Abstract

This qualitative study describes the procedures undertaken to explore the Intangible Culture Heritage (ICH) preservation, especially focusing on the inhabitants’ garments of different ethnic groups in Weld Quay, Penang, which was a multi-cultural trading port during the 19th century in Malaysia. Social life and occupational activities of the different ethnic groups formed the two main spines of how different the inhabitants’ garments would be. This study developed and demonstrated a step-by-step conceptual framework of narrative analysis. Therefore, the procedures used in this study are adequate to serve as a guide for novice researchers who are interested in undertaking a narrative analysis study. Hence, the investigation of the material culture has been exemplified by proposing a novel conceptual framework of narrative analysis. This collaborative method has been utilized to ascertain the narrative data collected from an interview with visual and semiotic analysis. The information derived from the narrative interview is about the materials, colors, and elements of the garments of different ethnic groups (i.e., the Chinese, Indian, Malay and British). This collaborative process provides much valuable contextual and historical information to the researcher, as the interpretation and implicit understandings that underlie the stories people tell are beneficial in preserving and safeguarding this ICH. Therefore, this narrative study validates that the inhabitant’s garments are a means of intangible culture heritage (ICH) preservation and suggests guidance about how to conduct narrative analysis for mining historical data in a more explicit manner.

1. Introduction

The World Heritage List has included 1031 cultural and natural heritage sites, and these sites are considered to have extraordinary universal value [1]. Among the listed sites of heritage, Weld Quay in George Town, Penang, Malaysia, is one of the sites that have been awarded as a World Cultural Heritage Site by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) [2]. Weld Quay represented Penang’s heyday and used to be one of the most significant places in Penang [3]. It served as an entrepot for the Northern region of Malaya, Sumatera, Southern Thailand, and many more in the 19th century. It is also famous for the centers of historic and multi-cultural practices by various ethnic groups. However, Weld Quay is lacking proper documentation of its material culture, particularly the inhabitants’ garments in the early 19th century, although that time is considered as a golden era of Weld Quay’s development. There are two types of cultural heritage, namely the tangible and intangible heritage. Based on the ASEAN definition for cultural heritage, the structures, artefacts, and sites are considered tangible heritage, while the oral, folk, and popular cultural heritage including fashion and costumes and human habits are considered intangible cultural heritage (ICH) [4,5]. The Intergovernmental Committee also defined the Intangible Cultural Heritage as the element gives its practitioners a sense of identity and continuity, through the costumes, dances, and journey that they make; it is developed and passed on from generation to generation [6].

It is thus inherently needed to be preserved, as it is not always visible and liable to be forgotten. ICH is vital because it provides people with a sense of belonging and identity and its safeguarding often promotes cultural diversity and human creativity. Most remarkably, the 2003 Convention proclaimed that embracing and safeguarding ICH would be “a guarantee of sustainable development” [7,8,9]. At the same time, the policies of safeguarding ICH also protect and avoid the phenomenon of intolerance, to give treats of deterioration, disappearance, and destruction of the ICH [10,11]. The ICH protection endangers it from cultural globalization and social transformation and ensures the continuity of communities’ living heritage.

Reference [12] stated that the ICH is a fragile asset. Even if there is some information, that information is fragmented and not classified. Thus, the knowledge depends on individual practitioners, since no documentation is made [13]. According to UNESCO’s Lists of the 2003 Convention, Malaysia has five items of ICH that have been inscribed on the convention’s list out of almost 500 elements in the world. These heritage items include Silat, Dondang Sayang, Mak Yong Theatre, Pantun, Ong Chun/Wangchuan/Wangkang ceremony, rituals and related practices for maintaining the sustainable connection between man and the ocean [1]. However, there are none yet about material cultures, especially about the costumes and garments ICH nominated on the list for Malaysia. The connection between garments and the occupations of the inhabitants in Weld Quay are derived and simulated based on rudimentary knowledge in the work of [14]. Although there is a lack of proper information and preservation work of Weld Quay, safeguarding of the cultural heritage, especially the material culture, is very significant in today’s life for the intangible value [4,15]. Moreover, UNESCO lists WHSs as those that carry the Outstanding Universal Values (OUVs), meaning the significant cultural and/or natural values that carry educational elements for the future generations [16]. The third OUV criterion is that George Town has adopted the multicultural intangible heritage that manifests a great variety of ethnic quarters, religious festivals, dances, costumes, and ways of life [6]. Therefore, this narrative and visual analysis have been applied in this study to trace back the information of the inhabitants’ garments of Weld Quay in the older days to explore their social status as well as the traditional way of life.

The narrative analysis is a pervasive structure that comprehends and conveys the experiences and meanings of any events [17]. A narrative arises when one or more informants or interviewers are engaged in recounting and sharing life stories or experiences. The narrative analysis then uses the story as an important investigative key [18]. Narrative analysis is also pointed to various approaches such as data collection and data analysis that are useful for histories, humanities, and social science investigations [19,20,21].

Target 11.4 of the Sustainable Development Goal 11 (SDG 11) aims to “strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage” [22]. Additionally, in UNESCO-initiated conventions such as the UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage 2003 and UNESCO World Heritage Centre’s Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention 2015, the participation of the communities and individuals that create, maintain, and transmit such heritage is given much emphasis [23]. Thus, this study tried to enhance and articulate the method regarding in-depth investigation for the past and long-missing heritage, especially for the intangible items such as material culture. For instance, reference [24] also investigate Jugra, which was formerly an administrative center of Selangor State during the reign of the fourth Sultan of Selangor in the 18th century as a means of heritage conservation and preservation. The information regarding ICH is believed more difficult to obtain compared to the tangible items because intangible heritage is in mere form. It keeps modifying during the inheritance and transmission processes following the development of societies, cultures, and trends in every different era. Additionally, the preservation work of intangible heritage in the past is nearly impossible. Thus, the task of finding data on intangible culture heritage is challenging.

There is not a self-explanatory way of defining or understanding heritage. In the process of examine intangible heritage, this research also considered the authorized heritage discourse (ADH), which should involve participations of the local communities. The AHD is constructed to reinforce approved ideas of national identity. In addition, reference [25] proposed that assuredly taking critical discourse analysis and critical realism in sync could provide a guideline for heritage studies for the future developments, where myriad inkling of heritage can coincide. Smith also argued that heritage is not about the actual past, it is about constructing ideas of the past that serve present agendas [26]. Thus, it is crucial to link back to the local community, as they might have a different perception of the heritage we are investigating as compared to the expert informants [27].

Therefore, the objective of this paper is to explore appropriate information about inhabitants’ garments to interpret the Weld Quay site as one of the cultural heritage centers in the 19th century. Since this remarkable material culture of old Weld Quay has long gone, so this narrative analysis method has been selected to collect the data and information. An inquiry into the dynamic interpretation of “heritage” couched in the imperative to protect and to safeguard both tangible and intangible heritage is important in supporting the efforts toward conservation of heritage [28]. Two informants were invited to conduct the narrative interview. The collected data were analyzed using the narrative analysis method in terms of the past garments in Weld Quay. By comparing the narrative data with visual selected collection databases on this matter, the obtained information is then validated. Therefore, this study has contributed to the narrative analysis method by digging out the long-gone heritage data of material culture. The outcome provides a sense of identity, especially for the local community of Weld Quay today and continuity in a fast-changing world [29].

2. Narrative Analysis for Mining the Data of Material Culture

Narrative analysis is not only regarding what is said but also how it is said. The narrative interview is known as an in-depth investigation of specific features that exist in the life story of both the respondent and the reflection on the context of the situation. Many researchers have used a similar method for seeking the stories and certain context that they demand. This kind of interview is aimed to elicit and stimulate the informants to share their social stories and some important events [30,31,32]. In this study, through the narrative analysis, the material culture is aimed to be investigated is the garments of the inhabitants in the early 19th century at Weld Quay.

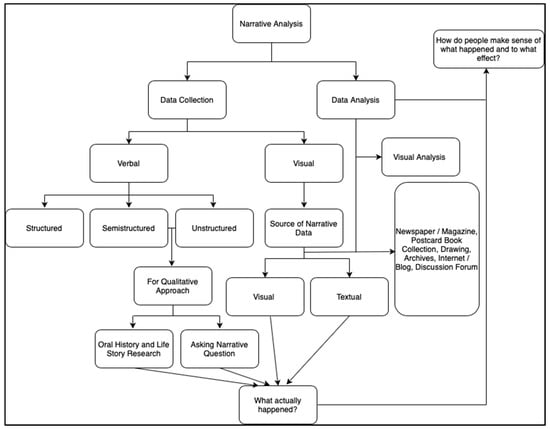

Data have been collected from the narrative interview using the narrative analysis method. Nevertheless, the narrative analysis does not only depend on the narrative interview data. Apart from the data from the interview, other narrative data have been collected from other sources and platforms, which are also considered as valid data in narrative analysis [33]. Both data collection and analysis of qualitative data are considered the procedure whereby people are engaged in ‘story telling’ or creating a ‘narrative account’ [34]. Narrative analysis is also considered as an approach that relied on the written or spoken words or visual representation of individuals [35]. Figure 1 shows the overall conceptual framework of narrative analysis in this paper.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of narrative analysis.

