Abstract

In 2016, the Korean government selected carbon capture and utilization (CCU) as one of the national strategic projects and presented a detailed roadmap to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and to create new climate industries through early demonstration of CCU technology. The Korean government also established the 2030 Greenhouse Gas Reduction Roadmap in 2016 and included carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technology in the new energy industry sector as a CCU technology. The Korean government recognizes the importance of CCUS technology as a mid- to long-term measure to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and implements policies related to technological development. The United States (U.S.), Germany, and China also expect CCUS technology to play a major role in reducing greenhouse gases in the industrial sector in terms of climate and energy policy. This study analyzed the CCU-related policies and technological trends in the U.S., Germany, and China, including major climate and energy plans, driving roadmaps, some government-led projects, and institutional support systems. This work also statistically analyzed 447 CCU and CCUS projects in Korea between 2010 and 2017. It is expected to contribute to responding to climate change, promoting domestic greenhouse gas reduction, and creating future growth engines, as well as to be used as basic data for establishing CCU-related policies in Korea.

1. Introduction

The need for carbon capture and utilization (CCU) projects has been raised in various aspects, including the megatrends in the era of climate change and circular economy, in the implementation of means of reduction of greenhouse gas emissions in Korea, and in the creation of future growth engines [1,2,3,4].

In terms of climate change response, a new climate regime on international climate change issues was formulated in 2020 after the Paris Agreement came into force. In addition, the Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) notes that holding the increase in the global average temperature below 2 °C or less is not achievable without the introduction of carbon capture and storage (CCS) if the use of fossil fuels is expected to continue. The International Energy Agency (IEA) recommended a role of CCS of around 9% to achieve the scenario for sustainable development [2,5,6].

In terms of circular economic response, the World Economic Forum (WEF) presented ‘circular economy’ as an international agenda and emphasized the need for CCU technology in 2014. It was pointed out that carbon can be made into a resource through developments and applications of various technologies, such as carbon-dioxide-enhanced oil recovery (CO2-EOR), and it is possible to build proper business models for a circular economy with these technologies. McKinsey (2014) determined that the introduction of carbon prices would promote commercialization of related technologies that currently do not have economic feasibility, which would have the potential to reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) by 2000 Mt per year [2,5,7].

In terms of innovation in major industries and creation of new growth engines, Korean enterprises are exposed to risks rather than opportunities caused by climate change because Korea is an export-driven country and has a large proportion of manufacturing industries with large-scale energy consumption. According to the Korea Energy Economics Institute (KEEI), power generation, petrochemicals, and steel are industries that emit large amounts of greenhouse gases. In particular, the amount of greenhouse gases emitted by the power generation industry accounted for 34 percent of Korea’s greenhouse gas emissions in 2015. Since these industries already have facilities with high levels of energy efficiency, they must overcome current risks through innovative technologies. CCU projects are significant in that they address some limitations of CCS technologies, which are considered common technologies in responding to climate change, and they also create economic value and environmental value at the same time [2,4,8].

The United States (U.S.), Germany, and China are supporting carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technologies through various policies based on the introduction of carbon prices, and are promoting private participation through active government-led financial support in technology development and demonstration stages [1,2,4,9,10,11,12,13,14]

The Korean government selected a CCU project as one of the national strategic projects in 2016 and presented a detailed roadmap for the reduction of greenhouse gases and the creation of the new climate industry through early demonstration of the CCU technology. The 2030 Greenhouse Gas Reduction Roadmap includes the importance of CCUS technologies in the new energy industry sector as a mid- to long-term measure to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and implements policies related to technological developments. In July 2020, the Korean government announced the comprehensive Korean New Deal plan as a new national growth engine. The plan presented a leap from a carbon-dependent economy to a low-carbon economy, suggesting the implementation of the CCUS technology in the field of green industry innovation and ecosystem construction as a major policy of Korea’s Green New Deal plan [2,4].

From 2010 to 2017, about 447 CCUS-related projects were carried out with investments from Korean ministries, such as the Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Energy (MOTIE) and the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT), and some of these projects are currently going on [15].

2. Methods

2.1. Material Collection

In this study, the “Policy recommendations to promote demonstration of carbon capture and utilization” report from the National Strategic Project Group for Carbon Reuse and the POSCO Research Institute (POSRI) was revised and developed, and the policies and research trends related to CCU in the U.S., Germany, China, and Korea were also reviewed. The literature for the review on the CCU-related policies and research trends was obtained from the websites of the relevant public institutions and academic DBs such as SCOPUS, Web of Science, National Digital Science Library (NDSL), DBpia, and Korean studies Information Service System (KISS).

National research and development (R&D) projects related to CCUS were investigated using the data from the MSIT and Korea Institute of Science and Technology Evaluation and Planning (KISTEP).

2.2. Analysis of Data

In this study, CCU- and CCUS-related R&D projects from 2010 to 2017 in Korea were statistically analyzed using the Excel 2016 and SPSS 25 programs.

