Abstract

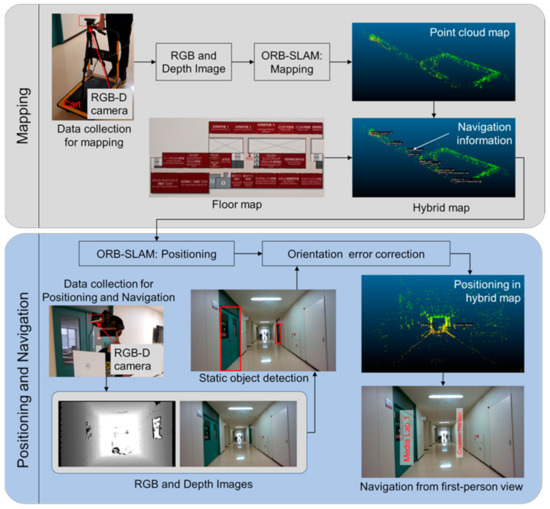

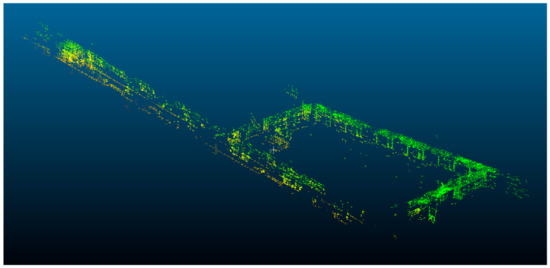

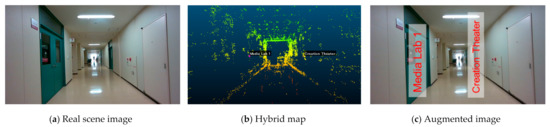

Current pedestrian navigation applications have been developed for the smartphone platform and guide users on a 2D top view map. The Augmented Reality (AR)-based navigation from the first-person view could provide a new experience for pedestrians compared to the current navigation. This research proposes a marker free system for AR-based indoor navigation. The proposed system adopts the RGB-D camera to observe the surrounding environment and builds a point cloud map using Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) technology. After that, a hybrid map is developed by integrating the point cloud map and a floor map. Finally, positioning and navigation are performed on the proposed hybrid map. In order to visualize the augmented navigation information on the real scene seamlessly, this research proposes an orientation error correction method to improve the correctness of navigation. The experimental results indicated that the proposed system could provide first-person view navigation with satisfactory performance. In addition, compared to the baseline without any error correction, the navigation system with the orientation error correction method achieved significantly better performance. The proposed system is developed for the smart glasses and can be used as a touring tool.

1. Introduction

In recent years, pedestrian navigation has become one of the most important services in people’s city lives. Now, people are increasingly turning to their mobile phones for maps and directions when on the go [1]. As the smartphone is still the most widely used portable device, the current pedestrian navigation applications have been developed for the smartphone platform and guide users from the 2D top view map. However, with the development of smart glasses, more and more scientists and engineers started to move their attention to Augmented Reality (AR)-based navigation from the traditional top view-based navigation [2,3,4]. In the AR-based navigation system, the navigation information is integrated with the real scene and visualized from the first-person view. The convenience and reality can be drastically improved in the AR-based navigation compared to the current navigation apps and using paper maps [5]. In addition, most of the pedestrian navigation applications are developed for outdoor navigation, there are few systems that can be used for an indoor environment. This paper proposes an AR-based navigation system for an indoor environment.

The quality of the navigation service highly depends on the accuracy of the positioning. Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) is the most developed positioning system in the world and it is widely applied in outdoor navigation. However, GNSS does not work very well inside a building because the structures interfere with the signal [6]. Considering the available sensors in the current smart devices, Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, Pedestrian Dead Reckoning (PDR), and camera are possible solutions for the indoor positioning and navigation.