Two types of data were collected, which are verbal and visual data, and these data were generally emphasized in narrative research. In terms of verbal data, they consist of storytelling or narrative interviews. According to [36], narrative analysis can be adopted in the interview accounts, and then the narrative analysis can make use of the interview content as the investigative key. Narrative interviews can be in structured, semi-structured, and unstructured forms. In the case of histories or humanities research, reference [37] suggested that the semi-structured interview is the qualitative approach that is suitable to use in the research. A typical semi-structured interview involves narrative questions and a few pre-determined possible outcomes to prompt the conversation with guidance and to elicit a life story or to probe answers from the interviewee. This interview substantially provides much more freedom for interviewees to give answers on their terms than structured interviews [38].

Referring to [32], the objective of narrative analysis process is not only about what is said, but also how it is said. Even though the interview has already been firmly accounting as the research tool for narrative analysis, the other narrative data also can be gathered from different platform such as documents, images, postcards, drawings, newspapers or magazines, Internet, blogs, and forum discussion to act as evidence for the contextualized interview data. These kinds of data can be considered visual data and they can be in visual and textual form [39,40]. These visual narrative data could be gathered from printed documents such as postcards, brochures and books, virtual output such as websites, online articles, online archives, and blogs, as well as from museums or galleries. The visual data can be in the form of postcard pictures, old photography, dioramas, mural painting, or sculpture.

References [41,42] also emphasized that narrative researchers must eschew the objectification of the people and embrace the structure of the knowledge to make highly contextualized interpretation. Reference [43] added that the question arises, as the way narrative researchers look at the story is with the objectification of the people, even though it must be studied in its socio-cultural context. Thus, interview data alone may not be able to become the evidence and fully support the results of a report. Narrative analysis can be the technique to generate stories for data collection and also the technique for data analysis. However, reference [32] mentioned that the data that are collected through narrative interviews could be analyzed in different ways after the data are captured and transcribed. Instead of narrative interview, narrative research from other sources, which is mostly from the visual data, is also adopted in this research. Furthermore, reference [44] proposed a novel variation on contextual inquiry by combining the use of news, academic, and data science blogs to visualize the exploratory analysis. There is also a mixed-method or multi-methods triangulation is proposed where qualitative (interviews) and quantitative (questionnaires) methods are combined [45]. For this research, the triangulation method is applied on both investigation and data analysis by substantiating the narrative data with visual data to enhance the trustworthiness of the results.

3. Interview Process

In this study, the interview approach was in the semi-structured form. The face-to-face interview was carried out to elicit stories from the informant effectively. The purpose of this interview is to explore the in-depth experience of the informant towards the cultural heritage about the garments, occupational activities, and the social status that had happened in the old Weld Quay in the 19th century. On top of that, the informant was elicited to share remarkable moments and interesting stories of the olden days. The interview schedule was firstly designed with key questions and was sent to the informant via email and through other appropriate platforms. The questions had been sent to the informants beforehand so that they could understand and validate the content of the interview. However, the experience and story that they had shared could be directly and indirectly related to the objective of the interview and later it is needed to be extracted and filtered.

The interview was held at a location that was convenient to the informants. The semi-structured interview had been conducted in approximately a natural exploratory conversation. Moreover, this interview could be considered fairly successful if the informant was able to elicit information through the naturally occurring question. During the interview, the conversation began with a phatic talk in order to soothe the atmosphere as well as to build rapport. Once a while, the interviewee was provoked with interview interventions such as “Can you tell me more about it?” or “What was the experience like for you?” [46,47,48]. However, the interviewer had to give good control of the digressed informants despite the interview progressing in a free and natural fashion. The informant to be interviewed was selected purposively based on his background and experience. For that, two informants were found and were invited to participate in the interviews. The interviews were conducted for two informants separately. In this study, they were named as Informant A and Informant B.

3.1. Background Study on Informant A

Informant A, who was born in 1952, is the direct descendant of a local who has been working as the laborer in the Penang old port. At his young age, Informant A helped out his grandfather and father in handling the task of negotiating and liaising with suppliers in foreign countries regarding the ingredients. Each time when the ordered goods arrived, he had to report to the officer before picking up the goods at the port so that the officer was well acknowledged about the activities and operations of the port and sampan. Other than that, a few local reporters and television program crews from China approached him for an interview regarding the olden days’ stories in Penang. Additionally, a few books were published and written depending on the data as well as the narrative stories that were told by him. He has been a member of the Chinese United Association for several decades since he was 18 years old. He has much knowledge and many life stories regarding the ethnicities in Penang, especially about the Chinese social life and associations’ operation of Chinese ethnic.

Chinese people in Penang prefer the social life of the multi feast, and Informant A is usually the leader of these occasions. In addition to not participating in politics, he presided over almost all the Penang Chinese major ceremonies. He mentioned that he was born to be an active supporter of all education, Chinese festivals, and community activities, just like his father and grandfather. For that, he became the leader of the Penang Chinese Community and he then gained a ‘Datuk ship’ from the country due to his contributions to society. From the background stated above, Informant A could be seen as one of the suitable candidates to be interviewed for this study.

3.2. Background Study on Informant B

Informant B was born in 1961 and graduated from the University of New South Wales in Australia majoring in Information Technology. His earlier hobbies were learning foreign cultures as well as languages, and he was able to travel extensively overseas due to his profession. In the early 1900s, he lived in Tokyo for four years and developed a great interest in tracing the history of Japanese people living in South East Asia, specifically in Malaya and Singapore, before the war. After relocating back to his hometown, Penang, he began participating in various non-government organizations (NGOs), advocating for the conservation of nature and regional cultural heritage in Penang.

He is a certified guide and educator in heritage, cross-cultural, and tourism subjects. He also raises awareness of the history of the minority immigrant society in Malaysia including the Arabs, Armenian, Burmese, Japanese, Jews, and Germans, etc. He is currently a council member in the NGO of Penang Heritage Trust, a non-governmental organization that is dedicated to heritage conservation. Additionally, he organizes talks regarding the local history and protests against the devastation of historical sites and buildings. For that, he was involved in the “Save Koay Jetty” campaign in 2005 and led a project in exhibiting the history of Clan Jetties in time for International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) inspection before the inscription of George Town as a World Heritage Site. His other activities include conserving the historical cemeteries and producing brochures and signboards on the German and Siamese heritage trails in Penang.

It is natural to have two Chinese informants, because Weld Quay was predominantly used by them for trading. Additionally, the choice of selecting these two informants was based on the fact that one of the informants is the expert in history of Weld Quay and the other one has own experiences in trading, being the third generation who was living with his father and grandfather. Furthermore, both of the informants are aged, well informed, socially recognized persons who have national awards, are physically fit, and can remember the past well, and people and students often interview them for information.

4. From Stories to Data Analysis

The data analysis begins with analyzing the recorded narrative interview data and life stories shared by two different informants. Firstly, the audiotaped recordings were transcribed manually into text within 24 h of the interview. The prompt transcription afforded a clear sense of the participant’s voice being alive in the transcripts [49,50]. When the transcribed work was progressing, the key points began to be identified. Throughout the transcribing work, it was found that many of the stories shared by the informants were irrelevant to the study’s topic, since it is a semi-structured interview. For that, only the useful and appropriate stories and interview data were extracted and transcribed. The transcription was then analyzed and interpreted into a story form based on Informant A’s and Informant B’s life stories. Table 1 shows the data coding used in the transcriptions.

Table 1.

Data Coding Used in the Transcription.

The story lines that are relevant to the inhabitants’ garments based on the raw data:

4.1. Narrative Stories Based on Informant A and His Grandfather

The Chinese laborers also wore pants that eased their work of carrying goods. These pants were also called ‘ngau tau fu’. They resembled bucket pants, and only long pants were available. They were mainly wooden brown and black. Informant A mentioned that most of the laborers in the past wore that and he also recalled that his father had worn that too.

“I have seen those pants before as my father wore them too. The pants were called ‘ngau tau fu’.”(Inf A, 20-L119)

The pants’ pattern was different from others, as it did not have a waistband but was tied with a long piece of cloth in the waistband area, and the cloth was named ‘shui mang’. It resembled the pants that had been worn by Bruce Lee for his movie. The lower part of the pants was very broad so that the laborers could move easily while carrying the goods. Other than that, the laborers would tighten the knot of ‘shui mang’ to provide much strength to the upper part of the body while the laborers were carrying the goods.

“It is like towel. Shui mang is a kind of cloth.”(Inf A, 21a-L111)

“They were pants, but the pattern of these pants was different from others. The waistband area was tied with long piece of cloth. The lower part of the pants was very broad.”(Inf A, 21b-L112)

“The main purpose is to ease the laborers when they were working, so that they could easily move while carrying the goods. It’s just like Bruce Lee’s costume in the movie.”(Inf A, 21c-L113)

“Yes! The upper part of the pants consists of shui mang. Whenever the laborers required much strength for carrying goods, they would tighten the knot of the shui mang. It is a long piece of cloth.”(Inf A, 21d-L115)

The top part of the pants was then folded down to cover the ‘shui mang’ and the folded area could be used to keep money, as the laborers could not bring a wallet with them.

“…because there was no rubber at the waist. The top part of the pants will then be folded down and cover the shui mang.”(Inf A, 22a-L116)

“…so then laborers can keep money in the folded area, as they couldn’t bring a wallet with them.”(Inf A, 22b-L117)

Informant A added that the laborers usually wore black and kept their body naked. Some wore a mandarin jacket that consisted of four pockets and a fabric button. They also wore it with a matching hat.

