Abstract

Suppressing knowledge hiding is a prerequisite for achieving positive knowledge interactions among people. Most previous studies concentrate on knowledge hiding in organizations, but the quantitative examination of knowledge hiding antecedents in the online knowledge community has been limited. This study investigates individuals’ knowledge hiding intentions in the context of the online knowledge community through an integrated framework of protection motivation theory, self-determination theory, and social exchange beliefs. We tested the research model through a valid sample of 377 respondents from Chinese online knowledge community users. The results demonstrate that individuals’ threat appraisal (perceived severity and perceived vulnerability) and intrinsic motivation (perceived autonomy and perceived relatedness) are negatively associated with interdependence. Additionally, interdependence within the online knowledge community is proved to negatively affect individuals’ knowledge hiding intention. Furthermore, reciprocity and trust moderate the relationship between interdependence and knowledge hiding intentions. This study enriches the academic literature in the knowledge hiding field, and the findings provide an in-depth understanding of knowledge hiding in the context of the online knowledge community.

1. Introduction

The online knowledge community (hereafter ‘OKC’) provides users with various sources of knowledge. With the fast and continued advancement of information and communication technology, the OKC has become a convenient medium empowering users to share and grow the world’s knowledge [1]. Online knowledge communities (hereafter ‘OKCs’) such as Quora (http://www.quora.com/ accessed on 6 June 2021), Zhihu (http://www.zhihu.com/ accessed on 6 June 2021), etc., have drastically changed knowledge transfer. Specifically, OKC users ask, answer, and edit questions there, and other members follow questions either factually or in the form of opinions. As with all advantages, the OKC has some disadvantages [1,2,3]. For instance, the lack of knowledge sharing rewards (e.g., economic incentives), the absence of feedback for knowledge sharing from other users, knowledge infringements, individual traits, personal concerns, etc., lead to knowledge hiding in OKCs [1,4,5,6]. As a result, a growing number of users are inclined to hide knowledge rather than share knowledge in OKCs.

Users may share or hide knowledge in OKCs. Given the importance of knowledge to the functioning of OKCs, one of the most pressing questions is whether individuals share or keep information hidden. Sharing and hiding have two distinct theoretical dimensions [6]. Jha and Varkkey [7] defined knowledge hiding as knowledge creators’ intentional concealment of knowledge. It can be characterized as a new social counterproductive behavior for knowledge practice in OKCs that has emerged recently [1,8]. Knowledge hiding is more than just the polar opposite of knowledge sharing [9,10]. For this reason, factors fostering knowledge hiding should be induced by different sources. Studies in knowledge management pointed out that counterproductive knowledge behaviors such as knowledge hiding should be given more attention because many measures aimed at motivating knowledge sharing in OKCs have failed to meet the operation expectations in these communities [4,8,11,12].

With studies in knowledge sharing, an increasing number of studies have paid attention to knowledge hiding and knowledge hoarding in recent years [9,13,14]. Theoretical perspectives on counterproductive knowledge behaviors include the conservation of resources theory [9,15], cooperation and competition [16], extended self theory [17], goal orientation theory [18], psychological contract theory [12], and psychological ownership theory [9,19]. From these theories and studies, it was proved that a group of organizational or psychological factors were associated with counterproductive knowledge behaviors: perceptions of competitiveness [5,16,20], performance goal orientation [18,21,22], Machiavellianism [23], social comparison information [18,24], job insecurity [7,25,26], lack of confidence [7,26], neuroticism [5], lack of incentives [5], lack of recognition for knowledge sharing [7], characteristics of knowledge itself [16], and knowledge complexity [27].

Although scholars have conducted many interesting studies on knowledge withholding, knowledge hiding, and knowledge hoarding, it is still vital to explore the determinants contributing to counterproductive knowledge behaviors compared to research in knowledge sharing. However, few studies have discussed counterproductive knowledge behaviors and examined the causal relationship between psychological and social factors, individuals’ interdependence, and knowledge hiding intentions in OKCs. Studies concerning knowledge hiding at the organizational or team level usually discuss organizational factors (e.g., organizational climate, organizational practices), team and interpersonal factors (e.g., team climate, interpersonal distrust, interpersonal ostracism), individual knowledge hiding (e.g., evasive hiding, playing dumb, rationalized hiding), and firm/team performance [28,29]. For instance, knowledge hiding would not be socially accepted in an organizational/team climate that encourages knowledge sharing [28]. By contrast, the online knowledge community plays an essential role in transferring social knowledge, and it is a place where social knowledge is created and exchanged. The weak relationships among users in the online knowledge community make it necessary to extend the knowledge hiding concept and its antecedents from the organizational/team context. Accordingly, research filling this gap could be beneficial for determining prospective OKC users who passively participate in knowledge sharing, contributing to effective measures to create and improve OKCs. As a result, research that addresses this problem must be meaningful from both academic and practical perspectives.

To fill the research gap mentioned above, we propose an integrated research framework of protection motivation theory (PMT), self-determination theory (SDT), and social exchange beliefs to provide a novel explanation for knowledge hiding intentions in OKCs. This study investigates psychological factors related to interdependence within the OKC and knowledge hiding intention using the integrated framework.

First, we examine threat appraisal and intrinsic motivation within the OKC. To begin with, we consider the potential individuals’ threat appraisal of knowledge sharing based on PMT [1]. PMT was initially created to help us grasp individuals’ reactions to fear appeals and has been adopted to explain individuals’ security or privacy protection in previous studies [30,31]. Thus, we propose that knowledge hiding is considered a user’s self-protection behavior in OKCs. Determinants such as perceived severity and perceived vulnerability are proposed to negatively affect interdependence within OKCs. Second, we also employ SDT for this study. SDT demonstrates a comprehensive framework for the research of individuals’ motivation. Specifically, SDT considers how social and cultural factors influence people’s feelings of volition and initiative, overall well-being, and the quality of their performance [32,33]. SDT in previous studies has been designed to address the innate human need for feeling competent, related, or autonomous of a specific behavior [33,34]. This study proposes intrinsic motivations such as perceived autonomy, perceived competence, and perceived relatedness to foster interdependence within OKCs. Finally, we identify that social exchange beliefs such as trust and reciprocity occur among exchanges of OKC users. Intensive interpersonal communications and exchanges involved in OKCs can be interpreted by social exchange beliefs [35]. In addition, this study assumes that trust and reciprocity moderate the relationship between interdependence and knowledge hiding intentions.

To achieve the research purpose, we raise the following research questions:

Q1. How do users’ perceived severity and vulnerability to knowledge sharing in the OKC predict their interdependence within the OKC?

Q2. How do users’ perceived competence, autonomy, and relatedness of personal knowledge predict their interdependence within the OKC?

Q3. How does users’ interdependence within the OKC influence their knowledge hiding intentions?

Q4. How do social exchange beliefs (reciprocity and trust) moderate the relationship between interdependence within the OKC and knowledge hiding intentions?

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Knowledge Hiding

When individuals share knowledge, their efforts are less than what they are completely capable of offering, a phenomenon known as knowledge hiding. Although people become aware of knowledge hiding when concerned with sharing knowledge, they frequently regard it as the polar opposite of knowledge sharing and pay insufficient attention. Connelly et al. [13] proposed a relatively straightforward concept of knowledge hiding behavior based on past studies. They distinguished knowledge hiding from knowledge hoarding and knowledge withholding. Knowledge hiding represents “the act of intentional concealing specific knowledge requested from another person” [13]. Knowledge hiding is characterized by a lack of knowledge sharing and the willful concealing of desired information from another individual [36]. The act of hiding knowledge is not considered to be always negative. For instance, an individual may conceal knowledge to keep the information safe or protect a third party’s interests [13].