Wi-Fi-based method is a popular choice for indoor positioning. With communication technology advancing with every passing moment, the Wi-Fi access points, whether it be a public or private network, are increasing rapidly. On top of having more access points (APs), portable Wi-Fi chips are found on most daily driver consumer electronics, for example smartphones, portable music players, smartwatches, smart glasses, or other smart devices [7]. There are two main groups of Wi-Fi positioning methods: fingerprint-based method and trilateration-based method. Fingerprint-based method needs to create a radio map of many calibration points in the offline phase. Positioning is conducted by estimating the similarity between the received Wi-Fi fingerprint and the fingerprint pre-stored in the radio map [8,9]. The more accurate positions of the calibration points in the radio map allow the benefit of better positioning results [10]. The trilateration-based method works well in a line-of-sight environment [11], and the accurate location information of each AP is needed [12]. Both approaches have similar problems. It is very time-consuming to create a high-quality Wi-Fi access point database and fingerprint database.

Bluetooth is also another possible solution; similar to the Wi-Fi approach, there are many devices capable of receiving Bluetooth. Compared to the Wi-Fi method, Bluetooth beacons used less power [13], but they are not so widely deployed as Wi-Fi routers. Moreover, the access point database or fingerprint database are also needed in the Bluetooth-based methods.

Another popular method is Pedestrian Dead Reckoning (PDR), a localization method for calculating current position by referencing previously known location, speed, and facing direction [14]. Nowadays, almost everyone carries a smartphone and most of the smartphones are equipped with a wide array of sensors including a gyroscope, accelerometer and magnetometer which made it possible to estimate the facing direction and walking speed. However, PDR needs a starting point to initialize its position update process and also suffers from an error accumulation problem [15]. In addition, the three categories of positioning methods, Wi-Fi, Bluetooth and PDR, have insufficient localization or orientation accuracy for AR-based navigation.

As the price of camera sensors has been declining in recent years, vision-based positioning methods are becoming more and more popular. There are two main categories in a visual-based positioning and navigation system: marker-based and marker-free systems. Marker-based indoor positioning and navigation system works by placing a marker that can be recognized by the system to get the current position. The marker could be anything as long as the system could recognize it. One example of such a system is from research conducted by Sato [16]. The system proposed by Sato works by placing various AR markers either on the floor or wall all over the building. Each marker is a unique marker and localization can be done by scanning the marker. To overcome the limits on the number of distinct markers, Chawathe proposed to use a sequence of recently seen markers to determine locations [17]. Mulloni et al. demonstrated that marker-based navigation is easier to use than conventional mobile digital maps [18].

Romli et al. proposed an AR navigation for the smart campus [19]. The developed system used AR markers to guide users inside the library by providing the right direction and information instantly. Hartmann et al. proposed an indoor 3D position tracking system by integrating an Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) and marker-based video tracking system [20]. The 3D position, velocity and attitude are calculated from IMU measurements and aided by using position corrections from the marker-based video tracking system. Koch et al. proposed to use the indoor natural markers already available on site, such as exit signs, fire extinguisher location signs, and appliance labels for supporting AR-based navigation and maintenance instructions [21]. Overall, the advantage of a marker-based navigation system is that since the marker is placed either systematically or at the known position, the system could easily perform localization. The disadvantage of the marker-based navigation systems is that the preparation and maintenance of markers are required. In some cases, real-time localization is not possible because the localization is dependent on the visibility of markers.

Another category is the marker-free vision-based positioning and navigation system. In contrast to the marker-based positioning and navigation system mentioned previously, the marker-free approach does not require setting up the marker in the building. This simplifies the complexity of preparation or maintenance when the positioning and navigation system is deployed in a large-scale building. Several successful examples can be found for outdoor navigation, and these systems prefer to conduct the positioning and navigation in a pre-prepared street view image database. Robertson et al. developed a system using a database of views of building facades to determine the pose of a query view provided by the user at an unknown position [22]. Zamir et al. used 100,000 Google Maps Street View images as the map and developed a voting-based positioning method, in which the positioning result is supported by the confidence of localization in the neighboring area [23]. Kim et al. addressed the problem of discovering features that are useful for recognizing a place depicted in a query image by using a large database of geotagged images at a city-scale [24].

