Abstract

In recent decades, collaborative initiatives have become relevant in Latin America, however, the owners of these businesses still face great challenges to mobilize consumers interest. In the research field, many collaborative consumption (CC) researchers have focused on the identification of their predictors; but studies that have explored this phenomenon via motivations perspective are very limited, especially those that focus on the Latin American context. Furthermore, these studies have analyzed on particular consumption activities and consumers with previous experience, restricting the scope of its results. To close this gap, the research has as its purpose the exploration of the motivating factors that best predict the intention to participate in CC activities into one of the three countries with the greatest number of collaborative businesses in the region. The ANOVA and CHAID are applied to a sample of 2080 people. The results reveal that, although enjoyment, sustainability, reputation and economic benefits are significant factors for CC, not all are equally effective in promoting high levels of participation in Latin American context. These findings allow to achieve a better understanding of the collaborative phenomenon, and also they contribute to the development of value proposals and more focused recruitment strategies for potential consumers in the region.

1. Introduction

Collaborative consumption (CC) has become more and more relevant in society as an alternative to traditional consumption [1]. Its new economic and production models promote the conservation of resources, the reduction of environmental footprints and market access for individuals isolated due to lack of resources, among other reasons [2,3,4]. All of this has led to CC being considered a currently effective mechanism to foment sustainable development [5,6,7,8,9,10].

Within the CC trend is framed a series of entrepreneurial ventures based on the development of online platforms that make coordination between peers possible, in order to exchange, share, rent and lend goods and services [11]. For several years, these companies have begun to gain more prestige and reputation in their diverse sectors, where they have become quite representative [12]. Within the hotel sector, for example, the company Airbnb is valued at 30 billion USD, a figure similar to that of the Marriot hotel chain, with the difference being that the former does not have rooms among its assets. As for Uber, it is the largest company offering taxi services in the world, with a value of 69 billion dollars despite not possessing its own fleet of vehicles to offer services [13]. In 2015, the value of the collaborative market rose to 15 trillion USD. It has been predicted that this figure, within a mere decade, could rise to 335 trillion dollars, exponential growth that is evidence of its enormous potential.

Latin America has not been untouched by this phenomenon. For just under a decade, it has experienced the arrival of global ventures as well as local and regional initiatives meeting with varying levels of success [14]. Currently, a total of 27 collaborative initiatives are in operation in this region. Peru, Brazil, Mexico and Argentina host 79% of these ventures in the region [15]. The main challenge that entrepreneurs who embark on these initiatives face is the recruitment of participants interested in supplying and demanding goods and services [16,17,18].

Previous studies have focused on exploring the factors that incentivize participation in these initiatives [1,19,20], but there are still some gaps that have not been addressed. First, to understand the real needs of the users that participate in these CC initiatives, many authors have mentioned that the motivations behind their participation must be identified [21]. These motivations are relevant inasmuch as their ability to incentivize long-term behaviors has been demonstrated [22,23,24]. Studying their motivations would help consolidate collaborative entrepreneurial ventures; however, in academic works on CC, motivating factors have hardly been touched on [12,25]. Second, the few studies that have been carried out in this field from the motivations perspective have focused on very specific activities, like car sharing, house sharing or room sharing, limiting, therefore, the results to a specific sector. Third, the studies that have been carried out have analyzed consumers with previous experience, ignoring potential customers [26,27,28]. Consequently, those studies’ findings do not explain what measures to adopt to expand global demand. Fourth, the studies on CC have focused mainly on developed economies, a reality that, as many authors have pointed out, greatly differs from the Latin American experience [29], in which many market characteristics like informality and mistrust are present on a grand scale [30,31]. Given this situation, it is not possible to presuppose that the results identified in previous studies would be valid in this context [32].

Faced with these gaps in the literature, this study proposes addressing the following research question: Which motivating factors best predict the intention to participate in CC activities in Latin American economies? To respond to this query, the following research objectives were proposed: a) to evaluate motivating factors in potential consumers with different levels of intention to participate in CC and b) to identify the relevance of said motivating factors when it comes to explaining a greater intention to participate in CC. To fulfill these objectives, a literature review and an empirical cross-sectional study with an analysis of univariate variance and data mining (ANOVA and CHAID) have been conducted.

The study centers on Peru as an example of a leading economy in the region in terms of CC. This country stands out in Latin America for having a high concentration of international CC initiatives and for developing an important number of similar initiatives on a local and regional level. In this regards, Peru is the second largest economy in terms of international CC initiatives in Latin America. (19 of the 27 international initiatives present in the region operate in said country.) Additionally, Peru occupies third place in the region for local development of CC initiatives: 11% of this type of initiatives developed in the region did so in Peru [15]. Therefore, exploring the relevance of motivating factors in this context could contribute greatly to shedding new light to be able to understand this phenomenon in Latin America.

The results of the research contribute both theoretically and practically. On a theoretical level, this research promotes a better understanding of the CC phenomenon by not only identify intrinsic and extrinsic motivators that promote intention in potential consumers but also establishes which among them are the best predictors for participation in CC initiatives from a Latin American context, aspects not covered by existing studies on this topic. At a practical level, the findings lay the foundations for the development of focalized value propositions and recruitment strategies that motivate potential consumers to adopt collaborative consumption activities, promoting with it the development of this emerging market.

The rest of the document is structured as follows. In Section 2, the theoretical background necessary for tackling the established research question is presented. In this section, an extensive literature review of more than 250 articles oriented toward identifying factors that would predict intention to engage in CC was carried out. In Section 3, the methodology applied is explained. Then, in Section 4, the results are described, and the findings are discussed. In Section 5, the conclusions, implications, limitations and future lines of research are presented.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Conceptualization of CC

CC has been conceptualized in many different ways in the literature; thus, an important aspect of this study is the clear definition of what CC is and the perspective from which it should be approached. This section seeks to fulfill that purpose, presenting the definition and characteristics of the collaborative phenomenon that are considered in this study.

Currently, it is difficult to find a unique definition of collaborative consumption (CC) due to the variety of concepts that have emerged in academic literature to explain the most precise and simple use of this term [33,34,35,36].

For this present research, the definition proposed by Hamari, Sjöklint and Ukkonen [37] will be used: “CC is a peer-to peer-based activity of obtaining, giving, or sharing access to goods and services, coordinated through community based online services.” These models are characterized by the way they deem financial remuneration a result of the process [37]. Among the most common types of collaborative exchange are the rental, lending and exchange of goods, services, transportation solutions, space and money (e.g., Rent the Runway, Car2go, Uber, Citibike, Airbnb, Vinted, TaskRabbit and Crowflower) [38].

From the perspective of Hamari, Sjöklint and Ukkonen [37], CC is a part of the sharing economy, an emerging phenomenon that has become very relevant in recent years thanks to the rise of the Internet [1]. Of course, in the sharing economy, in addition to CC, diverse activities based on the nonmonetary exchange of goods and services coexist, such as open source software projects (e.g., SourceForge and Github), online collaboration (e.g., YouTube, Instagram and Wikipedia), file sharing (e.g., The Pirate Bay) and peer-to-peer financing (e.g., Kickstarter).

