? Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, L.A. Family decision at the turn of the century: Has the changing structure of households impacted the family deci-sion-making process. J. Consum. Behav. 2002, 22, 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Zalatan, A. The determinants of planning time in vacation travel. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, F.; Wu, M. Research on factors affecting tourism decision-making. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 27, 1214–1217. [Google Scholar]

- Cahyanto, I.; Pennington-Gray, L.; Thapa, B.; Srinivasan, S.; Villegas, J.; Matyas, C.J.; Kiousis, S. An empirical evaluation of the determinants of tourist’s hurricane evacuation decision making. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2014, 2, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardani, A.; Streimikiene, D.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Cavallaro, F.; Nilashi, M.; Jusoh, A.; Zare, H. Application of structural equation modeling (SEM) to solve environmental sustainability problems: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsaur, S.H.; Tzeng, G.H.; Wang, G.C. The application of AHP and fuzzy MCDM on the evaluation study of tourist risk. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 796–812. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson, P.E. Gender differences in risk perception: Theoretical and methodological perspectives. Risk Anal. 1998, 18, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sönmez, S.F.; Graefe, A.R. Influence of terrorism risk on foreign tourism decisions. Ann. Tour. Res. 1998, 25, 112–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riley, S.J.; Decker, D.J. Risk perception as a factor in wildlife stakeholder acceptance capacity for cougars in Montana. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2000, 5, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichel, A.; Fuchs, G.; Uriely, N. Perceived risk and the non-institutionalized tourist role: The case of Israeli student ex-backpackers. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu-Lastres, B.; Ritchie, B.W.; Pan, D.Z. Risk reduction and adventure tourism safety: An extension of the risk per-ception attitude framework (RPAF). Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X. Women’s work, men’s work: Gender and tourism among the Miao in rural China. Anthropol. Work Rev. 2013, 34, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepp, A.; Gibson, H.; Lane, C. Image and perceived risk: A study of Uganda and its official tourism website. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusseau, D.; Derous, D. Using taxonomically-relevant condition proxies when estimating the conservation impact of wildlife tourism effects. Tour. Manag. 2019, 75, 547–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehl, W.S.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Risk perceptions and pleasure travel: An exploratory analysis. J. Travel Res. 1992, 30, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschauer, W. Perceptions of tourists at risky destinations. A model of psychological influence factors. Tour. Rev. 2010, 65, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Choi, S.; Agrusa, J.; Wang, K.C.; Kim, Y. The role of family decision makers in festival tourism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.M. Farmers’ perspectives of conflict at the wildlife–agriculture boundary: Some lessons learned from African subsistence farmers. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2004, 9, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtin, S. Wildlife tourism: The intangible, psychological benefits of human–wildlife encounters. Curr. Issues Tour. 2009, 12, 451–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaske, J.J.; Timmons, N.R.; Beaman, J.; Petchenik, J. Chronic wasting disease in Wisconsin: Hunter behavior, perceived risk, and agency trust. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2004, 9, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gstaettner, A.M.; Rodger, K.; Lee, D. Visitor perspectives of risk management in a natural tourism setting: An application of the theory of planned behaviour. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2017, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E. Performing colonisation: The manufacture of Black female bodies in tourism research. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 66, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonmez, S.F.; Graefe, A.R. Determining future travel behavior from past travel experience and perceptions of risk and safety. J. Travel Res. 1998, 37, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, M. The influence of risk perception on destination choice processes. Eur. J. Tourism Res. 2018, 18, 160–163. [Google Scholar]