3. The Concept and Necessity of Carbon Capture and Utilization

The Concept of CCU

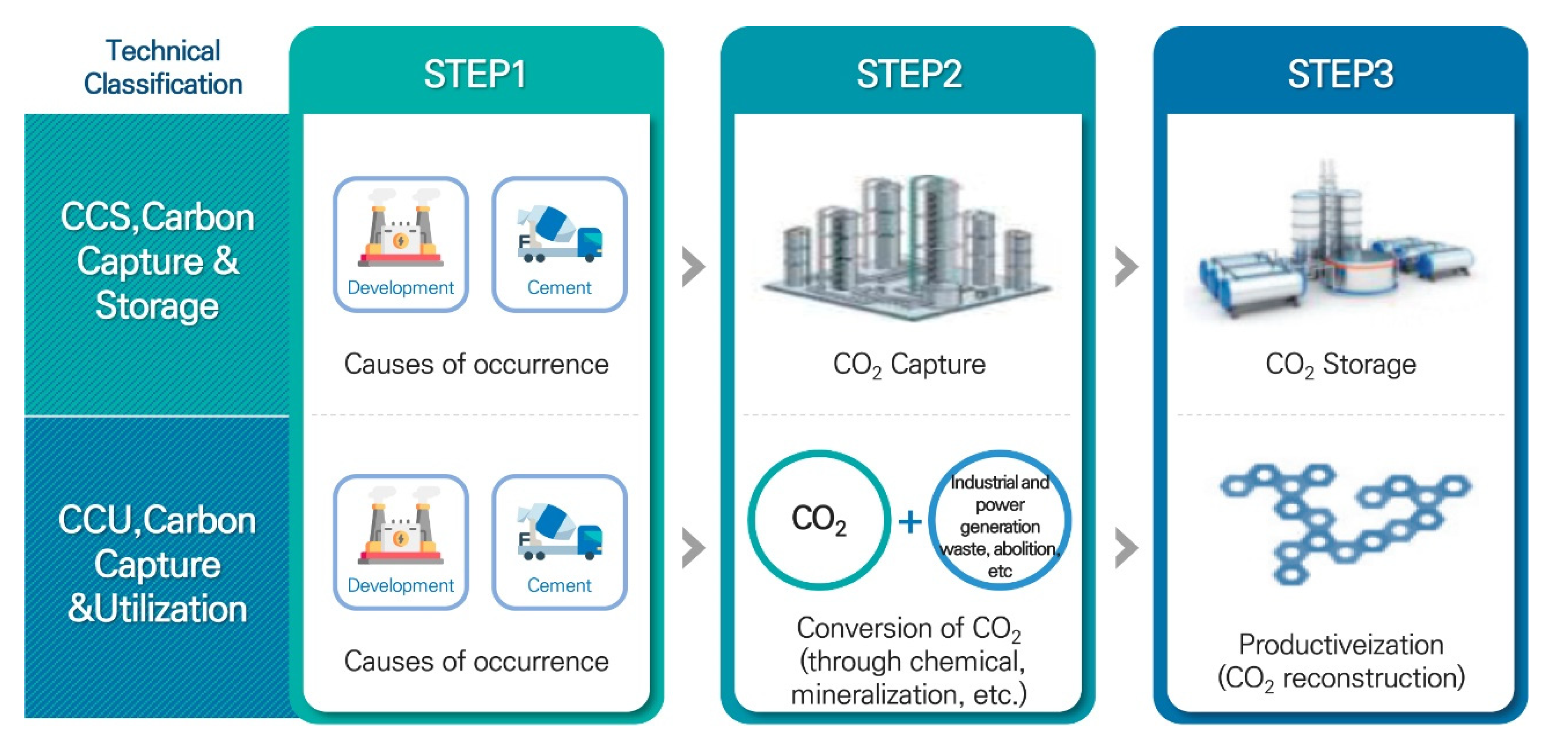

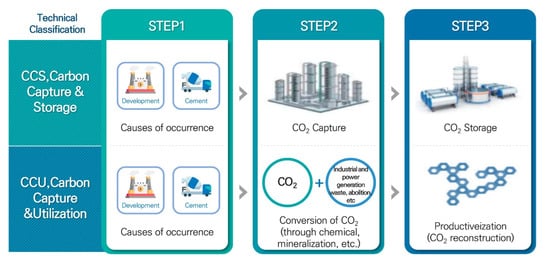

CCS and CCU technologies show differences in purpose and characteristics. CCUS is a concept that combines CCS and CCU. CCS refers to the separation, capture, transport, and storage of carbon in the basement or undersea stratum. CCU technology is defined as the technology for collecting carbon and recycling it as a useful resource. This means using CO2 as a valuable economic resource. CCU technology ranges from capturing carbon dioxide to converting it into value-added compounds [1,2,4,16].

Figure 1 shows a conceptual diagram of the CCS and CCU. The power generation and cement industries are the largest sources of greenhouse gas emissions. In CCS technology, CO2 is collected, stored, and sequestrated by using a liquid absorber (the wet method), by using a solid absorber (the dry method), or by using a film-type membrane (the membrane separation method). In CCU technology, large quantities of CO2 can be produced as high-value-added chemicals through chemical CO2 conversion technology to produce organic acids, plastic raw materials, etc. In CO2 mineralization technology, a low concentration of CO2 (approximately 15%) can be directly induced to react to produce carbonate compounds. Through this process, it is commercialized into cement, abandoned mine filler, and eco-friendly paper [2,4,16,17,18].

Figure 1.

Conceptual diagram of carbon capture and storage (CCS) and carbon capture and utilization (CCU) (adapted from the POSCO research institute, 2018; Korea Carbon Upcycling Research and Development (R&D) Center, 2018).

4. Carbon Capture and Utilization in Major Countries

4.1. CCU-Related Policies and Research Trends in the U.S.

The U.S. government expects CCUS technology to play a major role in reducing greenhouse gases in power generation and industry. However, CCUS technology is often capital-intensive and policy-dependent. This creates a financial burden on the corporate project implementation and risks for investment recovery. In response, the U.S. government plans to reduce risks in the market and to increase private investment by promoting effective incentive schemes. According to the IEA and the Global CCS Institute, it provides CCU-related tax incentives. Table 1 shows the issues by period, such as laws, institutions, and facilities related to CCS and CCU in the U.S. The representative tax benefit is the tax credit for carbon oxide sequestration (the 45Q Tax Credit), which began in 2008. It is the tax regime that deducts as much tax as the amount of CO2 stored and reused. The tax regime deducts 10 USD per ton of CO2, but has been evaluated as ineffective because the tax break is limited to 75 Mt CO2. The amendment of the law passed in 2018. In the amendment, the deduction was increased to 50 USD per ton for sequestrating CO2 and to 35 USD per ton for reusing CO2, and the government also introduced a 12-year period for the benefits instead of removing the quantitative restriction. In addition, Kansas provides a five-year property tax exemption for CCUS facilities, and Mississippi has a 1.5% reduction in income tax [13,14,19,20,21,22,23,24].

Table 1.

Timeline of carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) in the U.S. (adapted from the Global CCS Institute, 2018).

The U.S. is considering new incentives to expand CCUS. For example, in order to ease the financial burden on private companies’ investments, the price of CO2 transactions should be stabilized. The U.S. has the largest CO2 pipeline infrastructure in the world, with a length of 7403 km, capable of transporting 69 million tons of CO2 per year [2,4].

The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) had previously adhered to CCS and CO2-EOR as strategic technologies to reduce national greenhouse gases. As CCU has emerged as a complementary technology, it is being included in the national strategic technology with CCS and is being developed. It is because of the characteristics of CCU technology that it is easy to connect with industrial fields such as the raw material market of the existing petrochemical industry. The representative DOE-supported project and the largest supported project is Skyonic’s project. Skyonic is producing sodium hydrogen carbonate by applying CO2 generated from cement factories to its technology called SkyMine with 25 million USD in support from the DOE. Furthermore, the Alcoa Center in Pennsylvania receives 11,999,359 USD from the DOE, converts the generated CO2 into bicarbonate or carbonate products, and supplies them to the companies that manufacture construction fill materials, green fertilizer, etc. Calera is also working on a project in California using similar technologies with 19,895,553 USD in funding from the DOE. Novomer is working on a demonstration project in southern Louisiana to convert CO2 into polycarbonate, a raw material for plastic products, with 18,417,989 USD in funding from the DOE [2,4].