All of these activities or business models on the subject of CC encourage sustainable consumption practices [39]. In this regard, on the economic level, CC permits a more efficient use of goods and services and also the possibility of generating additional income for owners through the rental of their property or offer of services [12]. On a social level, CC promotes the temporary access to these same goods and services on the part of the sectors of the population that do not have enough income to acquire them individually [12]. On an environmental level, CC promotes the conservation of resources and less waste than that resulting from traditional production and consumption [40].

2.2. Self-Determination Theory

This section presents the theoretical approach that will be use in the study and its potential to be applied to the field of collaborative consumption.

Carrying out a given behavior depends to a large extent on the presence of needs. Needs generate psychological processes of imbalance between the current state and the desired state of the person that motivate the individual to carry out determined actions [41]. Self-Determination Theory [42] is one of the theoretical focuses that addresses this link between behavior and motivations.

According to Self-Determination Theory, behavior prediction is focused on motivating factors that satisfy three fundamental needs: autonomy, affiliation and competence [42]. The need for autonomy refers to the desire to freely engage in an activity, to be the master of one’s own decisions [42]. The need for affiliation is the desire to feel connected or to interact with one’s immediate surroundings [43]. The need for competence refers to the search for effectiveness, mastery or control of the activities that are carried out while interacting with one’s surroundings [42]. The motivators that the theory postulates can be divided into two categories: intrinsic and extrinsic [42].

Intrinsic motivators are born of one’s own incentives to engage in the activity, that is to say, the challenge, stimulus or enjoyment that the individual experiences when carrying out the process. People also experience this type of motivation due to the perceived value of behaving within established norms. Intrinsic motivations drive one to engage in a behavior because it is gratifying or because it is related to personal objectives like affiliation, personal development or fruitfulness.

Extrinsic motivations, on the other hand, are related to the stimuli separate from the activity itself, for example, a reward that will be obtained from engaging in the activity or the possibility of avoiding a punishment [42]. These motivators are related to personal objectives like fame, wealth or attractiveness.

In the literature on topics related to marketing, there is ample empirical evidence that supports the validity of Self-Determination Theory to predict behavior adoption. For example, studies like those of Chatzisarantis and Hagger [44] and Weinstein and Ryan [45] have demonstrated the direct relationship between self-determined motivations and behavior. Moreover, other studies have highlighted the indirect impact (through intentions) that motivating factors have on behavior [46,47].

In the context of CC, using this motivational perspective proves appropriate because the exchange activities that take place in collaborative initiatives are capable of meeting the fundamental needs proposed by Deci and Ryan [42]. The need for competence can be satisfied thanks to access to cheaper products or services or even thanks to the earning of additional income through the assets that one possesses. CC initiatives can also provide new and more effective opportunities to access goods or services and the feelings of gratification that come as a consequence of the self-control and freedom they offer, which satisfy the need for autonomy. Finally, the need for relationships is satisfied through the possibility that CC offers of building active communities [48].

2.3. CC Motivating Factors

This section explores the progress of the CC literature from a motivations perspective, focusing on demonstrating the main gaps that have not yet been addressed and also presenting motivating factors that were relevant in previous studies and that are included in the variables analyzed in this study.

The gaps in the research and the motivating factors that make up this section were identified from a rigorous review of the literature. This process included a search of previous studies with similar topics in the repository Web of Science, a database recognized as the most reliable for carrying out this type of analysis [49]. The search terms were “Sharing economy,” “Collaborative consumption,” “Collaborative economy,” “Access-based consumption,” “Peer-to-peer economy” and “intention,” “adoption,” “participation,” and “behavior.” The words related to CC were selected based on the study carried out by Sutherland and Jarrahi [50]. The time period of analysis considered was 2008–2019 given that, according to recent research [50], it was in 2008 that CC as a research topic began to become more relevant. The search only took into consideration top academic journals. Given that the literature on this topic is fragmented and interdisciplinary [51], there was no cut based on the type of journal or the discipline. This search brought up a total of 264 articles oriented toward identifying factors that would predict intention. From this group of studies, those that possessed a motivations perspective in their analysis were considered, about 31 articles (See Appendix A).

As can be observed in Appendix A, the intrinsic factors identified are related to consumer motivation through contributing to sustainability, from an environmental, social or economic perspective, while the extrinsic factors are oriented toward the motivation to obtain the indirect benefits of said sustainability.

2.3.1. Research Gaps about CC from a Motivations Perspective

In this section, the gaps in the study of consumer behavior in CC initiatives from the literature review are identified. First, many CC researchers have focused on the identification of their predictors; however, studies that have addressed this issue from the perspective of motivations are very limited [12]. In the literature review a small number of articles (31) that analyze CC from this perspective were identified.

Second, although the 31 studies identified in Appendix A have aided the progress of this specific field of knowledge, there are still challenges to tackle. An analysis of the research contexts of these studies reports a gap in the literature: a lack of a good understanding of CC in a Latin American context. See Table 1.

Table 1.

Context of the analysis of academic articles on collaborative consumption (CC).

As can be observed in Table 1, these studies that have focused on determinants of intention, participation or adoption of collaborative economy initiatives have proven their hypothesis mainly in consumers that have already participated in these types of activities [52,53,54], only 3% have researched potential consumers (see Table 1). These contributions are interesting for their applicability value to enhance the development of specific initiatives in current consumers, however, in a market in the initial development phase, characterized by informality and distrust in the community as Latin America countries, it would be interesting to determine the motivations of potential consumers (common individuals) to participate in collaborative initiatives.

In addition to the aforementioned, the studies carried out in this field have opted for an analysis of concrete initiatives that have circumscribed the scope of their results in a specific segment. According to the literature review (see Appendix A), the vast majority of studies focus on motivations, have opted to analyze specific collaboration or exchange activities (90%), like car sharing, room sharing, open source projects or virtual communities [26,27,28].

Moreover, although these studies have contributed greatly to the literature, most of them have focused on developed economies [4,55,56], Europe being the region which the greatest number of studies analyzed (32%), followed by North America (29%), Asia and Oceania (13%) (see Table 1). The Latin American reality is different from that in developed countries. Several authors have indicated that it is not possible to presuppose that the results of these studies will also be applicable to the Latin American context [32]. Factors such as informality and lack of trust are some aspects that make a difference. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the informal economy during 2010-2014 in Latin America and the Caribbean represented 40% of GDP, well above South Asia at 34%, Europe at 23% and OECD member countries at 17% [33]. The countries of Latin America and the Caribbean region also reach the highest levels of distrust in the community. Peru, the economy studied, presents 53%, while the USA reaches 20% in 2017 [15].

Given this context, the current study proposes the identification of the motivating factors that best predict the intention to participate in CC, focusing on these great deficiencies identified.

2.3.2. Main Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivators for the Intention to Participate in CC

In this section, motivating factors that influence the intention to participate in CC initiatives are identified, grouped and explained, based on the literature review. See Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of the most frequent predictive factors of intention to engage in CC.