“…Laborers wore black in color. They usually kept their upper body naked.”(Inf A, 23a-L92)

“You mean the mandarin jacket with fabric buttons?”(Inf A, 23b-L102)

“The mandarin jacket consists of four pockets. They wore it with a matching hat.”(Inf A, 23c-L95)

People in the past just put on the mandarin jacket without buttoning up. Moreover, the fabric of the jacket was as thick as the canvas, so that they would not wear two pieces of clothing due to the hot weather.

“They didn’t button up the jacket. The jacket was with buttons but it was not buttoned up. The people in the past wouldn’t wear two pieces of clothing due to the hot weather. Furthermore, the fabric of the jacket was very thick. It was as thick as canvas.”(Inf A, 24-L104)

The mandarin jackets were mostly in blue, resembling the blue that used in the logo of Barisan Nasional (i.e., political party). Informant A emphasized that this blue tone was resistant to dirt. Additionally, people back then did not use strong detergent but only used soap to wash clothes.

“The mandarin jacket was in blue. The blue looked ugly. They normally dyed the fabric with blue color, just like the blue that is used in the logo of Barisan Nasional.”(Inf A, 25a-L93)

“This tone of blue was used in the past, as it was resistant to dirt. Dirt can be easily visible on lighter colored fabric. Moreover, they didn’t have strong detergent during that time. They only used soap to wash clothes.”(Inf A, 25b-L108)

The fabric in those days was mainly made by the factory, and there were only limited choices of colors such as brown, beige, and black. The main color of the pants was wooden brown and black, whereas the shirt was blue white and beige in color. However, the fabric was preferably dyed with dark color, because it could absorb heat easily.

“It was made in a factory, but there were limited choices of colors, such as brown, beige, and black…”(Inf A, 26a-L109)

“No, only long pants were available. They were mainly wooden brown and black in color. However, the main color for shirt was blue, white, and beige…”(Inf A, 26b-L121)

“…The fabric was dyed with dark color, so it could absorb heat easily…”(Inf A, 26c-L105)

When mentioning about the fabrics used to make clothes in the past, Informant A told that the material was cotton because polyester could not be found during that time due to lack of advanced technology in chemistry. Instead of cotton, linen was also widely used to make clothes. However, its quality was much lower, as it had a rougher surface compared to cotton and silk. Informant A also declared that only fabric that made from cotton, linen and silk were mostly used in the past.

“Cotton must be the only material used to make clothes because polyester was not available during that time.”(Inf A, 27a-L84)

“…Only cotton was available in the past. Another material widely used by people was Ma (linen).”(Inf A, 27b-L85)

“Ma (linen) has a rougher surface than cotton. Cotton and silk can be said as the best materials back then. Only these three materials were used in the past.”(Inf A, 27c-L86)

When it comes to the garments of the British, Informant A mentioned that they wore the shirt with short pants, and both shirts and pants were white. During that period, the particular short pants were called ‘ma yin tong’ in Cantonese. Unlike ‘ngau tau fu’, it consisted of a waistband, and the lower part of the pants was very broad; therefore, many pleats were found in the waist area. Similarly, the policemen and the government officers were also dressed in white.

“…Those who dressed in white were policemen and government officers. However, the British usually wore shirts and short pants, which were both white in color. The short pants were so referred to as ‘ma yin tong’ in Cantonese.”(Inf A, 28a-L121)

“…There were many pleats found at the waist area because the lower part of the pants was very broad…”(Inf A, 28b-L122)

For Malay ethnic, Informant A said that they were rarely showed up in Weld Quay. Maybe one or two Malays would pass by there. There was the Penang Acheh Association nearby the Weld Quay. Thus, most of the Malay in surrounding Weld Quay was from Acheh. Similar to the native Malays, they wore sarung and songkok.

“I didn’t see any Malays in Weld Quay. It was rare. Maybe one or two Malays who were wearing songkok will show up there. There were many Chinese.”(Inf A, 29a-L126)

“There was also the Penang Acheh Association. There were quite a number of them around Weld Quay if you are talking about Malay ethnics from Acheh.”(Inf A, 29b-L127)

“Same as the native Malays, they normally wore sarung and songkok.”(Inf A, 29c-L128)

Informant A shared the above stories during the semi-structured narrative interview. The stories in terms of the social status, the way different ethnic groups dressed in, and also the occupational activities at Weld Quay during the 19th century were based on the stories told by his elderly as well as his own experience. From the analyzed data, Informant A shared the stories that were mostly about the Chinese ethnic group. In those days, he had less opportunity to mingle with other ethnic groups due to the association that he was involved in. Additionally, the event or ceremony that he had attended and his business target audiences were mainly Chinese. To collect more relevant data regarding the garments and also the activities conducted by other ethnic groups, another informant had been invited for the narrative interview to elicit more stories and data about Weld Quay.

4.2. Narrative Stories Based on Informant B

Informant B added that other than Hokkiens, there were other clans of Chinese in Penang that were Kwangtung (Cantonese), Teowchew, and Hakka. Informant B indicated that the majority of Chinese in Penang were Hokkien with a percentage of 40–50%, Kwangtung occupied 20%, Teowchew 15%, and Hakka consisted of 8%. Informant B also mentioned that most of the Kwangtung people previously were tin miners but not working as laborers at the trading port.

“Hokkien…Hokkien…still Hokkien yeah! Hokkien people…Hokkien people in those days is about 40–50%, and Kwangtung, Cantonese is 20%, Teowchew is 15%, Hakka 8%.”(Inf B, 7a-L94)

“Kwangtung they don’t really find them… because you know Cantonese they are tin miners. Penang not many Cantonese.”(Inf B, 7b-L92)

The clan jetties were situated at the southern end of Weld Quay. Before the clan jetties came about, they were staying in the area of Stewart Lane. Most of the places in this area were coolie houses. Fifty to sixty people could occupy one coolie house back then. Until the clan jetties had been built, the Chinese communities pulled their clan people from China to come over to Penang.

“Before these clan jetties came about, they were staying in the like Stewart Lane… all these places… the coolie house. One house fifty to sixty people all back then.”(Inf B, 8-L12)

Informant B mentioned that clan jetties back then were built for loading and unloading goods but not for transporting heavy goods, because the construction of the jetties was not strong enough as the Chinese did not have enough money for that. They were all poor Chinese. The heavy goods would normally go through the piers. Only some jetties were for charcoal and firewood trading, such as Yeoh Jetty.

“Yes! Clan jetty is like a great doubt that they can carry heavy goods. Some clan jetties are only for charcoal. Like the last few one… the Yeoh Jetty is actually for charcoal.”(Inf B, 9a-L69)

“…Yeah… and it is very shaky and then they construct themselves and then they were poor Chinese. Where they have money to build a strong…err…this…err…pier. No, that’s not pier. So whether they really carry heavy goods and go through the clan jetty and you find opposite the clan jetty, they are not really warehouses. So this is more for residential. So the Chinese…from the clan jetty also go to the pier to get the things down…up and down lah.”(Inf B, 9b-L71)

On the previous day, not all the Chinese communities from clan jetties were working in the trading port of Weld Quay. Only residents from Chew Jetty, Lim Jetty, Lee Jetty, and Ong Jetty would work as coolies or stevedores at the port. Similarly, Indian ethnic groups also worked as coolies at the port, loading and unloading the goods at the piers to the godowns.

“Yeah, the clan jetties are good example. Not all of them nah… Err… I think that Lee Jetty, Chew Jetty, Lim Jetty and most of the people work as the porters lah. Stevedores! We have a good call… stevedores! or you can call them as coolies.”(Inf B, 10a-L11)

“…the coolies are either Chinese or Indian carried all the goods to the… the gudangs.”(Inf B, 10b-L9)

However, Malays rarely showed up in Weld Quay. According to the Informant B, the native Malays mostly stayed in the Seberang Perai. In those days, the major occupation of Malay ethnic in Penang was farmers or fisherman in Tanjong Tokong. Informant B also added that there were Malay mostly from Acheh would appear in Weld Quay, as the Lebuh Acheh, which is a mosque, was situated near to the Weld Quay.

“As in Kedah Malays stayed in the Seberang Perai.”(Inf B, 11a-L30)

“So… very few really crossed to the island side lah. So if we’re talking about Malay, there…many of them would be the Acheh Malay descendants.”(Inf B, 11b-L31)

“Okay…if you want to define Malay…err…In town, the urban Malay…there’s one from Acheh.”(Inf B, 11c-L28)

“Muslims err… they were…there is no record of showing them were working as the laborers because they were farmers. Paddy field…farmers…and fisherman in Tanjong Tokong.”(Inf B, 11d-L16)

When it comes to Malay sub-ethnic groups, many of them could be found in Penang. Since there were varieties of Malay sub-ethnic groups, they would be grouped as Malay ethnic. There were Jawi Peranakan, Tamil Muslim, some were mixed with Arabic, Hadrami Muslim from Yemen, Malay from Acheh, and many more. The arrival of Malay sub-ethnic groupsback then was to preach and set up the mosque such as Lebuh Acheh. Eventually, some of the Malays in Jawi began setting up the printing shop in town.