4.2. CCU-Related Policies and Research Trends in Germany

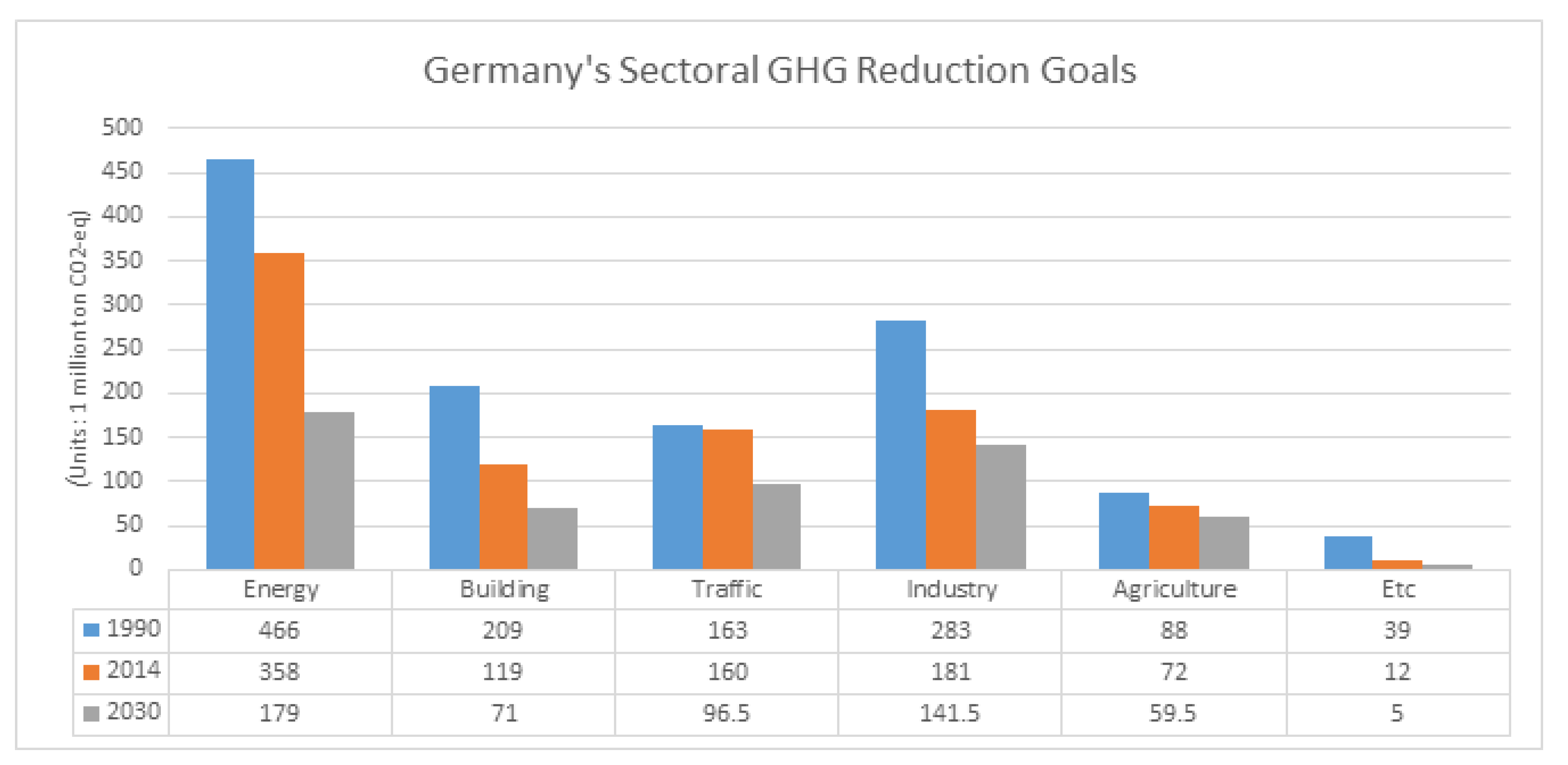

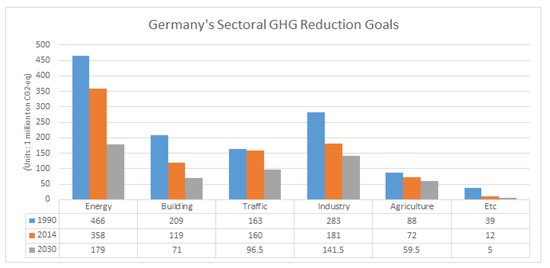

In 2011, Germany announced the Basic Energy Plan (Energykonzept), which envisioned energy policy by 2050, and in 2016, it agreed to the Climate Action Plan 2050 to set the goal of being a greenhouse-gas-neutral country by 2050. Germany’s sectoral greenhouse gas reduction targets are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Germany’s sectoral greenhouse gas reduction goals (data from the German Climate Action Plan 2050, 2016).

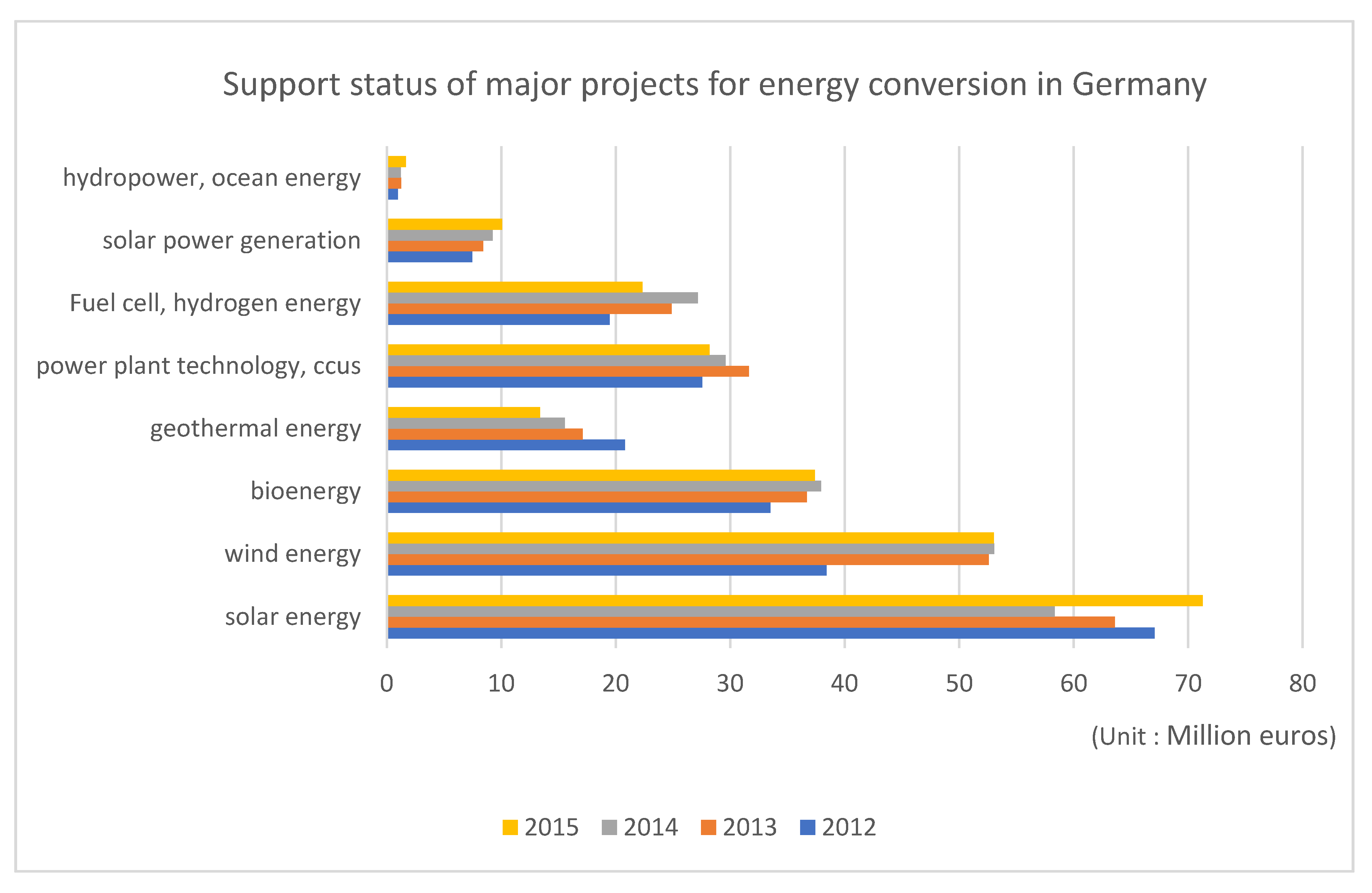

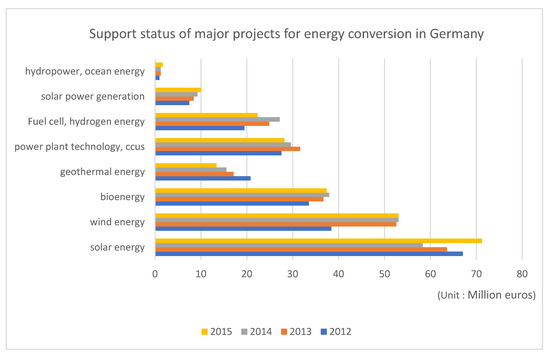

In 2009, the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) conducted a CCU research program, Technologies for Sustainability and Climate Protection: Chemical Processes and Use of CO2. The BMBF invested approximately 100 million EUR in more than 150 projects from 2010 to 2016, and the industry invested 0.5 billion EUR through public–private partnerships. Figure 3 shows the support status of major projects for energy conversion in Germany. According to the German Energy Research Report (Bundesbericht Energieforschung (2016)), Germany provided about 920 million EUR for major projects related to energy conversion from 2012 to 2015, and about 116 million EUR for power plant technology and CCUS, including CCU technology. In the field of energy conversion, this is the most supported field after solar energy at about 260 million EUR, wind energy at about 197 million EUR, and bioenergy at about 150 million EUR [25].