Intrinsic Factors

The most recurrent intrinsic motivating factors identified were “enjoyment” and “sustainability.” These motivators were found as behavioral predictors in 14 and 18 academic articles in the literature review, respectively. The intrinsic factor “enjoyment” was operationalized in different ways in the literature, through “personal satisfaction,” “personal challenge” and “enjoyment” [11,30,37], while the intrinsic factor of “sustainability” was addressed from social, environmental, and eco-friendly angles [12,19]. See Appendix A.

Enjoyment

According to different authors [57,58], one of the main reasons that motivates people to get involved in CC activities is the pleasure they derive from the activity itself. For example, Nov [57]; Nov, Naaman and Ye [30] and Hamaari and Koivisto [25] have found that the satisfaction provided by sharing knowledge is a relevant incentive for deciding whether to join CC models like those that relate to open source coding. In the same vein are studies on peer-to-peer platforms like Airbnb or Uber, which have proven the relevance of pleasure for causing people to adopt these kinds of activities [25,27,58].

Sustainability

The interest in participating in activities in the sharing economy in general and CC in particular is linked to the need to reduce environmental impact, to seek the wellbeing of society or to promote a more sustainable lifestyle [6,59]. For example, May et al. [52] were able to show evidence that interest in protecting the environment influenced the intention to share an automobile, as did Neunhoeffer and Teubner [60]. Habibi et al. [61] proved that one of the main motivators for participating in initiatives like Couchsurfing was the possibility of contributing to the improvement of the community. Additionally, Tsou et al. [10] found that to the extent to which CC experience was higher, and the extent to which more elevated sustainability was offered, it incentivized users of shared services to a greater degree.

Extrinsic Factors

The most recurrent extrinsic motivating factors that were identified were “financial benefit” and “reputation.” These motivators were found as behavioral predictors in 19 and 9 academic articles in the literature review, respectively.

The extrinsic factor of “financial benefit” was operationalized through variables such as “money saving,” “efficiency of use,” “cost saving,” “perceived utility,” “relative price” and “economic value” [12,54] in the literature review. As for the extrinsic factor of “reputation,” it was operationalized as “status,” “prestige” or “hedonistic benefits” [60,62]. See Appendix A.

Financial Benefit

Many studies have found that, if collaborative activity generates financial benefits of some type, this is a strong motivator to become involved or to participate in that initiative [1,58,62]. The studies that, for example, Lee et al. [63]; Guttentag et al. [64] and Hamari et al. [25] carried out for the shared transportation industry demonstrated the importance of financial savings as drivers of intention. Similar results were achieved in the shared lodging industry. Authors found that financial benefit is one of the main drivers for becoming involved in these kinds of activities [26,65].

Reputation

“Reputation,” understood to mean recognition reached, also impacts the intention to become involved in CC, according to studies like those by Liu and Yang [58], Neunhoeffer and Teubner [60] and Yang and Lai [53]. In this respect, Yang and Lai [53] identified that recognition has greater relevance than the personal satisfaction generated by activities in which knowledge is shared. Moreover, in the context of online communities [35,66] and open source projects [19,30], it has been demonstrated that “reputation” is an important factor for determining participation.

The applicability and relevance of intrinsic and extrinsic motivating factors to promote the intention to participate in CC in the present analytical context will be approached in the following sections of the study with the goal of answering the research question posed.

3. Methodology

This study has as its main goal the response to the aforementioned research question: Which motivating factors best predict the intention to participate in CC activities in Latin American economies? With this goal in mind, two research objectives were established: a) to evaluate motivating factors in potential consumers with different levels of intention to participate in CC and b) to identify the relevance of said motivating factors when it comes to explaining a greater intention to participate in CC. In the following section, the sample characteristics, data collection, instrument used and types of statistical analysis carried out are described.

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

A survey was applied to 6000 men and women between 18 and 64 years of age, all residents of Peru. The data collection was carried out in the 26 main cities belonging to the five macroregions that make up the country. To this end, quotas were established according to the demographic weight of each macroregion. The recruitment of participants was carried out through a multistage sample design (see Appendix B).

Among the surveyed, potential participants in CC initiatives were sought out. To this end, two questions were applied that sought to measure respondents’ knowledge about this type of consumption and their ability to participate in a CC activity: a) In general, do you consider yourself familiarized with collaborative consumption initiatives? and b) In general, do you have the knowledge and abilities necessary to access a product or service through a collaborative consumption platform? Both questions were measured on a Likert scale from 1 to 7. Survey results equal to or above 4 for both questions were considered in the study, leaving 2100 (35% of all the surveys). Then, through a data verification process, 20 surveys were eliminated, leaving 2080 valid cases. The final sample distribution with regards to gender, age and educational level is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Sample characteristics.

3.2. Collection Instrument

The survey was composed of demographic questions and scales that allowed for the measurement of the factors involved in the study. The items that made up each one of the factors used a 7-point Likert scale in which 1 meant “totally disagree” and 7 meant “totally agree.” To measure behavior, “the intention to participate in collaborative consumption” was employed. A significant body of research has demonstrated that the relationship between intentions and behaviors is extremely strong [67,68,69], and so it was considered appropriate to use this variable as a proxy. The intention was worked through three items based on the work of Bhattacherjee [70]. “Enjoyment” was measured through five items that came from the work of Van der Heijden [71]. “Sustainability” was measured through five items developed and validated by Hamari, Sjöklint y Ukkonen [25]. To measure “financial benefit,” a scale based on the work of Bock et al. [72] was used. A total of four items comprised this construct. “Reputation” was measured through four items based on the scales of Kankanhalli, Tan and Wey [36] and Wasko amotivatind Faraj [73]. The scales of the factors are found in Appendix C.

Before applying the survey and in order to have an unambiguous concept, each person being surveyed was presented with a definition of CC that included the most common examples in the country.

The consistency and reliability of the scales were examined through an exploratory factorial analysis and Cronbach’s alpha [74,75]. According to these analyses, the KMO test was greater than 0.8, Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was significant and the extracted variance was greater than 0.6. Additionally, the items adequately loaded in their respective constructs. Finally, Cronbach’s alpha for all of the constructs exceeded 0.7, the minimum limit recommended [76]. See Table 4.

Table 4.

Cronbach’s alpha and factorial loads.

To minimize the questionnaires’ own bias, the following aspects were taken into consideration. First, the questionnaire was reviewed by three expert researchers with experience on the topic in order to validate its structure, content and relevance. Minor modifications were undertaken based on their suggestions. Second, the proximity of the intention variable and the motivating variables in the questionnaire were consciously avoided, introducing them into different sections of the questionnaire. Third, each surveyed person was given the same definition of CC along with examples that were common and well-known in the country, so that there would be an unequivocal and homogenous concept of the topic which they were being asked about. Fourth, the questionnaire emphasized anonymity and confidentiality with regard to personal data in order to keep the survey participants from seeking social acceptance with their responses.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

The analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the exhaustive CHAID method (Chi-squared Automatic Interaction) were conducted. The ANOVA test was used to answer the first research objective. Through it, the average scores of the motivating factors through the different levels of intention to engage in CC are compared. The exhaustive CHAID method was applied to respond to the second research objective. Through this analysis, the most determinant factors and the relationship between them are identified, allowing in this way the identification of the path to follow to achieve higher intention to engage in CC.