“We have to be more specific because…and then we also have the Jawi Peranakan. They are some mixed. Malay mixed with the Indian–Muslim, some also mixed with the Arabic. We have the mahadrami…Hadrami Muslim…is from Yemen. Actually they went through Acheh, and from Acheh, they came to Penang. Hadrami ya…Some are Arabs. So Muslim…We have to group them as Muslims. It’s so mixed already.”(Inf B, 12a-L32)

“…but those days what we meant the Muslim communities is err…ar Lebuh Acheh, setting up their printing shops. Some of the Malay in Jawi… the earliest comes in this countries to set up their printing bookshop.”(Inf B, 12b-L22)

“Arabic guys also… Hadrami ya…appear…yeah…The record shows 500 of them…by Acheh come to Penang and they want to set up like Acheh Mosque…all these things and a lot of them actually are Iman…and well-known.”(Inf B, 12c-L33)

Analysis of both narrative stories found that the contents shared by Informant A are working complementarily with the contents shared by Informant B. During the process of analyzing the narrative data, several common contents have been identified. On the other hand, different opinions and stories for certain aspect were also figured out from both of the narrative interview data. In order to identify the discussed and contradict contents regarding the same topics, a checklist was constructed as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Topics that have been narrated by Informant A and Informant B during the interview.

Table 2 shows two themes that are garments worn by different ethnic groups in the past life of the trading port of Weld Quay, and occupational activities happened in Weld Quay trading port with many aspects of data that are required in this study. However, both of the narrative interviews did not cover all aspects of the garments of the four identified main ethnic groups during that period. Thus, a checklist was prepared, and the icon (✓) was used to mark up the aspects that have been covered in their narrative stories, whereas the icon of (✗) was given to the aspects that were not discussed during the interview. The results obtained from Table 2 show the different types of iconic combination. Additionally, neither Informant A nor Informant B narrated the stories regarding the aspect of Indian garment due to their lack of knowledge regarding that topic. For the rest of the topics covered, other data from different sources were collected as the evidence and as cross-references for the narrative interview data.

Since in this research, only two informants were found for the interviews and both did not specify the Indian clothing at first, later, the two informants were asked again to help in our visual analysis specifically for substituting the missing information by identifying the Indian garments through some old photos. This is because the interview was conducted in a very open manner where the questions asked were not meant to rigidly classify the oral history based on their ethnicity. The informants are free to narrate and share their experiences based on their comfortable flow. Thus, the Indian clothing is mainly relying on the visual data observation and analysis. The visual analysis is to support the missing narrative analysis.

Apart from having two informants for interviews, we have also asked the Interpretative Centre of George Town World Heritage Incorporated about the oral history documentation. The oral documentation started in 2013 and aimed to improve in the historical resources and references. Under the oral collection of clothing, there are eight contributors from the local community, namely Mr. Siew Ah Tak, Mr. Ashraff bin Abdul Karim, Mr. Lo Fook Kheong, Mr Lee Po Seng, Mr. Vengadasalam a/l Rengsamy Achariar, Mr. Wong Heng Mun, Mr Abdul Aziz bin Mohd Hussain, and Mr. Rajendran Kanapathy, which we later named Informants C to J. Although Informants C to J mainly talked about their memories focusing on the life in Chulia Street during the post-war period and after the invasion of Japanese in year 1945–1970, whilst the scope of this paper is the early 19th century when the British ruled Malaysia and left their influence during the wide-ranging ethnicity-specific traditional trades including costumes and the lifestyle of Penang inhabitants that still can be seen today, these informants did mention their parents’ stories too. The majority of the informants in the oral documentations are tailors and involved in the textile industry, except Informant C, who was in the watch industry, and Informant E and Informant G, who were in gold and jewelry industries. Some common understandings about the costumes in the past were gathered based on their oral histories, where all tailors mentioned people who repaired and altered the clothes in the past and that the quality of the cloths back then was thicker and more durable. Informant F is a coat maker and has also mentioned that the inhabitants usually tailor-made suit coats and the tailoring fee for a set of clothes and a suit was very expensive and not many would have afforded them. Talking about prices of costumes, Informant D and Informant H mentioned that the quality of the sarong was good that it could be pawned, and certain stitching shops would pawn their customers’ cloth only to get it back when they have saved up enough money, sewed it, and then returned it back to the customers. Informant D and Informant H were mainly selling Muslim-related items such as sarong and songkok, because there were many inhabitants staying in the Acheen Street that was near to Weld Quay, while Informant J, who was mainly selling Indian-related items, mentioned that there were only certain people who bought silk and certain special occasions/days on which people would come to buy silk, because silk was very expensive. Regarding the colors, all tailors mentioned that there were usually white, blue, grey, and black cloths, and Informant H mentioned that he kept up to maximum of ten colors of cloths at that time. All tailors also mentioned that there were not many patterns and choices, and Informant J mentioned specifically that the patterns of clothes did not change much before 1975. Back then, the main luxury accessories for the upper class were either watches or gold, diamond, and gemstone jewelry. Informant C mentioned that there were demands for Longines and Rolex in the 1970s until Seiko introduced the digital watches in 1957. Informant E and Informant G were both goldsmiths; Informant E usually served the Chinese customers, while Informant G usually served the Indian customers. Informant E mentioned that Mainland Chinese liked to buy gold with a fish shape, and they only returned for purchasing after a long time, because they had to earn and save the money first. Informant G concluded that in 1962, life had become difficult for goldsmiths, because of the lack of demand due to the post-Second World War period.

5. Collaborative Analysis Process

Thorough narrative analysis, interpretation of the collected data was progressed to analyze the data obtained from the narrative interview. The narrative analysis was not only dependent on the interview data itself. The analyzing of the narrative data had to ascertain with other visual data to eschew the objectification of the informant as well as embrace accurate evidence or references to make a highly contextualized interpretation. Therefore, visual analysis together with the element of semiotic analysis was also employed for sorting, categorizing, and identifying the denotative as well as the connotative elements of a large amount of visual data. In short, narrative analysis was complimentary with visual analysis and semiotic analysis for investigating the history as well as the elements of garments and occupational activities that had happened in the past as well as influenced their social status. Scrutinizing the interview data by corroborating with other visual data based on removing the contradict contents and extending the aspects from the themes, which are the garments, social status, and occupational activities that had happened during the 19th century in Weld Quay. Table 3 shows the statistics of the denotative elements identified from each data source, whether it is a printed document, virtual output, or resources obtained from the visit to Penang Gallery and Museum.

Table 3.

Statistics of the denotative elements identified from each data source.

More than 200 visual data were gathered from different sources such as printed documents, postcards, and books and virtual output such as websites, archives, articles, and blogs as well as galleries or museums in Penang. Out of 200 visual data, 111 visual data were highly related to Weld Quay in the 19th century. Only 43 visual data were sorted, and these material cultural data on garments were found appropriate for cross-checking with the narrative interview. According to the result shown in Table 3, about half of the visual data were collected from the old postcards, while the second largest group of the visual data were gathered from the museum and gallery. Visual data collected from the website and books only occupied 11.62% and 9.30%, respectively. The remaining visual data were collected from the rest of the publications such as brochures, archives, articles, and blogs. Each piece of visual data was then categorized by identifying its denotative elements. The sorted data were also identified, and the elements were interpreted according to the identified elements.