In contrast to intentionally concealing knowledge, knowledge non-sharing may arise due to a lack of understanding of individuals’ organizational expectations or personal requirements. When it comes to knowledge withholding, it is usually considered as an aggregation of knowledge hiding and knowledge hoarding. Additionally, it refers to actions in which individuals offer fewer knowledge contributions to others than they could have done otherwise. Finally, knowledge hoarding can be conceptualized as behaviors gathering or retaining knowledge that may or may not be shared in the future, depending on the situation. Consequently, established on a solid basis, scholars examined the concept of knowledge hiding from different perspectives. Definitions of knowledge hiding proposed by previous studies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definition of knowledge hiding developed from selected studies.

Past studies have examined a variety of determinants resulting in knowledge hiding from different theoretical perspectives. Established on self-determination theory, Stenius et al. [42] investigated the influence of motivation on knowledge sharing by examining how qualitatively different motivation types predict knowledge sharing and counterproductive knowledge behavior. They discovered that the identified motivation was the most potent determinant, whereas the intrinsic, introjected, and external motivation had no influence on knowledge sharing. Furthermore, counterproductive knowledge behavior was related to identified motivation for knowledge sharing but not the external motivation. Lin and Wang [43] investigated the effect of personality traits on knowledge hiding intention in university students. Abubakar et al. [9] empirically proved that distributive, procedural, and interpersonal communication fairness affect employees’ degrees of knowledge hiding behavior by using social exchange theory and psychological ownership of knowledge.

External pressures are often used to encourage people to keep their knowledge hidden. Gagné et al. [44] discovered that task interdependence was positively associated with three different types of counterproductive behaviors, such as mysterious and rationalized hiding and playing dumb through the use of external regulation to share information. Anaza and Nowlin [5] discussed counterproductive knowledge behavior drivers from the perspectives of the environment, incentives, and individual characteristics. The findings revealed that knowledge withholding was influenced by environmental factors, such as internal competition and past opportunistic coworker behaviors. Incentives and feedback for knowledge sharing from upper management were also critical determinants. The neuroticism of employees played an important role as well. Demirkasimoglu [45] also discussed how personality influences knowledge hiding.

Social exchange theory has often been used for examining knowledge sharing in past studies [4,11,46,47]. Nadeem et al. [46] explored the moderating role of trust in knowledge hiding behavior. They found that different trusts (cognitive-based trust and affective-based trust) negatively moderated the relationship between shared goals and knowledge hiding behavior. Furthermore, Koay et al. [47] proved that perceived loss of knowledge power, perceived loss of face, perceived organizational incentives, affective-based trust, and self-efficacy influenced knowledge hiding within organizations by applying interpersonal behavior and social exchange theory. Among these factors, perceived loss of knowledge power had the most substantial influence on knowledge hiding. Wang et al. [11] discussed students’ counterproductive knowledge behavior by combining personality traits, social exchange theory, and social identity theory. They discovered that perceived social identity, expected rewards, and expected associations directly impacted knowledge withholding intention. At the same time, extraversion, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience indirectly affected knowledge withholding intention through the mediating variable of perceived social identity.

Pereira and Mohiya [48] investigated individual employees’ intentions and organizational support from both positive and negative perspectives in knowledge sharing and hiding. They concluded that a positive work environment and openness in organizations could result in collaborative work arrangements, reducing knowledge hiding and motivating employee knowledge sharing. According to Shen et al. [8], secondary control plays a critical role in counterproductive knowledge behavior, with both predictive control and vicarious control significantly affecting knowledge withholding in a positive way. To distinguish between knowledge sharing and knowledge withholding, Kang [36] and Das and Chakraborty [49] demonstrated that knowledge sharing and knowledge withholding are two separate concepts using Herzberg’s two-factor theory. They discovered that knowledge withholding could be classified into two distinct behaviors: intentional knowledge hiding and unintentional knowledge hoarding.

After reviewing previous studies, we found that knowledge hiding has received much attention in organizations or teams. However, studies exploring knowledge hiding in the OKC have not been conducted until now. Today, online is a crucial place to exchange knowledge. Therefore, it is worth trying to investigate knowledge hiding in OKCs.

2.2. Protection Motivation Theory

Protection motivation theory (PMT) was initially proposed by Rogers [50] to contribute to a better understanding of fear appeals and how individuals respond to fears. PMT has been widely discussed and regarded as one of the most powerful explanatory theories that could predicate individuals’ intention to engage in a series of protective activities [51]. According to PMT, threat appraisal and coping appraisal are proposed to be two cognitive processes that a person uses to deal with a threat [30]. Typically, a threat refers to something potentially dangerous and may cause physical or mental harm to a person. On the other hand, threat appraisal refers to the process of determining the severity and susceptibility of an identified threat [30]. PMT has been discussed in various areas, such as health [52,53,54], environment [55], and online security [51,56,57].

Mousavi et al. [30] applied PMT to explain social media users’ privacy protection behavior in privacy breaches. Their findings suggest that users’ threat assessments have a positive relationship with the motivation to protect their privacy. Chenoweth et al. [58] also applied PMT and proposed a research model to evaluate the intention to use anti-spyware software on undergraduate students. The findings revealed that students’ intention to use anti-spyware software was influenced by perceived vulnerability and severity. Fischer-Preßler et al. [59] validated PMT and proposed a model to explain the determinants behind individuals’ intention to install warning apps. Their findings showed that perceived vulnerability influenced the intention to use the apps. In higher education institutions, Hina et al. [60] discovered that perceived severity and perceived vulnerability positively influence the intention to comply with information security policies.

Ifinedo [61] adopted PMT to investigate employees’ intention to comply with information systems security policy. Their results showed that the perceived vulnerability positively influences the intention to comply. Using PMT, Lee [62] investigated factors influencing individuals’ anti-plagiarism software adoption. He discovered that the severity and vulnerability of the threat have a more significant effect on anti-plagiarism software adoption. Internet users face a variety of potential threats, necessitating the implementation of safety measures. PMT is a useful theory for analyzing Internet users’ security and information protection concerns [63,64]. Similar to online security protection, knowledge sharing by users in the OKC can be imitated or copied without the permission of knowledge owners, resulting in a loss of control of the knowledge and benefits associated with the knowledge [1]. Motivated by self-protection, users are inclined to evaluate threats related to knowledge sharing or knowledge hiding in OKCs. Thus, PMT is valuable and suitable for this study to examine factors influencing users’ knowledge hiding intention.

2.3. Self-Determination Theory

Self-determination theory (SDT), focused on a continuous and rapid strategy, organically proposed and developed the individuals’ behavioral principles within an inwardly consistent and concurrently supported conceptual framework. It has been adopted to test the behavioral phenomena of individuals in multiple fields through different methods and levels of analysis. Unquestionably, the theory’s origins can be traced back to its early explorations into intrinsic motivation [65,66,67] and the determinants that strengthen or weaken normal disposition.

Motivation is at the emotional core of people’s concerns: how to make themselves or others act. A person’s eagerness for a task can be either intrinsic or extrinsic, according to SDT [68]. Internal motivation originated from the conception that individuals have an inborn desire for autonomy, competence, and relatedness with other people or things [69]. Specifically, perceived autonomy relates to an individual’s desire to self-organize one’s conduct. Individuals are usually more inclined to change their behavior if they believe that change is consistent with their values, beliefs, and lifestyle [68,70,71]. Additionally, individuals with perceived competence are more likely to be effective and to be able to exert and expand their capabilities. It is possible to increase individual competence by providing feedback and teaching individuals the skills and tools they need [67]. Finally, perceived relatedness is a sense of belonging and a sense of being significant to others. Individuals are more likely to confirm the satisfaction of their psychological needs when relatedness is addressed. As a result, they are more likely to adhere to a recommended behavioral change [70,72].