3.3.1. ANOVA Test

To carry out the ANOVA test, a dependent variable was defined: the “intention to participate in CC,” as were independent variables or factors: “enjoyment,” “sustainability,” “financial benefit” and “reputation.”

Each factor was divided into three groups. The first group was made up of those answers that varied in the range of 1.0 to 3.0 and was labeled “low”; the second was made up of those answers that ranged from 3.01 to 5.0 and was labeled “medium”; finally, the third group was made up of answers that ranged from 5.01 to 7.0 and was labeled “high.” Table 5 presents the size of the resulting subsamples of each factor. After generating the subsamples, the analyses allowed for the validation of the existence of significant differences between the different groups and, thus, provided evidence for the factors’ influence on the “intention” variable.

Table 5.

Size of the subsamples by variable type.

3.3.2. Exhaustive CHAID Analysis

The exhaustive CHAID analysis [77], also known as a decision tree analysis, is an exploratory method that, based on the independent variables, divides the analyzed data into groups or categories that differ with respect to the dependent variable [78].

The applicability of the decision tree method has been proven by a wide number of corresponding studies in the field of marketing [79,80,81].

For the development of the exhaustive CHAID method, the following were employed as independent variables in the model: “enjoyment,” “sustainability,” “financial benefit” and “reputation.” “Intention to participate in CC” was the dependent variable. These factors were treated as continuous variables, since they were measured on a 7-point Likert scale.

Given that the dependent variable is continuous, Snedecor’s F was used to measure the level of significance. Additionally, the multiple comparisons and the significance values for the criteria of division and merging were corrected using the Bonferroni correction. The significance level was established as 0.05 for all analyses. All of the independent variables were measured on a 7-point Likert scale. A cross-validation of the model was carried out with the number of folds of the sample equal to 10. The objective was to evaluate the goodness of the structure of the decision tree in order to generalize to the greater population. Finally, and in anticipation of the analysis, it was corroborated that the missing data in the independent variables were in no case greater than 5%. This is an important point, since the exhaustive CHAID method deals with missing values as a category that is combined with the category of the valid data it most closely resembles once the algorithm has been generated in the model.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. ANOVA Test Results and Discussion

Before the ANOVA tests were carried out, the starting assumptions for this type of analysis were verified. Table 6 presents the results of the homoscedasticity test for each the factors analyzed. For those variables that did not meet this requirement, the Brown-Forsythe Test was applied. The multiple comparisons were carried out using the Bonferroni correction and its corresponding Tamehane’s T2 test. Finally, the independence and randomness that were obtained through the samples were guaranteed through the way data was collected.

Table 6.

Results of the tests of homogeneity of variance.

Table 7 presents the results of the ANOVA test for each one of the factors analyzed. The significance levels allow the null hypothesis about the equality of means of the intention variable to be rejected at each level (low, medium and high) for the motivating variables (p < 0.05). Therefore, it can be affirmed that intention varies according to the level of each independent variable studied.

Table 7.

Results of the ANOVA Test.

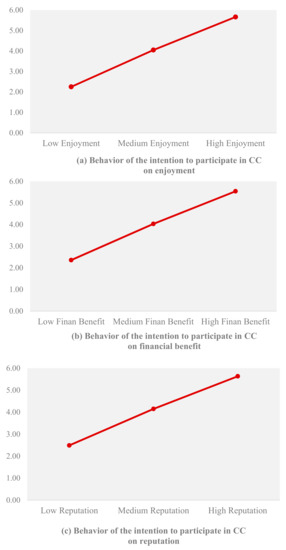

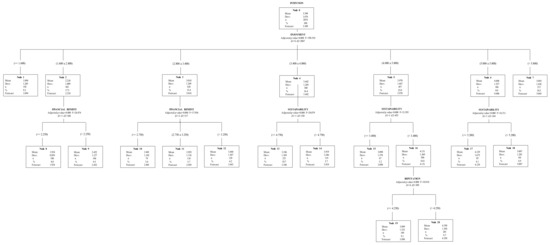

The results also show signs of a possible positive relationship between the factors analyzed and intention. As can be appreciated in Table 7, as the level increases from low to medium to high for each variable of analysis, the average values of intention to participate in CC also increase.

When the multiple comparisons are contrasted with one another, they show that the average values for “intention to participate in CC” present significant differences (p < 0.05) at all levels (low, medium, high) of the variables of the analysis. That is to say, people with an elevated “enjoyment” level possess an “intention to participate in CC” that is higher than that of people with a medium satisfaction level, and these, in turn, possess a higher intention than those who possess a low satisfaction level. This dynamic is repeated for the variables of “sustainability,” “financial benefit” and “reputation.” See Table 8.

Table 8.

Results of the contrast of multiple comparisons.

Figure 1 graphically presents the behavior of the “intention to participate in collaborate consumption” over the motivating factors. It can be seen that the mean values of the variable “intention” are increasing as a trend as the levels of “enjoyment,” “sustainability,” “financial benefit” and “reputation” increase.

Figure 1.

Behavior of the intention to participate in CC on motivating factors.

Through the ANOVA test, the relevance of the motivating factors identified in the literature review was explored to promote the intention to participate in CC for potential consumers in Peru, an example economy from the Latin American region.

These findings demonstrate that both intrinsic motivators, such as personal satisfaction and sustainability, and extrinsic motivators, like reputation and financial benefit, would stimulate intention to become involved in CC initiatives and that, due to greater motivation, there would be a greater intention to participate. These results line up with previous studies that focused on analyzing the effects of these factors on concrete CC initiatives like car sharing, room sharing, open source projects through the eyes of consumers with previous experience [19,30,31,52]. For personal satisfaction, for example, Nov et al. [30] found that this type of motivation, expressed in the satisfaction of sharing photos, incentivized a great number of those adept in social networks to participate in online communities. Pappas [26], on the other hand, determined that enjoyment, measured in terms of social interaction, positively impacts the experience of a tourist who opts for shared accommodation services. Regarding sustainability, Kim et al. [31] and May et al. [52] demonstrated that non-selfish factors (for example, interest in helping others or protecting the environment) appear to occupy a dominant role in the intention to participate in collaborate initiatives. With regard to reputation, Oreg and Nov [19] indicated that this factor could go hand in hand with altruistic motivations and motivate participation in open source projects. Finally, for financial benefit, Shaheen et al. [28] demonstrated that monetary savings was one of the main motivators for becoming involved in car sharing activities.

In this way, the findings would permit the arguments in favor of intrinsic and extrinsic motivators in the collaborative field to be extended by putting them in the context of a Latin American economy from the perspective of potential consumers without prior experience.