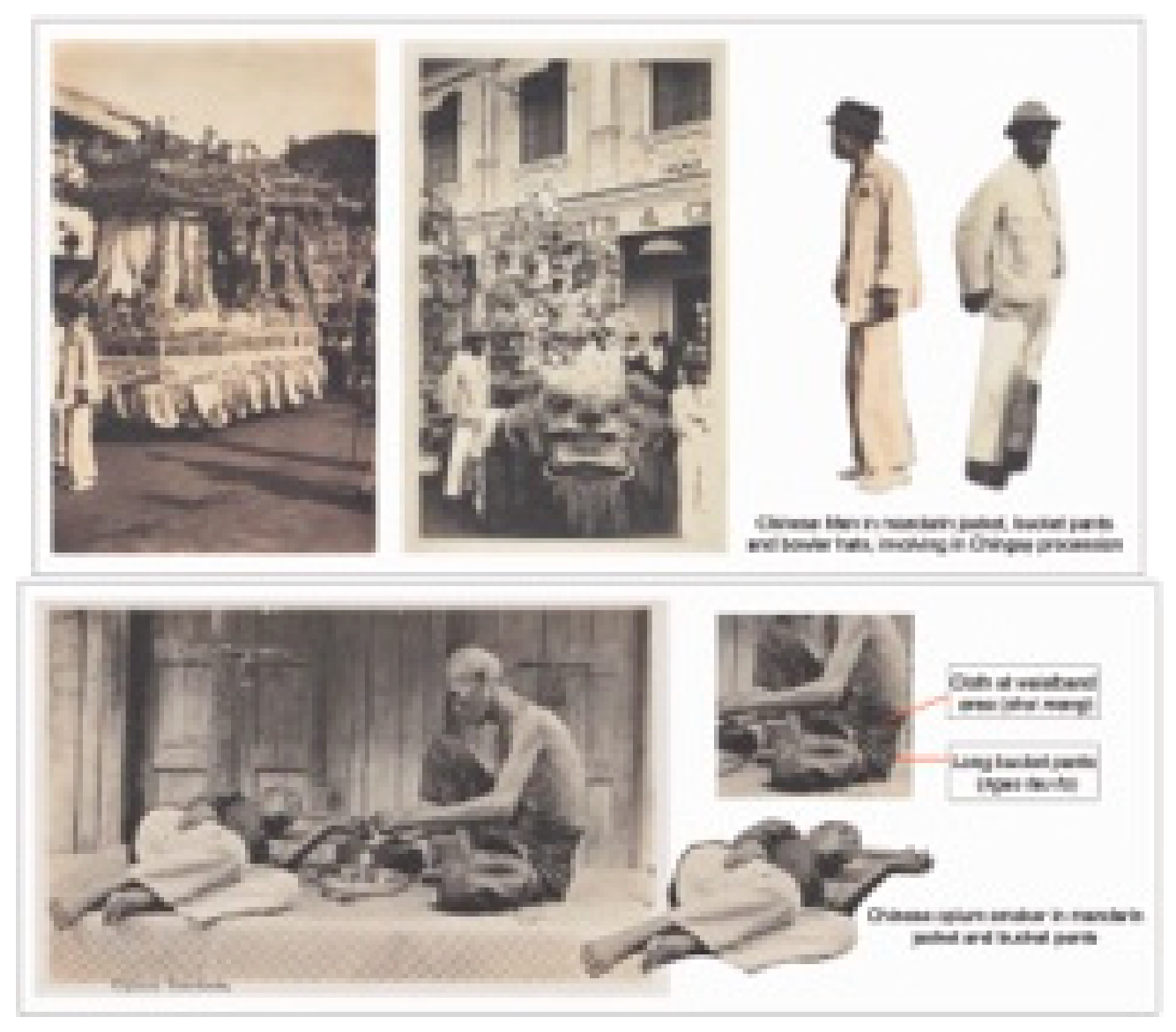

5.1. Garments of Chinese Ethnic at Weld Quay

The visual data of the garments of Chinese laborers merely existed. The resolution of the figures was either low, snapped from a far distance, or only showed the back view of people. For that, Figure 2 shows the Chinese ethnic group based on the garments where Figure 2a–c required intellectual guessing skill to distinguish their social status. People who were working as laborers in the foreground, as shown in Figure 2a, a man found in Victoria Pier, in Figure 2b, as well as a man was walking on the plank pathway of the Church Street Pier, in Figure 2c, were believed to be of Chinese ethnicity, and this could be recognized by analyzing their garments. However, according to the garments, the man found in Figure 2c was believed not to be working as a laborer but either as a merchant or having a higher status. This is because men in white in those days ere wealthier and prominent Chinese.

Figure 2.

Garments of Chinese ethnic groups. (a) Chinese laborers in bowler hat, mandarin jacket with cropped bucket pants [52]; (b) Chinese ethnic man in bowler hat and mandarin jacket found in Victoria Pier [53]; (c) Man with bowler hat, white shirt, and white long pants [52]; (d) mural painting: Chinese laborers in long bucket pants as well as mandarin jacket, which was designed with four pockets and cloth buttons, standing at trading port; (e) Diorama: Chinese laborers in mandarin jackets and bucket pants, matching with straw hats; (f) Chinese ethnic men in mandarin jacket and long bucket pants conducting daily activities, smoking opium [53]; (g) Chinese hawker in daily garment of mandarin jacket and bucket pants [54]; (h) Chinese ethnic men in mandarin jacket and bucket pants hiking in Penang Hill [53]; (i,j) Chinese ethnic men wearing bucket pants as well as mandarin jacket designed with pockets and cloth buttons during the Chingay Event [53]; (k) many wealthier and prominent Chinese in White Jackets and Hats walking before the chariot during the Chingay Procession [52]; (l) the Chingay flags all dressed alike, in white cotton trousers and shirt [52]; (m) the earlier Chinese immigrants with Manchu-style ‘tails’, leaning against the railings shirt [52]; (n) Chinese laborers with the head front shaved photographed at the memorial of Benet Vermont C.M.G.M.L.C, Esplanade, which was situated at the northern end of Weld Quay shirt [52]; (o) Ancient Egypt turned the flax plant into linen fabric.

Some interesting visual data were collected from the Penang museum and diorama gallery. The mural painting and the diorama scene are depicting the lifestyle and traditional trade in Penang. The diorama sculptor has sieved through the old postcards and photography to create a real-time diorama [51] In the sculpting, the Chinese laborers were dressed in the mandarin jacket and long bucket pants as well as matching hats. Instead of working, the same garments were also worn in their daily lives, as shown in Figure 2d–h, as well as during special events, for instance, the Chingay procession, as shown in Figure 2i.

Referring to the figures above, four pockets and cloth buttons designed at the front could be seen as another signature element in the mandarin jacket, whereas wearing bowler or straw hats to match their garment was also one of the typical elements and stereotypes for the Chinese ethnicity in the past, both in the lower class of Chinese ethnic people such as artisan, workers, and laborers or wealthier and prominent Chinese. Yet, Chinese in the higher class were preferably wearing the mandarin jacket and pants in white. Instead of the traditional garments such as a mandarin jacket and bucket pants, the wealthier Chinese would also dress in a suit, which was white as well. In those days, wearing a white shirt and pants was able to represent one’s status, as shown in Figure 2k.

Instead of the design of the garments, another important element has been delivered from Figure 2l. A good description was given regarding the garments and material used to make the garments worn by the young men in the photograph. The Chingay flags as shown in the figure were wearing white trousers that were made with the material of cotton (or with blue Chinese silk for sometimes). Referring to the statement given, cotton and silk were believed to have had use to make clothes during that period. On top of that, there was also a significant distinction between the earlier Chinese immigrants and the newcomers, which was known as sin-kheh. This situation could be distinguished by their hairstyles. For the earlier Chinese immigrants it was compulsory to keep long braided hair along with the shaved front portion of the head subject to the “Queue Order” in China (See Figure 2m,n). However, the sin-kheh were free to manage their hairstyle.

In summary, wearing mandarin jackets and bucket pants with matching hats can be considered the daily garments and typical stereotype for almost every Chinese ethnic person during the 19th century in Penang, similarly to the Chinese laborers at the trading port in Weld Quay, thus the statement of Informant A regarding the daily apparel of Chinese ethnic groups, which was the bucket pants ‘ngau tau fu’ and mandarin jacket that designed with four pockets as well as the cloth button at the front was valid. Moreover, the statement regarding cotton and silk fabric existed to create garments in the past that has been verified with the interpreted and analyzed visual data. However, the linen fabric that has been mentioned by Informant A was believed to exist and used to create garments too. According to [55], linen was originally from the Middle Eastern countries, for instance, Egypt, and the latest discoveries in the Republic of Georgia showed that products made from flax plant already existed and were used by humans from about 30,000 B.C., as shown in Figure 2o. Reference [56] indicated that the Egyptians after that indulged in trade, and soon it filtered into England. This fabric entered India during the British Rule, and it became extremely popular in the fashion industry to make varieties of garments such as pants, shirts, and Indian ethnic attire. From this case, the researchers believe that linen fabric appeared and was used to make garments in Penang during the 19th century. Penang was a colony of the British, and a large number of Indian traders as well as immigrants arrived in Penang.

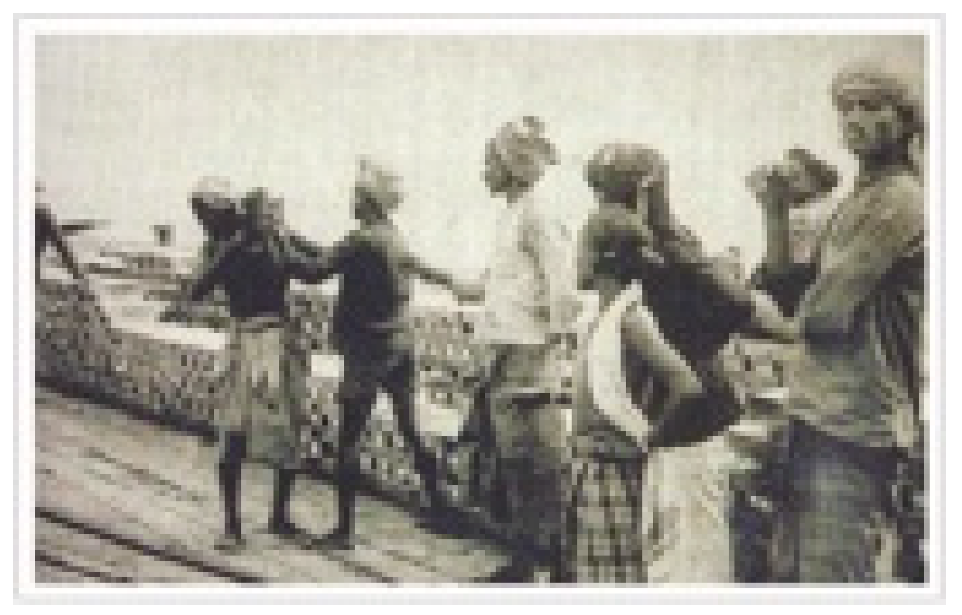

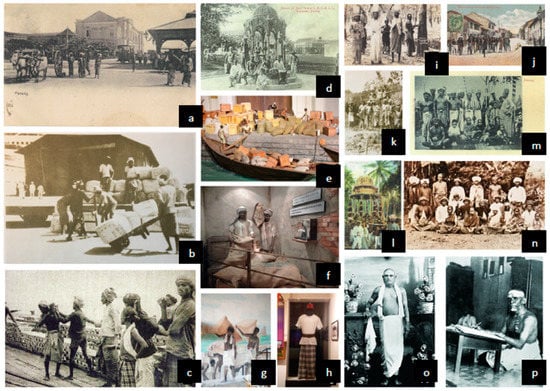

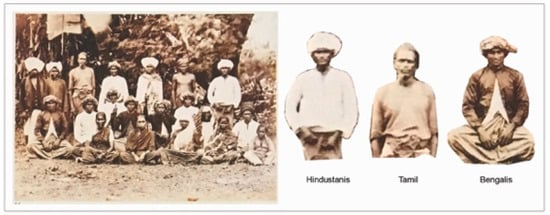

5.2. Garments of Indian Communities at Weld Quay

When it comes to the garments of Indian ethnic groups, the most common garments and typical stereotype found in laborers (Tamil-Muslim) at the Weld Quay trading port were wearing headcloth, shirtless, and wearing white cloth, kain pelikat, or checkered sarong, as shown in Figure 3a. Meanwhile, some of them would wear the shirt (gupha) as well (See Figure 3b–d). Whenever the topic regarding Penang history was mentioned, the history of Weld Quay and the trading port were indispensable, because the Weld Quay had been the core place where the immigrants of different ethnic groups were gathered as well as being the main place of income generation. Thus, museum and galleries have always been a platform for gathering related visual data instead of collecting from postcard pictures or books. From there, there are a few visual data that show the garments of Indian ethnic groups obtained from Penang museum and some art galleries in the form of the diorama, statue, mural painting, and showpiece, as shown in Figure 3e–h.