SDT has been broadly discussed in information systems studies. Prior studies have examined intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from different perspectives in various research fields. According to Zhang et al. [73], determinants such as identified motivation, introjected motivation, and external motivation have crucial influences on users’ intention to evaluate online content collaboratively. Kelley and Alden [74] used SDT to examine the internalization of brand identity by its online community members through the interactivity of the brand website. Yoon and Rolland [75] adopted SDT and investigated knowledge sharing behaviors in virtual communities. They discovered that competence and relatedness affect knowledge sharing behaviors in virtual communities except for perceptions of autonomy. Gangire et al. [76] investigated and discussed information security behavior from the perspective of SDT.

This study assumes that different intrinsic motivational determinants are likely to mutually reinforce users’ knowledge hiding intentions in OKCs. We believe that exploring the consequences of various motivations within the integrated framework will provide more insights into the use of OKCs.

2.4. Social Exchange Beliefs

Social exchange emphasizes the conversational nature of giving and takes over the long term based on the principles of equity and reciprocity [77]. As a result, the depth and quality of the social interaction determine how the reciprocity norm operates in terms of knowledge hiding. Because knowledge hiding behaviors indicate a knowledge owner’s response to a knowledge seeker, they are controlled by the quality of the social relationship [78,79]. Thus, healthy and strong relationships foster mutual trust and respect among individuals [80], leading users to engage in positive reciprocity to promote knowledge sharing in their communities [28]. On the other hand, poor relationships can often result in negative reciprocity due to past displeasing experiences, escalating the probability of knowledge hiding among individuals [29,81]. The exchange of knowledge is typically conducted in a calculative manner [29,82]. Because increased opportunistic risks make knowledge owners more vulnerable, in OKCs where shared trust is absent, individuals will be more likely to conceal their knowledge.

The exchange of knowledge among members in OKCs is essential to the proper operation of the community. However, the nature of virtual space may present challenges in terms of information sharing and reduce opportunities for rich interactions among individuals, which may result in knowledge hiding. Nadeem et al. [46], as part of their investigation into knowledge hiding behavior in association with individuals’ shared goals and mutual trust, discovered that cognitive-based trust and affective-based trust negatively moderate the connection between individuals’ shared goals and knowledge hiding behavior. Staples and Webster [83] found that trust positively influenced knowledge sharing within the teams. In situations where the knowledge creators do not have confidence in the knowledge seekers, the contradiction between sharing and hiding knowledge may become more intense and squint towards knowledge hiding [84]. OKCs provide an affordance tool that supports the distribution and transfer of information and knowledge among individuals. Interpersonal interactions within OKCs act as a medium for increased knowledge sharing and improve knowledge accumulation [85]. Accordingly, integrating social exchange beliefs, this study proposes that the reciprocity received from OKCs and mutual trust among individuals could affect users’ knowledge hiding intentions.

3. Research Model and Hypotheses Development

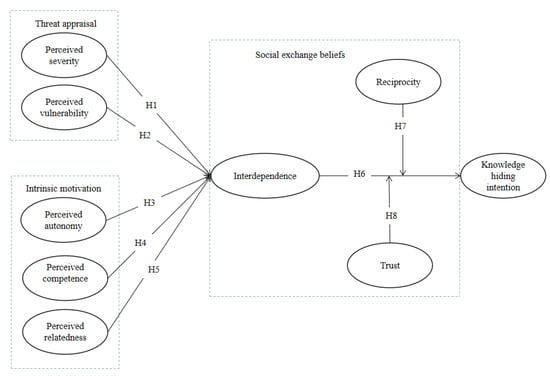

Using PMT, SDT, and social exchange beliefs, this study proposes an integrated framework to examine people’s knowledge hiding intentions in the OKC. We follow PMT and SDT to expect that appraisal of threat (perceived severity and perceived vulnerability) and intrinsic motivation (perceived autonomy, perceived competence, perceived relatedness) jointly affect users’ knowledge hiding intentions. Appraisal of the threat (perceived severity and perceived vulnerability) is proposed to influence users’ interdependence with others negatively. Furthermore, by adopting SDT, we posit that users’ intrinsic motivations (perceived competence, perceived autonomy, and perceived relatedness) are negatively associated with users’ interdependence with others. Additionally, we also explore the moderating effects of reciprocity and trust from the perspective of social exchange beliefs. These two factors are supposed to negatively moderate the relationship between interdependence within the OKC and individuals’ knowledge hiding intentions. Figure 1 shows the research model of this study.

Figure 1.

Research model.

3.1. Threat Appraisal and Interdependence

3.1.1. Perceived Severity and Interdependence

Perceived severity refers to the degree of physical, psychological, economic, or social harm from inappropriate behavior [86]. This study defines it as the perceived consequence of what might happen if individuals feel that they will be adversely affected by sharing knowledge with others in the OKC. Adverse consequences may include losing face, losing power, isolation, opportunism, exploitation, and contamination [87]. Based on the findings of Moorman and Blakely [88], Lee and Yan [89] proved that socially interdependent people strive for the group’s well-being even if it means sacrificing their interests. Interdependence within a group may determine the patterns of interaction between group members and the outcomes resulting from these patterns of interaction [90]. They believe that they should help others within a group and make more generous contributions, indicating that the viewpoint of interdependence stimulates greater social responsibility and collaboration with other members [89].

Knowledge hiding techniques may retain individuals’ relative importance to a group in the OKC [17]. Anaza and Nowlin [5] also indicated that knowledge hiding is a strategic form for protecting people’s competitive advantage. Since the purpose of knowledge hiding is to maintain people’s status of prestige and power, people are usually motivated to conceal knowledge strategically. The severity of the threat posed by knowledge sharing will increase as users grow, and information becomes more widespread and faster in cyberspace. According to Koay et al. [47], people may be hesitant to voluntarily share their knowledge with others since knowledge is perceived as a source of power and personal competitive advantage in the online community. Aside from that, people are usually motivated to keep a particular image when they are in the company of other people. Users who share uncertain or inappropriate knowledge on the Internet can be easily attracted to and mocked by other community members [1,7,47,87].

Furthermore, infringement of intellectual property is another critical problem in the virtual environment. Knowledge is susceptible to being misspent, and individuals’ knowledge-related benefits may be jeopardized [1]. Individuals tend to adjust their attitudes and behaviors when sharing personal knowledge would bring innumerable and severe potential threats. Ultimately, people will emphasize relationships, connectedness, and social context with others in the OKC. As a result, those with high perceived severity associated with knowledge sharing may be more likely not to rely on one another from the OKC. They may not be interested in communicating with others and exchanging knowledge through discussing specific issues. We thus hypothesize that perceived severity is negatively related to interdependence within the OKC.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Perceived severity is negatively related to interdependence within the online knowledge community.

3.1.2. Perceived Vulnerability and Interdependence

Perceived vulnerability has been defined as the conditional probability that individuals will experience harm [86]. It describes a person’s assessment of the likelihood of threatening events [51]. This study defined perceived vulnerability as the users’ evaluation of the probability of knowledge infringements. Previous studies in the information systems field also showed perceived vulnerability was an essential factor that motivated individuals to protect information [59,91,92]. When people perceive and measure a threat, they adjust their behavior according to the threat level and decide what to do in the next stage [52,54]. In addition to the severity of a specific threat, people also consider the possibility of the threat happening. The greater the perceived threats associated with knowledge sharing in the OKC, the easier it is for people to hide their knowledge.

