Developmental Sustainability through Heritage Preservation: Two Chinese Case Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction: The Role of Cultural Heritage Preservation

2. Methodology

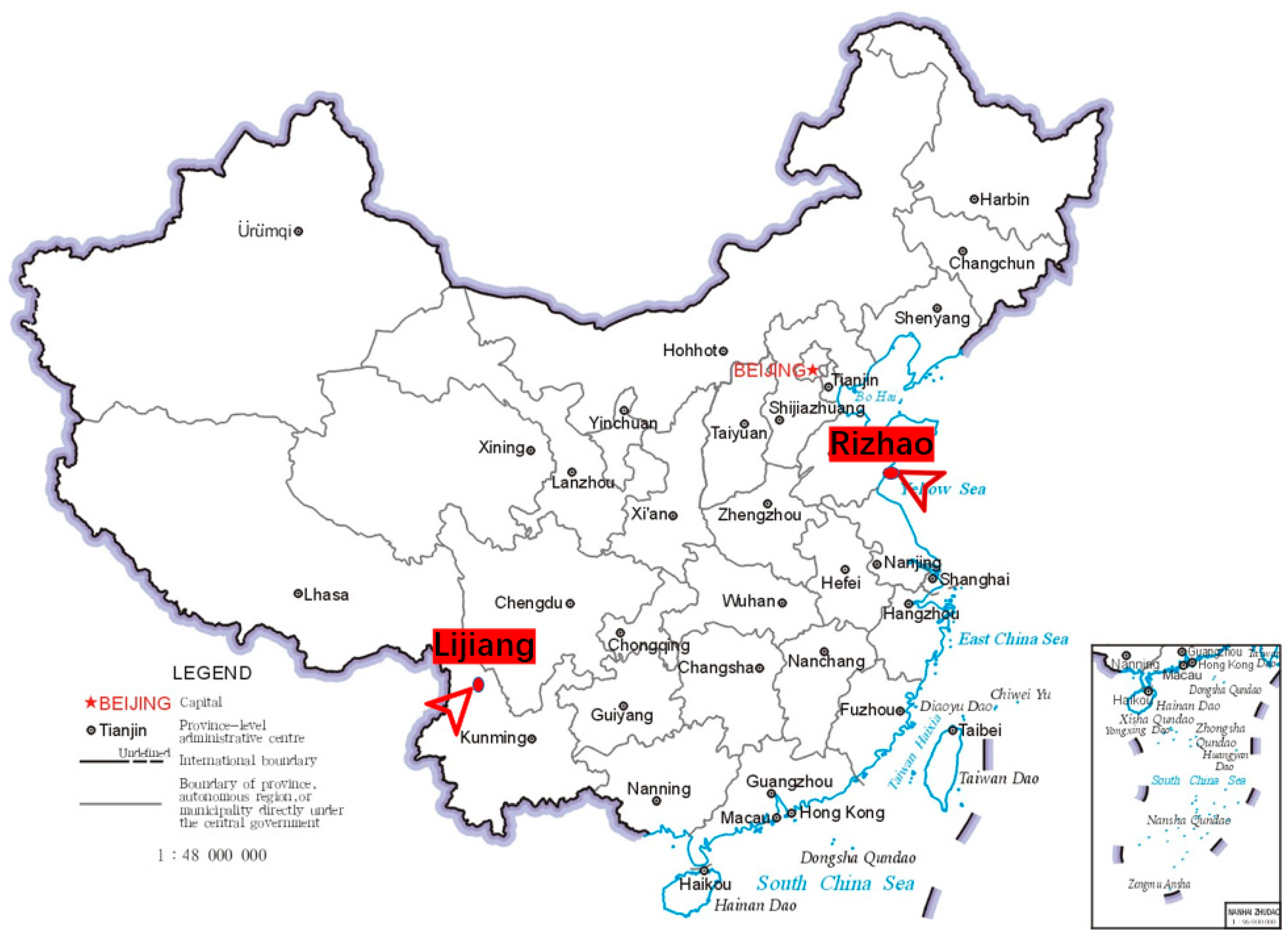

3. Study Context

4. Analysis: Cultural Heritage Protection through Rural Rejuvenation

5. Empirical Analaysis: Pairing Tourism with Intangible Cultural Heritage Protection—Two Case Studies

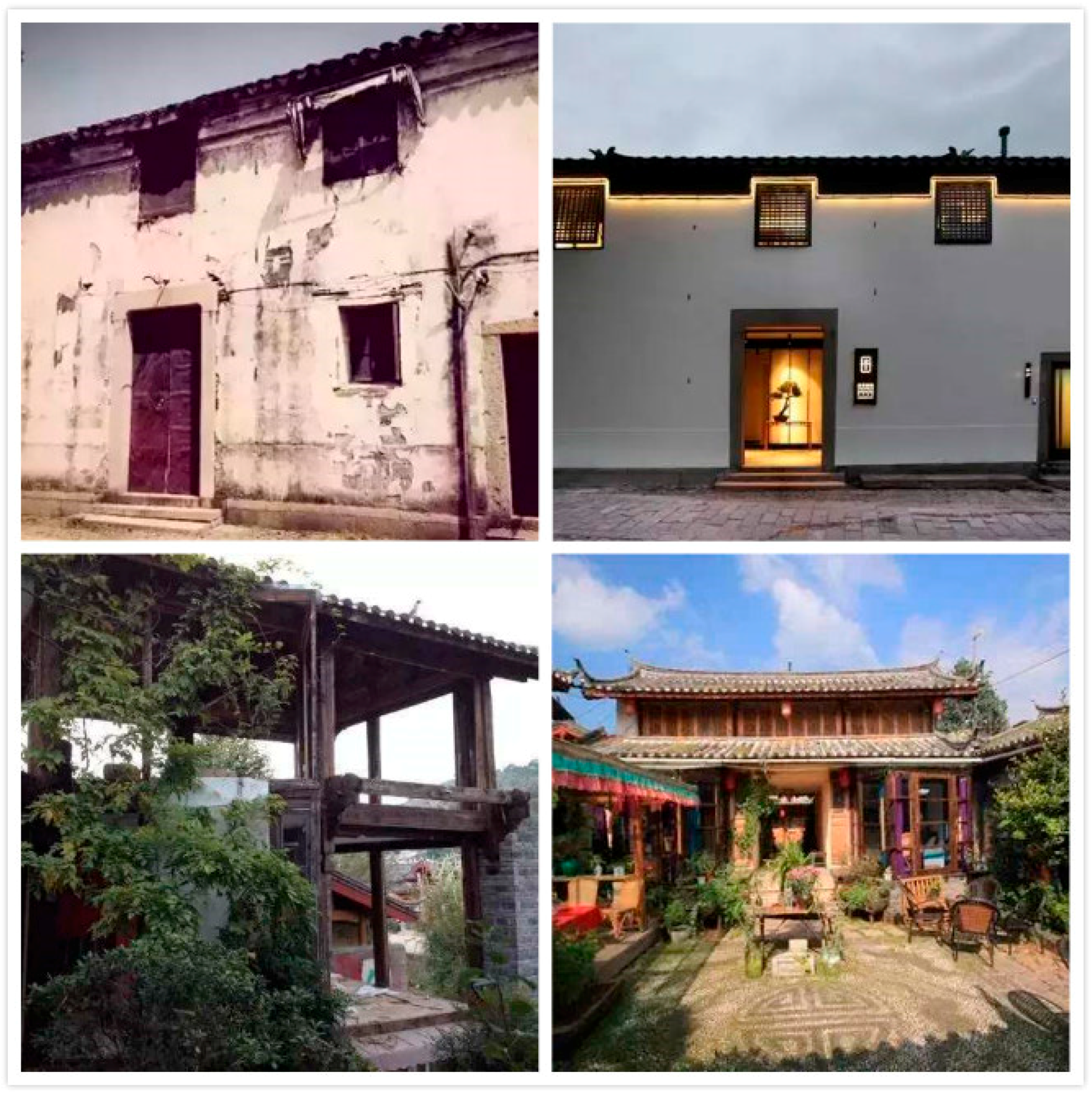

5.1. Case Study 1: Successful Commercialization—Lijiang

5.2. Case Study 2: At the Crossroads—Rizhao and Its Fishermen’s Festival Dances

5.3. Comparing Lijiang with Rizhao

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wilkinson, S.; Remey, H. “Heritage Building Preservation vs. Sustainability: Conflict Isn’t Inevitable”, The Conversation 29 November 2017. Available online: https://theconversation.com/heritage-building-preservation-vs-sustainability-conflict-isnt-inevitable-83973 (accessed on 26 June 2019).