Figure 3.

Garments of Indian ethnic men. (a) Shirtless Indian laborers in head cloth and kain pelikat, standing in front of the Victoria Pier [53]; (b) Indian laborers in head cloth, white shirt, and sarong, unloading goods at Swettenham Pier [57]; (c) A shirtless Indian Laborer with head cloth and checkered sarong, carrying tin ingots [58]; (d) Indian laborers with their daily garments photographed at the memorial of Benet Vermont C.M.G.M.L.C, Esplanade [53]; (e) Indian laborers in white sarong and head cloth resting after work; (f) Indian laborers in white dirty shirt and head cloths carrying heavy sacks on their backs; (g) mural paintings: Indian Laborers with only white sarong, working at the port; (h) shirt and checkered sarong exhibited in Penang State Museum and Art Gallery; (i) Indian laborer in head cloth, shirt (gupha) and checkered sarong (kain pelikat), working at rubber state in Penang [53]; (j) Indian laborers in head cloth with checkered sarong, keeping upper body naked working as road repairer in Penang [53]; (k) a photo of Indian indentured laborers with daily working garments found in Rockhill [57]; (l) Indian–Bengalis (Sikh) policeman in turban and uniform, standing guard for the procession activity [52]; (m) South Indian–Tamil photographed in a different hierarchy [52]; (n) Indian sub-ethnicities like Hindustanis, Tamil, and Bengalis found in Penang [59]; (o) the portrait of Chettiar in the early 20th century from the National Archives of Singapore (2017); (p) a shirtless Chettiar with sacred ash smeared across his forehead pictured at his work desk, from the National Archives of Singapore (2017).

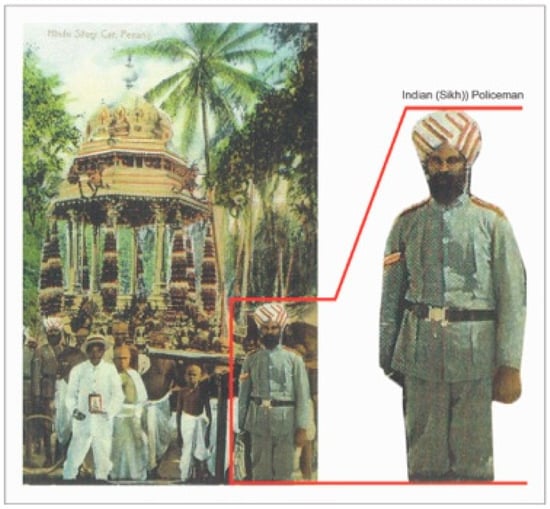

Referring to the evidence and figures shown in Figure 3, the researchers believe that the headcloth, wearing a sarong (either with a checkered or plain sarong) as well as keeping their body naked or putting on a shirt can be confirmed as their daily working garment and the typically stereotyped garments of Indian laborers at the port in 19th century. Nevertheless, these particular garments and stereotypes were not only found in the laborers who were working at the port but also in the laborers of other industries such as rubber estates (See Figure 3i), road repair (See Figure 3j) and rock hills (See Figure 3k). Although the job scopes of the indentured laborers were different, they had similar stereotypes. This is because they originated from the same area, southern India, so that they were carrying similar stereotypes in terms of habits, customs, garments, and occupations. The majority of them were brought in by the British East India Company and later sent to work as laborers, policemen, and sepoys. However, policemen and sepoys in those days did not wear the same garments resembling laborers, but they dressed in uniform, as shown in Figure 3l and Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Indian–Bengali (Sikh) policeman in turban and uniform, standing guard for the procession activity.

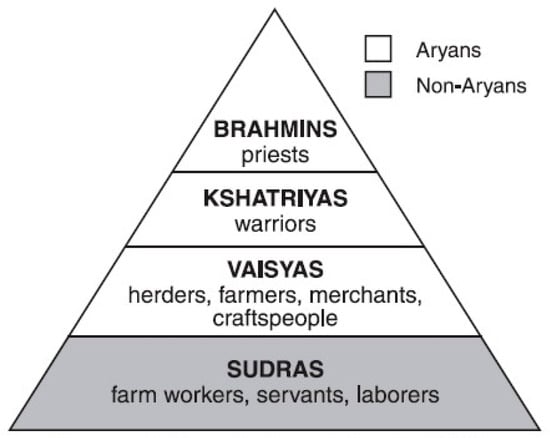

During the 19th century, Weld Quay had become a place where people often appeared. Apart from the Tamil laborers, other Indian ethnic groups with higher status such as the merchants, traders, chettiars, and high-class Hindus would also appear in Weld Quay, because Weld Quay was the major station for embarking passengers who came from a foreign country in those days. Therefore, the garments of other Indian sub-ethnic groups were necessary to study and analyze in order to verify the statement of the wearing styles that varied due to their occupation and status. Ancient Indian communities strictly followed the social hierarchy, and they were distinguished based on the vocation and profession [60], as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Social hierarchy of Ancient India [61].

Thus, this matter has a direct impact on their stereotypes in terms of garments, custom, as well as lifestyles. Figure 3m shows a diverse group of South Indian Tamils. Starting from the far right, there is an Indian Muslim man in a fez (resembling songkok), shirt (gupha), and checkered sarong (pelikat) who was a labor contractor (tandal) and came from Tanjore, whereas the group of Indian Muslim young men on the left were believed to be his port workers (indentured laborers). The group of people standing in the middle were high-class Hindus, wearing white cloth slung around the neck, resembling a vest. The three women and a baby girl sitting on the floor were Hindu women, while another two boys with songkok were believed to be local-born Jawi Peranakan of Tamil descent. Apart from Indian–Tamils and Indian Muslims recognized as Indian ethnic groups, Hindustanis and Bengalis also could be found in Penang, and they belonged to Indian communities in Penang as well. Referring to Figure 3n and Figure 6, Hindustanis and Bengalis can be clearly distinguished depending on their daily garments. Hindustanis put on the long length of cotton or silk to wind around their head, which was known as a turban. Additionally, Bengalis (Sikh) were dressed in red and white striped turbans, resembling the turban worn by the policeman in Figure 4.

Figure 6.

Indian sub-ethnic groups such as Hindustanis, Tamils, and Bengalis who can be distinguished according to their garments were found in Penang [59].

Among the several groups of Indian sub-ethnic groups, Chettiar communities were considered as one of the groups that comprised significant characteristics in terms of garments. Chettiars in the past life were usually bareheaded, shirtless, and wore a white dhoti with vibuthi sacred ashes smeared across their forehead, chest, and hands, sitting and working on the floor by the low desk, bent over, and writing on open ledges (See Figure 3o,p).

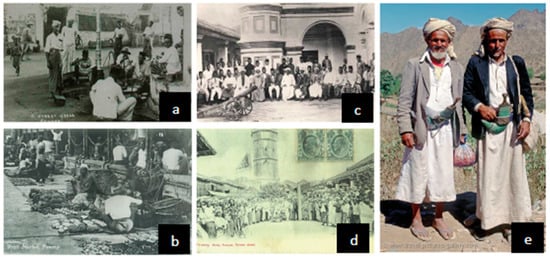

5.3. Garments of Malay Communities at Weld Quay

Indian Muslims are the largest community with dual identities in Penang, who were mostly found in Penang, and could be classified either as Malay or Indian communities. However, those who were not indentured laborers at the trading port such as ‘Mamak’ were categorized as Malay communities in this study. ‘Mamak’ was the term applied to the Indian Muslim who worked as food seller, and many of them were commonly found in Weld Quay, selling Nasi Kandar, Pasembur, and Kelinga Mee in those days. Both indentured laborers and ‘Mamak’ nonetheless were Indian–Muslim; however, both of them owned a distinct stereotype. The major distinction could be obviously identified from their garments’ element, songkok. Figure 7 shows the garments of the Malay ethnic group.

Figure 7.

Garments of Malay ethnic group. (a) Mamak in songkok, baju melayu, and kain Pelikat selling Nasi Kandar [62]; (b) An Indian–Muslim vendor in local Peranakan fashion, selling fruit at market [52]; (c) Acehnese and Arabian in different garments found in Malay Mosque [62]; (d) Indian Muslim and Hadrami with distinct garments found in the photography of the farewell event [52]; (e) the traditional garments of current Hadrami Yemen [63].