This study proposes that the perceived vulnerability of losing personal knowledge is also a powerful determinant of users’ negative association with interdependence with others in the OKC. Perceived vulnerability can measure the expected costs if people share knowledge with others, which would decrease interdependent relationships. If OKC members’ private benefits were adversely affected by knowledge sharing behavior, they would be more motivated to manage their dependents and decrease community discussion. In other words, when individuals believe that it is easy to get themselves into trouble when losing individual knowledge, they intend to keep a distance from other members and hide their knowledge in the community. Thus, such reasoning leads to our second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Perceived vulnerability is negatively related to interdependence within the online knowledge community.

3.2. Intrinsic Motivation and Interdependence

3.2.1. Perceived Autonomy and Interdependence

Based on SDT, studies have shown that promoting autonomy, competence, and relatedness can lead to enhanced intrinsic motivation [34,76]. Kam et al. [34] proposed a research model by integrating flow theory with SDT. They found significant effects of perceived autonomy, perceived competence, and perceived relatedness on motivation for cybersecurity learning. Previous studies in knowledge management also proved these intrinsic motivations affect individuals’ knowledge sharing behavior in virtual communities [75]. In the OKC, perceived autonomy refers to the degree of individuals’ perception of their control over preferred solutions for protecting personal knowledge. SDT postulates that stronger perceived autonomy results in individuals’ self-determination [66].

To be more specific, individuals who perceive that they have the freedom to protect their knowledge in the OKC will internalize the protecting process [34,93], resulting in a stronger tendency to be isolated from other members and protect their knowledge. When individuals feel they have the right to avoid losing knowledge, they will naturally keep an estranged relationship with other members. In such estranged relationships, those individuals try to hide their knowledge when participating in online discussions. In other words, they have weak interdependence. By adopting SDT, Gangire et al. [76] conducted an information security behavior study. Their measurements can be applied to investigate how perceived competence, perceived relatedness, and perceived autonomy affect individuals’ intention to comply with information security protection. These reasons motivate this study to hypothesize a negative relationship between perceived autonomy and interdependence. Hence, this study proposes that individuals tend to have negative emotions in the OKC and avoid engaging in uncertain activities if they feel they have control over knowledge protection solutions. Thus, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Perceived autonomy is negatively related to interdependence within the online knowledge community.

3.2.2. Perceived Competence and Interdependence

Competence is the inherent human desire to understand a subject’s adequate understanding via completing challenging tasks [34]. This study defines perceived competence as individuals’ perceptions of their skills and abilities in protecting personal knowledge in the OKC [94]. Furthermore, perceived skills and abilities for protecting personal knowledge hinder individual behaviors, such as exchanging valuable knowledge that may benefit other members. Users with high perceived skill competence would hardly find other members as close partners when engaging in the OKC, which will result in decreased interdependence [95]. People with high perceived competence in the OKC may feel they have a better understanding of knowledge protection. They believe that they have effectively learned about knowledge protection in an online environment and can manage the requirements of learning more about knowledge protection. Motivational elements such as pleasant experiences carrying out one’s actions, the beneficial or undesired consequences, and personal beliefs or values usually influence individual behavior [76]. Therefore, this study suggests that when individuals believe they possess a high level of competence in protecting knowledge, they will be intrinsically motivated to rely less on other members to make decisions, thereby reducing interdependence. We thus propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Perceived competence is negatively related to interdependence within the online knowledge community.

3.2.3. Perceived Relatedness and Interdependence

The perceived relatedness of a situation, as described by SDT, is another intrinsic motivational element. The perceived relatedness is defined as individuals’ perceived emotional relationship with other people or objects [34,96]. In knowledge hiding, individuals are motivated to learn about knowledge protection solutions [33,34]. Individuals with a high perception of relatedness, such as a strong emotional attachment to certain people, things, or tasks, demonstrate a higher degree of internalization. When individuals have a sense of interconnectedness with their knowledge in the OKC, their motivation to protect knowledge is enhanced [93,96]. Individuals will believe that protecting their knowledge is a way to protect themselves [94].

Consequently, the increased perceived relatedness with personal knowledge will lead to a lower degree of dependence on others for benefits in the OKC. In other words, interdependence will be reduced [95]. Individuals who highly perceive interconnectedness with their knowledge may hide valuable knowledge and be less likely to depend on others to obtain their knowledge. Until now, few studies used SDT to explore knowledge hiding [42,44]. They investigated the role of motivation for knowledge sharing or hiding behavior and pointed out that both were differentially motivated. Based on previous studies, we argue that perceived relatedness to individuals’ knowledge is derived from the desire to protect their knowledge and is typically manifested through reduced interdependence with other members of the OKC. Accordingly, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Perceived relatedness is negatively related to interdependence with other members in the online knowledge community.

3.3. Interdependence and Knowledge Hiding Intention

Interdependence within a group refers to individuals’ behavioral engagement with the group where they belong [90,97]. In the OKC, users’ engagement is regarded as a critical theme because it emphasizes exchanging information and interaction between individuals [90]. In an OKC with high interdependence, members usually depend upon one another for knowledge seeking, decision making, information sharing, collaboration, and team decision-making [90,98]. Because people who place a high value on interdependence have innate motivations to be prosocial and be part of a community [89,99], they would be more likely to participate in a group for prosocial initiatives. This facilitates communication and cooperation, allowing for mutual adaptation between individuals who are acquiring and those being acquired [100]. Interdependence would represent cooperative relationships because it stresses the importance and value of joint effort, mutual achievement, and synergism among group members [83,101].

Group interdependence can also help increase and improve communication between group members and encourage supportive behavior. Group members take notice of the interests of their members with the addition of their interests [100]. Individuals who wish to maintain their competitive edge, on the other hand, believe that they are usually in a win–lose position in the group. When individuals attempt to maintain their competitive strength, they often feel that other group members intend to frustrate their plans and damage their interests, leading to lower interdependence [83,90,95,98,100,102]. Consequently, individuals become hesitant to share their knowledge. Lower interdependence within a group reduces the mutual sharing of information and may motivate individuals to engage in undesirable behaviors. Therefore, this study proposes that interdependence is supposed to be negatively related to knowledge hiding.

Hypotheses 6 (H6).

Interdependence with online knowledge community members is negatively related to users’ knowledge hiding intention.

3.4. The Moderating Role of Reciprocity and Trust

Knowledge sharing is facilitated by reciprocity, which is particularly prominent in the context of knowledge management. Reciprocity refers to a process in which each participant believes that they contribute to a common interest [103]. Reciprocal benefits play an influential role in influencing individuals’ actions in a social setting [104,105]. Reciprocity, which is affected mainly by exchanging knowledge and achieving personal goals, can be considered a strategic competency [106]. Creating and maintaining reciprocal benefits within a group can be regarded as a strategic competency as well. When individuals believe that their efforts to contribute knowledge will be recognized and repaid through reciprocation, they are more likely to contribute continuously [107]. According to Smedlund [108], reciprocal benefits enhance information sharing among community members by assuring knowledge owners that their efforts will be compensated in the future. Individuals who hold a more favorable attitude toward reciprocity are usually more likely to respond to beneficial treatment in a back-and-forth manner by providing benefits to other members in exchange for the reward [106,109]. These individuals generally believe that human beings are benevolent and trustworthy, and, as a result, they have a longer-term perspective on gains [110].

Furthermore, trust is another critical factor in the success of a group’s joint effort, effectiveness, and efficiency [46,111]. Trust among group members is essential in information exchange and transfer [112]. Trust is the expectation of an individual or a group that other individuals’ or groups’ statements, promises, words, or behavior can be relied on [113]. Practitioners indicate that trust improves the overall exchange of knowledge and makes it less expensive [46,114]. Mutual trust increases the likelihood that newly acquired knowledge will be accepted, understood, and used. Similarly, individuals can also share their knowledge when they have group trust [115]. Nadeem et al. [46] discussed trust from the perspectives of cognitive and affective dimensions. They proved that these two types of trust had moderating effects on the relationship between shared goals and employees’ knowledge hiding behavior. Thus, based on the above findings, we posit the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Reciprocity moderates the negative relationship between interdependence within the online knowledge community and individuals’ knowledge hiding intention.