Figure 3.

Support status of major projects for energy conversion in Germany (data from Bundesbericht Energieforschung, 2016).

As a representative government-supported project, Germany’s Bayer Material Science succeeded in developing the world’s first technology for producing high-quality polyurethane foam using CO2 as a raw material. The Bayer Material Science Corporation built a production plant with a scale of thousands of tons in Dormagen and commercialized it in 2015. With the support of the BMBF, they succeeded in manufacturing polyurethane insulation foam using Bayer’s catalyst developed by the Dream production project jointly with RWE Power, a coal-fired power plant, and Siemens. In addition to the BMBF, which provided 5 million EUR for the project, several institutions funded the project, including 6.05 million EUR from Bayer Material Science, 1.25 million EUR from Bayer Technology Services, and 2.7 million EUR from RWTH Achan University and the federal state North Rhine-Westphalia. In addition, the BMBF is providing 60 million EUR in subsidies to the Carbon2Chem Project, which produces basic chemical products using steel by-product gas. The Carbon2Chem Project involves 15 companies in industry and research, including state research institutes, such as the Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft and Max Planck Society, focusing on Thyssenkrupp. Thyssenkrupp succeeded in producing methanol from steel mill gas in September 2018 [26,27,28].

4.3. CCU-Related Policies and Research Trends in China

In 2016, the Chinese government announced the 13th Five-Year Plan aimed at “qualitative growth through innovation,” rather than quantitative growth of key industries. The plan was designed to carry out industrial restructuring by securing manufacturing competitiveness at the level of advanced countries and expanding the service sector. The plan also stresses placing priority on promoting the utilization of renewable energy and reducing CO2. Table 2 shows China’s CCS- and CCU-related laws, policies, and facilities by period [9,13,14,21,29,30,31].

Table 2.

Timeline of CCUS in China (adapted from the Feasibility Study of Development of CCS in Guangdong Province (GDCCSR), 2013; Global CCS Institute, 2018; KEPCO Research Institute, 2019).

China announced the CCUS-related technology roadmap in 2011. The main content of the roadmap was the selection of technology introduction priorities and detailed action plans, and the goals for 2015, 2020, and 2030 are categorized into basic technology development, full-chain project development, and CCUS commercialization. In 2013, China announced the CCUS roadmap for Guangdong Province in 2013 through the Feasibility Study of Development of CCS in Guangdong Province (GDCCSR) project. The proposed CCUS Development Roadmap for Guangdong Province provided a step-by-step economical and technologically feasible guideline with the aim of starting the commercial development of CCUS in Guangdong Province in 2030 [30,32,33].

In 2018, China established the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE), combining the functions of the Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP) and of six government agencies [34]. Mitigating climate change is one of the key elements of the MEE’s role. It includes funding for CCS research projects promoted by the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST), revising guidelines for the CCUS-project-linked environmental impact assessment, and promoting low-carbon technologies around CCUS [35,36,37].

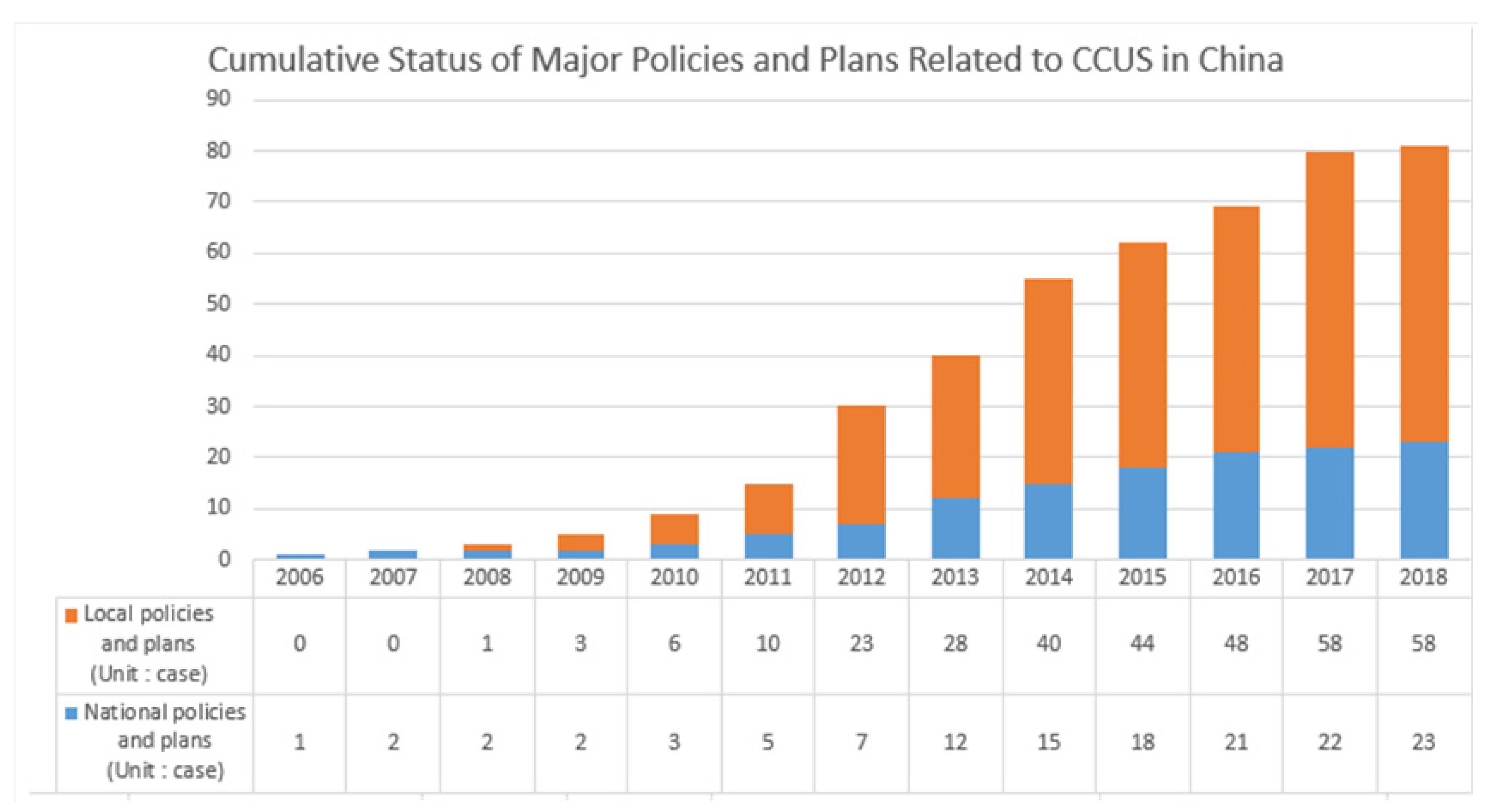

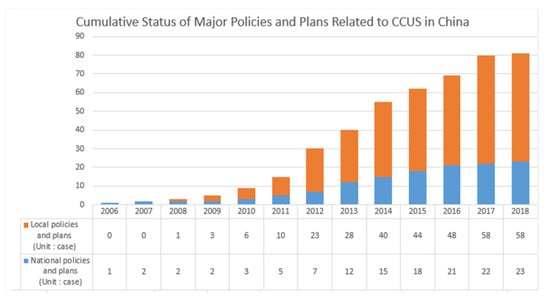

According to the MEE, in 2019, China sought to increase support for CCUS technology and to systematically promote technological development in terms of policies and regulations through the CCUS Technology Roadmap. In terms of technology, there were more than 10 CCUS R&D projects and demonstration projects supported by the National Key Research and Development Plan in 2019. For capacity building, a special committee for CCUS was established under the Chinese Society for Environmental Sciences (CSES). China decided that CCUS needed a national policy that fits its strategic position, as it entails multi-industry cooperation and enormous investment. The cumulative statistics of the policies and plans for CCUS are shown in Figure 4 [35,37].