Reference [64] reported that the earlier generation of Malays and Indian Muslim would wear songkok every single day. In contrast, the researchers discovered that not all the Indian-Muslims would wear songkok, especially the laborers who were working at the trading port, but for ‘Mamak’, hawkers or vendors would mostly wear songkok; nonetheless, they were both Indian–Muslim. As for the other elements of the working garment, they were dressed in local Peranakan fashion, such as baju melayu with pelikat sarong, matching with songkok. They wore suitable garments based on their occupations, and this situation can be seen in Figure 7a,b.

In older Penang, each community would allocate themselves to a specific part of the town and had its headman Figure 7c. As for the Muslim community from Archipelago, Tengku Syed Hussain was certainly the leader, whereas his contemporary, Cauder Mohudeen, was the Kapitan Kling, the leader of the Muslim community that came from southern India, settling down in around Chulia Street. In 1808, Tengku Syed Hussain, a seasoned trader with a vast trading network, had built a Malay Mosque at Acheen Street, which was within walking distance from Weld Quay, and most of the Acehnese were occupying that area. Reference [65] mentioned that Syed Hussain’s trading network was so wide and immense that it influenced the archipelago, especially Arab and Acehnese, to move to Penang. Moreover, [66] added that the Arab migration was mostly Hadrami from Hadramaut, Yemen, and the only minority was from Iraq, Oman, Syria, Lubnan, Palestine, and Jordan. Therefore, the second largest group of Muslim communities that appeared in Weld Quay were believed to be Acehnese and Hadrami. However, the population of Arab communities is lesser compared to Acehnese, as Arab migration was never on a large scale [65].

Acehnese did not have much distinction with the local Muslim communities, as they had assimilated with the local Malay communities’ culture in term of dressing and custom and treated the Malay language as lingua franca [66]. Acehnese in the earlier days put on songkok and dressed in kain pelikat with baju melayu, whereas those found in those of the Arab community and these scenes were shown in Figure 6d. The followers in songkok, kain pelikat, and baju Melayu were Indian Muslim, whereas those wearing a headcloth and suit-resembling jacket matching with shirt and pants were the Hadrami from Hadramaut, Yemen. As for the garments of Hadrami, they were evident by comparing Figure 6c with Figure 6e. The traditional garment in the portrait of current Hadrami Yemen could be seen resembling the Hadrami garment in the old picture. Therefore, the researcher believed that there were a few Hadrami in Figure 6c apart from Indian Muslims.

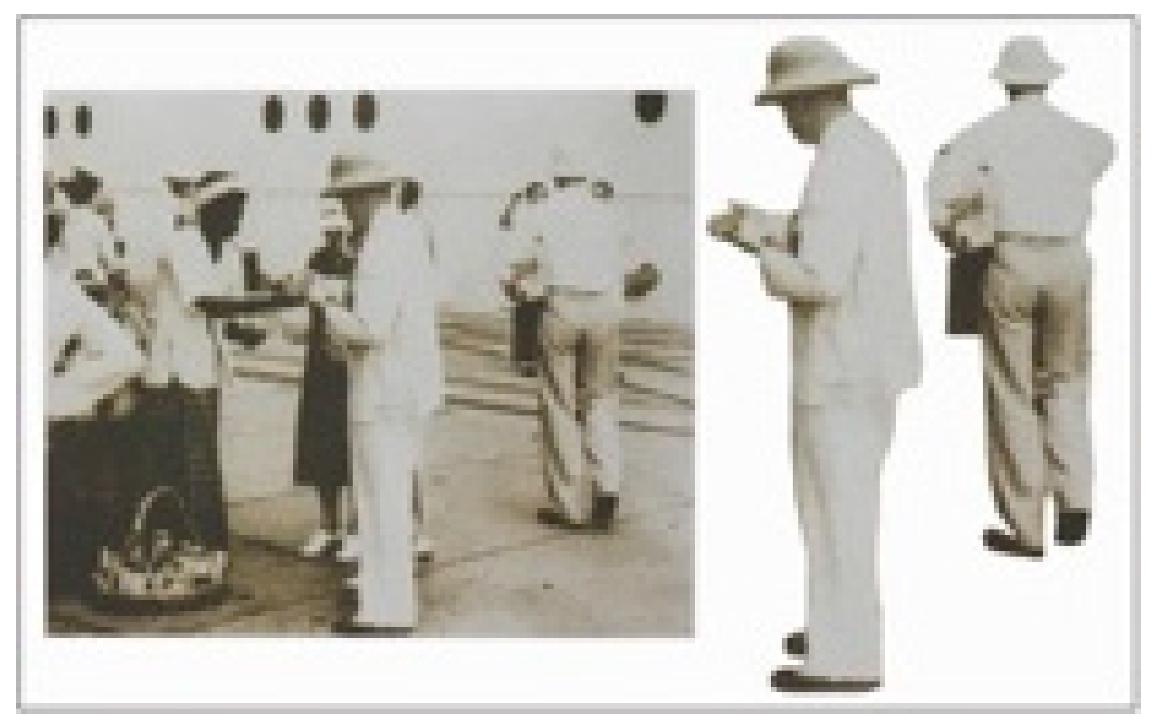

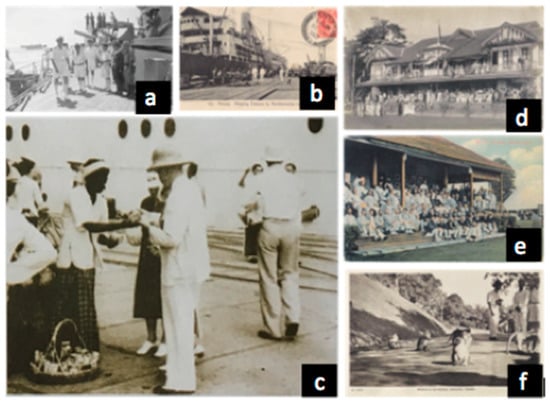

5.4. Garments of British or European Communities in Weld Quay

In the northern area of Weld Quay, rows of government buildings and European merchant companies were built facing the trading port. As for Weld Quay, these were the places where the British and Europeans worked and showed up the most. In the earlier days, government buildings that were built opposite the godowns were mainly for the British colonial governor and civil servants. According to the narrative data given by Informant A, British people who were working as civil servants and colonial officers in those days were dressed up in a white uniform; Informant A described the pants as resembling ‘ma yin tong’ in Cantonese. If the researcher was to directly translate the term ‘ma yin tong’, it could be translated as two chimneys. In other words, Informant A described that the pants worn by the British colonial officer resembling two chimneys at the bottom, as shown in Figure 8a.

Figure 8.

Garments of British ethnic group. (a) British colonial officers having a conference with a Japanese officer on the British Battleship HMS NELSON [67]; (b) European supervisors watching and supervising the loading process in Swettenham Pier ([53]; (c) a close shot of a European supervisor purchasing cigarettes at the Swettenham Pier [53]; (d) British and Europeans attended the occasion of the visit of the Prince of Wales in 1922 [53]; (e) British and Europeans pictured at the Cricket Club Pavilion on the occasion of the Annual Match in 1907 [52]; (f) British or European Visitors found visiting and taking pictures of the monkeys (Cheah, 2012).

Merchant houses at the waterfront of Weld Quay were mostly founded by European entrepreneurs, whereas several companies belonged to the British. Many European workers and supervisors were sent and hired under these companies. Their nature of work was to ensure the trading network and to smoothly run the goods import–export process. In earlier days, European supervisors in white could be seen watching and supervising the goods unloading progress at the Swettenham Pier. Antithetical to the civil officer, they usually wore white long pants when they were working. The related garments were shown in Figure 8b,c.

White shirts and pants had always been the stereotype and a symbol of status for the European and British in the earlier days of Penang. Therefore, the majority of the British and European in those days treated white suits and long pants as well as bowler hats as formal garments whenever they were to attend official occasions. This was also the reason why other prominent ethnic groups assimilated white in their garments to represent and distinguish their status from the others. However, there was certainly an exception in this matter. Black and grey suits can be seen being worn by some British and Europeans on formal occasions as well. These related scenes are shown in Figure 8d,e. As for daily garments, the British dressed slightly casually as compared to the garments for working and occasions. They usually wore collared shirt and buttons that were designed at the shirtfront, tucked into either long pants or shorts, and a belt was also found at the waistband area, as shown in Figure 8f. Figure 9 also shows the recovered and enlarged pictures of Figure 8d,e to emphasize the color code of the British garments.

Figure 9.

The color code of British attire (a) British and Europeans were the majority in White Formal Outfits, attending the occasion of the visit of the Prince of Wales in 1922 [53] and (b) British and Europeans in black and grey attire pictured at the Cricket Club Pavilion on the occasion of the Annual Match in 1907 [52].

Table 4 shows the summary of information and materials of the garments of the four ethnic groups, Chinese, Indian, Malay, and English, that could be found in the old Weld Quay in the aspects of visual data, clothes and their elements, pants and their elements, accessories, and garments for occupational activities.

Table 4.

Summary of information and materials of the garment of each ethnic that could find in the old Weld Quay.

This study following the interpretive and collaborative analysis processes found that the garments of each ethnic group in the early 19th century were affected by their occupations and daily activities. Furthermore, the garments can be distinguished in terms of their social status and ethnicity based on the way they were dressed daily. For the Chinese ethnic group, the lower-class Chinese were mainly stevedores, laborers, or artisans, while the higher-class Chinese worked as merchants or government officers. For the Indian ethnic group, the lower-class Indians worked as laborers and stevedores, while the higher-class Indians were hired to be police officers or sepoys. For the Malay ethnic group, the lower-class Malays were the natives who worked as farmers or fishermen, while the higher-class Malays were working as vendors or traders. Finally, the British ethnic group who were the colonists had only one class (higher) in the old Weld Quay and worked as merchants, colonial officers, or governors.