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

Trust moderates the negative relationship between interdependence within the online knowledge community and individuals’ knowledge hiding intentions.

Interdependence and knowledge hiding intentions are more or less inversely related to reciprocity and trust.

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Measurement Items

This study developed and measured all constructs by referring to past studies and slightly modified the measurements to match our research context (see Appendix A Table A1). Firstly, we measured users’ threat appraisal of sharing knowledge [1] in the OKC and their intrinsic motivation to hide knowledge [94]. Secondly, users’ interdependence with other community members was measured with scales adopted from [95]. Thirdly, users’ knowledge hiding intentions in the OKC were measured with items developed from [1,46]. Lastly, reciprocity and trust were measured with items adapted from [106,116]. We applied the five-point Likert scale to measure the survey items. Scales range from one to five, in which one represents an inclination to strongly disagree with a statement, while five represents strongly agreeing with a statement. We analyzed the collected data in three steps. First, outliers, normality, and missing values were checked. Second, we evaluated the validity and reliability of the survey items. Third, we examined correlations between the constructs, tested the model fit, checked common method bias, and tested research hypotheses.

4.2. Data Collection

After extensively reviewing previous studies, we created the survey items and translated the original measurements into Chinese. Then, to keep the accuracy and consistency of the measurement items, we translated these items into English again, following the principle of back-translation. To conduct a pilot study first, we sent the questionnaire to a selected group of experts after it had been constructed. Then, we revised and optimized the questionnaire based on the experts’ suggestions. Next, we distributed survey questionnaires to registered users of Zhihu (http://www.zhihu.com/ accessed on 26 May 2021), a famous online knowledge community in China, and surveyed them during May~June 2021. In total, 426 questionnaires were received from the respondents. Among the 426 collected questionnaires, 49 were deemed invalid due to respondents’ incomplete responses, leaving a final valid sample of 377 from the registered users, resulting in a response rate of 88.5%. Table 2 shows the demographic information of the respondents.

Table 2.

Demographic information of the respondents.

5. Data Analysis and Results

This study adopted covariance-based SEM for analyzing the data. We evaluated the measurement model at first, and in the following step, the structural model was evaluated to test the research hypotheses.

5.1. Measurement Model

The construct validity, Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (CR), discriminant validity, and average variance extracted (AVE) values of the measurement model were checked to evaluate the measurement model. The results are summarized in Table 3, which shows that all values of standardized item loadings for the indicator were greater than 0.6. These are consistent with the reference value proposed by Fornell and Larcker [117]. Moreover, Cronbach’s alpha results were greater than 0.8, higher than the threshold value recommended by Hinkin [118]. Additionally, the results of the CR were greater than 0.8, which was higher than the threshold value. Finally, the average variance extracted (AVE) values used for assessing convergence validity were also greater than 0.5, larger than the threshold value suggested by Bagozzi and Yi [119]. To summarize, the results proved that all values met the minimum requirement, which suggested good validity and reliability of the data.

Table 3.

Construct validity, Cronbach’s α values, CR, and AVE.

For assessing the discriminant validity, we followed the rule that the square root of AVE should be larger than the correlation coefficients between one construct and other constructs. As shown in Table 4, the square root of AVE is higher than the intercorrelation coefficients among the variables, which indicates a good discriminant validity.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity test.

Podsakoff and Organ [120] and Podsakoff et al. [121] proposed that common method bias (CMB) may exist in single-source data. Thus, we used Harman’s one-factor statistical method to check the issue of CMB in the data that we collected. We performed exploratory factor analysis without rotation and checked to see if all of the factors had been returned to us. Previous studies suggested that if the total variance of one factor exceeds 50%, this indicates a problem with CMB. However, as shown in Table 5, the single factors explained 25.1% of the total variance in this study, which is less than 50%. Therefore, we can conclude that CMB does not exist in the data.

Table 5.

Common method bias test.

We checked actual values of model fitness to ensure the measurement model fit. Table 6 shows χ2/df, GFI (goodness-of-fit index), AGFI (adjusted goodness-of-fit index), NFI (normed fit index), CFI (comparative fit index), RMR (root-mean-square residual), and RMSEA (root-mean-square of approximation). All results are within the recommended ranges, which indicates a good model fit.

Table 6.

Measurement model fit.

5.2. Structural Model

In the next step, we assessed the structural model in the following section. Table 7 shows the standardized path coefficients for each hypothesis, the significance levels of the constructs, and the explanatory power of each construct. Generally, as an empirical law suggests, R2 indications of 75%, 50%, and 25% are regarded as considerable, average, and weak, respectively. As shown in Table 7, the proposed constructs explained 60.5% of the variance in interdependence and explained 41.1% of the variance in knowledge hiding intention, which indicates an acceptable degree of predictive accuracy and provides empirical evidence for the validity and sufficient effect size of the model.

Table 7.

Hypothesis test results.

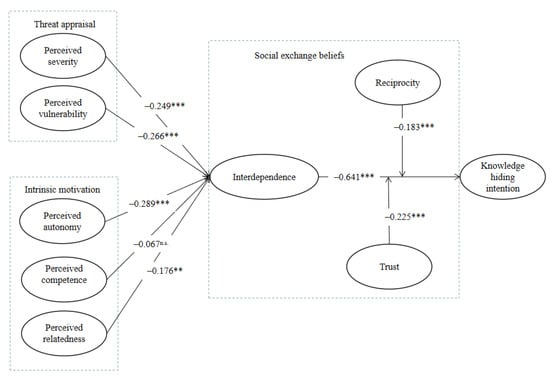

We evaluated the hypotheses by checking the significance of the corresponding path. It is suggested that the path is significant when the p-value is less than 0.05. As predicted by H1 to H6, perceived severity is negatively related to interdependence with a path coefficient of −0.249 (p < 0.001), and perceived vulnerability is also negatively related to interdependence with a path coefficient of −0.266 (p < 0.001), supporting H1 and H2. Furthermore, as expected, concerning intrinsic motivation, perceived autonomy negatively affects interdependence (β = −0.289, p < 0.001). Perceived relatedness negatively influences interdependence (β = −0.176, p < 0.01), supporting H3 and H5. However, perceived competence did not influence interdependence significantly; thus, H4 was not supported. In addition, interdependence negatively affected knowledge hiding intention (β = −0.641, p < 0.001), supporting H6.

Moreover, we hypothesized that reciprocity and trust play moderating roles between interdependence and knowledge hiding intention. As shown in Table 7, we can see that when reciprocity increases or decreases, interdependence and individuals’ knowledge hiding intention become more or less negatively related (β = −0.183, p < 0.001). Similarly, as to trust, when the degree of trust increases or decreases, interdependence and individuals’ knowledge hiding intention become more or less negatively related (β = −0.225, p < 0.001). Figure 2 shows the standardized path coefficients and the significance for each hypothesis.

Figure 2.

Path coefficients of the research model. Note: ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; n.s.= p > 0.05.