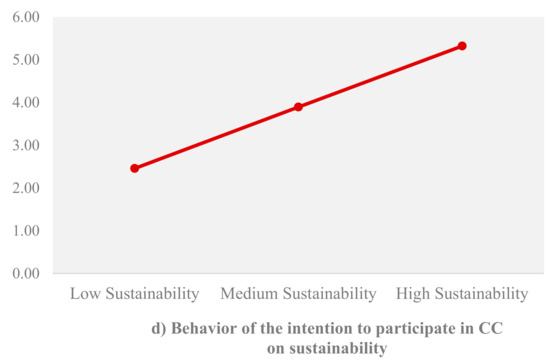

4.2. Results of the Exhaustive CHAID Analysis and Discussion

In Figure 2, the results of the decision tree analysis are presented. Three levels of node configuration can be seen. There is one variable on the first level: the most discriminant variable of the model, the one which best predicts the intention to participate in CC, “enjoyment” (F = 198.52; d1 = 6; d2 = 2067; p <0.000).

Figure 2.

Decision tree of the motivating factors on the intention to participate in CC.

On the second level can be found both “financial benefit” and the benefit of “sustainability” as predictive variables. However, in light of the results, it appears that this last variable is the second-most representative after “enjoyment.” The impact on the averages of node 4 to 7 shows this. As level of satisfaction increases, the averages go from 3.42 (Node 4) to 3.97 (Node 5), 4.0 (Node 6) and 5.0 (Node 7).

The third level contains one variable, “reputation,” but the decision tree shows it is only important for those groups that perceive moderate benefits for “sustainability” (greater than 3.4 and less than 5.2). At these levels, “reputation” boosts “sustainability,” causing an increase in the averages, which go from 4.13 (Node 16) to 4.35 (Node 20).

Finally, the decision tree shows that “financial benefit” is the least impactful variable. As can be seen in Nodes 2 and 3, its presence does not relevantly modify the averages of the “enjoyment” variable (help them to reach values over 3.5, which would indicate a positive impact on the intention variable).

The CHAID analysis sought to identify the relevance of the intrinsic and extrinsic motivating factors to participate in CC among potential consumers originating in the economy chosen as representative of Latin America.

These results reveal that the intrinsic “enjoyment” factor is the best predictor for participation in collaborative business models. This indicates that, when there is more evidence that collaborative activity could generate feelings of enjoyment as it is carried out, there is a higher probability that potential consumers without previous experience would become involved in CC activities [25].

The second most predictive factor for elevated intention to participate in CC is “sustainability.” Just as the decision tree shows, this motivator is activated secondarily when there is a medium level of enjoyment. This finding is not surprising; as diverse authors observe, the possibility of carrying out exchanges or collaborating with the community in a simple way is associated with a tendency toward social innovation that is stimulated by a desire to contribute to society and the environment [82]. Involvement in collaborative initiatives allows for the satisfaction of the desire to become active and responsible citizens, and, therefore, constitutes an alternative attraction [6].

After “enjoyment” and “sustainability,” “reputation” motivates the intention to participate in CC only when the first two motivators have reached high levels. This means that “reputation” does not apply for all potential consumers. It appears that only those who have a moderate interest in “sustainability” are influenced by this extrinsic factor. This could be due to the fact that the need for reputation is not present in all individuals at equal levels; of course it depends on the personality of each one for it to become more or less representative [33].

“Financial benefit” is the factor that least boosts participation in CC activities. Indeed, it appears that obtaining financial remuneration does not turn out to be as powerful a stimulus for involvement in these types of activities as the aforementioned factors are. This can be seen in the decision tree, where this extrinsic motivator only activates under low levels of perception of enjoyment from the activity and even so does not increase the intention to participate in CC very significantly.

In general, these results, which are labeled “enjoyment,” followed by “sustainability” and “reputation,” as meaningful factors to achieve higher levels of intention to participate in CC, leaving “financial benefit” as the least relevant factor, partially differ from studies carried out in other contexts and for consumers with previous experience [12,62]. The first study, which was about motivating factors that boost or hinder CC in the US travel and tourism market, identified that, while those surveyed recognized protecting the environment and helping the community as important motivators, the cost saving opportunities factor was the dominant reason for becoming involved in these types of collaborative options [62]. Meanwhile, the second one found that the dominant motives for consumers to participate in German car sharing were finances and enjoyment, leaving sustainability as an indirect consequence of participation [62]. In brief, it appears that, in the Latin American context and for potential Latin American consumers, motivations to participate in CC initiatives go further than those which cost savings can generate and are actually associated with more intrinsic elements like enjoyment and contributing to society and the environment, mainly. These findings are interesting inasmuch as diverse studies have demonstrated that behaviors that come from autonomous (more intrinsic) motivations, like those highlighted in this study (enjoyment and sustainability), have a higher probability of being maintained long term [22,23,29]. The greater the probability of achieving short-term behaviors, the greater the probability of increasing demand and contributing to the growth of the collaborative market.

5. Conclusions

This study identified that potential consumers originating in the context of analysis would participate in CC initiatives for intrinsic motivators, like enjoyment and sustainability, as well as for extrinsic motivators, like reputation and financial benefit. These findings also show that not all these motivators contribute equally to incentivizing that intention. More precisely, personal satisfaction, an intrinsic factor, is the best motivator, followed by sustainability reputation and, finally, financial benefit. These findings have generated interesting theoretical and practical contributions for this field of knowledge, which are presented as follows, along with the limitations and future lines of research.

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

The results of the study enrich the literature on CC and contribute to a deeper understanding of this phenomenon for several reasons. First, these results come out of a practically unexplored context—the Latin American context—and focus on potential consumers, not current ones. Second, they use a theoretical focus that promotes the adoption of behaviors that are lasting, not temporary, a consideration that is very relevant for promoting development and sustainability in a nascent market like those common to the region. Third, the study does not only identify intrinsic and extrinsic motivators that promote intention but also establishes which among them are the best predictors for participation in CC initiatives, an aspect not covered by existing studies on this topic.

On a practical level, this study could help companies develop much more effective recruitment and communication strategies to offer an interesting proposal to potential consumers. Concretely, these findings incentivize owners or marketers of collaborative business models to focus on developing an environment conducive to exchange that promotes “enjoyment” first and “sustainability” second, so that they can then move on to generate effective communication strategies that are capable of transmitting those benefits to potential consumers.

In the same vein, this study also suggests that the incorporation of strategies oriented toward exclusively or mostly demonstrating extrinsic motivators, like reputation or financial benefit, should be approached with caution. It is probable that these types of factors will not be able to generate as effective an impact to boost participation as the intrinsic motivators do.

Finally, the effective application of recruitment and communication strategies based on the results of the research will help boost the growth of these types of initiatives and, therefore, develop the collaborative market, contributing to a less consumerist and more sustainable society.