- Basu, P.; Modest, W. (Eds.) Museums, Heritage and International Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tadros, M. “Should Development Concern Itself with Cultural Heritage Preservation?” Institute of Development Studies, 14 February 2018. Available online: https://www.ids.ac.uk/opinions/should-development-concern-itself-with-cultural-heritage-preservation/ (accessed on 24 June 2019).

- Avrami, E. Making Historic Preservation Sustainable. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2016, 82, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolotto, C. From objects to processes: UNESCO’s ‘intangible cultural heritage’. J. Mus. Ethnogr. 2007, 19, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Safford, L.B. Cultural Heritage Preservation in Modern China: Problems, Perspectives, and Potentials. ASIANetwork Exch. A J. Asian Stud. Lib. Arts 2014, 21, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). Our Common Future: From One Earth to One World; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, G. China’s architectural heritage conservation movement. Front. Archit. Res. 2012, 1, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. The conservation of intangible cultural heritage in historic areas. In Proceedings of the 16th ICOMOS General Assembly and International Symposium: ‘Finding the Spirit of Place—Between the Tangible and the Intangible’, Quebec, QC, Canada, 29 September–4 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Iossifova, D. China: Toward an integrated approach to cultural heritage preservation and economic development. CityCity Mag. 2014, 2014, 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Rees, H. Intangible Cultural Heritage Protection in China, Asia Dialogue 25 July 2017. Available online: https://theasiadialogue.com/2017/07/25/intangible-cultural-heritage-protection-in-china/ (accessed on 25 July 2017).

- Tadros, M. “Cultural Heritage Preservation: Development’s Enabling Role?” Institute of Development Studies, 23 February 2018. Available online: https://www.ids.ac.uk/opinions/cultural-heritage-preservation-developments-enabling-role/ (accessed on 23 June 2019).

- Rypkema, D. Culture, Historic Preservation and Economic Development in the 21st Century. In Proceedings of the Leadership Conference on Conservancy and Development, Yunnan Province, China, 26 September 1999; Available online: http://www.columbia.edu/cu/china/DRPAP.html (accessed on 25 June 2019).

- Roe, E. Narrative Policy Analysis; Duke University Press: Durham, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.-S.; Li, Y.; Du, G. Quantifying spatio-temporal patterns of urban expansion in Beijing during 1985–2013 with rural-urban development transformation. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, A.B. The Trade-off between Economic Development, Heritage Preservation in Urban Southeast Asia, 26 April 2016. Available online: https://blogs.adb.org/blog/trade-between-economic-development-heritage-preservation-urban-southeast-asia (accessed on 25 June 2019).

- Xue, L.; Kerstetter, D.; Hunt, C.A. Tourism development and changing rural identity in China. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 66, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takako, I. Preservation of traditional art: The case of the nooraa performance in Southern Thailand. Wacana Seni J. Arts Discourse 2008, 7, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mualam, N.; Alterman, R. Architecture is not everything: A multi-faceted conceptual framework for evaluating heritage protection policies and disputes. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2018, 26, 291–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.J.; Musschetto, V. Reconciling Preservation and Sustainability, 3 February. Available online: https://www.architectmagazine.com/technology/reconciling-preservation-and-sustainability_o (accessed on 26 June 2019).

- You, Z. Shifting Actors and Power Relations: Contentious Local Responses to the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Contemporary China. J. Folk. Res. Int. J. Folk. Ethnomusicol. 2015, 52, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; Ho, P.S.; Du Cros, H. Relationship between tourism and cultural heritage management: Evidence from Hong Kong. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.; Ma, S. Heritage preservation and sustainability of China’s development. Sustain. Dev. 2004, 12, 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. The Conservation of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Historic Areas. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277990262_The_conservation_of_intangible_cultural_heritage_in_historic_areas (accessed on 11 June 2008).

- Shen, C.; Chen, H.; Messenger, P.M.; Smith, G.S. Cultural Heritage Management in China. Cult. Herit. Manag. 2010, 5, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Z. Legal prospection of cultural heritage in China: A challenge to keep history alive. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2015, 22, 497–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petronela, T. The Importance of the Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Economy. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 39, 731–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, M. “Cultural Heritage Conservation in China—Practices and Achievements in the Twenty-First Century”, The Getty Conservation Institute, 26 September 2016. Available online: https://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/newsletters/31_1/practices_achievements.html (accessed on 11 June 2019).