Torii et al. formulated image-based localization problem as a regression on an image graph with images as nodes and edges connecting nearby panoramic Google Street View images [25]. In their research, the query image is also a panoramic image with a 360-degree view angle. Sadeghi et al. proposed to find the two best matches of the query view from the Google Street View database and detect the common features among the best matches and the query view [26]. The localization was considered as a two-stage problem: estimating the world coordinate of the common feature and then calculating the fine location of the query. Yu et al. built a coarse-to-fine positioning system, namely a topological place recognition process and then a metric pose estimation by local bundle adjustment [27]. In order to avoid discrete localization problems in the Google Street View based localization, Yu et al. further proposed to virtually synthesize the augmented Street View data and render a smooth and metric localization [28]. However, there is not a pre-prepared geotagged image database for most of the indoor environments.

In addition, there are a few discussions for AR-based navigation. Mulloni et al. investigated user experiences when using AR as a new aid to navigation [29]. Their results suggested that navigation support will be most needed in the proximity of road intersections. Katz et al. proposed a stereo-vision-based navigation system for the visually impaired [30]. The proposed system can detect the important geo-located objects, and guide the user to his or her desired destination through spatialized semantic audio rendering. Hile et al. proposed a landmark-based navigation system for smartphones, which is the pioneer for AR-based pedestrian navigation [31]. In addition, Hile et al. pointed out that it is necessary to reduce the positioning error and provides accurate camera pose information for the more realistic visualization of arrows in the navigation [32].

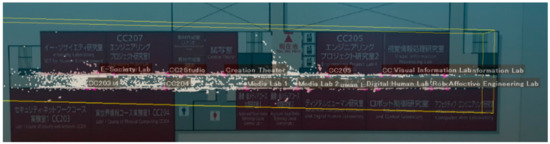

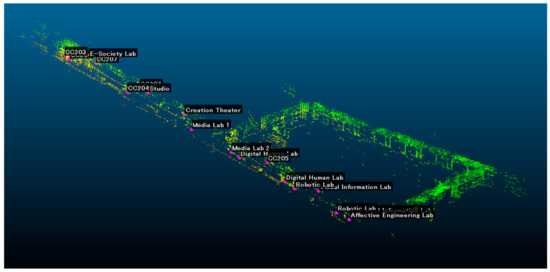

The first contribution of this paper is to propose a marker-free system for AR-based indoor navigation. The Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) method is a famous vision-based positioning method. It can accurately estimate the position and orientation of the vision sensor [33,34]. However, SLAM is still a positioning method, it cannot provide the navigation information directly for users. This research proposes an AR navigation system using SLAM to create a point cloud map which then will be integrated with a floor map to create a hybrid map containing a point cloud map of the indoor environment and navigation information on the floor map such as the position of doors and the name of rooms. The proposed AR navigation system performs positioning and navigation in this proposed hybrid map.

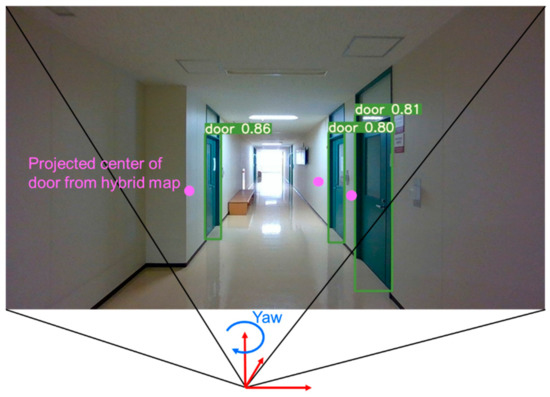

The second contribution is to propose an error correction method to improve the accuracy of the estimated camera orientation which is needed to visualize the augmented navigation information on the real scene correctly. It is observed in the feasibility step of this research that the estimated camera orientation from SLAM is not always correct. The orientation error is the reason for the incorrect navigation. To correct orientation error, a deep learning based real-time object detector You Only Look Once, or YOLO, developed by Redmon et al. [35] is used to detect the static objects, such as the door of a room. The error correction is conducted by minimizing the position difference between the detected doors from the image and the projected doors from the hybrid map.