5.2. Limitations and Further Studies

This study includes several limitations. First, the analysis focuses on one country in particular in the Latin American region. Although this economy is a forerunner with regard to collaborative initiatives, it is recommendable that future research bet on replicating this study in other Latin American economies with the goal of lending greater external validity to the findings. In this same vein, the development of comparative studies between countries, taking into account the influence of the values and cultural norms of each economy, could help a greater understanding of the phenomenon to be reached through the identification of global and local aspects for each country.

Second, this research analyzes the intention to participate as a proxy for real participation. This variable was not selected randomly. Its inclusion made it possible to study the motivations of potential consumers and not just current ones. Moreover, it is a measurement proven through diverse studies in the field of consumer behavior. However, future studies could directly explore real participation in CC in order to determine diversified management strategies according to the behavior of its target market. Third, in this study, the focus is on motivational factors for consumers to participate in collaborative initiatives; however, diverse theories regarding consumer behavior indicate that the inclusion of other factors, such as attitudes, perceptions and environmental influence, could improve the explanation of the phenomenon studied. Future studies should approach these aspects independently or in a more integrated model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and Design, J.A.-R., C.G.-M., M.M.-F. and J.S.-N.; Methodology, J.A.-R., C.G.-M. and M.M.-F; Validation, M.M.-F and J.S.-N.; Formal Analysis; Investigation.; Data Curation, J.A.-R. and C.G.-M.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, J.A.-R. and C.G.-M.; Writing—Review and Editing, M.M.-F and J.S.-N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivating Factors identified by the Literature Review.

Table A1.

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivating Factors identified by the Literature Review.

| Authors | Factors | Type of consumer | Methodology | Type of Activity | Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pappas (2019) | EX: Price-quality relacionship IN: Enjoyment of social interaction benefits NR: Perceived risk | 712 users of sharing activities | Quantitative | Car sharing | Greece |

| Morone et al. (2018) | EX: Financial consciousness IN: Respect for the environment, interest in helping others | 20 users | Experimental | Food sharing | Italy |

| Piscicelli, Ludden and Cooper (2018) | EX: Money saving IN: Care for the environment, Enjoyment of social interaction | 1119 Peerby users | Case study | Product sharing | Other countries |

| Liu and Yang (2018) | EX: Reputation NR: Ease of use, trust, imitation of others | 394 bike sharing users | Questionnaire | Bike sharing | China |

| So, Oh and Min (2018) | EX: Relative price, social interactions IN: Enjoyment NR Perceived risk, trust, novelty, authenticity, ease of use | 250 Airbnb users | Questionnaire | Peer-to-peer accommodation | Other countries |

| Neunhoeffer and Teubner (2018) | IN: Personal benefit, social interaction, ecological sustainability EX: Financial benefit, prestige NR: trust, social influence, lifestyle, familiarity | 745 users | Questionnaire | Peer-to-peer sharing platforms | Other countries |

| Oyedele and Simpson (2018) | IN: Social utility, pro-social utility NR: Ease of transaction, Ease of use, trust | 345 users | Questionnaire | Car-sharing, room-sharing and household goods purchases | United States |

| Lan et al. (2017) | IN: Self-efficacy, personal compensation NR: Learning process | 21 interviews | Case study | Car sharing | China |

| Wilhelms, Henkel and Falk (2017) | EX: Financial interests IN: Improvement of the quality of life, helping others, sustainability | 20 users | Interviews | Car sharing | Germany |

| Parguel et al. (2017) | EX: Price sensitivity IN: Social and environmental consciousness NR: Impulse to buy, materialism | 541 users | Questionnaire | Peer-to-peer sharing platforms | Francia |

| Böcker and Meelen (2017) | EX: Financial benefits IN: Environmental motivations, social motivations | 1330 users | Questionnaire | Peer-to-peer sharing platforms | The Netherlands |

| Dall Pizzol, Ordovás de Almeida and Do Couto Soares (2017) | EX: Cost saving IN: Socioenvironmental consciousness NR: Ease of use | 126 users | Questionnaire | Peer-to-peer sharing platforms | Brazil |

| Barnes and Mattsson (2017) | EX: Financial benefit, social benefit IN: Environmental benefit | 115 users | Questionnaire | Car sharing | Denmark |

| Zhu, So and Hudson (2017) | EX: Social benefit IN: Self-efficacy | 314 users | Questionnaire | Ridesharing applications | China |

| Guttentag (2017) | EX: Price of service NR: Quality of service, comfort, trust | 844 users | Questionnaire | peer-to-peer accommodation | Canada |

| Tussyadiah and Pesonen, J. (2016) | EX: Cost saving IN: Enjoyment of the experience and contact with peers | 450 users | Questionnaire | peer-to-peer accommodation | United StatesFinland |

| Habibi, Kim and Laroche (2016) | IN: Social, communitarian, enviromental or moral values EX: Financial remuneration | 14 users | Questionnaire | Car rentals, peer-to-peer housing/apartment rentals or sharing | United States |

| Ert, Fleischer and Magen (2016) | EX: Reputation NR: Trust | 260 users 640 users | Data | Social networks Room sharing | Sweden |

| Shaheen, Chan and Gaynor (2016) | EX: Monetary savings IN: Environmental motivations NR: Ease of use | 16 interviewed users | Interviews | Car sharing | United States |

| Hamari, Sjöklint and Ukkonen (2016) | EX: Financial reasons, reputational reasons IN: Enjoyment reasons, sustainability reasons | 168 consumers | Questionnaire | Virtual communities | Other countries |

| Möhlmann (2015) | EX: Cost saving, reputation in the community IN: Environmental impact, enjoyment NR: trust, utility, familiarity, quality of service, affinity with the trend | 236 Car2go users187 Airbnb users | Questionnaire | Car sharing Room sharing | Germany |

| Hamari and Koivisto (2015) | IN: Social influence NR: Utility | 200 users | Questionnaire | Gamification | Finland |

| Tussyadiah (2015) | EX: Financial value, perceived utility IN: Sustainability benefits | 799 users | Questionnaire | Peer-to-peer accommodation | United States |

| Efthymiou, Antoniou and Waddell (2013) | IN: Social and environmental factors | 233 young people from 18 to 35 years old | Questionnaire | Peer-to-peer sharing platforms | Greece |

| Bardhi and Eckhardt (2012) | EX: Financial benefit | 40 ZIPCar users | Interviews | Peer-to-peer sharing platforms | United States |

| Rosen, Lafontaine and Hendrickson (2011) | IN: Feelings of belonging NR: trust | 1094 users | Questionnaire | Peer-to-peer sharing platforms | Other countries |

| Nov, Naaman and Ye (2010) | IN: Perceived enjoyment of the activity (adventure and self-improvement) | 276 Flickr users | Questionnaire + follow-up post | Virtual communities | United States |

| Yang and Lai (2010) | EX: Achievement or reputation IN: Enjoyment of the activity NR: Personal values | 235 Wikipedia users | Questionnaire | Shared knowledge | Other countries |

| Oreg and Nov (2008) | IN: Altruistic motivations, self-development EX: Reputation | 185 collaborative technological project users 354 Wikipedia users | Questionnaire | Open source software projects | Other countries |

| May, Ross, Grebert and Segarra (2008) | EX: Financial value IN: Sustainability benefits | 11 and 23 users | Questionnaire / Observation | Car sharing | United Kingdom |

| Roberts et al. (2006) | IN: Enjoyment of the personal challenge | 288 users | Questionnaire | Open source software projects | United States |

IN = Intrinsic motivators; EX = Extrinsic motivators; NR = Other predictive factors not associated with motivations.