- Xinhuanet “China Forms Intangible Cultural Heritage Protection Network”, 31 May 2019. Available online: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-05/31/c_138105950.htm (accessed on 11 August 2019).

- Zhuang, P. “China Plans Law to Make Reviving Rural Areas Apriority in Modernization Push”, South China Morning Post, 10 March 2019. Available online: https://www.scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/2189358/china-plans-law-make-reviving-rural-areas-priority-modernisation (accessed on 3 July 2019).

- Lewis, W.A. Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labour. Manch. Sch. 1954, 22, 139–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; LeGates, R.; Fang, C. From coordinated to integrated urban and rural development in China’s megacity regions. J. Urban Aff. 2018, 41, 150–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; LeGates, R.; Zhao, M.; Fang, C. The changing rural-urban divide in China’s megacities. Cities 2018, 81, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.X.B.; Wong, K.K. The sustainability dilemma of China’s township and village enterprises: An analysis from spatial and functional perspectives. J. Rural. Stud. 2002, 18, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Jiang, G.; Zhang, R.; Zheng, Q.; Ma, W.; Zhao, Q.; Li, Y. Addressing the rural in situ urbanization (RISU) in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region: Spatio-temporal pattern and driving mechanism. Cities 2018, 75, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Ma, J.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, Y.; Yue, Y. Spatial-temporal change of land surface temperature across 285 cities in China: An urban-rural contrast perspective. Sci. Total. Environ. 2018, 635, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, M.; Cheong, K.C. Stakeholder perspectives of China’s land consolidation program: A case study of Dongnan Village, Shandong Province. Habitat Int. 2014, 43, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Yu, D. China’s New Urbanization Developmental Paths; Blueprints and Patterns; Springer Geography: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, C.; Song, Y.; He, Q.; Liu, Y. Urban–rural income change: Influences of landscape pattern and administrative spatial spillover effect. Appl. Geogr. 2018, 97, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, N.; Zhao, B. Spatio-temporal evolutionary characteristics of county-level in China since the reform and opening-up. Resour. Dev. Mark. 2019, 35, 359–365. [Google Scholar]