The conception of using SLAM and floor map for AR-based navigation has been presented in our previous paper [36]. This paper extends the initial results and newly proposes the orientation error correction to further improve the performance of the navigation system. This paper is a summary of the undergraduate research of the first author [37].

3. Experiments

3.1. Experiment Setup

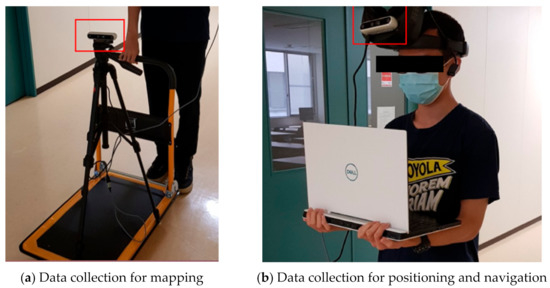

In this research, an Intel Real Sense D455 RGB-D camera was used. In the experiment, RGB image and depth image are captured synchronously; the resolution of RGB and depth image is 1280 × 720 pixels. The images are recorded at 30 frames per second (FPS). As shown in Figure 9a, the camera attached to a tripod was setup on a cart in the mapping step. The camera on a cart ensures a stable image sequence to provide the best point cloud map generation quality. In addition, data used for position and navigation are collected by placing the camera on the forehead as shown in Figure 9b. This can simulate actual usage with unstable motion when the user is moving and wearing smart glasses.

Figure 9.

Data collection for mapping step (a), positioning and navigation step (b).

3.2. Experiment Result of Room Information Visualization

To evaluate the quality of the navigation, this research conducted a series of experiments in the corridor of a largescale building. Table 1 shows the comparison between different methods with or without orientation error correction. The value offset refers to the pixel offset from the center of the visualized label to the centerline of the door in image. In addition, the evaluation also considers in how many instances the center of the navigation information label is placed in the area of the door. As shown in Table 1, orientation error correction significantly improved the performance of the system. The average offset is reduced to 15 pixels by using the method with orientation error correction. Moreover, the room name can be correctly visualized within the door area in 81.82% of frames if the orientation error correction is used.

Table 1.

Comparison of visualization correctness in navigation.

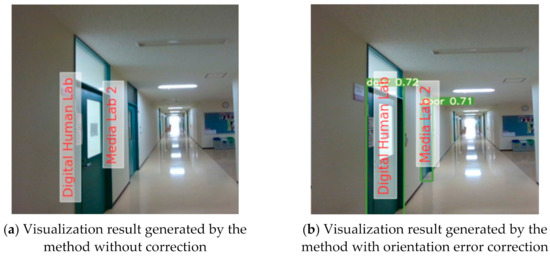

Several experiment results are demonstrated in Figure 10; the orientation value obtained from ORB-SLAM in this specific image is already correct. There is not so much difference between the visualization results generated by methods without correction (Figure 10a) and with orientation error correction (Figure 10b).

Figure 10.

Visualization of navigation information is correct in both the method without correction (a) and the method with orientation error correction (b).

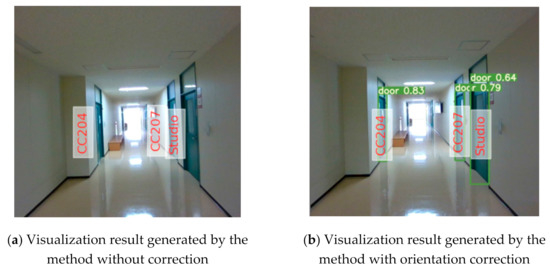

In Figure 11, the orientation obtained from ORB-SLAM in this image is incorrect. This error causes the navigation label augmented in the baseline method to also be incorrect (in Figure 11a, navigation labels are augmented outside the door area). In this scenario, the orientation error correction method works and performs better than the baseline method. The room name is correctly visualized at the door area (Figure 11b).