- Monk, J.; Hanson, S. On not excluding half of the human in human geography. Prof. Geogr. 1982, 34, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman, J.; Abbas, J.; Mahmood, S.; Nurunnabi, M.; Bano, S. The influence of islamic religiosity on the perceived socio-cultural impact of sustainable tourism development in pakistan: A structural equation modeling approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ballantyne, R.; Hughes, K.; Lee, J.; Packer, J.; Sneddon, J. Visitors’ values and environmental learning outcomes at wildlife attractions: Implications for interpretive practice. Tour. Manag. 2018, 64, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.A.; Combrink, T.E. Japanese female travelers: A unique outbound market. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2000, 5, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Lima, C.; Everingham, Y.; Diedrich, A.; Mustika, P.L.; Hamann, M.; Marsh, H. Using multiple indicators to evaluate the sustainability of dolphin-based wildlife tourism in rural India. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1687–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoine, Z.; Miao, X. Research on wife’s participation in tourism decision-making (translation). Hum. Geogr. 2003, 18, 66–69. [Google Scholar]

| Subject | Attribute Level | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | <25 | 33.1 |

| 25–34 | 24.9 | |

| 35–44 | 28.9 | |

| 45–54 | 9.9 | |

| ≥55 | 3.4 | |

| Job | Self-employed/Business owner | 5.3 |

| Manager | 5.1 | |

| Common employees | 36.1 | |

| Technical personnel | 11.1 | |

| Liberal professions/Full-time housewife | 10.8 | |

| Retiree | 4.3 | |

| Student | 27.2 | |

| Educational Level | Junior high school and below | 1.7 |

| Senior school or technical secondary school | 9.4 | |

| Junior College | 22.9 | |

| Undergraduate college | 46.3 | |

| Graduate and above | 19.8 | |

| Number of children | No children | 45.3 |

| One | 43.4 | |

| Two | 11.1 | |

| Three or more | 0.2 | |

| Annual income (Yuan) | <30,000 | 34.9 |

| 30,000–50,000 | 23.1 | |

| 50,001–100,000 | 19.8 | |

| 100,001–200,000 | 12.8 | |

| 200,001–300,000 | 5.3 | |

| >300,000 | 4.1 |

| Subdivision Decision Content | Level of Participation | Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial preparation activities | Decide on the date of the holiday | 3.67 | 1.15 |

| Pick destination | 3.87 | 1.13 | |

| Search for wildlife tourism information | 3.55 | 1.06 | |

| Search for destination information | 3.79 | 1.10 | |

| Search for travel agency information | 3.26 | 1.23 | |

| Subtotal | 3.63 | 0.88 | |

| pre-trip financing | Budget and financial arrangement | 3.61 | 1.10 |

| Registration travel agency | 3.13 | 1.28 | |

| Buy airline tickets and train tickets | 3.56 | 1.20 | |

| Buy tourist attractions tickets | 3.57 | 1.17 | |

| Subtotal | 3.47 | 0.95 | |

| Pre-departure arrangements | Transport arrangements | 3.60 | 1.15 |

| Accommodation arrangements | 3.74 | 1.14 | |

| Prepare luggage | 4.02 | 1.08 | |

| Other arrangements (e.g., medical insurance) | 3.33 | 1.26 | |

| Subtotal | 3.67 | 0.92 | |

| Destination activities | Choose tourist attractions | 3.88 | 1.00 |

| Choosing tour guides and commentary system | 3.14 | 1.92 | |

| Choose restaurants | 3.64 | 1.10 | |

| Shopping activities | 3.22 | 1.25 | |

| Entertainment activities | 3.53 | 1.12 | |

| Treat emergencies | 3.54 | 1.13 | |

| Subtotal | 3.49 | 0.80 | |

| Average | 3.57 | 1.15 | |

| New Extraction Factor | Problem Item | Factor Loading | Interpretation of Variance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical safety risk | Worried that wildlife threatens personal safety | 0.892 | 53.108 | KMO = 0.872 Bartlett = 1942.601 Freedom = 36 Sig. = 0.000 |

| Worried that tourism projects endanger personal safety | 0.849 | |||

| Worried about various accidents on the road that endanger personal safety | 0.784 | |||

| Comfort risk | Worried about the climatic conditions of the destination, such as dissatisfaction | 0.842 | 14.235 | |

| Worried about poor destination infrastructure | 0.739 | |||

| Worried about the inconvenience of destination traffic | 0.590 | |||

| Experience quality risk | Worried about the chances of seeing wild animals | 0.918 | 8.359 | |