Appendix B

Sample Specifications

The questionnaire was applied in the five regions that make up the country. The point of contact for the selection of the participants was their homes. To ensure random selection of the same a multi-stage, probabilistic sampling method was applied, according to the following characteristics:

- In the first stage, cluster sampling was applied to select the districts.

- In the second stage, stratified sampling was applied to select the areas.

- In the third stage, a simple random sample was applied to select the homes.

In order to select the participants randomly inside the household, the Kish method was used [83].

Appendix C

Table A2.

Scales.

Table A2.

Scales.

| ITEMS | TD | TA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention | |||||||

| In the future, I hope to carry out actions of collaborative consumption often. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| In the future I will participate in actions of collaborative consumption more frequently. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| In the future, I will increase my participation in collaborative consumption activities if possible. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Enjoyment | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I think collaborative consumption is nice. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I think collaborative consumption is exciting. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I think collaborative consumption is interesting. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I think collaborative consumption is pleasant. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I think collaborative consumption is fun. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Financial Benefit | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I think I can save money if I participate in collaborative consumption actions. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I think my participation in actions of collaborative consumption benefits me financially. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I think my participation in shares of collaborative consumption can improve my financial situation. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I believe that my participation in collaborative consumption actions allows me to save water. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Reputation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I think that contributing to collaborative consumption actions improves my image against to others. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I think that participating in collaborative consumption actions makes me gain recognition of others. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I think I would gain the respect of others if I share with people through activities of collaborative consumption. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I think people who do activities of collaborative consumption have more prestige than those that do not. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Sustainability | |||||||

| I think that collaborative consumption helps people conserve natural resources. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I think collaborative consumption is a way of sustainable consumption. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I think collaborative consumption is ecological. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I think collaborative consumption is efficient in terms of energy use. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I think collaborative consumption is environmentally friendly. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

Note: TD = Totally disagree. TA= Totally agree.

References

- Möhlmann, M. Collaborative consumption: Determinants of satisfaction and the likelihood of using a sharing economy option again. J. Consum. Behav. 2015, 4, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, B.; Sandin, G.; Peters, G.M. Life cycle assessment of clothing libraries: Can collaborative consumption reduce the environmental impact of fast fashion? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 1368–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, M.; Baltas, G.; Stan, V. Car sharing adoption intention in urban areas: What are the key sociodemographic drivers? Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2017, 101, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parguel, B.; Lunardo, R.; Benoit-Moreau, F. Sustainability of the sharing economy in question: When second-hand peer-to-peer platforms stimulate indulgent consumption. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 125, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. Sharing. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 36, 715–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botsman, R.; Rogers, R. What’s Mine is Yours: How Collaborative Consumption is Changing the Way We Live; Collins: London, UK, 2011; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Prothero, A.; Dobscha, S.; Freund, J.; Kilbourne, W.E.; Luchs, M.G.; Ozanne, L.K.; Thøgersen, J. Sustainable consumption: Opportunities for consumer research and public policy. J. Public Policy Mark. 2011, 30, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albinsson, P.A.; Yasanthi Perera, B. Alternative marketplaces in the 21st century: Building community through sharing events. J. Consum. Behav. 2012, 11, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.B.; Ho, C.W. No money? No problem! The value of sustainability: social capital drives the relationship among customer identification and citizenship behavior in sharing economy. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsou, H.T.; Chen, J.S.; Yunhsin Chou, C.; Chen, T.W. Sharing Economy Service Experience and Its Effects on Behavioral Intention. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piscicelli, L.; Cooper, T.; Fisher, T. The role of values in collaborative consumption: Insights from a product-service system for lending and borrowing in the UK. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 97, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P. An exploratory study on drivers and deterrents of collaborative consumption in travel. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2015; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 817–830. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, B. The $99 billion idea: How Uber and Airbnb won. Bloomberg Businessweek. Disponible en. 2017. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/features/2017-uber-airbnb-99-billion-idea/ (accessed on 18 January 2020).

- PwC, 2015. Sharing or Paring: Growth to the Sharing Economy. 15 August 2015. Available online: http://www.pwc.co.uk/issues/megatrends/collisions/sharingeconomy/ (accessed on 17 December 2019).

- Parente, R.C.; Geleilate, J.M.G.; Rong, K. The sharing economy globalization phenomenon: A research agenda. J. Int. Manag. 2018, 24, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multilateral Investment Fund and IE Business School (2016). Economía Colaborativa en América Latina. Available online: https://publications.iadb.org/bitstream/handle/11319/7806/La-economia-colaborativa-en-America-Latina.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 4 October 2017).

- Gharib, R.; Philpott, E.; y Duan, Y. Factors affecting active participation in B2B online communities: An empirical investigation. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 516–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keymolen, E. Trust and technology in collaborative consumption. Why it is not just about you and me. In Bridging Distances in Technology and Regulation, 1st ed.; Leenes, R.E., Kosta, E., Eds.; Wolf Legal Publ. (WLP): Oisterwijk, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 135–150. [Google Scholar]

- Oreg, S.; Nov, O. Exploring motivations for contributing to open source initiatives: The roles of contribution context and personal values. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2008, 24, 2055–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberton, C.P.; Rose, R.L. When is ours better than mine? A framework for understanding and altering participation in commercial sharing systems. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wen, H. How Is Motivation Generated in Collaborative Consumption: Mediation Effect in Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, D.; Iso-Ahola, S.E. Leisure and health: The role of social support and self-determination. J. Leis. Res. 1993, 25, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moller, A.C.; Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and public policy: Improving the quality of consumer decisions without using coercion. J. Public Policy Mark. 2006, 25, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.Y.; Lu, H.P. Why people use social networking sites: An empirical study integrating network externalities and motivation theory. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 1152–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Sjöklint, M.; Ukkonen, A. The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 2047–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, N. The complexity of consumer experience formulation in the sharing economy. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, K.K.F.; Oh, H.; Min, S. Motivations and constraints of Airbnb consumers: Findings from a mixed-methods approach. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, S.A.; Chan, N.D.; Gaynor, T. Casual carpooling in the San Francisco Bay Area: Understanding user characteristics, behaviors, and motivations. Transp. Policy 2016, 51, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Guardia, J.G.; Ryan, R.M.; Couchman, C.E.; Deci, E.L. Within-person variation in security of attachment: A self-determination theory perspective on attachment, need fulfillment, and well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nov, O.; Naaman, M.; Ye, C. Analysis of participation in an online photo-sharing community: A multidimensional perspective. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. JASIST 2010, 61, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.G.; Woo, E.; Nam, J. Sharing economy perspective on an integrative framework of the NAM and TPB. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 72, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiszewski, C.; Labroo, A.A.; Rucker, D.D. A tutorial in consumer research: Knowledge creation and knowledge appreciation in deductive-conceptual consumer research. J. Consum. Res. 2016, 43, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. You are what you can access: Sharing and collaborative consumption online. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1595–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, L.; Jonelis, A.; Cangul, M. The Informal Economy in Sub-Saharan Africa: Size and Determinants; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Claffey, E.; Brady, M. Examining consumers’ motivations to engage in firm-hosted virtual communities. Psychol. Mark. 2017, 34, 356–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankanhalli, A.; Tan, B.C.; Wei, K.K. Contributing knowledge to electronic knowledge repositories: An empirical investigation. MIS Q. 2005, 113–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Koivisto, J. Why do people use gamification services? Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 35, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owyang, J.; Tran, C.; Silva, C. The collaborative economy: Products, Services, and Market Relationships Have Changed, as Sharing Startups Impact Business Models. Available online: http://www.altimetergroup.com/research/reports/collaborative-economy (accessed on 16 June 2013).