Figure 11.

Visualization of navigation information is incorrect in the method without correction (a), but correct in the method with orientation error correction (b).

3.3. Experiment Result of Navigation Arrow Visualization

In addition to the room name, the proposed system also can visualize a direction arrow for navigation. As for navigation arrow augmentation, the system achieved 99% accuracy in the test. For example, the room called “Studio” was set as a target for navigation. On the left, the studio room is not within augmentation range, therefore the forward arrow is augmented on the image. In the middle of Figure 12, the studio room is within the augmentation range and is estimated to be on the right side of the camera, therefore, the right navigation arrow is augmented. On the right of Figure 12 when studio room is immediately outside the image, the backward navigation arrow is augmented.

Figure 12.

Different augmented navigation arrows visualized in the navigation to a destination “Studio”. Left: the destination is in front but not within the augmentation range. Middle: the destination is on the right side of the user. Right: The user has passed the destination.

4. Discussion

The proposed orientation error correction can improve the correctness of the visualization of the navigation information on the real scene image. The orientation error correction function works when the reference objects (the door of the room in this paper) appear in the image. The proposed system utilizes ORB-SLAM for mapping and positioning. ORB-SLAM focuses on building globally consistent maps for reliable and long-term localization in a wide range of environments as demonstrated in the experiments of the original ORB-SLAM paper [33]. The original paper of ORB-SLAM provides the evaluation for the accuracy of ORB-SLAM for RGB-D sequence. In our experiment, the whole floor of the laboratory’s building is successfully mapped. The area of the floor is about 100 by 30 m, so it is reasonable to say that the current system can work in such a scale area.

However, the proposed system has some limitations. The process of extracting navigation information is a manual process that requires an accurately scaled floor map. Automatic navigation extraction from the floor map is one significant area for improving the system. Furthermore, for a large-scale area, position initialization could take a significant amount of time. For a seamless AR experience, another positioning method (e.g., Wi-Fi-based positioning) could be one of the possible solutions to speed up the position initialization process.

The proposed AR-based navigation system is demonstrated in a classroom building scenario and it can be applied in other environments, such as shopping malls and museums. In addition, if this standalone system is connected to the internet, and the owner of the system shares the tour with others, the proposed system will become a virtual tour tool. The proposed system can visualize both the real scene and the augmented information, which will improve the experience for remote users. Moreover, the audio augmented reality can be added to the proposed system devoted to visually impaired people.