At last, we tested the mediating effect of interdependence. By including a third variable (i.e., mediator) in the basic linear regression model, mediation can be used to improve the research model’s performance. Therefore, we tested the mediating role of interdependence between the appraisal of threat (perceived severity and perceived vulnerability) and intrinsic motivation (perceived autonomy, perceived competence, and perceived relatedness), and knowledge hiding intention. To that end, this study adopted a bootstrapping approach. The indirect effects are shown in Table 8. The previous research suggests that the mediator is considered to have a mediating effect between X (independent variable) and Y (dependent variable) if the upper and lower confidence interval (95% CI) does not contain 0. The results indicated that interdependence within the OKC significantly mediates the relationship between perceived severity and knowledge hiding intention (β = 0.16). The mediating effect of interdependence within the OKC between perceived vulnerability and knowledge hiding intention is β = 0.17. In addition, the results also suggested that interdependence within the OKC significantly mediates the relationship between perceived autonomy and knowledge hiding intention (β = 0.185) and the relationship between perceived relatedness and knowledge hiding intention (β = 0.112). However, interdependence within the OKC does not mediate between perceived competence and knowledge hiding intention due to the LLCI and ULCI, including 0.

Table 8.

Mediating effect of interdependence.

6. Discussion

Knowledge hiding occurs prevalently in virtual spaces, such as in OKCs. This paper presented a novel research framework based on protection motivation theory, self-determination theory, and social exchange theory to examine the reasons behind knowledge hiding in the OKC. Specifically, by drawing on PMT and SDT, we shed light on the untapped relationship between individuals’ threat appraisal, intrinsic motivation, and interdependence in an OKC. Additionally, we also identified the moderating role of reciprocity and trust in reducing the negative effects of interdependence on knowledge hiding. As proposed, the results support all the hypotheses except for perceived competence. The results can be listed as follows: individuals’ threat appraisal and intrinsic motivation are negatively associated with interdependence. Additionally, we found that threat appraisal (perceived severity and perceived vulnerability) and intrinsic motivation (perceived autonomy and perceived relatedness) have strong explanatory power for interdependence.

Through comparing the path coefficients, we found that in terms of threat appraisal, perceived vulnerability (β = −0.266, p < 0.001) exerts more influence on interdependence within the OKC than perceived severity (β = −0.249, p < 0.001). Concerning intrinsic motivation, perceived autonomy (β = −0.289, p < 0.001) plays a more crucial role in determining interdependence within the OKC than perceived relatedness (β = −0.176, p < 0.01). However, perceived competence (β = −0.067, p > 0.05) does not affect interdependence within the OKC, inconsistent with the proposed hypothesis. One reason for explaining this result may be that perceived competence is the innate confidence and skill to perform protection behavior, which does not influence individuals’ decisions to engage in the OKC. Next, the results indicate that interdependence (β = −0.641, p < 0.001) is negatively associated with individuals’ knowledge hiding intentions.

This finding reveals that in an OKC with high interdependence, individuals may usually depend upon one another to obtain solutions and make decisions. Further, they need to communicate and interact with other members and exchange ideas more frequently, resulting in lower knowledge hiding levels. In addition, we also found that, with the increase in reciprocity (β = −0.183, p < 0.001) and trust (β = −0.225, p < 0.001) in the online knowledge community, individuals are less likely to hide their knowledge, consistent with the original hypotheses. In the OKC, individuals’ assessments of mutual reciprocal benefits and trust will make them less likely to hide knowledge. Overall, the results and findings of this study contribute to the knowledge hiding literature by demonstrating how individuals’ threat appraisal and intrinsic motivation impact knowledge hiding behavior in an online knowledge community.

Compared with the previous research, this study contributes to the knowledge management literature in the following several aspects. First, compared to extensive works discussing knowledge sharing, this study focuses on knowledge hiding. Most previous studies examined knowledge behaviors in organizations. However, in recent years, OKCs have become an essential source for exchanging and transferring knowledge. This study makes contributions to the limited research on counterproductive knowledge in online spaces. Second, by PMT, SDT, and social exchange beliefs, we simultaneously examined the threat appraisal and intrinsic motivation of knowledge hiding intention. This study is novel and meaningful in further investigating these psychological factors that could be the determinants of social activities in OKCs. Lastly, we found that social exchange beliefs (reciprocity and trust) significantly moderate the relationship between interdependence and knowledge hiding intention. This study could give researchers insights into more in-depth studies concerning counterproductive knowledge behaviors and provide OKC operators with further suggestions on the retention of OKC users and the transfer of their knowledge.

6.1. Academic Implications

This study makes several meaningful theoretical contributions to knowledge hiding research. First, unlike previous studies concerning productive knowledge behavior, such as knowledge sharing [32,75,122], we concentrate on the opposite side (i.e., counterproductive knowledge behavior) of knowledge management in the OKC. Thus, the findings enhance the understanding of the importance of knowledge hiding in the OKC. Second, knowledge hiding in organizations has been empirically examined [19,81,123]. However, this phenomenon has generally been left unexplored in virtual spaces [1] such as OKCs. To address this research gap, we established an integrated research model and provided empirical evidence to investigate the detrimental factors of knowledge hiding. Third, this study extended the work of knowledge hiding in the OKC. We showed that individuals’ threat appraisal and intrinsic motivation are crucial factors to knowledge hiding in the OKC. Fourth, interdependence in the online environment has been discussed in prior studies [89,90,95,98,102]. Based on these studies, we extended this concept and adopted it into the OKC. We examined and discussed the mediating effect of interdependence within the OKC. The empirical results indicate a mediating effect between online knowledge community users’ threat appraisal, intrinsic motivation, and knowledge hiding intention. Lastly, this study explored how reciprocity and trust moderated the relationship between interdependence and individuals’ knowledge hiding intention, ignored in previous literature. The empirical results revealed that the higher the reciprocity and trust, the stronger the negative relationship between interdependence and individuals’ knowledge hiding intention. Reciprocity and trust contain beliefs that OKC users (exchangers) are motivated by looking for mutual benefits and reliability. Interdependence debilitates the knowledge hiding intention in the OKC and is substantially formulated on the level of reciprocal benefits and trust through which community members give to each other.

6.2. Managerial Implications

Additional to theoretical implications, this study also provides several managerial implications for OKC operators. Knowledge hiding is one of the counterproductive knowledge behaviors that gravely obstructs the development of the OKC and blocks the exchange, spread, and conglomeration of knowledge. It is of great significance to explore and identify users’ knowledge hiding intentions in the OKC.

First, in this study, concerning threat appraisal, perceived severity and perceived vulnerability had been proved to have significant negative effects on interdependence, which indicated that OKC users usually associate negative results with knowledge sharing without hiding. Viewed in this way, OKC operators should find solutions to lower users’ anxieties when sharing their knowledge in the community. For example, an OKC operator could establish intellectual property protection regulations and policies to benefit both the community and users. Furthermore, OKC operators should develop a mechanism to give full protection to users’ personal information. Second, community users’ intrinsic motivation (perceived autonomy and perceived relatedness) has been proved to have a significant negative effect on interdependence, which suggests that OKC users are motivated to protect their knowledge while visiting the community. One possible reason for their greater motivation to protect their knowledge in the community could be their multi-faceted sense of accountability. In this sense, another feasible way to reduce knowledge hiding in the OKC is to give rewards or incentives (e.g., economic rewards, points) to users who share their knowledge. Third, the empirical results also reveal that interdependence is negatively related to knowledge hiding intention. Hence, OKC operators could consider interdependence an essential and novel community design attribute to elevate users’ engagement. These strategies are also feasible since various groups involving interdependence are available in the online knowledge community. For instance, operators can establish group-based missions that could focus on group achievement to promote interdependence within the community. In addition, operators could also distribute missions that stimulate users to cooperate with other community members. Finally, because reciprocity and trust moderate the relationship between interdependence and knowledge hiding intention, OKC operators might create a contribution mechanism to the users’ perceived reciprocity and generate reciprocal advantages within the community (e.g., by activating the question and answer function of the forum). To reinforce trust within the community, operators could adopt a system based on users’ certification, community use patterns, experience, and personal characteristics. The high and low ranking of the users is a way to identify their reliability in the community.