- Long, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.-S.; Woods, M.; Zou, J. Accelerated restructuring in rural China fueled by ‘increasing vs. decreasing balance’ land-use policy for dealing with hollowed villages. Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Long, H. The economic and environmental effects of land use transitions under rapid urbanization and the implications for land use management. Habitat Int. 2018, 82, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, D.; Abrahams, R. Mediating urban transition through rural tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 75, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Liu, W.; Lu, D.; Chen, H.; Ye, C. Progress of China’s new-type urbanization construction since 2014: A preliminary assessment. Cities 2018, 78, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, N.; He, Z.; Zhang, L. How did land titling affect China’s rural land rental market? Size, composition and efficiency. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Gong, Y.; Lu, D.; Ye, C. Build a people-oriented urbanization: China’s new-type urbanization dream and Anhui model. Land Use Policy 2019, 80, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fan, P.; Yue, W.; Song, Y. Impacts of land finance on urban sprawl in China: The case of Chongqing. Land Use Policy 2018, 72, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Renwick, A.; Nie, P.; Tang, J.; Cai, R. Off-farm work, smartphone use and household income: Evidence from rural China. China Econ. Rev. 2018, 52, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Zhou, X.; Renwick, A. Impact of off-farm income on household energy expenditures in China: Implications for rural energy transition. Energy Policy 2019, 127, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Liu, T.-Y.; Chang, H.; Jiang, X. Is urbanization narrowing the urban-rural income gap? A cross-regional study of China. Habitat Int. 2015, 48, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tan, S.; Yang, S.; Lin, Q.; Zhang, L. Urban-biased land development policy and the urban-rural income gap: Evidence from Hubei Province, China. Land Use Policy 2019, 87, 104066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yi, L.; Pengcan, F.; Hualou, L. Impacts of land consolidation on rural human–environment system in typical watershed of the Loess Plateau and implications for rural development policy. Land Use Policy 2019, 86, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-S.; Lu, S.; Chen, Y. Spatio-temporal change of urban–rural equalized development patterns in China and its driving factors. J. Rural. Stud. 2013, 32, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Deng, Y.; Fu, B. Rural attraction: The spatial pattern and driving factors of China’s rural in-migration. J. Rural. Stud. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.M.; Wall, G.; Wang, Y.; Jin, M. Livelihood sustainability in a rural tourism destination—Hetu Town, Anhui Province, China. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yep, R.; Forrest, R. Elevating the peasants into high-rise apartments: The land bill system in Chongqing as a solution for land conflicts in China? J. Rural. Stud. 2016, 47, 474–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Liu, Q.; Gu, S.; Wang, Q. The impact of China’s urbanization on economic growth and pollutant emissions: An empirical study based on input-output analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 1289–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Lin, W. Transforming rural housing land to farmland in Chongqing, China: The land coupon approach and farmers’ complaints. Land Use Policy 2019, 83, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, X. Exploring the relationship between rural village characteristics and Chinese return migrants’ participation in farming: Path dependence in rural employment. Cities 2019, 88, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deininger, K.; Jin, S.; Xia, F.; Huang, J. Moving Off the Farm: Land Institutions to Facilitate Structural Transformation and Agricultural Productivity Growth in China. World Dev. 2014, 59, 505–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Gao, J.; Chen, J. Behavioral logics of local actors enrolled in the restructuring of rural China: A case study of Haoqiao Village in northern Jiangsu. J. Rural. Stud. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Chen, H.; Xia, F. Toward improved land elements for urban–rural integration: A cell concept of an urban–rural mixed community. Habitat Int. 2018, 77, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Dunford, M.; Song, Z.; Chen, M. Urban–rural integration drives regional economic growth in Chongqing, Western China. Area Dev. Policy 2016, 1, 132–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-S.; Liu, J.-L.; Zhou, Y. Spatio-temporal patterns of rural poverty in China and targeted poverty alleviation strategies. J. Rural. Stud. 2017, 52, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Guo, L.; Zheng, L. Urbanization and rural livelihoods: A case study from Jiangxi Province, China. J. Rural. Stud. 2016, 47, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-C.; Zinda, J.A.; Yeh, E. Recasting the rural: State, society and environment in contemporary China. Geoforum 2017, 78, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Huang, X.; Bao, H.X.H.; Ju, X.; Zhong, T.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, Y. Rural land rights reform and agro-environmental sustainability: Empirical evidence from China. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Cao, Y.; Bai, Y. The impact of the land certificated program on the farmland rental market in rural China. J. Rural. Stud. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Zhu, H.; Sun, Z. Rural issues under China’s rapid urbanization. Hebei Acad. J. 2013, 33, 94–96. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Jia, L.; Wu, W.; Yan, J.; Liu, Y.-S. Urbanization for rural sustainability—Rethinking China’s urbanization strategy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wu, B. Revitalizing traditional villages through rural tourism: A case study of Yuanjia Village, Shaanxi Province, China. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Wang, H.; Quan, Q.; Xu, J. Rurality and rural tourism development in China. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 30, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Bao, J. Evolution of rural tourism landscape character network: The case of Jiangxiang village. Geogr. Res. 2016, 38, 1561–1575. [Google Scholar]

- Rees, H. Intangible Cultural Heritage Protection in China, Asia Dialogue 25 July 2017. Available online: https://theasiadialogue.com/2017/07/page/3/ (accessed on 1 July 2019).

- Duncan, E.M. Tourism and Cultural Heritage Preservation. SSRN Electron. J. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irandu, E.M. The role of tourism in the conservation of cultural heritage in Kenya. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2004, 9, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lussetyowati, T. Preservation and conservation through cultural heritage tourism. Case study: Musi riverside Palembang. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 184, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X. Research into the business patterns of tourism performing project-take The Impression of Lijiang and The Legend of Romance as an example. J. Hunan Inst. Eng. 2013, 23, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bu, W.; Chen, H. Reflections on the experience of endogenous development in rural area of ethnic minorities –a case study of national and ecological tourism in Hai Village of Lijiang. J. Qujing Norm. Univ. 2011, 30, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. New Rural Construction Problems and Countermeasures of Weifang Coastal Areas. Master’s Thesis, Ocean University of China, Qingdao, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Z. On the shortage of migrant workers in southeastern coastal cities of China based on the labor supply status of Henan Province. J. Xinyang Coll. Agric. For. 2015, 25, 73–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, N.; Li, G.; Yuan, Y. Rural community governance mode transation under New Urbanization progress. J. Reg. Econ. 2015, 6, 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, P. The difficulty and confusion in the protection of traditional buildings under the background of New Urbanization. J. Shanxi Archit. 2018, 44, 21–22. [Google Scholar]