Figure 4.

Cumulative status of major policies and plans related to CCUS in China (data from the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, 2019).

5. Policy and Research Trends for Carbon Capture and Utilization in Korea

5.1. CCU-Related Policies in Korea

Korea selected CCU as one of the national strategic projects at the Second Science and Technology Strategy Conference in August 2016 for its policy on CCU, presenting a detailed roadmap for the reduction of greenhouse gases and for the creation of new climate industries through early demonstration of CCU technologies [4].

In December 2016, the 2030 Greenhouse Gas Reduction Roadmap was announced, and, by including CCU technology in the new energy industry, the importance of CCUS as a medium- to long-term greenhouse gas reduction means was recognized, and policies related to technology development were promoted [4].

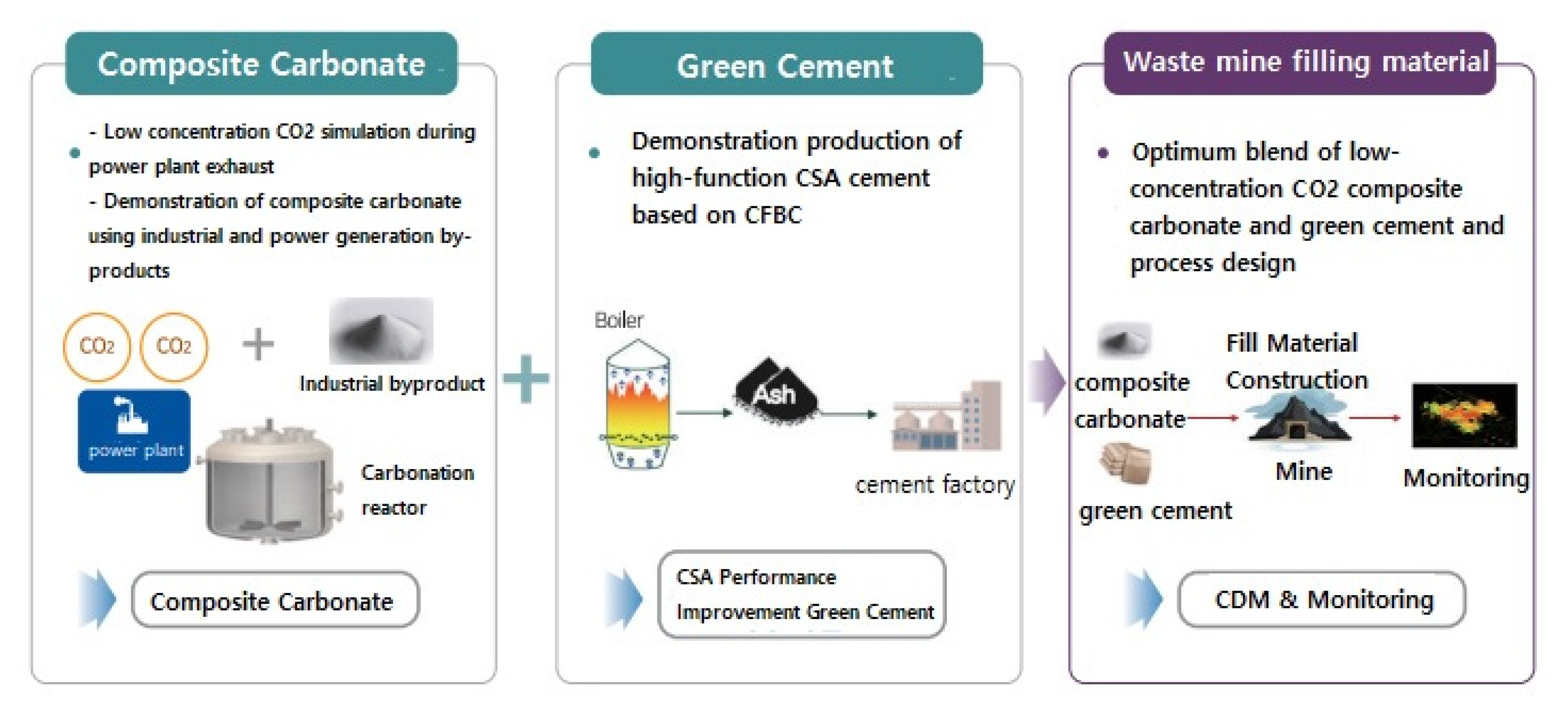

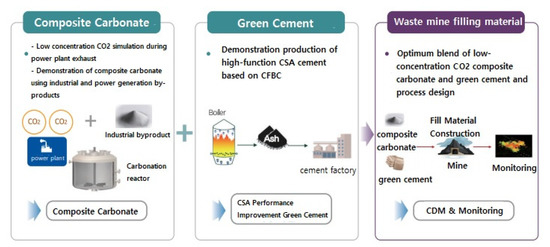

Since 2017, the MSIT, the MOTIE, and the Ministry of Environment (ME) have been promoting the National Strategic Project for Carbon Reuse as a representative CCU project. The Korea Institute of Geoscience and Mineral Resources (KIGAM) is conducting empirical research. Figure 5 shows the technological system of the Carbon Mineralization Flagship Project in the National Strategic Project for Carbon Reuse, which is being carried out by the Korea Institute of Geoscience and Mineral Resources [3,37,38].

Figure 5.

The technological system of the Carbon Mineralization Flagship Project in the National Strategic Project for Carbon Reuse (adapted from the Korea Carbon Upcycling R&D Center, 2018).

5.2. CCU-Related Research Trends in Korea

South Korea’s CCUS-related ministries include the MOTIE, the MSIT, the ME, the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries (MOF), the Ministry of Education (MOE), and the Small and Medium Business Administration (MSS). From 2010 to 2017, these ministries invested about 3475 billion KRW in CCUS-related projects and led government-funded research institutes and other related institutions to conduct research on 447 national R&D projects [15].

In order to analyze the trends in the CCU-related research in Korea, CCUS-related projects conducted by major ministries from 2010 to 2017 were studied according to the criteria of technology field, competent ministries, and year.