7. Research Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

Even though this study provided contributions to the existing body of research on knowledge hiding and contributed to online knowledge community management, it has some limitations, which give recommendations and opportunities for future studies. First, we did not measure all the constructs from protection motivation theory and self-determination theory. For instance, we only measured threat appraisal from protection motivation theory and intrinsic motivation from self-determination theory. It is worth investigating knowledge hiding behavior by integrating other constructs of these theories. Second, the survey respondents were from China. There must be cultural differences if conducting comparative studies. Constructs such as reciprocity and trust are supposed to be measured differently in western cultures. Third, personality traits (e.g., extraversion, openness, neuroticism, conscientiousness, agreeableness) could also be considered for future studies. Finally, Connelly et al. [28] pointed out that knowledge hiding can be divided into three types: evasive hiding, rationalized hiding, and playing dumb. However, our study did not discuss these knowledge hiding types separately. Instead, we focused on individuals’ general knowledge hiding intentions. These three types of knowledge hiding may have different antecedents, and individuals may evaluate them differently. Hence, future studies can distinguish and investigate different types of knowledge hiding.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.Y. and Y.-C.L.; methodology, Q.Y. and Y.-C.L.; software, Q.Y.; validation, Q.Y. and Y.-C.L.; formal analysis, Q.Y. and Y.-C.L.; investigation, Q.Y.; data curation, Q.Y. and Y.-C.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.Y.; writing—review and editing, Y.-C.L.; visualization, Q.Y. and Y.-C.L.; supervision, Y.-C.L. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. Data are not publicly available due to a confidentiality agreement with participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Questionnaire items.

Table A1.

Questionnaire items.

| Variables | Measurement Items | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived severity (PS) | Having someone successfully access all my knowledge is harmful to me. | [1] |

| The threats, uncertainties, and risks resulting from sharing knowledge in the OKC are harmful to me. | ||

| The abuse of my shared knowledge in the OKC by others is harmful to me. | ||

| Spreading my shared knowledge in the OKC without my permission is a serious problem for me. | ||

| Losing control of knowledge resulting from sharing knowledge in the OKC is a serious problem for me. | ||

| Perceived vulnerability (PV) | The likelihood that someone abuses my shared knowledge in the OKC is high. | [1] |

| The likelihood of suffering losses if I share all my knowledge in the OKC is high. | ||

| The likelihood of knowledge infringements in the OKC is high. | ||

| Perceived competence (PC) | I feel I have a better understanding of knowledge protection in the OKC. | [94] |

| I feel that I effectively learned about knowledge protection in the OKC. | ||

| I feel that I did a good job learning about knowledge protection in the OKC. | ||

| I feel that I can manage the requirements of learning more about knowledge protection in the OKC. | ||

| Perceived autonomy (PA) | Knowledge protection is what I would choose to do in the OKC. | [94] |

| I feel that protecting knowledge is an expression of my own preferences in the OKC. | ||

| I feel that the choice of protecting knowledge I am told to do fits perfectly with what I prefer to do in the OKC. | ||

| Perceived relatedness (PR) | I feel a strong connection with my knowledge. | [94] |

| If I lose control of my knowledge, I will be affected. | ||

| The thought of my knowledge being tampered with makes me anxious. | ||

| Protecting my knowledge is a way to protect myself. | ||

| Interdependence (IND) | My friends in the OKC and I depend on one another. | [95] |

| Usually, my friends in the OKC and I wait to see what others think before making decisions. | ||

| My friends in the OKC and I have a great deal of influence on one another. | ||

| My friends in the OKC and I often influence one another’s feelings towards the issues we are dealing with. | ||

| Reciprocity (REC) | I find that writing and commenting in the OKC can be mutually helpful. | [106] |

| When I share my knowledge through an OKC, I expect somebody to respond when I am in need. | ||

| When I share my knowledge through an OKC, I believe that my queries for knowledge will be answered in the future. | ||

| If I share my knowledge with other OKC members, I will make more friends. | ||

| Trust (TRU) | I can discuss with community members about my personal issues. | [116] |

| I know when I share my problems with a community member, he/she will respond constructively and caringly. | ||

| I know most of the members of this OKC will do everything within their capacity to help others. | ||

| I know most members of this community are honest. | ||

| Knowledge hiding intentions (KHI) | I would not transform personal knowledge and experience to other group members in the OKC. | [1,46] |

| I would try to hide new ideas from other group members in the OKC. | ||

| I would try to hide helpful information or knowledge from other group members in the OKC. |

References

- Wu, D. Empirical study of knowledge withholding in cyberspace: Integrating protection motivation theory and theory of reasoned behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 105, 106229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.H.; Chuang, S.-S. Social Capital and individual motivations on knowledge sharing: Participant involvement as a moderator. Inf. Manag. 2011, 48, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.C.-A.; Kang, T.-C. Reciprocal intention in knowledge seeking: Examining social exchange theory in an online professional community. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 48, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-C.; Huang, C.-C. Withholding effort in knowledge contribution: The role of social exchange and social cognitive on project teams. Inf. Manag. 2010, 47, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaza, N.A.; Nowlin, E.L. What’s mine is mine: A study of salesperson knowledge withholding & hoarding behavior. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 64, 14–24. [Google Scholar]

- Strik, N.P.; Hamstra, M.R.W.; Segers, M.S. Antecedents of Knowledge Withholding: A Systematic Review & Integrative Framework. Group Organ Manag. 2021, 46, 223–251. [Google Scholar]