5. Conclusions

This research proposed an AR-based indoor navigation system. The proposed system adopts the RGB-D camera to observe the surrounding environment and relies on ORB-SLAM for mapping and positioning. In addition, this research proposed a hybrid map created from a combination of a point cloud map generated by ORB-SLAM and a floor map. The proposed hybrid map can be used for both navigation and positioning. Furthermore, to improve the correctness of navigation, an orientation error correction method was proposed. The proposed method corrects orientation error by finding the optimum rotation matrix that results in the lowest average offset from the position of projected objects to the center of detected objects. The proposed orientation error correction method achieved an average offset of about 15 pixels and 81.82% of navigation labels are augmented within the boundary of door. The navigation arrow augmentation achieved a very high accuracy of 99%. The experimental results indicated that the current SLAM technology still needs improvement for providing correct navigation information. This study presents an example of using the object detection-aided orientation error estimation method to correct the orientation error and correctly visualize navigation information. The proposed AR-based navigation system can provide first-person view navigation with satisfactory performance. In the future, the proposed system will be improved for adaptation to the shopping mall environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.G.; methodology, Y.G. and W.C.; software, W.C. and Y.G.; validation, W.C.; writing—original draft preparation, W.C. and Y.G.; writing—review and editing, W.C. and Y.G.; project administration, Y.G.; investigation, W.C., Y.G. and I.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ohm, C.; Bienk, S.; Kattenbeck, M.; Ludwig, B.; Müller, M. Towards Interfaces of Mobile Pedestrian Navigation Systems Adapted to the User’s Orientation Skills. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 2016, 26, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, A.; Burnett, G.; Large, D.R. An Investigation of Augmented Reality Presentations of Landmark-based Navigation using a Head-up Display. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Automotive User Interfaces and Interactive Vehicular Applications, Nottingham, UK, 1–3 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, B.C.; Hsu, J.; Chu, E.T.H.; Wu, H.M. ARBIN: Augmented Reality Based Indoor Navigation System. Sensors 2020, 20, 5890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Gu, Y.; Kamijo, S. Pedestrian Positioning in Urban City with the Aid of Google Maps Street View. In Proceedings of the 15th IAPR International Conference on Machine Vision Applications, Nagoya, Japan, 8–12 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, U.; Cao, S. Augmented-reality-based Indoor Navigation: A Comparative Analysis of Handheld Devices versus Google Glass. IEEE Trans. Hum. Mach. Syst. 2016, 47, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laoudias, C.; Moreira, A.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Wirola, L.; Fischione, C. A Survey of Enabling Technologies for Network Localization, Tracking, and Navigation. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2018, 20, 3607–3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaupel, T.; Seitz, J.; Kiefer, F.; Haimerl, S.; Thielecke, J. Wi-Fi Positioning: System Considerations and Device Calibration. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation, Zurich, Switzerland, 15–17 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, L.; Liu, J.; Guinness, R.; Chen, Y.; Kuusniemi, H.; Chen, R. Using LS-SVM based Motion Recognition for Smartphone Indoor Wireless Positioning. Sensors 2012, 5, 6155–6175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Gao, L.; Mao, S.; Pandey, S. CSI-based Fingerprinting for Indoor Localization: A Deep Learning Approach. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2017, 66, 763–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Hsu, L.T.; Gu, Y.; Wang, H.; Kamijo, S. Database Calibration for Outdoor Wi-Fi Positioning System. IEICE Trans. Fundam. Electron. Commun. Comput. Sci. 2016, 99, 1683–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguejiofor, O.S.; Aniedu, A.N.; Ejiofor, H.C.; Okolibe, A.U. Trilateration based Localization Algorithm for Wireless Sensor Network. Int. J. Sci. Mod. Eng. 2013, 10, 2319–6386. [Google Scholar]

- Mok, E.; Retscher, G. Location Determination using Wi-Fi Fingerprinting versus Wi-Fi Trilateration. J. Locat. Based Serv. 2017, 2, 145–159. [Google Scholar]