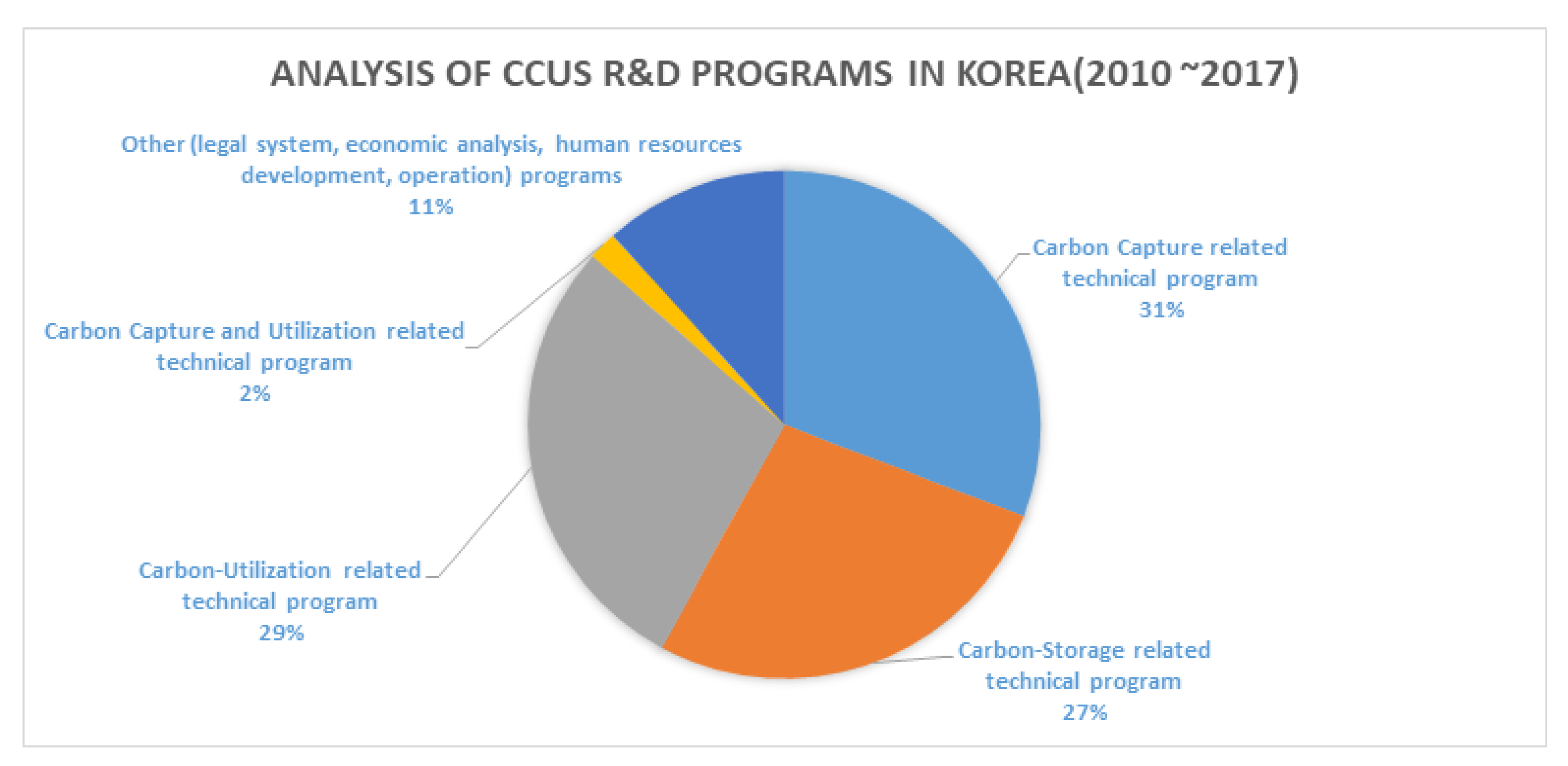

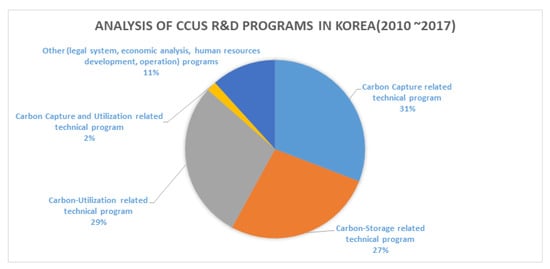

The national CCUS R&D project database (DB) of MSIT and KISTEP from 2010 to 2017 was analyzed. The DBs about technology sectors were classified into five major technical areas: (1) CO2-capture-related technical projects, (2) CO2-sequestration-related technical projects, (3) technical CO2 conversion/utilization projects, (4) technical CO2 capture/conversion projects, and (5) other CO2-related projects (laws, economic analyses, human resource developments, project operations, etc.). Figure 6 shows the results of the analysis of the Korean CCUS R&D programs [15].

Figure 6.

Analysis of CCUS R&D projects in Korea from 2010 to 2017 (data from the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT) and Korea Institute of Science and Technology Evaluation and Planning (KISTEP), 2018).

Among the total 447 R&D projects, (1) technical CO2-capture-related projects were the most with 138 cases (31%), (2) technical CO2-sequestration-related projects accounted for 121 cases (27%), (3) technical CO2-conversion-/utilization-related projects accounted for 128 cases (29%), (4) technical CO2-capture-/conversion-related tasks accounted for eight cases (2%), and (5) other CO2-related projects (laws, economic analyses, human resource developments, project operations, etc.) accounted for 52 cases (11%).

Research was conducted evenly within the range of 27% to 31% for all technologies, but it was found that the proportion of convergence projects such as CO2 capture/conversion technology projects was found to be relatively lower than that of single technology projects.