- Jha, J.K.; Varkkey, B. Are you a cistern or a channel? Exploring factors triggering knowledge-hiding behavior at the workplace: Evidence from the Indian R&D professionals. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 824–849. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, X.-L.; Li, Y.-J.; Sun, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, F. Knowledge withholding in online knowledge spaces: Social deviance behavior and secondary control perspective. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2019, 70, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.M.; Behravesh, E.; Rezapouraghdam, H.; Yildiz, S.B. Applying artificial intelligence technique to predict knowledge hiding behavior. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 49, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vaio, A.; Palladino, R.; Pezzi, A.; Kalisz, D.E. The role of digital innovation in knowledge management systems: A systematic literature review. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.S.; Lin, H.H.; Li, C.R.; Lin, S.J. What drives students’ knowledge-withholding intention in management education? An empirical study in Taiwan. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2014, 13, 547–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Zhang, Q.; Teo, T.S.; Lim, V.K. The dark triad and knowledge hiding. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 42, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, C.E.; Černe, M.; Dysvik, A.; Škerlavaj, M. Understanding knowledge hiding in organizations. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 779–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K. Territoriality, task performance, and workplace deviance: Empirical evidence on role of knowledge hiding. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 97, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škerlavaj, M.; Connelly, C.E.; Cerne, M.; Dysvik, A. Tell me if you can: Time pressure, prosocial motivation, perspective taking, and knowledge hiding. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 1489–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernaus, T.; Cerne, M.; Connelly, C.; Vokic, N.P.; Škerlavaj, M. Evasive knowledge hiding in academia: When competitive individuals are asked to collaborate. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 597–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Han, M.S.; Xiang, D.; Hampson, D.P. The double-edged effects of perceived knowledge hiding: Empirical evidence from the sales context. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 23, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Chen, T.; Wang, M.; Jin, Y.; Wang, Y. Rivals or allies: How performance-prove goal orientation influences knowledge hiding. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 849–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H. Why and when do people hide knowledge? J. Knowl. Manag. 2013, 17, 398–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Butt, A.S.; Ahmad, A.B. Are there any antecedents of top-down knowledge hiding in firms? Evidence from the United Arab Emirates. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 1605–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Button, S.B.; Mathieu, J.E.; Zajac, D.M. Goal orientation in organizational research: A conceptual and empirical foundation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1996, 67, 26–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, Y.W.; Choi, J.N. Knowledge management behavior and individual creativity: Goal orientations as antecedents and in-group social status as moderating contingency. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 813–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, R.; Gupta, V. Relationship of individual and organizational factors with knowledge hiding in IT sector organizations. Int. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2018, 7, 209–216. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, D.G.; Neugebauer, J.; Sassenberg, K.; Buder, J.; Hesse, F.W. Motivated shortcomings in explanation: The role of comparative self-evaluation and awareness of explanation recipient’s knowledge. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2013, 142, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serenko, A.; Bontis, N. Understanding counterproductive knowledge behavior: Antecedents and consequences of intra-organizational knowledge hiding. J. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 20, 1199–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michailova, S.; Husted, K. Knowledge-sharing hostility in Russian firms. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2003, 45, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labafi, S. Knowledge hiding as an obstacle of innovation in organizations a qualitative study of software industry. AD-Minister 2017, 30, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Connelly, C.E.; Zweig, D.; Webster, J.; Trougakos, J.P. Knowledge hiding in organizations. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 64–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Cooke, F.L. Why and when knowledge hiding in the workplace is harmful: A review of the literature and directions for future research in the Chinese context. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2019, 57, 470–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, R.; Chen, R.; Kim, D.J.; Chen, K. Effectiveness of privacy assurance mechanisms in users’ privacy protection on social networking sites from the perspective of protection motivation theory. Decis. Support Syst. 2020, 135, 113323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kimpe, L.; Walrave, M.; Verdegem, P.; Ponnet, K. What we think we know about cybersecurity: An investigation of the relationship between perceived knowledge, internet trust, and protection motivation in a cybercrime context. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coun, M.M.; Peters, P.C.; Blomme, R.R. ‘Let’s share!’ The mediating role of employees’ self-determination in the relationship between transformational and shared leadership and perceived knowledge sharing among peers. Eur. Manag. J. 2019, 37, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangire, Y.; Da Veiga, A.; Herselman, M. Assessing information security behaviour: A self-determination theory perspective. Inf. Comput. Secur. 2021. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kam, H.J.; Menard, P.; Ormond, D.; Crossler, R.E. Cultivating cybersecurity learning: An integration of self-determination and flow. Comput. Secur. 2020, 96, 101875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, K.F.; Tan, F.B. The mediating role of trust and commitment on members’ continuous knowledge sharing intention: A commitment-trust theory perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 35, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.W. Knowledge withholding: Psychological hindrance to the innovation diffusion within an organisation. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2016, 14, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, C.; Butera, F. Hidden profiles and concealed information: Strategic information sharing and use in group decision making. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2019, 35, 793–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anand, A.; Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R. Why should I share knowledge with others? A review-based framework on events leading to knowledge hiding. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2020, 33, 379–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoreva, V.; Wechtler, H. Exploring the consequences of knowledge hiding: An agency theory perspective. J. Manag. Psychol. 2020, 35, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issac, A.C.; Baral, R.; Bednall, T.C. What is not hidden about knowledge hiding: Deciphering the future research directions through a morphological analysis. Knowl. Process. Manag. 2021, 28, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siachou, E.; Trichina, E.; Papasolomou, I.; Sakka, G. Why do employees hide their knowledge and what are the consequences? A systematic literature review. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 135, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenius, M.; Hankonen, N.; Ravaja, N.; Haukkala, A. Why share expertise? A closer look at the quality of motivation to share or withhold knowledge. J. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 20, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.H.; Wang, Y.S. Investigating the effect of university students’ personality traits on knowledge withholding intention: A multi-theory perspective. Int. J. Inf. Educ. Technol. 2012, 2, 354–357. [Google Scholar]

- Gagné, M.; Tian, A.W.; Soo, C.; Zhang, B.; Ho, K.S.B.; Hosszu, K. Different motivations for knowledge sharing and hiding: The role of motivating work design. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 783–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirkasimoglu, N. Knowledge Hiding in Academia: Is Personality a Key Factor? Int. J. High. Educ. 2016, 5, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.A.; Liu, Z.; Ghani, U.; Younis, A.; Xu, Y. Impact of shared goals on knowledge hiding behavior: The moderating role of trust. Manag. Decis. 2020, 59, 1312–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koay, K.Y.; Sandhu, M.S.; Tjiptono, F.; Watabe, M. Understanding employees’ knowledge hiding behaviour: The moderating role of market culture. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2020, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, V.; Mohiya, M. Share or hide? Investigating positive and negative employee intentions and organizational support in the context of knowledge sharing and hiding. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 129, 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.K.; Chakraborty, S. Knowledge withholding within an organization: The psychological resistance to knowledge sharing linking with territoriality. J. Innov. Sustain. 2018, 9, 94–108. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, R.W. A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change. J. Psychol. 1975, 91, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meso, P.; Ding, Y.; Xu, S. Applying protection motivation theory to information security training for college students. J. Inf. Secur. Priv. 2013, 9, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Han, X.; Zhang, X.; Dang, Y.; Chen, C. Investigating m-health acceptance from a protection motivation theory perspective: Gender and age differences. Telemed. e-Health 2015, 21, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Liu-Lastres, B.; Ritchie, B.W.; Mills, D.J. Travellers’ self-protections against health risks: An application of the full Protection Motivation Theory. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 78, 102743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. Mobile health service adoption in China: Integration of theory of planned behavior, protection motivation theory and personal health differences. Online Inf. Rev. 2019, 44, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, W.; Kang, S.; Song, H. Applying protection motivation theory to understand international tourists’ behavioural intentions under the threat of air pollution: A case of Beijing, China. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 2027–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, A.C.; Warkentin, M. Fear appeals and information security behaviors: An empirical study. MIS Q. 2010, 34, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boss, S.R.; Galletta, D.F.; Lowry, P.B.; Moody, G.D.; Polak, P. What do systems users have to fear? Using fear appeals to engender threats and fear that motivate protective security behaviors. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 837–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chenoweth, T.; Minch, R.; Gattiker, T. Application of protection motivation theory to adoption of protective technologies. In Proceedings of the 42nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2009; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer-Preßler, D.; Bonaretti, D.; Fischbach, K. A Protection-Motivation Perspective to Explain Intention to Use and Continue to Use Mobile Warning Systems. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hina, S.; Selvam, D.D.D.P.; Lowry, P.B. Institutional governance and protection motivation: Theoretical insights into shaping employees’ security compliance behavior in higher education institutions in the developing world. Comput. Secur. 2019, 87, 101594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifinedo, P. Understanding information systems security policy compliance: An integration of the theory of planned behavior and the protection motivation theory. Comput. Secur. 2012, 31, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. Understanding anti-plagiarism software adoption: An extended protection motivation theory perspective. Decis. Support Syst. 2011, 50, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkijika, S.F. Understanding smartphone security behaviors: An extension of the protection motivation theory with anticipated regret. Comput. Secur. 2018, 77, 860–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menard, P.; Bott, G.J.; Crossler, R.E. User motivations in protecting information security: Protection motivation theory versus self-determination theory. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2017, 34, 1203–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Cascio, W.F.; Krusell, J. Cognitive evaluation theory and some comments on the Calder and Staw critique. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1975, 31, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination theory: When mind mediates behavior. J. Mind Behav. 1980, 1, 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The empirical exploration of intrinsic motivational processes. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 13, 39–80. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Can. Psychol. 2008, 49, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, E.J. Using self-determination theory to identify organizational interventions to support coal mineworkers’ dust-reducing practices. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2019, 29, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]