- Blello, D. Against enormous odds, a Chinese official is Trying to Green up His City, Huffington Post, 24 March 2014. Available online: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/chinese-city-climate-change_n_58407c2be4b017f37fe38018?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAFznf5QdtdSmsD5HSM-bsfZLZ0ci_EXk-vQ52ooL4JStVRbWLBtzdxP-plZQwp0zUc_Met0dxSlyqH7ixH0HtkUTghxx2dDtJU_cjCXehOC2gUaHqszuAer63FIVIcvXUaKKIFu3FQy-pmzrutAEuxZbK3W0J7cR9ul-LAkaXKAu (accessed on 21 November 2018).

- Sotiriadis, M.; Vrontis, D.; Tsoukatos, E. Pairing intangible cultural heritage with tourism: The case of Mediterranean diet. EuroMed J. Bus. 2017, 12, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Time Period | Policies | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| 1978–2005 | Surplus agricultural labor from economic liberalization fuelled rural–urban migration, but restrained by township and village enterprises (TVE) growth, household registration system | Income disparities, rural-urban migration, but Lewis model not fully applicable |

| 1990s to 2006 | 1990s reclassification from rural to urban: no migration. However, rural property restrictions, tax reforms increased pressure on migration | “Vacant rural residence phenomenon” |

| 2006 | Policy of increasing urban land and reducing rural residential land: “new rural construction” | Mixed success, top-down, failed to take into account rural residents’ views |

| 2014 | “People-oriented approach”, or “new urbanization” | Bottom-up approach more acceptable to rural residents |

| 2018 | “Rural socialization” integrates rural and urban stakeholders, consistent with “rural rejuvenation” strategy | Rise of “cultural-oriented rural development”, leading to heritage tourism. |

| The Dance | Description |

|---|---|

| The Dragon Dance | Origin unknown, but pre-Qing dynasty. Different versions all over China. Worship of dragon as lord of all sea spirits. Pray for protection during fishing and bountiful harvests. |

| The Shui or Aquatic Dance | Originated from Yuan dynasty. Prayer to appease sea spirits and creatures under the Dragon King. Dancers don costumes mimicking the deities of marine creatures. |

| The Han Boats Dance | Originated from Qing dynasty. Celebrates fishermen’s life at sea and wish for a comfortable life at home. Movements mimic work at sea |

| The Stilts Dance | Celebrates fishermen’s use of stilts to move their nets to deeper waters. Often celebrated ritually by combining it with the Hai Yang Yangge danceon land |

| Similarities | Contrasts | |

|---|---|---|

| Lijiang | Rizhao | |

| Rich in cultural assets | Focused on commercialization | Focused on heritage preservation |

| Strong awareness of cultural identity | Emphasizes performance | Emphasizes heritage, authenticity |

| Advantageous geographical location | Secondary benefits to other rural residents | No secondary benefits |

| Historical antiquity | Attracted urban investors, return migrants | Barely able to retain local talent |

| Strong cultural identity | Private sector has major role | State-driven |

| Sustainability at expense of authenticity | Heritage preservation at expense of sustainability | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, X.; Cheong, K.-C.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y. Developmental Sustainability through Heritage Preservation: Two Chinese Case Studies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3705. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093705

Song X, Cheong K-C, Wang Q, Li Y. Developmental Sustainability through Heritage Preservation: Two Chinese Case Studies. Sustainability. 2020; 12(9):3705. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093705

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Xiao, Kee-Cheok Cheong, Qianyi Wang, and Yurui Li. 2020. "Developmental Sustainability through Heritage Preservation: Two Chinese Case Studies" Sustainability 12, no. 9: 3705. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093705

APA StyleSong, X., Cheong, K.-C., Wang, Q., & Li, Y. (2020). Developmental Sustainability through Heritage Preservation: Two Chinese Case Studies. Sustainability, 12(9), 3705. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093705