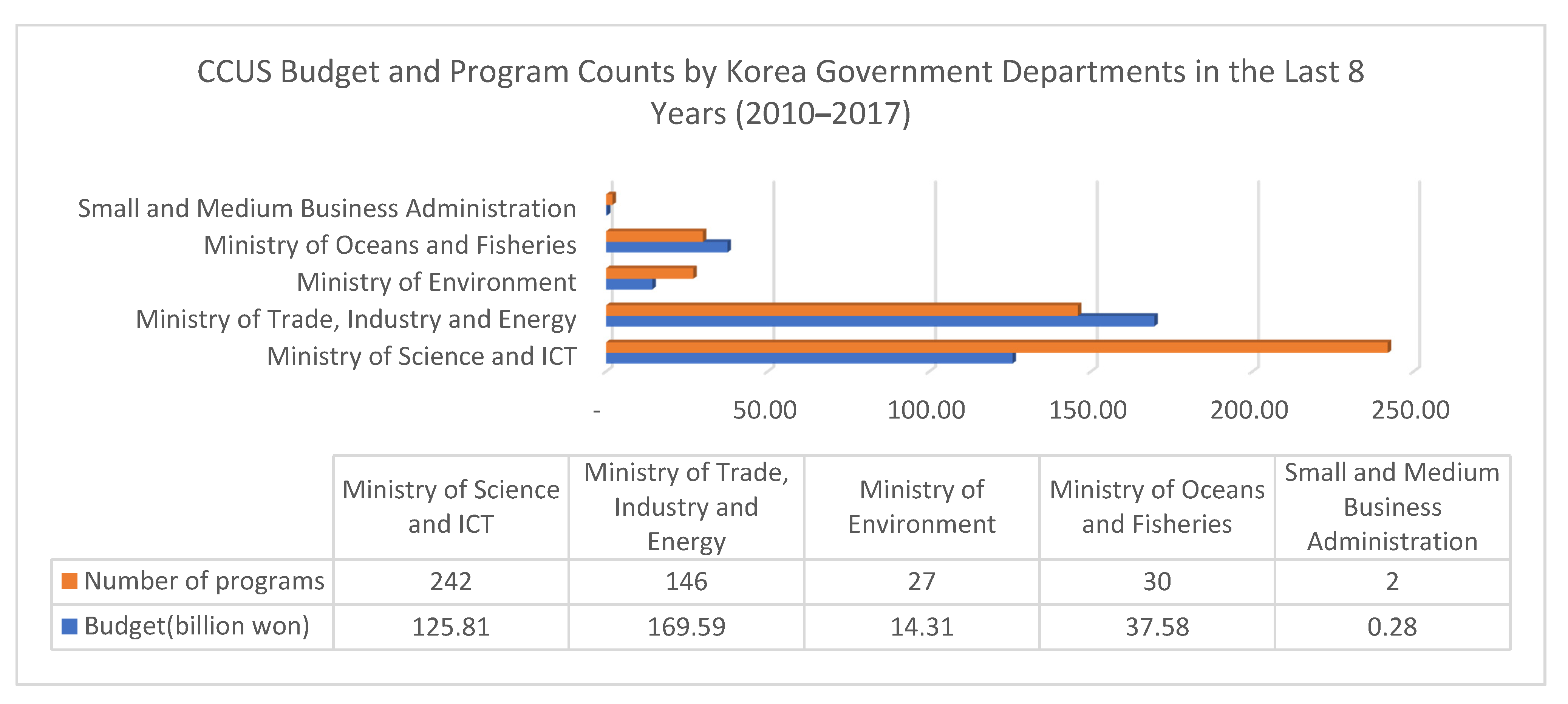

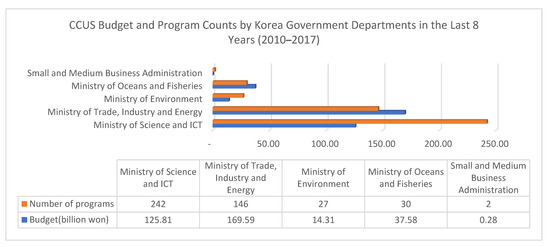

Figure 7 shows the number of CCUS-related projects and subsidies from ministries from 2010 to 2017. The number of tasks for each government department was in the order of MSIT (242 cases), MOTIE (146 cases), MOF (30 cases), ME (27 cases), and MSS (two cases), among which the Ministry of Science and ICT performed the most tasks. The MOTIE (1695.9 billion KRW), the MSIT (1258.1 billion KRW), the MOF (375.7 billion KRW), the ME (143.1 billion KRW), and the MSS (2.8 billion KRW) contributed the most research funds.

Figure 7.

CCUS budget and program counts by parts of the Korean government in the last eight years (2010–2017) (data from the MSIT and KISTEP, 2018).

The Ministry of Industry and Commerce contributed the largest amount of research funds, in the following order: Ministry of Industry and Commerce (169.59 billion won), Ministry of Science and ICT (125.81 billion KRW), Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries (37.58 billion KRW), Ministry of Environment (14.31 billion KRW), and Small and Medium Business Administration (0.28 billion KRW). The contributions per project were more than twice as high as those of other ministries, such as the Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries (0.125 billion KRW) and the Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Energy (1.16 billion KRW). The representative projects of the Ministry of Science and ICT were the KOREA CCS 2020 and the National Strategic Project for Carbon Reuse, while the representative projects of the Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Energy were the Greenhouse Gas Processing Technology Development Project.

The representative projects of the MSIT were KOREA CCS 2020 and the National Strategic Project for Carbon Reuse, while the representative project of the MOTIE was the Greenhouse Gas Processing Technology Development Project. The representative projects of the MOF were CO2 Marine Underground Storage Technology Development Project and Marine CCS Technology Development Project, while the representative projects of the ME were CO2 Storage Environment Management Technology Development Project and CO2 Underground Storage Environmental Management Technology Development Project. The MSS promoted the Development of Amino-Acid-Containing Active Carbon for Carbon Dioxide Absorption [4,39,40].

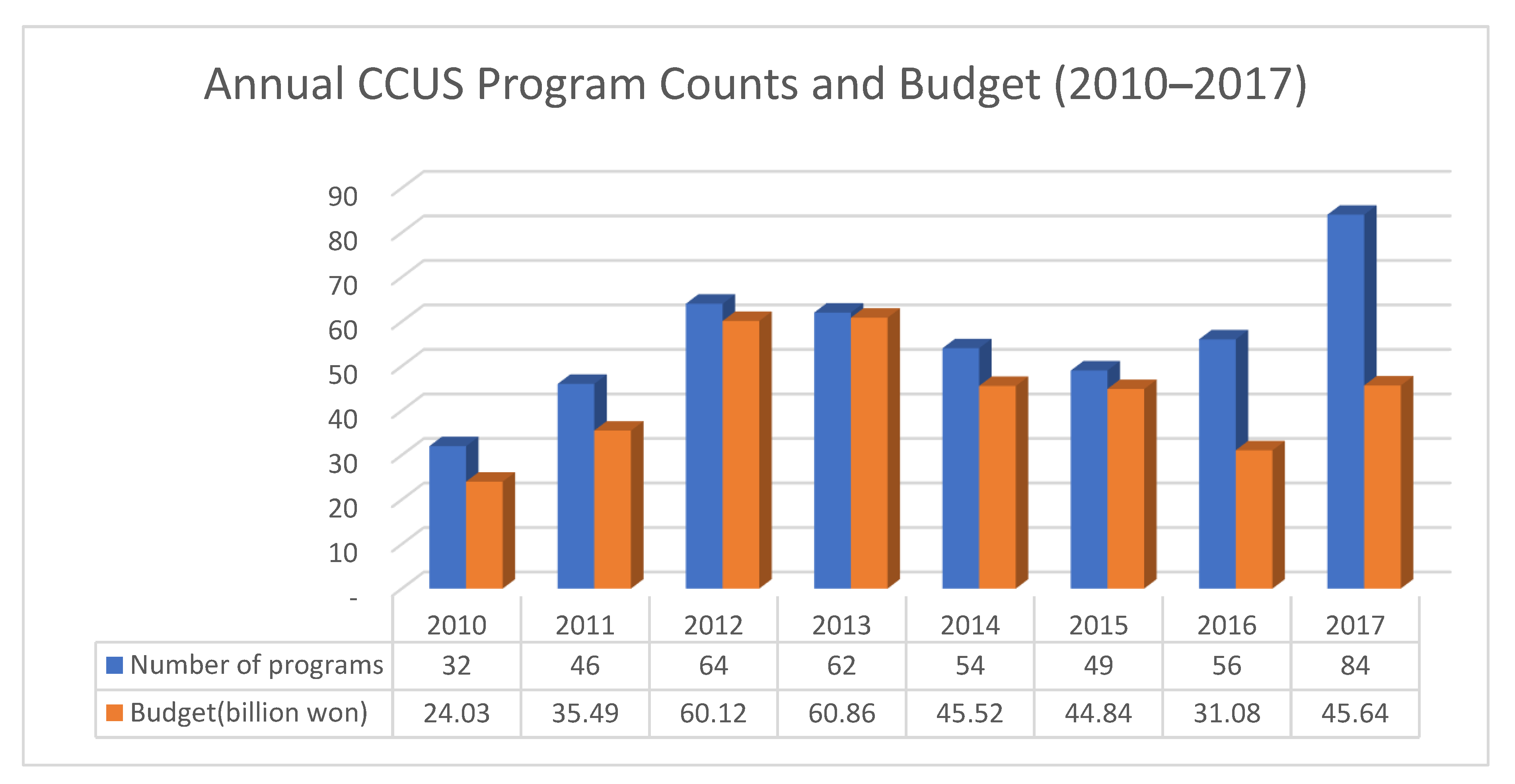

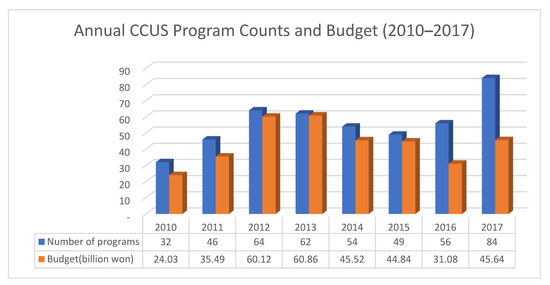

Figure 8 shows the number and budgets of CCUS-related projects by year from 2010 to 2017. The number of projects was the highest in 2017 with 84 cases and the smallest in 2010 with 32 cases. In 2013 and 2012, the government funding was about 60.85 billion for 62 cases and 60.12 billion for 64 cases, respectively, with a small amount of government funding in 2010 with 24.02 for 32 cases. The results of correlation analysis between the number of projects and the budgets using Pearson’s linear correlation coefficient were not statistically significant. The results may come from the differences in research expenses per project depending on project characteristics, such as mini-pilot infrastructure construction and demonstration projects.

Figure 8.

Annual CCUS program counts and budget (2010–2017) (data from the MSIT and KISTEP, 2018).