- Kim. Understanding Key Antecedents of Consumer Loyalty toward Sharing-Economy Platforms: The Case of Airbnb. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenken, K.; Schor, J. Putting the sharing economy into perspective. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2017, 23, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. How may consumer policy empower consumers for sustainable lifestyles? J. Consum. Policy 2005, 28, 143–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Selfdetermination in Human Behavior; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzisarantis, N.L.; Hagger, M.S. Effects of an intervention based on self-determination theory on self-reported leisure-time physical activity participation. Psychol. Health 2009, 24, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, N.; Ryan, R.M. When helping helps: Autonomous motivation for prosocial behavior and its influence on well-being for the helper and recipient. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standage, M.; Duda, J.L.; Ntoumanis, N. A model of contextual motivation in physical education: Using constructs from self-determination and achievement goal theories to predict physical activity intentions. J. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 95, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavergne, K.J.; Sharp, E.C.; Pelletier, L.G.; Holtby, A. The role of perceived government style in the facilitation of self-determined and non self-determined motivation for pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böcker, L.; Meelen, T. Sharing for people, planet or profit? Analysing motivations for intended sharing economy participation. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2017, 23, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Kouranos, V.D.; Arencibia-Jorge, R.; Karageorgopoulos, D.E. Comparison of SCImago journal rank indicator with journal impact factor. FASEB J. 2008, 22, 2623–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, W.; Jarrahi, M.H. The sharing economy and digital platforms: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 43, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M. Sharing economy: A review and agenda for future research. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 57, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, A.; Ross, T.; Grebert, J.; Segarra, G. User reaction to car share and lift share within a transport ‘marketplace’. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2008, 2, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.L.; Lai, C.Y. Motivations of Wikipedia content contributors. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1377–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, S.J.; Mattsson, J. Understanding collaborative consumption: Test of a theoretical model. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 118, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyedele, A.; Simpson, P. Emerging adulthood, sharing utilities and intention to use sharing services. J. Serv. Mark. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morone, P.; Falcone, P.M.; Imbert, E.; Morone, A. Does food sharing lead to food waste reduction? An experimental analysis to assess challenges and opportunities of a new consumption model. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 185, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nov, O. What motivates wikipedians? Commun. ACM 2007, 50, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Witt Huberts, J.C.; Evers, C.; De Ridder, D.T. License to sin: Self-licensing as a mechanism underlying hedonic consumption. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissinger, A.; Laurell, C.; Öberg, C.; Sandström, C. How sustainable is the sharing economy? On the sustainability connotations of sharing economy platforms. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 206, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neunhoeffer, F.; Teubner, T. Between enthusiasm and refusal: A cluster analysis on consumer types and attitudes towards peer-to-peer sharing. J. Consum. Behav. 2018, 17, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, M.R.; Kim, A.; Laroche, M. From sharing to exchange: An extended framework of dual modes of collaborative nonownership consumption. J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 2016, 1, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelms, M.P.; Henkel, S.; Falk, T. To earn is not enough: A means-end analysis to uncover peer-providers’ participation motives in peer-to-peer carsharing. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 125, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Lee, B.Y.; Kim, H.W. Decisional factors leading to the reuse of an on-demand ride service. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttentag, D.A.; Smith, S.L. Assessing Airbnb as a disruptive innovation relative to hotels: Substitution and comparative performance expectations. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 64, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P.; Pesonen, J. Impacts of peer-to-peer accommodation use on travel patterns. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 1022–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, D.; Smith, S.W.; Williamson, T. Reputation and reliability in collective goods: The case of the online encyclopedia Wikipedia. Ration. Soc. 2009, 21, 283–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard, B.H.; Hartwick, J.; Warshaw, P.R. The theory of reasoned action: A meta-analysis of past research with recommendations for modifications and future research. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 15, 325–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Understanding information systems continuance: An expectation-confirmation model. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Heijden, H. User acceptance of hedonic information systems. MIS Q. 2004, 28, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, G.W.; Zmud, R.W.; Kim, Y.G.; Lee, J.N. Behavioral intention formation in knowledge sharing: Examining the roles of extrinsic motivators, social-psychological forces, and organizational climate. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 87–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasko, M.M.; Faraj, S. Why should I share? Examining social capital and knowledge contribution in electronic networks of practice. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Burman, R.; Zhao, H. Second-hand clothing consumption: a cross-cultural comparison between A merican and C hinese young consumers. Int. J. Consumer Stud. 2014, 38, 670–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall Pizzol, H.; Ordovás de Almeida, S.; do Couto Soares, M. Collaborative consumption: a proposed scale for measuring the construct applied to a carsharing setting. Sustainability 2017, 9, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill Book Company: New York, NY, USA, 1978; pp. 86–113, 190–255. [Google Scholar]

- Kass, G.V. An exploratory technique for investigating large quantities of categorical data. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C (Appl. Stat.) 1980, 29, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Diepen, M.; Franses, P.H. Evaluating chi-squared automatic interaction detection. Inf. Syst. 2006, 31, 814–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaker, G.; Hallak, R. Moderating effects of tourists’ novelty-seeking tendencies on destination image, visitor satisfaction, and short-and long-term revisit intentions. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 600–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassiliadis, C.A. Destination product characteristics as useful predictors for repeat visiting and recommendation segmentation variables in tourism: A CHAID exhaustive analysis. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2008, 10, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, J.A.; Hastak, M. Segmentation approaches in data-mining: A comparison of RFM, CHAID, and logistic regression. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 656–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schor, J.B.; Fitzmaurice, C.J. Collaborating and connecting: The emergence of the sharing economy. In Handbook of Research on Sustainable Consumption; Edward Elgar Publishing: Troutham, UK, 2015; p. 410. [Google Scholar]

- Kish, L. A procedure for objective respondent selection within the household. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1949, 44, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).