During the collaborative analysis process, some problems and right-based struggles on verbal and visual resources have been identified. These are seen as weaknesses in cultural studies. Firstly, the oral history might be influenced by own interest and personal invalid judgments, making it reliable and credibly sufficient or otherwise. The results then might change others’ interpretations of the garments in reality during the olden days. Hence, the participants in the policy process are vital, and in this study, not only the interviews that contain reminiscences from the experts are conducted, but also other ‘non-memoirs’ sources such as printed postcards, virtual outputs on the websites, as well as other articles and displays in the museum and galleries. After the researchers have transcribed the oral histories, local knowledge is not neglected. This study also involved the help from informants to observe the visual analysis as well as collecting the oral history from the local community based on the archive audio files in George Town World Heritage Incorporated. Secondly, the processes of patrimonialization and safeguarding should aim to improve the cultural understandings and instill the recognition of their own society, not just enriching the tourism work. Referring to AHD, it serves to provide a solid guidance on protection of heritage but requires investments targeted to SDGs that are meant to preserve and salvage our diversity and intercultural garments. If not rectified in the rightful manner, the work on safeguarding of the ICH of garments is not be able to compete against the rapid evolution of fashion and designs.

This study of material culture has also subsumed the ethnological and ethnographical heritages simultaneously, as the informants’ interviews and observations have not only revealed the occupations and their social status between them based on the characteristics of their garments, but also resulted in providing an indication of their hierarchy. Therefore, the findings of this study on the inhabitant’ daily garments, occupations, and social status suggest that it will serve as pertinent information to visualize the past life of Weld Quay of the early 19th century as a means of digital preservation of cultural heritage.

6. Conclusions

Malaysia is well-known as a multi-racial country, and a unified Malaysian culture is something only emerging in the country. The appreciation of keeping the garments of the past until today continues to exist after the changing nature of this intangible heritage among these four ethnic groups in Weld Quay. For instance, the Malay ethnic group’s garment is very similar to the Indonesian’s, which is an outfit comprised of the blouse, brooch, and sarong that can still occasionally be seen today. Additionally, the Indians are also seen to be wearing saris for ladies and dhotis for men, especially during their religious ceremonies. These signify that people still respect and give value to the garments they once wore a few centuries ago. Some ethnic groups prefer to keep their cultural costume traditions close to their heart. Culture is the identity of the nation that characterizes the functioning of particular populations and even ethnic groups. It is also the basic root of anything that gives them the ways of life. Back in the 19th century, the garments not only show the profession of each ethnic group but the classes and castes. The classes can be identified through their social status in the type of materials that the inhabitants wore and also their skin color. Skin color, often an indicative of less or more time working under the hot tropical sun, further marks class position. The class position in Malaysia today, even with the substantial stratification of society by ethnicity, was also reflected by the type of garments they wear. Furthermore, the multi-cultural trading in the 19th century, which was dominated by the Chinese, has influenced the class positions of today. Similarly, other ethnic groups are experiencing different classes in business and lifestyle through their family money that was passed down from generation to generation during the earlier trading. This can be made evident by the largely Chinese middle class whose prosperous lifestyle leads Malaysia’s shift to a consumer society.

This narrative analysis has successfully revealed a great deal of information about the stories underpinning ICH via interviews. Since the data and elements of the old Weld Quay are long gone and also lacking intangible data, especially in terms of visual data, the narrative analysis method allows the researcher to gather the information from the existing documents, postcards, archives, books, and many more media, even by interviewing to collect more relevant data. Nevertheless, the technique of the intellectual guess is required to match the narrative data. The visual and semiotic analysis then allowed a deeper investigation into the understandings of not only the color and the materials of the inhabitants’ garments but also the relations of their garments to their occupational activities as well as their social status. Therefore, the proposed conceptual framework relied on the step-by-step procedures whereby the narrative analysis validates the correctness of the information of the past. This study also provides guidance in how to conduct narrative analysis to mine historical data in a more explicit manner. The narrative interview of Informants A and B regarding the past life of Weld Quay during the 19th century was insufficient initially. However, the narrative data delivered from both of the informants were found to be lacking evidence if the story was only retold by one of them, which was the limitation of this research. To validate the narrative information of the interviews, a large amount of visual data was cross-checked from many different sources. Therefore, visual analysis, denotation, and connotation have been applied and worked complementarily with the interview to investigate the data and information of the materials of garments of different ethnic groups together with their occupational activities and social status.

In conclusion, this research has prominently gives a recall to the communities, groups, and individuals to give a more specific focus to some thoughts on our material culture. The garments involved in the valuation, identity, sense of belonging, pride, and dignity should not only be preserved but also embraced on a day-to-day basis, such as wearing them to celebrate occasions. Moreover, the local communities are the living heritage. This research brings together two expert narratives and eight other oral stories from the community. The community is the bearer and medium to transmit their knowledge and experiences to the young people. They are also the depositories for ICH, which guarantees the transmissions of our cultural heritage. Younger generations should be encouraged to promote their heritage in all forms whether they are tangible or intangible. As presented in this research, the beauty of material culture is that the garments come from multi-ethnic groups, and the cultural diversity that provides a concept of togetherness as a family is a key concern at the turn of a new century. For future work, we wish to conduct further investigation of the inhabitant garments on the material sources, dyeing methods, clothing makers, production methods, and tailoring tools to supplement the preservation of the ICH in this research.

Author Contributions

Data curation: Y.C.C.; formal analysis: C.K.L. and Y.C.C.; funding acquisition: K.L.T.; investigation: K.L.T. and Y.C.C.; project administration: M.B.M.; supervision: C.K.L., M.B.M., and M.Z.I.; validation: M.F.A. and M.Z.I.; writing—original draft: C.K.L.; writing—review and editing: C.K.L. and M.F.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was conducted by using funding from the research projects of the RAGS/1/2015/ICT04/UPSI/02/1, and the publication of this article is supported by “Dana Pecutan Penerbitan” from Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM.ISP.400-8/6/3).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the informants that are involved for the interview who have told their oral history and also George Town World Heritage Incorporated for other sources of oral history by the community living in George Town.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. World Heritage List. 2016. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/ (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Melaka and George Town, Historic Cities of the Straits of Malacca. United Nations Educational Science and Cultural Organisation. 2017. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/en/decisions/1486 (accessed on 24 March 2020).

- Lim, C.K.; Tan, K.L.; Zaidan, A.A.; Zaidan, B.B. A proposed methodology of bringing past life in digital cultural heritage through crowd simulation: A case study in George Town, Malaysia. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2020, 79, 3387–3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahani, B.M.; Abooali, G.; Mohamed, B. George Town world heritage site: What we have and what we sell? Asian Cult. Hist. 2012, 4, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Application of Jiangxi intangible cultural heritage in modern fashion design. In Proceedings of the 2017 3rd International Conference on Economics, Social Science, Arts, Education and Management Engineering (ESSAEME 2017), Huhhot, China, 29–30 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. 2009. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/doc/src/06859-EN.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Bortolotto, C. The Role of Spatiality in the Practice of the 2003 Convention; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2016; p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- Hafstein, V.T. Cultural heritage. In A Companion to Folklore; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 500–519. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, F. The Participation in the safeguarding of the intangible cultural heritage. Revista dos Sócios do Museu do Povo Galego 2018, 23, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, S. The Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage in England: A Comparative Exploration. Ph.D. Thesis, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Laarse, R. Europe’s Peat Fire: Intangible Heritage and the Crusades for Identity. In Dissonant Heritages and Memories in Contemporary Europe; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 79–134. [Google Scholar]

- Idris, M.Z.; Syed Yusoff, S.O.; Mustaffa, N. Preservation of intangible cultural heritage using advance digital technology: Issues and challenges. J. Arts Res. Educ. 2016, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, W.M.W.; Zin, N.A.M.; Rosdi, F.; Sarim, H.M. Digital preservation of intangible cultural heritage. Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2018, 12, 1373–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.K.; Cani, M.P.; Galvane, Q.; Pettre, J.; Talib, A.Z. Simulation of past life: Controlling agent behaviors from the interactions between ethnic groups. In Proceedings of the 2013 Digital Heritage International Congress (Digital Heritage), Marseille, France, 28 October–1 November 2013; Volume 1, pp. 589–596. [Google Scholar]

- Aristidou, A.; Stavrakis, E.; Chrysanthou, Y. Cypriot Intangible Cultural Heritage: Digitizing Folk Dances; Cyprus Computer Society: Nicosia, Cyprus, 2014; pp. 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Foo, R.; Krishnapillai, G. Preserving the intangible living heritage in the George Town world heritage site, Malaysia. J. Herit. Tour. 2019, 14, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, C.; Breheny, M. Narrative analysis in psychological research: An integrated approach to interpreting stories. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2013, 10, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Fina, A.; Georgakopoulou, A. The Handbook of Narrative Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kivunja, C.; Kuyini, A.B. Understanding and applying research paradigms in educational contexts. Int. J. High. Educ. 2017, 6, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meraz, R.L.; Osteen, K.; McGee, J. Applying multiple methods of systematic evaluation in narrative analysis for greater validity and deeper meaning. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2019, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]