6. Conclusions

The U.S., Germany, and China are supporting the development and commercialization of CCUS-related technologies, including CCU, by combining various policy measures. The CCUS support policies are classified into support for capital and operating expenses, support for risk minimization, and support for carbon sequestration. These support systems are most commonly implemented through tax breaks or subsidies. In addition, this supports from governments serves to mitigate business risks for project participants. Moreover, the support for policy was provided through systems like the feed-in tariff (FIT), issuance of CCS certificates, and contract for difference (CfD).

Korea is carrying out the National Strategic Project for Carbon Reuse from 2017 to 2022, which is related to CCU as a representative project of all ministries, and 447 projects related to CCUS received investments of about 347.5 billion KRW from 2010 to 2017. The MSIT and the MOTIE managed 388 projects and invested about 295.4 billion KRW for these projects.

By field, research is being conducted evenly on single-field technical projects, such as CO2-capture-related technology, CO2-conversion-/utilization-related technology, and CO2-sequestration-related technology. On the other hand, since the ratio of convergence projects, such as CO2-capture-/conversion-related technologies, is as low as 2%, it is deemed necessary to promote convergence technology research in project planning in order to advance technologies and improve linkage between fields.

The government subsidies and the number of projects by year did not show a significant correlation, which is estimated to be due to the differences in budgets according to the characteristics of the projects, such as infrastructure construction, like the Mini-Pilot.

This paper aims to utilize the results of CCU-related policy and project analysis for major countries as basic data for policy proposals for future climate change responses, and to contribute to the implementation of domestic greenhouse gas reduction and the creation of future growth engines through further CCU-related research.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, investigation, S.-h.J.; investigation, S.-h.L.; writing—review and editing, J.M.; conceptualization, editing, M.-h.L.; project administration, supervision, writing—review and editing, J.W.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Strategic Project for Carbon Mineralization of the Flagship Center of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT), the Ministry of Environment (ME), and the Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Energy (MOTIE) 2019M3D8A2112963.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing personal relationships and financial interests that could influence the present work.

References

- Chin, Y.; Kim, S. Carbon Dioxide (CO2), The Main Culprit of Climate Change, Is the Potential for Future Resources? Posco Research Institute (POSRI) Issue Report; POSRI: Seoul, Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, Y.; Kim, S. Policy Recommendations to Promote Demonstration of Carbon Capture and Utilization; Posco Research Institute (POSRI) Issue Report; POSRI: Seoul, Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, S. Korea Carbon Upcycling R&D Center Brochure; Korea Carbon Resources Institute: Seoul, Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, S.; Lee, K.; Jing, Y. An Analysis of Carbon Resources Policy Trends in Major Countries; The Korean Society for Technology Management & Economics: Seoul, Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- OECD iLibrary. IEA World Energy Outlook. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1787/20725302 (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- UNEP. The Emissions Gap Report 2017—A UN Environment Synthesis Report; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. Towards the Circular Economy: Accelerating the Scale-Up across Global Supply Chains; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Element Energy. Demonstrating CO2 Capture in the UK Cement, Chemicals, Iron and Steel and Oil Refining Sectors by 2025: A Techno-Economic Study; Element Energy: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jihyun, L.; Nosang, K. Development of BM for Overseas Market Advancement of CO2 Collective Technology after KEPCO Combustion and Promotion of Technology Commercialization in China; NICE: Seoul, Korea, 2019; pp. 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, J.-T.; Liu, L.-C.; Li, X.; Jia, L. Positioning and revision of CCUS technology development in China. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2016, 46, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada. Turning the Corner: Regulatory Framework for Industrial Greenhouse Gas Emissions; Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning. The Conversion of Ideas, Carbon Resourceization That Turns Greenhouse Gases into Energy, R&D KIOSK National Research and Development Project Information Guide No. 33; Korea Institute of Science & Technology Evaluation and Planning: Seoul, Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Global CCS Institute. The Global Status of CCS 2017; Global CCS Institute: Docklands, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Global CCS Institute. The Global Status of CCS 2018; Global CCS Institute: Docklands, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Kim, K. CCUS R&D Projects DB from 2010 to 2017; Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning, Korea Institute of Science & Technology Evaluation and Planning: Seoul, Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, J.; Jo, H.; Lee, K.; Lee, H.; Kim, J.; Jung, S. Economic Evaluation and Commercialization Plan of CO2 Mineralization Technology; Science & Technology Policy Institute (STEPI) Policy Research: Seoul, Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Carbon Dioxide Utilisation Network. Available online: http://co2chem.co.uk (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- Greenhouse Gas Inventory and Research Center. A Basic Study on the Calculation of Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Using CCU Technology; Greenhouse Gas Inventory and Research Center: Seoul, Korea, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Congressional Research Service. Available online: https://crsreports.congress.gov (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- Congressional Research Service. The Tax Credit for Carbon Sequestration (Section 45Q); Congressional Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- Global CCS Institue. Available online: http://www.globalccsinstitute.com (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- IEA. 20 Years of Carbon Capture and Storage: Accelerating Future Deployment; IEA: Paris, France, 2016; Available online: https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264267800-en (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- IEA. Five Keys to Unlock CCS Investment; IEA: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- IEA. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/transforming-industry-through-ccus (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety (BMUB). Clim. Action Plan 2050; BMUB: Berlin, Germany, 2016.

- Deerberg, G.; Oles, M.; Schlögl, R. The Project Carbon2Chem®. Chemie Ingenieur Technik 2018, 90, 1365–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green Car Congress. Available online: https://www.greencarcongress.com/2019/01/20190111-thyssenkrupp.html (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- ThyssenKrupp. Available online: https://engineered.thyssenkrupp.com/en/milestone-for-climate-protection-carbon2chem-pilot-plant-opened (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- Jiang, K.; Ashworth, P.; Zhang, S.; Liang, X.; Sun, Y.; Angus, D. China’s carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) policy: A critical review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 119, 109601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Liao, C.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, D.; Li, P.; Liu, Q.; Li, X.; Bai, B.; Li, J.; Gibbins, J.; et al. CCUS Development Roadmap Study for Guangdong Province, China Feasibility Study of CCS-Readiness in Guangdong Province (GDCCSR); Global CCS Institute: Melbourne, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Wei, Y.; Liu, L.; Kang, J. Progress and Layout of Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage in China; Clean Energy Ministerial CCUS Initiative Webinar: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Asian Development Bank (ADB). Roadmap for Carbon Capture and Storage Demonstration and Deployment in the the People’s Republic of China; Asian Development Bank (ADB): Mandaluyong, Philippines, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Global CCS Institute. Guangzhou Institute of Energy Conversion, CCUS Development Roadmap Study for Guangdong Province, China; Global CCS Institute: Docklands, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, J. SkyMine Beneficial CO2 Use Project; Skyonic Corporation: Austin, TX, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment. China’s Policies and Actions for Addressing Climate Change; Ministry of Ecology and Environment: Beijing, China, 2019.

- The US-China Business Council. Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE); The US-China Business Council: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment. China Status of CO2 Capture Utilization and Storage (CCUS); Ministry of Ecology and Environment: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Presidential Advisory Council on Science and Technology. Development Strategies of Carbon Resources for the Response of the New Climate System and Scientific Diplomacy Enhancement Plan; Presidential Advisory Council on Science and Technology: Seoul, Korea, 2016.

- Korea CCS Association. Analysis of Domestic and Foreign Carbon Dioxide Utilization Technology for the Generation of Carbon Dioxide Utilization Industry; Korea CCS Association: Seoul, Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Institute of Science & Technology Evaluation and Planning. Current Status and Policy Trends of Carbon Capture & Storage (CCS) Technology as a Major Green Technology for Green GHG Response and Low Carbon Green Growth; Korea Institute of Science & Technology Evaluation and Planning: Seoul, Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).