- Faragher, R.; Harle, R. An Analysis of the Accuracy of Bluetooth Low Energy for Indoor Positioning Applications. In Proceedings of the 27th International Technical Meeting of The Satellite Division of the Institute of Navigation, Tampa, FL, USA, 8–12 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, L.T.; Gu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Kamijo, S. Urban Pedestrian Navigation using Smartphone-based Dead Reckoning and 3-D Map-aided GNSS. IEEE Sens. J. 2016, 5, 1281–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Li, D.; Kamiya, Y.; Kamijo, S. Integration of Positioning and Activity Context Information for Lifelog in Urban City Area. J. Inst. Navig. 2020, 67, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, F. Indoor Navigation System based on Augmented Reality Markers. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Innovative Mobile and Internet Services in Ubiquitous Computing, Torino, Italy, 10–12 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chawathe, S.S. Marker-based Localizing for Indoor Navigation. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference, Bellevue, WA, USA, 30 September–3 October 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mulloni, A.; Wagner, D.; Barakonyi, I.; Schmalstieg, D. Indoor Positioning and Navigation with Camera Phones. IEEE Pervasive Comput. 2009, 8, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romli, R.; Razali, A.F.; Ghazali, N.H.; Hanin, N.A.; Ibrahim, S.Z. Mobile Augmented Reality (AR) Marker-based for Indoor Library Navigation. In Proceedings of the 1st International Symposium on Engineering and Technology 2019, Perlis, Malaysia, 23 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, B.; Link, N.; Trommer, G.F. Indoor 3D Position Estimation using Low-cost Inertial Sensors and Marker-based Video-Tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE/ION PLANS 2010, Indian Wells, CA, USA, 4–6 May 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, C.; Neges, M.; König, M.; Abramovici, M. Natural Markers for Augmented Reality-based Indoor Navigation and Facility Maintenance. Autom. Constr. 2014, 48, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, D.P.; Cipolla, R. An Image-Based System for Urban Navigation. In Proceedings of the 2004 British Machine Vision Conference, Kingston, UK, 7–9 September 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zamir, A.R.; Shah, M. Accurate Image Localization based on Google Maps Street View. In Proceedings of the 2010 European Conference on Computer Vision, Crete, Greece, 5–11 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.J.; Dunn, E.; Frahm, J.M. Predicting Good Features for Image Geo-Localization Using Per-Bundle VLAD. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Torii, A.; Sivic, J.; Pajdla, T. Visual Localization by Linear Combination of Image Descriptors. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops, Barcelona, Spain, 6–13 November 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi, H.; Valaee, S.; Shirani, S. 2DTriPnP: A Robust Two-Dimensional Method for Fine Visual Localization Using Google Streetview Database. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2017, 66, 4678–4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Joly, C.; Bresson, G.; Moutarde, F. Monocular Urban Localization using Street View. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 14th International Conference on Control Automation, Robotics and Vision, Phuket, Thailand, 13–15 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Joly, C.; Bresson, G.; Moutarde, F. Improving Robustness of Monocular Urban Localization using Augmented Street View. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 19th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1–4 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mulloni, A.; Seichter, H.; Schmalstieg, D. User Experiences with Augmented Reality aided Navigation on Phones. In Proceedings of the 10th IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality, Basel, Switzerland, 26–29 October 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, B.F.; Kammoun, S.; Parseihian, G.; Gutierrez, O.; Brilhault, A.; Auvray, M.; Truillet, P.; Denis, M.; Thorpe, S.; Jouffrais, C. NAVIG: Augmented Reality Guidance System for the Visually Impaired. Virtual Real. 2012, 16, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hile, H.; Vedantham, R.; Cuellar, G.; Liu, A.; Gelfand, N.; Grzeszczuk, R.; Borriello, G. Landmark-based Pedestrian Navigation from Collections of Geotagged Photos. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Mobile and Ubiquitous Multimedia, Umea, Sweden, 3–5 December 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hile, H.; Grzeszczuk, R.; Liu, A.; Vedantham, R.; Košecka, J.; Borriello, G. Landmark-based Pedestrian Navigation with Enhanced Spatial Reasoning. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on Pervasive Computing, Nara, Japan, 11–14 May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mur-Artal, R.; Tardós, J.D. ORB-SLAM2: An Open-Source SLAM System for Monocular, Stereo, and RGB-D Cameras. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2017, 33, 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, J.; Schöps, T.; Cremers, D. LSD-SLAM: Large-scale Direct Monocular SLAM. In Proceedings of the 2014 European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV2014), Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Y.; Chidsin, W.; Goncharenko, I. AR-based Navigation Using Hybrid Map. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 3rd Global Conference on Life Sciences and Technologies, Nara, Japan, 9–11 March 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chidsin, W. Augmented Reality-based Indoor Navigation Using SLAM and Hybrid Map Information. Undergraduate Thesis, Ritsumeikan University, Kyoto, Japan, 1 February 2021. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).