| Worried that the travel experience has not met expectations | 0.810 |

| Factors | Items | Factor Loading | Interpretation of Variance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-tour Travel Decision-making | Budget and financial arrangements | 0.511 | 44.739 | KMO = 0.916 Bartlett = 4369.378 Freedom = 171 Sig. = 0.000 |

| Buy air, train, bus tickets | 0.803 | |||

| Purchase tickets for scenic spots | 0.817 | |||

| Search and arrangement of traffic information | 0.737 | |||

| Search and arrangement of accommodation information | 0.714 | |||

| Prepare luggage | 0.534 | |||

| Destination Selection | Decide on the date and duration of the holiday | 0.648 | 8.188 | |

| Selection of destinations | 0.774 | |||

| Selection of tourist attractions | 0.597 | |||

| Inquiry of wildlife tourism information | 0.740 | |||

| Search for destination information | 0.760 | |||

| Travel Method and Security | Inquiry of travel agency information | 0.788 | 6.584 | |

| Sign up for a tour group | 0.807 | |||

| Choosing tour guides and persuasion services | 0.529 | |||

| Arrangement of medical and insurance items | 0.520 | |||

| Treatment of special and unexpected events | 0.503 | |||

| Entertainment Consumption | Choose restaurant | 0.647 | 5.729 | |

| Choose shopping activities | 0.843 | |||

| Choose recreational activities | 0.792 |

| Hypothesis | Conclusion |

|---|---|

| H1-1: Risk perception positively impacts decision-making behavior | accepted |

| H1-2: Physical safety risk positively impacts travel method and safety guarantee | accepted |

| H1-3: Comfort risk perception positively impacts pre-trip planning decisions | accepted |

| H1-4: Comfort risk perception significantly positive impact decision-making of tourism destination selection | accepted |

| H2-1: Comfort risk perception significantly positive impact decision-making of entertainment consumption in travel | accepted |

| H2-2: Experience quality risk perception significantly positive impact decision-making of entertainment consumption in travel | accepted |

| Variables | Standardized Estimation | Standard Error | Critical Value | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision-Making of Travel Form and Safety Guarantee < ⟵Physical safety risk | 0.237 | 0.056 | 4.223 | *** | ||

| Decision-making on travel planning before Tourism < ⟵ Comfort risk | 0.176 | 0.048 | 3.660 | *** | ||

| Decision-Making of Tourism Destination Selection < ⟵ Comfort risk | 0.188 | 0.051 | 3.715 | *** | ||

| Decision-making of Entertainment Consumption in Travel < ⟵ Comfort risk | 0.128 | 0.053 | 2.418 | ** | ||

| Decision-making of Entertainment Consumption in Travel < ⟵ Experience quality risk | 0.122 | 0.047 | 2.623 | ** | ||

| Index | χ2/df | GFI | CFI | NFI | IFI | RMSEA |

| Analysis result | 4.214 | 0.813 | 0.824 | 0.783 | 0.806 | 0.062 |

| Ideal standard | 1 < 5 | >0.80 | >0.80 | >0.80 | >0.80 | <0.08 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cong, L.; Wang, Q.; Wall, G.; Su, Y. Decision-Making Behavior and Risk Perception of Chinese Female Wildlife Tourists. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10301. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810301

Cong L, Wang Q, Wall G, Su Y. Decision-Making Behavior and Risk Perception of Chinese Female Wildlife Tourists. Sustainability. 2021; 13(18):10301. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810301

Chicago/Turabian StyleCong, Li, Qiqi Wang, Geoffrey Wall, and Yijing Su. 2021. "Decision-Making Behavior and Risk Perception of Chinese Female Wildlife Tourists" Sustainability 13, no. 18: 10301. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810301

APA StyleCong, L., Wang, Q., Wall, G., & Su, Y. (2021). Decision-Making Behavior and Risk Perception of Chinese Female Wildlife Tourists. Sustainability, 13(18), 10301. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810301